Municipal

Finance in India: An Assessment

P.K.Mohanty, B.M.Misra, Rajan

Goyal, P.D.Jeromi*

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction Local Self-Government Institutions (LSGIs)

or Local Bodies in India, being at the cutting edge level of administration, directly

influence the well-being of the people by providing civic services and socio-economic

infrastructure facilities. The Constitution (73rd and 74th) Amendment Acts, 1992

(for rural and urban local bodies, respectively) have accorded a constitutional

status to these institutions as the third-tier of Government. The Constitution

(74th Amendment) Act, 1992 has mandated grassroot level democracy in urban areas

by assigning the task of preparation and implementation of plans for economic

development and social justice to elected municipal councils and wards committees.

It has incorporated the Twelfth Schedule into the Constitution of India containing

a list of 18 functions as the legitimate functional domain of Urban Local Bodies

(ULBs) in the country. In view of this position, the demands placed by the public

on municipal authorities for the provision of various civic services have increased

considerably. Further, with globalization, liberalization, the rise of the service

economy and revolution in information and communication technologies, cities are

being increasingly required to compete as centres of domestic and foreign investment

and hubs of business process outsourcing. Civic infrastructure and services are

critical inputs for the competitive edge of cities in a fast-globalizing world.

However, without a commensurate enhancement of their resource-raising powers,

cities are faced with fiscal stress as a result of which their capacity to contribute

to national development as engines of economic growth is severely constrained.

While the Twelfth Schedule of the 74th Amendment Act, 1992 demarcates the

functional domain of municipal authorities, the Amendment Act has not provided

for a corresponding ‘municipal finance list’ in the Constitution of

India. The assignment of finances has been completely left to the discretion of

the State Governments, excepting in that such assignment shall be ‘by law’.

This has resulted in patterns of municipal finances varying widely across States

and in a gross mismatch between the functions assigned to the ULBs and the resources

made available to them to discharge the mandated functions. The ULBs depend on

the respective State Governments for assignment of revenue sources, provision

of inter-governmental transfers and allocation for borrowing with or without State

guarantees. Constitutionally built-in imbalances in the functions and finances

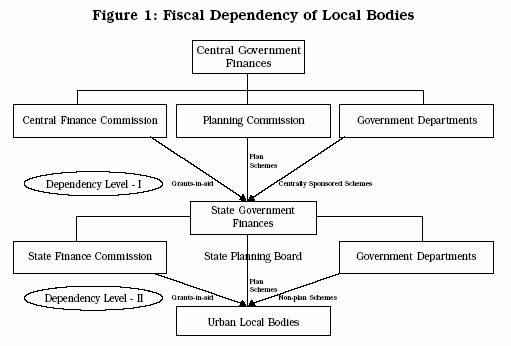

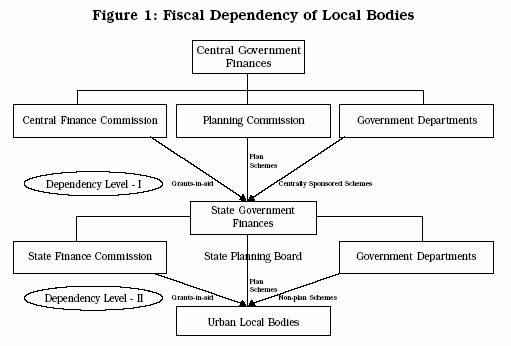

eventually reflect in the high dependency of urban local bodies on State Governments

and of the State Governments on the Central Government1 .

Under the constitutional

scheme of fiscal federalism, funds from the Central Government are devolved to

the State Governments. Following the recommendations of the State Finance Commissions

(SFCs) and taking into account the devolutions made by the Central Finance Commission

(CFC), the State Governments are required to devolve resources to their local

bodies. However, due to endemic resource constraints, they have not been in a

position to allocate adequate resources to their ULBs. This is further compounded

by the fact that even the existing sources of revenues are not adequately exploited

by many of the ULBs. The above factors have led to rising fiscal gaps in these

institutions, with resources drastically falling short of the requirements to

meet the backlog, current and growth needs of infrastructure and services in cities,

and, thereby, failing to meet with the expectations of citizens and business.

To address the fiscal stress, some ULBs began to resorting to borrowings in recent

years, often with State Government guarantees, from Housing and Urban Development

Corporation (HUDCO), financial institutions, banks, open market, external lending

agencies like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. This has implications

for both Central and State finances, as it reflects the dependency of the ULBs

and consequently, the provision of local public services on the policies and programmes

of Central and State Governments (Figure 1). The launching of the

Jawaharlal

National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) by the Government of India on 3rd December

2005 reflects the recognition, at the Government of India level, of the need to

support ULBs to improve infrastructure facilities and basic services to the poor

in cities and towns.

The rising fiscal gaps of ULBs have led to a search

for best practices of local government reforms nationally as well as internationally.

A study of international practice and experience on such reforms suggests the

following key lessons for the conduct of effective local-self government in a

federal structure:

• Functions of

local bodies – expenditure assignment – must be clear;

•

Finances of local bodies – revenue assignment – must be clear;

• Finances must be commensurate with the

functions assigned;

• Functionaries

must be aligned to functions and finances meant for discharging the functions;

• Functions performed or services delivered

must be commensurate with the funds provided;

•

Performance measurement framework, accountability channels, and reporting lines

of functionaries must be clear;

•

Professional civic management, committed civic leadership and informed public

participation are critically important for the efficient and effective delivery

of civic services to the people.

1.2 Importance of Local Public

Finance

Any analysis of finances of State and Central Governments

in isolation (excluding that of the local bodies) will not provide a holistic

picture of the public finances of the country. Recognizing the fact that India

is increasingly urbanizing, and given the estimate that of more than 50 per cent

of India’s population will live in urban areas in another 3 to 4 decades,

one cannot afford to ignore the fiscal situation of ULBs. Civic infrastructure

and services in most cities and towns are in a poor state. They are grossly inadequate

even for the existing population, leave alone the need for planned urbanization

and peripheral development to accommodate migrants and in situ population

growth. The floods in Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad and Bangalore in the recent past

have exposed the vulnerability of cities, their fragile ecology, weak infrastructure

systems, faulty planning, long records of under-investment and fiscal imbalances.

With rising expectations from the public, the financing of civic infrastructure

and services has assumed critical importance socially, economically and politically.

The importance of local public finance also emanates from another critically

important factor, i.e., increase in poverty in cities and towns seen

to be accompanying urbanisation – a phenomenon that is described as ‘urbanisation

of rural poverty’ (Table 1).

Urban poverty alleviation and slum

development are regarded as legitimate functions of urban local bodies according

to the 74th Amendment Act. However, neither the ULBs have any well-defined “own”

sources of finance to address urban poverty nor do they have recourse to a system

of adequate and predictable inter-governmental transfers to undertake poverty

alleviation.

Theoretically, the three main functions of the public sector

are: stabilization, redistribution and allocation. With growing number of urban

poor, the redistribution function, in addition to allocation, is

Table

1: Poverty Ratios of Select States (2004-05) | State | %

of Rural Population | %

of Urban Population | | Blow

Poverty Line | Below

Poverty Line | Andhra

Pradesh | 11.2 | 28.0 |

Karnataka | 20.8 | 32.6 |

Madhya Pradesh | 36.9 | 42.1 |

Maharashtra | 29.6 | 32.2 |

Kerala | 13.2 | 20.2 |

Rajasthan | 18.7 | 32.9 |

Source: Planning

Commission Estimates based on National Sample Survey Organisation 61st Round. |

emerging as a critical issue for Urban India. This needs

to be addressed through the public finance system – Central, State and Local.

Although the theory of public finance suggests that redistribution issues are

best tackled by higher levels of government through the provisioning of inter-governmental

transfers, there is no appropriate model of inter-governmental finance for local

bodies in India to tackle the colossal problem of urban poverty. The 12th Schedule

envisages that functions like ‘safeguarding the interests of weaker sections

of society, including the handicapped and the mentally retarded’, ‘slum

improvement and upgradation’ and ‘urban poverty alleviation’

belong to the legitimate functional domain of urban local bodies. However, there

are no commensurate resources with these institutions to discharge these functions

effectively. This represents a case of expenditure assignment without a corresponding

revenue assignment.

1.3 Context of the Study

The world is passing through a remarkable period of transformation in recorded

history. Globalization is sweeping across nations. New challenges and opportunities

for development are emerging from: (a) rapid flows of goods, services, capital,

technology, ideas, information and people across borders, (b) increased financial

integration of the world economy, and (c) rise of knowledge as a key driver of

economic growth. Innovations in transportation, information and communication

technologies (ICT) are leading to unprecedented levels of integration between

separated parts of the globe. The spread of ICT and the Internet are among the

most distinguishing features of the new globalizing world. The world is shifting

from a manufacturing-based industrial economy to a service-dominated and network-based

knowledge economy. Economic activity is now structured on the “international”

and “national” plains rather than “local”. Cities are

emerging as the hubs of the new economic activities fueled by globalization, ICT

revolution and surge of the service economy. In the above background, the city

finance systems need to be restructured to facilitate the emergence of competitive

cities, catering to the infrastructure and civic service needs of business as

well as residents.

With faster and more integrated economic growth, urbanisation

is gaining momentum in the developing countries; nearly half of the world today

is urban. In India, urbanisation has been somewhat slow. The country’s urban

population grew from 26 million in 1901 to 285 million in 2001, with the share

of population in cities and towns steadily rising from 10.8 per cent in 1901 to

27.8 per cent in 2001. The number of metropolitan cities went up from 1 in 1901

to 35 in 2001. The percentage of urban population living in these million-plus

cities increased from 5.84 in 1901 to 38.60 over the same period. Appendix 1 provides

a statistical picture of the trends in urbanisation and metropolitan growth in

India.

Even though India did not face an “urban explosion”

as did some other countries, the absolute magnitude of the urban population is

itself so large that the issues of shelter, civic amenities, public health and

social security are too colossal to be ignored by national authorities. Moreover,

sustainable growth of urbanisation is imperative for faster national development.

The contribution of urban areas to country’s Net Domestic Product (NDP)

has been steadily increasing from about one-third in early 1970s to about 50 per

cent in the post-liberalisation period (Table 2).

Another study, covering

later indicate that Urban areas contribute to more than half of India’s

National Income (Table 3). Within Urban India, it is the large cities that generate

the bulk of this contribution. Cities are the generators of economic wealth and

centres of employment and income opportunities.

Table

2: Share of Urban Areas in National Income | Year | Total

NDP | NDP

Urban | Share

of Urban in | | (Rs.

Billion) | (Rs.

Billion) | Total

NDP (%) | 1970-71 | 368 | 139 | 37.7 |

1980-81 | 1103 | 453 | 41.1 |

1993-94 | 7161 | 3312 | 46.2 |

Source: Central

Statistical Organisation, reported in Mohan (2004). |

Table

3: Contribution of Urban Areas to National Income |

Year | Share

of Population (%) | Share

of National Income (%) | 1951 | 17.3 | 29.0 |

1981 | 23.3 | 47.0 |

1991 | 25.7 | 55.0 |

2001 | 27.8 | 60.0 |

Source: | Ministry

of Urban Affairs, Government of India, reported in Kumar (2003). |

1.4 Urbanisation and Economic Growth

Neo-classical economists view urban centres as the drivers of regional and

national economic growth. Concentration of population and economic activity in

space is regarded crucial for leveraging certain external economies that provide

a base for improvement in productive efficiency, technological innovations and

access to global markets [Kundu (2006)]. Research in urban economics suggests

that urbanisation positively impacts on economic growth. Cities played a key role

in the development of national economies of the developed world during their days

of rapid urban growth. India’s National Commission on Urbanisation Report

(1988) stressed the role of cities as engines of economic growth, reservoirs of

capital and skill, centres of knowledge and innovation, sources of formal and

informal sector employment, generators of public financial resources for development,

and hopes of millions of rural migrants. Globalisation and liberalization have

made cities the preferred destinations of foreign investment, off-shoring and

business process outsourcing.

1.4.1 Cities

and Agglomeration Economies

Acceleration of urbanisation generally

takes place in pace with corresponding acceleration of economic growth. Urbanisation

is influenced by factors such as i) economies of scale in production, particularly

manufacturing; ii) existence of information externalities; iii) technology development,

particularly in building and transportation; and iv) substitution of capital for

land made possible by technology. Jacobs (1984) holds the view that economic life

develops via innovation and expands by import substitution. He cites the critical

role of “import-replacement” in the growth of cities due to “five

great forces”: enlarged city markets, increased numbers and kinds of jobs,

increased transplants of city work into non-urban locations, new uses of technology

and growth of city capital. Cities form and grow to exploit the advantages of

agglomeration economies made possible by the clustering of many activities leading

to scale and networking effects. As economies of scale in production begin to

take hold, larger size plants become necessary. This contributes to the need for

larger numbers of suppliers and denser settlements of customers. The services

needed by the growing agglomeration of people give rise to an even greater number

of people living together [Mohan (2006)].

Urban economists distinguish

between two types of agglomeration economies: localisation and urbanisation. Localisation

economies emanate from the co-location of firms in the same industry or local

concentration of a particular activity such as a transport terminal, a seat of

government power or a large university. They are external to firms but internal

to the industry concerned. Urbanisation economies occur from the increased scale

of the entire urban area. They are external to both firms and industries.

Localisation economies in cities result from the backward and forward linkages

between economic activities. When the scale of an activity expands, the production

of many intermediate services: financial, legal, consultancy, repairs and parts,

logistics, advertising, etc., which feed on such activity, become profitable.

Activities like banking and insurance are known for economies of scale. One obvious

advantage of agglomeration is the reduction in transportation and communication

costs due to geographical proximity. There are many other important economies

associated with localisation. For example, the concentration of workers with a

variety of special skills may lead to labour market economies to firms through

a reduction in their recruitment and training costs. Similarly, the costs of collection

and dissemination of information can go down significantly when different types

of people work and live together. Pooled availability of capital, skill and knowledge,

ease of contact, and informational spill-over between firms, institutions and

individuals make cities the centres of technological innovation, incubation and

diffusion.

Urbanisation economies arise due to the spatial concentration

of population leading to the benefits of larger, nearer and more diverse markets,

availability, diversity and division of labour and sharing of common infrastructure.

These accrue to all firms located in an urban area and not limited to any particular

group. A large concentration of firms and individuals results in lowered transaction

costs and the benefits of face-to-face contact. It also promotes risk-sharing

and access to wider choices by producers, consumers and traders. Larger urban

areas provide better matching of skills to jobs and reduce the job search costs.

The provision of civic infrastructure and services like water supply, sewerage,

storm drainage, solid waste management and transport involves economies of scale

and these facilities become financially viable only if the tax-sharing population

exceeds a certain threshold level.

The prevalence of agglomeration economies,

especially in large cities, suggests that cities are not only the centres of productivity

and economic growth, but they are also the places that promote human growth, development

and modern living. Large cities are, however, subject to the “tragedy of

the commons” and “diseconomies of congestion”, which require

appropriate interventions by way of effective urban management. Size per se

cannot be called a negative factor as long as the positive agglomeration economies

outweigh the negative congestion diseconomies.

1.4.2 Cities as

Generators of Resources

One important aspect, which has not

been adequately highlighted in empirical research, is the phenomenal contribution

of cities to the exchequers of State and Central Governments. Cities are reservoirs

of public financial resources such as income tax, corporation tax, service tax,

customs duty, excise tax, value added tax, stamp duty on registration, entertainment

tax, professional tax and motor vehicles tax. They are also the places which facilitate

the collection of user charges for the public services provided.

A study

by the Centre for Good Governance (CGG), Hyderabad in 2005 revealed that Hyderabad

and Ranga Reddy urban districts of Andhra Pradesh, containing Hyderabad Municipal

Corporation and 10 surrounding Municipalities, had only 9.5 per cent share in

the State’s population in 2001. However, the combined shares of these two

districts in the total collection of key State taxes in 2001-02, namely commercial

tax, excise, stamp duty and registration and motor vehicles tax were 72.9 per

cent, 63.0 per cent, 36.2 per cent, and 27.8 per cent respectively (Table 4).

This shows that urban areas are the generators of resources for state and national

development, including those needed for developing the rural areas. Urbanization

is likely to lead to an increase in the buoyancy of key financial resources of

Central and State Governments, presumably due to the close relationship between

urbanisation and economic growth.

The finances of urban local bodies

are bound to have critical implications for both Central and State Government

finances in the future. These essentially translate into civic infrastructure

and services, which are central to the health and productivity of city economies

and their contribution to National and State Domestic Products as well as Treasuries.

Moreover, the local government finance system in India forms an integral part

of the State Government

Table

4: Share of Hyderabad and Ranga Reddy Urban Districts Combined in |

the

Collection of Major Taxes in Andhra Pradesh | (Per

cent Share in State Collection) | | 1997-98 | 1998-99 | 1999-00 | 2000-01 | 2001-02 |

Commercial Taxes | 58.37 | 68.73 | 69.84 | 72.04 | 72.85 |

Prohibition & Excise Taxes | 53.34 | 53.53 | 59.20 | 56.84 | 63.03 |

Registration and Stamps | 32.75 | 33.96 | 34.88 | 35.45 | 36.18 |

Transport and Motor Vehicles | 27.00 | 26.80 | 27.93 | 28.27 | 27.80 |

Source: Centre

for Good Governance, Hyderabad. | finance system.

The latter is intricately connected with Central Government finances. Thus, in

essence, the local, state and national public finance systems are closely inter-linked.

Despite the position described above and the mandate of the Constitution

(73rd and 74th Amendment) Acts, 1992 requiring the local bodies to prepare and

implement plans for economic development and social justice, the plans of urban

and rural local bodies are yet to form parts of the State and Central Government

plans. Similarly, the finances of these local bodies are yet to be counted for

arriving at an aggregate picture of the public finance of the country.

1.5 Investment Requirements for Urban Infrastructure

Accelerating the flow of investible resources into urban infrastructure and services

is key to India’s agenda for economic growth, poverty reduction and urban

renewal. However, the current levels of investment are low and the capital requirements

particularly for the development of urban infrastructure in India are massive.

Estimates of funding needed by urban infrastructure are available from several

sources. The India Infrastructure Report (Rakesh Mohan Committee, 1996) pointed

out that the average plan allocation for urban infrastructure comprising water

supply, sanitation and roads was only about 9 per cent of the investment needed

for their provision and maintenance. Placing the annual average aggregate investment

requirements of urban infrastructure under the categories of water supply, sanitation

and roads at about Rs.282 billion for the period 1996-2001 and another Rs.277

billion for the period 2001-2006, at 1996 prices, the Report observed that the

planned investment was woefully inadequate for meeting even the required operation

and maintenance of core urban services, let alone for financing the additional

requirements of core civic services and other urban infrastructure.

Water

supply, sanitation and solid waste management are important basic needs affecting

the quality of life and productive efficiency of people. Provision of these basic

services continues to be amongst the core activities of the ULBs. About 89 per

cent of urban population has access to water supply and 63 per cent of urban population

has access to sewerage and sanitation facilities (Economic Survey, Government

of India, 2004-05). These data, however, only relate to access, which is different

from quantity and quality of service. The quantity and quality of water as well

as other services in most cities considerably fall short of the stipulated norms.

The Tenth Five Year Plan of the Government of India emphasized the provision

of water supply and sanitation facilities to a level of 100 per cent coverage

of urban population with potable water supply and 75 per cent of urban population

with sewerage and sanitation by the end of the Tenth Plan period, i.e.

March 31, 2007. The funds required for water supply, sanitation and solid waste

management during the Tenth Plan period (2002-2007) were projected at Rs 53,719

crore. However, as against this amount, the likely availability of funds from

different sources was estimated at Rs.35,800 crore only, indicating a shortfall

of 33.4 per cent in the requirement of funds (Table 5).

The Central Public

Health & Environmental Engineering Organisation (CPHEEO) has estimated the

requirement of funds for 100 per cent coverage of urban population under safe

water supply and sanitation services by the year 2021 at Rs.1,729 billion. Estimates

by Rail India Technical and Economic Services (RITES) indicate that the amount

required for urban transport infrastructure investment in cities with a population

of one lakh or more during the next 20

Table

5: Funds Requirement/Availability for Water Supply, Sanitation and Solid |

Waste

Management in the Tenth Plan | (Rs.

Crore) | Estimates

of Requirements of Funds | Likely

Availability from Different Sources | Water

Supply | 28,240 | Central

Government | 2,500 |

Sanitation | 23,157 | State

Governments | 20,000 |

Solid Waste Management | 2,322 | HUDCO | 6,800 |

Total | 53,719 | LIC | 2,500 |

| | Other

PF/s & External Funding Agencies | 4,000 |

| | Total | 35,800 |

Source: Economic

Survey, 2004-05, Government of India. | years

would be of the order of Rs.2,070 billion (reported in India Infrastructure Report,

2006). Obviously, sums of these magnitudes cannot be located from within the budgetary

resources of ULBs. Innovative inter-governmental and public-private partnership

approaches would be necessary to mobilise the resources required. But the urban

local bodies would have to play a key role, being the ‘most affected’

institutional stakeholders and being the public authorities mandated to undertake

the functions listed in the 12th Schedule of the Constitution. Hence the issues

of local government finance assume critical importance.

Recognising the

urban policy and finance challenges in the country, Jawaharlal Nehru National

Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) was launched by the Prime Minister of India on

December 3, 2005. The Mission encourages cities to initiate steps to bring about

improvement in the existing service levels in a financially sustainable manner.

The objectives of the Mission, inter alia, include planned development

of identified cities including semi-urban areas, outgrowths and urban corridors,

and improved provision of basic services to the urban poor. The admissible components

under the Mission include urban renewal, water supply and sanitation, sewerage

and solid waste management, urban transport, development of heritage areas, preservation

of water bodies, housing and basic amenities to the poor etc. A provision

of Rs.50,000 crore has been agreed to as Central Assistance to States under JNNURM

spread over a period of seven years over 2005-12. Given that grants from the Central

Government would constitute between 35 to 80 per cent of the JNNURM financing

plan, the Mission would entail investment in urban infrastructure and basic services

over Rs.1 lakh crore.

JNNURM aims at the following outcomes by ULBs at

the end of the Mission period:

• Modern

and transparent budgeting, accounting and financial management systems, designed

and adopted for all urban services and governance functions; •

City-wide framework for planning and governance will be established and become

operational;

• All urban poor people

will have access to a basic level of urban services;

•

Financially self-sustaining agencies for urban governance and service delivery

will be established, through reforms to major revenue instruments;

•

Local services and governance will be conducted in a manner that is transparent

and accountable to citizens; and

• e-Governance applications will

be introduced in core functions of ULBs resulting in reduced cost and time of

service delivery processes.

Reforms in urban governance are central to

the implementation of JNNURM. Linked to Government of India’s support to

States, they are based on an enabling strategy to strengthen the system of local

public service delivery. JNNURM envisages a series of reforms at the State and

ULB levels to address the issues of urban governance and provision of basic amenities

to the urban poor in a sustainable manner. The key reforms envisaged at the ULB

level are:

• Adoption of modern, accrual-based

double entry system of accounting in ULBs;

•

Introduction of system of e-governance using IT applications like GIS and MIS

for various services provided by ULBs;

•

Reform of property tax with GIS, so that it becomes major source of revenue for

ULBs and arrangements for its effective implementation so that collection efficiency

reaches at least 85% within the Mission period;

•

Levy of reasonable user charges by ULBs/Parastatals with the objective that full

cost of operation and maintenance is collected within the Mission period. However,

cities/towns in North East and other special category States may recover at least

50% of operation and maintenance charges initially. These cities/towns should

graduate to full O&M cost recovery in a phased manner;

•

Internal earmarking within local body budgets for basic services to the urban

poor; and

• Provision of basic services

to urban poor including security of tenure at affordable prices, improved housing,

water supply, sanitation and ensuring delivery of other already existing universal

services of the government for education, health and social security.

Amongst the key reforms to be pursued at the State level under the guidelines

for JNNURM is the implementation of decentralization measures envisaged in the

Constitution (74th Amendment) Act, 1992.

1.6 Imperatives of Decentralisation

International trends indicate that the globalising world is also becoming

increasingly local. Along with globalization and liberalisation, decentralisation

has also become a major plank of public policy all over the world in recent years.

There are three important reasons for this phenomenon. First, top-down economic

planning by central governments has not been successful in promoting adequate

development. Second, changing international economic conditions and structural

adjustment programmes designed to improve public sector performance have created

serious fiscal difficulties for developing countries. Third, changing political

climates, with people becoming more educated, better informed through improved

communications and more aware of the problems with central bureaucracies, have

led the public desiring to bring control of the government functions closer to

themselves [Smoke, 2001].

Governments in developing countries have resorted

to decentralization through various means: deconcentration, delegation and

devolution. Deconcentration redistributes decision-making authority and financial

and management responsibilities for providing services and facilities among different

levels of central and provincial governments. Delegation reflects the transfer

of centrally controlled responsibility for decision-making and administration

of public functions to semi-autonomous organizations. Devolution means the transfer

of authority for decision-making, finance and management to autonomous units of

local government. It involves transferring responsibilities for services to local

bodies that elect their own representatives, raise their own revenues, and have

independent authority to make investment decisions (Rondinelli and Cheema, 2002).

The 74th Constitution Amendment Act, 1992 in India aims at a decentralisation

regime through the mechanism of devolution of functions, finances and functionaries

to urban local bodies.

Originally, the Constitution of India envisaged

a two-tier system of federation. Until 1992, local governments had not been a

part of the Indian planning and development strategy. It took nearly four decades

to accord a constitutional status to Local Self-Governments and, thereby create

a three-tier system of federation. With the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act,

1992 and the Constitution (74th Amendment) Act, 1992, local bodies have come to

enjoy the recognition of a third stratum of government. In the case of urban local

bodies, enormous responsibilities have been identified in the 74th Constitution

Amendment. These include: i) preparation of plans for economic developments and

social justice, and ii) implementation of such plans and schemes as may be entrusted

to them, including those in relation to the matters listed in the Twelfth schedule

to the Constitution (Article 243W). Besides the 18 items of responsibilities envisaged

as legitimate functions of ULBs in the Constitution of India, the Legislature

of a State, by law, can assign any tasks relating to the preparation and implementation

of plans for economic development and social justice. In order to perform these

responsibilities, urban local bodies have to be financially sound, equipped with

powers to raise resources commensurate with the functions mandated. The crux of

the financial problems faced by urban local bodies is the mismatch between functions

and finances and that this mismatch is seen to be growing with urban growth, population

concentration, liberalization and globalization.

While the 74th Amendment

listed the expenditure responsibilities of ULBs, it did not specify the legitimate

sources of revenue for these authorities. It simply stated that the Legislature

of a State may, by law, i) authorize a municipality to levy, collect and appropriate

such taxes, duties, tolls and fees, ii) assign to a municipality such taxes, duties,

tolls and fees levied and collected by the State Government, iii) provide for

making such grants-in-aid to the municipality from the consolidated fund of the

state and iv) provide for the constitution of such funds for crediting all moneys

received. Thus, while the municipalities have been assigned the responsibility

of preparation of plans for a wide range of matters –from economic development

to promotion of cultural, educational and aesthetic aspects, the power to raise

resources by identifying taxes and rates to implement the plans are vested solely

with the state legislature. This has created, what is referred to in public finance

literature as vertical imbalances, i.e., constitutionally builtin mismatches

in the division of expenditure liabilities and revenue-raising powers of the Union,

States and Local Bodies. To address this problem, two significant provisions introduced

in the Constitution of India through the Constitutional Amendments are: i) the

formation of State Finances Commissions (SFCs) to recommend devolution of State

resources to local bodies and ii) enabling the Central Finance Commission (CFC)

to recommend grants-in-aid for local bodies through augmenting the State Consolidated

Funds.

Article 243Y, inserted into the Constitution of India by the 73rd

Amendment Act, makes it mandatory on the part of the State Governments to constitute

SFCs once in every five years to review the financial position of the Panchayats

and the Municipalities. As far as the urban local bodies are concerned, it is

mandatory for the SFCs to review and recommend the principles of devolution of

resources from the State Government to their local bodies and suggest “measures”

needed to improve their financial position.

The 73rd Amendment Act stipulates

that the State Governor shall cause every recommendation made by the State Finance

Commission, together with an explanatory memorandum as to the action taken thereon,

to be laid before the Legislature of the State.

The Constitutional Amendment

Acts provide for a safeguard regarding the implementation of the recommendations

of SFCs. Article 280 of the Constitution under which a Central Finance Commission

is appointed once every five years to assess the financial needs of the State

Governments and to recommend a package of financial transfers from the Centre

to States is amended. It is now mandatory on the part of the CFC to recommend

“the measures needed to augment the Consolidated Fund of a State to supplement

the resources of the Municipalities in the State on the basis of the recommendations

made by the Finance Commissions of the State”. This provision is designed

to establish a proper linkage between the finances of the local bodies, State

Governments and Central Government.

1.7 Objectives of the Study

Even after a constitutional status was accorded to the local bodies in 1992,

the finances of these authorities are yet to be recognized as an integral part

of the public finance system in India. It is only recently that some attempts

were made to analyse their fiscal situation as discussed in the subsequent chapter.

Paucity of data and the consequent absence of authoritative literature have made

the subject of local public finance in India a black box. The entire discussion

in Chapter 8 of the Twelfth Finance Commission’s report brings out the fact

that, despite several attempts, there is no source of reliable data on finances

of all local bodies in India to estimate their resource gaps. Hence, the Commission

was constrained to fix the total amount of grants-in-aid to local bodies on an

ad hoc basis. Availability of firm and comparable data on municipal finances

in India is conspicuous for its absence. There have been a very few comprehensive

studies of municipal revenues and expenditure in India till date. In this context,

this study sets the following objectives:

i) To critically examine the

provisions relating to revenues and expenditure of municipalities and bring out

the mismatch between their revenue authority and expenditure responsibilities

in the light of international as well as national experiences.

ii) To

examine the trends in major revenue sources and expenditures of municipalities

and assess their fiscal position.

iii) Analyse performance of ULBs in

the provision of civil infrastructure.

iv) Examine and identify major

constraints that could influence the overall performance of ULBs in the provision

of civic infrastructure.

v) To estimate and project the resource requirements

of the municipal sector in the country during the 10-year period from 2004-05

to

2013-14, and suggest measures for improving municipal finances.

1.8 Analytical Framework, Data Source and Limitations

This study is an attempt to critically examine the fiscal position of ULBs in

India. Before examining the fiscal position, it is imperative to look at the broad

contours on which fiscal position of local bodies are evolving. Both urbanization

and fiscal decentralization are putting increasing pressure on the fiscal position

of ULBs to provide civic infrastructure facilities and services. Hence, the study

starts with examining the aspects relating to urbanization and fiscal decentralization,

having implication for the financial position of urban local bodies, based on

a review of the existing literature, relevant acts and rules and secondary data.

For analyzing the fiscal position of municipalities, reliable secondary data

on fiscal variables of comparable ULBs are not available from a single source.

The report of the Twelfth Finance Commission provides some broad data, which will

not enable any detailed disaggregated analysis. In view of their large number

(numbering more than 3,700), it is rather difficult to obtain data individually

from all the ULBs. Hence, for the present study we have selected 35 major municipal

corporations (MCs), situated in cities with population of more than one million

according to 2001 Census. Budget documents from MCs were obtained and then data

on major revenue and expenditure heads for a five year period from 1999-2000 to

2003-2004 (all actual figures) were compiled. As complete data on major variables

were available in respect of 22 MCs, most of the empirical analysis of this study

has been confined to those 22 MCs. The broad conclusions drawn from the analysis,

however, apply to other municipalities in the country as well.

It may

be stated upfront that there are several limitations to the data used in this

study. First, budget documents of urban local bodies are not standardized and

hence classification of many of the items is not uniform across the municipal

corporations. The limited data provided in the budget documents of the municipal

corporations lacks consistency and comparability. Second, some corporations have

not provided data in respect of certain variables for the years considered for

the study. Third, even the actual data given in the budget documents might undergo

changes, after the statutory audits take place.

Besides the

accuracy of the data, the study has some other limitations. First, since local

bodies are statutorily not allowed to have deficits in their budgets, their resource

gaps cannot be assessed from the budget documents. Due to this statutory provision,

they are living within their own means, without resorting to deficit financing

as adopted by State and Central Governments. Hence, unlike State and Central Governments,

their fiscal constraints are not evident in the budget documents. Deficits and

debts are not the issues of finances of ULBs. Their main problem is the inadequacy

of resources to provide the needed urban services and infrastructure. This is

not getting reflected in their budget documents. Hence, the data available from

the municipal budgets can be used only for deciphering the trends in revenues

and expenditure and their composition. Second, the benchmark used in the study

(Zakaria Committee norm) with regard to minimum spending for urban services for

estimating the resource gap for the ULBs is very old (developed in 1960-61). With

technological changes and also changes on account of the nature of services required

by the urban population, the benchmark used in the study may not be appropriate.

In the absence of a better benchmark, Zakaria Committee norm has been used in

this study, suitably adjusted for inflation.

1.9 Structure of

the Report

Chapter 1 provides a brief introduction, background,

objectives, data source and analytical framework of the study.

Chapter

2 reviews the literature on fiscal decentralization and finances of urban local

bodies dealing with both theory and practice.

Chapter 3 looks at legal

and institutional framework to bring out the in-built asymmetry in the functions

and revenue sources of municipal bodies in India.

Chapter 4 presents

all-India trends in municipal finances based on the data drawn from secondary

sources. Thereafter, it reviews the trend and composition of municipal finances,

based on five-year period budgetary data for 35 metropolitan municipal corporations

spread across 14 States in the country.

Chapter 5 makes an assessment

of finances of the selected ULBs, in term of both standard approach and normative

approach and projects the resource requirements for urban infrastructure for a

period of 10 years.

Chapter 6 makes concluding observation wherein the

key findings are reiterated and broad directions for municipal reforms are spelt

out. Four Appendices are annexed to the Report as follows:

Appendix

1: Depicts tables indicating the trends in urbanization and metropolitan growth

in India.

Appendix 2: Describes the pattern of local public finances

in selected developed countries.

Appendix 3: Provides some details of

the State Finance Commissions and their Reports.

Appendix 4: Sets out

the formats for the proposed national database on finances of urban local bodies

– Municipal Finance Information System (MFIS).

*

Dr. P.K. Mohanty was Director General, Centre for Good Governance, Hyderabad,

when the study was taken up. Presently, he is Joint Secretary to Government

of India, Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation and Mission Director,

Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission. Shri B.M. Misra is Adviser and Shri

Rajan Goyal, Director in the Department of Economic Analysis and Policy (DEAP),

Reserve Bank of India. Dr. P.D. Jeromi was Assistant Adviser in DEAP, RBI.

The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not represent

the views of the Government of India or the Reserve Bank of India. 1

The mismatch can be of two types. First, there is constitutionally in-built mismatch

between the functions and finances of urban local bodies. Secondly, mismatch may

arise due to the inefficient application of fiscal powers by the municipalities.

Vertical imbalance arising from the first kind of mismatch is a common feature

in most countries. However, in India the magnitude of the mismatch is much higher

than other countries. Out of 18 functions to be performed by the municipal bodies

less than half of them have a corresponding financing source. This study is primarily

referring to the mismatch of the first type. |

IST,

IST,