IST,

IST,

Draft Report of the Internal Working Group on Implementation of Counter-cyclical Capital Buffer

0.1 Businesses are prone to the impact of boom-bust economic cycles. Banking business is no exception to this; rather banks are more prone to economic cycles as they have exposure to many business entities at any given time and the combined effect of the performance of all these entities is to be borne by the banks in all phases of the economic cycles. This dimension of pro-cyclicality, is what makes banking different from other businesses. It accentuates the ill-impacts of economic cycles in a feedback loop, i.e., the cycle becomes self-fulfilling, increasing in size and causing externalities to the economy and society. 0.2 In boom times, there is more demand for credit and banks tend to become aggressive, which could lead to relaxation in credit standards and in excessive credit growth. Debtors tend to do well and service the loans in time. They also improve their financials as also their credit ratings. Banks’ loan losses and capital requirements fall below their long-run average and the need for loan loss provisions are less. Banks make good profits as the loan loss provisions are low. Despite higher credit growth, banks typically do not need commensurately higher capital as their borrowers are likely to have good credit ratings and as per Basel capital requirements, high rated borrowers require less capital. A higher amount of profits is thus distributed as dividends. 0.3 When the economic cycle turns, borrowers’ credit quality tends to worsen, leading to a higher probability of default in servicing interest and principal re-payment. Some of these loans become non-performing assets (NPAs). Banks’ profits start dipping or they may even start making losses, resulting in write-off of capital. At the same time, they are required to make higher loan loss provisions for the non-performing loans and maintain higher capital for the rating down-gradation of their borrowers. With their poor financials, banks do not get external capital to support their existing loan portfolio, and further growth in credit. This results in banks becoming cautious and restricting lending, thereby resulting in the credit contraction risk spilling over to the real sector of the economy which at that time needs credit the most. It may lead to systemic risk which may spiral into economic crisis. 0.4 The financial crisis which originated in 2007 was unlike some of the past crises in that it did not occur due to a crash in the stock market. It originated in the banking and the shadow banking sectors in the form of excessive credit growth. When the credit bubble burst, banks were saddled with huge losses and capital write-offs. Further, banks were also finding it difficult to raise additional capital from the market. These losses destabilised the banking sector and sparked a vicious circle, whereby problems in the financial system contributed to restricting lending to the real sector that then fed back on the banking sector. Such interactions of the banking sector with the real economy highlighted the importance of effects of pro-cyclicality of capital and provisioning requirements in banking sector. 0.5 The issue of pro-cyclicality of bank capital regulation, as shown in various studies1, dates back to Basel II or to some extent to Basel I days. Repullo and Saurina (2011) have underscored the impact of Basel II capital requirements on pro-cyclicality by showing that the bank capital regulation may amplify business cycle fluctuations2. This effect may be more pronounced during downturns, when banks find it difficult to raise additional capital, which results in restricted lending. 0.6 The issue of pro-cyclicality was discussed in the meeting of the G-20 in November 2008 and it was agreed to address pro-cyclicality in financial market regulations and supervisory systems. Five principles were set for reform of financial markets, one being on “enhancing sound regulation”. The G-20 instructed the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Financial Stability Forum (FSF), later renamed the Financial Stability Board (FSB), and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) to develop recommendations to mitigate pro-cyclicality, including the review of how valuation and leverage, bank capital, excessive compensation, and provisioning practices may exacerbate cyclical trends. This brought into focus creation of macro-prudential tools to deal with pro-cyclicality and create countercyclical provisioning3 and capital buffers to obviate systemic risk. 0.7 Looking at the need for development of macro-prudential tools to address pro-cyclicality, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS), the oversight body of the BCBS (or Basel Committee), envisaged introduction of a framework for countercyclical capital measures. Their press release dated September 7, 2009 included a commitment to introduce a framework for Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCCB) over and above the minimum capital requirement. The December 2009 Consultative Document, “Strengthening the resilience of the banking sector”, set out the following four objectives to address the issue of pro-cyclicality:

Thereafter, the Basel Committee issued a consultative Document on Countercyclical Capital Buffer in July 2010 for comments and issued Guidance for national authorities operating countercyclical capital buffer as part of the Basel III package in December 2010. 0.8 The CCCB is a critical component of the Basel III framework. Though presently not many countries have issued the guidelines on implementation of the buffer in their respective jurisdictions, most countries are expected to adopt it in the coming years. The primary aim of the CCCB regime is to build up a buffer of capital which can be used to achieve the broader macro-prudential goal of restricting the banking sector from indiscriminate lending in the periods of excess credit growth that have often been associated with the building up of system-wide risk. 0.9 The CCCB regime endeavours to ensure that not only the individual banks remain solvent through a period of stress, but also that the banking sector has capital in hand to help maintain the flow of credit in the economy during economic downturns and periods of stress. Further, as capital is a more expensive form of funding, the stipulation regarding build-up of capital defences may have the additional benefit of moderating excessive credit growth when economic and financial conditions are buoyant. At the same time, during the period of excessive credit growth, the buffer may act as a moderator from the debtors’ perspective as it is likely to raise the cost of credit, and therefore, dampen its demand, and may help to lean against the build-up phase of the cycle in the first place. 0.10 Against this backdrop, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) set up an Internal Working Group (IWG) under the Chairmanship of Shri B Mahapatra, Executive Director, RBI, to create a CCCB framework for banks in India. The Approach of the IWG 0.11 The Basel Committee, based on empirical evidence, has observed that excessive credit growth builds up system-wide risk and prescribed credit-to-GDP ratio as the starting reference point for implementation of CCCB. Credit-to-GDP ratio tends to rise during the period of economic boom and fall during the period of economic downturn. The difference of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its long-term trend, viz., credit-to-GDP gap (actual credit-to-GDP ratio less long term credit-to-GDP trend) indicates the build-up of excessive credit growth in an economy and system-wide risk as a precursor to the crisis. The CCCB should, therefore, be build up when the credit-to-GDP gap exceeds a defined threshold. 0.12 The CCCB, by being based on credit, has significant advantage over many of the other variables of appealing directly to the objective of the CCCB, which is to achieve the broader macro-prudential goal of protecting the banking sector during periods of excess credit growth. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that the Basel Committee recognizes that the credit-to-GDP gap may not always work in all jurisdictions at all times, and that the authorities may enunciate a set of principles for the buffer decision in a transparent way. Judgment coupled with proper communications is thus an integral part of the CCCB regime. Further, the CCCB guide should also be internationally consistent. 0.13 The IWG noted the guidance of the Basel Committee, and in its analysis, has endeavoured to enunciate principles that would work in conjunction with judgement so as to establish a sound framework for CCCB in India, as also to facilitate further decision-making in the setting of CCCB. 0.14 Keeping in view the ‘comply or explain’ framework of the Basel Committee, the IWG started with calculating the credit-to-GDP gap as prescribed by the Basel Committee for CCCB framework for India. The IWG was aware of the drawbacks of depending solely on credit-to-GDP gap for CCCB framework. In a structurally transforming economy with rapid upward mobility, growth in credit demand will expand faster than GDP growth for several reasons:

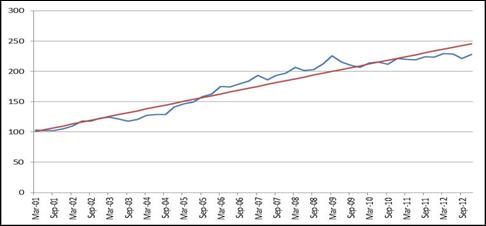

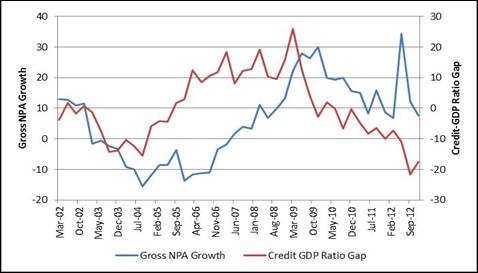

0.15 Hence, the resulting inferences from credit-to-GDP gap may be misleading as it will be difficult to identify what and how much is due to structural transformation and how much is due to excessive credit growth. However, as the structural transformation gets entrenched and is reflected in the evolving trend, the deviation from this new trend could still indicate the “unsustainable” part of the credit demand, which may be “excessive” and may require dampening. Triggering the CCCB too early out of excessive caution may involve sacrifice of growth. On the other hand, complacency and failure to trigger buffer decision may lead to build up of pressure. 0.16 Given this context, the IWG felt that instead of mechanically following the credit-to-GDP ratio and credit-to-GDP gap, the Basel framework may be tested in Indian conditions, and if required, suitable modifications be made to the framework. The IWG tried to dovetail the CCCB framework prescribed by the Basel Committee to Indian conditions, albeit with a caveat that the CCCB calibration is such that the credit growth required for an emerging market economy like India does not get choked. 0.17 The empirical exercise to identify the suitability of credit-to-GDP ratio required a sufficiently long time series data on both credit and GDP. This posed a challenge as data to carry out a comprehensive evaluation and backtesting was not readily available. Though a large number of components of aggregate credit are presently being captured by regulators/entities, a long term time series at quarterly frequency of the same is not available with them. 0.18 While determining the sources of credit, it was not possible to define credit in an all-encompassing way as long term time series of quarterly data on variables such as (i) loans by housing finance companies (HFCs), (ii) loans by Non-banking finance companies (NBFCs), (iii) issue of commercial paper, and (iv) issue of bonds by corporate sector, were not available at quarterly frequency from their respective sources. Therefore, the availability of reliable time series data for sufficient length of time became the criteria to decide whether a particular component of credit would be included in the definition of credit for the purpose of analyzing the suitability of credit-to-GDP ratio. For the purpose of present exercise, the IWG decided to use data on bank credit comprising credit by scheduled commercial banks (including regional rural banks) as such a time series of data was available for a long period, as far as mid-1990s. 0.19 In India, availability of GDP data at quarterly frequency is relatively recent, with official data available from 1996-97. However, similar time series was not available for some of the other variables used by the IWG in its analysis, such as Gross NPA (GNPA) growth, etc. Keeping in view the availability of quarterly time series data on major components of credit and GDP, as also, corresponding data for other variables, the IWG decided to use time series data for all the indicators to be used in the present exercise from March 2001. 0.20 Further, the GDP data also show substantial seasonal variation, which needed to be taken into account before computing the credit-to-GDP ratio. Therefore, the standard method of de-seasonalising the GDP data was used, and the resultant seasonally adjusted GDP was used for computation of credit-to-GDP ratio. 0.21 Calculation of credit-to-GDP gap requires estimation of long term trend of credit-to-GDP ratio. For this purpose, the Basel Committee has prescribed use of one sided Hodrick Prescott filter. Though, the IWG considered use of one-sided Hodrick-Prescott filter as suggested by the BCBS guidance paper, due to limitations of data availability, particularly the quarterly GDP (before 1996-97) and other related variables (before 2001-02), using one-sided filter was not feasible. The IWG recognized this as a limitation and decided to proceed with use of two-sided Hodrick-Prescott filter for the purpose of analysis. Issues and Recommendations The recommendations of the IWG preceded by briefs on the relevant issues are given below: Authority to operate the CCCB 0.22 The IWG noted that the authority to operate CCCB would require relevant and current supervisory and macroeconomic information. The CCCB decision may have implications for the conduct of monetary policy on one hand and supervision function on the other. The IWG felt that RBI would be better placed in conducting a detailed assessment of prevailing supervisory and macroeconomic information, as in India these functions and information is vested with itself. Recommendation 1 RBI shall be the authority to operate and communicate the CCCB decision. (Paragraph 3.10) Credit-to-GDP Gap Estimation 0.23 The analysis was carried out using credit-to-GDP gap to estimate the level where the CCCB may be triggered, i.e., the lower threshold (L). However, the IWG observed that using long term credit-to-GDP gap on its own, could not help in identification of the lower threshold of CCCB. The IWG felt that the likely reasons for inadequacy of credit-to-GDP gap as a sole factor may be because of India specific circumstances such as, the stage of economic development, the degree of maturity of financial markets, the institutional framework, the process of structural transformation underway, etc. Hence, the IWG deviated from the methodology prescribed by the Basel Committee considered it necessary to use data on growth in GNPA, along with the credit-to-GDP data to arrive at the thresholds. Recommendation 2 While the credit-to-GDP gap may be used for empirical analysis to facilitate CCCB decision, it may not be the only reference point in the CCCB framework for banks in India and the credit-to-GDP gap may be used in conjunction with other indicators like GNPA growth for CCCB decisions in India. (Paragraph 3.26) Pre-announcement of the CCCB 0.24 The IWG observed pro-cyclicality in the time series data on credit-to-GDP gap and the annual growth on GNPA of the banking industry in India. The relationship between credit-to-GDP gap and annual growth in GNPA was obtained, and it was observed that the credit-to-GDP gap leads GNPA growth, statistically significantly, by sufficient period with a peak statistical significant period of 9 quarters. Hence, given the lag identified by the analysis, the IWG felt that the CCCB should be triggered well before the expected increase in GNPA. Further, in line with the Basel Committee prescription, the CCCB decision may be pre-announced with a lead time of up to 12 months (4 quarters). Recommendation 3 The CCCB decision may be pre-announced with a lead time of 4 quarters. (Paragraph 3.33) Setting the Lower Threshold of the CCCB 0.25 The Basel Committee has prescribed the lower threshold (L) value for CCCB at 2 percentage points of the credit-to-GDP gap. To estimate the CCCB trigger threshold, the IWG used the method proposed by Sarel (1996). In the analysis, it was observed that when the credit-to-GDP gap reaches 3 percentage points, its relationship with GNPA became highly significant. Hence the CCCB trigger (lower threshold, L) for the Indian banking system may be when the credit-to-GDP gap reaches 3 percentage points provided the relationship with GNPA remains significant. Recommendation 4 The lower threshold (L) of the CCCB when the buffer is activated may be set at 3 percentage points of the credit-to-GDP gap, provided its relationship with GNPA remains significant. (Paragraph 3.35) Fixing of the Upper Threshold of the CCCB 0.26 The Basel Committee has prescribed higher threshold (H) value for CCCB at 10 percentage points of the credit-to-GDP gap. However, India being an emerging market economy, growth related concerns would warrant credit expansion that could not be compared with other countries, especially developed countries. Hence, in Indian context, the upper threshold of 10 percentage points of credit-to-GDP gap as prescribed by the Basel Committee was not found to be suitable by the IWG, as it felt that it may constrain the credit growth. 0.27 Looking at empirical evidence in the past decade, it was observed that the credit-to-GDP gap had exceeded 20 percentage points only in one quarter and even came close to that level only during two earlier quarters. Further it was observed that credit-to-GDP gap has immediately fallen sharply after each peak, due to combination of several factors, including the policy response. Average credit-to-GDP gap during a run of positive values from September 2005 to September 2009 works out to 11.56 percentage points. The credit GDP gap exceeded 15 percentage points only on four occasions. 0.28 The Basel Committee has observed that H should be low enough, so that the buffer would be at its maximum prior to major banking crises. Considering these factors, the IWG felt that a threshold value of 15 percentage points may be identified to deploy the maximum value of CCCB, in view of the rarity with which this threshold has been breached in the recent history. Recommendation 5 The upper threshold (H) of the CCCB may be kept at 15 percentage points of credit-to-GDP gap. (Paragraph 3.37) Calibration of CCCB 0.29 The IWG noted that the CCCB shall be activated when credit-to-GDP gap exceeds the lower threshold (3 percentage points) and shall be 2.5 per cent of risk weighted assets when it touches the upper threshold (15 percentage points). For any other value of the credit-to-GDP gap between 3 and 15 percentage points, the CCCB will vary linearly from 0 to 2.5 per cent of risk-weighted assets. Recommendation 6 The CCCB shall increase linearly from 0 to 2.5 per cent of the risk weighted assets (RWA) of the bank based on the position of credit-to-GDP gap between 3 percentage points and 15 percentage points. However, if the credit-to-GDP gap exceeds 15 percentage points, the buffer shall remain at 2.5 per cent of the RWA. If the credit-to-GDP gap is below 3 percentage points then there will not be any CCCB requirement. (Paragraph 3.38) Use of Supplementary Indicators 0.30 Basel Committee, in its guidance, has also recommended use of supplementary indicators in the CCCB decision making process such as various asset prices, funding spreads and CDS spreads, credit condition surveys, real GDP growth and data on the ability of non-financial entities to meet their debt obligations on a timely basis. 0.31 Looking at the limitations of the credit-to-GDP gap indicator in India, the IWG also considered other variables, including those suggested by the Basel Committee and their variants in the Indian context as possible supplementary indicators that may help in the CCCB decision. These included indicators that are relevant to our banking system, and others like housing prices, equity prices, funding spreads, credit condition surveys, real GDP growth, data on the ability of non-financial entities to meet their debt obligations on a timely basis, credit-deposit ratio, credit condition surveys, industrial outlook survey, aggregate real credit growth, banking sector profits and non-performing assets. The IWG was of the view that the demands of Indian economy and the dynamics in our domestic financial markets are different from that of other countries. Hence, instead of depending solely on one indicator, the decision on CCCB should be taken considering the dynamics of various supplementary indicators. Further, the analysis should also include the correlations that these supplementary indicators have with the GNPA growth. Some of the supplementary indicators found relevant by the IWG are as under: 0.31.1 Credit deposit (C-D) ratio has been an integral part of micro-prudential monitoring in India. While the absolute C-D ratio is a function of several factors, including the statutory requirements, such as CRR and SLR, incremental C-D ratio provides an insight into the possible over-heating of the credit market and use of alternate sources of funding by banks. Incremental C-D ratio for moving period (one year to three years) was analysed, and it was observed that three-year moving incremental C-D ratio was bearing high positive correlation with credit-to-GDP gap. Similarly, incremental C-D ratio for moving period of three-years exhibited high negative contemporaneous correlation with the GNPA growth. However, at a higher lag, the correlation became positive. Recommendation 7 The incremental C-D ratio for a moving period of three-years and its correlation with credit-to-GDP gap as also, with GNPA growth, may be used as a supplementary indicator for the CCCB decision. (Paragraph 4.15) 0.31.2 Industrial Outlook (IO) Survey, an opinion based forward looking survey covering selected public and private limited companies in the manufacturing sector, is being conducted on a quarterly basis by the Reserve Bank of India. Empirical evaluation of the assessment index computed from the IO Survey indicated that the index exhibited a strong negative correlation with the GNPA growth, implying higher GNPA growth if the index is low and vice versa. However, the relation between this index and credit-to-GDP gap could not provide any conclusive results to the IWG. Recommendation 8 Looking at the utility of the IO assessment index as an indicator of incipient NPA growth, it may be used along with GNPA growth as a supplementary indicator in CCCB decision. (Paragraph 4.20) 0.31.3 The IWG observed that the Reserve Bank of India has been tracking the financial performance of corporate sector. Consistent time series of the ratios and rates for a sample of about 2,000 companies are available since the financial year 2000-01. The IWG felt that of the various financial indicators, the interest coverage ratio may be of particular importance to assess the stress faced by the corporate sector. 0.31.4 On examining the relationship of the interest coverage ratio to GNPA growth, it was found that there is no contemporaneous correlation between these indicators. However, when the correlation between interest coverage ratio and credit-to-GDP gap is examined, it is seen that in the periods of high credit-to-GDP gap, the companies have comfortable interest coverage, thereby indicating healthy financial position. Looking at the high correlation of interest coverage ratio with credit-to-GDP gap, the IWG recommends its inclusion as one of the supplementary indicators to supplement the CCCB decision. Recommendation 9 The interest coverage ratio with credit-to-GDP gap may be used as a supplementary indicator for CCCB decision. (Paragraph 4.26) 0.31.5 In India, the housing price index is a relatively new concept. Presently, the Reserve Bank of India is compiling a quarterly House Price Index (HPI) for some of the bigger cities. National Housing Bank (NHB) is also compiling an index, viz., RESIDEX that comprises only residential housing sector. It is envisaged that the index may later be expanded to include commercial property and land also. As there were not many data points available in the index, and also, as these indices being in formative stage, these were not considered as supplementary indicators for the current exercise. 0.31.6 Further, the RBI has also been analyzing credit conditions in specific sectors of the economy through a quarterly Credit Condition Survey (CCS) since January-March 2010. In a scenario, when it is relatively easy to monitor the credit supply by banks, but no direct quantitative data is available on credit demand, this type of survey becomes useful. This is a forward-looking survey and seeks information on various aspects of credit, including developments in credit sector and causes thereof. However, as this survey is relatively recent with only two years’ quarterly data, it may not be possible to use the results of CCS immediately. The IWG felt that the data from CCS may be a very useful input for CCCB exercise and going forward, this index may also form a part of supplementary indicators for CCCB decision. Recommendation 10 In due course, indices like House Price Index / RESIDEX and Credit Condition Survey may also form a part of the supplementary indicators for CCCB decision. (Paragraph 4.6 & 4.28) .0.32 In the analysis, it was observed that supplementary indicators such as incremental C-D ratio and IO Survey Assessment index have a significant relationship with the GNPA growth. Further, the lag at which the relationship gets significant is more than 4 quarters (i.e. 12 months). This coincides with the IWG’s recommendation (Recommendation 3) on the period for pre-announcement of imposition of the CCCB. 0.33 The analysis of all the indicators on an ongoing basis will provide sufficient information inputs to the Reserve Bank of India to decide whether it is necessary to activate the CCCB. As the empirical evidence on the basis of any single indicator may not be conclusive, the IWG recommends that decision making in respect of CCCB may be similar to the multiple indicator approach, followed in policy making. In any case, the Basel Committee has provided ample freedom to the national authorities to “...apply judgment in the setting of the buffer in their jurisdiction after using the best information available to gauge the build-up of system-wide risk”. Recommendation 11 The Reserve Bank of India may apply discretion in terms of use of indicators while activating or adjusting the buffer. (Paragraph 4.34) Use of Sectoral Approach 0.34 Due to lack of availability of a long time series of a credible real estate index, the IWG could not use this critical indicator in the present exercise for CCCB implementation, but could only recommend it as a forward looking indicator. The IWG observed that looking at the level of development of market infrastructure in our country, as also, due to lack of availability of long time series of data, there may be some sectors (like real estate sector) that may be critical due to their bearing on financial stability, but may not be a part of CCCB decision. Credit growth to certain sensitive sectors may lead to formation of asset bubbles and also significantly outpace the overall credit growth. Excessive credit growth in specific sectors may have significant financial stability risks. 0.35 The RBI has been applying countercyclical capital and provisioning requirements based on the analysis of sectoral credit growth. In the build-up phase, the tightening of prudential requirements made credit to targeted sectors costlier thereby moderating the flow of credit to these sectors. There is evidence that moderation in credit flow to these sectors was also in part due to banks becoming cautious in lending to these sectors on the signalling effect of RBI’s perception of build up of sectoral risks. This way the exposure of banks’ to these sectors was reduced. Looking at such sector specific peculiarities in our country and their subsequent impact on implementation of macro-prudential policies, the IWG recommends that the CCCB framework in India may have to work in conjunction with sectoral approaches. Recommendation 12 The CCCB framework in India may be operated in conjunction with sectoral approach that has been successfully used in India over the period of time. (Paragraph 4.30) Release of CCCB 0.36 The Basel Committee had recommended that CCCB release may be required due to banking system related losses or due to systemic issues. To prevent the crisis from taking a large proportion, the release of buffer should be immediate. Basel Committee has suggested a few indicators to guide the authorities during the release phase of CCCB. However, these indicators do not provide conclusive evidence of their utility during such time. Hence, due to inherent uncertainty and the lack of experience associated with operating of CCCB, the IWG observed that the variables to be used to guide the release phase should be selected in such a way that they react sufficiently promptly. For the release phase, the same set of indicators that were used during the activating phase of the CCCB may be used. However, owing to inherent uncertainty and the lack of experience associated with operating of CCCB, the IWG felt that instead of hard rules-based approach, flexibility in terms of use of judgement and discretion may be required for operating the release phase of CCCB. 0.37 The IWG also agreed that gradual release of CCCB or even release in discrete time/amount of CCCB would not serve the basic purpose of CCCB. The IWG felt that in case of crisis in banking sector or any other sector indirectly impacting the banking sector, it is prudent to stem the crisis early, and hence, the entire CCCB may be released at a single point in time. Recommendation 13 The same set of indicators that are used for activating CCCB may be used to arrive at the decision for the release phase of the CCCB. However, instead of hard rules-based approach, flexibility in terms of use of judgement and discretion may be provided to the Reserve Bank of India for operating the release phase of CCCB. Further, the entire CCCB may be released promptly at a single point in time. (Paragraph 5.5 & 5.7) Treatment of surplus created after release of CCCB 0.38 When the CCCB returns to zero, the capital that is released is for the purpose of absorbing losses or for protecting banks against the impact of problems elsewhere in the financial system. In such a case, the Basel Committee had recommended that the capital surplus created should be unfettered and that there should be no restrictions on banks on distribution of this capital. However, the Basel Committee has left the final decision on treatment of this surplus with national authorities. 0.39 The IWG felt that unfettered access to capital by banks may not be prudent as the RBI may be required to prohibit certain use of the released buffer by banks if it feels that such an action is necessary given the prevailing circumstances. Recommendation 14 The capital surplus created when the countercyclical buffer is returned to zero should not be unfettered. The Reserve Bank of India would provide necessary guidance to the banks as regards treatment of the surplus at times when the CCCB returns to zero. (Paragraph 6.1) Jurisdictional Reciprocity 0.40 To ensure a level playing field among the domestic and foreign banks, the Basel Committee has recommended jurisdictional reciprocity. The IWG observed that in view of importance of CCCB implementation in India, global best practice as suggested by the Basel Committee may be implemented. Further, Reserve Bank of India has always ensured a level playing field for all the banks having presence in India. Banks in India (both domestic and foreign incorporated) will have to ensure that the CCCB requirement is calculated based on their exposures in India. Recommendation 15 (i) All banks operating in India (either foreign incorporated or domestic banks) should maintain capital under CCCB framework based on exposures in India. (ii) The RBI will convey the CCCB requirement to the home supervisor of the foreign incorporated banks so that they may ensure that their banks maintain adequate capital under CCCB as prescribed by the Reserve Bank of India. (iii) Banks incorporated in India having international presence have to maintain adequate capital under CCCB as prescribed and communicated by the host supervisors to the Reserve Bank of India. (vi) The RBI may also ask Indian banks to keep excess capital under CCCB framework in any of the host countries they are operating if it feels the CCCB requirement in host country is not adequate. In case the CCCB requirement in other jurisdiction is nil / insufficient, the Reserve Bank of India may require that the banks maintain higher buffers. (Paragraph 6.3) Communication of the CCCB Decision 0.41 The Basel Committee has noted that the buffer in each jurisdiction is likely to be used infrequently, and hence, instead of making quarterly statements on CCCB decision on an on-going basis, the authorities may comment on an annual basis. In India, CCCB decisions may form a part of the annual monetary policy statement of the Reserve Bank of India. However, more frequent communications can be conducted by the Reserve Bank of India, if there are sudden and significant changes in economic condition which may have an impact on CCCB decision. At the time of communicating CCCB decision, the Reserve Bank of India may disclose, at its discretion, the mechanics of the CCCB approach, the information that was used to arrive at the decision, etc. Recommendation 16 The CCCB decisions may form a part of the annual monetary policy statement of the Reserve Bank of India. However, more frequent communications can be made by the Reserve Bank of India, if there are sudden and significant changes in economic condition that may have an impact on CCCB decision. Further, at the time of communicating CCCB decision, the Reserve Bank of India may disclose, at its discretion, the mechanics of the CCCB approach, the information that was used to arrive at the decision, the time line of the CCCB activation, etc. (Paragraph 6.4 & 6.5) Interaction of CCCB with Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 0.42 The CCCB incorporates elements of both Pillar 1 and Pillar 2. It may not be desirable that the capital is held twice both under Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 requirements. Hence, prescription under Pillar 2 should not stipulate capital requirement to capture system-wide issues, if the bank is already maintain capital under CCCB framework. Further, the IWG also felt that the capital meeting the CCCB should not be permitted to be simultaneously used to meet non-system-wide elements (e.g. concentration risk) under Pillar 2 requirement. Recommendation 17 (i) A bank maintaining CCCB may not hold capital under Pillar 2 requirement for financial system-wide issues. (ii) The capital meeting the countercyclical buffer should not be permitted to be simultaneously used to meet non-system-wide elements of Pillar 2 requirement. (Paragraph 6.6) Location of the CCCB 0.43 The IWG noted that as in the case with the minimum capital requirement, host authorities would have the right to demand that the CCCB be held at the individual legal entity level or consolidated level within their jurisdiction. The IWG recommends that for all banks operating in India, CCCB shall be maintained in India. Recommendation 18 For all banks operating in India, CCCB shall be maintained on solo basis as well as on consolidated basis in India, where appropriate. (Paragraph 6.7) Periodic review 0.44 The IWG recognizes that CCCB is a new concept and is untested. Further, it is also likely that it may not be imposed frequently. The indicators and thresholds used by the IWG may either show more robust results in due course of time or may even breakdown. Moreover, there is possibility of emergence of new indicators. Therefore, continuous research and empirical testing may be required and the indicators suggested in recommendation 9 such as House Price Index, RESIDEX, Credit Condition Survey, etc., should be further explored. Recommendation 19 The indicators and thresholds used for CCCB decisions may be subject to continuous research and empirical testing for their usefulness and new indicators may be explored to support CCCB decisions. (Paragraph 6.8) Introduction 1.1 The recent global financial crisis has underscored the importance of capital in build-up of defence against the vicissitudes of financial system and the economic cycles. This aspect attains prime importance as during the crisis, it was observed that arranging of capital became extremely expensive and difficult. It brought forth the fact that shoring up of capital during the period of excess credit growth serves a dual advantage – on one hand, it helps moderate excessive credit growth when economic and financial conditions are buoyant, and on the other, it provides comfort in terms of additional capital that may be available at times of crises. 1.2 Business entities are generally exposed to economic cycles. In boom times, when there is an economic upswing, demand for their products and services grows exponentially. They do well in their businesses, increase borrowing, create more capacity and make high profits as a result of increased leverage. However, when economic conditions deteriorate, demand for goods and services falls. Business shrinks and entities that are unable to service their loans and liabilities default in meeting their obligations. 1.3 Banking business is no exception to this; rather banks are more prone to economic cycles. Pro-cyclicality, in banking business accentuates the ill-impacts of economic cycles in a feedback loop, i.e., the cycle becomes self-fulfilling, increasing in size and causing externalities to the economy and society. 1.4 In boom times, there is more demand for credit and banks become aggressive, thereby relaxing the credit standards and indulging in excessive credit growth. Debtors do well and service the loans in time. Debtors also improve their financials as also their credit ratings. Banks loan loss ratios are below their long-run average and need for loan loss provisions is less. Banks make good profits as the loan loss provisions are low. Banks also do not need more capital as their borrowers have good credit ratings and as per Basel Capital requirements, high rated borrowers require less capital. 1.5 When the economic cycle turns, borrowers’ credit quality tends to worsen, leading to a higher probability of default in servicing interest and principal payment. Some of these loans become non-performing assets (NPAs). Banks’ profits start dipping or they may even start making losses thereby resulting in write-off of capital. At the same time, they are required to make higher loan loss provisions for the non-performing loans and maintain higher capital for the rating down-gradation of their borrowers. With their poor financials, banks do not get external capital to support their loan portfolio. This results in banks becoming cautious and restricting lending, thereby resulting in the risk spilling over to the real sector of the economy which needs credit the most. It may cause further spiralling in systemic risk and may lead to economic crisis. 1.6 The issue of pro-cyclicality of bank capital regulation, as shown in various studies4, dates back to Basel II or to some extent to Basel I days. Repullo and Saurina (2011) have underscored the impact of Basel II capital requirements on pro-cyclicality by showing that the bank capital regulation may amplify business cycle fluctuations5. This effect may be more pronounced during downturns, when banks find it difficult to raise additional capital, thereby restricting their lending. Hence, mitigation of the pro-cyclicality of minimum capital requirements is an issue that is engaging the policy makers. 1.7 The G-20, aware of the problem of pro-cyclicality in the capital regulation framework, in its meeting in November 2008, agreed that it was important to address the issue of pro-cyclicality in financial market regulations and supervisory systems. They set five principles for reform of financial markets, of which one was “enhancing sound regulation”. 1.8 The G-20 asked the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Financial Stability Forum (FSF), later renamed the Financial Stability Board (FSB), and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) to develop recommendations to mitigate pro-cyclicality, including review how valuation and leverage, bank capital, excessive compensation, and provisioning practices may exacerbate cyclical trends. 1.9 Looking at the need for development of tools to address the cyclicality in capital requirement, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS), the overseeing body of the standards set by the Basel Committee, envisaged introduction of a framework on countercyclical capital measures. Their press release dated September 7, 2009 included a commitment to introduce a framework for Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCCB) above the minimum capital requirement. 1.10 In its consultative document for strengthening the resilience of the banking sector6, the BCBS (hereafter referred to as Basel Committee) stressed on the need for “…dampening any excess cyclicality of the minimum capital requirement …” as also, “…to achieve the broader macro-prudential goal of protecting the banking sector from periods of excess credit growth …”. For achieving the latter objective, a Macro Variables Task Force (MVTF) was constituted by the Basel Committee. 1.11 The MVTF placed a fully detailed proposal for review by the Basel Committee at its July 2010 meeting7. Thereafter, in December 2010, the Basel Committee released a guidance document (Guidance for national authorities operating the countercyclical capital buffer, December 2010) providing guidance to national authorities in implementing the countercyclical capital buffer, which in addition, was also likely to help banks understand and anticipate the CCCB decisions in the jurisdictions to which they have credit exposures. 1.12 The Basel Committee, based on empirical evidence, has observed that excessive credit growth builds up system wide risk and prescribed credit-to-GDP ratio as the starting reference point for implementing CCCB. Credit-to-GDP ratio tends to rise in economic boom periods and fall during economic busts. The deviation of the credit to GDP ratio from its long term trend (the credit-to-GDP ratio gap) indicates the build up of excessive credit growth in an economy and system wide risk as a precursor to a crisis. The CCCB should, therefore, be built up when the gap of credit-to-GDP ratio vis-à-vis its long term trend exceeds a certain threshold. 1.13 In this backdrop, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) set up an Internal Working Group (IWG) on countercyclical capital buffer under the Chairmanship of Shri B Mahapatra, Executive Director. The constitution of the Group was as follows:

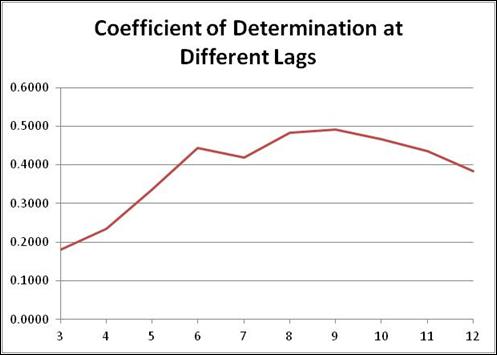

1.14 The broad terms of reference of the IWG are as under: