IST,

IST,

Danger Posed by Shadow Banking Systems to the Global Financial System - The Indian Case

Shri R. Gandhi, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India

delivered-on ઑગસ્ટ 22, 2014

What is Shadow Banking? Shadow banking is a universal phenomenon, although it takes on different forms. In advanced economies where the financial system is more matured, the form of shadow banking is more of risk transformation through securitization; while in the economically backward economies where financial market is still in a developing stage, the activities are more of supplementary to banking activities. However, in both the structures, shadow banking operates outside the regular banking system and financial intermediation activities are undertaken with less transparency and regulation than the conventional banking. In a sense, shadow banks are like icebergs - more deeply spread than what they seem to be. 2. In the context of developing economies, shadow banks play a gainful role in credit delivery and financial inclusion as they can facilitate credit availability to certain sectors that might otherwise have difficulty in access to credit. They play both a substitute and complementary role for commercial banks as they are able to map the financing needs of the borrowers with the financing provision where the formal banking systems are confronted with regulatory constraints and/or where the formal banking system's requirements are onerous for the clients to comply with. 3. The term ‘shadow bank’ was coined by Paul McCulley in 2007, by and large, in the context of US non-bank financial institutions engaging in maturity transformations (use of short-term deposits to finance long-term loans). However, a formal touch to the institutions of shadow banking was given by the Financial Stability Board1, which defined ‘shadow banking’ as the “credit intermediation involving entities and activities (fully or partially) outside the regular banking system”. Shadow banking activities, thus, include credit intermediation (any kind of lending activity where the saver does not lend directly to the borrower, and at least one intermediary is involved), and liquidity transformation (investing in illiquid assets while acquiring funding through more liquid liabilities) & maturity transformation (use of short-term liabilities to fund investment in long-term assets) that take place outside the regulated banking system. Focusing on the pre-requisites for sustenance of shadow banking, Claessens and Ratnovski (2014) have described shadow banking as all financial activities, barring traditional banking, which require a private or public backstop (in the form of franchise value of a bank or insurance company, or in the form of a Government guarantee) to operate. 4. In the last two to three decades, growing innovations in the financial sector, changes in regulatory framework and growing competition with non-bank entities caused banks to shift a part of their activities outside the regulatory framework. This contributed to the growth of shadow banks. As a result, shadow banking activities have evolved over time in response to newer set of regulation and supervisory guidelines and spread in the domains where the scope for regulatory arbitrage was higher. It emerged not only as an avenue for exploiting regulatory arbitrage but also in response to market demand for innovative financial instruments that could mitigate risks and yield higher returns. 5. The recent global financial crisis brought to fore the need for monitoring and regulating the activities of shadow banking. There is, nevertheless, a concern that the forthcoming implementation of Basel III, which has more stringent capital and liquidity requirements for the banks, might further push the banks to shift part of their activities outside of the regulated environment and therefore increase shadow banking activities. Size of Shadow Banks 6. One cannot precisely gauge the size of shadow banking as the activities lack transparency. According to the FSB report (2013), size of global shadow system expanded to US$ 71 trillion2 in 2012. In 2012, the assets of other financial intermediaries, which undertake non-bank financial intermediation, accounted for about 24 per cent of total financial assets, about half of banking system assets and 117 per cent of GDP of the above-said 25 jurisdictions. The largest system of non-bank financial intermediation in 2012 was found in the USA, which had assets size of US$ 26 trillion, followed by the euro area (US$ 22 trillion), the UK (US$ 9 trillion) and Japan (US$ 4 trillion). The size of shadow banking in a large number of emerging market economies (EMEs) was found to have increased in 2012, nevertheless, the share of non-bank financial intermediation remained relatively smaller at less than 20 per cent of GDP. As per the report, for a number of EMEs, non-bank financial intermediation remains relatively small as compared to the level of GDP. In India, Russia, Argentina, Turkey, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia the amount of non-bank financial activity remained below 20 per cent of GDP at the end of 2012. However, the sector was growing rapidly in some of these jurisdictions. How are Shadow Banks Dissimilar to Banks? 7. Shadow banks, like conventional banks undertake various intermediation activities akin to banks, but they are fundamentally distinct from commercial banks in various respects. First, unlike commercial banks, which by dint of being depository institutions can create money, shadow banks cannot create money. Second, unlike the banks, which are comprehensively and tightly regulated, the regulation of shadow banks is not that extensive and their business operations lack transparency. Third, while commercial banks, by and large, derive funds through mobilization of public deposits, shadow banks raise funds, by and large, through market-based instruments such as commercial paper, debentures, or other structured credit instruments. Fourth, the liabilities of the shadow banks are not insured, while commercial banks’ deposits, in general, enjoy Government guarantee to a limited extent. Fifth, in the times of distress, unlike banks, which have direct access to central bank liquidity, shadow banks do not have such recourse. 8. While there may be stark differences in the way the shadow banks operate as compared to banks, sometimes there is only a thin line separating the two. For instance a regulated bank may float a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to hold some specific assets, with a view at removing them from its balance sheet. Regulation of Shadow Bank Activities 9. While the role of the shadow banking generated apparent economic efficiencies through financial innovations, the crisis demonstrated that shadow banking created new channels of contagion and systemic risk transmission between traditional banks and the capital markets. Therefore, globally a need was felt to bring such unregulated entities under the regulatory architecture. United States of America passed the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010 that strengthened the arms of Federal Reserve to regulate all institutions of systemic importance. In order to put a control on the burgeoning shadow banking activities, the European Union has also put in place some measures, which inter alia include prudential rules concerning securitisation, regulation of credit rating agencies, etc. Further, at the request of G-20 countries, at international level, FSB has been working towards strengthening the oversight and regulation of the shadow banking system so that the risks emanating from them may be mitigated. Various other countries, including India are working towards improving the regulatory framework so as to curb the shadow banking activities, which pose a risk to financial stability. Challenges Posed By Shadow Banks 10. Though the focus of regulation on shadow banking activities emerged in the wake of their alleged role in the recent global crisis, shadow banking system is not a new development. Even in the late 1950s and early 1960s, concerns emanating from the growth of non-bank financial intermediaries had been highlighted [Thorn (1957); Hogan (1960)]. Thorn (1957) had advocated same degree of control over credit expansion by the NBFIs as that of the banks. Hogan (1960) found that from late 1930s to 1950s, while the role of banking system in Australia was declining, that of the financial intermediaries was rising and he called for controlling the liquidity of the non-banking sector. 11. The biggest challenge for the regulators is to gauge the magnitude of shadow banking as this landscape is continually evolving by arbitraging the gaps in the regulatory framework that otherwise seek to control them. Furthermore, unlike the banking sector, which have a very good statistical coverage, consistent database on shadow banking is not available given the heterogeneous nature of shadow banking entities, instruments and activities. 12. Some of the challenges posed by the shadow banks to the global economy and economies, in general, are as follows: a. Financial Stability and Systemic Risk Concerns 13. Across various economies, regulatory arbitrage was used to create shadow banking entities. In many instances, banks themselves composed part of the shadow banking chain by floating a specialized subsidiary to carry out shadow banking activities. Banks also invested in financial products issued by other shadow banking entities. Since shadow bank entities have no access to central bank funding or safety nets like deposit insurance, they remain vulnerable to shocks. Given the huge size of shadow bank activities and their inter-linkages with other entities of the financial sector, any shock in the shadow banking segment can get amplified, giving rise to systemic risk concern. The capacity of shadow banks to precipitate systemic crisis was manifested in the recent global financial crisis. b. Regulatory arbitrage spread across geographical jurisdictions 14. Different legal and regulatory frameworks across geographical jurisdictions also pose a significant handicap in curbing the shadow banking activities, which are spread across borders. For instance, high taxation in some jurisdictions sometimes generates tax avoidance strategies by financial firms. Tax haven countries with their eye on attracting foreign capital and creation of jobs in their economies keep their tax rates low. Firms in high taxation countries restructure their financial activity by shifting some high tax activities to low tax countries. This, at times, generates large and significant hot money flows, which itself, is a source of instability for both set of countries from where it outflows to where it flows in. This, at times, has an adverse effect on financial stability, especially at a time when the whole global economy is far more integrated than ever. c. Challenges in the conduct of Monetary Policy 15. Opaqueness of its structure, size, operations and inter-linkages of shadow banks with commercial banks and other arms of the financial sector might distort the information content of monetary policy indicators and thereby undermine the conduct of monetary policy. For instance, a Central Bank might lose control over the credit aggregate (as these entities broadly remain outside the regulatory purview), which might weaken the monetary policy transmission through credit channel. This concern was highlighted even in the 1950s. Thorn (1957) advocated some form of control over credit abilities of the non-bank financial intermediaries for the successful implementation of monetary policy as these entities remain immune to direct central bank control. Hogan (1960) had also advocated controlling the liquidity of the non-banking sector through a flexible interest rate policy that could influence the behavior of the NBFIs in Australia. 16. Shrestha (2007) found that growing level of intermediation activities of the non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) causes a shift in deposits from banks to non-banks in South-East Asian Countries. He observed that since the deposits of the NBFIs are not included in the monetary aggregates, the conduct of monetary policy gets undermined for regimes, which follow monetary targeting framework. 17. A Deutsche Bundesbank study (2014) contended that the growing activities of shadow banks might weaken the transmission of monetary policy measures via commercial banks (through interest rate and bank credit channel), but, on the contrary, the asset prices channel may become effective in the monetary policy transmission process. An expansionary monetary policy might fuel asset prices, which, in turn, might increase the leverage of the shadow banks, expand their balance sheets, reduce their risk premium and thereby increase lending to non-financial sector and finally the level of real activity3. d. Procyclicity and amplification of business cycles 18. Shadow banking activities, which broadly remain less regulated, have been reported to act pro-cyclically, which might amplify financial and economic cycles. Their leverage would rise during booms (as they face little problem in arranging funds) as assets price rise and margin/ haircuts on secured lending remain low. On the contrary, during the downturn phase (as the funding becomes difficult) as asset prices fall and margins/ haircuts on secured loan become tighter, shadow bank get compelled to undertake deleveraging. 19. Pro-cyclicality of shadow banks may also get exacerbated owing to their inter-connectedness with the banks. FSB (2012) observed that inter-connectedness of the shadow banks with the banks might aggravate the pro-cyclical build-up of leverage and thereby heighten the risks of asset price bubbles, especially when the investment assets of the two systems are correlated. This pro-cyclicality in the financial system might amplify financial and business cycles. High pro-cyclicality of the shadow banking sector has implications for the real sector, which might also get affected adversely as funding by the shadow banks to the real economy during the economic downturn might take a hit. Shadow Banking and Indian Economy 20. The type of entities which are called shadow banks elsewhere are known in India as the Non-Banking Finance Companies (NBFCs). Are they in fact shadow banks? No, because these institutions have been under the regulatory structure of the Reserve Bank of India, right from 1963 i.e. 50 full years before many in the world are thinking of doing so! Evolution of Regulation of NBFCs in India 21. In the wake of failure of several banks in the late 1950s and early 1960s in India, large number of ordinary depositors lost their money. This led to the formation of the Deposit Insurance Corporation by the Reserve Bank, to provide the necessary safety net for the bank depositors. The Reserve Bank did then note that the deposit taking activities were undertaken by non-banking companies also. Though they were not systemically as important as the banks, the Reserve Bank initiated regulating them, as they had the potential to cause pain to their depositors. 22. Later in 1996, in the wake of the failure of a big NBFC, the Reserve Bank tightened the regulatory structure over the NBFCs, with rigorous registration requirements, enhanced reporting and supervision. Reserve Bank also decided that no more NBFC will be permitted to raise deposits from the public. Later when the NBFCs sourced their funding heavily from the banking system, thereby raising systemic risk issues, sensing that it can cause financial instability, the Reserve Bank brought asset side prudential regulations onto the NBFCs.NBFCs of India 23. The ‘NBFCs’ of India include not just the finance companies, but also a wider group of companies that are engaged in investment, insurance, chit fund, nidhi, merchant banking, stock broking, alternative investments etc. as their principal business. NBFCs being financial intermediaries are playing a supplementary role to banks. NBFCs especially those catering to the urban and rural poor, namely NBFC-MFIs and Asset Finance Companies have a complimentary role in the financial inclusion agenda of the country. Further, some of the big NBFCs viz; infrastructure finance companies are engaged in lending exclusively to the infrastructure sector, and some are into factoring business, thereby giving fillip to the growth and development of the respective sector of their operations. In short, NBFCs bring the much needed diversity to the financial sector. Profile of NBFCs 24. The total number of NBFCs as on March 31, 2014 are 12,029 of which deposit taking NBFCs are 241 and non-deposit taking NBFCs with asset size of ` 100 crore and above are 465, non-deposit taking NBFCs with asset size between ` 50 crore and ` 100 crore are 314 and those with asset size less than ` 50 crore are 11009. As on March 31, 2014, the average leverage ratio (outside liabilities to owned fund) of the NBFCs-ND-SI stood at 2.94, return on assets (net profit as a percentage of total assets) stood at 2.3%, Return on equity (net profit as a percentage of equity) stood at 9.22% and the gross NPA as a percentage of total credit exposure (aggregate level) stood at 2.8%. Asset Liability composition: 25. Liabilities* of the NBFC sector: Owned funds (23% of total liabilities), debentures (32%), bank borrowings (21%), deposit (1%), borrowings from Financial Institutions (1%), Inter-corporate borrowings (2%), Commercial Paper (3%), other borrowings (12%), and current liabilities & provisions (5%). 26. Assets*: Loans & advances (73% of total assets), investments (16%), cash and bank balances (3%), other current assets (7%) and other assets (1%).  *The data pertains to only reported deposit taking NBFCs and those non-deposit taking NBFCs with asset size of ` 100 crore and above. All figures are as on end March, 2014. The Dangers and the Regulatory Challenges 27. The growing size and interconnectedness of the NBFCs in India also raise concerns on financial stability. Reserve Bank’s endeavour in this context has been to streamline NBFC regulation, address the risks posed by them to financial stability, address depositors’ and customers’ interests, address regulatory arbitrage and help the sector grow in a healthy and efficient manner. Some of the regulatory measures include identifying systemically important non-deposit taking NBFCs as those with asset size of ` 100 crore and above and bringing them under stricter prudential norms (CRAR and exposure norms), issuing guidelines on Fair Practices Code, aligning the guidelines on restructuring and securitization with that of banks, permitting NBFCs-ND-SI to issue perpetual debt instruments, etc. 28. Just as the shadow banks (i.e. the NBFCs) in India are of a different genre, the dangers posed by them are also of different genre. Consequently, the regulatory challenges that we face today are different which are as follows: 29. First, there are law related challenges viz. i. there are a number of companies that are registered as finance companies, but are not regulated by the Reserve Bank, ii. there are unincorporated bodies who undertake financial activities and remain unregulated, iii. there are incorporated companies and unincorporated entities illegally accepting deposits, iv. there are entities who camouflage deposits in some other names and thus illegally accepting deposits. The law as it stands today is inadequate to deal with these issues. In order to correct these and initiate action against violations, we need to bring in suitable amendments to the statutory provisions. Reserve Bank is working with the government for such improvements in the law. 30. Secondly, as the entities, especially the unincorporated ones, can sprung in any nook and corner of the country and can operate with impunity unnoticed, but endangering their customers interest, we need arrangements and structured for effective market intelligence gathering. The Reserve Bank is restructuring its organisational setup, especially in its regional offices, for gathering market intelligence. 31. Thirdly, empowering law and gathering intelligence by themselves are not sufficient. Enforcement of the law is a challenge. This is primarily because of the various agencies involved in regulating the non-banking financial activities of entities. Right from the central government ministries like finance and corporate affairs, agencies like CBI and FIU-IND, regulatory agencies like the Reserve Bank, SEBI, the Registrar of Companies, the state government agencies like the police and others, all have to share information and coordinate and cooperate to bring in an effective, timely and unified enforcement of the law. The Reserve Bank's State Level Coordination Committees (SLCC) are being strengthened and a National level Coordination Committee is also being considered. 32. Fourthly, the international requirement is that the shadow banks be brought under tighter regulations. G-20 has already expressed it as a mission to be achieved by 2015. In our case, bringing them under regulation is not the issue, as they already are. The challenge for us is how differentially or how closely we should regulate the NBFCs? Conclusion 33. To summarise, the shadow banks in India (i.e. the NBFCs) are of a different type; they have been under regulation for more than 50 years; they subserve the economy by playing a complimentary and supplementary role to mainstream banks and also in furthering financial inclusion. Yet, they do pose dangers, but of different variety; it primarily relates to consumer protection. It is the constant endeavour of Reserve Bank to enable prudential growth of the sector, keeping in view the multiple objectives of financial stability, consumer and depositor protection, and need for more players in the financial market, addressing regulatory arbitrage concerns while not forgetting the uniqueness of NBFC sector. 34. Thank you very much for your patient attention. References: Tobias Adrian, Emanuel Moench, and Hyun Song Shin (2010), ‘Macro-risk Premium and Intermediary Balance Sheet Quantities, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 428, January. Bakk-Simon, Klára; Borgioli, Stefano; Girón, Celestino; Hempell, Hannah; Maddaloni, Angela; Recine, Fabio and Simonetta Rosati (2012), ‘Shadow Banking in the Euro Area: An Overview’, ECB Occasional Paper Series, No. 133, April. Birnbaum, Eugene A. (1958), ‘The Growth of Financial Intermediaries as a Factor in the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy’, International Monetary Fund Staff Papers, Vol. 6, No. 3, November, pp. 384-426. Claessens, Stijn and Lev Ratnovski (2014), ‘What Is Shadow Banking?’, IMF Working Paper, WP/14/25, February. Deutsche Bundesbank (2014), ‘The shadow banking system in the euro area: overview and monetary policy implications’, Monthly Report, March Financial Stability Board (2012). Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2012. Financial Stability Board (2013). Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2013. Ghosh, Swati; Mazo, Ines Gonzalez del; and İnci Ötker-Robe (2012), ‘Chasing the Shadows: How Significant Is Shadow Banking in Emerging Markets?’, Economic Premise, World Bank, Number 88, September. Gorton, Gary and Andrew Metrick (2010), ‘Regulating the Shadow Banking System’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall. Hogan, Warren P. (1960), ‘Monetary Policy and Financial Intermediaries’, The Economic Record, December, pp. 517-529. Reserve Bank of India (2013), ‘Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India – 2012-13’. Shrestha, Min B. (2007), ‘Role of Non-Bank Financial Intermediation: Challenges for Central Banks in the SEACEN Countries’, SEACEN Centre, Malaysia. Thorn Richard S. (1957), ‘Nonbank Financial Intermediaries, Credit Expansion, and Monetary Policy’, International Monetary Fund Staff Paper. Address by Shri R. Gandhi, Deputy Governor on August 21, 2014 at ICRIER’s International Conference - Governance & Development: Views from G20 Countries. Assistance provided by Shri SM Pillai and Shri Raj Rajesh is gratefully acknowledged. 1 See Financial Stability Board (2012). 2 This is the magnitude of non-bank financial intermediation, which is a conservative proxy of the global shadow banking system based on data from 25 countries - 5 euro area economies and 20 non euro area jurisdictions. For 2011, FSB had reported the size of shadow banking to be around US$ 66 trillion. |

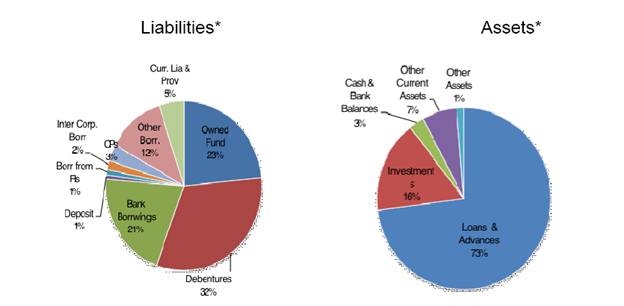

પેજની છેલ્લી અપડેટની તારીખ: