IST,

IST,

Monetary Policy Report - April 2023

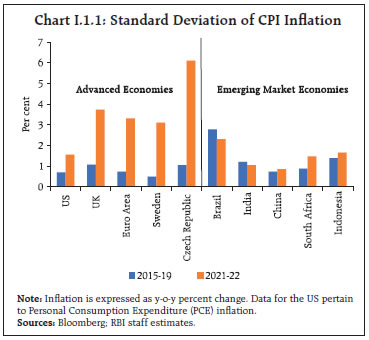

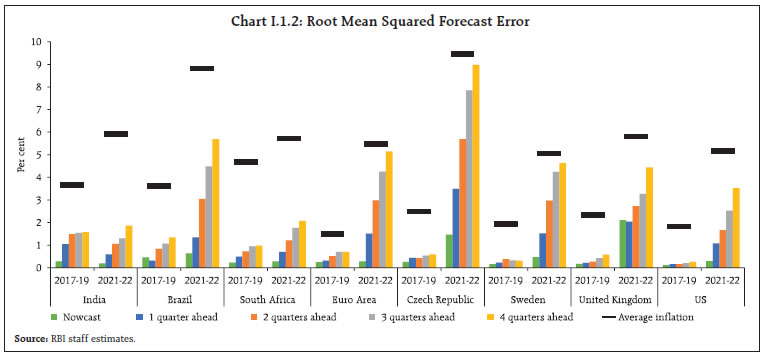

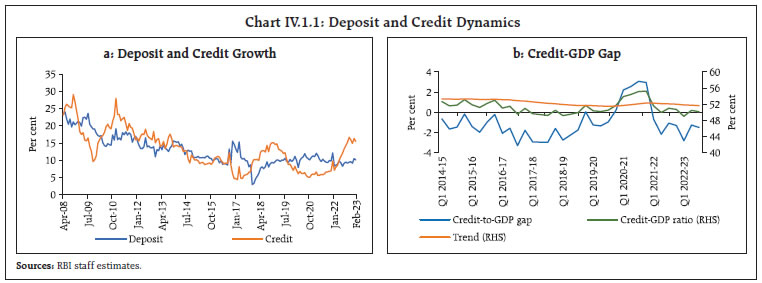

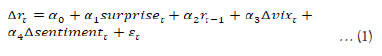

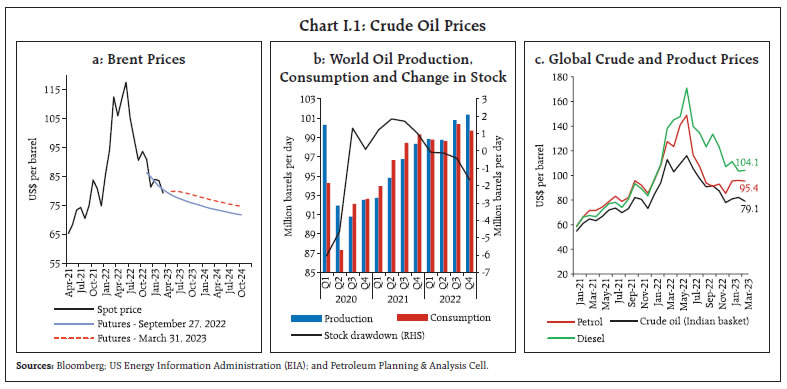

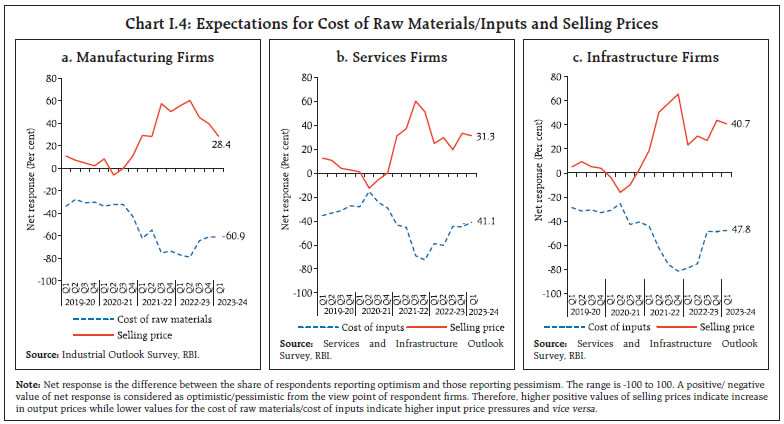

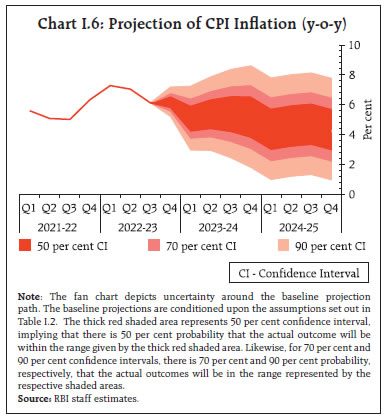

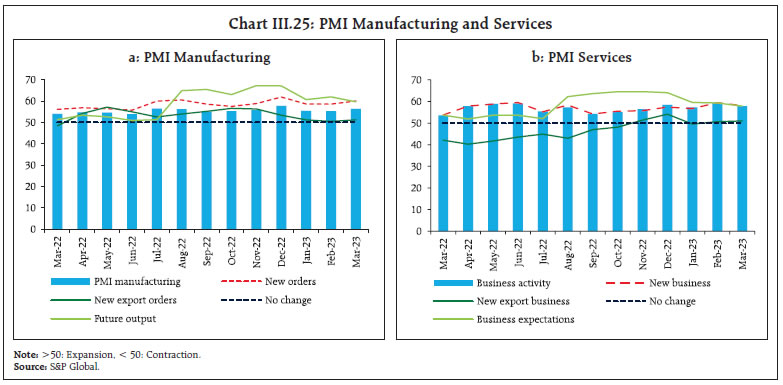

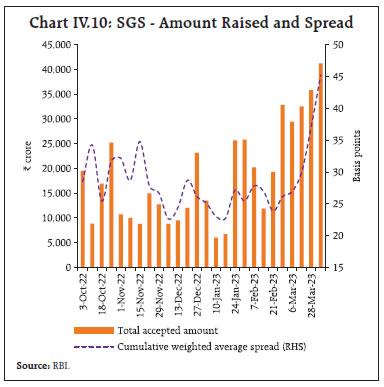

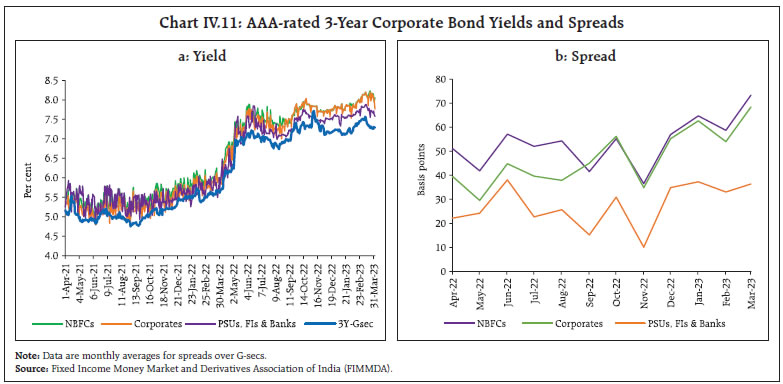

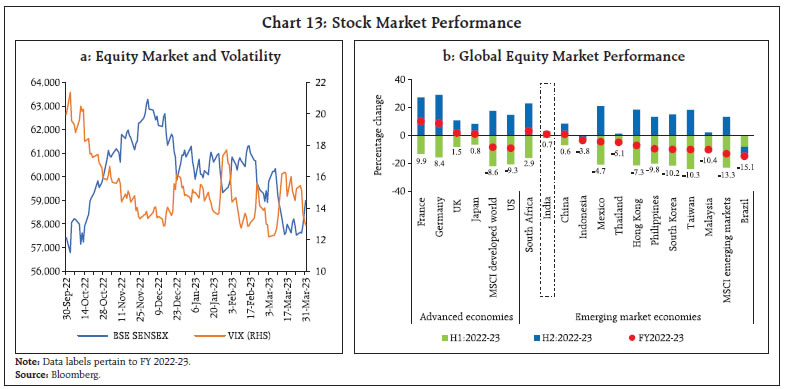

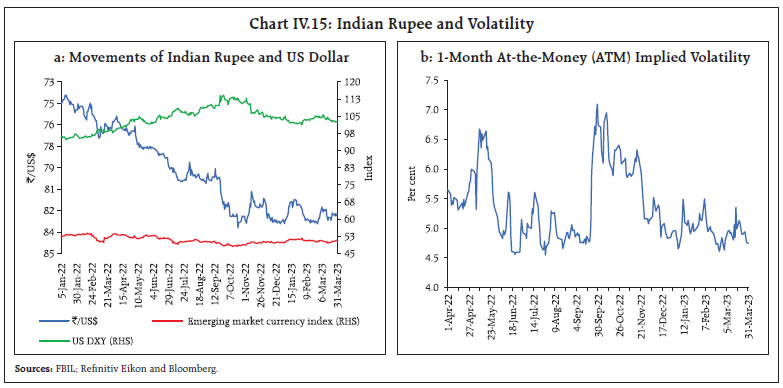

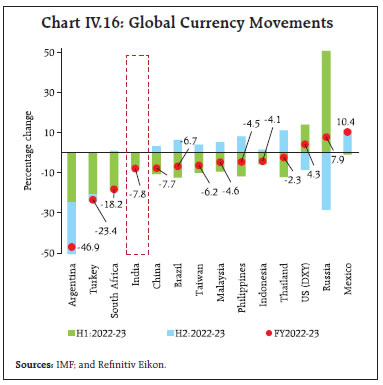

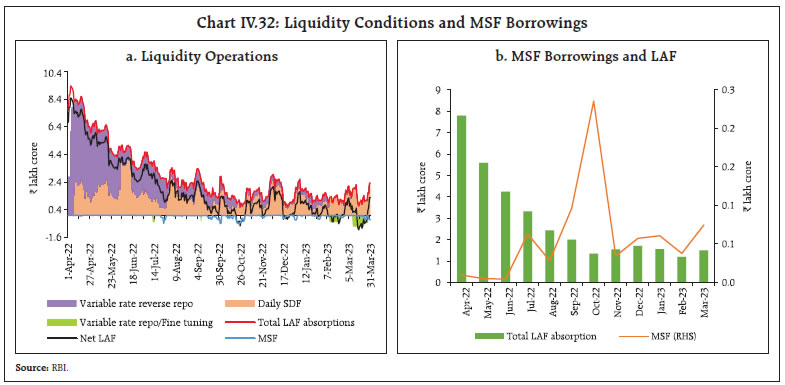

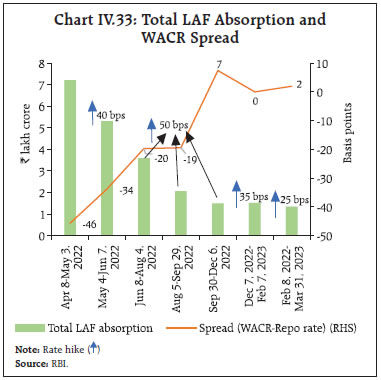

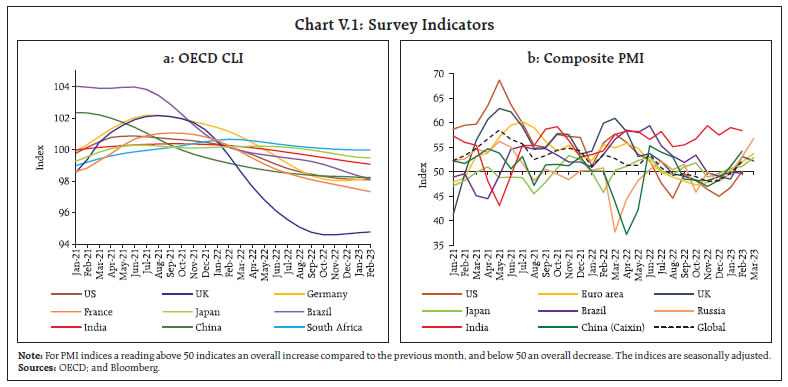

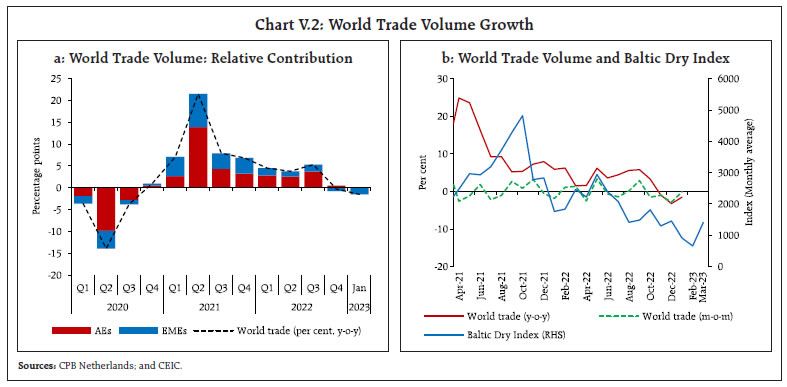

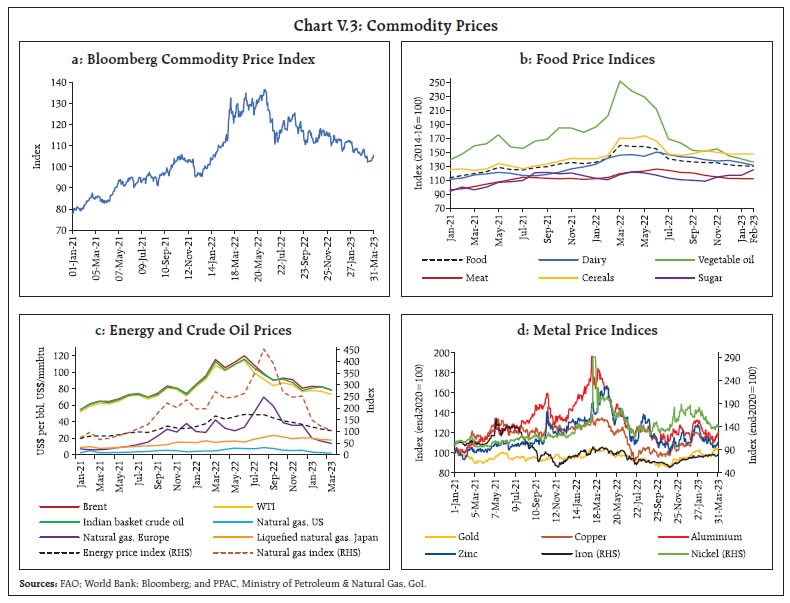

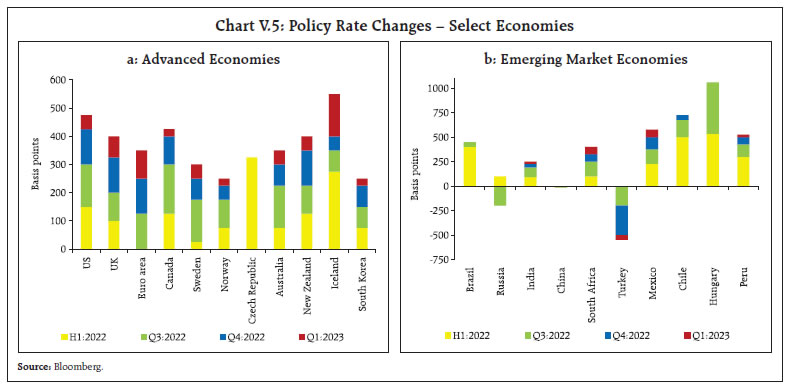

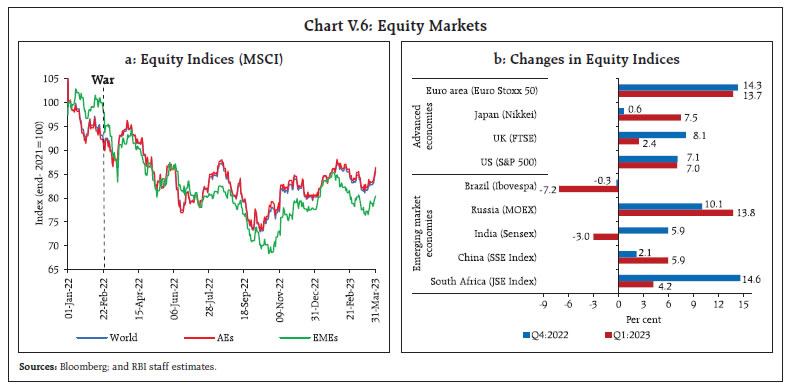

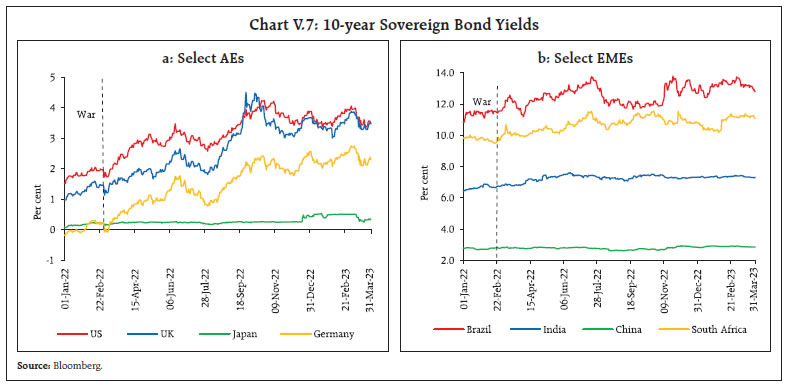

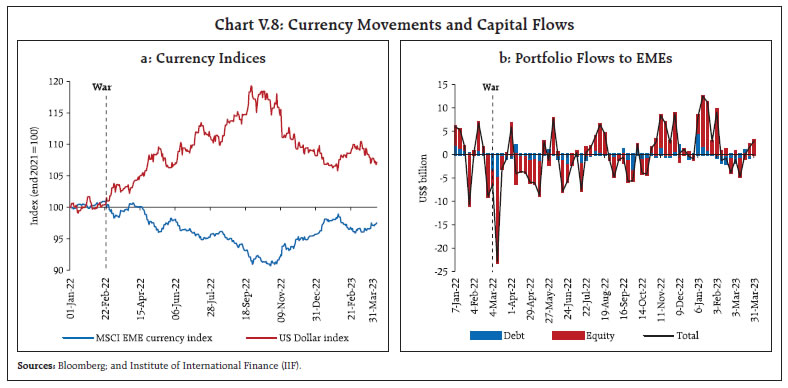

Domestic economic activity remains resilient in a slowing global economy. Inflation has persisted at elevated levels across the world and in India. Monetary policy remains focussed on progressively aligning inflation with the target. Geopolitical hostilities, volatile global financial markets and climate shocks are the key risks to the growth and the inflation outlook. I.1 Key Developments since the September 2022 MPR Since the release of the September 2022 Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the persistence of inflation at elevated levels across economies, continuing geopolitical uncertainties, and tightening financial conditions are taking their toll on global economic activity. Most central banks remain in tightening mode. Financial markets have turned volatile and highly sensitive to incoming information. Sovereign bond yields softened during November-December on hopes of a monetary policy pivot towards smaller rate hikes but hardened during February on stronger than anticipated economic activity and unrelenting price pressures. US short-term bond yields reached their highest levels in a decade and a half in early March. Equity markets recovered some lost ground. Crude oil and natural gas prices eased to their pre-war levels, but metal prices remain firm. Globally, supply conditions have improved in recent months. The banking turmoil in the US and Europe and the accompanying financial stability concerns rattled global financial markets in March. Increased risk aversion triggered flight to safety and the expectations of an early reversal of the monetary tightening cycle led to a sharp decline in sovereign bond yields across maturities, correction in equity prices and jump in market volatility indicators. The US dollar has retreated unevenly from its September 2022 highs. Domestic economic activity exhibited resilience in H2:2022-23. The National Statistical Office’s (NSO's) second advance estimates placed real gross domestic product (GDP) growth at 7.0 per cent for 2022-23, driven by private consumption and investment. Real GDP growth in Q3 was 4.4 per cent (year-on-year, y-o-y), boosted by investment demand while private consumption slowed. On the supply side, activity was supported by agriculture and services sectors, while manufacturing was restrained under the pressure of high input costs. Consumer price index (CPI) inflation persisted at elevated levels during 2022-23, impacted by a series of adverse supply shocks and the continuing pass-through of high input costs. Briefly edging into the tolerance band during November-December with the stronger than usual seasonal correction in food prices, it surged again to 6.4 per cent (y-o-y) in February as food inflation rose. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) increased the policy repo rate by 250 basis points (bps) during May 2022-February 2023 and monetary policy remains focussed on progressively aligning inflation with the target, while supporting growth. Monetary Policy Committee: September 2022-March 2023 When the MPC met in September 2022, CPI headline inflation was at 7.0 per cent in August. Domestic economic activity was gaining traction ahead of the festival season with double digit GDP growth in Q1:2022-23. CPI headline inflation was projected to remain above the upper tolerance level of 6 per cent through the first three quarters of 2022-231. The MPC felt that further calibrated monetary policy action was necessary to keep inflation expectations anchored, restrain the broadening of price pressures and pre-empt second round effects. Accordingly, the MPC raised the policy repo rate by 50 bps to 5.9 per cent with a 5-1 vote. One member voted for a smaller increase of 35 bps. The MPC also decided by a majority of 5-1 to remain focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. At the time of its December 2022 meeting2, the MPC noted that the CPI inflation print in October was persisting above the tolerance band. Real GDP registered a growth of 6.3 per cent (y-o-y) in Q2:2022-23. The MPC observed that while headline inflation was likely to moderate in H1:2023-24, it would still be well above the target. Economic activity had held up well and was expected to remain resilient. The impact of monetary policy measures undertaken needed to be monitored carefully. Against this backdrop, the MPC increased the policy repo rate by 35 bps to 6.25 per cent with a 5-1 vote and continued with its stance of withdrawal of accommodation on a 4 to 2 majority vote. In the run up to the February 2023 meeting, CPI headline inflation had eased to 5.7 per cent in December 2022, driven by strong deflation in vegetable prices even as inflationary pressures became accentuated across other food items and in the core category. Domestic economic activity was expected to be sustained by the focus on capital and infrastructure spending in the Union Budget 2023-24. Looking beyond the transitory respite in inflation due to the fall in vegetable prices, the MPC regarded inflation as a major risk to the outlook and observed that further calibrated monetary policy action was warranted to keep inflation expectations anchored, break core inflation persistence and thereby strengthen medium-term growth prospects. Accordingly, the MPC increased the policy repo rate by 25 bps to 6.50 per cent and committed to continue withdrawal of accommodation with a 4-2 vote for both the rate action and the stance decision. The MPC’s voting pattern reflects the diversity in individual members’ assessments, expectations and policy preferences, a characteristic also reflected in voting patterns of other central banks (Table I.1). Macroeconomic Outlook Chapters II and III analyse macroeconomic developments related to inflation and economic activity during H2:2022-23 (October 2022-March 2023). The evolution of key macroeconomic and financial variables over the past six months warrants revisions in the baseline assumptions (Table I.2). First, international crude prices eased in H2 on slowing global growth and a milder than expected winter in Europe. Geopolitical tensions and output curtailment by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries plus (OPEC plus) impart significant uncertainty to the outlook (Chart I.1.a & Chart I.1.b). Global petrol and diesel prices, which are the key determinant of domestic product prices, are elevated in view of demand-supply refinery mismatches (Chart I.1.c). Taking into account these developments, crude prices (Indian basket) are assumed at US$ 85 per barrel in the baseline as compared with US$ 105 in the September MPR baseline. Second, the nominal exchange rate of the Indian rupee or INR moved in a range of INR 81-83 per US dollar (USD) in H2. The INR was supported by a correction in the US dollar while risk-off sentiments towards emerging market economies (EME) assets and a widening current account deficit exerted downward pressures on the currency. Taking these developments into consideration, the exchange rate is assumed at INR 82 per US dollar in the baseline as against INR 80 in the September 2022 MPR.   Third, while global economic prospects have improved modestly compared to a few months ago, the outlook is highly uncertain. The global composite purchasing managers index (PMI) moved into expansion mode in February after remaining in the contraction territory for six consecutive months during July 2022 - January 2023. According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) January 2023 update of the World Economic Outlook (WEO), global growth is expected to moderate from 3.4 per cent in 2022 to 2.9 per cent in 2023, and 3.1 per cent in 2024, with a sharper deceleration projected for advanced economies (AEs) relative to emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) (Chart I.2). Alongside, global trade is expected to decelerate in 2023. Adverse supply shocks and the pass-through of inputs costs to output prices imparted sustained upward pressures on CPI inflation in H2 (Chapter II). Looking ahead, the three months ahead and the one year ahead median inflation expectations of urban households fell by 30 bps each in the March 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey3. The proportion of respondents expecting the general price level to increase by more than the current rate decreased for both the horizons vis-à-vis the previous round (Chart I.3).  Manufacturing firms polled in the January-March 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey expected the pace of increase in cost of raw materials to remain steady and in selling prices to moderate in Q1:2023-24 (Chart I.4a).4 Services sector and infrastructure firms expected modest softening in the growth of input cost and selling prices in Q1:2023-24 (Charts I.4b and I.4c).5 In the PMI surveys, manufacturing and services firms reported lower input cost inflation but higher output price inflation in March compared to February 2023.  Professional forecasters surveyed by the Reserve Bank in March 2023 expected CPI inflation to moderate from 6.2 per cent in Q4:2022-23 to 5.0 per cent in Q1:2023-24, 5.3 per cent in Q2, 5.5 per cent in Q3 and 5.2 per cent in Q4 (Chart I.5a and Table I.3).6 The respondents expected CPI inflation excluding food and beverages, pan, tobacco and intoxicants, and fuel and light to move from 6.2 per cent in Q4:2022-23 to 5.4-5.6 per cent during 2023-24. Their 5- and 10-years ahead inflation expectations remained unchanged at 5.0 per cent and 4.5 per cent, respectively, in the March round (Chart I.5b).  Looking ahead, the inflation outlook will be conditioned by several factors, both global and domestic. While crude oil and commodity prices have corrected in recent months, their future trajectories remain uncertain, given the lingering geopolitical hostilities and likely demand rebound from countries reopening from pandemic-related lockdowns. Global financial markets are exhibiting volatility. Domestically, the expectations of a bumper rabi harvest augur well for the future trajectory of food inflation. On the other hand, adverse weather shocks are becoming more frequent and there is heightened uncertainty about the south-west monsoon rains. Taking into account the initial conditions, signals from forward-looking surveys and estimates from structural and other time-series models7, CPI inflation is projected to average 5.2 per cent in 2023-24 – 5.1 per cent in Q1:2023-24, 5.4 per cent in Q2 and Q3, and 5.2 per cent in Q4, with risks evenly balanced (Chart I.6). The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for headline inflation in Q4:2023-24 are 3.8-6.6 per cent and 3.1-7.3 per cent, respectively. For 2024-25, assuming a normal monsoon, a progressive normalisation of supply chains, and no further exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate that inflation will average 4.5 per cent. In Q4:2024-25, CPI inflation is projected at 4.4 per cent, with the 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals at 3.0-5.8 per cent and 2.2-6.5 per cent, respectively.  The baseline forecasts are subject to several upside and downside risks, given the volatile global environment and the cross-country experience with large deviations of inflation from forecasts (Box I.1). Upside risks emanate from possible escalation of geopolitical conflicts, higher global crude and commodity prices, accentuation of global financial market volatility amidst high inflation and financial stability concerns, renewed supply chain disruptions, extreme weather conditions and deficient monsoon, and a larger pass-through of input cost pressures to output prices as demand strengthens. Downside risks could stem from an early resolution of geopolitical tensions, correction in global crude and commodity prices due to slowing global demand, and further improvement in supply conditions.

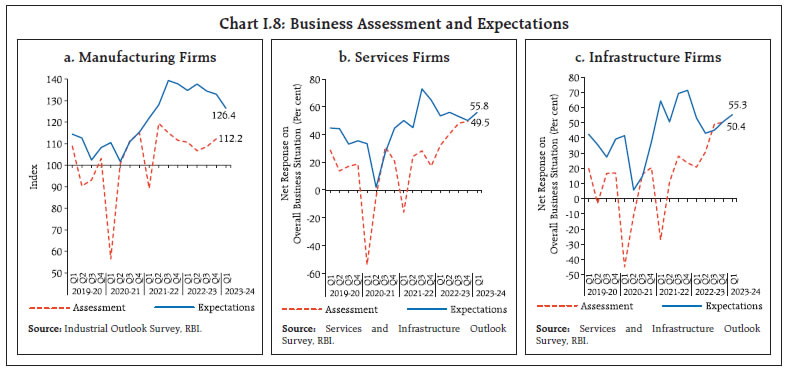

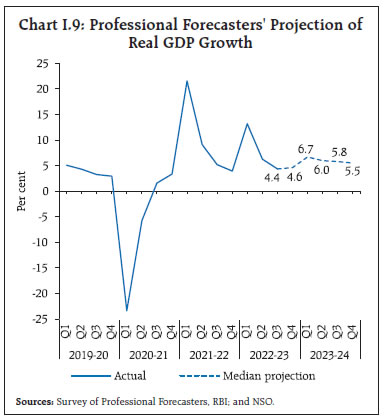

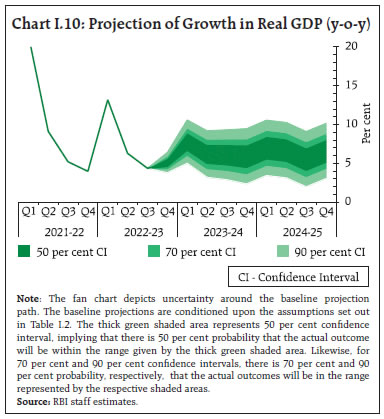

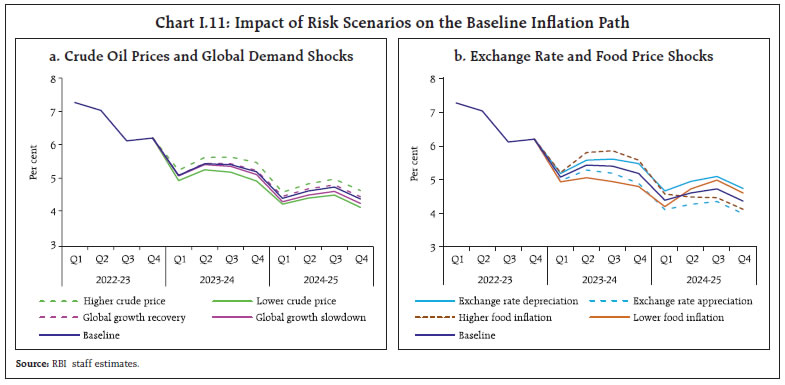

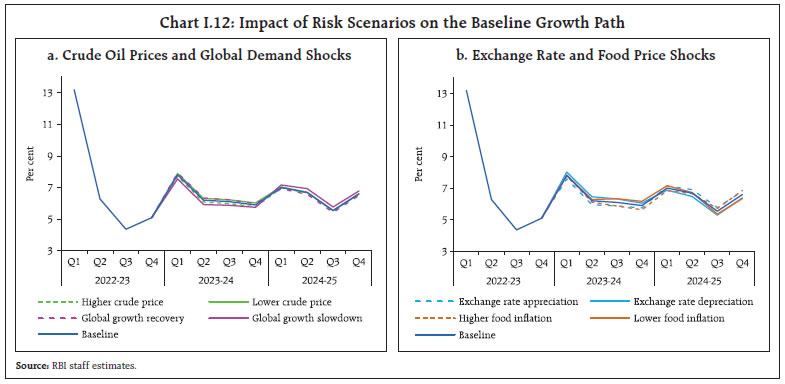

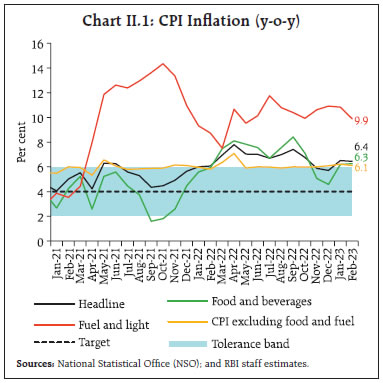

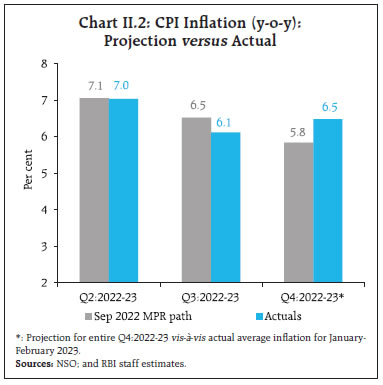

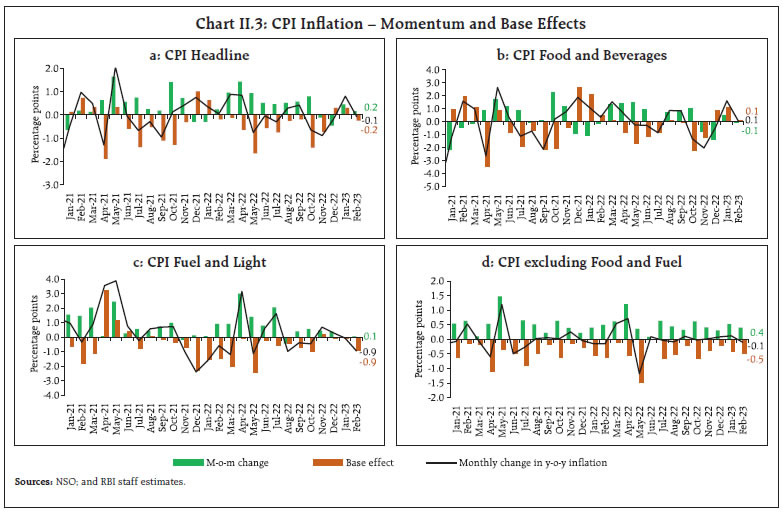

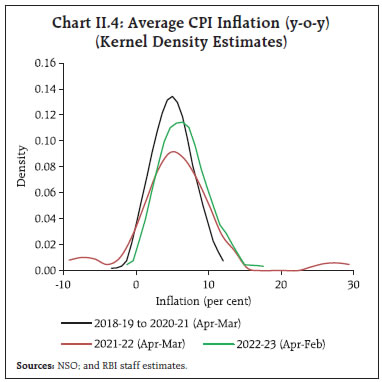

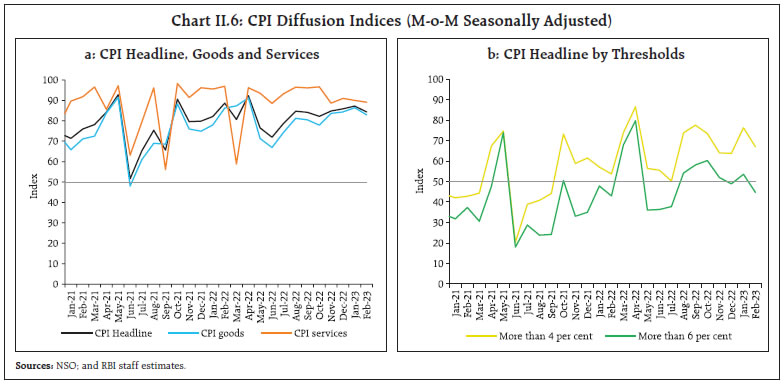

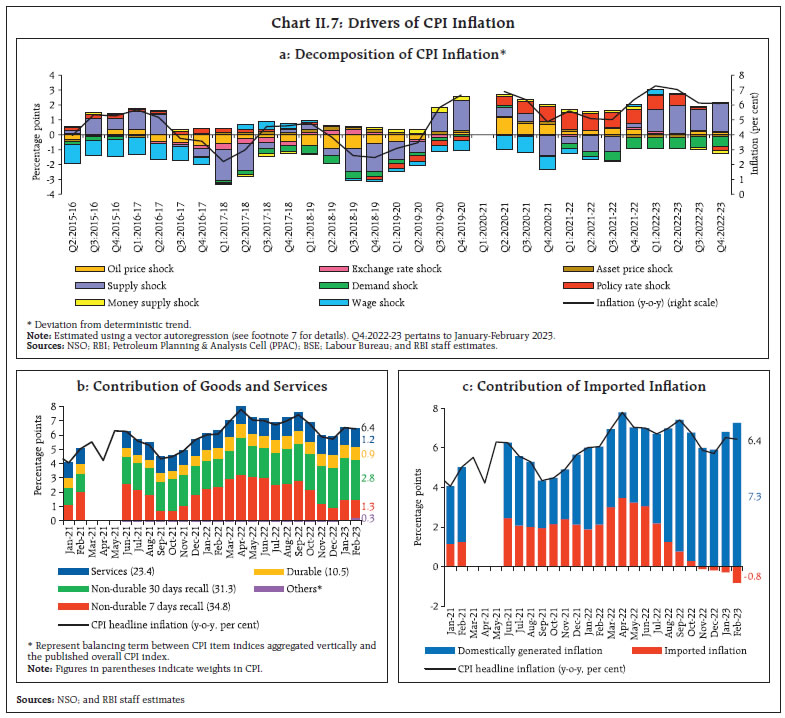

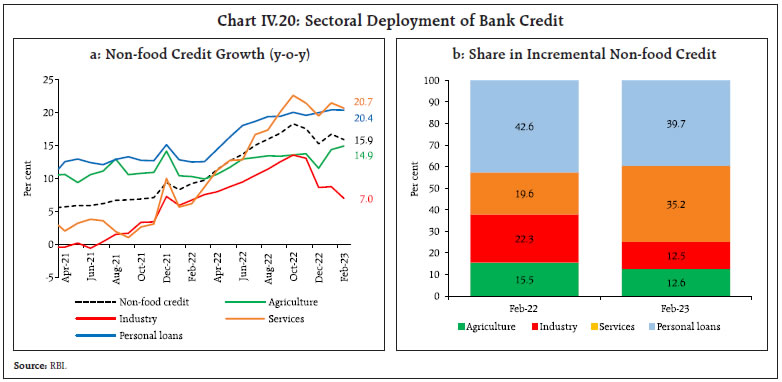

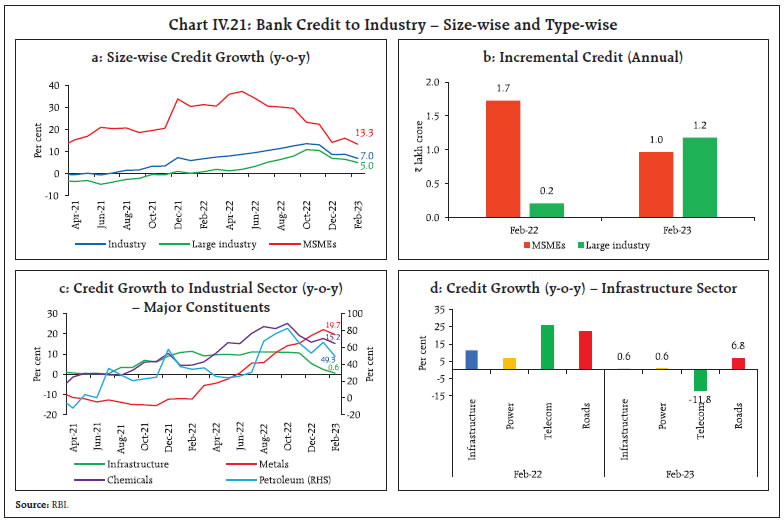

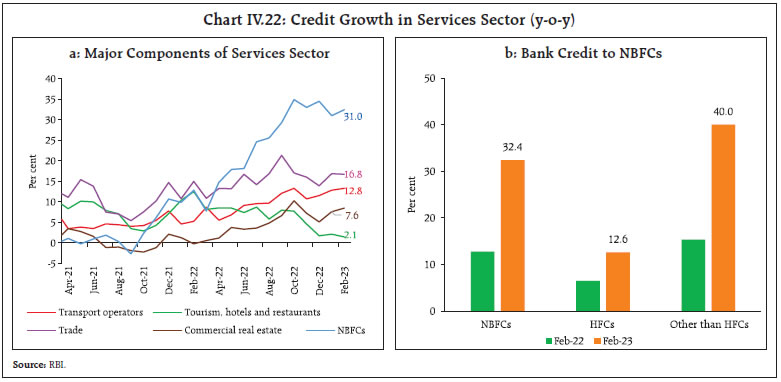

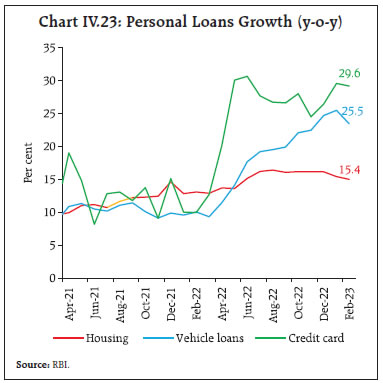

Domestic economic activity remains resilient, on the back of consecutive years of strong agricultural production, a post-pandemic rebound in contact-intensive services, buoyant growth in bank credit, a healthy banking and financial system10 and the government’s capex push. Slowing global growth, geopolitical tensions, upsurge in financial market volatility and tightening global financial conditions, however, weigh heavily on the outlook. Turning to the key messages from forward-looking surveys, consumer confidence (the current situation index) improved in the March 2023 survey round vis-à-vis the previous round on account of improved perceptions on general economic situation, employment and household income, though it remains in the pessimistic zone. Consumers’ expectations for the year ahead continued in the optimistic territory, albeit with some moderation (Chart I.7).11 The optimism of firms in the manufacturing sector ebbed for the quarter ahead relative to the previous round in the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey (Chart I.8a). The expectations of services and infrastructure sector companies, on the other hand, improved in terms of the overall business situation (Charts I.8b and I.8c).   Recent surveys by other agencies indicate a mixed picture on business expectations relative to the previous round (Table I.4). Manufacturing and services firms in the PMI surveys for March 2023 exhibited optimism for the year ahead. Professional forecasters polled in the March 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey expected real GDP growth at 4.6 per cent in Q4:2022-23, 6.7-6.0 per cent in H1:2023-24, and 5.8-5.5 per cent in H2 (Chart I.9 and Table I.3). Taking into account the baseline assumptions, survey indicators and model forecasts, real GDP growth is expected at 6.5 per cent in 2023-24 – 7.8 per cent in Q1; 6.2 per cent in Q2; 6.1 per cent in Q3; and 5.9 per cent in Q4 – with risks evenly balanced around this baseline path (Chart I.10 and Table I.3). For 2024-25, assuming a normal monsoon and no major exogenous or policy shocks, the structural model estimates indicate real GDP growth at 6.5 per cent, with quarterly growth rates in the range of 5.5-7.0 per cent.  There are upside and downside risks to this baseline growth path. The upside risks emanate from a stronger-than-expected rebound in the contact-intensive services as they emerge more fully from the pandemic; a restart of private investment activity boosted by the government’s capex push, given healthier corporate balance sheets; a favourable terms of trade shock in the case of a sharper-than-anticipated correction in crude and commodity prices; a better-than-expected global growth prospects; and an early resolution of geopolitical conflicts. On the contrary, an escalation in geopolitical tensions, a further hardening of international crude oil and other commodity prices, sustained disruptions to supply chains, persistence of global financial market volatility, a sharper loss of momentum in global trade and demand and weather-related disruptions pose downside risks to the baseline growth path.  The baseline projections of growth and inflation in this chapter are inter alia conditional on assumptions of the future trajectory of key domestic and international macroeconomic variables set out in Table I.2. The uncertainties surrounding these assumptions have increased significantly due to protracted geopolitical tensions, upside inflation surprises globally, international financial market volatility and recurrent adverse weather events. Against this backdrop, this section explores plausible alternative scenarios to assess the balance of risks around the baseline projections. (i) Global Growth Uncertainties Global growth is slowing with significant downside risks to the baseline outlook. Globally, inflation remains the key concern and more monetary tightening may be warranted to quell it. This could, however, push global interest rates higher for longer than currently anticipated. Debt servicing costs could escalate and add to financial stability risks. Moreover, geopolitical tensions could ratchet up further. In such a scenario, if global growth is 100 bps lower than the baseline, domestic growth and inflation could be around 30 bps and 15 bps, respectively, below the baseline trajectories. Conversely, if inflation in major economies retreats quickly and global financial conditions ease, geopolitical tensions ebb and global growth surprises on the upside by turning out to be higher by 50 bps, domestic growth and inflation could edge higher by around 15 bps and 7 bps, respectively (Charts I.11a and I.12a).  (ii) International Crude Oil Prices International crude oil prices have eased since the last MPR but remain volatile. A stronger rebound in global demand, production cuts by OPEC plus countries and the escalation of geopolitical hostilities could push crude oil prices higher. Crack spreads could widen further, given global demand-supply mismatches. Assuming international crude oil prices to be 10 per cent above the baseline, domestic inflation and growth could be higher by 30 bps and weaker by around 15 bps, respectively. Conversely, an early de-escalation of geopolitical tensions and subdued global demand owing to aggressive monetary policy action may lead to a moderation in global crude oil prices below the baseline. If, as a result, the Indian basket of crude prices falls by 10 per cent and assuming full pass-through to domestic product prices, inflation could ease by around 30 bps with a boost of 15 bps to growth (Charts I.11a and I.12a). (iii) Exchange Rate The INR depreciated relative to the US$ in H2:2022-23 amidst tightening global financial conditions, an uncertain global environment and portfolio outflows. The ‘higher for longer’ interest rate scenario and slowing global growth could keep risk aversion elevated and impinge upon capital flows to EMEs. Should the INR depreciate by 5 per cent below the baseline in such a scenario, inflation could edge up by around 35 bps while GDP growth could be higher by around 25 bps through the stimulus to exports. On the other hand, as India’s growth performance and outlook is relatively better than peers, it could become attractive for foreign investors. Furthermore, with the current account deficit narrowing, the INR could appreciate relative to the baseline. With five per cent appreciation, inflation and GDP growth could moderate by around 35 bps and 25 bps, respectively (Charts I.11b and I.12b).  (iv) Food Inflation Heat waves, large unseasonal rains, and deviations of the monsoon from its normal pattern are occurring with greater frequency and intensity. Such adverse weather events could lead to upward pressures on food prices which could raise headline inflation by around 50 bps (Charts I.11b and I.12b). On the other hand, the prospects of a bumper rabi harvest, adequate buffer stocks, effective supply management measures by the government, and an improving global food situation could exert downward pressures on food inflation and push headline inflation 50 bps below the baseline. The baseline headline inflation path and the balance of risk are strongly conditional on the evolving weather situation and the temporal and spatial spread of the south-west monsoon rainfall. The Indian economy is expected to be amongst the fastest growing major economies in 2023-24, backed by strong domestic drivers and strengthening macroeconomic fundamentals. The Indian financial sector remains stable. Headline inflation is expected to moderate from its prevailing elevated levels and move below the upper tolerance band during 2023-24. Monetary policy remains focused on progressively aligning inflation with the target. Geopolitical hostilities, stubborn global inflation, volatile global financial markets and climate shocks are the key risks to the growth and the inflation outlook. __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The GDP growth forecast was revised downward by 20 bps to 7.0 per cent (relative to the August 2022 projections) while the inflation forecast was retained at 6.7 per cent for 2022-23. The GDP growth forecast was revised to 6.8 per cent in the December 2022 meeting and the inflation forecast to 6.5 per cent in the February 2023 meeting of the MPC. 2 A separate meeting of the MPC was held on November 3, 2022 to discuss and draft the report to be sent to the Government by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) under the provisions of Section 45ZN of the RBI Act, 1934 and Regulation 7 of the RBI MPC and Monetary Policy Process Regulations, 2016, consequent to inflation exceeding 6 per cent, the upper tolerance threshold around the target, for three successive quarters – Q4:2021-22 (6.3 per cent), Q1:2022-23 (7.3 per cent) and Q2 (7.0 per cent). 3 The Reserve Bank’s inflation expectations survey of households is being conducted in 19 cities since March 2021 (18 cities in the previous rounds) and the results of the March 2023 round are based on responses from 6,075 households. 4 The results of the January-March 2023 round of the industrial outlook survey are based on responses from 1066 companies. 5 Based on 522 services companies and 116 infrastructure firms polled in the January-March 2023 round of the services and infrastructure outlook survey. 6 41 panellists participated in the March 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey of professional forecasters. 7 John, Joice, Deepak Kumar, Asish Thomas George, Pratik Mitra, Muneesh Kapur and Michael Debabrata Patra (2023), “A Recalibrated Quarterly Projection Model (QPM 2.0) for India”, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, February, Volume LXXVII(2), pp.59-77. 8 These central banks are: Reserve Bank of India, Banco Central de Brasil, South African Reserve Bank, European Central Bank, Czech National Bank, Sveriges Riksbank Sweden, Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve. 9 The unbiasedness of forecasts is evaluated by estimating the following equation: FEit=αi+β * PandemicDummy+εit, where FEit is the inflation forecast error at different horizons made by central banks and PandemicDummy captures the effect of the pandemic on the forecast error. 10 Das, Shaktikanta (2023), “G20 for a Better Global Economic Order during India’s Presidency”, 17th K P Hormis Commemorative Lecture, March 17, available at /en/web/rbi/-/speeches-interview/g20-for-a-better-global-economic-order-during-india-s-presidency-1356 11 The Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey is being conducted in 19 cities since March 2021 (13 cities in the previous rounds) and the results of the March 2023 round are based on responses from 6,075 respondents. The path of inflation in H2:2022-23 was buffeted by overlapping domestic food supply shocks which kept inflation above the upper tolerance band barring a transient softening in November-December 2022. Core inflation persisted at elevated levels in spite of input costs moderating with the softening in international commodity prices. Since the September 2022 MPR, the headline CPI inflation1 path has been impacted by domestic food supply shocks amidst weather vagaries and the pass-through of pent-up input costs. A transitory but more than anticipated seasonal correction in vegetable prices during November-December 2022 brought some relief but this reversed in January-February 2023 due to sustained price pressures from cereals and spices and a pick-up in protein-based food inflation. With improving domestic demand conditions, input costs were steadily passed on to retail prices of goods and services, imparting considerable stickiness to the already elevated core (CPI excluding food and fuel) inflation2. Reflecting these multiple shocks, headline inflation averaged 7.1 per cent (year-on-year, y-o-y) during September-October before a short-lived dip to 5.7 per cent by December. A resurgence of food price pressures pushed headline inflation to 6.5 per cent during January-February 2023. Core inflation hovered at or above 6 per cent throughout H2 (Chart II.1). The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and to explain the underlying reasons thereof. The September 2022 MPR had projected inflation at 6.5 per cent for Q3:2022-23 and 5.8 per cent for Q4. Actual inflation trailed the projection by 40 bps in Q3 mainly due to the sharper than expected seasonal correction in vegetables prices that also commenced earlier than usual - the month-on-month (m-o-m) decline in prices of CPI vegetables at (-) 8.3 per cent in November 2022 was the highest in the current CPI (2012=100) series for the month of November (Chart II.2). This was followed by an even larger decline in vegetable prices in December. In fact, the cumulative price decline of around 20 per cent in November-December turned out to be the highest in the current CPI series. In Q4 (January-February 2023), the situation reversed, with higher than anticipated cereal price inflation catapulting inflation by around 70 bps above projections. Forecast errors in Q4 were also attributable to the CPI aggregation methodology due to the redistribution of weights away from the freely distributed rice and wheat under the public distribution system (PDS) towards high market price cereal items3, and to the depreciation of the rupee vis-à-vis the US$ relative to the September 2022 MPR baseline assumption.   Headline inflation dynamics in H2 reflected the interplay of volatile food price momentum and base effects4. The acceleration in headline inflation to 7.4 per cent in September 2022, an increase of around 40 bps from August, came from a broad-based positive price momentum. In October, the headline inflation softened by around 60 bps to 6.8 per cent on account of strong favourable base effects across food, fuel and core categories, despite a further pick-up in the price momentum. Thereafter, headline CPI momentum registered a decline driven by lower food prices. This, along with favourable base effects, moderated headline inflation by close to 90 bps in November. A further sharp correction in headline momentum in December, despite an unfavourable base, led to a second consecutive month of softening in headline inflation. In January 2023, the positive price momentum in food and core categories and an adverse base effect pulled headline inflation up by 80 bps to 6.5 per cent. In February, the decline in food prices along with a favourable base effect led to a marginal softening in headline inflation to 6.4 per cent (Chart II.3). The distribution of CPI during 2022-23 revealed a pattern distinct from the previous year. The mean of the distribution rose to 6.8 per cent in 2022-23 (April-February) from 5.5 per cent during 2021-22 while lower standard deviation and a lower positive skew pointed towards the generalisation of inflation pressures in the CPI basket (Chart II.4 and II.5). The broad-basing of price pressures was also visible in CPI diffusion indices (DIs)5, which increased during September 2022 to January 2023, driven by CPI goods, with some moderation in February (Chart II.6a). The threshold DI6 for price increases remained in excess of 6 per cent on a seasonally adjusted annualised rate (saar) basis on an average during the last six months (Chart II.6b).     A historical decomposition of inflation using a vector autoregression (VAR)7 model indicates that supply shocks drove the inflation trajectory in H2, while monetary actions and aggregate demand conditions exerted downward pressure (Chart II.7a). An analysis of supply-side cost-push shocks suggests that while direct effects dominate in terms of their impact on headline CPI, indirect effects can also be significant (Box II.1).

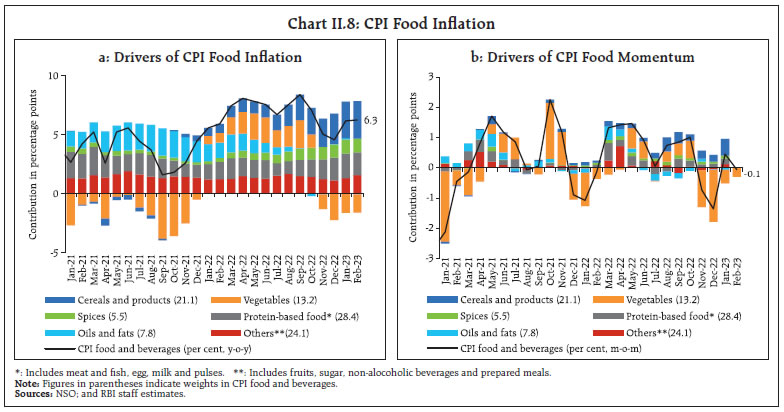

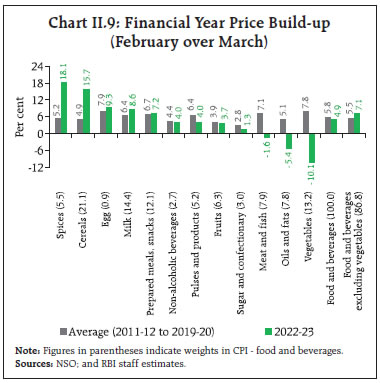

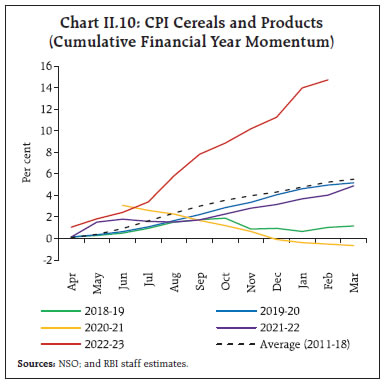

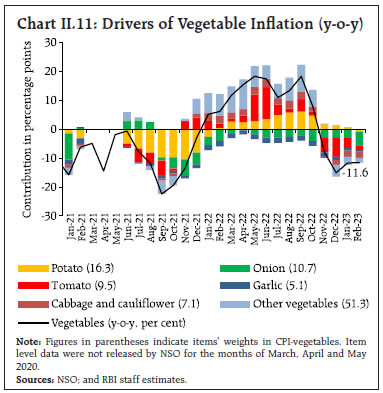

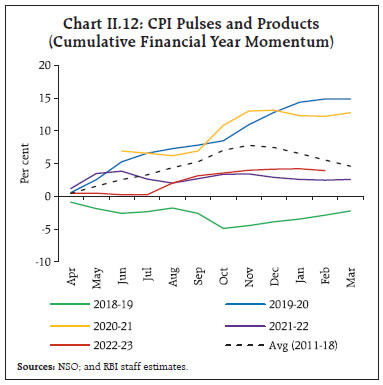

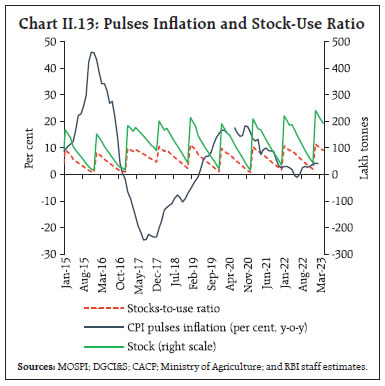

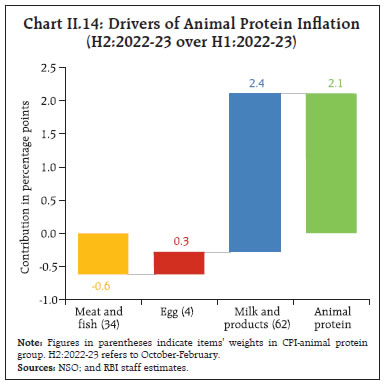

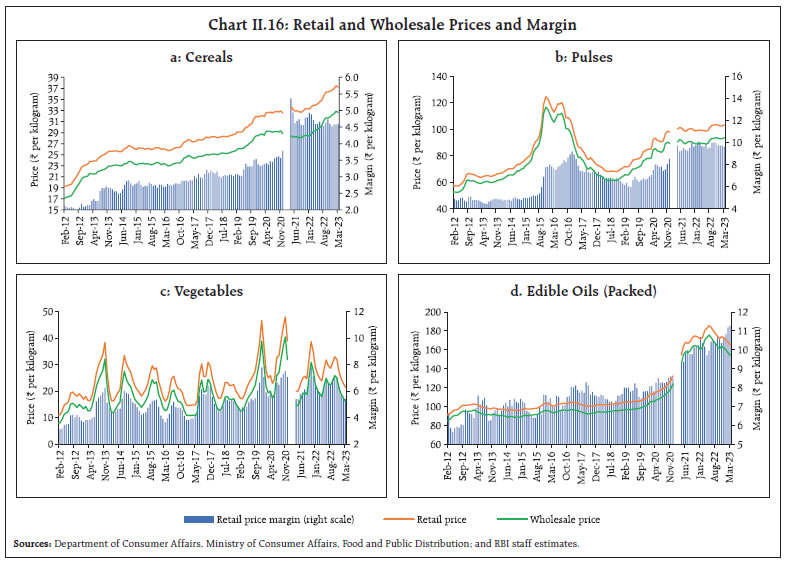

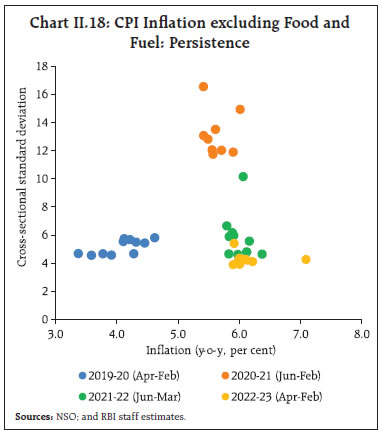

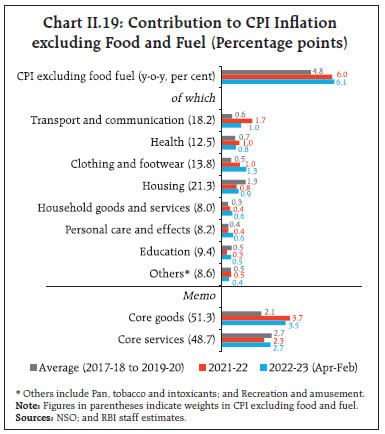

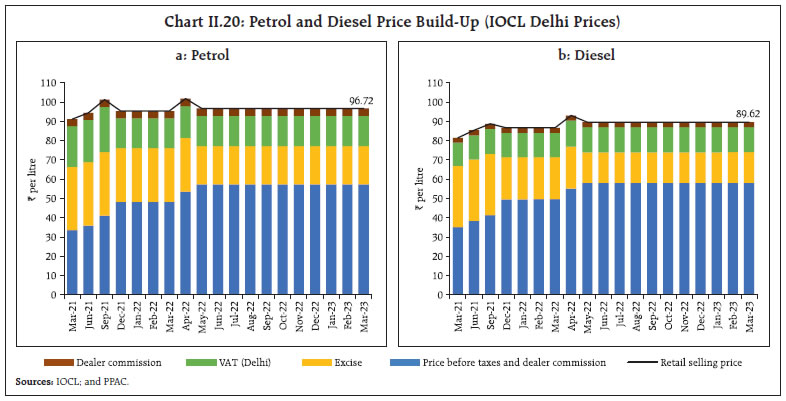

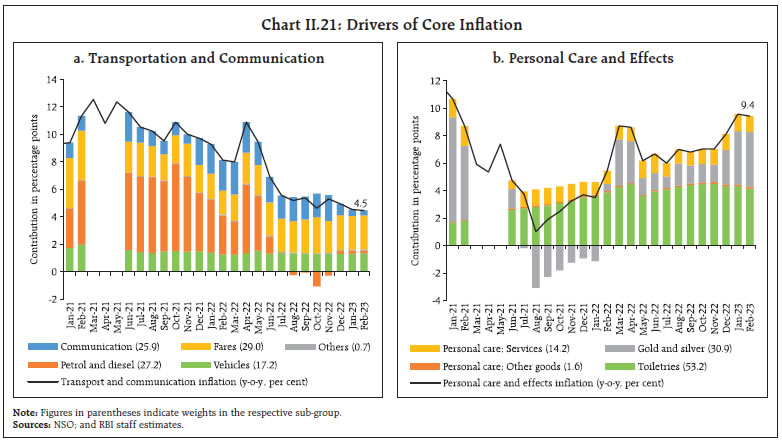

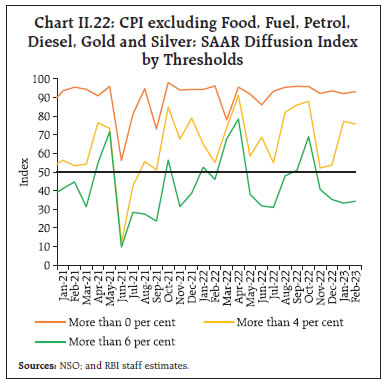

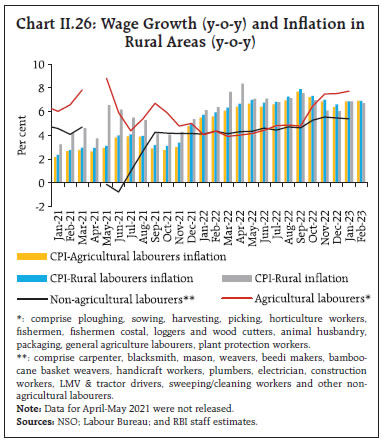

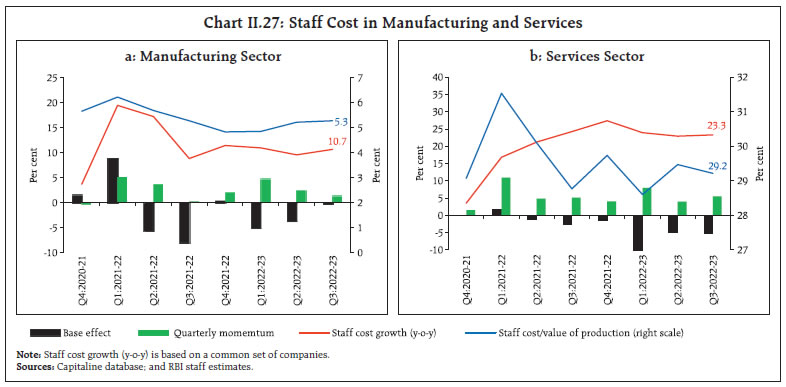

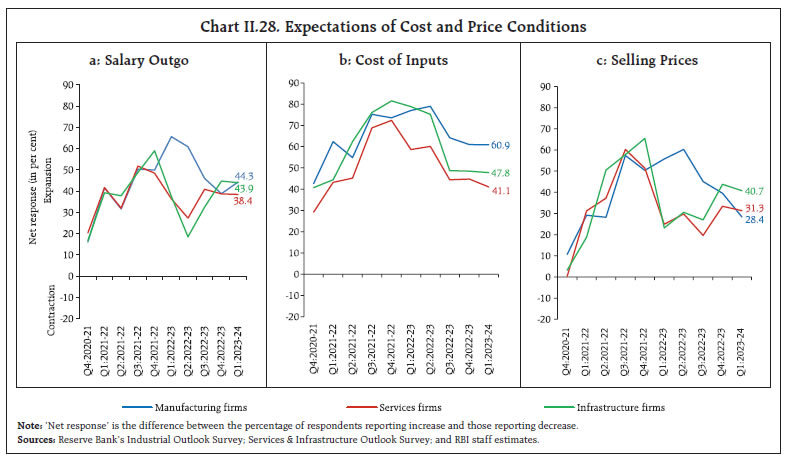

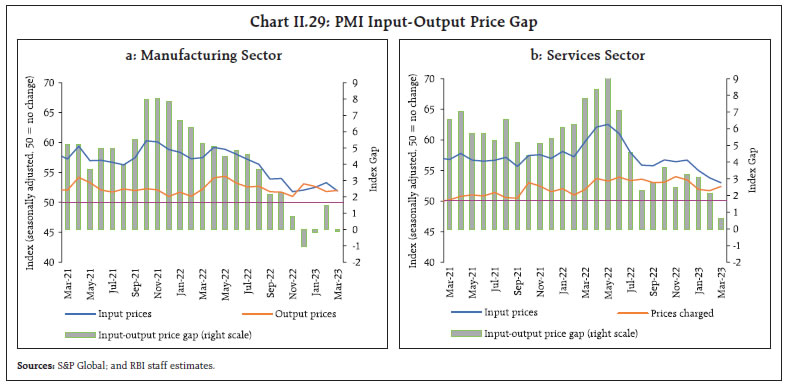

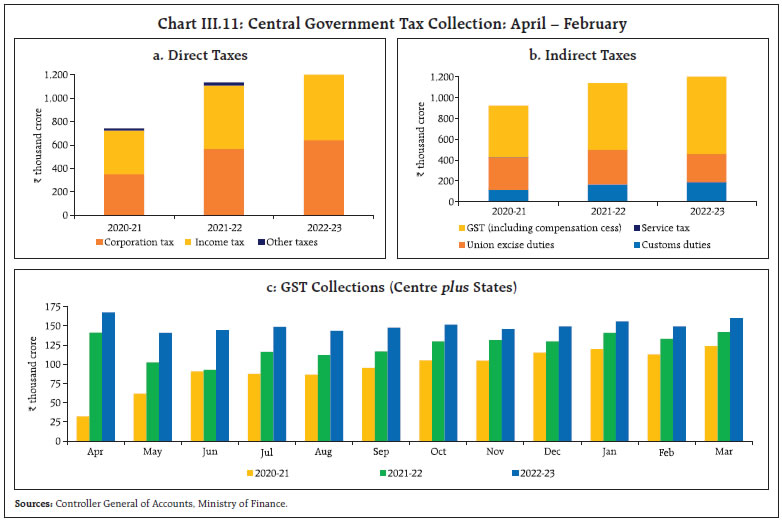

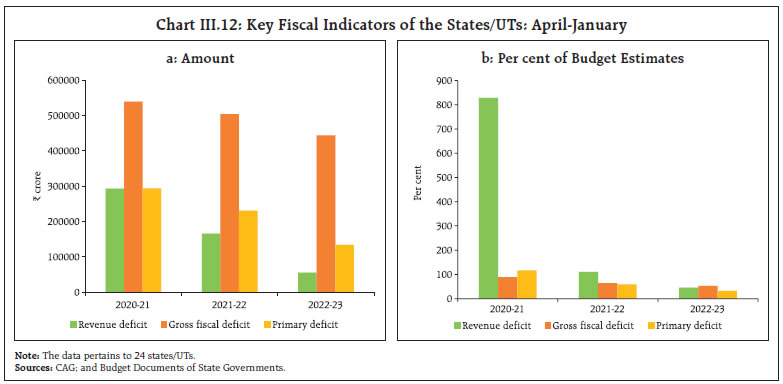

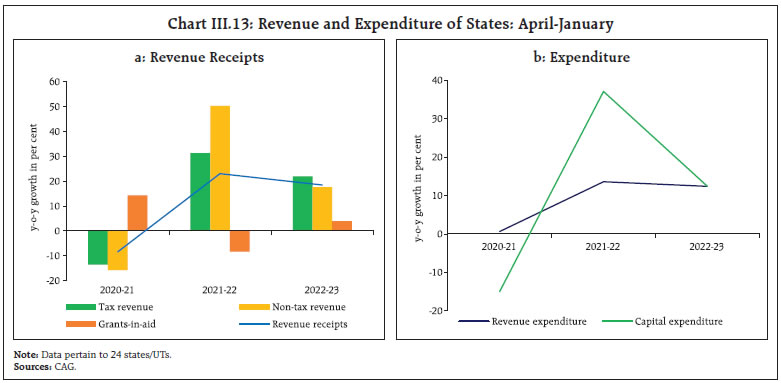

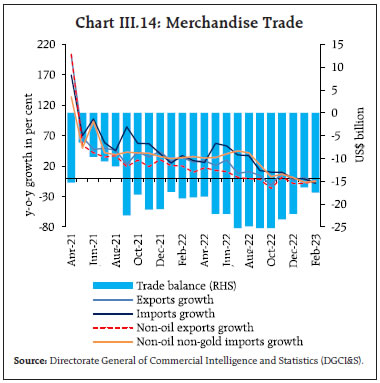

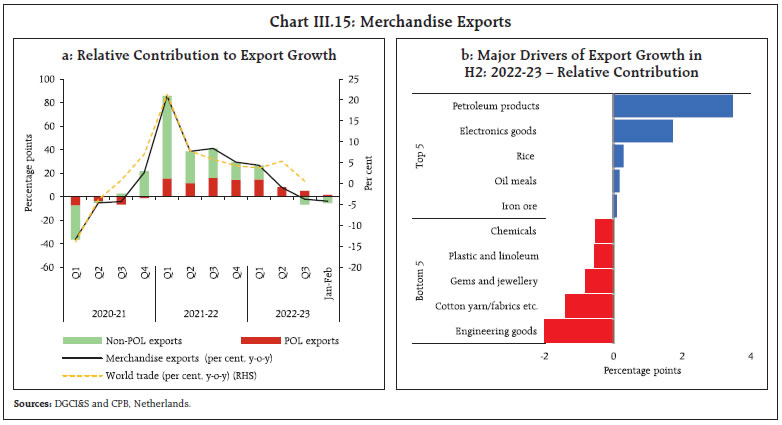

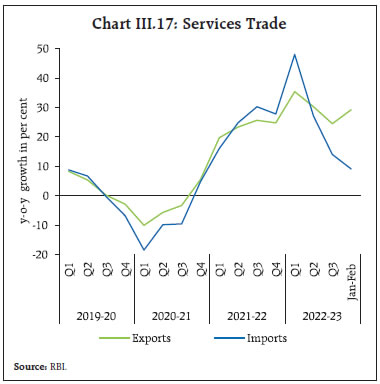

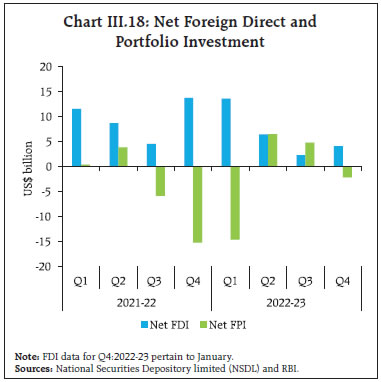

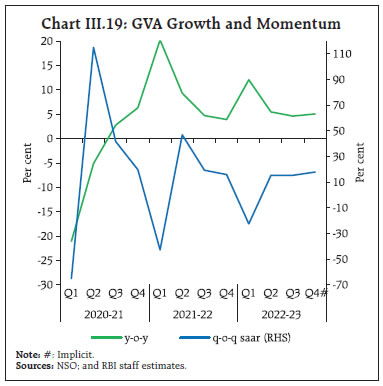

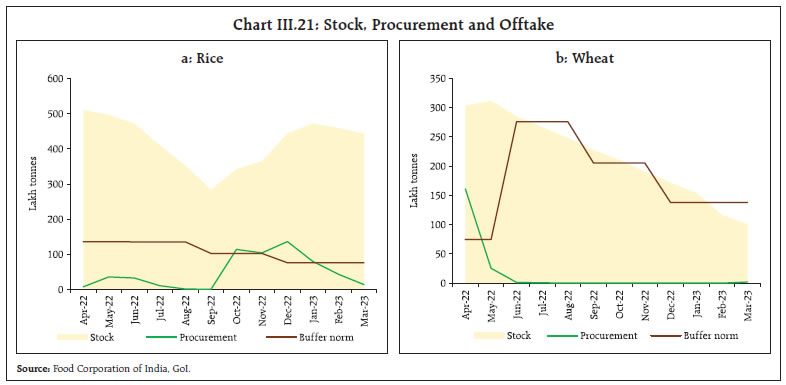

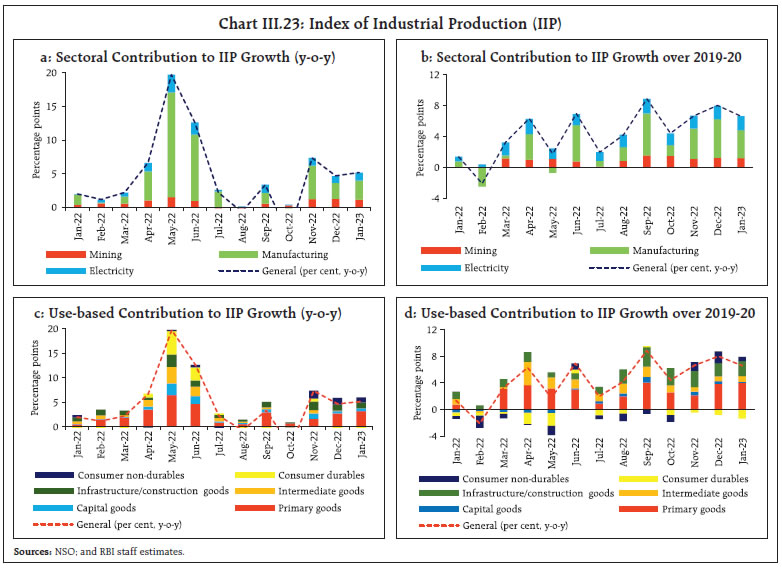

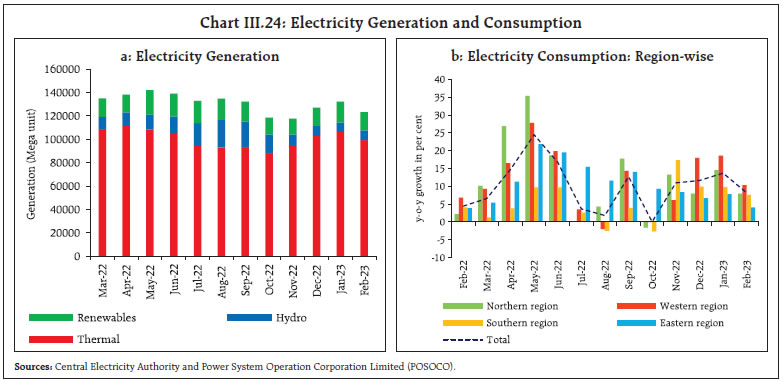

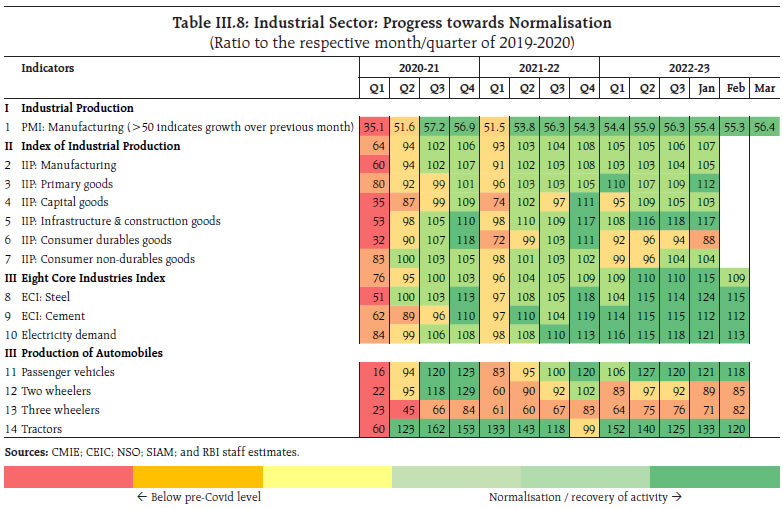

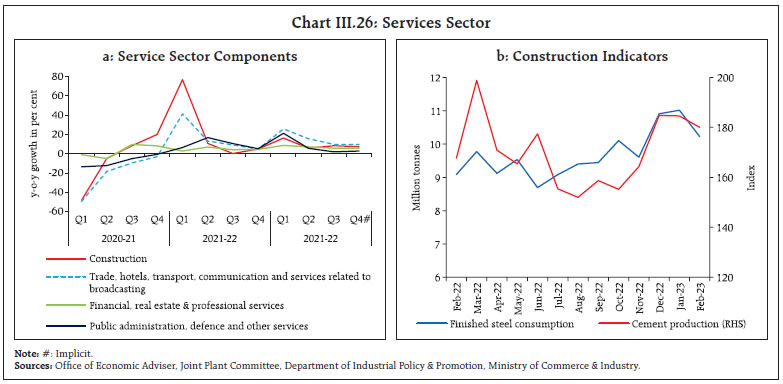

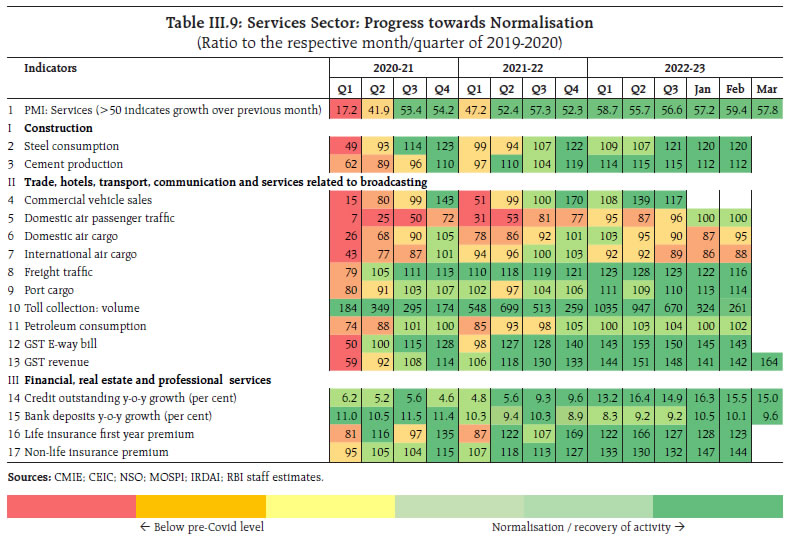

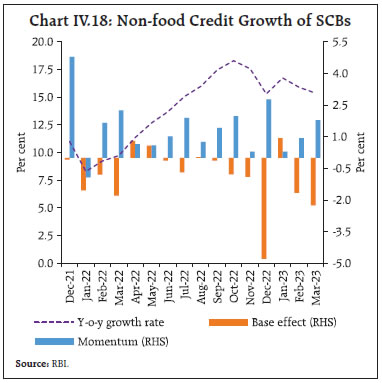

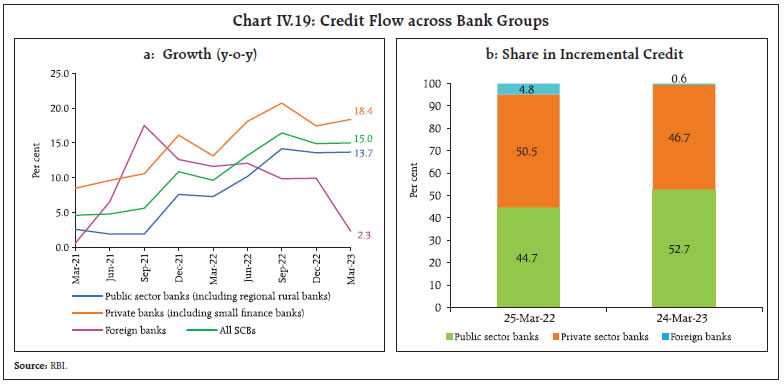

The contribution of goods (with a weight of 76.6 per cent in overall CPI) to headline inflation averaged 81 per cent during September 2022-February 2023 while that of services (weight of 23.4 per cent) averaged 19 per cent. (Chart II.7b). Within goods, semi-perishable goods (non-durable goods with a 30-day recall9), particularly petroleum products (like kerosene, LPG and firewood and chips) and cereals, personal care items and medicines as well as durables (goods with a 365-day recall) like clothing and footwear items, motor cycle/scooter and gold were the main drivers. The contribution of perishable goods to overall inflation halved to 19 per cent in February 2023 from 38 per cent in September 2022. The increase in global commodity prices following the Ukraine conflict contributed to a surge in the contribution of imported components10 during March-June 2022. Subsequently, with the decline in international commodity prices, the contribution of imported inflation moderated – it turned negative during November 2022-February 2023, driven down by the y-o-y fall in in prices of edible oils, LPG, electronic goods parts, polymer, petrol and diesel (Chart II.7c).  CPI Food Group Inflation in food and beverages (weight of 45.9 per cent in the CPI basket) moderated from 8.4 per cent in September 2022 to 4.6 per cent in December, on the back of sharp correction in vegetable prices alluded to earlier. It, however, rose again to 6.3 per cent by February 2023, as increases in prices of cereals and products, milk and spices outweighed the seasonal easing in vegetables prices. Lower rabi production of wheat and spices, lower kharif production of rice, higher fodder and feed costs, and a decline in wheat buffer stocks led to the hardening of prices of cereals, milk and spices (Chart II.8). Excluding vegetables, CPI food inflation rose from 7.0 per cent during September-October 2022 to 9.0 per cent in February.  While the overall food price build-up in 2022-23 was lower than the historical experience, the build-ups in respect of five of the twelve sub-groups – cereals; eggs; spices; milk; and prepared meals – were higher than their long-term averages (Chart II.9). Inflation in cereals (weight of 9.7 per cent in the CPI and 21.1 per cent in the food and beverages group) increased from less than 10 per cent in August 2022 to 16.7 per cent in February 2023, the highest in the current CPI series (Chart II.10). Wheat and rice were the primary drivers, recording double digit inflation since June and October 2022, respectively. Wheat prices hardened on the back of lower domestic production [(-) 1.7 per cent in 2021-22] due to the heat wave in major wheat producing states, the dip in stocks and elevated global prices due to the conflict in Ukraine. The release of a cumulative 3.4 million tonnes of wheat in the open market by the Government, at a lower reserve price, along with the higher estimated rabi production in 2022-23 (an increase of 4.1 per cent), has led to a gradual ebbing of price pressures. The Government continued with restrictions on wheat exports since May 2022 and banning of exports of wheat flour from August 25, 2022 to improve domestic supplies and ease price pressures. Inflation in rice remained elevated due to decline in kharif production ((-) 2.6 per cent) in 2022-23. Further, exports also registered higher volumes (6.5 per cent y-o-y during April 2022-January 2023).   Inflation in vegetables prices (weight of 6.0 per cent in the CPI and 13.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) remained volatile during 2022-23. It moderated from a high of 18.2 per cent in September 2022 and entered into deflation in November on the back of an early onset of seasonal easing of price pressures, reaching (-)11.6 per cent in February 2023. Onion prices remained in deflation throughout 2022-23 on account of higher production in 2021-22 (an increase of 17.4 per cent), record procurement (buffer stock of 2.5 lakh metric tonnes in 2022-23) and better rabi crop prospects. Potato price inflation, however, generally remained high during the year on lower production in 2021-22 ((-) 5.0 per cent). With stock releases from cold storages and arrivals of the kharif crop, prices declined from November 2022 as per the seasonal pattern, leading inflation to turn negative in February 2023. Imports of potatoes from Bhutan till June 2023, without the need for any import license, also reined in price pressures. Tomato prices exhibited high volatility due to a setback to production from heat wave in major producing states, cyclone Asani in Andhra Pradesh and excess/unseasonal rains. Prices fell from November as per the seasonal pattern and on expectations of good production owing to increased sown area (Chart II.11).  Inflation in prices of fruits (weight of 2.9 per cent in the CPI and 6.3 per cent within the food and beverages group) was relatively subdued, averaging 4.5 per cent in 2022-23 (April-February). While prices of apples and coconuts (barring February) recorded deflation throughout, inflation in banana, oranges, papaya and other fresh fruits remained elevated. Inflation in prices of pulses (weight of 2.4 per cent in the CPI and 5.2 per cent in the food and beverages group), the primary source of plant-based protein, rose from 2.6 per cent in August 2022 to 4.1 per cent in February, driven by tur and urad on a decline in kharif production in 2022-23 (by 13.1 per cent and 1.0 per cent, respectively) (Chart II.12). To augment supplies and contain price pressures, the Government extended the period for free import of tur and urad to March 2024, increased the procurement ceiling under the Price Support Scheme (PSS) from 25 per cent to 40 per cent for tur, urad and masoor and allowed disposal of chana to states at a discounted price under the PSS. Government has stepped up monitoring of stock disclosures and futures trading in chana has been banned.  On the whole, record pulses production during 2022-23 at 278 lakh tonnes and a higher stock-to-use (STU) ratio augur well for domestic availability and effective price management (Chart II.13). Inflation in animal-based protein items increased sharply in H2:2022-23 (October-February), driven mainly by milk and products (weight of 6.6 per cent in the CPI and 14.4 per cent within the food and beverages group) (Chart II.14). Major milk co-operatives like Amul and Mother Dairy raised retail prices by ₹2-3 per litre in two and three spells since September 2022, respectively, followed by other state cooperatives, attributed to increase in feedstock costs. Inflation in prices of eggs increased during November 2022-January 2023 due to high feed cost and a spurt in exports to Malaysia before easing to 4.3 per cent in February 2023. After remaining muted during July-November 2022, inflation in meat and fish (weight of 3.6 per cent in CPI and 7.9 per cent within the food and beverages group) increased to 6.0 per cent in January 2023 before moderating sharply in February 2023 due to a correction in prices as well as a favourable base effect.    Inflation in prices of oils and fats (weight of 3.6 per cent in the CPI and 7.8 per cent within the food and beverages group), which was elevated in the initial months of 2022-23 due to increase in global prices in the aftermath of the conflict in Ukraine and an export ban on palm oil by Indonesia, eased considerably to (-)0.5 per cent in February 2023 (Chart II.15). This moderation was supported by easing global prices, supply-side measures by the Government (extension of reduction in basic customs duty on crude and refined oils and imposition of stock limits on edible oil and oil seeds) and higher estimated domestic production of oilseeds in 2022-23 (5.4 per cent). Inflation in prices of sugar and confectionery (weight of 1.4 per cent in the CPI and 3.0 per cent in the food and beverages group) moderated sharply in September 2022 and remained muted in the subsequent months on the back of higher domestic production and export restrictions on sugar, effective from June 1, 2022 which was extended till October 2023 to ensure ample domestic supplies. Among other food items, inflation in prices of spices averaged 16.0 per cent during April 2022-February 2023, reflecting production shortfalls in key spices, especially dry chillies, cumin and coriander in 2021-22. Prepared meals prices rose due to the gradual pass-through of past increases in input costs from edible oils, LPG and transport costs. Retail Margins Retail price margins – the difference of retail and wholesale prices11 – for cereals and pulses remained elevated during 2022-23. Retail margins rose for edible oils as decline in retail prices (groundnut, soyabean, sunflower and mustard oil) was less than that in wholesale prices. Margins picked up in September-November 2022 in the case of vegetables, driven by all the three constituents, i.e., potatoes, tomatoes and onions. Subsequently, there was a sharp seasonal correction in prices and margins (Chart II.16). CPI Fuel Group CPI fuel inflation during September 2022 to February 2023 was high and sticky in a range of 9.9 per cent to 10.9 per cent. While domestic LPG prices remained unchanged till February 2023, kerosene (PDS) prices fell after July 2022 in line with international prices. Kerosene prices inflation moderated from around 60 per cent in September 2022 to 30 per cent by February 2023. Electricity prices, on the other hand, moved out of deflation in November 2022 and have remained largely steady since then. Firewood and chips inflation pressures rose during Q3 before moderating in February (Chart II.17).  Core CPI (CPI excluding Food and Fuel) Core inflation (CPI inflation excluding food and fuel) exhibited stickiness at or above 6 per cent in H2. Elevated inflation pressures were visible across all exclusion-based measures of core inflation (Table II.1). In 2020-21, high core inflation was due to price pressures in select categories like transport and communication, and personal care and effects. Since 2021-22, however, it has become increasingly generalised and persistent (Chart II.18). During 2022-23 (April-February), core inflation averaged 6.1 per cent vis-à-vis 6.0 per cent in 2021-22. Between 2021-22 and 2022-23, the contribution of transport and communication, and health to overall core inflation saw a decline, but that of clothing and footwear edged up sharply along with an uptick in the contributions of household goods and services, personal care and effects, and education. The contribution of core services increased during 2022-23 while that of core goods fell (Chart II.19).  Retail selling prices of petrol and diesel remained unchanged during September 2022 to February 2023 (Chart II.20). Petrol and diesel prices moved into deflation on a y-o-y basis during August-November 2022 and stood at 0.9 per cent in February, resulting in a significant drop in transport and communication inflation and its contribution to CPI core inflation (Chart II.21). On the other hand, gold prices firmed up y-o-y, resulting in an increase in personal care and effects inflation and its contribution to core inflation.     Threshold diffusion indices for CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold and silver indicate a high number of items registering price increases in excess of 4 per cent during September-October 2022. Since November 2022, the diffusion index for items registering price increases in excess of 6 per cent (saar) has moved lower, suggesting easing in the intensity of price increases (Chart II.22). A decomposition of CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold and silver inflation into its goods (with a weight of 20.7 per cent in the headline CPI) and services (weight of 23.0 per cent) components shows that goods inflation averaged 7.4 per cent during September 2022 to February 2023, higher than services inflation of around 5.4 per cent. The key drivers of goods inflation were clothing and footwear, household goods and services, and health (Chart II.23a). In services inflation, housing (primarily house rental charges) was the largest contributor, followed by transport services (bus/tram/taxi fares; air fare), and education (tuition and other fees) (Chart II.23b).   Trimmed mean measures12 also indicated elevated underlying inflation pressures, with the weighted median inflation rate at 6.8 per cent during December 2022-February 2023 (Table II.2). Other Measures of Inflation CPI inflation for agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and rural labourers (CPI-RL) exceeded CPI headline inflation during September 2022 - February 2023, primarily on account of food inflation being higher in CPI-AL and CPI-RL. Inflation in terms of CPI for industrial workers (CPI-IW), on the other hand, was below the headline CPI during the same period due to lower inflation in food, clothing and footwear, housing as well as the miscellaneous categories in CPI-IW vis-à-vis headline CPI. After ruling in double digits between April 2021 and September 2022, wholesale price index (WPI) inflation moderated to 3.9 per cent in February 2023 on the back of a fall in international commodity prices and favourable base effects. The sharp moderation in WPI inflation pulled down inflation measured by the deflators for gross value added (GVA) and gross domestic product (GDP) in Q3:2022-23 (Chart II.24a).  While WPI inflation outpaced CPI inflation in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, it moved below CPI inflation since December 2022. During September 2022-February 2023, CPI inflation ruled above the corresponding WPI groups/sub-groups in respect of spices, fruits, protein-based goods (pulses, egg and milk), and clothing and footwear. Deflation in edible oil and vegetable prices was higher in the WPI than in the CPI. On the other hand, inflation in fuel, petrol and diesel was higher in the former vis-à-vis the latter (Chart II.24b)13. Costs, as measured by WPI inflation relating to industrial raw materials and farm inputs prices, moderated gradually during H2:2022-23 (Chart II.25). Inflation in the prices of industrial inputs – such as high-speed diesel (HSD); naphtha; aviation turbine fuel (ATF); bitumen; and furnace oil – eased, mirroring the correction in international crude oil prices. The prices of non-food primary articles, particularly raw cotton and oilseeds softened in tandem with international prices and expectations of higher domestic production. Minerals price inflation moderated and turned to deflation from November 2022, driven by deflation in iron ore prices, and in copper concentrate prices from January 2023. Notwithstanding the easing in HSD prices, farm input price inflation remained elevated on account of high fodder price inflation. Inflation in price of WPI electricity – a key input in both industrial and farm inputs – persisted at elevated levels, reflecting higher input costs on the back of firmer international coal prices and increased domestic demand.  Nominal rural wage growth for both agricultural and non-agricultural labourers increased during October 2022-January 2023. While agricultural wage growth was broad-based across all occupations, the growth in non-agricultural wages was mainly driven by categories like beedi makers, blacksmiths, masons, electricians, and light motor vehicle (LMV)/tractor drivers (Chart II.26).  In the organised sector, growth in overall staff cost (y-o-y basis) accelerated in Q3:2022-23 for both manufacturing and services sectors. The share of staff cost in the value of production for both manufacturing and services was broadly unchanged in Q3:2022-23 from its level in Q2:2022-23 (Chart II.27). As per the firms polled in the Reserve Bank’s enterprise surveys14, the pace of salary outgoes for the manufacturing, infrastructure and services sectors is expected to remain broadly stable in Q1:2023-24. Input cost pressures are likely to ease in Q1:2023-24 and the pace of increase in selling prices is also expected to edge down for all the three sectors in Q1:2023-24 (Chart II.28).  One year ahead business inflation expectations15 that had risen in January 2023, edged down during February 2023 reflecting moderation in cost pressures.   As per manufacturing firms polled for the purchasing managers’ index (PMI), input prices picked up during December-February and output prices in general moderated with the input-output price gap returning to positive territory by February. The month of March saw a reversal in this trend with the gap again turning negative as input prices fell (Chart II.29a). In PMI services, input as well as output prices momentum softened during December-February and the input-output price gap has been largely range-bound since August 2022. There was an uptick in prices charged in the month of March with softening in input prices, leading to narrowing of input output price gap (Chart II.29b). A combination of adverse supply-side shocks and the pass-through of pending input costs to output prices exerted sustained pressures on headline inflation during 2022-23. The outlook for 2023-24 is subject to uncertainties surrounding climate-related disturbances such as heat wave and unseasonal rains. Moreover, a resurgence in geopolitical tensions could lead to supply chain dislocations and commodity price pressures; per contra, an earlier resolution of geopolitical hostilities can soften price pressures. Global demand conditions are turning more uncertain amidst rising financial market turbulence and financial stability concerns, which could weigh in on commodity prices. Amidst these elevated uncertainties, monetary policy remains focussed on progressively aligning inflation with the target. Pro-active supply measures by the Government remain vital to address bottlenecks and shortages in critical areas to mitigate volatility in inflation and enable a sustained disinflation. __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Headline inflation is measured by year-on-year changes in the all-India consumer price index (CPI) produced by the National Statistical Office (NSO). The y-o-y inflation numbers for April and May 2021 have been calculated based on the imputed index for April and May 2020 released by NSO. 2 Core CPI, i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel is worked out by eliminating the groups ‘food and beverages’ and ‘fuel and light’ from the headline CPI. 3 The zero price for PDS wheat and rice due to free distribution resulted in the transfer of their weights to other items in the cereals group (Das, Praggya and Asish Thomas George (2023), “Consumer Price Index: The Aggregation Method Matters”, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, March). 4 A change in CPI y-o-y inflation between any two months is the difference between the current m-o-m change in the price index (momentum) and the m-o-m change in the price index 12 months earlier (base effect). For more details, see Box I.1 of the MPR, September 2014. 5 The CPI diffusion index, a measure of dispersion of price changes, categorises items in the CPI basket according to whether their prices have risen, remained stagnant or fallen over the previous month. The higher the reading above 50, the broader is the expansion or generalisation of price increases; the further is the reading below 50, the broader is the price decline across items. 6 Threshold diffusion indices capture the dispersion of price increases in CPI basket beyond the specified saar thresholds of 4 per cent and 6 per cent. 7 Historical decomposition estimates the contribution of each shock to the movements in inflation over the sample period (Q4:2010-11 to Q4:2022-23) based on a vector autoregression (VAR) with the following variables (represented as the vector Yt) – crude oil prices (US$ per barrel); exchange rate (INR per US$), asset price (BSE Sensex), CPI; the output gap; rural wages; the policy repo rate; and money supply (M3). All variables other than policy repo rate are y-o-y growth rates. The VAR can be written in reduced form as: Yt =c + A Yt-1 + et; where et represents a vector of shocks. Using Wold decomposition, Yt can be represented as a function of its deterministic trend and sum of all the shocks et. This formulation facilitates decomposition of the deviation of inflation from its deterministic trend into the sum of contributions from various shocks. 8 The IOTs are based on the Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables (OECD, 2021) applied to Indian context. 9 The CPI weighting diagrams use the modified mixed reference period (MMRP) data based on the 2011-12 Consumer Expenditure Survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). Under MMRP, data are collected on expenditures incurred for frequently purchased items – edible oil, eggs, fish, meat, vegetables, fruits, spices, beverages, processed foods, pan, tobacco and intoxicants – during the last seven days; for clothing, bedding, footwear, education, medical (institutional), durable goods, during the last 365 days; and for all other food, fuel and light, miscellaneous goods and services including non-institutional medical services, rents and taxes, data relate to the last 30 days. 10 Global commodities that drive domestic prices include petroleum products; coal; electronic goods; gold; silver; chemical products; metal products; textiles; cereals; milk products, and vegetables oils – these together have a weight of 36.4 per cent in the CPI basket. 11 Item level retail and wholesale prices are aggregated at respective sub-groups using item level CPI weights. Data for January-March 2021 have been excluded due to changes in price collection mechanism and item varieties by DCA. 12 While exclusion-based measures drop a fixed set of volatile items (for example, food and fuel) in each period, trimmed measures exclude items located in the tails of the inflation distribution - items displaying changes more than the specified threshold in prices each month are excluded, and the items dropped differ from month to month. 13 The divergence in WPI and CPI petrol and diesel inflation emanated from the fact that while the cut in the central excise duties led to a fall in CPI petrol and diesel prices (on a y-o-y basis), WPI was not impacted as prices in WPI are computed net of domestic excise duty effects. 14 Industrial Outlook Survey; and Services and infrastructure Outlook Survey. 15 Based on the monthly Business Inflation Expectations Survey (BIES) of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. The survey polls a panel of business leaders primarily from the manufacturing sector about their inflation expectations in the short and medium term. Domestic demand remained resilient in H2:2022-23, with investment activity gaining ground but private consumption exhibiting sluggishness. On the supply side, a rebound in contact-intensive services compensated for manufacturing sector which was pulled down by elevated input cost pressures. Protracted geopolitical tensions, tighter global financial conditions, global financial market volatility and slowing external demand pose risks to the outlook. Domestic demand remained resilient in H2:2022-23, with investment activity gaining ground on the back of the government’s continued thrust on capex. Private consumption exhibited sluggishness with normalisation of the pandemic induced pent-up demand and the dampening effect of inflationary pressures. Slowing global demand weighed on merchandise exports; however, with imports declining, the drag from net exports moderated. Overall, real gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 4.8 per cent in H2:2022-23, up by 12.3 per cent over its pre-pandemic level. On the supply side, the rebound in contact-intensive services was sustained. The manufacturing sector was pulled down by elevated input cost pressures. Spillovers from protracted geopolitical tensions, tighter global financial conditions, global financial market volatility and slowing external demand pose risks to the outlook. Aggregate demand, measured by real GDP, expanded by 4.4 per cent (year-on-year, y-o-y) in Q3:2022-23 and by an estimated 5.1 per cent in Q4 (Chart III.1 and Table III.1). The momentum – the quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q) seasonally adjusted annualised growth rate (saar) – remained strong in Q3 and Q4. For the financial year 2022-23 as a whole, real GDP rose by 7.0 per cent on top of 9.1 per cent in the preceding year. India remained the fastest growing major economy in 2022-23 reflecting dominant role of domestic drivers in the growth process (Box III.1).

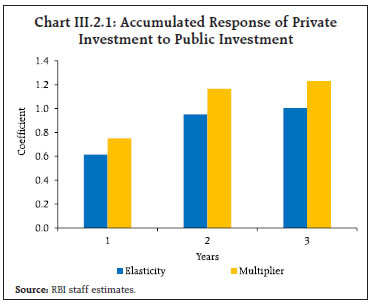

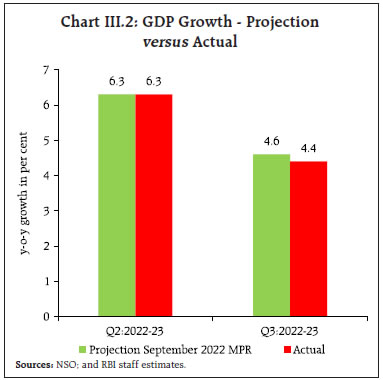

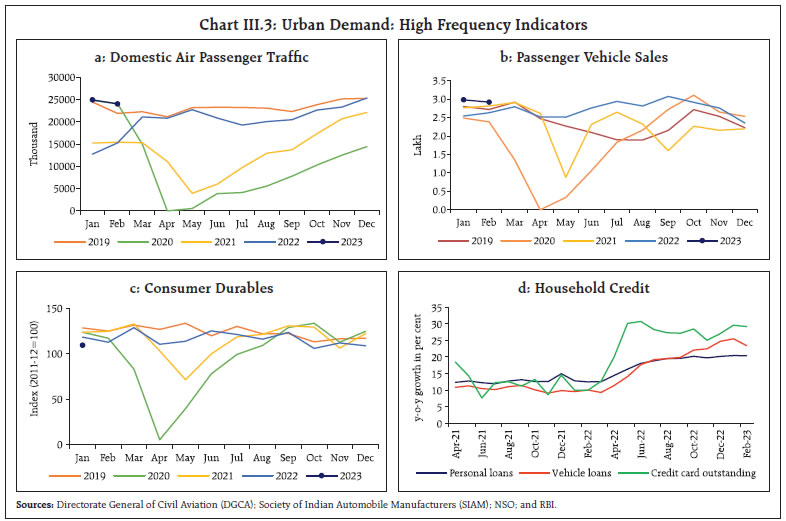

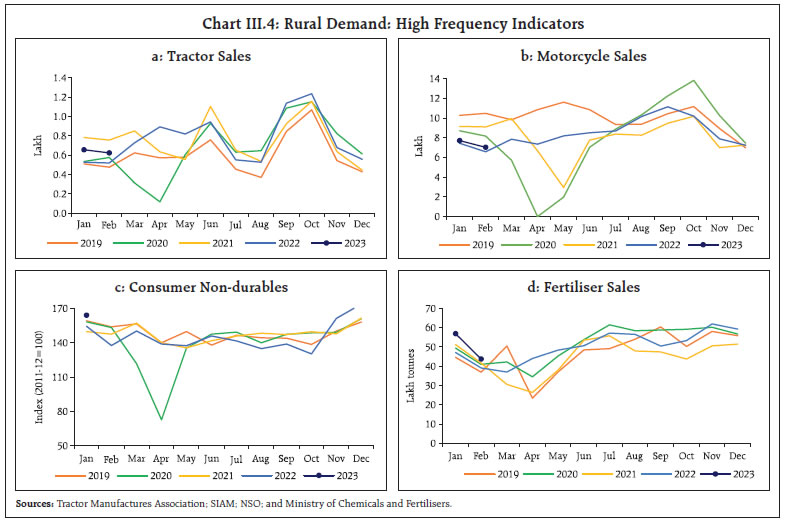

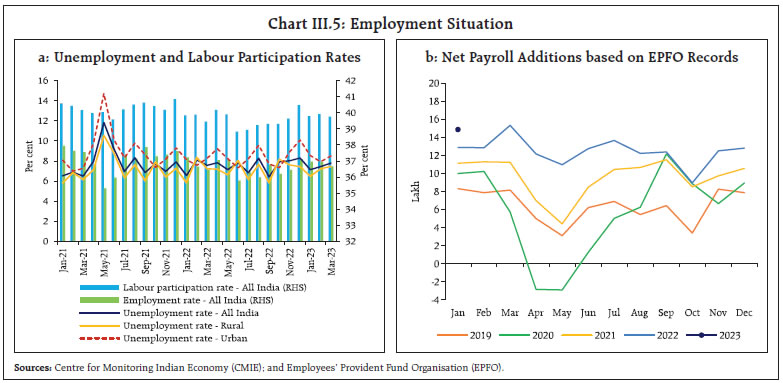

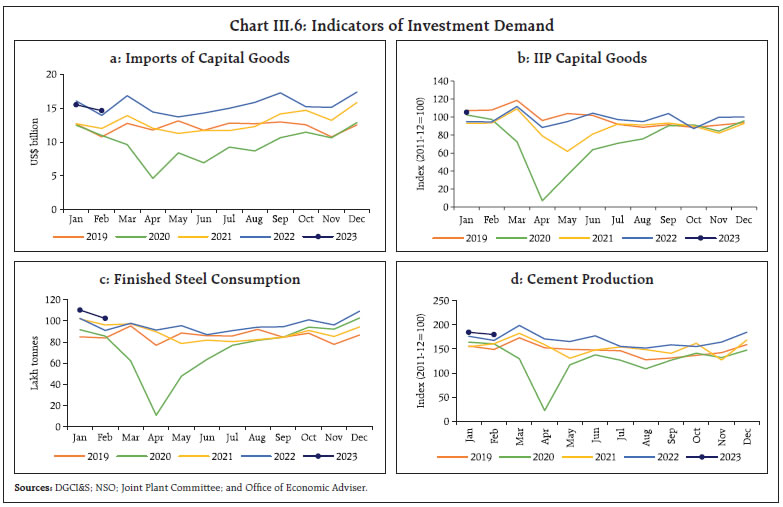

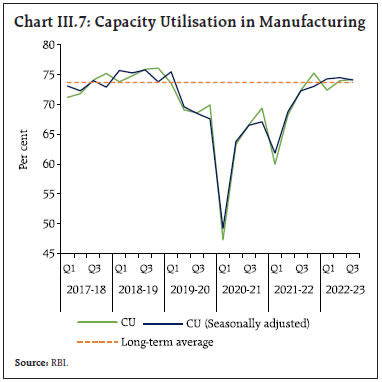

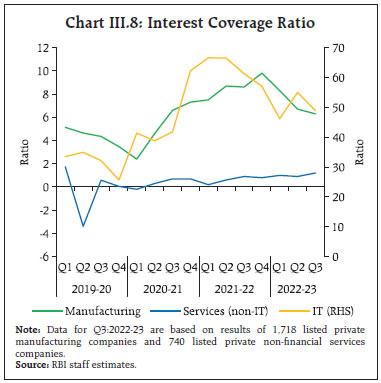

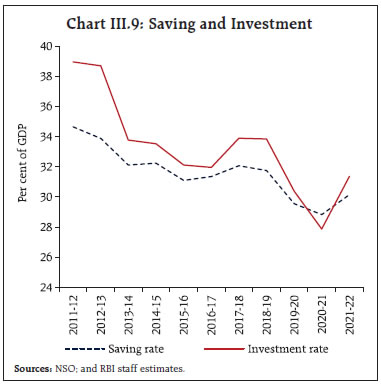

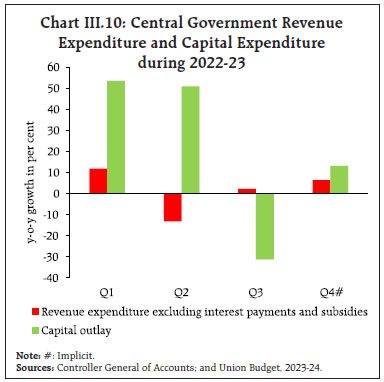

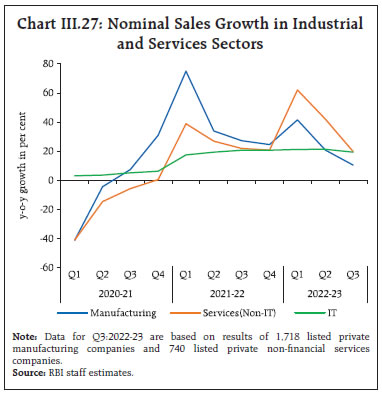

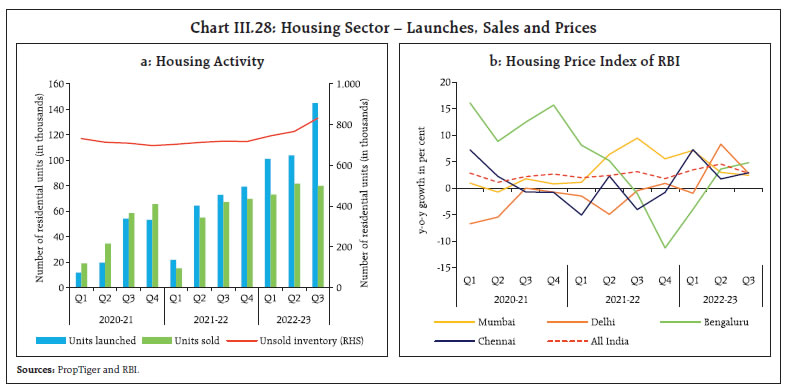

GDP Projections versus Actual Outcomes The September 2022 Monetary Policy Report (MPR) projected real GDP growth at 6.3 per cent for Q2:2022-23, and 4.6 per cent each for Q3 and Q4. The actual growth rate at 6.3 per cent in Q2 turned out to be in line with the projection (Chart III.2). In Q3, the outturn undershot the projection by 20 basis points (bps) due to lower than expected growth in private consumption and government expenditure. Data for Q4:2022-23 are scheduled to be released by the NSO on May 31, 2023. III.1.1 Private Final Consumption Expenditure Growth in private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) – the mainstay of aggregate demand – decelerated from an above trend pace of 20.0 per cent in Q1:2022-23 to 8.8 per cent in Q2 and 2.1 per cent in Q3 due to the ebbing pandemic-related pent-up demand and high inflation.  Amongst the high frequency indicators (HFIs) of urban demand, domestic air passenger traffic witnessed a sustained pick up from August 2022 and surpassed its pre-pandemic level in December 2022-February 2023 (Chart III.3). Passenger vehicle sales and household credit posted robust growth in H2. Consumer durables, on the other hand, contracted in Q3 and January 2023, partly reflecting a shift in households spending from goods to services with the receding pandemic. Rural demand showed some signs of recovery in H2, albeit it is lagging urban demand. Amongst the HFIs, tractor sales grew robustly in H2 while motorcycle sales growth returned to positive territory in January-February 2023 after a marginal contraction in December 2022. Consumer non-durables output expanded for the third consecutive month in January 2023, following a decline during July-October (Chart III.4). The demand for work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) moderated in Q3 and Q4 in tandem with the improving rural job market on the back of higher rabi sowing and recovery in informal sector employment. The labour force participation rate, as per the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s (CMIE) Consumer Pyramid data, remained unchanged in Q4 and the unemployment rate moved lower across both urban and rural segments (Chart III.5a). Organised sector employment, as reflected in the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) payrolls data, strengthened considerably in Q3 and in January 2023 as compared with the same period last year (Chart III.5b). According to Naukri Jobspeak data, increased hiring was witnessed in insurance, hospitality, banking, financial services and real estate sectors.     III.1.2 Gross Fixed Capital Formation Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) posted a growth of 8.3 per cent in Q3:2022-23 on top of 14.8 per cent growth in H1. Its share in GDP rose to 31.8 per cent in Q3 from 30.6 per cent a year ago. Construction activity gathered steam post-monsoon on the back of housing demand and the government’s thrust on infrastructure spending. Cement production and steel consumption – indicators of fixed investment – grew strongly in Q3 and Q4. In the case of investment in machinery and equipment, production of capital goods stayed resilient in Q3 and January 2023; imports of capital goods were buoyant in Q3 and the pace of expansion decelerated during January-February 2023 (Chart III.6). According to the RBI’s survey2, capacity utilisation (CU) in the manufacturing sector improved marginally to 74.3 per cent in Q3:2022-23 from 74.0 per cent in the previous quarter. The seasonally adjusted CU, however, dropped to 74.1 per cent from 74.5 per cent over the period, although it remained above its long-period average (Chart III.7). The Union Budget 2023-24 has projected a growth of 37.4 per cent in capital expenditure over its revised estimates for 2022-23 and this is expected to crowd in private investment (Box III.2).  The interest coverage ratio (ICR)3 of listed private companies in the manufacturing and information technology (IT) sectors remained comfortable in Q3:2022-23, indicating adequate debt servicing capacity (Chart III.8). The ICR of services sector (non-IT) improved in Q3 and crossed the threshold level of unity for the first time since Q1:2019-20.