5.1 Banking institutions are exposed to a diverse set of market and non-market risks. Banking, by its very nature, is an attempt to manage multiple and seemingly opposing needs, and that makes banks ‘special’. Banks stand ready to provide liquidity on demand to depositors through chequeing accounts and extend credit as well as liquidity to their borrowers through lines of credit (Kashyap, Rajan and Stein, 1999). In the process, banks face several risks for which they need to take protective measures to ensure that they remain solvent and liquid. Thus, robust risk management and strong capital position are critical in ensuring that individual banking organisations operate in a safe and sound manner, which, in turn, is crucial for maintaining the stability of the financial system and fostering economic growth.

5.2 The major goals of financial sector policies are to maintain financial stability and also enhance access to financial services. These two goals are mostly mutually reinforcing. Through the financial stability goal, policymakers aim at protecting savers, investors and other economic agents from economic disruptions, which help in ensuring access to financial services, including unprivileged sections of society. Ensuring financial stability calls for greater soundness of the system and more effective risk management practices. Understanding the risks in the system and managing them, and earmarking sufficient amounts of capital, increases the stability of the system. More generally, strong capital helps banks absorb unexpected shocks and reduces the moral hazard associated with deposit insurance.

5.3 Traditionally, banks held capital as a buffer against insolvency, and liquid assets – cash and securities – to guard against unexpected withdrawals by depositors or drawdowns by borrowers (Saidenberg and Strahan, 1999). Risk is the potential of both expected and unexpected events having an adverse impact on banks’ capital or earnings. Capital adequacy ratios are intended to ensure that banks maintain a minimum amount of own funds in relation to the risks they face so that banks are able to absorb unexpected losses. Thus, the expected losses are covered by a combination of product pricing, business revenue and loss provisions, and the unexpected losses by capital funds of the bank. Capital ensures that unanticipated market situation or deterioration in borrower credit quality does not present any serious challenge to bank’s solvency. Capital does not, however, seek to ensure that banks would be immune from failure1 .

5.4 Theories suggest that banks’ choices of portfolio risk and capital are interrelated. A sound risk management process is the basis for an effective assessment of the adequacy of a bank’s capital. For depository institutions, it is, therefore, necessary that the economic substance of risk exposures is fully recognised and incorporated into the system. The estimates of risk must translate into robust capital assessments.

5.5 Capital and risk management are of interest not only to supervisors, but also to all stakeholders, including bank owners, employees as well as depositors and lenders. The owners are inherently interested in the continued existence of the bank as they expect a reasonable return on their investments and wish to avoid capital losses. Furthermore, the bank’s employees, depositors and lenders also have a stake in its survival. This is because, in case of bank failure, the bank is unable to repay all of its depositors and lenders in full and on time and there is a possibility that these parties may have to bear losses. Similarly, the credibility of bank employees is questioned in case of bank failure. The individual interests of these groups are not necessarily congruent; however, all parties are interested in ensuring that the institution does not take on risk positions that might endanger its continued existence. The traditional objective of capital regulation has been to reduce bank failures and to promote banking stability. Another important objective has been to reduce losses to depositors’ and the deposit insurer when a bank fails. Regulators are particularly sensitive to deposit insurance losses because the Government not only often provides insurance through formal programmes, but also, in the absence of de jure coverage, acts as the insurer of last resort.

5.6 Even though regulators all over the world have been concerned about bank capital, there were no formal regulations that specified minimum capital ratios in the pre-Basel phase, i.e., before the signing of the Basel Capital Accord in 1988. At the beginning of the 1980s, regulators became increasingly dissatisfied with many banks’ capital ratios, especially those of the larger banking organisations and bank holding companies. As a result, regulators in the US specified minimum capital-to-asset ratios for all banks under their jurisdiction in 1981; the remaining banks were required to raise their capital-to-asset ratios; and were brought under numerical standards by 1983 (Wall, 1989). The banking industry in the US increasingly raised its capital ratios in the years subsequent to the adoption of the 1981 guidelines. However, the simplistic use of capital-to-total assets ratio as a measure of risk was called into question as banks adjusted their portfolios away from less risky and towards riskier assets. During the 1980s, however, banks in the US and western Europe reduced their investment in high liquidity, low-return assets and increased their exposure to potentially risky off-balance sheet transactions. Thus, the capital-to-total assets ratios that might have been adequate in the early 1980s lost their importance later in the decade. As a consequence, several countries adopted the risk-based capital standards that were popularised during this period under the aegis of the BIS.

5.7 The signing of the Basel Accord by 12 countries (all G-10 countries plus Luxembourg and Switzerland) in July 1988 was a landmark in the area of capital regulation. The Basel Accord, 1988 was designed to establish minimum levels of capital for internationally active banks. Its simplicity encouraged over 100 countries across the world not only to adopt the framework, but also apply it across the entire banking segment without restricting it to the internationally active banks. However, developments during the 1990s reduced the effectiveness of the 1988 Basel Capital Accord. Significant advances in technology and financial product innovations reshaped the role played by banks in the credit process. Core institutions started to move away from traditional buy-and-hold strategies to an originate-to-distribute or market-based model.

5.8 The worldwide trend towards deregulation of the financial sectors added to the widespread banking problems of many countries. Furthermore, with the increasing globalisation of the financial systems, concerns about bank soundness assumed heightened importance for international financial stability in general, and banking sector stability in particular (BIS, 2000). Hence, banking organisations’ capital ratios became the focus of regulatory and supervisory attention. Recent market events have also highlighted emerging new risks for the banking system, which have created some intricate risk management challenges. As banks have extended their range of activities from basic lending to holding securities, trading complex instruments, providing liquidity facilities, engaging in off-balance sheet transactions, and conducting other financial activities, and as they have involved themselves in new markets, the risk management challenges have multiplied. As a result, bank supervisors are also taking keen interest in promoting strong risk management practices within banking organisations. At the heart of the contemporary banking supervision is an assessment of the quality of banks’ procedures for evaluating, monitoring, and managing risk. Supervisors have also started to evaluate banks’ internal models for determining economic capital which helps banking organisations link risk to capital as also to compare risks and returns across diverse business lines and locations.

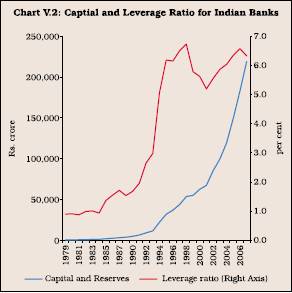

5.9 In line with the international best practices, India has also been strengthening capital adequacy framework and risk management practices of banks. These, however, have varied over different banking segments, depending on their size and complexity. Basel I norms for scheduled commercial banks, which constitute the largest segment of the banking system, were introduced in 1992. These norms, subsequently, were also applied to urban co-operative banks. Internationally active domestic banks and foreign banks have already moved over to Basel II tailored to country-specific conditions, while other scheduled commercial banks are in the process of moving towards adoption of Basel II. India has put in place a comprehensive risk management system to take care of credit risk, market risk and operational risk, for enhancing financial stability.

5.10 This chapter is organised in seven sections. The introductory section is followed by a section on the relationship between risk and capital in Section II. Section III focuses on the international convergence of capital measurement and capital standards. Section IV delineates several issues relating to implementation of Basel II framework, including its benefits, limitations, its likely impact, challenges in implementation as well as the progress of its implementation in major countries. The policy developments in the area of managing capital and risk in the Indian context are discussed briefly in Section V. Besides, this section also includes the progress in implementation of Basel II risk management practices, asset liability management and corporate governance in the Indian context. An analysis as to how banks managed capital in the post-reform period and an assessment of capital requirements in each of the next five years (2007-08 to 2011-12), with special focus on public sector banks, are also presented in this section. Section VI sets out the issues of relevance and challenges for the future. Section VII concludes the chapter.

II. RISK AND CAPITAL

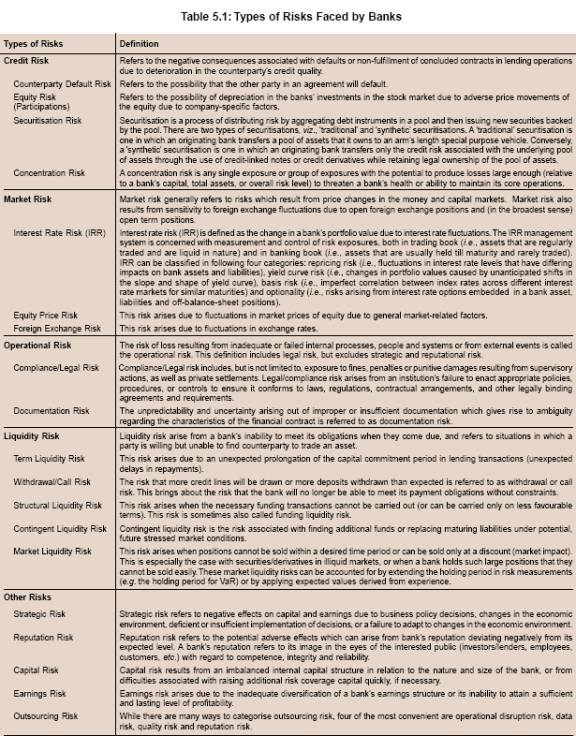

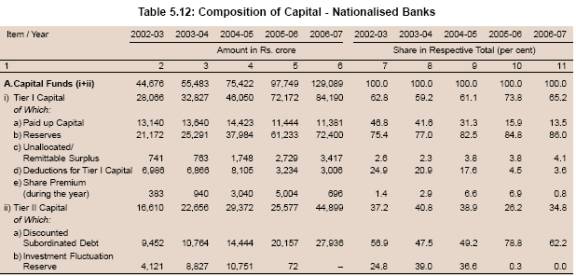

5.11 The risks associated with providing banking services differ by the type of service rendered. Risk is the danger of an adverse deviation in the actual result from an expected result. This interpretation of risk can be expressed as a probability distribution, with future results fluctuating around an expected level. The actual risk to the bank thus consists of the possibility that the result will deviate negatively from the expected value due to random fluctuations. Risk is inherent in banking business. Banks that run on the principle of avoiding risks cannot meet the legitimate credit requirements of the economy. On the other hand, a bank that takes excessive risks is likely to run into difficulty. Credit risk is the most common risk in banking and possibly the most important in terms of potential losses. The default of a small number of key customers could generate very large losses and in an extreme case could lead to a bank becoming insolvent. This risk relates to the possibility that loans will not be paid or that investments will deteriorate in quality or go into default with consequent loss to the bank. Credit risk is not confined to the risk that borrowers are unable to pay; it also includes the risk of payments of the bills being delayed beyond the maturity time, which can also cause problems for the bank. Changes in the banking industry and financial markets have increased the complexity of banking risks faced by the banking institutions. Therefore, apart from some traditional risks, banks have also come to face several new risks (Table 5.1).

5.12 Having identified the risks, the management of risk in a financial institution consists of three elements - (i) the accurate measurement and monitoring of risk; (ii) controlling and pricing exposures; and (iii) the holding of adequate capital and reserves to meet unexpected losses. The trend in supervisory oversight in recent years has been to work on each of these aspects.

5.13 The definition of a suitable risk appetite is a basic operational pre-requisite for the bank to set consistent risk limits. Risk appetite is defined as the bank’s willingness to take on financial risks as quantified by the appropriate indicators (i.e., as a measure of the bank’s risk-seeking behavior). Based on the defined risk appetite, an overview of the bank’s actual risk structure can provide a starting point for defining its target risk structure. The bank’s actual risk structure might include the current relative significance of various risk types at the overall bank level (credit risk, market risks in the trading book, interest rate risk in the banking book, etc.) and the distribution of risk concentrations among individual risk types. After assessing the bank’s risk position, the next important step is to ensure that enough capital is available to absorb losses, should risk/s materialise.

5.14 Capital is the rarest and most expensive of a bank’s resources and is directly and immediately available to cover losses. Insofar as a banking company is concerned, capital serves several purposes. It (i) is a permanent source of funding support for the bank’s operations; (ii) absorbs losses and changes in asset values and thereby helps in maintaining solvency; (iii) encourages depositors’ confidence; (iv) encourages shareholders’ interest in governance of the bank; (v) provides protection to creditors in the event of liquidation; and (vi) protects the bank against uncertainty. The capital provided by a bank’s shareholders, on the one hand, allows banks to take risk, and on the other hand, it requires that such risks provide an appropriate remuneration. It is, therefore, necessary to link capital management to value creation, while accurately and promptly monitoring cost (in terms of capital absorbed by potential losses) and benefits (in terms of net profits) generated by different types of risks.

5.15 Traditional approaches to bank regulation emphasise the positive features of capital adequacy requirements (Dewatripont and Tirole, 1994). Capital serves as a buffer against losses and hence failure. Capital adequacy requirements play a crucial role in aligning the incentives of bank owners with depositors and other creditors (Berger et al., 1995 and Keeley and Furlong, 1990). On the other hand, it has been argued that capital requirements may increase risk-taking behavior. If equity capital is more expensive to raise than deposits, then an increase in risk-based capital requirements tends to reduce banks’ willingness to screen and lend (Thakor, 1996). It has also been found that raising capital requirements forces banks to supply fewer deposits, which reduces the liquidity-providing role of banks (Gorton and Winton, 2000).

5.16 Capital that needs to be maintained should be consistent with the risk profile and operating environment. In pursuing this objective, banks need to put in place robust methodology for linking risk to capital such that capital is adequate given its risk profile. The risk management is required to establish the amount and type of risks that the bank is willing to take, collect enough capital resources to cover such risks and allocate capital to the business units that are in a position to produce the desired profit flow. This process does not occur once and for all, but requires a continuous adjustment. More specifically, the business areas that cannot reach the profitability target are required to be analysed, restructured and eventually abandoned. Specific amounts of a bank’s capital can be explicitly allocated to its various business lines (or to its business units), depending upon the bank’s strategic decisions. Moreover, the allocations can vary over time, for example, within a business cycle. They can be increased or decreased as business conditions in a particular area improve.

5.17 Capital management is concerned mainly with defining the optimal amount of capital the bank should hold (economic capital) and the optimal regulatory capital mix. Thus, the capital of an individual bank can be viewed as a mix of regulatory capital and economic capital (Box V.1). Both regulatory and economic capital are expected to cover unexpected losses resulting from banks’ business operations.Whereas regulatory capital is held compulsorily as a part of adherence to prudential regulations as per the national supervisor’s directions, economic capital is held beyond the minimum required level at banks’ own volition. Economic capital is defined by bank management for internal business purposes, without regard to the external risks the bank’s performance poses on the banking system or broader economy. Moreover, the amount of economic capital held, its form and the areas of a bank’s business that it supports, could vary from bank to bank. In contrast, regulatory capital requirements must set standards for solvency that support the safety and soundness of the overall banking system or broader economy. Though both types of capital differ in scope and substance, they are not mutually exclusive and are non-additive. Regulatory capital follows standardised definitions whereas economic capital is derived from bank-specific methodologies. Moreover, given the amount of capital that is necessary to tackle risks (economic capital) and to comply with the supervisors’ requirements (regulatory capital), the goal of value creation can be pursued also by optimising the composition of the capital collected by the bank so as to minimise its average unit cost. For this purpose, in addition to the ‘core’ shareholders’ capital, all the types of innovative and hybrid capital instruments can be used (for instance, preference shares, perpetual subordinated loans, contingent capital) that are available in the financial markets.

Box V.1 Economic Capital versus Regulatory Capital

Both regulatory and economic capital have to do with bank’s financial staying power; Economic and regulatory capital are not determined by the same set of variables and also do not respond in the same manner to changes in the common variables that affect them, such as the loans’ probability of default and loss given default. Regarding the determinants of economic and regulatory capital, while economic capital (EC) depends on the intermediation margin and the cost of bank capital, the regulatory capital depends on the confidence level set by the regulator. Hence, there does not exist a direct relationship between both capital levels. Variables that affect both economic and regulatory capital such as the loans’ probability of default and loss given default, have a positive impact on both capital levels for reasonable values of these variables, but when they reach certain critical values, their effect on economic capital becomes negative, increasing the gap with regulatory capital (Elizalde and Repullo, 2007). There are various methods for determining EC. A common methodology is to base EC on the probability of (statutory) ruin, which is the probability that liabilities will exceed assets on a present-value basis at a given future valuation date, resulting in technical insolvency. EC based on the probability of ruin is determined by calculating the amount of additional assets needed to reduce the probability of ruin to a target specified by management. When setting this target, management takes several factors into consideration that relate primarily to the solvency concerns of policyholders. The variables that only affect economic capital, such as the intermediation margin and the cost of capital, can account for large deviations from regulatory capital. The relative position of economic and regulatory capital is mainly determined by the cost of bank capital: economic capital is higher (lower) than regulatory capital when the cost of capital is low (high) (Elizalde and Repullo, 2007). To conclude, the two concepts reflect the needs of different primary stakeholders. For economic capital, the primary stakeholders are the bank’s shareholders, and the objective is the maximisation of their wealth. For regulatory capital, the primary stakeholders are the bank’s depositors, and the objective is to minimise the possibility of loss (Allen, 2006). With the regulatory tendency in recent years to come closer to credit risk modelling and to allow banks to develop their own models for determining the amount of regulatory capital to hold, comparing the current regulatory and economic capital is becoming an insightful exercise for the regulatory decisions of the future (Zhu, 2007).

References:

Allen, B. 2006. “Internal Affairs,” Risk, 19, June, 45-49.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2004.

International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework, Basel.

Carey, M. 2001. “Dimensions of Credit Risk and their Relationship to Economic Capital Requirements,” in F. S. Mishkin (ed.), Prudential Supervision: Why Is It Important and What Are the Issues, Chicago: University of Chicago Press and NBER.

Caruana, J. 2005. “Basel II: Back to the Future,” 7th Hong Kong Monetary Authority Distinguished Lecture, available at http://www.bde.es/ prensa/intervenpub/gobernador/ 040205e.pdf.

Elizalde, A. and R. Repullo. 2007. “Economic and Regulatory Capital in Banking: What is the Difference?” International Journal of Central Banking, 3(3), September.

Jones, D., and J. Mingo. 1998. “Industry Practices in Credit Risk Modelling and Internal Capital Allocations: Implications for a Models-Based Regulatory Capital Standard.” FRBNY Economic Policy Review, October.

Zhu, H. 2007. “Capital Regulation and Banks’ Financial Decisions”. BIS Working Papers No 232, July.

III. BASEL NORMS ON CAPITAL ADEQUACY

5.18 Internationally, there were no explicit capital adequacy standards before the introduction of Basel I norms in 1988. The most common approach was to lay down minimum capital requirements for banks in the respective banking legislations and determine the relative strength of capital position of a bank by ratios such as debt-equity ratio, or its other variants for measuring the level of leverage. Though capital regulation in banking existed even before the Basel Accord of 1988, there were vast variations in the method and timing of its adoption in different countries. In the pre-Basel phase, the use of capital ratios to establish minimum regulatory requirements was being tested for more than a century. In the US, between 1864 and 1950s, the supervisors did (i) try to make use of a variety of capital adequacy measures such as static minimum capital requirements based on the population of each bank’s service area, ratios of capital-to-total deposits and capital-to-total assets; (ii) adjust assets for risk; and (iii) create capital-to-risk-assets ratios, but none was universally accepted at that time. Even the banking sector was in favour of a more subjective system where the regulators could decide which capital requirements were suited for a particular bank as a function of its risk profile (Laurent, 2006).

5.19 Early attempts to evolve a new financial architecture can be traced to the collapse of Bretton Woods system coupled with oil shocks of 1973-74. The introduction of flexible exchange rates, divergence of interest and inflation rates, emergence of new technology oriented companies which resulted in collapse of some of the traditional ‘brick and mortar companies’ led to many institutional failures. This in turn, led to the demand for Government intervention and new financial architecture (Kapstein, 2006). The G-10 central bankers met in June 1974, but failed to evolve a consensus. The US argued for an explicit signalling of lender of the last resort facility, while the Germans were on the other side citing lack of mandate and the moral hazard problem. However, the failure of the talks led to the exclusion of many small banks from the inter-bank market which resulted in strong political pressure on the central bankers to meet again in September 1974. In the meeting, concern was expressed about the inadequate supervision of international banking and an assurance was given that the means for the provision of temporary liquidity be made available, which could be used as and when necessary. In the autumn of 1974, the Bank of England began to conceptualise the formation of a G-10 group of bank supervisors leading to the formation of the Standing Committee on Banking Regulation and Supervisory Practices, or the Basel Committee in December 1974. The initial mandate of the Committee was for sharing of and application of each others’ knowledge, rather than any comprehensive attempt to harmonise cross-country supervision. Nevertheless, it led to an unimaginable degree of regulatory harmonisation later.

5.20 The approach of regulation prescribed by the Committee focussed on home country control with no institution escaping supervision instead of multilateral surveillance of the supervisory arrangements. As a first step towards home country control, the Basel Committee in 1978 recommended that the use of consolidated financial statement for international banking supervision. While consolidated banking statements were a norm in the US and a few other countries, these were not so widespread in Europe. For example, in Germany, strict limits were placed on the ability of its supervisors to collect information about foreign activities of their banks. The emergence of macroeconomic weakness, more bank failures and diminishing bank capital triggered a regulatory response in 1981 when, for the first time, the federal banking agencies in the US introduced explicit numerical regulatory capital requirements. The standards adopted employed a leverage ratio of primary capital (which consisted mainly of equity and loan loss reserves) to average total assets. However, each regulator had a different view as to what exactly constituted bank capital. The debt crisis of August 1982 led to injection of liquidity and left a corresponding demand of institution of minimum capital standards. The inadequate capitalisation of Japanese banks and differing banking structures (universal banks of Germany vis-à-vis narrow banks of US) and varying risk profile of individual banks made agreement on capital standards difficult.

5.21 Over the next few years, regulators worked to converge upon a uniform measure. The Congress in the US passed legislations in 1983, directing the federal banking agencies to issue regulations addressing capital adequacy. The legislation provided the impetus for a common definition of regulatory capital and final uniform capital requirements in 1985. By 1986, regulators in the US were concerned that the primary capital ratio failed to differentiate among risks and did not provide an accurate measure of the risk exposures associated with innovative and expanding banking activities, most notably off-balance-sheet activities at larger institutions.

5.22 Regulators in the US began studying the risk-based capital frameworks of other countries – France, the UK and West Germany had implemented risk-based capital standards in 1979, 1980 and 1985, respectively. The agencies also revisited the earlier studies of risk-based capital ratios. A proposal by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, for example, assigned asset categories based on credit risk, interest rate risk and liquidity risk factors. The regulators agreed that the definition of capital adequacy needed to be better tailored to bank risk-taking in order to address two major trends in the banking industry. First, banks were moving away from safer, but lower yielding, liquid assets. At the same time, they were increasing their off-balance-sheet activities, whose risks were not accounted for by the then capital ratios. The regulators wanted a new ‘risk asset ratio’ to serve as a supplemental adjusted capital ratio to be used in tandem with existing ratios of capital-to-total-assets, on the belief that this would allow the capital framework to explicitly and systematically respond to individual banking organisations’ risk profiles and account for a wider range of risky practices. However, leading the initiative in 1987, the US joined the UK in announcing a bilateral agreement on capital adequacy, soon to be joined by Japan (buoyed by a booming stock market in raising capital). Subsequently in December 1987 ‘international convergence of capital measures and capital standards’, i.e., Basel Accord (now Basel I) was achieved. In July 1988, the Basel I Capital Accord was created.

5.23 The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), thus, had been making efforts over several years to secure international convergence of supervisory regulations governing the capital adequacy of international banks. The Committee after a consultative process, whereby the proposals were circulated not only to the central bank Governors of G-10 countries, but also to the supervisory authorities worldwide, finalised the Basel Capital Accord in 1988 (now popularly known as Basel I). The Committee’s work on regulatory convergence had two fundamental objectives. One, the framework should serve to strengthen the soundness and stability of the international banking system. Two, the framework should be fair and have a high degree of consistency in its application to banks in different countries with a view to diminishing an existing source of competitive inequality among international banks.

5.24 Three main components of the Basel I framework were constituents of capital, the risk weighting system, and the target ratio. The central focus of this framework was credit risk and, as a further aspect of credit risk, country transfer risk. Capital, for supervisory purposes was defined in two tiers. At least 50 per cent of a bank’s capital base was to consist of core elements comprising equity capital and published reserves from post-tax retained earnings (Tier 1). The other elements of capital (supplementary capital) (Tier 2) were allowed up to an amount equal to that of the core capital. These supplementary capital elements and the particular conditions attaching to their inclusion in the capital base were prescribed in detail. Tier 2 or supplementary capital comprised unpublished or hidden reserves, revaluation reserves, general provisions/general loan loss reserves, hybrid debt capital instruments, and subordinated term debt.

5.25 The Committee recommended a risk-weighted assets ratio in which capital was related to different categories of asset or off-balance-sheet exposure, weighted according to broad categories of relative riskiness, as the preferred method for assessing the capital adequacy of banks - other methods of capital measurement were considered supplementary to the risk-weight approach. The risk weighted approach was preferred over a simple gearing ratio approach because (i) it provided a fairer basis for making international comparisons among banking systems whose structures might differ; (ii) it allowed off-balance-sheet exposures to be incorporated more easily into the measure; and (iii) it did not deter banks from holding liquid or other assets which carried low risk. There were inevitably some broad-brush judgements in deciding which weight should apply to different types of asset and the framework of weights was kept as simple as possible with only five weights being used for on balance-sheet items, i.e., 0, 10, 20, 50 and 100 per cent. Government bonds of the countries that were members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (which includes all members of the Basel Committee) were assigned a zero risk weight, all short-term inter-bank loans and all long-term inter-bank loans to banks headquartered in OECD countries a 20 per cent risk weight, home mortgages a 50 per cent risk weight, and most other loans a 100 per cent risk weight. The capital adequacy ratio was prescribed at eight per cent.

5.26 Basel I originally focused on credit risk, a major source of risk for most banks. Banks, however, developed new types of financial transactions that did not fit well into the risk weights and credit conversion factors in the laid down standards. For instance, there was a significant growth in securitisation activity, which banks engaged in partly as regulatory arbitrage opportunities. In order to respond to emerging risks, the Basel Committee members in 1996 adopted the Market Risk Amendment, which required capital for market risk exposures arising from banks’ trading activities. Thus, through this amendment an explicit capital cushion was provided for the price risks to which banks were exposed, particularly those arising from their trading activities. The amendment covered market risks arising from banks’ open positions in foreign exchange, traded debt securities, traded equities, commodities and options. The novelty of this amendment lay in the fact that it allowed banks to use, as an alternative to the standardised measurement framework originally put forward in April 1993, their internal models to determine the required capital charge for market risk. The standard approach defined the risk charges associated with each position and specified how these charges were to be aggregated into an overall market risk capital charge. The minimum capital requirement was expressed in terms of two separately calculated charges, one applying to the ‘specific risk’ of each security, whether it was a short or a long position, and the other to the interest rate risk in the portfolio (termed ‘general market risk’) where long and short positions in different securities or instruments could be offset.

5.27 The major achievement of the Basel Capital Accord 1988 was the introduction of discipline through imposition of risk-based capital standards both as measure of the strength of banks and as a trigger device for supervisors’ intervention under the scheme of prompt corrective action (PCA). Over the years, however, several deficiencies of the design of the Basel I framework surfaced. The Basel I capital adequacy norms were criticised for the simple ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that did not adequately differentiate between assets that have different risk levels. This standard encouraged capital arbitrage through securitisation and off-balance sheet exposures. The Basel rules encouraged some banks to move high quality assets off their balance sheet, thereby reducing the average quality of bank loan portfolios. Furthermore, banks took large credit risks in the least creditworthy borrowers who had the highest expected returns in a risk-weighted class (Kupiec, 2001). The approach incorrectly assumed that risks were identical within each bucket and that the overall risk of a bank’s portfolio was equal to the sum of the risks across the various buckets. But, most of the times, the risk-weight classes did not match realised losses (Flood, 2001).

5.28 Securitisation of banks’ credit portfolios became a widespread phenomenon in industrialised countries. At first, banks used to sell their mortgage loans, for such loans represented accurately evaluated risks. But after the advent of e-finance, it became possible to expand this activity to other types of loans, including those made to small businesses. This type of activity also allowed banks to have a much more liquid credit-risk portfolio and, in theory, to adjust their capital ratio to an optimal economic level rather than sticking to the ratio prescribed by the Basel Committee.

5.29 Moreover, diversification of a bank’s credit-risk portfolio was not taken into account in the computation of capital ratios. The aggregate risk of a bank was not equal to the sum of its individual risks –diversification through the pooling of risks could significantly reduce the overall portfolio risk of a bank. Indeed, a well-established principle of finance is that the combination in a single portfolio of assets with different risk characteristics can produce less overall risk than merely adding up the risks of the individual assets. The Accord, however, did not take into account the benefits of portfolio diversification.

5.30 Basel I offered only a limited recognition of credit risk mitigation techniques. In addition, significant financial innovations that occurred after Basel I suggested that a bank’s regulatory capital ratios might not always be useful indicators of its underlying risk profile. Financial crises of the 1990s involving international banks highlighted several additional weaknesses in the Basel standards that permitted and in some cases, even encouraged, excessive risk taking and misallocations of bank credit (White, 2000). Basel I did not explicitly address all the risks faced by banks such as liquidity risk, and operational risks that may be important sources of insolvency exposure for banks.

5.31 Despite the amendment to the original framework in 1996, the simple risk weighting approach of Basel I did not keep pace with more advanced risk measurement approaches at large banking organisations. By the late 1990s, some large banking organisations, especially in advanced countries had begun developing economic capital models, which used quantitative methods to estimate the amount of capital required to support various elements of an organisation’s risks. Banks used economic capital models as tools to inform their management activities, including measuring risk-adjusted performance, setting pricing and limits on loans and other products, and allocating capital among various business lines and risks. Economic capital models measure risks by estimating the probability of potential losses over a specified period and up to a defined confidence level using historical loss data. These models make more meaningful risk measurement than the Basel I regulatory framework, which differentiates risk only to a limited extent, mostly based on asset type rather than on an asset’s underlying risk characteristics.

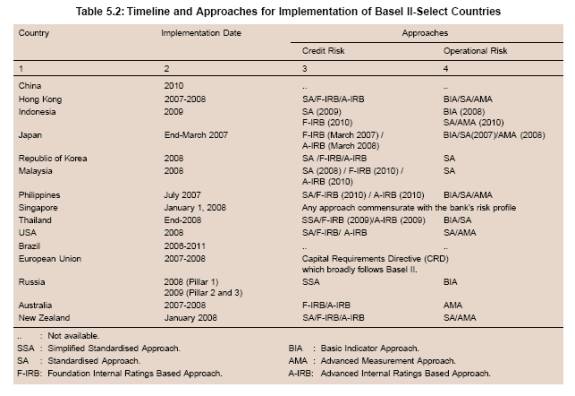

5.32 The Basel Committee itself recognised the deficiencies in the Basel I framework. The rapid rate of innovation in financial markets and the growing complexity of financial transactions reduced the relevance of Basel I as a risk managing framework, especially for large and complex banking organisations. Various shortcomings also distorted the behaviour of banks and made it much more complicated to monitor them. With a view to addressing the shortcomings of Basel I, the BCBS introduced a new capital adequacy framework for International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards (Basel II) in June 2004 to replace the 1988 Capital Accord by year-end 2007 (Box V.2). Basel II norms aim at aligning minimum capital requirements to banks’ underlying risk profiles. The framework is also designed to create incentives for better r isk measurement and management. Major features of Basel II framework are presented below.

Pillar 1: Capital Adequacy

5.33 Under Pillar 1, commercial banks are required to compute individual capital adequacy for three categories of risks (i.e., credit risk, market risk and operational risk) broadly under two sets of approaches – standardised and advanced.

Capital Charge for Credit Risk

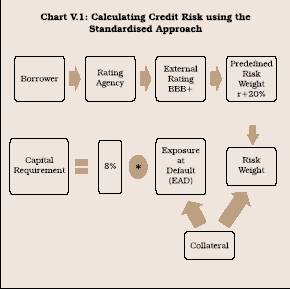

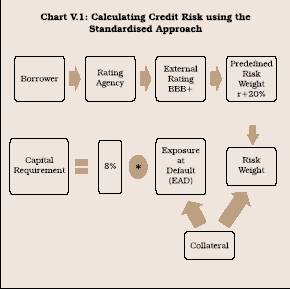

5.34 Basel II marks a break from Basel I in the case of credit risk in that the loans to similar counterparts such as private firms, sovereigns etc., require different capital coverage, depending upon their riskiness as evaluated by some external rating agency, or by the bank itself. Basel II proposes a range of approaches to credit risk. The simplest methodology is the standardised approach which aligns regulatory capital requirements more closely with the key elements of banking risk by introducing a wider differentiation of risk weights and a wider recognition of credit risk mitigation techniques, while avoiding excessive complexity. In this method, risk weights are defined for certain types of credit exposures primarily on the basis of credit assessments provided by rating agencies. The default risk as reflected in the credit rating is then translated into the resulting capital requirements (Chart V.1).

5.35 The standardised approach, however, does not differentiate between expected and unexpected losses. Expected losses should be calculated as standard risk costs in the credit approval process. The actual credit risk, which refers to a ‘potential surprise loss’ thus only comprises the unexpected loss beyond the expected loss assumed in the calculation of standard risk costs. In order to ensure that these data can be compared and aggregated with other risks (for instance, market risks), the unexpected loss should be used as the uniform basis for risk measurement. Regardless of whether a distinction is drawn between expected and unexpected loss, the most important criterion in selecting suitable risk quantification methods is their risk orientation (i.e., increased risk requires increased capital).

5.36 Under the internal rating based (IRB) approach, banks that have received supervisory approval, arrive at their own internal estimates of risk components in determining the capital requirement for a given exposure. The risk components include measures of the probability of default (PD) – the probability that counterparty will default within one year, loss given default (LGD) – the amount of the loss expressed as a percentage of the amount outstanding at the time when the counterparty defaults, the exposure at default (EAD) – the credit amount outstanding at the time of default, and effective maturity (M). In some cases, banks may be required to use a supervisory value as opposed to an internal estimate for one or more of the risk components.

Box V.2 Basel II Norms: Main Elements

While the Basel I framework was confined to the minimum capital requirements for banks, the Basel II accord expands this approach to include two additional areas, viz., the supervisory review process and increased disclosure requirements for banks. In terms of Basel II, the stability of the banking system rests on the following three pillars, which are designed to reinforce each other: (i) Pillar 1: Minimum Capital Requirements - a largely new, risk-adequate calculation of capital requirements which (for the first time) explicitly includes operational risk in addition to market and credit risk; (ii) Pillar 2: Supervisory Review Process (SRP) -the establishment of suitable risk management systems in banks and their review by the supervisory authority; and (iii) Pillar 3: Market Discipline - increased transparency due to expanded disclosure requirements for banks.

The central focus of this framework as in Basel I, continues to be credit risk. In the revised framework, the minimum regulatory capital requirements take into account not just credit risk and market risk, but also operational risk. The measures for credit risk are more complex, for market risk they are the same, while those for operational risk are new. Besides, Basel II includes certain Pillar 2 risks such as credit concentration risks and liquidity risks.

Apart from an increase in the number of risks, banks are required to achieve a more comprehensive risk management framework. While Basel I required lenders to calculate a minimum level of capital based on a single risk weight for each of the limited number of asset classes, under Basel II, the capital requirements are more risk sensitive. The credit risk weights are related directly to the credit rating of each counterparty instead of the counterparty category.

Basel II capital adequacy rules are based on a ‘menu’ approach that allows differences in approaches in relationship to the nature of banks and the nature of markets in which they operate (Table 1). The minimum requirements for the advanced approaches are technically more demanding and require extensive databases and more sophisticated risk management techniques. Basel II prescriptions have ushered in a transition from capital adequacy to capital efficiency which implies that banks adopt a more dynamic use of capital, in which capital will flow quickly to its most efficient use. Unlike Basel I, Basel II is quite complex as it offers choices, some of which involve application of quantitative techniques.

Basel II - Main Features

5.37 Under the IRB approach, banks must categorise banking-book exposures with different underlying risk characteristics into broad classes of assets, viz., (a) corporate, (b) sovereign, (c) bank, (d) retail, and (e) equity. One essential pre-requisite for calculating unexpected loss is the availability of default probabilities (PDs). As it is also possible to rely on predefined supervisory values for the other risk parameters (LGD, EAD, M), the bank’s internal calculation of default probabilities constitutes the central indicator in calculating a simple credit value at risk under the IRB Approach. Thus, the advanced approach for credit risk uses risk parameters determined by a bank’s inter nal system for calculating minimum regulatory capital. In comparison with standardised approach, the IRB approach is more risk sensitive. However, such methods also increase the complexity of capital calculation.

Risk Mitigation Techniques

5.38 Historically, banks have been using various techniques like guarantees and security to support obligations of the borrowers. In recent years, credit intermediation has been vastly facilitated by the proliferation of complex risk transfer instruments, including credit derivatives and various types of asset-backed securities. One consequence is that a large number of banks shifted to ‘originate-to-distribute’ business models, transferring risk to other investors. In the calculation of capital requirements under Basel II, various credit risk mitigation techniques can be used in order to limit credit risk. Under the standardised approach, these include financial collateral as well as guarantees and credit derivatives. Basel II better assesses the risk inherent in arrangements using evolving technologies, such as securitisation and credit derivatives, that are used to buy and sell credit risk. Basel II also establishes benchmarks for recognising risk transfer and mitigation in securitisation and credit derivatives structures. It sets a boundary between the point at which a firm transfers risk and actually retains the risk. The Basel II framework suggests ‘operational requirements’ that must be met before an originating bank is able to recognise the transfer of the assets, or the risk related to them, and to exclude the assets from its risk-based capital calculations.

Capital Charge for Operational Risk

5.39 Operational risk has been defined by the BCBS ‘as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events’. This definition includes legal risk, but excludes strategic and reputational risk. The most important types of operational risk involve breakdowns in internal controls and corporate governance. Such breakdowns can lead to financial losses through error, fraud, or failure to perform in a timely manner or cause the interests of the bank to be compromised in some other way, for example, by its dealers, lending officers or other staff exceeding their authority or conducting business in an unethical or risky manner. Other aspects of operational risk include major failure of information technology systems or events such as major fires or other disasters.

5.40 Two important indicators of operational risk are the size and complexity of a bank. As the number of employees, business par tners, customers, branches, systems and processes at a bank increases, its risk potential also tends to rise. Other operational risk indicator is process intensity, i.e.,number of lawsuits filed against a bank. In cases where business operations (for instance, the processing activities mentioned above) are outsourced, the bank cannot automatically assume that operational risks have been eliminated completely. This is because a bank’s dependence on an outsourcing service provider means that risks incurred by the latter can have negative repercussions on the bank. Therefore, the content and quality of the service level agreement as well as the quality (for instance, ISO certification) and creditworthiness of the outsourcing service provider can also serve as risk indicators in this context.

5.41 Various methods can be used to assess operational risks. The Basel II framework has given guidance to three broad methods of capital calculation for operational risk – basic indicator approach (which is based on annual revenue of the financial institution), standardised approach (which is based on annual revenue of each of the broad business lines of the financial institution) and advanced measurement approaches (which are based on the internally developed risk measurement framework of the bank adhering to the standards prescribed and include methods such as internal measurement approach (IMA), loss distribution approach (LDA), scenario-based, and scorecard).

5.42 The basic indicator approach (for the calculation of minimum capital requirements) is the simplest method of quantifying operational risks. In this approach, a risk weight of 15 per cent is applied to a single indicator, specifically the average gross income (i.e., the sum of net interest income and net non-interest income) over the previous three years. The advantage of applying the basic indicator approach primarily lies in its simplicity. However, there is no immediate causal relationship between bank’s operational risks and its operating income. In order to come to a better assessment of the risk profile, it is advisable not to rely on the basic indicator approach alone to capture risks. For instance, a more specific calculation of a bank’s risk situation can be performed by means of a systematic internal survey of realised operational risks using a loss database.

5.43 Under the standardised approach, operational risk is also calculated exclusively on the basis of the risk indicator described above. However, in this case the indicator is not calculated for the bank as a whole, but individually for specific business lines as defined by the supervisory authority (retail, corporate, trading, etc.). Accordingly, the standardised approach includes not only a risk weight of 15 per cent, but specific risk weights defined for each business line. This means that applying the standardised approach basically involves the same problems as applying the basic indicator approach. Advanced measurement approaches provide banks with substantial flexibility and do not prescribe specific methodologies or assumptions. However, they do specify several qualitative and quantitative standards to be met by banks before adopting these approaches. Such methods could be used to aptly reflect the bank’s risk profile, but their design and implementation involve high levels of effort. The quantification models for operational risk using internal methods are currently in the developmental stage.

5.44 While Basel II is an international framework based on shared regulatory objectives, it is subject to country-specific implementation. Therefore, a country has the discretion to use multiple risk-based capital regimes depending on the banking organisation’s size and complexity. Since the international accord was issued in 2004, individual countries have been implementing national rules based on the principles and detailed framework that it sets forth, and each country has used some measure of national discretion within its jurisdiction. The Basel Committee noted that as a result, regulators from different countries would need to make substantial efforts to ensure sufficient consistency in the application of the framework across jurisdictions. Furthermore, the Basel Committee emphasised that the international accord set forth only minimum requirements, which countries may choose to supplement with added measures to address such concerns as potential uncertainties about the accuracy of the capital rule’s risk measurement approaches.

Pillar 2: Supervisory Review

5.45 On the one hand, Pillar 2 (Supervisory Review Process) requires banks to implement an internal process for assessing their capital adequacy in relation to their risk profiles as well as a strategy for maintaining their capital levels, i.e., the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP). On the other hand, Pillar 2 also requires the supervisory authorities to subject all banks to an evaluation process and to impose any necessary supervisory measures based on the evaluations (Box V.3).

5.46 The dynamic growth of financial markets and the increased use of complex bank products have brought about new challenges before credit institutions, which have highlighted the need for functioning systems aimed at containment and targeted control of each institution’s risk position. Banks are required to employ suitable procedures and systems in order to ensure adequate capital in the long-term with due attention to all material risks. These procedures are collectively referred to as the ICAAP. The selection and suitability of methods depend heavily on the complexity and scale of each individual institution’s business activities.

Box V.3 Principles for the Supervisory Review Process

The Basel Committee has defined the following four basic principles for the supervisory review process.

Principle 1: Banks should have a process for assessing their overall capital adequacy in relation to their risk profile and a strategy for maintaining their capital levels.

Principle 2: Supervisors should review and evaluate banks’ internal capital adequacy assessments and strategies, as well as their ability to monitor and ensure their compliance with regulatory capital ratios. Supervisors should take appropriate supervisory action if they are not satisfied with the result of this process.

Principle 3: Supervisors should expect banks to operate above the minimum regulatory capital ratios and should have the ability to require banks to hold capital in excess of the minimum.

Principle 4: Supervisors should seek to intervene at an early stage to prevent capital from falling below the minimum levels required to support the risk characteristics of a particular bank and should require rapid remedial action if capital is not maintained or restored.

Essentially, these include evaluations of the banks’ internal processes and strategies as well as their risk profiles, and if necessary taking prudential and other supervisory actions.

Reference:

Bank for International Settlements. 2006. Basel II: International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework - Comprehensive Version, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, June.

5.47 The main motive for introducing the ICAAP is to ensure a viable risk position by dealing with risks in the appropriate manner. In particular, it is important to detect, at the earliest possible, developments which may endanger the institution in order to enable the bank to take suitable countermeasures. There are two basic objectives of ICAAP. The main objective of the ICAAP is to secure the institution’s risk-bearing capacity. When calculating the bank’s risk bearing capacity, it is necessary to determine the extent to which a bank can afford to take certain risks. For this purpose, the bank needs to ensure that the available risk coverage capital is sufficient at all times to cover the risks taken. Secondly, the bank must review the extent to which risks are worth assuming, that is, it is necessary to analyse the opportunities arising from risk taking (evaluation of the risk and return). The ICAAP thus constitutes a comprehensive package which delivers significant benefits from a business perspective.

5.48 An essential prerequisite for analysing the risk-bearing capacity is to assess all of a bank’s material risks and aggregate them to arrive at the bank’s overall risk position (Box V.4). The purpose of assessing risks is to depict the significance and effects of risks taken on the bank. Banks need to implement efficient and appropriate stress testing framework and assess the impact not only of specific events, but also the impact of various scenarios. In the first step, a bank needs to use risk indicators to assess which of its risks are actually material. In the second step, the bank needs to quantify its risks, wherever possible. The results of these impact studies need to be integrated into capital planning and business strategy. Finally, the bank needs to calculate the internal capital required to cover its risks.

Pillar 3: Market Discipline

5.49 Theoretically, regulation aimed at creating and sustaining competition among banks, notably through increased transparency, is believed to play an important role in mitigating bank solvency problems. Market discipline in the banking sector can be described as private counterparty supervision that has always been the first line of regulatory defence in protecting the safety and soundness of the banking system (Greenspan, 2001). Some authors have drawn attention to market pressure as an explanation for the rapid acceptance and diffusion of the Basel capital adequacy standards (Genschel and Plümper, 1997). Their contention is that these standards have increased transparency, thereby enabling financial markets to ‘punish’ poorly capitalised banks and rewarding banking systems with higher capital levels. Banks with higher capital ratios may be able to access the capital market for raising resources, which, in turn, allow banks to maintain higher capital levels.

5.50 The purpose of market discipline (detailed in Pillar 3) in the revised framework is to complement the minimum capital requirements (detailed under Pillar 1) and the supervisory review process (detailed under Pillar 2). The aim is to encourage market discipline by developing a set of disclosure requirements which will allow market participants to assess key pieces of information on the scope of application, capital, risk exposures, risk assessment processes, and hence the capital adequacy of the institution. In principle, banks’ disclosures should be consistent with how senior management and the board of directors assess and manage the risks of the bank.

Box V.4 Assessment of Risks

The area of validation might emerge as a key challenge for banking institutions in the foreseeable future. At present, few banks possess processes that both span the range of validation efforts listed and address all elements of model uncertainty. The components of model validation can be grouped into four broad categories: (a) backtesting, or verifying that the ex ante estimation of expected and unexpected losses is consistent with ex post experience; (b) stress testing, or analysing the results of model output given various economic scenarios; (c) assessing the sensitivity of credit risk estimates to underlying parameters and assumptions; and (d) ensuring the existence of independent review and oversight of a model.

Backtesting

The methodology applied to backtesting market risk VaR models is not easily transferable to credit risk models due to the data constraints. The Market Risk Amendment requires a minimum of 250 trading days of forecasts and realised losses. A similar standard for credit risk models would require an impractical number of years of data given the models’ longer time horizons.

Given the limited availability of data for out-of-sample testing, backtesting estimates of unexpected credit loss are certain to be problematic in practice. It is difficult to find a formal backtesting programme for validating estimates of credit risk – or unexpected loss. Where analyses of ex ante estimates and ex post experience are made, banks typically compare estimated credit risk losses to a historical series of actual credit losses captured over some years. However, the comparison of expected and actual credit losses does not address the accuracy of the model’s prediction of unexpected losses, against which economic capital is allocated. While such independent work on backtesting is limited, some literature indicates the difficulty of ensuring that capital requirements generated using credit risk models will provide an adequately large capital buffer.

Banks employ various alternative means of validating credit risk models, including so-called ‘market-based reality checks’ such as peer group analysis, rate of return analysis and comparisons of market credit spreads with those implied by the bank’s own pricing models. However, the assumption underlying these approaches is that prevailing market perceptions of appropriate capital levels (for peer analysis) or credit spreads (for rate of return analysis) are substantially accurate and economically well founded. If this is not so, reliance on such techniques raises questions as to the comparability and consistency of credit risk models, an issue which may be of particular importance to supervisors.

Stress Testing

Stress tests aim to overcome some of the major uncertainties in credit risk models – such as the estimation of default rates or the joint probability distribution of risk factors – by specifying particular economic scenarios and judging the adequacy of bank capital against those scenarios, regardless of the probability that such events may occur. Stress tests could cover a range of scenarios, including the performance of certain sectors during crises, or the magnitude of losses at extreme points of the credit cycle.

In theory, a robust process of stress testing could act as a complement to backtesting given the limitations inherent in current backtesting methods. However, there is no ideal framework or single component of best practice on stress testing, and industry practices vary widely. In 2004, the Committee on the Global Financial System conducted an extensive survey covering 64 banks and securities firms from 16 countries (BIS, 2005). More than 80 per cent of the stress tests reported were based on trading portfolios. The use of stress tests has expanded from the exploration of exceptional but plausible events, to encompass a range of applications. Among the major challenges are those related to stress testing credit risk, integrated stress testing and the treatment of market liquidity in stress situtations.

With respect to stressed conditions, Basel II has advanced comprehensive stress testing frameworks. The Basel II framework requires that stress scenarios capture the effects of a downturn on market and credit risks, as well as on liquidity. Such an improved firm-wide approach to risk assessment is essential for ensuring that banks have a sufficient capital buffer that will carry them through difficult periods.

Sensitivity Analysis

The practice of testing the sensitivity of model output to parameter values or to critical assumptions is also not common. In the case of certain proprietary models, some parameter (and even structural) assumptions are unknown to the user, and thus sensitivity testing and parameter modification are difficult.

According to a survey conducted by the BCBS, a minority of banks indicated they conduct sensitivity analysis on a number of factors, including: (a) Expected Default Frequency (EDF) and volatility of EDF; (b) LGD, and (c) assignment of internal rating categories (BIS, 2000). However, the depth of the analysis differed between the 54 respondent banks. Furthermore, none of the respondents attempted to quantify the degree of potential error in the estimation of the probability distribution of credit losses, though a few compared the results generated by the internal model with those from a vendor model.

Management Oversight and Reporting

The mathematical and technical aspects of validation are important. Equally important, however, is the internal environment in which a model operates. The amount of senior manager oversight, the proficiency of loan officers, the quality of internal controls and other traditional features of the credit culture will continue to play a key part in the risk management framework.

References:

Riskmetrics Group. 1999. Risk Management: A Practical Guide.

Bank for International Settlements. 2000. Range of Practices in Banks’ Internal Rating Systems, January.

Bank for International Settlements. 2005. Stress Testing at Major Financial Institutions : Survey Results and Practice, January.

5.51 Non-compliance with the prescribed disclosure requirements would attract a penalty, including financial penalty. However, direct additional capital requirements rarely serve as a response to non-disclosure, except in certain cases. In addition to the general intervention measures, the revised framework also anticipates a role for specific measures. Where disclosure is a qualifying criterion under Pillar 1 to obtain lower risk weights and/or to apply specific methodologies, there would be a direct sanction (not being allowed to apply the lower risk weighting or the specific methodology).

IV. ADVANTAGES, LIMITATIONS, ISSUES AND CHALLENGES OF BASEL II

5.52 The main incentives for adoption of Basel II are (a) it is more risk sensitive; (b) it recognises developments in risk measurement and risk management techniques employed in the banking sector and accommodates them within the framework; and (c) it aligns regulatory capital closer to economic capital. These elements of Basel II take the regulatory framework closer to the business models employed in several large banks. In Basel II framework, banks’ capital requirements are more closely aligned with the underlying risks in the balance sheet. Basel II compliant banks can also achieve better capital efficiency as identification, measurement and management of credit, market and operational risks have a direct bearing on regulatory capital relief. Operational risk management would result in continuous review of systems and control mechanisms. Capital charge for better managed risks is lower and banks adopting risk-based pricing are able to offer a better price (interest rate) for better risks. This helps banks not only to attract better business but also to formulate a business strategy driven by efficient risk-return parameters. However, competition in the market where pricing is controlled by market might override the risk-based pricing. Risk levels enable estimation of risk appetite and capital allocation. Marketing of products thus becomes more focused/targeted.

5.53 The movement towards Basel II has prompted banks to make necessary improvement in their risk management and risk measurement systems. Basel II would improve the collection and use of data so that they could aggregate and better understand information about their risk portfolios. For instance, the framework requires fundamental improvement in the data supporting the probability of default (PD), exposure at default (EAD) and loss given default (LGD)2 estimates that underpin economic and regulatory capital assessments over an economic cycle. This has spurred improvements in areas such as data collection and management information systems. These advances, along with the incentives to improve risk management practices, will support further innovation, and improvement in risk management and economic capital modelling. Basel II incorporates much of the latest ‘technology’ in the financial arena for managing risk and allocating capital to cover risk. Thus, banks would be required to adopt superior technology and information systems which aid them in better data collection, support high quality data and provide scope for detailed technical analysis. The recent financial turmoil exhibited that even such technical analysis have their limitations, such as incomplete data or assumptions that have not been tested across business cycles. Therefore, quantitative assessment of risks also needs to be supplemented by qualitative measures and sound judgement.

5.54 Basel II goes beyond merely meeting the letter of the rules. Under Pillar 2, when supervisors assess economic capital, they are expected to go beyond banks’ systems. Pillar 2 of the framework provides greater scope for bankers and supervisors to engage in a dialogue, which ultimately will be one of the important benefits emanating from the implementation of Basel II.

5.55 The added transparency in Pillar 3 should also generate improved market discipline for banks, in some cases forcing them to run a better business. Indeed, market participants play a useful role by requiring banks to hold more capital than implied by minimum regulatory capital requirements - or sometimes their own economic capital models - and by demanding additional disclosures about how risks are being identified, measured, and managed. A strong understanding by the market of pillars 1 and 2 would make Pillar 3 more comprehensible and market discipline a more reliable tool for supervisors and the market.

5.56 The creation of a more risk sensitive framework for capital regulation which is one of the key objectives of Basel II is expected to provide supervisors, banks and other market participants with a measure of capital adequacy that better reflects the true financial condition of a large bank. A more risk sensitive minimum capital ratio is also intended to encourage large banks to make lending, investment, and credit risk hedging decisions based on the underlying economics of the transactions. Moreover, increasing the risk sensitivity of the minimum capital requirements is intended to give large banks stronger incentives to manage and measure their own risk. Finally, Basel II sets minimum risk-based capital requirements at the level of the individual credit exposure, and in doing so sharply differentiates in terms of quality of credit.

5.57 According to a survey published by Ernst & Young3 , processes and systems are expected to change significantly, alongwith the ways in which risks are managed. Over three-quarters of respondents believed that Basel II will change the competitive landscape for banking. Those organisations with better risk systems are expected to benefit at the expense of those which have been slower to absorb change. Eighty-five per cent of respondents believed that economic capital would guide some, if not all, pricing. Greater specialisation was also expected, due to increased use of risk transfer instruments. A majority of respondents (over 70 per cent) believe that portfolio risk management would become more active, driven by the availability of better and more timely risk information as well as the differential capital requirements resulting from Basel II. This could improve the profitability of some banks relative to others, and encourage the trend towards consolidation in the sector.

5.58 For a given amount of capital, more risk-sensitive capital requirements could improve the safety and soundness of the banking system through a number of channels – each of which more closely aligns required capital with associated risks – and provide a required level of capital more likely to absorb unexpected losses. First, holding assets with higher risk under Basel II would require banks to hold more capital relative to lower risk assets. Second, banks with higher risk credit portfolios or greater exposure to operational risk would be required to hold relatively more capital than banks with lower risk profiles. For instance, a bank with a business line more susceptible to fraud, could face relatively higher capital requirements in those areas. Third, although more risk sensitive capital requirements can help enhance safety and soundness, the level of regulatory capital must also be sufficient to account for broader risks to the economy and safety and soundness of the banking system, which will require ongoing regulatory scrutiny.

5.59 In light of recent financial market turbulence, the importance of implementing Basel II capital framework and strengthening supervision and risk management practices, and improving the robustness of valuation practices and market transparency for complex and less liquid products, have assumed greater significance. Moreover, it is essential to have robust and resilient core firms at the centre of the financial system operating on safe and sound risk management practices (Box V.5). The Basel II plays an important role in this respect by ensuring the robustness and resilience of these firms through a sound global capital adequacy framework along with other benefits including greater operational efficiencies, better capital allocation and greater shareholder value through the use of improved risk models and reporting capabilities.

Limitations of Basel II

5.60 The Basel II framework also suffers from several limitations, especially from the angle of implementation in emerging economies. Compared to Basel I, Basel II is considered to be highly complex, making its understanding and implementation a challenge to both the regulators and the regulated entities, par ticularly in the emerging market economies. The complexity of Basel II arises from several options available. Consequently, many of the countries that have voluntarily adopted Basel I also view these issues with considerable caution. Since the revised Framework has been designed to provide options for banks and the banking systems worldwide, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) acknowledged that moving toward its adoption in the near future may not be the first priority for all non-G10 supervisory authorities in terms of what was needed to strengthen their supervision. It observed that each national supervisor was expected to consider carefully the benefits of the Basel II framework in the context of its domestic banking system when developing a timetable and approach for implementation. While it is true that the Basel II framework is more complex, at the same time, it has also been argued that this complexity is largely unavoidable mainly because the banking system and related instruments that have evolved in recent times are inherently complex in nature. The risk management system itself has become more sophisticated over the time and applying equal risk weights (as done in the Basel I accord) may not be realistic anymore. Moreover, for banks with straightforward business models and non-complex loan portfolios, the option to use the standardised approach in the Basel II framework is open, which adds very little in the way of complexity to their already existing models.

Box V.5 Effect of Recent Financial Turmoil on Basel II

The financial turmoil that occurred in mid-2007 - widely known as the sub-prime crisis - has affected the balance sheets of some major global financial institutions and has also resulted in market liquidity crisis. This turmoil was a fallout of an exceptional credit boom and leverage in the financial system. A long period of consistent economic growth and stable financial conditions had resulted in increased risk appetite of borrowers as well as investors. Financial institutions responded by expanding the market for securitisation of credit risk and aggressively developing the originate-to-distribute model for financial intermediation. A slowdown in the US real estate market triggered a series of defaults and this snowballed into accumulated losses, especially in the case of complex structured securities.

The build-up to and unfolding of the financial turmoil took place under the Basel I capital framework as most of the countries have started implementation of Basel II framework only recently. This financial turmoil has, in fact, highlighted many of the shortcomings of the Basel I framework, including its lack of risk sensitivity and its inflexibility to rapid innovations. Basel I created perverse regulatory incentives to move exposures off the balance sheet and did not fully capture important elements of bank’s risk exposure within the capital adequacy calculation.

In contrast, the Basel II framework has provision for better risk management practices by closely aligning the minimum capital requirements with the risks that banks face (Pillar 1), by strengthening supervisory review of bank practices (Pillar 2) and by encouraging improved market disclosure (Pillar 3).

Notwithstanding the improvements over the Basel I framework, the current Basel II framework still has certain deficiencies if evaluated in the light of current financial turmoil. Under the first pillar, a relook at the treatment of highly rated securitisation exposures, especially the so-called collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) of asset backed securities (ABS) is necessary. The role of this securitisation process in the current turmoil and its leverage capacity and their systemic implications have come under intense scrutiny in recent times. There is a pressing need to introduce a credit default risk charge for the trading book given the rapid growth of less liquid, credit sensitive products in banks’ trading books. These products include structured credit assets and leveraged lending and the VaR-based approach is insufficient for these types of exposures and needs to be supplemented with a default risk charge. Though banks are already required to conduct stress tests of their credit portfolio under the second pillar of the Basel framework to validate the adequacy of their capital cushions, the importance of conducting scenario analyses and stress tests of their contingent credit exposures, both contractual and non-contractual, need to be reemphasised. In Pillar 3, there are opportunities to further leverage off the types of disclosures required under Basel II.

Against this backdrop, several measures have been suggested for mitigating the impact and improving the global financial system. The most noteworthy among these are the proposals made by the Financial Stability Forum (FSF)1 and ratified in early April 2008 by the G-7 to be implemented over the next 100 days. By the mid-2008, the Basel Committee is expected to issue revised liquidity risk management guidelines and IOSCO is expected to revise its code of conduct for credit rating agencies. By end-2008 or at the latest by 2009, the BCBS is expected to revise capital requirements under Pillar 1 of Basel II (for instance, certain aspects of the securitisation framework), strengthening supervision and management of liquidity risk for banks, ensuring effective supervisory review under Pillar 2, enhancing transparency and valuation, improving the quality of credit ratings for structured products, strengthening authorities’ responsiveness to risk and enhancing robust arrangements for dealing with stress in the financial system.

References:

Financial Stability Forum. 2008. Report of the Financial Stability Forum on Enhancing Market and Institutional Resilience, April.

Buiter, W. 2007. “Lessons from the 2007 Financial Crisis”,

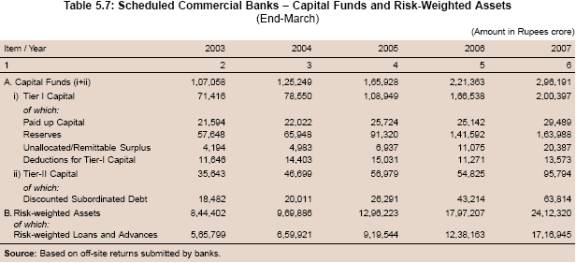

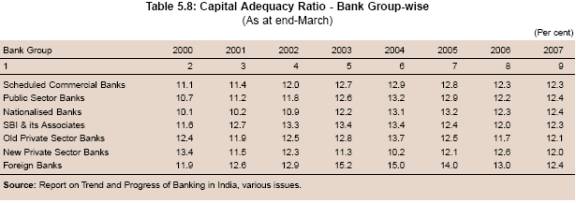

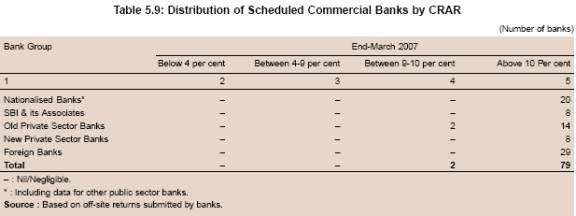

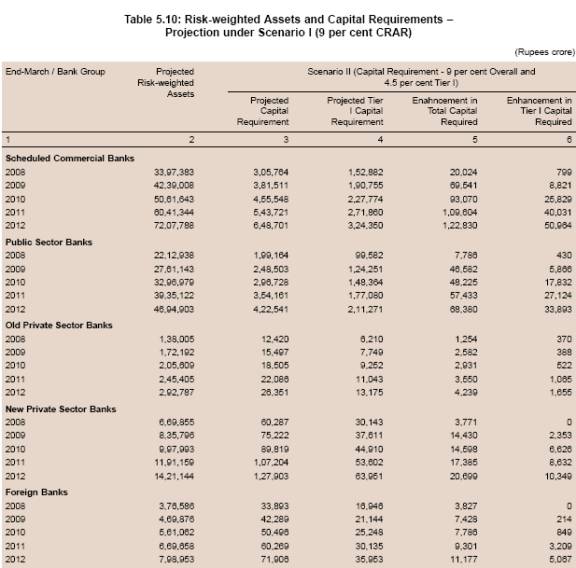

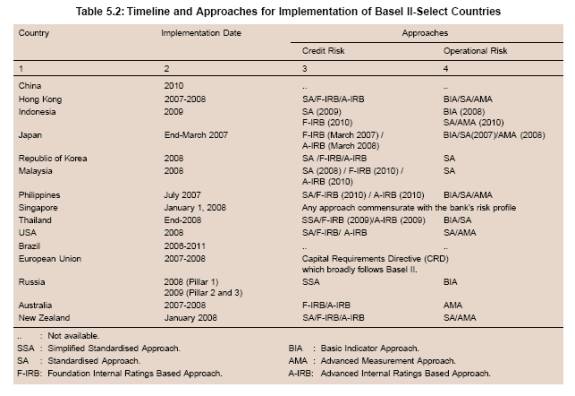

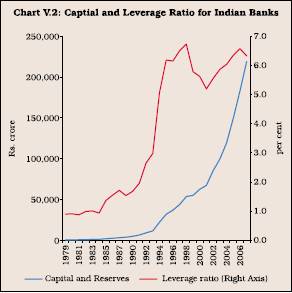

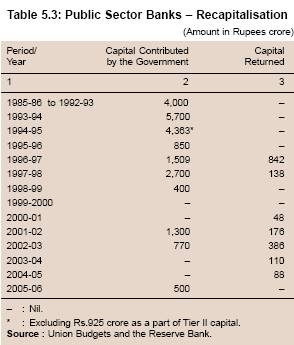

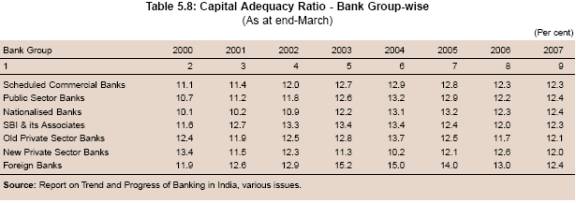

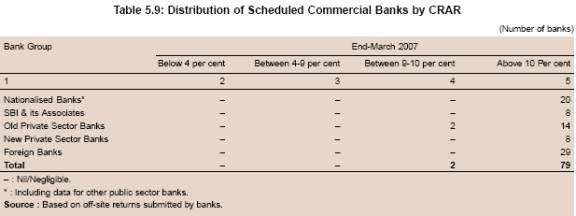

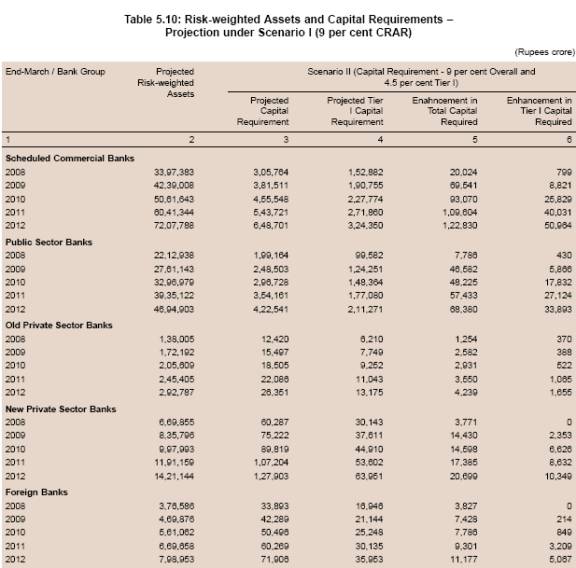

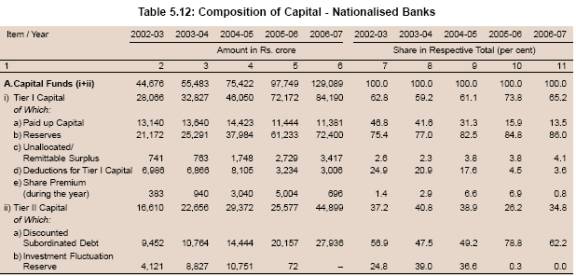

CEPR Discussion Paper Series No. 6596.