IST,

IST,

Gross Financial Flows, Global Imbalances, and Crises

Prof. Maurice Obstfeld, Guest Speaker

Delivered on Dec 13, 2011

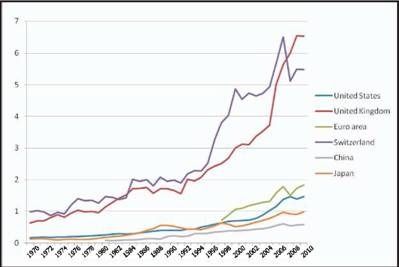

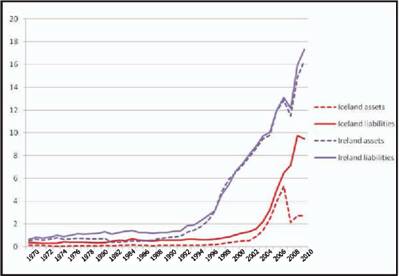

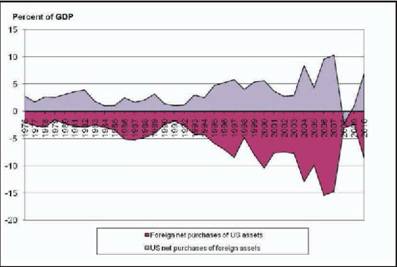

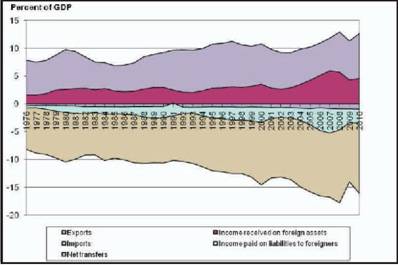

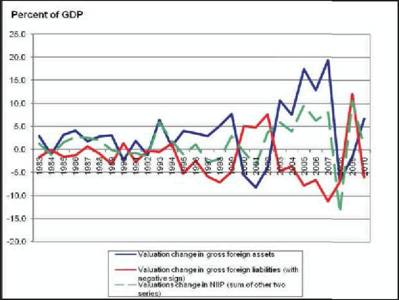

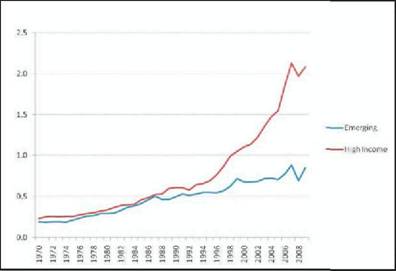

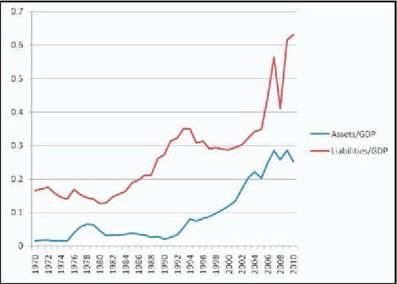

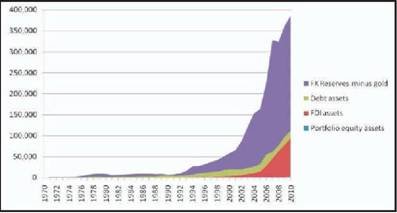

1. Introduction I am much honored to stand here at the Reserve Bank of India as the twelfth L. K. Jha Memorial Lecturer. Shri Lakshmi Kant Jha was a diplomat, administrator, counselor to government, and central bank governor, among other notable achievements. His writing spanned the most important economic and social issues of the day, as debated both within India and throughout the broader world. My eleven predecessors at this podium form an exceptional group of economic thinkers: leaders in academia, in the policy world, and in most cases, in both. It will be very hard for me to live up to the high standard of insight and relevance that they have set. My task of engaging your interest is made easier, however, by the fascinating yet frightening tableau that the global economy continues to present after four years of lost income, wealth, and jobs. We would all be better off if the supply of interesting current topics were less copious! Alas, global boom and bust have alternated historically, and failure to draw the right lessons from previous crises seems inevitably to contribute to the next. We have been here before. One such time was in the early 1980s, when L. K. Jha, as a member of the Brandt Commission, contributed to that group's somewhat lesser known second report of 1983, entitled Common Crisis and subtitled North-South: Cooperation for World Recovery. The document is remarkable in identifying numerous economic and financial problems that are still relevant today. For example, the authors wonder if the interbank market could transmit liquidity or solvency problems contagiously; they worry about the oversight of bank lending to indebted sovereigns; and, while concerned about moral hazard, they bemoan both the inadequate resources of the International Monetary Fund and the absence of formal lender-of-last resort arrangements covering the foreign operation of national banks. Sound familiar? In an attempt to distil some useful lessons from our current prolonged crisis, I will focus tonight on one particular topic area: the progress of financial globalization. International economic integration puts a country's fortunes partly into the hands of others. When integration takes the form of financial interdependence, the potential domestic impact of external events is magnified many times over. The global economic crisis of 2007-09 and the European sovereign debt crisis that followed have unleashed market forces that even policymakers in the mature economies were ill prepared to counteract. Despite a quarter century of explosive development in international financial markets, problems that worried the Brandt commissioners remained largely unresolved. The existing informational and institutional infrastructure for global policymaking still remains woefully inadequate to the challenge of financial globalization. Even before the global financial crisis, net financial flows between countries, in the form of current account deficits and surpluses, were a focus of policy concern and disagreement. While the general scale and persistence of current account imbalances certainly has increased over the past two decades, even more striking - and potentially more threatening to financial and economic stability - is the rapid expansion of gross international asset and liability positions. Net international asset positions certainly remain relevant for several purposes, as I will maintain in this lecture, but it is the gross positions that better reflect the impact on national balance sheets of various economic shocks, including counterparty failure. After all, a Portuguese external debtor cannot automatically mobilize the assets of a separate Portuguese external creditor to pay off his or her debts. This fact makes it even more unsettling that Portugal's net external liability amounts to well over a year's GDP. The sheer increase in the volume of gross international positions could in theory represent an improving global allocation of income risks, but recent experience shows that these positions also can lead to the transmission of economic shocks between countries, with strong amplification of their effects. This evening I will document the proliferation of gross international asset and liability positions and discuss some of the consequences for individual countries' external adjustment processes and for global financial stability. In light of the rapid growth of gross global financial flows and the risks associated with them, one might wonder about the continuing relevance of the net financial flow measured by the current account balance. I argue that global current account imbalances remain an essential target for policy scrutiny, for financial as well as macroeconomic reasons. Nonetheless, it is critically important for policymakers to monitor as well the rapidly evolving structure of global gross assets and liabilities. In passing, I will pay special attention to India's external balance sheet and contrast it with those typical of some of the major industrial countries. 2. The Growth of Pure Asset-for-Asset International Trade In theory, countries exchange assets with different risk profiles to smooth consumption fluctuations across future random states of nature. This intratemporal trade, an exchange of consumption across different states of nature that occur on the same date, may be contrasted with intertemporal trade, in which consumption on one date is traded for an asset entitling the buyer to consumption on a future date. Cross-border purchases of assets with other assets are intratemporal trades, purchases of goods or services with assets are intertemporal trades. A country's intertemporal budget constraint limits the present value of its (state-contingent) expenditure (on consumption and investment) to the present value of its (state-contingent) output plus the market value of its net financial claims on the outside world (the net international investment position, or NOP). Thus, a country's ultimate consumption possibilities depend not only on the NOP, but on the prices a country faces in world markets and its (stochastic) output and investment levels. Ideally, if a country has maximally hedged its idiosyncratic risk in world asset markets, its NIIP will respond to shocks (including shocks to current and future world prices) in ways that cushion domestic consumption possibilities. Furthermore, if markets are complete in the sense of Arrow and Debreu, asset trades between individuals will indeed represent Pareto improvements in resource allocation, so that it makes sense to speak of countries as if they consisted of representative individuals. But this type of world - a world without crises - is not the world we inhabit In the real world, financial trades that one agent makes, viewing them as personally advantageous, can work to the detriment of others. The implication is that the sheer volume of financial trade can be positively correlated with financial instability risks. It is in the realm of intratemporal asset trade that international trading volume has expanded most in recent years. Explosive growth has occurred for several economies, especially smaller economies that are also financial hubs. Figure 1 illustrates this evolution for a sample of countries, showing updates to 2010 of the Lane and Milesi-Ferretti data.1 Despite some retrenchment as a result of the global crisis, gross assets continue to expand. For smaller countries such as Ireland, the numbers can be even more impressive, as Figure 2 (which also tracks Iceland and shows gross assets and liabilities as ratios to GDP separately) indicates. While the gross asset and liability numbers for the United States are less exorbitant than those for smaller financially open economies, a look at the changing role of gross asset flows in the U.S. balance of payments is suggestive of the growing importance of international asset trade relative to trade in goods and services. The two panels of figure 3 show the gross flows underlying the U.S. current account balance from alternative transactional perspectives. The upper panel shows net U.S. residents' purchases of foreign assets (with a positive sign, as per the IMF's sixth balance of payments manual). It also shows foreign residents' net purchases of U.S. assets (with a negative sign). The algebraic sum of the two series in panel (a) the net increase in U.S. foreign assets less the net increase in U.S. foreign liabilities, would equal the current account balance absent errors and omissions in balance of payments data. (The U.S. current account deficit peaked at about 6 percent of GDP in 2006.) The lower panel of figure 3 shows U.S. exports and imports, together with investment income flows and net transfers. The algebraic sum of the five series shown equals the current account balance. In the mid-1970s, gross financial flows were considerably smaller than trade flows, but the former have grown over time and on average now are of comparable magnitude to trade flows. Of course, international flows of investment income have grown over time as well as gross foreign asset and liability positions have grown. Neither panel of figure 3 captures the total change in the U.S. NIIP. The total change in the NIIP depends on the flows of net international lending, of course, but also on net capital gains on gross foreign assets and liabilities, as emphasized by a number of economists.2 The overall change in U.S. gross foreign assets over a period equals net purchases by U.S. residents plus any capital gains on the prior stock of gross foreign assets. The overall change in U.S. net foreign liabilities equals net sales of assets to foreign residents plus any capital gains foreigners enjoy on their gross holdings of assets located in the U.S. The overall change in the NIIP thus incorporates these capital gains, since it equals the overall change in U.S. external assets less liabilities. Figure 4 shows the non-flow changes on U.S. foreign assets and liabilities, with increases in liabilities represented as negative numbers. The amplitude of these changes has grown in tandem with volumes of gross flows, reaching levels that represent very large fractions of U.S. GDP. Figure 3 and 4 together show that in 2008, gross capital flows in and out of the U.S. collapsed - a two-way sudden stop - in concert with a huge valuation loss on the U.S. NIIP. Simultaneously, the country's external assets fell and its liabilities rose in value. The 2008 NIIP valuation loss equaled 13.7 percent of GDP, mostly reversed in 2009 with a valuation gain of 10.6 percent of GDP.3 These changes far overshadow the effect on the NIIP of the U.S. current account deficit, which fell to 4.7 percent of GDP in 2008 and to 2.7 percent in 2009. For smaller financially open economies, especially those like the United Kingdom with independent currencies, the valuation effects can be far larger. 3. Balance Sheet Vulnerabilities So far, emerging-market economies have not yet amassed stocks of gross external assets and liabilities comparable to those of the richer countries. Figure 5 provides a head-to-head comparison of these two country groups' average asset external exposures (calculated with relative GDP weights). Today, emerging markets are in quantitative terms roughly where the industrial countries were at the time of the Asian crisis in the late 1990s. Although emerging-market external positions have risen quite a bit since then, the gap between the two groups has also widened markedly. Once a certain level of financial integration has been reached, gross position buildups such as those evident for the industrial countries in figure 5 are likely to imply a proliferation of counterparty obligations that may be defaulted and thus carry the risk of contagious financial instability through chains of leverage - just the sort of phenomenon that led to widespread government financial interventions in the rich economies in 2008-09. In contrast, a country's portfolio equity or FDI liabilities can fall quickly through the price mechanism without creating defaults. But there is only so much domestic capital for foreigners to hold, so beyond a point, increasing gross asset positions imply increasing associated default possibilities, with adverse implications for financial stability. Emerging markets economies such as India remain far from the external leverage levels of the industrial world, and as Prasad (2011) documents, the recent trend has been for equity liabilities (portfolio equity and FDI) to grow as fractions of overall gross external liabilities.4 This development cushions shocks in two ways: there is no automatic increase in the real value of foreign liabilities when the home currency appreciates, and there is no question of debt non-repayment or counterparty risk, since payments on equity, even though state contingent, are not contractually specified. Thus, when the economy turns down, the value of externally-held equity claims automatically declines. The prevalence of equity liabilities is quite marked in India, where government policies and financial market reforms after 1991 heavily favored inward equity investments, but discouraged borrowing via bank deposits or bond issuance.5 Figure 6 shows the overall gross foreign assets and liabilities of India, which grow at a much accelerated rate after the liberalization measures initiated in 1991, but in 2010 still falls short of the levels that advanced economies display. Figure 7 gives a breakdown of assets and liabilities, again based on the Lane and Milesi-Ferretti data, into equity and nonequity components. External liabilities are heavily weighted toward equity, as noted above, whereas external assets are heavily weighted toward debt-like assets (in no small measure consisting of non-gold official reserves). In the crisis year 2008 the values of externally-held Indian equities collapse, improving the NIIP sharply, but they recover in 2009-2010. These asset-price developments provide some natural insurance against economic shocks rather than provoking an external debt crisis. Even though gross foreign assets and liabilities remain rather moderate relative to India's GDP, the high equity component in liabilities is a good part of the reason that the correlation of the current account with the change in the NIIP is 0.93 over the first half of the 1971-2010 sample but only 0.24 over the second half. 4. Does the Current Account Matter Any More? One could make two arguments that the current account has become irrelevant in today's world. Paradoxically, however, the two arguments rest on directly opposite visions of the way the world works. I will argue against both of them, although one is much closer to the mark than the other. The first argument takes the high volume of asset-swapping as proof that countries have extensively diversified their idiosyncratic risks in sophisticated, well-functioning markets for contingent securities. In this world of virtually complete Arrow-Debreu asset markets, countries pool their risks to the maximum feasible extent. In the extreme case of a pure endowment economy, idiosyncratic income movements are offset completely by net insurance payments from abroad, so the current account balance is always nil. With investment, the current account's role is to allow investors to maintain globally diversified portfolios of equity claims through purchases of newly issued shares in the profits of capital. Under complete markets global imbalances are generally small.6 But the sheer volume of asset swapping, particularly among the advanced industrial economies, is far greater than what simple risk-sharing models based on equity trade would imply. Moreover, the complete-markets account of international asset trade is not supported either by statistical or anecdotal evidence, chief among the latter category being the long history of global financial crises. Most of the advanced-country assets shown in figure 5 are debt-like assets such as bank deposits and government or corporate bonds, all of which potentially carry default or counterparty risk, and thus have potentially strong implications for global financial stability. This leads to the second argument that the current account is irrelevant (or at least nearly so). This argument is based on the view that imperfections in risk sharing can reinforce each other so as to magnify systematic risks, which themselves are endogenous to the financial system. The argument maintains that the stability impact of current account balances per se is small compared to that of the gross asset flows that ultimately finance international financial transactions. Borio and Disyatat (2011) give an insightful summary of this second perspective.7 It is certainly correct that gross asset foreign and liability positions offer the best picture of potential stability risks, and that hazardous gross positions can build up even in the absence of any net international capital flows. Acharya and Schnabl (2010) offer a superb detailed example of the negative forces generating large gross positions, based on the proliferation of bank-sponsored asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits that helped kick off the global crisis in August 2007.8 Banks set up these conduits to hold AAA-rated asset-backed securities backed by mortgages, corporate loans, credit card receivables, and other long-term debts. They financed these holdings by selling short-term ABCP, predominantly to U.S. money-market funds. As Acharya and Schnabl document, in many countries these conduits were effectively guaranteed by the sponsoring banks, yet the conditional nature of the guarantee allowed the banks to reduce or avoid altogether the regulatory capital held against the conduit's assets. In some cases - the case of Germany's Landesbanken is notorious - implicit or explicit government guarantees reassured the ABCP holders that their holdings were fully safe, despite the conditional nature of the sponsors' guarantees. In contrast to theories viewing international financial flows in the 2000s as being determined by emerging markets' thirst for safe assets, banks outside the U.S. were issuing plenty of "safe" assets while investing the proceeds in less liquid and less safe assets located primarily in the U.S. but also in the United Kingdom, Spain, and even some current account surplus countries such as the Netherlands. Banks in current account surplus and deficit countries alike sponsored ABCP conduits. When a Landesbank-sponsored conduit finances a purchase of U.S. assets by issuing ABCP to a U.S. money market fund, U.S. gross foreign assets and liabilities, and German gross foreign assets and liabilities, both rise by the amount of the transaction. No net financial flow takes place. The trade is privately profitable, but the profits come from socially costly sources: higher systemic financial instability due to the avoidance of capital requirements, and the resulting enhanced probability of government bailout. In short, the trade is driven, not by initial economic inefficiency, but by regulatory arbitrage and moral hazard. These social risks were realized in August 2007 when the AAA-rated assets held by the conduits became toxic and the conduits found themselves suddenly unable to roll over their short-term credits.9 Such financing patterns undeniably determined the impact and propagation of the global financial crisis. Does it follow, however, that because banks in surplus and deficit countries alike got into trouble, the prior pattern of global imbalances was unrelated to the crisis? That strikes me as similar to arguing that because German banks got into trouble and Germany had no housing boom, house-price bubbles were likewise unrelated in the crisis. This is not to claim that global imbalances (an endogenous phenomenon) in some sense caused the global crisis - no more than that the imbalances within the euro zone (see figure 8) are the cause of the current sovereign debt crisis. Nor can one maintain that the impact and spread of the crisis would have been anywhere near as severe had widespread gaps in financial supervision and regulation not encouraged the proliferation of gross positions such as the ones Acharya and Schnabl describe. As Borio and Disyatat argue, intuition based on a two-country or two-region paradigm can be very misleading in assessing the risks posed by the multilateral pattern of gross financial flows in a many-country world; and position data based on residence rather than nationality may mask the ultimate natures and repositories of the risks. The net inflow of capital from emerging to advanced economies is quantitatively far less than the amount of domestic credit those economies generated in the run up to the global crisis.10 Nonetheless, I would maintain (as Kenneth Rogoff and I did in our San Francisco Fed paper in 2010) that large and persistent current account imbalances can be an indicator of trouble ahead, as they were in the 2000s, and therefore deserve close monitoring by policymakers.11 Low interest rates due to global saving and investment patterns, along with accommodative monetary policy responses and other government policies, promoted credit and housing booms that themselves led to a further widening of the global imbalances. Financial competition, innovation, and arbitrage, proliferating within a lax regulatory environment, built a financially fragile superstructure of gross liabilities and claims on the back of those unsustainable booms. The big U.S. external deficit was a symptom of underlying destabilizing forces, and indeed enabled those forces to play out over an extended period. What is the general relationship between current account deficits and credit booms? There is now considerable evidence linking booms in credit availability to a heightened probability of future financial crisis.12 But as Hume and Sentance point out, several large emerging markets have experienced credit booms without net capital inflows. Japan's epic boom-bust cycle starting in the late 1980s occurred despite a current account surplus (although the surplus declined during the bubble period). Despite such counterexamples, there is some evidence (stronger for developing countries) that net inflows of private capital may help generate credit booms and, in the presence of potentially fragile financial systems, raise the probability of a crash. For example, Ostry et al. (2011, p. 21) study panel data for an emerging-market sample over 1995-2008, and they conclude, "one-half of credit booms are associated with a capital inflow surge, and of those that ended in a crisis, about 60 percent are associated with an inflow surge."13 Studies such as this do not directly address the link between credit booms and the current account because the net inflow of private capital and the current account deficit need not coincide: even a country with a current account surplus may experience a net inflow of private capital if it is accumulating a sufficient volume of foreign exchange reserves. Jorda, Schularick, and Taylor (2011, p. 372) examine the question more directly, utilizing fourteen decades of data for a sample of advanced countries, and conclude that "The current account deteriorates in the run-up to normal crises, but the evidence is inconclusive in global crises, possibly because both surplus and deficit countries get embroiled in the crisis." Reinhart and Reinhart (2009) find evidence that current account deficits help predict crises in developing countries.14 The general question merits further research. In the meantime, I believe that large and persistent current account deficits, while sometimes benign and sustainable, warrant careful scrutiny with no presumption of innocence. External deficits may not be the true source of a problem - nor is the problem necessarily addressed most effectively by seeking directly to reduce the external deficit - but it is nonetheless prudent to be suspicious. Looking at the current predicament of the euro zone, it is easy to argue (unfortunately, with hindsight), that its after 1999 were symptomatic of unsustainable trends - Greece's government deficit, housing and construction booms in Spain and Ireland, and excessive private borrowing in Portugal, with finance provided in large measure by European banks (including banks in surplus countries) that now find themselves in trouble (again, see figure 8). Sometimes we must simply ask whether a country is in a position to fully service its net external debts, even when they are reckoned on a consolidated national basis. This is a necessary condition, if not a sufficient one, for crisis-free foreign borrowing. If the answer is negative, a further question arises: Who is likely to be dragged into the eventual crisis as a result of their gross asset and liability positions vis-a-vis the country in question (or as result of their secondary exposures to those who hold the primary exposures, and so on). In assessing the sustainability of current account deficits, we cannot take too much comfort from the seeming decoupling between cumulated current account imbalances and the NIIP, which was illustrated for the U.S. in figure 5. For one thing, the current account is the more predictable component of the NIIP change. Only for the U.S. is there any indication that net exports might help predict subsequent NIIP valuation changes.15 It would be rash in general to count on such windfalls as the deus ex machina that will maintain solvency with respect to foreign creditors. Indeed, it is hard to think of a plausible model in which the direction of the current account does not predict the direction of the NIIP, at least over a medium-term horizon. There should be no expectation of borrowing indefinitely at a negative rate of interest. It is true that the U.S. borrowed abroad consistently during 2002-2007 without a consistent rise in its NIIP, as valuation gains on the NIIP offset the negative effect of growing current account deficits (figure 4). This pattern, which may have ended with the collapse of 2008, is reminiscent of self-reinforcing dynamics during credit boom episodes. In credit booms, asset values rise, improving balance sheets and facilitating the further expansion of credit. As a result, subsequent collapses are all the more traumatic. (The carry trade involves similar dynamics.) A capital inflow episode likewise may strengthen financial sector assets and even the NIIP in the receiving country in a way that pushes domestic borrowing beyond the point of true sustainability. This often sets the stage for a disorderly collapse later on. In diagnosing such situations, it is essential to keep the underlying credit flows in clear view. A purely macroeconomic perspective also argues for the continuing importance of the current account as a component of aggregate demand. The emergence of a current account surplus in one region may depress aggregate demand globally, affecting global financial markets and eliciting policy responses in trade partners. Large global imbalances may also encourage protectionism.16 5. Conclusion For several reasons, the current account still matters. Recent experience shows, however, that gross international asset and liability positions furnish the key conduit through which financial meltdown is transmitted and amplified. A given current account imbalance can be financed in many different ways, by a multiplicity of different partners in asset trade, including partners whose own current accounts are in balance. But national divergences between saving and investment not only remain key macro variables, they may well reflect financial developments with direct systemic implications. The evolving world of financial globalization can be a dangerous place. Unfortunately, policymakers still lack an adequate institutional infrastructure for assembling consolidated global information on financial activity, for regulating against macro risks, for providing liquidity support, and for resolving insolvent global financial institutions and governments. If policymakers are not to remain in over their heads, institutions - at the global level, and not just the euro zone level - will require wide-ranging extension, based on greater cooperation, including fiscal cooperation, on the part of the international community. It bears repeating that a key aim of such institution building must be to improve the informational basis on which cooperative international policy decisions are made. Figure 1: Average of gross foreign assets and liabilities as a ratio to GDP:

Figure 2: Gross foreign assets and liabilities as a ratio to GDP: Iceland and Ireland

Figure 3: United States gross balance of payments flows as a percent of GDP (a) Gross financial flows

(b) Current account component flows

Figure 4: Non-flow changes of U.S. foreign assets, liabilities, and NJLLF,

Figure 5: Average of gross foreign assets and liabilities as a ratio to

Figure 6: Gross foreign assets and liabilities as a ratio to GDP: India

Figure 7: Components of India's gross foreign assets and liabilities (a) Assets (millions of USD)

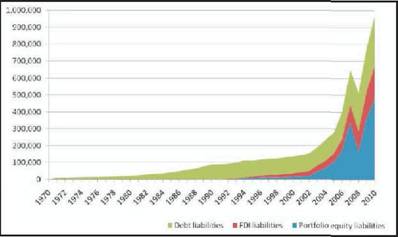

Figure 7: Components of India's gross foreign assets and liabilities (b) Liabilities (millions of USD)

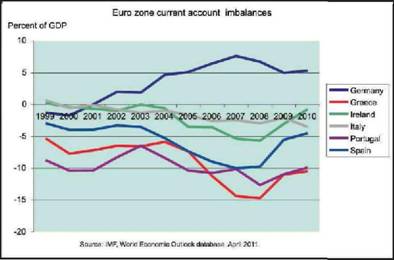

Figure 8: Eurozone current account imbalances

1 I am grateful to Philip Lane and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti for providing these data. The original reference is Philip R. Lane and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, "The external wealth of nations, mark II: Revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970-2004," Journal of International Economics 73 (2006), 223-250. 2 For some references to the literature see my paper "External adjustment," Review of World Economics, 140 (2004), 541-568. 3 In figure 5, foreign direct investment (FDI) is reckoned at market value. While I refer to these non-flow changes as "valuation" changes one must be cautious, because to a very substantial degree they may also reflect periodic revisions in the gross asset and liability data due to enhanced coverage. See Stephanie E. Curcuru, Tomas Dvorak, and Francis E. Warnock, "Cross-border returns differentials," Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (2008), 1495-1530; and Philip R. Lane and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, "Where did all the borrowing go? A forensic analysis of the U.S. external position," Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 23 (2009), 177-199. 4 See Eswar S. Prasad, "Role reversal in international finance," paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Jackson Hole Symposium, August 2011. 5 For a recent survey see Ajay Shah and Ila Patnaik, "India's financial globalisation," International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/11A7 (January 2011). 6 A related perspective is the infamous Lawson Doctrine, first enunciated in 1988, which holds that if the government is not in deficit, any current account deficit, being the outcome of optimal private-sector decisions, is of no policy concern. Among many other problems, the Lawson Doctrine misses the point that private sector decisions may impact the government's budget in bailout scenarios - the boundary between private and public is fluid — and the expectation of bailouts drives a wedge between private and social optimality. 7 See Caudio Borio and Piti Disyatat, "Global imbalances and the financial crisis: Link or no link?" BIS Working Papers No. 346, Bank for International Settlements (May 2011). 8 Viral V. Acharya and Philipp Schnabl, "Do global banks spread global imbalances? Asset-backed commercial paper during the financial crisis of 2007-09," IMF Economic Review 5% (2010), 37-73. 9 Alongside regulatory arbitrage and moral hazard, tax arbitrage is a major motivation for the proliferation of gross external asset positions. For example, money sent abroad may be able to re-enter a country in the form of tax-favored FDI. 10 As noted by Michael Hume and Andrew Sentance, "The global credit boom: Challenges for macroeconomics and policy," Journal of International Money and Finance 28 (2009), 1426-1461. 11 See Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, "Global imbalances and the financial crisis: Products of common causes," in Reuven Glick and Mark M. Spiegel, editors, Asia and the Global Financial Crisis (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2010). 12 For a partial list of references, see Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas and Maurice Obstfeld, "Stories of the twentieth century for the twenty-first," American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 4 (January 2012), forthcoming. 13 See Jonathan D. Ostry et al., "Managing capital inflows: What tools to use?" IMF Staff Discussion Note (April 2011). 14 Oscar Jorda, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor, "Financial crises, credit booms, and external imbalances: 140 years of lessons," IMF Economic Review 59 (2011), 340-378; and Carmen M. Reinhart and Vincent R. Reinhart, "Capital flow bonanzas: An encompassing view of the past and present," in Jeffrey Frankel and Christopher Pissarides, editors, International Seminar on Macroeconomics 2008 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). 15 See Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas and Helene Rey, "International financial adjustment," Journal of Political Economy 115 (August 2007), 665-703. 16 Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti (2011) offer a broad discussion of possible reasons to reduce or avoid large global imbalances. See Olivier Blanchard and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, "(Why) should current account imbalances be reduced?" IMF Staff Discussion Note (March 2011). One general question in interpreting actual current account data is its reliance on residency versus nationality. Does it matter that some of a nation's exports are produced by foreign-owned but domestically operating firms? Probably not. If the foreign-owned firm were considered to be located abroad, but still employed the home country's labor in production, the home current account, properly calculated to include the export of labor services, would not change. Of course, the preceding accounting change would affect the balance of trade. On residence versus nationality in financial data, see Borio and Disyatat (2011). |

Page Last Updated on: