IST,

IST,

Discussion Paper on Charges in Payment Systems

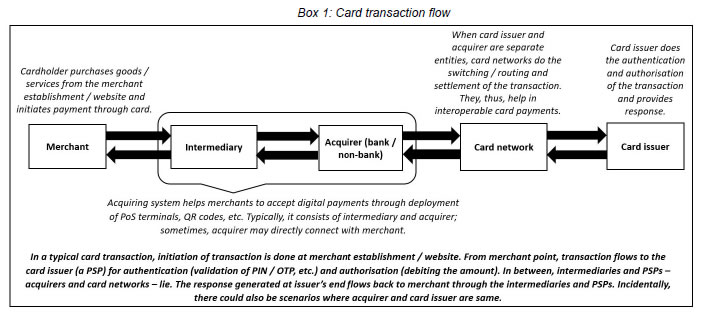

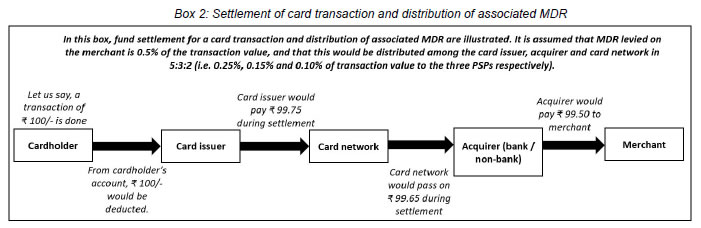

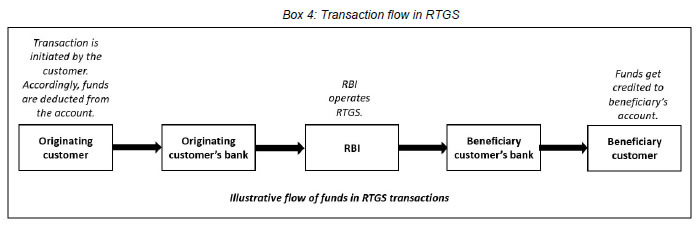

1.1. Payment and settlement systems are essential for smooth functioning of any economy. Reserve Bank of India (Reserve Bank, RBI, the Bank) has been making consistent efforts to promote digital payments in the country while maintaining their safety and security. RBI endeavours to ensure that India has ‘state-of-the-art’ payment and settlement systems that are not just safe and secure, but also efficient, fast and affordable. 1.2. Frictions in payment systems may arise, inter-alia, from infrastructure, procedures or charges related to payment transactions. Easing such frictions, while also ensuring compliance with statutory and regulatory requirements, has been the focus of RBI’s intervention in the realm of payment systems. In this regard, recent initiatives of RBI have focused on (i) augmenting the digital payments infrastructure to enhance safety and security without compromising on convenience and ease of usage, and (ii) enabling greater penetration by promoting innovative, interoperable and inclusive payment systems. These interventions mainly relate to facilitating ease and safety of transactions, improving payment infrastructure, etc. Intervention in charges, for users and others, has been minimal, warranted by market behaviour. An efficient payment system requires that the fees / charges / prices are appropriately determined, to ensure optimal cost to users and appropriate return (revenue / earning) to operators. An ideal situation would be to leave such cost-related frameworks to be market-determined, based on demand, supply, growth and user considerations. 1.3. In this context, it was considered necessary to undertake a comprehensive review of the rules and procedures for levying charges in different payment systems in the country, with the objective of assessing their impact on the efficiency, growth and acceptance of payment systems. It was considered useful in this context to place a discussion paper before the public and stakeholders, seeking views and perspectives on different dimensions of charges levied in payment systems. 1.4. This discussion paper outlines existing rules and manner of charges levied in payment systems and presents other options through which such charges could be levied. The intent is to present various issues involved in an unbiased manner and to seek feedback on a set of questions that emanate therefrom. The idea is also to get inputs and thereafter use them for further policy making. As can be seen at the end of discussion on different payment systems, a few queries have been raised on which public / stakeholder feedback is requested. Based on the feedback received, RBI would endeavour to structure its policies and streamline the framework of charges for different payment services / activities in the country. At this stage, it is reiterated that RBI has neither taken any view nor has any specific opinion on the issues raised in this discussion paper. 2. Rationale for Prescribing Charges 2.1. Payment systems operators are independent entities started with an initial outlay of capital. They incur further expenditure to create and operate safe and secure payment systems, acquire customers, comply with statutes / regulations and generate public awareness. Therefore, like any other industry, the objective of promoters includes recovery of costs and generation of sufficient returns to ensure continued operations; the cost to customers / merchants is an outcome of these objectives. 2.2. Revenue models adopted by the Payment System Operators (PSOs) are generally a function of the type of payment system operated and their ownership structure. Adjustment in models may happen when charges are prescribed through statutory1 or regulatory2 mandates, in the interest of public good. In such a scenario, it becomes important to ensure that payment services are priced in a manner that retains incentives for both, users to access the services and, service providers to offer them. 2.3. In any economic activity, including payment systems, there does not seem to be any justification for a free service, unless there is an element of public good and dedication of the infrastructure for the welfare of the nation. But who should bear the cost of setting up and operating such an infrastructure, is a moot point. A few such issues are presented in this discussion paper. 3.1. A payment system settles financial transactions between payers and beneficiaries. Flow of funds in a payment system in general involves either movement of funds from one account3 to another or loading of cash to an account or withdrawal of cash from an account. For this discussion paper, payment systems in India are categorised into two types – i. Funds Transfer Payment Systems – System facilitating transfer from one account to another account identified by originator customer [what we call as Person-to-Person (P2P) transaction]; and ii. Merchant Payment Systems4 – System facilitating payments for availing goods or services5 [what is known as Person-to-Merchant (P2M) transaction]. 3.2. Funds Transfer Payment Systems: Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS), National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) and Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) are the main exclusive funds transfer payment systems in the country. 3.3. Merchant Payment Systems: Card networks and PPI issuers provide important merchant payment systems in the country. Their features include: i. Card networks: They facilitate the issuance of card-based products like credit cards, debit cards and prepaid cards. Card network payment system can be a three-party or a four-party settlement system. Card payment system can also facilitate funds transfer from one card to another; however, they primarily function as a merchant payment system. ii. PPIs: These are issued both by banks and non-banks. Banks issue them as one of the business segments in their bouquet of products. Non-bank PPI issuers are standalone operators of this product. After the permission granted to non-banks to issue cards in affiliation with card networks, most of the card issuing non-bank PPI issuers are issuing cards in association with authorised card networks. 3.4. Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is a very popular funds transfer system, which is quite convenient and fast. RTGS and NEFT also facilitate merchant payments; but these are not popular channels for daily purchase of goods and services as – (a) RTGS is a large value payments system and is mainly used for business-to-business payments; and (b) NEFT is not an immediate payment system and confirmation of receipt of funds in the merchant’s account takes time. UPI, unlike these, facilitates immediate credit with real-time confirmation. 4. Ownership of Payment Systems 4.1. The costs / returns associated with any payment system are intrinsically linked to its ownership structure. These are important considerations for any payment system operated by a public or a private sector venture. However, the same may not be true for a Central Bank6. The objective of public good and promotion of payment systems may weigh on the Central Bank, leading it to ignore the consideration of returns, and instead absorb the cost of operations on its balance sheet. Therefore, ownership of payment systems is important for any discussion on cost and returns pertaining to payment system operations. 4.2. In India, the RTGS and NEFT payment systems are owned and operated by RBI. Systems like IMPS, RuPay, UPI, etc., are owned and operated by National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), which is a not-for-profit entity promoted by banks. The other entities like card networks, PPI issuers, etc., are profit-maximising private entities. 5. Participants and Service Providers in Payment Flow 5.1. A funds transfer payment system has the remitting customer and receiving customer as the initiator and beneficiary respectively. In a merchant payment system, the paying customer and receiving merchant are the corresponding parties. The payment flow in both types of payment systems has multiple service providers, who facilitate the payment. 5.2. In addition to the remitting customer and receiving customer, a funds transfer payment system has remitting bank, receiving bank and the central system. Further tiering can occur when banks participate as sub-members. 5.3. Payment instrument issuer, payment acquirer and PSO are three important Payment Service Providers (PSPs) in a merchant payment system7. There are multiple tiers of intermediaries in between or servicing the PSPs in processing of a typical merchant payment transaction. This is true for the three-party system and the four-party system facilitating merchant payments. The intermediaries include those acting purely as payment processors (technical service) and those who directly interpose and handle funds in the payments flow. This paper covers only the latter category of intermediaries. 5.4. The PSPs and intermediaries, and the typical role they play in payment transactions, are described below: i. PSOs8: They are card networks, NPCI (as IMPS / RuPay / UPI system operator) and PPI issuers. They deploy and provide the payment systems which facilitate processing and settlement of P2P and P2M payment transactions. The rules and procedures of the payment systems are framed by these operators (under the oversight of RBI). ii. Payment Instrument Issuers: They are bank / non-bank entities which issue the payment instruments like cards and wallets. iii. Payment Acquirers: They are bank / non-bank entities which enable the acceptance of payment instruments. They enable settlement of funds to merchants (when they are acquiring directly) or to intermediaries (where the merchant is on-boarded onto the payment system through an intermediary). iv. Intermediaries: They are entities like Payment Aggregators (PAs) or Payment Gateways (PGs) who are part of the merchant acquiring infrastructure. 6. Types of Charges in Payment Systems 6.1. Charges in a payment system are the costs imposed by the PSPs on the users (originators or beneficiaries), for facilitating a digital transaction. The charges are recovered from the originators or the beneficiaries depending on the type of payment system. 6.2. In a funds transfer payment system, the charges are generally recovered from originator of the payment instruction. These are usually levied as an add-on to the amount earmarked for remittance. Further, this amount is generally uniform, i.e., levied on a per transaction basis irrespective of amount transferred. 6.3. In case of a merchant payment system, the charges are generally recovered from the final recipient of money (i.e., merchant). This is generally done by deducting the same from the amount receivable by the merchant, i.e., a discount to the amount receivable by the merchant. These charges also differ based on the channel used for transaction. An online transaction (internet-based) is usually charged higher than an offline / face-to-face transaction [physical Point of Sale (PoS) terminals]. The higher risk management costs for an online transaction vis-à-vis an offline / face-to-face transaction, is stated to be the reason for this difference. The different types of charges recovered from originators and beneficiaries in a merchant payment system are explained below: i. Merchant Discount Rate (MDR9): This is the charge recovered by the acquirer from the final recipient of money (i.e., merchant). It is levied as a discount to the transaction amount and usually recovered during settlement of the payment transaction (Box 2). It is the most preferred way of recovering costs incurred in a merchant payment system. MDR collected by the acquirers is used to compensate the PSPs (including acquirers) and the intermediaries in the payment system. The distribution among the three PSPs – card issuer, acquirer and card network (i.e. PSO) – is based on the rules prescribed by the PSO, and the distribution between the acquirer and the intermediary is decided based on their mutual agreement.    ii. Interchange: The proportion of charges carved out of the MDR and shared with the issuer of payment instrument is called interchange. As stated earlier, the quantum of this component is determined by the rules prescribed by the PSO. In case of a debit card, the interchange compensates for the operational cost of issuer and provides income. In case of a credit card, it additionally includes recovery of interest component – i.e., the recovery of interest (from merchant) for the interest free credit given to the customer, during the interest free period. iii. Convenience Fee: Some categories of merchants or service providers / online platforms levy an additional charge generally known as convenience fee, on originating customers for merchant payment transactions. This charge is levied for providing online payment facility and is payment instrument agnostic. Generally, this fee is levied ‘per unit’ of service availed. iv. Surcharge: This charge is imposed by a merchant on a customer for processing a transaction through a particular payment mode. Some merchants engage in surcharging of digital payments by citing higher MDR expenses, especially in case of credit card transactions. However, the amount of surcharging may be different from the associated MDR expenses. 7. Regulatory and Government Intervention on Charges in Payment Systems 7.1. The charges levied in a payment system are generally governed by the rules of the PSO, in respect of both types of payment systems. In a merchant payment system, in general, the PSO rules decide the nature and distribution pattern of the charges among the different PSPs. Further, the distribution to intermediaries is decided as per agreement between them and the acquirers. In a funds transfer payment system, the originating customer is levied a charge by the originating PSP as an add-on to the transfer amount. 7.2. Efficient and widely accepted payment systems are important for any economy. Along with safety and security, reasonableness of charges is an important criterion for wider acceptance of digital payment modes. The Government and regulators have an important role in ensuring wider acceptance of payment systems. One of the main friction points in the payment systems in the country has been the high charges imposed for their use. In this regard, over the years, RBI and the Government have intervened to bring down the charges. RBI had intervened to bring down the MDR on debit cards. This was necessitated by the unreasonable practice of fixing the debit card and credit card MDR at the same level by PSOs. The high charges were restricting the acceptance of debit cards at PoS terminals and therefore, limiting their use as an instrument for cash withdrawal at Automated Teller Machines (ATMs). 7.3. To encourage the use of debit cards and to facilitate acceptance of small value transactions, especially at smaller merchants, RBI had prescribed maximum MDR for debit card transactions w.e.f. September 1, 2012, at 0.75% of transaction value for transactions up to ₹2,000/- and at 1% for those above ₹2,000/-. This was effective till December 31, 2016. Subsequently, a lower MDR (maximum 0.25% of transaction value for transactions up to ₹1,000/-, and maximum 0.5% for those above ₹1,000/- and up to ₹2,000/-) was prescribed for debit card transactions up to ₹2,000/- for a period of one year from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2017. 7.4. With effect from January 1, 2018, the maximum MDR prescribed by RBI for debit card transactions is as under:

7.5. Differentiated MDR, based on the turnover of merchant, was prescribed to safeguard the interests of smaller merchants who do not have sufficient negotiating power to deal with large acquirers. Further, it was considered that prescribing the maximum rate rather than a fixed rate would enable market discovery of ideal rates based on the cost benefit analysis of various stakeholders. 7.6. In terms of section 10A of the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 (PSS Act) – inserted vide the Finance (No. 2) Act, 2019 – no bank or system provider shall impose, whether directly or indirectly, any charge upon a person making or receiving a payment by using the prescribed electronic modes of payment. The Central Board of Direct Taxes notified RuPay debit cards and UPI as prescribed payment modes (both operated by NPCI) and the arrangement of zero charges came into effect from January 1, 2020. 7.7. Subsequently, the Government had budgeted ~₹1,500 crore for the financial year 2021-22 towards reimbursement of charges for RuPay debit card and UPI transactions. Similar financial support has also been announced for financial year 2022-23. Earlier the Government had also issued a Gazette Notification dated December 27, 2017 for reimbursement of charges to banks for all debit card, BHIM UPI and Aadhaar Pay transactions up to ₹2,000/- during the calendar years 2018 and 2019 to ensure merchants are not charged for accepting small value payments. B. Product-wise Discussion on Charges and Related Aspects Discussion on charges in different payment systems, their reasonableness, alternate views, etc., is presented in the paragraphs below. A few questions have also been raised after each discussion to elicit stakeholder and public views / feedback. The discussion and the inputs received would be used to frame policy interventions going forward. 8. Funds Transfer Payment Systems 8.1. RTGS, NEFT and IMPS are the predominant payment systems available in India for facilitating funds transfers. The current scheme of charges in these systems, the policy of the system operator and regulatory interventions, if any, etc., are discussed below. UPI, being a funds transfer as well as merchant payment system, is discussed separately. 8.2. Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) System 8.2.1. RBI is the owner, operator as well as regulator of RTGS. As the regulator, it prescribes rules of systemic nature, which have general impact on the monetary policy, financial markets infrastructure and payment ecosystem. The RTGS System Regulations impose a monthly membership fee on direct members. They also provide RBI the mandate to charge participating banks / non-banks10 for processing transactions in RTGS. Though the Regulations have enabling provisions, RBI discontinued levying processing charges and time varying charges, on members from July 1, 2019.  8.2.2. RTGS System Regulations permit direct participants to charge the customers (remitters and beneficiaries) for the services availed through them. However, RBI has prescribed that no charge can be levied by members for inward transactions. The maximum charges (exclusive of taxes, if any) permitted to be levied by members for outward transactions are as under: –

8.2.3. Further, banks are free to follow their internal policy regarding their customers subject to the overall cap. Some banks are not levying any charges for RTGS transactions initiated online. The charges levied by some banks for transactions initiated through branch channel are lower than the abovementioned charges. These decisions were mandated by RBI in its role as the regulator of payment systems, with a view to increase the use of these systems by banks to promote digital transactions. 8.2.4. As operator, RBI can be justified to recover the cost of its large investment and operational expenditure in RTGS, as it involves expenditure of public money. Further, the charges imposed by RBI in RTGS are not intended as a means of earning. The time varying charges levied on direct participants (since withdrawn) were also a means for liquidity management in the system as higher charges were mandated for transactions put through later in the day. Through this, RBI incentivised the processing of more transactions during non-peak hours of the day. 8.2.5. RTGS is a system used mainly for large value transactions and is predominantly used by banks and large institutions / merchants to facilitate real-time settlement. Does such a system, with institutions as members, require RBI to provide free transactions? Should RBI not recover its cost of infrastructure and operations? Further, should RBI mandate the charges which direct participants levy on their customers? Considering that the users of this system are customers with good knowledge of the systems and procedures, should not the charges be prescribed by the direct participants? 8.2.6. Questions for Feedback

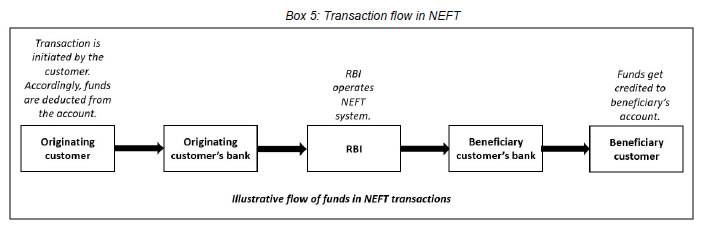

8.3. National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) System 8.3.1. RBI is the owner, operator as well as regulator of NEFT. As the regulator, it prescribes rules for NEFT. These rules currently provide RBI the mandate to charge participating banks for processing transactions through NEFT. Further, these rules also permit the direct participants to charge the customers (remitters and beneficiaries) for the services availed through them.  8.3.2. NEFT is a system operated round the clock on all days, i.e., on 24x7x365 basis. RBI does not levy any processing charges on member banks and has also advised banks to not levy any charges on savings bank account holders for fund transfers initiated online through NEFT. These measures have been taken to encourage the use of digital modes of payment for funds transfer. However, considering that banks incur additional cost and man-hours to facilitate these transactions from their branches, RBI has prescribed the following maximum customer charges (exclusive of taxes, if any) for outward transactions undertaken using NEFT initiated through branches:

8.3.3. Banks incur cost in implementing and maintaining the infrastructure required for processing NEFT transactions. They have both fixed and recurring costs which are incurred for ensuring that the infrastructure is safe and secure, and processing of payments is done in timely manner. Processing such transactions also involves costs as sufficient manpower / resources need to be deployed to support their processing. 8.3.4. As operator of NEFT, RBI has made investments for implementing the infrastructure and operating it. Therefore, though RBI may not be guided by profit motive in operating NEFT, recovery of reasonable cost could be justified. Even if such infrastructures are treated as a public good and the larger interest of digitisation of payments is served, should an approach of levying no charges be extended beyond the initial period?. 8.3.5. Questions for Feedback

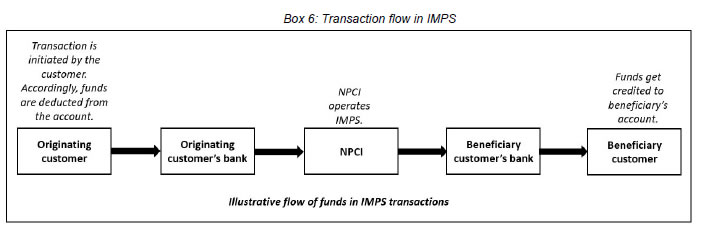

8.4. Immediate Payment Service (IMPS) 8.4.1. IMPS is a funds transfer system (push transactions) operated by NPCI that works 24x7x365. The system facilitates funds transfer up to a limit of ₹5 lakh, on real-time basis. The cost of operating and facilitating transactions in IMPS involves, inter alia, operational costs and settlement risk management costs. The charges in IMPS are a function of these costs.  8.4.2. Unlike RTGS, which facilitates real-time settlement of each transaction in central bank money, the settlement in IMPS is on a deferred net basis. To address the risk arising from real-time payments and deferred net settlements, NPCI has put in place settlement risk management arrangement like maintaining settlement guarantee funds (which are funded by the participating banks and NPCI’s own funds), availing lines of credit, etc. Direct participants incur cost for participating in the IMPS system in the form of cost of such funds placed with NPCI. 8.4.3. Charges are imposed on the originator in an IMPS transaction by the participating bank. NPCI in turn imposes transaction fee on the participant banks to recover its cost of operations. 8.4.4. IMPS transactions have continued to increase in spite of availability of other systems facilitating funds transfer without any charges. 8.4.5. IMPS also has advantages over UPI in terms of access. While UPI transactions are mobile based for the customers, IMPS transactions can be initiated using other devices also. Besides banks, IMPS allows non-bank entities such as PPI issuers to participate and facilitate remittances from wallets to the beneficiary bank accounts. 8.4.6. Questions for Feedback

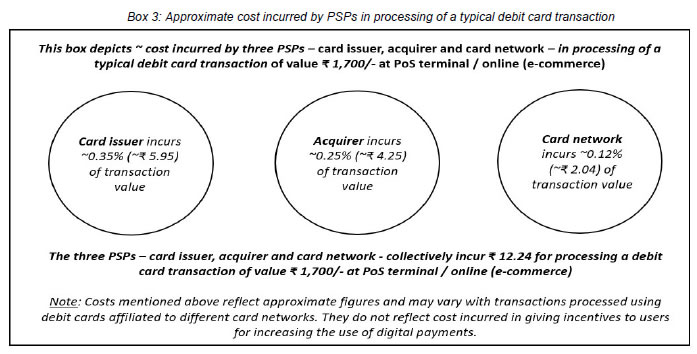

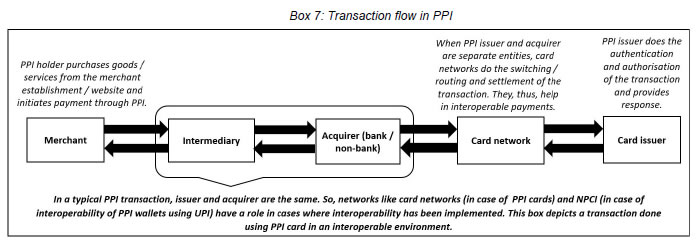

9.1. Debit cards, credit cards and PPIs constitute a significant share of the payment instruments available in India for merchant payments. The current scheme of charges in these products, policies of the system operators and participants, regulatory interventions, if any, are discussed below. While these instruments are issued by multiple banks and non-banks, they follow similar policies with regard to charges prescribed for transactions due to their reliance on card networks. The discussion here is not focused on any specific PSO but is intended to cover the relevant part of the policies of all issuers. 9.2. Debit Cards 9.2.1. A debit card is the only merchant payment instrument where RBI has intervened to bring down the cost to merchants. As mentioned earlier, RBI had prescribed a cap on MDR for debit cards w.e.f. September 1, 2012. This was necessitated by the unreasonableness of PSOs’ policy of fixing the debit card MDR at the same level as that of credit cards. The intent of intervention was to encourage the use of debit cards for acceptance of small value transactions, especially at smaller merchants. 9.2.2. The present MDR regime for debit cards has been in force for more than four years. The merchant turnover of ₹20 lakh (paragraph 7.4) was kept as per the Goods and Services Tax (GST) turnover requirements at that time. One of the options is to increase the threshold turnover from ₹20 lakh to ₹40 lakh, in sync with extant GST turnover requirements, for ‘small merchants’, and reduce maximum MDR for ‘other merchants’. Alternatively, the two merchant categories can be merged and a uniform maximum MDR can be prescribed for all types of merchants. 9.2.3. The cost to small merchants for accepting debit card transactions has come down substantially. However, RBI continues to receive complaints from merchants on their cost of accepting digital transactions. Many of these complaints arise due to the role played by intermediaries in the acquiring process. 9.2.4. The questions for consideration here are regarding further steps that need to be taken to ensure the cost to merchants and return to PSPs / intermediaries are balanced. Administered reduction of MDR can harm the ecosystem and impact the profitability of entities providing these services. This would also affect investments in infrastructure and innovation in the payments acceptance area. It is, therefore, presented that rather than further mandating reduction of MDR, it may be necessary to review the scheme followed by PSOs regarding distribution of the charges among the PSPs. Options in this regard are discussed below: i. Regulate Interchange: Interchange, the component of MDR payable to the issuer entity by the acquirer, is fixed by the PSO. Interchange is one of the main incentive used by the PSOs to attract more issuers to issue their cards. Higher interchange provides more income to the card issuers, thus, providing them the incentive to issue more cards. This component, which is payable to the issuer from the MDR (recovered from the merchant through the acquirer), reduces the maneuverability of the acquirer vis-à-vis the MDR recoverable from any merchant, as the MDR charged may not be less than the interchange payable to the issuer. Therefore, regulation of interchange can provide the acquirers the flexibility to decide the MDR charges. Further, competition in acquiring space can bring down the acquiring cost. Hence, if the interchange is regulated, the merchant and acquirer can negotiate acquiring charges between themselves. The drawback of this point of view is that as there are very few large acquiring banks, they may not bring down the cost. There may not be any control on final amount being charged to merchants, especially small merchants, as they may have less options / bargaining power as compared to big merchants. ii. Mandate Per-transaction Fee: For transaction performed using a debit card, the costs incurred by the issuer are limited to the cost of IT systems, fraud risk management systems, support systems and incentives (like reward and loyalty points) for customers. Unlike in credit cards, the debit card issuer does not incur any cost on the funds transferred. It also enjoys the float benefit. In this regard, the transaction done using a debit card is akin to a normal funds transfer payment transaction, with deferred net settlement where the merchant receives the funds on a T+n basis11. Based on this consideration, the charges for transactions involving a debit card should also be levied in a manner similar to normal funds transfer payment system. As cost to issuer / acquirer does not generally depend on transaction value of a debit card transaction, the charges could be uniform for all debit card transactions, irrespective of transaction amount. In such an arrangement of fixed rate regime, revenue from higher value transactions would be lower compared to the present experience, and the lower value transactions may face higher charges. However, the charges mandated should take into consideration the cost to issuers, acquirers and PSOs (Box 3) in facilitating the processing of payment transactions. Accordingly, a tiered charge structure could be prescribed based on the amount involved in the transaction. iii. The Government, vide amendment to the PSS Act, has made the MDR for RuPay debit cards (and UPI) zero, effective January 1, 2020. Additional details are given at paragraph 7.6. A point for discussion is whether this treatment should be exclusive to RuPay debit cards or should all debit cards be treated similarly, one way or the other. 9.2.5. Questions for Feedback

9.3. Credit Cards 9.3.1. Credit cards are payment instruments enabling a user to avail a credit facility when undertaking a payment transaction, i.e., the customer avails funds free of cost (interest), for a specific period. Credit cards have a higher MDR compared to debit cards. There are two types of costs in credit card transaction – (a) the cost of enabling a digital payment at a merchant establishment, and (b) the cost of interest foregone (including credit risk) by the issuer. The first aspect of cost, i.e., cost of enabling digital payment done using a credit card is akin to the cost of transaction done through a debit card. Logically, this component of the charges should get distributed among the PSPs and intermediaries in the proportion as accepted / finalised for debit cards. The main differentiator in a credit card transaction is the credit component and the risk of default arising therefrom. The credit component in the transaction is extended only by the card issuer and the interest is, therefore, payable to this entity. 9.3.2. RBI has not issued any regulatory mandate or intervened on MDR for credit card transactions. The main reason for this is the credit linked nature of the product. While the interest-free funds are availed by the card holder, the cost of such funds is recovered from the merchant in the form of higher MDR. Considering the nature of MDR for credit cards, the charges on merchants in a credit card transaction should ideally reflect the movement in interest rates in the market for similar tenors. A transparent mechanism for capturing this has not been put in place by the PSOs / participants. While many a time the increase in interest rates gets reflected in the form of a higher MDR, benefits of decrease in interest rates do not seem to be passed on to the merchants in the form of lower MDR. India is heavily a debit card market as seen from the number of such cards issued - ~92 crore vis-à-vis ~7.5 crore credit cards, as at end May 2022. In terms of usage, the debit and credit card turnover has been almost the same. This trend is specific to India and is in line with the mindset of our citizens in terms of lower dependency on credit for regular requirements. Further, the fact that Indians prefer to pay their credit card dues ahead of time often, rather than waiting for the due date, does not get reflected in lower MDR or in their CIBIL score. Nevertheless, in case of any delay in due payment, charges like late fee, interest on dues, etc., are levied on the credit cardholder. 9.3.3. Against this backdrop, feedback is sought on the following approaches for MDR and interchange for credit card transactions:

9.3.4. Questions for Feedback

9.4. Prepaid Payment Instruments (PPIs) 9.4.1. PPIs facilitate purchase of goods and services, provide remittance facilities, etc., against the value stored therein. PPIs can be issued in the form of cards (prepaid cards) and wallets. Where full-KYC PPIs are issued in the form of cards and wallets, interoperability across PPIs is permitted through authorised card networks and UPI respectively. When a PPI issuer ties-up with a merchant to accept payments done using its PPIs, then it becomes an on-us transaction (PPI issuer acts as issuer as well as acquirer for such transactions).  9.4.2. PPIs are akin to debit cards from the perspective of transaction processing. However, unlike debit or credit cards, which are issued only by banks, PPIs are issued by banks and non-banks. The cost involved in issuing these instruments is different for banks and non-banks. Non-banks operate PPI business as a standalone activity. They incur cost in operationalising the infrastructure for issuing and loading of PPIs as well as for providing merchant acceptance points. In respect of full-KYC PPIs, interoperability through card networks / UPI reduces the cost of deploying merchant acceptance points for such entities. For a bank, the existing infrastructure like branch network, IT, etc., can be used. 9.4.3. In case of PPIs, there is a cost involved in loading the funds, especially when PPI is loaded online using debit cards, credit cards, UPI, etc. This cost is generally borne by PPI issuer and sometimes by the customer (say, for PPI loading using a credit card - as being the market practice of some PPI issuers). The charges can be lower when PPIs are loaded by debit to a bank account (in a bilateral arrangement between PPI issuer and the concerned bank). Due to this cost of loading, the MDR for PPIs is kept more in sync with credit cards by the PSOs. RBI has not issued any instructions regarding charges for PPI-based merchant payments or funds transfer transactions. 9.4.4. Questions for Feedback

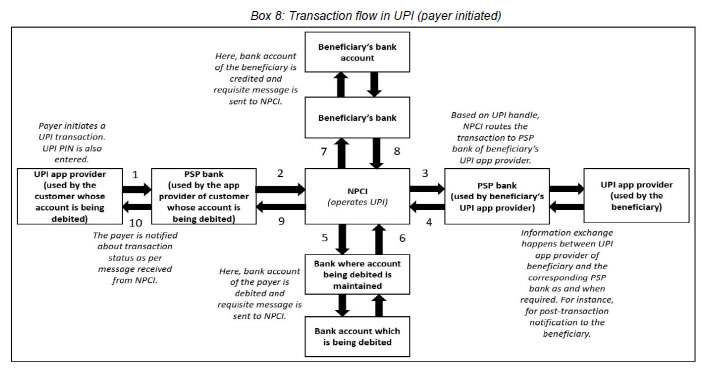

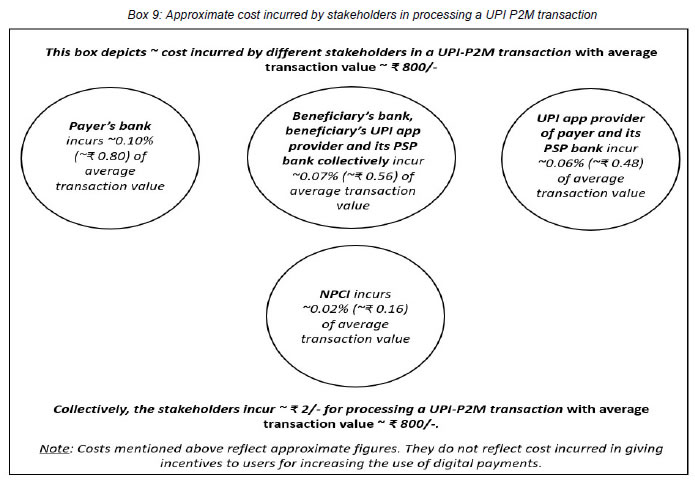

10. Unified Payments Interface (UPI) 10.1. UPI is both a funds transfer as well as a merchant payment system. The various participants in UPI include payer PSP, payee PSP, remitter bank, beneficiary bank, NPCI, bank account holders (payer and payee / merchants) and Third Party Application Providers (TPAPs). The system facilitates settlement of payment transactions using a combination of these participants.  10.2. RBI has not issued instructions regarding charges for UPI transactions. The Government has mandated a zero-charge framework for UPI transactions with effect from January 1, 2020 (paragraph 7.6). This means that charges in UPI are nil for users and merchants alike. Keeping in view that the intent of this discussion paper is to elicit general feedback, a few questions on what approach should be adopted, have been included. 10.3. As discussed throughout this paper, PSPs in any payment system should earn income for continued operations of the system to facilitate investments in new technologies, systems and processes. This is applicable irrespective of the system being operated by a public sector or a private sector entity. Box 9 provides the approximate cost involved in processing a UPI P2M transaction with average value ~ ₹800.  10.4. UPI as a fund transfer system enables real-time movement of funds. UPI as a merchant payment system also facilitates real-time settlement, as against the T+n settlement cycle for card settlements. However, the settlement among participant banks in UPI is on a deferred net basis. Facilitating this settlement requires the PSO and banks to put in place adequate systems and processes to address the settlement risk. This involves additional costs to the system. 10.5. UPI as a funds transfer system is like IMPS. Therefore, it could be argued that the charges in UPI need to be similar to charges in IMPS for fund transfer transactions. A tiered charge could be imposed based on the different amount bands. 10.6. Merchant payments using UPI do not require installation of costly infrastructure by merchants as UPI QR codes are used. The cost of merchant infrastructure for UPI is lower as compared to the cost incurred in a card-based acceptance infrastructure. 10.7. Questions for Feedback

11.1. A Payment Aggregator (PA) is a significant intermediary in the digital payments value chain. PAs, both offline and online, play an important function in facilitating acceptance of digital payments done using bank-issued or non-bank-issued payment instruments. They have successfully brought in many small merchants into digital payments acceptance fold, through deployment of PoS devices, QR codes, etc. In addition to being payment acquirers, these intermediaries provide merchants with multiple value-added services. It may be highlighted that as of now only the online PAs are being brought under regulation of RBI. 11.2. Yet another important intermediary in the payments transaction chain is the Payment Gateway (PG). It provides the necessary plumbing for the digital payments’ architecture. A notable difference between the role of PAs and PGs is in the matter of handling funds. While PAs handle funds, PGs only facilitate the processing of transactions. 11.3. The intermediaries provide payment acquiring services either as outsourced service providers of banks or direct acquirers of merchants. Where they act as service providers of banks, they apply the MDR as mandated for banks (or as per the PSO scheme) and earn income as per their agreement with banks. However, when they act as direct merchant acquirers, intermediaries also levy additional charges, over and above MDR, ostensibly for value-added services provided by them. The additional charge levied by the intermediaries is generally clubbed with the MDR and recovered from merchants as a discount per transaction processed. This practice, wherein the MDR is subsumed in the overall charge levied by intermediaries, leads to lack of transparency. Several complaints from merchants pertain to this lack of transparency, with intermediaries imposing higher charge in the name of MDR. 11.4. MDR is the charge which relates to the processing of a payment transaction. The other services provided by intermediaries do not directly pertain to settlement of payment transactions. So, it is necessary that such charges payable by the merchants are disclosed upfront and levied transparently. The discount to the transaction amount settled by intermediaries should only be for the MDR. All other charges should be separately levied. 11.5. Questions for Feedback

12. Surcharging and Convenience Fee 12.1. Surcharge and / or convenience fee are additional charges levied generally on customers while undertaking digital transactions. Being an additional load for the customers, such charges can create friction in smooth adoption of digital payments, more so if the reasons or manner of levy thereof are not transparent or apparently justifiable. It is pertinent to mention here that activities of merchants / service providers / online platforms levying them are commercial in nature, and thus, do not fall under direct purview of RBI. Given the foregoing, such charges are not regulated by RBI; however, few customers do complain about their levy. Since the purpose of this document is to elicit feedback, which in turn can be passed on to the concerned stakeholders, some discussion points on these charges and a few questions thereon have been included. 12.2. Surcharging 12.2.1. When charges payable by the customer vary based on the mode of payment (cash or digital), this practice is termed as ‘surcharging’. Surcharging also happens if charges payable by the customer are dependent on the digital payment channel (debit cards, credit cards or UPI). The practice of surcharging exists ostensibly because of the high MDR imposed on merchants for facilitating acceptance of digital payments. 12.2.2. RBI had earlier advised banks to ensure that merchants on-boarded by them do not pass on MDR charges to customers while accepting payments through debit cards. The same has not been mandated for transactions performed using credit cards and PPIs. 12.2.3. Questions for Feedback

12.3. Convenience Fee 12.3.1. This is an additional fee levied by service providers / online platforms over and above the cost of service. Generally, this fee is levied ‘per unit’ of service availed and may be same for all modes of digital payments. For instance, an online platform may charge convenience fee from customers for booking movie tickets or flight tickets. Customers may prefer to pay these convenience charges (for availing the facility of booking tickets from the comfort of their home) instead of travelling to the company’s booking counters and standing in queues for purchasing the tickets. Convenience fee offers a direct and sustainable source of revenue for such online platforms / service providers, and sometimes, it is the major source of revenue for them. This is seen, for example, in the case of online ticket booking platforms. It helps movie goers to avoid queues at counters and to handle physical cash; it also enables the theatres to serve a large volume of customers without having to employ requisite staff. 12.3.2. Convenience fee is usually a fixed fee irrespective of the booking amount but can vary based on service availed. It also varies from one service provider to another. Often, there is a thin line dividing convenience fee and surcharging for a transaction. 12.3.3. Unlike the surcharge, which is generally not levied in a transparent manner, convenience fee is usually disclosed upfront to the customers by the merchants – the cost of the product and the convenience fee applied are separately disclosed. The convenience fee can come in different guises – internet handling fee, facilitation fee, etc. – but the intent is to recover something more than the cost / price of the product / service. 12.3.4. A digital payment transaction is largely value independent. This means that the same effort and use of infrastructure is involved irrespective of the value of transaction. A transaction to book one or more movie tickets involves the same effort from the user and the service provider. Hence, should the convenience fee be based on number of tickets booked in a transaction, or should it be uniform irrespective of the number of tickets? Alternatively, should it be a mix of the two? These issues need to be thought through. 12.3.5. The maximum MDR for debit card transactions is not related to convenience fee. 12.3.6. Questions for Feedback

13.1. Amongst these discussions is the point as to whether a digital payment transaction be charged based on value? Given that a digital payment transaction is all about a few clicks, should they be value-neutral? In other words, should the charges for a digital payment transaction be the same irrespective of the value of the transaction? This would mean that a transaction worth a rupee or a thousand rupees will have the same charge. Or should the large value users subsidise the cost of usage for a small value transaction? Also, since the effort involved in undertaking a transaction or providing the service for one / few tickets or seats is the same, is additional levy per seat or ticket justified? 13.2. The other debate is about the manner of recovery of charges. Should they be based on ‘marginal cost’ basis where only the additional / delta costs of the merchants are recovered from the users and not those relating to the investments already made. The merchant should be seen to be only recovering her / his genuine costs for facilitating a digital payment transaction and in no situation try to profiteer from the user of the payment instrument / system. 13.3. It is often seen that when a cap or floor on charges is attempted, the entire set of stakeholders get closer to the thresholds, irrespective of the costs actually incurred by them. This poses a regulatory dilemma on intervention or stay afar. 13.4. Yet another aspect worthy of discussion is whether intervention is desirable at all in the way charges are levied and / or recovered from users or merchants or any other stakeholder in the payments value chain. Like the efficient market hypothesis, the charges could be based on demand and supply, and not be subject to any artificial or mandated limits prescribed by the regulators or the Government. 13.5. Questions for Feedback

14.1. The above questions for feedback have been reiterated below for ease of reference: RTGS

NEFT

IMPS

Debit Cards

Credit Cards

PPIs

UPI

Intermediaries

Surcharging

Convenience Fee

Other Aspects

14.2. Specific feedback by way of response to the above questions, including other inputs and suggestions relevant to the topic under discussion, may be provided through (email) on or before October 3, 2022. List of Acronyms Used

1 Government mandated charges. 3 Account here means a bank account or an account linked to a Prepaid Payment Instrument (PPI) 4 Merchants in this case can be individuals or entities, who avail the services of payment service providers to accept payments for the services rendered or products sold. 5 The underlying funds flow here is also from one account to another. However, the customer does not identify the beneficiary’s account in this case. 6 For this paper, Central Banks are considered as a separate category. 7 This is typically the case in a four-party card and UPI system. In a three-party card system, card issuer and acquirer are same. 8 As per the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007, a “system provider” means a person who operates an authorised payment system. The terms ‘Provider’ and ‘Operator’ have been used interchangeably in this discussion paper. 9 Also known by the nomenclature ‘Merchant Service Fee’ (MSF) 10 Non-banks have also been permitted to be members of centralised payment systems like RTGS and NEFT vide RBI notification dated July 28, 2021. The membership type of non-banks is different from that available to banks. Clearing Houses and Primary Dealers are also restricted non-bank members. 11 The settlement of card transactions may happen on T+1 basis. However, the payments to merchants are carried out by the acquirers / intermediaries on T+n basis, where “n” is determined by the agreement the merchants have with these entities. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

পেজের শেষ আপডেট করা তারিখ: