IST,

IST,

Sixth Bi-monthly Monetary Policy Statement, 2019-20 Resolution of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) Reserve Bank of India

On the basis of an assessment of the current and evolving macroeconomic situation, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at its meeting today (February 6, 2020) decided to:

Consequently, the reverse repo rate under the LAF remains unchanged at 4.90 per cent and the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate and the Bank Rate at 5.40 per cent.

These decisions are in consonance with the objective of achieving the medium-term target for consumer price index (CPI) inflation of 4 per cent within a band of +/- 2 per cent, while supporting growth. The main considerations underlying the decision are set out in the statement below. Assessment Global Economy 2. Since the MPC met last in December 2019, global economic activity has remained slow-paced, but is getting differentiated across geographies. Among the key advanced economies (AEs), the US economy grew by 2.1 per cent in Q4:2019, the same pace as in Q3, with slack in consumer spending offset by government expenditure. In the euro area, economic activity slowed down in Q4 as France and Italy shrank unexpectedly amid waning consumer confidence. Growth momentum in the UK appears to have weakened in Q4 as reflected in a decline in industrial production and tepid retail sales. The Japanese economy was weighed down in Q4 by weak retail sales as reflected in subdued consumer spending in the wake of the sales tax hike in October. Industrial production in Japan was pulled down by muted global demand. 3. Among emerging market economies (EMEs), the Chinese economy slowed down to a 29-year low of 6.1 per cent in 2019, caused by sluggish domestic demand and prolonged trade tensions. In Russia, available indicators point to a loss of momentum in activity in Q4:2019 with industrial production easing, although private consumption may have provided some cushion. In Brazil, activity seems to have slowed down, as reflected in a contraction in industrial production and depressed retail sales. The South African economy recorded a growth of -0.6 per cent in Q3 and is likely to have also contracted in Q4 as industrial production slumped and household spending remained subdued amidst lingering consumer pessimism. 4. Crude oil and gold prices shot up in early January sparked by the US-Iran confrontation, but both softened from mid-January as geo-political tensions eased. By end-January, crude oil prices dipped sharply due to sell-offs triggered by the outbreak of the coronavirus. Gold prices, on the other hand, inched up towards end-January because of safe haven demand. International food prices have been rising on higher demand and supply disruptions from major exporting countries. Reflecting these developments, inflation has edged up in some major AEs and EMEs. 5. Global financial markets remained resilient in December 2019 and for the most part of January 2020 as thawing US-China trade relations and improved prospects of an orderly Brexit buoyed investors’ sentiment. Equity markets rallied across AEs and EMEs, turning bearish towards end-January with the outbreak of the coronavirus as markets braced up for the likely adverse impact on growth prospects, particularly in China. However, equity markets in most economies recovered some of the losses in early February. Bond yields, which had hardened in the US towards the end of 2019 as investors turned to riskier assets, softened in January 2020, especially after the US Fed left the policy rate unchanged and assured the extension of repo operations. In the euro area, bond yields sank further into negative territory in January. Yields also softened across several EMEs. In currency markets, the US dollar strengthened in January against major advanced economies in sympathy with factors impacting US bond markets. EME currencies, which were generally trading with an appreciating bias, have depreciated since the last week of January. Domestic Economy 6. Moving on to the domestic economy, the first advance estimates (FAE) released by the National Statistical Office (NSO) on January 7, 2020 placed India’s real gross domestic product (GDP) growth for 2019-20 at 5.0 per cent. In its January 31 release, the NSO revised real GDP growth for 2018-19 to 6.1 per cent from 6.8 per cent given in the provisional estimates of May 2019. On the supply side, growth of real gross value added (GVA) is estimated at 4.9 per cent in 2019-20 as compared with 6.0 per cent in 2018-19. 7. Turning to more recent indicators, both production and imports of capital goods – two key pointers of investment activity – continued to contract in November/December, though at a moderate pace compared with the previous month. Revenue expenditure of the Centre (excluding interest payments and subsidies) remained robust in Q3, indicative of the counter-cyclical buffer to domestic demand being provided by government final consumption. As per revised estimates given in the Union Budget, growth in revenue expenditure of the Centre (excluding interest payments and subsidies) is estimated to be lower in Q4 compared with Q3. 8. On the supply side, rabi sowing has been higher by 9.5 per cent up to January 31, 2020 compared with a year ago. The north east monsoon rainfall was above normal. Storage in major reservoirs – the main source of irrigation during the rabi season – was 70 per cent of the full reservoir level (as on January 30, 2020) as compared with 45 per cent a year ago. Based on the first advance estimates, horticulture production is estimated to have risen 0.8 per cent to a record level in 2019-20. Production of vegetables is estimated to have increased by 2.6 per cent in 2019-20 due to higher production of onions, potatoes and tomatoes. 9. Industrial activity, measured by the index of industrial production (IIP), improved in November after contracting in the previous three months. The output of core industries returned to positive territory in December after four months of contraction, buoyed by five out of eight of its constituents – coal; refinery products; fertilisers; steel; and cement. Capacity utilisation (CU) in the manufacturing sector, measured by the Reserve Bank’s order books, inventory and capacity utilisation survey (OBICUS), fell to 69.1 per cent in Q2 from 73.6 per cent in Q1; seasonally adjusted CU also eased to 70.3 per cent from 73.4 per cent. The Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey points to weak demand conditions facing the manufacturing sector in Q3:2019-20. The Reserve Bank’s business expectations index suggests an improvement in Q4. This is corroborated by the manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) for January 2020 which picked up sharply to 55.3 from 51.2 in November 2019 on the back of increased output and new orders. 10. Several high frequency indicators of services have turned upwards in the recent period, pointing to a modest revival in momentum, although the outlook is still muted. Amongst indicators of rural demand, while tractor sales grew by 2.4 per cent in December after ten months of a decline, motorcycle sales continued to contract. Domestic air passenger traffic – an indicator of urban demand – posted double digit growth in November, followed by a modest growth in December. Growth in three-wheeler sales and railway freight traffic has accelerated, while port traffic turned around in December. On the other hand, passenger vehicle sales continued to contract. The PMI services index improved to 55.5 in January 2020 from 52.7 in November 2019, boosted by a rise in new business and output. 11. Retail inflation, measured by year-on-year changes in the CPI, surged from 4.6 per cent in October to 5.5 per cent in November and further to 7.4 per cent in December 2019, the highest reading since July 2014. While food group inflation rose to double digits, the fuel group moved out of deflation. Inflation in CPI excluding food and fuel continued to edge up from its October trough. 12. CPI food inflation increased from 6.9 per cent in October to 12.2 per cent in December, primarily caused by a spike in onion prices due to unseasonal rains in October-November. Excluding onions, food inflation would have been lower by 4.7 percentage points and headline inflation by 2.1 percentage points in December. In addition, inflation in several other food sub-groups such as milk, pulses, cereals, edible oils, eggs, meat and fish also firmed up. 13. The CPI fuel group registered inflation of 0.7 per cent in December, reflecting an increase in prices of electricity and firewood and chips; and in administered prices of kerosene. Together they constitute 68 per cent of the CPI fuel basket. LPG inflation remained in negative territory despite a sharp recovery in prices in November-December. 14. CPI inflation excluding food and fuel rose from a low of 3.4 per cent in October to 3.8 per cent by December 2019, driven by an increase in inflation in mobile phone charges, petrol, diesel, transportation fares and clothing. Housing inflation moderated further in December reflecting subdued demand. 15. Households’ inflation expectations eased in the January 2020 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey – after a sharp pick-up in the previous round – with the 3-month ahead and 1-year ahead inflation expectations falling by 60 basis points (bps) and 70 bps, respectively. Based on the Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey, consumer spending on non-essential items of consumption contracted from a year ago; however, overall spending is expected to rise, going forward, reflecting an increase in prices. The December 2019 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey suggests that the input and output prices of manufacturing firms remained subdued in Q3:2019-20 and are likely to remain so in Q4. 16. Overall liquidity in the system remained in surplus in December 2019 and January 2020. Average daily net absorption under the liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) amounted to ₹ 2.61 lakh crore in December 2019. In January 2020, the average daily net absorption of surplus liquidity soared to ₹ 3.18 lakh crore. The Reserve Bank conducted four auctions involving the simultaneous purchase of long-term and sale of short-term government securities under open market operations (OMOs) for a notified amount of ₹ 10,000 crore each during December and January (December 23 and 30, 2019 and January 6 and 23, 2020). Reflecting these operations, the 10-year G-sec yield softened cumulatively by 15 bps between December 19, 2019 and January 31, 2020. During the intervening period, however, the yields fell by as much as 25 bps. The weighted average call rate (WACR) traded below the policy repo rate (on an average) by 10 bps in December and by 19 bps in January on easy liquidity conditions. 17. Monetary transmission across various money market segments and the private corporate bond market has been sizable. As against the cumulative reduction in the policy repo rate by 135 bps since February 2019, transmission to various money and corporate debt market segments up to January 31, 2020 ranged from 146 bps (overnight call money market) to 190 bps (3-month CPs of non-banking finance companies). Transmission through the longer end of government securities market was at 73 bps (5-year government securities) and 76 bps (10-year government securities). Transmission to the credit market is gradually improving. The 1-year median marginal cost of funds-based lending rate (MCLR) declined by 55 bps during February 2019 and January 2020. The weighted average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans sanctioned by banks declined by 69 bps and the WALR on outstanding rupee loans by 13 bps during February-December 2019. 18. After the introduction of the external benchmark system, most banks have linked their lending rates for housing, personal and micro and small enterprises (MSEs) to the policy repo rate of the Reserve Bank. During October-December 2019, the WALRs of domestic (public and private sector) banks on fresh rupee loans declined by 18 bps for housing loans, 87 bps for vehicle loans and 23 bps for loans to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). 19. Export growth continued to contract in November-December 2019, reflecting the slowdown in global trade. Import growth slumped in November-December 2019, with contraction in both oil and non-oil non-gold imports. While the latter reflected the underlying weakness in domestic demand and was spread across categories such as transport equipment, coal, iron and steel and chemicals, outgoes on account of oil imports were lower due to a cut back in oil import volume. Gold imports also declined in December 2019. On the financing side, net foreign direct investment rose to US$ 24.4 billion in April-November 2019 from US$ 21.2 billion a year ago. Net foreign portfolio investment was of the order of US$ 8.6 billion in 2019-20 (up to February 4) as against net outflows of US$ 14.2 billion in the same period last year. In addition, net investments by FPIs under the voluntary retention route have aggregated US$ 7.8 billion since March 11, 2019. External commercial borrowings were higher at US$ 13.4 billion during April-December 2019 as compared with US$ 2.5 billion during the same period a year ago. India’s foreign exchange reserves were at US$ 471.4 billion on February 4, 2020 – an increase of US$ 58.5 billion over end-March 2019. Outlook 20. In the fifth bi-monthly resolution of December 2019, CPI inflation was projected at 5.1-4.7 per cent for H2:2019-20 and 4.0-3.8 per cent for H1:2020-21, with risks broadly balanced. The actual inflation outcome for Q2 at 5.8 per cent overshot projections by 70 bps, primarily due to the intensification of the onion price shock in December 2019 on account of unseasonal rains in October-November. 21. Going forward, the inflation outlook is likely to be influenced by several factors. First, food inflation is likely to soften from the high levels of December and the decline is expected to become more pronounced during Q4:2019-20 as onion prices fall rapidly in response to arrivals of late kharif and rabi harvests. Higher vegetables production, despite the early loss due to unseasonal rain, is also likely to have a salutary impact on food inflation. On the other hand, the recent pick-up in prices of non-vegetable food items, specifically in milk due to a rise in input costs, and in pulses due to a shortfall in kharif production, are all likely to sustain. These factors could impart some upward bias to overall food prices. Second, crude prices are likely to remain volatile due to unabating geo-political tensions in the Middle East on the one hand, and the uncertain global economic outlook on the other. Third, there has been an increase in input costs for services, in recent months. However, subdued demand conditions, muted pricing power of corporates and the correction in energy prices since the last week of January may limit the pass-through to selling prices. Fourth, domestic financial markets remain volatile reflecting both global and domestic factors, which may have an influence on the inflation outlook. Fifth, base effects would turn favourable during Q3:2020-21. Sixth, the increase in customs duties on items of retail consumption in the budget may result in only a marginal one-time uptick in inflation. Taking into consideration these factors, and under the assumption of a normal south west monsoon in 2020-21, the CPI inflation projection is revised upwards to 6.5 per cent for Q4:2019-20; 5.4-5.0 per cent for H1:2020-21; and 3.2 per cent for Q3:2020-21, with risks broadly balanced (Chart 1). 22. Turning to the growth outlook, real GDP growth for 2019-20 was projected in the December 2019 policy at 5.0 per cent – 4.9-5.5 per cent in H2. GDP growth for H1:2020-21 was projected at 5.9-6.3 per cent. For 2020-21, the growth outlook will be influenced by several factors. First, private consumption, particularly in rural areas, is expected to recover on the back of improved rabi prospects. The recent rise in food prices has shifted the terms of trade in favour of agriculture, which will support rural incomes. Second, the easing of global trade uncertainties should encourage exports and spur investment activity. The breakout of the coronavirus may, however, impact tourist arrivals and global trade. Third, monetary transmission in terms of a reduction in lending rates and financial flows to the commercial sector has progressed vis-à-vis the last policy, and this could spur both consumption and investment demand. Fourth, the rationalisation of personal income tax rates in the Union Budget 2020-21 should support domestic demand along with measures to boost rural and infrastructure spending. Taking into consideration the above factors, GDP growth for 2020-21 is projected at 6.0 per cent – in the range of 5.5-6.0 per cent in H1 and 6.2 per cent in Q3 (Chart 2).   23. The MPC notes that inflation has surged above the upper tolerance band around the target in December 2019, primarily on the back of the unusual spike in onion prices. Over the coming weeks and months, onion prices are likely to ebb as supply conditions improve. The salutary effects on headline inflation are, however, likely to be tempered by hardening of prices of other food items, notably those of pulses and proteins. Meanwhile adjustments to telecom charges are imparting cost-push pressures to CPI inflation excluding food and fuel. Going forward, the trajectory of inflation excluding food and fuel needs to be carefully monitored as the pass-through of remaining revisions in mobile phone charges, the increase in prices of drugs and pharmaceuticals and the impact of new emission norms play out and feed into inflation formation. The MPC anticipates that the combination of these factors may keep headline inflation elevated in the short-run, at least through H1:2020-21. Overall, the inflation outlook remains highly uncertain. Accordingly, the MPC will remain vigilant about the potential generalisation of inflationary pressures as several of the underlying factors cited earlier appear to be operating in concert. 24. At the same time, the MPC observes that the economy continues to be weak and the output gap remains negative. While some high-frequency indicators have turned around and point to a lift in the momentum of economic activity, there is a need to await incoming data to gauge their sustainability. Financial flows to the commercial sector have improved in recent months. The Union Budget 2020-21 has introduced several measures to provide an impetus to growth. While the emphasis on boosting the rural economy and infrastructure should help the growth momentum in the near-term, the corporate tax rate cuts of September 2019 should help boost the growth potential over the medium-term. The fiscal deficit of the Central Government for 2019-20 is placed at 3.8 per cent of GDP in the revised estimates as against 3.3 per cent of GDP in the budget estimates. The higher fiscal deficit in 2019-20 has not resulted in an increase in market borrowings compared to the budget estimates. The fiscal deficit is budgeted to decline to 3.5 per cent of GDP for 2020-21. Fresh gross market borrowings are budgeted to increase by ₹ 70,000 crore to ₹ 7.8 lakh crore in 2020-21 from ₹ 7.1 lakh crore in 2019-20. The MPC notes that while there is a need for adjustment in interest rates on small saving schemes, the external benchmark system introduced from October 1, 2019 has strengthened monetary transmission. These developments should amplify the effects of the cumulative policy rate reductions undertaken by the Reserve Bank since February 2019 and pull up domestic demand going forward. 25. The MPC recognises that there is policy space available for future action. The path of inflation is, however, elevated and on a rising trajectory through Q4:2019-20. The outlook for inflation is highly uncertain at this juncture. On the other hand, economic activity remains subdued and the few indicators that have moved up recently are yet to gain traction in a more broad-based manner. Given the evolving growth-inflation dynamics, the MPC felt it appropriate to maintain status quo. Accordingly, the MPC decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged and persevere with the accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive growth, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target. 26. Dr. Chetan Ghate, Dr. Pami Dua, Dr. Ravindra H. Dholakia, Dr. Janak Raj, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Shri Shaktikanta Das voted in favour of the decision. 27. The minutes of the MPC’s meeting will be published by February 20, 2020. 28. The next meeting of the MPC is scheduled during March 31, April 1 and 3, 2020. (Yogesh Dayal) Press Release: 2019-2020/1890 |

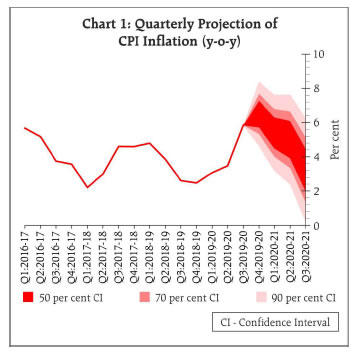

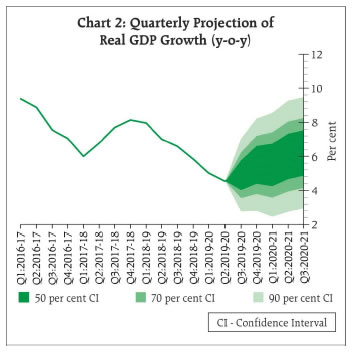

પેજની છેલ્લી અપડેટની તારીખ: