IST,

IST,

Chapter II: Financial Institutions: Soundness and Resilience

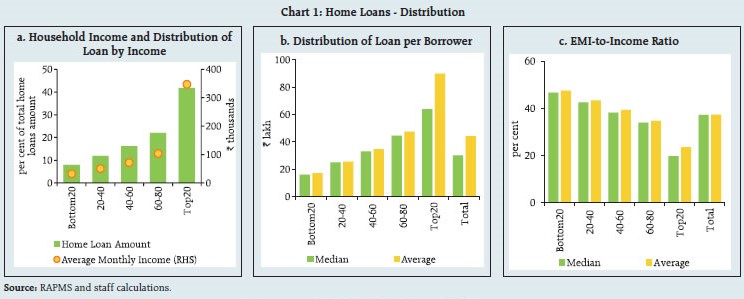

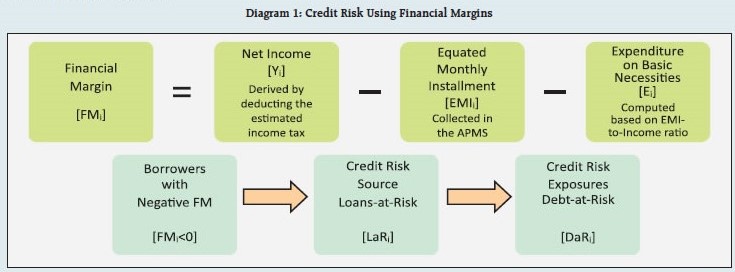

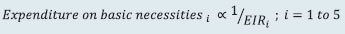

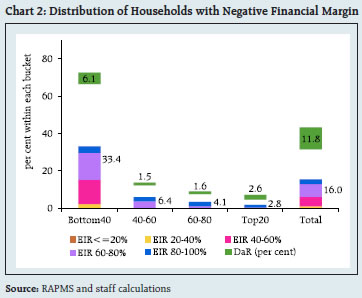

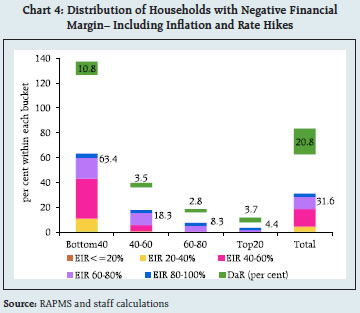

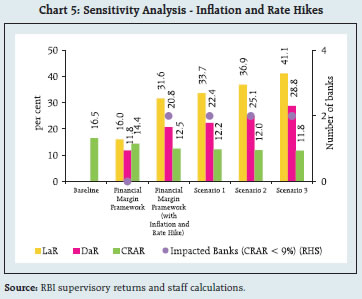

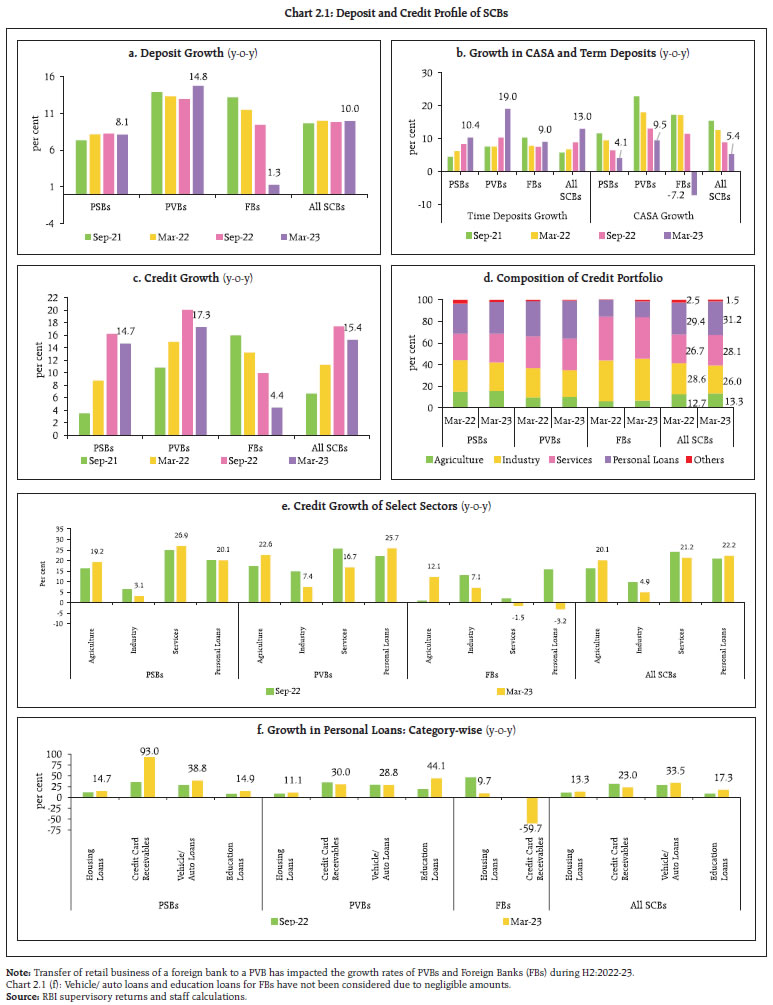

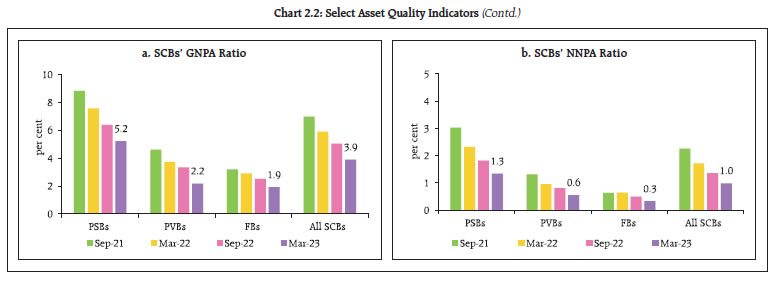

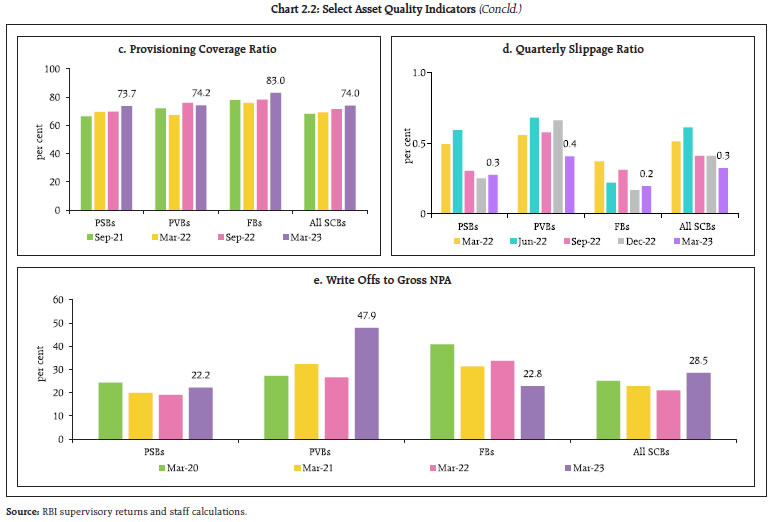

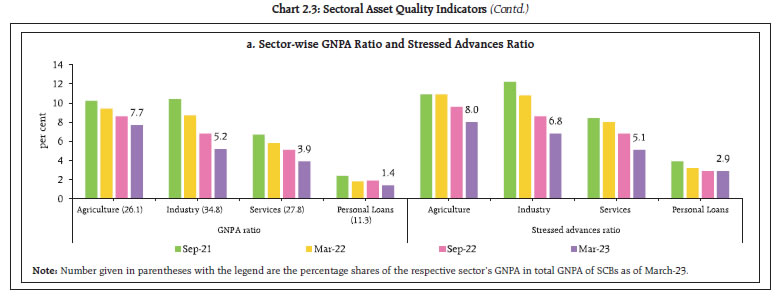

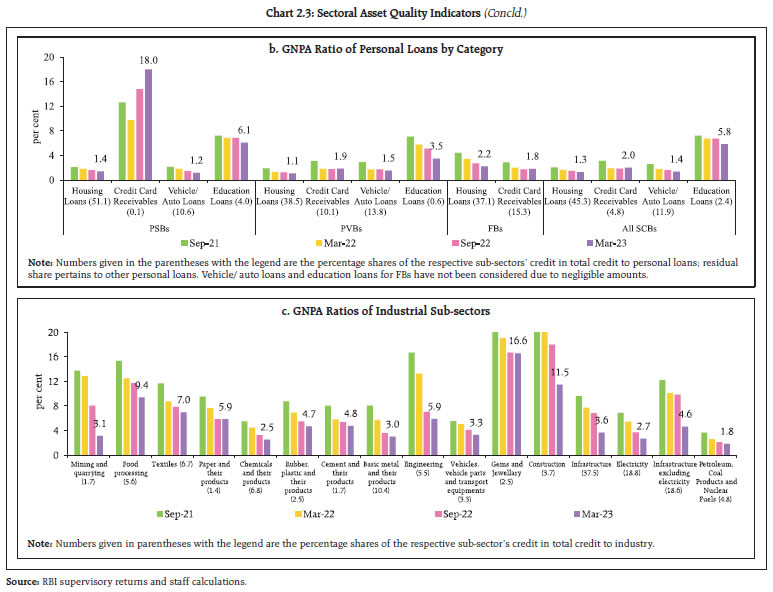

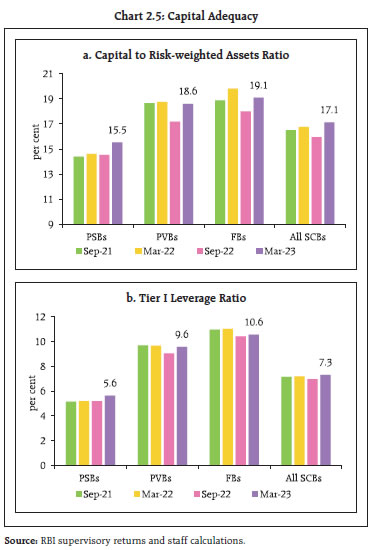

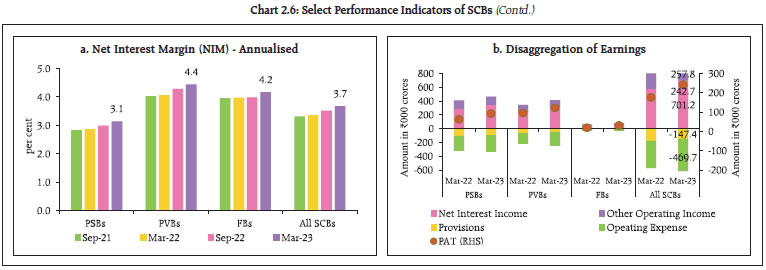

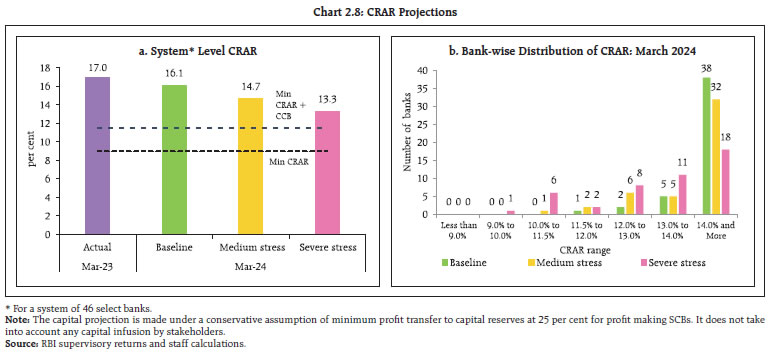

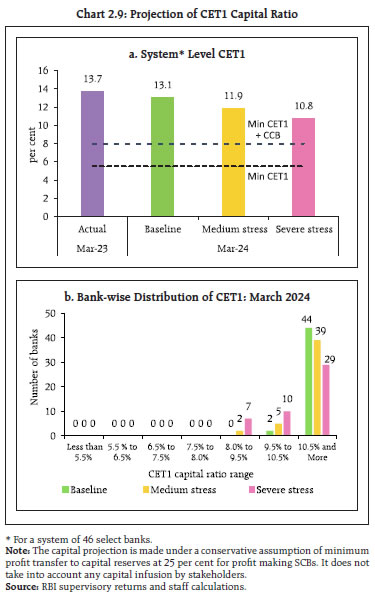

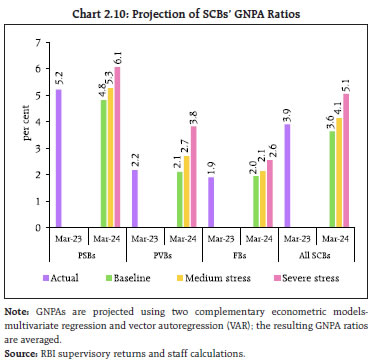

Notwithstanding recent global financial market turbulence and acute banking stress in some jurisdictions, the Indian financial sector has remained stable and resilient, with further improvement in asset quality, capital and profitability. Macro stress tests for credit risk reveal that all banks would comply with the minimum capital requirements even under a severe stress scenario. Contagion and solvency risks have reduced. Introduction 2.1 Since the December 2022 FSR, the Indian banking sector has expanded its balance sheet, business and profitability. Even as gross non-performing assets (GNPA) and net non-performing assets (NNPA) as ratios to gross loans and advances, of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) declined to a decadal low, the system-level capital to risk-weighted assets ratio (CRAR) reached a new high. The net interest margin (NIM) increased further and post-tax profits recorded growth as credit expanded alongside adequate provisioning and strengthening of capital buffers. Banks’ exposure to large borrowers reflected, in general, reduced concentration in gross loans, improvement in asset quality and containment of potential slippages. Within the large borrowers’ cohort, however, big corporates increased their recourse to bank financing – the share of top 100 borrowers in total credit has been rising since September 2021. 2.2 As credit growth has been outpacing deposit growth, financing conditions, especially banks’ cost of funds have tightened. The retail sector has been a major driver of bank credit growth in the recent period. 2.3 This chapter presents an evaluation of the soundness and resilience of financial intermediaries in India through an analysis of various key parameters such as business mix, asset quality, concentration of large borrowers, capital adequacy, earnings and profitability. Section II.1 analyses the performance of SCBs and their resilience in the context of macroeconomic shocks through stress tests and sensitivity analysis. Sections II.2 and II.3 examine the recent financial performance of urban cooperative banks (UCBs) and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), respectively, and evaluate their resilience through stress tests. Sections II.4, II.5 and II.6 provide insights into the soundness and resilience of insurance sector, mutual funds, and clearing corporations, respectively. Section II.7 concludes with a detailed analysis of the network structure and connectivity of the Indian financial system with contagion analysis under adverse scenarios. II.1 Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs)1 2 3 4 2.4 Aggregate deposits growth, which had undergone a slight moderation during 2021-22 and H1:2022-23, picked up pace to reach 11.8 per cent as on June 02, 2023. This growth was mainly driven by private sector banks (PVBs) (Chart 2.1 a). In the rising interest rate cycle, term deposits have garnered healthy accretions at the cost of current account and savings account (CASA) deposits (Chart 2.1 b).  2.5 SCB’s credit growth (y-o-y) has been accelerating since early 2022, led by both public sector banks (PSBs) and PVBs; by June 02, 2023, it reached 15.4 per cent (Chart 2.1 c). Credit for agriculture, services and personal loans grew faster than lending to the industrial sector (Chart 2.1 d and e). In particular, personal loans recorded a broad-based growth of 22.2 per cent (y-o-y) with all major segments, viz., housing, credit card receivables, vehicle/ auto loans, education loans, registering robust growth (Chart 2.1 f). 2.6 The strength of loan demand was reflected in the rising volume of new loans extended by SCBs; of which agriculture, households and working capital loans registered over 20 per cent growth (Table 2.1). II.1.1 Asset Quality 2.7 The asset quality of SCBs continued to improve and their GNPA ratio declined to 3.9 per cent in March 2023 – a 10-year low. SCBs’ NNPA ratio5 also improved to 1.0 per cent, a level last observed in June 2011, indicative of active and deep provisioning. In fact, SCBs’ provisioning coverage ratio (PCR)6 improved to 74.0 per cent in March 2023 (Chart 2.2 a, b and c). The quarterly slippage ratio, measuring new accretions to NPAs as a share of standard advances at the beginning of the quarter, moderated further (Chart 2.2 d). The write-off to GNPA ratio7, which had been declining consecutively through 2020-21 and 2021-22, increased in 2022-23 due to large write-offs by PVBs (Chart 2.2 e).   II.1.2 Sectoral Asset Quality 2.8 The improvement in SCBs’ asset quality has been broad based, with a steady decline in the stressed advances ratio across all major sectors (Chart 2.3 a). While there has been an overall improvement in asset quality in respect of personal loans, impairments in the credit card receivables segment have risen marginally (Chart 2.3 b). Within the industrial sector, asset quality continued to improve across sub-sectors (Chart 2.3 c).   II.1.3 Credit Quality of Large Borrowers8 2.9 The share of large borrowers in gross advances of SCBs declined successively over the past three years (viz., from 51.1 per cent in March 2020 to 46.4 per cent in March 2023) as retail loans grew faster than borrowings by corporates. The share of large borrowers in the GNPAs of SCBs also came down substantially (viz., from 75.7 per cent in March 2020 to 53.9 per cent in March 2023) (Chart 2.4 a). Asset quality in the large borrower portfolio saw significant improvement: the GNPA ratio declined from 12.2 per cent to 4.5 per cent over this period (Chart 2.4 b). Although there has been an increase in SMA-19 loans during the March 2023 quarter, the total stock of SMA category loans has fallen by 26.2 per cent (q-o-q) in the same period (Chart 2.4 c). Improvement in the SMA-2 ratio in March 2023 across bank groups reflected the containment of potential slippages during H2:2022-23 (Chart 2.4 d). In the large borrower accounts, the proportion of standard assets to total funded amount outstanding improved from 86.2 per cent in March 2020 to 94.3 per cent in March 2023 with corresponding declines in NPAs (Chart 2.4 e). The asset quality of top 100 borrowers improved, with their share in SCBs’ GNPA declining from 6.8 per cent as of March 2022 to 1.6 per cent as of March 2023 (Chart 2.4 f).  II.1.4 Capital Adequacy 2.10 In H2:2022-23, the capital to risk-weighted assets ratio (CRAR) of SCBs improved across bank groups (Chart 2.5 a). Their Tier I leverage ratio10 also increased during H2:2022-23 as they bolstered their capital base through capitalisation of reserves due to increased profits as well as by raising fresh capital (Chart 2.5 b). II.1.5 Earnings and Profitability 2.11 SCBs sustained the momentum in profitability as their net interest margin (NIM) continued to grow. During 2022-23, the NIM improved by 30 bps as transmission of monetary policy tightening to deposit rates lagged the pass-through to lending rates (Chart 2.6 a). SCBs’ profit after tax (PAT) recorded a healthy growth of 38.4 per cent (y-o-y) during 2022-23, led by strong increase in net interest income (NII) and lowering of provisions. PAT of PSBs grew at a faster rate than that of PVBs whose operating expenses increased by 29.4 per cent (Chart 2.6 b). 2.12 Higher profitability was also reflected in further improvement in the return on equity (RoE) and the return on assets (RoA) ratios (Chart 2.6 c and d). In response to higher interest rates, the cost of funds increased by 30 bps at the system level during 2022-23 (Chart 2.6 e). The increase in interest income improved the yield on assets (Chart 2.6 f).    II.1.6 Resilience – Macro Stress Tests 2.13 Macro stress tests are performed to assess the resilience of SCBs’ balance sheets to unforeseen shocks emanating from the macroeconomic environment. These tests attempt to assess capital ratios over a one-year horizon under a baseline and two adverse11 (medium and severe) scenarios. The baseline scenario is derived from the projected values of macro variables. The medium and severe adverse scenarios are arrived at by applying 0.25 to one standard deviation (SD) shocks and 1.25 to two SD shocks, respectively, to the macroeconomic variables, increasing the shocks sequentially by 25 basis points in each quarter (Chart 2.7).   2.14 Stress test results reveal that SCBs are well capitalised and capable of absorbing macroeconomic shocks over a one-year horizon even in the absence of any further capital infusion. Under the baseline scenario, the aggregate CRAR of 46 major banks is projected to slip from 17.0 per cent in March 2023 to 16.1 per cent by March 2024. It may go down to 14.7 per cent in the medium stress scenario and to 13.3 per cent under the severe stress scenario by March 2024, remaining above the minimum capital requirement including the capital conservation buffer (CCB) (11.5 per cent) (Chart 2.8 a). None of the 46 SCBs would breach the minimum capital requirement of 9 per cent in the next one year, even in a severely stressed situation, although 7 SCBs may fall short of the minimum capital inclusive of the CCB (Chart 2.8 b). 2.15 The common equity Tier I (CET1) capital ratio of the select 46 SCBs may decline from 13.7 per cent in March 2023 to 13.1 per cent by March 2024 under the baseline scenario (Chart 2.9 a). Even in a severely stressed macroeconomic environment, the aggregate CET1 capital ratio would deplete by 290 basis points only, which would not breach the minimum regulatory norms. Furthermore, all the banks would be able to meet the minimum regulatory CET1 capital ratio of 8.0 per cent (including the CCB) over the next one year under the severe stress scenario (Chart 2.9 b).  2.16 As per the stress test results, the GNPA ratio of all SCBs may improve to 3.6 per cent by March 2024 under the baseline scenario (Chart 2.10). If, however, the macroeconomic environment worsens to a medium or severe stress scenario, the ratio may rise to 4.1 per cent and 5.1 per cent, respectively. At bank group level, the GNPA ratios of PSBs may swell from 5.2 per cent in March 2023 to 6.1 per cent in March 2024 under the severe stress scenario, whereas it may go up from 2.2 per cent to 3.8 per cent for PVBs and from 1.9 per cent to 2.6 per cent for Foreign Banks (FBs). 2.17 High inflation coupled with rise in borrowing costs adversely impacts finances of households and their loan repayment capacity, which can have implications for lending banks. Identifying different measures of risks using individual home loan data, it is found that a twin shock in the form of a simultaneous increase in inflation and lending rates can put even households with sustainable repayment capacity at risk and double the loans-at-risk (LaR) (Box 2.1).

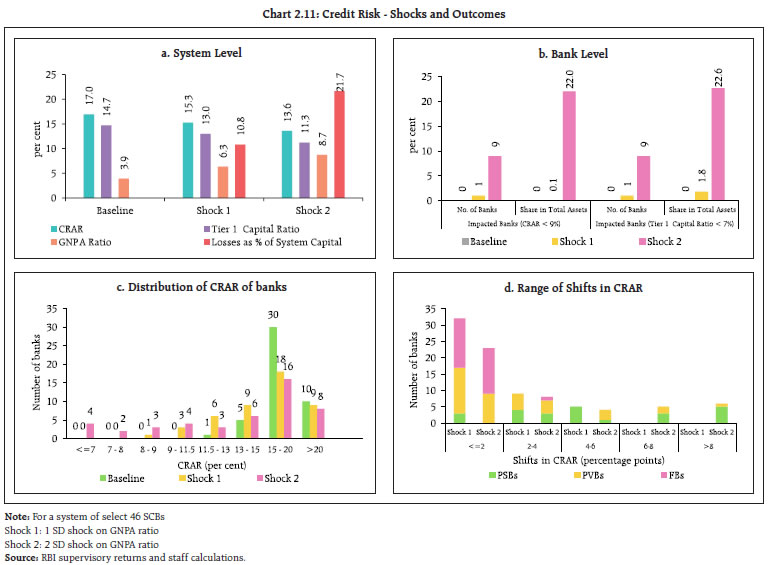

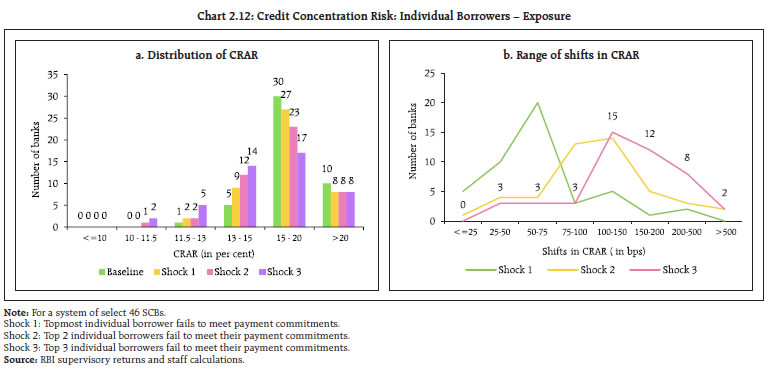

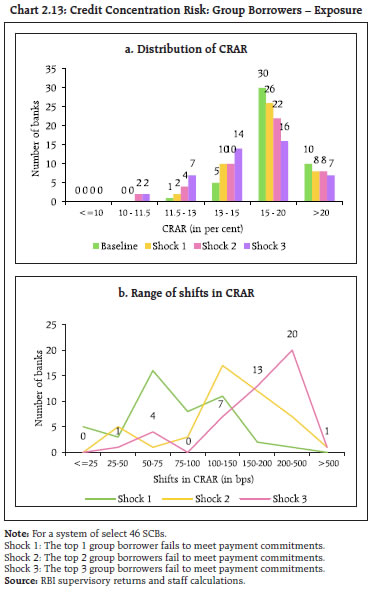

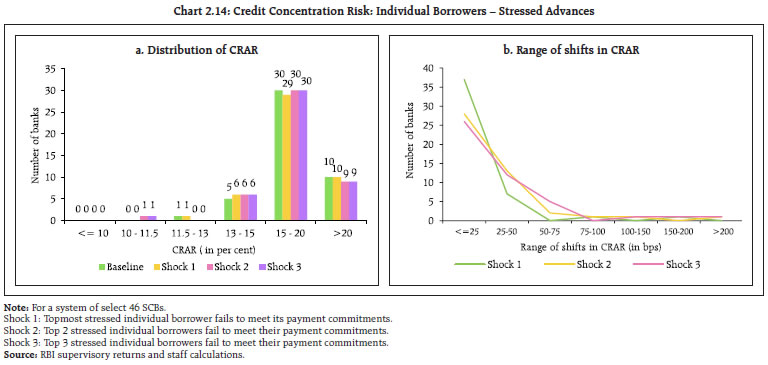

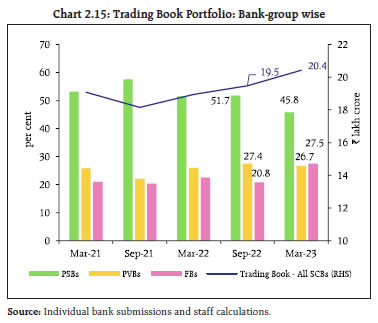

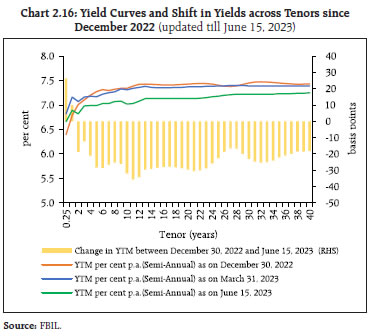

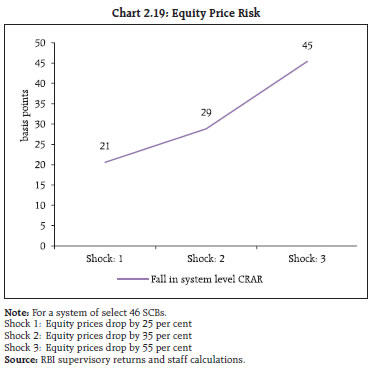

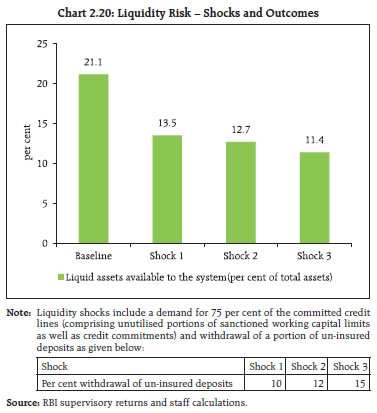

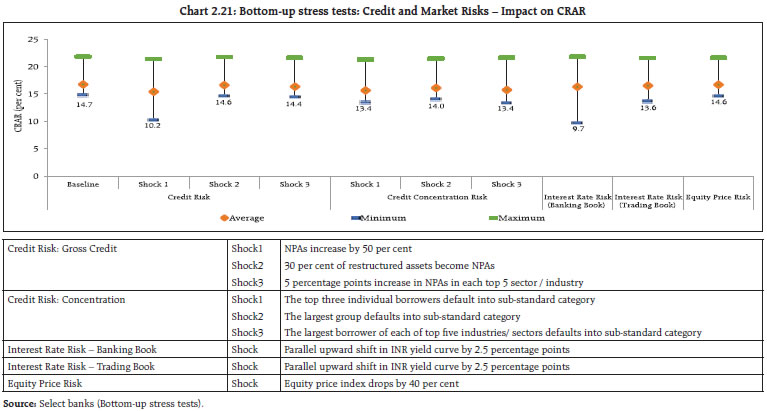

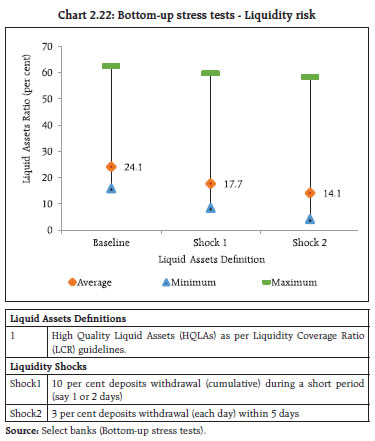

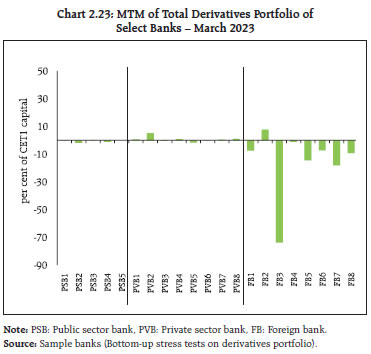

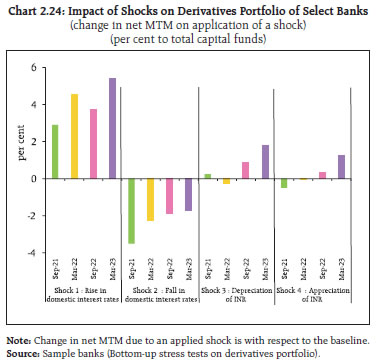

II.1.7 Sensitivity Analysis16 2.18 Top-down17 sensitivity analysis involving several single-factor shocks to assess the vulnerabilities of SCBs to simulated credit, interest rate, equity price and liquidity risks under various stress scenarios18 is carried out in this sub-section. a. Credit Risk 2.19 Credit risk sensitivity has been analysed under two scenarios wherein the system-level GNPA ratio is assumed to rise from its prevailing level by (i) one SD19; and (ii) two SDs, in a quarter. Under a severe shock of two SDs (a) the aggregate GNPA ratio of 46 select SCBs moves up from 3.9 per cent to 8.7 per cent; (b) the system-level CRAR depletes by 340 bps from 17 per cent to 13.6 per cent; and (c) the Tier 1 capital ratio goes down from 14.7 per cent to 11.3 per cent, well above the respective regulatory minimum levels. The system-level capital impairment could be 21.7 per cent in this case (Chart 2.11 a). The reverse stress test shows that a shock of 6 SDs would be required to bring down the system-level CRAR to the regulatory minimum of 9 per cent. A shock of 3.3 SDs, however, can bring down the system-level CRAR below 11.5 per cent, which is the regulatory minimum CRAR, inclusive of the CCB. 2.20 Bank-level stress test results show that under the severe (two SD) shock scenario, nine banks with a share of 22.0 per cent of SCBs’ total assets may fail to maintain the regulatory minimum level of CRAR (Chart 2.11 b). In such a scenario, the CRAR would fall below 7 per cent in case of four banks (Chart 2.11 c) and six banks would record a decline of over eight percentage points in the CRAR. In general, PVBs and FBs would face lower erosion in CRAR than PSBs under both scenarios (Chart 2.11 d).   b. Credit Concentration Risk 2.21 Stress tests on banks’ credit concentration – considering top individual borrowers according to their standard exposures – show that in the extreme scenario of the top three individual borrowers of respective banks failing to repay20, no bank would face a situation of a drop in CRAR below the regulatory requirement of 9 per cent, although two banks would see a decline in CRAR below the regulatory minimum inclusive of the CCB (Chart 2.12 a). In this extreme stress case, ten banks would experience a fall of more than two percentage points in their CRARs (Chart 2.12 b). 2.22 Under the extreme scenario of the top three group borrowers in the standard category failing to repay21, CRARs of all banks would remain above 9 per cent, but two banks may fail to meet the regulatory minimum inclusive of the CCB (Chart 2.13 a) and one bank may face a decline of more than five percentage points in CRAR (Chart 2.13 b).   2.23 In the extreme scenario of the top three individual stressed borrowers of respective banks failing to repay22, majority of the banks would remain resilient, with their CRARs depleting by mere 25 bps or lower (Chart 2.14 a and b). c. Sectoral Credit Risk 2.24 Shocks applied on the basis of volatility of industry sub-sector wise GNPA ratios indicate varying magnitudes of increase in GNPAs across different sub-sectors. By and large, sectoral credit risk remains muted - a two SD shock to basic metals and energy sub-sectors would reduce the system-level CRAR by merely 16 and 15 bps respectively, whereas the impact of the shocks on the rest of the sub-sectors is negligible (Table 2.2). d. Interest Rate Risk 2.25 The market value of investments subject to fair value for the sample of SCBs under review stood at ₹20.4 lakh crore in March 2023 (Chart 2.15) of which 92.5 per cent were classified as ‘available for sale (AFS)’ and the remaining were under the ‘held for trading (HFT)’ category. PSBs’ share in the total trading book portfolio of SCBs has been tapering since June 2022 to reach a low of 45.8 per cent in March 2023. Concomitantly, the share of FBs has burgeoned during the same period. 2.26 The sensitivity (PV0123) of the AFS portfolio has generally eased for PSBs in comparison with their December 2022 position, reflecting reduction in modified duration and size of the portfolio. The sensitivity for PVBs and FBs, however, has increased; in particular, FBs have shown a sharp increase in their PV01. In terms of PV01 curve positioning, the tenor-wise distribution of PSBs’ portfolio indicates higher allocation in the 1-5 year and 5-10 year buckets. Around four-fifths of PSBs’ AFS portfolio remains in the 1-5 year and 5–10 year buckets. PVBs have built up positions in the less than 1-year and more than 10-year buckets while paring allocations in intermediate buckets. FBs continue to prefer the more than 10-year bucket though they have also increased their holding in the 1-5 year bucket. Although PV01 exposure of FBs in the highest maturity segment remains substantial, it may not be an active contributor to risk as some positioning involves bonds held as cover for hedging derivatives (Table 2.3). 2.27 The interest rate exposure of PVBs and FBs in their HFT portfolios remained higher than that of PSBs, the latter having almost fully squared positions in March 2023 while the PVBs have decreased their sensitivity (PV01) in the HFT portfolio. Both PSBs and PVBs have built up bulk of their positions in the 1-5 year and 5-10 year buckets. FBs have increased the sensitivity of their portfolio by increasing allocation to long-duration securities (more than 10 years) (Table 2.4).  2.28 It is assessed that a parallel upward shift of 250 bps in the yield curve would reduce the system level CRAR and CET1 capital ratio by 93 bps each (Table 2.5). At a disaggregated level, six banks would face a situation in which the CRAR will fall below the regulatory minimum (including the CCB). 2.29 As on June 15, 2023 the sovereign yield curve has ‘bear flattened’, with the short end of the curve moving up sharply vis-a-vis its December 2022 position, leading to spread compression. 2.30 The longer end of the yield curve has also moved down by June 15, 2023, from its position in December 2022, facilitated in a large measure by the easing of inflation. The budget announcement of government borrowing programme for 2023-24 in line with expectations further underpinned the downward movement in long-term yields (Chart 2.16). 2.31 The yield curve contains important clues on the likely behaviour of the economy. The flattening of the yield curve and decline in curvature signals that inflation expectations are getting re-anchored after multiple shocks in 202224 (Table 2.6). In the Indian context, the curvature25 of the yield curve has more information content on future macroeconomic outcomes than the slope26. 2.32 Trading profits of PSBs and PVBs declined in Q4:2022-23. Trading losses for FBs continued for the ninth consecutive quarter although they decreased from a peak in June 2022. The share of trading profits in net operating income was in single digits for PSBs and PVBs, while the trading loss reduced net operating income for FBs (Table 2.7).

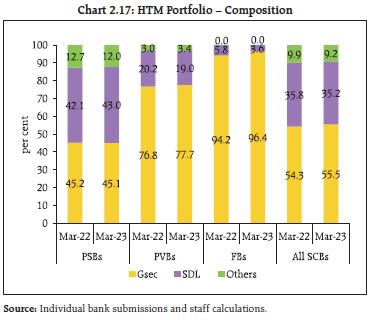

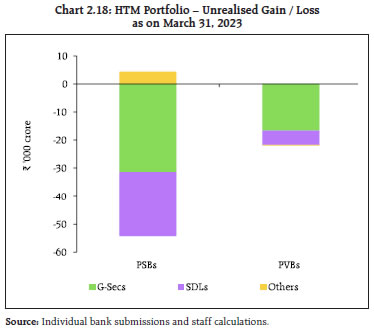

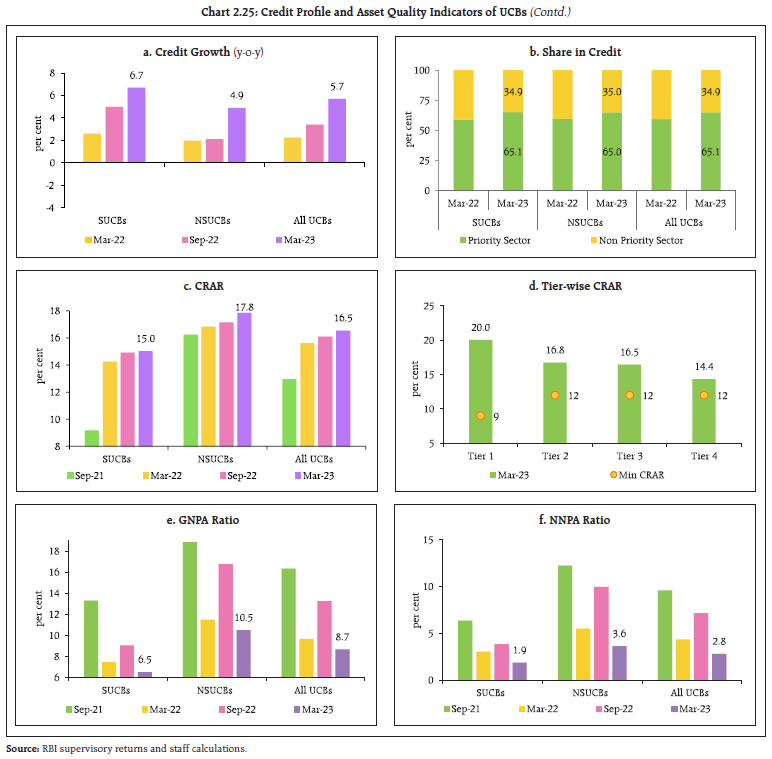

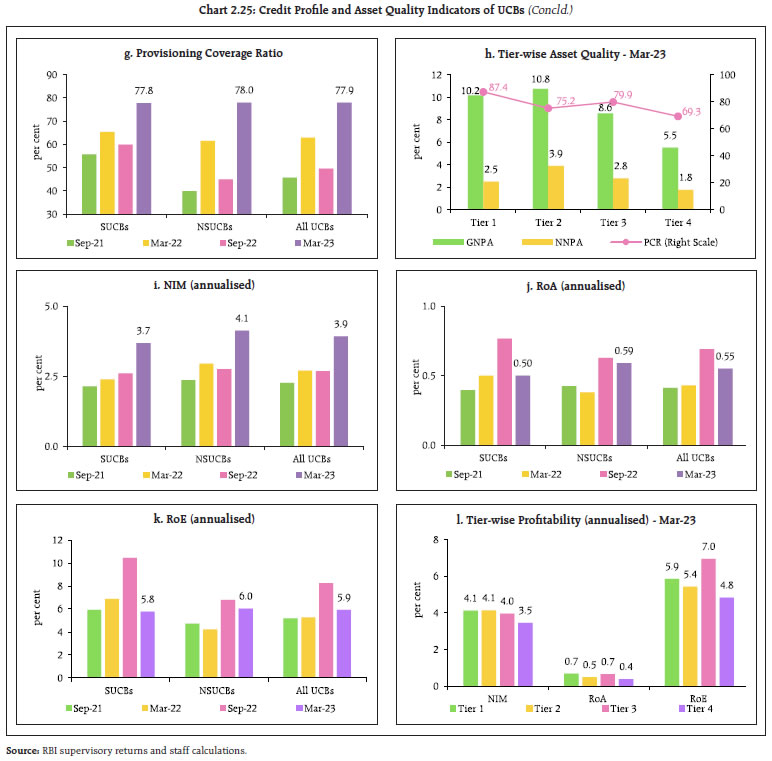

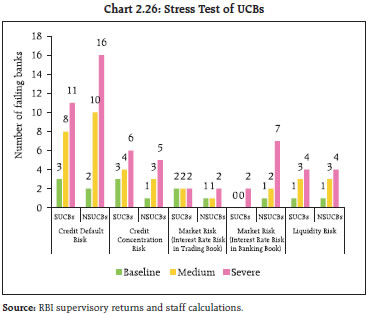

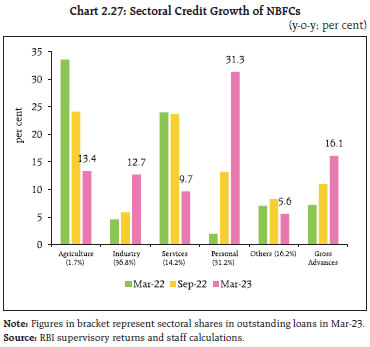

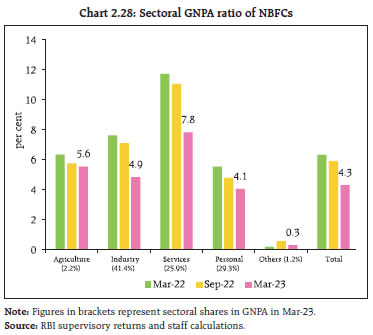

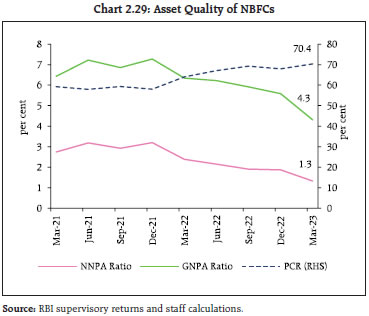

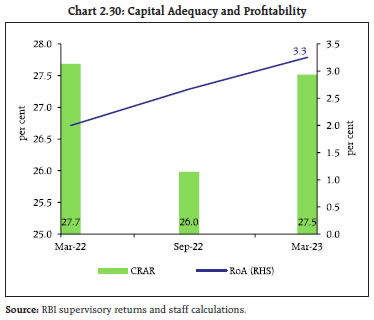

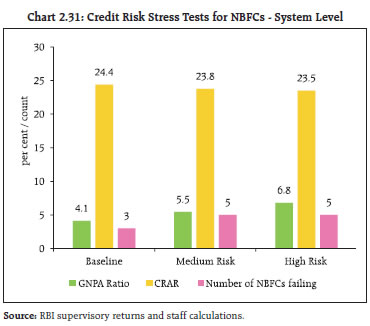

2.33 PSBs preferred to pare their allocation in G-Secs and other securities eligible for holding in the HTM category while increasing their holdings in state development loans (SDLs) (Chart 2.17). PVBs increased their holding of G-Secs and other securities in the HTM category, while decreasing holding of SDLs. 2.34 As interest rates moved up in rapid succession over the past one year, both PSBs and PVBs recorded notional losses across G-Secs and SDLs held in their HTM books. The notional loss in the HTM book of SCBs (PSBs and PVBs) was ₹71,817 crore as at end March 2023 as compared with a notional profit of ₹418 crore as at end March 2022. 2.35 The distribution of unrealised losses across PSBs and PVBs indicates a contrasting picture across bank cohorts. Unrealised losses of PSBs are largely in G-Secs although the proportion of central and state government securities held by them in the HTM portfolio are by and large equal, but for PVBs the losses were distributed largely in line with their proportion of holdings (Chart 2.18). 2.36 If a shock in the form of 250 bps parallel upward shift in the yield curve is applied, the mark-to-market impact on the HTM portfolio of banks, excluding unrealised losses would reduce the system level CRAR 343 bps. In respect of twelve banks, the CRAR would fall below the minimum regulatory requirement (including the CCB) of 11.5 per cent. 2.37 In March 2023, holdings of statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) securities by PSBs and PVBs in the HTM category amounted to 21.5 per cent and 20.0 per cent, respectively, of their net demand and time liabilities (NDTL), while it stood at 3.8 per cent for FBs. PSBs and PVBs sequentially increased their holdings of SLR securities in the HTM portfolio.   2.38 An assessment of the interest rate risk of banks27 using Traditional Gap Analysis (TGA) and Duration Gap Analysis (DGA) is done for rate sensitive global assets, liabilities and off-balance sheet items of banks. TGA for time buckets up to one year, shows that Earnings at Risk (EAR) is positive at 10.8 per cent and 8.8 per cent of NII for PSBs and PVBs, respectively for a 200 bps increase in interest rate. The impact would be marginal for FBs and SFBs in case of a 200 bps increase in interest rate (Table 2.8). The impact of increase in interest rate on earnings is positive as the cumulative gap28 at bank group level was positive as of March 2023. 2.39 DGA29 reveals that PVBs’ and FBs’ Market Value of Equity (MVE) would reduce marginally in case of an upward movement in interest rate, while that of PSBs would be positively impacted. SFBs’ MVE would be particularly weighed down by an upward movement of interest rate (Table 2.9). e. Equity Price Risk 2.40 As banks have limited capital market exposures owing to regulatory limits, any impact of a possible significant fall in equity prices on banks’ CRAR would be limited for the overall system of 46 banks. Under scenarios of 25 per cent, 35 per cent and 55 per cent drop in equity prices, the system level CRAR would reduce by 21 bps, 29 bps and 45 bps, respectively (Chart 2.19). f. Liquidity Risk 2.41 Liquidity risk analysis aims to capture the impact of any possible run on deposits and increased demand for unutilised portions of sanctioned / committed / guaranteed credit lines. In an extreme scenario of sudden and unexpected withdrawals of around 15 per cent of un-insured deposits along with the utilisation of 75 per cent of unutilised portion of committed credit lines, liquid assets30 at the system-level would decrease from 21.1 per cent of total assets to 11.4 per cent (Chart 2.20).  II.1.8 Bottom-up stress tests - Credit, Market and Liquidity Risk 2.42 A suite of bottom-up stress tests (sensitivity analyses) for select banks31 for end March 2023 position affirmed the resilience of banks to multiple types and magnitude of shocks, broadly in line with the top-down stress test results. All the sample banks covered meet the regulatory minimum capital requirements under diverse shock scenarios. Under a credit risk shock of 50 per cent rise in NPAs as well as under the impact of an interest rate shock of a parallel upward shift in the sovereign yield curve by 2.5 percentage points on the banking book, two banks may breach the regulatory minimum CRAR inclusive of the CCB (Chart 2.21).   2.43 The bottom-up stress test for liquidity risk reveals that liquid assets ratios32 of all the sample banks would remain positive under different shock scenarios, emphasising the adequacy of their high quality liquid assets (HQLAs) to withstand any plausible liquidity pressure from sudden and unexpected withdrawal of deposits. Under the scenarios of (i) a 10 per cent deposit run-off in 1-2 days and (ii) a 3 per cent deposit run-off daily for five consecutive days, the average liquid asset ratios of the select banks would drop from 24.1 per cent to 17.7 per cent and 14.1 per cent, respectively (Chart 2.22). II.1.9 Bottom-up Stress Tests: Derivatives Portfolio 2.44 A series of bottom-up stress tests (sensitivity analyses) are undertaken on derivative portfolios of select banks33 with the reference date of March 31, 2023. Four separate shocks on interest and foreign exchange rates are simulated. While the shocks on interest rates range from 100 to 250 basis points, shocks of 20 per cent appreciation/ depreciation are assumed in the case of foreign exchange rates. The stress tests are carried out as individual shocks on a stand-alone basis. 2.45 Most of the FBs have significantly negative net MTM positions (as a proportion to CET1 capital) in March 2023, whereas the impact is, by and large, muted for PSBs and PVBs. For the overall system, the extent of negative MTM position increased slightly in Q4:2022-23 (Chart 2.23). 2.46 On an average, the derivative portfolios of the sample banks are positioned to gain from an interest rate rise and vice versa. Potential MTM gains from a rise in interest rates increased in March 2023 relative to September 2022. Contrary to interest rate shocks, sample banks are positioned to make gains from foreign exchange rate shocks (for both appreciation and depreciation) – which is similar to the position in September 2022, except that the potential gains have increased (Chart 2.24).   II.2 Primary (Urban) Cooperative Banks34 2.47 Credit growth (y-o-y) of primary urban cooperative banks (UCBs)35 increased from 3.4 per cent in September 2022 to 5.7 per cent in March 2023 (Chart 2.25 a). Both scheduled UCBs (SUCBs) and non-scheduled UCBs (NSUCBs) contributed to this pick-up, with their credit growth reaching 6.7 per cent and 4.9 per cent, respectively. Priority sector lending (PSL) by both SUCBs and NSUCBs stood at arround 65 per cent of their outstanding credit on March 31, 2023 (Chart 2.25 b). The dates to achieve PSL targets of minimum 60, 65 and 75 per cent have been extended upto March 31, 2024, March 31, 2025 and March 31, 2026 respectively36. 2.48 The Reserve Bank has adopted a four-tiered regulatory framework for categorisation of UCBs37, given the heterogeneity in the sector. In March 2023, Tier 4 UCBs (having deposits more than ₹10,000 crore) had a share of 24.2 per cent in total gross loans of UCBs as against a share of 14.5 per cent for Tier 1 UCBs, 27.5 per cent for Tier 2 UCBs and 33.7 per cent for Tier 3 UCBs.  2.49 The CRAR of UCBs improved marginally in H2:2022-23 to reach 16.5 per cent in March 2023. The CRAR of SUCBs remained stable at around 15 per cent and that of NSUCBs improved from 17.1 per cent to 17.8 per cent (Chart 2.25 c). The tier-wise CRAR of UCBs stands well above the minimum regulatory requirement38, which came into effect from March 31, 2023 (Chart 2.25 d). 2.50 After a deterioration in H1:2022-23, GNPA and NNPA ratios of UCBs have improved for both SUCBs and NSUCBs in March 2023 (Charts 2.25 e and f). There was an improvement in the provisioning coverage ratio (PCR) of NSUCBs and SUCBs (Chart 2.25 g). Tier 4 UCBs had the best asset quality with the lowest GNPA ratio and NNPA ratio (Chart 2.25 h). 2.51 Profitability of UCBs in terms of RoA and RoE ratios lost pace in H2:2022-23 even as their NIMs increased in March 2023 (Chart 2.25 i, j and k). Tier 2 UCBs had the highest NIM while Tier 1 and Tier 3 UCBs had the highest RoA and RoE, respectively (Chart 2.25 l). Tier 4 UCBs lagged in all profitability parameters.   II.2.1 Stress Testing 2.52 Stress tests were conducted on a select set of larger UCBs39 to assess credit risk (default risk and concentration risk), market risk (interest rate risk in trading book and banking book) and liquidity risk, based on their reported financial positions as on March 2023. 2.53 The results show that (a) in almost all the five parameters tested, a few UCBs failed even in the baseline scenario; (b) the impact of credit default risk is higher than other types of risk in all the three scenarios; (c) the impact of a shock to the trading book is low and (d) resilience has improved in general as compared with the position half a year ago (Chart 2.26). Under a severe stress scenario, the consolidated CRAR of SUCBs and NSUCBs diminishes by 194 bps and 345 bps, respectively, for credit default risk and by 341 bps and 320 bps, respectively, for credit concentration risk. Similarly, consolidated net interest income (NII) of SUCBs and NSUCBs declines by around 8.0 per cent and 11.5 per cent, respectively, under the severe stress scenario for interest rate risk in the banking book. Under all the three scenarios, the system level impact on CRAR is below 65 bps for interest rate risk on the trading book and the system level liquidity mismatch remains positive (no liquidity gap) for liquidity risk. II.3 Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs)40 2.54 After reaching double digits in September 2022, annual growth of credit disbursed by NBFCs sustained pace, with personal loans rising by 31.3 per cent and loans to industry by 12.7 per cent (y-o-y) in March 2023 (Chart 2.27). The personal loans portfolio of NBFCs grew the most during the last four-year period {compound annual growth rate (CAGR) being more than 30 per cent} resulting in increase of its share in total loan portfolio to 31.2 per cent in March 2023. As per the activity-based classification, the largest two categories, namely, investment and credit company (NBFC-ICC) and infrastructure finance company (NBFC-IFC), with shares of 54 per cent and 40 per cent, respectively, in outstanding credit registered double digit credit growth in March 2023. Micro finance institutions (NBFC-MFIs) have maintained robust credit growth over the past two years (with a CAGR 27.6 per cent).   2.55 The GNPA ratio of NBFCs continued to decline during H2:2022-23, with industry and services each registering more than two percentage points reduction (Chart 2.28). Public sector NBFCs (with a share of 44 per cent in outstanding credit) had low GNPA ratios (2.8 per cent) relative to their private counterparts (credit share 56 per cent and GNPA ratio 5.5 per cent). The aggregate NNPA ratio of NBFCs ebbed further to 1.3 per cent, with the provisioning coverage ratio (PCR) increasing to 70.4 per cent in March 2023 (Chart 2.29) 2.56 The capital position of NBFCs remained robust, with CRAR at 27.5 per cent in March 2023, much above the minimum requirement of 15 per cent. The RoA recouped gradually to reach 3.3 per cent by end 2022-23 (Chart 2.30). 2.57 Share capital, reserves and surplus of NBFCs increased over the years, contributed mostly by capital reserves and balances in profit and loss accounts. On the other hand, their share of total borrowings in total funds reduced from 66.4 per cent in March 2020 to 62.3 per cent in March 2023 mostly due to lower issuance of debentures by NBFCs than other sources of funds during the period. Around two-thirds of borrowings were long-term (more than one year) in nature. NBFCs’ borrowing from banks increased in 2022-23 (Table 2.10).    2.58 NBFCs in the Upper Layer (NBFC-UL) recorded healthy growth in 2022-23, with robust capital positions and improved GNPA ratios (Table 2.11). II.3.1 Stress Test41 - Credit Risk 2.59 System level stress tests for assessing the resilience of the NBFC sector to credit risk shocks were conducted for a sample of 13542 large NBFCs. The tests were carried out under a baseline and two stress scenarios – medium and high risk, with increases in the slippage ratio by 1 SD and 2 SDs, respectively. The capital adequacy ratio of the sample NBFCs in March 2023 stood at 25.0 per cent and the GNPA ratio at 3.4 per cent. The baseline scenario is projected for one year ahead, based on assumptions of business continuing under usual conditions. 2.60 Under the baseline scenario, the one-year ahead GNPA ratio is assessed at 4.1 per cent and CRAR at 24.4 per cent. Under a medium risk shock of 1 SD increase in the slippage ratio, the GNPA ratio increases to 5.5 per cent and the resultant income loss and additional provisional requirements reduce the CRAR by 60 bps relative to the baseline. Under the high-risk shock of 2 SDs, the capital adequacy ratio of the sector declines by 90 bps relative to the baseline to 23.5 per cent. The number of NBFCs that would fail to meet the minimum regulatory capital requirement of 15 per cent increases from three under the baseline scenario to five under medium and severe stress scenarios, respectively (Chart 2.31). II.3.2 Stress Test - Liquidity Risk 2.61 The resilience of the NBFC sector to liquidity shocks has been assessed by capturing the impact of a combination of assumed increase in cash outflows and decrease in cash inflows43. The baseline scenario uses the projected outflows and inflows as of March 2023. One baseline and two stress scenarios are applied – a medium risk scenario involving 5 per cent contraction in inflows and 5 per cent rise in outflows; and a high-risk scenario entailing a shock of 10 per cent decline in inflows and 10 per cent surge in outflows. The results indicate that the number of NBFCs, which would face negative cumulative mismatch in liquidity over the next one year in the baseline, medium and high-risk scenarios stood at 7 (representing 1.2 per cent of asset size of the sample), 24 (11.3 per cent) and 24 (11.3 per cent), respectively (Table 2.12).  2.62 The solvency ratio of an insurance company assesses its ability to meet obligations towards policyholders by reflecting the level of its assets over and above its liabilities. As the insurance liabilities involve estimations about the future experience of contingent events, a higher solvency ratio implies a higher resilience of the insurer to withstand the uncertainties of the future. The minimum solvency ratio requirement prescribed by Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) for Indian insurance companies is 150 per cent. 2.63 Solvency ratio for life insurance companies has been above the prescribed threshold for both public sector and private sector at an aggregate level (Table 2.13). Solvency ratio for public sector non-life insurance companies is sub-optimal with three of the four PSU insurers having solvency ratio below the baseline prescription (Table 2.14).

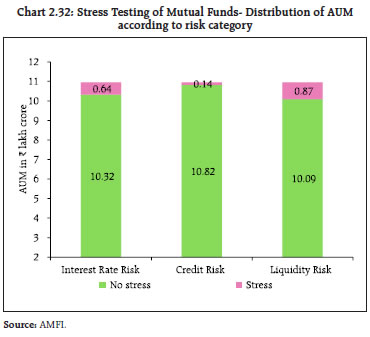

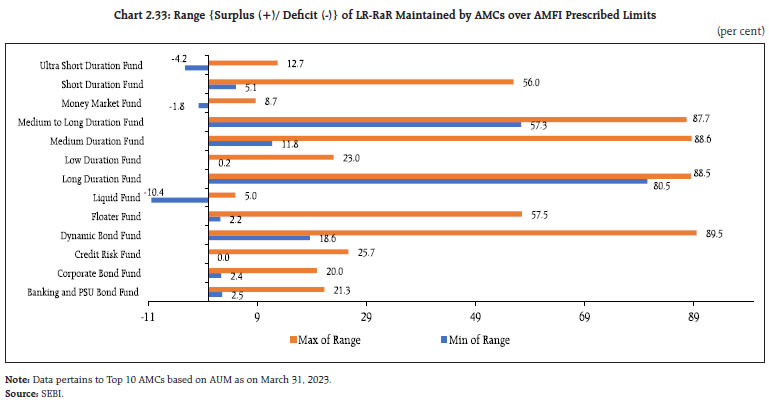

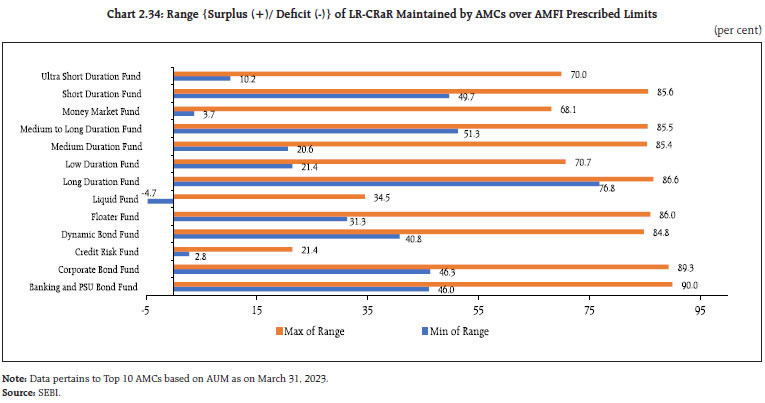

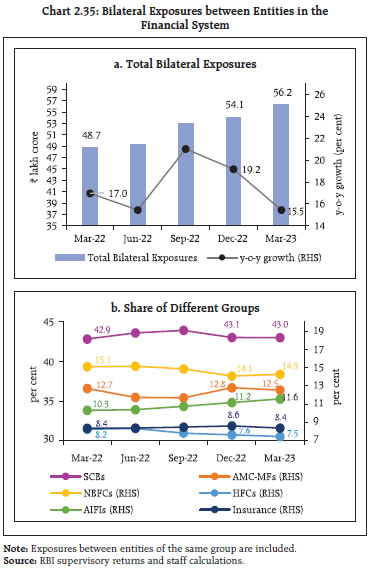

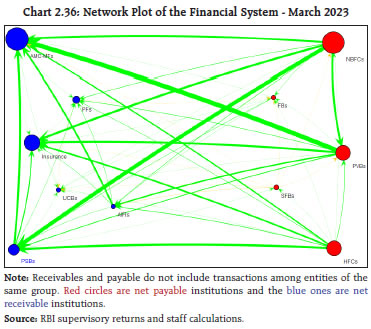

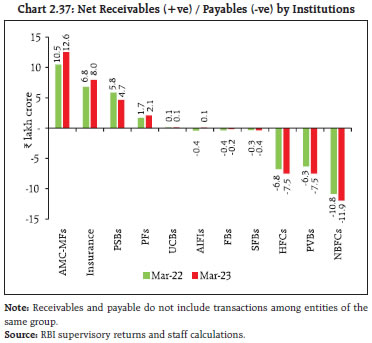

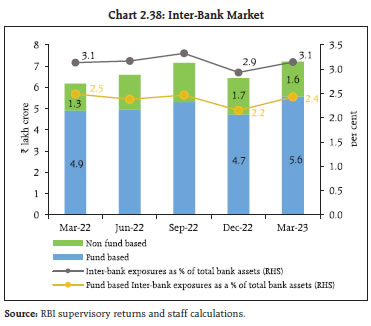

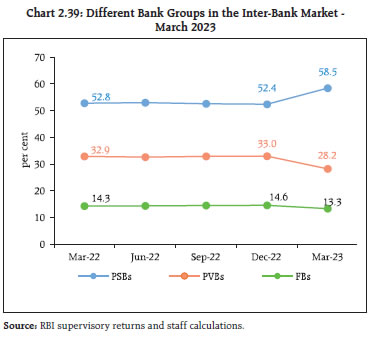

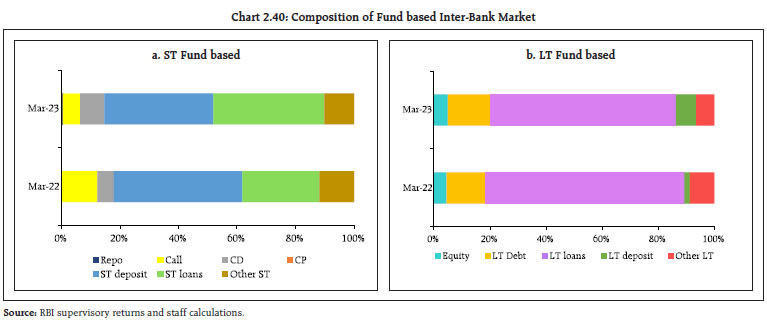

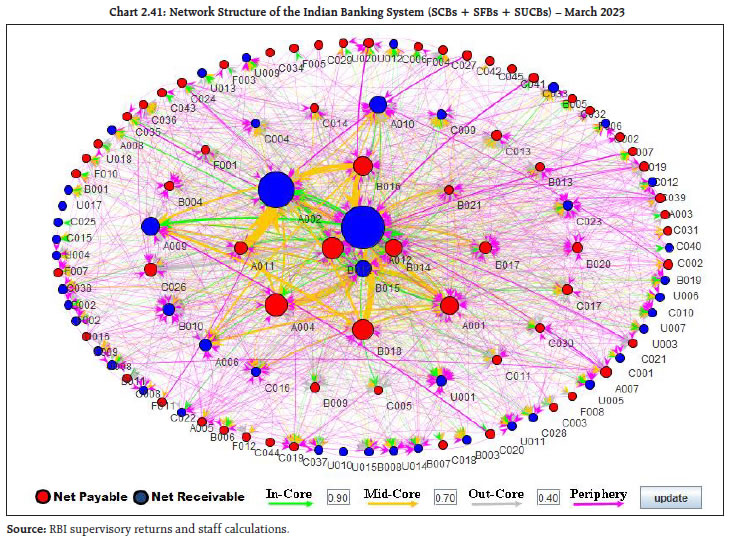

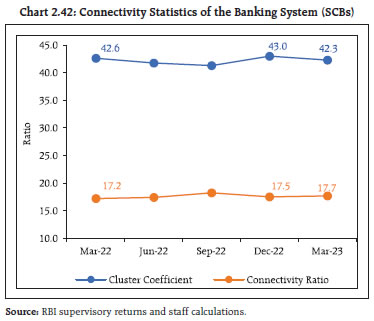

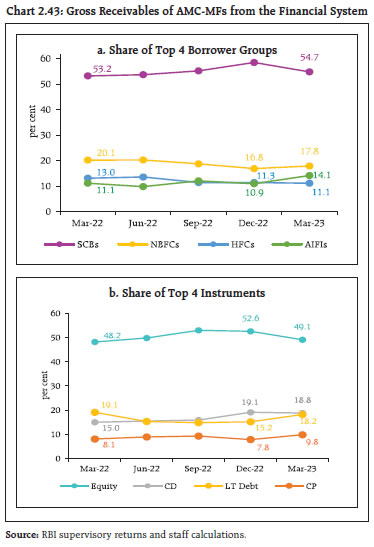

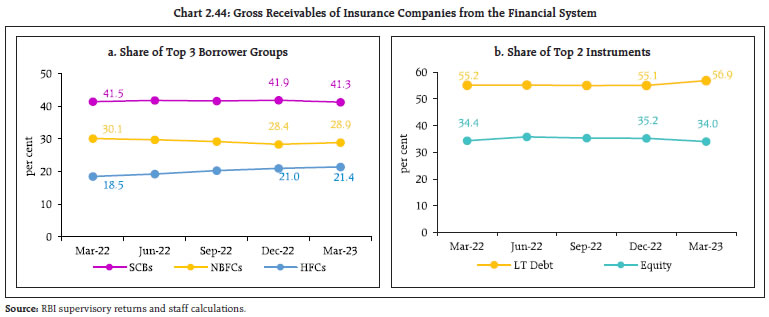

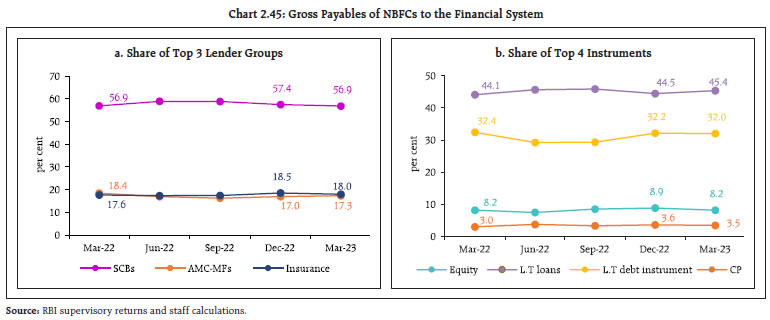

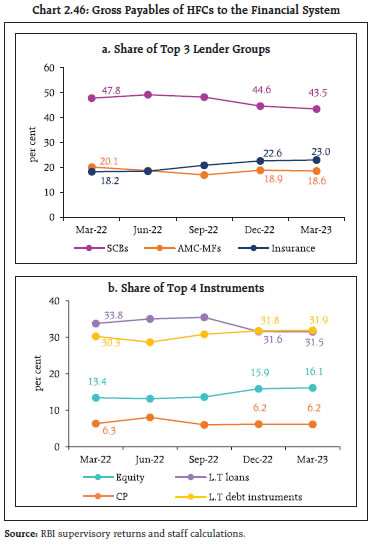

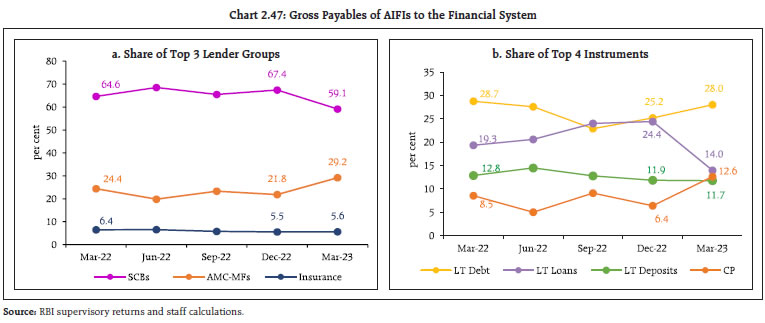

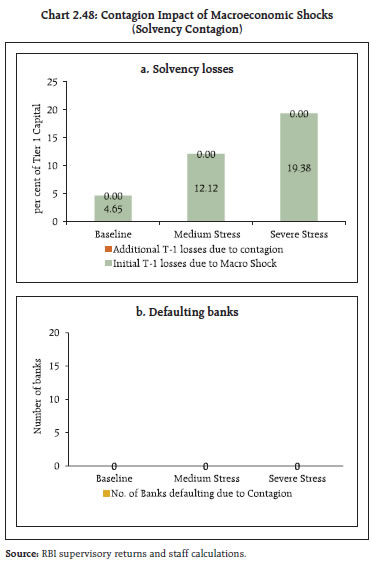

II.5 Stress testing of Mutual Funds 2.64 As mandated by the SEBI, the stress testing of all open-ended debt schemes (except overnight schemes) is carried out by asset management companies (AMCs) every month to evaluate the impact of various risk parameters, viz., interest rate risk, credit risk, liquidity risk and redemption risk faced by such schemes on their net asset values (NAVs). 2.65 The stress testing analysis carried out for all open-ended debt schemes (except overnight funds, gilt funds and gilt funds with 10-year constant duration) by all mutual funds for March 2023 revealed stress (credit risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk) in the case of 14 mutual funds. In terms of schemes, however, only 24 out of a total of 295 schemes exhibited stress. The assets under management (AUM) of the open-ended debt schemes, which were found to have experienced stress, amounted to ₹1.08 lakh crore, as against the total AUM of ₹10.95 lakh crore for all schemes for which the stress testing was conducted (Table 2.15). The AUM of the open-ended debt schemes, which experienced stress on account of liquidity risk, interest rate risk and credit risk amounted to ₹0.87 lakh crore, ₹0.64 lakh crore and ₹0.14 lakh crore, respectively (Chart 2.32). 2.66 Furthermore, as a part of liquidity risk management for open-ended debt schemes, two types of liquidity ratios, viz., (i) redemption at risk (LR-RaR), which represents likely outflows at a given confidence interval, and (ii) conditional redemption at risk (LR-CRaR), which represents the behaviour of the tail at the given confidence interval, are being used. All the AMCs have been mandated to maintain these liquidity ratios (LR-RaR and LR-CRaR) above the threshold limits, which are derived from scheme type, scheme asset composition and potential outflows (modelled from investor concentration in the scheme). Mutual funds are required to carry out backtesting of these liquidity ratios for all open-ended debt schemes (except overnight funds, gilt funds and gilt funds with 10-year constant duration) on a monthly basis.   2.67 The LR-RaR and LR-CRaR computed by top 10 mutual funds (based on AUM) for 13 categories of open-ended debt schemes for April 2023 were well above the respective threshold limits for most of the mutual funds. In the few instances, in which the ratios were below the threshold limits, they were addressed by the respective AMCs in a timely manner (Chart 2.33 and Chart 2.34).  II.6 Stress Testing Analysis at Clearing Corporations 2.68 Stress testing is carried out at clearing corporations (CCs) to determine the minimum required corpus (MRC) of the core settlement guarantee fund (SGF). The segment-wise MRC is determined on a monthly basis using stress testing. For determining the MRC for cash and equity derivatives segment, the CC calculates the credit exposure arising out of a presumed simultaneous default of top two clearing members (CMs). The credit exposure for each CM is determined by assessing the close out loss arising out of closing open positions (under stress testing scenarios) and the net pay in/pay out requirement of the CM against the required margins and other mandatory deposits of the CM. Further, MRC of the month is determined as average of all daily worst case loss scenarios for the month. The actual MRC for any given month is determined as the higher of the MRC for the month and the MRC arrived at any time in the past. 2.69 Based on the stress testing analysis during the period November 2022 – March 2023, it is observed that though the monthly calculated amounts of MRC (cash segment) at a major clearing corporation on the basis of changes in credit exposures of CMs varied, the actual MRC requirement (cash segment) remained the same during the same period in line with the SEBI’s stipulation. The MRC requirement in the equity derivatives segment increased during the period (Table 2.16). 2.70 A financial system can be visualised as a network with financial institutions as nodes and bilateral exposures as links joining these nodes. These links could be in the form of loans to, investments in, or deposits with each other, which act as a source of funding, liquidity, investment and risk diversification. While these links enable efficiency gains and risk diversification, they can become conduits of risk transmission in case of a crisis. Understanding the nuances in propagation of risk through networks is useful for devising appropriate policy responses for safeguarding financial and macroeconomic stability. II.7.1 Financial System Network44 45 2.71 The total outstanding bilateral exposures46 among the entities in the Indian financial system continued to grow during the half-year ended March 2023. A major part of the surge emanated from higher funding requirements of all India financial institutions (AIFIs), SCBs and NBFCs (Chart 2.35 a). The increase during H2:2022-23 was primarily driven by increasing exposure of asset management company-mutual funds (AMC-MFs) and AIFIs to SCBs. 2.72 SCBs continued to have the largest bilateral exposures in the Indian financial system, although their share declined from 43.9 per cent in September 2022 to 43.0 per cent in March 2023. SCBs’ share as fund provider to the system reduced during 2022-23, whereas their share in borrowing from entities (including other SCBs) increased. The factors leading to SCBs increasingly relying on borrowing from the market include credit growth outpacing deposit expansion and lower surplus liquidity at system level. On a sequential basis, the shares of NBFCs and AIFIs increased, while the shares of AMC-MFs, insurance companies and HFCs declined (Chart 2.35 b). 2.73 In terms of inter-sectoral exposures47, AMC-MFs, insurance companies and PSBs were the biggest fund providers in the system, whereas NBFCs and PVBs were the largest receivers of funds, followed by HFCs. Among bank groups, PSBs and UCBs had net receivable positions vis-à-vis the entire financial sector whereas FBs, PVBs and SFBs had net payable positions (Chart 2.36).   2.74 The trend of the net receivables/payables position from March 2022 to March 2023 indicates that the declining share of PSBs in providing fund to the borrowing institutions in the system (primarily NBFCs, PVBs and HFCs) was being taken over by AMC-MFs and insurance companies (Chart 2.37). a. Inter-Bank Market 2.75 Inter-bank exposures accounted for 3.1 per cent of the total assets of the banking system in March 2023, with fund-based exposure constituting the major part (2.4 per cent). In absolute terms, the fund-based48 and non-fund-based exposures49 varied sequentially (Chart 2.38).   2.76 The rise in borrowing and lending by PSBs and lower lending by PVBs in the inter-bank markets contributed to an increase in the share of PSBs and a decline in the share of PVBs during Q4:2022-23 (Chart 2.39). 2.77 About 75 per cent of the fund-based inter-bank market was short-term (ST) in nature, in which ST deposits and ST loans constituted over 75 per cent, followed by certificates of deposit (CDs) and call money market exposure. Although long-term (LT) loans predominated in LT fund-based inter-bank exposures, their share declined during the latest quarter (Chart 2.40). b. Inter-Bank Market: Network Structure and Connectivity 2.78 The inter-bank market typically has a core-periphery network structure50 51. As of end-March 2023, four banks were in the inner-most core and eight banks in the mid-core circle. The four banks in the inner-most core included one large public and three private sector banks. The banks in the mid-core were PSBs and PVBs. Most of the old PVBs along with FBs, SUCBs and SFBs formed the periphery (Chart 2.41).    2.79 The degree of interconnectedness in the banking system (SCBs), as measured by the connectivity ratio52, reduced during H2:2022-23 partly due to inclusion of an additional foreign bank in the analysis and reduction in number of net payable connections of PVBs. Further, the cluster coefficient53 also varied marginally during the period from March 2022 to March 2023 (Chart 2.42).  c. Exposure of AMCs-MFs 2.80 Gross receivables of AMC-MFs stood at ₹13.29 lakh crore whereas their gross payables were ₹0.73 lakh crore as at end-March 2023. SCBs continued to be the major recipients of their funding, followed by NBFCs, AIFIs and HFCs (Chart 2.43 a). 2.81 In the asset composition of AMC-MFs, the share of equity holdings continued to maintain a dominant position while the share of CDs and CPs increased on a y-o-y basis (Chart 2.43 b). d. Exposure of Insurance Companies 2.82 Gross receivables of insurance companies stood at ₹8.49 lakh crore and gross payables at ₹0.50 lakh crore in March 2023. SCBs (primarily PVBs) were the largest recipients of their funds, followed by NBFCs and HFCs. Insurance companies hold over 90 per cent of their assets in the form of LT debt and equity (Chart 2.44 a and b). e. Exposure to NBFCs 2.83 NBFCs were the largest net borrowers of funds from the financial system, with gross payables of ₹13.68 lakh crore and gross receivables of ₹1.74 lakh crore as at end-March 2023. Their largest exposure was in terms of their borrowings from SCBs, although it came down in Q4:2022-23, whereas their borrowings from AMC-MFs increased (Chart 2.45 a). Instrument wise, more than 75 per cent of payables of NBFCs were in the form of LT Loans and LT debt instruments, followed by equity capital (Chart 2.45 b).    f. Exposure to HFCs 2.84 HFCs remained net borrowers and had gross payables of ₹7.93 lakh crore against gross receivables of ₹0.44 lakh crore at end-March 2023. As in the case of NBFCs, the declining share of SCBs funding to HFCs during H2:2022-23 is attributed to AMC-MFs and insurance companies (Chart 2.46 a). Over 60 per cent of HFCs’ resource mobilisation was through LT loans and LT debt instruments. (Chart 2.46 b). g. Exposure of AIFIs 2.85 AIFIs were net provider of funds to the financial system, with their gross payables and gross receivables being ₹6.43 lakh crore and ₹6.52 lakh crore, respectively, in March 2023. They raised funds mainly from SCBs (primarily PVBs), AMC-MFs and insurance companies; their borrowings from PVBs declined due to decrease in long-term loans (Chart 2.47 a). Given their nature of operations, LT Loans, LT debt and LT deposits remained their preferred instruments for raising funds but the combined share of these instruments has declined to 53.7 per cent from 60.9 per cent a year ago (Chart 2.47 b).   II.7.2 Contagion Analysis 2.86 Contagion analysis uses network technology to estimate the systemic importance of different banks. The failure of a bank, which is systemically important leads to greater solvency and liquidity losses for the banking system, which, in turn, depends on the initial capital and liquidity position of banks along with the number, nature (whether it is a lender or a borrower) and magnitude of the interconnections that the failing bank has with the rest of the banking system. a. Joint Solvency54- Liquidity55 Contagion Losses for SCBs due to Bank Failure 2.87 A contagion analysis of the banking network based on the end-March 2023 position indicates that if the bank with the maximum capacity to cause contagion losses fails, it will cause a solvency loss of 2.22 per cent (as compared to 2.49 per cent in September 2022) of total Tier 1 capital of SCBs and liquidity loss of 0.25 per cent (as compared to 0.31 per cent in September 2022) of total HQLA of the banking system. The analysis also shows that contagion losses due to failure of the five banks with the maximum capacity to cause contagion losses decreased in March 2023 vis-à-vis September 2022 and would not lead to failure of any additional bank (Table 2.17). b. Solvency Contagion losses for SCBs due to NBFC/HFC failure 2.88 As noted earlier, NBFCs and HFCs are the largest borrowers of funds from the financial system. A substantial part of their funding comes from banks. Therefore, failure of any NBFC or HFC will act as a solvency shock to their lenders, which can spread through contagion. 2.89 By end-March 2023, idiosyncratic failure of the NBFC with the maximum capacity to cause solvency losses to the banking system would have knocked off 2.51 per cent (2.63 per cent in September 2022) of the latter’s total Tier 1 capital but it would not have led to failure of any bank as funding from banks to NBFCs/HFCs has come down and banks are also better capitalised. Similarly, failure of the HFC with the maximum capacity to cause solvency losses to the banking system would have knocked off 4.42 per cent (5.90 per cent in September 2022) of the latter’s total Tier 1 capital but without failure of any bank (Tables 2.18 and 2.19). c. Solvency Contagion Impact56 after Macroeconomic Shocks to SCBs 2.90 Any contagion from failure of a bank is likely to get magnified if macroeconomic shocks result in distress to the banking system. In such a situation, similar shocks may cause some SCBs to fail the solvency criterion, which then acts as a trigger for further solvency losses. 2.91 In the previous iteration, the shock was applied to the entity that could cause the maximum solvency contagion losses. In another iteration, in which the initial impact of such a shock on an individual bank’s capital is taken from the macro stress tests57, the initial capital loss due to macroeconomic shocks stood at 4.65 per cent, 12.12 per cent and 19.38 per cent of Tier I capital for baseline, medium and severe stress scenarios, respectively. No bank fails to maintain Tier I capital adequacy ratio of 7 per cent in any of the scenarios. As a result, there are no additional solvency losses to the banking system due to contagion (over and above the initial loss of capital due to the macro shocks) (Chart 2.48 a and b). Summary and Outlook 2.92 Stable financial conditions, balance sheet strength and return to profitability on the back of surge in net interest income (NII) has enabled the Indian banking system to support the growing credit needs of the economy. Capital position and asset quality of SCBs, UCBs and NBFCs have improved further during H2:2022-23. Though credit growth has outpaced the rise in deposits over the last one year, both are growing in double digits. 2.93 Macro stress tests indicate that SCBs have sufficient capital buffers to withstand moderate to severe adverse macroeconomic circumstances, though some individual banks may fall short of minimum capital requirements (including the CCB), under a severe stress scenario. An extreme scenario of a 250 bps upward movement in the yield curve may bring down the CRAR of a few banks below the regulatory minimum level. Network analysis indicates that contagion risks and consequent additional solvency losses have reduced since the last issue of the FSR. There would be no additional solvency losses to the banking system from contagion due to macroeconomic shocks. 2.94 As global financial conditions and the geopolitical situation remain highly uncertain, the Indian financial system needs to adopt a nimble and pre-emptive approach to ward off any signs of incipient stress that appear in early warning indicators, maintain soundness and public confidence and meet the financing requirements of India’s developmental aspirations.  1 Analyses are mainly based on RBI’s supervisory returns, which cover only domestic operations of SCBs, except in the case of data on large borrowers, which are based on banks’ global operations. For this exercise, SCBs include public sector banks, private sector banks and foreign banks. For CRAR projections, a sample of 46 SCBs accounting for around 98 per cent of the assets of the total banking sector, excluding regional rural banks (RRBs) and co-operative banks, have been considered. 2 Due to changes in the methodology for supervisory reporting, data on sectoral/ sub-sectoral advances presented in Charts 2.1 (d), (e) and (f) may not be comparable to past periods. For these charts, FBs group comprises of six major foreign banks with an approx. 71 per cent share in total gross loans and advances of all FBs as on March 2023. 3 The analyses done in the chapter are based on the data available as of June 15, 2023, which are provisional. 4 Personal loans refer to loans given to individuals and consist of (a) consumer credit (b) education loan (c) loans given for creating/enhancement of immovable assets (e.g. housing, etc.) and (d) loans given for investment in financial assets (shares, debentures, etc.) 5 NNPA ratio is the proportion of net non-performing assets in net loans and advances. 6 PCR is the proportion of provisions (without write-offs) held for NPAs to GNPA. 7 Ratio of write-off (including technical/ prudential write-offs and compromise settlement) during the period to GNPA at the beginning of the period. 8 A large borrower is defined as one who has aggregate fund-based and non-fund-based exposure of ₹5 crore and above. This analysis is based on SCBs’ global operations. 9 a) Loans in the nature of revolving facilities like cash credit/overdraft: if outstanding balance remains continuously in excess of the sanctioned limit or drawing power, whichever is lower, for a period of 31-60 days - SMA-1 ;61-90 days - SMA-2. 10 Tier I leverage ratio is the ratio of Tier I capital to total exposure. 11 The adverse scenarios are stringent conservative assessments under hypothetical adverse economic conditions and model outcomes should not be interpreted as forecasts. 12 In comparison, a similar study done by Bank Negara Malaysia covered personal loans as well, that represented about 20 per cent of the total household debt. 13 Source Basic Statistical Returns-1, Database on Indian Economy. 14 Households are bucketed based on income net of tax. Only households falling in the tax bracket have been considered. 15 Calculated as weighted average of the rates of interest with loan size as weights. 16 Under macro stress tests, the shocks are in terms of adverse macroeconomic conditions, while in sensitivity analyses, shocks are applied to single factors like GNPA, interest rate, equity prices, deposits, and the like, one at a time. Also, macro stress tests for GNPA ratios are applied at the system and major bank-group levels, whereas the sensitivity analyses are conducted at system and individual bank levels. 17 Top-down stress tests are based on specific scenarios and on aggregate bank-wise data. 18 Single factor sensitivity analysis stress tests are conducted for a sample of 46 SCBs accounting for 98 per cent of the total assets of the banking sector. The shocks designed under various hypothetical scenarios are extreme but plausible. 19 The SD of the GNPA ratio is estimated by using quarterly data for the last 10 years. One SD shock approximates a 61.2 per cent increase in the level of GNPA ratio. 20 In the case of default, the borrower in the standard category is considered to move to the sub-standard category. 21 In the case of default, the group borrower in the standard category is considered to move to the sub-standard category. 22 In case of failure, the borrower in sub-standard or restructured category is considered to move to the loss category. 23 PV01 is a measure of sensitivity of the absolute value of the portfolio to a one basis point change in the interest rate. 24 State of the Economy, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, May 2023. 25 The curvature is calculated as twice the 14-year yield minus the sum of 30-year and 3-month yields. 26 Patra, M.D., Joice, J., Kushwaha, K.M., and I. Bhattacharyya (2022), “What is the Yield Curve telling us about the Economy?”, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, June. 27 In terms of circular on “Guidelines on Banks’ Asset Liability Management Framework – Interest Rate Risk” dated November 04, 2010. 28 Gap refers to Rate Sensitive Assets (RSA) minus Rate Sensitive Liabilities (RSL). Advances, HTM investments, swaps/forex swaps, reverse repos are major contributors to RSA whereas deposits, swaps /forex swaps and repos are observed to be the main elements under RSL. 29 The DGA involves bucketing of all RSA and RSL as per residual maturity/ re-pricing dates in various time bands and computing the Modified Duration Gap (MDG). 30 Liquid assets were computed as cash reserves in excess of required CRR, excess SLR investments, SLR investments at 2 per cent of NDTL (under MSF) (following the Circular DOR.RET.REC.73/12.01.001/2021-22 dated December 10, 2021) and additional SLR investments at 16 per cent of NDTL (following the Circular DOR.LRG.REC.No.19/21.04.098/2022-23 dated April 18, 2022). 31 Stress tests on various shocks were conducted by a sample of 22 select banks.  33 Stress tests on derivatives portfolios were conducted by a sample of 21 banks, constituting the major active authorised dealers and interest rate swap counterparties. Details of test scenarios are given in Annex 2. 34 Data are provisional and based on off-site surveillance (OSS) returns. The data from March 2022 onwards excludes one UCB, which was amalgamated with an SFB. 35 Based on common sample of 1457 UCBs covering over 90 per cent of gross loans extended by UCBs. 36 Priority Sector Lending (PSL) targets / sub-targets and contribution against shortfall in achievement of PSL targets – Primary (Urban) Co-operative Banks (UCBs) - Extension of time (Circular DOR.CRE.REC.18/07.10.002/2023-24 dated June 08, 2023). 37 Revised Regulatory Framework - Categorisation of Urban Co-operative Banks (UCBs) for Regulatory Purposes (Circular DOR. REG. No.84/07.01.000/2022-23 dated December 01, 2022). 38 Revised Regulatory Framework for Urban Co-operative Banks (UCBs) – Net Worth and Capital Adequacy (circular DOR.CAP.REC.No.86/09.18.201/2022-23 dated December 01, 2022 and DOR.CAP.REC. No.109/09.18.201/2022-23 dated March 28, 2023). 39 The stress test is conducted with reference to the financial position of March 2023 for select 100 UCBs (43 SUCBs, 57 NSUCBs) with asset size of more than ₹1,000 crore, excluding three banks under the Reserve Bank’s All Inclusive Directions (AID). These 100 UCBs together cover 57 per cent of the total assets of the UCB sector as on March 2023. The detailed methodology used for stress test is given in Annex 2. 40 The analyses done in this section are based on deposit taking and non-deposit taking systemically important NBFCs’ (including CICs) data available as of June 15, 2023 which are provisional. 41 The detailed methodology used for stress tests for NBFCs is given in Annex 2. 42 The sample comprised of 9 NBFCs in Upper Layer and 126 NBFCs in Middle Layer with total advances of ₹17.36 lakh crore as of March 2023, which forms around 91 per cent of total advances of non-Government NBFCs in the sector. The sample for stress test excluded Government NBFCs, companies presently under resolution and investment focused companies. 43 Stress testing based on liquidity risk was performed on a sample of 207 NBFCs – which includes 10 NBFCs in Upper Layer, 180 NBFCs in Middle Layer and 17 NBFCs in Base Layer. The total asset size of the sample was ₹25.42 lakh crore, comprising 81.7 per cent of total assets of non-government NBFCs in the sector. 44 The network model used in the analysis had been developed by Professor Sheri Markose (University of Essex) and Dr.Simone Giansante (Bath University) in collaboration with the Financial Stability Department, Reserve Bank of India. 45 Analysis presented here and in the subsequent part is based on data of 230 entities from the following eight sectors: SCBs, scheduled UCBs (SUCBs), AMC-MFs, NBFCs, HFCs, insurance companies, pension funds and AIFIs. These 230 entities covered include 78 SCBs; 12 small finance banks (SFBs), 20 SUCBs; 25 AMC-MFs (which cover more than 98 per cent of the AUMs of the mutual fund sector); 40 NBFCs (both deposit taking and non-deposit taking systemically important companies, which represent about 70 per cent of total NBFC assets); 22 insurance companies (that cover more than 95 per cent of assets of the sector); 18 HFCs (which represent more than 95 per cent of total HFC asset); 10 PFs and 5 AIFIs (NABARD, EXIM, NHB, SIDBI and NaBFID). 46 Includes exposures between entities of the same group. Exposures are outstanding position as on March 31, 2023 and are broadly divided into fund-based and non-fund-based exposure. Fund-based exposure includes money market instruments, deposits, loans and advances, long term debt instruments and equity investments. Non-fund- based exposure includes letter of credit, bank guarantee and derivate instruments (excluding settlement guaranteed by Clearing Corporation of India Limited). 47 Inter-sectoral exposures do not include transactions among entities of the same sector in the financial system. 48 Fund-based exposures include both short-term exposures and long-term exposures. Data on short-term exposures are collected across seven categories – repo (non-centrally cleared); call money; commercial paper; certificates of deposits; short-term loans; short-term deposits and other short-term exposures. Data on Long-term exposures are collected across five categories – Equity; Long-term Debt; Long-term loans; Long-term deposits and Other long-term liabilities. 49 Non-Fund based exposure includes - outstanding bank guarantees, outstanding Letters of Credit, and positive mark-to-market positions in the derivatives market (except those exposures for which settlement is guaranteed by the CCIL). 50 The diagrammatic representation of the network of the banking system is that of a tiered structure, in which different banks have different degrees or levels of connectivity with others in the network. The most connected banks are in the inner-most core (at the centre of the network diagram). Banks are then placed in the mid-core, outer core and the periphery (concentric circles around the centre in the diagram), based on their level of relative connectivity. The colour coding of the links in the tiered network diagram represents borrowings from different tiers in the network (for example, the green links represent borrowings from the banks in the inner core). Each ball represents a bank and they are weighted according to their net positions vis-à-vis all other banks in the system. The lines linking each bank are weighted on the basis of outstanding exposures. 51 78 SCBs, 12 SFBs and 20 SUCBs were considered for this analysis. 52 The Connectivity ratio measures the actual number of links between the nodes relative to all possible links in a complete network. 53 Cluster Coefficient: Clustering in networks measures how interconnected each node is. Specifically, there should be an increased probability that two of a node’s neighbours (banks’ counterparties in case of the financial network) are also neighbours themselves. A high cluster coefficient for the network corresponds with high local interconnectedness prevailing in the system. 54 In solvency contagion analysis, gross loss to the banking system owing to a domino effect of one or more borrower banks failing is ascertained. Failure criterion for contagion analysis has been taken as Tier 1 capital falling below 7 per cent. 55 In liquidity contagion analysis, a bank is considered to have failed when its liquid assets are not enough to tide over a liquidity stress caused by the failure of large net lender. Liquid assets are measured as: 18 per cent of NDTL + excess SLR + excess CRR. 56 Failure Criterion for both PSBs and PVBs has been taken as Tier 1 CRAR falling below 7 per cent. 57 The contagion analysis used the results of the macro-stress tests and made the following assumptions: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

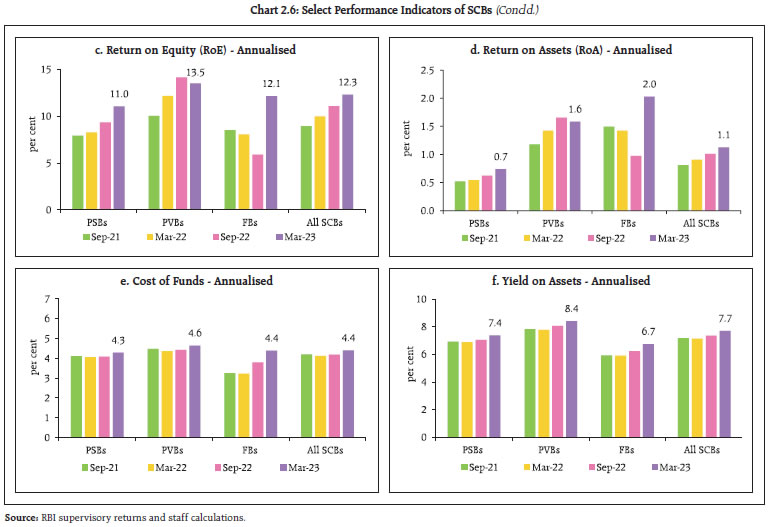

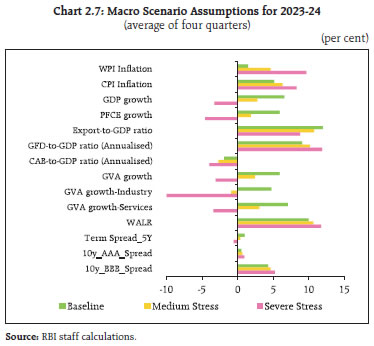

Page Last Updated on: