IST,

IST,

Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Indian Economy

Shri Deepak Mohanty, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India

delivered-on ಜುಲೈ 24, 2014

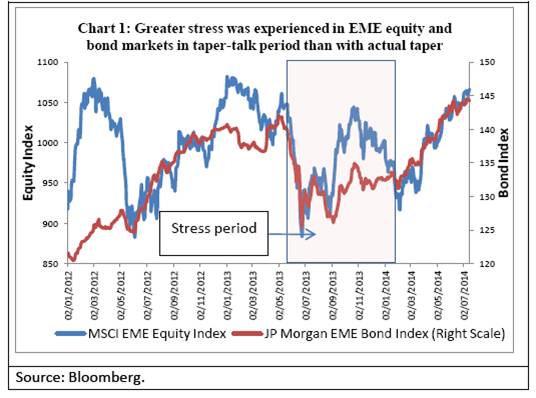

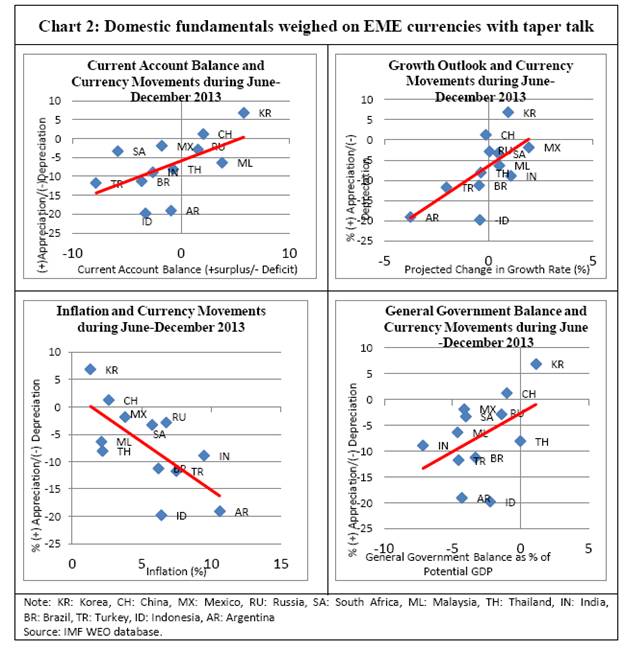

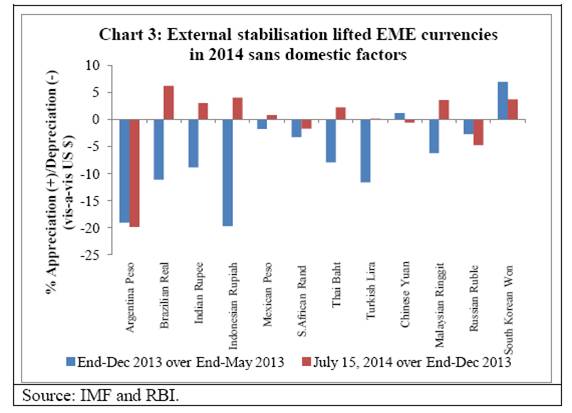

I thank Governor Cabraal for this opportunity to share with you our experience in handling the spillover from unconventional monetary policy being followed by many advanced economies. Conventionally, central banks operate monetary policy with an interest rate instrument. For example, they raise the policy interest rate to signal a tighter monetary policy and vice versa. However, this procedure has limits. In abnormal times, if central banks were to sharply loosen their monetary policy, they cannot go beyond a point as the nominal policy interest rate cannot be lowered below zero. We saw this phenomenon play out in full force following the global financial crisis in 2008. As the zero lower bound began to constrain conventional monetary policy of major central banks, they had to deploy unconventional monetary policy measures to provide further monetary accommodation. Unconventional monetary policy essentially relates to the balance sheet policy of central banks. However, entry and exit from such policies have strong externalities and spillovers as we have been experiencing for some time now. Against this backdrop, I will begin by discussing the broad contours of unconventional monetary policy and possible channels of cross-border spillovers. I will then focus on India’s experience after the first announcement on early quantitative easing (QE) tapering in May 2013 and our response. I will end by drawing a few broad conclusions. Unconventional Monetary Policy The limitation of transmission of conventional monetary policy through interest rate led major central banks to undertake measures which were monetary in nature but unconventional in their instruments and operational targets. For example, a crisis may impair the normal functioning of financial markets. In such a situation, central banks can resort to direct financial asset purchases and/or loosen collateral standards to expand their balance sheets. In the recent global financial crisis most advanced country central banks resorted to unconventional monetary policy. Although the design of unconventional monetary policy measures varied across central banks, they included lending to financial institutions, targeted liquidity provisions for credit markets, outright purchases of public and private assets, purchase of government bonds and forward guidance (Annex 1). These measures were aimed at lowering longer-term bond rates and ease monetary conditions, and were intended to signal a policy shift towards maintaining interest rates at lower levels for a longer period. Spillovers to EMEs It is widely perceived that in absence of unconventional monetary policy measures, financial sector meltdown and recession, particularly in advanced economies, would have been more severe, which in turn could have significantly impacted the global economy.1 However, opinion remains divided on the efficacy of prolonged recourse to unconventional monetary policy. It is argued that greater risk taking behaviour as an outcome of unconventional measures could undermine financial stability. Furthermore, there is the risk of postponement of necessary fiscal reforms that were otherwise required. More importantly, there are concerns of cross-border spillovers in terms of capital flows, exchange rates and other asset prices, particularly in emerging market economies (EMEs). This was fully in evidence as the Fed communicated its intention of undertaking tapering earlier than anticipated which increased financial vulnerabilities across EMEs, though subsequent communication somewhat eased the pressure. These policy developments, however, have significantly altered the external financial environment in many EMEs, including India. Even before the tapering talk, the impact of policy changes in systemically important advanced economies on the rest of the world through various channels was in evidence. Unconventional monetary policy measures not only supported domestic economies, but also boosted a broad range of asset prices globally, especially equity and bond markets in EMEs. In fact, recent literature suggests that besides domestic pull factors in EMEs, push factors - monetary policy in advanced economies and global risk appetite - were important determinants of capital flows to EMEs.2 While the presence of cross-border spillovers from policy changes/ announcements in advanced economies is well recorded in the literature, the more recent debate has been on the degree and kind of spillovers across EMEs and how these could be minimised. Governor Rajan argued that capital flows pushed into EMEs due to ultra-accommodative monetary policy in source countries tend to increase local leverage not only through cross-border banking flows but also through appreciating domestic currencies and escalation in asset prices. The exit from a prolonged use of unconventional monetary policy also poses the risk of asset prices overshooting on the downside which can cause significant collateral damage.3 According to the IMF, EMEs received much larger net private financial flows of about US$ 3.0 trillion in the form of direct and portfolio investment during 2009-13 as compared with US$ 1.8 trillion during 2004-08.4 With indications of likely normalisation of monetary policy in the US, concerns regarding potential outflows were expected. As long-term US interest rates rose immediately after the tapering announcement, risk aversion among foreign investors for EME markets escalated. Capital flight from the bond segment of financial markets weakened currencies in EMEs, which in turn triggered equity sell-offs. This suggests that despite the fact that equity and debt are two different classes driven largely by growth premium and yield differentials, both were affected by shifts in broad sentiment towards EMEs (Chart 1). The multilateral institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), have done significant research on the issue of spillover. Most studies found that EMEs with better domestic fundamentals and deeper financial markets were relatively more resilient to adverse shocks from US Fed tapering.5 There was also a view that foreign investors did not differentiate EMEs based on macro fundamentals. Rather the EMEs with larger and deeper markets were under more pressure.6 On balance, it would seem that most EME currencies depreciated and countries with weaker fundamentals were affected more (Chart 2). Keeping in view the complex interaction of global spillovers and domestic vulnerabilities, EMEs deployed a variety of policy measures. These policy responses were in the form of monetary, capital flow measures and other structural policy actions. For example, while Indonesia and Turkey made greater use of their forex reserves to curb downward pressures in their currencies, others like South Africa used exchange rate as the main shock absorber. Many EMEs had to raise policy rates to curb capital reversals and contain downward pressure on exchange rates (e.g., Turkey, Brazil, South Africa and India). Subsequently, greater clarity on tapering from the Fed coupled with domestic policy action helped EMEs gradually stabilise their markets. Since January 2014, market conditions in EMEs have improved and most of the EME currencies have appreciated albeit with some exceptions. This may suggest that since the actual tapering phase, pull factors were more dominant as evident from increasing investors’ discrimination across countries (Chart 3). Impact on India Let me briefly give you a background of our domestic macroeconomic conditions before discussing the impact of the recent tapering announcement. Until the emergence of the global crisis in 2008, India had witnessed a phase of high growth along with low and stable inflation. Growth was largely supported by domestic demand emanating from growing domestic investment financed mostly by domestic savings and sustained consumption demand. Better macroeconomic performance was also attributed to sequential financial sector reforms, move towards a rule-based fiscal policy and forward-looking monetary policy.7 During the initial phase of the crisis, Indian financial markets remained relatively insulated from global developments due to negligible exposure to illiquid securitised assets. The impact on broader financial markets, however, was severe after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. Consequently, India could not remain unscathed for long and was eventually impacted significantly through all the channels – financial, real and more importantly, the confidence channel. Taking cognizance of deteriorating economic and financial conditions, the Reserve Bank, like most other central banks, took a number of conventional and unconventional policy measures to contain the adverse spillover of global developments. These included augmenting domestic and foreign exchange liquidity and a sharp reduction in the policy rate. The Government also supported the economy by fiscal stimulus packages, reversing the earlier efforts at fiscal consolidation. Supported by substantial monetary and fiscal stimulus, the domestic economy recovered quickly. In the process though, inflation also picked up, partly aggravated by spurt in global commodity prices, particularly oil (Table 1). Consequently, the Reserve Bank shifted policy focus to exit from accommodative monetary policy in a calibrated manner. Fiscal policy was also tightened. At the same time the economy was confronted with a number of supply constraints. In this process growth slowed, inflation still remained at levels not conducive to sustained high growth and current account deficit expanded which made the Indian rupee more vulnerable to external shocks.

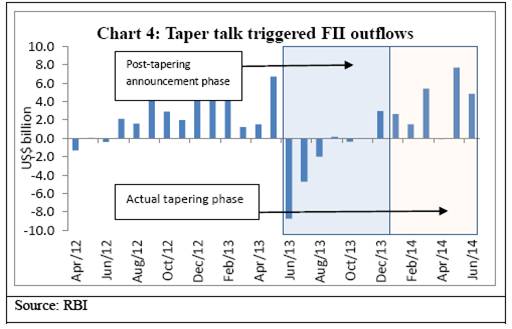

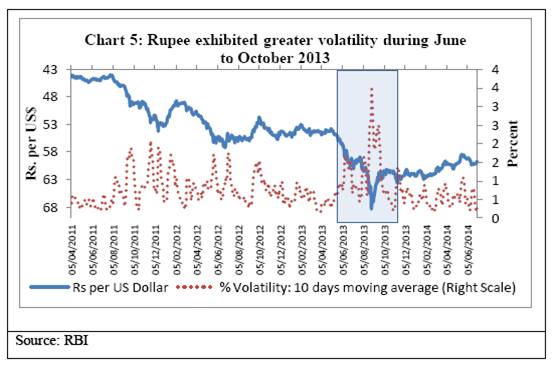

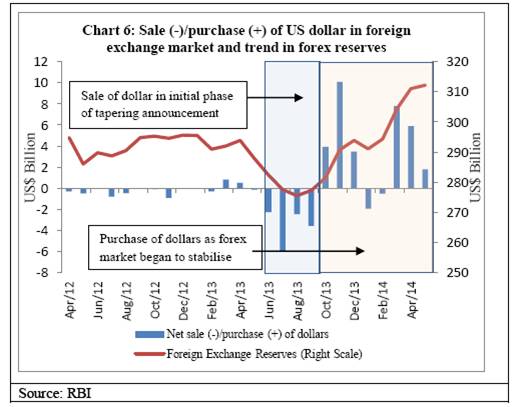

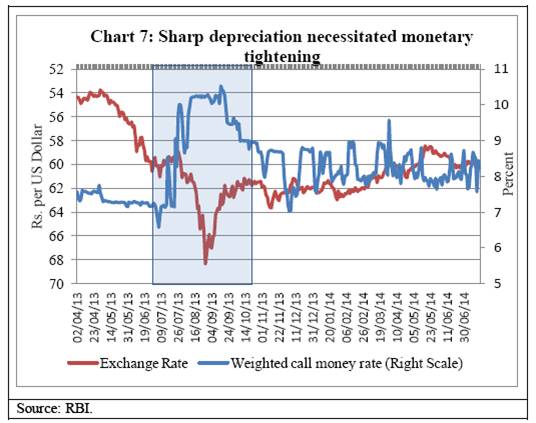

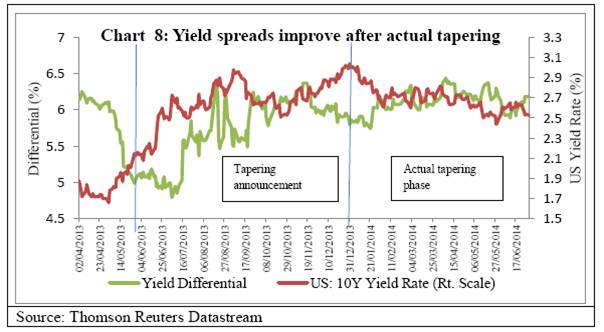

In the financial year 2012-13, growth had slowed to its lowest level since 2003-04 at 4.5 per cent, current account deficit (CAD) had expanded to its highest level at 4.7 per cent of GDP, gross fiscal deficit of the central government was 4.9 per cent of GDP and consumer price inflation remained in double digits. Hence, macroeconomic conditions were weak. Into the financial year 2013-14, volatility in the financial markets returned following the announcement in May 2013 of the Fed’s intention of likely tapering of QE. The impact of announcement of tapering was evident in the form of tightening of liquidity and higher volatility in all market segments along with sharp decline in stock prices. Portfolio capital inflows which were buoyant till the third week of May 2013 began retreating as US yield rates hardened and yield spread narrowed significantly (Chart 4). At the time when the tapering was announced, domestic concerns pertaining to high CAD, low growth, high fiscal deficit, high inflation and policy uncertainty were already major concerns for foreign investors. This apparently amplified the impact of tapering announcement on foreign flows to India which in turn caused downward pressure on the Indian rupee. The rupee which was hovering around Rs.55 per US dollar in March 2013 depreciated by about 20 per cent and touched a low of ` 68.4 per US dollar as on August 28, 2013. However, with proactive measures by the Government and the Reserve Bank, the rupee recovered significantly by November 2013 and turned less volatile (Chart 5). Let me now turn to the specifics of our policy response. Policy Response during taper talk phase Taking into account the spillovers of global developments on Indian markets, the Reserve Bank the Government announced various policy measures since June 2013. The policies can be broadly categorized into: (i) currency intervention, (ii) monetary policy, (iii) trade policy and (iv) capital flow management measures. A chronology of policy measures is given in Annex II. Currency intervention and monetary policy In order to stabilize the domestic currency market, the Reserve Bank intervened in the forex market by selling dollars during June to September 2013 (Chart 6). As the downward pressure on rupee continued despite the initial rounds of intervention in forex market, monetary tightening measures were undertaken to stem speculation by making it expensive to build up long positions in dollars. Accordingly, the upper bound of the policy rate corridor (i.e., MSF rate) was raised by 200 basis points and the quantity of central bank liquidity available through the RBI’s overnight liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) window was restrained. In addition, the level of daily average maintenance of required cash reserve ratio (CRR) was raised. These had the desired effect of tightening the monetary conditions and raising the effective policy rate sharply to the MSF rate (Chart 7). In order to signal the transitory nature of these measures and avoid hardening of interest rates at the longer end, a form of operation twist was tried by conducting outright OMO purchase of government securities alongside sale of short-term government cash management bills. This inverted the yield curve, though accompanied by some increase in long-term rates. Simultaneously, steps were taken to augment foreign exchange reserves. In this regard, banks were incentivized to mobilize fresh non-resident foreign currency [FCNR(B)] deposits and swap those directly with the Reserve Bank. The overseas borrowing limit of banks was also increased from 50 to 100 per cent of their unimpaired Tier I capital with the option of swap with the Reserve Bank. Under this scheme, the banks mobilized US$ 34.3 billion and swapped with the Reserve Bank. This helped in bolstering foreign exchange reserves despite some outflow on account of directly meeting the foreign exchange requirement of oil imports.Trade policy The single largest component of imports is oil which accounts for nearly one-third of total imports. The Reserve Bank opened a forex swap window to meet the entire daily dollar requirements of three public sector oil marketing companies (IOC, HPCL and BPCL). Under the swap facility, the Reserve Bank undertook to sell/buy USD-INR forex swaps for fixed tenor with the oil marketing companies. Recognising that high gold imports were a key source of stress in India’s external sector, customs duty on gold imports was raised and importers were required to set aside at least 20 per cent of their gold import for exports. These measures helped in moderating gold imports from 1,014 tonnes in 2012-13 to 666 tonnes in 2013-14. As international gold prices also moderated significantly, the decline in imports from US $ 54 billion in 2012-13 to US$ 29 billion in 2013-14 was substantial which helped to bring down CAD within a sustainable range. Capital flow management The limit on foreign investment in government dated securities was enhanced to US$ 30 billion. Public sector financial institutions were allowed to raise quasi-sovereign bonds to finance long term infrastructure requirements. PSU oil companies were allowed to raise additional funds through ECBs and trade finance. FDI norms were modified for a number of sectors. For instance, FDI limit was raised from 74 per cent to 100 per cent in telecom sector and asset reconstruction companies. The extant FDI limits in sectors such as petroleum and natural gas, courier services, commodity exchanges, infrastructure companies in the securities market and power exchanges were placed under automatic route. Besides these, the Reserve Bank restricted banks to trade only on behalf of their clients in currency futures/options markets, tightened of exposure norms, and raised margins on currency derivatives to check speculative activities; reduced thelimit for overseas direct investment (ODI) under automatic route; and lowered the limit on remittances by resident individuals under the Liberalised Remittance Scheme (LRS). Unwinding of temporary measures As portfolio capital outflows waned and the balance of payments (BoP) situation improved significantly, stability returned to the foreign exchange market in the second half of 2013-14. This prompted the Reserve Bank to withdraw many exceptional measures. Swap scheme for fresh FCNR(B) deposits and overseas borrowings of banks were closed, the forex swap facility for public sector oil companies was phased out, the interest rate ceiling on foreign currency deposits were reverted to its earlier level, and the limit for overseas direct investment under automatic route was restored. Monetary policy was also normalised by restoring the policy interest rate corridor to its original position and the repo rate to its signalling role of policy. Though the policy repo rate was increased by 25 basis points each in September 2013, October 2013 and January 2014, this was more on considerations of growth and inflation outlook. Actual tapering When the Fed started actual tapering in January 2014 by gradually reducing its volume of asset purchases,8 the impact on most EMEs, including India, was relatively muted. There could be two broad explanations. First, after the initial shock global financial markets may have better internalised taper and inferred that despite QE withdrawal monetary conditions still remain and are likely to remain accommodative in the advanced countries. This is reflected in easing of US bond yields since the actual tapering in January 2014 (Chart 8). Further, the European Central Bank’s indication to keep interest rate lower to spur economic activity has also added to market comfort. Consequently, the downtrend in yield rates in US bond market have led investors again to embrace EME equity and bond markets in search of higher yields. Second, various policy measures helped improve domestic fundamentals. For instance, with sharp reduction in CAD, external financing requirement has reduced, resulting in accretion to foreign exchange reserves thus improving various external sector vulnerability indicators (Table 2). The Reserve Bank’s commitment to a monetary framework focused on inflation coupled with adoption of consumer price inflation as the nominal anchor and the Government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation may also have helped in mitigating macroeconomic concerns of foreign investors. Further, with a stable central government in place, political risk has also abated. Nevertheless, headwinds to growth from domestic constraints continue to pose downside risks, and vulnerabilities in India’s external sector, though mitigated, have not totally disappeared.

Conclusion Let me conclude. First, the stance of monetary policy in advanced economies has spillover effects on EMEs. This is now increasingly recognised in academic literature and acknowledged by international institutions such as the IMF and BIS. One of the key channels of transmission of vulnerability seems to be through accentuation of cyclicality in global capital flows. In an upswing while there is an upward pressure on asset prices and exchange rate, in a downswing the downward pressure on exchange rate could be quite severe. This is not to deny that relatively open capital accounts have their benefits but one has to be cognisant of risks which could arise essentially from exogenous events. Second, while spillover is unavoidable, domestic fundamentals are important to cushion its adverse impact, particularly for countries with greater external financing requirement as reflected in their current account deficits. It will, therefore, be desirable to contain the CAD around its sustainable level. For example, our average CAD of around 4.5 per cent of GDP during the two year period 2011-13 was far in excess of our estimated sustainable level of around 2.5 per cent of GDP. Hence, we were more vulnerable to external shocks. Since then, our CAD has improved to 1.7 per cent of GDP in 2013-14 imparting greater resilience to our external sector. Third, in the event of sudden capital outflow as happened towards end-May 2013, domestic foreign exchange reserves become the first line of defence to contain volatility without resisting depreciation pressure. It is therefore important to have adequate reserves. It is, however, difficult to say how much of reserves is adequate. For example, India’s foreign exchange reserves stood at US$ 292 billion in mid-May 2013, even that level was perhaps considered inadequate by international investors and markets. Fourth, capital outflows in a way reflect an imbalance in terms of surge in demand for foreign currency vis-à-vis domestic currency. Hence, the price of domestic currency needs to go up to provide some defence against capital outflows, though it may have adverse impact on growth. Accordingly, monetary tightening becomes a standard response. Fifth, in the event of a shock, external stability takes precedence over domestic objectives. In such situations, there is no single instrument to address the challenge. Drawing from the recent Indian experience, I could say that there is a need to use multiple instruments including drawdown of foreign exchange reserves, monetary tightening, augmentation of reserves and administrative measures to dampen speculative outflows and encourage inflows to stabilise market conditions. At the end it is difficult to say what worked and what did not work and how best to sequence these policies; but surely once the pressure abates it is important to reverse extraordinary measures to reinforce market confidence. Thank you. Annex I: Unconventional Monetary Policy During the Crisis

Annex II: A Chronology of Major Policy Measures during June to September 2013

* Paper presented by Deepak Mohanty, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India, in the SAARCFINANCE Governors’ Symposium at Colombo, Sri Lanka, on 24th July 2014. The assistance provided by Rajeev Jain in preparation of this paper is acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are personal and not necessarily that of the Reserve Bank of India. 1 IMF (2013), Global Impact and Challenges of Unconventional Monetary Policies, IMF Policy Paper, October. 2 Fratzscher, M., LoDuca, M., & Straub, R. (2013), “On the International Spillovers of US Quantitative Easing”, Discussion Papers 1304, German Institute for Economic Research. Lim, J., Mohapatra, S., & Stocker, M. (2014), “The Effect of Quantitative Easing on Financial Flows to Developing Countries”, Global Economic Prospects H1, World Bank. 3 Rajan, Raghuram G. (2014), “Competitive Monetary Easing: Is it yesterday once more?”, Remarks at the Brookings Institution, April 10. 4 International Monetary Fund (2014), World Economic Outlook Database, April. 5 Mishra, Prachi; Kenji Moriyama ; Papa M'B. P. N'Diaye ; Lam Nguyen (2014), “Impact of Fed Tapering Announcements on Emerging Markets”, IMF Working Paper No. 14/109. 6 Eichengreen, Barry and Gupta, Poonam (2014), “Tapering talk: the impact of expectations of reduced Federal Reserve security purchases on emerging markets," Policy Research Working Paper Series 6754, World Bank. Aizenman, Joshua; Mahir Binici and Michael M. Hutchison (2014), “The Transmission of Federal Reserve Tapering News to Emerging Financial Markets”, NBER Working Paper No. 19980, March. 7 Mohanty, Deepak (2014), Unconventional Monetary Policy: The Indian Experience with Crisis Response and Policy Exit”, RBI Bulletin, Vol. LXVIII No.1, January. 8 Beginning in July 2014 (fifth round of tapering), the Fed will add to its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of US$15 billion per month rather than US$20 billion per month, and will add to its holdings of longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of US$20 billion per month rather than US$25 billion per month. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ಪೇಜ್ ಕೊನೆಯದಾಗಿ ಅಪ್ಡೇಟ್ ಆದ ದಿನಾಂಕ: