IST,

IST,

Operations and Performance of Commercial Banks (Part1 of 3)

Operations and Performance of Commercial Banks 3.1 avourable macroeconomic conditions continued to underpin the business and financial performance of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs)1 during 2005-06. The operations of SCBs during the year were marked by a large expansion of bank credit for the second year in succession. However, the credit growth was broad-based even as credit expansion in respect of the retail sector, particularly housing, and loans to commercial real estate was more pronounced. On the liability side, deposits grew at a higher rate in comparison with the previous year. However, the expansion of deposits could not keep pace with the high credit growth compelling banks to liquidate some of their holdings of Government securities. Reversing the trend of the previous year, net profits of the SCBs, as a group, increased. To a large extent, this was facilitated by a sharp increase in net interest income due to a strong growth in credit volumes. The asset quality of SCBs improved further during 2005-06 as reflected in the decline in gross non-performing assets in absolute terms for a third year in succession. Banksí capital to risk-weighted assets ratio remained more or less at the previous yearís level, despite application of capital charge for market risk and sharp increase in risk-weighted assets. 3.2 his Chapter profiles the operations and financial performance of scheduled commercial banks at the aggregate and bank group levels. The Chapter is organised into eleven Sections. Section 2 analyses the balance sheets of SCBs on an aggregate basis, while Section 3 delineates their off-balance sheet operations. Financial performance of SCBs is analysed in Section 4. Section 5 profiles the performance of soundness indicators. Operations of SCBs in the capital market are detailed in Section 6. Technological developments in banking during the year are covered in Section 7. Regional spread of banking is set out in Section 8. Section 9 presents an update on customer service and financial inclusion. Apart from the SCBs, there exist 133 regional rural banks (RRBs)2 and four local area banks (LABs). While the performance of SCBs forms the core of this Chapter, the performance of RRBs and LABs are detailed separately in Section 10 and Section 11, respectively. 3.3 The aggregate balance sheet of SCBs expanded by 18.4 per cent during 2005-06 as compared with 19.3 per cent in 2004-05, including the impact of conversion of a non-banking entity into a banking entity (Table III.1). The number of SCBs declined to 84 at end-March 2006 from 88 at end-March 2005 due to merger of two domestic banks, and one foreign bank, and closure of another foreign bank (Box III.1). The ratio of assets of SCBs to GDP at factor cost at current prices, however, increased significantly to 86.9 per cent at end-March 2006 as compared with 82.8 per cent at end-March 2005, suggesting a faster growth of the banking system in relation to the real economy. The degree of leverage enjoyed by the banking system as reflected in the equity multiplier (measured as total assets divided by total equity), however, remained unchanged at the previous yearís level of 15.7 per cent. 3.4 The behaviour of major balance sheet indicators of SCBs during 2005-06 followed more or less the pattern of the previous year. Underpinned by robust economic growth in general and industrial growth in particular, loans and advances grew by 31.8 per cent during 2005-06 on top of the increase of 33.2 per cent in the previous year. The expansion in loans and advances was funded largely by deposit growth (17.8 per cent in 2005-06 compared with 16.6 per cent in the previous year), significant increase in retained earnings, increased recourse to borrowings and offloading of Government and other approved securities (Table III.2). The growth in credit during 2005-06 outpaced deposits both in percentage and in absolute terms. The year 2005-06 was the second consecutive year, when increase in credit in

absolute terms was more than the absolute increase in aggregate deposits. The growth in investments, which had somewhat moderated during 2004-05, turned negative during 2005-06 in view of unwinding of Government securities by public sector banks (PSBs) and old private sector banks to meet the high credit demand [Appendix Table III.1(A) to (C)]. Box III.1: Amalgamations in the Commercial Banking Sector During 2005-06, two domestic banks and one foreign bank were amalgamated, and one foreign bank was closed reducing the number of scheduled commercial banks from 88 at end-March 2005 to 84 at end-March 2006. On the recommendations of the Reserve Bank, the Central Government placed the Ganesh Bank of Kurundwad Ltd. under a moratorium for a period of 3 months effective January 7, 2006 under Section 45 of the Banking Regulation (B. R.) Act, 1949 because the net worth of the bank had turned negative, and it failed to augment its capital for several years. The scheme of amalgamation of the bank with the Federal Bank Ltd. prepared by the Reserve Bank was sanctioned by the Government on January 24, 2006. However, the proposed amalgamation was challenged by Ganesh Bank of Kurundwad Ltd. and others before the High Court of Bombay. Following the Supreme Court order dated August 28, 2006, dismissing the Petition filed by the bank, the Central Government issued necessary notification on September 1, 2006 to effect the merger from September 2, 2006. The voluntary amalgamation of the Bank of Punjab Ltd. with the Centurion Bank Ltd. was approved by the Reserve Bank in terms of Section 44A of the B. R. Act, and became effective from October 1, 2005. The Centurion Bank subsequently changed its name to Centurion Bank of Punjab Ltd. Among foreign banks, while ING Bank NV closed its business in India, UFJ Bank Ltd. merged its banking business globally with Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi Ltd. As a result, ING Bank NV and UFJ Bank Ltd. were excluded from the Second Schedule to the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 with effect from October 28, 2005 and January 1, 2006, respectively (details are provided in Section III.8).

3.5 Bank group-wise, new private sector banks grew at the highest rate during 2005-06 (43.2 per cent), followed by foreign banks (31.2 per cent), public sector banks (13.6 per cent) and old private sector banks (12.2 per cent) (Table III.2). As a result, the relative significance of PSBs declined significantly with their share in total assets of SCBs declining to 72.3 per cent at end-March 2006 from 75.3 per cent at end-March 2005, while that of new private sector banks increasing to 15.1 per cent from 12.5 per cent. This mainly reflected the trend in deposits on the liabilities side (Table III.3).

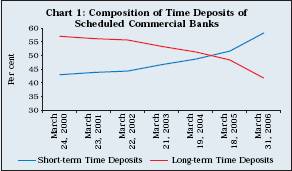

3.6 Deposits of SCBs increased at a higher rate of 17.8 per cent during 2005-06 compared with 16.6 per cent in the previous year. Demand deposits and savings deposits grew at a significantly higher rate during 2005-06 as compared with the previous year. The growth rate of time deposits, which had moved up somewhat during 2004-05, slipped slightly during 2005-06, reflecting mainly the impact of growing competition from other savings instruments, especially life insurance policies and units of mutual funds. The efforts made by SCBs to raise deposits to fund the increased credit demand led to a significant shortening of the maturity profile of deposits in the banking system (Box III.2). Box III.2: Changing Composition of Deposits of Scheduled Commercial Banks Deposits of scheduled commercial banks are categorised into demand and time deposits. Demand deposits consist of: (i) current deposits; (ii) demand liability portion of savings bank deposits; (iii) margins held against letters of credit/guarantees; (iv) balances in overdue fixed deposits, cash certificates and cumulative/recurring deposits; (v) outstanding telegraphic transfers, mail transfers and demand drafts; (vi) unclaimed deposits; (vii) credit balances in the cash credit accounts; (viii) demand portion of Participation Certificates (PCs); and (ix) deposits held as security for advances which are payable on demand. Obviously there is no maturity period for demand deposits. On the other hand, time deposits comprise: (i) fixed deposits; (ii) cash certificates; (iii) cumulative and recurring deposits; (iv) time liability portion of savings bank deposits; (v) staff security deposits; (vi) margins held against letters of credit, if not payable on demand; (vii) fixed deposits held as securities for advances; and (viii) time portion of PCs. Time deposits could be further categorised into short-term (time liability portion of savings deposits and term deposits with contractual maturity of up to one year) and long-term deposits (term deposits with contractual maturity above one year).

The share of short-term deposits in time deposits as on the last reporting Friday of June 2006, was the highest for foreign banks (83.3 per cent), followed by new private sector banks (80.6 per cent), public sector banks (54.3 per cent) and old private sector banks (51.6 per cent) (Chart 2).

The increased preference for short-term deposits could be attributed to low returns on long-term deposits. This is evident from the spread between short-term and long-term deposits, which narrowed down to 75 basis points at end-March 2006 from 100 basis points at end-March 2005 before widening a little by June 2006. In view of low spread, investors prefer short-term deposits, despite low returns, while waiting for investment opportunities with higher returns. Banks on the other hand, prefer short-term deposits. With low short-term interest rates, banks are able to mobilise resources at lower cost. This enables banks in a competitive environment to lend at lower cost to well-rated business firms to contain defaults on their loans. In the Indian context, it is observed that foreign and private sector banks have relatively high share of low cost deposits. Incidentally, these bank groups also have high profit margin and low NPA levels. Reserve Bank of India (1998), Report of the Working Group on Money Supply: Analytics and Methodology of Compilation (Chairman: Y.V. Reddy). Non-Deposit Resources 3.10 In order to meet high credit demand and strengthen the capital base, eleven banks accessed the equity market to raise Rs.11,067 crore. Banks also raised Rs.30,151 crore from 97 issues in the private placement market as compared with Rs.15,219 crore through 87 issues in the previous year (refer section 6 for details).

International Liabilities of Banks 3.11 The international liabilities of banks increased sharply by 20.2 per cent during 2005-06 as against 15.5 per cent in 2004-05 mainly due to a sharp increase in foreign currency borrowings, FCNR(B) deposits, NRE rupee deposits, equities of banks held by non-residents and issuance of ADRs/ GDRs (Table III.4). Continuing the trend of last few years, the relative significance of foreign currency deposits declined further during 2005-06, while that of foreign currency borrowings increased (Chart III.2). As redemption of IMDs in December 2005 outweighed a sharp increase in holding of equities of banks by non-residents which boosted the share of ëother liabilitiesí, there was a decline in the share of ëown issues of securities/bondsí during 2005-06. 3.12 In recent years, external (international) sources of funds in banks' operations has been increasing, suggesting growing integration of the Indian banking sector with the international capital markets. This was reflected in the increase in the share of international liabilities of SCBs in total liabilities (Chart III.3).

Bank Credit 3.13 Loans and advances of SCBs registered a robust growth of 31.8 per cent during 2005-06 on top of the high growth of 33.2 per cent in 2004-05 (Box III.3). Among the major components of bank credit, while bills purchased and discounted grew at a lower rate in 2005-06 as compared with the previous year, cash credit and overdrafts registered a robust growth. Term loans, which constitute the largest component of advances, grew sharply by 35.7 per cent during the year, the trend which was observed in previous years as well. As a result, the share of term loans in both total advances and gross domestic capital formation (GDCF) has increased significantly in recent years (Chart III.4). Sectoral Deployment of Gross Bank Credit 3.14 Non-food bank credit increased sharply during 2005-06. The credit growth was broad based. Credit to services (including personal loans and other services) increased by 52.8 per cent in 2005-06, accounting for 58.3 per cent of incremental non-food gross bank credit (NFGBC). Personal loans increased sharply in 2005-06 mainly on account of housing loans. Real estate loans more than doubled during the year (Table III.5; Appendix Table III.3). Other personal loans such as credit card outstanding and education loans also recorded sharp increases of 59.3 per cent and 96.5 per cent, respectively.

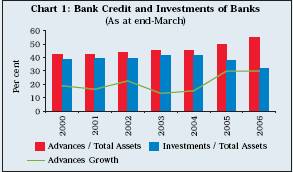

Box III.3: Analysis of Credit Growth The bank lending has expanded in a number of emerging market economies, especially in Asia and Latin America, in recent years. Bank credit to the private sector, in real terms, was rising at a rate between 10 and 40 per cent in a number of countries by 2005 (BIS, 2006). Several factors have contributed to the significant rise in bank lending in emerging economies such as strong growth, excess liquidity in banking systems reflecting easier global and domestic monetary conditions, and substantial bank restructuring. The recent surge in bank lending has been associated with important changes on the asset side of banksí balance sheet. First, credit to the business sector - historically the most important component of banksí assets - has been weak, while the share of the household sector has increased sharply in several countries. Second, banksí investments in Government securities increased sharply until 2004-05. As a result, commercial banks continue to hold a very large part of their domestic assets in the form of Government securities - a process that seems to have begun in the mid-1990s. There has been a sharp pick up in bank credit in India in recent years. The rate of growth in bank credit which touched a low of 14.4 per cent in 2002-03, accelerated to more than 30.0 per cent in 2004-05, the rate which was maintained in 2005-06 (Chart 1). The upturn in the growth rate of bank credit can be attributed to several factors. One, macroeconomic performance of the economy turned robust with GDP growth rates hovering between 7.5 per cent and 8.5 per cent during the last three years. Two, the hardening of sovereign yields from the second half of 2003-04 forced banks to readjust their assets portfolio by shifting from investments to advances. While the share of gross advances in total assets of commercial banks grew from 45.0 per cent to 54.7 per cent, that of investments declined from 41.6 per cent to 32.1 per cent in the last two years. However, the credit growth has been broad-based making banks less vulnerable to credit concentration risk. The declining trend of priority sector loans in 2001-02 in the credit book of banks was due to prudential write offs and compromise settlements of a large number of small accounts which was reversed from 2002-03 on the strength of a spurt in the housing loan portfolio of banks (Chart 2). Even though credit to industry and other sectors has also picked up, their share in total loans has declined marginally. Retail loans, which witnessed a growth of over 40.0 per cent in 2004-05 and again in 2005-06, have been the prime driver of the credit growth in recent years. Retail loans as a percentage of gross advances increased from 22.0 per cent in March 2004 to 25.5 per cent in March 2006 (Chart 3). Of the components of retail credit, the growth in housing loans was 50.0 per cent in 2004-05 and 34.0 per cent in 2005-06. Banksí direct exposure to commercial real estate also more than doubled in the last financial year. The cyclical uptrend in the economy along with the concomitant recovery in the business climate brings with it improved abilities of the debtors to service loans, thereby greatly improving banksí

asset quality. Despite the sharp rise in credit growth in recent years, not only the proportional levels of gross non-performing loans (NPLs) have declined, but the absolute levels of gross NPLs declined significantly. Several factors have contributed to the marked improvement in the Indian banksí asset quality. One, banks have gradually improved their risk management practices and introduced more vigorous systems and scoring models for identifying credit risks. Two, a favourable macroeconomic environment in recent years has also meant that many entities and units of traditionally problematic industries are now performing better. Three, diversification of credit base with increased focus on retail loans, which generally have low delinquency rates, has also contributed to the more favourable credit risk profile. Four, several institutional measures have been put in place to recover the NPAs. These include Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs), Lok Adalats (peopleís courts), Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) and corporate debt restructuring mechanism (CDRM). In particular, the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002 for enforcement of security interest without intervention of the courts has provided more negotiating power to the banks for resolving bad debts. References: Bank for International Settlement (2006), ëThe Banking System in Emerging Economies: How much progress has been made?í BIS Papers No 28, August. 3.15 Based on the provisional data available, bank credit to the retail sector increased by 47.2 per cent at end-June 2006 (year-on-year) with housing loans increasing by 54.3 per cent. Credit to real estate recorded an annualised growth of 102.4 per cent. Growth in credit to agriculture and industry was 36.8 per cent and 26.6 per cent, respectively. 3.16 Credit to the priority sector increased by 33.7 per cent in 2005-06 as against 40.3 per cent in the previous year. The agriculture and housing sectors were the major beneficiaries, which together accounted for more than two-third of incremental priority sector lending in 2005-06. Credit to small scale industries also accelerated (Table III.6). Several favourable policy initiatives undertaken by the Central Government and the Reserve Bank including, inter alia, the policy package for stepping up of credit to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) announced on August 10, 2005, have had a positive impact.

3.17 The outstanding advances of PSBs to priority sector increased by 33.7 per cent during 2005-06. The PSBs, as a group, achieved the priority sector target of 40.0 per cent of net bank credit (NBC) as on the last reporting Friday of March 2006. However, the sub-targets of 18.0 per cent and 10.0 per cent of NBC for credit to agriculture sector and the weaker sections, respectively, were not met (Table III.7 and Appendix Table III.4 and III.5). At the individual bank-level, all the nationalised banks, and all but

two of the State Bank group (State Bank of India and State Bank of Patiala) were able to meet the priority sector target of 40 per cent of NBC. However, only ten PSBs (Allahabad Bank, Andhra Bank, Bank of India, Indian Bank, Indian Overseas Bank, Punjab National Bank, Syndicate Bank, State Bank of Bikaner and Jaipur, State Bank of Indore and State Bank of Saurashtra) were able to achieve the sub-targets for agriculture, while the sub-target for weaker sections was met by eight PSBs (Allahabad Bank, Andhra Bank, Bank of India, Indian Bank, Indian Overseas Bank, Punjab National Bank, Syndicate Bank and State Bank of Patiala). Special Agricultural Credit Plans 3.20 The Reserve Bank had advised public sector banks to prepare Special Agricultural Credit Plans (SACP) on an annual basis in 1994. The SACP mechanism for private sector banks was made applicable from 2005-06, as recommended by the Advisory Committee on Flow of Credit to Agriculture and Related Activities from the Banking System (Chairman: Prof. V.S. Vyas) and announced in the Mid-term Review of Annual Policy for 2004-05. Public sector banks were advised to make efforts to increase their disbursements to small and marginal farmers to 40.0 per cent of their direct advances under SACP by March 2007. The disbursement to agriculture under SACP by public sector banks aggregated Rs.94,278 crore during 2005-06, which was much above the target of Rs.85,024 crore and the disbursement of Rs.65,218 crore during 2004-05. The disbursement by private sector banks during 2005-06 at Rs.31,119 crore was above the target of Rs.24,222 crore.

Micro-finance Credit to Industry

Retail Credit

Lending to the Sensitive Sectors 3.25 Lending by SCBs to the sensitive sectors (capital market, real estate and commodities) increased sharply during 2005-06 mainly on account of a sharp increase in exposure to the real estate market (Table III.10). Total exposure of SCBs to the sensitive sectors consituted 18.9 per cent of aggregate bank loans and advances (comprising 17.2 per cent to real estate, 1.5 per cent to the capital market and 0.3 per cent to the commodities sector). Investments 3.27 Investments by banks comprise two broad categories, viz., SLR investments (comprising Government and other approved securities which are eligible for being reckoned for maintaining the statutory liquidity ratio) and non-SLR investments (comprising commercial paper, shares, bonds and debentures issued by the corporate sector). Almost four-fifths of the investments of banks are in the SLR securities. During 2005-06, overall investments of SCBs declined marginally by 0.3 per cent, as against the increase of 8.1 per cent in the previous year, mainly due to decline in SLR investments. 3.28 Banks are required to maintain statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) of 25 per cent of the net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) in Government and other approved securities from October 1997. However, SCBs have been investing in Government and other approved securities much in excess of the statutory stipulation since the mid-1990s. Such investments reached an all-time high of 42.7 per cent of NDTL on April 16, 2004. However, in the wake of increased credit demand, banks have been gradually readjusting their SLR portfolio in the last two years (Box III.5). For the first time since the nationalisation of banks in 1969, investment by SCBs in SLR securities in absolute terms declined by Rs.21,699 crore during 2005-06 in contrast to an increase of Rs.61,566 crore in 2004-05 (Chart III.6). 3.29 Banksí investments in non-SLR securities also declined by 9.4 per cent (Rs.13,824 crore) as compared with an increase of 4.1 per cent

Box III.4: Changing Investment Portfolio of Banks Banks are required to invest a prescribed minimum of their net demand and time liabilities in Government and other approved securities, as per the BR Act, 1949. As a part of the financial sector reforms, the SLR requirement for the banks was gradually reduced to 25 per cent by October 1997 from its peak of 38.5 per cent in February 1992. However, even after major reduction in SLR stipulations, banks maintained an average SLR investments of 37.3 per cent of the net demand and time liabilities during the period 1998-99 to 2002-03. The reduced demand for credit on account of slowdown of industrial sector, which was undergoing a phase of restructuring, forced banks to park their funds in Government securities. In the declining interest rate scenario, such investments became particularly attractive for banks due to their high yield. Incidentally, the period of low demand for credit coincided with the period when banks were making efforts to raise their capital levels and reduce the levels of NPAs. The application of capital adequacy norms, which required banks to maintain 8 per cent of their risk-weighted assets as capital from March 31, 1996, and the pressure to bring down their NPA levels made banks somewhat risk averse. As such investments in Government and other approved securities, which attracted zero-risk weights, became the preferred form of investments by banks. The period 1998-99 to 2002-03 was followed by a period of high economic growth and a sharp pick-up in credit. From 2003-04 onwards, however, banks faced increased competition from other saving instruments and the growth of aggregate deposits slowed down to 15.4 per cent in 2004-05 from 16.4 per cent in 2003-04 caused primarily by term deposits. During this period, sovereign yield hardened significantly. The combination of these factors led to a significant adjustment in the investment portfolio of banks. Banks endeavoured to meet the increased credit demand by restricting fresh investments in Government securities (2004-05) and then liquidating Government securities (2005-06). A more or less similar trend was observed in respect of non-SLR investments. Increased access to the capital market and recourse to non-deposit resources eased the pressure for the banks only to an extent (Chart 1).

References: RBI Bulletin (2005), Performance of the Private Corporate Sector in the post Liberalisation Period, November. Ramasastri, A. S and N. K. Unnikrishnan (2006),ëIs the Role of Banks as Financial Intermediaries Decreasing? A Helicopter Tourí, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XLI, No.11, March. (Rs.5,700 crore) in the previous year (Table III.12). While investments in bonds/debentures declined sharply, those in shares and commercial paper increased. The total flow of funds from SCBs to

the commercial sector, including non-SLR investments, increased by 28.3 per cent (Rs.3,40,573 crore) compared with 29.0 per cent (Rs.2,59,259 crore) in the last year. International Assets of the Banking System

share of short-term claims (with residual maturity less than one year) in the consolidated international claims declined during 2005-06, while that of long-term claims increased more or less correspondingly.

3.34 The consolidated international claims of banks based on immediate country risk, underwent some change during the year. While the share of claims of banks on the US and Hong Kong declined significantly, those on the U.K. increased. As at end-March 2006 the US, the UK, Hong Kong, Germany and Singapore together accounted for 57.0 per cent of total consolidated international claims (Table III.16). Quarterly Trends - Commercial Banking Survey4 3.35 As the reporting Fridays for end-September and end-March during 2005-06 fell on September 30, 2005 and March 31, 2006 (coinciding with half-yearly and annual closing, respectively), the second and fourth quarters witnessed sharp increases in deposits and credit aggregates vis-a-vis the other quarters as well as the corresponding quarters of the previous year. 3.36 During Q1 of 2005-06, credit expansion was more than fresh accretion to deposits due mainly to a sharp decline in demand deposits. To meet the gap, banks liquidated their SLR and non-SLR investments. Banks also liquidated foreign currency assets. A sharp increase in capital account also enabled banks to meet the increased credit demand.

3.37 In Q2, net accretion to deposits was quite large as also the expansion of credit to the commercial sector. However, net accretion to aggregate deposits exceeded the credit to the commercial sector. Banks, therefore, increased their investment in government securities. 3.38 In Q3, accretion to aggregate deposits and credit offtake declined sharply. However, credit to commercial sector was almost four times the fresh accretion in aggregate deposits. Banks investments in foreign currency assets also increased sharply. To meet the funding gap, banks liquidated investments both in Government securities and non-SLR investments.

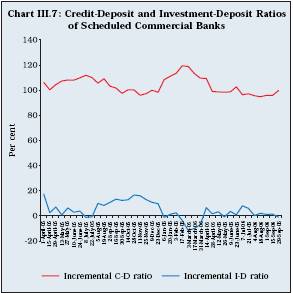

Credit-Deposit Ratio 3.40 The high rate of bank credit growth during last two years had resulted in a unique behaviour of credit-deposit (C-D) ratio and investment-deposit (I-D) ratio. The incremental C-D ratio, which was lower than the incremental I-D ratio up to August 6, 2004, rose sharply thereafter, while the incremental I-D ratio declined. This trend was accentuated in 2005-06 as throughout the year the C-D ratio remained significantly higher than the I-D ratio. 3.41 Owing to large credit offtake, the incremental C-D ratio remained generally above hundred per cent throughout the year. On account of unwinding of investment in SLR securities, the incremental I-D ratio varied in the range of 22.3 per cent to (-) 11.6 per cent. The incremental credit-deposit and investment-deposit ratios generally depicted a negative relationship. When the incremental C-D ratio fell from its peak of 111.8 per cent in July 2005 through to 96.0 per cent in mid-November 2005, the incremental I-D ratio turned negative in July 2005, and then moved upwards to 16.0 per cent by mid-November 2005. The incremental I-D ratio again turned negative during the fortnight ended January 6, 2006. The ratio recovered to the positive region till February 3, 2006 only to turn negative again. Thus, in times of high credit demand, banks may not prefer to invest in Government securities (Chart III.7). 3.42 The C-D and I-D ratios, based on the outstanding amount, which moved more or less

in the same direction between 1999 and the third quarter of 2004-05, tended to move in opposite directions thereafter. As at end-March, the C-D ratio stood at an all-time high level of 70.1 per cent, while the I-D ratio dropped to a low of 40.1 per cent (Chart III.8).

1 SCBs comprise 28 public sector banks (State Bank of India and its seven associates, 19 nationalised banks and the Industrial Development Bank of India Ltd.), 8 new private sector banks, 19 old private sector banks and 29 foreign banks. Ganesh Bank of Kurundwad Limited, which was placed under moratorium on July 7, 2006 and later merged with Federal Bank Limited on September 2, 2006, did not bring out its annual accounts for the year 2005-06. 3 Percentages presented are based on the last reporting Friday of the respective month and year, as reported under Section 42 (2) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. 4 Based on information received under Section 42 (2) Returns of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

পেজের শেষ আপডেট করা তারিখ: