IST,

IST,

Basel III Liquidity Risk Framework - Implementation and Way Forward

Shri N.S. Vishwanathan, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India

Delivered on Jan 01, 2016

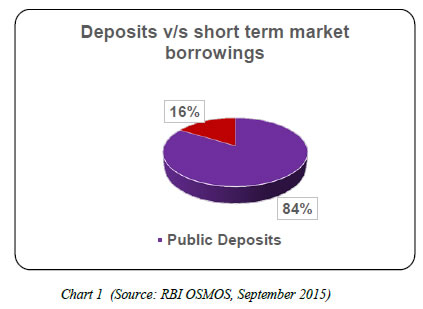

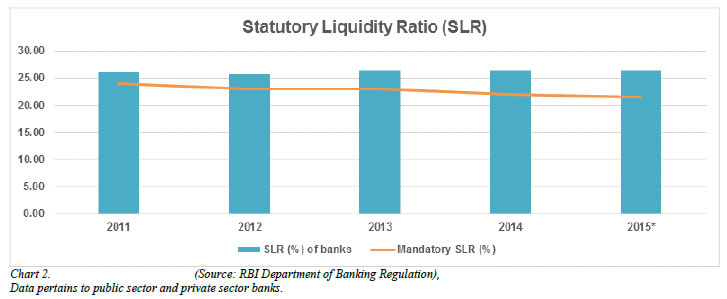

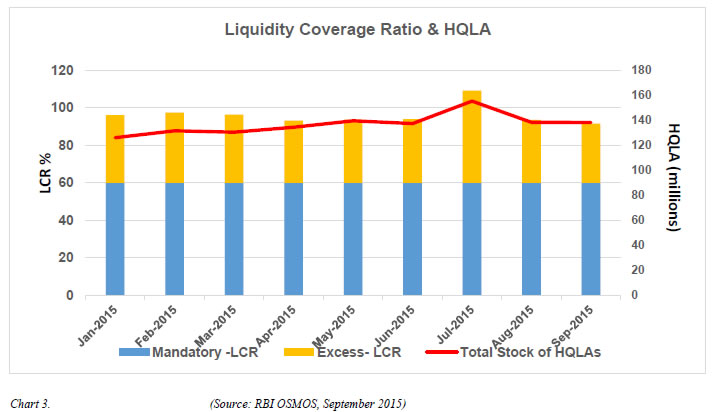

Good morning. It is my pleasure to be with you in Hyderabad in this conference on the Basel III Liquidity Risk Framework in India. As the chair of a group discussion on Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) at the Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India (FIMMDA) Annual Conference in Prague a couple of months ago, I had hinted that the Reserve Bank would initiate a process of discussions with bankers on the whole gamut of issues concerning Basel III liquidity framework. I am happy to say that the plan for this unique endeavour has fructified, as a result of a series of discussions with you all. Why this seminar It needs no mention that liquidity framework is an important part of the post-crisis reforms taken up by the Basel Committee and I believe it is a very significant one. Prior to these guidelines, the regulations relating to liquidity were limited which in a way paved the way for the banks to extensively use wholesale short term funding to fund long term assets. Unlike the West, our banking system did not depend on wholesale short term funds. Our system was more dependent on public deposits and did not face the kind of liquidity issues that the banking system in the West did. There were several reasons for this. First, our economy had a high domestic, and more particularly household, savings ratio. Second, there were not many avenues for the household to park their savings and hence banks became the primary repository. Third, the banking system was largely in the public sector which gave the public a sense of safety of their funds. Fourth, we always had the notion of an acceptable credit-deposit ratio that provided an informal foil to any attempt to build an over-extended credit portfolio. Fifth, we had the Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR), which statutorily required that a part of the demand and time liabilities are held in liquid assets. Sixth, as early as 1999, we had issued guidelines on Asset Liability management (ALM) by banks. These guidelines were further enhanced in 2007. The bucketing of assets and liabilities under these guidelines and the Structural Liquidity Statement prepared by the banks have provided useful insights to the supervisors as regards the liquidity health of banks. Last but not the least, the RBI as the supervisor of the banking system did not take kindly to excessive dependence on market borrowings. But many things have changed or are changing. Not the least the fact that the Indian banks, from being mainly lenders of working capital, have over time become major providers of long term capital for large industrial and infrastructure projects. This has implications for ALM in particular but rubs on the overall liquidity management as well. Statutory pre-emption has declined considerably. The balance sheet structure of banks has undergone a change. Household savings as a percentage of GDP has declined and there could be greater demand for bank funds once the economy takes off. Obviously, therefore, over time, the concept of liquidity management has undergone a change even in India. In this background, the liquidity framework of Basel III assumes added significance for banks in India and many banks have been approaching us to comprehend the finer points of the liquidity regulations, as also with requests to make changes therein. This conference was envisaged to bring banks together on a single platform, with a view to exchanging ideas in a free and frank manner, thereby getting clarity on the underpinnings of liquidity risk framework. During the course of two days, we hope to hear from you constructive suggestions on how to improve the Liquidity Risk framework in the Indian context, give you a sense of the expectations of supervisors and regulators, and above all, if possible, work out some clear deliverables. We surely want to listen more and say less. How much we are able to do is a function of how reasonable what you say is. Liquidity Risk – some issues Prior to the crisis, asset markets were buoyant and funding was readily available at low cost. However, rapid reversal in market conditions led to extended periods of illiquidity. The banking system came under severe stress, which necessitated central banks to intervene by supporting markets as also individual institutions. In fact I have always held the view that liquidity risk deserved more attention than it got, because it is only a matter of time before liquidity risk turns into a solvency risk. The reasons are not very far to seek: Banking is a highly leveraged business in which public repose trust in the belief that they will get their funds back as and when they want. This belief comes from the fact that it is a business that is licenced by a public authority that regulates and supervises the banks on certain established principles. The crisis highlighted inter alia the importance of regulating and supervising the liquidity risk management of banks thereby ensuring their safety and soundness under stressed conditions. Any event that undermines this faith cuts at the very root of the relationship between a bank and its customer. Depositors will withdraw money, borrowers will migrate to another bank which can meet their needs. Thus poor liquidity risk management deals a body blow to a bank’s ability to undertake its basic business. In very simple terms, therefore, everyone transacts with a bank in the belief that it has the funds and funding sources to meet its obligations whether to a depositor or borrower. It may not be just meeting its liabilities but the credit needs of its borrowers as well. The depositor in a complex world could mean any person to whom the bank owes funds and the word borrower means any person to whom the bank has provided or committed to provide funds. Liquidity risk arises when a bank is not able to meet its obligations without incurring a disproportionate cost and finally being unable to meet the obligations at all. The 2007 crisis revealed that well capitalised banks experienced difficulties which could be traced to lack of prudent liquidity management. It underscored the importance of liquidity to the proper functioning of financial markets and the banking sector. Till then one believed that the wholesale market had unlimited capacity to fund the liquidity requirements of banks and thus led to funding risky or illiquid asset portfolios with potentially volatile short term liabilities. It showed through some cases how single institutions could cause deleterious systemic implications. Basel Committee responded by publishing Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision, followed by two minimum standards for funding liquidity, viz., Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio. In 2012, the Indian framework incorporated Principles for Sound Liquidity risk management. These seventeen principles were issued so that the liquidity risk framework of our banks could incorporate the global best practices. In June 2014, RBI had issued the guidelines on Basel III framework on liquidity Standards – LCR, Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools and LCR Disclosure Standards, and in May 2015, draft guidelines on Net Stable Funding Ratio were issued. Meanwhile, in November 2014, guidelines on Monitoring tools for Intraday Liquidity Management were issued. LCR intends to promote the short-term resilience of banks to potential liquidity disruptions. It requires that the banks have adequate high quality liquid assets (HQLA) to withstand a 30-day liquidity shock. These HQLAs should be available with the bank to cover net cash outflows that are expected to occur in a severe stress scenario. NSFR on the other hand supplements the LCR and has a time horizon of one year. It has been developed to provide a sustainable maturity structure of assets and liabilities. I will now delve in some detail into these standards. I want to touch upon some of the regulations, our views on them and provide the rationale for the rules as accepted by us. The Indian framework for LCR requirements was issued on June 9, 2014 through the publication of final Guidelines on the LCR, Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools and LCR Disclosure Standards, where implementation of the LCR has been phased in from January 1, 2015 with a minimum mandatory requirement at 60 per cent, which will gradually increase to 100 per cent by January 1, 2019. The NSFR draft guidelines were issued in May 2015 and India is committed to the scheduled implementation of NSFR from January 1, 2018. Whenever there is a discussion on LCR the reference to SLR requirements running parallel is inevitable. As I have already mentioned, SLR has been the mainstay for Liquidity Risk Management for Indian banks. SLR is similar to LCR in composition except that LCR is a more sophisticated tool to ensure liquidity under stressed conditions that takes account of the liquidity profile of both assets and liabilities. LCR does not impound the funds of banks for lending beyond what is assumed to be necessary to maintain their liquidity on an on-going basis. Moreover, as LCR permits other securities apart from G-secs, it is expected to give a fillip to markets other than G-Sec market, especially the corporate bond market. Furthermore, LCR is an internationally accepted standard and its implementation brings convergence with global standards. Non-compliance with Basel rules can have major ramifications for the banks of a jurisdiction. Of course, every jurisdiction factors in the domestic conditions to the extent permissible. With the advent of peer review under BCBS’ Regulatory Consistency Assessment Program (RCAP), the guidelines put in place by each jurisdiction are subject to international validation for the quality of implementation and interpretation of the Basel rules. India has a history of implementing the Basel guidelines in letter and spirit. In fact we underwent an assessment under RCAP only recently. It will be of interest to you all to note that as per the review, while we are fully compliant on the capital regulations, we were found to be only Largely Compliant on LCR and Compliant on the LCR disclosure requirements. The lower rating for our compliance with the liquidity guidelines stems from the view of the review team that State Development Loan (SDL), or the state government securities as they are popularly called, cannot be considered as sovereign debt securities in the context of the Basel standard and hence, cannot be accorded treatment of Level 1 HQLA. We have nevertheless argued our case and for now they stay as HQLA1. I am mentioning this to only request you to moderate your suggestions for changes that do not violate the basic Basel rules. With the advent of LCR under Basel III, there is a growing apprehension that maintaining such high liquidity, given the SLR requirements in India, may be difficult for banks. In fact, after the issuance of the guidelines, banks have been asking for doing away with SLR. At the time of introducing LCR, it was considered prudent to continue with SLR. Going forward, the LCR will increase to 100% of the required level by 2019. It is being argued that Indian banks are required to maintain more liquidity than what is envisaged in the Basel III LCR regime that would adversely impact their competitiveness and efficiency. Presently, apart from maintaining LCR at 60%, the banks have to maintain SLR of 21.5% of the NDTL. Incidentally, I would like to mention here that Indian banks have traditionally preferred to maintain SLR, over and above the statutory minimum. As you all know, we have softened the impact of both SLR and LCR having to be maintained by introducing the concept of FALLCR2. The 2 per cent MSF3 also reduces the impact. One good thing is that the FALLCR concept has passed the RCAP review and therefore this can be a possible tool to reduce the impact of SLR and LCR running parallel as the minimum required LCR moves up. With the current levels of SLR assets held by banks, the joint LCR and SLR requirements is not becoming a binding constraint. In fact based on an internal study, we find that on aggregate basis the banks are in a position to maintain LCR of around 80 per cent (as against the current requirement of 60 per cent) with the present carve-out of 7 per cent of SLR which is permitted to be reckoned as Level 1 HQLA (Chart 3) We have already announced the reduction of SLR by 1 percent over four quarters. I must point out here that any further request for reduction in SLR has to be mixed with caution as it could be a self-defeating one in the short run at least. I am referring to the potential hardening of yields of G-sec and the depreciation in the value of the current portfolio if the demand for future issuances of Government debt falls. Therefore, we need to calibrate this in a non-disruptive manner, which is what we have been ensuring and will continue to ensure. Let me now turn to a few issues in NSFR. We had issued the draft guidelines on Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) on May 28, 2015 for public consultation. India is amongst the few jurisdictions that have come out with these guidelines. The reason for this is simple – while we wanted to give our banks ample time for the consultation process, the banks also get lead time to get their systems and processes in place. In this area, I would be happy to take views and opinions from you. These would facilitate us to help finalising the guidelines. In NSFR, like in LCR, though we would follow the Basel framework, we would prefer to dovetail the same for Indian conditions. NSFR would ensure that banks have a stable funding profile vis-à-vis their assets and off-balance sheet activities. Banks have incentives to expand their balance sheet rapidly by depending on cheap short-term wholesale funding. This may weaken the ability of banks to respond to liquidity shocks. NSFR seeks to discourage banks to rely on short-term wholesale funding, thereby promoting funding stability and encourages better assessment of funding risk across all on- and off-balance sheet items. The NSFR is the ratio of available stable funding to required stable funding; it is required to be equal to at least 100% on an on-going basis. “Available stable funding” is that portion of capital and liabilities which is expected to be reliably available up to one year. "Required stable funding" is the stable assets held by a bank as also, its off-balance sheet (OBS) exposures. Though the guidelines are at draft stage, I would like to flag a few issues that you may like to discuss. The NSFR standard, unlike LCR, is not being phased-in. Consequently, from January 1, 2018, banks would have to maintain NSFR of at least 100 per cent. Our understanding is that Indian banks would be comfortable on NSFR front. As of June 2015, based on data from a sample of Indian banks, the NSFR was observed to be 121 per cent, much higher than the requirement of 100 per cent. Some of the issues under NSFR relate to treatment of secured funding transactions,, specifically regarding the RSF factor for the amount receivable by a bank under a plain vanilla reverse repo transaction, treatment for the collateral received if held unencumbered, treatment of collateral received in secured lending transactions if the collateral has been re-hypothecated, etc. These require better understanding and wider debate. One of the peculiarities of our market is Collateralised Borrowing and Lending Obligation (CBLO). It is akin to tri-partite repo. However, presently it is treated like an unencumbered loan to financial institutions with residual maturities of less than six months, and hence, carries a RSF factor of 10 per cent. There is another view that CBLO is more like Level 1 HQLA and must be accorded a RSF of 5 per cent. CBLO is a product that is unique to India. A CBLO is created against the eligible securities that become encumbered. A bank trades this CBLO with a counterparty, which lends money and buys CBLO. What the counterparty is buying is an instrument that is backed by encumbered Government securities. I would be glad to hear your views on this debate. Treatment of derivatives under NSFR is being actively debated internationally. Further, margin requirement for OTC derivatives is another area that is being widely discussed. The NSFR currently treats initial margin and contribution to CCPs’ default funds (DF) equivalently, i.e., same RSF factors. This may be because in economic terms, these two types of collateralisation are close substitutes, and may require collateral for counterparty credit risk events. However, there is a view that the objectives of these funds are different and hence the treatment should also be different, and that seeking stable funding for CCPs’ default fund contributions may dis-incentivise the role of CCPs, which is contrary to the current global thinking of increasing the role of CCPs. I mentioned that I will give the rationale for some of the rules we have adopted. I will confine this to some of the rules related to LCR because we have issued the final guidelines;

Before I conclude, let me summarise. Liquidity risk did not get the due attention in the past and therefore the post liquidity risk related reforms are very timely and appropriate. I argued that in India due to several reasons, banks have been used to a more conservative approach to liquidity risk management but things are changing. Reserve Bank is therefore committed to proper implementation of the Basel rules in this regard and would at the same time ensure that the SLR-LCR combination is not overly burdensome for the banks. Nevertheless any request to reduce SLR has to be moderated to avoid disruption in the G-sec market. I explained the reasons for some of the rules and flagged some issues in NSFR. I now look forward to a meaningful discussion on the issues at hand so that we have clear actionable outcomes that would help us move forward to put in place a robust liquidity management framework in India that meets the BCBS standards and you as banks are able to implement without much difficulty. Thanks for your attention. 1This is an expanded version of the opening address delivered by Shri N S Vishwanathan, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India, at the “Basel III Liquidity Risk Framework – Implementation and Way Forward” at Hyderabad on November 27, 2015. The contribution of Shri Puneet Pancholy, DGM, DBR is gratefully acknowledged. 2FALLCR or the Facility to Avail Liquidity for Liquidity Coverage Ratio shall mean facility whereby banks will be permitted to reckon government securities held by them up to a certain per cent of their NDTL (presently 5%) within the mandatory SLR requirement as level 1 HQLA for the purpose of computing their Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). 3MSF or the Marginal standing facility shall mean the facility under which the eligible entities can avail liquidity support from the Reserve Bank against SLR securities, up to a certain per cent of their respective NDTL (presently 2%) outstanding at the last Friday of the second preceding fortnight. |

Page Last Updated on: