IST,

IST,

Report of the Working Group on State Government Guarantees

|

Contents Letter of Transmittal September 16, 2023 Shri T Rabi Sankar Dear Sir, Report of the Working Group on State Government Guarantees The 32nd Conference of the State Finance Secretaries deliberated on the issue of lack of effective monitoring and reporting of guarantees issued by the State Governments and recommended constituting a Working Group to review the existing system of reporting and monitoring of State Government guarantees. We are pleased to submit the Report of the Working Group on State Government Guarantees.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Working Group would like to thank Shri T. Rabi Sankar, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for giving the Group an opportunity to examine the issues pertaining to the guarantees issued by the State Governments. The Group has also been immensely benefited by the valuable inputs given by Shri R. Subramanian, Executive Director, RBI during the deliberations at various meetings of the Group. The Working Group expresses its sincere gratitude to the special invitees from RBI, namely, Shri Manoranjan Mishra, Chief General Manager (CGM); Dr. D. P. Rath, Adviser-In-Charge; Shri A. Unnikrishnan, Principal Legal Adviser, and Shri Arnab Kumar Chowdhury, CGM-In-Charge, for their wholehearted participation in the deliberations of the Group and for their significant contributions in finalizing the Report. The Group would like to thank officials from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India; Comptroller and Auditor General of India; State Governments; and RBI for their participation in the Group meetings and offering valuable suggestions that helped in finalizing the Report. The Group would like to place on record its deep appreciation for the excellent secretarial support provided by the Internal Debt Management Department of RBI, and its officials, especially, Shri Harsh Kumar Gautam, General Manager, Shri Anand Prakash Ekka and Shri Sourit Das, both Assistant Advisers, and Shri Pranav Malviya, Manager. The Working Group is also thankful to Shri Prashant Chandawat and Shri Avinash Deo, Assistant Managers for their logistical and other administrative support in organizing the meetings of the Working Group. List of Abbreviations

Guarantee is a potential future liability that is contingent on the occurring of an unforeseen future event. If these liabilities get crystallised without having adequate buffer, it may lead to increase in expenditure, deficit, and debt levels for the State Government. If the guarantee invoked is not honoured, it may cause reputational damages and legal costs to the Guarantor. It is, therefore, important to assess, monitor and be prudent while issuing guarantees, especially, when such guarantees are issued by a State Government. Besides, State Government should be transparent in terms of data disclosure and assessing the risk associated with it. Another related concern associated with the guarantees extended by the states, has been the increasing bank finance to Government owned entities backed by Government guarantee, especially, where the bank finance appeared to substitute budgetary resources of the State Governments. 2. Keeping in view the inherent risks associated with the guarantees extended by the State Governments on their fiscal health and to the banking system, it was decided during the 32nd Conference of the State Finance Secretaries held on July 07, 2022 to set up a Working Group comprising members drawn from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India; Comptroller and Auditor General of India and a few State Governments. It was also decided to include senior officials from select departments within RBI as special invitees to the Group deliberations. The terms of reference of the Working Group were as under:

3. Taking cue from the constitutional provisions as applicable, observations made by the various Groups/ Committees constituted in the past, practices followed by various states in terms of fixing the ceiling on guarantees issued, the related reporting framework, and based on extensive deliberations the Group members had amongst themselves during the two meetings held, the Group has finalized its Report. 4. The major recommendations of the Working Group are as under: a) There should not be any distinction made between Conditional/ Unconditional, Financial / Performance guarantees as far as assessment of fiscal risk is concerned as all of these are in the nature of contingent liability that might get crystallized on a future date (Para 2.7). b) The word ‘Guarantee’ should be used in a broader sense and may include instruments, by whatever name they were called, if these create obligation on the part of the Guarantor (State Government) for making payment on behalf of the borrower (State Enterprise) at a future date, contingent or otherwise (Para 2.7). c) State Governments may be guided by the following guidelines issued by the Government of India while formulating their own Guarantee policy (Para 2.13):

d) Purpose for which Government Guarantees may be issued, should be clearly defined in line with Rule 276 of General Financial Rules, 20171. Government Guarantees should, however, not be used to obtain finance through State owned entities, which substitutes budgetary resources of the State Government. Government Guarantees should not be allowed for creating direct liability/de-facto liability on the state (Para 2.14). e) In order to ensure uniformity and consistency in data being reported, the State Governments may publish/ disclose data relating to guarantees, as per the Indian Government Accounting Standard (IGAS) recommended by Government of India, which can also be used by CAG for their audit and by RBI for its annual publication ‘State Finances: A Study of Budgets’ (Para 3.7). f) The Group is of the view that a reasonable ceiling on issuance of guarantees by the State Governments may be desirable. The Group recommends a ceiling for incremental guarantees issued during a year at 5 per cent of Revenue Receipts or 0.5 per cent of GSDP, whichever is less (Para 3.11). g) State Governments should classify the projects/ activities as high risk, medium risk and low risk and assign appropriate risk weights before extending guarantee for them. Such risk categorisation should also take into consideration past record of defaults. The Group suggests that the states should conservatively keep the lowest slab of risk weight at 100 per cent. Additionally, states should disclose their methodology for assigning risk weight (Para 3.12). h) The guarantee fee charged should reflect the riskiness of the borrowers / projects / activities. A minimum of 0.25 per cent per annum may be considered as the base or minimum guarantee fee and additional risk premium, based on risk assessment by the State Government, may be charged to each risk category of issuances. The Guarantee fee should also be linked to the tenor of the underlying loan (Para 3.14). i) States should continue with their contributions towards building up the GRF to a desirable level of five per cent of their total outstanding guarantees over a period of five years from the date of constitution of the fund. The corpus may be maintained on a rolling basis thereafter (Para 3.17). Introduction 1.1 In the 32nd Conference of the State Finance Secretaries (SFS) held on July 07, 2022, the issue of increasing bank finance to government owned entities, especially, where bank finance appeared to substitute budgetary resources of the State Governments was flagged in one of the technical sessions. RBI has, in the past, flagged the issue of bank finance to government-owned entities, often in violation of the prudential guidelines. Since most of these loans are backed by explicit guarantees offered by the State Governments concerned, it may be necessary for the states to take into consideration the risk of guarantee being invoked. The lending bank/NBFC should also undertake comprehensive assessment of the loan proposal without taking comfort from the guarantee extended by the state. 1.2 Taking note of the various kinds of risk involved with the guarantees issued by the states on their fiscal health, it was decided in the SFS Conference to constitute a Working Group, comprising members drawn from MoF, Government of India (GoI); select State Governments; and special invitees from departments concerned within the RBI, that would look into all the related issues concerning guarantees extended by the State Governments. Accordingly, this Working Group comprising representatives from Department of Expenditure, MoF, GoI; Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), States of Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Karnataka, Odisha and the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir was constituted. 1.3 The Working Group2 comprised the following members:

The Working Group also included the following representatives from RBI as ‘Special Invitees’:

1.4 The terms of reference of the Working Group were as under:

Methodology and Approach 1.5 Within the contours of the Terms of Reference, the Group went through the extant practices being followed by the various states, the initiatives taken in the past to address the issue relating to State Government guarantees, and the status of the recommendations made by various Committees and Groups set up in the past. The Group started its deliberations with the definition of guarantee, followed by the extant reporting framework, the need for setting a ceiling on quantum of guarantees issued, etc. The Group held its first meeting on December 02, 2022 through virtual mode and the second meeting on February 27, 2023 through hybrid mode. Structure of the Report 1.6 The rest of the Report is structured in four parts. Issues relating to Government guarantees and the best practices followed by different countries are covered in Chapter II. Chapter III covers the Indian sub-national experience on management of guarantees, including the recommendations of previous Committees/ Groups formed on similar issue. Issues relating to bank financing of guarantees have been covered in Chapter IV. Chapter V discusses the recommendations made by the Group. State Government Guarantees: Issues and Challenges 2.1 Guarantee is a type of contingent liability protecting the investor/ lender from the risk of default by a borrower. Guarantees are usually sought when the investors/ lenders are unwilling to bear the risk of default. A contract of guarantee, as defined in the Indian Contracts Act, 1872 is a contract to perform the promise, or discharge the liability of a third person in case of default. A guarantee contract is different from an indemnity contract in which there are two parties involved and one party promises to save the other from loss caused by the promisor, or by the conduct of any third party. 2.2 There are usually three parties involved in State Government guarantees, namely, the borrower, which is usually a government owned or sponsored enterprise, the guarantee provider which is the State Government, and the lender who is also the beneficiary of the guarantee. Guarantees while being innocuous in good times, may lead to significant fiscal risks and may burden the state finances leading to large unanticipated cash outflows and increased debt. As upfront cash payment is usually not required in case of guarantees, that may be one of the reasons why the State Government guarantees have profligated in recent times. As these liabilities are contingent upon certain events, the quantum and timing of potential costs / cash outflows owing to guarantees are often difficult to estimate. Accordingly, their management is difficult and are typically not reported in budget deficit (Razlog et. al., 2020). A framework on issuance and management of guarantees can, however, help governments overcome these difficulties to some extent. 2.3 State Governments are often required to sanction, and issue, on behalf of various state enterprises/ cooperative institutions/ urban local bodies and other state-owned entities, guarantees in favour of their lenders which are generally commercial banks or other financial institutions. There is a specific ceiling of 0.5 per cent of GDP for additional guarantees to be issued by the Central Government in a financial year as stipulated under the FRBM Act. 2.4 In order to improve transparency in disclosure of information relating to guarantees, Ministry of Finance, Government of India had issued accounting standard / disclosure requirements in December 2010 with respect to the guarantees given by the Governments (GoI, 2010). The Standard applies to preparation of the Statement of Guarantees for inclusion and presentation in the financial statements of the Union, States and Union Territories. While the Central Government has been disclosing the information in the prescribed format (Annex I) as part of its budget documents, there are very few states doing so. 2.5 Conventional framework of fiscal analysis does not provide much insight on the guarantees and the associated risks and focuses mainly on the budgetary indicators. Guarantees are not recognized in macroeconomic fiscal statistics unless the triggering event is deemed to have occurred (Saxena, 2017). The Twelfth Finance Commission had, inter alia, observed “although contingent liabilities do not directly form a part of the debt burden of the state, the state will be required to meet the debt service obligations in the event of default by the borrowing agency” (GoI, 2004). These guarantees are classified under ‘contingent liabilities’ of the states as they come into play on the occurrence of a pre-specified event agreed in the guarantee contract. Accordingly, a true assessment of the fiscal position of a state by taking into account the guarantees outstanding is important to assess its fiscal health. In the larger public interest and for the sake of transparency, complete data on guarantees should be distinctly disclosed on a regular basis and made available for public scrutiny. Definition of Guarantees 2.6 In order to analyse various risks associated with the issuance of guarantee, it needs to be clearly defined as to what constitutes ‘guarantee’. This would, in turn, help in having a better understanding of its implication on the fiscal health of the State Governments. According to Saxena (2017),“Government guarantees are legally binding undertakings given by a government to assume responsibility for servicing a debt or the performance of an obligation, on behalf of another entity under certain specified conditions – typically a default by that entity”. As per the GoI (2022), “Guarantees are contingent liabilities that arise on occurrence of an event covered by the guarantee. Since guarantees result in an increase in contingent liabilities, they should be examined in the same manner as a loan proposal, taking into account, inter alia, the credit-worthiness of the borrower, the extent of exposure sought to be covered by a sovereign guarantee, the terms of the borrowing, justification and public purpose to be served, probability of invocation and possible costs of such liabilities, etc. Government will be liable to pay in case the entity/ organization defaults in respect of which guarantee is given.” 2.7 The Group is of the view that there should not be any distinction between Conditional / Unconditional, Financial / Performance guarantees for the purpose of arriving at total amount of guarantees extended by the Government as all of these would be in the nature of contingent liability that might crystallize at a future date. Additionally, the word ‘Guarantee’ should be used in a broader sense and may include all such instruments, by whatever name they are called, if these created an obligation on the part of the issuer for making payment on behalf of the borrower at a future date, contingent or otherwise. 2.8 State Governments also issue letter of comfort4 (LoC) to the lender or supplier of a public agency or enterprise. Issuing a LoC does not necessarily imply that the Government guarantees repayment of the loan, it merely provides reassurance to the lending institution that the Government is aware of the credit facility being sought by the borrowing entity and supports its decision. LoC can pose serious reputational risk to the Government and if it involves making of a payment by the State Government to avoid reputational loss, it is suggested that the State Government should include such LoCs as part of its total contingent liabilities. Risk from Guarantees 2.9 While guarantees may be beneficial to the state enterprises, they can also cause several risks for the Government issuing the guarantee (Lu et al. 2019), such as: a) Moral Hazard Guarantees, at times, could create moral hazard, leading to the guaranteed entity to be sub-optimal in performing its obligation. Similarly, investors and lenders may have less incentive to perform due diligence in scrutinizing the project as against the classic non-recourse project financing. b) Fiscal Risks The risk arises from the potential negative impact on the fiscal/ financial position of the State Government due to the factors that affect the performance of the borrowing state enterprises. As it is difficult to predict the invocation of guarantees and the size of the pay-out, they usually are not scrutinised with the same rigor as it is done under the budget process in case of regular spending. Upon its invocation, it is possible that the Government may not have fiscal capacity to meet the obligation. Such problems could magnify when guarantees have been given to multiple state enterprises, while the state budget is already stressed. Various factors such as macroeconomic shocks and the realisation of contingent liabilities could cause fiscal risks for State Governments (Mukherjee et. al. 2022). 2.10 State Government can also undertake implementation of specified projects through state agencies and provide guarantee on behalf of those entities for borrowing from banks/ financial institutions. Such arrangements do not fall within the annual borrowing ceiling fixed by the Central Government for the individual State Government. Often termed as ‘off budget borrowing’, this is an explicit liability of the State Government, though not reflected as a debt in the budgetary documents. 2.11 International institutions, including the IMF, have long been advocating fiscal transparency and accountability as a way to identify, monitor, and ultimately minimise fiscal risks. With regard to risks arising from guarantees, a prudent fiscal policy has to deal with three related areas: (i) the exposure to guarantees and policy for the same; ii) data disclosure and ensuring discipline in issuance of guarantees; and iii) management of related risks. Recognising the risks from the guarantees, many countries have started disclosing data on the guarantees either in their budget documents or in other government reports (Box I). 2.12 Management of guarantees can be strengthened by taking the following steps (Saxena, 2017):

2.13 The Working Group recommends that the State Governments may be guided by the following guidelines issued by the Government of India (GoI, 2022) while formulating their own Guarantee policy:

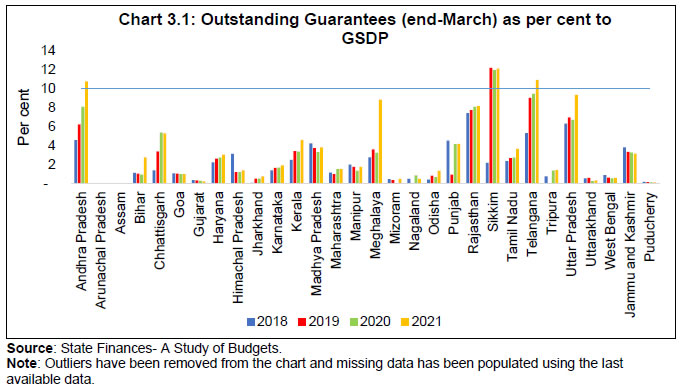

2.14 The purpose for which Government Guarantees can be issued, should be clearly defined in line with Rule 276 of General Financial Rules, 20176, to ensure the financial viability of projects or activities undertaken by Government entities, including, social and economic benefits; to enable central/state public sector entities to raise resources at lower interest charges or on more favourable terms; to fulfil the requirement in cases where sovereign/ state guarantee is a precondition for concessional loans from bilateral/ multilateral agencies to the borrowing entities. Government Guarantee should, however, not be used to obtain finance through state owned entities as a substitute for the budgetary resources of the State Government. Government Guarantees should not be allowed for creating direct liability/de-facto liability on the state. State Government Guarantees: Current Status and Way Forward 3.1 State Government finances, already constrained by COVID-19 pandemic, have been facing new sources of risks in the form of rising expenditure on non-essential heads, expanding contingent liabilities, and the ballooning overdues of DISCOMs. Fiscal risks can arise from macroeconomic shocks on crystallisation of the contingent liabilities which can either be ‘explicit’, viz., government loan guarantees, or ‘implicit’, wherein even without any specific guarantee, there is widespread public expectation that the Government would rescue or bailout the troubled entities (Mukherjee et. al., 2022). 3.2 RBI has, in the past, examined the implications of states’ contingent liabilities/ guarantees on their finances (Box II). RBI also played an active role in designing ‘Model Fiscal Responsibility Legislation’ for the states, which paved the way for the introduction of fiscal rules by some of the State Governments under their respective FRBM Acts. Several of these initiatives were the outcome of discussion held at the interactive platform provided by the RBI in the form of annual Conference of State Finance Secretaries. 3.3 RBI, in its role as the cash and debt manager of the states, keeps sensitising them on various issues of concern that have a bearing on their finances. The genesis of concern with respect to guarantees dates back to late 1990s when their issuances rose substantially in the wake of the poor fiscal position of some of the states which hampered the provision of direct financial support to the state PSUs (RBI, 1999). RBI constituted a Technical Committee on State Government Guarantees (1999) to examine all aspects relating to State Government guarantees. The Committee stipulated a ceiling on the guarantees and recommended setting up of GRF to provide a cushion to service contingent liability arising from invocation of guarantees. As per the scheme introduced by RBI in 2001, the states had to contribute an amount equal to one-fifth of the incremental guarantees issued during the year. Accordingly, several State Governments stipulated a ceiling on their guarantees and set up GRFs.

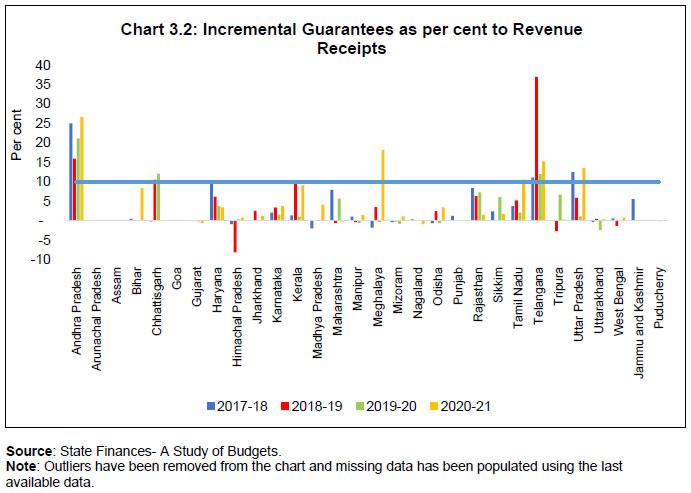

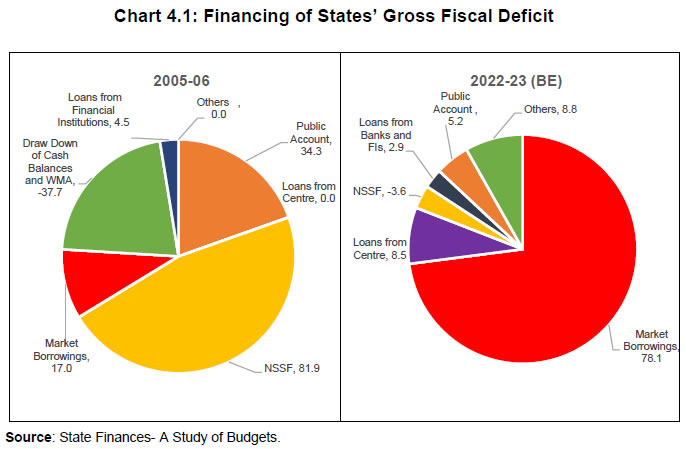

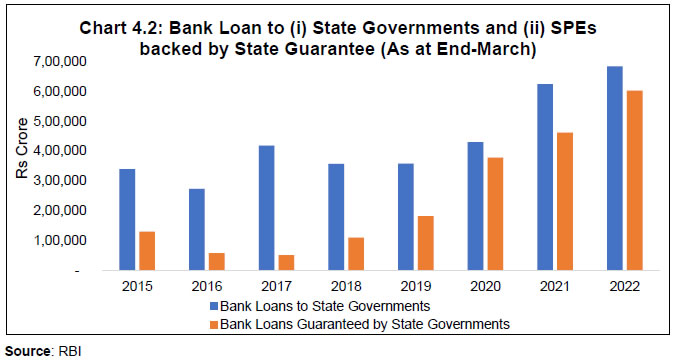

Recommendations made by Previous Committees: Implementation Status 3.4 Following the recommendations of the above Committees/ Groups, states have taken action such as fixing explicit ceiling on guarantees, setting up buffer funds such as CSF/GRF, introduction of levying of guarantee fee, disclosure of total outstanding guarantees, risk categorization of guarantees, etc. A brief on the implementation status of the recommendations made by the previous Committees/Groups is as under: Disclosure of Information 3.5 Data on outstanding guarantee is being published by most of the states. States that have made disclosure of guarantees mandatory under their FRBM rules, publish it as part of budget documents. Further, some states have been publishing guarantee related data even though it is not made mandatory under their FRBM rules. A few states also publish data on risk weighted guarantees. The other details such as sector / project wise outstanding / issued during the year, invoked during the year, once invoked whether paid, etc., however, are being disclosed by a few states only. The format being used for reporting the data on guarantees, however, lacks uniformity, thereby, rendering it difficult for a meaningful comparison amongst the states (Annex III). 3.6 RBI’s annual publication, “State Finance: A Study of Budgets” publishes data sourced from individual states on state-wise total outstanding guarantees. The data, however, provides little information on the coverage or type of guarantees, sectors to which the guarantees have been given, etc. As a result, the data on guarantees published in RBI publication may have limited usage for various stakeholders, such as the Governments, regulators, investors/ lenders, researchers, etc. 3.7 For the sake of transparency and quality, it is recommended that data on the total amount of guarantees extended during the year, outstanding guarantees at the end of the year, guarantees invoked during the year, etc. is disclosed by the states in their annual budget documents, as per the IGAS (Annex I) recommended by Government of India (GoI, 2010), which can also be used by CAG for their audit and by RBI for its annual publication “State Finances: A Study of Budgets”7. RBI may also explore the feasibility of sharing of information on the amount of credit, backed by State Government guarantees, extended to state owned / backed entities by the banks and NBFCs, with the CAG. Fixing the Ceiling for Guarantee 3.8 A look at the state-wise guarantee data for the period 2018-21 suggests that outstanding guarantees constituted less than 10 per cent of their GSDP for majority of the states. It has, however, been rising over the years for most of the states (Chart 3.1).  3.9 Guarantees, as and when, invoked may lead to significant fiscal stress on the State Governments. States are, therefore, expected to exercise prudence and selectivity while extending guarantees. Though most of the states are in different stages of development with diverse resource availability in terms of GSDP, own tax and non-tax revenue, central transfers, etc., it is desirable for the State Governments to consider fixing a ceiling on guarantees issued. Such a ceiling should have clarity, transparency, sanctity and operational relevance and should be backed by legislative statute. 3.10 It is observed that some of the states have put statutory ceilings on quantum of guarantees, while some others have imposed ceilings through administrative orders. The Group notes that the extant ceilings fixed by the states lacked uniformity, e.g., some states have fixed their ceilings on annual incremental guarantees to be issued, some have ceilings fixed in terms of annual incremental risk weighed guarantees, while a few others have fixed in terms of total outstanding guarantees. There is also lack of uniformity in terms of variable(s) to which these ceilings are linked, viz. certain percentage of either total revenue receipts or GSDP. The Group suggests linking of incremental guarantees to be issued during the year to Revenue Receipts (RR) and GSDP. 3.11 It is observed that during the period 2017-21, the amount of incremental guarantees issued in a year has remained below 10 per cent of their RR for majority of the states (Chart 3.2). Recognising the risks associated with the burgeoning guarantees on the fiscal health of the states, the Group proposes a ceiling for incremental guarantees issued during a year at 5 per cent of RR or 0.5 per cent of GSDP, whichever is less8.  Assigning Risk Weight 3.12 State Governments have been issuing guarantees on behalf of state public enterprises belonging to various sectors viz. power, co-operative, agriculture, transport, water supply, sanitation, housing, communication, industries, etc. The probability of default could vary across sectors, depending on the financial parameters of the sector and varying impact of macroeconomic shock. Therefore, reporting only the nominal value of guarantees may not present the true picture of the risk that the State Government would be exposed to. States should classify the projects/ activities as high risk, medium risk and low risk and assign appropriate risk weights before extending guarantees (RBI, 2002). Many states have started releasing information on risk weighted guarantees. It is also observed that some of the states are assigning risk weights that are much lower than 100 per cent, thereby, under-reporting the amount of guarantees issued. The Group recommends that the minimum risk weight for any guarantee extended by the State Government should be kept at 100 per cent. Additionally, states should disclose their methodology for assigning the risk weights9. 3.13 In the past, there have been a few instances of state guarantees not being honoured when invoked. The Group recommends that any risk categorisation should also take into consideration past record of defaults. Guarantee Fee 3.14 Funds collected through guarantee fees should be used to create and build the GRF. Additionally, the fee should be structured in a manner that it acts as a deterrent in seeking guarantees for the riskier projects. A minimum of 0.25 per cent per annum may be considered as the base or minimum guarantee fee and additional risk premium, based on risk assessment by the State Government, maybe charged to each risk category of issuances. The Guarantee fee should also be linked to the tenor of the underlying loan10. Setting up of GRF 3.15 The objective of the GRF is to provide a cushion for servicing contingent liabilities arising from the invocation of guarantees issued by the State Governments in respect of bonds and other borrowings by state level undertakings or other bodies. Though the participation from the states in GRF is voluntary, 19 states have already established GRF. The GRF corpus managed by RBI stood at Rs. 10,839 crore as on March 31, 2023 (Table 3.1). 3.16 States are financing their fiscal deficit largely through market borrowings. The funds parked in the GRF are invested in eligible Government securities. The states which are yet to become members of GRF and the states which are members but have not been regularly contributing to the fund, often cite the negative ‘carry’ on such contributions, i.e., the cost of raising fund is usually higher than the return generated by the fund. Considering the importance of GRF in providing cushion to the states’ fiscal health and in order to make the fund attractive for the states, RBI has permitted the member states to avail short-term collateralised funding from RBI at a concessional rate (currently at 200 bps below the prevailing Repo Rate) under the Special Drawing Facility (SDF) against their investment in the Fund. This helps the states in bringing down their overall cost of borrowing. RBI has also set up a separate Working Group on CSF/GRF to look into the operational challenges faced by the states in becoming member of the GRF and in making contributions to the fund. 3.17 The advantages of having access to GRF at the time of contingency outweigh the disadvantages. The investment by the State Governments in GRF has ranged between 1.1 and 1.6 per cent of the outstanding guarantees during the period 2016 to 2021 (Table 3.2). As the quantum of outstanding guarantees now compares sizably to the state’s existing debt stock (Khandelwal, 2022), there is merit in increasing the size of the corpus of GRF by the member states. States should, therefore, continue to build up the GRF to a desirable level of five per cent of their total outstanding guarantees. 3.18 States need to develop ways to safeguard against risks associated with contingent liabilities by being prudent in issuing, monitoring/ managing and transparent about the existing guarantees. States have implemented some of the recommendations made by the various Committees/ Working Groups. A lot of work, however, still needs to be done in order to contain the risks emanating from guarantees. Bank Financing to State Enterprises 4.1 The state deficits are financed by various sources, viz. loans from centre, NSSF, market borrowing, loans from bank and financial institutions, public account, draw down of cash balances, etc. The financing pattern of states’ fiscal deficit has evolved over the years driven by the changing macroeconomic conditions and introduction of new policies. While NSSF remained the major source of financing GFD during 2004-05 to 2010-11, its share has declined thereafter. In recent years, market borrowing has become the major source of financing GFD (Chart 4.1).  4.2 The share of banks and financial institutions in financing states’ GFD has remained low in comparison to other sources. Nevertheless, the total quantum of borrowing by the states from the banks has shown an increasing trend over the years. Simultaneously, the loans extended by the banks to the state enterprises backed by government guarantees have also been growing (Chart 4.2).  4.3 Under Credit Authorisation Scheme (RBI, 1969) banks were allowed to grant advances to the Electricity Boards and Public Sector Undertakings, and against the guarantee of the Central Government and State Governments without prior authorization of RBI. 4.4 In May 1979, banks were prohibited from providing finance in the form of direct loans for construction of infrastructure facilities like construction of public roads, bridges, harbours, dams, etc. the cost of which was expected to be met out of budgetary resources of the Government. 4.5 With the changes in the overall policy environment when Government started permitting private entrepreneurs to take up projects involving creation of infrastructure facilities, RBI allowed banks to provide term loans for creation of infrastructural facilities to entrepreneurs/private sector undertakings which undertook Government projects without the support of budgetary allocations (RBI, 1992). In cases where the infrastructural facilities were being created out of budgetary allocations, banks were not allowed to finance the same. 4.6 Subsequently, banks were allowed to finance public sector undertakings also for creation / expansion/ modernization of infrastructure facilities subject to the condition, inter-alia, that the public sector undertaking was run on commercial lines and the repayment of the term finance was made out of income to be generated by the project and not out of subsidies made available to it by the Government and the project was technically feasible, financially viable and bankable (RBI, 1994). Banks were strictly prohibited from financing projects funded out of budgetary resources, or where a firm commitment for such budgetary support had been made and was in operation. 4.7 In 1995, RBI issued regulations clarifying that banks could fund housing projects not forming part of infrastructure but operated on commercial lines only if Government was interested in promoting the project and in which part of the project cost was met by the Government through subsidies made available and/or contributions to the capital of the institutions taking up the projects (RBI, 1995). Banks were advised to restrict the financing to an amount arrived at after reducing from the total project cost the amount of subsidy/capital contribution receivable from the Government and any other resources proposed to be made available by the Government. The banks were also advised to ensure commercial viability and that the repayment of the loan was made from the business income of the borrowing corporation/ firm/ individual. 4.8 PSEs were getting a separate share of market borrowing (SLR linked) till 1993-94 (RBI, 1999). They were also getting substantial amount of budgetary support for their capital requirement. Once separate allocation of market borrowing for PSEs stopped in 1994-95, the utilities and other PSEs, turned to banks and financial institutions for meeting their financing requirements. The growing need for infrastructure at the state level and the participation by the private sector in such projects required huge investments which put pressure on State Governments to stand guarantor for such projects. 4.9 Some of the conditions stipulated by RBI for financing of infrastructure and housing projects are as under:

4.10 Banks are usually not permitted to extend bridge loans against amounts receivable from central/ State Governments by way of subsidies, refunds, reimbursements, capital contributions, etc. 4.11 State Governments often issue guarantees on behalf of various PSEs/ Co-operative Institutions / Urban Local Bodies, etc. to various banks / financial institutions for financing developmental schemes / projects. Often, a Government guarantee makes it easier for such entities to obtain a commercial loan at favorable terms. These contingent liabilities are a risk to State Governments owing to the large outstanding debt and losses of PSEs. Following is an indicative list of cases involving guarantees as credit enhancement tool/collateral -

4.12 With the increase in lending to State PSEs, obtaining State Government guarantees became a norm for the banks. To address the growing risk to the banking system on account of increasing banking sector exposure to state owned entities backed by State Government guarantee, banks were advised by RBI not to compromise on proper credit appraisal and to ensure close monitoring of the intrinsically viable projects that were financed. 4.13 An RBI regulated entity is allowed to reckon a State Government guarantee received on behalf of a borrower as an instrument of credit risk mitigation. Exposures backed by State Government guarantees also enjoy the benefit of concessional risk weight for the purpose of assessing their capital adequacy. When State Government guarantee is used as a credit risk mitigant, the risk exposure shifts to the State Government. 4.14 Generally, Government owned NBFCs have exposure to claims guaranteed by State Government. When banks lend to such NBFCs, it indirectly exposes them to the claims guaranteed by the State Governments. 4.15 The Group is informed that there have been instances where banks have not strictly complied with the extant RBI guidelines on assessment of commercial viability, ascertainment of revenue streams for debt servicing obligations and monitoring of end-use of funds while financing infrastructure/ housing projects of government owned entities. Though the extant guidelines for the banks have been reiterated by RBI on June 14, 2022, the Group is of the view that apart from the lending financial institutions, it is also in the interest of the respective State Governments to ensure that the repayment/ servicing of such debt is not done out of their budgetary resources. Recommendations 5.1 Guarantees or contingent liabilities are potential liabilities that depend on the occurring of an unforeseen future event. If these liabilities are realised without having adequate buffer, it may imply increase in expenditure, deficit and debt levels for the State Government. It is, therefore, important to assess, monitor and be prudent while issuing guarantees. Besides, State Governments need to be consistent and transparent in terms of disclosure of information on guarantees. 5.2 In pursuance of the guidelines suggested by the various Committees set up under the aegis of RBI and the State Finance Secretaries (SFS) Conference, most of the states have adopted risk mitigation measures which, inter alia, include fixing ceiling on guarantees, setting up of reserve funds, i.e., CSF/ GRF, levying guarantee fee, publishing information relating to total outstanding guarantee, risk categorization of the guarantees, etc. It is, however, observed that all the states have not implemented these measures. Also, there is lack of uniformity amongst states while putting in place these measures. Recommendations 5.3 The Working Group makes the following recommendations: Definition of Guarantees 5.4 There should not be any distinction made between Conditional/ Unconditional, Financial/ Performance guarantees as far as assessment of fiscal risk is concerned as all of these are in the nature of contingent liability that might get crystallized on a future date. 5.5 The word ‘Guarantee’ should be used in a broader sense and may include instruments, by whatever name they are called, if these create obligation on the part of the Guarantor (State) for making payment on behalf of the borrower (State Enterprise) at a future date, contingent or otherwise. Guidelines for Guarantee Policy 5.6 State Governments may be guided by the guidelines issued by the Government of India (GoI, 2022) while formulating their own Guarantee policy:

5.7 Purpose for which Government Guarantees may be issued, should be clearly defined in line with Rule 276 of General Financial Rules, 2017 (GoI, 2017), to ensure the financial viability of projects or activities undertaken by Government entities with significant social and economic benefits; to enable state public sector entities to raise resources at lower interest charges or on more favourable terms; to fulfil the requirement in cases where state guarantee is a precondition for concessional loans from bilateral/ multilateral agencies to the borrowing entities. Government Guarantees should, however, not be used to obtain finance through State owned entities, which substitutes budgetary resources of the State Government. Government Guarantees should not be allowed for creating direct liability /de-facto liability on the state. Risk Categorization 5.8 The Group suggests that the states should classify the projects/ activities as high risk, medium risk and low risk and assign appropriate risk weights before extending guarantees (RBI, 2002). Such risk categorisation should also take into consideration past record of defaults. The states should conservatively keep the lowest slab of risk weight at 100 per cent. Additionally, states should disclose their methodology for assigning the risk weights. Ceiling on Guarantees 5.9 A reasonable ceiling on issuance of guarantees may be desirable, as their invocation could lead to significant fiscal stress on the State Governments. The Group recommends a ceiling for incremental guarantees issued during a year at 5 per cent of Revenue Receipts or 0.5 per cent of GSDP, whichever is less. 5.10 Nominal value of guarantees as compared to their risk-weighted value may be used for arriving at the ceiling linked to total revenue receipt or GSDP, as the case may be. Guarantee Fee 5.11 The guarantee fee charged should reflect the riskiness of the borrowers / projects / activities. A minimum of 0.25 per cent per annum may be considered as the base or minimum guarantee fee and additional risk premium, based on risk assessment by the State Government, may be charged to each risk category of issuances. The Guarantee fee should also be linked to the tenor of the underlying loan. Reserve Fund 5.12 Apart from serving the purpose for which it is constituted, maintaining GRF with RBI is advantageous for the states as they are entitled to avail short-term funds from RBI under SDF at a concessional rate for meeting temporary mismatches in their cash flows. The Group, therefore, recommends that the States which are currently not members of the GRF should consider becoming members at the earliest. 5.13 States should continue with their contributions towards building up the GRF to a desirable level of five per cent of their total outstanding guarantees over a period of five years from the date of constitution of the fund. The corpus may be maintained on a rolling basis thereafter. Administrative and Institutional Mechanism for Monitoring 5.14 State Governments may insist on the state undertakings, whose borrowings are guaranteed to set up an arrangement for provisions for meeting possible shortfalls in project earnings. The borrowing state enterprises should set up escrow accounts with predetermined and regular contributions from project earnings (RBI, 1999 and RBI, 2002). In case revenue of the project suffers for any reason, repayments could be made out of these accounts before resorting to State Government guarantees. 5.15 To develop a proper database for capturing all guarantees extended by the State Government, a unit responsible for tracking all the guarantees may be designated at the state level (preferably, within the Department of Finance) (RBI, 2002). The unit thus created would act as a Monitoring Unit (MU) and would be responsible for compilation, consolidation, maintenance of the database on guarantees and monitoring the same on a continuous basis. Disclosure Standards 5.16 Transparency and disclosure are crucial to enhance market discipline. In order to ensure uniformity and consistency in data being reported, the State Governments may publish/ disclose data relating to guarantees, as per the IGAS (Annex I) recommended by Government of India (GoI, 2010), which can also be used by CAG for their audit and by RBI for its annual publication ‘State Finances: A Study of Budgets’. 5.17 Availability of guarantees data both from the issuers’ side (i.e., State Governments) as well as from the side of the lenders/ investors may improve the credibility of the data being reported/ published by the State Government. RBI may consider advising the banks/ NBFCs to disclose the credit extended to state owned entities, backed by State Government guarantees. Honouring of Guarantees 5.18 The delay in honouring guaranteed obligations, may affect the sanctity of guarantees issued, which may result in reputational risk and legal risk for the state Government (RBI, 1999). Banks and financial institutions may be wary of extending any fresh finance to any state enterprise if the state has failed in honouring its guarantee commitments. Also, fresh guarantees issued by the State Government may not be readily accepted by the lenders/investors. It is, therefore, in the interest of the State Governments to ensure that all guarantees in respect of loans and bonds, when there is a default, are honoured without delay. Cebotari, Aliona (2008), “Contingent Liabilities: Issues and Practice”, WP/08/245, IMF Working Paper, October 2008, International Monetary Fund. Government Accounting Standards Advisory Board (2015), Indian Government Financial Reporting Standard (IGFRS) 5. Contingent Liabilities (other than guarantees) and Contingent Assets: Disclosure Requirements, Fourteenth Finance Commission (2015-20), Volume I & II: Report, February, India Government of India (2004), “Twelfth Finance Commission (2005-10)”, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, 2004. Government of India (2010), “Guarantees given by Governments: Disclosure Requirements”, Ministry of Finance, Notification, New Delhi, December 20, 2010, https://rbi.org.in/documents/87730/39016390/Guarantees_DisclReq_1.pdf. Government of India (2017), “General Financial Rules 2017”, Department of Expenditure, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, February 11, 2017, https://rbi.org.in/documents/87730/39016390/GFR2017_0.pdf. Government of India (2022), “Government Guarantee Policy”, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, Budget Division, New Delhi, May, 2022 Khandelwal, Aayushi, Rachit Solanki, Saksham Sood, Ipsita Padhi, Anoop K Suresh, Samir Ranjan Behera and Atri Mukherjee (2022), “Government Finances 2022-23: A Half-Yearly Review”, RBI Bulletin, Dec 20, 2022. Lu, Jason Zhengrong, Jenny Jing Chao, and James Robert Sheppard (2019), “Government Guarantees for Mobilizing Private Investment in Infrastructure”, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Mukherjee Atri, Samir Ranjan Behera, Somnath Sharma, Bichitrananda Seth, Rahul Agarwal, Rachit Solanki and Aayushi Khandelwal (2022), “State Finances: A Risk Analysis”, RBI Bulletin, June 16, 2022. Razlog, Lilia, Tim Irwin, Chris Marrison (2020), “A Framework for Managing Government Guarantees”, Discussion Paper, MTI Global Practice, No. 20, May 2020, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Saxena, Sandeep (2017), “How to Strengthen the Management of Government Guarantees”, Fiscal Affairs Department, October 2017, International Monetary Fund. Reserve Bank of India (1969), “Credit Authorisation Scheme”, DBOD.No.CAS.969/C.446-69 dated May 12, 1969. Reserve Bank of India (1979), “Housing Finance”, DBOD.No.CAS.BC.71/C.446(HF-P)-79, dated May 31, 1979. Reserve Bank of India (1992), “Financing of Projects involving Creation/ Modernisation/ Expansion of Infrastructural facilities”, IECD.No.11/08.12.01/92-93 dated December 10, 1992. Reserve Bank of India (1994), “Financing of Projects involving Creation/Expansion/ Modernisation of Infrastructural facilities”, IECD.No.15/08.12.01/94-95 dated October 06, 1994. Reserve Bank of India (1995), “Sanction of Term Loans for Housing Projects involving Budgetary Support from Government – Non-permissibility of”, IECD.No.CMD.8/03.27.25/95-96 dated September 27, 1995. Reserve Bank of India (1999) “Report of the Technical Committee on State Government Guarantees”, April 07, 1999. Reserve Bank of India (2001) “Report of the Core Group on Voluntary Disclosure Norms for State Governments”, January 12, 2001. Reserve Bank of India (2002) “Report of the Group to Assess the Fiscal Risk of State Government Guarantees”, July 2002. Reserve Bank of India (2003) “Working Group on Information on State Government Guaranteed Advances and Bonds”, October 2003. Reserve Bank of India (2005) “Working Group on Compilation of State Government Liabilities”, October 2005. Reserve Bank of India (2006) “Advisory Panel on Transparency Standards under the Financial Sector Assessment Programme”, October 2006. Reserve Bank of India (2022), “Bank Finance to Government Owned entities”, June 14, 2022.

Recommendations of Previous Committees/ Groups Technical Committee on State Government Guarantees (1999) Ceiling on guarantees In the interest of ensuring fiscal sustainability and ensuring more discrimination and selectivity in the matter of taking and giving of guarantees, it will be desirable for State Governments to fix a ceiling on guarantees and such a ceiling will have transparency, sanctity and operational relevance only if legislated, as explicitly enabled in the Constitution of India. This is being practised already in some States where an overall ceiling on guarantees is legislated, and such ceilings are changed by legislative amendments. Parameters and basis for the ceiling on Guarantees There could be four parameters that could be used for fixing the ceiling on guarantees. (a) One approach is to link guarantees to a dynamic variable such as NSDP. Total outstanding debt plus one-third of outstanding guarantees should not exceed, say, 50 per cent of the NSDP. A modification of this parameter is suggested for those States, where guarantees have been used to raise resources for infrastructure, so as to give equal weight to guarantees and debt, for guarantees issued since 1994-95. (b) The second approach is based on the argument that the NSDP is not a parameter that is within the ambit of the budgetary management of the State governments and it is more appropriate to link guarantees to revenue receipts. Refining this approach further, each State Government could work out the flexible cash available with it each year after deducting the obligatory expenditure such as salary, pension, amortisation and interest payments from the Central tax devolution, States own tax revenues and non-tax revenues. Depending on the maturity pattern and nature of the loans guaranteed and using the same equation of debt to guarantee as under the first parameter, the likely outflows on account of guarantees, letter of comfort, tripartite payment agreements, escrow accounts etc., could be worked out and then related to the coverage available against the flexible cash flow. A coverage of 10:1 should be maintained over the period of the loans/guarantee. The net present value concept could be incorporated in this approach. (c) The third approach is to link the guarantees and debt to the consolidated fund itself. Thus, the parameter would be that guarantees plus debt together do not exceed twice the receipts in the consolidated fund. (d) The fourth approach is to ensure that the ratio of incremental guarantees to incremental net market borrowings is kept constant or brought down There should be sufficient flexibility to each State Government to choose the most appropriate parameter while ensuring transparency in respect of all the parameters. While each state may legislate on the ceiling on guarantees, it should have the freedom to choose any of the parameters listed above to serve as the basis for fixing the ceiling. Simultaneously, there is advantage in reporting to the legislature the extant position in terms of each of the four parameters. Selectivity in calling for and providing of guarantees The proposal for prescribing a ceiling on guarantees is practical only if there is more selectivity in the calling for of and in the providing of guarantees. Such selectivity can be practised, inter alia, in the following ways: (a) Each State may lay down the procedures to be followed in case of projects or units where State guarantee is involved, identifying a nodal officer in the Finance department, who could co-ordinate the proposals involving guarantees. It will also be in the interest of banks and financial institutions to involve the Finance Departments in any financial arrangement involving the provision of guarantee by State Governments. (b) Some degree of risk sharing between the lenders/investors, borrowers and State Government is desirable in the interest of ensuring efficient utilisation of funds and financial discipline. Instead of State Governments providing guarantee for 100 per cent of the loan/bond, guarantee could be restricted to 75 per cent to start with and adjusted suitably depending upon the project with the concurrence of the investor/lender. (c) States may give immediate attention to finalisation of the audited accounts of State public sector enterprises in order to minimise the cases where guarantees are required. (d) Where State level housing and urban development agencies do not have clear title for the immovable properties owned /held by them, the States could explore the possibility of creating a deed of transfer similar to that executed by the Government of Tamil Nadu, to obviate the need for guarantees especially in favour of HUDCO and LIC for housing loans and for loans to develop urban property especially for commercial purposes. (e) In the interest of ensuring better selectivity in the matter of giving guarantees, NABARD, the finance and the co-operation department of the State Government should together formulate a plan based on historical default at various levels, to minimise the need for provision of guarantees. The possibility of introducing a system of ‘risk sharing’ between the State Government, NABARD and the co-operatives bank could also be considered. (f) Amendment to the NCDC Act, removing the mandatory requirement of guarantee, may be expedited. In sanctioning loans, NCDC could be governed more by the viability of the project assisted and the financial position of the co-operative assisted so that the need for guarantee is automatically obviated. As in the case of NABARD, introduction of a system of risk sharing could be thought of. (g) The reasons for asking for guarantee could be given in writing by the banks and financial institutions to the Finance Secretary, who could either justify the intrinsic viability or take steps to improve the viability. (h) Even for non-commercial projects requiring guarantees, States will need to evolve arrangements for increasing the stake in such projects by each of the stake holders viz., the beneficiaries, the Government and the financial institutions. (i) In case of infrastructure projects there could be greater selectivity in the matter of calling for and providing of guarantees. Where guarantees are given for infrastructure projects, there should be some accountability for implementation and milestones could be drawn up for monitoring. The availability of guarantee must not lead to a feeling that the bonds/ borrowings backed by such guarantee do not have to be serviced by the project itself. (j) At present, once guarantees are given, there is no review as to whether they need to be continued if the project has attained viability. States could consider phasing out of guarantees in concurrence with financing agencies/rating agencies/trustee on behalf of bond holders as and when the projects achieve viability. To reach this objective, milestones could be specified for each project which could be monitored; on reaching the milestone, the guarantee could be phased out or extent of risk covered by the guarantee reduced. Honouring of Guarantees It is in the interest of State Governments to ensure that all guarantees in respect of loans and bonds are immediately honoured whenever there is default. The manner in which the States handle the issue of default in honouring of guarantees will play a very important role in ensuring the success of their market borrowing programme. If necessary, as has been done by some States, RBI could be authorised to earmark or pre-empt a portion of the new loans towards the arrears in payment of interest and principal on loans and bonds. Alternatively, special bonds could be issued to banks and financial institutions in lieu of the accumulated arrears of payment due from State governments under invoked guarantees. Each bond issued could be limited to the specific amount of guarantees invoked by the bank/financial institution concerned, based on market- related interest rate so that such bonds could be also traded in the secondary market. Both these measures should be viewed as exceptional one-time measures so as to avoid moral hazard. Letter of Comfort As there is an implicit liability arising out of a letter of comfort and there is a need to contain contingent liabilities devolving upon it, State government may eschew the practice of providing letters of comforts and where letter of comfort from State government is required, credit enhancement may be provided through explicit guarantees within the overall limit fixed for the purpose. As regards letters of comfort provided in past, full details may be disclosed in the budget documents and may be included in reckoning the ceiling on guarantees. Disclosure transparency and reporting of guarantees Comprehensive information on guarantees as also letters of comfort wherever issued should be disclosed by the State governments in the major budget document i.e., Budget at a Glance on as contemporaneous a basis as possible. The proposal for ceiling on guarantees using whichever parameter the State government feels is appropriate for it, should be brought to the legislature before the next year’s budget formulation exercise say, by September, so that the ceiling can be debated and legislated upon. Tripartite Structured Payment Arrangements Structured payment arrangements provide mechanisms for assured payment by State Governments even where there is no guarantee whereas under guarantees issued by the State governments there is no such mechanism. Such arrangements should be discouraged as the financing decision is then not based on the intrinsic viability of the project but the availability of such assured payment arrangement. Simultaneous with prescribing a ceiling on guarantees and ensuring selectivity in issuing guarantees, such structured payments should be included in the guarantees reported and subject to the limits fixed by the States. Escrow mechanisms for IPP State governments should encourage the State Electricity Boards to build up a risk fund to handle the contingent liability on account of exchange risk under escrow account arrangements provided to IPPs. Along with disclosure of guarantees, States should also disclose the revalued liabilities of the State Electricity Boards under IPPs or similar arrangements for other utilities. Standardisation of documentation Standardisation of guarantee documents though desirable would be difficult. Each State government could however evolve its own standard documentation for guarantees. Guarantee fee and constitution of a Contingency Fund for guarantees Normally, the guarantee fee should be so structured that the receipts from such fees will take care of the devolvement. Guarantee fees should be invariably charged, appropriately calculated and properly accounted for. The charging of guarantee fee should be rationalised and each State should set up a contingency fund or make some provision for discharging the devolvement under guarantees. The fees collected should be credited to the fund set up for the purpose. Monitoring of Guarantees As part of exercises leading to budget, Committee recommends that guarantees given by State governments may be made a regular item of discussion during the annual plan discussion, specifically at the stage of resource mobilisation exercise. Implicit Contingent Liabilities In line with the trend towards consolidated presentation of accounts, the Committee recommends that a summary of the financial statements of 100 per cent State-owned corporations may form part of the notes relating to budgets of the State governments. Core Group on Voluntary Disclosure Norms for State Governments (2001) The States which have already started publishing “Budget at a Glance” may be persuaded to disseminate more information on a time series basis, especially data on major fiscal indicators viz., revenue deficit, primary deficit, tax revenue, interest payments, subsidies, contingent liabilities including guarantees etc. Other States are encouraged to initiate necessary steps towards publishing “Budget at a Glance” and also some of the time series data on a few fiscal indicators as mentioned above. Since these State Governments have some time left with them for preparation of the Annual Budget 2001-02, there is a scope for attempting this suggestion. In the medium term, States are encouraged to move towards publishing ‘Budget Summary’ as given in Annexure –3. The Group fully agreed that although there may be some gaps in the initial stage, States are encouraged to make improvement in the subsequent years, once they gain enough expertise. Some of the major States, which have necessary skills, may move towards publishing the suggested Budget Summary as early as possible. This could help other States in emulating the practice. The State Finance Secretaries Forum may assess the progress under this sphere after a period of two years so as to chalk out further programme of action. It is important to mention that the suggested format (Budget Summary) could be considered as an ultimate goal of State Governments in the transparency practices with regard to budget exercise. Availability of high frequency data in the website is the order of the day. State Governments are encouraged to use this opportunity so that they can develop their own website and start publishing the data in this website. At a later point of time this would also provide an opportunity for them to move towards high frequency data viz., monthly, quarterly or half yearly. Publishing high frequency data would help the authorities in assessing the performance and to plan for the future. Group to Assess the Fiscal Risk of State Government Guarantees (2002) The Group noted the developments in the management of guarantees by states vis-à-vis the recommendations of the Technical Committee. Seven states (Assam, Goa, Gujarat, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Sikkim, West Bengal) have in place either an administrative or statutory limit on guarantees with two more states (Kerala and Tamil Nadu) in the process of fixing a ceiling. On the issue of transparency, the Group was of the view that the states need to publish data regarding guarantees regularly, in the format recommended by the Group of Finance Secretaries in the annual budget. To further improve transparency, it is recommended that both the annual sanctions of guarantees and outstanding amount need to be disclosed in the state budget. Further, in order that a proper database is created for capturing all guarantees, a Tracking Unit for guarantees may be designated (in the Ministry of Finance) at the state level. In the interest of financial stability and transparency, in addition, states may disclose the information on default, invocation and payment performance. The Group noticed the continuously rising trend of outstanding guarantees which grew at an average rate of about 16 per cent per annum during the period 1992-2001. In terms of sectoral distribution, the power sector at 44.6 per cent was the largest constituent of outstanding guarantees. As for beneficiaries, banks at about 15 per cent and all-India financial institutions at about 25 per cent were significant as an investor class. Although financial institutions are increasingly becoming conscious about the importance of proper risk assessment of projects, some institutions continue to insist on guarantees, either because it is mandated in the Acts governing them or as a conscious policy. The Group studied such Act provisions/policies of major institutions and recommended that the need for extending guarantees in favour of central financing agencies owned by Government should be examined and even done away with. It is essential that the lending institution should undertake due diligence and examine the commercial viability of the project instead of relying on State government guarantee. Insistence on viability of projects and generation of adequate repayment capacity will push through reforms in the area of levying user charges and removal of subsidies so essential in the reform process. The Group also recommended that where guarantee is taken as credit enhancement, it should be reflected in reduction in the lending rate. The Group studied the methodology for assessing fiscal risk of guarantee obligations prevailing internationally. While it recognized the importance of classifying guarantees in terms of their default probabilities, it concluded that in the Indian context this methodology would not accurately reflect the fiscal risk in guarantees. It suggested the following methodology: a. One of the first steps in assessing the fiscal risk of guarantees is to clearly segregate those which are effectively in the nature of direct liabilities and report these separately and assess the risk of such guarantees at 100% viz. as equal to debt. Such guarantees should be clubbed with debt while assessing the debt profile of the State for all purposes. A large number of guarantees fell in this category. It was noted by the Group that the Ministry of Finance, Government of India has already adopted a similar approach in the discussions under the Medium Term Fiscal Reforms Programme. For such guarantees, which are more like debt, it is apparent that the repayment provision should be made in the budget itself. Ministry of Finance, Government of India, will have to assess this while finalising the Plan and borrowing programme of the State. b. For the rest of the guarantees, measuring the fiscal risk is necessary. This would involve further classification of the projects/ activities as high risk, medium risk, low risk and very low risk and assigning appropriate risk weights. The assessment of risk will be done at the State level. For making such assessment there are various options that can be adopted by the States. Making use of credit rating of bonds is one option. Government of India has already instructed that all bonds issued in future with government guarantee will have to be compulsorily credit rated. While reiterating the importance of compulsory credit rating, it should be kept in mind that invariably the rating is enhanced because of the availability of guarantee or some structured payment mechanism. State Governments should, in such cases, assess the risk sans guarantee with the assistance of rating agencies. It is therefore necessary that for all such guaranteed bonds, a dual rating, with and without guarantee, should be obtained. The rating, without taking into account guarantee, could then be used for purposes of classifying into high risk, medium risk, low risk and very low risk. In respect of existing loans and bonds a similar exercise can be undertaken by the State Finance Departments. c. Once the guarantees have been categorized into Very Low, Low, Medium and High-risk categories, the finance departments of states will have to use their judgement to assign devolvement probability to each risk category, say 5% for very low risk, 25% for low risk, 50% for medium risk and 75% for high risk. The translation of risk assessment to devolvement probability is essentially a matter of judgement and is best left to individual States. The devolvement probability could then be applied to the underlying liabilities which are guaranteed to estimate the guarantee devolvement obligation, which could then be added to debt service obligation to arrive at the annual fiscal burden of debt and guarantees. d. The guarantee commissions charged by States do not bear much relation to the underlying risk and may not be sufficient to constitute the Guarantee Redemption Fund (GRF). Secondly, it is infeasible at the present stage to increase guarantee commission as most bodies in favour of whom guarantees are extended are also in the public sector. Therefore, the Group recommends that at least an amount equal to 1 per cent of outstanding guarantees may be transferred to the GRF each year from the fisc specifically, to meet the additional fiscal risk arising on account of guarantees. The guarantee commission collected could also be credited to this Fund. e. The Group felt that increasing the existing rates of guarantee commission may not be practical as the projects will not be able to bear additional guarantees, although merit was seen in linking guarantee fee to the category of risk. It can be left to each state to decide whether it would like to charge guarantee fee according to risk category. f. As per the 11th Finance Commission, States should aim to limit interest payments to 18% of revenue receipts in the medium term. This norm could be modified to include possible devolvement on account of guarantee obligations of the states on the basis of the methodology indicated above, and the total obligation should not exceed 20% of revenue receipts. This will automatically serve as one measure for capping guarantees. Many states may have currently debt service plus guarantee obligation in excess of 20%. In their cases it is imperative to place limits on incremental guarantees in any year in relation to revenue receipts. g. In order to have a norm in terms of debt sustainability the underlying guarantee liabilities can be mapped out and likely amount of devolvement could be estimated for future years. The total of such likely devolvement during the life of the guarantees could then be treated as normal debt and clubbed together with debt obligations. Together, the liability could be measured as a ratio of SDP to ensure that debt plus likely devolvement on guarantees during its life is sustainable and to ensure that guarantees are also captured in such measures. To refine such measures the sustainability can be worked out in terms of net present values and then measured as ratio of SDP. h. It was also felt that apart from assessing the fiscal risk and making provisions, the State Government should also take administrative measures to discipline the state level undertakings whose borrowings are guaranteed and set up an arrangement whereby they make provisions to meet possible shortfalls in project earnings. The Group recommends one of the following two methods to be used at the discretion of the state governments.

It was felt that while any one of these contingency measures is very essential, the actual choice of which alternative to adopt and the mechanics of such an arrangement are best left to the individual state governments. Working Group on Information on State Government Guaranteed Advances and Bonds (2003) Getting Information in Respect of Entities Not Regulated by RBI In order to get information from the entities that are not regulated by the RBI, the RBI would need to make formal requests to the various regulators such as, the IRDA, NABARD, NHB and the regulator for PFs for compilation and onward transmission of the data to the RBI. Reporting Format and Periodicity The Group decided to keep the reporting format simple for the ease of reporting by the financial market participants and yet comprehensive. The reporting format designed by the Group is divided into three parts. The first and the second parts cover State Government guaranteed loans and advances, and investments, respectively, while the third part provides inter-temporal movements in defaults. While these formats would provide an improved way of presentation of existing data, the various regulators ought to improve upon their data gathering process in order to provide for a comprehensive database as per the format prepared. The periodicity of the return would be half-yearly with a lag of one month (e.g., the data for end-March would be furnished by end-April). During the interregnum (i.e., between the reporting date and the date of furnishing the return), if it is seen that some borrowers have repaid their dues, the same could be indicated in a footnote. Modalities for Collection of Data The present practice on the collection of data should continue. Hence, DBS, FID, DNBS and UBD would be collecting data from commercial banks, select AIFIs, NBFCs and UCBs, respectively. To begin with, UBD would compile data in respect of the scheduled UCBs (56 at present). Over time, UBD could devise a mechanism to obtain timely data from the non-scheduled UCBs as well. As regards the categories of investors not supervised by the RBI, the Group felt that IRDA would collect and forward data to the RBI for insurance companies, NHB in respect of HFCs and HUDCO, NABARD in respect of rural co-operative banks, RRBs, NCDC, etc. Besides, the Central Government (Ministry of Labour) would collect and forward data to the RBI in respect of Provident Fund Trusts and the Ministry of Power in respect of PFC, REC, etc. There should be a central point or ‘data warehouse’ on all State government guaranteed loans and bonds in order to get an aggregate view. A small Core Group may be set up consisting of IT personnel and functional officials from within and outside the RBI that would assess the size of the database, complexity in collection, Management Information System (MIS) expected from the database, issues relating to sharing of data among different departments within RBI and outside RBI, etc. The Core Group may also recommend the suitable IT platform. In this regard, the Core Group could examine whether the Bank’s Central Database Management System (CDBMS), which has the state of the art IT platform and constant online support, has the capacity to handle this kind of data consolidation and maintenance on an ongoing basis. Transparency in Information Disclosure The Working Group examined the desirability of disseminating the information related to defaults. While this could be a welcome course from the investor protection angle, legal complexities may come in the way of disseminating the entire spectrum of information on defaults available with the regulators to the public. Since the group did not have the mandate to decide on the legal aspects and decided to leave it to each of the regulators involved to seek legal opinion on the issue. Instead of publication of data at the issuer level, which in any case is being addressed by the GASAB, the Working Group viewed that (i) individual lender/investor-wise data (broken up into sectors) and (ii) State-wise data on guaranteed advances and investments (including defaults) could be disseminated through the RBI publications (Report on State Finances and Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India) as at the end of September and the Annual Report as at the end of March). The data on defaults could also be disseminated through the RBI web-site. The implications of this dissemination would be that there would be greater awareness about the likely fiscal risk of providing guarantees and the risk posed by State Government guarantees for financial stability. It would be impracticable to capture data on investments by individuals and non-financial corporates (i.e., other than financial institutional investors and lenders), partly because they are too numerous and partly because they have a limited exposure in terms of subscription to guaranteed investments. Working Group on Compilation of State Government Liabilities (2005)

Survey of Disclosure of Contingent Liabilities in State Budget Documents

1 General Financial Rules 2017, Department of Expenditure, Ministry of Finance, Government of India. 2 Following officials also attended the physical/virtual meeting representing their State/Department/Organisation

3 Shri Arun Kumar Mehta was initially inducted into the Working Group. Shri Santosh D. Vaidya took over from Shri Arun Kumar Mehta as Principal Secretary (Finance Department), Jammu and Kashmir and participated in the Group deliberations. 4 A letter of comfort is essentially an instrument that is used to facilitate an action or transaction but is constructed with the intention of not giving rise to a legal obligation. Other similar instruments include Letter of Assurance/Letter of Undertaking. / Letter of Awareness/ Letters of Intent/ Letters of Responsibility. Irrespective of the terminology employed in describing it, the legal liability will depend on the terms and conditions incorporated in the document. 5 Government of Andhra Pradesh suggested that lenders may add the risk premium to the interest rate charged on the loan amount not covered by Government Guarantee, which would increase the cost of borrowing. Therefore, government guarantee may be restricted to 80 per cent of project cost instead of project loan. 6 General Financial Rules 2017, Department of Expenditure, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, 2023 7 Department of Expenditure, MoF, GoI suggested that financial support by way of loan extended by the State Government to the SPEs for repayment of principal and/or interest should be separately disclosed in the state budget. 8 (i) Government of Odisha suggested that prescribing a uniform ceiling may not fulfil the requirement of all the states as they are at different stages of development. Instead, States may be allowed to frame their own ceiling. (ii) Government of Karnataka suggested that most of the state guarantees are concentrated in the Power Sector where there is high probability of default/ invocation of guarantee. The ceiling for incremental guarantees, therefore, should be reduced. Also, sector-wise limits on the guarantees may be considered to mitigate the non-diversification risks.(iii) CAG suggested that ceiling may be incorporated in the respective State FRBM Act / Rules too. 9 Government of Odisha suggested that assigning risk weight to the State guarantees and its disclosure in public document may discourage lending institutions from extending loan or may result in charging of risk premium due to high-risk weights. Further, the lowest slab of risk weight cannot be at 100 per cent as assigning of risk weight is linked to the invocation of guarantees. 10 Government of Odisha observed that the purpose of Government Guarantee was to avail cheaper/ competitive loans. Levying of risk premium may make the loans dearer to State Institutions/ Organisation which could defeat the purpose of Government Guarantee. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

પેજની છેલ્લી અપડેટની તારીખ: