IST,

IST,

Challenges to Monetary Policy in A Global Context

Dr. Rakesh Mohan, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India

उद्बोधन दिया नवंबर 21, 2003

Rakesh Mohan*

I. Introduction

Recent global developments have transformed the environment in which monetary policy operates, throwing up opportunities as well as challenges. Globalisation has expanded economic interdependence and interaction of countries greatly. This has created the need for greater coordination in terms of the design of appropriate institutional architecture as well as standardisation reflected in the adoption of similar monetary policy approaches. It has also been associated with a dramatic lowering of inflation worldwide. Central banks have seized these opportunities to bring about institutional reforms to enhance their own accountability and credibility of monetary policy making. Moreover, they have had to hone their technical and specialist management skills to acquire adequate competence to deal with the emerging complexities of financial markets.

The more recent evolution of the global economy has accentuated the challenges that face monetary authorities. Increasingly, monetary policy decisions have to be made in an environment of heightened uncertainty. Structural changes associated with globalisation have increased the uncertainty in interpreting macroeconomic indicators regarding the state of the economy. Another form of uncertainty stems from the strategic interaction between private agents and monetary policy authorities and, in particular, the role of expectations in the monetary transmission mechanism. Financial markets, driven by massive cross-border capital flows and the information technology revolution, immediately transfer the valuation of risks associated with uncertainty across the globe and this can lead to contagion. Indeed, global interdependence is marked by common shocks and a "confidence channel" rapidly transmits these shocks to various parts of the world.

All this has rendered the conduct of monetary policy extremely complex in such an environment of interdependent risks. Therefore, even though monetary policy is conducted towards achieving domestic objectives, central banks have to follow developments across the world carefully. More than ever before, the choice of monetary arrangements depends on the choices that other countries make (Meltzer, 1997).

In my lecture today, I propose to dwell upon the uncertainties that characterise the monetary policy environment, the underlying macroeconomic conditions in which monetary policy has to be set, the process of inflation and the changing institutional response to the commitment to price stability, the role of capital flows and what the future holds in store. Against this backdrop, I hope to shed some light on the emerging discussion among central bankers about the course of monetary policy that is of greater relevance to developing countries such as ours.

II. The Current Global Economic Scenario

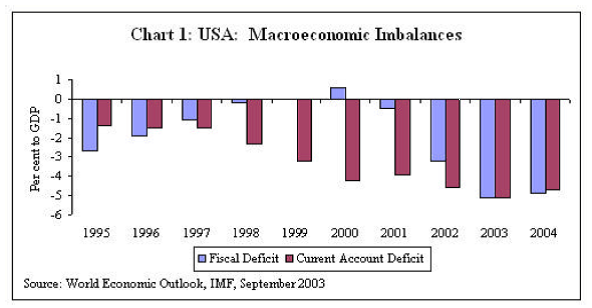

The growing internationalisation of monetary policy has been brought into sharp focus by the synchronised global downturn since the late 1990s. In response, monetary authorities all over the world have made concerted efforts to ease their policy stance significantly. The US has powered the world economy during the last 7-8 years and has been responsible for about 60 per cent of world growth. Despite bursting of the stock market bubble, a rash of corporate governance problems and the IT bubble, US has been the main engine of world growth in recent years and has been partly responsible for the recovery of Asian countries after the 1997 crisis. In the bargain, the US has accumulated twin deficits – current account deficit (CAD) of five per cent, and fiscal deficit of six per cent (a sharp turnaround from a surplus of 1.2 per cent in 2000) (Chart 1). With the emergence of such an imbalance in the US, other regions in the world have to exhibit an equal and opposite imbalance of their own. Ironically, it is the developing countries of Asia who are funding the CAD of the US and exhibiting surplus. The central banks of Asia are financing roughly 3-3.5 per cent of the CAD of US and most of its fiscal deficit, as compared to the earlier situation where it was private sector flows that were funding these deficits. In view of the difficulties in monetary management that the situation entails, this situation is clearly not sustainable indefinitely. There are no short-cut solutions since the problems are deep, structural and inter-dependent: hence these cannot be solved through independent or unilateral action. For example, difficult structural reforms are necessary in the Euro area; more structural reforms are needed in Japan, particularly in the financial sector; India has a large fiscal deficit problem, and China cannot afford a major appreciation. Hence, relatively coordinated medium term action is called for among the major economies of the world. Unilateral action by any country is unlikely to solve its own problems.

Recent months have seen the emerging signs of a recovery in economic activity, particularly in the US, Japan and emerging Asia. In the US, the pace of growth has picked up, assisted by expansionary macroeconomic policies and supportive financial conditions. Equity and bond markets have responded with optimism to prospects of recovery with investor interest returning to technology stocks more rapidly than to other sectors. In Japan, there are stronger signs in the third quarter that a cyclical upswing is underway, led by industrial activity and exports. In the UK and Australia, signs of recovery are clearly evident with rising household spending reflected in retail price inflation, prompting monetary authorities in these two countries to raise key policy interest rates against inflation surprises. China continues to grow at a remarkably strong pace while activity in other parts of Asia is bouncing back from the effects of SARS. There is nevertheless considerable uncertainty regarding the durability of the pick-up. In the US, labour markets remain sluggish and significant excess capacity persists. Moreover, the substantial support provided to consumption by tax cuts is unlikely to be sustained. Despite the prospects of stronger growth, Japan continues to experience deflation. The ongoing concerns relating to structural weaknesses in the financial system remain. In contrast to the rest of the world, the euro area remains conspicuously weak although there are tentative signs of a modest recovery in recent months. Household demand remains sluggish and the unemployment rate for the area as a whole has risen.

The burden of adjustment to the global slowdown has been highly asymmetric and this raises the risks associated with sustaining the recovery. The US has been virtually alone among the OECD countries in pursuing an aggressive and flexible countercyclical monetary and fiscal policy – cuts in policy interest rates have been the largest and the swing in structural government balance from a surplus of 0.6 per cent of GDP in 2000 to a deficit of 5.1 per cent in 2003 is the largest in three decades. Global growth will continue to be led by the US, but significant downside risks could emanate from the emergence of the record current account and fiscal deficits of the US. While the depreciation of the US dollar has so far been relatively orderly, further and substantial depreciation remains a danger to global recovery in the shadow of the twin deficits. History suggests that even an orderly adjustment in key exchange rates is likely to be associated with a slowdown in US growth – and, if growth in the rest of the world remains weak, in global growth as well (IMF, 2003). The continuing dependence of the world on the US heightens the risks of disorderly adjustment, particularly if it translates into an off-setting appreciation of the euro. In contrast to the mid-1980s, when the US ran current account deficits of similar order as in 2003, neither Europe nor Japan is in a position today to pick up the slack. Looking ahead, it is unlikely that the US can provide the degree of support to the global economy that it has in the past. In particular, high fiscal deficits would offset the longer-term benefits of tax cuts and rising debt service burdens in the household sector will curb future consumption spending.

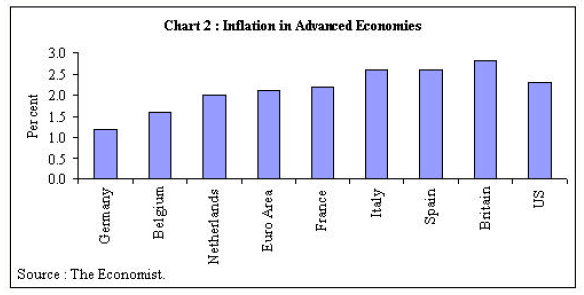

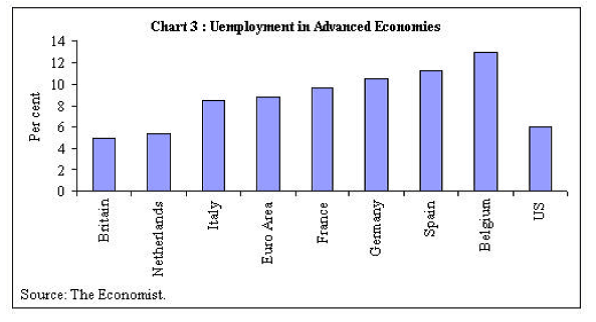

In the euro area, whereas monetary policy can be adjudged to have been successful in an inflation targeting framework (Chart 2), the economic slowdown has been deep and prolonged, with GDP declining in the second quarter of 2003. The largest economies – Germany, France, the Netherlands and Italy – are in recession with high levels of unemployment. The unemployment rate is 8.8 per cent for the euro area as a whole and even higher in some individual countries: 13.2 per cent in Belgium, 9.7 per cent in France, 10.5 per cent in Germany, 8.5 per cent in Italy and 11.4 per cent in Spain (Chart 3). Despite some recent improvement in expectations, household and business confidence remains depressed. The poor performance of Germany, in particular, threatens to hold back the region’s recovery. Corporate balance sheets are still adjusting to the bursting of the asset price bubble of the late 1990s and this is holding down investment spending. Exports have been adversely affected by weak external demand as well as the substantial appreciation of the euro over the past two years. Monetary policy has been accommodative but different inflation and unemployment rates in different countries blur the effectiveness of the common monetary policy. A more activist approach is warranted especially when downside risks to individual countries have potentially area-wide spillovers. Although Germany and France are expected to post fiscal deficits above 4 per cent of GDP in 2003, the scope for countercyclical fiscal policy is limited by the Stability and Growth Pact. Structural reforms hold the key to improving Europe’s economic performance, including further liberalisation of labour and product markets, pension reforms and offsetting measures to deal with the aging of population.

In Japan, macroeconomic performance during 2003 has exceeded expectations alongside an improved external environment and upturn in equity markets. The outlook remains overcast with deflationary pressures and persistent weakness in the financial sector. The possibility of declines in equity or bond prices, a sustained appreciation of the Yen and rising public debt remain dangers to a durable recovery. More rapid and bolder reforms in the financial sector are needed to address the large overhang of non-performing loans and the poor quality of capital in the banking sector. Financial sector measures need to be complemented by corporate restructuring. Quantitative easing of monetary policy has kept short-term interest rates at zero, but has not been aggressive enough to end deflation. The build-up of public debt and pressures from population aging necessitate a medium-term strategy to impart sustainability to fiscal policy.

Overall, global macroeconomic imbalances and the associated misalignment of the G-3 currencies remain the most serious threat to a broad-based and robust recovery. This has implications for the pattern of capital flows. In contrast to preceding years, the US current account deficit has been financed primarily by sale of government and corporate paper rather than equity inflows. The bulk of these investments has been by central banks, particularly those in Asia. This is clearly unsustainable and adjustments will be needed to achieve medium-term stability. An eventual narrowing of the US current account deficit will require emerging economies to share in the adjustment to prevent an undue burden on the euro area. A current issue of concern is the practice of greater flexibility in the exchange rate regimes of these countries, and the resulting efforts on the real economy. Studies have shown that greater volatility in developing countries’ real exchange rates has been associated with greater misalignment in G-3 countries with disruptive effect on both trade and finance channels. This emerges as a major source of uncertainty for the conduct of monetary policy.

The current imbalances in the world where Asian countries are financing Western countries, particularly the US, could have their roots in longer term demographic imbalances. The long-term demographics facing the world, which have an effect on the savings rate are not encouraging. The demographics in Europe, Japan and the US are against high saving rates. The median ages in Japan, Europe and the US are 4l, 40 and 35 years, respectively. Current trends indicate that the median age in Japan will increase to 50 by 2025. The situation in the US may not turn adverse due to their flexible immigration policies. Within Asia, India and China can expect their savings rate to increase further, given that the private savings of these two countries are among the highest in the world, and in view of their favourable demographics over the next 20 years. Countries like India and China, which account for a large proportion of world population, also have low urbanisation levels of 30 to 35 per cent and will be moving to 50 to 55 per cent in the next 20 to 30 years. This would necessitate higher infrastructure investment requiring higher capital inflows and a higher current account deficit. Thus, if the Asian countries are to run large capital account surpluses and current account deficits, the situation in the US and Europe would meet reversal. The issue is to try to comprehend what would be required for this macro reversal to occur. The current demographic trends in Europe and Japan are not sustainable. In the future, they may not be able to afford the pension system and social security as they exist now. The only solution in Europe seems to be US type of immigration policies towards labour market reforms. Currently, this is not possible because of high unemployment.

III. Inflation: What is Going on

In this brief overview of the global economic situation today, I have tried to indicate that global imbalances are inter-related and how monetary policy making in countries like ours has become that much more difficult on a day-to-day basis. The most notable achievement in recent years has been the substantial success in almost all countries in reducing inflation to the lowest level in several decades. Sustained inflation is a relatively modern phenomenon. Until World War I, the international experience was one of long-run price stability. Following the turbulence of the inter-war period, the Second World War and the Korean War of the early 1950s, the Vietnam war of the 1960s and early 1970s, inflation gradually increased from the late 1960s, partly as a result of expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. The massive oil price hike of 1973 stepped up global inflation to double-digits in the US and Western Europe. There was a huge transfer of resources to the Middle East from the rest of the world including Asia. The lasting consequence of this development of the 1970s has been the migration of workers from countries like ours who are now remitting back large sums of money on a sustained basis. Although inflation abated in 1978, it rose to double-digit levels again by the end of 1979 following the second oil shock. Inflation finally broke in 1982, under the impact of aggressive disinflationary policies.

The 1980s were marked by strong and widespread efforts to restore reasonable price stability through a combination of tight monetary policy, fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. The reduction in inflation, facilitated by a significant decline in oil prices, set the stage for a robust economic recovery that continued till the end of the 1980s. Another inflation episode in 1989-90 due to the hardening of oil prices was met with aggressive monetary policy action which enabled a cooling-off by 1991 at the cost of a much shallower recession than the early 1980s.

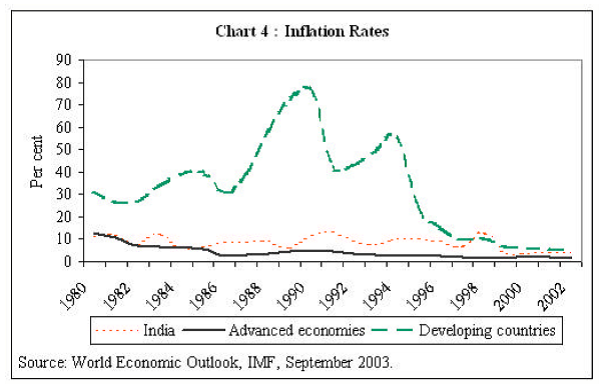

Since then, the world has been going through one of the longest phases of low inflation in post-World War II history. The decline in inflation is evident across countries at different stages of development (Chart 4). It has been most spectacular in developing countries where inflation fell from 31 per cent in early 1980s to under 6 per cent in 2000-03. In Latin America and the countries in transition where inflation averaged 230 per cent and 360 per cent, respectively, during 1990-94, it is projected at around 10 per cent in 2003. Out of 184 members of the IMF, 44 countries had inflation greater than 40 per cent in 1992. In 2003, this number has fallen to 3. For industrial countries, inflation, currently at around 2 per cent, has fallen below the lows of the 1950s. Arguably, deflation threatens more countries today than does high inflation.

What has brought about this significant decline in inflation globally? A significant strand in the literature points to institutional changes in the conduct of monetary policy - independent central banks, increased transparency, greater accountability through contractual frameworks, and greater coordination between monetary and fiscal authorities – which has enhanced the reputation of monetary authorities and increased public credibility in their ability to deliver low inflation. An equally influential body of work, however, suggests that monetary authorities have just been lucky and that there are other factors at work such as increased level of competition due to the forces of globalisation, successful fiscal consolidation in developed countries, particularly in the context of the Maastricht Treaty, and structural changes in the global economy in which productivity has a major role to play and the rising prominence of the new economy. Have central banks been lucky or good? Perhaps a bit of both (Rogoff, 2003). While the evidence on either side is still evolving, the current assessment is that it is unlikely that there will be a reversal of the current trend in inflation. It is important, however, to introspect a little further in order to understand the dynamics of low inflation and its future compatibility with monetary policy in an international setting.

An important factor that might have contributed to the lowering of inflation is productivity growth. Although productivity growth in Europe may not have been as high as it has been in the United States, the disinflationary effects of such productivity growth in one region get transmitted across borders through increased competition in a globalised world, operating through lowering of price mark-ups and erosion of monopoly pricing power through the expansion of cross border trade. Increased competition has made prices more flexible in their response to real activity, thereby reducing the incentive for monetary policy to be expansionary. This has reinforced credibility in the commitment of monetary policy to containing inflation (Rogoff, op cit).

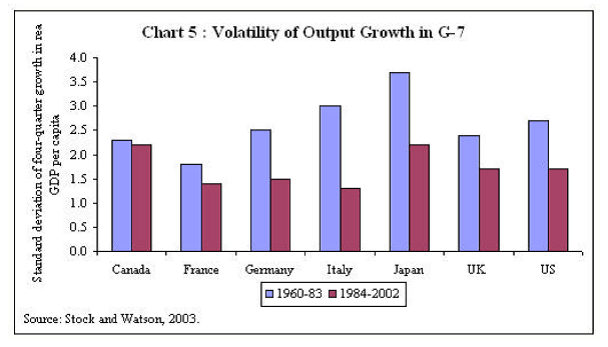

Despite growing globalisation and synchronisation of business cycles, the most striking change over the past three decades has been the moderation of volatility in GDP growth in most G-7 countries and this could also have contributed to reducing inflation (Chart 5) (Stock and Watson, 2003). A number of factors are at work. First, the services sector, which is less susceptible to volatility than manufacturing, has increased its share in output. Second, inventory management has improved. Third, financial markets have provided households with easier access to credit. In the US, the sector that witnessed greatest reduction in volatility is housing. Moreover, there have been fewer oil supply and price disruptions as well as smaller productivity shocks in the 1980s and 1990s than during the 1960s and 1970s. Although only a small part of the moderation in output volatility is attributed to monetary policy, this is hotly debated. For instance, it is widely believed that monetary policy in the US has been successful in implementing anticipatory non-inflationary policies and has focused on sustainable long-term real rates of interest. A significant increase in the flexibility of the US economy to smoothen shocks as a result of deregulation, technology, better inventory management and flexible labour markets has enabled it to absorb shocks. The manner in which a shock is defined is critical. The perception of a smaller shock is really 'net shock' i.e. gross shock minus what has been absorbed. Thus, events like September 11 can be measured only in a net sense. Moreover, in an integrated world, it would be difficult to distinguish between exogenity and endogenity; for instance, an increase in oil prices could very well be treated as endogenous.

Yet another set of forces operating on inflation emanates from technological change. Advances in architecture and engineering as well as development of lighter but stronger materials has resulted in "downsized" output, requiring more technology sophisticated inputs rather than material intensive inputs. This process has accelerated in the recent decades with the advent of the semi-conductor, the micro-processor, the computer and satellite. The impact of technological change is evident in the huge expansion of the money value of output and trade but not in tonnage. As a consequence, material intensity of production has declined reflecting, as Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan (1998) noted, "the substitution, in effect, of ideas for physical matter in the creation of economic value". This has contributed to the secular decline in commodity prices. In fact, a long-run trend decline in commodity prices over the last 140 years shows little evidence of reversal. Concerns over increasing commodity price volatility around this declining trend have, however, increasingly engaged monetary policy attention in the short-run.

A significant strand in the literature credits changes in the institutional and operating framework of monetary policy with the success in achieving low inflation. After the experience of sustained inflation of the 1960s and 1970s, the objective of inflation control became stronger, and the movement of inflation targeting emerged. Massive cross-border capital flows, globalisation of financial markets and the information technology revolution have combined to alter significantly the choice of instruments of monetary policy, operational settings, lag structures and transmission mechanisms. In particular, these forces have led to the progressive erosion of the traditional anchors of monetary policy. In general, there has been a waning of the importance of intermediate targets. Even as monetary authorities deal with this difficult transition, several countries have radically altered the institutional architecture of monetary policy, including increased independence of the monetary authority, clarity of rules and responsibilities and constrained discretion. About 22 countries have adopted policy regimes with inflation as the single target of monetary policy. Indeed, inflation targeting has emerged as the received orthodoxy in the design of monetary policy. The ongoing slowdown in global economic activity and the threat of deflation has, however, weakened its analytical edifice. Although the practice of inflation targeting is associated with a lowering of inflation, the jury is still out on the extent to which inflation targeting policies have actually contributed to the reduction in inflation that has occurred. Moreover, inflation that is too low, which is being observed today, is not just a disincentive for production decisions, it also delays consumer spending at a time when it could have been critical for triggering the upturn. It imparts inflexibility to labour markets, causing unemployment and deepening the slowdown. Signals from financial prices get blurred and this leads to misallocation of resources. In this context, the recent experience with inflation targeting as a framework for monetary policy warrants a close and hard scrutiny.

The fixation with short-run price stability or ‘inflation nutting’, to borrow a term from Mervyn King, Governor, Bank of England can easily lead to neglect of important signs of macroeconomic and financial imbalances. Moreover, there is no available empirical evidence to suggest that inflation targeting improves economic performance. In the euro area, for instance, setting the inflation target at close to 2 per cent is associated with weakening economic activity. This got pronounced in the second quarter of 2003 when real GDP declined, accompanied by large scale unemployment and the threat of deflation in the larger constituents. Furthermore, the relevance of a single inflation target for a large economy, in particular, can be debated. The inflation target for the euro area suffers from the problems of a ‘one size fits all’ monetary policy. Regional disparities warrant different short-run monetary policy approaches to its objectives. A certain amount of target flexibility and balancing of conflicting objectives are unavoidable in the real world, particularly that of emerging market economies (Eichengreen, 2002). Indeed, there is a growing sense that by the time the current phase of the global business cycle has run itself out, inflation targeting may not be seen to have stood the test of time.

High and sustained growth of the economy in conjunction with low inflation is the central concern of monetary policy. The rate of inflation chosen as the policy objective has to be consistent with the desired rate of output and employment growth. An inappropriate choice can lead to losses of macroeconomic welfare. Monetary authorities have to continually contend with the short-run trade-off between growth and inflation. The problem is compounded by the fact that the association between growth and inflation is non-linear. At some low rates, inflation could operate in a manner that assists in bringing back unemployed resources into the economy and be beneficial or, at worst, neutral to growth. At higher levels, inflation is inimical to growth. There are also very low levels of inflation that are associated with no growth or even deflation. At what level should the policy choice of inflation be or what is the threshold rate of inflation, if there is one, which is associated with the absence of harmful effects of growth? There have been various studies that have attempted to estimate threshold inflation rates. They suggest that the threshold inflation rate depends upon a number of factors such as the structure of the economy, past inflation history, the degree of indexation, and inflation expectations. Some studies suggest that the threshold inflation for developed and developing countries fall in the ranges of 1-3 per cent and 7-11 per cent, respectively (Khan and Senhadji, 2000). An abiding problem with cross-country studies, however, is the risk of being influenced by extreme values since samples include countries with inflation as low as one per cent and as high as 200 per cent and even higher. The estimation of such inflation threshold rates, therefore, needs to be done for each country separately (Rangarajan, 1998), in order to understand the behaviour of the economy in relation to inflation.

A major source of uncertainty in conducting monetary policy is the lack of a clear understanding of the inflationary process as it has unfolded in recent years. This has obscured a proper assessment of the nature of shocks impacting on the economy and the resulting risks to price stability. Variations in the timeliness and reliability of inflation indicators, uncertainty surrounding unobservable indicators like potential output and gaps in the intrinsic knowledge of the central banks about the state of the economy complicate the making of monetary policy. In countries like ours, there are other rigidities related to administered prices, wage setting procedures, and weather induced supply shocks that influence prices. Knowledge of the relationship between inflation and its determinants remains limited (ECB, 2001). Even if there were a consensus on a suitable model, considerable uncertainty would remain regarding the strength of the structural relationships within the model. An even more fundamental problem is that parameters may vary over time as a result of structural changes in the economy. This presumably explains why no central bank uses a formal model to derive its actual policies; for the foreseeable future, models will be an aid to judgement rather than a substitute for judgement (Feldstein, 2003). The simple principle of inflation targeting thus is also not so simple and, poses problems for monetary policy making in developing countries.

IV. The Prime Mover: International Capital Flows

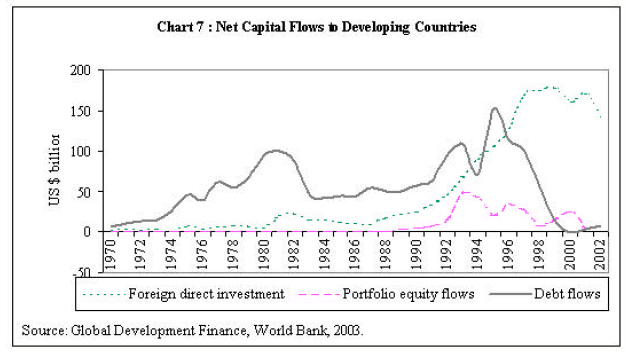

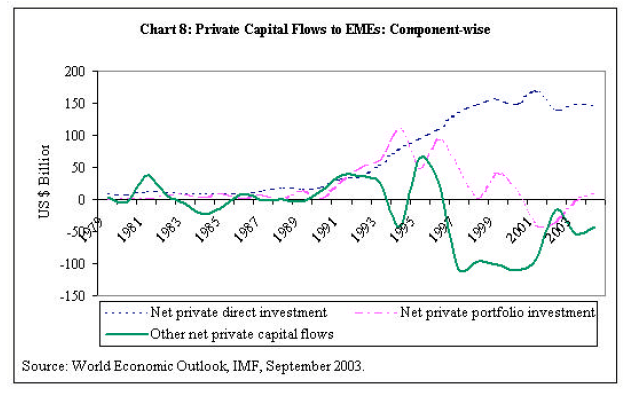

Global capital flows impact the conduct of monetary policy on a daily basis. The problem, however, is that capital flows typically follow a boom-bust pattern. Net capital flows are currently limping back from the severe retrenchment imposed by the Asian financial crisis, which brought to an end the most dramatic surge of capital flows in post-World War II history. It is only in the recent period, particularly in 2003, that conditions for the rejuvenation of capital flows are emerging.

Large swings in capital flows are observed not only in the short term but there have been long term patterns as well. A major surge in capital flows started around the 1870s and continued till the first World War. The flows were mainly between the so-called developed countries – from the core countries of Western Europe to peripheral Europe and overseas European settlements - and in the form of foreign investment, with more than two-thirds comprising portfolio inflows. This era, which coincided with the operation of the classical gold standard, is widely regarded as the high watermark of capital mobility. The boom ended with the first World War. A brief restoration of the gold standard was shattered by the Great Depression and the ensuing period up to the early 1940s was characterised by modest flows to the then emerging market economies for development finance. Capital controls were widespread in the attempt to maintain gold parities and international finance became fragmented by bilateral trade agreements. In the post-World War II period up to the 1970s, controls spread and intensified. International capital flows were primarily among industrial economies. The US removed restrictions on capital outflows in 1974-75 while Germany retained controls over inflows until the late 1970s. The UK maintained controls until 1979 and Japan completed liberalisation of the capital account in 1980. Developing countries persevered with controls with some Latin American countries embarking on flawed liberalisation as part of exchange rate-based stabilisation programmes in the mid-1970s.

In the period since 1973, dramatic changes set in. Private capital flows to developing countries were renewed as commercial banks furiously recycled oil surpluses. Asia and Latin America received the maximum share. Developing country debt exploded, rising at a compound annual rate of 24 per cent (World Bank, 2003) until the debt crisis of 1982 burst the bubble. Capital flows to developing countries slowed down substantially but did not dry up. Between 1983 and 1989, they fell to less than a third of their level in 1977-82. A generalised risk aversion to developing country debt dominated international financial markets and developed countries turned into attractive destinations. By the end of the 1980s, direct investment inflows to developing countries were only one-eighth of flows to developed countries; portfolio flows to developing countries were virtually non-existent. During the 1980s and the 1990s, several developing countries in Asia undertook capital account liberalisation as part of unilateral financial deregulation, often in the face of large external surpluses. In general, the period from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s was characterised by removal of official restrictions on financial markets and wider market-oriented reforms in both mature and emerging market economies. The most dramatic move towards capital account liberalisation occurred among the continental members of the European Union.

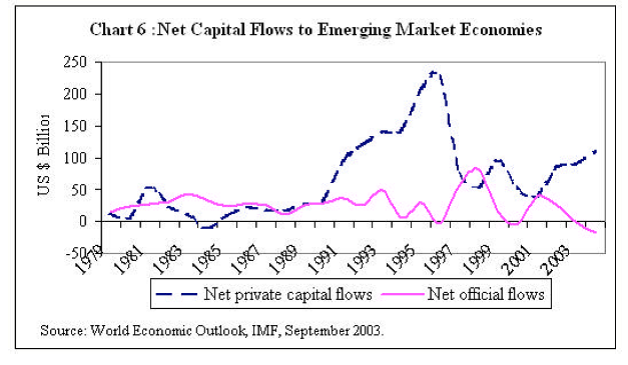

Investor confidence returned to the developing world in the early 1990s in the aftermath of the Brady Plan. Net capital flows surged to pre-1914 levels by 1996, temporarily slowed by the EMS crisis of 1992. The impact of the Mexican crisis of 1994 was absorbed by the large mobilisation of official financing which acted as a buffer. The composition of flows altered significantly, with private flows exceeding the official flows by the end of the 1980s. Whereas in the 1970s bank lending was the dominant component of capital flows to emerging markets, starting in the early 1990s, equity and bond investors became dominant. Over the last decade, portfolio investment exceeded bank lending in eight years. The range of investors purchasing emerging market securities broadened. Specialised investors such as hedge funds and mutual funds accounted for the bulk of portfolio inflows up to mid-1990s. In the subsequent years, pension funds, insurance companies and other institutional investors increased their presence in emerging markets. Although portfolio flows became important, it was FDI which accounted for the bulk of private capital flows to emerging market economies, going through a 6-fold jump between 1990 and 1997. International bank lending to developing countries increased sharply in this period, and was most pronounced in Asia, followed by Eastern Europe and Latin America. Much of the increase in bank lending was in the form of short-term claims, particularly on Asia.

In the late 1990s, capital flows to developing countries received severe shocks – first from the Asian crisis of 1997-98, then by the turmoil in global fixed income markets, and more recently by the collapse of the Argentine currency board peg in 2001 and the spate of corporate failures and accounting irregularities in 2002. Net flows to developing countries declined almost continuously after 1997 (Charts 6-8). The fall was particularly sharp in the form of bank lending and bonds, reflecting uncertainty and risk aversion. In 2002, net capital flows fell again, remaining far below the 1997 peak. Flows to Latin America reached their lowest level in a decade. Flows to Asia began a hesitant recovery with new bank lending exceeding repayments for the first time in five years. Global FDI inflows, down by 41 per cent in 2001, fell by another 21 per cent in 2002, attributable to weak economic growth, large sell-offs in equity markets, and a plunge in cross-border mergers and acquisitions. The USA and the UK accounted for more than half of the fall. Flows to Asia were held up by China.

Despite the global uncertainties, conditions for capital flows have improved in 2003. Sell-offs in international bond markets in June and July reflected upward revisions in investors’ expectations about growth prospects. Spillovers to credit and equity markets were limited. Emerging markets, in general, outperformed the mature markets. Some positive aspects of the roller-coaster of the last decade are: a steady consolidation of external debt by developing countries cushioned by the resilience of FDI, and the growth of local-currency bond markets as an innovation to manage credit risk.

The overall experience, however, is that capital flows are characteristically volatile, both in terms of longer term waves and even more so in the short term. The longer term waves influence monetary policy thinking during each era, whereas the short term volatility has to be met through day to day monetary policy operations.

The experience of living with capital flows since the 1970s has fundamentally altered the context of development finance. It has also brought about a drastic revision in the manner in which monetary policy is conducted. In particular, there is a dramatic shift in the still unsettled debate on the determinants of the exchange rate and the choice of the appropriate exchange rate regime, although the weight of opinion is clearly in favour of a flexible regime. According to conventional wisdom, it was trade flows which were the key determinants of exchange rate movements. Consequently, the degree of openness to international trade, price and non-price competitiveness and factors which determined market shares abroad were thought to have a crucial bearing on the level and the movement of the exchange rate. In more recent times, with the tail of mobile capital accounts wagging the dog of the balance of payments, the importance of capital flows in determining the exchange rate movements has increased considerably, rendering some of the earlier guideposts of monetary policy formulation possibly anachronistic. On a day-to-day basis, it is capital flows which influence the exchange rate and interest rate arithmetic of the financial markets. Instead of the real factors underlying trade competitiveness, it is expectations and reactions to news which drive capital flows and exchange rates, often out of alignment with fundamentals. Capital flows have been observed to cause overshooting of exchange rates as market participants act in concert while pricing information. Foreign exchange markets are prone to bandwagon effects. The effects of capital flows on the exchange rate are amplified by the fact that capital flows in ‘gross’ terms can be several times higher than the ‘net’ capital flows.

The experience with capital flows has important lessons for the choice of the exchange rate regime. The advocacy for corner solutions – a fixed peg a la the currency board without monetary policy independence or a freely floating exchange rate retaining discretionary conduct of monetary policy – is distinctly on the decline. The weight of experience seems to be tilting in favour of intermediate regimes with country-specific features, without targets for the level of the exchange rate, the conduct of exchange market interventions to ensure orderly rate movements, and a combination of interest rates and exchange rate interventions to fight extreme market turbulence. In general, emerging market economies have accumulated massive foreign exchange reserves as a circuit-breaker for situations where unidirectional expectations become self-fulfilling. It is a combination of these strategies which will guide monetary authorities through the impossible trinity of a fixed exchange rate, open capital account and an independent monetary policy.

Capital movements have rendered exchange rates significantly more volatile than before. For the majority of developing countries which continue to depend on export performance as a key to the health of the balance of payments, exchange rate volatility has had significant real effects in terms of fluctuations in employment and output and the distribution of activity between tradables and non-tradables. In the fiercely competitive trading environment where countries seek to expand market shares aggressively by paring down margins, even a small change in exchange rates can develop into significant and persistent real effects. For labour intensive export producers, volatility in exchange rate movements can easily translate into large losses of economic welfare. In the final analysis, the heightened exchange rate volatility of the era of capital flows has had adverse implications for all countries except the reserve currency economies. The latter have been experiencing exchange rate movements which are not in alignment with their macro imbalances and the danger of persisting currency misalignments looms large over all non-reserve currency economies.

The issue dominating the conduct of monetary policy and exchange rate policy today in countries such as India and China is that of excess of capital inflows. Are these flows resulting from temporary global imbalances emanating from current economic policies and problems of the G-3 countries? Or do they reflect global changes of a more lasting nature. It is to the consideration of this issue that I now turn.

V. Looking Ahead: Economic Demographics

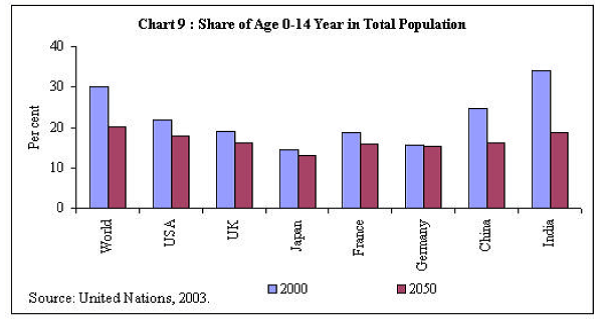

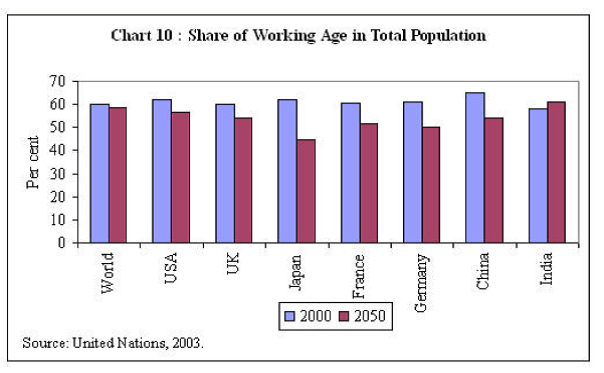

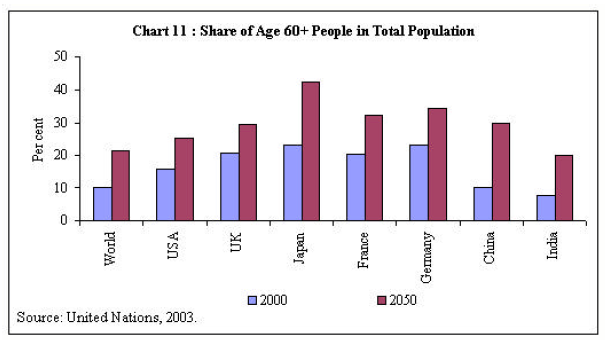

Some recent research has focussed on the macroeconomic effects of demographic patterns (Joshi and Sanyal, 2003; UN, 2003). Over the next half-century, the population of the world will age faster than during the past half-century as fertility rates decline and life expectancy rises. The proportion of children (0-14 years) is expected to decline from 30 per cent in 2000 to 20 per cent in 2050 whereas the proportion of the aged (60+ years) will double, reaching 21 per cent of the total population by 2050. The phenomenon of global ageing is likely to be associated with a progressive decline in saving rates and growth. In the interregnum, regional patterns of global population ageing are expected to bring about fundamental alterations in saving-investment balances which would be reflected in the magnitude and direction of international capital flows with implications for the conduct of future monetary policy.

In general, economies pass through three stages of demographic transition – (i) high youth dependency (large proportion of population in the 0-14 years group), (ii) rise in working age population (15-59 years) relative to youth dependency and (iii) rise in elderly dependency (60+ years) relative to working age population. The second stage is regarded as the most productive from the point of view of secular growth since it is associated with the highest rate of saving and work force growth relative to the other stages. So far, the more developed regions have been leading the process of population ageing and are likely to be deep into the third stage of demographic transition. In Europe, population ageing is most advanced and by 2050, this is projected to accelerate. Japan is currently the country with the oldest population; by 2050, it is expected to have the highest proportion of elderly people among industrialised nations (Government of Japan, 2003) (Charts 9-11). Projections suggest a turning point between 2010 and 2030 when the European Union, North America and Japan will experience a substantial decline in saving rate relative to investment which would be reflected in current account deficits. These regions will switch to importing capital.

Most of the high performers of East Asia and China are in the second stage of the demographic cycle. Elderly dependency is expected to double by 2025. Their working age populations will increase modestly and then shrink. These projections suggest that East Asia could increasingly become an important supplier of global savings up to 2025; however, rapid population ageing thereafter would reinforce rather than mitigate the inexorable decline of global saving. Increasingly it would be the moderate and the low performers among the developing countries which would emerge as exporters of international capital. India is entering the second stage of demographic transition and over the next half-century, a significant increase in both saving rates and share of working age population is expected. The share of the labour force in population is expected to overtake the rest of Asia, including China, by 2030.

In this scenario, the current phenomenon of overall surpluses in the balance of payments being run by several* emerging market economies, including India, may not be a temporary one. The largest reserve holding countries (excluding gold) in the world are emerging market economies. Monetary authorities in these countries are grappling with the expansionary effects of net foreign assets on domestic monetary conditions. Faced with the loss of control over the monetary aggregates, interest rates and exchange rates, almost all of these countries are engaged in devising innovative methods of sterilisation to delay the inevitable sacrifice of discretion in the conduct of monetary policy and its globalisation. The emerging patterns of demography indicate that this source of uncertainty for monetary authorities could become more significant than before.

The key challenge for macroeconomic policies would be to ensure that the anticipated expansion in saving in developing countries is productively utilised within the economy and not exported abroad. Accordingly, it is vital to ensure that the investment rate rises in close co-movement with the saving rate. Sustainable growth hinges around the existence of a critical minimum in terms of physical infrastructure. The acceleration of growth in the future requires massive investments to close the gaps between demand and supply in key infrastructural areas such as power, roads and highways, ports and telecommunication, cities and urban utilities. India, China and Indonesia, which account for more than a third of the world's population can be expected to continue urbanising over the next 20 to 40 years. During this period, the investment demand for resources emanating from these countries related to urbanisation will assume larger magnitudes. The history of urbanization has been that countries that undergo such growth in levels of urbanization - from around 25 to 30 per cent to around 50 to 60 per cent - typically have to attract external savings to supplement their own to satisfy the massive financing needs for infrastructure investment during this period. If the conjecture regarding the course of demography and associated savings pattern that I have just posited are correct, it is unlikely that the current low inflationary scenario will continue in the medium term to long term. It is also possible that the current phenomenon of increasing savings rates in Asian countries like India and China does not continue to be valid over the next medium to long term. If that happens, there could again be a reversal of capital flows. There would then be tightening of liquidity in world capital markets with increased competition for resources. Thus, there is no assurance that the current trends of excess liquidity accompanied by low inflation will necessarily continue in the world. Recent experience tells us that such reversals can occur very rapidly.

This will pose significant problems in the conduct of monetary policy for our countries in the years to come. The future growth strategy will also need to be more labour absorbing to accommodate the projected expansion in the work force. Reforms in the labour market, educational systems, pensions and medical care would gather importance within the overall intensification of structural reforms. Monetary policy would have to play an important role in bringing these forces together by ensuring appropriate real interest rates and low and stable inflation.

VI. The Emerging Challenges to Monetary Policy

There are many issues that are of relevance to emerging economies like India and Sri Lanka that are opening up. It would be useful to summarise some of these here.

In a world of generalised uncertainty, monetary policy has lost its traditional moorings. As a consequence, the conduct of monetary policy has become increasingly complex. The determinants of exchange rate behaviour have altered dramatically. Earlier, factors affecting merchandise trade flows and the behaviour of goods market provided proximate guides for operating monetary policy. In this environment, a monetary policy principally targeting low inflation was relevant and commodity purchasing power parities seemed to offer a satisfactory explanation of exchange rate changes. Since the 1980s, vicissitudes of capital movements have shown up in volatility in exchange rate movements with major currencies moving far out of alignment of underlying purchasing power parities. On a day-to-day basis, it is capital flows which move exchange rates and account for much of their volatility.

The impact of greater exchange rate volatility has been significantly different for reserve currency countries and for developing countries. For the former, mature and well-developed financial markets have absorbed the risks associated with large exchange rate fluctuations with negligible spillover on to real activity. Consequently, the central bank does not have to take care of these risks through its monetary policy operations. On the other hand, for the majority of developing countries, which are labour-intensive exporters, exchange rate volatility has had significant employment, output and distributional consequences, which can be large and persistent.

All this has made the operation of monetary policy more difficult and complicated. For developing countries, in particular, considerations relating to maximising output and employment weigh equally upon monetary authorities as price stability. A crucial objective of the development strategy is to stabilise the fluctuations of output and employment. Accordingly, in developing countries, it is difficult to design future monetary policy frameworks with only inflation as a single-minded objective. Thus the operation of monetary policy has to take into account the risks that greater interest rate or exchange rate volatility entails for a wide range of participants in the economy. Both the fiscal and monetary authorities inevitably bear these risks. The choice of the exchange rate regimes in developing countries, therefore, reveals a preference for flexible exchange rates along with interventions to ensure orderly market activity, but without targeting any level of the exchange rate. There is interest in maintaining adequate international reserves and a readiness to move interest rates flexibly in the event of disorderly market conditions. It needs to be recognised that most developing countries are engaged in the process of development and integration of financial markets. Consequently, signals from the market get blurred by the degree of management which is unavoidable in this transition.

The actual experience over the last two decades has been that with greater liberalization of the financial system, inflation has fallen and output volatility has moderated. Monetary policy has played an important role in taming inflation in the last two decades. A valuable lesson for an economy in the process of opening up is that increased globalization and competition has contributed predominantly towards containment of inflation. Thus countries’ perspective on inflation needs to be informed increasingly by world price trends, particularly in commodities of interest to them. With continued deregulation and globalisation, it is unlikely that there will be a reversal of the current trends in inflation. However, this is not to suggest that globalization is a solution for all problems. Any widespread relapses in the relatively favourable trends in globalization and deregulation, or relatively benign fiscal policies could reverse the achievement of recent years. An important consideration for reining inflationary expectations relates to the need to have clarity on price stability, effective communication, consistency in conduct of policy and transparency in explaining actions. Central banks should speak clearly to markets and listen to markets more carefully to ensure the intended objectives of policy.

There have been some negatives from the process of globalization in the form of greater prominence of credit and asset price booms and increasing incidence of financial crisis. The wave of financial liberalization has raised the risks in the financial system. The key policy challenge for an emerging economy would be to put in place mutually supportive safeguards to ensure both monetary and financial stability. The most important lesson for us is that financial imbalances can build up even when inflation is low and hence monetary policy should have a slightly longer time horizon in terms of inflation. Apart from the above, there are merits to all countries in greater transparency, combining simple rules with discretion and effective communication. Orderly development of financial markets can make a big difference regarding the manner in which risks and shocks make an impact on the economy. A flexible exchange rate regime imparts greater flexibility in monetary policy to deal with shocks more efficiently. On the prudential side, it would imply strengthening further the macro-prudential orientation. Monetary policy and prudential regulation should, therefore, co-exist. Greater transparency and cooperation between monetary policy and supervision has been increasingly recognised the world over and has resulted in many central banks publishing financial stability reports.

Although there is uncertainty about how economies operate and about monetary policy itself, uncertainty is no excuse for not pursuing price stability. In the pursuit of monetary goals, monetary policy authorities could adopt formal models and policy rules, informal target rules or case-by-case decision making. In practice, no central bank relies exclusively on formal models to derive final policy. Models assist central banks to take judgments. Furthermore, as Alan Greenspan recently commented, most of the formal models are vastly simplistic and despite efforts to quantify and capture more variables, they are inadequate. Their knowledge base is barely able to keep pace with the complexities of the world. The problem is not of the models but of the complexities of the world economy. An explicit numerical target is good for anchoring inflation but it comes at a cost. If the explicit inflation target cannot be achieved it weakens the credibility of the central bank. Thus it may not be appropriate to formulate monetary policy based on a simplistic inflation target or a single point inflexible point target as argued by many. The risks to the system can emanate from any variable, both exogenous and endogenous and policy makers response should be dynamic and contextual. Rules can, therefore, only be viewed as thoughtful adjuncts of policy but cannot be a substitute for risk paradigms. A case-by-case approach provides a simplistic framework for analysis. Ultimately, a central bank has to judge the outcome of the policy choices it makes and also take account of and anticipate market expectations, which have become increasingly important for the attainment of desirable outcomes.

To conclude, in a globalised world, it is not possible to formulate monetary policy independent of international developments. Monetary policy formulation has become more complex and interdependent. Continuous monitoring of financial markets, upgradation of technical skills at the central bank, flexibility and eternal watchfulness hold the key to making monetary policy matter in the evolving global environment. A key factor that guides the conduct of monetary policy is how to achieve the benefits of market integration while minimizing the risks of market instability. An integral component of central bank work is the development of financial markets that can increasingly shift the burden of risk mitigation and costs from the authorities to the markets. The adverse implications of excess volatility leading to financial crises are more severe for low-income countries. They can ill-afford the downside risks inherent in a financial sector collapse. Central banks need to take into account, among others, developments in the global economic situation, the international inflationary situation, interest rate situation, exchange rate movements and capital movements while formulating monetary policy.

References

- Eichengreen, Barry. "Can Emerging Markets Float? Should they Inflation Target?". Paper Presented to a Seminar at the Central Bank of Brazil. February 2002.

- European Central Bank. "Monetary Policy-Making under Uncertainty". Monthly Bulletin. Pp. 43-55. January 2001.

- Feldstein, Martin. "Monetary Policy in an Uncertain Economy". NBER Working Paper, 9969. September 2003.

- Government of Japan. "Annual Report on the Japanese Economy and Public Finance". October 2003.

- Greenspan, Alan. "Monetary Policy Under Uncertainty". Remarks at a Conference on "Monetary Policy and Uncertainty: Adapting to a Changing Economy" at Jackson Hole, WY. August 29, 2003.

- -------. "The Implications of Technological Changes". Remarks at the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce. July 10, 1998.

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook. September 2003.

- Joshi, Vijay and Sanjeev Sanyal. "India’s Opportunity". Business Standard, Mumbai. September 9, 2003.

- Khan, Mohsin S. and A.S.Senhadji. "Threshold Effects in the Relationship between Inflation and Growth". IMF Working Paper, WP/00/110. June 2000.

- Meltzer, Alan H. "On Making Monetary Policy More Effective Domestically and Internationally". In Iwao Kuroda, "Towards More Effective Monetary Policy". MacMillan Press Limited London. 1997.

- Ranagarajan, C. "Indian Economy: Essays on Money and Finance". UBS Publishers Ltd. 1998.

- Rogoff, Kenneth. "Globalisation and Global Disinflation". Paper presented at a Conference on "Monetary Policy and Uncertainty: Adapting to a Changing Economy" at Jackson Hole, WY. August 29, 2003.

- Stock, James H. and Mark W. Watson. "Has the Business Cycle Changed? Evidence and Explanations". Paper presented at a Conference on "Monetary Policy and Uncertainty: Adapting to a Changing Economy" at Jackson Hole. WY. August 29, 2003.

- United Nations. "World Population Prospects: The 2002 Revision. Highlights". United Nations. Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United National Secretariat, New York. 2003.

- World Bank. Global Development Finance. 2003

* Dr. Rakesh Mohan is Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India. He is grateful to Dr. Michael Patra, Dr. A. Prasad and Shri Muneesh Kapur of the Reserve Bank of India for their assistance.

पृष्ठ अंतिम बार अपडेट किया गया: