IST,

IST,

Discussion Paper on Introduction of Expected Credit Loss Framework for Provisioning by Banks

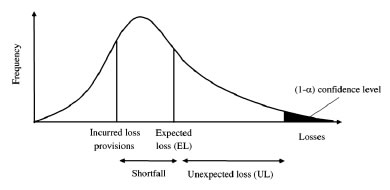

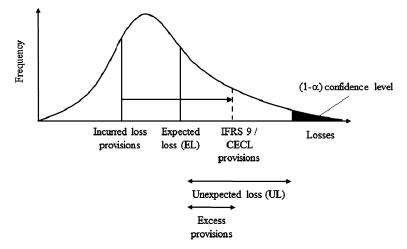

1. Introduction 1.1. The exposures taken by banks are inherently susceptible to various risks, of which credit risk is of primary importance. Credit risk represents the risk that the loans given by a bank will not be paid in full, i.e., the bank is likely to suffer some level of losses on its exposures. Such credit losses are a natural corollary of banking business which involves lending to ventures based on reasonable assessment of their viabilities. Since such assessments involve estimations of future trajectories of the performance of a venture as well as that of the macroeconomy in which such ventures are embedded, an element of uncertainty is inherent in such assessments, especially since the assessments would also involve biases such as projections of the bank’s own historical experiences into the future. Thus, the probability of deviations from such assessments is non-zero at any point. It thus follows that the probability of losses arising out of such assessment is also non-zero at any point. 1.2. Standard approaches of regulating credit risk classify the losses that banks may face on their credit portfolio broadly into two categories – expected losses and unexpected losses. While unexpected losses are to be mitigated through maintaining capital, expected losses are to be mitigated through pricing policies and loan loss provisions. Such classification intuitively highlights the importance of loan loss provisioning – the burden of mitigating expected losses uncovered by the provisions maintained by the banks would also fall on the capital maintained by the banks, which then leaves the banks vulnerable to materialization of unexpected losses thereby increasing the probabilities of bank failure. 1.3. In India, presently, banks are required to make loan loss provisions based on an “incurred loss” approach, which used to be the standard globally till recently. The gist of this approach is that banks need to provide for losses that have occurred / incurred. An example in the Indian context is the requirement for banks to make provisions at the rate of 15% in case of secured loans and 25% for unsecured loans when a loan exposure is classified as non-performing asset (NPA). As can be seen, the event of classification of a loan as NPA must happen first before the provisions are to be maintained by the banks. Since default is a lagging indicator of credit risk and since classification of an exposure as NPA normally takes place after a borrower is overdue for more than 90 days, loan loss provisions are made by banks with significant delays after the borrower may have started facing financial difficulties thereby increasing the credit risk faced by the banks, which then remained unmitigated till the regulatory requirement of loan loss provisions was triggered upon the classification of the exposure as NPA. Ideally, the bank should have recognized the increase in the credit risk and started making provisions for the losses that would be expected in such exposure much before the default happened let alone the subsequent classification of the exposure as NPA. 1.4. The incurred loss approach used to be the global standard as well till very recently. However, this meant that loan loss provisioning used to happen much later to the increase in credit risk to the banks. Such delays in recognizing expected losses under an “incurred loss” approach was found to exacerbate the downswing during the financial crisis of 2007-09. Faced with a systemic increase in defaults, the delay in recognizing loan losses resulted in banks having to make higher levels of provisions which ate into the capital maintained precisely at a time when banks needed to shore up their capital, thereby affecting their resilience and posing systemic risks. Further, the delays in recognizing loan losses overstated the income generated by the banks which, coupled with dividend pay-outs, impacted the capital base of banks because of reduced internal accruals, which also affected the resilience of banks. 1.5. This experience prompted the G20 and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) to recommend to accounting standard setters to modify the provisioning practices to incorporate a more forward looking approach rather than to require the losses to happen before recognizing the same. In response, both the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) have adopted provisioning standards that require the use of expected credit loss (ECL) models rather than incurred loss models. In principle, the approach requires a credit institution to estimate expected credit losses based on forward-looking estimations rather than wait for credit losses to be incurred before making corresponding loss provisions. The IASB published International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9 in July 2014, which took effect on January 1, 2018 (early adoption was allowed), while the FASB published its final standard on current expected credit losses (CECL) in June 2016 which took effect on January 1, 2020 for most large and mid-sized U.S. banks. 1.6. To further enhance the resilience of the banking system, Reserve Bank proposes to amend the prudential regulations governing loan loss provisioning by banks to incorporate the more forward looking expected credit losses approach as against the extant “incurred loss” approach. This Discussion Paper is the first step in that direction and aims to lay down the principles that would govern the proposed transition, on which public comments are sought. 1.7. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Chapter 2 summarises the extant instructions on provisioning to be followed by commercial banks. Chapter 3 describes the expected credit loss approach in brief along with brief comparisons of the two major accounting systems that have incorporated the approach, viz., IFRS issued by IASB and US GAAP issued by FASB. Chapter 4 outlines the proposed approach for implementing an expected credit loss approach for loss provisions by banks in India. In particular, the principle-based approach for credit loss estimations have been supplemented by proposed regulatory backstops. Chapter 5 concludes the discussion by elaborating issues pertaining to implementation of the proposed framework and guidance on transition. 1.8. The feedback on the issues discussed in the paper may be submitted by February 28, 2023 to The Chief General Manager, Credit Risk Group, Department of Regulation, Central Office, Reserve Bank of India, 12th Floor, Central Office Building, Shahid Bhagat Singh Marg, Fort, Mumbai – 400001 or by e-mail with the subject line “Discussion Paper on expected credit loss approach for provisioning by banks”. RBI expects that the feedback will be properly reasoned and wherever necessary, supported by detailed data analysis and quantitative evidence. 2. Evolution of provisioning requirements for banks in India 2.1. Under the current instructions, the level of provisions required to be maintained by banks against credit exposures are linked to the respective asset classification of the exposures. However, till the mid-1980s, there were no standardised guidelines for assessing the quality of individual advances of banks and for making adequate provisions for bad loans. The management of bad loans had been largely left to the management and auditors of the banks. 2.2. The Committee to Consider Final Accounts of Banks (Chairperson: Shri A Ghosh) in their report submitted in 1985 noted that there was no consensus for the basis on which provisions should be maintained in respect of bad loans and recommended that a classification system of health codes for the bank advances, which had been recommended by the Pendharkar Working Group on the system of inspection of banks (1985), should indicate the loans for which provisions for bad losses need to be maintained by the banks. RBI advised banks vide circular DBOD.No.Fol.BC.136/C.249-85 dated November 7, 1985 to classify their advances into the following categories with a health code assigned to each borrower account:

2.3. RBI also directed banks vide circulars dated DBOD.No.BP.BC.133/C.469(W)-89 dated May 26, 1989 and DBOD.No.BP.BC.42/C.469(W)-90 dated October 31, 1990 that interest income should not be recognised in respect of advances covered by Health Codes 6 to 8 until it is realised, in order to avoid inflation of income generated by the banks by inclusion of interest which is not likely to be realised. In respect of advances falling in Health Code 4, banks were advised to evolve a realistic system in the matter of income recognition taking into account the prospects of realizability of the security. 2.4. The Committee on the Financial System (Chairperson: Shri M Narasimham) in their report submitted in November 1991 recommended that for the purpose of provisioning, banks and financial institutions should classify their assets by compressing the Health Codes in the following broad groups: (i) Standard; (ii) Sub-standard; (iii) Doubtful; and (iv) Loss. The Committee also recommended that RBI should prescribe clear and objective definitions for the above categories as well as specific prudential guidelines regarding the applicable levels of provisions to be maintained in respect of the above categories. 2.5. Accordingly, RBI issued the following prudential guidelines, among other instructions, to banks vide circular DBOD.No.BC.129/21.04.043/92 dated April 27, 1992: • An amount under any of the credit facilities is to be treated as "past due" when it has not been paid on the due date. • A "non-performing asset" (NPA) should be defined as a credit facility in respect of which interest has remained unpaid for a period of four quarters during the year ending March 31, 1993; three quarters during the year ending March 31, 1994; and two quarters during the year ending March 31, 1995 and onwards. • Standard asset is one which does not display any problems, and which does not carry more than normal risk attached to the business. Such an asset is not a NPA. • Sub-standard asset is one which has been classified as NPA for a period not exceeding two years. In such cases, the current net worth of the borrower/guarantor or the current market value of the security charged is not enough to ensure recovery of the dues to the bank in full. In other words, such an asset will have well defined credit weaknesses that jeopardise the liquidation of the debt and characterised by the distinct possibility that the bank will sustain some loss, if deficiencies are not corrected. In the case of term loans, those where instalments of principal are overdue for periods exceeding one year but not exceeding two years should be treated as sub-standard. An asset where the terms of the loan agreement regarding interest and principal have been renegotiated or rescheduled after commencement of production, should be classified as sub-standard and should remain in such category for at least two years of satisfactory performance under the renegotiated or rescheduled terms. In other words, the classification of an asset should not be upgraded merely as a result of rescheduling, unless there is satisfactory compliance of the above condition. For sub-standard assets, a general provision of 10% of total outstanding have to be maintained. • A doubtful asset is one which has remained NPA for a period exceeding two years. In the case of term loans, those where instalments of principal have remained overdue for a period exceeding two years should be treated as doubtful. Here too, as in the case of sub-standard assets rescheduling does not entitle a bank to upgrade the quality of an advance automatically. For doubtful assets, provisions have to be maintained as below:

• A loss asset is one where loss has been identified by the bank or internal or external auditors or the RBI inspection, but the amount has not been written off, wholly or partly. In other words, such an asset is considered uncollectable and of such little value that its continuance as a bankable asset is not warranted although there may be some salvage or recovery value. The entire assets should be written off. If the assets are permitted to remain in the books for any reason, 100% of the outstanding should be provided for. 2.6. It was later clarified vide circular DBOD.No.BC.59/21.04.043/92 dated December 17, 1992 that an amount should be considered "past due" when it remains outstanding for 30 days beyond due date. 2.7. In line with the recommendations of the Committee on Banking Sector Reforms (1998) (Chairperson: Shri M Narasimham), the time frame for classification of an asset as doubtful was reduced to having remained in sub-standard category for 18 months instead of 24 months, vide circular DBOD.No.BP.BC.103/21.01.002/99 dated October 31, 1998. In the same circular, banks were instructed to maintain a general provision on standard assets of a minimum of 0.25 percent from the year ending March 31, 2000. 2.8. The determination of NPA status was changed from a “past due” basis to an “overdue” basis vide circular DBOD.No.BP.BC.31/21.04.048/00-01 dated October 10, 2000. Accordingly, with effect from March 31, 2001, a NPA would be an advance where

2.9. The 90-day norm for NPA classification was introduced vide circular DBOD.No.BP.BC.116/21.04.048/2000-2001 dated May 2, 2001 in order to achieve convergence with international best practices and to ensure greater transparency. Accordingly, with effect from March 31, 2004, a NPA would be a loan or an advance where;

2.10. In line with the recommendations of the Committee on Banking Sector Reforms (1998) (Chairperson: Shri M Narasimham), the time frame for classification of an asset as doubtful was further reduced to having remained in sub-standard category for 12 months with effect from March 31, 2005, vide circular DBOD.No.BP.BC.100/21.01.002/2001-02 dated May 9, 2002. 2.11. The approach towards asset classification has remained largely unchanged since then even though the provisioning requirements for each category of asset classification has undergone modifications. Extant instructions on asset classification and provisioning 2.12. The asset classification and provisioning norms currently applicable to commercial banks operating in India are consolidated mainly in the Master Circular on Income Recognition, Asset Classification, and Provisioning dated April 1, 2022. As per the extant instructions, NPA is a loan or an advance where;

2.13. There are exemptions to the above classification. For instance, advances against term deposits, NSCs eligible for surrender, IVPs, KVPs and life policies need not be treated as NPAs, provided adequate margin is available in the accounts. The credit facilities backed by guarantee of the Central Government though overdue may be treated as NPA only when the Government repudiates its guarantee when invoked. 2.14. The provisioning requirements based on asset classification are as under: • Banks should make general provision for standard assets at the following rates for the funded outstanding on global loan portfolio basis:

• For sub-standard assets:

• For doubtful assets:

• Loss assets should be written off. If loss assets are permitted to remain in the books for any reason, 100 percent of the outstanding should be provided for. 2.15. As can be seen from above, the extant requirements follow the “incurred loss” approach in that the level of provisions is contingent on the asset classification of a particular exposure. The asset classification is linked to the record of recovery and therefore provides information regarding the risk to the bank only on a post facto basis when it comes to materialisation of credit risk. Also, if a bank is prevented from recognising the increase in credit risk associated with a credit exposure even on a post facto basis through asset classification, due to legal or other reasons, it further impacts the level of loan loss provisions that the bank will have to maintain thereby increasing the risks posed to the financial system. 3. Expected Credit Loss Approach 3.1. Apart from the practical deficiencies already noted previously, the incurred loss approach for loan loss provisions is inconsistent with the fundamental principles of financial valuation in which the value of an asset is arrived at as the summation of the stream of present value of cash flows expected over the lifetime of the asset. The approach is also inconsistent with the prudential separation of credit risk mitigation responsibilities assigned to capital and to provisions – since the provisions are not maintained with a forward-looking perspective, the capital maintained has to partly accommodate the burden of expected credit losses, which then materialises in the form of volatility in regulatory capital levels when events trigger the provisioning requirements under incurred loss approach. The expected credit loss approach to loan loss provisioning attempts to address the above shortcomings. 3.2. In principle, expected credit losses represent the probability weighted estimate of the present value of all cash shortfalls from an instrument. The cash shortfalls occur when the cash receipts that a credit institution expects to receive from an instrument is less than the contractual cash flow receipts. Since the cash shortfalls are discounted for this purpose, a delay in payment, even if not an actual shortfall in amount of payment, will also give rise to expected credit losses. Thus, the estimation of expected credit loss depends upon the assessment of the management of the credit institution regarding the likelihood of cash shortfalls after considering all available factors that may be of relevance to the assessment. 3.3. As mentioned previously, expected credit loss approach for credit impairment is an integral part of the IFRS issued by IASB and the US GAAP issued by the FASB. In the case of IFRS, the guidelines pertaining to impairment in financial instruments are dealt with in IFRS 9 (Financial Instruments). In the case of US GAAP, the modification related to impairment in financial instruments is dealt with in Topic 326: Financial Instruments – Credit Losses. IFRS 9 – Financial Instruments 3.4. IFRS 9 deals with recognition / derecognition, measurement, impairment and hedge accounting associated with financial instruments. Since the assets and liabilities of banks are almost exclusively financial instruments, this standard would be of specific relevance to the current discussion. 3.5. The standard requires that classification and measurement of financial assets held by an entity has to be based on the business model of the entity for managing the financial asset as well as the contractual cash flow characteristics of the financial asset in the following manner:

3.6. For financial assets measured at amortised cost, interest revenue should be calculated using effective interest rate method. Amortised cost represents the cost at which an asset is measured at initial recognition adjusted for principal repayments and cumulative amortisation using the effective interest rate method. Effective interest rate is the rate that exactly discounts future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the asset to the gross carrying amount of the asset, i.e., amortised cost before adjusting for any loss allowance. In the case of financial assets that subsequently become credit impaired, effective interest rate has to be applied to the amortised cost in the subsequent reporting periods for the purpose of recognising interest revenue. A financial asset is credit-impaired when one or more events that have a detrimental impact on the estimated future cash flows of that financial asset have occurred. 3.7. The requirement for impairment using expected credit loss approach under IFRS 9 applies to financial assets that are measured under amortised cost or at fair value through other comprehensive income. The above impairment requirement also applies to a lease receivable, a contract asset or a loan commitment, and a financial guarantee contract. 3.8. IFRS 9 requires that on each reporting date, if the credit risk on a financial asset has not increased significantly since initial recognition, the entity should measure the loss allowance for that financial asset at an amount equal to 12-month expected credit losses. The 12-month expected credit losses are the credit losses that arise through the expected lifetime of the instrument on account of events that are likely to occur in the subsequent 12 months. However, on the reporting date, if the credit risk on a financial asset has increased significantly since initial recognition, the entity should measure the loss allowance at an amount equal to the lifetime expected credit losses. Regardless of the above, loss allowance has to be measured always at an amount equal to lifetime expected credit losses for trade receivables or contract assets and lease receivables. Lifetime expected credit losses are the expected credit losses that result from all possible default events over the expected life of the financial instrument. 3.9. Thus, a three-stage classification of financial assets is envisaged:

3.10. The measurement of expected credit loss should reflect: (a) an unbiased and probability-weighted amount that is determined by evaluating a range of possible outcomes; (b) the time value of money; and (c) reasonable and supportable information that is available without undue cost or effort at the reporting date about past events, current conditions and forecasts of future economic conditions. Even though an entity need not necessarily identify every possible scenario, it should consider the risk or probability that a credit loss occurs, even if the possibility of a credit loss occurring is very low. The standard also provides certain practical expedients to simplify the determination of significant increase in credit risk and measurement of expected credit losses, viz., assumption of no increase in credit risk if an asset was determined to have low credit risk at the reporting date, rebuttable presumption that the credit risk on a financial asset has increased significantly since initial recognition when contractual payments are more than 30 days past due, provision matrix for calculation of the expected credit losses on trade receivables etc. Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) under US GAAP 3.11. Topic 326: Financial Instruments – Credit Losses under the US GAAP requires that full amount of expected credit losses (referred to as current expected credit losses or CECL) be recorded for all financial assets measured at amortised cost instead of the two-step expected credit loss assessment under IFRS 9. Other major differences between US GAAP and IFRS 9 regarding measurement of impairment of financial assets are summarised below:

3.12. The divergences in the approaches adopted by FASB and IASB towards achieving the common objective of implementing expected credit loss approach for credit impairment stems mainly from the fact that interaction between the role of prudential regulators and loss allowances is historically stronger in the US and since many users of financial statements in the US place a greater weight on the adequacy of loss allowances in the balance sheet. Expected Credit Losses and Bank Capital 3.13. As mentioned previously, there is an allocation of mitigation responsibilities in respect of unexpected losses and expected losses between capital and provisions respectively. Incurred loss approach resulted in provisioning shortfalls that was then to be accounted for in the computation of capital requirements.  3.14. The impact of adopting the forward looking expected credit loss approach to estimating loss provisions, instead, is likely to result in excess provisions as compared to shortfall in provisions, which also is adjusted for in the computation of capital requirements.  3.15. The above description assumes that the determination of capital requirements is made under the Internal Rating based approach, and hence may not be directly relevant to banks whose determination of capital charge is made under the Standardised approach. Regardless, it can be intuitively seen that the increase in provisions, that too on a forward-looking basis, would reduce the mitigation that capital has to accord for the portion of expected losses that were not covered through provisions under the “incurred loss” approach, even for banks following Standardised approach for measuring capital charges. Classification as general and specific provisions 3.16. A more relevant aspect for banks following Standardised approach for measuring capital charges would be the prudential classification of loss provisions estimated under the expected credit loss approach into general provisions and specific provisions. General provisions are provisions held against future, presently unidentified losses that are freely available to meet losses which subsequently may materialise. Provisions ascribed to identified deterioration of particular assets or known liabilities, whether individual or grouped, are specific provisions. The Basel norms on capital adequacy for banks permit inclusion of general provisions in Tier 2 capital of 1.25% of credit risk-weighted assets (RWA) in respect of banks following Standardised approach for measuring capital charges. 3.17. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) has noted that the extant regulatory concepts of general provisions and special provisions have been interpreted by national supervisors in an environment in which the applicable accounting standards have generally followed an incurred loss model. BCBS further observed that jurisdictions have interpreted the definitions of general provisions and specific provisions differently, at least in part due to historical differences in how the incurred loss model for credit losses has been applied in individual jurisdictions. With the implementation of provisioning based on expected credit losses, the fact that the existing regulatory distinction between general provisions and specific provisions does not directly correspond to how provisions would be measured under the new accounting standards further complicates efforts to achieve more consistent interpretations of the regulatory definitions. 3.18. Regardless of the above, BCBS has decided to retain the current regulatory treatment of provisions for an interim period during which jurisdictions would extend their existing approaches to categorising provisions as general provisions or specific provisions to provisions calculated under the applicable expected credit loss accounting model. BCBS has recommended that regulatory authorities provide guidance, as appropriate, on how they intend to categorise expected credit loss provisions as general provisions or specific provisions in their jurisdiction to ensure consistency in this categorisation by the banks within their jurisdiction. Point-in-time vs Through the cycle 3.19. Another distinction between the requirements of estimation of provisions using the expected credit loss approach and estimation of bank capital, both of which require an estimation of probability of default, is in the nature of that probability – the bank capital computations require estimation of a through-the-cycle probability of default (i.e., estimated in economic conditions that are neutral to business cycles) whereas loss provisions based on expected credit loss approach requires estimation of point in time probability of default (i.e., probability of default computed under the current economic conditions without any prudential adjustments). This distinction underlines the divergences in objectives of prudential regulation and financial presentation wherein the former is concerned about maximising the chances of bank survival during an economic downturn (hence, the estimations of loss given default for capital computation have to be under the assumption of economic downturn regardless of the actual state of economy) while the latter is more concerned about providing information relevant to decision making by agents dealing with a firm (hence, the estimates have to be based on the current economic conditions). Therefore, even if a bank is estimating probabilities of default for capital computation, the same cannot be directly used for estimating expected credit losses, and would require additional adjustments for the purpose. Transitional arrangements for impact on bank capital 3.20. BCBS has acknowledged that the transition to expected credit loss based accounting will generally result in an increase in the overall amount of loan loss provisions, which in many cases will reduce the capital ratios of banks as they transition to the ECL approach. Accordingly, the following transition arrangements have been prescribed under CAP90 of the Basel standards for expected credit loss accounting: • The transitional arrangement must apply only to provisions that are “new” under an ECL accounting model. “New” provisions are provisions which do not exist under accounting approaches applied prior to the adoption of an ECL accounting model. • The transitional arrangement must adjust Common Equity Tier 1 capital. Where there is a reduction in Common Equity Tier 1 capital due to new provisions, net of tax effect, upon adoption of an ECL accounting model, the decline in Common Equity Tier 1 capital (the “transitional adjustment amount”) must be partially included (i.e., added back) to Common Equity Tier 1 capital over a number of years (the “transition period”) commencing on the effective date of the transition to ECL accounting. • Jurisdictions must choose whether banks under their supervision determine the transitional adjustment amount throughout the transition period by either:

• The transitional adjustment amount may be calculated based on the impact on Common Equity Tier 1 capital upon adoption of an ECL accounting model or from accounting provisions disclosed before and after the adoption of an ECL accounting model. • The transition period commences from the date upon which a bank adopts ECL accounting in a jurisdiction that requires or permits the implementation of an ECL accounting framework. The transition period must be no more than five years. • During the transition period, the transitional adjustment amount will be partially included in (i.e., added back to) Common Equity Tier 1 capital. A fraction of the transitional adjustment amount (based on the number of years in the transition period) will be included in Common Equity Tier 1 capital during the first year of the transition period, with the proportion included in Common Equity Tier 1 capital phased out each year thereafter during the course of the transition period on a straight-line basis. The impact of ECL provisions on Common Equity Tier 1 capital must not be fully neutralised during the transition period. • The transitional adjustment amount included in Common Equity Tier 1 capital each year during the transition period must be taken through to other measures of capital as appropriate (eg Tier 1 capital and total capital), and hence to the calculation of the leverage ratio and of large exposures limits. • Jurisdictions must choose between applying the consequential adjustments listed below or a simpler approach to ensure that banks do not receive inappropriate capital relief. (An example of a simpler approach that would not provide inappropriate capital relief would be amortising the transitional arrangement more rapidly than otherwise.)

• Jurisdictions must publish details of any transitional arrangement applied, the rationale for it, and its implications for supervision of banks (eg whether supervisory decisions will be based solely on regulatory metrics which incorporate the effect of the transitional arrangement). Jurisdictions that choose to implement a transitional arrangement must require their banks to disclose:

Regulatory approaches for expected credit losses provisioning 3.21. Since accounting standards issued by IASB and FASB consist of detailed principles on estimating expected credit losses, regulators in jurisdictions where expected credit loss approach has already been implemented have issued only guidance and expectations from the management of the regulated banks. Such expectations have generally stressed on the importance of responsibilities vested with the management of banks for putting in place and maintaining a sound credit risk management system that enables reliable estimation of expected credit losses. The guidance has also laid out the expectations of the regulators regarding the way management is expected to apply their discretions / opinions as well as the practical expedients available under the accounting frameworks. 3.22. BCBS (2015b) contains detailed guidance on credit risk and accounting for expected credit losses, which is structured around the following 11 principles:

4. An approach for loan loss provisioning based on expected credit losses for India 4.1. The discussion on ECL under IFRS 9 and CECL in the previous chapter provides two well-accepted approaches towards replacing incurred loss approach for loan loss provisioning with an expected credit loss approach. The divergences in the methodologies adopted by FASB and IASB, partly reflects the historically stronger interaction in US between the role of prudential regulators and loss allowances, which applies to India as well. However, IFRS 9 adopts a more principle-based approach towards estimation of expected credit losses. Nevertheless, since IFRS9 is a more widely accepted framework internationally, Reserve Bank proposes to adopt the ECL approach used in IFRS 9 for prescribing guidelines for loss provisioning by banks. 4.2. As can be seen, estimation of impairment losses under the expected credit loss approach is principle based and places significant responsibility on the management of the entity which is estimating and reporting such credit losses, for making such estimations. However, considering the vitality of adequate loan loss provisions from a prudential perspective, management discretion for making such estimates cannot be unfettered. Therefore, the proposed approach for introducing expected credit loss-based provisioning by banks would be to formulate principle-based guidelines supplemented by regulatory backstops wherever felt necessary. 4.3. In line with the approach under IFRS 9, the proposal will require banks to classify the financial instruments into three stages, modify the measurement and interest recognition of instruments to be based on effective interest rate, ascertain whether significant increase in credit risk has occurred on a reporting day as compared to initial recognition, and to measure and provide for the expected credit losses subject to the regulatory backstops. Reserve Bank will also adopt the principles laid out in BCBS (2015b) while formulating detailed guidelines for banks regarding adopting of expected credit loss approach for provisioning.

Scope and applicability 4.4. It is proposed to implement expected credit loss approach for loss provisioning to all scheduled commercial banks, excluding regional rural banks. The issue of extending the expected credit loss approach to co-operative banks was considered as well, but it was felt that the sophisticated expertise in credit risk management and complex modelling that would be required for estimating expected credit losses may be lacking in co-operative banks. On the other hand, NBFCs having net worth of Rs.250 crore or more are already required to estimate expected credit losses which may indicate that the assumption of inability on the part of co-operative banks to perform similar estimations may not be proper. One option may be to implement expected credit loss approach for loss provisioning to larger scheduled co-operative banks having asset size beyond a threshold.

4.5. It is proposed that the requirement for estimating impairment losses under the expected credit loss approach would apply to all financial assets held by banks having the following characteristics:

The “principal” referred to in the above requirements mean fair value of the financial asset at the initial recognition, and “interest” refers to consideration for time value of money, for the credit risk associated with the principal amount outstanding during a particular period of time and for other basic lending risks (such as liquidity risks) and costs (such as administrative costs, as well as a profit margin. If the time value of money is modified through event such as, for example, changes in interest rates through the life of the asset, such modifications should be tested to ensure that the above characteristics continue to apply. Also, sale of financial assets by banks to manage credit risk, credit concentration risk etc. are not inconsistent with the above characteristics. 4.6. Thus, it is proposed that the requirement for estimating impairment losses under the expected credit loss approach would apply to all loans and advances including irrevocable loan commitments (including sanctioned limits under revolving credit facilities), lease receivables, irrevocable financial guarantee contracts, and investments classified as held-to-maturity or available-for-sale (collectively termed as ‘applicable financial instruments’). For this purpose, the characteristic of being “irrevocable” should not be assessed solely based on existence of contractual clauses, but also on the basis of actual demonstration by the bank. Thus, for example, if a contract provides the ability to the bank to revoke an instrument but the bank practically refrains from doing so due to any reason, the asset should be adjudged as “irrevocable”.

Measurement of financial assets 4.7. The adoption of an expected credit loss approach to loss provisioning will require a fundamental modification to the way financial assets and income from the assets are currently measured and accounted for by banks. To elaborate, presently, a loan given by a bank is recorded in its balance sheet as the amount of outstanding principal amount. The interest income recognised from a loan asset is recorded as the contractual cash flows from the loan contract, which usually reflects the actual cash flows received by the bank. This approach does not have any consistency issues under the incurred loss approach as the loss provisions were also made on an actual basis. 4.8. However, under expected credit loss approach, a bank is required to estimate the credit losses through the life of a financial instrument and, as on the reporting date, measure the present value of such credit losses. Such measurement would therefore alter the expected cash flow stream over the life of the instrument while recording the effect of the same as on the reporting date using the discounted value of those losses. Such an approach that considers the time value aspect of cash flows (credit losses in this case) would be inconsistent with the current way of recognition of value of a loan as well as recognition of income from the loan on an actual contracted basis which ignores the time value of money aspect of the income streams and principal repayments over the life of the instrument. 4.9. Accordingly, IFRS 9 prescribes that financial assets having the following characteristics are to be measured at amortised cost:

4.10. Amortised cost is defined as the cost at which an asset is measured at initial recognition, adjusted for principal repayments, cumulative amortisation using the effective interest rate method. The interest income from financial assets measured at amortised cost are to be recognised by applying the effective interest rate on the value represented by the amortised cost. Effective Interest Rate 4.11. The concept of effective interest rate is vital to the implementation of expected credit loss-based loss provisioning for banks. This is because, the interest income from assets measured at amortised cost as well as the discounting of credit losses through the life of an asset for the purpose of calculation of expected credit losses are based on effective interest rate. 4.12. Effective interest rate is the rate that exactly discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the instrument to the gross carrying amount of an asset. For this purpose, the expected cash flows should be estimated by considering all contractual terms such as prepayment, extension, call and similar options but shall not consider expected credit losses, unless the instrument is credit impaired. The estimation also includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate, transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts. In respect of financial assets that are credit-impaired on initial recognition, IFRS 9 requires the use of credit-adjusted effective interest rate which discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the instrument to the amortised cost of a credit-impaired financial asset. 4.13. IFRS 9 gives detailed guidance on assessing whether any particular fees are an integral part of the effective interest rate. An example of fees that are integral part of the effective interest rate is origination fees received by an entity relating to the creation or acquisition of a financial asset, which may include compensation for evaluating the borrower’s financial condition; evaluating and recording guarantees, collateral and other security arrangements; negotiating the terms of the instrument; preparing and processing documents; and closing the transaction. An example of fees that are not integral part of the effective interest rate of a financial instrument are fees charged for servicing a loan. 4.14. When applying the effective interest method, an entity generally amortises any fees, points paid or received, transaction costs and other premiums or discounts that are included in the calculation of the effective interest rate over the expected life of the financial instrument. If an entity revises its estimates of payments or receipts (excluding modifications in contractual cash flows and changes in estimates of expected credit losses), it shall adjust the gross carrying amount of the financial asset to reflect actual and revised estimated contractual cash flows. 4.15. Transaction costs include fees and commission paid to agents, advisors, brokers and dealers, levies by regulatory agencies and security exchanges, and transfer taxes and duties. Transaction costs do not include debt premiums or discounts, financing costs or internal administrative or holding costs. 4.16. Since it is imperative that the measurement and recognition of interest income from assets are economically consistent with the expected credit loss approach for provisioning, it is proposed to require banks to measure applicable financial assets (mentioned at Paragraph 4.6 above) at amortised cost with interest income from such assets to be measured using the effective interest rate method. Credit Impairment 4.17. In line with the requirements under IFRS 9, it is proposed that at each reporting date, banks should measure the loss allowance for applicable financial instruments (mentioned at Paragraph 4.6 above) at an amount equal to the lifetime expected credit losses if the credit risk on that financial asset has increased significantly since initial recognition. On the other hand, if the credit risk on the financial asset has not increased significantly since initial recognition, banks should measure the loss allowance for that financial instrument at an amount equal to 12-month expected credit losses. Regardless of the above, loss allowances should always be measured at an amount equal to lifetime expected credit losses in respect of exposures in the nature of lease receivables or contractual guarantees. For this purpose, contractual guarantees mean guarantee contracts other than financial guarantee contracts (contracts that require the bank to make specified payments to reimburse the beneficiary for a loss it incurs because a specified debtor fails to make payment when due in accordance with the original or modified terms of a debt instrument). Thus, performance guarantees and bid-bond guarantees would be examples of contractual guarantees. For loan commitments and financial guarantee contracts, the date that the entity becomes a party to the irrevocable commitment shall be considered to be the date of initial recognition for the purposes of applying the impairment requirements. 4.18. IFRS 9 allows banks to assume that the credit risk on a financial instrument has not increased significantly since initial recognition if the financial instrument is determined to have low credit risk at the reporting date. The credit risk on a financial instrument is considered low for this purpose if the financial instrument has a low risk of default, the borrower has a strong capacity to meet its contractual cash flow obligations in the near term and adverse changes in economic and business conditions in the longer term may, but will not necessarily, reduce the ability of the borrower to fulfil its contractual cash flow obligations. Financial instruments are not considered to have low credit risk when they are regarded as having a low risk of loss simply because of the value of collateral and the financial instrument without that collateral would not be considered low credit risk. Financial instruments are also not considered to have low credit risk simply because they have a lower risk of default than the entity’s other financial instruments or relative to the credit risk of the jurisdiction within which an entity operates. 4.19. It is proposed to allow the use of the above practical expedient in respect of the following instruments: (a) SLR eligible investments; (b) direct claims on central government (i.e., excluding claims that arise from exposures that are guaranteed by the central government); and (c) exposures that are guaranteed by the central government, provided that the guarantee contains suitable clauses mandating invocation within a specified period (say, 30 days) from the event of default and payment of the guarantee amount will be received within a reasonable period (say, 60 days) after the invocation.

Determination of significant increase in credit risk 4.20. The assessment of significant increase in credit risk has to be made in comparison to the initial recognition of the financial asset. This is because at initiation, the banks are expected to factor in the ab initio credit risk associated with a borrower as a part of the credit assessment and the pricing of the loan may have been appropriately done. Thus, the credit risk at origination of an exposure is expected to be reflected in the initial effective interest rate applied to the instrument. 4.21. When making the assessment as to whether there is a significant increase in credit risk in applicable financial instruments since initial recognition, banks shall use the change in the risk of a default occurring over the expected life of the financial instrument instead of the change in the amount of expected credit losses. To make that assessment, banks shall compare the risk of a default occurring on the financial instrument as at the reporting date with the risk of a default occurring on the financial instrument as at the date of initial recognition and consider reasonable and supportable information, that is available without undue cost or effort, that is indicative of significant increases in credit risk since initial recognition. 4.22. While IFRS 9 does not define “default” in this context, a guidance is provided that an entity shall apply a default definition that is consistent with the definition used for internal credit risk management purposes for the relevant financial instrument and consider qualitative indicators (for example, financial covenants) when appropriate. There is also a rebuttable presumption that default does not occur later than when a financial asset is 90 days past due unless the bank has reasonable and supportable information to demonstrate that a more lagging default criterion is more appropriate. The definition of default used for these purposes has to be applied consistently to all financial instruments unless information becomes available that demonstrates that another default definition is more appropriate for a particular financial instrument. 4.23. The fact to be kept in mind is that significant increase in credit risk indicates a significant increase in the risk of a default and not the default itself. Typically, credit risk increases significantly before a financial instrument becomes past due or other lagging borrower-specific factors (for example, a modification or restructuring) are observed. 4.24. It can be seen that the above guidance on “default” has significant resemblance to the extant definition of a non-performing asset which uses the criteria of overdue for more than 90 days. The classification as non-performing asset is done at the counterparty level and not at the instrument level. This, in principle, allows borrowers to maintain an overdue cycle of up to 90 days for elongated periods of time leading to permanent time value losses for the banks. Hence, exposures to counterparty which are in a state of overdue with the bank continuously for a period of more than 90 days may need to be treated on par with assets classified as non-performing assets for the purpose of measuring expected credit losses. Such treatment will also cover exposures which may be overdue for more than 90 days but are not classified as non-performing assets by the bank because of existence of cover such as guarantees, liens on fixed deposits etc. despite having no recoveries from such exposures that also lead to time value losses for banks. Prudential credit risk management practices would require banks to invoke the guarantees / liens without much delay in respect of such exposures. 4.25. Apart from the above, IFRS 9 requires renegotiated and modified financial assets to be tested for significant increase in credit impairment by comparing the risk of default occurring at the reporting date (based on the modified contractual terms) with that at the initial recognition (based on the original, unmodified contractual terms). However, the extant prudential guidelines applicable to banks require restructured exposures (defined as exposures to borrowers in financial difficulties where concessions have been given by banks) as non-performing assets till a satisfactory performance is demonstrated by the borrower post such restructuring. Thus, the possible requirement of a restructuring would also indicate significant increase in credit risk while the exposures which are restructured will have to be treated as credit-impaired till satisfactory performance is demonstrated post such restructuring. 4.26. Many jurisdictions also consider exposures where the borrower has demonstrated unlikeliness to pay, as non-performing assets. Such assessment of “unlikeliness to pay” is generally based on various pre-determined indicators. Such a forward-looking classification for expected delinquency in the exposures would be consistent for the purpose of measurement of expected credit losses. 4.27. IFRS 9 gives detailed guidance regarding assessment of significant increase in credit risk, including information and possible factors to be considered. Apart from the requirement of having to make the assessment at an individual instrument level, IFRS 9 allows banks to group financial instruments on the basis of shared credit risk characteristics with the objective of facilitating an analysis that is designed to enable significant increases in credit risk to be identified on a timely basis. Detailed guidance on assessment of significant increase in credit risk has also been provided by BCBS1. 4.28. Considering all of the above, it is proposed that banks shall test applicable financial instruments for significant increases in credit risk since initial recognition, assessed as the increase in risk of a default occurring, on each reporting date. 4.29. For the purpose of such determination, the definition of default is proposed to be as below: • The counterparty is classified as a non-performing asset under the extant guidelines of RBI; • The exposure to the counterparty has been restructured by the bank and such exposure continues to be in the ‘monitoring period’; or • The bank considers that the borrower is unlikely to pay its existing debt. For this purpose, a non-exhaustive list of indicators of unlikeliness to pay include:-

4.30. Further, since the significant increase in credit risk implies increase in probability of default and default in any financial instrument is treated as a default by the counterparty, evidence of significant increase in credit risk in respect of any financial instrument would imply significant increase in credit risk associated with the counterparty who has issued such instrument. One could argue, therefore, that the assessment of significant increase in credit risk should be at the level of each counterparty and not at the instrument level. However, the same would be more conservative as compared to IFRS9.

4.31. One subtle aspect in this regard relates to the timing of an exposure being adjudged as more than 90 days overdue. Banks in India, presently follow a first-in-first-out approach while matching payments by borrowers against due dates as per the loan contract, which inherently implies a time value loss for the banks even as the account continues to be classified as standard. In view of the resolution paradigm put in place over the recent past, it may be argued that such time value losses for the lenders essentially reflect continuing stress in the borrower accounts, and hence need to be treated as such. However, this would be a structural change from the extant practice being followed by banks.

4.32. Banks are expected to put in place adequate mechanisms, controls and governance systems that are capable of handling and systematically assessing the information that will be required to make determination of whether significant increase in credit risk has taken place since initial recognition. Credit risk analysis is a multifactor and holistic analysis and whether a specific factor is relevant, and its weight compared to other factors, will depend on the type of product, characteristics of the financial instruments and the borrower as well as the geographical region. The timely determination of whether there has been a “significant” increase in credit risk subsequent to the initial recognition of a lending exposure is crucial and banks must have processes in place that enable the same. 4.33. The range of information that will need to be considered in making this determination is wide. In broad terms, it will include information on macroeconomic conditions, and the economic sector and geographical region relevant to a particular borrower or a group of borrowers with shared credit risk characteristics, in addition to borrower-specific strategic, operational and other characteristics. A critical feature is the required consideration of all reasonable and supportable forward-looking information in addition to information about current conditions and historical data. It is also important that banks’ analyses take into account the fact that the determinants of credit losses very often begin to deteriorate a considerable time (months or, in some cases, years) before any objective evidence of delinquency appears in the lending exposures affected. 4.34. IFRS 9 has provided an indicative list of 16 classes of indicators that may be used by banks in developing their approach to determining a significant increase in credit risk, with an added guidance that the indicator should not be used as a checklist. BCBS (2015b) has endorsed the same and has emphasised that particular consideration should be given to the following in assessing a significant increase in credit risk:

4.35. It is proposed to issue detailed expectations on the factors and information that should be considered by banks while making determination of credit risk based on the guidance provided in IFRS 9 and principles laid out by BCBS, as a part of the proposed draft guidelines on loss provisioning based on expected credit loss approach. 4.36. There is a rebuttable presumption under IFRS 9 that the credit risk on a financial asset has increased significantly since initial recognition when contractual payments are more than 30 days past due. Regardless, it is proposed that, if a counterparty is overdue for more than 60 days, banks have to treat as significant increase in credit risk as having occurred in respect of such counterparty and make lifetime expected credit losses in respect of such counterparty. 4.37. Additionally, stressed exposures classified under “Watch-list” or equivalent classification for stressed exposures, as reported to the Board or Board-level Committees based on Board approved policies of the banks should also be assessed as exposures where significant increase in credit risk has been evidenced since initial recognition.

Measurement of Expected Credit Losses 4.38. In line with the requirement under IFRS 9, banks shall measure expected credit losses of an applicable financial instrument in a way that reflects:

The expected credit losses are, thus, to be measured as a probability-weighted estimate of credit losses (i.e., the present value of all cash shortfalls) over the expected life of the financial instrument. 4.39. For undrawn loan commitments, a credit loss is computed as the present value of the difference between:

4.40. A bank’s estimate of expected credit losses on loan commitments shall be consistent with its expectations of drawdowns on that loan commitment:

4.41. For financial guarantee contracts, cash shortfalls are the expected payments to reimburse the beneficiary for a credit loss that it incurs less any amounts that the bank expects to receive from the beneficiary, the debtor or any other party. 4.42. For a financial asset that is credit-impaired at the reporting date, a bank shall measure the expected credit losses as the difference between the asset’s gross carrying amount and the present value of estimated future cash flows discounted at the financial asset’s original effective interest rate. Any adjustment is recognised in profit or loss as an impairment gain or loss. 4.43. The maximum period over which expected credit losses should be measured is the maximum contractual period over which the entity is exposed to credit risk. For loan commitments and financial guarantee contracts, this is be the maximum contractual period over which an entity has a present contractual obligation to extend credit. In respect of revolving credit facilities, when determining the period over which the bank is expected to be exposed to credit risk, but for which expected credit losses would not be mitigated by the bank’s normal credit risk management actions, the bank should consider factors such as historical information and experience about:

4.44. IFRS 9 does not prescribe any methodologies for estimating expected credit losses. The requirement is for the management of a bank to use all reasonable and available information to estimate reasonable future scenarios that would lead to credit losses and then arrive at the discounted value of credit losses on a probability-weighted basis. Thus, the measurement of expected credit losses is dependent upon the experienced judgment of the management of the bank about the credit risk of lending exposures. Given the requirement of a probability-weighted assessment of credit losses for measurement of expected credit losses, the requirement of a connecting model to link account information, macroeconomic scenarios, and credit risk satellite models (to estimate elements such as probability of default, loss given default and exposure at default) can be inferred. The link between expected losses and macroeconomic scenarios for measurement of expected credit losses is comparable to such relationships assumed in credit risk stress testing. Hence, in principle, management of banks are free to utilise standard techniques used for macroeconomic scenario analysis as well as credit risk toolkit to estimate PD, LGD and EAD to arrive at the estimates of expected credit losses. 4.45. Banks are free to adopt different credit risk models to estimate expected credit losses in respect of various classes of financial instruments depending upon the suitability of such modelling approaches and availability of requisite data in respect of the class of financial instruments. Thus, the credit risk suite of a bank for estimating expected credit losses in its portfolio of applicable financial instruments may include a variety of approaches spanning from simpler models such as loss-rate methods and vintage analysis to more complex approaches such as generalised linear models, survival modelling approaches, regression techniques, machine learning techniques etc. However, it is expected that the rationale behind adopting a particular model to a particular class of financial instrument should be properly justified and documented by the banks. 4.46. BCBS (2015b) recommends that a bank’s allowance methodologies should clearly document the definitions of key terms related to the assessment and measurement of expected credit losses (such as loss and migration rates, loss events and default) and that a bank should adopt and adhere to written policies and procedures detailing the credit risk systems and controls used in its credit risk methodologies and the separate roles and responsibilities of the bank’s board and senior management. BCBS also provides an indicative and non-exhaustive list of expectations of robust and sound methodologies for assessing credit risk and measuring the level of allowances. It is expected that such methodologies generally will:

4.47. BCBS (2015b) also stresses the importance of validation of models used for assessing expected credit losses and recommends that a sound model validation framework should include, but not be limited to, the following elements: • Clear roles and responsibilities for model validation with adequate independence and competence. Model validation should be performed independently of the model development process and by staff with the necessary experience and expertise. Model validation involves ensuring that the models are suitable for their proposed usage, at the outset and on an ongoing basis. The findings and outcomes of model validation should be reported in a prompt and timely manner to the appropriate level of authority. • An appropriate model validation scope and methodology include a systematic process of evaluating the model’s robustness, consistency and accuracy as well as its continued relevance to the underlying portfolio. An effective model validation process should also enable potential limitations of a model to be identified and addressed on a timely basis. The scope for validation should include a review of model inputs, model design and model outputs/performance.

• Comprehensive documentation of the model validation framework and process. This includes documenting the validation procedures performed, any changes in validation methodology and tools, the range of data used, validation results and any remedial actions taken where necessary. Banks should ensure that the documentation is regularly reviewed and updated. • A review of the model validation process by independent parties (eg internal or external parties) to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the model validation process and the independence of the model validation process from the development process. The findings of the review should be reported in a prompt and timely manner to the appropriate level of authority (eg senior management, audit committee). 4.48. As evident from the above discussion, it is apparent that prescribing a uniform methodology for all banks towards measuring expected credit losses will not be desirable since such assessment is intricately linked to the credit risk management practices and data availability at each bank. Therefore, it is proposed that each bank will be permitted to design and implement its own models for measuring expected credit losses for the purpose of estimating loss provisions. As a part of the proposed draft guidelines on loss provisioning based on expected credit loss approach, RBI will issue detailed guidance based on the principles discussed above that will be required to be considered while designing the credit risk models that are used for assessing and measuring expected credit losses. The expected credit loss models adopted by the banks should be subject to rigorous validation. Where a bank has outsourced its validation function to an external party, the bank remains responsible for the effectiveness of all model validation work and should ensure that the work done by the external party meets the elements of a sound model validation framework on an ongoing basis. 4.49. Considering the significant variability that coukd be introduced into the lending system by having such disparate models for assessment of credit losses, the following mitigants are proposed:

4.50. An additional aspect is regarding restructured loans which are a sub-category of renegotiated / modified financial assets. IFRS 9 requires renegotiated and modified financial assets to be tested for significant increase in credit impairment by comparing the risk of default occurring at the reporting date (based on the modified contractual terms) with that at the initial recognition (based on the original, unmodified contractual terms), without making any distinction between modifications that are a result of commercial negotiations between banks and their counterparties and concessions to counterparties in financial difficulties which are restructurings. However, this would be inconsistent with the definition of “default” proposed in this paper, which includes assets that have been restructured – the restructured assets are already credit impaired and hence, a test for significant increase in credit risk would be redundant. IFRS 9 permits revised effective interest rates in respect of renegotiated / modified financial assets under the assumption that such renegotiation / modification results in creation of a new asset. However, since restructuring is an act through which a bank is trying to protect its original exposure and does not result in creation of a new exposure, perhaps original effective interest rate could continue to apply for restructured loans. In such a scenario, banks should test renegotiated and modified financial assets other than restructured assets for significant increase in credit impairment by comparing the risk of default occurring at the reporting date (based on the modified contractual terms) with that at the initial recognition (based on the original, unmodified contractual terms). Also, the effective interest rate for restructured asset could continue to be the original effective interest rate as per the estimations prior to the restructuring.

Classification of Applicable Financial Assets and Income Recognition 4.51. On the basis of credit risk as compared to the initial recognition, banks would be required to classify applicable financial assets into three stages:

4.52. As per the approach under IFRS 9, the interest income from Stage 1 and Stage 2 assets will be required to be calculated on the basis of gross carrying amount of the asset, i.e., the interest income is calculated by applying the effective interest rate to the carrying amount of the financial asset without any adjustments for expected credit losses. It is proposed to adopt the same approach for banks in respect of their assets classified under Stage 1 and Stage 2. 4.53. Under IFRS 9, interest income is accrued even in case of Stage 3 assets. The only difference is that interest income will be calculated on the basis of net carrying amount of the financial asset, i.e., carrying amount of the financial asset after adjusting for expected credit losses. This would be a major departure from the current interest income recognition permitted for asset classified as non-performing assets wherein income is permitted to be recognised only on an actual basis, i.e., only when the cash flow is actually received and not merely accrued. It is felt that permitting banks to accrue interest on Stage 3 assets, which are essentially credit impaired may not be prudent considering the significant uncertainty in the actual realisation of cash flows from such assets. Therefore, interest recognition in respect of Stage 3 assets should be on the basis of actual receipt of cash flows and not on an accrual basis. This approach is consistent with the approach in US GAAP which permits banks to place financial assets on nonaccrual basis if the cash flows cannot be reliably estimated.

4.54. IFRS 9 specifies that if a bank has measured the loss allowance for an applicable financial instrument at an amount equal to lifetime expected credit losses in the previous reporting period, but determines at the current reporting date that a significant increase in credit risk since initial recognition no longer applies, the bank should measure the loss allowance at an amount equal to 12-month expected credit losses at the current reporting date. In principle, this would mean that an asset shall be upgraded from Stage 3 when the irregularity / deficiency which led to the account being classified as defaulted is fully rectified on a sustainable basis. However, a transient rectification of the irregularity/deficiency near about the balance sheet date may not be sufficiently indicative of the removal of stress, unless there is satisfactory evidence to support that the rectification of the irregularity/deficiency is sustainable and the inherent credit weakness has been substantially mitigated. In order to address this concern, one option may be to stipulate that an asset in Stage 3 shall not directly be brought to Stage 1 even after the irregularities are rectified and that the banks shall keep a Stage 3 asset in Stage 2 for minimum six months after all the irregularities are rectified, before the same is brought to Stage 1. While more conservative, this cooling period may facilitate a more realistic assessment of the “unlikeliness to pay” criteria.

Prudential floor for loss provisions 4.55. As stated earlier, it is proposed that credit loss estimates arrived at by the banks using their respective models will be subject to a prudential floor prescribed by RBI as a regulatory backstop. Under the extant incurred loss approach also, RBI has prescribed regulatory minima for loan loss provisions to be maintained by banks, depending upon the asset classification. Since the current regulatory floors for loss provisions have been prescribed for an incurred loss approach, they would be inadequate as prudential floors under an expected credit loss approach. This is because the prudential floors will have to reckon the likely losses that may arise throughout the life time of the applicable financial instrument. 4.56. One consideration that could guide RBI in the proposal for prudential floors for loss provisions is that starting floors for Stage 2 or 3 assets should be agnostic to the reasons for classifying assets as Stage 2 or 3 assets. Presently, such an agnostic approach does not exist for the provisioning requirement in the case of exposures classified as non-performing loans due to being overdue for more than 90 days and exposures classified as non-performing loans due to having been restructured. In the former case, under the assumption of a fully secured loan, the provisioning requirement will be 15 per cent. The regulatory preference however is for a resolution of the impaired loan. In the case of a resolution involving restructuring, conversion of a portion of the impaired debt into alternative instruments such as equity in the borrower would lead to higher provisioning requirement for the banks. For example, if 25 per cent of an impaired loan is converted into equity, the provisioning requirement post restructuring may go up to 36.25 per cent. Thus, the current levels of prudential floors for loss provisions appear to incentivise inaction upon impairment over resolution, at least in the short term. 4.57. It is proposed that the expected credit loss measured in respect of an asset classified as Stage 1 as well as Stage 2 or 3 will be subject to prudential floors to be calibrated based on a comprehensive data analysis, rather than merely re-prescribing extant norms. The prudential floors will be subject to a step-up prescription depending upon the time that a financial instrument spends as a Stage 2 or 3 asset. Actual specifications shall be included in the Draft Guidance. 4.58. Higher provisioning requirements and a faster write-off schedule (or equivalently, a faster schedule to maintain 100 per cent provisions against Stage 3 assets) would prevent the accumulation of non-performing assets by incentivising resolution efforts by banks. This point is illustrated by the relatively tougher write-off requirements in US as compared to Europe, which has been attributed to reducing the stock of non-performing loans carried by US banks as compared to European banks. This aspect is proposed to be considered as well while proposing the level and schedule of the prudential floors for Stage 2 or 3 assets. 4.59. At the same time, it is recognised that the credit risk associated with a restructured asset that is in the monitoring period and performing satisfactorily is relatively lower than that of a Stage 3 asset that has been classified so due to non-payment of amounts due and payable. Considering the same, restructured assets that are in the monitoring period and are performing satisfactorily will be subject to a fixed prudential floor for loss provisioning regardless of the time spent as a Stage 3 asset. Once the asset exits the monitoring period successfully and enters the remaining specified period, the asset can be classified as Stage 2. 4.60. In terms of the extant provisioning norms for banks, standard asset provisions are treated as General Provisions while the provisions required to be maintained in the case of NPAs, including any additional provisions maintained at the discretion of banks, are treated as specific provisions. As regards the approach for ECL provisioning for banks, BCBS (2017a) provides for retention of the current regulatory treatment of provisions for an interim period during which jurisdictions would extend their existing approaches to categorising provisions as General Provisions or Specific Provisions to provisions calculated under the applicable ECL accounting mode. BCBS also notes that extending their existing approaches would not preclude jurisdictions from categorising some ECL provisions as General Provisions even where historically all provisions for incurred losses have been treated as Specific Provisions. Accordingly, while the approach for Stage 1 and Stage 3 assets of treating the provisions as general and specific, respectively may be clear, for stage 2 assets, there may be two options:

4.61. The adequacy of the loan loss provisions maintained by the banks based on their respective ECL models will be subject to supervisory assessment of the RBI even if regulatory floors have been prescribed. If the supervisory assessment leads to a conclusion that the required loan loss provisions are higher than those suggested by the ECL models used by the banks and the prudential floor, supervisors shall require the banks to maintain the assessed provisioning requirement. Such direction by the supervisors will be binding on the banking companies. 4.62. Another aspect that needs to be considered is that the extant instructions on provisioning norms make a distinction between secured portion and unsecured portion of an impaired loan. Unsecured exposure is presently defined as an exposure where the realisable value of the security, as assessed by the bank/approved valuers/Reserve Bank’s inspecting officers, is not more than 10 per cent, ab-initio, of the outstanding exposure. This definition of secured / unsecured exposures may overstate the availability of security cover, especially since enforcement of security interest as a recovery measure in respect of impaired loans are likely to be fire-sales. Therefore, such approaches reduce the risk mitigation available through provisions. At the same time, since the realisable value of the underlying collateral is also factored in while computing the loan loss provisions under the ECL approach, it may also be sufficient to just provide guidance regarding valuation of collateral under the ECL model. Even in this case, some definition for a secured exposure may have to be loaded into the prudential floor calibrations as the availability of collateral cannot be ignored for the prudential floors and rather would have to be factored in as accurately as possible. Further, as per the extant IRAC norms, in respect of non-performing assets, the collateral charged in favour of the bank should get valued once in three years by valuers appointed as per the guidelines approved by the Board of Directors of the bank. This runs the risk of the valuations not keeping up with the market trends although there is no prohibition for a bank to conduct valuations more frequently. 4.63. To address the above issues, the following approaches could be considered for the purpose of arriving at the prudential floors, without interfering with the discretion available to banks in their model design: