IST,

IST,

Chapter III: Monetary Policy Decision Making Process

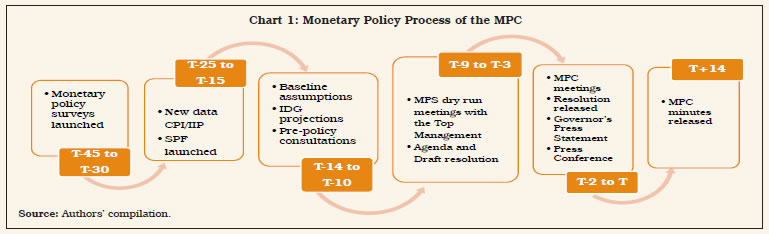

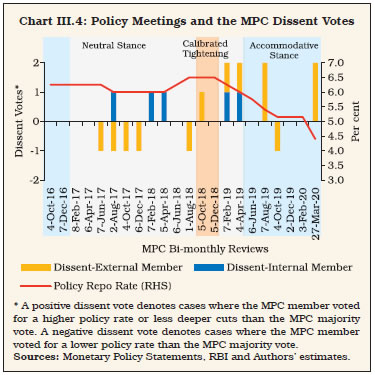

“The procedure, conduct, code of confidentiality and any other incidental matter for the functioning of the Monetary Policy Committee shall be such as may be specified by the regulations made by the Central Board.” [Section 45ZI (12) of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 III.1 The monetary policy decision making process in India has undergone a transformation with the adoption of flexible inflation targeting (FIT) in 2016. From a Governor-centric decision making to the vesting of this responsibility with a collegial Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), India has made a transition that is engaging a growing list of countries since the late 1990s.1 India’s MPC consists of three internal members – the Governor as the Chairperson, ex officio; the Deputy Governor in charge of monetary policy as Member, ex officio; and one officer of the Bank to be nominated by the Central Board as Member ex-officio – and three external experts appointed by the Central Government.2 III.2 De jure specifications of this process were set out in the RBI Act amended in 2016 and in the MPC and Monetary Policy Process Regulations, 2016 (Annex III.1). Its key features are as follows:

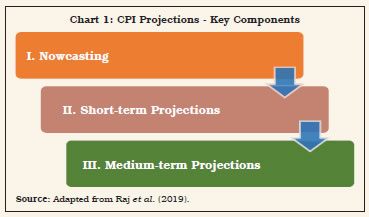

III.3 The preparation for the MPC’s bi-monthly meetings starts more than a month before the MPC meets, with the RBI setting in motion the launch of the monetary policy surveys, followed by the start of the inflation and growth projection process, consultations with key stakeholders, and preparation of the draft MPC resolution (Box III.1). III.4 The process of preparing projections by the RBI staff is structured into nowcasting, short-term, and medium-term projections (Box III.2).

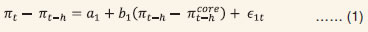

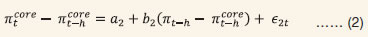

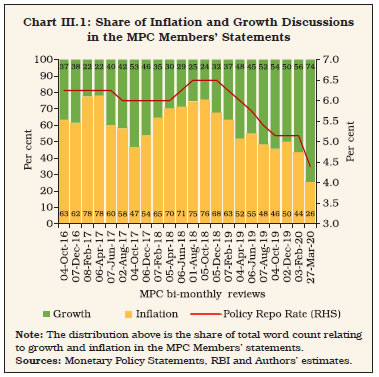

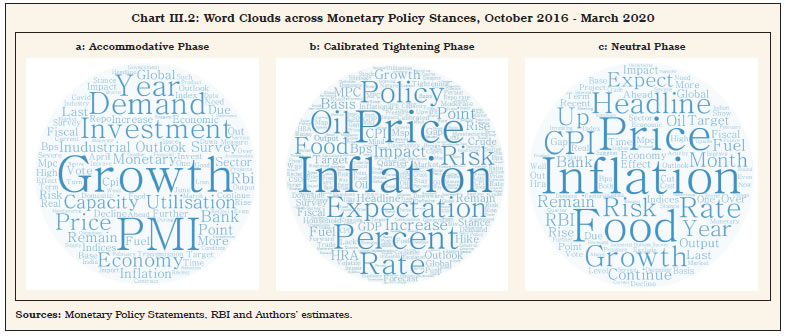

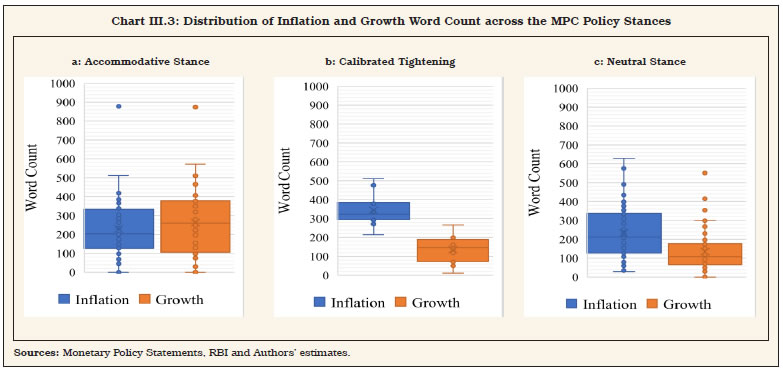

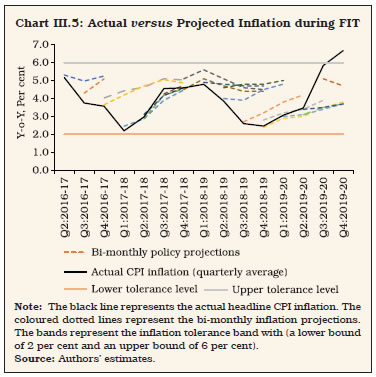

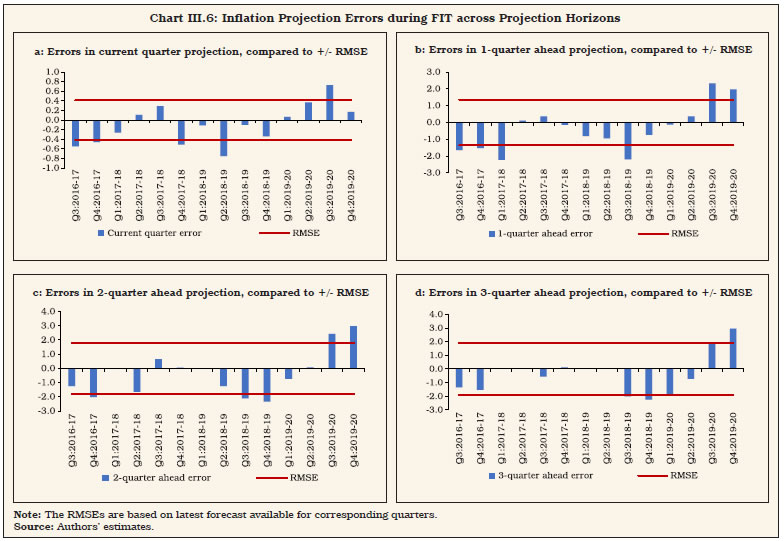

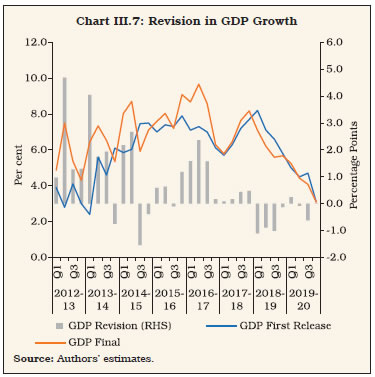

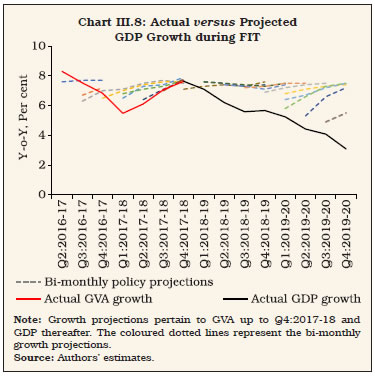

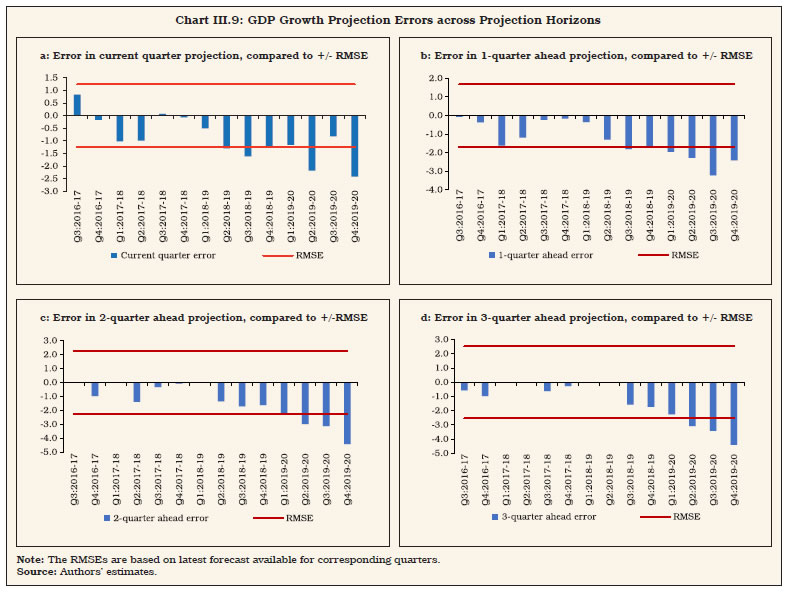

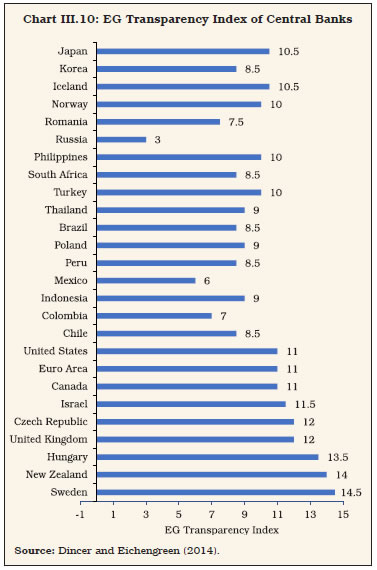

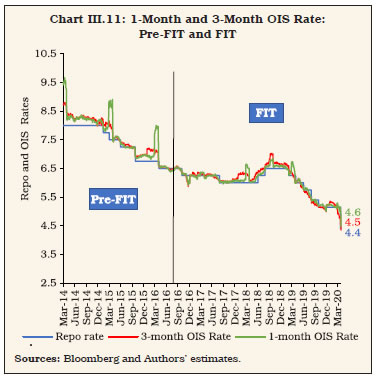

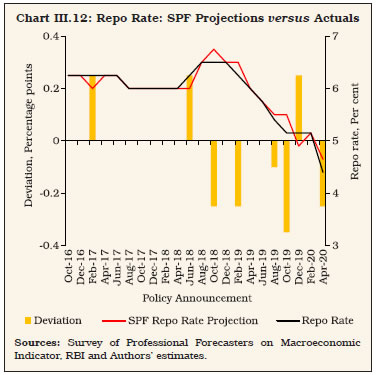

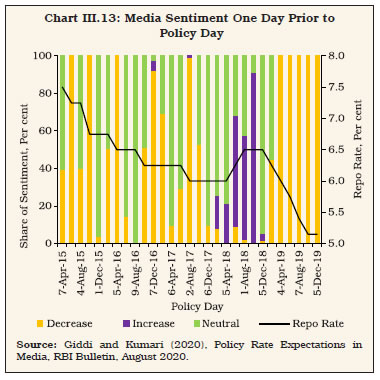

III.5 In the rest of the chapter, Section 2 sets out an analytical documentation of the MPC voting patterns, individual statements, diversity in the MPC deliberations and on the weights assigned by the MPC members to the monetary policy objectives of inflation and growth while arriving at their monetary policy decisions. Section 3 presents an evaluation of the growth and inflation projection processes along with an impact assessment of the MPC under the FIT on communication and transparency. Sections 4 and 5 present an evaluation of the MPC’s structure and processes, drawing on the experiences so far and from a cross-country perspective, centred on those aspects that have worked well and on those which can be reviewed for further refinement of the MPC processes. Section 6 concludes the chapter. 2. Experience with the MPC: Voting Patterns (2016-2020) III.6 Of the 22 meetings of the MPC during the period since its first meeting in October 2016 and until March 2020, all meetings barring the March 2020 meeting were held as per pre-announced bi-monthly schedules and all meetings were held with full attendance.7 III.7 The MPC has seen 11 different members over this period. While the three external members were constant, the internal members who were the MPC members ex officio, changed due to change in the persons holding the office. There were in all eight internal members.8 Government nominated Dr. Chetan Ghate, Professor, Indian Statistical Institute, Professor Pami Dua, Director, Delhi School of Economics, and Dr. Ravindra H. Dholakia, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad as the three external members on September 29, 2016 for a four year period. III.8 Voting records of individual members on the policy rate exhibited diversity. However, this typically pertained to the change in the policy rate rather than contesting the overarching policy stance (Patra, 2017). Divergence in voting was seen both for internal and external members with internal members being relatively more cohesive in their voting pattern than their external counterparts on both rate and stance decisions (Tables III.1 and III.2). III.9 Twelve of the 22 decisions of the MPC on the repo rate have been unanimous with respect to the direction of policy rate change. Within these 12 decisions, however, there were three decisions where the MPC differed over the quantum of the interest rate cut (Table III.3 and Annex III.2). III.10 The MPC has never seen a tie in monetary policy decisions and hence there was no recourse to a casting vote by the Governor as the Chairman of the MPC. The MPC Statements: Word Count and Text Mining Analysis III.11 In a FIT framework, it is the relative emphasis given to growth and inflation over various points of time by each MPC member which eventually determines the overall monetary policy stance and the decisions on the direction of key policy rate. As noted in Chapter I, the MPC since its inception in October 2016 had to grapple with several formidable challenges – demonetisation; shocks to inflation from volatile food and crude oil prices; growth slowdown; recurrent external shocks; and the COVID-19 pandemic. An analysis of the MPC minutes on the basis of a word count of inflation and growth in the MPC members’ statement, supported by text mining – with its results presented in the form of a word cloud – reflects the relative importance of the key words and phrases that dominated the MPC statements. Word Count Analysis III.12 During the period of initial accommodative stance from October to December 2016, inflation occupied more than 60 per cent of the growth-inflation discussions. By February 2017, however, inflation assumed centre stage in the MPC minutes, with the discussions on inflation accounting for 80 per cent of the total growth-inflation deliberations and coinciding with the change in stance of the monetary policy from accommodative to neutral. Thereafter, during June and October 2017, the relative emphasis on growth increased in the MPC statements and accounted for more than 50 per cent of the discussion space by October 2017. From December 2017, inflation discussions started getting higher emphasis in the MPC statements. During August to October 2018, more than 75 per cent of the MPC members’ discussion space was occupied by inflation concerns and mirrored the change in stance to calibrated tightening. III.13 With inflation registering sharp moderation since February 2019 and growth impulses weakening, the emphasis on inflation in the MPC members’ statements ebbed and the weight attached to growth rose. With the subsequent shift of monetary policy stance from neutral to accommodative and continuation of policy rate cuts, growth discussion predominately featured in monetary policy statements of members, occupying more than 50 per cent of discussion space until February 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic led the MPC to vote for a sharp reduction in the policy rate – by 75 basis points in March 2020 – and growth concerns were the focal point, occupying nearly 75 per cent of the discussions (Chart III.1). Text Mining and Word Cloud III.14 Text mining techniques involve computational tools and statistical techniques to quantify text to uncover the implicit focal variables. While the technique of text mining is widely applied in fields such as political science and marketing, its use in economics, particularly in central bank research, is relatively nascent (David Bholat, 2015; Paul Hubert et al., 2018; Bailliu et al., 2021). III.15 For the purpose of text mining analysis, the statements by the MPC members were pooled and processed9 across three distinct stances – neutral; calibrated tightening; and accommodative. Such a grouping of the MPC members’ statements shows that during the accommodative and calibrated tightening phases, the discussion space occupied by the words ‘inflation’ and ‘growth’ clearly justified the MPC’s stances. During the accommodative phases, the frequency of words related to growth was higher whereas the calibrated tightening stance period saw a clear shift, with discussion on inflation eclipsing that on growth. In the neutral stance phase, discussions gave primacy to inflation concerns, though growth was also in focus – more than what it was in the period of calibrated tightening (Chart III.2).  III.16 Box plots of word counts help to bring out the extent of cohesion and diversity among the MPC members. Each data point in the box plot depicts the relative importance given to growth and inflation (number of words spent on these discussions) by each MPC member across the 22 bi-monthly statements, grouped according to the policy stance. During the calibrated tightening stance, the median value of the word count on inflation was the highest along with the lowest inter-quartile range. Similarly, during the accommodative phase, word count on growth recorded a higher median value vis-à-vis inflation. However, the relatively wider inter-quartile range around growth during this phase also points to considerable divergence among the MPC members on the weightage assigned to growth. In the neutral stance phase, the relative importance given to growth and inflation by the MPC members varied widely as is seen from the high positive skew in the box plots of growth and inflation word counts. This ultimately showed up in their voting preference (Chart III.3).   Diversity and Dissent III.17 Heterogeneity in the MPC structures globally has reflected preferences, views of members and differences in skills and backgrounds all of which has imparted diversity in voting. This drives the Committee to adopt an eclectic approach which serves to limit the risk that a single viewpoint or analytical framework might become unduly dominant (Bernanke, 2007). These voting records also provide valuable information about agreement and dissent (Horváth, Smidková and Zápal, 2010). III.18 The neutral stance period of February 2017 to August 2018 witnessed the largest number of dissent votes, on account of the fast-changing growth inflation dynamics. The first dissent vote in June 2017 was by an external MPC member for easing of policy rates, when the MPC majority decision was to pause. In August 2017, dissent came from both internal and external members. The external member voted for larger policy rate reduction, while an internal member dissented in favour of maintaining status quo when the MPC majority reduced the policy rate. This was the only time in the 22-meeting voting history of the MPC that dissent votes were registered for two different policy options than the MPC majority decision. Further, in the October and December 2017 policies, an external member was in favour of a reduction in policy rate against status quo decision of the MPC. Contrastingly, in the next two policies in February and April 2018, when the MPC kept rates on hold, an internal member dissented and voted for an increase in policy rates. Thereafter in August 2018, when the MPC raised rates for the second time, one external member voted for status quo. III.19 During the calibrated tightening phase (October to December 2018), there was one dissent vote by an external member in the October policy for a rate increase against the MPC decision to keep rates on hold. The calibrated tightening phase also saw a dissent on the stance of monetary policy – an external member voted for a neutral stance in both these meetings. III.20 The second neutral stance phase that lasted for just two MPC meetings – February and April 2019 – witnessed considerable dissent, both on the policy rate action and on the policy stance. The MPC reduced rates amidst dissent from both internal and external members who favoured maintenance of status quo. In the April 2019 policy, an external MPC member had a divergent view on continuing with the neutral stance and voted to change it to accommodative. III.21 In the accommodative phase (June 2019 to March 2020) there were three instances of dissent – all by the external members. In August 2019, when the policy rate was reduced by 35 bps, two external members, while agreeing with the direction of rate change favoured a lower reduction of 25 bps. In October 2019 an external member voted for a larger reduction in the policy rate by 40 bps against the MPC consensus of 25 bps. In the March 2020 off-cycle policy, the MPC delivered a steep cut of 75 basis points, with two external members favouring a reduction of 50 bps. III.22 Over the 22 meetings, all the external MPC members expressed dissent at some meeting, with each member dissenting in the range of two to six occasions. Two internal members also diverged from the majority view, each on two occasions. Dissent votes in the case of the policy stance in three meetings were only by external members (Chart III.4, Table III.2 and Annex III.2).  III.23 Overall, the diversity index in Chapter I and internal-external member differences presented above showed considerable independence and confirms the absence of group think in the RBI’s MPC. 3. Evaluation of the Projection Performance, Communication and Transparency III.24 In a FIT framework, reliability of projections, effectiveness of communication and transparency of processes play a key role in its successful implementation. The following discussions quantify the MPC performance on these aspects. Evaluation of the Projection Performance III.25 Inflation and growth projection performance is reviewed on a regular basis at the RBI and its results are put in the public domain through publications. The bi-annual Monetary Policy Report (MPR), as mandated by the Statutes, presents the size of forecast errors and the factors that contribute to such errors. A detailed analysis of forecast errors is presented to the MPC in each of its bi-monthly meetings. III.26 Forecast performance can be evaluated on the basis of accuracy, unbiasedness, efficiency, and auto-correlation (Raj et al., 2019). Accuracy is measured as deviation of forecasts from realised values, measured as mean error, mean absolute error, and the root mean squared error (RMSE).10 Accuracy is formally verified by tests of unbiasedness which checks for any systematic under or overestimation, by regressing forecast errors on a constant term (Holden and Peel, 1990). Forecast efficiency is an evaluation of whether all information available at the time of forecasting is used. It is tested by regressing forecast errors on the most recently observed value of the forecasted variable.11 Significant levels of autocorrelation in forecast errors would indicate inefficient use of information on previous forecasting errors in the current forecast. This analysis is carried out for inflation and growth separately for different time horizons of forecasts, i.e., nowcasts and forecasts for one quarter, two quarters, and three quarters ahead. Inflation III.27 During the FIT regime, there have been episodes of both overestimation and underestimation of inflation. Inflation was occasionally overestimated during Q2:2016-17 to Q2:2019-20 (for three-quarters ahead inflation) and it was only in the subsequent quarters that there was some underestimation. In spite of sizeable forecast errors, the projected path of inflation remained within the tolerance band of 2 to 6 per cent (Chart III.5).  III.28 Initially narrow RMSE bands for nowcasts widened as the horizon increased up to three quarters (Chart III.6). III.29 Formal statistical tests indicate no systematic bias in inflation forecasts across all forecast horizons. The test for efficiency of forecasts shows that nowcasts and one-quarter ahead forecasts are efficient, i.e., all available information at the time of forecasting is used. However, the second and third quarter ahead forecasts are found to be statistically inefficient. While nowcast errors are not auto correlated, errors for longer forecast horizons are found to be auto-correlated.  GDP Growth III.30 India’s experience shows that GDP data are often revised and the direction and magnitude of revision changes over time (Chart III.7). It is also found that there is a tendency for revisions to be more on the upside at a time when the economy is registering an acceleration, while revisions are more on downside when the economy is undergoing a moderation (Prakash et.al, 2018). III.31 The RBI’s GDP growth projection performance during the FIT period shows persistent overestimation of GDP growth since Q4:2017-18 (Chart III.8) for all forecast horizons under consideration.   III.32 The degree of overestimation in terms of the RMSE band has been high in the recent period (Chart III.9).  Gauging Process Transparency III.33 Greater transparency in monetary policy making is one of the most notable features differentiating central banking of today from the past (Eijffinger and Geraats, 2006; Dincer and Eichengreen, 2007; 2014; and Geraats, 2006). Transparency is seen as a key element of accountability in an era of central bank independence. Central bank transparency is also seen as a way of enabling markets to respond more smoothly to policy decisions. The Eijffinger and Geraats index or EG index distinguishes five aspects of monetary policy transparency (Eijffinger and Geraats, 2006):

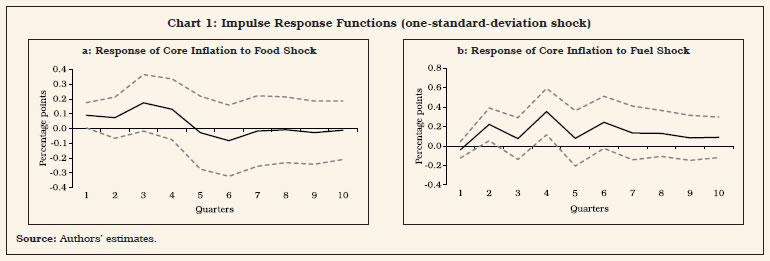

III.34 As per Dincer and Eichengreen (2014), the Riksbank, Sweden, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Central Bank of Hungary, the Bank of England and the Czech National Bank were the five central banks with the highest scores for transparent monetary policy (Chart III.10).  III.35 An EG transparency index for India shows that there was a notable enhancement in transparency of the monetary policy process with FIT. The EG index rose from 6 to 12, a level close to that of the advanced economies (Table III.4). III.36 Separate estimates for monetary policy transparency in India also show notable improvement post adoption of FIT (Samanta and Kumari, 2020). In these estimates, the EG transparency index moved from a low of 6 to 8.5 during October-December 2013 to reach 12 to 13 in October-December 2019. Communication by RBI’s MPC: Has It been Effective? III.37 Communication is an important element in a central bank’s monetary policy tool kit. The rationale for transparency in communication lies in helping economic agents gauge the current and future economic outlook of the MPC so that they can form their own expectations. The interest rates on financial market instruments are closely related to the current level and future expectations of the RBI’s repo rate. One measure of monetary policy expectations is the overnight indexed swap (OIS) rate. One to 24-month US, euro-zone and Japanese OIS rates and one to 18-month UK OIS rates tend to accurately measure expectations of future short-term interest rates (Lloyd, 2018). In the case of India, the 1-month and 3-month OIS rate shows that interest rate expectations are better anchored during FIT than in the pre-FIT period (Chart III.11).12 III.38 The RBI’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) on macroeconomic indicators also cover expectations on changes in the policy rate. By and large, it projected the policy direction correctly, although there were more downward surprises than upward surprises during the 22 policy meetings (Chart III.12).   III.39 An analysis of historical newsfeed from media on the RBI’s policy repo rate by Giddi and Kumari (2020), to capture media expectations one day prior to the policy announcement reveals that for most of the period under consideration, media sentiments were directionally in line with the actual policy rate decisions (Chart III.13). III.40 The practical experience of working with the MPC reveals several features which have stood the test of time and need to be persevered with. The Institutional Architecture III.41 Setting up a monetary policy committee for monetary policy decision making in India is in line with the global consensus. Since the late 1990s, there has been a decisive preference for a committee structure, with the MPC being the norm with all countries that adopted FIT during this period. Several committees in the past have also recommended an MPC for monetary policy decision making in India (RBI, 2014).  III.42 Data on MPCs in over 30 countries from 1960 to 2006 reveal a U-shaped relationship between the MPC size (both de jure and de facto) and inflation, with very small or very large groups leading to higher than necessary rates of inflation and inflation variability. Medium sized MPCs with about five to nine members were estimated as optimal (Berger and Nitsch, 2011 and Maier, 2007). The largest MPC is that of the National Bank of Poland with 10 members. The smallest MPC is a five-member committee in Chile, Iceland, and Norway. For all countries under study, the modal committee size is of seven members. In terms of composition mix between internal and external members, on an average, 48 per cent of the members were external with the number of external members ranging from zero to nine (Table III.5). From the above cross-country perspective, the committee size and composition of the MPC in India appears to be in line with the global best practices. The Decision Making Process III.43 Globally, the striking difference among the MPCs is in terms of their decision making process i.e. either by voting or by consensus. The design of decision making processes in a committee structure ranges from an ‘individualistic MPC’ model – where each member express opinion freely and decisions are made based on majority voting – to a fully ‘consensus-based MPCs’ where decisions are ultimately ascribed to the group as a whole and is owned up by each MPC member, even though members may argue behind closed doors for their respective points of view. Another variant of consensus based MPC could be the autocratically-collegial’ MPC where the chairman more or less dictates the group ’consensus’ and the group’s decision is essentially the chairman’s decision, informed by the views of the other committee members (Blinder and Wyplosz, 2004). An analysis of 28 central banks suggests voting is the overwhelming preference, with 24 central banks following a voting based monetary policy decision making process. The MPC in India also falls into the category that takes decision by voting (Table III.6). Communication III.44 The monetary policy communication practices in India mirror global experiences wherein most central banks publish their analysis of economic conditions, including outlooks for growth and inflation with central banks explaining the reasons for their policy decision through press conferences. The release of the MPC minutes two weeks after the policy by the RBI is also in line with international best practices (Table III.7), although, under India specific conditions, there is a risk of public perception of new data releases post the MPC’s meeting influencing these minutes. Accordingly, the requirement of the Act to release the minutes “… at 5 pm on the 14th day from the date of the policy day …” could be reformulated to “… at 5 pm within seven days from the date of the policy ….”. This would require amendment to the RBI Act. Accountability of the MPC III.45 Section 45ZN of the RBI Act enables the Central Government to set out the definition of failure to meet inflation target as well as accountability measures in case of failure. As per sub-sections (a), (b) and (c) of Section 45ZN of the RBI Act, when the Bank fails to meet the inflation target, it is required to set out in a report to the Central Government – (a) the reasons for failure to achieve the inflation target; (b) remedial actions proposed to be taken by the Bank; and (c) an estimate of the time-period within which the inflation target shall be achieved pursuant to timely implementation of proposed remedial actions. In the event of failure of the RBI to meet the inflation target, in accordance with the Regulation 7 of the RBI MPC and Monetary Policy Process Regulations, 2016, a separate meeting is required to be scheduled by the Secretary to the Committee, as part of the normal policy process to discuss and draft the report to be sent to the Central Government. The Report is required to be sent to the Central Government within one month from the date on which the Bank failed to meet the inflation target. III.46 Globally, as in the case of India, accountability mechanisms for monetary policy are usually enshrined in central bank Acts. They take the form of (a) ‘parliamentary hearings’ in a structured reporting to the Parliament on monetary policy; or (b) ‘open letters’ addressed by the Governor/Bank/MPC to the Government. The open letter, which explains the reasons for monetary policy failing to meet the inflation target, the remedial actions proposed and a time-frame to reach back to the target, are seen as part of the communication and accountability process, and not a ‘censure’ on the central bank (Hammond, 2012). As per the RBI Act, in the case of failure to meet the target, the RBI is mandated to write a report to the Central Government. Among the countries surveyed, open letters are more prevalent in central banks with MPC structures. In addition to open letters, some central banks also have parliamentary hearings (Table III.8). In India, the RBI reports to the Central Government, therefore, the accountability for failure through a report to the Central Government is the appropriate procedure. Code of Conduct of the MPC Members III.47 The Regulation 5(ii) of the RBI MPC and Monetary Policy Process Regulations provides broad guidance to members of the MPC on their ethical conduct to help enhance public trust and confidence in the RBI and its policies. The Members, inter alia, are expected to be guided by the objectives of monetary policy set out in the Act and the inflation target set by the Central Government; and independently and candidly express their views in the MPC meetings before voting. Members are also expected to take adequate precautions to ensure utmost confidentiality of the MPC’s policy decision before it is made public, preserve confidentiality about the decision-making process and maintain the highest standards of probity consistent with public office. While interacting with profit-making organizations or making personal financial decisions, they shall weigh carefully any scope for conflict between personal interest and public interest. III.48 International central bank policies show that to avoid conflict of interest and retain independence, external members in a monetary policy committee are restricted from certain activities or affiliations outside the central bank. Generally, they include restrictions on involvement in financial institutions, political activity, and government service (Patra and Samantaraya, 2007). III.49 As per the RBI Act, external member on the MPC cannot be a public servant, or Member of Parliament or any State Legislature. The Central Government can remove an MPC member from office on certain conditions, e.g. if the member is adjudged as an insolvent; is physically and mentally incapable; fails to adequately disclose any material conflict of interest at time of appointment; is not able to attend three consecutive meetings of the MPC; is convicted of an offence which, in the opinion of the Central Government, involves moral turpitude; or has such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions as a Member. These guidelines on code of conduct for the MPC members are in line with the ethical standards set out by other countries for the MPC. III.50 Based on the experience in India so far and cross-country best practices, there is scope for some refinements to the MPC’s decision making process for improvement in transparency, accountability and operational efficiency. Shut Period III.51 Members of the RBI’s MPC observe a silent or blackout period, starting seven days before the voting/decision day, and ending seven days after the day policy is announced. During this period, the MPC members avoid public comments on issues related to monetary policy, other than through the MPC’s communication framework to avoid market volatility and weakening of transmission of policy signals. III.52 Among the central banks surveyed, there is a shut period for all the members of the Board/MPC of around a week to 10 days before the date of monetary policy decision. In the case of Bank of Japan, the shut period is only for two days before the meeting. In most cases the shut period ends after the announcement of the monetary policy decision (Table III.9). III.53 The current practice in India of a 7-day shut period after the release of the MPC resolution is not aligned to the global best practice. Hence, a more flexible approach, with the shut period for the MPC starting seven days before policy announcement and ending three days after the policy is announced may be considered. Maintaining a shut period for three days after the policy announcement would felicitate clear and effective communication of the monetary policy decisions by the Governor. Staggered Onboarding of Members III.54 As per the extant statutory design, the 6-member MPC of the RBI undergoes a major change every four years as three external members, who are appointed for a fixed period of four years, are not eligible for reappointment after completing their term. III.55 Cross-country experience suggests that a committee structure with staggered terms of office creates checks and balances that moderate political influences on monetary policy (Blinder 2006). Staggering the terms of committee members also helps to achieve greater credibility (Vandenbussche, 2006). III.56 Of the 28 countries surveyed, most of the central banks, with either an MPC or a Board structure, follow staggered onboarding of members (Table III.10). This is usually achieved by instituting different tenures at the start of the staggered onboarding process. ECB in its appointment for the first Board in 1998, onboarded members with varying tenures. One of the central bank that recently staggered appointment of external members is South Korea. Though the term of the external members in the monetary policy board is four years, to bring about staggering, of the four members appointed in April 2020, two were appointed for three years and another two for a four-year term. In the case of New Zealand, in the first MPC constituted in 2019, the three external members were onboarded for varying tenures. Two members were appointed for a three-year term and one member for a four-year term. III.57 While the appointment of new external members on the RBI’s MPC in 2020 has not posed any disruptions to the decision making process, the global practice univocally suggests staggering for the MPC members with external members appointed for different tenures at the first instance of the start of the staggered onboarding process. This would require an amendment to the RBI Act. Transcripts of the MPC meetings III.58 As per the RBI Act, the proceedings of the MPC meeting will be confidential. During the MPC meetings, no transcripts of the meeting are recorded as per the extant practice. III.59 The global practice suggests that several central banks record transcripts of the deliberations in the monetary policy meetings. There are different practices, however, on release of these transcripts. The Bank of England releases minutes on the day after the meetings but withholds transcripts for 7-8 years. The US Federal Reserve releases minutes and transcripts of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings after a 3-week and 5-year lag, respectively. With a view to enhancing accountability and credibility, and for historical analysis, transcripts of the MPC meetings may be recorded at a future date as the MPC process and structure matures over time. These transcripts may be released in the public domain with a lag of 5-7 years. The MPC Communication Policy Document III.60 Inflation targeting has been viewed as a framework for making and communicating decisions (King, 2005). Any decision taken by the central bank has to be backed by communication (Das, 2019). The focus of the RBI’s monetary policy communication has been to give greater clarity on what informs monetary policy decisions and to be as transparent as possible. Under the inflation targeting framework, the primary means of monetary policy communication is the monetary policy resolution of the MPC that is released shortly after the conclusion of the MPC meeting and the minutes of the MPC released on the 14th day after the meeting. III.61 Apart from the above forms of written communication, the Governor’s press statements; interactions with media, researchers, and analysts; and speeches are also forms of formal communication. III.62 While there are structured forms of communication by the MPC, there is no formal communication policy document that lays out the communication policy for the MPC. Globally, most of the leading central banks publish an MPC communication policy document (Table III.11). III.63 Drawing from the global best practices, a model communication policy document for the MPC has been prepared, which lays out the do’s and dont’s of communication policy for the MPC and includes, inter alia, the written forms of communication and broad guidance on other forms of communication by the MPC (Annex III.4). Based on similar lines, a communication policy document for RBI’s MPC may be considered. Timing of Release of the MPC Resolution III.64 The monetary policy announcements by most FIT countries are made at a pre-announced calendar that includes the date and time of policy announcement and press conference (Table III.12). In the case of India, under the FIT regime, the annual calendar is announced before the first meeting of the financial year, while the time for release of the policy resolution and press conference over the years varied – from 10 am to 2:30 pm. To provide certainty to markets, the announcement of the policy can be at a time that is fixed (barring exceptional circumstances) and pre-announced. Publication of Interest Rate Path III.65 As part of the monetary policy communication strategy and transparency measures, the inflation and growth projections, usually in the form of fan charts, are published by all major FIT central banks. In addition, a growing number of FIT central banks are publishing forward guidance and projections of the interest rate path. One of the key considerations in publishing a conditional interest rate path comes from the central role played by interest rate expectations in reinforcing monetary policy transmission. This would be beneficial to preserve monetary policy credibility in episodes of large supply shocks to show that maintenance of the inflation target over the medium term does not require abrupt changes in interest rates. The interest rate guidance could be descriptive in nature or in the form of a fan chart of interest rate path. Such interest rate guidance are conditional interest rate paths i.e., conditional on information available at the time of the policy review and would change as new information is made available. Among the major central banks surveyed, four central banks provide explicit interest rate paths in the form of fan charts and six central banks provide descriptive interest rate path outlooks (Table III.13). In most central banks, publication of interest rate path has come about after FIT has been well established. III.66 The RBI’s MPC may consider providing a more explicit forward guidance on the interest rate path at a future date, as the projection process is strengthened further over time. Definition of Failure of the MPC III.67 Failure of the MPC in meeting its objective, as part of accountability measures, is generally defined as when inflation deviates from the target rate or a tolerance band for a specified period. Cross country experience shows failure is usually defined in terms of deviations of the inflation rate from the target rate or tolerance threshold. However, in many central banks, especially in EMEs, which often face food and fuel price spikes and have a high share of food and fuel in the CPI basket, failure is also conditional on inflation exceeding the tolerance threshold over a specified duration of time rather than immediately (Table III.14). III.68 In India, as per the RBI Act, the Central Government has notified the definition of failure as average headline CPI inflation more than the upper tolerance level or less than the lower tolerance level for three consecutive quarters. Since the adoption of FIT, between October 2016 and March 2020 there has been no failure by the MPC as per this definition. However, frequent occurrence of supply side shocks engendering sharp volatility in food inflation had been a recurring refrain during the FIT period so far and has been identified as a major reason for headline CPI inflation projection errors (Raj et al. 2019). In respect of several food items, inflation has deviated from the upper tolerance band (6 per cent) for more than three consecutive quarters (Table III.15). Often the occurrence of a series of transitory food price shocks in a sequential manner caused food price spikes to take time to revert. For example, in the case of vegetables prices, it took exactly nine months (October 2017 to June 2018) for inflation to return to the tolerance band. III.69 On the other hand, many food items have had frequent price crashes in the FIT period which took several months to get back to precincts of the target, especially in cereals, pulses and sugar. Pulses and sugar inflation remained below 2 per cent consecutively for 30 months and 21 months, respectively. This along with downward pull from other subgroups such as vegetables and fruits resulted in food inflation dipping below 2 per cent for 10 consecutive months between July 2018 and April 2019 (Table III.16). III.70 The volatility observed in food inflation due to transitory factors had limited spillovers to core inflation (Box III.3). However, persistent and permanent food and fuel price shocks necessitate timely monetary policy response to mitigate risks from second round effects and inflation expectations. All this requires greater flexibility to monetary policy and the MPC to see through sharp movements in food prices brought about by transient factors while, at the same time, be cognizant of relative price shocks that have a bearing on core inflation trajectory. A definition of failure that balances these two objectives would help prevent volatility in output growth brought about by policy responses to frequent food price spikes. This is also important considering the fact that even if monetary policy reacts promptly to non-transitory supply shocks to bring inflation back into the tolerance band, it takes up to 10 quarters for full transmission of policy impulses to inflation outcomes (see Chapter IV for further details). III.71 Given these India-specific experiences and concerns, it may be appropriate to revise the definition of failure from the current three-quarter horizon. Failure may be redefined as inflation overshooting/undershooting the upper and lower tolerance bands around the target for four consecutive quarters.

III.72 Being a late entrant to the club of countries that have been practicing monetary policy making in an FIT framework since the 1990s, India adopted the best practices and procedures for the decision-making process. III.73 The endeavour of the individualistic MPC of the RBI (where decisions are based on majority voting), over its first 22 meetings since October 2016, has been to enrich policy making by bringing in intellectual depth and individual expertise tempered by reasoning and deliberations on diverse and sometimes contrary views. Since October 2016, the MPC has seen it all – transitioning through various stances – from neutral to accommodative to calibrated tightening; shifting from rate hikes to cuts and pauses; moving from unanimous decisions to divided views; and dissenting from the consensus view by both external and internal members. However, the need for casting vote by the Governor was never required to be exercised. By all metrics, there has been an absence of group think and there were no free riders. With the change in the institutional architecture for conduct of monetary policy after the amendment of the RBI Act, there has been significant enhancement in transparency of the monetary policy process. III.74 Based on the learning from the first four years of FIT and a review of the global practices, this chapter has recommended refinements in the framework to make it more relevant and operationally efficient. They include limiting the shut period for the MPC to start seven days before policy announcement and end three days after the day policy is announced; staggering onboarding of external members on the MPC; having an official communication policy document for the MPC; releasing minutes within a week after the policy announcement; releasing policy at a pre-fixed and pre-announced time; maintaining the transcripts of the MPC meetings and its release with a lag of 5-7 years at a future date; providing a more explicit forward guidance on the interest rate path at a future date, as the projection process is strengthened further over time; and modifying the definition of failure from the current three consecutive quarters norm of inflation remaining outside the tolerance band to four consecutive quarters. References Aldridge, T., and Wood, A., (2014), “Monetary Policy Decision-making and Accountability Structures: Some Cross-country Comparison”, Reserve Bank of New Zealand: Bulletin, Vol. 77 (1), 15–30. Bailliu, J., Han, X., Sadaba, B., and Kruger, M., (2021), “Chinese Monetary Policy and Text Analytics: Connecting Words and Deeds”, Bank of Canada, Staff Working Paper, No. 3. Bank for International Settlements (2019), “Monetary Policy Frameworks and Central Bank Market Operations”, MC Compedium, October. Barrionuevo, J., (1993), “How Accurate are the World Economic Outlook Projections?” Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook. Washington D.C. Berger, and Nitsch, (2011), “Too Many Cooks? Committees in Monetary Policy Making”, Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 78(2), 452–475. Bernanke, B., (2007), “Federal Reserve Communications”, Speech at the Cato Institute 25th Annual Monetary Conference, Washington DC, November 14. Bholat, D., Hansen, S., Santos, P., and Schonhardt-Bailey, C., (2015), “Text Mining for Central Banks: Handbook”, Centre for Central Banking Studies (33), pp. 1-19. ISSN, Bank of England. Blinder, A., (2006), “Monetary Policy by Committee: Why and How?” DNB Working Paper, No. 92. Blinder, A., and Wyplosz, (2004), “Central Bank Talk: Committee Structure and Communication Policy”. Das, S., (2019), “$ 5 Trillion Economy: Aspiration to Action”, Keynote address delivered at the India Economic Conclave. Dincer, N., and Eichengreen, B., (2007), “Central Bank Transparency: Where, Why and with What Effects?”, National Bureau of Economic Research, WP No. 13003. Dincer, N., and Eichengreen, B., (2014), “Central Bank Transparency and Independency: Updates and New Measures”, International Journal of Central Banking. Dua, P., (2020), “Monetary Policy Framework in India”, Indian Economic Review, Vol. 55, 117-154. Eijffinger, S., & Geraats, P., (2006), “How Transparent are Central Banks?” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 22, 1-21. Fildes, R., and Stekler, H., (2002), “The State of Macroeconomic Forecasting”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Volume 24, Issue 4, 435-468. Geraats, P., (2006), “Transparency of Monetary Policy: Theory and Practice”, CESifo Economic Studies, Vol. 52(1), March 2006, 111-152. Giddi, G., and Kumari, S., (2020), “Policy Rate Expectations in Media”, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, August 2020. Government of India (1934), The Reserve Bank of India Act. Guillermo, O., (2009), “Issues in the Governance of Central Banks: A Report from Central Bank Governance Group”, Bank for International Settlement (BIS). Hammond, G., (2012), “State of Art of Inflation Targeting”, Centre of Central Banking Studies, Bank of England. Holden, K., and Peel, D. A., (1990), “On Testing for Unbiasedness and Efficiency of Forecasts”, The Manchester School, Vol. 58, 2. Horváth, R., Smidková, K., and Zápal, J., (2010), “Dissent Voting Behaviour of Central bankers: What do We Really Know?” Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Hubert, P., and Labondance, F., (2018), “Central Bank Sentiment”, https://ssl.nbp.pl/badania/seminaria/14xi2018.pdf. Khan, A., (2017), “Central Bank Legal Frameworks in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis”, IMF Working Paper, No. 101. King, M., (2005), “Monetary Policy: Practice Ahead of Theory”, Lecture delivered on 17 May 2005 at the Cass Business School, City University, London. Ciżkowicz-Pękała, M., Grostal, W., Niedźwiedzińska, J., Skrzeszewska-Paczek, E., Stawasz-Grabowska E., Wesołowski, G., Żuk, P., (2019), “Three Decades of Inflation Targeting”, NBP Working Paper, No. 314. Maier, P., (2007), “Monetary Policy Committees in Action: Is There Room for Improvement?”, Bank of Canada Working Paper, No. 06. Maurin, Vincent, Vidal and Jean-Pierre, (2012), “Monetary Policy Deliberations: Committee Size and Voting Rules”, ECB Working Paper, No. 1434. Oller, L., and Barot, B., (2000), “The Accuracy of European Growth and Inflation Forecasts”, International Journal of Forecasting, Vol. 16 (3), 293-315. Patnaik, I., and Pandey, R., (2020), “Four Years of the Inflation Targeting Framework”, NIPFP Working Paper Series, No. 325. Patra, M.D., (2017), “One Year in the Life of India’s Monetary Policy Committee”, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, December 2017. Patra, M.D., and Samantaraya, A., (2007), “Monetary Policy Committee: What Works and Where”, Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, Vol. 28(2). Pons, J., (2000), “The Accuracy of IMF and OECD Forecasts for G7 Countries”, Journal of Forecasting, J. Forecast. Vol.19, 53-63. Prakash, A., Shukla, A., Ekka, A., Priyadarshi, K., (2018), “Examining Gross Domestic Product Data Revisions in India”, Reserve Bank of India Mint Street Memo, No. 12. Price, G., and Wadsworth, A., (2019), “Effective Monetary Policy Committee Deliberation in New Zealand”, The Reserve Bank of New Zealand: Bulletin, April 2019. Raj, J., Kapur, M., Das, P., George, A., Wahi, G., Kumar, P., (2019), “Inflation Forecasts: Recent Experience in India and a Cross-Country Assessment”, Reserve Bank of India Mint Street Memo, No. 19. Reid, G., (2016), “Evaluating the Reserve Bank’s Forecasting Performance”, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Reserve Bank Bulletin, Vol. 79(13). Reserve Bank of India (2014), Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (Chairman: Dr. Urjit Patel). Reserve Bank of India (October 2016 – March 2020), Monetary Policy Statements, various issues. Reserve Bank of India (2016), The Monetary Policy Committee and Monetary Policy Process Regulations. Reserve Bank of India (2020), Annual Report (2019-20). Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2013), Monetary Policy Decision-making Framework Information Release, www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/informationreleases/monetarypolicy/framework Samanta, G. P., and Kumari, S., (2020), “Monetary Policy Transparency and Anchoring of Inflation Expectations in India”, Reserve Bank of India Working Paper Series, No. 3. Simon, P., (2018), “Overnight Index Swap Market-Based Measures of Monetary Policy Expectations”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No. 709. Vandenbussche, J., (2006), “Elements of Optimal Monetary Policy Committee Design”, IMF Working Paper, No. 277. Annex III.1: Monetary Policy Committee – Statutory Provisions on Processes The key features of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) processes as envisaged by the amended RBI Act, 1934 and the MPC and Monetary Policy Process Regulations, 2016 are as follows: The Regulatory Framework The Institutional Architecture Composition and size of the MPC The Central Government constitutes a six-member MPC with the Governor as the Chairperson, ex officio; the Deputy Governor in charge of monetary policy as Member, ex officio; one officer of the Bank to be nominated by the Central Board, Member ex officio; and three persons appointed by the Central Government as Members. The Central Government appoints external members based on the recommendations made by a search-cum-selection committee “from amongst persons of ability, integrity and standing, having knowledge and experience in the field of economics or banking or finance or monetary policy”. These members are required to be less than 70 years of age at the time of appointment. The external members hold office for a period of four years and are not eligible for re-appointment. [Section 45ZB and clause (d) of section 45ZB (2)] Secretary to the MPC The RBI Act, 1934, provides for the Bank to appoint a Secretary to the MPC for providing secretariat support to the MPC. The head of the Monetary Policy Department (MPD) is appointed as the Secretary to the committee. In his/her absence, the representative nominated by him/her not below the rank of senior officer in MPD functions as the Secretary. MPD assists the MPC with analytical and data requirements for meetings; prepares the resolution and statements by the MPC members. [Section 45ZG and Regulation 4(i)] Function of the MPC The RBI Act states that the Monetary Policy Committee shall determine the Policy Rate required to achieve the inflation target and decision of the Monetary Policy Committee shall be binding on the Bank. [Clause 3 and 4 of Section 45ZB] The Decision-Making Process of the MPC Planning Meetings Scheduled meetings: The Bank shall organise at least four meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee in a year. To help the MPC members plan for the meetings and for information of the markets, the schedule of monetary policy voting/decision meetings for the entire fiscal year is announced in advance. [Section 45ZI and Regulation 5(i)(a)] Emergency meetings: Ordinarily not less than fifteen days’ notice shall be given to the members for meetings of the Committee. However, in the case of exigency, there are provisions to arrange an emergency meeting at 24 hours’ notice to enable every member to attend. With technology enabled arrangements in place, meetings can be convened at even shorter notice period [Clause 3(b) of Section 45ZI and Regulation 5(i)(b)] Frequency of meetings: The MPC must hold at least four meetings in a year. In practice, the MPC conducts six meeting a year at bi-monthly frequency. [Section 45ZI (1)] Meeting Structure Quorum and Presider: The quorum for having a meeting of the MPC is of four members, at least one of whom is the Governor and, in his absence, the Deputy Governor who is the Member of the Monetary Policy Committee. The meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee would be presided by the Governor, and in his absence by the Deputy Governor who is a Member of the Monetary Policy Committee. [Clause 5 and 6 of the Section 45ZI] Voting: All questions which come up before any meeting of the MPC to be decided by a majority of votes by the Members present and voting, and in the event of an equality of votes, the Governor has a second or casting vote. [Clause 8 of the Section 45ZI] The MPC Communications Publication of Decision: After the conclusion of every MPC meeting, the Bank publishes the resolution adopted by the said Committee. The resolution includes the macroeconomic assessment and outlook of the MPC and its decision on the policy repo rate. [Section 45ZK] Minutes of the MPC: The minutes of every MPC meeting are published on the 14th day after the MPC meeting. The minutes of the proceedings of the meeting must include: (a) the resolution adopted by the MPC; (b) the vote of each member of the Monetary Policy Committee, ascribed to such member, on resolutions adopted in the said meeting; and (c) the statement of each member of the Monetary Policy Committee on the resolutions adopted in the said meeting. [Section 45ZL and Subsection 11 of Section 45ZI] Monetary Policy Report: The Reserve Bank is required to publish, once in every six-months, a document titled Monetary Policy Report (MPR) explaining the sources of inflation and the forecasts of inflation for the period between six to eighteen months from the date of publication of the document. The MPR shall contain (a) The explanation of inflation dynamics in the last six months and the near term inflation outlook; (b) Projections of inflation and growth and the balance of risks; (c) An assessment of the state of the economy, covering the real economy, financial markets and stability, fiscal situation, and the external sector, which may entail a bearing on monetary policy decisions; (d) An updated review of the operating procedure of monetary policy; and (e) An assessment of projection performance. The MPR is released on the Bank website within 24 hours of the release of the relevant policy statement. [Section 45ZM and Regulation 6(ii)] Silent Period: The external communication policy for the MPC mandates a silent or blackout period for the MPC members, starting seven days before the voting/decision day, and ending seven days after the day policy is announced. During this period, the MPC members are required to avoid public comment on issues related to monetary policy, other than through the MPC’s communication framework. [Regulation 5(i)] Accountability of the MPC The RBI Act enable the Central Government to set out the definition of failure to meet inflation target as well as accountability measures in case of failure. As per the RBI Act, when the Bank fails to meet the inflation target, it is required to set out in a report to the Central Government – (a) the reasons for failure to achieve the inflation target; (b) remedial actions proposed to be taken by the Bank; and (c) an estimate of the time-period within which the inflation target shall be achieved pursuant to timely implementation of proposed remedial actions. In the event of failure of the Reserve Bank to meet the inflation target, a separate meeting is required to be scheduled by the Secretary to the Committee, as part of the normal policy process to discuss and draft the report to be sent to the Central Government under the provisions of the Act. The Report is required to be sent to the Central Government within one month from the date on which the Bank failed to meet the inflation target. [Sub-sections (a), (b) and (c) of Section 45ZN and Regulation 7] Code of conduct of the MPC Members: The Regulation provides broad guidance to members of the MPC on their ethical conduct to help enhance public trust and confidence in the Bank and its policies. The Members, inter alia, are expected to be guided by the objectives of monetary policy set out in the Act and the inflation target set by the Central Government, and independently and candidly express their views in the MPC meetings before voting. The RBI Act places responsibility for removing the MPC members. The current MPC Framework provides guidance to the members of MPC on their ethical conduct to build trust and confidence in the bank policies. Members are also expected to take adequate precautions to ensure utmost confidentiality of the MPC’s policy decision before it is made public, preserve confidentiality about the decision-making process and maintain the highest standards of probity consistent with public office. While interacting with profit-making organizations or making personal financial decisions, they shall weigh carefully, any scope for conflict between personal interest and public interest [Section 45 ZE and Regulation 5(ii)] Annex III.4: Model MPC Communication Document Section 45ZB of the RBI Act, 1934 provides for an empowered six-member monetary policy committee (MPC) to be constituted by the Central Government by notification in the Official Gazette. The MPC is guided by the objectives of monetary policy set out in the Act and the inflation target set by the Central Government. Apart from rigorous analysis and intense deliberations that precede every monetary policy decision, the success in arriving at the desired outcome of monetary policy also depends on the effectiveness of communication. Communication is an important tool in the conduct of monetary policy. Accordingly, this document lays out communication guidance for the MPC members. Guidance on Written communication The MPC resolution is published on the final day of the policy meeting. It conveys the MPC’s collective assessment of macroeconomic developments; the MPC’s projections of growth and inflation for a year ahead along with balance of risks; and votes of each member ascribed to such members. The minutes of the MPC that are released on the fourteenth day after the resolution is published, include in addition to the resolution, the statement of each member of the MPC on the resolution adopted in the meeting. The MPC members shall independently and candidly express their views in the meetings before voting. Members shall take adequate precaution to ensure utmost confidentiality of the MPC’s policy decision before it is made public and preserve confidentiality about the decision-making process. Guidance on Speeches and other Communication Since monetary policy communication is market sensitive, to ensure that the rationale behind monetary policy actions is understood correctly, the Governor, Chairperson of the MPC, will give a press statement after conclusion of every meeting. He will also address the media and researchers and analysts to address their queries and to clarify the stance and intent of policy so that misconceptions and confusion are eschewed, and a common set of expectations is shared by all. This can greatly enhance the efficiency and credibility of monetary policy. Other members of the MPC shall ensure that personal views expressed through speeches and other forms of communications are attributable only to themselves. They may also be sensitive of the MPC’s collective decision and act in a manner consistent with the integrity, dignity and reputation of their office and of the Reserve Bank of India while discussing about monetary policy in public forums. The MPC members must also keep the Reserve Bank informed about their public lectures and research publications on matters related to monetary policy. Guidance on Communication during Emergency Meetings Should there be a need of conducting monetary policy meetings outside the regular/scheduled policy meetings, communication of monetary policy decisions in such emergency meetings will be made only by the Governor, as chairperson of the MPC. Silent Period Members shall observe a silent or blackout period relating to monetary policy issues, starting seven days before the voting/decision day, and ending seven days after the monetary policy is announced. During this period, the members must refrain from making public statements on matters relating to monetary policy, other than through the MPC’s communication framework. Members may avoid private interactions with media or other groups to eschew speculation. The silent period after the policy is announced will not be applicable in the case of the Governor, as Chairperson of the MPC. The Governor has to interact with various stakeholders in the monetary policy discussions to help enhance the efficacy of monetary policy. For any public communication during the silent period after the policy is announced, the members of the MPC, other than the Chairperson of the MPC, will consult and inform the MPC Secretary in advance. This Chapter has been prepared by Praggya Das, Asish Thomas George, Aastha, Deepak Kumar, Dirghau K. Raut and Priyanka Bajaj. Authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Rajiv Ranjan for his encouragement and Shri Muneesh Kapur for his valuable suggestions and comments on earlier drafts. Authors express their gratitude to Shri C.V. Joshi for his comments on statutory aspects and Dr. Jugnu Ansari and Shri Kashyap Gupta for their technical inputs. 1 Chapter I lists the countries that are formally recognised as practicing inflation targeting under their monetary policy framework. 2 The Central Government appoints external members (under clause (d) of section 45ZB (2) of the RBI Act) based on the recommendations made by a search-cum-selection committee “from amongst persons of ability, integrity and standing, having knowledge and experience in the field of economics or banking or finance or monetary policy”. These members are required to be less than 70 years of age at the time of appointment. The external members hold office for a period of four years and are not eligible for re-appointment. 3 As per Section 45ZI of the amended RBI Act, the RBI shall organise at least four meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee in a year presided by the Governor, and in his absence by the Deputy Governor who is a member of the Monetary Policy Committee. Clause 3(b) of Section 45ZI of the RBI Act and Regulation 5(i)(b) of the RBI MPC and Monetary Policy Process Regulations, 2016, have provisions to reschedule a meeting or arrange an emergency meeting at 24 hours’ notice. With technology enabled arrangements in place, meetings may be convened at even shorter notice period. 4 The quarterly enterprise surveys are at times launched even earlier, keeping policy synchronisation under consideration. 5 Since data releases often take place with a lag, the current quarter and sometimes even the previous quarter actual numbers are not available to the policy makers at the time of decision making. Hence, they have to rely on ‘nowcasts’ – the estimates of current quarter based on a set of coincident indicators. 6 Inter-Departmental Group (IDG) comprises of three central office departments of RBI, viz., Department of Economic and Policy Research (DEPR), Department of Statistics and Information Management (DSIM) and Monetary Policy Department (MPD). 7 As indicated in Chapter I, the universe is restricted to twenty-two meetings of the first MPC. 8 Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra served in two capacities on the MPC (i) as ‘an officer nominated by the Central Board’ under Section 45ZB(2) (c) of the RBI Act from October 2016 to December 2019, and (ii) as ‘Deputy Governor in charge of monetary policy’ under Section 45ZB(2) (b) thereafter. 9 This involves removing spaces, punctuation marks and other special notations, numbers, and uninformative words from the pooled document of the MPC statements. 10 These measures are widely used in the literature to estimate accuracy (Öller and Barot, 2000; Pons, 2000; Reid, 2016). 11 For variations of the same technique, see Holden and Peel (1990), Barrionuevo (1993), and Fildes & Stekler (2002). 12 The root mean square deviation of 1-month and 3-month OIS from repo rate declined to 0.13 and 0.16 percentage points respectively after inflation targeting was formally adopted, from 0.46 and 0.34 percentage points before the FIT regime, respectively. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ಪೇಜ್ ಕೊನೆಯದಾಗಿ ಅಪ್ಡೇಟ್ ಆದ ದಿನಾಂಕ: