|

| |

| |

Committee on the Global Financial System |

| |

CGFS Papers

No 33

Capital flows and emerging market economies |

| |

Report submitted by a Working Group established by the Committee on the Global Financial System |

| |

This Working Group was chaired by Rakesh Mohan of the Reserve Bank of India |

| |

January 2009 |

| |

JEL Classification: F21, F32, F36, G21, G23, G28 |

| |

|

| |

Copies of publications are available from:

Bank for International Settlements

Press & Communications

CH 4002 Basel, Switzerland |

| |

E mail: publications@bis.org

Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100

This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). |

| |

© Bank for International Settlements 2009. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited. |

| |

ISBN 92-9131-786-1 (print)

ISBN 92-9197-786-1 (online) |

| |

| |

| |

A. Introduction

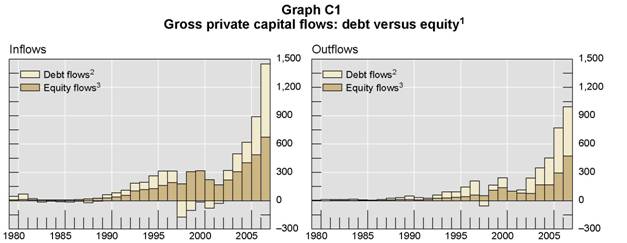

This Report reviews the growing integration of the major emerging market economies

(EMEs) into global financial markets. Greater financial integration is evident from the

sustained rise in both gross capital inflows (ie non-resident purchases of domestic assets)

and outflows (ie resident purchases of foreign assets) to and from the EMEs. Although the

structure of flows has become more stable, capital flows continue to be very volatile and this

has major macroeconomic implications for recipient countries. The size and the structure of

inflows are heavily conditioned by, and exert a major influence on, the state of development

of local financial markets.

The benefits and costs of capital market integration have been a controversial topic of debate

among academics and among policymakers. In principle, access to foreign savings helps a

country to lift future income streams (by undertaking investments whose prospective returns

exceed the cost of finance) and to better smooth consumption over time. In practice,

however, capital inflows – in terms of sheer size, volatility and form – have very often put

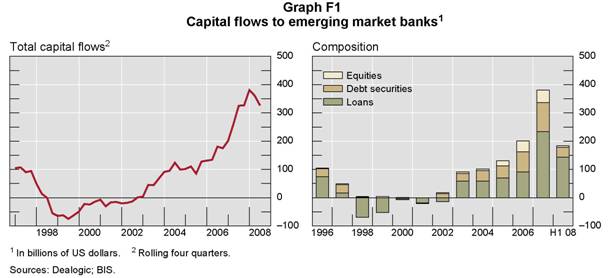

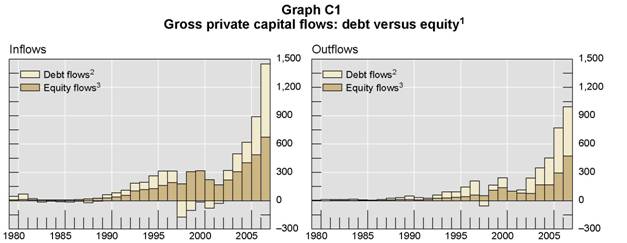

emerging market countries in major difficulty. During 2006 and 2007, the very rapid rise of

gross private capital inflows into the EMEs (now over $1 trillion a year, compared with the

previous peak of $300 billion in 1996) caused considerable strains in some countries. In

contrast, the current year (2008) to date has witnessed large equity outflows by portfolio

investors. Such large swings, over a very short period of time, complicate the conduct of

monetary policy and liquidity management in the EMEs. And many feel that the financial

stability risks have increased or at least become harder to monitor.

The next section briefly reviews the extensive academic debate on this topic. This debate,

somewhat inconclusive on the surface, yields several valuable insights on closer inspection.

The final section of this chapter outlines the plan of the Report.

The macroeconomic effects of capital account liberalisation

Economists have long debated the relationship between capital account liberalisation and

economic performance. One theoretical approach, forcefully advocated in the mid-1990s,

follows the first-best prescription of the neoclassical model (assuming, in particular, perfect

capital markets): allowing the free flow of capital across borders would lead to a more

efficient allocation of resources and be welfare-enhancing for both borrowers and lenders, in

a fashion similar to the liberalisation of trade.

An alternative view took a second-best perspective: that removing one distortion –

restrictions on capital movements – in the presence of other distortions that often exist in

emerging markets may not necessarily enhance welfare (eg Newbery and Stiglitz (1984);

and Stiglitz (2008)). This alternative view gained particular relevance after the onset of the

Asian crisis. This crisis focused attention on how incomplete or malfunctioning domestic

financial markets in recipient countries and poor risk management in capital-exporting

countries could undermine the case for capital account liberalisation.1

In the light of the debate on the macroeconomic and growth effects of capital account

liberalisation, a large empirical literature has emerged during the past decade in an attempt

to settle the issue. The Report therefore begins with a brief survey of this empirical evidence.

1 The first-best prescription is, of course, that policies can address those market failures directly – and indeed

did so after the Asian crisis.

Cross-country studies

The cross-country empirical literature on capital account liberalisation has been extensively

surveyed by several authors – Eichengreen (2001); Edison, Klein, Ricci and Sløk (2004);

Prasad, Rogoff, Wei and Kose (2003); Henry (2007); and Reinhart and Reinhart (2008). This

section draws out some key themes of selected studies.

A majority of cross-country studies on the growth effects of capital account liberalisation

follow a similar methodological approach, although some of them examine developed and

developing countries together, while others focus only on developing countries. Typically,

these studies use a proxy to measure capital account openness (eg the number of years a

country has had an open capital account), and regress a measure of economic performance

(eg average economic growth) on this proxy. Very often, the proxy measure for capital

account liberalisation (but certainly not the only one) is constructed as a binary indicator

of an “open” or “closed” capital account using information from yearly issues of the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER).

Despite the numerous cross-country attempts to analyse the effects of capital account

liberalisation, there appears to be only limited evidence that supports the notion that

liberalisation enhances growth. This failure to find robust evidence has been interpreted by

the critics of capital account liberalisation to mean that liberalisation does not promote

growth, as the proponents of the alternative view would argue. For example, one of the earliest (and most widely cited) papers about the macroeconomic effects of capital account liberalisation is Rodrik (1998). He uses data for about 100 countries (both developed and developing) between 1975 and 1995 and regresses growth of income per capita on the IMF indicator-based binary variable mentioned above. He finds no correlation between liberalisation and per capita growth.

However, some argue that this result may be due partly to the crudeness of the binary variable that proxies for liberalisation. Quinn (1997) constructs a proxy that measures not only the presence but also the intensity of a liberalised capital account and finds that, for a sample of 66 countries between 1960 and 1989, there is a positive correlation between the change in his indicator and growth; however, Quinn uses relatively fewer low-income countries than Rodrik, which may be one source of the different results. Edwards (2001) uses Quinn’s measure and finds that liberalisation enhances growth in high-income countries but decreases it in low-income ones. This result suggests that perhaps the growth effects of capital account liberalisation are contingent on a country’s level of development.

Contingent effects and sequencing

Given the general inability to find unconditional positive growth effects of liberalisation, many studies have attempted to determine whether such effects are dependent on other conditions and policies that accompany liberalisation (“contingent effects”). For example, Kraay (1998) tests whether the growth effects of liberalisation are contingent on the quality of policy and institutions but finds no evidence, regardless of the use of the IMF-based binary proxy of Quinn’s indicator. In contrast, Klein (2005) finds evidence of a non-monotonic interaction between institutional quality and the effect of capital account openness on growth. Using panel data for 71 countries, a measure of capital account openness similar to the approach in Rodrik (1998), and the average of five variables to proxy for institutional quality (bureaucratic quality, control of corruption in government, risks of expropriation, repudiation of government contracts, and rule of law), he finds that the effect of capital account openness on economic growth is greatest for countries with better, but not the best, institutional quality.

Arteta, Eichengreen and Wyplosz (2003) ask whether the positive effect (if any) of capital account liberalisation on growth is limited to countries in a more advanced stage of financial and institutional development (where distortions that may result in a perverse effect of liberalisation are presumably low). They also examine whether it is limited to countries that have been deemed to have followed a proper sequencing of reforms (that is, where macroeconomic imbalances have been first eliminated and a high degree of trade openness has been achieved). They find only weak evidence that the effects of capital account liberalisation vary with financial and institutional development. On the other hand, they do find evidence that the positive effects of capital account openness on growth are contingent on the absence of macroeconomic imbalances, but not on openness to trade. In the presence of macroeconomic imbalances, capital account liberalisation is as likely to hurt as to help. This suggests that the sequencing of reforms shapes the effects of capital account liberalisation, which underlines the need for caution in approaching liberalisation in practice.

However, such cross-country studies that document conditional or unconditional positive effects of capital account liberalisation on aggregate economic growth cannot be considered representative of the considerable literature on this issue. In a survey of 10 studies on the subject, Edison et al (2004) find that only three uncover an unambiguous positive effect of liberalisation on growth. Similarly, Prasad et al (2003) survey 14 studies and find that only three of those studies identify a statistically significant positive relationship between capital account liberalisation and economic growth. This is consistent with the observation by Eichengreen (2001) that the literature finds, at best, ambiguous evidence that liberalisation has any impact on growth.

Reconciling the evidence

If theory predicts a positive effect of capital account liberalisation on growth for an emerging market economy, why have empirical studies been unable to unequivocally establish this link? Henry (2007) offers two compelling explanations. First, the IMF’s AREAER-based measure of capital account liberalisation used in several studies is fraught with imperfections. Second, the common econometric specification and data used in previous studies test for permanent effects of capital account liberalisation on growth, while theory only suggests a temporary growth effect and a permanent level effect.

A line of research that possibly circumvents imperfections in the IMF’s AREAER-based measure of capital account liberalisation does so by focusing on what happens before and after episodes of capital account liberalisation. In this literature, a capital account liberalisation event is assumed to occur when a country changes regulation to allow foreigners to purchase shares on the domestic stock market or when there is a significant increase in the S&P/International Finance Corporation’s Investability Index for the country. Studies based on this approach have been more successful in documenting a positive, but temporary, effect of capital account on investment and growth. In particular, countries appear to derive substantial benefits from opening their equity markets to foreigners (see eg Henry (2007) for a survey).2 Henry (2003) documents the channels – consistent with prediction by theory – through which the effect of capital account liberalisation operates. In the years following capital account liberalisation, the cost of capital declines. The lower cost of capital in turn boosts investment and, hence, economic growth.3

The relative success of event studies in documenting a positive effect could be attributed to the fact that these studies generally focus on a shorter time window around the date of the capital account liberalisation. As pointed out by Henry, theory suggests that the growth effect of capital account liberalisation should be temporary, and that level effects should be permanent. Estimating the effect with a sample that covers a long time period or a cross section of countries, as is the case in many of the studies, would fail to find a significant positive growth effect even when there is one because it is implicitly testing for a permanent growth effect, which is not a prediction of the neoclassical growth models. If this hypothesis is indeed correct, it would suggest that the long-run effect of capital account liberalisation on the emerging market economies should be recast in terms of its effect on levels of aggregate economic variables and on welfare.

2 Coulibaly (2009) uses an event study based on imposition and removal of an economic embargo on South

Africa. He documents a negative effect of the embargo on economic growth and a positive effect of the

removal of the embargo on growth.

3 Additional references on the effect of capital account liberalisation on the cost of capital include Kim and

Singal (2000) and Martell and Stulz (2003).

Collateral benefits

Despite the progress made over the last decade in understanding the effect of capital account liberalisation on economic activity in emerging market countries, some unresolved issues remain. In studies – mostly event studies – that have found positive effects of capital account liberalisation on economic growth, the magnitude of the output growth effect implied by the observed boost in investment and the capital stock falls short of the actual growth rates observed in the periods following capital account liberalisation (see Henry (2003) for a detailed discussion). In other words, following capital account liberalisation, output grows at a rate faster than can be justified by the increase in the capital stock given the share of capital in production. If the observed growth in output following capital account liberalisation cannot be fully accounted for by the liberalisation, what other forces are at play when the capital account opens?

A tentative answer to this puzzle lies in the growing literature on the “collateral benefits” of capital account liberalisation. According to this literature, the benefits of capital account liberalisation do not just operate through the cost of capital and investment. Opening capital accounts serves as an important catalyst for a number of indirect benefits. These indirect benefits include development of the domestic financial markets, improvements to local institutions, and better macroeconomic policies (Prasad et al (2006)). It is also conceivable that the presence of knowledgeable foreign investors increases competition and forces local market participants to become more efficient. The better governance, competition, and the enhanced efficiency that ensues could possibly explain the additional growth observed in the years after a country opens its capital account. Indeed, studies have documented an important increase in total factor productivity following the liberalisation of capital accounts, which could account for the additional increase in output growth. In a more recent study by Prasad et al (2008), the authors find that de jure capital account openness has a robust positive effect on total factor productivity growth, but the effect was less clear for the de facto financial integration.

However, more research is needed to establish a causal link between capital account liberalisation and total factor productivity growth. Empirical testing of the collateral benefits hypothesis is complicated by the wrinkle that proponents of this view also argue that, for these collateral benefits to kick in, a minimal degree of financial development needs to be in place already, which they call the required “thresholds”. This introduces considerable non-linearities in the relationships, where the relationships between capital account liberalisation, growth, and the variables that could be considered the outcomes of collateral benefits change at levels that are uncertain. Thus, while the hypothesis of collateral benefits is intriguing, it is in its infancy, and more research in this area is needed to evaluate its merits. However, it does reiterate that appropriate sequencing of policy changes may be very important; and the ideas of collateral benefits threshold effects are also related to the earlier literature on contingent effects. In sequencing policies of capital account liberalisation, the possible increase in vulnerability arising from volatility in cross-border flows has to be weighed against the potential benefits.4

An outline of the Report

The aim of this Report is to shed further light on these issues by examining what has happened in the major emerging market economies over the past decade. The CGFS asked this Working Group to pay particular attention to the implications for the financial system (see the mandate prepared in May 2007 in Annex 1). In preparing this, the Working Group has had considerable assistance from central banks, from academics and from representatives of the financial industry (see Annex 3).

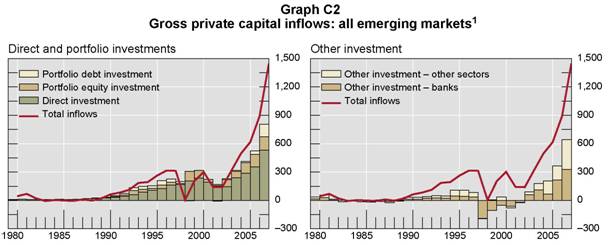

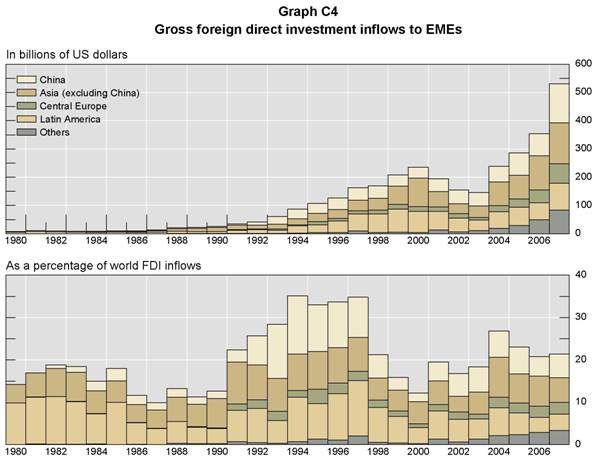

Chapter B summarises the main trends of aggregate capital flows in the 2000s. It analyses the macroeconomic factors that have determined the volume and the composition of capital flows. Weak or unstable macroeconomic conditions in capital-importing countries can lead to destabilising forms of capital flow. Macroeconomic conditions in capital-exporting countries can also exert an influence.

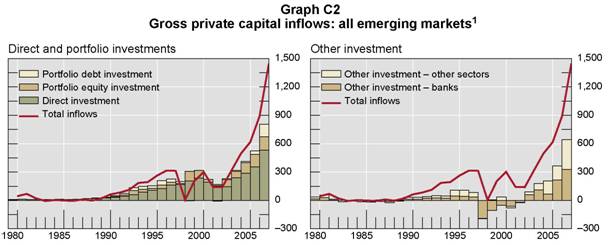

Chapter C reviews how the composition of capital flows – mainly foreign direct investment, portfolio investments (equity and debt securities) and flows intermediated through banks – has changed over time. The composition of flows does have a significant bearing on monetary policy dilemma. It also has major implications for the sustainability of flows, for the nature of risk-sharing and for financial stability more generally.

An unusual feature of the most recent period of heavy capital inflows to the large EMEs is that they have not been “needed” to finance current account deficits. In fact, the EMEs as a group have had a large and growing current account surplus. Several countries have resisted currency appreciation. Only part of the foreign currency inflow (that is, from the current account surplus plus private capital inflows) has been recycled by institutional and other private sector investors from the emerging markets (private capital outflows). The monetary authorities have in effect done the bulk of the recycling (that is, via increased foreign exchange reserves). This has had major monetary and financial implications that are analysed in Chapter D.

Chapter E explores the various linkages between capital flows and the development of local financial markets. It also explores how the correlations between local and international financial markets have changed in recent years. There is clear evidence that domestic financial markets in most EMEs have become both broader and deeper than a decade ago.

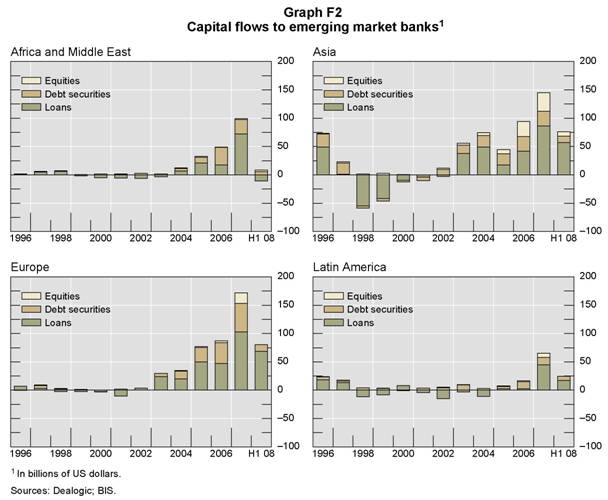

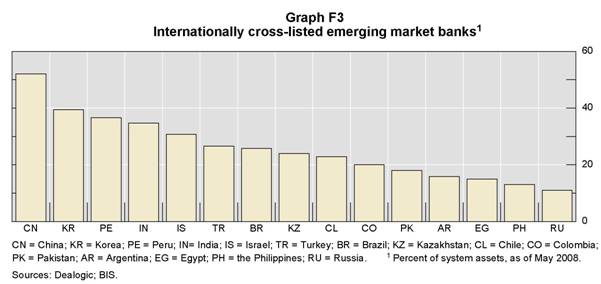

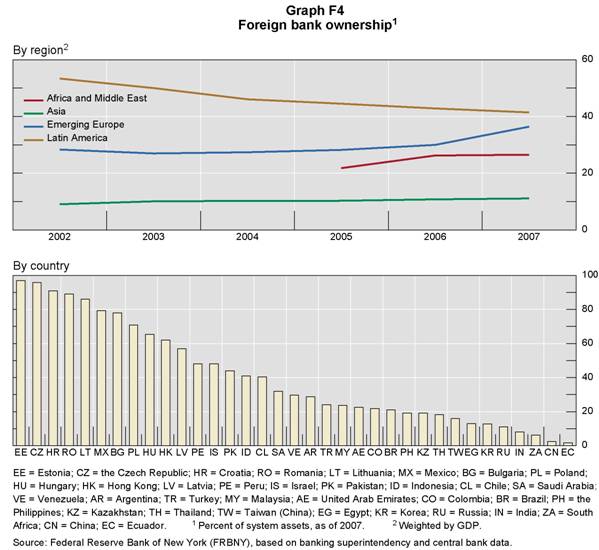

The increased size of the local operations of international banks in EMEs is examined in Chapter F. Foreign banks have often spurned a shift in bank lending from the commercial sector to households. The macroeconomic and financial implications of such lending are quite different from those of the direct cross-border lending in foreign currencies that characterised earlier periods. In some cases, the growth and structure of international bank lending has given rise to some financial stability returns.

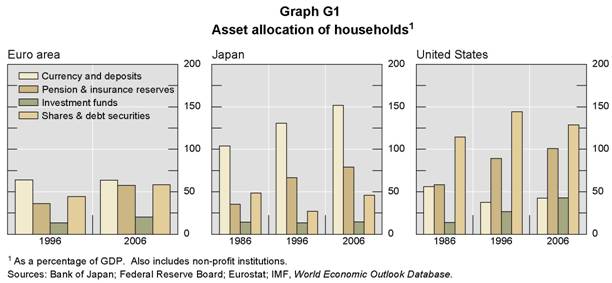

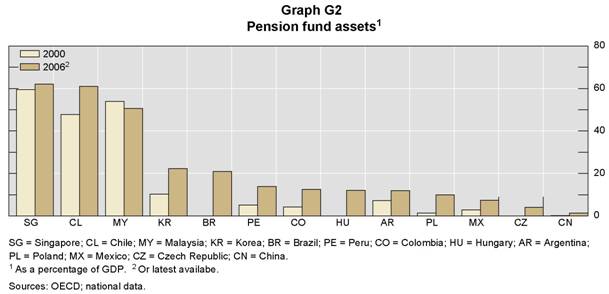

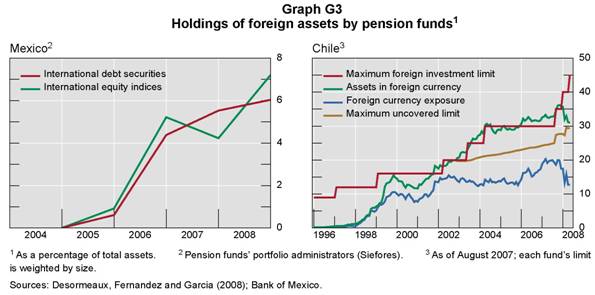

Chapter G documents the large increase in capital outflows from EMEs over the past decade. The marked home bias of local investors is weakening. Households in the EMEs have begun to increase the share of foreign assets in their portfolios, directly and indirectly via institutional investors.

4 According to Reinhart and Reinhart (2008), capital inflow “bonanzas” tend to be associated with economic crisis (debt defaults, and banking, inflation and currency crashes). Similarly, Calvo (2008) concluded that the probability of a “sudden stop” of capital flows initially increases in the early stages of financial integration but then gradually decreases, and is virtually nil at high levels of integration. Emerging markets largely stand in a grey area between developed and other developing countries, where the probability of a sudden stop is the highest, suggesting that financial integration can be risky when not accompanied by the development of institutions that will support the use of more sophisticated and credible financial instruments.

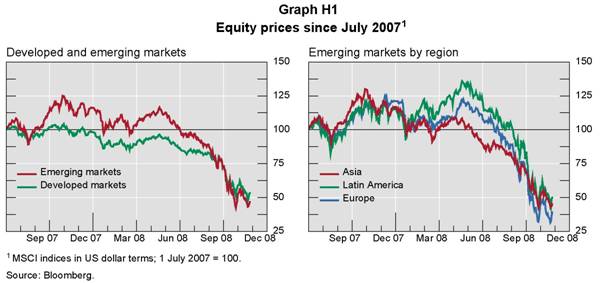

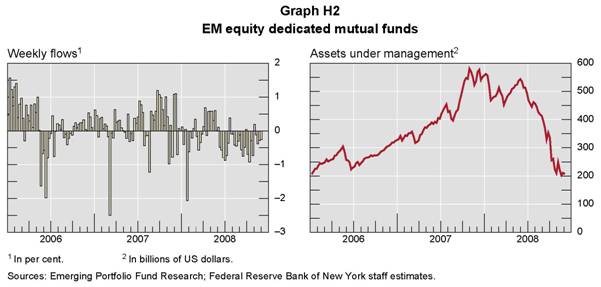

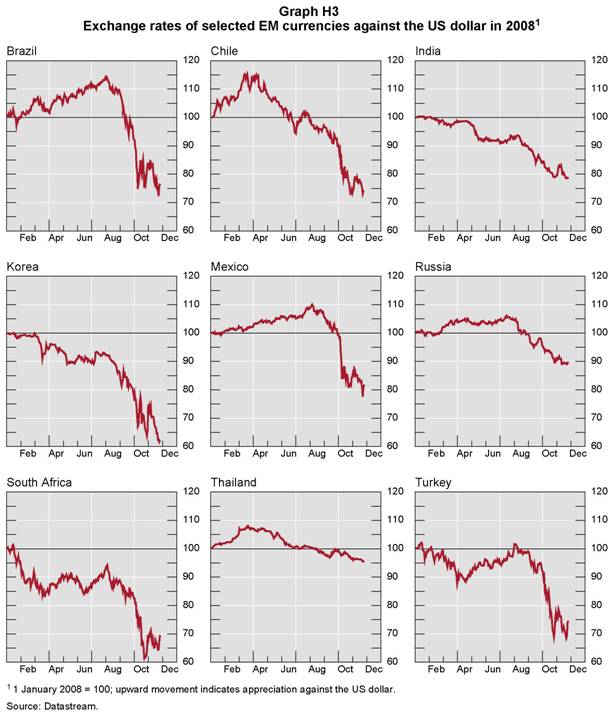

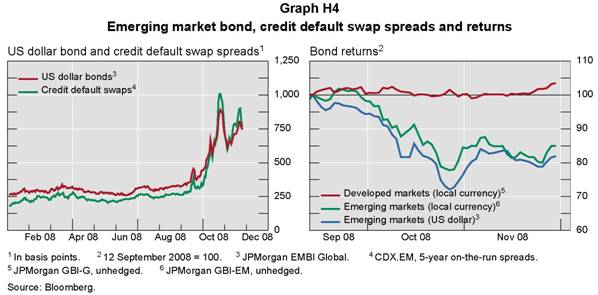

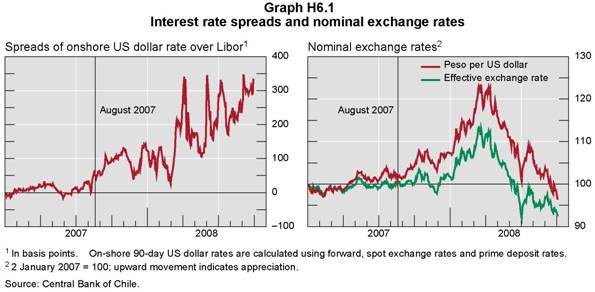

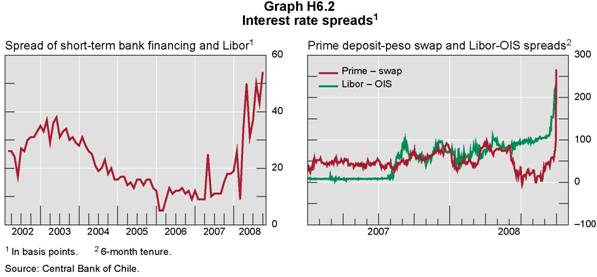

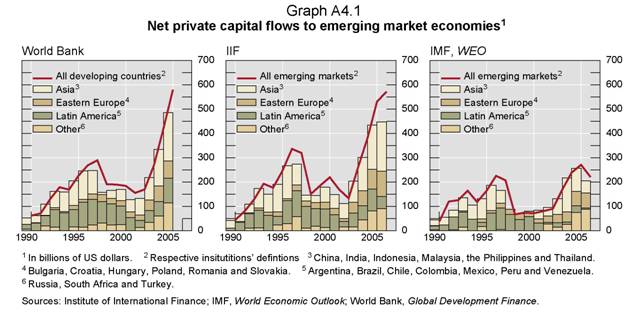

Chapter H provides a preliminary assessment of the impact on EME capital flows of the financial crisis that started in the main centres in August 2007. Although the immediate impact was limited, a major adverse impact has developed since August 2008. A prolonged period of deleveraging in the financial system in major countries, a loss of confidence in large financial firms and an extreme lack of liquidity across financial assets have had a dramatic effect on exchange rates, equity prices and bond yields across the emerging market world. This has confronted policy makers with many difficult dilemmas.

Many of the trends analysed in this Report are too new to permit definitive conclusions. The links between openness to international capital flows and economic welfare are in any case very complex. Nevertheless, one theme recurs in the chapters that follow: a larger number of EMEs now satisfy the macroeconomic and financial system preconditions needed to fully realise the benefits of international capital mobility than was the case even a decade ago. Nevertheless, capital flows cause changes in financial exposures that need to be monitored, even for countries with a comparatively well developed financial system. Many members of the Working Group viewed capital account liberalisation as a process to be managed, and the challenges this poses for policymakers are discussed in the final chapter.

B.The macroeconomic context of capital flows

Introduction

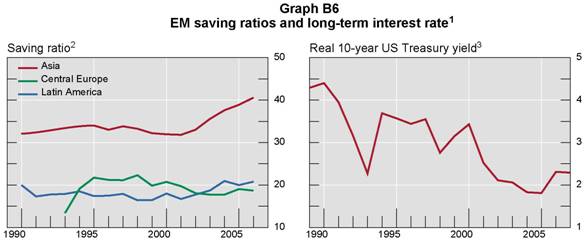

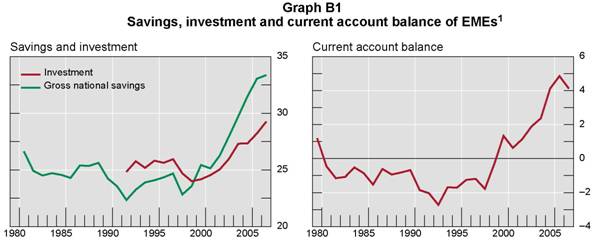

The very sharp rise in capital flows into the EMEs in the period 2002–07 took place in macroeconomic and financial circumstances quite different than in the past. Importantly, such flows were not “needed” to supplement inadequate savings. Indeed, since 1999, increases in saving rates have outpaced investment while the current account balance of EMEs as a whole has not only been in surplus but has also expanded rapidly (Graph B1).5 Private capital outflows from emerging market (EM) residents have also risen sharply (as local pension funds have diversified into foreign assets (see Chapter G) and as local corporations have expanded their operations overseas), in effect partly recycling these surpluses. But they have not expanded enough to offset the growing current account surpluses and capital inflows, resulting in an accumulation of foreign exchange reserves at an unprecedented level. |

| |

|

1 Includes 142 emerging and developed countries as defined by the IMF World Economic Outlook Database; as a percentage of GDP. Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2008.

|

This chapter looks at the main macroeconomic or financial factors behind the major trends of capital flows over the period 2000–07. The first section summarises how capital flows have evolved over the decades. The policy issues raised by capital inflows into EMEs are not new. This brief historical review therefore illustrates the central importance of the macroeconomic context, underlines the significance of sustainable exchange rate regimes, shows how the form that capital movements take matters a great deal, and outlines the policy dilemmas that have arisen. The second section examines net capital flows within the context of current account developments, drawing comparisons with the previous episode in the 1990s.6 The final section discusses the factors that drive these flows.

5 While the aggregate current account surplus might be contributed by a few large countries, the number of

surplus countries rose steadily from 22 in 1998 to around 50 in the mid-2000s. Among those surplus countries,

the median current account surplus increased from $0.2 billion to over $3 billion over that period.

6 The volume and composition of gross capital flows, which have an important bearing on financial stability

issues, are discussed in Chapter C.

Capital flows in historical perspective7

Standard neoclassical theory suggests that international capital movements should respond to differences in expected rates of return on capital across countries. Accordingly, capital “should” flow from high-income countries to developing countries (where capital/labour ratios are lower and the productivity of capital higher), boosting growth for some years and allowing developing countries to run current account deficits. In a world with perfect capital markets, capital flows can be used to smooth consumption or finance profitable investment opportunities.

One qualification to this perspective is that the expected variance of returns also matters: potential investors can be deterred from investing in developing countries because of greater risks.8 Nevertheless, allocating capital to where risk-adjusted returns are higher should raise global welfare.

A second qualification is that capital flows are also known to be volatile. Expected returns can change sharply. A shock in one emerging country can lead foreign investors with limited local knowledge to indiscriminately withdraw from several countries (“contagion”). In addition, financial or monetary shocks in investor countries can greatly destabilise capital movements in emerging markets. There have been many instances of sharp and very disruptive reversals in capital flows hitting small open economies. Many of the policy debates about capital flows to the EMEs depend on how much emphasis is placed on these disruption costs compared with the gains from a more efficient use of global capital.9

The neoclassical perspective broadly fits the pattern seen from the late 19th century up to 1914. Capital flowed to developing areas where the expected return on capital was high. The associated current account imbalances were larger, measured in relation to GDP, than in subsequent periods. Four features of this classical period are worth noting:

•

First, flows were almost entirely denominated in gold standard currencies, mainly sterling – nominal exchange rates were in fact fixed. This arrangement also served to stabilise inflation expectations.

•

Second, the main investment vehicle was bonds, and nominal long-term interest rates were comparatively stable.

•

A third, partly related, feature was that the range of financial assets was extremely limited. Denomination of contracts in gold standard currencies and the stability of long-term interest rates eliminated much of the need for financial diversification and hedging. In any case, the high costs of communication and of computation impeded the development of such activities. Hence the forms that capital flows took were much more uniform than has been the case in recent decades. Nor were there the huge two-way flows of capital that prevail today.

•

The final feature was that much of the movement of capital was long-term in nature, going to finance investment in capital-intensive infrastructure and other real investment. The scope for profitable foreign investment was considerable at that time because real output was expanding twice as fast in capital-importing countries outside Europe than in capital-exporting countries in Europe and because of confidence that bonds would be honoured. Increased real investment led to a deterioration in the current account of recipient countries so that the transfer of capital could be “requited” without a change in the real exchange rate. |

| |

7 This section draws on BIS (1995), Calvo, Goldstein and Hochreiter (1996), Lamfalussy (2000), Kindleberger

(1973) and Turner (1991).

8 This may explain the “Lucas paradox” of capital movement, ie in recent decades capital has moved in the

opposite direction to that implied by capital/labour ratios (Lucas (1990)). Inadequate protection of investor

rights may be another explanation (Alfaro, Kalemli-Ozcan and Volosovych (2008)).

9 In addition, views differ on how far capital flows can be expected to enhance stability. In principle, access to

diversified sources of foreign funds should enhance the stability of small (comparatively undiversified)

economies. But the many real-world features (eg incompleteness of markets, imperfect information) can

undermine such presumption (see eg the recent survey by Ocampo et al (2008), Prasad and Rajan (2008)

and Stiglitz (2008)). |

| |

Because of these features, many of the problems associated with capital flows in more recent decades did not arise.10

The “golden” age of international capital mobility was not re-established after 1919. Attempts made to stabilise currencies in the mid–1920s did not produce an exchange rate regime which lasted long, nor could the large US current account surplus of the 1920s find a durable counterpart in long-term US investment abroad. Borrowing in Europe and Latin America thus led to defaults on a scale not seen in the 19th century. By the late 1920s, attempts to keep exchange rates fixed among the major currencies increasingly strained monetary policies. The system of open capital accounts with stable currencies had, by the early 1930s, collapsed.

For the following 40 years, the role played by capital flows was greatly limited by government restriction. Under the Bretton Woods system established in 1944, comprehensive capital account restrictions were allowed. Such controls were regarded by many as essential for prudent economic policymaking domestically and for permitting the gradual restoration of liberal trading arrangements internationally. Capital account restrictions also allowed the government to control the level of interest rates and gave local banks (often subject to government direction) the effective control of domestic finance.

The 1950s and 1960s were decades of substantial trade liberalisation and strong global growth. Although most countries maintained a tight control on capital movements (despite some easing), their effectiveness became progressively weaker. But the strong pressures that built up on major exchange rates from the mid-1960s were not mainly due to “autonomous” capital flows but to divergent current account positions. Governments resisted these pressures for several years, responding with a series of exchange rate realignments (Brittan (1970)).

The advent of generalised floating among the major currencies in March 1973 occurred against a background of strongly stimulative fiscal and monetary policies in the largest industrial countries. Domestic money growth in the industrial world reached rates unprecedented in the postwar period.11 Nevertheless, the adoption of floating exchange rates did enable current account surplus countries to regain control of domestic monetary conditions in the face of very strong global inflation pressures.

The 1973–74 oil shock accentuated inflation pressures and created a particularly unstable structure of capital flows. The oil-producing countries’ surpluses were placed in short-term deposits with international banks. With recession and large current account deficits curbing fixed investment in the industrial world from 1975, the international banks looked for borrowers in the developing world.12 These forces helped foster a borrowers’ market in international bank lending, leading to a major underpricing of risk. The central banks supervising the major banks were well aware of these risks but were unable to curb the growth of bank lending.13

10 But flows in the classical period did share one important feature with recent flows: capital flows were still

responsive to cyclical developments in lending countries. UK capital outflows, for instance, tended to increase

when depressions at home lowered local interest rates (Imlah (1958)). Deane and Cole (1966) demonstrate

that, from 1875 to 1914, foreign and domestic investment moved in opposite directions. Bordo (2008), who

provides a useful summary of more recent literature, argues that “sudden stops” were also important in

emerging market crises pre-1914: for instance, a rise in the Bank rate of the Bank of England would cut off

capital flows to the emerging markets and produce a contraction of domestic demand that would often lead to

banking crises.

11 On this, see Black (1977).

Capital flows to the developing world rose sharply for several years, taking the form of short-term (or variable rate) bank lending in dollars (or other international currencies). Banks provided finance at rates much lower than long-term bonds (even World Bank finance) in the same currency (Lessard and Williamson (1985)). Capital inflows were in effect used to finance fiscal deficits or sustain private consumption – and not necessarily lift domestic capital formation (Turner (1995)).14 In many instances, capital inflows led to large currency appreciations which, by making imported goods cheaper, encouraged consumption (Ffrench-Davis and Reisen (1998), Rodrik and Subramanian (2009)).

It was this unstable form of capital flow that created the currency mismatches and short-duration debt structures that played a key role in almost all financial crises affecting the EMEs in the 1980s and the 1990s. Heavy reliance on such forms of capital flow, and the substantial subsequent adjustment costs, made policymakers very wary of reliance on external finance more generally. From the onset of the debt crisis in 1982 until the end of the decade, investors in industrial countries avoided those countries which had borrowed heavily. There were substantial write-offs of bank claims on developing countries and increased risk aversion discouraged new investments: measured outflows from crisis-hit countries increased markedly.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, there was a revival of capital flows to the EMEs as growth in the industrial world picked up. After a short-lived tightening in 1994, US policy rates were reduced in 1995 and the decline in European rates continued: this easing of monetary conditions in major countries increased the supply of low-cost finance through banks and the international capital markets.15 International bank lending moved from Latin America to the rapidly growing Asian developing countries (“Tigers”). The issuance of debt securities, mostly denominated in dollars, in international capital markets increased. East Asia and Russia benefited from declining risk premia on sovereign (and even bank) debt. Substantial current account deficits were financed in ways that created large risk exposures (see below). This period of expansion in capital flows, punctuated by the Mexican crisis at the end of 1994, really came to an end only with the Asian and Russian crises in 1997–98.

These crises demonstrated that capital flows into countries with weak banking systems and underdeveloped capital markets create huge risks:

12 This summarises the flows from industrial to developing countries in this period. Flows between industrial

countries also became less stable. Unlike the situation prevailing pre-1914, private flows between major

industrial countries tended to compound, rather than offset, current account imbalances – exchange rate

expectations, rather than returns on real investments, came to dominate capital flows. Strong currency

appreciation put a heavy burden on the traded sector of current account surplus countries, often leading to an

easing of monetary policy that was unwarranted on domestic grounds.

13 Lamfalussy (2000, pp 9–13) describes in some detail the options considered by the Governors of the G10

central banks.

14 This experience prompted at that time much analysis about the sequencing of reforms – the optimum order of

economic liberalisation. Particularly notable was the work of McKinnon (1993) who concluded, “Only when

domestic borrowing and lending take place freely at equilibrium (unrestricted) rates of interest and the

domestic rate of inflation is curbed so that ongoing depreciation in the exchange rate is unnecessary, are the

arbitrage conditions right for allowing free international capital mobility”.

15 On this episode, Lamfalussy (2000) notes that three external factors contributed to this period: the failure of

lending banks to appreciate the risks despite warning signals; a marked easing of conditions in global money

markets from 1995; and real effective appreciation of Asian currencies towards the end of the inflow period as

the value of the US dollar – to which they were pegged – rose.

•

Local banks financed a major expansion of bank lending by short-term borrowing in foreign currency from international banks, creating both maturity and currency mismatches (either directly or on the balance sheets of their creditors).

•

The lack of long-term local currency debt markets meant that debt securities were either too short-term or denominated in foreign currencies.

•

Equity and other financial markets were thin, leading to disruptive boom-and-bust cycles. In some cases, foreign capital was diverted into nontradable instruments that were easily collateralised (eg real estate).

As a result, policy attention shifted from debates about capital account liberalisation per se towards the need to strengthen local banking systems and to develop capital markets. Arguments that capital account liberalisation should be avoided on the second-best grounds of absent markets (eg capital account liberalisation led to an excessive build-up on short-term debt because of the absence of long-term debt markets in local currency) were met with arguments about the need to concentrate on making financial markets more complete on improving bank supervision and on improving the management of liquidity risks.16

Because most crises were preceded by imprudent lending by international banks – there was “overlending” as well as “overborrowing” – there was also renewed emphasis on both better risk appraisal and the development of safer forms of lending by the major international banks. And there was, in addition, a focus on broadening intermediation via capital markets (domestic as well as international).17

The rapid succession of crises that affected virtually every developing country which had opened (albeit in varying degrees) to international financial markets raised another complex issue – contagion. Financial crisis in one country was transmitted with alarming ease to other emerging market countries – even those that did not exhibit major macroeconomic disequilibria.18

Major questions for the international financial system are raised in, to quote Dornbusch’s memorable phrase, “a world of pure contagion, [where] innocent bystanders are caught up and trampled by events not of their making and when consequences go far beyond ordinary international shocks”. For many in the official sector, these crises underlined the real need to make foreign investors more discriminating between countries, and so reduce unwarranted contagion.19 According to the Draghi Report and many similar official documents, the way to do this was to improve the quality and availability of data and make the operations of government and financial firms more transparent. How far markets have become more discriminating in the decade since the Asian crisis is reviewed in Chapter E.

This crisis also demonstrated the vulnerability of economies with large foreign currency liabilities to exchange rate overshooting. Countries that face external financing constraints (ie cannot borrow on international capital markets to cover large deficits) in a crisis can be forced to rapidly generate current account surpluses to meet crisis-induced capital flows abroad (Korinek (2008)).20 In the immediate aftermath of the crisis, very large increases in

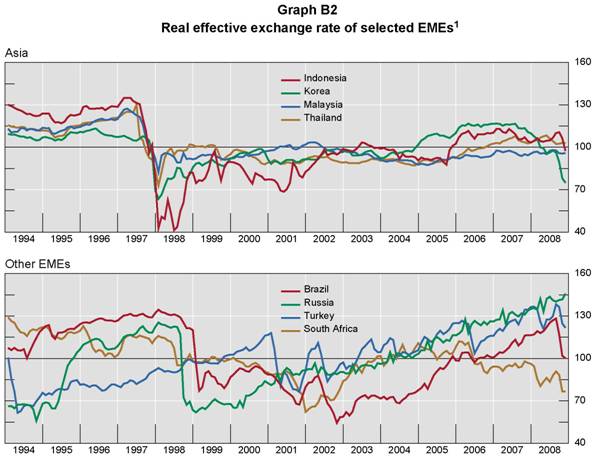

domestic interest rates were often required to stabilise the currency at a depreciated level (Graph B2). The policy options for macroeconomic stabilisation available to crisis-hit countries thus narrowed dramatically (Ocampo (2005)). This led not only to more flexible exchange rate regimes but also to a desire to hold more forex reserves (Chapter D explores these issues).

16 The importance of liquidity risks in national balance sheets was examined in detail in BIS (2000).

17 A similar debate took place after the 1982 debt crisis: Lessard and Williamson (1985) argued that the sources

of finance needed to be broadened and financial instruments had to achieve a better distribution of risks and

rewards. See also Santiso (2003) for a perspective on the political economy of financial markets.

18 One book that brings together research on contagion from many different angles is Claessens and

Forbes (2001).

19 See Financial Stability Forum (2000).

20 Korinek (2008) presents a model of external financing decisions in countries prone to collateral-dependent

financing constraints. Decentralised agents do not internalise how their repayments could accentuate selling pressure on their country’s exchange rate in a crisis. Hence they take on too much systemic risk with their borrowing and so impose an externality on the rest of the economy. |

| |

|

Developments in the dollar and nominal effective exchange rates are summarised in Table B1.

1 1994–2008 = 100 (ie the average over the past 15 years).

Source: BIS.

|

| |

After the Asian crisis, net private capital inflows to EMEs fell abruptly to around one third of the pre-crisis levels. Most of this reflected declines in the more volatile or short-term types of flow: cross-border lending by foreign banks shrank. Foreign direct investment held up comparatively well. The currencies of crisis-hit countries gradually recovered, although real effective exchange rates remained below their pre-crisis levels.

A renewed upswing set in from 2002, as global measures of financial market size (equity market capitalisation, outstanding debt securities, etc) rose strongly. Inflows increased sharply and generally assumed forms that were more sustainable, much less likely to provoke external financing crises than in the past (see Chapter C). Reliance on short-term foreign currency denominated debt flows was greatly reduced: currency mismatches were generally avoided. Perhaps most importantly of all (discussed more fully in Chapter E), the domestic financial system became more resilient: long-term local currency debt markets developed; equity markets deepened; derivatives markets developed; and domestic financial firms became stronger. The intermediation channels through which capital flowed have thus

become much more diversified. Aggregate outflows have grown significantly (partly

intermediated by local institutional investors) and a large current account surplus has

emerged (Table B2). |

| |

| |

Table B1 |

Nominal exchange rates1 |

(2003 = 100) |

|

Vis-à-vis the dollar |

Nominal effective exchange rate |

|

Dec 05 |

Dec 06 |

Dec 07 |

Sep 08 |

Dec 05 |

Dec 06 |

Dec 07 |

Sep 08 |

Latin America |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentine peso |

96.6 |

94.6 |

92.2 |

93.9 |

87.0 |

81.6 |

72.9 |

75.3 |

Brazilian real |

133.9 |

142.3 |

171.5 |

170.4 |

130.0 |

132.4 |

152.8 |

154.1 |

Chilean peso |

133.9 |

130.4 |

138.1 |

129.9 |

126.5 |

117.6 |

117.1 |

110.7 |

Colombian peso |

126.2 |

127.1 |

142.9 |

138.5 |

125.3 |

122.8 |

132.8 |

129.3 |

Mexican peso |

101.4 |

99.3 |

99.4 |

101.2 |

99.1 |

94.8 |

92.2 |

94.1 |

Peruvian nuevo sol |

101.6 |

108.5 |

116.7 |

117.2 |

96.6 |

100.0 |

102.5 |

103.9 |

Venezuelan bolívar fuerte |

74.8 |

74.8 |

74.8 |

74.8 |

71.1 |

69.0 |

65.9 |

66.5 |

Asia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chinese renminbi |

102.5 |

105.8 |

112.3 |

121.1 |

99.0 |

97.4 |

99.1 |

108.6 |

Hong Kong dollar |

100.4 |

100.2 |

99.8 |

100.0 |

97.0 |

91.9 |

87.1 |

88.0 |

Indian rupee |

102.0 |

104.3 |

118.1 |

102.1 |

98.2 |

94.4 |

100.9 |

88.4 |

Indonesian rupiah |

86.9 |

94.3 |

91.8 |

91.7 |

84.2 |

86.7 |

80.1 |

80.5 |

Korean won |

116.4 |

128.7 |

127.9 |

104.8 |

113.9 |

120.8 |

113.9 |

92.2 |

Malaysian ringgit |

100.6 |

107.1 |

114.0 |

110.4 |

98.0 |

99.5 |

101.1 |

98.2 |

Philippine peso |

101.1 |

109.5 |

130.1 |

115.9 |

98.9 |

102.6 |

117.1 |

104.3 |

Singapore dollar |

104.0 |

113.1 |

120.2 |

121.9 |

101.8 |

105.1 |

106.5 |

108.9 |

Thai baht |

100.9 |

115.7 |

123.0 |

121.0 |

98.6 |

108.0 |

109.3 |

107.1 |

Central Europe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Czech koruna |

115.2 |

134.0 |

156.1 |

165.2 |

109.5 |

116.1 |

124.2 |

132.6 |

Hungarian forint |

105.2 |

116.7 |

129.0 |

133.9 |

100.0 |

101.3 |

103.3 |

108.3 |

Polish zloty |

119.7 |

134.7 |

157.2 |

165.6 |

114.0 |

116.8 |

125.4 |

133.6 |

Other emerging |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

economies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Russian rouble |

106.5 |

116.7 |

124.8 |

121.6 |

101.7 |

103.5 |

102.9 |

100.6 |

Saudi Arabian riyal |

100.0 |

99.9 |

99.9 |

99.8 |

97.2 |

91.9 |

87.4 |

|

South African rand |

118.2 |

106.8 |

110.0 |

93.4 |

113.8 |

95.9 |

92.8 |

79.7 |

Turkish new lira |

110.7 |

104.4 |

126.7 |

120.2 |

105.6 |

91.4 |

102.9 |

99.6 |

Memo: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Euro |

104.8 |

116.7 |

128.6 |

126.8 |

100.0 |

104.9 |

109.3 |

109.4 |

Australian dollar |

113.7 |

120.4 |

133.7 |

125.4 |

110.2 |

111.1 |

117.2 |

111.0 |

Japanese yen |

97.8 |

98.6 |

102.8 |

108.5 |

93.9 |

90.3 |

89.7 |

95.4 |

1 Above 100 indicates an appreciation from 2003.

Sources: Datastream; national data; BIS. |

|

| |

Table B2 |

Capital flows in EMEs: various episodes compared1 |

In billions of US dollars |

| |

Inflows |

Outflows |

Forex reserves change |

Current account balance |

1993-96 |

280 |

110 |

90 |

-85 |

1997-2001 |

269 |

193 |

89 |

21 |

2002-07 |

951 |

818 |

584 |

429 |

1 All EMEs as defined in the IMF World Economic Outlook plus Hong Kong SAR, Korea, Israel, Singapore and Taiwan (China); annual average.

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Central Bank of China (Taiwan). |

|

| |

The greater attractiveness of EME assets was also the result of improved macroeconomic performance. Table B3 summarises three key differences between 1993–96 and 2004–07 (the two periods when there were large capital inflows to the EMEs):

•

The EM growth advantage has widened. Changes in Brazil, China and India mean that the potential growth rate of the developing world has risen.

•

EM saving ratios have risen while the average in the industrial world has fallen (mainly because of the decline in the United States). In earlier episodes (particularly in Latin America), capital inflows were often used to supplement declining domestic saving rates rather than to increase fixed investment. Using capital flows to boost consumption reduces future domestic disposable income. While potential output is unchanged, foreigners’ claims on income have increased.

•

EMs’ fiscal positions are stronger.

Have policies of monetary accommodation in advanced economies also shifted demand towards EME assets? Measured by both real short-term interest rates and broad money, the policy stance in advanced countries was more accommodative in 2004–07 than in 1993–96 (Table B4). Given that potential growth rates in the EMEs are higher than in industrial countries, the monetary policy stance appears to have been even more accommodating – on these two simple metrics – in emerging Asia and other EMEs outside Latin America. This has been particularly true in the past two years. However, policies of monetary accommodation in the EMEs have themselves been influenced by external factors (Hannoun (2008), see below for a discussion of the role of the “global liquidity” factor). |

| |

Table B3 |

Summary of macroeconomic determinants |

| |

GDP growth1 |

Savings/ GDP2 |

Investment/ GDP3 |

Fiscal balance4 |

EM |

AE |

EM |

AE |

EM |

AE |

EM |

AE |

1993-96 |

3.9 |

2.7 |

24 |

22 |

26 |

22 |

-3.2 |

-4 |

2004-07 |

7.6 |

2.9 |

30 |

20 |

27 |

21 |

0.7 |

-3 |

AE = advanced economies; EM = emerging markets and developing countries (both IMF World Economic Outlook definitions).

1 GDP average real growth from 1993 to 1996 and from 2004 to 2007 respectively. 2 Savings = gross national savings. 3 Investment = gross fixed capital formation. 4 As a percentage of GDP.

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook and International Financial Statistics. |

|

| |

Table B4 |

Some indicators of monetary expansion1 |

|

Short-term interest rates2 |

Growth of M23 |

|

Emerging

Asia4 |

Latin

America5 |

Other

EMEs6 |

AE7 |

Emerging

Asia4 |

Latin

America5 |

Other

EMEs6 |

AE7 |

1993-96 |

-1.0 |

16.3 |

-4.2 |

2.6 |

12.8 |

11.0 |

2.1 |

1.4 |

2004-07 |

1.4 |

4.7 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

10.2 |

12.1 |

18.6 |

3.6 |

2006 |

2.2 |

5.2 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

11.5 |

14.3 |

19.5 |

4.1 |

2007 |

1.4 |

4.3 |

0.8 |

2.0 |

10.3 |

10.6 |

19.0 |

3.7 |

2008 |

-0.9 |

3.0 |

-1.9 |

-0.1 |

6.7 |

7.8 |

10.7 |

2.9 |

1 Regional figures are weighted averages based on 2005 GDP and PPP exchange rates. 2 Deflated by the year-on-year rise in the CPI; period averages. 3 Deflated by the CPI; annual changes, in per cent. 4 China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan (China) and Thailand. 5 Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela. 6 The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Russia, South Africa and Turkey. 7 Canada, the euro area, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Sources: IMF; Datastream; national data. |

|

| |

At the same time, capital outflows have risen as EM investors (including central banks) have invested heavily in industrial country assets and (to a lesser extent) in assets of other EMEs. By the end of 2006, total holdings of foreign assets by major EMEs excluding China had reached $6.7 trillion, compared with $3.2 trillion in 2001.21 Including China, the total rose to $8.4 trillion.22 A large part of the increase in foreign assets was due to reserve accumulation; but excluding the reserve assets, EMEs still held $5.3 trillion foreign assets in 2006 (Table B5). |

| |

21 Henceforth, unless otherwise stated, major EMEs include Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, the Czech

Republic, Hungary, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines,

Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan (China), Thailand, Turkey and Venezuela.

22 China first reported international investment position data in 2004. |

| |

Table B5 |

Foreign assets of emerging market economies1 |

|

In billions of US dollars |

As a percentage of GDP |

2001 |

2004 |

2006 |

2001 |

2004 |

2006 |

Net foreign assets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

-676 |

-321 |

-187 |

-15 |

-4 |

-2 |

Asia 12 |

147 |

800 |

1,240 |

8 |

18 |

21 |

Asia 23 |

-179 |

-26 |

-70 |

-11 |

-1 |

-2 |

Central Europe4 |

-100 |

-261 |

-337 |

-33 |

-56 |

-56 |

Latin America5 |

-660 |

-686 |

-785 |

-37 |

-37 |

-29 |

Others6 |

-63 |

-174 |

-305 |

-10 |

-14 |

-17 |

Gross foreign assets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

3,185 |

5,640 |

8,353 |

69 |

70 |

76 |

Asia 12 |

2,194 |

4,182 |

6,087 |

113 |

93 |

102 |

Asia 23 |

753 |

1,333 |

1,815 |

45 |

58 |

61 |

Central Europe4 |

115 |

192 |

311 |

38 |

41 |

52 |

Latin America5 |

512 |

657 |

925 |

29 |

35 |

34 |

Others6 |

365 |

608 |

1,031 |

59 |

51 |

58 |

Excluding reserve7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

2,348 |

3,567 |

5,309 |

51 |

44 |

48 |

Asia 12 |

1,617 |

2,572 |

3,821 |

83 |

57 |

64 |

Asia 23 |

363 |

577 |

891 |

21 |

25 |

30 |

Central Europe4 |

63 |

110 |

210 |

21 |

24 |

35 |

Latin America5 |

368 |

453 |

640 |

21 |

24 |

24 |

Others6 |

300 |

431 |

638 |

49 |

36 |

36 |

1 Based on international investment position data. 2 Includes Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan (China) and, from 2004, China. 3 Asia 1 minus China, Hong Kong SAR and Singapore. 4 Includes the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland. 5 Includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela. 6 Includes Russia, South Africa and Turkey. 7 Gross foreign assets less reserve assets.

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Central Bank of China (Taiwan). |

|

| |

This rise in both foreign assets and foreign liabilities of all major EMEs as a whole shows that these countries are playing an increasingly important role in the process of financial globalisation. Nevertheless, the scale of this shift has not matched that of the EME share of world trade. Data computed by Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2008) show that, while the advanced countries’ share of world trade has fallen from around 70% in 1990 to under 60% by 2006, their share of cross-border financial positions has continued to rise.23 According to these authors, the main explanatory factor for cross-country differences in integration with global financial markets is the depth of the domestic financial system: as domestic markets deepen and grow in sophistication, they argue, the private sector’s capability to both acquire foreign assets and sustain issuance of foreign liabilities improves. (This subject is discussed further in Chapter E).

The accumulation of current account surpluses has lifted the net external asset position of most EMEs in Asia and Latin America. Between 2001 and 2006, net foreign assets held in Asia (including China, Hong Kong SAR and Singapore) and Latin America rose from 8% and –37% of regional GDP to 21% and –29% respectively. Excluding China and the two banking centres, net foreign assets held in Asia improved from –11% to –2% of regional GDP over the same period. In contrast, the current account deficits in central Europe, Turkey and South Africa have resulted in deterioration in external balance sheet positions.

Capital flows in the 2000s

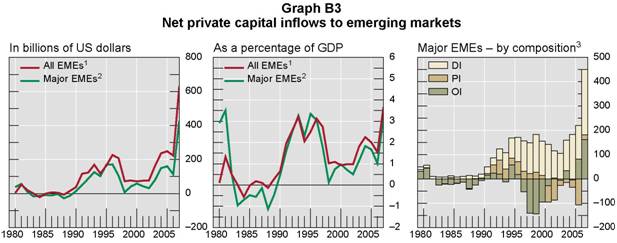

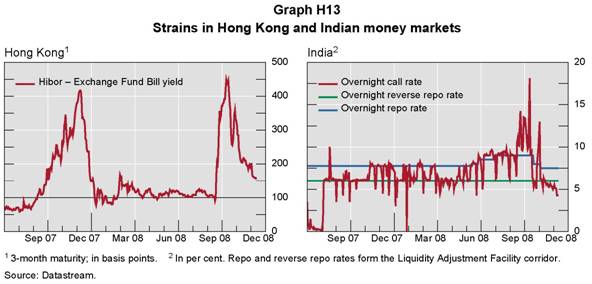

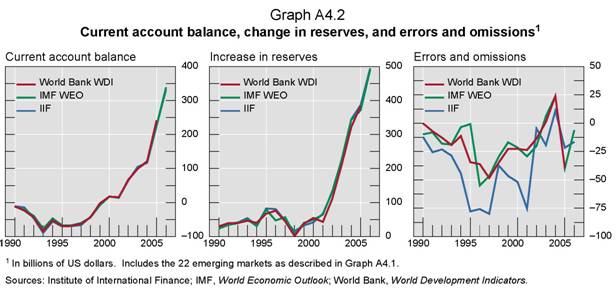

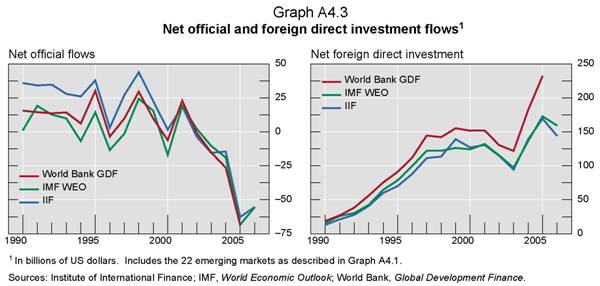

According to the IMF World Economic Outlook, net private capital flows to 143 emerging markets and five small open economies rose from $90 billion in 2002 to around $600 billion in 2007. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) estimates a larger figure of $780 billion for 2007 for a smaller number of countries.24 For consistency, unless otherwise stated, capital flow statistics from the IMF will be the baseline data for analysis in this Report, supplemented with other sources when necessary. Furthermore, in order to focus on the key issues, this report will analyse developments in the major EMEs and refer to other countries only for specific developments. As shown in Graph B3 (left-hand and centre panels), the group of major EMEs captures well the broad trends in capital flow developments – both in US dollar terms and as a percentage of combined GDP.

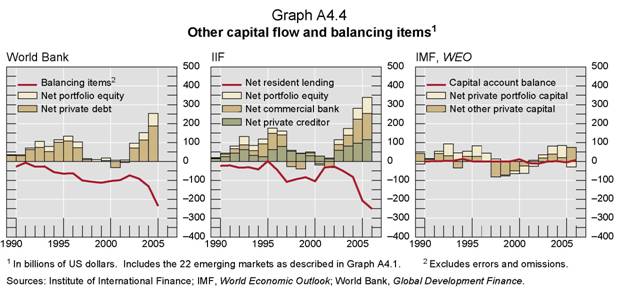

The recent episode of net private capital inflows to EMEs draws comparison to the experience in the early 1990s when foreign capital inflows also expanded at a rapid pace. During the earlier period, a large volume of foreign private capital, mostly in short-term and foreign currency, has helped finance a current account deficit – an excess of domestic investment over savings – in many emerging economies. As a result, these EMEs were highly exposed to the risks of currency and maturity mismatches. In the event of a loss of confidence, holders of short-term paper were able to demand quick repayment, forcing local issuers to meet their foreign debts by prematurely liquidating longer-dated assets or by sharply reducing spending. These mismatches aggravated the financial crises in 1990s of many EMEs. The sudden capital reversals often took place through banking withdrawals, which are recorded as “other investment” in the balance of payments accounts (Graph B3, right-hand panel). |

| |

23 They show that a typical EME has a much smaller cross-border asset and liability position (a median of 70–

80% of GDP) than an advanced economy (a median well over 200% of GDP).

24 Annex 4 compares the differences of three commonly cited capital flow data sources: the IIF, IMF World

Economic Outlook and World Bank Global Development Finance databases. |

| |

|

1 Comprises 142 emerging and developing countries and five small open economies as defined in the IMF WEO 2008 October database. 2 Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia,

Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan (China), Thailand, Turkey and Venezuela. 3 In

billions of US dollars. DI = direct investment; PI = portfolio investment; OI = other investment.

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics and World Economic Outlook; Central Bank of China (Taiwan).

|

| |

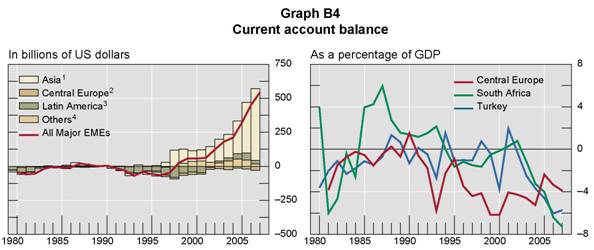

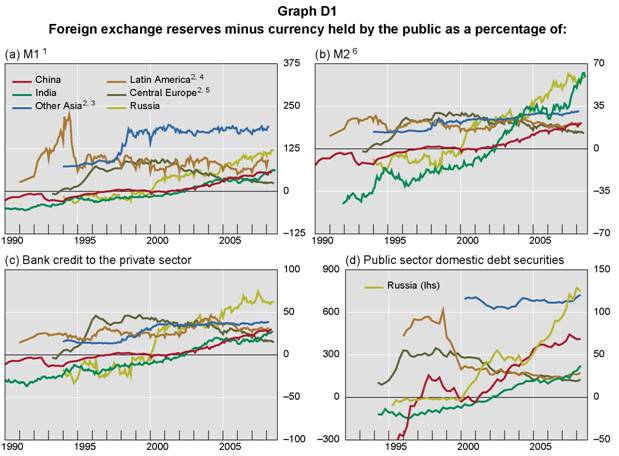

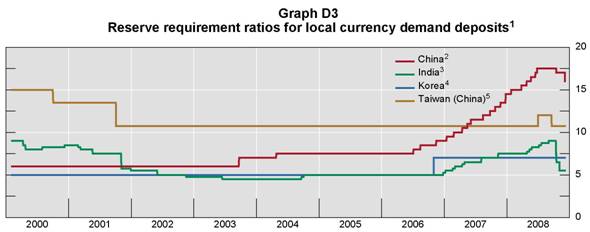

The current episode differs from previous cycles in most regions, with the exception of central Europe, countries have been recording strong current account surpluses or manageable deficits in recent years (Graph B4).25 Under the balance of payments identity, ignoring the over- or understatement of the recorded components (net errors and omissions), the sum of private capital inflows and current account balance should equal to the change in reserve holdings by the monetary authorities. Thus large private capital inflows in combination with observed current account surplus have meant that foreign exchange reserves have increased markedly in most EMEs. Between 2000 and 2007, major economies accumulated more than $2 trillion of foreign exchange reserves. Foreign exchange reserve accumulation on this scale has important macroeconomic and financial implications. This will be examined in detail in Chapter D.

The current account deficits and heavy reliance on foreign financing in central Europe, South Africa and Turkey have become more vulnerable to a reversal in capital inflows (Graph B3, right-hand panel). The Baltic states and several southeastern European countries are in a similarly vulnerable position, with current account deficits around 15% of GDP and high levels of external debt. Box C3 in the next chapter compares the vulnerability of emerging Europe now with East Asia prior to the 1997–98 crisis, and a main source of vulnerability in these countries – cross-border banking flows – will be discussed in Chapter F.

25 Among the three countries grouped under “others”, South Africa and Turkey have been recording current account deficits in recent years; however, they were offset by the large surpluses in Russia. |

| |

|

1 China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan (China). 2 The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland.

3 Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela. 4 Russia, South Africa and Turkey.

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics and World Economic Outlook; Central Bank of China (Taiwan).

|

| |

The macroeconomic drivers of capital flows

Economists have long debated the factors that drive international capital flows. One popular distinction is between those that reflect conditions in investor countries (external factors) and those that are specific to the recipient economies (domestic factors).26 The proponents of the external factor view argue that capital flows into EMEs rise when financing conditions in investor countries ease. Such flows may also move inversely with the business cycles in industrial countries. Others argue that the demand for foreign capital depends largely on prospective returns on domestic investment. In practice, the balance between external and domestic factors is likely to vary according to circumstances.

External factors

Ample “global liquidity” is often cited as an important external factor that has “pushed” capital into EMEs. The term global liquidity, however, is rarely precisely defined. It is generally associated with a wide range of price and quantity measures of the monetary stance in industrial economies. These include low world interest rates and strong money growth in developed countries (see IMF (2007b), pp 34–7, Box 1.4).

Several members of the Working Group noted the dominant role of the US dollar in the global economy. The widespread denomination of international contracts in dollars and the use of the dollar as the reference currency for many developing countries with fixed or quasi-fixed exchange rates meant that the impact of movements in US dollar rates on global economic conditions was much greater than a simple calculation of the US weight in the global economy would suggest.27 In some EMEs, dollar interest rates have a large impact on the financing decisions of households and firms.28 In addition, lending by international banks tends to respond to monetary policy or liquidity shocks in their home country.29 |

| |

26 See Fernández-Arias (1996), Eichengreen and Mody (1998); and Ferrucci et al (2004) for a summary of the

external and domestic factors.

27 On this subject, see Greenwald and Stiglitz (2008). |

| |

In any event, changes in interest rates in investor countries are likely to influence capital flows to the EMEs. There are several channels. First, lower interest rates in the main centres encourage international investors, particularly those with shorter investment horizons, to search for higher yields elsewhere. Second, for the net debtor countries, low international interest rates reduce their servicing costs and indirectly improve their creditworthiness. Third, low international rates encourage borrowers in emerging markets to borrow in international currencies rather than in their own domestic currency.

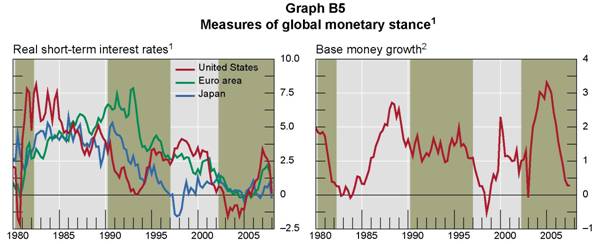

The left-hand panel of Graph B5 shows that declining real interest rates in the G3 economies in the early 1990s and 2000s indeed coincided with rising capital flows to EMEs. In addition, the turning of interest rate cycles, especially in the United States, also matched closely the starting dates of the Latin America debt crisis in the 1980s and the Mexican crisis in 1994. In recent years, however, this link has been harder to detect – perhaps because US policy rates have changed in a more gradual way and have remained comparatively low. For instance, capital flows to EMEs continued to expand between mid-2004 and late 2007 when real interest rates in the United States and the euro area were rising.

One quantitative complement to the interest rate-based measures of global liquidity could be one based on money growth. The right-hand panel of Graph B5 shows the GDP-weighted changes of base money of the G3 economies. This indicator reveals a strong monetary expansion between 2002 and 2004, which coincided with the beginning of the current episode of strong capital flows to EMEs. But again, the sharp contraction in money growth from 2005 to 2007 did not trigger sharp movements in capital in the opposite direction as in earlier episodes. |

| |

|

1 In per cent.2 GDP-weighted change over three years for the G3 economies.Shaded areas are capital flow cycles.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook.

|

| |

In addition to the accommodative monetary stance in the industrial countries, some emerging market economies themselves have contributed to the significant increase in global liquidity by channelling their excess of domestic saving over investment abroad (Bernanke (2005)). An excess of domestic saving over investment in many EMEs and resistance to currency |

| |

28 In central Europe, interest rates in the euro and the Swiss franc exert a similar effect because households

borrow from local banks in these currencies.

29 Cetorelli and Goldberg (2008) analyse a very large set of bank-specific data on intragroup flows to show that

the lending of foreign offices of US banks is affected by US monetary policy. |

| |

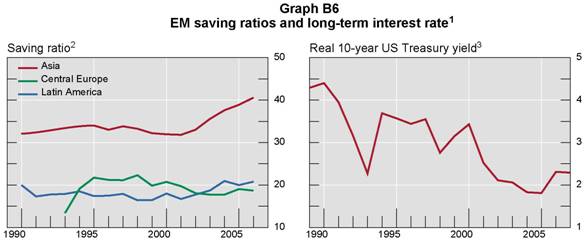

| appreciation has led the monetary authorities to build up large amounts of foreign exchange reserves,30 which were invested in US Treasury securities and other dollar assets. One apparent consequence has been a steady decline in global long-term interest rates. Indeed, between 2000 and 2006, the average saving ratio of Asia rose by 9 percentage points (Graph B6, left-hand panel).31 At the same time, real long-term US interest rates declined steadily (Graph B6, right-hand panel). |

| |

|

1 In per cent. 2 Savings as a percentage of GDP; GDP-weighted. 3 Up to 2002, 10-year nominal Treasury yield minus 10-year inflation expectations from survey data; from 2002, 10-year inflation-indexed Treasury yield.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; Federal Reserve Board; IMF, International Financial Statistics.

|

| |

A related external factor is the business cycle in industrial countries. International business cycles can have both positive and negative impacts on capital flows to EMEs. For example, the economic downturns in most industrial countries during the early 1990s made investment opportunities in EMEs more profitable and encouraged flows into them (Calvo, Leiderman and Reinhart (1996)). When economic conditions in the industrial economies started to improve in the mid-1990s, this factor became less important in driving capital flows to EMEs. However, it is also noted that stronger growth in industrial countries may boost profitability of local firms, which will in turn increase their gains abroad (Ferrucci et al (2004)).

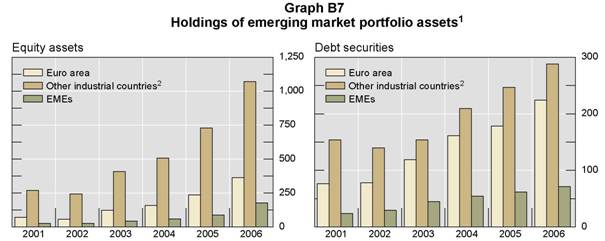

While the external macroeconomic factors discussed above could contribute to the cyclical behaviour of international capital movements, a microeconomic factor – global investors’ portfolio diversification – could lead to a more stable trend growth in capital flows to EMEs (see CGFS (2007a)). In particular, the aggregate financial assets of pension funds and insurance companies in the euro area, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States reached $34 trillion at end-2007. A small percentage increase in their portfolio allocations to EM assets could potentially generate substantial capital flows to the EMEs. Data on institutional investors’ asset allocation to emerging market assets are not readily available, but the IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Surveys show that the holdings of emerging market equities and debt securities by developed countries and emerging market economies have increased steadily since 2001 (Graph B7)

30 Hannoun (2008) argues that the global credit excesses that led to the current financial market turmoil had their

origins in: first, accommodative monetary policies; second, large global imbalances and forex reserve

accumulation; and third, rapid financial innovation. He analyses the multidimensional linkages between these

three powerful forces.

31 Following Jones and Obstfeld (2001), the saving ratio is calculated implicitly, via the current account identity,

as the sum of investment rate and the ratio of current account to GDP. The investment rate is calculated as

the ratio of gross domestic capital formation (gross fixed investment plus changes in stocks/inventories) as a

percentage of GDP. Note that the saving ratio defined as such incorporates all measurement error from both

investment and the current account. |

| |

|

1 In billions of US dollars. 2 Australia, Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Sources: IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey.

|

| |

Domestic factors

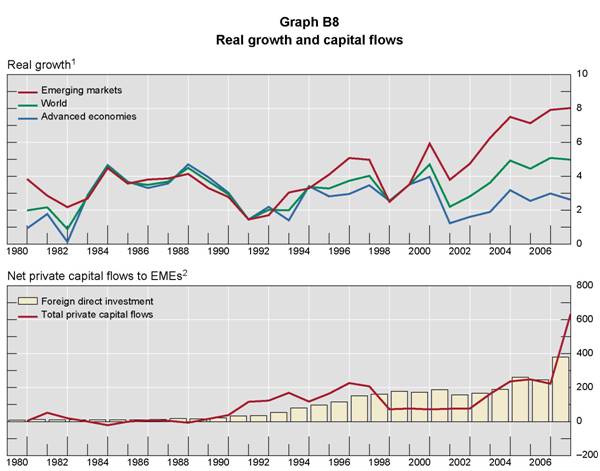

A major element that “pulls” international capital to the EMEs is higher expected risk-adjusted returns. Better growth performance and a more stable macroeconomic outlook are thus important external factors. Graph B8 shows that the pace of net private capital flows into EMEs tends to pick up whenever the growth in the emerging markets surpasses that in the advanced economies.

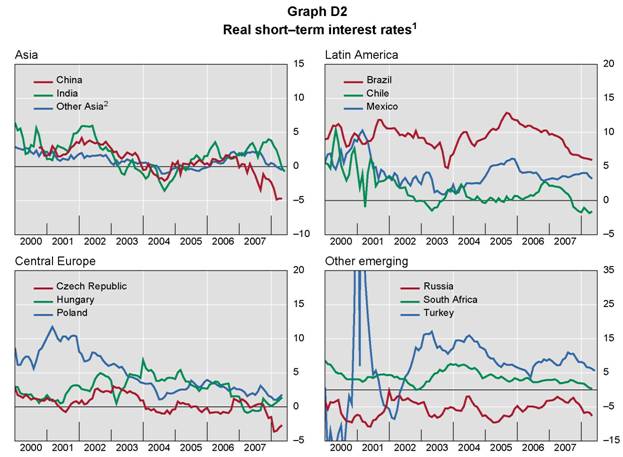

Equally, the volatility of growth and inflation has come down sharply from the 1990s, when so many countries went through very disruptive crises, and is now close to that prevailing in industrial countries (Table B6). Reforms of macroeconomic policies played a key part. For example, the successful disinflation programmes implemented in many Latin American economies during the late 1980s and early 1990s, which were accompanied by fiscal adjustment, helped reduce perceived risk on real domestic investment and stimulate capital inflows.

As discussed more fully in Chapter G, institutional reforms and policies that ease the access of foreign investors to domestic financial markets, such as the removal of capital controls and the liberalisation on foreign direct investment, have also facilitated international capital movements.

In sum, the accommodative monetary stance and low interest rates in major industrial countries have played some part in encouraging both equity and debt flows to EMEs, particular in the early stage. At the same time, the strong economic outlook and sound domestic policies might appear to be important factors in attracting foreign capital into these countries. The fact that capital continues to flow into EMEs after monetary policies were tightened in the past few years up to August 2007 might suggest that improved fundamentals could outweigh other factors in international investors’ investment decisions (this is discussed further in Chapter G). Furthermore, emerging economies which have surplus domestic savings over investment export their surpluses officially via foreign exchange reserve accumulation or through private channels. The domestic financial implications of these official outflows will be discussed in the next chapter while the intermediation of private capital outflows will be examined in Chapter G. |

| |

Table B6 |

Volatility1 |

|

Output2 |

Prices3 |

Exchange rate4 |

|

1990-99 |

2000-Q2 2006 |

1990-99 |

2000-Q2 2006 |

1990-99 |

2000-Q2 2006 |

Mexico |

3.9 |

2.6 |

10.5 |

2.0 |

26.0 |

6.4 |

Korea |

4.9 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

0.8 |

19.0 |

8.1 |

Thailand |

7.5 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

19.3 |

6.6 |

Hungary |

1.8 |

1.0 |

7.2 |

2.6 |

6.7 |

12.3 |

South Africa |

2.3 |

1.0 |

3.6 |

3.1 |

9.1 |

21.2 |

Memo: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

United States |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1 Measured as the standard deviation of annual changes of quarterly averages; in per cent. 2 Real GDP. 3 Consumer prices. 4 National currency per US dollar.

Source: Updated version of Mohanty and Turner (2005). |

|

| |

|

1In per cent.2 Comprises 142 emerging markets and five small open industrial economies; in billions of US dollars.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2008.

|

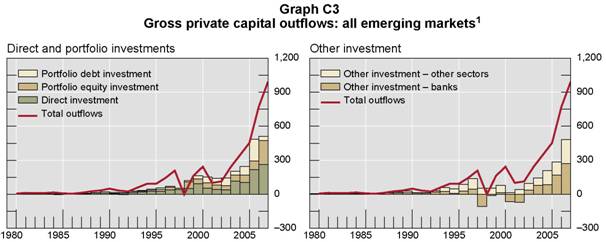

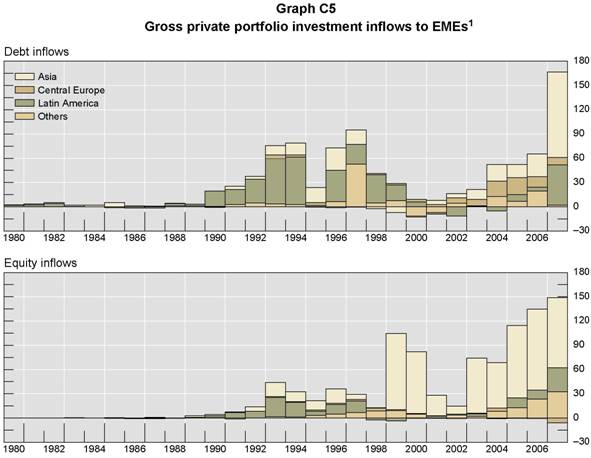

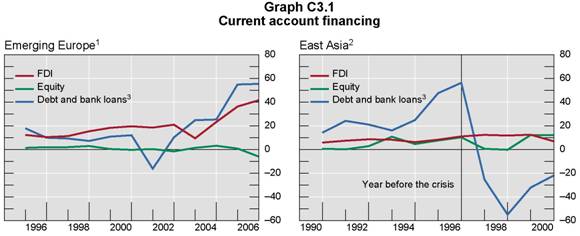

C. Composition of capital flows and financial stability

Composition and risk exposures

The composition of capital flows matters for monetary policy, for the management of liquidity and for financial stability. It matters for monetary policy because some forms of capital flow are more sensitive to the central bank’s policy rates than others. At one end of the spectrum, short-term capital flows are typically very sensitive to domestic short-term rates (given exchange rate expectations). Because domestic short-term rates are regarded as a key policy device, restrictions on cross-border investments in short-term debt instruments have often been the last to be removed.32 It matters for the management of liquidity because the maturity or duration structure will influence the choice of instruments for sterilisation.

Capital flow composition matters for financial stability because it determines how risks are shared between provider and recipient (and so defines risk exposures), impacts domestic fixed capital formation, affects the cyclical sensitivity of aggregate flows and influences the future pattern of international adjustment.33

From the perspective of financial stability, four dimensions are of general importance:

a. Equity versus debt. Equity forms of investment serve to transfer risk to the supplier

of funds and away from the user of funds.Debt has to be serviced irrespective of the

returns earned on the investment financed by borrowing. The servicing of equity

liabilities, on the other hand, depends on the returns actually earned.

b.Short-term versus long-term. Borrowers reliant on long-term debt to finance long-

term projects are less vulnerable to interest rate and refinancing risks. A decline in

the market value of long-term debt paper – eg because of changed market

assessment of risk or higher interest rates – will be borne by the lender.

c. Investment versus consumption. Capital inflows to finance current public sector

spending allow governments to delay measures of fiscal consolidation. Equally,

inflows that in effect finance increased private consumption (eg thanks to exchange

rate overvaluation or the sale of domestic assets) can be less welcome than inflows

associated with increased real fixed capital formation.

d.Foreign versus domestic currency and tradables versus non-tradables. National

balance sheet considerations could suggest that foreign currency inflows should be

used to invest in foreign currency earning assets – that is, an expanding productive

capacity in tradables, rather than in non-tradables. Otherwise, the country faces

currency mismatches.

In addition, borrowing in foreign currency to finance investment in tradables increases productive capacity in the tradable sector and so, at constant terms of trade, tends to increase future trade surpluses to finance foreign currency debt obligations.

32 Attempts by industrial countries to maintain such controls in the 1960s and 1970s were, however, partly

frustrated by the growth of the eurodollar market (ie bank deposits denominated in currencies other than that

of the country in which the bank is domiciled). An excellent account of this issue is Chapter 24 of Caves and

Jones (1973). The recent growth of NDF markets offshore for many EME currencies has a similar effect of

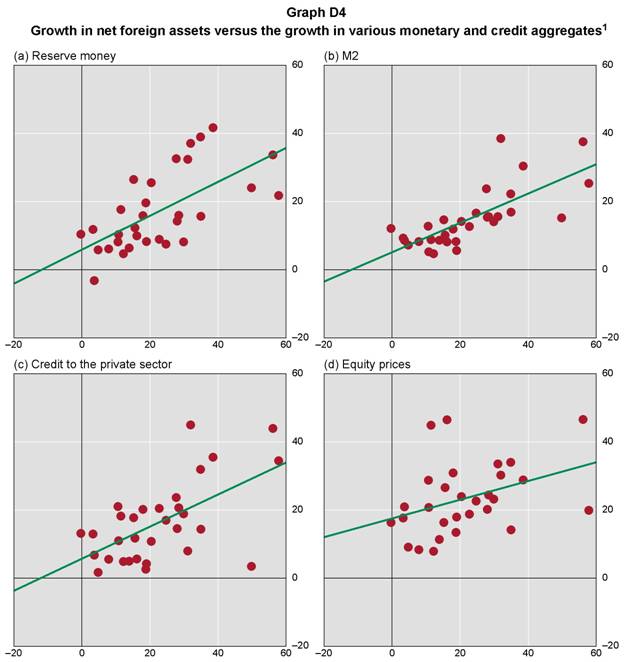

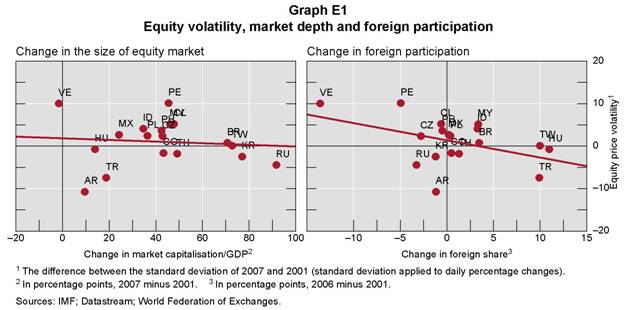

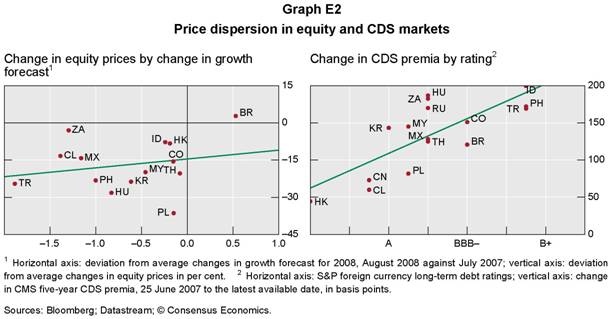

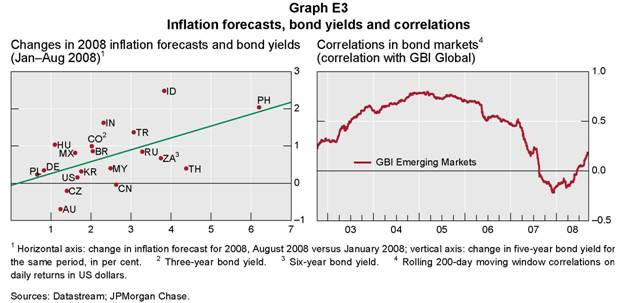

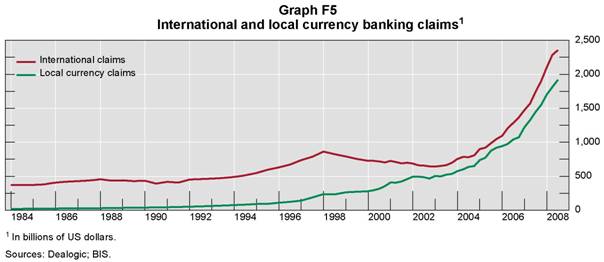

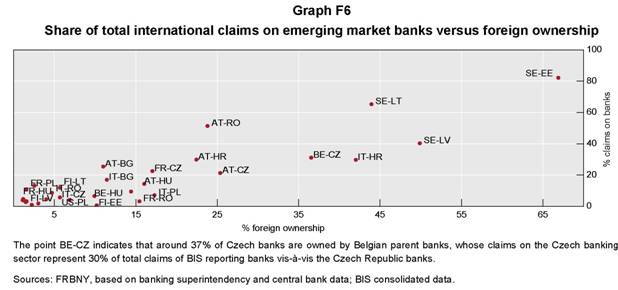

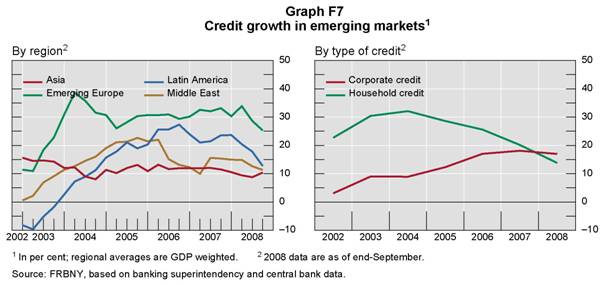

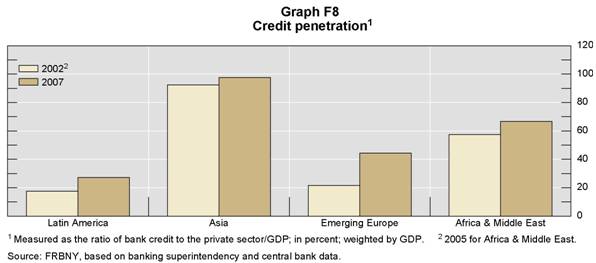

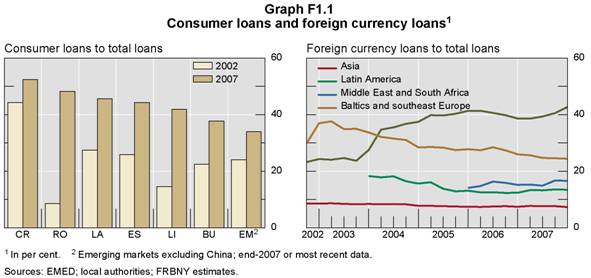

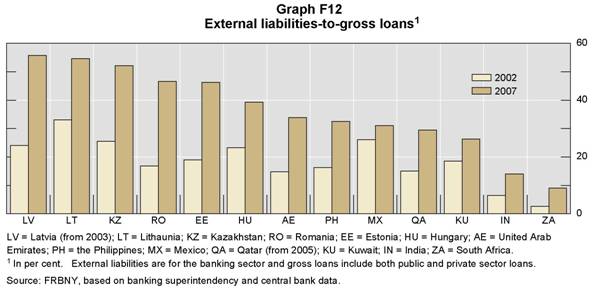

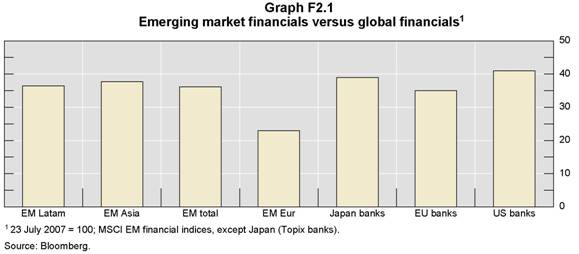

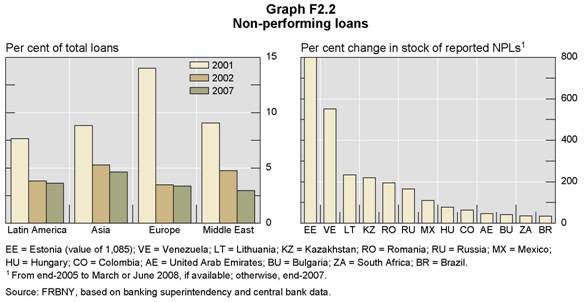

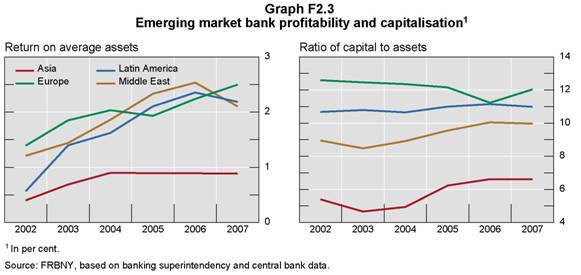

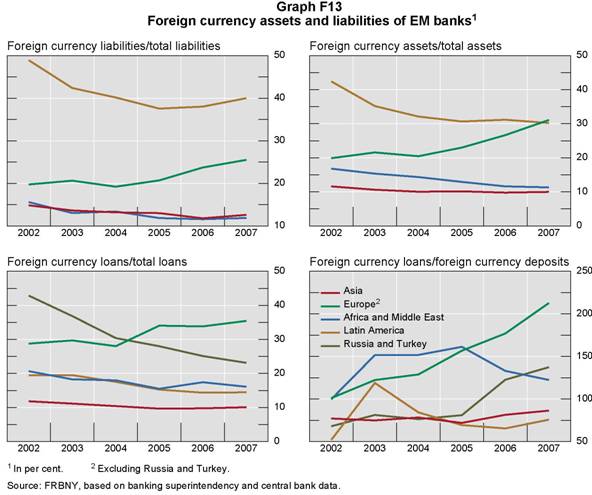

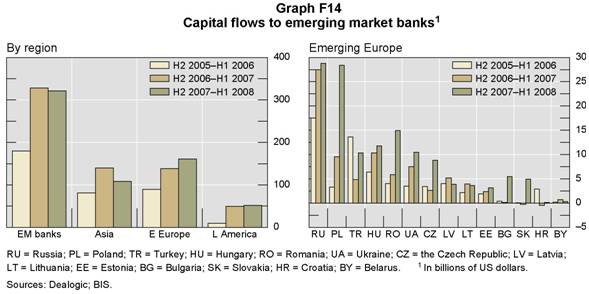

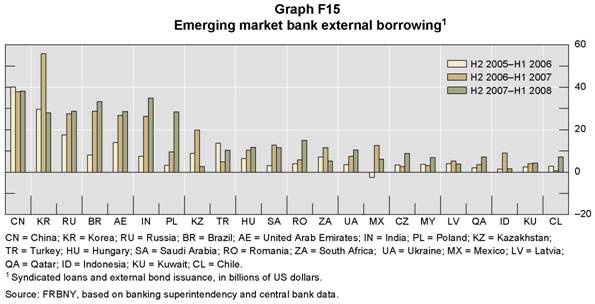

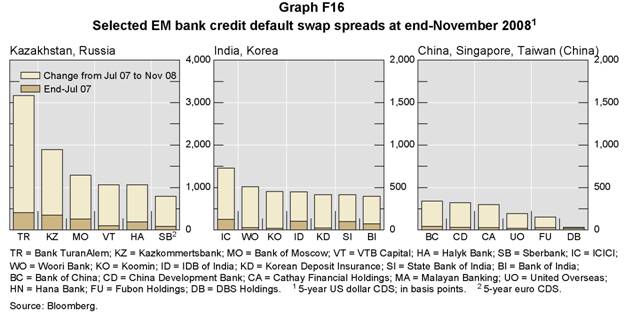

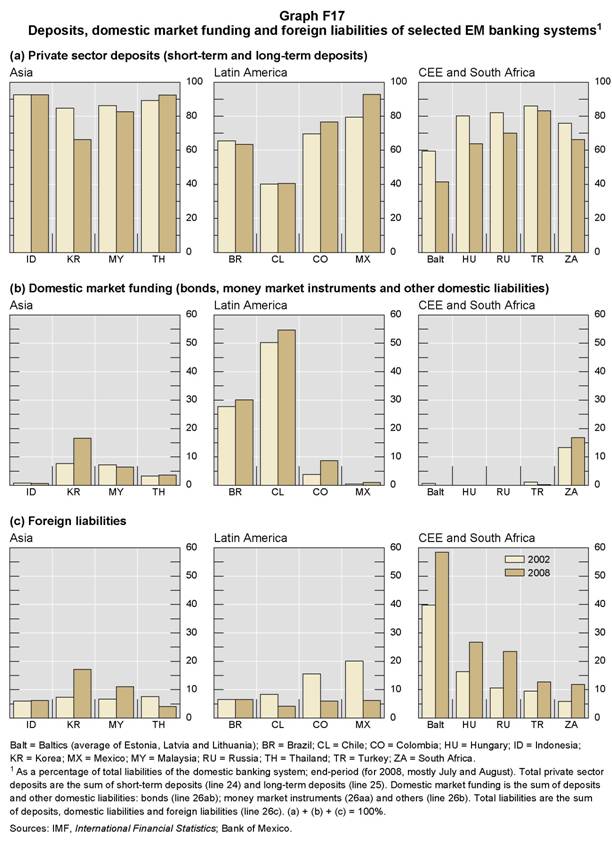

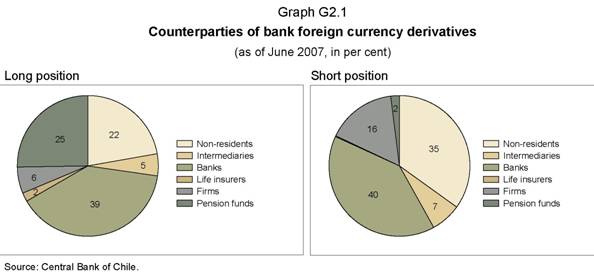

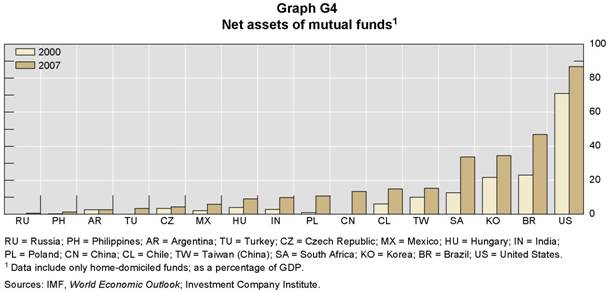

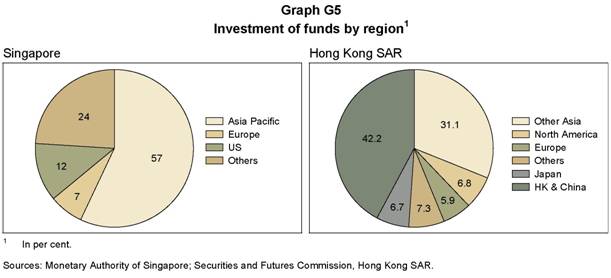

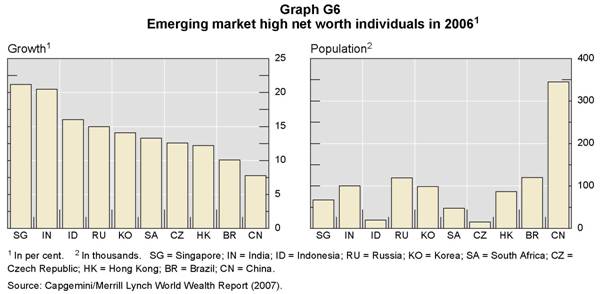

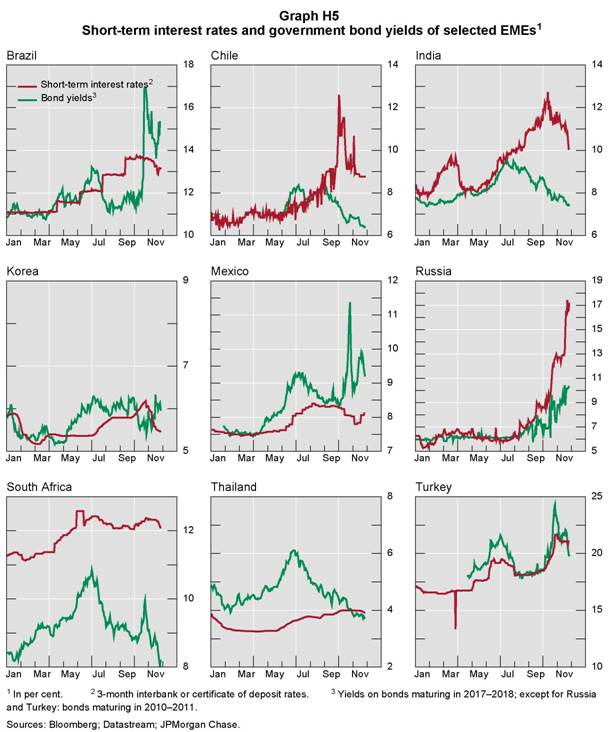

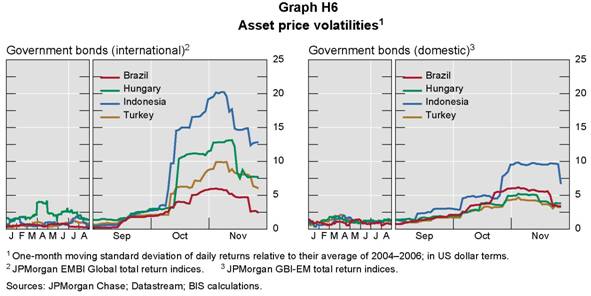

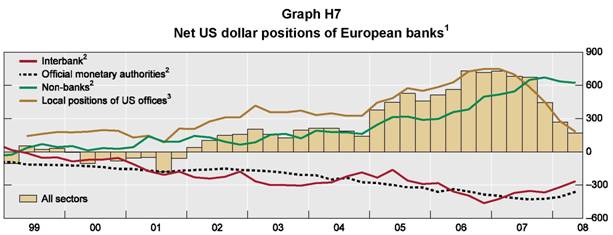

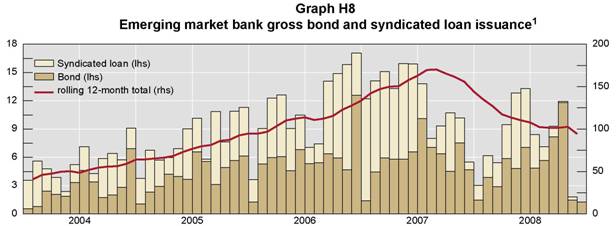

undermining the effectiveness of capital controls (see Chapter E).