IST,

IST,

Operations and Performance of Commercial Banks

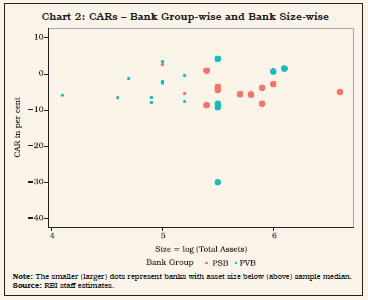

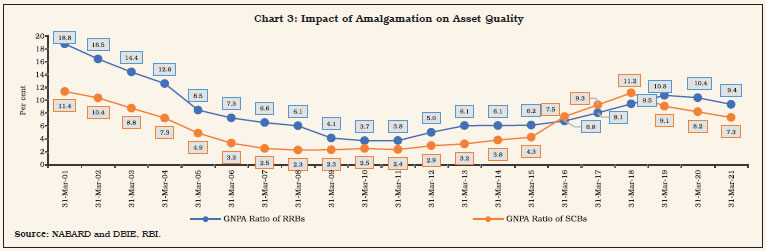

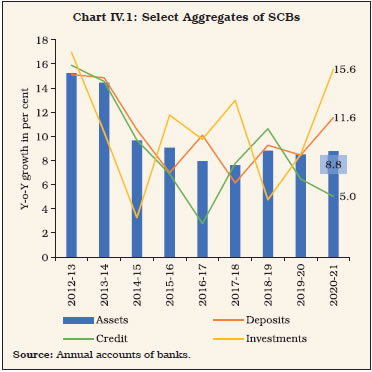

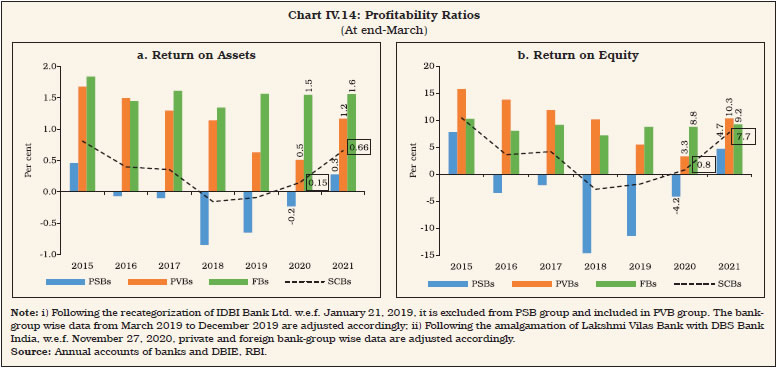

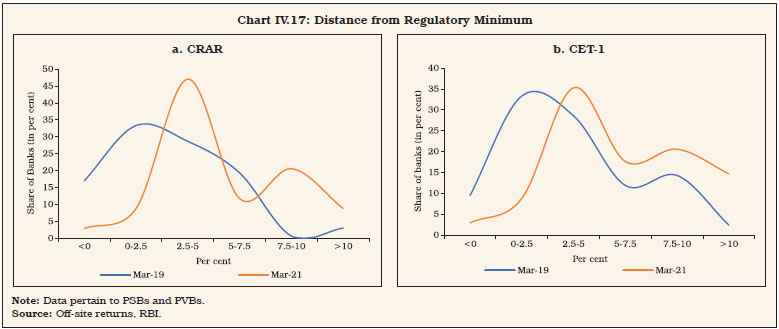

During 2020-21, scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) reported a discernible improvement in their asset quality, capital buffers and profitability, notwithstanding the disruptions of the pandemic. While credit offtake remained subdued, elevated deposit growth on the liabilities side was matched by growth in investments on the assets side. Nonetheless, incipient stress remains in the form of higher restructured advances. Banks would need to bolster their capital positions to absorb potential stress as well as to augment credit flow when policy support is phased out. 1. Introduction IV.1 During 2020-21, the banking sector navigated the disruptions caused by the pandemic and the economic downturn with resilience, cushioned by various policy measures undertaken by the Reserve Bank and the Government. Asset quality improved, partly attributable to imposition of the asset classification standstill. Public sector banks (PSBs) reported net profits after a gap of five years. More generally, the capital position of banks improved, aided by recapitalisation by the government as well as raising of funds from the market. Nonetheless, incipient stress remains in the form of increased proportion of restructured advances and the possibility of higher slippages arising from sectors that were relatively more exposed to the pandemic. Nevertheless, with the green shoots of recovery re-emerging in H1:2021-22, banks are expected to further shore up their financials. IV.2 Against this background, this chapter discusses the operations and performance of the banking sector during 2020-21 and H1:2021-22. Balance sheet developments are analysed in Section 2, followed by an assessment of their financial performance and financial soundness in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Sections 5 to 12 address specific themes relating to sectoral deployment of credit, performance of banking stocks, ownership patterns, corporate governance and compensation practices, foreign banks’ operations in India and overseas operations of Indian banks, developments in payments systems, consumer protection and financial inclusion. Developments related to regional rural banks (RRBs), local area banks (LABs), small finance banks (SFBs) and payments banks (PBs) are analysed separately in Sections 13 to 16. The chapter concludes by bringing together major issues that emerge from the analysis and offers some perspectives on the way forward. IV.3 The consolidated balance sheet of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) accelerated during 2020-21, notwithstanding the pandemic and the contraction in economic activity in the first half of the year. Deposit growth on the liabilities side was matched by investments on the assets side; however, credit offtake remained subdued (Table IV.1 and Chart IV.1). Supervisory data suggest that while nascent signs of recovery are visible in credit growth, deposit growth has slowed down in 2021-22 so far. IV.4 The share of PSBs in total advances as well as in deposits has been declining since 2010-11, while private sector banks (PVBs) have been improving their share.

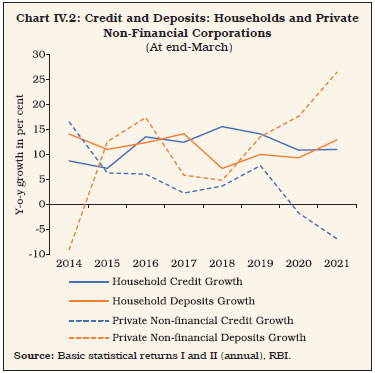

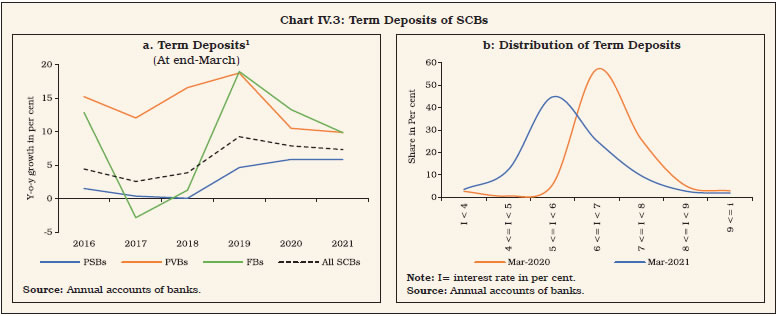

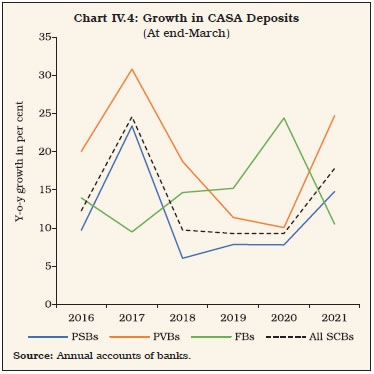

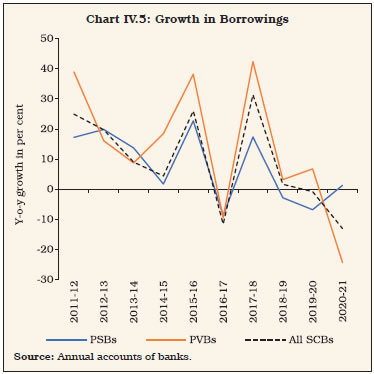

2.1 Liabilities IV.5 During 2020-21, deposit mobilisation by SCBs was the highest in seven years, mainly contributed by the low-cost current account and savings account (CASA) deposits (Chart IV.4). In H1:2021-22, there was a moderation in deposit growth with normalisation of economic activity and rising inflation. IV.6 For the last three years, private non-financial corporations have been net savers, progressively increasing their deposits with SCBs while their credit offtake has remained anaemic. Moreover, the household sector’s deposits—64 per cent of the total as at end-March 2021—also picked up pace (Chart IV.2).  IV.7 With term deposit rates falling across the board, their growth moderated during 2020-21 (Chart IV.3a). Correspondingly, their distribution across interest rates shifted leftwards, with 5-6 per cent interest rate emerging as the modal class (Chart IV.3b).  IV.8 Historically, PVBs have relied heavily on borrowings to supplement their deposits and fuel credit growth. On the other hand, PSBs leveraged their wide deposit base and availability of low-cost CASA deposits to fund their lending. In 2020-21, borrowings of PVBs contracted for the first time since 2016-17, while those of PSBs accelerated after contracting for two consecutive years. Despite robust CASA deposit growth, PSBs raised higher resources through borrowings than the previous year as their credit growth accelerated over the first three quarters of the year (Chart IV.5).    2.2 Assets IV.9 SCBs’ credit growth has decelerated over previous two years, largely reflecting muted demand conditions and risk aversion (Box IV.1). Signs of recovery became visible in H1:2021-22.

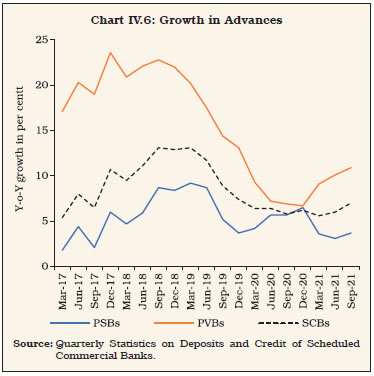

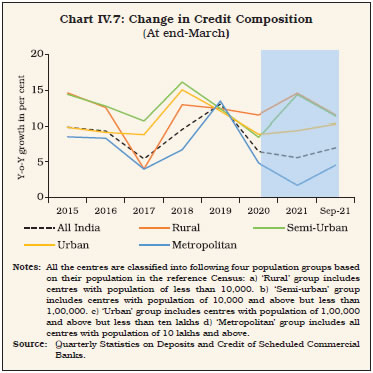

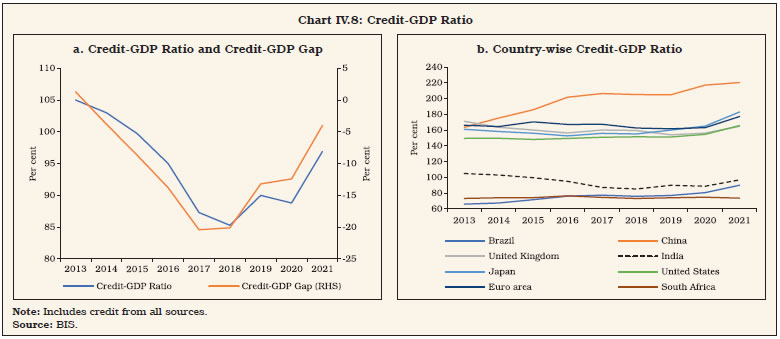

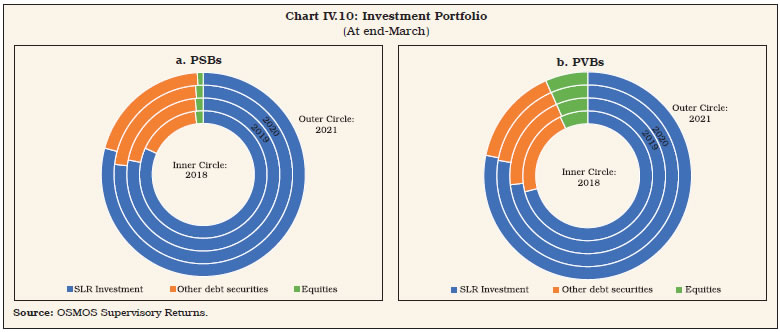

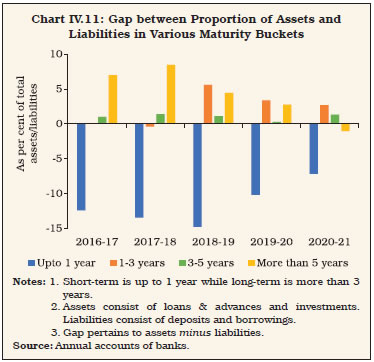

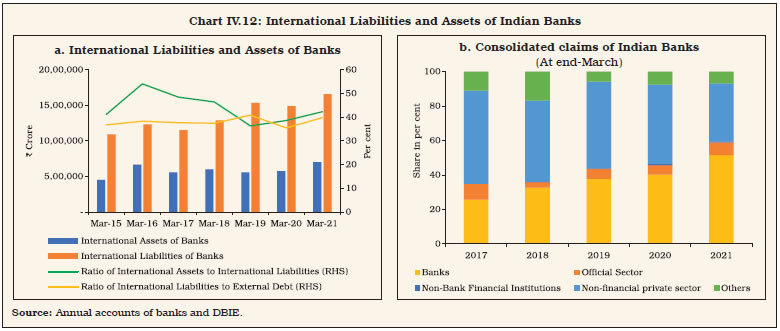

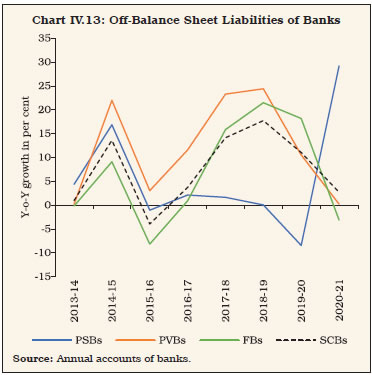

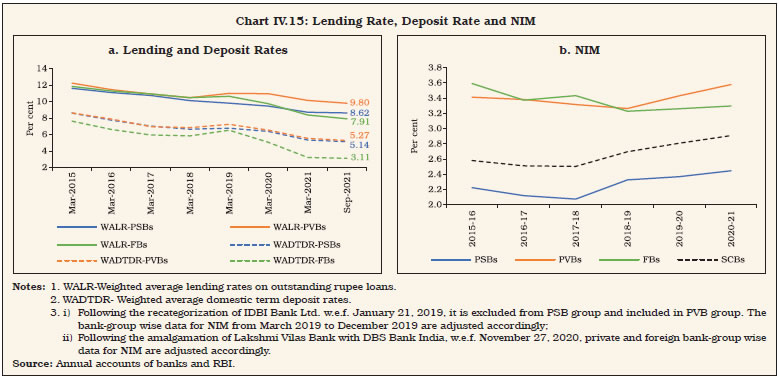

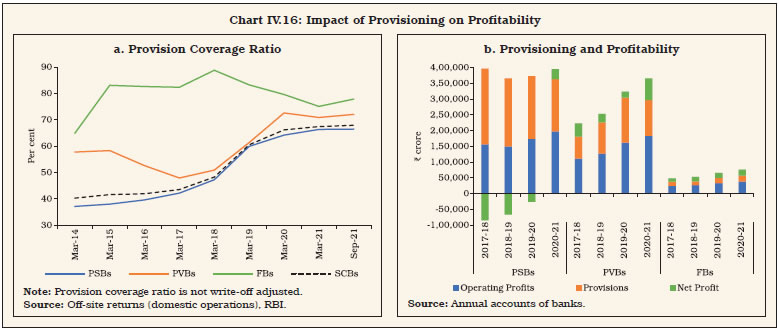

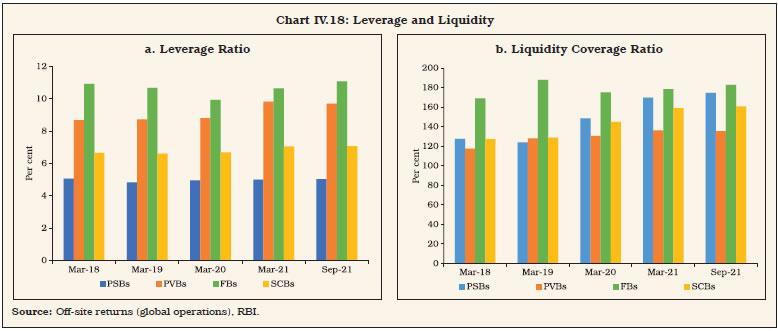

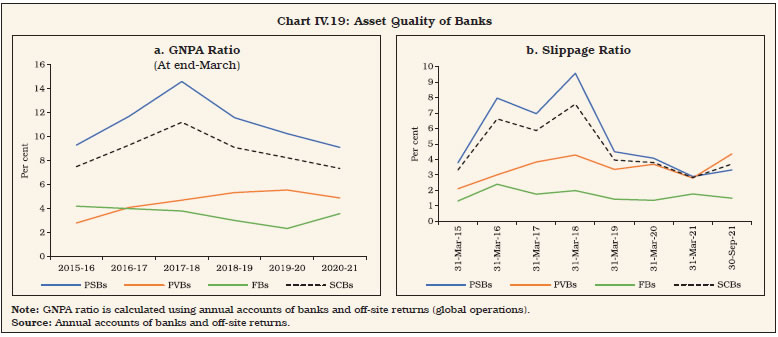

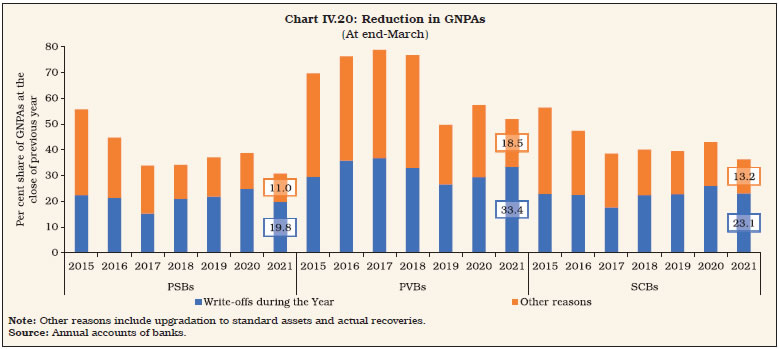

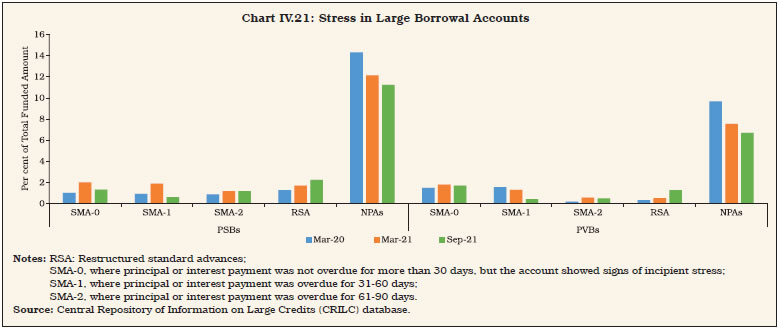

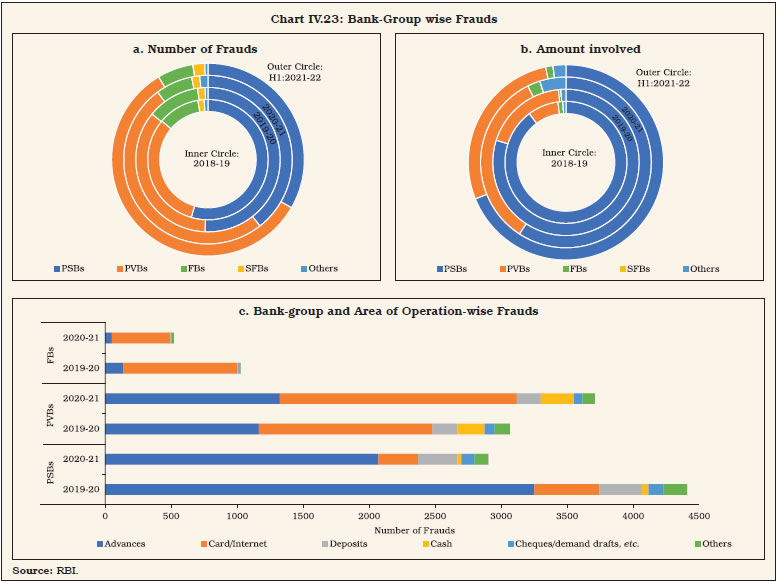

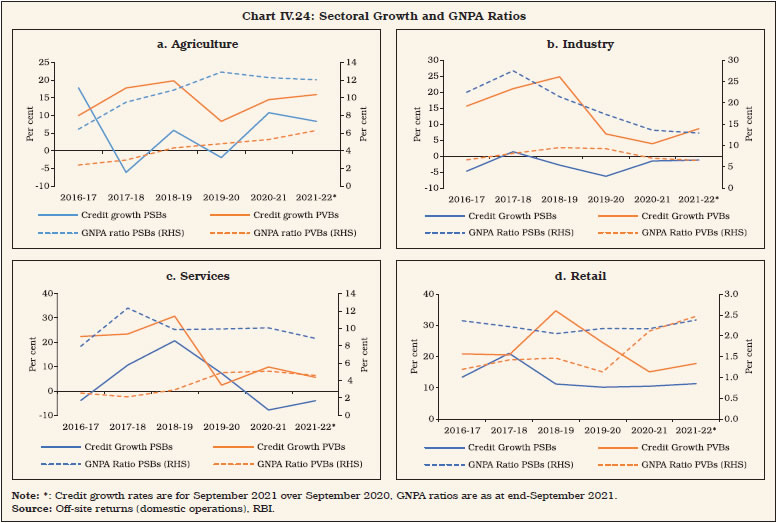

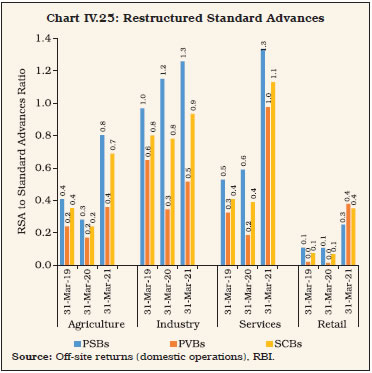

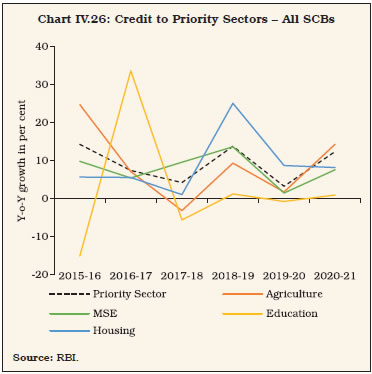

IV.10 Credit growth of PVBs decelerated from Q4: 2019-20 till Q3:2020-21 as the pandemic took its toll. Since Q4:2020-21, however, PVBs’ credit showed signs of revival (Chart IV.6).  IV.11 Within population groups, the relatively higher credit growth to rural and semi-urban areas after the outbreak of COVID-19 is a bright spot (Chart IV.7). While PSBs remained the major contributor of rural lending, given their reach and accessibility, the share of PVBs has also climbed up.   IV.12 The credit-to-GDP ratio increased to a five-year high, narrowing the credit-GDP gap (Chart IV.8a). India’s credit-to-GDP ratio is still markedly lower than the G20 average (Chart IV.8b). IV.13 As the share of advances in total assets fell, that of investments increased in an environment of risk aversion and limited profitable lending avenues. This resulted in a decline in the credit-deposit (C-D) ratio and a corresponding elevation in the investment-deposit (I-D) ratio, especially in incremental terms (Chart IV.9). IV.14 Central Government and State Government securities were preferred by both PSBs and PVBs during 2020-21, indicating their preference for safer investments. Consequently, the share of other debt securities in PSBs’ total portfolio declined after increasing for three consecutive years (Chart IV.10). 2.3 Maturity Profile of Assets and Liabilities IV.15 Mismatches in the maturity of assets and liabilities are intrinsic to banking business, but they have implications for liquidity, profitability and risk exposures. During 2020-21, while the negative gap in the maturity bucket of up to one year moderated, the positive gap in the maturity bucket of more than five years turned negative as banks attracted less short-term CASA deposits and more longer-term deposits (Chart IV.11).   IV.16 In the case of borrowings, PSBs and PVBs displayed widely contrasting patterns. The share of short-term and long-term borrowings increased year-on-year in the case of PSBs, while PVBs relied more on borrowings with maturity between one and five years (Table IV.2).  2.4 International Liabilities and Assets IV.17 The total international liabilities of banks located in India expanded in 2020-21 on the back of rupee denominated deposits and equities held by non-resident Indians (NRIs) (Appendix Table IV.9). The sizeable increase in international assets, on the other hand, was led by their loans and debt securities (Appendix Table IV.10). However, international assets of banks in India (including foreign banks) were only 42 per cent compared to their international liabilities (Chart IV.12a). IV.18 During the period under review, the share of claims of Indian banks (including their domestic and foreign branches) shifted away from non-financial private institutions and favoured other banks (Appendix Table IV.11 and Chart IV.12b). The country-composition of international claims remained stable, with the share of the top five out of six countries against which Indian banks held the highest share of claims increasing further (Appendix Table IV.12). 2.5 Off-Balance Sheet Operations IV.19 The size of contingent liabilities of all SCBs relative to their total on-balance sheet exposures declined in 2020-21, after increasing in the previous year. For PSBs, however, the share increased as their forward exchange contracts that include all admissible derivative products increased by more than 40 per cent. For FBs, while off-balance sheet exposures decreased, they remained more than nine times their total liabilities (Chart IV.13). The overall deceleration in banks’ contingent liabilities was on account of muted growth in their forward exchange contracts in line with subdued foreign exchange transactions (Appendix Table IV.2).   IV.20 The financial performance of SCBs in 2020-21 was marked by a discernible increase in profitability as their income remained stable but expenditure declined. This was in sharp contrast with the past five years during which PSBs incurred losses and profitability of PVBs was declining (Chart IV.14). IV.21 The total income of banks remained stable, despite a marginal decline in its largest component viz. interest income, in an environment characterised by low credit offtake and interest rates (Table IV.3). The fall was cushioned by a sizeable increase in income from investments. Income from trading also accelerated, as banks booked profits on falling G-Sec yields. IV.22 The contraction in SCBs’ expenditure was led by a decline in the interest expended on deposits and borrowings on account of moderation in interest rates and contraction in total borrowings. Across bank groups, the transmission of policy rate changes to term deposit rates was highest for FBs (Chart IV.15 a). At the system level, interest earned by banks outpaced their interest expenses, and hence the net interest margin (NIM) improved (Chart IV.15 b).    IV.23 Banks were required to maintain additional provisions of at least 10 per cent on moratorium amounts, which was allowed to be spread out across two quarters viz. Q4:2019-20 and Q1:2020-21. Most banks, especially PVBs, frontloaded the required provisions in the March 2020 quarter resulting in a higher provision coverage ratio for the year. Combined with lower slippage, this muted the provision requirements during 2020-21 which helped in boosting banks’ profitability (Chart IV.16). IV.24 Profitability of banks, measured in terms of spread between return on funds and cost of funds, improved with the decline in the latter exceeding that in the former. The improvement was especially evident in PSBs, while niche banks in the SFB and PB categories could not maintain their spreads (Table IV.4). IV.25 During 2020-21, SCBs bolstered their capital positions, and also improved their asset quality, liquidity and leverage ratios, despite the pandemic. The number of banks under the Reserve Banks’s prompt corrective action (PCA) framework reduced from four at end-March 2020 to one at end-September 2021, reflecting bank-level as well as overall improvement in SCBs’ soundness indicators. 4.1 Capital Adequacy IV.26 The capital to risk-weighted assets ratio (CRAR) of SCBs has improved sequentially every quarter from end-March 2020 to reach 16.6 per cent at end-September 2021 (Table IV.5). This was essentially driven by a rise in core capital across bank groups, attributable to higher retained earnings, recapitalisation of PSBs by the government and raising of capital from the market. A slowdown in the accumulation of risk weighted assets (RWAs) of both PSBs and FBs helped to boost their capital ratios. IV.27 The number of banks breaching the regulatory minimum requirement of CRAR (including capital conservation buffer) (10.875 per cent) declined to one during 2020-21 from three in the previous year. The fatter right tails for end-March 2021 distributions as compared with those for 2019 imply that a bigger share of banks maintained higher CRAR and CET-1 ratio, with the peak between 2.5 to 5 per cent over andabove the minimum (Chart IV.17)3. Although the implementation of the last tranche of 0.625 per cent of capital conservation buffer (CCB) was deferred till October 1, 2021, banks proactively raised more capital to be in readiness for the imminent transition. IV.28 Resource mobilisation by banks through public and rights issues increased sharply in 2020-21, reflecting the follow-on public offer (FPO) of equity capital by a PVB to meet its capital requirements (Table IV.6). IV.29 In September 2020, the Parliament approved ₹20,000 crore capital infusion for PSBs which was fully disbursed by April 1, 2021. Since 2014, the government has infused ₹3.43 lakh crore in PSBs. In the Union Budget of 2021-22, the government has proposed to infuse another tranche of ₹20,000 crore into PSBs, which will help in augmenting their capital. IV.30 The resources raised by PSBs through private placement almost doubled during 2020-21. In 2021-22 so far, both PSBs and PVBs have resorted to this route for raising capital (Table IV.7).  4.2 Leverage and Liquidity IV.31 The leverage ratio (LR), calculated as the ratio of tier-1 capital to total exposures, constrains the build-up of leverage by banks. Despite regulatory moderation in October 2019 requiring banks to maintain 4 and 3.5 per cent ratios for domestic systemically important banks and other banks, respectively as compared to 4.5 per cent earlier, the LR of SCBs rose for the second consecutive year during 2020-21. While the improvement was spread across all bank groups, it was led by a sharp improvement in the tier-1 capital of PVBs (Chart IV.18 a). IV.32 The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) - designed to help banks withstand liquidity pressures in the short-term - requires banks to maintain high quality liquid assets (HQLAs) to meet 30 days’ net outgo under stressed conditions. In March 2020, banks were allowed to avail funds under the marginal standing facility by dipping into the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) by up to an additional one per cent of their net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) for three months. This dispensation was progressively extended up to December 31, 2021 to enable banks to meet their LCR requirements and provide comfort on their liquidity needs and will expire thereafter. Additionally, the LCR requirement for SCBs was brought down from 100 per cent to 80 per cent in April 2020 and was gradually restored in two phases by April 1, 2021. Notwithstanding the regulatory relaxation, banks continued to maintain LCR above 100 per cent: the ratio increased from 145 per cent at end-March 2020 to 158.9 per cent by end-March 2021 and 160.9 per cent by end-September 2021 (Chart IV.18 b).  4.3 Non-Performing Assets IV.33 The moderation in GNPA ratios of banks that began in 2019-20, continued during the period under review to reach 7.3 per cent by end-March 2021. Provisional supervisory data suggest a further moderation in the ratio to 6.9 per cent by end-September 2021. During 2020-21, this improvement was driven by lower slippages, partly due to the asset classification standstill. With the decline in delinquent assets, their provision requirements also dropped and the net NPA ratio of PSBs and PVBs eased from the previous year. On the contrary, FBs reported increasing accretions to NPAs and deteriorating asset quality due to amalgamation of a troubled PVB with an FB (Chart IV.19).  IV.34 As observed since 2018, write-offs were the predominant recourse for lowering GNPAs in 2020-21 (Table IV.8 and Chart IV.20). In the case of FBs, the contribution of upgradation improved substantially, but it was not enough to offset fresh slippages. IV.35 Consistent with the improvement in asset quality, the proportion of standard assets to total advances of SCBs increased in 2020-21, largely because of the improved performance of PVBs (Table IV.9). Within standard assets, the share of restructured standard advances (RSA) increased from 0.4 per cent at end March 2020 to 0.8 per cent at end-March 2021, largely representing the onetime restructuring scheme for standard advances announced by the Reserve Bank in August 2020. The RSA further increased to 1.8 per cent at end September 2021 due to restructuring scheme 2.0 for retail loans and MSMEs which does not entail an asset classification downgrade.  IV.36 The share of large borrowal accounts (exposure of ₹5 crore or more) in total advances declined to 51 per cent at end-March 2021 from 54.2 per cent a year ago. Their contribution to total NPAs also declined in tandem from 75.4 per cent to 66.2 per cent during the same period. The special mention accounts-2 (SMA-2) ratio, which signals impending stress, has risen across bank groups since the outbreak of the pandemic. The RSA ratio has also increased during the same period, partly reflecting the impact of resolution framework (RF) 1.0 and 2.0 (Chart IV.21).  4.4 Recoveries IV.37 During 2020-21, all the recovery channels, most notably Lok Adalats, witnessed a sizeable decline in the cases referred for resolution (Table IV.10). Even though initiation of fresh insolvency proceedings under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) of India was suspended for a year till March 2021 and COVID-19 related debt was excluded from the definition of default, it constituted one of the major modes of recoveries in terms of amount recovered. Allowing pre-pack resolution window for MSMEs is expected to assuage the mounting pressure of pending cases before NCLTs, reducehaircuts and improve declining recovery rates4. IV.38 Another important mode of asset resolution for banks, especially PVBs, has been sale of NPAs to asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) by taking haircuts. In recent years, however, the preference of banks has shifted to alternative avenues, with asset sales declining as a proportion to outstanding GNPAs across bank groups. This was partly due to the worsening acquisition cost of ARCs as a proportion of book value of assets, reflecting higher haircuts and lower realisable values in respect of their acquired assets (Chart IV.22). IV.39 The recovery of security receipts (SRs) issued by ARCs is a critical indicator of their performance. Since 2018, the Reserve Bank has been disincentivising banks from holding SRs in excess of 10 per cent of the transaction value of sale of stressed assets through increasedprovisions.5 Consequently, the share of SRs subscribed to by banks has decreased over the years, and their share hovered around 58per cent in 2019-20 and 2020-216. The share of ARCs in SR holdings has declined over the years, with the investor base having gradually diversified with an increasing share of foreign institutional investors and other qualified buyers (Table IV.11).  4.5 Frauds in the Banking Sector IV.40 Apart from eroding customer confidence, frauds present multiple challenges for the financial system in the form of reputational risk, operational risk and business risk. During 2020-21, the reported number of cases of frauds declined (Table IV.12). In terms of amount involved, a bulk of these cases occurred earlier but were reported during the year 2020-21 (Table IV.13). IV.41 In terms of area of operations, an overwhelming majority of cases reported during 2020-21 in terms of number and amount involved related to advances, while frauds concerning card or internet transactions made up 34.6 per cent of the number of cases. IV.42 In 2020-21, there was a marked increase in frauds related to PVBs, both in terms of number as well as the amount involved. During H1:2021-22, PVBs accounted for more than half of the number of reported fraud cases (Chart IV.23a). In value terms, however, the share of PSBs was higher, indicating predominance of high value frauds (Chart IV.23b). While the major share of loans-related cases pertained to PSBs, PVBs accounted for a majority of card/ internet and cash-related cases (Chart IV.23c).  4.6 Enforcement Actions IV.43 In order to separate enforcement action from the supervisory process and in accordance with international best practices, the Enforcement Department was created in the Reserve Bank in 2017. The department is entrusted with ensuring uniformity and consistency in enforcement of regulations and engendering compliance in the regulated entities (REs). During 2020-21, the number of instances of imposition of penalty reduced, with enforcement action being undertaken against 11 SCBs. Monetary penalties were imposed for non-compliance with provisions or contravention of certain directions issued by the Reserve Bank, including frauds classification and reporting, exposure norms and IRAC norms, interest rate on deposits and lending to MSMEs (Table IV.14). 5. Sectoral Bank Credit: Distribution and NPAs IV.44 Headline credit growth remained anaemic during 2020-21, although sectorally some bright spots appeared: agriculture credit revived from a sharp deceleration of the previous year; PVBs increased their lending to the services sector; and PSBs cushioned the deceleration in total retail credit growth, albeit partly. On the other hand, credit growth to services by PSBs and to retail by PVBs slowed down amidst rising NPA ratios (Chart IV.24). IV.45 A drill down into the data reveals that although credit to large industries contracted, their medium-sized counterparts received sharply higher credit flows, incentivised by the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme(ECLGS)7. The higher NPAs of large industrial borrowers at the end of March 2021 as compared to better asset quality of medium enterprises may also be a driving factor. Within services, credit growth to trade surpassed its pre-pandemic growth rate in 2020-21. Remarkably, its share in services sector credit also grew sharply in 2020-21. After the IL&FS event, NBFCs—especially those with lower ratings— found raising resources from the market difficult and turned to banks. SCBs’ credit to NBFCs grew in double digits during 2015-16 to 2019-20 but decelerated in 2020-21 on a high base (Table IV.15).  IV.46 During 2020-21, retail loan portfolios of banks outgrew their services sector lending, aided by double digit acceleration in housing loans- the biggest component of retail loans. Vehicle loans gained traction, reflecting consumer interest after companies announced substantial discounts on automobiles. IV.47 The RSA ratio of SCBs had been decelerating for five consecutive years since 2015 on better asset quality recognition by banks after the asset quality review (AQR). With the restructuring scheme announced in August 2020 by the Reserve Bank in response to the pandemic, the RSA ratio, especially of services and retail loans increased sharply in 2020-21, led by contact-intensive services (Chart IV.25). 5.1 Priority Sector Credit IV.48 Priority sector lending (PSL) accelerated in 2020-21, primarily driven by revival in credit to agriculture—especially Kisan Credit Card (KCC) loans—and micro and small enterprises (MSEs) by both PSBs and PVBs (Chart IV.26 and Appendix Table IV.3). IV.49 PSL, which is typically pro-cyclical, is also influenced by bank-specific characteristics such as asset quality of the PSL vis-à-vis non-priority sector loans, size of the lending bank and their branch network (Box IV.2).  IV.50 During 2020-21, all bank groups managed to achieve the overall PSL targets. Shortfalls were observed in certain sub-targets by PSBs (micro enterprises) and PVBs (agriculture; small and marginal farmers (SMFs) and non-corporate individual farmers) (Table IV.16). A phased increase in PSL targets for SMFs and weaker sections as per the revised PSL guidelines issued in September 2020 is expected to deepen credit penetration to thesesectors12.

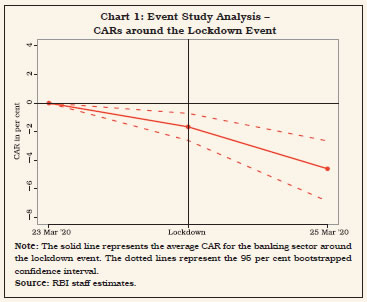

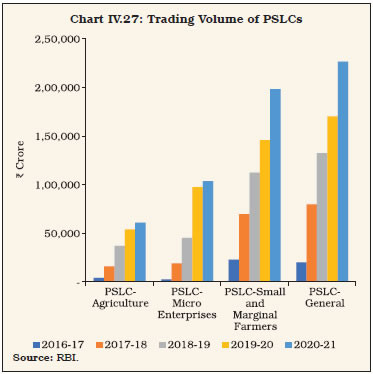

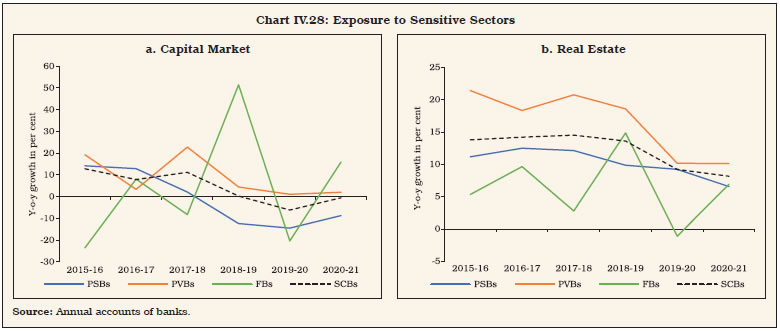

IV.51 The total trading volume of PSLCs grew by 26 per cent to ₹5,89,163 crores during 2020-21. Among the four PSLC categories, significant growth was recorded in case of PSLC-General and PSLC-Micro Enterprises (Chart IV.27). IV.52 The weighted average premiums (WAPs) for PSLCs increased year-on-year by 11 to 44 basis points across categories in 2020-21, with PSLC-SMF and PSLC-A categories commanding significantly higher premiums than PSLC-G and PSLC-ME. During H1:2021-22, the WAP on PSLCs-ME increased sharply due to change in the definition of MSMEs. The increase in WAP across other categories may be attributed to COVID-related stress (Table IV.17). IV.53 While the share of priority sector accounts in total bank lending increased only marginally from 35 per cent in 2019-20 to 36 per cent in 2020-21, their share in total GNPAs increased markedly from 32.8 per cent to 40.5 per cent during the same period, led by delinquencies in agricultural and micro and small enterprises PSL (Table IV.18).  5.2 Credit to Sensitive Sectors IV.54 Banks’ exposure to sensitive sectors decelerated during 2020-21. Nevertheless, it grew at a higher pace than overall credit growth, led by the real estate sector, especially by PVBs and FBs. Banks’ capital market exposure contracted for the second consecutive year (Chart IV.28 and Appendix Table IV.4).  6. Performance of Banking Stocks IV.55 After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, equity markets in India fell sharply, tracking global cues. Banking sector stocks were hit hard, reflecting investors’ concerns about their financial health, although the impact was not homogenous across banks and bank groups. Subsequently, in response to the policy measures initiated by the Reserve Bank and the Government of India, stock prices revived (Chart IV.29) IV.56 Empirical evidence suggests that stock prices of banks with weak balance sheets were hammered down more by investors in the pandemic shock (Box IV.3)

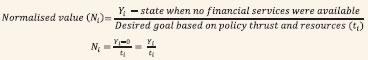

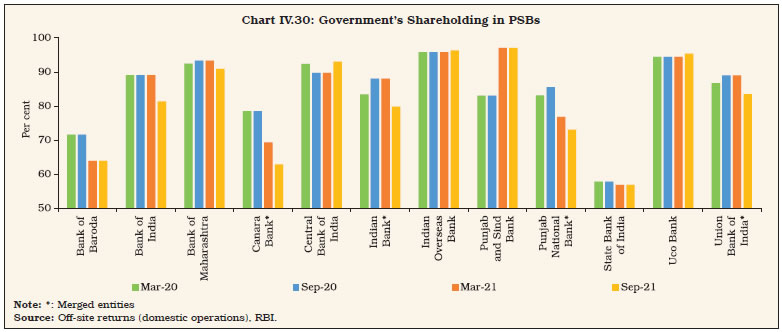

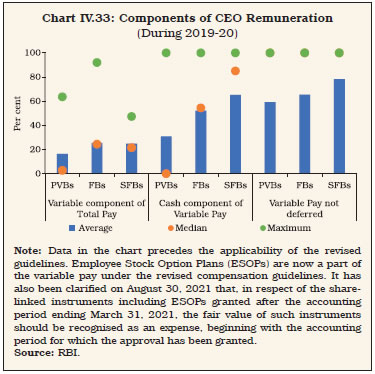

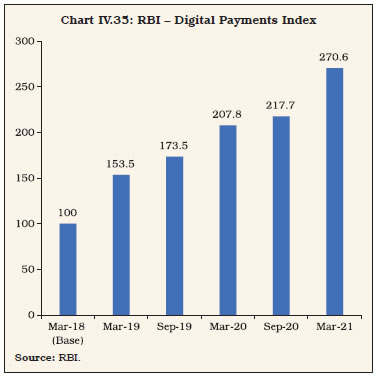

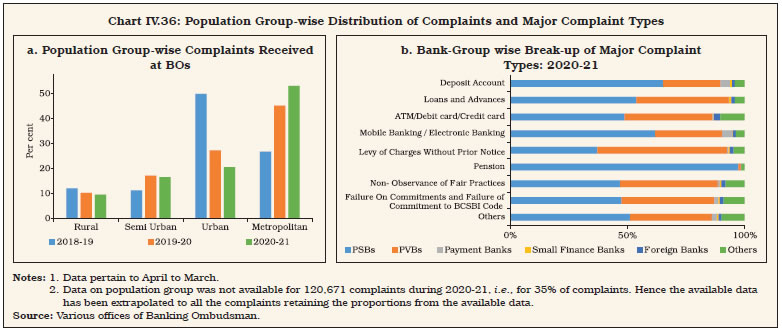

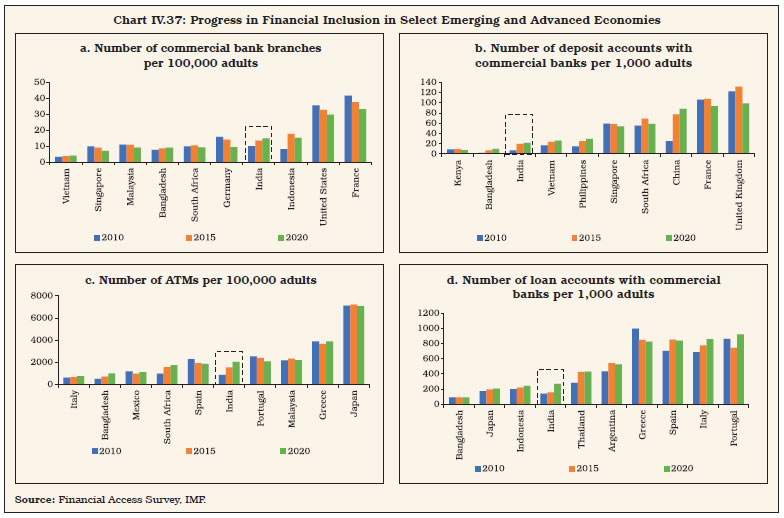

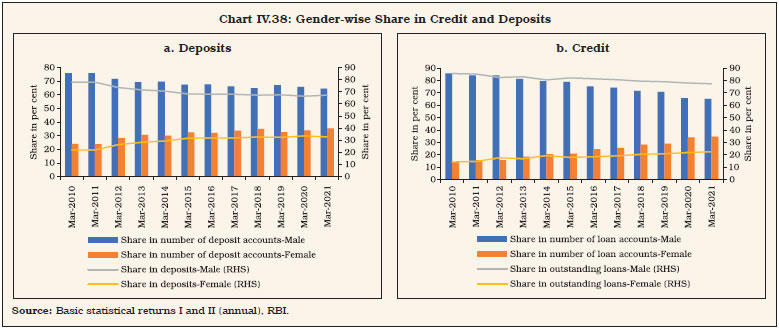

7. Ownership Pattern in Commercial Banks IV.57 Government ownership in Canara Bank, Punjab National Bank, Indian Bank and Union Bank of India increased substantially following the amalgamation of ten PSBs into four, effective from April 1, 202016. During H2:2020-21, the government’s shareholding increased in Punjab and Sind Bank due to recapitalisation17 and decreased in Bank of Baroda, Canara Bank, Punjab National Bank and State Bank of India, owing to capital raising through private placements (Chart IV.30). Furthermore, as at end-September 2021, government shareholding decreased in Bank of India, Bank of Maharashtra, Canara Bank, Indian Bank, Punjab National Bank and Union Bank of India on account of raising of fresh equity from the market. Capital infusions planned for PSBs during 2021-22 are expected to change their ownership pattern further18.  IV.58 During the year, one private sector bank, Lakshmi Vilas Bank Limited, amalgamated with a foreign bank, DBS Bank India Limited, with effect from November 27, 2020. With this, 21 PVBs were operational in India as at end-March 2021. In terms of foreign investments, non-residents’ shareholding was well within the limits of 74 per cent for PVBs including Local Area Banks (LABS) and Small Finance Banks (SFBs) and 20 per cent for PSBs (Appendix Table IV.5). 8. Corporate Governance IV.59 Effective governance and balanced compensation practices in banks are important risk mitigation tools as they boost depositors’ confidence and also reinforce financial stability. Following the discussion paper on ‘Governance in Commercial Banks in India’ issued in June 2020 and the feedback received thereon, the Reserve Bank issued an interim set of instructions addressing several operational subjects on April 26, 2021. 8.1 Composition of Boards IV.60 Apart from ensuring competency, diversity and meeting the fit-and-proper criterion, appointment of independent directors goes a long way in ensuring board effectiveness. Most PVBs in India have achieved this in varying degrees, with the dominant presence of independent directors on their boards as well as in their key supervisory committees, including the Audit Committee of the Board (ACB), Risk Management Committee of the Board (RMCB) and Nomination and Remuneration Committee (NRC) (Chart IV.31). IV.61 It is also necessary to limit the presence of management on the board and key supervisory committees to ensure functional independence. Ensuring that the Chair of the board is not a member of these committees helps minimise role conflicts. The share of PVBs where the Chair is not a member of an ACB increased to 47 per cent at end-March 2021 from 35 per cent a year ago. However, the share remained unchanged at 29 per cent in the case of RMCBs19.  8.2 Executive Compensation IV.62 The compensation paid to a bank Chief Executive Officer (CEO) in comparison to a representative bank employee varies greatly across different bank groups. For PSBs, on an average, CEOs earn 3 times the typical employee20, while the same was as high as 75 times in the case of SFBs and 67 times in the case of PVBs. The corresponding multiple was low for FBs as the remuneration received by employees is relatively high. The variation across bank groups remained consistent through 2018-19 and 2019-20 (Chart IV.32). IV.63 Revised guidelines on compensation21 require that the compensation of CEOs / Whole Time Directors (WTDs) / Material Risk Takers (MRTs) must be adjusted for all types of risk, their outcomes and time horizons. Moreover, the mix of cash, equity and other forms of payment must be consistent with risk alignment, wherein the variable pay component should be in the range of 50 to 75 per cent of the total pay, a minimum of 60 per cent of which should be under deferral arrangements. The cash component of variable pay is also capped between 33 to 50 per cent22 under the revised guidelines (Chart IV.33).   9. Foreign Banks’ Operations in India and Overseas Operations of Indian Banks IV.64 During 2020-21, the number of FBs operating in the country reduced as compared to a year ago23, however, total branches of FBs increased due to amalgamation of Lakshmi Vilas Bank with DBS Bank, with effect from, November 27, 2020 (Table IV.19). On the other hand, PSBs have been reducing their overseas presence for the last three and a half years to achieve greater cost efficiency. PVBs also shut down their less profitable operations abroad during the year (Appendix Table IV.6). 10. Payment Systems and Scheduled Commercial Banks IV.65 The payment systems landscape in India is undergoing transformation due to rapid technological advancements and innovations, complemented by supportive regulatory policies. The Reserve Bank’s Payment and Settlement Systems: Vision 2019-2021 envisaged payment systems that are not just safe and secure, but are also efficient, fast and affordable. In addition, there has been a greater thrust by the government for rapid adoption of digital payment services by all segments of the society. IV.66 Digital modes of payments have grown by leaps and bounds over the last few years. As a result, conventional paper-based instruments such as cheques and demand drafts now constitute a negligible share (Chart IV.34). IV.67 The growth in volume of total payments decelerated to 26.7 per cent during 2020-21 from 43.7 per cent a year ago. In terms of value, total payments contracted for the second consecutive year, mainly due to decline in value of transactions via RTGS and paper-based instruments (Table IV.20).  10.1 Digital Payments IV.68 In recent years, the Reserve Bank has been encouraging wider adoption of digital modes of payments and strengthening of the required infrastructure. The pandemic provided a fillip to the faster adoption of retail digital payments. 24x7x365 availability of Centralised Payment Systems (CPS) i.e., National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT) and Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS), with effect from December 2019 and December 2020, respectively, reduced risks and enhanced efficiency of the entire payments ecosystem. Subsidies provided through the Payment Infrastructure Development Fund (PIDF), operationalised in January 2021, have helped to develop infrastructure in Tier-3 to Tier-6 centres and north-eastern states and are expected to give a boost, going forward. Granting non-bank Payment System Providers (PSPs)24 direct access to the CPS will widen the reach of digital financial services to all segments of users. IV.69 RTGS, which facilitates high value transactions on real time basis, dominates the digital payments space in value terms. On the other hand, Unified Payments Interface (UPI) from the retail segment has a majority share in transaction volume. The robust growth in transactions using innovative payment systems such as National Electronic Toll Collection (NETC), BHIM Aadhaar Pay and Aadhaar Enabled Payment System (AePS) points to greater acceptability of contactless payments during the year (Table IV.20). To measure the progress of digitisation and assess the deepening and penetration of digital payments, the Reserve Bank launched a composite Digital Payments Index (DPI) in January 2021, comprising five broad parameters (weights indicated in brackets) – (i) payment enablers (25 per cent); (ii) payment infrastructure – demand-side factors (10 per cent); (iii) payment infrastructure – supply-side factors (15 per cent); (iv) payment performance (45 per cent); and (v) consumer centricity (5 per cent). The index is computed semi-annually, with March 2018 as the base period (Chart IV.35).  10.2 ATMs IV.70 During 2020-21, the total number of automated teller machines (ATMs) (on-site and off-site) operated by SCBs increased for the second consecutive year after declining in 2018-19. The number of PSB ATMs, however, declined in their pursuit of greater cost efficiency by leveraging network externalities (Table IV.21, Appendix Table IV.7). IV.71 The densely populated urban and metropolitan areas accounted for a majority—56.3 per cent—share in total SCBs’ ATMs at end March 2021. While ATMs of PSBs were more evenly distributed across geographies, those of other bank-groups were skewed towards urban and metropolitan areas. In contrast, a majority of whi te label ATMs (WLAs) (around 85 per cent) were concentrated in rural and semi-urban areas (Table IV.22). 11. Consumer Protection IV.72 The Reserve Bank strives to ensure bank customer protection through an efficient and effective grievance redressal mechanism. With the advent of technology-based banking products and growing usage of these products by vulnerable sections of the society, financial literacy, consumer protection and awareness assume critical importance. The launch of the Reserve Bank - Integrated Ombudsman Scheme (RB-IOS) on November 12, 2021 aims at developing a hassle-free grievance redressal mechanism for customers of the entities regulated by the Reserve Bank. The Scheme, while doing away with the jurisdictions of each ombudsman office, covers customer complaints on all areas of ‘deficiency in services’ rendered by the REs and as defined in the Scheme, except those mentioned in the exclusion list. IV.73 During 2020-21, the number of complaints with Banking Ombudsman (BO) rose at a lower pace relative to the preceding year, with grievances pertaining to ATMs/debit cards, mobile/electronic banking and credit cards contributing 42.5 per cent of the total complaints (Table IV.23). IV.74 The share of complaints emanating from urban and metropolitan areas accounted for more than 73 per cent of the total complaints received during 2020-21. Moreover, the share of complaints from metropolitan customers almost doubled in 2020-21 over 2018-19 levels, while the share of complaints from urban customers reduced significantly during the same period (Chart IV.36a). IV.75 PSBs and PVBs accounted for more than three-fourth of the total complaints received during 2020-21. Almost all pension-related complaints were filed against PSBs, which are the traditional preference of pensioners. On the other hand, a large share of complaints (55 per cent) relating to levy of charges without prior notice were filed against PVBs (Chart IV.36b, Appendix Table IV.8). IV.76 Deposit insurance plays a crucial role in protecting the interests of small depositors and thereby ensuring public confidence in the banking system. The Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) extends deposit insurance to all commercial banks including LABs, PBs, SFBs, RRBs and co-operative banks. By end-March 2021, 98.1 per cent depositors were insurance-protected under the ₹5 lakh cover, with the amount of deposits covered by insurance close to 51 per cent of the total (Table IV.24).  IV.77 The size of the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF), which is used for settlement of claims of depositors of banks taken into liquidation/amalgamation stood at ₹1,29,904 crore as on March 31, 2021, yielding a reserve ratio of 1.70 per cent from 1.61 per cent a year ago25. Moreover, claims amounting to ₹993 crore were processed and sanctioned during 2020-21, out of which claims amounting to ₹564 crore were in respect of nine co-operative banks. The net outgo of funds towards settlement of claims was, however, lower on account of recovery of ₹569 crore during 2020-21. 12. Financial Inclusion IV.78 Financial inclusion acts as a driver of balanced economic growth. The latest Financial Access Survey (FAS) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)26 highlights the progress made by India in dealing with the last mile problem of financial inclusion and increasing the popularity of financial products in the previous decade. The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) and its linkage with Aadhar and mobile phones created the JAM trinity, which was a game changer not only for the welfare schemes under direct benefit transfers (DBTs) but also for financial inclusion. Over the last decade, India has taken long strides in expanding the number of commercial bank branches and deposit accounts, on a scale comparable with other emerging market economies (EMEs), although below levels achieved by advanced economies (AEs) (Chart IV.37a and b). With increase in banking outreach, the number of ATMs per 100,000 adults has also grown, however, penetration remained low in an international comparison (Chart IV.37c). The number of loan accounts with commercial banks per 1,000 adults has also remained lower than country peers (Chart IV.37d). IV.79 The National Strategy for Financial Inclusion 2019-2024 (NSFI) and the National Strategy for Financial Education 2020-2025 (NSFE) was released by the Reserve Bank in January 2020 and August 2020, respectively, which provide a road map for accelerating the process of financial inclusion and promoting financial literacy and consumer protection. The Reserve Bank introduced the Financial Inclusion Index (FI Index) in August 2021 to monitor the progress of policy initiatives to promote financial inclusion (Box IV.4).  IV.80 Two distinct pillars of financial inclusion progress in India are: (a) advancement in digital technology (FinTech); and (b) greater participation of women. Financial inclusion acts as a key facilitator for reducing gender inequality and helps engender women’s economic empowerment. As of December 15, 2021, 24.54 crore bank accounts were opened for women beneficiaries under PMJDY, accounting for 55.6 per cent of the total account holders under the scheme. Over the last decade, the number of loan accounts and outstanding loans of female borrowers grew at a CAGR of 43.2 per cent and 22.7 per cent, as against 29.0 per cent and 16.4 per cent, respectively, for male borrowers. The number of deposit accounts and deposit balances of females also grew at a faster rate than that of males, indicating reduced gender disparity in the usage of formal financial services (Chart IV.38). Women-centric financial products and alternative delivery channels such as women business correspondents (BCs) and women self-help groups (SHGs), helped in this direction. Notwithstanding these developments, further progress needs to be made to achieve greater financial equality and inclusion of women.

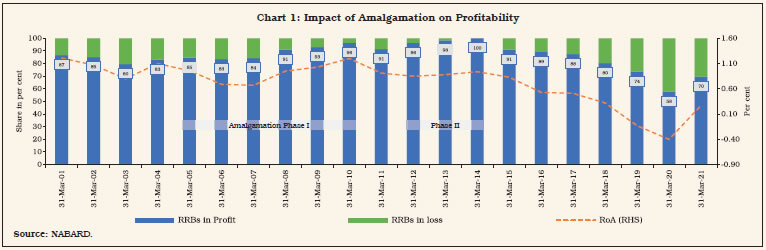

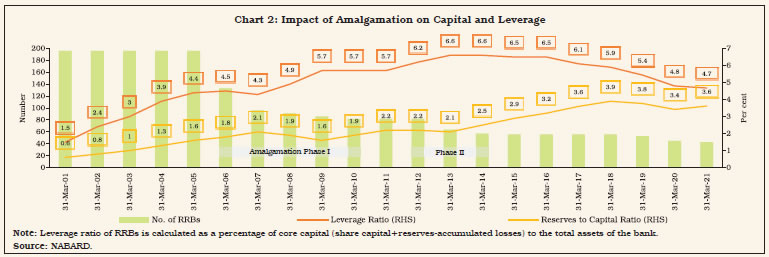

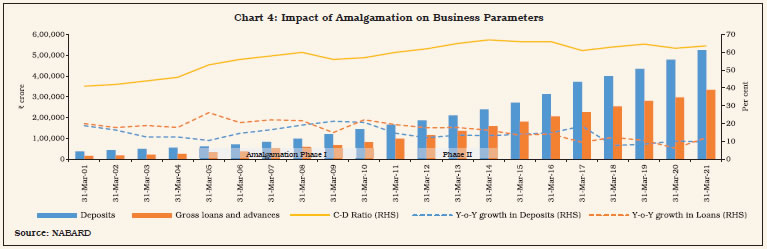

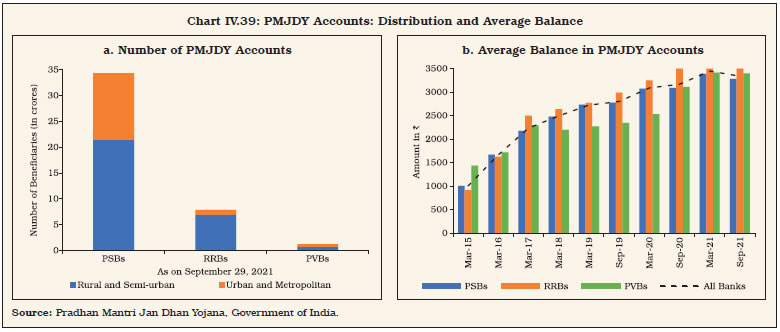

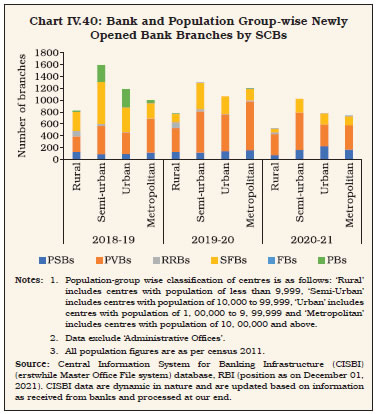

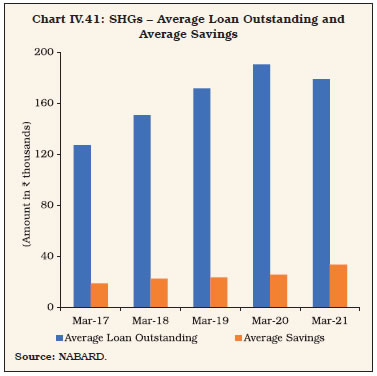

12.1 Financial Inclusion Plans IV.81 Financial Inclusion Plans (FIPs) were introduced by the Reserve Bank in 2010 with the objective of encouraging banks to adopt a planned and structured approach towards financial inclusion. FIP returns submitted by banks show that progress has been made in provisioning of banking services in the rural areas and with time, their usage have also increased. However, the growth of traditional brick and mortar banking branches has remained tepid, while banking services through BCs have gained greater prominence in the last few years. At end-March 2021, BC outlets constituted more than 95 per cent of the total banking outlets in villages, led by the rapid growth in the number of BCs in villages with population more than 2,000. On the usage front, Basic Savings Bank Deposit Accounts (BSBDA) and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) based transactions through BCs witnessed strong growth during 2020-21 (Table IV.25). 12.2 Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana IV.82 Since its inception in August 2014, PMJDY has been contributing towards financial inclusion of the unserved and underserved population of the country. Over the span of seven years, the number of total beneficiaries under PMJDY expanded to 44.12 crores, with deposits of ₹1.49 lakh crore deposits as on December 15, 202127. The majority of these accounts are maintained with PSBs and RRBs (97 per cent), with nearly two-thirds of the total accounts operational in rural and semi-urban areas (Chart IV.39a). The usage of these accounts, however, moderated as evident from the marginal decline in average balances for September 2021 across all bank groups (Chart IV.39b). There has been a steady increase in the number of RuPay debit cards issued, driven by both PSBs and RRBs.  12.3 New Bank Branches by SCBs IV.83 Opening of new bank branches moderated for the second consecutive year, with focus of banks shifting to leveraging the BC model and digitisation of banking operations, enabled by automation and data analytics. During 2020-21, new bank branches opened by SCBs declined by 29.2 per cent, on top of a contraction of 6.0 per cent in the previous year. The decline occurred across all population groups as well as bank groups, except for PSBs which increased their brick-and-mortar banking outreach by 15.8 per cent as compared to a year ago (Chart IV.40). IV.84 Although fewer branches were opened across all tier centres, more than half of the new branches were opened in Tier 1 and Tier 2 centres in 2020-21 (Table IV.26). 12.4 Microfinance Programme IV.85 Microfinance involves extension of small loans and other financial services to low-income individuals or groups who are otherwise deprived of access to formal financial services. Over the years, microfinance programmes have played a significant role in facilitating financial inclusion, particularly among the unbanked and underbanked segments of the population. The Self-Help Group – Bank Linkage Programme (SHG – BLP) promoted by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) has emerged as the world’s largest microfinance programme in terms of number of beneficiaries and micro-credit extended.  IV.86 At end-March 2021, while SHGs’ savings with banks increased by 43.3 per cent, their loans outstanding with banks declined by 4.4 per cent in relation to end-March 2020 levels. Loans disbursed during 2020-21 declined by 25.2 per cent in comparison to a growth of 33.2 per cent a year ago. Micro-credit disbursements to Joint Liability Groups (JLGs) and microfinance institutions also contracted by 30 per cent and 37 per cent, respectively, attributable to subdued economic activity on account of nation-wide lockdowns due to the pandemic (Appendix Table IV.13). IV.87 On an average, the amount of savings per SHG augmented by 30.8 per cent from ₹25,531 in 2019-20 to ₹33,392 in 2020-21, whereas the credit outstanding per SHG has decreased by 5.8 per cent from ₹1.90 lakh to ₹1.79 lakh during the same period (Chart IV.41). The NPA ratio of SHGs continued to improve, however, from 5.2 per cent in 2018-19 (4.9 per cent in 2019-20) to 4.7 per cent in 2020-2128. 12.5 Credit to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises IV.88 The number of MSME accounts decelerated for all SCBs during 2020-21, primarily driven by PVBs and FBs. The share of PSBs in total MSME credit outstanding has witnessed a secular decline since 2017-18, with corresponding increase in the share of PVBs.  The average amount of credit disbursed by PVBs, however, was much lower than that by PSBs (Table IV.27). 12.6 Trade Receivables Discounting System IV.89 The Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS) was launched by the Reserve Bank in 2017 to facilitate financial inclusion of MSMEs. It is an electronic platform for financing/discounting trade receivables of MSMEs due from large corporates, PSUs and government departments with banks/NBFCs through a competitive auction process. Over the last four years, there has been noteworthy growth in the financing of trade receivables of MSMEs through the TReDS platform. During 2020-21, the number of invoices uploaded and financed through the platform grew by more than 62 per cent, with the success rate29 improving to 91.3 per cent from 90.2 per cent in the previous year (Table IV.28). Going forward, with the central government permitting non-factor NBFCs and other entities to offer factoring services, credit supply to MSMEs through the platform is expected to increase further. Onboarding of more public sector enterprises on the TReDS can make a material difference in making the scheme more effective. 12.7 Regional Banking Penetration IV.90 Notwithstanding concerted efforts to improve banking penetration across geographies, banking outreach at the sub-national level remains tilted towards western, southern and northern regions in terms of shares in credit, deposits and number of branches (Chart IV.42a). Accordingly, the average population served per bank branch remains significantly higher in eastern, central and north-eastern regions relative to other parts of the country (Chart IV.42b).  IV.91 Combining the reach, familiarity and rural orientation of credit co-operatives and professionalism of commercial banks, regional rural banks (RRBs) attend to the basic banking and credit needs of small farmers, agricultural labourers, artisans and other rural poor. RRBs are jointly owned by the Government of India, the concerned State Government, and the sponsoring commercial bank. The ownership pattern espouses the spirit of co-operative federalism and aspires to achieve the goal of last mile financial inclusion. IV.92 The number of RRBs reduced from 45 to 43 during 2020-21, due to amalgamation of 3 RRBs in Uttar Pradesh as a part of the third phase of their consolidation programme. Amalgamation drives in RRBs have helped boost their profitability and improved their asset quality while strengthening their capital base (Box IV.5).

13.1 Balance Sheet Analysis IV.93 During 2020-21, ₹400 crores (of which Central Government’s share was ₹200 crore) was sanctioned towards recapitalisation of 7 RRBs which had CRAR less than 9 per cent. A few RRBs also received state governments’ share of recapitalisation sanctioned during the previous financial year. Catalysed by capital infusion and bolstered by growth in borrowings and deposits, the liabilities of RRBs grew robustly during 2020-21. Borrowings were mainly from NABARD, aided by the Special Liquidity Facility (SLF) and relaxations in eligibility criteria for availing refinance. IV.94 The availability of funds helped RRBs sustain their credit growth at rates higher than SCBs, as also their own 5-year average growth rate of 10.5 per cent. As a result, the C-D ratio of RRBs improved to 63.6 per cent at end-March 2021 from 62.2 per cent at end-March 2020. During 2020-21, the prevalence of excess liquidity also prompted RRBs to park more funds with the Reserve Bank (Table IV.29). IV.95 Priority sector lending with a focus on agriculture is the mainstay of RRBs’ operations. During 2020-21, agricultural lending constituted 70 per cent of total loans and advances of RRBs (Table IV.30). Even though their total asset size was only 3.3 per cent of that of SCBs, their loans to the sector were 16.8 per cent of the SCBs’ advances. With all except 3 RRBs lending more than 75 per cent of the previous year’s ANBC to the priority sector, they overachieved their target by 17 per cent in 2020-21 (Appendix Table IV.15). 13.2 Performance of RRBs IV.96 During 2020-21, RRBs, as a whole, turned around from losses in the preceding two years and reported net profit despite a moderation in their interest income as their interest expenses contracted (Table IV.31). Moreover, RRBs effectively utilised their high priority sector lending portfolio (particularly agriculture) to augment their income through sale of PSLCs. During 2020-21, the total volume of PSLCs traded by RRBs grew by 26 per cent and they accounted for 33 per cent of the total volume of PSLCs traded by all banks. IV.97 During 2020-21, even as 30 of the 43 RRBs posted net profit (Appendix Table IV.14), 17 RRBs carried accumulated losses of ₹8,264 crore as at end-March 2021, and 16 of them had CRARs less than the regulatory minimum of 9 per cent. IV.98 In the budget estimates for 2021-22, the Central Government allocated ₹1,200 crore for recapitalisation of RRBs, which is expected to further strengthen their capital buffers and help enhance their credit disbursement to the rural poor. IV.99 According to the Fraud Vulnerability Index (VINFRA) that measures adherence to fraud management guidelines, out of the 42 RRBs (for which data are available for 2020-21), 41 RRBs were categorised as Grade A, indicating least vulnerability. However, being a self-assessment tool, the gradation does not completely preclude the vulnerability of a bank against fraud. On the other hand, the Vulnerability Index for Cyber Security Framework (VICS), which is also a self-assessment tool, during 2020-21, indicated 21 out of the 43 RRBs were categorised as Grade A, while 6 RRBs fell under Grade C, reflecting the need for strengthening their cyber security framework (CSF). 14. Local Area Banks IV.100 Local Area Banks (LABs) were set up as private limited companies with the objective of enabling local institutions to mobilise rural savings and strengthen institutional credit mechanisms in local areas (up to three contiguous district towns). During 2020-21, the Reserve Bank cancelled the banking licence issued to Subhadra Local Area Bank Ltd., Kolhapur, Maharashtra and consequently, the number of LABs operational in the country reduced to two, accounting for a mere 0.006 per cent of the total assets of SCBs as at end-March 2021. IV.101 The consolidated balance sheet of LABs expanded during 2020-21. However, the credit–deposit ratio remained unchanged at around 81 per cent (Table IV.32). 14.1 Financial Performance of LABs IV.102 The profitability of LABs improved during 2020-21 as the contraction in operating expenses, especially the wage bill, outweighed that in non-interest income, which resulted in boosting profitability ratios (Table IV.33). 15. Small Finance Banks IV.103 Small finance banks (SFBs), set up in 2016, provide a savings vehicle for underserved sections of the population and also meet credit needs of small borrowers, through high technology low-cost operations. These banks are expected to deploy 75 per cent of their ANBC in priority sectors, with at least 50 per cent below ₹25 lakh. As of November 2021, twelve SFBs were operational in the country, including recently licenced Shivalik Small Finance Bank Ltd. and Unity Small Finance Bank Ltd. 15.1 Balance Sheet of SFBs IV.104 Since their inception, the consolidated balance sheet of SFBs has been growing at a pace higher than that of SCBs, mainly reflecting inorganic growth in their operations. During 2020-21, this was aided by higher deposits on the liabilities side. With SFBs offering lucrative interest rates on savings accounts, the share of CASA in their total deposits increased to 23.9 per cent in 2020-21, from 15.4 per cent in 2019-20. On the assets side, growth was supported by higher accretion to investments. Although loans and advances was the dominant constituent—with share of more than 66 per cent of total assets—their growth decelerated, reflecting the overall system wide anaemic credit growth (Table IV.34). 15.2 Priority Sector Lending of SFBs IV.105 The share of SFBs’ PSL in total lending declined for the fourth consecutive year during 2020-21, with the non-priority sector accounting for more than 28 per cent of total loans as at end-March 2021. Within the priority sector, micro, small and medium enterprises remained the main focus of SFBs’ lending, although their share declined (Table IV.35). 15.3 Financial Performance of SFBs IV.106 Despite the significant acceleration in operating profits during 2020-21, net profits of SFBs grew moderately on higher provisioning for bad and restructured loans. The GNPA ratio nearly tripled, reflecting the impact of COVID-19 on asset quality. There was improvement in capital positions (CRARs) on the back of high-quality Tier-1 capital (Table IV.36). 16. Payments Banks IV.107 Payments banks (PBs) were set up as differentiated banks that harness technology to further financial inclusion by providing low-cost banking solutions to small businesses, low-income households and other entities in the unorganised sector. By end-March 2021, six PBs were operational in the country. Unlike commercial banks, PBs are not permitted to undertake lending activities, with restrictions on deposit balances per customer. The Reserve Bank’s April 2021 move to enhance the limit of the maximum deposit balance per customer from ₹1 lakh to ₹2 lakh is expected to grant banks more flexibility in their operations. 16.1 Balance Sheet of PBs IV.108 In contrast to the flat growth in the SCBs’ balance sheet, that of PBs expanded by 48.9 per cent in 2020-21, on top of a growth of 17.5 per cent in 2019-20. The acceleration was led by deposits growth on the liabilities side and investments on the assets side (Table IV.37). The share of deposits in total liabilities increased to 36.8 per cent from 27.4 per cent a year ago and the recent enhancement in deposit balance limit is expected to further expand their deposit base. 16.2 Financial Performance of PBs IV.109 PBs are still in a nascent stage of development, incurring extensive investment costs for developing basic infrastructure. Moreover, their customer base is yet to develop fully, making break-even challenging. As a result, since inception, they have been suffering losses. The same trend held in 2020-21, despite improvement in their non-interest income (Table IV.38). IV.110 During 2020-21, efficiency of PBs measured in terms of cost-to-income ratio improved while their NIM declined. Their other performance metrics such as profit margin, RoA, and operating profit to working funds ratio remained negative, although the extent of losses reduced (Table IV.39). 16.3 Inward and Outward Remittances of PBs IV.111 Total inward and outward remittances through PBs declined by more than 20 per cent in 2020-21, in terms of both volume and value. Given the predominance of small-value large-volume transactions in their operations, UPI had the largest share in total remittance business for the third consecutive year, followed by IMPS and E-wallets (Table IV.40). IV.112 Notwithstanding a sharp downturn in global as well as domestic macroeconomic conditions, the banking sector in India remained resilient, with strong profitability indicators, and improved asset quality. Various regulatory measures initiated by the Reserve Bank in response to the pandemic played a crucial role in protecting banks’ balance sheets, providing necessary liquidity support and stabilising the financial sector. Additionally, the establishment of the National Asset Reconstruction Company Limited (NARCL) by the Government of India is expected to aid the recovery process, while alleviating stress on banks’ balance sheets. IV.113 Although credit offtake by banks remained subdued in an environment of risk aversion and muted demand conditions during 2020-21, a pick up has started in Q2:2021-22, with the economy emerging out of the shadows of the second wave of COVID-19. Going forward, revival in bank balance sheets hinges around overall economic growth which is contingent on progress on the pandemic front. However, banks would need to further bolster their capital positions to absorb potential slippages as well as to sustain the credit flow, especially when monetary and fiscal measures unwind. Although most of the regulatory relaxation measures have run their course, full extent of their impact on banking is yet to unravel. IV.114 Banks would need to strengthen their corporate governance practices and risk management strategies to build resilience in an increasingly dynamic and uncertain economic environment. With rapid technological advancements in the digital payments landscape and emergence of new entrants across the FinTech ecosystem, banks have to prioritise upgrading their IT infrastructure and improving customer services, together with strengthening their cybersecurity. 1 For charts presenting bank-group wise growth rates, the following adjustments have been made: i) Following the recategorization of IDBI Bank Ltd. w.e.f. January 21, 2019, it is excluded from PSB group and included in PVB group. The data on bank-group wise growth rate from March 2019 to December 2019 is based on the adjusted bank-group totals; ii) Following amalgamation of Lakshmi Vilas Bank with DBS Bank India, w.e.f. November 27, 2020, private and foreign bank-group wise growth rates are based on adjusted bank-group totals. 2 Proxied by lagged values of stressed assets ratio (SAR) (GNPAs plus restructured standard advances as percentage of gross advances). 3 Skewness in the distribution of banks overachieving their CRAR and CET-1 targets progressively declined from 0.65 and 1.01 in 2018-19, to 0.23 and 0.52 in 2019-20 and (-)1.48 and (-) 0.35 in 2020-21, respectively. 4 Recovery rate is the amount recovered as a percentage of the amount involved. 5 To ensure that asset sales by banks result in actual sale, threshold for banks holding SRs backed by their sold assets for additional provisioning was fixed at 50 per cent from April 1, 2017 and was subsequently reduced to 10 per cent from April 1, 2018. 6 As reported by ARCs for which data are available. 7 Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme was initiated by the Government of India in May 2020 to provide credit guarantee to MSMEs upto ₹3 lakh crore. The scope of the scheme was subsequently enlarged to include other sectors identified by the Kamath Committee. 8 As of March 31, 2021, regional rural banks and small finance banks are required to lend 75 per cent to priority sector. 9 Bank size = Advances + Deposits. 10 As per RBI norms, while computing priority sector target achievement, shortfall / excess lending for each quarter is monitored separately. A simple average of all quarters is arrived at and considered for computation of overall shortfall / excess at the end of the year. 11 Data for bank branches is taken from the Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy. 12 For SMFs, the sub-target will increase to 9 per cent by 2021-22, 9.5 per cent by 2022-23 and 10 per cent by 2023-24. Weaker sections target will increase to 11 per cent by 2021-22, 11.5 per cent by 2022-23 and 12 per cent by 2023-24. 13 Daily stock prices of 12 PSBs, 18 PVBs and NIFTY-50 index were sourced from Bloomberg. 14 High-frequency data and a tight window around the event ensures better accounting for anticipation effects and other confounding factors. 15 Bank-wise balance sheet data as at end December 2019 was taken from the RBI database. 16 Syndicate Bank merged with Canara Bank, Andhra Bank and Corporation Bank merged with Union Bank of India, United Bank of India and Oriental Bank of Commerce merged with Punjab National Bank and Allahabad Bank merged with Indian Bank. 17 In September 2020, the Parliament approved supplementary demand for grants of ₹20,000 crore for recapitalisation in PSBs, of which ₹5,500 crore was infused in Punjab and Sind Bank in November 2020. 18 In the Union Budget 2021-22, the government proposed to infuse ₹20,000 crore into PSBs. 19 The data presented here precedes the issuance of RBI Circular dated April 26, 2021 on Corporate Governance. 20 Average employee pay has been calculated as a ratio of total staff costs to total employee strength. 21 On November 4, 2019, the Reserve Bank revised its guidelines on compensation, aligning them to the Financial Stability Board norms. The new guidelines became effective from April 1, 2020. 22 In case the variable pay is up to 200 per cent of the fixed pay, a minimum of 50 per cent of the variable pay and in case the variable pay is above 200 per cent, a minimum of 67 per cent of the variable pay should be via non-cash instruments. 23 Westpac Banking Corporation was excluded from the Second Schedule to the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 vide notification DOR.IBD.No.99/23.13.138/2020-21 dated July 18, 2020. 24 These include Prepaid Payment Instrument (PPI) issuers, Card Networks and White Label Automated Teller Machine (ATM) operators. 25 Defined as deposit insurance fund as a per cent of insured deposits. 26 Available at https://data.imf.org/?sk=E5DCAB7E-A5CA-4892-A6EA-598B5463A34C 27 Available at https://pmjdy.gov.in/account 28 NABARD Annual Report 2020-21 29 Defined as per cent of invoices uploaded that get financed. 30 The amalgamation process was initiated based on the recommendations of the “Advisory Committee on Flow of Credit to Agriculture and Related Activities” (Dr.Vyas Committee, 2004) and the recommendations of the Internal Working Group on RRBs, headed by Shri A.V. Sardesai. 31 RRBs that do not have accumulated losses and have posted net profit in the current year. 32 The impact of the third phase of amalgamation on bank financials cannot be independently gauged since the pension scheme, implemented from April 2018, has also had a simultaneous impact. 33 The concept of CRAR was introduced for RRBs only in 2007, and consequently, data on CRAR is not available for the period prior to amalgamation. Therefore, leverage ratio and reserves to capital ratio are used for assessing the impact of amalgamation on the capital position of RRBs. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

পেজের শেষ আপডেট করা তারিখ: