IST,

IST,

Prompt Corrective Action: An Essential Element of Financial Stability Framework

Dr. Viral V. Acharya, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India

delivered-on অক্টোবর 12, 2018

|

Abstract This talk explains why the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is an essential element of its financial stability framework. It lays out the case for structured early intervention and resolution by regulators for banks that become under-capitalised due to poor asset quality or vulnerable due to loss of profitability. Detailing the mandatory and discretionary actions under the RBI's Revised PCA framework, it compares and contrasts these with the PCA framework operating in the United States. Finally, it documents empirically how Indian banks under the PCA framework are being restored back to health through better capitalisation, preservation of capital, and provisioning for losses. I would like to thank the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay, and in particular, Professor Pushpa Trivedi, who inspired me to pursue Economics and Finance, for inviting me back to IIT, my undergraduate alma mater. It is always an occasion of great pride and immense satisfaction for me to return to the Powai campus and be reminded of what I learnt here – the importance of identifying big problems to solve, approaching them with an analytical mindset, scything through seemingly attractive but incomplete fixes, and in the process, discovering durable solutions that address the root causes underlying the problems. About thirteen months back on the 7th of September, 2017, I spoke at the 8th R K Talwar Memorial Lecture about “The Unfinished Agenda: Restoring Public Sector Bank Health in India,” wherein, I touched upon three themes:

Since then, the GoI has announced a recapitalisation package for PSBs in October 2017 of INR 2.11 trillion, comprising INR 1.53 trillion of government capital infusion and balance to be raised from market funding, by March 2019. Equally importantly, the Reserve Bank of India issued a circular on the 12th of February, 2018 for the resolution of stressed assets, which employs the IBC reference as its lynchpin for resolution and is aimed at improving the credit culture in both borrowers and lenders. Another significant step has been taken by the Reserve Bank of India in parallel which has been somewhat under-appreciated, viz., the imposition of Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) on a number of banks whose capital, asset quality and/or profitability do not meet pre-specified thresholds. Today, I wish to explain why PCA is an essential element of the Reserve Bank’s (and more generally, of a banking supervisor’s) financial stability framework. Loss-absorption Role of Bank Capital Before I discuss the Prompt Corrective Action approach, it would be useful to briefly talk about the critical role of bank capital in relation to the process of resolution of stressed banks. In its simplest form, a bank balance-sheet has assets on the left hand side of the balance-sheet, and liabilities on the right hand side in the form of equity capital and deposits (and other forms of debt liabilities such as unsecured bonds, and wholesale finance such as inter-bank liabilities or short-term commercial paper). Equity capital is the primary loss-absorption buffer – means of protection – against the asset losses of a bank. It is meant to be at levels high enough to absorb unanticipated losses with enough margin so as to inspire confidence and enable the bank to continue as a going concern, in particular, without passing on losses to bank creditors. Once the capital level is fully consumed by the deteriorating financials, it exposes the unsecured creditors, including depositors, to bear the losses. While the deposits typically are insured up to a certain level, economic history shows that more often than not the ultimate costs of paying off all deposits fall on the sovereign, especially in the case of large, complex and inter-connected banks. Capital constraints at a wider, systemic level also impact the resolution of weak banks. The United States experience, empirically documented by Granja, Matvos and Seru (2017), shows that an optimal bidding strategy of a healthier bank – a potential acquirer, which may value the weaker bank for its franchise value from deposits, gets adversely impacted if it is itself poorly capitalized. In such a scenario, the overall value realization for the weak bank goes down. The poor capitalization of potential acquirers can also drive a wedge between their willingness and ability to pay for a failed bank. In this manner, bank capital being at healthy levels also has a system-wide loss-absorption role by helping sell weak banks to healthy ones in an efficient manner. Given this criticality of bank capital in absorbing losses, it is natural why minimum bank capital requirements are in place globally and why capital becomes one of the most important factors for supervisors to monitor. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, there has been a complete overhaul of the international regime for minimum regulatory capital requirements of banks, as enshrined in the revised Basel norms, viz., Basel-III. The goal of Basel III is to raise the quality, consistency and transparency of the capital base of banks to withstand unanticipated losses and to strengthen the overall risk coverage of the capital framework. In addition to revising the minimum capital ratio requirements for credit risk, Basel III also introduced a capital conservation buffer (CCB) and a countercyclical capital buffer. CCB is designed to ensure that banks build up a capital buffer outside periods of financial stress that can be drawn down when banks face financial (systemic or idiosyncratic) stress. Banks which draw down their capital conservation buffer during a stressed period are required to have a definite plan to replenish the buffer and face capital distribution constraints. The objective of the countercyclical capital buffer is to use capital as a macro-prudential instrument aimed at protecting the banking sector from periods of excess aggregate credit growth, that have often been associated with the build-up of system-wide risk. In this regard, it is instructive to note that the minimum bank capital ratio (to suitably risk-weighted assets) required to be held under the Basel norms is only a floor. Since the global financial crisis, many countries require their banks to hold capital at higher levels, as shown below. Further, in other major jurisdictions like the US and the UK, effective capital requirements tend to be even higher on account of several add-ons; for instance, in the US, higher leverage ratio (put simply, bank capital to unweighted assets ratio) and the stress tests – annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis & Review (CCAR) – also push up the effective capital requirements beyond Basel requirements for systemically important and/or large banks. While this view of bank capital focuses on its benefits in the form of loss-absorption adequacy at individual bank and systemic level, there is an equally important incentive role played by bank capital that is worthy of discussion.

Incentive Role of Bank Capital Let me now explain why it becomes imperative for bank supervisors to intervene in a weak bank much before the capital is completely eroded. Conceptually, there are at least two reasons why the world over banks that make losses to the point of being under-capitalised do not recapitalise, or are not recapitalised, promptly. First, while private banks typically hold greater capital than required by regulatory requirements, shareholders are reluctant to inject capital once the capital is eroded by losses as it gets primarily deployed in stabilising bank liabilities. To compensate for this wealth transfer for injecting capital, shareholders require a much higher rate of return than when banks are better capitalised, but such high required returns may render banking activity unprofitable to pursue. This is the well-known “debt overhang” problem, studied extensively in financial economics (Myers, 1977). Secondly, when banks become under-capitalised en masse or are government-owned to start with, it is often thought that recapitalisation should occur swiftly given the attendant real and systemic risk costs of not recapitalising banks – costs that a government should internalise. In practice, however, banking sectors are sometimes “too big to save” relative to the size of government balance-sheets. Even when that is not so, governments may themselves be financially constrained: bank recapitalisations must earn effective returns that exceed the costs of raising additional finance (usually additional borrowings) or from cutting back on other fiscal expenditures. Hence, it is quite common, even for government-owned under-capitalised banks to take a while to get adequately recapitalised, if at all. Regardless of the reason for the under-capitalisation of banks to persist, what is observed is that creditors of under-capitalised banks are not only offered off-balance sheet government guarantees, notably deposit insurance, but also implicit guarantees to uninsured creditors. This is done in the interest of financial stability and safeguarding of payment and settlement systems, but carries the downside that under-capitalised banks often continue to access credit markets at artificially low costs of borrowing. Consequently, without appropriate supervisory constraints in place, such banks are in a position to delay the recognition of losses and engage in ever-greening or zombie lending, which is essentially the rolling over of debts of unviable borrowers that would have otherwise defaulted. In fact, this was precisely what happened in Japan at the turn of the last century when the problem of non-performing loans and bank capital shortage persisted for over a decade. Hoshi and Kashyap (2010) attribute this to two factors: first, banks not recognising the true losses on NPAs, thereby overstating the quality of their loans; and, second, prevalence of zombie lending by under-capitalised banks. It was only after the implementation of the of Financial Revival Program (Takenaka Plan) starting in 2003, involving more rigorous evaluation of bank assets, increasing of bank capital, and strengthening of governance for recapitalised banks, that the Japanese banks finally stopped the process of ever-greening non-performing loans and started to accumulate capital through retained earnings over the next five years. In addition to the above evidence on Japan which I covered in some detail in the 8th R K Talwar Memorial Lecture, my recent joint work with Sascha Steffen and Lea Steinruecke, titled “Kicking the Can Down the Road: Government Interventions in the European Banking Sector,” examined all government interventions in the Eurozone banking sector during the 2007 to 2009 financial crisis. In particular, we analysed the implications of these interventions in the European banking sector for the subsequent sovereign debt crisis and found that:

The Case for Regulatory Prompt Corrective Action How should under-capitalised banks, and more generally, banks whose asset quality and profitability make them vulnerable to further stress, be dealt with, taking cognizance of the reality that the strength of market discipline by bank creditors is blunted by the presence of explicit and implicit government guarantees? This question received significant academic and policy-maker attention in the United States following the Savings & Loans (S&L) crisis, in which by mid-1980’s, so many thrifts had to be resolved at such low levels of capitalisation that in the end a significant government bailout in the form of blanket deposit insurance had to be engineered. Effectively, it had been left until too late to exercise regulatory discipline that could have substituted for the lack of adequate market discipline; as a result, the authorities had to engage in excessive forbearance and full-scale bailout. Key insight that emerged from the debate around the S&L crisis was that the banking regulator needed to adopt a “structured early intervention and resolution” (SEIR) approach (see, for instance, Benston and Kaufman, 1990, and White, 1991). This insight, in turn, led to the passage of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Improvement Act (FDICIA), 1991, and thus was born the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework of the FDIC as modern banking has witnessed. [Another twin born then was risk-based deposit insurance premium!] Prompt Corrective Action frameworks adopt the core principles of structured early intervention and resolution in the following manner:

Put simply, this is what Prompt Corrective Action (or PCA) is intended to achieve – to intervene early and take corrective measures in a timely manner, so as to restore the financial health of banks that are at risk by limiting deterioration in their health and preserving their capital levels. By construction then, PCA involves some restrictions on bank scope and expansion as not doing so would lead to excessive risks on the balance-sheets of these banks. Similarly, putting up PCA banks for sale in the market and / or replacing bank management become potential mechanisms for prompt resolution. It follows as a corollary that the strength of the PCA framework depends crucially on the extent of regulatory powers that can be exercised by the banking regulator. While the intent of PCA is primarily remedial, it can also act as a deterrence and incentivise bank management and shareholders to contain risks so they do not end up in PCA in the first place. And, by the virtue of being reasonably rule-based, PCA reduces the scope for discretion; like Odysseus, bank regulators tie themselves to the mast to evade the voices of the forbearance sirens. Reserve Bank’s Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) Framework The Reserve Bank’s PCA framework was introduced in December 2002 as a structured early intervention mechanism along the lines of the FDIC’s PCA framework. Subsequently, the framework was reviewed by the Reserve Bank keeping in view the international best practices and recommendations of the Working Group of the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC) on Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions in India (January 2014) and the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission (FSLRC, March 2013). The Revised PCA Framework was issued by the Reserve Bank on April 13, 2017 and implemented with respect to the bank financials as on March 31, 2017. Annex Ia provides the thresholds deployed under the revised framework, publicly available at /en/web/rbi, linked to capital (CRAR – regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets ratio – and Leverage ratio), asset quality (NNPA – net non-performing assets to advances ratio), and profitability (ROA – return on assets). Under each measure, once the initial threshold is crossed, successive thresholds are employed to categorise banks into those violating Threshold 1 only, Threshold 1 and Threshold 2 only, or even Threshold 3. The revised PCA framework strengthened the earlier one along several dimensions, the salient changes being as follows: (i) While capital, asset quality and profitability continue to be the key areas for monitoring under the revised framework, common equity Tier-1 (Common equity Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted Assets) ratio has also been included to constitute an additional trigger along with monitoring of leverage. This change acknowledges that it is common equity capital of a bank that has the highest loss-absorption capacity and is the least like debt. Overall, risk thresholds under the revised framework have been made more granular. (ii) Some of the corrective actions which were earlier a part of ‘structured (mandatory) actions’ to be taken by the supervisor have been moved to a more comprehensive menu of ‘discretionary actions’ under the revised framework (detailed comparison is in Annex Ib). Thus, the scope of mandatory actions across all risk thresholds has been restricted essentially to:

(iii) While no restriction has been imposed on the retail deposit-taking activity of any bank till date, banks can be advised under the revised framework as a cost reduction measure to reduce or avoid altogether the high-cost bulk deposits and instead improve their Current Account and Saving Account (CASA) deposit levels. It is useful to compare this Revised PCA Framework of the Reserve Bank to the PCA Framework of the FDIC as an international benchmark. Comparison with the FDIC’s PCA Framework Details of various thresholds as well as the mandatory and discretionary actions under the PCA Framework of the FDIC are given in Annex II. In terms of the conceptual design, both frameworks mirror the core principles of structured early intervention and resolution. However, there are at least three significant differences:

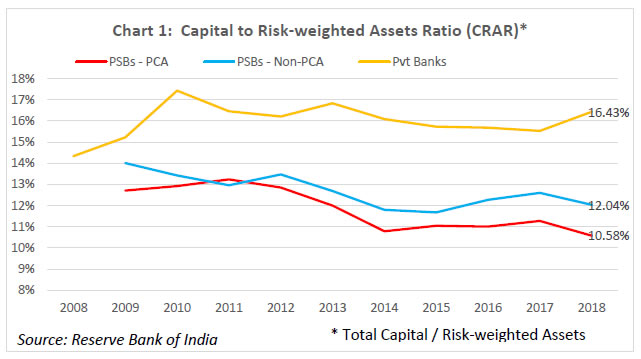

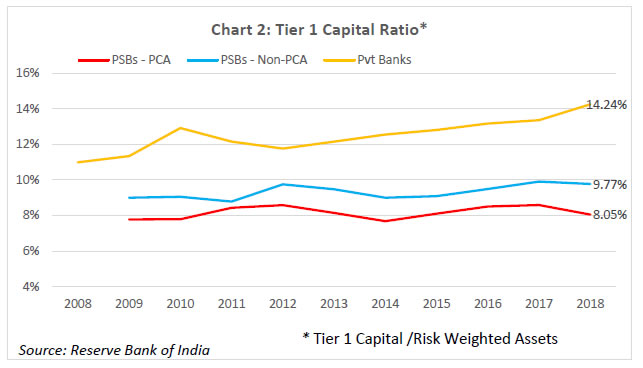

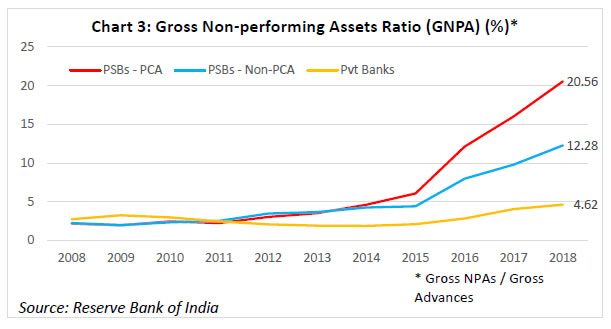

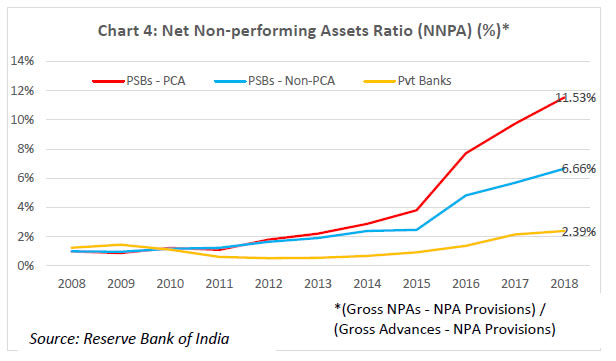

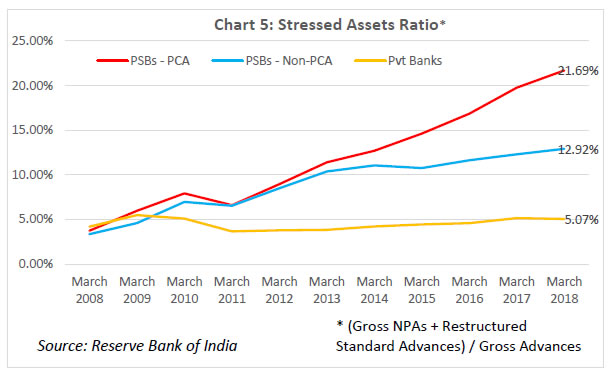

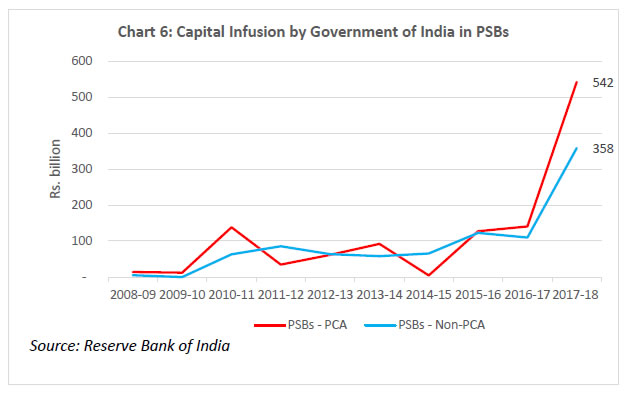

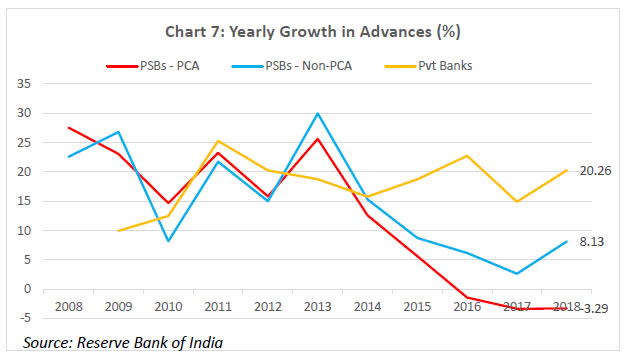

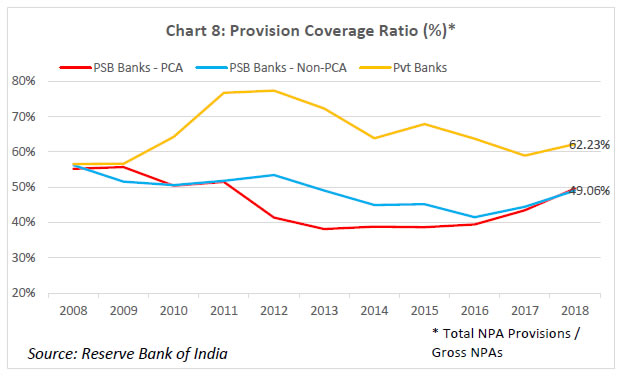

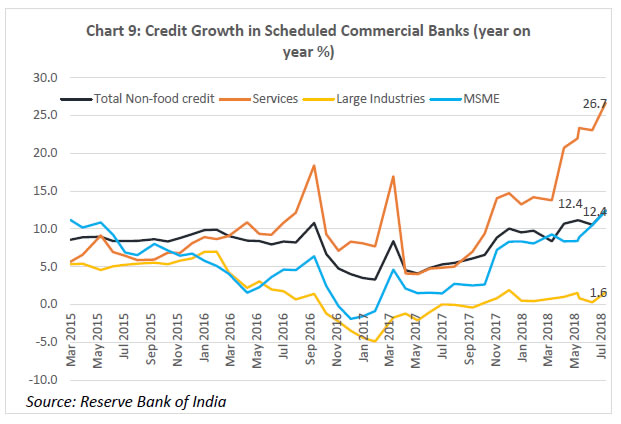

On balance, therefore, it can be concluded that the RBI’s PCA Framework is less onerous as compared to the FDIC’s PCA Framework. Let me elaborate on the point (iii) above. Purchase and Assumption (P&A) is the most commonly used resolution method by the FDIC, as part of which a healthy institution purchases some or all of the assets of a failed bank and assumes some or all of the liabilities. When deciding which of these techniques to employ, the FDIC is guided legislatively by the “least cost to the taxpayers” requirement. The FDIC seeks bids from qualified bidders for the failed bank’s assets and the assumption of certain liabilities, including deposits, and accepts the bid that is judged least costly. If no viable P&A buyer can be found, then the FDIC typically deploys a deposit payoff. A deposit payoff involves repaying insured depositors, liquidating assets of the bank, and, dividing the proceeds from asset liquidation between itself and uninsured bank creditors. The FDIC might also use a Deposit Insurance National Bank (DINB) or bridge banks to resolve a failed bank, which entail establishing a new national bank with a short-period charter from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). The FDIC retains the majority of the assets in its corporate capacity as the receiver and eventually sells them. In India, merger of weak banks with stronger ones has been the primary mode of resolution of weak banks in the past. Section 45 of Banking Regulation Act 1949 empowers the Reserve Bank to make a scheme of amalgamation of a bank with another bank if it is in the depositors’ interest or in the interest of overall banking system. The operation of the weak bank may be kept under moratorium for a certain period of time to ensure smooth implementation of the scheme. Many private sector banks have been merged with other private sector banks or the PSBs under this mechanism. Since the onset of reforms in 1991, there were 22 mergers in the India banking space till 2010, 11 of which were compulsory mergers under Section 45 of the BR Act, 1949 (Bishnoi and Devi, 2015). However, one of the critical preconditions for this approach to succeed is that a substantial part of the banking sector be well-capitalised. If the potential acquirers are poorly capitalised, it may result in inefficiencies in prices as well as timing in resolution of weak banks, besides increasing the risk of weakening the acquirers themselves through such acquisitions. Performance of the PCA banks in India Let me now turn to some data. The goal of the exercise will be to help understand the ten-year performance (wherever data is available) of banks on which the Reserve Bank has imposed the PCA. The reason for examining the performance of these banks over a long time period is to appreciate the fact that the progress of banks under PCA cannot be judged over a relatively short time scale. The longer the under-capitalisation and asset quality problems have festered, the more patient one has to be during the rehabilitation process. There is no quick fix or overnight silver bullet here; the reforms have to be implemented and allowed to run their course; they can’t be chopped or diluted mid-stream; the focus has to be on stability that is durable. As I explain below, there are emerging signs that the performance of banks under PCA is slowly but steadily being restored. Presently, there are twelve banks, eleven in the public sector and one in the private sector, under the Reserve Bank’s Revised PCA Framework, with PCA having been imposed on them between February 2014 and January 2018. I will focus below only on the eleven PSBs under the PCA. The share of these PCA banks in advances and deposits as on March 31, 2018 was 18.5% and 20.8%, respectively. The following trends emerge as one tracks the performance of these banks in terms of capitalisation and asset quality: (i) Capitalisation (Chart 1, 2): The declining trend of CRAR and Tier-1 capital ratio for PCA banks that started in 2011 has been arrested and the ratio has been maintained steady since 2014 at or above internationally prescribed levels. It may, however, be noted that the PCA banks have had lower CRAR and Tier-1 capital ratios compared to non-PCA banks (barring 2011), and especially private banks (right since 2009). (ii) Asset quality (Charts 3, 4, 5): Both the gross and net NPA ratios of PCA banks mirrored those of non-PCA banks up until about 2014. However, post the Asset Quality Review (AQR) exercise, the NPA recognition at PCA banks has led to a sharper rise in both gross and net NPAs, relative to non-PCA banks, and especially relative to private banks. This does not mean that AQR caused the NPAs; it simply induced the long-overdue recognition of NPAs. Notably, the stressed assets ratio, which besides NPAs includes the Restructured Standard assets (that enjoyed the regulatory forbearance under the earlier guidelines), reveals that the underlying asset quality at PCA banks was deteriorating at a sharper pace compared to non-PCA banks right since 2011, which is now accepted as the time by which the lending boom of 2009-10 began to unravel. The Tide is Turning for the PCA Banks… As I have tried to explain, an important objective of the PCA is to first and foremost limit further losses and prevent erosion of bank capital, creating a platform of stability for the bank, and in turn, setting the stage for structural interventions to be implemented and pushed through. In assessing whether this objective is being attained, three observations are in order: (i) Recapitalisation (Chart 6): The Government of India has infused more than Rs. 2,300 billion in public sector banks since 2005, more than half of which has gone into banks currently under PCA. Within PCA banks, almost half of the total infusion (i.e., Rs. 635 billion) has occurred during FY2018 and FY2019, after the banks were classified under PCA. This recapitalisation has been an important contributor to financial stability of these banks and of the rest of the banking system they deal with. (ii) Preventing further deterioration (Chart 7): In spite of their worse capitalisation and stressed assets ratio compared to other banks, PCA banks had credit growth that was as strong as that of other banks up until 2014. However, since the AQR exercise and the imposition of PCA, the year on year growth in advances for PCA banks has declined from over 10% in 2014 to below zero (contraction) by 2016 and remained in the contraction zone since. Given the evidence presented above on PCA bank’s sustained problem of asset quality (Charts 3, 4 and 5), this is indeed the required medicine to prevent further hemorrhaging of their balance-sheets. (iii) Improvement in provision coverage ratio (Chart 8): Given the recapitalisation and prevention of further hemorrhaging, the provision coverage ratio (PCR) of PCA banks which had fallen off relative to that of other banks starting 2011 and reached below 40% during 2012-2016, has now recovered to that of non-PCA PSBs. The recovered level of PCR remains at present at around 50%, which is more 10% below that of private banks, and away from the desirable 70%. These numbers suggest that the loss-absorption capacity of PCA banks is on the mend, but that there is some distance to go in their catch-up to healthy levels. There is an assertion being made in some circles that imposition of the PCA has starved the Indian economy of credit. There is little factual basis for this assertion, either for the overall economy or at sectoral level. While it is true as shown above that PCA banks are experiencing lending contraction on average (in terms of their year on year growth in overall advances), the nominal non-food credit growth of scheduled commercial banks has been close to or above double-digit levels, for past several quarters, and with a robust distribution across the sectors of the real economy (Chart 9). This is because the reduction in lending at PCA banks is being more than offset by credit growth at healthier banks. This is indeed what one wants – efficient reallocation of credit for the real economy with a financially stable distribution of risks across bank balance-sheets. Indeed, the funding for the economy as a whole has become diversified over this period, also due to the growth of capital markets. There is also a call for more lending by PCA banks to large industries where the overall credit growth remains muted. Note that many of these industries are heavily indebted to start with and are going through a deleveraging process under the IBC (so that at present, their sectoral capacity is still somewhat in excess and credit demand itself weak). The key point is that PCA banks are de-risking the asset side of their balance sheets by moving away from riskier sector loans to less riskier ones and government securities; the first and foremost priority is to limit (effectively, taxpayer) losses at PCA banks and prevent further erosion of their capital. Conclusion Let me conclude. I have tried to explain why adequate bank capital is critical to fortify bank balance-sheets and a key indicator for the bank supervisors to closely monitor; and, how the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework is employed internationally by bank supervisors and regulators as an accepted form of structured early intervention and resolution, designed to help banks regain health by preserving capital. I then briefly explained the primary features of the Reserve Bank’s PCA framework, which is an essential element of its apparatus for safeguarding overall financial stability. The evidence I presented suggests that without the PCA imposition, some banks would have incurred even higher losses and required even more of taxpayer money for recapitalisation. Imposition of PCA can thus be seen as first, stabilising the banks at risk, and then, undertaking the deeper bank reforms needed for long-term viability of the business model of these banks. It is important, therefore, that the PCA framework to deal with financially weak banks is persisted with. Any slackening of the approach in the midst of required course action is an all too familiar and ultimately harmful habit that we must eschew. Well begun is only half done, as they say! References Acharya, Viral V. (2017) “The Unfinished Agenda: Restoring Public Sector Bank Health in India,” R K Talwar Memorial Lecture, Indian Institute of Banking and Finance. Acharya, Viral V., Sascha Steffen and Lea Steinruecke (2018) “Kicking the Can Down the Road: Government Interventions in the European Banking Sector,” Working Paper, Frankfurt School of Management and Finance. Benston, George and George Kaufman (1990) “Understanding the Savings and Loan Debacle,” The Public Interest, Spring, pp. 79-95. Bishnoi, T.R. and Sofia Devi (2015) “Mergers and Acquisitions of Banks in Post-Reform India,” Economic & Political Weekly, 50(37), pp. 50-58. Granja, Joao, Gregor Matvos and Amit Seru (2017) “Selling Failed Banks,” Journal of Finance, 72(4), pp. 1723-1784. Hoshi, T. and A.K. Kashyap (2010) ‘Will the U.S. bank recapitalization succeed? Eight lessons from Japan,” Journal of Financial Economics 97, 398–417. Myers, Stewart (1977) “Determinants of Corporate Borrowing,” Journal of Financial Economics, 5, pp. 147-175. Patel, Urjit R. (2018) “Banking Regulatory Powers Should be Ownership Neutral,” Inaugural Lecture – Center for Law & Economics; Center for Banking & Financial Laws, Gujarat National Law University. White, Larry (1991) “The S&L Debacle: Public Policy Lessons for Bank and Thrift Regulation,” Oxford University Press. Annex Ia: RBI’s Revised PCA Matrix (April 2017) - Indicators and risk thresholds

Annex Ib: Mandatory and discretionary corrective actions under RBI’s Old (2002) and Revised (2017) PCA Frameworks

1 I am grateful to Governor Dr. Urjit R. Patel and Deputy Governor N. S. Vishwanathan for their constant encouragement, feedback and guidance. I also thank Vaibhav Chaturvedi for his excellent support throughout the preparation of this speech; R Gurumurthy, Jagan Mohan, B Nethaji, Sooraj Menon and Vineet Srivastava of the Reserve Bank of India; and, my co-authors, Sascha Steffen of Frankfurt School of Management and Finance and Lea Steinruecke of University of Mannheim. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

পেজের শেষ আপডেট করা তারিখ: