IST,

IST,

Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending including Lending through Online Platforms and Mobile Apps

The Working Group expresses its gratitude to the Governor, Reserve Bank of India, Shri Shaktikanta Das for entrusting the responsibility on the Group to comprehensively study all aspects of digital lending activities to enable an appropriate policy approach. The Group invited inputs and held virtual interactions with various stakeholders including financial institutions, government bodies, law enforcement agencies, academicians, and FinTech associations/ groups. The diverse interactions and different perspectives helped the Group in getting a holistic view of the nascent digital lending ecosystem. The Group would like to place on record its appreciation for all their valuable inputs, which have immensely helped in shaping this Report. The Group would like to commend the rigorous work put in by the core secretarial team of the Department of Regulation, RBI, led by Shri Chandan Kumar, General Manager and consisting of Shri Anuj Sharma, AGM; Shri Lakshmana Koyya, Shri B G Gowtham Kumar Naik, and Shri Aditya Sood, Managers. The Group would also like to acknowledge and appreciate the contribution of the secretarial teams from Department of Supervision (Shri Susheel Raina, DGM; Shri A G Giridharan, DGM; Shri Nethaji B, DGM; Shri Varun Yadav, AGM; and Ms. Tricha Sharma, AGM) and Department of Payment and Settlement Systems (Shri Anuj Ranjan, GM and Shri Brijesh Baisakhiyar, AGM). The Group would also like to express gratitude to the Legal Department (Ms. Manisha Ranvah, ALA) and all the Regional Offices of Reserve Bank of India for the inputs provided.

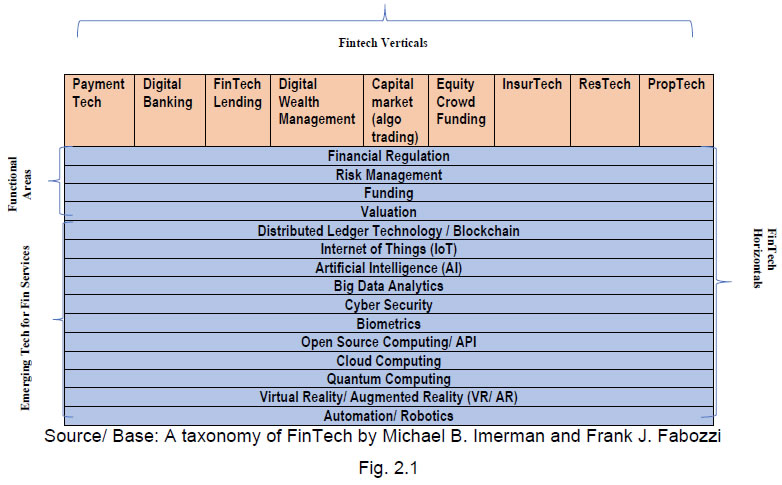

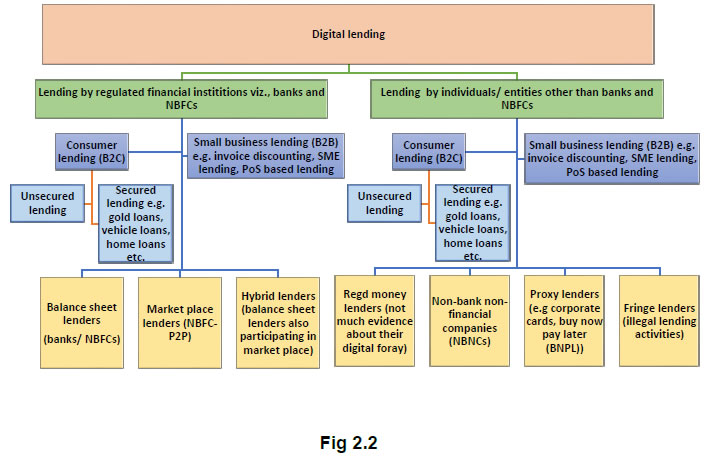

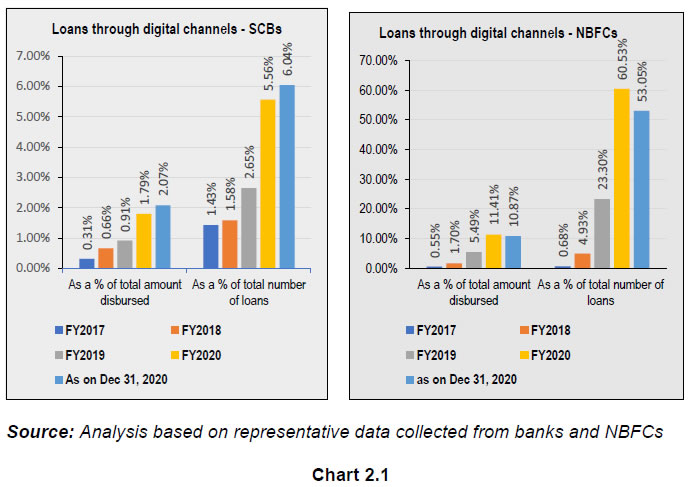

Application Programming Interface: A set of rules and specifications followed by software programs to communicate with each other, forming an interface between different software programs that facilitates their interaction. Artificial Intelligence: Information technology (IT) systems that perform functions requiring human capabilities. AI can ask questions, discover and test hypotheses, and make decisions automatically based on advanced analytics operating on extensive data sets. Annual Percentage Rate: The annual rate that is charged for borrowing a loan and includes processing fees, penalties and all other charges that are applicable to the loan throughout its life. Balance Sheet Lending: Financial service involving extension of monetary loans, where the lender retains the loan and associated credit risk of the loan on its own balance sheet. Balance Sheet Lenders: Lenders who undertake balance sheet lending. Blackbox AI: A system for automated decision making often based on machine learning (deep learning) over big data mapping the users’ features into classes predicting their behavioral traits which cannot be interpreted/ explained by even those who design it. Buy Now Pay Later: A point of sale financial product where a borrower is allowed to purchase products on deferred payment basis and pays in a predetermined number of installments. Caveat Emptor: The principle that the buyer alone is responsible for checking the quality and suitability of goods before a purchase is made. Consumer Protection Risk: Derived from the definition of misconduct risk, consumer protection risk is the risk that the behaviour of a financial services entity, throughout the product life cycle, will cause undesired effects and impacts on customers. Cooling-off Period: A period of time from the date of purchase of good or service from a distance (e.g., online, over phone or email order) within which the purchaser can change her/ his mind with return or cancellation of the purchase, as a part of Terms and Conditions of the purchase contract. Cyber Security: Protecting information, equipment, devices, computer, computer resource, communication device and information stored therein from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction. Digital Lending: A remote and automated lending process, majorly by use of seamless digital technologies in customer acquisition, credit assessment, loan approval, disbursement, recovery, and associated customer service. Digital Lending Apps: Mobile and web-based applications with user interface that facilitate borrowing by a financial consumer from a digital lender. Embedded Credit: The lending services generated from the embedding of credit products into non-financial digital platforms. FinTech (Financial Technology): A broad category of software applications and different digital technologies deployed by the intermediaries that provide automated and improved financial services competing with traditional financial services. First Loss Default Guarantee: An arrangement whereby a third party compensates lenders if the borrower defaults. Key Fact Statement: A comprehension tool in the pre-contract stage of credit process consisting of a standardized form listing all the fees, charges and other key credit information that a financial consumer needs to make informed decision which promotes transparency and healthy competition. Glass Box Model: In a Glass Box model of AI, all input parameters and the algorithm used by the model to come to its conclusion are known imparting it better interpretability. Explainable AI (X-AI) allows humans to understand and trust the output better. Lending Service Provider: Lending Service Provider is an agent of a balance sheet lender who carries out one or more of lender’s functions in customer acquisition, underwriting support, pricing support, disbursement, servicing, monitoring, collection, liquidation of specific loan or loan portfolio for compensation from the balance sheet lender. (A balance sheet lender must have continuing ability to handle the above functions and the lender, not the LSP, must be able to demonstrate that it exercises day-to-day responsibility for the same, when LSPs are engaged.) Loan Flipping: The process of raising cash periodically through successive cash-out refinancings. Loan Stacking: The process of taking out multiple loans/ credit limits by a borrower from various sources within a short period in order to reach a financial goal, both legitimate and illegitimate. Machine Learning: A method of designing problem-solving rules that improve automatically through experience. ML algorithms give computers the ability to learn without specifying all the knowledge a computer would need to perform the desired task. The technology also allows computers to study and build algorithms that they can learn from and make predictions based on data and experience. ML is a subcategory of AI. Market Place Lending: Use of online platform to connect financial consumers or businesses, who seek to borrow money, with investors/ lenders who are willing to buy or invest in such loans/ lend to such borrowers. Open Texture Rules/ Standards: Those rules/ standards that allow practices to be judged on the basis of broad, flexible requirements and are commonly used as a consumer protection tool. Pacing Problem: Time and capability gap between technological innovation/ advancement and the mechanism to regulate it. Payday Loans: A short-term, low value, high-cost loan to cover immediate cash needs typically repayable on borrower’s next pay day or when income is received from any other source and granted without considering other financial obligations. Payment Gateway: Payment Gateways are entities that provide technology infrastructure to route and facilitate processing of an online payment transaction without any involvement in handling of funds. Payment Rails: Established networks or back-end systems involved in processing of cashless payments. (Examples: pre-paid wallets/ card rails, bank real time payment rails, bank batch/ bulk payment rails, card rails, carrier billing rail, check imaging rail, etc.) Personal Identifiable Information: Information that when used alone or with other relevant data can identify an individual. Problematic Repayment Situation: A problematic repayment situation is one when the consumer is not able to repay the debt within a reasonable time, and/ or the consumer is only able to repay it in an unsustainable way, e.g., by cutting back on essential living expenses or by defaulting on other loans. Regulated Entity: Entities regulated by Reserve Bank of India. Responsibilization: Subjecting financial service providers to a broad duty to treat consumers fairly but not specifying in detail how it is to be done. Short Term Consumer Credit: The practice of lending to consumers, amounts of money that are small relative to other forms of credit in the market for short period, say, from a few days up to12 months, at an annual percentage rate considered high compared with other credit products available to consumers. Step-in Risk: In the context of the report, Step-in Risk refers to the risk that a balance sheet lender assumes by providing support to the LSP beyond the contractual obligations, both from reputational and substitutability point of view. Synthetic Identity: A synthetic identity is a combination of information that is real and fake information fabricated credentials where the implied identity is not associated with a real person. TechFin: As opposed to FinTech where traditional financial services are delivered by use of technology, TechFin is where an entity that has been delivering technology solutions launches new way to deliver financial services. In other words, FinTech takes the original financial system and improves its technology, TechFin is to rebuild the system with technology. Travel Rule: Information required to be collected, retained and be included in every fund transfer transaction initiated by one financial institution on behalf of a customer that should travel (be passed along) to each successive financial institution in the funds transfer chain. Vulnerable Consumers: Those consumers who are at a disadvantage in exchange relationships where that disadvantage is attributable to characteristics that are largely not controllable by them at the time of the transaction. (Andreasen and Manning, 1990) Technological innovations have led to marked improvements in efficiency, productivity, quality, inclusion and competitiveness in extension of financial services, especially in the area of digital lending. However, there have been unintended consequences on account of greater reliance on third-party lending service providers mis-selling to the unsuspecting customers, concerns over breach of data privacy, unethical business conduct and illegitimate operations. While the current share of digital lending in overall credit pie of the financial sector is not significant for it to affect financial stability, the growth momentum has compelling stability implications. It is believed that ease of accessing digital financial services, technological innovations and cost-efficient business models will eventually lead to meteoric rise in the share of digital lending in the overall credit. The larger issue here is protecting the customers from widespread unethical practices and ensuring orderly growth. As has been seen during the pandemic-led growth of digital lending, unbridled extension of financial services to retail individuals is susceptible to a host of conduct and governance issues. Mushrooming growth of technology companies extending and aiding financial services has made the regulatory role more challenging. In view of the ease of scalability, anonymity and velocity provided by technology, it has become imperative to address the existing and potential risks in the digital lending ecosystem without stifling innovation. Further, on a larger canvas and on a medium to long term horizon, digital innovations along with possible entry of BigTech companies may alter the institutional role played by existing financial service providers and regulated entities. A fallout of this may get reflected in blurring of regulated and unregulated financial institutions/ activities. Such developments spurred by mere commercial considerations would pose regulatory challenges in ensuring monetary and financial stability and in protecting interests of the customers. The recommendations and suggestions are aimed at addressing issues posed by digital evolution of the financial activities/ products/ institutions while ensuring ways to reap the benefits of digital innovation at the same time. The WG recommendations would act at three levels: regulated entities of the RBI; other regulated/ authorised entities; and unregulated entities including third-party service providers functioning in the digital financial realm. The recommendations seek to protect the integrity of the system against entities that are not regulated and not authorized to carry out lending business. The onus of subjecting third-party lending service providers to a standard protocol of business conduct would lie with the regulated entities to whom they are attached. Further, an institutional mechanism is envisaged to ensure the basic level of customer suitability, appropriateness and protection of data privacy. The report further seeks to ensure that there is orderly growth in the digital lending ecosystem without it being unduly disruptive towards the existing players in the ecosystem. The idea is that the existing players in the digital lending realm should follow recommended standards of appropriateness to address conduct/ technological issues. The approach adopted in this Report is guided by the following three principles:

To achieve these principles in a holistic manner, the WG has recommended a three-pronged measure on a near to medium term. Some of the key recommendations of the Working Group are enumerated below: a) Legal & Regulatory Recommendations Near Term (up to one year)

Medium Term (above one year)

b) Recommendations related to Technology Near Term

Medium Term

c) Recommendations related to Financial Consumer Protection Near Term

Medium Term

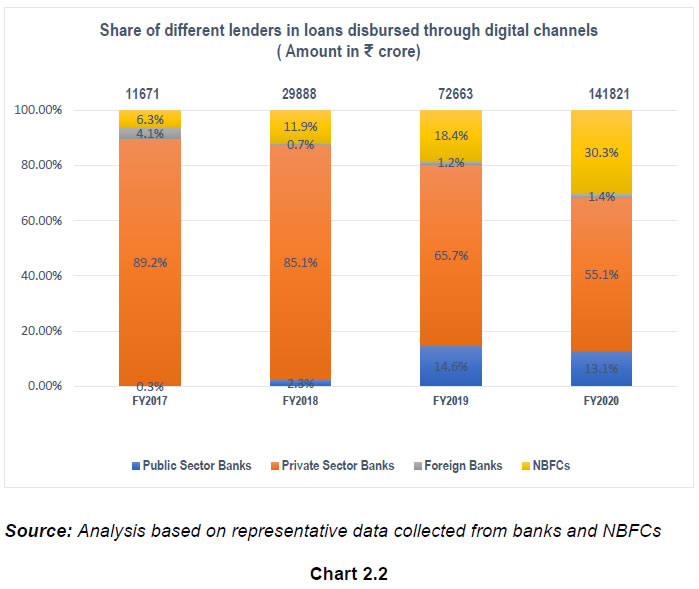

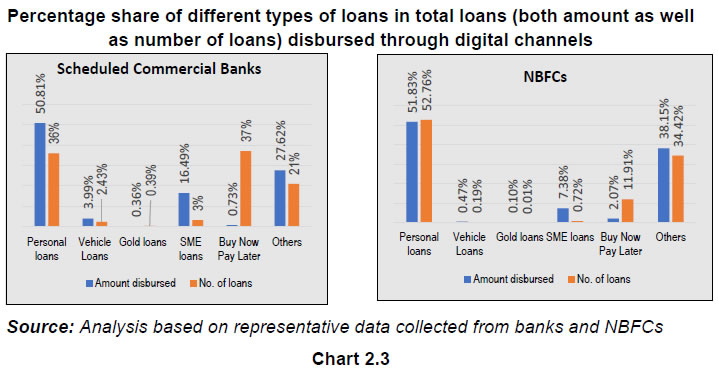

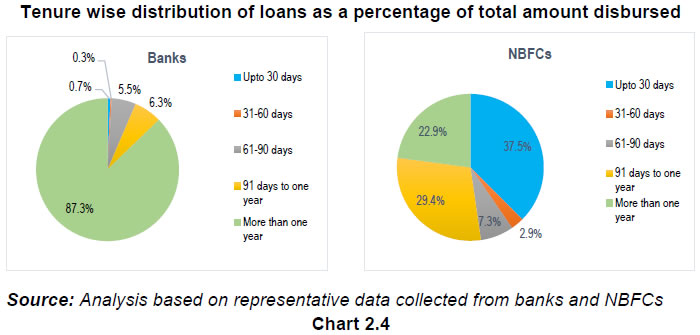

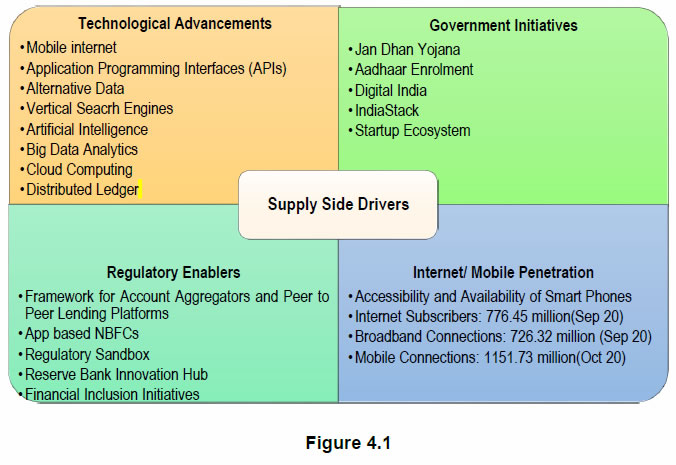

Besides recommending concrete action points, the WG has also made several suggestions. The suggestions would require wider consultation with stakeholders and further examination by the regulators and government agencies. A gist of recommendations and suggestions along with the implementation agency is provided at the end of the report. All entities operating in the digital lending ecosystem do not come under the regulatory purview of the Reserve Bank. For entities other than regulated entities (REs) of the Reserve Bank, concerned authorities are expected to put in place similar measures as recommended/ suggested for the REs of the Reserve Bank. This would ensure holistic compliance with the recommendations/ suggestions contained in this report. 1.1 Constitution of the Working Group Recent spurt of disruptive innovations and consumerization of online lending apps (‘digital lending’), both mobile and web-based, have reshaped the way financial services are structured, provisioned and consumed. In its evolution, riding on other digital cousins such as digital payment and social media, certain actors could use it for their own ends, with unintended consequences for the nascent ecosystem. Against this backdrop, the Reserve Bank had constituted a Working Group (WG) on digital lending on January 13, 2021 to study all aspects of digital lending activities in the regulated financial sector as well as by unregulated players so that an appropriate regulatory approach can be put in place. The terms of reference and names of the members of the WG are as under: Terms of Reference 1. Evaluate digital lending activities and assess the penetration and standards of outsourced digital lending activities in RBI regulated entities; 2. Identify risks posed by unregulated digital lending to financial stability, regulated entities and consumers; 3. Suggest regulatory changes, if any, to promote orderly growth of digital lending; 4. Recommend measures, if any, for expansion of specific regulatory or statutory perimeter and suggest the role of various regulatory and government agencies; 5. Recommend a robust Fair Practices Code for digital lending players, insourced or outsourced; 6. Suggest measures for enhanced consumer protection; and 7. Recommend measures for robust data governance, data privacy and data security standards for deployment of digital lending services. Members Internal Members 1. Shri Jayant Kumar Dash, Executive Director, RBI (Chairman) 2. Shri Ajay Kumar Choudhary, Chief General Manager-in-Charge, Department of Supervision, RBI (Member) 3. Shri P. Vasudevan, Chief General Manager, Department of Payment and Settlement Systems, RBI (Member) 4. Shri Manoranjan Mishra, Chief General Manager, Department of Regulation, RBI (Member Secretary) External Members 1. Shri Vikram Mehta, Former Associate of Monexo FinTech (Member) 2. Shri Rahul Sasi, Cyber Security Expert & Founder of CloudSEK (Member) The Group conducted four meetings between January 19, 2021 and April 01, 2021 which were attended by all members and the secretarial team. In recent periods, a spate of digital micro-lending by various fringe entities and their dubious business conduct were flagged to RBI, Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs), and reported in public domain. Such incidents were grappled by various LEAs at State level, albeit in non-uniform manner, after certain clarifications on identity of regulated entities were rendered by RBI, followed up by awareness drives. This undesirable experience was the imminent prompt for constitution of the Working Group to recommend a framework to address such issues holistically. The WG adopted a four-pronged process towards the report: (a) Discussions with Stakeholders: Formal and informal inputs were sought from academicians, regulated entities, FinTech advocacy groups, consumer interest groups, industry bodies, FinTechs, app stores, LEAs, and central and state governments. The WG received inputs from thirty-six such stakeholders and their feedback covered various aspects - legal, regulatory, technological, code of conduct, fair practices, grievance redressal, etc. A brief synopsis of such inputs is presented at Annex A. A total of ten formal interfaces were also held with important stakeholders in the digital lending arena to elicit their views on the subject. Details of interfaces and list of entities that provided their inputs to the WG are provided at Annex B. (b) Survey and Data Analysis: A representative survey was conducted to collect data on certain aspects of digital lending in which sample data was collected from 76 Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs) and 75 NBFCs, out of which 48 SCBs and 13 NBFCs stated that they are not engaged in digital lending. As per the data furnished by the remaining 28 SCBs and 62 NBFCs, digital lending constituted 75 per cent and 10 per cent of total assets of banks and NBFCs respectively as on March 31, 2020. The extracts of the survey data are appended at Annex C. (c) Review of Extant Regulatory / Supervisory Framework and Industry Practices: A detailed review was carried out covering the extant regulatory framework, prevailing practices followed by DLAs, ancillary functions performed by various outsourcing agencies and FinTechs (e.g., sourcing, appraisal, payments, collection, etc.). (d) Review of Global Practices and Literature: The WG also reviewed internationally published literature on the subject, the global developments, approaches adopted in other jurisdictions, and the evolving views of global standard-setting bodies and assessed their suitability for Indian system. 1.4.1 The WG kept in view three broad tenets while considering the best fit approach for crafting FinTech appropriate regulation for digital lending. (a) Technology Neutrality: Regulatory approach should be neutral towards technological differentials or business models; rather be encouraging healthy competition among all players that maximize the benefits to the financial system. Technology neutrality theory would imply that what is not legal offline, cannot be legal online. Many of the trouble spots around the fringe digital lending were considered identical to the known types of undesirable lending practices in the conventional lending landscape, albeit in a digital edition. A proportionate approach of ‘same activity, same risk, same rule’ principle for the entire lending ecosystem, digital or otherwise, required up-linking of a few recommendations to the original guidelines already issued or those in the context of broader FinTech that could be prospectively issued, rather than limiting these to narrow confines of digital lending. This should also be seen to have forward compatibility in the context of approach to regulations of broader digital financial services as and when it evolves. Harmonizing market conduct rules and oversight for all comparable credit offerings for all providers and channels would also fall under this tenet. The proportionate regulatory framework for smaller players in certain key areas such as cyber security/ IT risk should have similar regulatory frameworks to avoid the ‘weakest-link’ problem that could pose risks to the payment and settlement systems. (b) Principle Backed Regulations: A graded approach to any regulation generally moves through minimum regulation, light precautionary regulation, and strong precautionary regulation phases. As the report covers three distinctive regulatory dimensions of digital lending, it blends all the grades of regulations. For a smooth integration, a principle-backed approach has been preferred to a rule-based regime as it affords flexibility in terms of its actual application to innovations, rather than a stifling over-prescriptive regime. While a commensurate construct for the equilibrium trinity of innovation, regulation and stability for digital lending has been attempted in the report, maintaining flexibility, adaptability and continuous learning in a rapidly evolving and dynamic environment is what should be attempted in its implementation. It is rightly argued that consumer protection regulation should follow an approach of open texture rules/ standards and responsibilization rather than being a ‘command and control’ type. However, for the present context in India, the regulatory approach should include, among others, moving beyond mere disclosure and fair practice framework to more regulatory guardrails, particularly in respect of recurring issues. (c) Addressing Regulatory Arbitrage: A sine qua non for an effective regulatory regime is to prevent the emergence of regulatory gaps and arbitrages that might arise from appearance of new service providers, innovative products, etc., which are like those being regulated in respect of the incumbent players. A level playing field is key to ensure not only fair competition but also consumer protection. The same regulatory conditions and supervision should apply to all actors who seek to innovate and compete on FinTech: incumbent banks, FinTech start-ups and BigTech firms. These efforts should be towards better consumer protection and market integrity. 1.4.2 The WG recognizes the increasing significance of ‘digital lending’ in the financial ecosystem, particularly in the realms of financial inclusion, access and SME financing spawning a compulsive case for an ecosystem of partnership. Like any emerging business models, there are bound to be structural gaps and operating issues in digital lending ecosystem. The inevitability of its growth to match the nonpareil maturation of digital payment systems in India, warrants a shift from minimum-regulation approach in nascent stage to align to the truism that financial sector cannot be left to self-regulation. Given the maturity level of the evolving ecosystem for digital lending and potential grey areas for regulatory/ legal arbitrageurs, the WG determined that there may be a need for multiple agency approach/ frameworks required to address the issues in entirety, supported by central legislations/ notifications wherever required. Hence, the recommendations essentially capture the issues in perspective and seek to create an environment where the agency roles can be more transparent with necessary identifiers to shine light on the bad actors. In the absence of laws with specific provisions to address the issues, regulation should measure up for mitigating the risks. 1.4.3 Recognizing the tradeoff between consumer convenience, the leitmotif of digital financial services, and consumer protection, the need for a very fine balance while laying clear ground rules has also been weighed in. Responsible lending will remain a distant goal without customer awareness and watchful enforcement. However, while recommending regulations, on balance, protection of financial consumers’ interest would always weigh heavier than the interest of innovation. Although the digital lending canvas is much larger, the focal problem points in the recent digital lending (‘one-click credits’) episodes have been small value (nano/ micro) unsecured/ non-income generating loans to financial consumers. There is a lack of a comprehensive regulatory framework in consumer lending through DLAs from origination to debt collection and its administration including the business of providing credit references. Section 2: Digital Lending Landscape The world has been talking about Bank 4.00 since 2014 indicating arrival of 4th generation in evolution of financial services comprising FinTech, online/ mobile banking, virtual global market and questioning the sustainability of conventional banking. The book “Bank 4.00” by Brett King published in 2018 carried the sub-title “Banking Everywhere, Never at a Bank”. India has been whetting its appetite for digital transformation in financial services, slowly but steadily. Digital lending is one of the most prominent off-shoots of FinTech in India. The digital/ FinTech lending has to be seen in the overall context of the FinTech eco system per se, stylised in the following diagram.  It’s another matter that the trend of Bank 5.01 has already been set in motion, riding on cognitive banking, embedded banking, decentralised finance, robo-advisors, hybrid robo-advisors and bots, responsible banking. Financial Stability Board (FSB) has defined FinTech as “technologically enabled innovation in financial services that could result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and the provision of financial services”. In the absence of a universally acceptable definition of the term ‘digital lending’, FSB definition of the term ‘FinTech credit2’ as all credit activity facilitated by electronic platforms whereby borrowers are matched directly with lenders comes close. This definition has been loosely explained by FSB to include market place lending i.e., lending financed mostly from wholesale sources and non-loan obligations, such as, invoice trading. FSB has also classified ‘peer-to-peer lending’ and ‘loan-based crowdfunding’ as the main components of FinTech credit. Taking cognizance of the lack of a universally acceptable comprehensive definition of ‘FinTech credit’ or ‘digital lending’, this report has not attempted to define this term, as new models and approaches are still evolving. One generally accepted feature of digital lending is that it means ‘access of credit intermediation services majorly over digital channel or assisted by digital channel’. For the purpose of this report, the characteristics that are essential to distinguish digital lending from conventional lending are use of digital technologies, seamlessly to a significant extent, as part of lending processes involving credit assessment and loan approval, loan disbursement, loan repayment, and customer service. 2.2 Digital Lending Eco-System In India, digital lending ecosystem is still evolving and presents a patchy picture. While banks have been increasingly adopting innovative approaches in digital processes, NBFCs have been at the forefront of partnered digital lending. From the digital lending perspectives, such lending takes two forms, viz. balance sheet lending (BSL) and market place lending (MPL), aka platform lending. The difference between BSL and MPL lies where the lending capital comes from and where the credit risks of such loans reside. Balance Sheet Lenders are in the business of lending who carry the credit risk in their balance sheet and provide capital for such assets and associated credit risk, generated organically or non-organically. Market Place Lenders (MPLs) or Market Place Aggregators (MPAs) are those who essentially perform the role of matching the needs of a lender and borrower without any intention to carry the loans in their balance sheet. While P2P lending in India is a clear example of MPL, many other players who are in the business of originating digital loans, (e.g., MPAs, FinTech platforms or the so called ‘neo banks’ or BNPL players) with the intention of transferring such digital loans to BSLs, can also be bracketed with MPLs/ MPAs. These categories of market players form part of the broader class of Lending Service Providers (LSPs). An illustration of digital lending taxonomy in a universal context is provided in Figure 2.2 below.  Another noteworthy development in recent years has been the entry of technology service providers of various forms, in addition to the existing ones, into the financial sector creating a larger universe for the ecosystem (Fig 2.3).  For this report, the ecosystem of entities engaged in digital lending has been broadly segregated into two categories, viz. (i) Balance Sheet Lenders (BSLs) and, (ii) Lending Service Providers (LSPs). The latter category encompasses both the services being provided and the service providers. An entity can perform the roles of both BSL as well as LSP, as is usually the case of traditional lenders. Post global financial crisis, financial markets around the world have undergone a significant transformation driven by technological innovation. In credit segment, P2P lending platforms have emerged as a new category of intermediaries, which are either providing direct access to credit or facilitating access to credit through online platforms. Besides, there are companies primarily engaged in technology business which have also ventured into lending either directly or in partnership with financial institutions. Such companies include ‘BigTechs’, e-commerce platforms, telecommunication service providers, etc. In digital lending space, we have global examples of Person-to-Person (P2P), Person-to-Business (P2B), Business-to-Person (B2P), Business-to-Business (B2B) lending models. A paper3 published by BIS has estimated total global alternative credit (i.e., credit through FinTechs and BigTechs) in 2019 at USD 795 billion in which share of FinTechs and BigTechs is around USD 223 billion and USD 572 billion respectively. China, USA and UK are the largest markets for FinTech credit. BigTech has exhibited rapid growth in Asia (China, Japan, Korea and Southeast Asia), and some countries in Africa and Latin America. The largest market for both FinTech credit and BigTech credit is China, although of late, it has shown signs of contraction due to certain market and regulatory developments. While USA is the second largest market for FinTech credit, its share in BigTech credit is comparatively small. In BigTech credit, Japan is the second largest market with USD 23.5 billion lending in 2019. In UK, FinTech credit volumes are estimated at USD 11.5 billion in 2019 (up from USD 9.3 billion in 2018). The BIS paper has highlighted that FinTech credit volumes are growing decently in European Union, Australia and New Zealand while these have stagnated in USA and UK and declined in China. In many emerging market and developing countries, FinTech lenders are attaining economic significance in specific segments such as small and medium-sized enterprises. 2.4.1 Digital Lending vis-à-vis Physical Lending Based on data received from a representative sample of banks and NBFCs (representing 75 per cent and 10 per cent of total assets of banks and NBFCs respectively as on March 31, 2020), it is observed that lending through digital mode relative to physical mode is still at a nascent stage in case of banks (₹1.12 lakh crore via digital mode vis-à-vis ₹53.08 lakh crore via physical mode) whereas for NBFCs, higher proportion of lending (₹0.23 lakh crore via digital mode vis-à-vis ₹1.93 lakh crore via physical mode) is happening through digital mode.  In 2017, there was not much difference between banks (0.31 per cent) and NBFCs (0.55 per cent) in terms of the share of total amount of loan disbursed through digital mode whereas NBFCs were lagging in terms of total number of loans with a share of 0.68 per cent vis-à-vis 1.43 per cent for banks. Since then, NBFCs have made great strides in lending through digital mode. 2.4.2 Share of Digital Lending Overall volume of disbursement through digital mode for the sampled entities has exhibited a growth of more than twelvefold between 2017 and 2020 (from ₹11,671 crore to ₹1,41,821 crore).  Private sector banks and NBFCs with 55 per cent and 30 per cent share respectively are the dominant entities in digital lending ecosystem. Also, share of NBFCs has increased from 6.3 per cent in 2017 to 30.3 per cent in 2020 indicating their increasing adoption of technological innovations. During the same period, public sector banks have also increased their share significantly from 0.3 per cent to 13.1 per cent. The prominent role of NBFCs in fostering digital mode of lending is reflective of the flexible regulatory regime (vis-à-vis banks) meant for NBFCs. 2.4.3 Product Profile 2.4.3.1 Product mix based on loan purpose The major products disbursed digitally by banks are personal loans followed by SME loans. A few private sector banks and foreign banks are also offering Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) loans. Loans under ‘others’ category for banks comprise mostly of small business and trade loans, home loans and education loans.  Majority of loans disbursed digitally by NBFCs are personal loans followed by ‘others’ loans. In case of NBFCs, ‘others’ loans primarily include consumer finance loans. Even though the amount disbursed under BNPL loans is only 0.73 per cent (SCBs) and 2.07 per cent (NBFCs) of the total amount disbursed, the volumes are quite significant indicating a large number of small size loans for consumption. 2.4.3.2 Product mix based on loan tenure One difference between banks and NBFCs is in terms of tenure of loans disbursed through digital channels. While around 87 per cent of loans amounting to ₹0.98 lakh crore disbursed by banks have tenure of more than one year, for NBFCs only 23 per cent of the loans amounting to ₹0.05 lakh crore fall under this bucket.  On the contrary, loans with tenure of less than 30 days have maximum share in case of NBFCs (37.5 per cent amounting to ₹0.9 lakh crore) vis-à-vis 0.7 per cent amounting to ₹0.007 lakh crore for banks. 2.4.4 Source of DLAs among Regulated Entities While public sector banks and foreign banks have been observed to largely depend on their own apps/ websites for disbursal of digital loans, the dependency of private sector banks on outsourced/ third-party apps is significantly higher. Credit offered through digital channels by public sector banks is mostly secured whereas for private sector banks and foreign banks, most of the digital lending portfolio is unsecured and specifically, the third-party app sourced loans in private sector banks are unsecured. In case of NBFCs, there is not much difference between disbursal through own digital channels and third party digital channels with some skew towards own channels (57 per cent). 2.4.5 Density of DLAs and illegal players 2.4.5.1 As per the findings of the WG, there were approximately 1100 lending apps available for Indian Android users across 80+ application stores (from January 01, 2021 to February 28, 2021). Details are as under:

2.4.5.2 Complaints against DLAs – Sachet, a portal established by the Reserve Bank under State Level Coordination Committee (SLCC) mechanism for registering complaints by public, has been receiving significantly increasing number of complaints against digital lending apps (around 2562 complaints from January 2020 to March 2021). Majority of the complaints pertain to lending apps promoted by entities not regulated by the Reserve Bank such as companies other than NBFCs, unincorporated bodies and individuals. Another significant chunk of complaints pertains to lending apps partnering with NBFCs especially smaller NBFCs (asset size of less than ₹1000 crore). Geographical and time-line wise distributions of these complaints are provided in following tables:

Post issuance of the press release6 dated December 23, 2020 by the Reserve Bank cautioning public against unauthorised digital lending platforms/ mobile apps and creating awareness to register complaints against such lenders on Sachet, a significant increase in complaints was observed with December 2020 recording the maximum number of complaints at over 35 per cent of the total complaints. These are still early days, but the trends are indicating a steady decline in complaints since January 2021. 2.4.5.3 Actions taken by google play store against digital lending apps reported by the enforcement authorities are given below:

If past performance is key to predict the future, then it can be unambiguously stated that digital lending is the way to go. In not-so-distant future, lending in general and especially retail and MSME lending through physical mode may be rendered obsolete as is the case with operational banking today. It makes sense for banking transactions to take newer shape as purchases, payments and record-keeping go digital. The growth in digital lending over last five years, when other enabling factors and supporting infrastructure were still evolving, has been phenomenal and it is time for digital lending to operate in full swing, enabled by support and participation from all stakeholders. As per a Report7, India had highest FinTech adoption rate of 87 per cent as of 2020. This report values Indian FinTech market at ₹8.35 lakh crore by 2026 in comparison to ₹2.3 lakh crore in 2020 thus expanding at a compound annual growth rate of ~24.56 per cent. Section 3: Regulatory Policy Approach to Digital Lending From a regulatory policy outlook, the FinTech landscape can be divided into two spheres, viz. Incrementalistic FinTech and Futuristic FinTech8. The former uses new data, algorithm, software applications to perform traditional financial service provisions without significant change in the underlying functions. The latter disrupts the financial markets in manners that effectively supersede regulation. The work of the WG is generally centered around the first sphere of FinTech which is under current focus. 3.1 Extant Indian Legal Regimes In India, lending activity, online or otherwise, is governed by following laws, in addition to various regulatory instructions issued by RBI for its regulated entities: 3.1.1 Banking Regulation (BR) Act, 1949: Business of banking as defined in Section 5(b) of the BR Act, includes providing loans inter alia by a banking company, through online mode or otherwise. All banks (public and private sector) including small finance banks, regional rural banks and co-operative banks are required to get themselves registered with the Reserve Bank for undertaking digital lending. 3.1.2 Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934: Besides banks, NBFCs, complying with principal business criteria are required to be registered with RBI as per provisions of RBI Act. For this purpose, an NBFC is defined as a company registered under the Companies Act whose principal business is financial activity i.e. business of loans and advances, acquisition of shares/ stocks/ bonds/ debentures/ securities issued by Government or local authority or other marketable securities of a like nature, leasing, hire-purchase, insurance business, chit business. This does not include any institution whose principal business is agriculture activity, industrial activity, purchase or sale of any goods (other than securities) or providing any services and sale/ purchase/ construction of immovable property. Further, financial activity is treated as principal business when a company’s financial assets constitute more than 50 per cent of the total assets and income from financial assets constitute more than 50 per cent of the gross income. A company fulfilling both these criteria is required to get itself registered as an NBFC with RBI. The term 'principal business' is not defined under the RBI Act. RBI has defined it to ensure that only companies predominantly engaged in financial activity are subject to its regulation and supervision. Hence, if there are companies engaged in agricultural operations, industrial activity, purchase and sale of goods, providing services or purchase, sale or construction of immovable property as their principal business and are doing some financial business in a small way, they are not required to get themselves registered with RBI. To obviate dual regulation, certain categories of NBFCs, regulated by other regulators, have been exempted from the requirement of registration with RBI, viz. alternative investment fund companies/ merchant banking companies/ stock exchanges/ stock broking companies registered with SEBI, insurance companies registered with IRDAI, Nidhi companies/ mutual benefit companies under Companies Act, and chit companies under Chit Funds Act. 3.1.3 Companies Act, 2013: Companies, which are not meeting principal business criteria for registration as an NBFC with RBI, can also undertake lending activities subject to applicable provisions of the Companies Act, 2013 such as Section 1869 of the Companies Act, 2013 which prescribes certain restrictions on the loan amount and minimum interest rate for such loans. Besides, there are nidhi companies/ mutual benefit companies which are permitted to receive deposits from and lending to their members as per provisions of Section 406 of the Companies Act, 2013 and ‘Nidhi Rules, 2014’. 3.1.4 State Money Lenders Acts: The Constitution of India has conferred the power to legislate on matters relating to money lending and moneylenders to the States. Most of the states have their respective money lenders legislations in place (Annex D). Many of these are comprehensive legislations providing detailed and stringent provisions for regulation and supervision of the money lending business. These legislations contain provisions aimed at protecting the borrowers from malpractices of the moneylender. Some of the salient aspects of these laws are as below: