IST,

IST,

VII Foreign Exchange Reserves (Part 1 of 2)

Introduction

7.1 Policies in respect of management of the exchange rate, foreign exchange reserves and external debt have received increasing emphasis in emerging market economies (EMEs) after the East-Asian crisis and crises elsewhere during the 1990s. The need for a more dynamic and pragmatic approach towards management of exchange rates, reserves and external debt, keeping in view the country specific circumstances, is increasingly being felt by many countries. The scope for exchange rate flexibility has generated considerable debate, particularly in view of the recent build up of reserves in many countries. It is now widely recognised that in judging the adequacy of reserves in emerging economies, it is not enough to relate the size of reserves to the quantum of merchandise imports or the size of the current account deficit. In view of the importance of capital flows, and associated volatility of such flows, it has become imperative to take into account the composition of capital flows, particularly, short-term external liabilities, in judging the adequacy of foreign exchange reserves. An additional factor which is being built into this assessment is the need to take into account contingencies such as unanticipated increases in commodity prices. Furthermore, the need for careful assessment of the external debt situation has assumed an added significance.

7.2 Conventionally, trade flows were deemed to be the key determinants of exchange rate movements. Consequently, the degree of openness to international trade, price and non-price competitiveness and factors which determined market shares abroad were thought to have a crucial bearing on the level and the movement of the exchange rate. In more recent times, the importance of capital flows in determining the exchange rate movements has increased considerably, rendering some of the earlier guide-posts of monetary policy formulation possibly anachronistic (Mohan, 2003). Furthermore, on a day-to-day basis, it is capital flows that influence the exchange rate and interest rate arithmetic of the financial markets. Rather than real factors underlying trade competitiveness, it is expectations and reactions to news that drive capital flows and exchange rates, often out of alignment with fundamentals. Capital flows

have been observed to cause overshooting of exchange rates as market participants act in concert with pricing information. Foreign exchange markets are prone to bandwagon effects. The effects of capital flows on the exchange rate are amplified by the fact that capital flows in ‘gross’ terms can be several times higher than the ‘net’ capital flows (Jalan, 2003b).

7.3 Against this background, the present Chapter focuses on three major areas, viz., foreign exchange reserves, exchange rates and external debt. Section I deals with management of foreign exchange reserves. An attempt is made to assess the costs and benefits of holding reserves alongside adequacy indicators and to benchmark India’s approach to management of reserves against the cross-country experience. Section II on exchange rate management presents a theoretical perspective on exchange rates, followed by a review of the debate relating to choice of exchange rate regime. The section then dwells on various issues relating to exchange rate management practices in India. Interest parity conditions have also been tested in the Indian conditions. Section III on external debt management attempts a cross-country comparison of external indebtedness followed by an analysis of India’s external debt over the years. Concluding observations are set out in the final section.

7.4 The perspectives on the need to build adequate foreign exchange reserves have changed in recent time, especially for an economy with a higher degree of capital account openness. Moreover, the reserve build-up is closely linked to exchange rate management policy. In recent period, accretion to reserves of EMEs also reflects growing macroeconomic imbalances in the US. Reflecting the paradigm shift in external sector and other macroeconomic policies, India’s foreign exchange reserves rose significantly in the last decade. Based on the various reserve adequacy indicators, the level of foreign exchange reserves in India is comfortable. India has also been designated as a creditor country under the Financial Transaction Plan (FTP) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in view of its comfortable level of reserves. Together, these developments have led to a sharp increase in the confidence of domestic and foreign investors in the strength of the Indian economy.

7.5 The recent experience with exchange rates has highlighted the need for developing countries to allow greater flexibility in exchange rates but the authorities should also have the capacity to intervene in foreign exchange markets in view of herding behaviour. The Chapter brings out the increased role of capital flows in exchange rate determination and the pitfalls of higher exchange rate volatility on EMEs. Against this background, India’s exchange rate policy of focusing on managing volatility with no fixed rate target while allowing the underlying demand and supply conditions to determine the exchange rate movements over a period in an orderly way has stood the test of time. Concomitantly, the Reserve Bank has undertaken several measures to deepen and widen the foreign exchange market in India so as to provide the market participants the necessary support to undertake foreign exchange transactions with reduced uncertainty. International research on viable exchange rate strategies in emerging markets has also lent considerable support to the exchange rate policy followed by India.

7.6 Finally, the Chapter documents the perceptible improvement in India’s external debt scenario. This is the outcome of policy reforms that focused, inter alia, on modest current account deficits, a policy preference in favour of equity, tight monitoring of short-term flows, a market determined exchange rate, a transparent policy on external commercial borrowings with prudential restrictions on end-use and a commensurate growth in current receipts.

I. MANAGEMENT OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE

RESERVES

7.7 Of late, the debate over holding large reserves has gained renewed interest with the spectacular growth in accumulation of reserves by the central banks of the EMEs. Under the Bretton Woods system, foreign exchange reserves were used by monetary authorities mainly to maintain the external value of their respective currencies at a fixed level. With the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s, countries started adopting relatively flexible exchange rate regimes. Under a perfectly flexible exchange rate regime, foreign exchange reserves play only a marginal role. In practice, however, the common exchange rate regime adopted by countries is not a ‘free float’ but an ‘intermediate regime’. Under the intermediate regime, central banks intervene in foreign exchange markets, which necessitates maintenance of adequate stock of foreign exchange reserves. Over time, this need for maintaining foreign

exchange reserves has increased with the acceleration in the pace of globalisation and enlargement of cross border capital flows. Foreign exchange reserves are often also seen as a means of crisis prevention to address unforeseen contingencies.

Recent International Trends in Reserves Holding

7.8 Global foreign exchange reserves have almost doubled from 4.1 per cent to 7.8 per cent of world GDP between 1990 and 2002. Such rapid reserve accumulation continued in 2003 (IMF, 2003a). The share of global reserves held by emerging market countries rose from 37 per cent in 1990 to 61 per cent in 2002, with emerging economies in Asia accounting for much of the increase (Table 7.1). Ironically, the EMEs have accumulated larger volume of reserves, despite a distinct decline in adherence to fixed exchange rate regimes.

Cost and Benefits of Holding Reserves

7.9 An assessment of the costs of holding reserves vis-à-vis their benefits has, for long, been engaging attention of policy makers. The direct financial cost of holding reserves is the difference between interest paid on external debt and returns on external assets in reserves. In any cost-benefit analysis of holding reserves, it is essential to keep in view the objectives of holding reserves, which, inter alia, include: (i) maintaining confidence in monetary and exchange rate policies; (ii) enhancing the capacity to intervene in foreign exchange markets; (iii) limiting external vulnerability so as to absorb shocks during times of crisis; (iv) providing confidence to the markets that external obligations can always be met; and (v) reducing volatility in foreign exchange markets (Jalan, 2003a). Sharp exchange rate movements can be highly disequilibrating and costly for the economy during periods of uncertainty or adverse expectations, whether real or imaginary. If the level of reserves is considered to be in the high comfort zone, it may be possible to attach larger weight to return on foreign exchange assets than on liquidity, thereby reducing net costs of holding reserves. Thus, an inter-temporal view of the adequacy as well as costs and benefits of foreign exchange reserves is needed. It is also necessary to assess the costs of not adding to reserves through open market operations at a time when the capital flows are strong. In other words, the costs and benefits arise as much out of open market operations of the central bank as out of management of levels of reserves.

| Table 7.1: Reserves Accumulation@ | |||||||||

(US $ billion) | |||||||||

| Country | 1990-2003 | 1990-1995 | 1995-1997 | 1997-2000 | 2000-2003 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | Level of |

Reserves | |||||||||

2003* | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Japan | 574.3 | 104.7 | 36.4 | 135.3 | 297.9 | 40.3 | 66.0 | 191.6 | 652.8 |

| China | 376.4 | 45.8 | 67.4 | 25.5 | 237.7 | 47.3 | 75.5 | 114.9 | 406.0 |

| Taiwan Province of China | 137.5 | 23.1 | -7.0 | 22.9 | 98.6 | 15.7 | 37.9 | 44.9 | 206.6 |

| Korea | 140.6 | 17.9 | -12.3 | 75.8 | 59.3 | 6.6 | 18.6 | 34.1 | 155.4 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 93.8 | 30.8 | 37.4 | 14.7 | 10.9 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 6.5 | 118.4 |

| India | 96.1 | 16.1 | 6.4 | 13.2 | 60.4 | 8.0 | 21.7 | 30.6 | 97.6 |

| Singapore | 68.6 | 40.9 | 2.6 | 8.8 | 16.2 | -4.8 | 6.6 | 14.3 | 96.3 |

| Brazil | 47.0 | 42.3 | 1.1 | -18.3 | 21.9 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 16.7 | 54.4 |

| Mexico | 47.5 | 7.0 | 12.0 | 6.7 | 21.9 | 9.2 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 57.4 |

| Thailand | 27.7 | 22.7 | -9.8 | 5.8 | 9.0 | 0.3 | 5.7 | 3.0 | 41.0 |

| Malaysia | 35.1 | 14.0 | -3.0 | 8.7 | 15.4 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 10.7 | 44.9 |

| Indonesia | 28.7 | 6.2 | 2.9 | 11.9 | 7.7 | -1.3 | 3.7 | 5.2 | 36.2 |

| Philippines | 15.9 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 5.8 | 3.7 | 0.4 | -0.3 | 3.7 | 16.8 |

| World | 1,873.6 | 539.7 | 234.0 | 314.5 | 785.4 | 120.5 | 371.8 | 293.0 | 2,806.6 |

Data pertain to end-December; | * : For China as at end-October 2003, Brazil as at end-November 2003 and for World as at end-August 2003. | ||||||||

| @ excluding gold. | |||||||||

| Source: International Financial Statistics, IMF; The Economist; and the Reserve Bank of India. | |||||||||

7.10 The size of reserves holding could be explained by five key factors - size of the economy, current account vulnerability, capital account vulnerability, exchange rate flexibility and opportunity cost (IMF, 2003a). As the population and real per capita GDP increase, reserves are expected to rise. Furthermore, greater current and capital account openness is often associated with higher vulnerability to crisis, which, in turn, is linked to higher level of reserves holding. Again, greater flexibility in the exchange rate reduces the demand for reserves. The size of reserves also depends on the opportunity cost of holding reserves.

7.11 Recent strengthening of the external position of many developing countries through building up of substantial foreign exchange reserves can be viewed from several perspectives (Reddy, 2003). First, it is a reflection of the lack of confidence in the international financial architecture. International liquidity support through official channels is beset with problems relating to adequacy of volumes, timely availability, reasonableness of costs and above all, limited extent of assurances. Second, it is also a reflection of efforts to contain risks from external shocks. Private capital flows which dominate capital movements tend to be pro-cyclical even when fundamentals are strong. It is, therefore, necessary for developing countries to build cushions when times are favourable. High reserves provide some self-insurance which is effective in building confidence including among the rating agencies and possibly in dealing with threat of

crises. Third, the reserve accumulation could also be seen in the context of the availability of abundant international liquidity following the easing of monetary policy in industrial countries which enabled excess liquidity to flow into the emerging markets. In the event of hardening of interest rates in industrialised countries, this liquidity may dry up quickly; in that situation, emerging markets should have sufficient cushion to withstand such reverse flow of capital. Fourth, and most important, the reserve build up could be the result of countries aiming at containing volatility in foreign exchange markets. It should be recognised that the self-corrective mechanism in foreign exchange markets seen in developed countries is conspicuously absent among many emerging markets.

7.12 The accumulation of reserves is also a reflection of imbalances in the current account of some countries. The US has accumulated twin deficits -current account deficit (CAD) of five per cent of GDP, and fiscal deficit of six per cent (a sharp turnaround from a surplus of 1.2 per cent in 2000). With the emergence of such an imbalance in the US, other regions in the world have to exhibit an equal and opposite imbalance in their own account. Ironically, it is the developing countries of Asia who are funding the CAD of the US and exhibiting surpluses. Central banks of Asia are financing roughly 3-3.5 per cent of the CAD of the US and most of its fiscal deficit, as compared to the earlier situation where it was private sector flows that were funding these deficits (Mohan, 2003).

7.13 It is important to note that the level of reserves held by any country is really a consequence of the exchange rate policy being pursued. Capital flows have implications for the conduct of domestic monetary policy and exchange rate management. The manner in which such flows impact domestic monetary policy depends largely on the kind of exchange rate regime that the authorities follow. In a fixed exchange rate regime, excess capital inflows would, perforce, need to be taken to foreign exchange reserves so as to maintain the desired exchange rate parity. In a fully floating exchange rate regime, on the other hand, the exchange rate would adjust itself according to the demand and supply conditions in the foreign exchange market, and as such there would be no need to take such inflows into the reserves.

7.14 High demand for reserves in developing countries can be explained by sovereign risk, political instability, inelastic fiscal outlay and high cost of tax collection and does not reflect any productive investment (Aizenman and Marion, 2003). It has also been argued that accumulating large volume of reserves creates moral hazard problems and reflects insurance against weak domestic fundamentals and political uncertainty (Kapur and Patel, 2003).

7.15 While in practice, all central banks intervene in the foreign exchange markets, a more intensive approach to intervention may be warranted in the EMEs in the context of large capital inflows. In emerging markets, capital flows are often relatively more volatile and sentiment driven, not necessarily being related to the fundamentals. Such volatility imposes substantial risks on market agents, which they may not be able to cope. Even in countries where the exchange rate is essentially market determined,

the authorities often intervene in order to contain volatility and reduce risks to market participants and for the economy as a whole. In such cases, policy makers are confronted with some difficult choices: first, a choice has to be made whether or not to intervene in the foreign exchange market; and second, if the choice is made to intervene, the extent of intervention (RBI, 2003b). Despite the fact that the level of reserves is the consequence of the exchange rate policy and the consequent choices with regard to intervention in the foreign exchange market, reserves can still be evaluated according to the various adequacy indicators.

7.16 Traditionally, the adequacy of reserves was determined by a simple rule of thumb, viz., the stock of reserves should be equivalent to a few months of imports. Such a rule-based reserve adequacy measure stems from the fact that official reserves serve as a precautionary balance to absorb shocks in external payments. Triffin (1960) had suggested 35 per cent of import cover. In terms of import cover, India’s foreign exchange reserves are the highest among major EMEs (Table 7.2).

7.17 The financial crises in the 1990s highlighted the limitations of the traditional approach to reserve adequacy that laid emphasis only on flows of current account. This, coupled with wide ranging changes in financial markets have motivated policy makers to increase their emphasis on the capital account while assessing reserve adequacy. Among various components of capital account transactions, short-term external debt has gained prominence in determining reserve adequacy (Table 7.3). From the perspective of crisis prevention, reserves to short-term debt ratio has emerged as a benchmark to

| Table 7.2: Reserves Adequacy Indicator: Import Cover of Reserves | |||||||||

(Months of imports) | |||||||||

Country | 1990-94 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Japan | 4.9 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 12.3 | 12.4 | 15.1 | 18.3 |

China | 6.5 | 8.2 | 9.8 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 12.4 |

Korea | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 9.8 |

Hong Kong SAR | .. | .. | .. | .. | 5.9 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 6.5 |

Singapore | 6.8 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 9.0 |

| India | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 11.3 | 13.8 |

Brazil | 10.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 9.6 |

Mexico | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

Thailand | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 8.0 |

Malaysia | 5.4 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 5.9 |

Indonesia | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 10.4 |

Philippines | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 5.4 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

.. : Not Available. | |||||||||

| Source: International Financial Statistics, IMF; | For India: Reserve Bank of India, data pertain to financial year (April-March). | ||||||||

| Table 7.3: Debt Related Adequacy Indicators of Select EMEs | ||||||||||

| (Per cent) | ||||||||||

| Reserves to External Debt | Reserves to Short-Term Debt | |||||||||

| Country | ||||||||||

| 1990 | 1995 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 1990 | 1995 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Brazil | 6.2 | 31.0 | 14.3 | 13.6 | 15.8 | 31.4 | 159.1 | 119.0 | 104.9 | 126.4 |

| China | 53.5 | 63.8 | 103.7 | 115.5 | 126.7 | 317.5 | 337.6 | 1,039.1 | 1,286.5 | 490.9 |

| India | 7.0 | 23.1 | 38.7 | 41.8 | 54.8 | 68.3 | 430.8 | 966.4 | 1,165.4 | 1,971.1 |

| Indonesia | 10.7 | 11.0 | 17.5 | 19.8 | 20.1 | 67.0 | 52.8 | 132.0 | 125.9 | 124.9 |

| Korea | 42.3 | 38.1 | 56.7 | 74.9 | 93.3 | 137.0 | 70.1 | 213.0 | 237.6 | 292.6 |

| Malaysia | 63.6 | 69.2 | 73.0 | 70.6 | 70.3 | 511.7 | 326.8 | 508.8 | 636.2 | 597.3 |

| Mexico | 9.4 | 10.1 | 19.0 | 22.4 | 28.3 | 61.3 | 45.2 | 132.1 | 187.6 | 248.6 |

| Philippines | 3.0 | 16.8 | 25.0 | 25.9 | 25.7 | 20.9 | 120.7 | 230.3 | 219.4 | 222.2 |

| Thailand | 47.4 | 36.0 | 35.2 | 40.2 | 48.0 | 159.9 | 81.6 | 145.5 | 215.2 | 244.7 |

| Source: Global Development Finance, World Bank, 2003; | For India, Reserve Bank of India, data pertain to financial year (April-March). | |||||||||

determine the adequacy of reserves. It has been suggested that empirical assessment of reserve adequacy should be so defined that the country can meet its external repayment obligations without additional borrowing for one year - the so called Guidotti Rule (Guidotti, 1999). Taking a similar view, Greenspan (1999) proposed short-term debt by remaining maturity of one year as the yardstick to measure reserve adequacy. The Guidotti rule has subsequently been refined in two aspects: (i) average maturity of the external debt should be three years and above; and (ii) countries must maintain liquidity at risk. There must be a 95 per cent probability of external liquidity being sufficient to avoid new borrowings for one year. The short-term debt vis-à-vis reserves is thus seen as a superior predictor of the depth of crisis over other indicators (Bussière and Mulder, 1999). This suggests that a country’s

liquidity position prior to the onset of a crisis plays an important role in determining exchange market pressure and the potential for a crisis to occur. 7.18 An important aspect of reserve adequacy norms is the identification of various indicators, which can help predict the occurrence as well as depth of crises, and consequently the amount of reserves to be maintained. Apart from reserves to short-term debt ratio, other potential indicators of external vulnerability include: reserves over either monetary base or some measure of money stock, and reserves over GDP. For instance, reserves to monetary base ratio is deemed to reflect the potential for resident-based capital flight from the domestic currency during a financial crisis. Empirical studies, however, find a weak relationship between money based indicators and occurrence and depth of international crises (Reddy, 2002) (Table 7.4).

| Table 7.4: Money Based Reserve Adequacy Indicators | ||||||||||

| (Per cent) | ||||||||||

| Reserves to Broad Money | Reserves to Reserve Money | |||||||||

| Country | 1990-94 | 1995 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 1990-94 | 1995 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Brazil | 10.9 | 25.2 | 20.2 | 23.6 | .. | 22.0 | 119.6 | 94.9 | 104.1 | 56.2 |

| China | 8.0 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 20.0 | 30.3 | 36.8 | 42.8 | 51.4 |

| Hong Kong SAR | .. | 23.0 | 27.9 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 454.0 | 516.2 | 389.4 | 377.4 | 354.6 |

| India | 9.8 | 12.4 | 15.0 | 17.6 | 20.8 | 31.1 | 38.3 | 65.0 | 78.1 | 97.1 |

| Indonesia | 16.8 | 14.1 | 32.4 | 33.4 | 35.3 | 123.0 | 113.5 | 153.5 | 154.0 | 160.3 |

| Korea | 14.3 | 16.4 | 29.4 | 28.9 | 27.7 | 73.2 | 86.4 | 430.5 | 411.1 | 378.9 |

| Malaysia | 40.3 | 31.5 | 32.2 | 32.4 | 30.3 | 163.6 | 123.9 | 132.2 | 147.1 | 135.7 |

| Mexico | 17.6 | 20.2 | 29.7 | 32.3 | 36.2 | 108.5 | 133.1 | 130.6 | 128.6 | 117.2 |

| Philippines | 17.9 | 16.6 | 27.9 | 32.0 | 32.6 | 52.2 | 64.2 | 145.7 | 194.8 | 165.7 |

| Singapore | 86.3 | 95.0 | 81.1 | 77.1 | 79.2 | 490.2 | 568.4 | 750.5 | 696.1 | 714.9 |

| Thailand | 24.4 | 27.1 | 24.7 | 27.1 | 25.4 | 208.6 | 221.8 | 187.6 | 197.7 | 219.5 |

| .. : Not Available. | ||||||||||

| Source: International Financial Statistics, IMF, 2003; For India, Reserve Bank of India, data pertain to financial year (April-March). | ||||||||||

7.19 Stability of select components of the domestic financial markets has also received increasing attention in designing reserve adequacy norms. For instance, volatility in the stock market exerts pressure on the exchange rate, leading to overall financial instability. When the domestic money market, capital market and forward market segments of the foreign exchange markets are closely integrated, the shock in either capital market or money market tends to affect the foreign exchange markets, necessitating the availability of adequate amounts of reserves to mitigate the panic or rumour induced variations in the financial markets.

The Indian Scenario

7.20 India’s foreign exchange reser ves comprising foreign currency assets, gold and Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) have increased significantly since 1991-92. It may be recalled that during the crisis period in 1990-91, the foreign currency assets had dipped below US $ 1.0 billion, covering barely two weeks of impor ts. The subsequent reform period has coincided with a record accretion, especially since 1993. The reserves have almost doubled in the last three years rising from US $ 38.0 billion at end-March 2000 to US $ 75.4 billion at end-March 2003. In the current year (up to January 16, 2004), the reserves have risen further by as much as US $ 27.7 billion to US

$ 103.1 billion, with India being the sixth largest holder of reserves in the world. The reserves have not only increased in absolute terms, but as a per

cent of GDP as well, though this ratio for India is lower than many EMEs (Table 7.5).

7.21 The strength of the foreign exchange reserves has, inter alia, led the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to designate India as a creditor country under its Financial Transaction Plan (FTP). Strong foreign exchange reserves and low interest rates in the domestic markets have enabled the Government to prepay certain foreign currency loans amounting to US $ 5.2 billion during 2003 through outright purchase of foreign exchange from the Reserve Bank. These foreign debts were substituted with domestic debt by the issue of Government securities on private placement basis to the Reserve Bank. These transactions did not have any fiscal or monetary impact, as it was a substitution of external sovereign debt with domestic sovereign debt placed with the Reserve Bank. Corporate bodies have also taken advantage of low international interest rates in prepaying a part of their external commercial borrowings (ECBs). As to the perspective of use of reserves, it may be noted that most of the accretion in reserves in the recent period has been through net purchases by the Reserve Bank in the domestic foreign exchange market for which an equivalent amount of domestic currency has been released to the domestic entities concerned which could decide on their use either for investment, deposits or as liquid assets. To the extent that this counterpart local currency is used by recipient entities for further investment in the economy, the impact on industrial demand and growth would be favourable.

| Table 7.5: Ratio of Reserves to GDP | |||||||||

| (Per cent) | |||||||||

| Country | 1990-94 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Japan | 2.3 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 11.6 |

| China | 7.3 | 10.8 | 13.0 | 15.8 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 15.6 | 18.1 | 23.5 |

| Korea | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 16.4 | 18.2 | 20.8 | 24.1 | 25.5 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 34.7 | 39.1 | 40.7 | 53.4 | 54.3 | 59.9 | 65.0 | 67.8 | 68.7 |

| Singapore | 81.1 | 82.8 | 84.5 | 75.2 | 90.9 | 92.7 | 87.4 | 88.7 | 94.3 |

| India | 3.6 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 11.5 | 14.5 |

| Brazil | 4.6 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 8.3 |

| Mexico | 4.7 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 7.9 |

| Thailand | 18.3 | 21.4 | 20.7 | 17.3 | 25.8 | 27.8 | 26.1 | 28.1 | 30.1 |

| Malaysia | 29.6 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 20.7 | 35.4 | 38.6 | 32.7 | 34.6 | 36.1 |

| Indonesia | 7.0 | 6.8 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 23.8 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 18.8 | .. |

| Philippines | 7.1 | 8.6 | 12.1 | 8.8 | 14.2 | 17.4 | 17.2 | 18.7 | 16.9 |

| .. : Not Available. | |||||||||

| Note | : The countries in this table have been arranged in a descending order based on their absolute level of reserves in 2002. | ||||||||

| Source | : International Financial Statistics, IMF, 2003. | For India, Reserve Bank of India and Central Statistical Organisation, data pertain to | |||||||

| financial year (April-March). | |||||||||

7.22 Addition to reserves in the last few years in India largely reflects higher remittances, quicker repatriation of export proceeds and non-debt inflows while the overall level of external debt has remained virtually unchanged. Even after taking into account foreign currency denominated NRI flows (where interest rates are linked to LIBOR), the financial cost of additional reserve accretion in India in the recent period is quite low.

7.23 A concern has been expressed in several fora that accretion to foreign exchange reserves in India has resulted from capital inflows induced by 'arbitrage' motives. Indian interest rates have come down substantially in the last three or four years. To an extent, these interest rates are still higher than those prevailing in the U.S., Europe, U.K. or Japan. This provides an 'arbitrage' opportunity to the holders of liquid assets abroad, who may take advantage of higher domestic interest rates in India leading to a possible short-term upsurge in capital flows. However, there are several considerations, which indicate that ‘‘arbitrage’’ per se is unlikely to have been a primary factor in influencing remittances or investment decisions by NRIs or foreign entities (Jalan, 2003b). These include:

The minimum period of deposits by NRIs in Indian rupees is now one year, and the interest rate on such deposits is subject to a ceiling rate of 25 basis points over LIBOR/swap rates (interest rates on dollar deposits by NRIs are actually below LIBOR).

Outside of NRI deposits, investments by Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) in debt funds is subject to an overall cap of only US $ one billion in the aggregate. In other words, the possibility of arbitrage by FIIs in respect of pure debt funds is limited.

Interest rates and yields on liquid securities are highly variable abroad as well as in India, and the differential between the two rates can change very sharply within a short time depending on market expectations. The yield on 10-year Treasury note in the U.S. was around 4.04 per cent as compared with 5.14 per cent on Government bonds of similar maturity in India as on January 21, 2004. Taking into account the forward premia on dollars and yield fluctuations, except for brief period, there is likely to be little incentive to send large amounts of capital to India merely to take advantage of the interest differential.

India’s Approach to Reserve Management

7.24 India’s approach to reserve management, until the balance of payments crisis of 1991, was based on the traditional approach, i.e., to maintain reserves in relation to imports. With the introduction of a market determined exchange rate, the emphasis on import cover was supplemented with the objective of smoothening out the volatility in the exchange rate (RBI, 1996).

7.25 The High Level Committee on Balance of Payments (Chairman: C Rangarajan, 1993) had recommended that due attention be paid to payment obligations in addition to the traditional measure of import cover of 3 to 4 months. Subsequently, against the backdrop of currency crises in East-Asian countries, and in the light of country experiences of volatile cross-border capital flows, the Reserve Bank identified the need to hold a level of reserves assets, that could be considered as adequate, taking into consideration a host of factors such as the stock of short term and volatile external liabilities, shift in the pattern of leads and lags in payments/receipts during exchange market uncertainties along with the conventional norm of cover for sufficient months of imports (RBI, 1998). The Reserve Bank also took note of suggestions from Guiddotti (1999) and Greenspan (1999) which take into account the foreseeable risks that a country could face under a range of possible outcomes for relevant financial variables like exchange rates, commodity prices and credit spreads.

7.26 In the recent period, the overall approach to management of India’s foreign exchange reserves has mirrored the changing composition of balance of payments, and has endeavoured to reflect the ‘liquidity risks’ associated with different types of flows and other requirements. The policy for reserve management is thus judiciously built upon a host of identifiable factors and other contingencies. Such factors, inter alia, include: the size of the current account deficit; the size of short-term liabilities (including current repayment obligations on long-term loans); the possible variability in portfolio investments and other types of capital flows; unanticipated pressures on the balance of payments arising out of external shocks (such as the impact of the East Asian crisis in 1997-98 or increase in oil prices in 1999-2000); and movements in the repatriable foreign currency deposits of non-resident Indians. A sufficiently high level of reserves is necessary to ensure that even if there is prolonged uncertainty, reserves can cover the ‘‘liquidity at risk’’

| Table 7.6: Reserve Adequacy Indicators: India | ||||||

| (per cent) | ||||||

| Year | Import | Reserves | Reserves | Reserves | Reserves | Net |

| Cover of | to | to | to | to Short- | Foreign | |

| Reserves | Reserve | Broad | External | Term | Exchange | |

| (months) | Money | Money | Debt | Debt | Assets | |

| (NFEA) to | ||||||

| Currency | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1990-91 | 2.5 | 13.0 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 68.3 | 14.4 |

| 1991-92 | 5.3 | 24.0 | 7.5 | 10.8 | 130.4 | 29.6 |

| 1992-93 | 4.9 | 27.8 | 8.4 | 10.9 | 155.1 | 31.8 |

| 1993-94 | 8.6 | 43.6 | 14.0 | 20.8 | 530.9 | 60.2 |

| 1994-95 | 8.4 | 47.1 | 15.1 | 25.4 | 590.0 | 71.4 |

| 1995-96 | 6.0 | 38.3 | 12.4 | 23.1 | 430.8 | 60.4 |

| 1996-97 | 6.5 | 47.5 | 13.6 | 28.3 | 392.8 | 69.1 |

| 1997-98 | 6.9 | 51.2 | 14.1 | 31.4 | 582.0 | 76.7 |

| 1998-99 | 8.2 | 53.2 | 14.1 | 33.5 | 760.2 | 78.5 |

| 1999-00 | 8.2 | 59.1 | 14.8 | 38.7 | 966.4 | 84.2 |

| 2000-01 | 8.6 | 65.0 | 15.0 | 41.8 | 1,165.4 | 90.4 |

| 2001-02 | 11.3 | 78.1 | 17.6 | 54.8 | 1,971.1 | 105.2 |

| 2002-03 | 13.8 | 97.1 | 20.8 | 72.0 | 1,650.9 | 126.8 |

| Source: Reserve Bank of India. | ||||||

on all accounts over a fairly long period. Furthermore, the quantum of reserves in the long-run should be in line with the growth in the economy and the size of risk-adjusted capital flows, which provides greater security against unfavourable or unanticipated developments that can occur quite suddenly. Taking these factors into account, India’s foreign exchange reserves are presently comfortable. Trends in select indicators show progressive improvements during 1990s (Table 7.6).

Benchmarking Reserve Management Practices in India

7.27 Reserve management in a central bank is quite different from that of risk management by portfolio managers in other financial institutions. Reserve management encompasses preservation of the long-term value of reserves in terms of purchasing power and the need to minimise risk and volatility in returns given the parameters of safety, liquidity and profitability. India was one of the 20 countries selected for a case study in a recent document published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2003b) as a supplement to the IMF’s ‘‘Guidelines for Foreign Exchange Reserve Management’’. The IMF study clearly brings out that the basic traditional objectives of reserve management, viz., safety, liquidity and return are evident across all countries included in the case study. However, increasingly the focus is on efficient management of reserves in order to maximise return (or reduce costs) while preserving capital and

liquidity. The case study clearly brings out that India, along with Hong Kong, Israel, and Tunisia consider preservation of purchasing power of reserves as a long-term objective. An attempt has been made to discuss the reserve management practices in the Reserve Bank as a case study in the light of general policies pursued by various countries (IMF, 2003b).

7.28 The essential framework for reserve management in the Reserve Bank is provided by the legal enactments as regards currency, market and instruments for investment. The legal parameters are provided in the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. Broadly, the law permits the following investment categories: (i) deposits with other central banks and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS); (ii) deposits with foreign commercial banks; (iii) instruments representing sovereign/sovereign-guaranteed debt where residual maturity does not exceed 10 years; and, (iv) other instruments/ institutions as approved by the Central Board of the Reserve Bank.

7.29 The reserve management strategies are continuously reviewed by the Reserve Bank in consultation with the Government. In deploying reserves, attention is paid to the currency composition and duration of investment. All foreign currency assets are invested in assets of top quality while a good proportion is convertible into cash at short notice. The choice of the highest possible quality investment instruments and explicit constraints on critical portfolio variables, such as limits on various securities, currencies, counter-parties and sovereigns form the basic elements of reserve management. The counterparties with whom deals are conducted are also subject to a rigorous selection process. Counterparties could be banks, subsidiaries of banks or security houses. Such counter parties are approved by the Reserve Bank taking into account their international reputation and track record apart from factors such as size, capital, credit rating, financial position and service provided by them. The reserves are also invested in money market including deposits with top international commercial banks.

External Asset Managers

7.30 Several EMEs, such as Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Korea use external managers for reserve management. In India, a small portion of the reserves has been assigned to external asset managers with the objectives of gaining access to and deriving benefit from their market research. It also helps to take

advantage of the technology available with asset managers while utilising the relationship to have the required training/exposure to the Reserve Bank’s personnel responsible for foreign exchange reserve management. The asset managers are carefully selected from among the internationally reputed asset management companies. They are given clear investment guidelines and benchmarks and their performance is evaluated at periodic intervals by a separate unit within the middle office. External asset managers’ views and outlook on international bond and currency markets are examined and taken as inputs.

Audit and Management Information System

7.31 In almost all EMEs participating in the IMF case study (IMF, 2003b), reserve management activities are audited annually by an independent external auditor as part of the annual audit of the reserve management entity’s financial statements to ensure compliance with appropriate accounting standards. In the Reserve Bank, there is a system of concurrent audit for monitoring compliance in respect of all the internal control guidelines, independent of the process flows. Furthermore, reconciliation of nostro accounts is done on a daily basis in respect of major currencies. In addition to the annual inspection by the Inspection Department of the Reserve Bank and Statutory Audit by external auditors, there is a system of appointing a management auditor to audit dealing room transactions. The main objective of such an audit is to see that risk management systems are functioning properly and internal control guidelines are adhered to.

Risk Management Practices

7.32 Higher reserve levels, expanding asset classes, more sophisticated instruments and more volatile financial markets have increased the need for risk management. Risk management entails the existence of a framework that identifies, assesses and allows the management of risks within acceptable parameters and levels. A risk management framework seeks to identify the possible risks that may impact on portfolio values and to manage those risks through the measurement of exposures, and where necessary, by supporting procedures to mitigate the potential effects of these risks. The overall stance of the Reserve Bank’s reserve management policy continues to be a risk averse one aiming at stable returns. The Reserve Bank has put in place sound systems to identify, measure, monitor and control credit risk, market risk (arising out of currency and

interest rate movements), liquidity risk and operational risk. Within the parameters of safety and liquidity return optimisation dictates operational strategies.

Credit Risk

7.33 Reserve management entities are exposed to credit risk on all deposits, investments and off-balance sheet transactions. All the countries surveyed by the IMF (2003b) were found to be very sensitive to credit risk and, therefore, invested the bulk of their assets in securities or deposits of highly rated sovereigns, rated international banks, international financial institutions and the BIS. Many countries allowed the use of derivatives, mainly for market risk management, although the nature of derivatives allowed varied from country to country. In India, credit risk has been addressed by instituting a framework under which investment is made in financial instruments issued by Triple A rated sovereigns, banks and supra-nationals apart from those with the BIS. Investments in bonds/treasury bills, which represent debt obligations of Triple A rated sovereigns and supra-national entities do not give rise to any substantial credit risk. However, placement of deposits with commercial banks as also transactions in foreign exchange and bonds/treasury bills with commercial banks/security firms give rise to credit risk. Stringent credit criteria are, therefore, applied to selection of approved counterparties. Fixation of limits for each category of transactions is also in place. Ratings given by international rating agencies as also various other financial parameters are considered before grading and fixing limits in respect of each counterparty. Day-to-day developments in respect of the counter-parties are closely monitored to identify institutions whose credit quality is under potential threat.

Market Risk

7.34 Most of the high reserve-holding countries have developed a framework and capacity to assess market risks involved in reserve management operations based on a benchmark por tfolio. Determination of the optimal currency distribution is a critical decision in reserve management since currency risk is an area where reserve management entities confront high market risk. In recent years, the major reserve holding Asian economies have revealed a common tendency towards shifting away from dollar denominated reserve assets to Euro and other currencies in the face of a weak dollar as a part of their currency risk management policies. Central banks of China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and

South Korea accumulated ‘‘unprecedented’’ accretions of foreign reserves in 2003, but it is reported that they did not place those reserves in US dollar assets.

7.35 In India, under market risk, currency as well as interest rate risks are identified and appropriately managed. Currency risk arises due to uncertainty in exchange rates. Foreign currency reserves are invested in multi-currency multi-market portfolios. In tune with international trends, the Reserve Bank follows the practice of expressing the foreign exchange reserves in US dollar terms. Operationally, this means that the share of the US dollars in the reserves would increase or decrease depending on whether the US dollar is appreciating or depreciating vis-à-vis other major currencies. Decisions are taken regarding the exposure on different currencies depending on the likely currency movements and other considerations in the medium- and long-term such as the necessity of maintaining major portion of reserves in the intervention currency and that of maintaining the approximate currency profile of the reserves in tune with the changing external trade profile of the country.

7.36 The central aspect of the management of interest rate risk for a central bank is to protect the value of the investments from the adverse impact of the interest rate movements. Interest rate risk is managed in most countries by defining target duration that depends on the risk-return preference of the reserve management entity. Countries like Australia, Brazil, Colombia and the Czech Republic address interest rate risks through minimising the probability of capital loss over certain time horizon. Many countries like Australia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Hong Kong, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand and the UK use value at risk method to limit market risk.

7.37 In India, the interest rate sensitivity of the reserves portfolio is identified in terms of benchmark duration and the permitted deviation around the benchmark. The emphasis is to keep the duration short, which is in tune with the approach to remain risk averse and keep a liquid portfolio. Short duration also implies a cautious approach on the liquidity front and a conservative approach on the returns front. The benchmark duration as also the leeway are suitably altered keeping in view the market dynamics. Given the currency composition of the reserve portfolio and the liquidity level, a decision is then taken as to how much of the portfolio should be in bonds. There are four broad currencies into which the reserves are

allocated: US Dollar, Euro, Pound Sterling and Japanese Yen. A benchmark based on the risk tolerance levels accepted and set by the management is specified for each portfolio to evaluate performance.

Liquidity Risk

7.38 Risk arising out of inadequate liquidity can create a serious problem for a reserve management entity at times of crisis as reserves are essentially held to meet unexpected needs. The reserve management entity has to decide how much liquidity to hold and in what form, and the decision involves assessment of likely future intervention and future calls on the reserves. India, along with a number of countries such as Colombia, Hong Kong, Hungary, Israel and Korea use stress test for liquidity assessment. Certain other countries like Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Turkey and the UK also use stress tests for market exposures. A majority of countries allow active management within limits, ranges, tracking error or 'value at risk (VaR)' limits. Performance is measured on an absolute as well as relative basis which includes the use of performance attribution models in some cases. In India, efforts are made to manage the liquidity risk by appropriate choice of instruments. While bonds and treasury bills of Triple A rated sovereigns are highly liquid, BIS fixbis/Discount fixbis can be liquidated at any time to meet the liquidity needs. Exercises are undertaken to estimate ‘‘liquidity at risk (LaR)’’ of reserves.

Operational Risk

7.39 There is a total separation of the front office and back office functions in India and the internal control systems ensure several checks at the stages of deal capture, deal processing and settlement. The middle office is responsible for risk measurement and monitoring, performance monitoring and concurrent audit. The deal processing and settlement system in the Local Area Network (LAN) is also subject to internal control guidelines based on the principle of one point data entry and powers are delegated to officers at various levels for generation of payment instructions. To subject the dealers to a high degree of integrity, a code of conduct has been prescribed.

Custodial Risk

7.40 A major portion of the securities held by India is custodised with the central banks. While all US Government securities are held with the Federal

Reserve, all UK gilts and Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) are with the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan, respectively. All primary cash accounts are with the central banks in respective countries. BIS provides both custodial and investment services and accordingly they are also the custodians for investments with them. A small portion of other Euro securities and assets managed by external asset managers are custodised with carefully selected global custodians. The custodial arrangements are reviewed from time to time and developments relating to the custodians are monitored regularly to ensure that the risk is kept to the minimum.

Management of Gold Reserves

7.41 The Reserve Bank has a modest gold holding of 357 tonnes; of this, 65 tonnes (18.2 per cent of total gold holdings of the Reserve Bank) is held abroad. The fact that gold held with the Reserve Bank provides an ample cushion to the reserves of the country was demonstrated in the critical periods of the foreign exchange crisis in 1991. Loans were raised against the collateral of gold from the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England. On repayment of the loans in November 1991, the gold was not brought back and since December 1991, but was placed as gold deposits with Bank of England and BIS (the latter on a specific request, as BIS normally does not accept gold deposits). These gold stocks are in short-term interest bearing deposits in terms of provisions of the Reserve Bank of India Act, and they earn a return of about one per cent per annum.

7.42 In this connection, the recommendation of the High Level Committee on Balance of Payments (Chairman: C. Rangarajan) is relevant. The Committee had stated that it would be advantageous to locate about one-fourth of the gold holding of the Reserve Bank at an offshore centre so that the same could be utilised in times of need. In terms of Section 33(2) of the RBI Act, gold should be held at least to the extent of Rs.115 crore (which translates into a physical quantity of 3 tonnes approximately at current market price) as assets in the Issue Department. Furthermore, as per Section 33 (5) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, not less than 85 per cent of the gold held as assets of the Issue Department shall be held in India.

7.43 To sum up, India’s foreign exchange reserves have risen significantly in the last few years. From the point of view of the central bank, the level of reserves is intricately linked with the exchange rate management.

Based on the various reserve adequacy indicators, the level of foreign exchange reserves in India is comfortable. India has also been included as a creditor country under the FTP at the IMF in view of its comfortable level of reserves. Prepayment of certain loans has been carried out by India. The actual impact of the foreign exchange reserve management policies followed by India has been highly positive as it resulted in orderly movements in exchange rates with lower volatility. Together, these developments have led to a sharp increase in the confidence level of domestic and foreign investors in the strength of the Indian economy. India’s reserve management policies have also been described by the IMF as being ‘‘comparable to global best practices’’ in a recent study of 20 select industrial and developing countries (IMF, 2003b).

II. MANAGEMENT OF EXCHANGE RATES

7.44 Conduct of exchange rate policy in an open economy framework has become increasingly complex for EMEs especially in the presence of increased volatility in international capital flows that has resulted from integrated global financial markets. Increased capital mobility, greater exposure to exchange rate risk, increased openness to international trade and shift in the composition of exports from primary products towards manufactures and services are the major features witnessed in the EMEs in the past decade. Emergence of new financial institutions and products within a weak financial infrastructure acts as a source of additional vulnerability for them (Hoe Ee, 2001). Moreover, rapid advances in telecommunication and information technology have dramatically lowered transaction costs and reaction times for market participants, which have contributed to sharp increases in the volume and mobility of capital flows. All these factors, together, have amplified the vulnerability of the EMEs to financial crises, which has led to an increase in their frequency. Taking into account all the external factors described above, the task of designing a country’s exchange rate policy, i.e., the choice of appropriate exchange rate regime and development of a sound foreign exchange market has been challenging.

7.45 Against this backdrop, this section begins with a brief discussion on the theory of exchange rate determination followed by the evolving debate on the choice of exchange rate regime, especially in the context of recent financial crises. The Section then dwells on the evolution of the exchange rate management in India, highlighting that flexibility and

pragmatism are required in the management of exchange rate in developing countries, rather than adherence to strict theoretical rules. The role of the Reserve Bank in developing the foreign exchange market in India along with an analysis of its impact on market efficiency is also covered.

Exchange Rate Determination in an Open Economy Framework

7.46 Exchange rate economics was dominated by innovation and rapidly changing ideas during the period from mid-1970s to the early 1980s. During that period, there were major competing schools of exchange rate theory (the monetary and portfolio models) that attracted efforts at theoretical extension and a considerable amount of empirical work. However, as the empirical work refuted the contending theoretical approaches, the theories of exchange rate determination suffered a setback. The theory of exchange rate determination, therefore, still lacks models that are both theoretically interesting and empirically defensible (Krugman, 1993).

7.47 The earliest and simplest model of exchange rate determination, known as the purchasing power parity (PPP) theory, represented the application of ‘‘the law of one price’’. It states that arbitrage forces will lead to the equalisation of goods prices internationally once the prices are measured in the same currency. PPP theory provided a point of reference for the long-run exchange rate in many of the modern exchange rate theories. Empirical evidence showed that PPP performs better for those countries that are geographically close to each other and where trade linkages are high. Moreover, PPP holds better for traded goods compared to non-traded goods (Officer, 1986). Reasons for failure of PPP may be attributed to heterogeneity in the baskets of goods considered for construction of price indices in various countries, presence of transportation cost and other trade impediments like tariff, imperfect competition in goods market, and increase in the volume of global capital flows during the last few decades which led to sharp deviation from PPP.

7.48 The failure of the PPP theory to explain real world exchange rate behaviour gave rise to a set of monetary models which took into account the possibility of capital/bond market arbitrage apart from goods market arbitrage assumed in the PPP theory. In the monetary models, it was the money supply in relation to money demand in both home and foreign

country, which determined the exchange rate. Among the various monetary models put forward, the most significant were the ‘flexible price’, ‘sticky price’ and ‘real interest differential’ models. A common starting point for all the three monetary models was the assumption of uncovered interest parity (UIP) condition.

7.49 The ‘flexible price’ monetary models (Frenkel, 1976; Mussa, 1976; Bilson, 1978) assumed that all prices in the economy are perfectly flexible both upwards and downwards in both short and long run. They also incorporated a role for inflationary expectations. In such models, countries with high monetary growth rates would have high inflationary expectations which could lead to a reduction in the demand to hold real money balances, increased expenditure on goods, a rise in domestic price level and a depreciating currency in order to maintain PPP. Empirical tests of the flexible price monetarist model provided weak results. One of the major deficiencies of the flexible price monetarist model was that it assumed that PPP holds continuously and that the prices were as flexible upwards and downwards as the exchange rates.

7.50 The ‘sticky price’ model, which was first elaborated by Dornbusch (1976), introduced the concept of exchange rate overshooting and provided an explanation for both exchange rate volatility and misalignment from the PPP. The basis underlying the model was that the prices in the goods market and wages in the labour market were determined in ‘sticky price’ markets and they only tended to change slowly over time in response to various shocks such as changes in the money supply. Prices were specially resistant to downward pressure. But the exchange rate, being determined in the flexible price market, could appreciate and depreciate immediately in response to new developments and shocks. In such circumstances, exchange rate changes were not matched by corresponding price changes and there could be persistent and prolonged departure from PPP. If real output was fixed, a monetary expansion in the short-run would lower the interest rates and cause the exchange rate to overshoot its long run depreciation, i.e., the short-run exchange rate would fall below its long run equilibrium level. The phenomenon of overshooting of spot exchange rate explained the empirical evidence of large and prolonged deviation of the exchange rate from the PPP. The ‘real interest differential model’ combined the role of inflationary expectations of the flexible price monetary model with the sticky prices of Dornbusch model.

7.51 Among the various shortcomings, perhaps the most noticeable weakness of the monetary models of exchange rate determination was the absence of an explicit role for the current account to influence exchange rates. Furthermore, domestic and foreign bonds were regarded as perfect substitutes - they were regarded as equally risky so there was no role for risk perception to play a part in determination of exchange rates. This shortcoming of the monetary models was taken into account in portfolio balance models of exchange rate determination, which allowed for the possibility that international investors may regard domestic and foreign bonds as imperfect substitutes of each other. The portfolio balance models gave importance to the current account in determination of exchange rate over time. A current account surplus implied an accumulation of foreign assets and the result was a larger proportion of foreign bonds in investor’s portfolio than they desired. Given the imperfect substitution between domestic and foreign bonds, this results in appreciation of the exchange rate. Although the portfolio balance model allowed for the departures from the uncovered interest parity (UIP) due to existence of a risk premium, there was no strong empirical evidence to support it as an alternative to the monetary models.

Choice of Exchange Rate Regime

7.52 One of the most debated issues in the international economics is the choice of exchange rate regime. The early literature on the choice of exchange rate regime viewed that a fixed exchange rate regime would serve better for the smaller and more open economies. Given the sacrifice of monetary freedom, the protagonists of fixed exchange rate favoured this system for two main reasons, viz., (i) absence of unpredictable volatility, both from the perspective of short-term and long-term; and (ii) help in restraining domestic inflation pressure by pegging to a low inflation currency and providing a guide for private sector inflation expectations. According to its supporters, the most extreme forms of fixed exchange rate regimes, known as ‘‘super fixed’’ or ‘‘hard pegs’’, provide credibility, transparency, very low inflation and financial stability to the economy concerned. By reducing speculation and devaluation risk, hard pegs are believed to keep the interest rates lower and more stable compared to any other alternative regime. Currency board, dollarisation and monetary union are some of the examples of super fixed exchange rate regime.

7.53 Recent international experience suggests that in a world of global capital mobility, fixed exchange

rates are difficult to sustain. It is interesting to note that all the EMEs, which were severely affected by recent crises, had either followed some kind of exchange rate peg or had substantially limited their exchange rate movement through various types of controls. However, international experience also suggests that it was not the relative fixity of the exchange rates alone which was responsible for the currency crises. Generally, other macroeconomic factors, viz., large fiscal deficits (Russia, Brazil) and weak financial systems (Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia), were instrumental in setting off the crisis. Under these circumstances, attempts by the authorities to maintain their exchange rate peg aggravated the crisis. Clearly, therefore, changing the exchange rate regime alone cannot automatically correct other critical problems. In order to avoid these fundamental weaknesses, it was felt that EMEs should pursue a more sound, better managed and better supervised financial system and limit the exposure to foreign currency denominated external debt. Improvement in these key areas would tend to make the pegged exchange rate regimes less vulnerable and more tenable for countries with significant involvement in modern global financial markets.

7.54 The conventional wisdom suggests that for successful conduct of a pegged exchange rate regime, it is essential to fulfil the following conditions: (i) low degree of involvement with international capital markets; (ii) high share of trade with the country to which it is pegged; (iii) the shocks faced are similar to those facing the country to which it is pegged; (iv) willingness to give up monetary independence for its partner’s monetary credibility; (v) extensive reliance on economic and financial system of its partner’s currency; (vi) flexible and sustainable fiscal policy; (vii) flexible labour markets; and (viii) high international reserves (Mussa et al, 2000). Applying these criteria, countries for which pegged exchange rates seem to remain appropriate are small economies with a dominant trading partner that maintains a reasonably stable monetary policy.

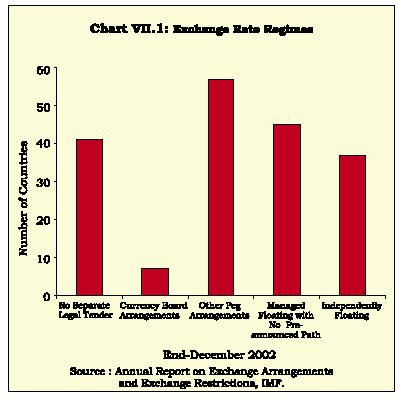

7.55 International experience reveals that a large number of small countries have pegged their exchange rate regimes (Chart VII.1). Small Caribbean island economies, some small Central American countries and some Pacific island economies peg to the US dollar. African countries like Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland peg to the South African Rand. Countries like Nepal and Bhutan peg their currency to the Indian rupee, while Brunei Darussalam pegs to the Singapore dollar. Developing countries that face

difficulties in stabilising their economies from a situation of high inflation have also opted for pegged exchange rate systems and pursue exchange rate based stabilisation programme.

7.56 Beyond these specific groups, there are a significant number of countries for which some form of pegged exchange rate, tight band, crawling band or heavily managed float is deemed to be the relevant exchange rate regime. As against fixed and flexible exchange rates, the crawling band was seen by Williamson (1996) as a sensible, middle-of-the-road position, appropriate for most countries. Among the other forms of intermediate exchange rate regimes, Krugman (1991) provided the basic theory of target zones to describe a band that did not necessarily crawl. Cross-countr y experiences reveal that countries like Denmark, Egypt, Hungary (horizontal bands), Bolivia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua (crawling peg), Romania, Uruguay and Israel (crawling band) adopted various forms of intermediate exchange rate regimes. However, the viability of intermediate regimes in the context of open capital account is uncertain. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the repeated crises in the 1980s and the emerging market crises during the 1990s highlight the uncertainty of intermediate regimes especially for countries with open capital account. Under unrestricted international mobility of financial capital, all intermediate regimes, including actively managed

float are accidents, waiting to happen and cannot survive for long (Buiter, 2000).

7.57 Advocates of floating exchange rate regime emphasised that it allowed monetary policy to be used to steer the domestic economy (Friedman, 1953). It was argued that it was much easier to change one price, namely the exchange rate, than to alter thousands or millions of individual prices, when an economy needed to enhance (or reduce) its international price competitiveness in the interest of balance of payments adjustment. Furthermore, given the impossible trinity1, the best choice was to give up the fixed exchange rate and thus adopt a flexible one. International experience reveals that apart from the G-3 countries, a number of medium-sized industrial countries, viz., Canada, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and United Kingdom have also maintained floating exchange rate regimes. The main disadvantage of a free float is a tendency towards volatility that is not always due to macroeconomic fundamentals. This is especially so in emerging markets where the foreign exchange markets are relatively thin and dominated by a small number of players. In addition, financial markets may not be deep or broad enough to allow hedging at a reasonable cost.

7.58 After the Asian financial crisis, views were expressed that for small open economies, the only viable exchange rate regime was one of the corner solutions - either a hard currency peg like a currency board arrangement in the one extreme or allow market forces to freely determine the value of their currencies, on the other. The recent Argentinean crises gave a severe jolt to the theory of ‘‘hollowing of the middle’’. Even currency board type of arrangement of a fixed peg was found to be unviable. There are a number of difficulties associated with super-fixed systems including complete loss of monetary control on the part of central bank (Edwards, 2003).

7.59 In the recent period, growing dominance of intermediate regimes seriously challenged the new paradigm on ‘‘two corner’’ exchange rate regimes. Calvo and Reinhart (2000) and Levy-Yeyati and Sturzenegger (2000) have shown that many of those countries which had declared themselves as ‘‘independent floaters’’ in the IMF statistics were indeed heavily intervening in foreign exchange markets. Thus, in most cases ‘‘floating’’ means ‘‘managed floating’’. Studies by the IMF and several

experts also show that by far, the most common exchange rate regime adopted by countries, including industrial countries, is not a free float. Most countries have adopted intermediate regimes of various types, such as, managed floats with no pre-announced path, and independent floats with foreign exchange intervention moderating the rate of change and preventing undue fluctuations. This has also been true of industrial countries. Results of a recent study indicate that for countries at a relatively early stage of financial development and integration, fixed or relatively rigid schemes appear to offer some anti-inflation credibility without compromising growth objectives. As countries develop economically and institutionally, there appear to be considerable benefits to more flexible regimes (Rogoff et al., 2003).

7.60 Some stylized facts regarding the foreign exchange markets in the EMEs are noteworthy. Most EMEs have smaller and localised foreign exchange markets where nominal domestic currency values are generally expected to show a depreciating trend, since relative inflation rates are generally higher than those of major industrial countries. In this situation, there is a common tendency among market par ticipants to hold long positions in foreign currencies and to hold back sales when expectations are adverse and currencies are depreciating. Another feature, very common to the EMEs, is the tendency of importers/exporters and other end-users to look at exchange rate movements as a source of return without adopting appropriate risk management strategies. This, at times, creates severely uneven supply-demand conditions, often based on ‘‘news and views’’. The day-to-day exchange rate movements are not aligned with the so-called ‘fundamentals’ or country’s capacity to meet its payments obligations, including debt service. This leads to adverse expectations, which tend to be self-fulfilling in nature, given their effect on ‘‘leads and lags’’ in payments and receipts. Often, a self-sustaining triangle develops comprising the supply-demand mismatch, increased inter-bank activity to take advantage, and accentuated volatility triggered by negative sentiments. The consequent volatility that sets in may not be in tune with the fundamentals. The situation calls for a quick intervention/response by the authorities. Given the ‘‘bandwagon’’ effect of any adverse movement and the herd behaviour of market participants, the situation can lead to further buying or hedging activity among non-bank participants. The ‘‘Daily Earnings At Risk’’ (DEAR) strategies of risk management tend to reinforce herd

behaviour (Jalan, 2001). In thin and underdeveloped markets dominated by a few leading operators, there is a natural tendency to do what everyone else is doing in the event of any adverse development rather than taking a contra position.

7.61 The reason why intervention by most central banks in foreign exchange markets becomes necessary from time to time is primarily because of the importance of capital flows in determining exchange rate movements as against trade deficits and economic growth, which were important in the earlier days. Second, unlike trade flows, capital flows in ‘‘gross’’ terms, which affect exchange rate can be several times higher than ‘‘net’’ flows on any day. Therefore, herding becomes unavoidable (Jalan, 2003b).

7.62 Capital movements have rendered exchange rates significantly more volatile than before (Mohan, 2003). The volatility in capital flows was again highlighted in the recent period during the East Asian crisis. Net private capital flows to EMEs, for instance, fell from US $ 227 billion in 1996 to a mere US $ 43 billion in 2001. The volatility in such flows is better captured through movements in flows in the form of bank lending and other debt flows. Such flows indicated a sharp turnaround from an inflow of US $ 67 billion in 1995 to an outflow of US $ 115 billion in 2000 (see Chapter VI for details). Since the 1980s, vicissitudes of capital movements have shown up in volatility in exchange rate movements with major currencies moving far out of alignment of underlying purchasing power parities. Of late, it is capital flows that seem to move exchange rates and account for much of their volatility. Instead of the real factors underlying trade competitiveness, it is expectations and reactions to news which drive capital flows and exchange rates, often out of alignment with fundamentals. Capital flows have been observed to cause overshooting of exchange rates as market participants act in concert while pricing information. Foreign exchange markets are prone to bandwagon effects. In this context, it would be desirable to take note of the balance sheet approach, which identifies financial inter-linkages, imbalances, vulnerabilities and risks in the economy. It focuses on the risks created by maturity, currency and capital structure mismatches. This framework draws attention to the vulnerabilities created by debt among residents, particularly those denominated in foreign currency, and it helps to explain how problems in one sector can spill over into other sectors eventually triggering balance of payments crisis (see Chapter VI).

7.63 For the majority of developing countries which continue to depend on export performance as a key to the health of their balance of payments, exchange rate volatility has had significant real effects in terms of fluctuations in employment and output and the distribution of activity between tradables and non-tradables (Mohan, 2003). In the fiercely competitive trading environment where countries seek to expand market shares aggressively by paring down margins, it has been argued, even a small change in exchange rates can develop into significant and persistent real effects. The impact of greater exchange rate volatility has been significantly different for reserve currency countries and for developing countries. For the former, mature and well-developed financial markets have absorbed the risks associated with large exchange rate fluctuations with negligible spillover on to real activity. Consequently, the central bank does not have to take care of these risks through its monetary policy operations. On the other hand, for the majority of developing countries, which are labour-intensive exporters, exchange rate volatility has had significant employment, output and distributional consequences, which can be large and persistent (Mohan, 2003).

7.64 The volatility and misalignment in the G-3 exchange rates, combined with inflexible exchange rate regimes of certain EMEs, appear to have played a role in the build-up to the Argentine and Asian crises and the associated large losses in output (IMF, 2003a). More generally, the volatility in the real effective exchange rate of the developing countries could be ascribed to the volatility of the major currencies. Empirical studies point towards costly geographical reorientation of external trade since relative competitiveness vis-à-vis different partner countries undergoes changes with large movement in major exchange rates. It also increases risk to investment across different regions. Furthermore, large swings in the G-3 exchange rates could require costly hedging products for developing countries lacking sophisticated foreign currency derivative products and could amplify debt-servicing with disruptions to fiscal budgets.

7.65 Central banks all over the world are, therefore, concerned about development of foreign exchange market in order to allow market participants to manage their own risks i.e., micro risks. As the market develops, the concern of the central bank shifts primarily to managing the macro risk.

7.66 Against this backdrop, countries use both monetar y policy adjustments and outright

intervention in the form of sales/purchases of foreign exchange to influence exchange rate. The effectiveness of foreign exchange intervention crucially depends on whether the operation is sterilised or non-sterilised. Since sterilised interventions leave money supply unchanged, empirical research towards seeking to find a link between sterilised intervention and the exchange rates presents a mixed bag. Studies by Loopesko (1984), Obstfeld et al., (1983), Obstfeld (1988), Taya (1983) and Weber (1986) show no or weak evidence in favour of effectiveness of sterilised foreign exchange inter vention. On the other hand, Dominguez and Frenkel (1993) provide strong evidence towards working of sterilised intervention through portfolio balance channel. Recent findings by Fatum and Huchison (2003) also suggest that sterilised intervention is successful in influencing the exchange rate in the short-run.

7.67 An analysis of the complexities, challenges and vulnerabilities faced by the EMEs in the conduct of exchange rate policy reveals that the choice of a particular exchange rate regime alone cannot meet all the requirements. Nonetheless, ‘‘the debate on appropriate policies relating to foreign exchange markets has now converged around some generally accepted views: (i) exchange rates should be flexible and not fixed or pegged; (ii) countries should be able to intervene or manage exchange rates - to at least some degree - if movements are believed to be destablising in the short run; and (iii) reserves should at least be sufficient to take care of fluctuations in capital flows and liquidity at risk’’ (Jalan, 2003b).

7.68 In a similar vein, succinct observations made by Mohan (2003) on the exchange rate regime are noteworthy: ‘‘the experience with capital flows has important lessons for the choice of the exchange rate regime. The advocacy for corner solutions - a fixed peg a la the currency board without monetary policy independence or a freely floating exchange rate retaining discretionary conduct of monetary policy -is distinctly on the decline. The weight of experience seems to clearly be in favour of intermediate regimes with country-specific features, no targets for the level of the exchange rate, exchange market interventions to ensure orderly rate movements, and a combination of interest rates and exchange rate interventions to fight extreme market turbulence. In general, EMEs have accumulated massive foreign exchange reserves as a circuit-breaker for situations where unidirectional expectations become self-fulfilling. It is a combination of these strategies which will guide

ಪೇಜ್ ಕೊನೆಯದಾಗಿ ಅಪ್ಡೇಟ್ ಆದ ದಿನಾಂಕ: