IST,

IST,

Some Reflections on Micro Credit and How a Public Credit Registry Can Strengthen It

Dr. Viral V. Acharya, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India

delivered-on ಜನವರಿ 24, 2019

|

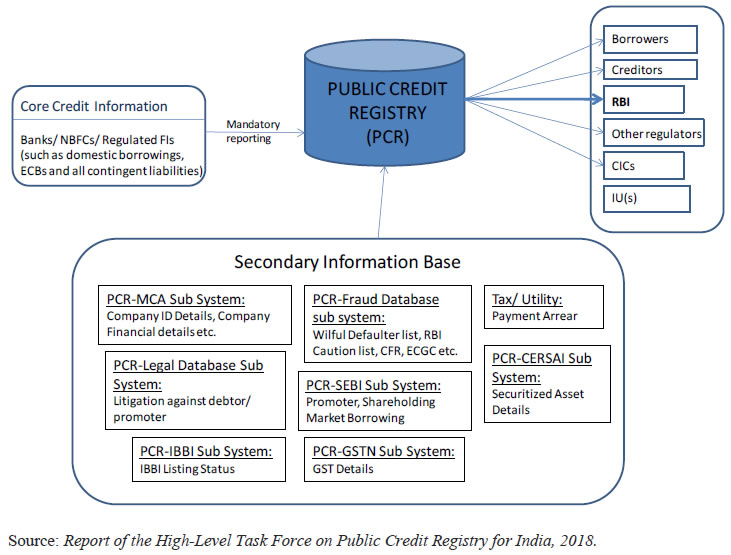

Sometimes when I sit down to write down a new set of remarks, the same old thoughts cross my mind, a bit like one’s favorite songs that are so deeply entrenched in the psyche that at the end of a long day when one is reflecting on the subject, they start playing all over again, without any reason and without any conscious decision to rewind to them. In my case, a few striking images flash across my eyes. I have tried in what follows to describe these images and what their collage means for me. They also convey how I try to think about economics and finance more generally – as the media to understand daily situations of households around us and to derive insights on how these situations could be made better, most often in some small ways and occasionally with a big bang… After all, the origin of the word ‘economics’ is in the ancient Greek term ‘oikonomía’, meaning ’management of a household’. Based on careful research, many [notably Professors Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)] contend, that it is the poor who often practice the best economics as the costs they face from mismanaging their households can be rather high. So let me describe these images that flash across my eyes one by one. Image One. Many evenings or nights when I stroll with my brother on our terrace in Mumbai, we are greeted on one side by the Pawan Hans Helipad, the sprawling slums of Nehru Nagar, the deafening din from the Swami Vivekananda Road (S V Road), and the serene breeze and waves of the Juhu Beach. I grew up on a crowded street in Girgaum, in south Mumbai. Observing from our first floor window how people went about their lives on the streets was a favorite pastime in our childhood days. Conditioned by that, while I’m on the terrace my eyes invariably end up focusing on the slums of Nehru Nagar. Far into the narrow alleys, bustling and jostling in high density are the slum-dwellers, appearing as diminutive figurines, with much activity and life all around. A man is fixing dish antenna on top of his blue roof; an old couple are perched outside a modest hut, savoring what must be some scrumptious desi chat; a woman slamming blow after blow on the clothes she has carefully aligned to wash; and almost always a group of children gleefully running around, mostly playing cricket and seasonally flying kites. Some of the evenings, a plane takes off from the domestic or international airport in the east and heads westward on its way; and a chopper swings in and lands at Pawan Hans with much acoustic fanfare. As these sophisticated means of modern transportation make their noisy presence felt, you can see the children bunch together, one of them pointing at the sky, others galvanising around him to marvel at the spectacle. An instant later of course, the children are nonchalantly back to gully cricket or running after a fallen kite. One cannot but hope that these children – in that brief moment of marvel – have been imbued with ambition; that their eyes are now set on the sky; that they will have the initiative and will get all opportunity to do what it takes to bridge the gap from their narrow alley to Pawan Hans Helipad next door and to the flight of the giant mechanical birds that fly above. Will these children take off? How will their journey be? Where will they land? I ponder for a few seconds but then switch attention to the incessant honking of the S V Road vehicles. Image Two. Until about ten years back, I used to spend a decent chunk of my time as a doctoral student, and later as a professor, working with an Indian NGO, focused on pre-primary and primary education. This activity had become my umbilical cord to India. On my holiday trips back home from New York or London, I would take out a few days to visit some of their baalwadis (daycares) in urban areas, and if travel plans permitted, also the delivery centers for accelerated reading programs in villages. These visits made my interactions with stakeholders more credible, engaging and vivid. But they were also personally rewarding. There are a few sights, if any, more uplifting than of a child figuring out the alphabet for the first time, reading the first book, flipping pages over and over again in boundless excitement and frenzy, or counting and adding up his or her collection of stones, subitizing them soon after – as in figuring out the exact count without counting, by merely glancing at the collection of treasures! It might be the innocent spark on the child’s face, or that “Aha!” or Eureka moment as the child discovers how to read, how to count, how to learn – whatever it is, it works like magic in bowling over the beholder. One returned from these visits with a shot in the arm to do more; one felt like nurturing the umbilical cord to India further; one realised that joyful learning is an essential groundwork for the journeys, the flights and the ascent that these children will undertake in due course. Image Three: I am usually en route in car to the office at RBI or Bombay Gymkhana during early mornings. I need to be on S V Road before turning for the Milan subway or now the flyover, which connects to the Western Express Highway. Just before the turn, before one reaches the Hanuman temple and Santacruz bus depot, on the left sidewalk, there is – always – a mother toiling away no matter what time of the day. It is clear she is homeless; she has at least two children, both roughly of the same age. Depending on the time of the morning, she has her work cut out. Some days she is waking up the kids with some sternness on her face; on others she is bathing them with water from an ingeniously figured out water-supply; at times she is getting them dressed in school uniforms; and then she is often running with the kids, who have their backpacks on, towards the neighborhood school. From a distance, she seems to be driven with a single-minded focus of ensuring that her kids get their chance to fly and soar. Her role as a mother certainly seems a mighty one, as Yudhisthir answered to the Yaksha Prashna in Mahabharata, when asked what is heavier than the Earth. How does the mother make it all work? Can she afford the books and the supplies? Is she home when the kids come back? What job does she do during the day? Could she be a micro entrepreneur? The mind is so fickle, however; as soon as the car turns left at the traffic signal and moves onto the flyover, it leaves these questions in background and embarks on its daily descent. Image Four: Early on a Saturday morning, already quite bright and sunny, a banker carrying his thela (a shoulder bag) steps into the passageway next to a series of kachcha-pukka homes. The surrounding is semi-urban. By the time you have blinked an eye, an army of about twenty women, mostly in saris, of ages spanning from 20 to 50, and a few even 50-plus, have gathered around him. They have all borrowed certain sums of money from the banker. They make their repayments one by one; each transaction is logged in a physical register; it is also swiped digitally onto their bank cards with a point-of-sale or POS-style machine. Some of the women are borrowing again; some taking out monies from their accounts. The registrar of this group of women, appointed for the month, signs off the log after checking the account entries carefully. Banking is now done. Growth is about to begin. I am curious to hear more about what these women are doing with the money. All of them, without exception, are entrepreneurs. One has started a sari trading business, buying them from the city and selling them in the neighborhood with a margin; she has built her enterprise over several years and is the recipient of the biggest loan (one lakh rupees) with the longest maturity (one year) in the group; her friend has acquired a sewing machine with the loan and is stitching blouses to go with the saris; another has opened a beauty parlor; yet another has started a soft-drinks stall in her husband’s stationery store as there is extra, unused space therein, well utilised especially during the afternoons when customer traffic is thin for stationery but the heat unbearable. There seemed absolutely no shortage of services to be provided in their immediate sphere of influence. I was especially eager to know what prompted these women to become entrepreneurs in the first place. The answer I got was not entirely expected: in nine out of ten cases, women had become entrepreneurs to send their kids to a ‘top, English medium school’, or to have extra monies for private coaching so the child could excel in the state-level exams, or to get the kid to learn some computing and programming as that is where future jobs lie! Collage of the Images As these images flashed across my eyes, I realised that rather than being entirely compartmentalised, these images were all linked, that there was a connection between finance – my day job, and these images that my mind had been subconsciously gathering in mornings, evenings and during holidays. An important link was established from financial inclusion to education of children – from micro finance for women entrepreneurs to them sending children to schools, the children in turn having their “Aha! I did it!!” moments in reading and counting, and to their taking off for the limitless sky and beyond. Access to finance is the lifeblood of an economy. Its judicious allocation is known to unlock opportunity and growth. It can, in fact, aid even the most fundamental reform for growth by supporting, directly or indirectly, the education of our children, the skilling of our youth, and lighting up of their minds with fire and imagination so they can propel themselves, their families, and the rest of us, forward. Education is perceived by many families as ticket to the ride that will catapult them out of economic stress. Leaving aside minor exceptions, as a rule education is indeed a ticket to such ride. A mother taking up an enterprise to shape her child’s future has all the willingness to pay her debt. As the child grows, her needs too will rise. She will need a clean credit record to be able to borrow again so as to finance her now bigger liquidity requirements. This way, there is full incentive compatibility between her and the finance provider. Besides her willingness to pay, the deft handling of her enterprise, induced by the necessity to keep buying the education ticket over time, will strengthen her ability to pay. At any rate, the financier can start with a small loan, use a short tenor to assess repayment ability, and open for her a bank account that can help track other payment flows and improve credit assessment. The reputation of the woman entrepreneur as a borrower can build swiftly as she keeps repaying and enable her to secure more credit over longer tenors. Borrowing as part of a group reinforces the strong incentives to repay; default by a borrower when all others are repaying can lead to stigma. Conversely, encouraging of defaults by some can lead to vitiation of the otherwise rich credit culture. The financier, in turn, can make a healthy spread over own cost of borrowing funds, even accounting for some losses from early defaults, upon whose realisation the entrepreneur can be rationed from future loans or offered only stricter loan terms and tenor. This way, the availability of micro finance for micro entrepreneurs thrives and benefits the society all around.2 So let me turn from these images to my day job at the RBI and what efforts we are undertaking to help ensure that micro credit becomes available to more borrowers; micro finance provided a robust foundation; micro enterprise given an additional fillip; and indirectly, in the process, our children offered greater opportunity for schooling and skilling. Public Credit Registry (PCR) – An Important Step to Democratise and Formalise Credit3 In an emerging economy like India, it is always felt that the smaller entrepreneurs, mostly operating under the informal economy, do not get enough credit as they are informationally opaque to their lenders who prefer to provide loans to more transparent larger businesses. Data as of March 2018 of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) from RBI’s basic statistical returns (BSR) shows that close to half of the outstanding credit is for ticket size above a hundred million rupees and thirty per cent is above one billion rupees. Credit penetration is particularly low for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) sector where the ticket size is generally believed to be between one to ten million rupees. Even though more than 95 per cent of accounts with SCBs are having sanctioned credit limit less than one million each, the amount outstanding on these accounts is only 23 per cent of the total. Is there a big opportunity for us to rethink and reshape our credit eco-system for the future so that micro credit can thrive to unlock economic value, as I laid out in my collage of images? At the RBI, we firmly believe so. We have initiated work on a Public Credit Registry (PCR). We are excited about how we can solve in a fundamental way the information problem affecting access to credit for micro entrepreneurs. Let me elaborate on the information problem and how a PCR can help get around it. Information asymmetry with the borrower is the major difficulty faced by any lender while granting a loan. Put simply, the borrower has more information about her own economic condition and risks than the lender. Credit information systems aim to reduce this asymmetry by enabling the lender to know the credit history with past lenders and the current indebtedness of the borrower. They improve efficiency of credit allocation, as the lender can use credit information systems to properly differentiate and appropriately price (interest rate) as well as alter terms (maturity, collateral, covenants, etc.) of the loan. What would occur without the credit information systems? As borrowers build history, lenders would like to protect the information of their profitable customers and may not be ready to share it directly with other lenders. This way, borrowers can get locked to their initial lenders, become vulnerable to gouging in loan terms, and worse, be unable to convey their credit quality to new lenders if existing lenders experience problems of their own (such as due to capital erosion from recognition of losses, as was witnessed in India over the past decade in the form of high retail and MSME cost of borrowing from banks due to spillover from their large corporate borrower loans turning non-performing). This is where third-party credit information companies come in to play, those that will pool the data from lenders and share the information with other lenders as per the laid down policy. Globally, Private Credit Bureaus (PCBs) and Public Credit Registries (PCRs) both operate in this space. PCBs can be legislatively authorised to receive credit data; however, being for-profit enterprises, they may focus primarily on those data segments around which it is most profitable to build a business model (e.g., provision of credit scores based on data gathered). Indeed, it is found internationally that a PCR, being a non-profit enterprise, is able to ensure much better data coverage than PCBs. In turn, the PCBs when given access to comprehensive data from a PCR can provide better and greater value addition through data analytics and innovations, complementing the PCR. One can easily surmise that to be useful, it is important for credit information systems to gather complete credit information, possibly even asset-side and cash-flow details about the borrower, which is sometimes referred to as the ’360-degree view’. Also, the latest information is more important, giving rise to the demand for near-real-time data. That is how the Report of the High-Level Task Force (HTF) on Public Credit Registry for India, chaired by Shri Y.M. Deosthalee, has envisaged the Public Credit Registry (PCR) to be. The HTF examined the data gaps in the current credit information system in India and recommended that a PCR be set up, backed by an appropriate Act, to improve the information efficiency of the credit market and strengthen the credit culture in India. How will the Public Credit Registry (PCR) for India work? The PCR has been envisaged as a database of core credit information – an infrastructure of sorts on which users of credit data can build further analytics. It will strive to cover all regulated entities (i.e., financiers) in phases and in this way get a 360-degree view of borrowers. It will facilitate linkages with related ancillary information systems outside the banking system including corporate filings, tax systems (including the Goods and Services Network or GSTN), and utility payments. The PCR will have to be backed and governed by a comprehensive Public Credit Registry Act to be brought in consultation with the Government. It will have to follow the latest privacy guidelines based on a laid down consent framework. The proposed Public Credit Registry (PCR) information architecture  Let me now spend some time on how the PCR will work and help strengthen the credit culture. (1) First, PCR will make borrower information more complete with increasing coverage of lending entities. In particular, it will eventually reach out even to the smallest primary agricultural credit societies. It will also cover entities which may not be regulated by the RBI. This will have to be done in phases and it may take up to three to five years to accomplish, possibly sooner. (2) Secondly, PCR will vastly simplify and reduce the reporting burdens on the lenders. Other entities including regulators and supervisors will be able to access it for core credit information and supplement it with only the incremental part as per their requirement. Many of the statistical returns presently collected by the RBI may also accordingly be substantially rationalised and pruned, freeing up resources in the financial eco-system for analysis instead of repetitious efforts in data collection, follow-up and cleaning. The same would be the case with other entities that presently collect such data from banks. (3) Thirdly, PCR will have credit data available digitally at a higher frequency than at present. Therefore, it will make credit decision-making faster and efficient. (4) Fourthly, as the chart here shows, with linkages to other information systems like corporate data from the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA21) and tax filing or invoicing data (GSTN), it will help the users to access other data on borrowers’ assets and evolving cash flows, which are essential for taking efficient credit decisions. (5) Finally, it will be possible within the PCR architecture to address privacy concerns and control access to data with a proper consent-based framework for appropriate usage, better than what is currently feasible. These concerns will have to balance the objective that the PCR is just a step in helping the democratisation of credit, whereby credit data is not only used for regulatory / supervisory purposes, but also leveraged to expand the credit market efficiently. In particular,

To appropriately put in place the required access and control policies, the High-Level Task Force recommended that a separate Public Credit Registry Act (PCR Act) be brought in. The PCR Act will need to ensure adequate safeguards on data while at the same time address extant restrictions on sharing of credit data that prevent efficient allocation and regulatory supervision of credit. The PCR Act would also have to be comprehensive so as to bring in data from the section of lenders who do not directly fall under the RBI regulations. To this end, the RBI plans to engage with the Government and other regulators in the coming months. In the meantime, the RBI has set up an Implementation Task Force that is putting the systems infrastructure in place to kick-start the PCR with data from regulated entities that can be covered either under, or with minor tweaking, of the extant legislative framework. Public Credit Registry can help “sachetise” Micro Credit To build credit models for individuals and small credits, the financier and its modelers are ideally required to know not just outstanding credit for the micro borrowers, but possibly also their entire repayment history and their cash flow fluctuations, so as to tailor the terms of credit suitably. In the absence of such information, many borrowers may simply get ’rationed’ out of the market due to severe information asymmetry faced by financiers. With a PCR tracking every credit transaction from its origination to closure (initial terms, repayment, default, restructuring, etc.), and being linked to various digital systems in place (as shown in the chart above), it would be possible to identify and get to know well businesses, even micro enterprises and micro entrepreneurs. In other words, the PCR could supply the missing link, which is the complete ‘360-degree view’- information of the borrower or prospective borrower. This will allow lenders to assess the borrower’s credit risk keeping in view the viability of cash flows, ask the relevant questions (e.g., are there other underlying issues that are affecting ability to pay the loan in spite of healthy cash flows from the micro enterprise?), and price the loan terms without compromising on due diligence. Based on these, nearly-automated loan sanction and disbursement mechanisms can be devised, as are also being attempted by fin-tech companies. In fact, credit products could get transformed with the possibility of sanctioning small ticket loans with short maturity and zero or low collateral requirement. Borrowers and entrepreneurs can build their reputation and credit quality by repaying well such initial information-building loans. Gradually, they can borrow more and at longer maturities, potentially making capital investments to enhance productivity. Once their size increases and they register with the GSTN, tax invoices can act as the cash-flow verification with PCR. Robust credit history built over a period can work as sturdy collateral, building the trust of the lenders. Such ’sachetisation’ of credit can rapidly expand access to credit for those micro and small enterprises, hitherto not included in the formal credit market. As I stressed while describing the ability to pay and willingness to pay of micro entrepreneurs, it would remain important not to undermine their inherently strong credit culture by making it easier for borrowers not to repay. That would compromise the essence of how micro entrepreneurs build a reputable credit history to differentiate from others and over time grow in size and economic value creation. Let me conclude. There is a deep connect between the images I started with, their collage in my mind, and my day job at the RBI. Ultimately, while central banks are not always visible to the common person, their policies have the potential to touch her in a meaningful way. As its etymology suggests, this is what economics must help achieve in the end – better management of the household. It is perhaps too ambitious a vision of our future to believe that a fundamental change in the financial data infrastructure such as a Public Credit Registry can help improve access to micro credit as well as improve schooling and skilling outcomes for our children and youth, but so be it. My son’s poster at his school last year introduced me to a gem from Michaelangelo, which underscores why we must keep painting such a vision and persist with efforts to convert it into reality. It says, “The greatest danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark.” 1 I dedicate these remarks to my favorite school teacher, Shailesh Shah Sir, of Fellowship School in Mumbai, who breathed his last on the morning of January 5, 2019; he taught me Indian languages, social sciences, and the art of compositional writing; he truly lit all his students with ambition and set us on fire with imagination. Parts of these remarks were first prepared in 2017 for a book launch, followed by delivery at several student gatherings and a few convocations. This final version represents the accumulation of my observations at these talks, which culminated at Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IITB) Tech Fest on December 15, 2018. I am grateful to Anujit Mitra, Jose Kattoor and Vineet Srivastava for their valuable inputs. 2 At some of the student gatherings and convocations, I ended the remarks here by reciting a poem I received from Yuvaraj Galada on December 22, 2017, called ‘The Invitation’, written in 1999 by Oriah Mountain Dreamer, that has inspired me immensely. 3 For a fuller treatment of this theme, please see my speech “Public Credit Registry (PCR) and Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN): Giant Strides to Democratise and Formalise Credit in India”, delivered in August 2018. |

ಪೇಜ್ ಕೊನೆಯದಾಗಿ ಅಪ್ಡೇಟ್ ಆದ ದಿನಾಂಕ: