IST,

IST,

II: Fiscal Position of Municipal Corporations

|

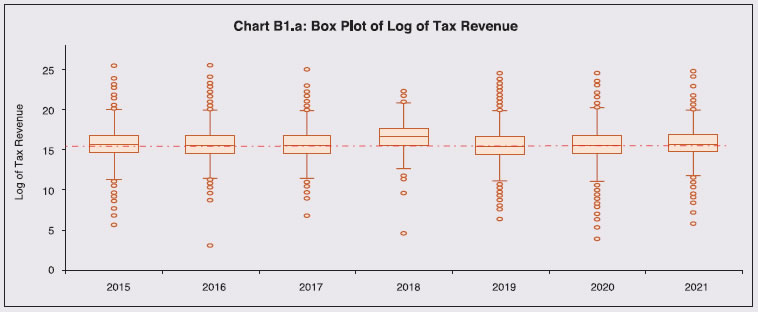

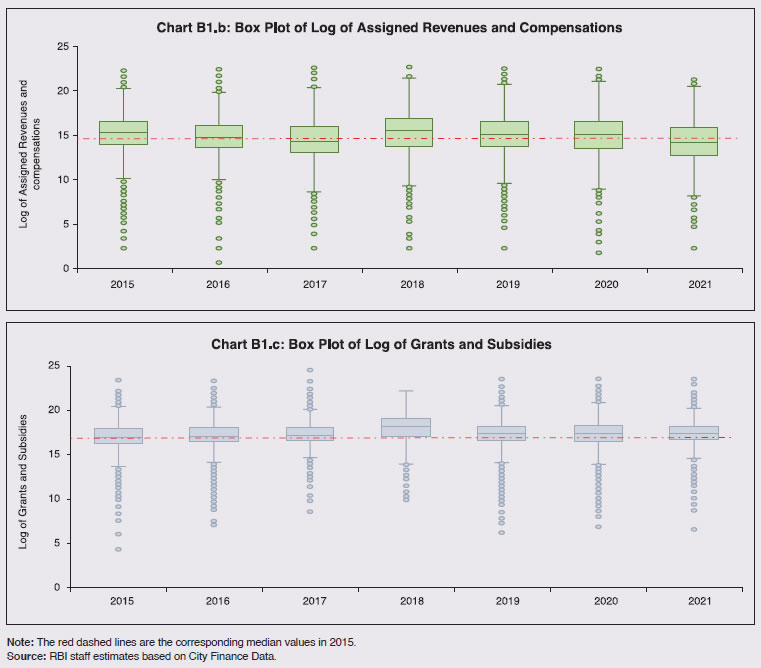

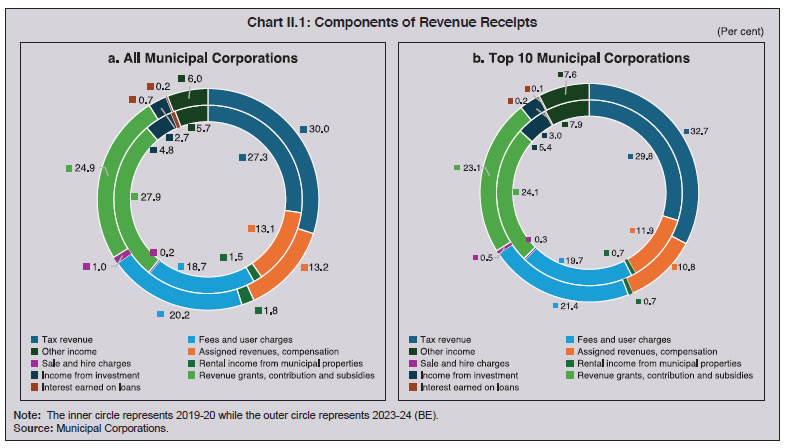

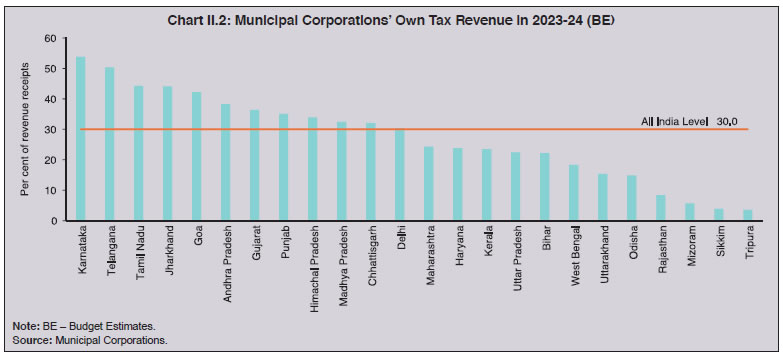

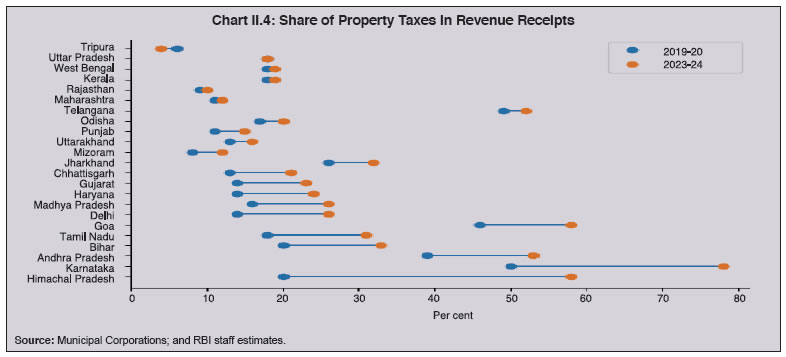

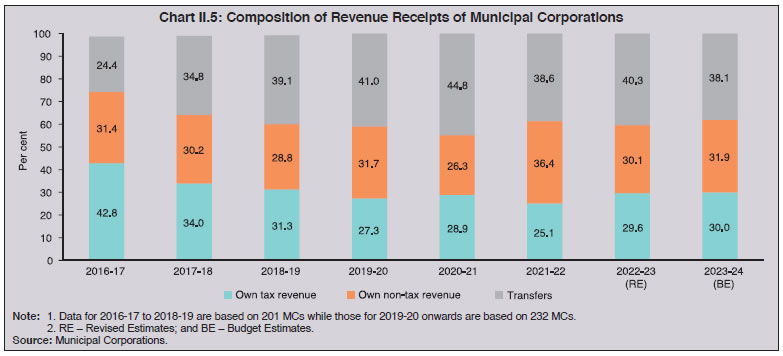

The municipal revenues, which were hit during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-21, recovered in 2021-22 and 2022-23. Despite significant responsibilities, the revenue streams of municipalities are limited and pale in comparison to those of State and Central governments. The revenues of municipal corporations (MCs) show concentration, with the top 10 MCs accounting for over 58 per cent of the total municipal revenue receipts in India. Property taxes are the major constituent of tax revenues. Municipal bond financing has seen some recovery in recent years. MCs are also venturing into green municipal bonds to fund environmentally beneficial projects, marking a pivotal move towards sustainable urban development. II.1 In India, urban areas contribute around 60 per cent of the country’s GDP (NITI Aayog, 2022).1 Municipal corporations (MCs), the third tier of the government in large urban areas, generate their own revenues in terms of taxes and fees, apart from grants from the higher levels of the government and are also responsible for the provision of local public services. II.2 This Chapter analyses the financial position of MCs in India from 2019-20 to 2023-24 (BE). It is organised into five sections. Section 2 examines receipts of MCs from 2019-20 to 2023-24 (BE), focusing on own tax revenue, non-tax revenue, and transfers. Municipal expenditure is discussed in section 3 while section 4 presents details on their borrowings and municipal bond financing. Finally, section 5 sets out some conclusions along with the way forward. II.3 Municipal revenue receipts, which were subdued during 2020-21, grew by 22.5 per cent in 2021-22 mainly due to rise in non-tax revenues. The growth in the revenue receipts moderated to 3.7 per cent in 2022-23 (RE) and was budgeted to increase by 20.1 per cent in 2023-24 [Table II.1a]. Despite significant responsibilities, MCs’ revenue receipts are quite modest (0.6 per cent of GDP in 2023-24) and pale in comparison to those of Central and State governments (9.2 per cent and 14.6 per cent of GDP in 2023-24, respectively). Revenue receipts of MCs exhibit concentration, with the top 10 MCs accounting for over 58 per cent of total municipal revenue receipts (Table II.1b). The consolidated budgets of the municipalities indicate a surplus on the revenue account. The surplus fell to ₹1,034 crore in the pandemic year 2020-21 from ₹4,914 crore in 2019-20. It was budgeted higher at ₹20,819 crore in 2023-24. II.4 The surplus in 2023-24 was budgeted at above ₹1,000 crore in States like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, and Telangana, led by Maharashtra (₹11,104 crore). The surplus in MCs in Delhi, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Odisha, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu was placed in the range of ₹100 crore (Tamil Nadu) to ₹687 crore (Delhi). In contrast, MCs in Tripura, Jharkhand, Himachal Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, and Kerala budgeted for a revenue deficit in the range of (-) ₹2 crore (Tripura) to (-) ₹789 crore (Kerala) for 2023-24 (Table II.2). II.5 The revenues of the MCs relative to those of their respective State governments differ widely; the ratio is the highest in Delhi [34.5 per cent in 2023-24 (BE)] followed by Maharashtra (14.1 per cent), and Gujarat (7.8 per cent) [Table II.3]. Aggregate revenue receipts of MCs were 6.3 per cent of the Central government’s revenue receipts [2023-24 (BE)]. II.6 The revenue receipts of MCs, including own tax revenue, own non-tax revenue, and transfers, amounted to 0.6 per cent of GDP in 2023-24 (the same as in 2019-20) [Table II.4a]. Tax revenues are the largest source of revenue of the MCs (30.0 per cent of the total revenue receipts) followed by revenue grants, contributions, and subsidies (24.9 per cent) and fees and user charges (20.2 per cent). The other major revenue sources include assigned revenues, compensation, and rental income from municipal properties (Table II.4 and Chart II.1a). The revenue receipt pattern of the top 10 municipal corporations is largely the same (Chart II.1b).  II.7 The ratio of MCs’ tax and non-tax revenue to the respective State government’s tax and non-tax revenue varied across States, indicating a vertical imbalance. The MCs in Delhi and Maharashtra have higher ratios in both tax and non-tax revenue, while those in Sikkim and Tripura are lower. Mizoram, and Jammu and Kashmir, on the other hand, have lower non-tax revenue shares (Table II.5). MCs’ tax and non-tax revenues were 2.2 per cent and 13.6 per cent of the Central government’s tax and non-tax revenue, respectively, in 2023-24 (BE).2 2.1 Own Tax Revenue II.8 Own tax revenue, inclusive of property tax, water tax, electricity tax, education tax, and other local taxes, constituted 30.0 per cent of total revenue during 2023-24 (BE), with significant variations across States (Chart II.2). The ratio was the highest in Karnataka (53.8 per cent), followed by Telangana (50.3 per cent), Tamil Nadu (44.3 per cent) and Jharkhand (44.0 per cent). II.9 Property taxes are a major source of own tax revenue of the MCs in India, constituting more than 16 per cent of revenue receipts and more than 60 per cent of their own tax revenue (Charts II.3a and II.3b). Wide variation is, however, observed in the relative importance of property tax revenues across MCs which can be attributed, inter alia, to differences in tax rates, collection efficiency, and the overall economic environment of each State (Chapter 3). II.10 Between 2019-20 and 2023-24, the share of property taxes in revenue receipts increased in States such as Himachal Pradesh (38 percentage points), Karnataka (28 percentage points), Andhra Pradesh (14 percentage points), and Bihar (13 percentage points). In Uttar Pradesh the share was unchanged over the same period while it declined in Tripura by two percentage points (Chart II.4).  2.2 Own Non-Tax Revenue II.11 Non-tax revenue, which accounted for around 32 per cent of total revenue receipts of MCs during 2023-24 (BE), is dominated by fees and user charges, followed by income from investment and other income (Table II.6a). Non-tax revenue of the top 10 MCs accounted for 33.3 per cent of their revenue receipts during the same period (Table II.6b). ![Chart II.3a: Share of Property Taxes in Revenue Receipts in 2023-24 (BE) [Per cent], Chart II.3b: Share of Property Taxes in Own Tax Revenue in 2023-24 (BE) [Per cent]](/documents/87730/28909807/02FISCAL13112024_C3.jpg)  2.3 Transfers II.12 The total grants from the Central government and the State governments to the MCs increased by 24.9 per cent and 20.4 per cent, respectively, in 2022-23 [Table II.7]. II.13 Transfers from the State governments in the form of assigned revenues, compensation, State Finance Commission (SFC) grants and other State government grants were range bound at 30 per cent of revenue receipts of the MCs during 2019-20 to 2022-23 and were budgeted at 28.7 per cent in 2023-24 (BE). Transfers from the Central government accounted for 2.5 per cent of the total revenue receipts of the MCs during the recent years (Table II.8).  II.14 Overall, in the post-GST period (2017-18 onwards), own tax revenue as a ratio of total revenue has come down for the MCs (Chart II.5). On the other hand, the share of transfers in total revenue has increased, indicating the rise in vertical dependence of the MCs on the upper tiers of the government (Box II.1). This is, however, not a reflection on the substantial gains that GST implementation has rendered to the economy.

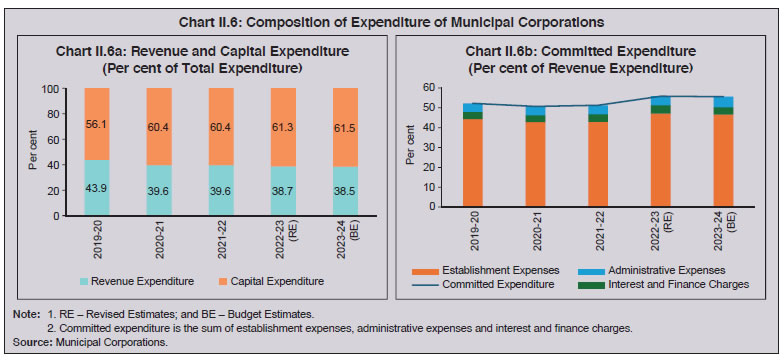

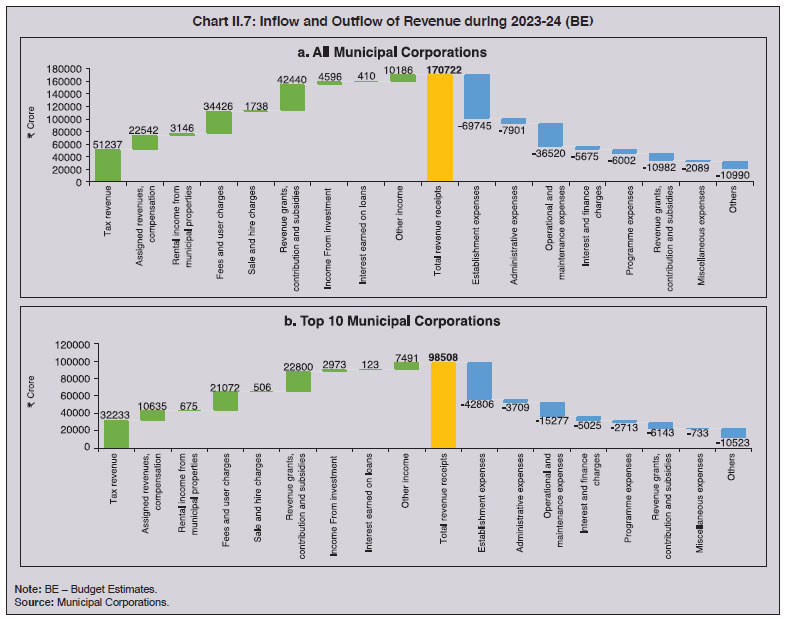

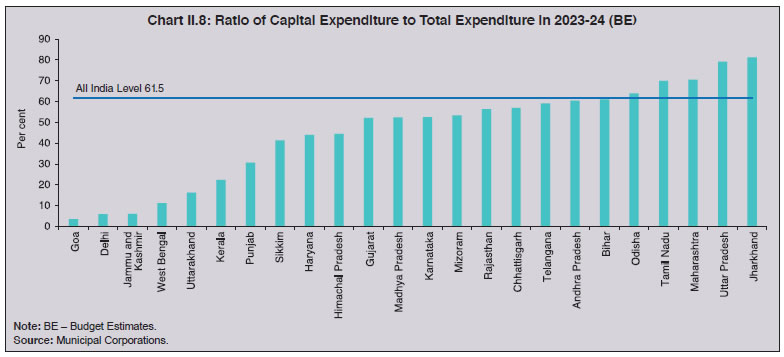

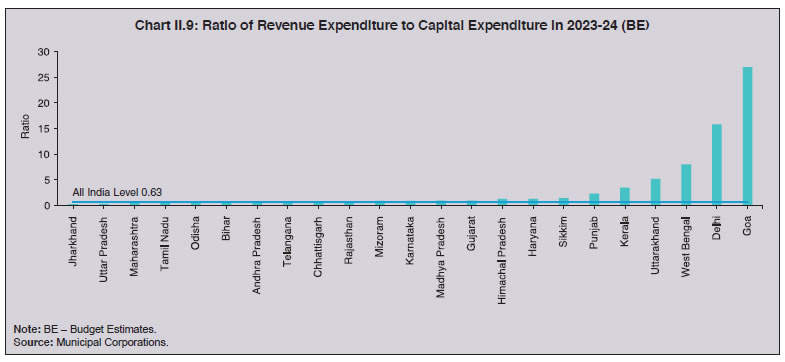

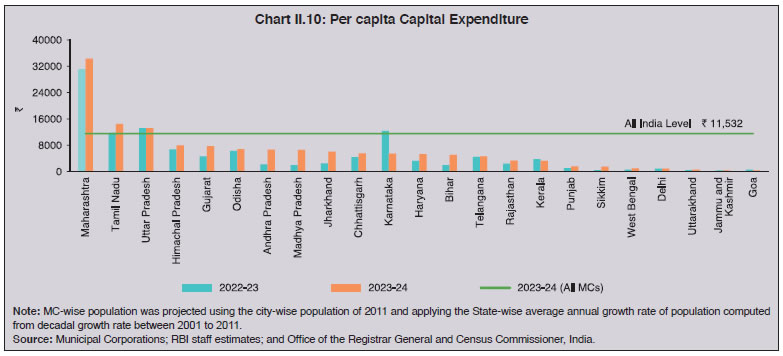

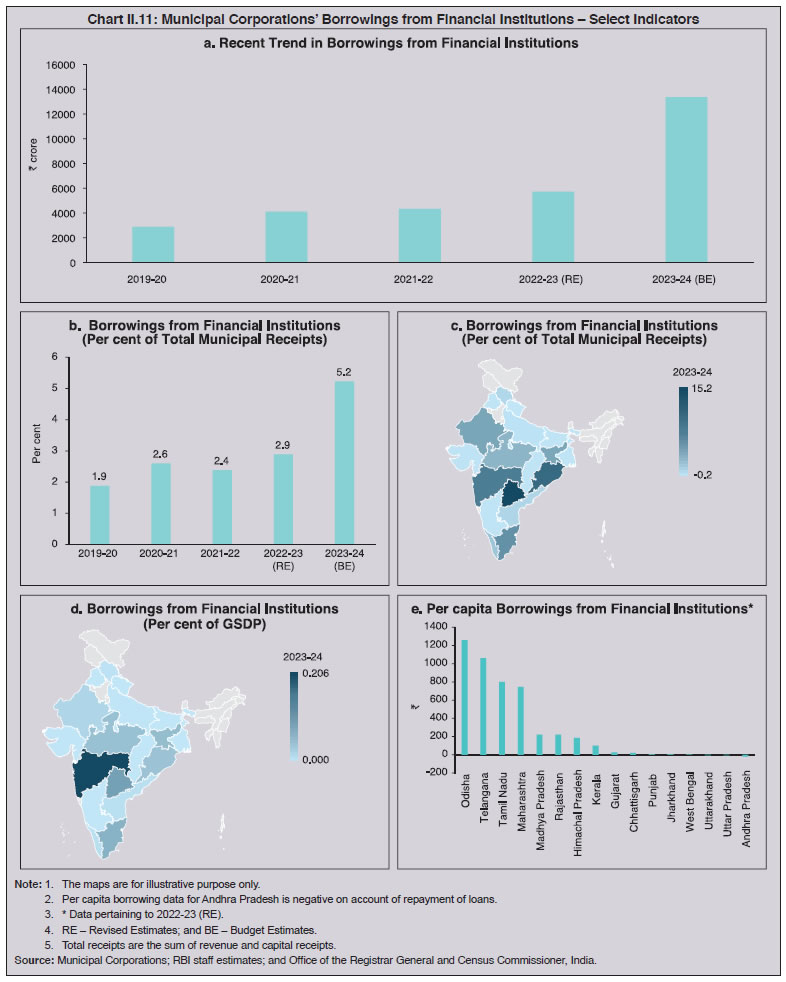

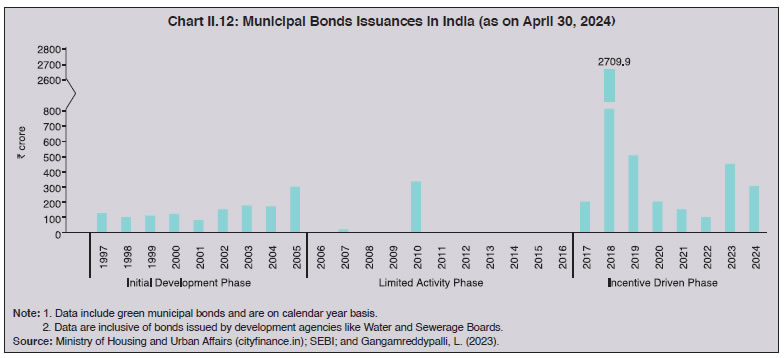

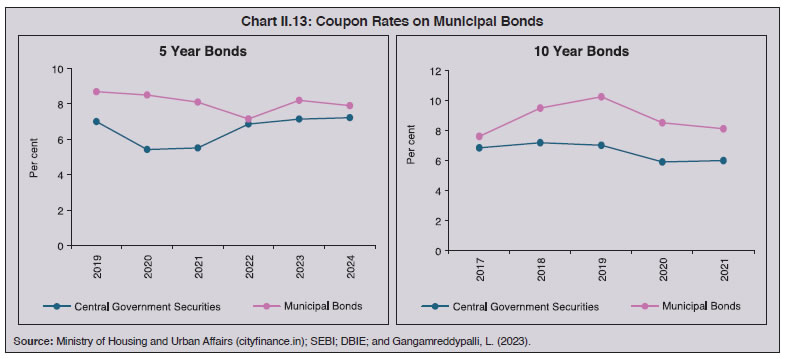

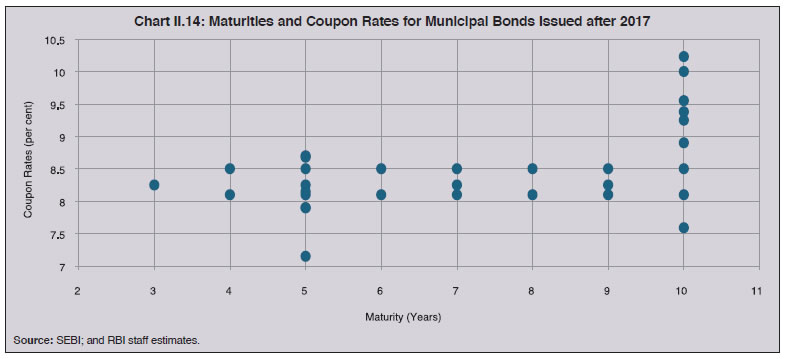

II.15 The total expenditure (revenue and capital spending combined) of the MCs increased slightly from 1.2 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 to 1.3 per cent of GDP in 2023-24 (BE). The revenue expenditure/GDP ratio hovered around 0.5 per cent of GDP, while the capital expenditure/ GDP ratio increased from 0.7 per cent to 0.8 per cent during this period (Table II.9). 3.1 Revenue Expenditure II.16 The share of revenue expenditure3 in total expenditure of the MCs has declined from 43.9 per cent in 2019-20 to 38.5 per cent in 2023-24 (BE) with concomitant increase in capital expenditure4 share from 56.1 to 61.5 per cent (Chart II.6a). Within revenue expenditure, the share of committed expenditure (establishment expenses, administrative expenses and interest and finance charges) has moved in a range of 50.7 to 55.6 per cent during 2019-20 to 2023-24 (BE) [Chart II.6b]. II.17 In 2023-24, a large part of revenue receipts of MCs was budgeted to be derived from taxes, revenue grants, contributions, and subsidies and fees and user charges. On the outgoes side, establishment expenses and operational and maintenance expenses accounted for a major part of the revenue expenditure (Chart II.7a and II.7b). 3.2 Capital Expenditure II.18 The primary areas of capital expenditure of the MCs are fixed assets and capital work-in-progress (Table II.10). II.19 The proportion of capital expenditure in total expenditure for the MCs was 61.5 per cent in 2023-24 (BE) as compared with 24.8 per cent and 21.4 per cent for State governments and the Central government, respectively [2023-24 (BE)]. It may, however, be noted that total expenditure of MCs is modest relative to State governments and the Central government. In 2023-24, total expenditure of MCs was 1.3 per cent of GDP as compared with 16.3 per cent for the State governments and 15.1 per cent for the Central government. II.20 The ratio of capital expenditure to total expenditure for MCs has large inter-state variations, with the shares in Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana being more than 50 per cent in 2023-24 (BE) [Chart II.8].   II.21 The ratio of revenue expenditure to capital expenditure, a summary indicator of the quality of government expenditure, was 0.63 for the MCs in 2023-24 (BE) as against 3.7 for the Centre and 3.0 for the States [Chart II.9].  II.22 The all-India per capita capital expenditure by MCs was budgeted at ₹11,532 in 2023-24, an annual average growth of 10.5 per cent over ₹8,547 in 2020-21. The per capita capital spending of the MCs in Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu exceeded the all-India level during 2023-24 (Chart II.10). II.23 Borrowings by the MCs from the financial institutions (secured and unsecured) in India increased from ₹2,886 crore during 2019-20 to ₹13,364 crore during 2023-24 (BE) [Chart II.11a]. Borrowings from financial institutions accounted for 5.2 per cent of total municipal receipts in 2023-24 (BE) as compared with 1.9 per cent in 2019-20 (Chart II.11b). The MCs in Odisha and Telangana had higher shares at 14.4 per cent and 15.1 per cent, respectively, in these two years (Chart II.11c). Municipal borrowings remain negligible at less than 0.05 per cent of GDP for all the MCs (Chart II.11d). The highest level of per capita borrowings from financial institutions was observed in Odisha (₹1,258) in 2022-23 (RE) [Chart II.11e].   4.1 Municipal Bond Financing II.24 The evolution of the municipal bond market in India can be categorised into three distinct phases (Gangamreddypalli, 2023). During the initial phase of development (1995 to 2005), the municipal bond market was supported by the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Financial Institutions Reform and Expansion - Debt (FIRE-D) project. Between 1995 and 2005, ten municipal corporations and other civic bodies raised a total of ₹1,325 crore. Bengaluru was the first to issue a bond worth ₹125 crore in 1997 (Chart II.12). Most of these bonds were tax-free and primarily financed road construction, water and sewerage projects. Bond issuances declined during 2006 to 2016, inter alia, due to the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) grants, which offered ₹1 lakh crore to the qualifying corporations, thereby obviating the need for issuing municipal bonds (Gangamreddypalli, 2023).5 II.25 There was a pick up in municipal bond issuances during 2018-19, attributable to factors such as the regulatory framework on municipal bonds6 issued by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and the 2018 Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) scheme which offered grants for bond issuance.7 Bond activity dipped during 2020-22 due to the pandemic but has seen some recovery during 2023 and 2024. In 2023, the SEBI introduced the Information Database and Repository on Municipal Bonds to guide corporations on issue and listing of Municipal Debt Securities. Further, the National Stock Exchange (NSE) India Limited launched country’s first Municipal Bond Index in 2023, tracking the performance of municipal bonds issued by 10 investment-grade rating corporations, with a base value of the index equal to 1,000 for 2021. This initiative is likely to increase transparency in the municipal bond market and encourage investor participation.   II.26 Municipal bonds worth ₹4,204 crore were outstanding as on March 31, 2024 (0.01 per cent of GDP) as compared with ₹1,100 crore as on March 31, 2005 (0.03 per cent of GDP). All the bonds issued since 2016-17 are taxable, unlike the initial development phase. The coupon rates on municipal bonds have generally moved in tandem with those on Central government bonds in recent years (Chart II.13). II.27 The coupon rates on municipal bonds increase with maturity, consistent with the term structure hypothesis8 (Chart II.14).  II.28 Municipal bonds delivered an average return of 8.5 per cent during 2023-24, as compared with 8.3 per cent and 7.3 per cent on the NIFTY Medium Duration G-Sec Index and NIFTY AAA Medium Duration Corporate Bond Index, respectively (Table II.11). II.29 The Indian municipal bond market remains in a nascent stage. As of March 2024, the total municipal bonds outstanding at ₹4,204 crore was just 0.09 per cent of the total corporate bonds outstanding.9 Most municipal bonds are privately placed with select investors, limiting the investor base. Ahmedabad (in 1998 and 2019) and Indore (in 2023) offered public bond issues. An improvement in the financial performance and credit ratings of the MCs is critical for promoting investor confidence and broadening market participation. Credit rating agencies have rated the MCs as investment grade so far (Table II.12).  4.2 Green Municipal Bonds II.30 Amidst increasing awareness about climate-related risks, local bodies have started issuing green bonds to finance projects with positive environmental impacts. The issuance of municipal green bonds began in the United States in 2014, followed by similar initiatives by cities and municipalities in Europe. In India, municipal green bond issuance started in 2021, when Ghaziabad Nagar Nigam raised bonds worth ₹150 crore for setting up a tertiary water treatment plant (Table II.13). This was followed by Indore in 2023 and Ahmedabad and Vadodara in 2024. Municipal green bonds worth ₹694 crore have been raised in 4 years for different green projects. The market for green municipal bonds is still at a nascent stage and the process of issuing a green bond involves additional costs for green audits and monitoring key performance indicators (GIZ, 2017). As the market matures and expands, these costs are expected to come down. II.31 Despite the critical role of municipal corporations in urban governance, their financial capacity remains limited, hampering their ability to provide essential services and drive urban development effectively. The recent increase in municipal bond financing is a positive development, but it remains modest. The introduction of green bond financing by some MCs is a promising step toward sustainable urban growth. II.32 The MCs rely heavily on the upper tiers of government for revenues, which can limit their financial autonomy and capacity to plan and execute long-term projects. This underscores the need for State-specific strategies to strengthen MC revenues and finances and achieve better urban development outcomes through reforms in local taxation, better enforcement of tax laws, and innovative non-tax revenue streams. At the same time, given the large dependence on transfers from the State governments, timely, adequate and rule-based frameworks for transfers from the upper tier authorities would help the MCs to fulfil their functional obligations effectively and efficiently and contribute to urban development. Finally, building institutional capacity through training in financial management is crucial for the transparent and effective use of the resources available with the MCs, positioning Indian cities as leaders in climate-resilient urban development. 1 NITI Aayog (2022), Cities as Engines of Growth. pp-2. 2 Data for Central government’s tax and non-tax revenue for 2023-24 are based on provisional accounts. 3 Revenue expenditure includes committed expenses such as establishment expenditure (salaries and pension expenses); administrative expenses (audit and legal fee, office maintenance expenses) and interest and finance charges; such expenditure is necessary for day-to-day operations but do not contribute to long-term asset creation. 4 Capital expenditure involves significant investments in long-term assets like land, building, parks and playgrounds, roads and bridges, public lighting, statues, and heritage assets. 5 Out of the total Central Government share of ₹66,085 crore for the period 2005-2012, ₹40,584 crore had been released under JNNURM, up to 2011-12 (Report No. 15, Performance Audit of Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, 2012-13, Comptroller and Auditor General of India, GoI). 6 In March 2015, SEBI passed regulations to facilitate issuance of municipal debt and listing of debt securities by municipalities in India. This helped in clarifying the regulatory status of the municipal bonds and rendered them safer for investors. 7 In order to encourage ULBs to raise resources from the market, AMRUT Mission introduced financial incentives in the form of a lump-sum grant-in-aid for municipal bond issuances at a rate of ₹13 crore per ₹100 crore of bonds issued, with a ceiling of a maximum of ₹200 crore of bonds. This incentive was structured as a first-come, first-serve reward for 10 ULBs in a financial year (MoHUA and Gangamreddypalli, 2023). So, while AMRUT incentivised bond issuances, JNNURM crowded out the demand for market debt. 8 The ‘term structure hypothesis’ posits that the yield on a long-term bond is equal to the average expectation of the short-term yield over the life of the long-term bond plus a risk premium. 9 Data for municipal bonds outstanding is sourced from NSE and SEBI, while the data for corporate bonds outstanding, which equals ₹47,28,935 crore, has been taken from CEIC. |

Page Last Updated on: