IST,

IST,

Price Stickiness in CPI and its Sensitivity to Demand Shocks in India

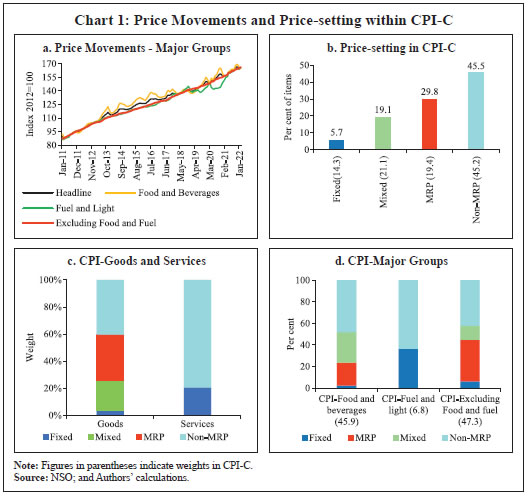

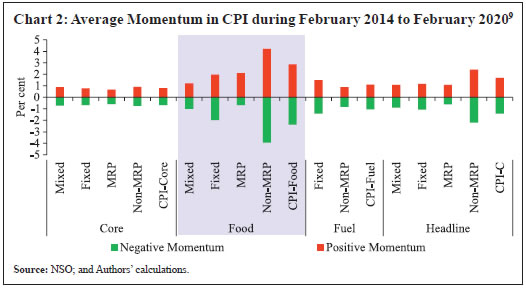

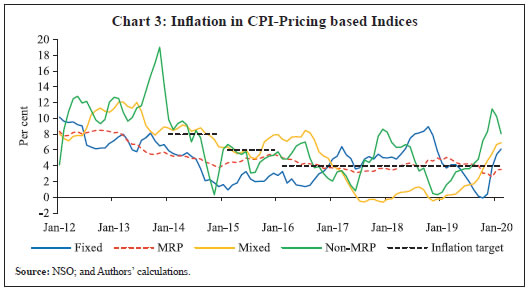

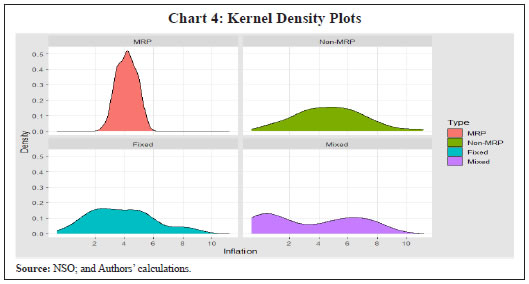

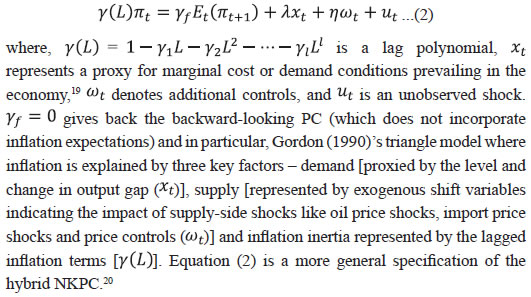

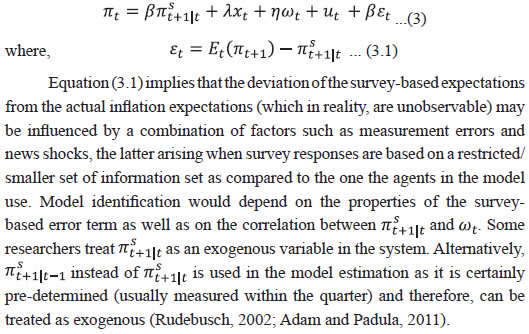

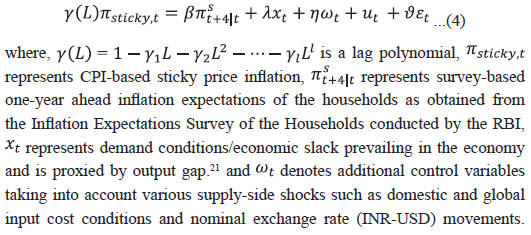

Sujata Kundu, Himani Shekhar and Vimal Kishore* Received on: April 20, 2022 This study analyses the Consumer Price Index-Combined (CPI-C) data at a disaggregated level by identifying different price-setting methods, viz., maximum retail price (MRP), non-MRP, mixed (both MRP and Non-MRP based items) and fixed (items with administered prices). Based on their price dynamics, it constructs a Sticky Price Index and a Flexible Price Index and finds that the headline inflation is primarily driven by flexible price inflation, while inflation excluding food and fuel largely co-moves with sticky price inflation. The study then analyses the underlying relationship between the sticky price index and output gap in a New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC) framework using data from 2011:Q1-2019:Q4 and compares the results with the Phillips Curve (PC) estimates based on headline CPI-C and the flexible price PC. The results indicate that the sticky price PC is much flatter and the impact of output gap on inflation occurs with a significant lag, suggesting that the sticky price index is less sensitive and slow to adjust to changes in economic slack. JEL: E3, E31, C38 Keywords: Flexible Price Index, Inflation, K-means Clustering, New Keynesian Phillips Curve, Phillips Curve, Sticky Price Index. Introduction The effectiveness of monetary policy in achieving its ultimate goals hinges on the price-setting behaviour of economic agents. When prices are fully flexible a tightening of monetary policy reduces inflation, but without any effect on output or other real variables. For monetary policy to generate any real output effects, prices must be sticky. In new Keynesian models, monetary policy can become non-neutral because of the widely observed sticky behaviour of price movement (Gali, 2010). Price stickiness, thus, creates scope for monetary policy to pursue the goals of output and employment. It has been found that the output responses of different industries systematically vary depending on the extent to which their prices remain sticky (Henkel, 2020). Not only that, the heterogeneity in the degree of price stickiness across product groups also raises the degree of monetary non-neutrality (Nakamura and Steinsson, 2010). With multiple production sectors in the Indian economy, it could be, therefore, useful to examine the degree of price stickiness in the all India Consumer Price Index - Combined (CPI-C) and its implications for monetary policy. While a major chunk of the literature in the Indian context in recent times has been devoted largely towards validating the existence of the Phillips curve (PC) relationship in the Indian data (Mazumder, 2011; Behera, et al., 2017; Patra et al., 2021) and exploring different aspects of inflation forecasting (Dholakia and Kandiyala, 2018; Pratap and Sengupta, 2019; John, et al., 2020; Jose et al., 2022), little attention has been paid to differences in the price-setting behaviour and related heterogeneity in price dynamics across items in the basket. Literature suggests that the foundations of medium-term inflation forecasting lie in the expectations augmented PC, also referred to as the New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC), wherein the degree of nominal rigidity in prices is one of the key determinants of the slope of the curve (Aucremanne and Dhyne, 2004; Behera and Patra, 2020). This paper, while drawing insights from this literature, intends to examine the degree of price stickiness in the all India CPI-C and decomposes the basket into two separate indices viz., a sticky price index and a flexible price index. To attain this objective, the paper first documents the differences in the price-setting behaviour across 299 CPI-C items on the basis of whether the item comes with the tag of a maximum retail price (MRP), without any MRP tag (non-MRP) or its price is administered/regulated by the government, following which the items are classified into the two sub-indices based on certain important parameters such as ‘inflation and its volatility’; and ‘price momentum and its volatility’. While studies such as this abound in the case of advanced economies (AEs) [Bils and Klenow, 2004; Dias et al., 2004; Aucremanne and Dhyne, 2004; Dhyne et al., 2005; Alvarez et al., 2006; Alvarez et al., 2010; Bryan and Meyer, 2010; Millard and O’Grady, 2012; Reiff and Varhegyi, 2013], research in the Indian context is at a nascent stage with a limited number of studies focusing largely on food prices or wholesale price index (WPI) based firm-level price-setting behaviour (Tripathi and Goyal, 2012; Rather et al., 2015; Banerjee and Bhattacharya, 2017; Nadhanael, 2020). Based on such classification, the paper further investigates the sensitivity of sticky and flexible price components to output gap under an NKPC framework to better understand the underlying price dynamics which can aid in policy making. The time-period covered for this study spans over 2011-2019, as the all India CPI-C item level data are available starting from January 2011.1 The empirical section is based on quarterly data covering the period 2011:Q1-2019:Q4 (recognising a break in the item level data series during March-May 2020 owing to COVID-19 pandemic driven disruptions in data collection and compilation). It is observed that movements in headline inflation sync well with the flexible price inflation, whereas inflation excluding food and fuel (hereafter ‘core inflation’) shares a significant co-movement with sticky price inflation. Literature in the context of advanced economies has shown that the flexible price index tends to bounce violently from month to month as it responds strongly to changing market conditions, including the degree of economic slack. On the other hand, sticky prices are slow to adjust to economic conditions (Bryan and Meyer, 2010). Therefore, in this regard, while it could be expected that the flexible price index in the case of the Indian CPI would also react faster to the changing macroeconomic conditions, a lesser-known area is when, at what lag and to what extent the sticky price index would react to the same. Therefore, this paper tries to fill this gap in the existing literature in the Indian context. The relationship between sticky price index, economic slack and inflation expectations in an NKPC framework is estimated and the results are compared with the headline PC estimation. Overall, the findings indicate that the sticky price PC is much flatter than the headline PC or the flexible price PC, implying that it is less sensitive to changing demand conditions. The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section II discusses the extant literature on the relevance of this study for monetary policy, while providing the theoretical underpinnings on why certain prices are sticky. Section III provides a disaggregated analysis of item level CPI-C data in India and presents the approach used in the construction of the two sub-indices. Section IV lays out the theoretical framework for the empirical section along with discussing the methodology and empirical results. Section V concludes the paper. II.1 Evidence on Price Rigidity and Its Significance for Monetary Policy Assessing the extent of price rigidity is crucial for the conduct of monetary policy. PC theories based on sticky prices and imperfect information indicate that shifts in nominal aggregate demand lead to real output fluctuations depending on the extent of price rigidity in an economy (Kiley, 2000). In the absence of price stickiness, the real effect of monetary policy disappears (Banerjee, et al., 2020). Moreover, the impact assessment of any shock in the economy depends on the price/wage rigidities prevalent in the economy (Baudry et al., 2004; Bils et al., 2003). Since the adoption of inflation targeting (IT) in several economies, understanding the pricing behaviour of different items in the basket of the target price index has received greater attention. Moreover, as microeconomic rigidity often gives rise to aggregate nominal rigidity, there have been many studies, largely empirical, documenting the microeconomic pricing behaviour, in particular the frequency of microeconomic price adjustments, centred on specific products; market structure; as well as items in the CPI basket (Caballero and Engel, 2006).2 A few of them have categorised items into sticky and flexible price indices and explored the insights obtained therefrom in understanding the inflation process while concluding that the sticky price index can be an useful indicator for IT central banks (Bryan and Meyer, 2010; Reiff and Varhegyi, 2013). In terms of the frequency of price change, a number of studies reveal that many of the commodity prices are typically sticky and undergo revisions may be once in a year. For instance, one of the pioneering works in this area looked at 38 US news-stand magazine prices from 1953 to 1979 and reported that prices remained unchanged for a duration in the range of 1.8 years to 14 years (Cecchetti, 1986). Table 1 summarises the evidence on price stickiness both in the context of the advanced economies as well as in EMEs, in particular India. In the Indian context, the literature is rather limited, with some of the recent studies focusing on the price stickiness in food items based on the consumer price index for industrial workers (CPI-IW) data (Banerjee and Bhattacharya, 2019; Nadhanael, 2020). However, none of the studies relate to disaggregated CPI-C data to analyse price stickiness or the price formation process in general.3 The current study, using CPI-C, adds to this sparse empirical literature for assessing empirically the frequency of price adjustments and generating measures of sticky and flexible price indices along with examining the determinants of sticky prices in a NKPC framework. II.2 Why are Certain Prices Sticky - Theoretical Underpinnings As Blinder (1993) states, “One could literally fill many volumes with good empirical studies of wage and price stickiness, and many more with clever theories purporting to explain these phenomena. Yet, despite all this work, the range of admissible theories is wider than ever, and new theories continue to crop up faster than old ones are rejected.” Literature suggests an array of theories that could explain why certain prices are sticky. Table 2 provides a summary of such theories and their chief proponents. In contrast to the theories that provide the micro foundations to the observed phenomenon of macroeconomic price rigidity in a NKPC framework, Mankiw and Reis (2002) and in their further subsequent works have built another side to the story through their sticky information model, which suggests the prevalence of informational frictions among price-setters. For instance, a study by Zbaracki et al., (2004) on the costs associated with changing prices at a large manufacturing firm in the US shows that only a small percentage of these costs are the physical costs of printing and distributing price lists. Far more important are the “managerial and customer costs,” which include costs of information gathering, decision-making, negotiation and communication. Therefore, if firms face costs of collecting information and choosing optimal plans, then it could be more natural to assume that their adjustment process is time contingent. Subsequent literature has revealed that macro-models with sticky prices in an environment of sticky information are more consistent with micro and macro empirical evidence embodied in a PC framework (Knotek II, 2010). The all India CPI-C with base year 2012 has a total of 299 items in the basket,4 selected based on the Modified Mixed Reference Period (MMRP) data of Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES) conducted in 2011-12 [68th round of National Sample Survey (NSS)].5 These items are classified into 6 major groups, which are ‘food and beverages’, ‘pan, tobacco and intoxicants’, ‘clothing and footwear’, ‘housing’, ‘fuel and light’ and ‘miscellaneous’.6 In terms of weights in CPI-C, food and beverages group account for 46 per cent of the share, while the fuel and light group constitutes around 7 per cent. The remaining 47 per cent is generally termed as CPI-core in the policy-making parlance. The basket is, thus, a mixture of a wide variety of items, some of which are consumer durables (like television, washing machine, utensils), some are perishables (like vegetables and fruits) and others are services (like health, house rent and education), with goods constituting a significant share of 77 per cent. An important aspect of such a heterogeneous mix of items is the difference in their price-setting methods. (i) Pricing-based Classification of CPI-C A snapshot of the CPI-C data reveals stark differences in the movements of price indices across groups (Chart 1a). While the food index reflects significant volatility, which is largely a result of seasonal factors and supply-side shocks that generally impact food prices, the core index is comparatively steadier. Moreover, within food group, price indices of items sold under the public distribution system (PDS), like PDS-rice and PDS-wheat, change infrequently as their prices are fixed/administered by the government, whereas the non-PDS items (which also include rice and wheat) are sold at market prices. Further, perishable items, such as vegetables and fruits, are generally sold unpacked and price discovery is mostly restricted to the local markets or mandis through auctioning by traders. In addition, the fuel and light group comprises items whose prices are impacted by international price movements and/or fixed/regulated by the government or its various agencies with government policies having a direct impact on their prices [such as liquified petroleum gas (LPG) and electricity], alongside items whose prices are market determined (such as firewood and chips). CPI-core, comprising both goods and services, is extremely heterogeneous in its composition with the price indices of items displaying a varied mix of pricing. Services, such as railway fares and porter charges, do not have MRP but are much less volatile. In contrast, household durable goods are generally priced at MRP and hardly display spatial price differences. Their prices are set by the firms based on criteria like cost considerations, market structure (degree of competition) and demand elasticity. Furthermore, items such as petrol and diesel are fixed by the oil marketing companies (OMCs) and are also impacted by the excise duties, cess and value added tax (VAT) fixed and revised by the union and state governments from time to time, while prices of gold and silver are determined by international price movements. In sum, therefore, the price-setting methods within CPI could be very different not only across different items within a group, but also between items within the same product category. Taking into consideration such differences in the nature of price-setting across items within CPI-C, this paper classifies the complete basket of CPI-C on the basis of price-setting: MRP; non-MRP; a combination of MRP and non-MRP (referred to as ‘Mixed’7); and Fixed/Regulated pricing (Annex Table A1).8 The classification reveals that non-MRP items comprise a major share (46 per cent) in CPI-C followed by the MRP items (30 per cent) [Chart 1b]. CPI-goods have items across all the four different price-setting categories, whereas in the case of services, price-setting is either fixed or non-MRP based (Chart 1c). Moreover, non-MRP items comprise a major share in the fuel and light group followed by food and beverages (Chart 1d). The pricing of items within the fuel and light group is either fixed or non-MRP based. CPI-core has a major share of items with MRP based pricing. From the above sets of classification, it is clear that the movements in MRP and non-MRP based indices would have a key role to play in explaining the dynamics of overall inflation as these constitute three-fourth of the consumption basket. MRP based classification also includes items such as manufactured food products like edible oils (mostly sold in packed form with MRP tag), where both global prices and government-directed trade policies (particularly, alterations in import duties) have a major impact on prices. But the frequency of their price revisions, given that they are sold at MRP, in response to changes in global prices and government policies, can impart stickiness to their prices.  (ii) Direction and Frequency of Price Change In terms of the average price movements, the food group shows the highest positive and negative momentum, followed by the fuel group (Chart 2), which could be largely attributed to the higher share of non-MRP based price-setting in these groups. Interestingly, however, average price increases (positive momentum) and price decreases (negative momentum) broadly display similar order of magnitude, indicating that they are largely symmetric.  Surprisingly, the only exception to this pattern are the MRP based items in the food group, which show a higher average positive momentum as compared to the average negative momentum, reflecting downward rigidity in the prices of manufactured/packaged food items, which largely belong to the organised retail market. A price rise in the case of a packaged food item owing to certain adverse supply shocks could be easily passed on to the consumers. However, when such adverse shocks wane, the benefits may not be shared with the consumers by lowering product prices or moving back to the pre-shock price levels. This could be possible in food group given their low elasticity of demand as compared with the other household consumption items. Additionally, there is not much visible difference between the average momentum of the four categories in the core group. This is due to the fact that the core group has a high share of services items and most of the items are not subject to the kind of supply shocks that are common in the food group. Further, movements in inflation across the four different pricing-based indices clearly show that inflation in MRP based items has the least fluctuation. Since the formal adoption of flexible inflation targeting (FIT) in India in 2016, inflation in MRP based items has broadly hovered around the medium-term target of 4 per cent, while inflation across the other indices has recorded significant fluctuations on either side of the target (Chart 3). Alternatively, it is found that the distribution of inflation in the case of the MRP based items is strikingly different with much lesser variance, thus, revealing a heavier concentration of inflation around its mean; whereas the rest have much wider and heavier tails indicating the presence of extreme inflation prints (Chart 4). Further, in terms of volatilities of momentum, inflation and change in inflation, the MRP based items exhibit the lowest volatility as compared to the others (Annex Table A2).   Thus, the above nuances of the CPI-C data indicate that there are some price indices which do not change often and are sticky in nature, while the rest fluctuate more often and are thus, flexible. Therefore, based on these observations, the two sub-indices have been constructed within CPI-C, which are: CPI-sticky price index and CPI-flexible price index. (iii) Sticky and Flexible Price Indices Based on the observed characteristics of the MRP based pricing index, it forms the sticky price index-1 with a share of 19.4 per cent in CPI. Further, considering the fact that the services items within CPI have a lesser frequency of price change along with a lower volatility of inflation and change in inflation10, the CPI-sticky price index-2 is constructed by clubbing together ‘MRP’ and ‘services’, resulting into a combined share of 42.8 per cent in CPI-C. The counterparts of these two indices are termed as the flexible price indices. Table 3 provides the statistical properties of these indices in detail.

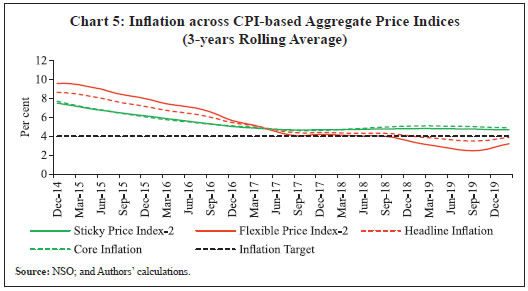

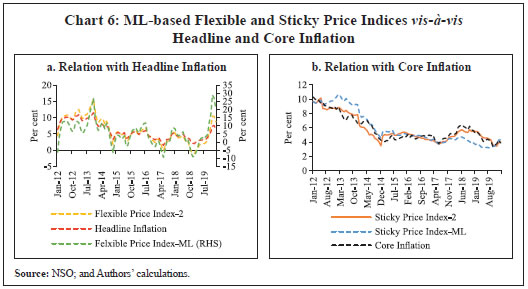

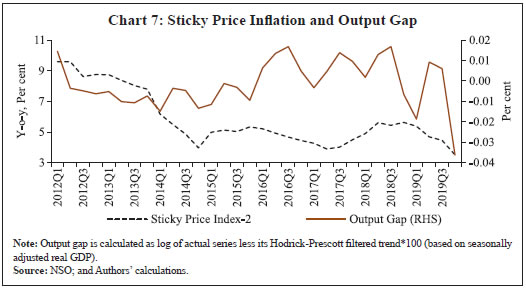

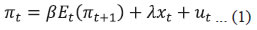

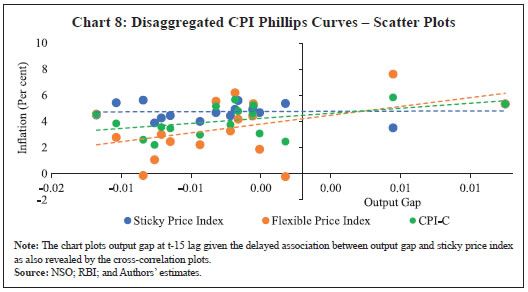

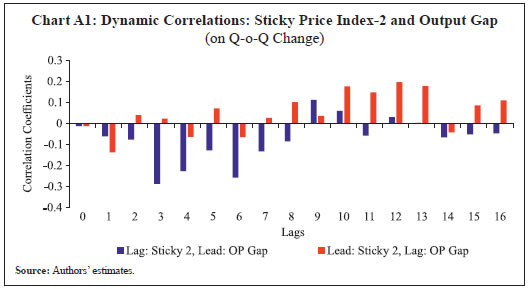

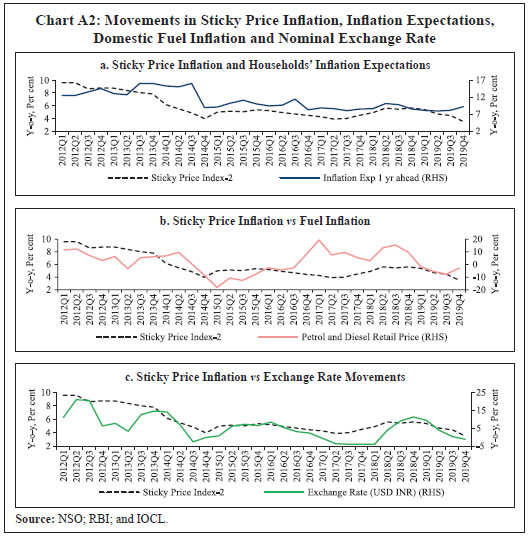

It may be observed that the sticky price indices have lower average momentum and inflation as compared to the flexible price indices. Additionally, they also record much lesser volatility in terms of various volatility parameters. Furthermore, it is observed that headline inflation is primarily driven by the movements in the flexible price inflation, while core inflation broadly aligns with the sticky price inflation (Chart 5). Moreover, chart 5 also reveals that while headline inflation eased significantly over the years (up to Q4:2019) in line with a fall in inflation in both sticky and flexible price indices, the extent of easing in core inflation, however, has been relatively less. The observed relative stability in core inflation is largely on account of its composition - a larger share of MRP-based items and services. Accordingly, while average headline inflation moved towards the target of 4 per cent, mean core inflation has stayed higher than the target inflation. Correlation coefficients indicate that inflation in flexible price index-1 has the highest correlation with headline inflation, whereas inflation in sticky price index-2 has the highest correlation with core inflation (Annex Table A3). (iv) Machine Learning Approach to Generate Sticky and Flexible Price Indices: An Alternative Approach As an alternative approach to generate flexible and sticky price indices, a K-means clustering12 is performed on the 299 items of CPI-C. The approach here is to identify two clusters of the items from the basket corresponding to flexible and sticky prices using two key data features - inflation volatility and frequency of price change during January 2014 to February 2020. Items having less inflation volatility and lower frequency of price change are expected to be classified under the sticky price cluster, while items having higher inflation volatility as well as higher frequency of price change are expected to fall under the flexible price cluster.13  Based on the results of the K-means clustering (K being set to 2), items are classified into sticky and flexible price clusters. These ML-based indices are then compared with pricing-based indices constructed in the previous section. Results show that the two indices move together, thereby providing further credence to our derived pricing-based measures of sticky price indices. In terms of their relationship with headline and core inflation, while headline inflation follows the ML-based flexible price index directionally, magnitude-wise the latter is more volatile (Chart 6a), indicating that the latter is primarily capturing the extreme volatile items of the basket. Further, the sticky price index-2 generated earlier tracks core inflation much better than the ML-based sticky price index (Chart 6b).14 This implies that core inflation is largely influenced by the price movements in the MRP-based items and services.15 Therefore, in the subsequent section, we consider the sticky price index-2 towards estimating the sticky price PC as it largely captures the underlying price movements that are less transient in nature. This implies that any sustained increase in its inflation could indicate building up of persistent price pressures in the economy and therefore, may need constant monitoring.  Section IV (i) Sticky Price Index and Its Sensitivity to Output Gap Having derived the two sub-indices of CPI-C, in this section we primarily focus on the dynamics of sticky price index. Literature provides ample evidence that sticky prices may not respond to each instance of demand fluctuation and that price stickiness has an impact on output-inflation trade-off (Parkin, 1986; Bryan and Meyer, 2010), which may lead to the non-neutrality of monetary policy (Gali, 2010). Such literature in the Indian context, however, is limited. Therefore, this section studies the linkages between domestic demand conditions/measures of economic slack and the CPI-based sticky price index in a NKPC framework. The sticky-price index-2 is used for this purpose. A cursory look at the data reveals that the sticky price inflation does not have a very close correspondence with the economy-wide measure of slack, which is output gap (Chart 7).  Further, pair-wise contemporaneous correlation between quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q) change in sticky price index and output gap turns out to be negative (Annex Table A4). Therefore, dynamic correlations (cross-correlations) are computed to check for any delayed positive association (Annex Chart A1). Results show that changes in sticky price index lag changes in output gap with a significant delay of 2 years and more. Theoretical Framework and Methodology In order to further validate the relationship between sticky price index and demand conditions (proxied by output gap), we base our empirical framework on the insights drawn from the NKPC16 in standard macroeconomic theory. The NKPC, an extension of the original PC with its theoretical micro foundations, has received widespread acceptance in the monetary policy domain and has been widely adopted by central banks globally as the key price determination equation in macro-models. Given this backdrop, a purely forward-looking NKPC resembles equation (1) below:  where, πt is inflation at time period t, Et(πt+1) is inflation expectations at time period t and xt represents a proxy for marginal cost or demand conditions17 prevailing in the economy. The disturbance term ut can be interpreted as measurement error or any other combination of unobserved cost-push shocks, such as shocks to the mark-up or input prices (eg., an oil price shock). The principle micro foundation that is inherent in the NKPC framework is the existence of price rigidity, wherein in a microeconomic environment consisting of identical monopolistically competitive firms, firms face constraints on price adjustment18. Literature suggests that even under rational expectations, partial rigidities in the form of information lags or nominal rigidities in prices and wages play a significant role in explaining the observed relationships between inflation and unemployment (Taylor, 1980). Given these facets and empirical difficulties in fitting a purely forward-looking NKPC in the US inflation data, equation (1) underwent modifications that included lagged inflation terms, often termed as ‘intrinsic inflation persistence’ (Mavroeidis et al., 2014). While Gali and Gertler (1999) introduced lagged terms of inflation under the assumption that a fraction of firms updates their prices using some backward-looking rule of thumb, Fuhrer and Moore (1995) relied on the staggered wage contracts to do the same. Some of the newer studies assumed that firms that are unable to re-optimise upon their prices as in the Calvo model often index their prices to past inflation (Christiano et al., 2005; Sbordone, 2005). Thus, the introduction of intrinsic inflation persistence in the PC framework drove the emergence of the ‘hybrid NKPC’, which resembles equation (2) below:  Importantly, the inflation expectations term in equation (2), which is supposed to be an endogenous variable in the system and in fact is unobservable, poses estimation issues in the NKPC framework. Therefore, to correct for such estimation anomalies, literature has come to a consensus on different methods to deal with the inflation expectations variable while estimating the NKPC. These methods include: (i) replacing expectations with actual inflation outcomes and use appropriate instruments (generalised instrumental variables (GIV) framework) [McCallum, 1976; Hansen and Singleton, 1982; Roberts, 1995; Gali and Gertler, 1999]; (ii) deriving expectations in a particular reduced-form model (vector autoregression (VAR) framework) [Fuhrer and Moore, 1995; Sbordone, 2002]; and (iii) using direct measures of expectations (available through inflation expectations surveys) [Roberts, 1995]. Relying on survey-based inflation expectations avoids the need for modelling inflation expectations using statistical/econometric methods, though some researchers feel that the procedure allows for non-rational price setting, the understanding of which is rather limited or at a relatively nascent stage. Therefore, survey-based measures of inflation expectations can be considered as one of the useful ways to look at the intuition behind price-setting being partially forward-looking, partially backward-looking as well as responding to economy-wide aggregate demand conditions. Therefore, considering survey-based inflation expectations in the NKPC framework yields the following representation:  Against this backdrop, equation (4) below forms the base for the empirical framework attempted in this section.   (ii) Empirical Estimation and Results Before proceeding for the PC estimation, we first look at the relationship between economic slack (represented by output gap) and the sticky price index-2 and compare that to CPI- C and flexible price index. The slope of the trendline in the case of the sticky price index is flatter as compared to that in the headline CPI-C, while the flexible price index has the steepest slope, indicating its larger reaction to fluctuations in demand conditions in the economy (Chart 8). Therefore, estimation of PC for these indices would enable us to validate this graphical observation. Based on the outlined framework in the previous sub-section [equation (4)], empirical exercise using quarterly data for the sample period 2011:Q1-2019:Q4 is conducted. Data sources used in the empirical exercise are provided in Annex Table A5.1 and variable representation and description are provided in Annex Table A5.2. All variables are converted to their natural logarithms, wherever applicable, and then de-seasonalised using US Census X-13ARIMA method, after which they are used in their first-differenced forms (i.e., q-o-q change) in the model because of their non-stationarity. Stationarity of the variables are tested by employing the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) tests of unit roots, the results of which are provided in Annex Table A6.  Results presented in table 4 indicate that output gap has a positive and significant impact on the changes in sticky price index and the magnitude of impact turns out to be 0.04 per cent. However, the impact of output gap happens with a significant lag of around 3 years.22 Given the average duration of business cycles to be around five years in India (with an overall range of 2-8 years),23 prices that are sticky may undergo revisions once/twice during such cycles, which could have been possibly reflected in the empirical results obtained. With regard to inflation expectations, results indicate that changes in inflation expectations positively impact sticky price changes with significant lag. The estimated impact turns out to be 0.01 per cent with a lag of 8 quarters.24 The results also point to a significant presence of intrinsic persistence as reflected by the coefficients of the lagged changes in the sticky price index. Having obtained the estimates for the sticky price PC, we now compare the results with the headline PC and the flexible PC estimates (Table 4; columns 2 and 3). The results show that the sticky price PC is much flatter and slower to respond to changes in demand conditions as compared to the headline PC estimates, while the flexible PC is the steepest indicating its larger reaction to fluctuations in demand conditions in the economy, thus, re-validating Chart 8. Overall, the results indicate that the sticky price PC is much flatter as compared to the headline PC followed by the flexible PC, reflecting its meek reaction to changing demand conditions. Additionally, the results also highlight the contribution of intrinsic persistence in imparting price stickiness as indicated by a significantly higher coefficient of its own lags. As a robustness check, another set of regression specification was estimated using control variables such as exchange rate changes, average retail prices of petrol and diesel across four metro cities of India (Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai) as a proxy for input cost pressures, as well as rainfall deviation from the long period average and retail prices of primary vegetables in the case of the flexible price equation. The results (Annex Table A7) are broadly in line with those obtained in Table 4.25 In new Keynesian models, monetary policy can become non-neutral because of the widely observed sticky behaviour in prices. Price stickiness, thus, creates scope for monetary policy to pursue the goals of output and employment. While literature in the Indian context has been devoted largely to validating the presence of the PC and exploring different aspects of inflation forecasting, research on differences in price-setting methods and related heterogeneity in price dynamics at the disaggregated level of the all India CPI has been limited. This paper, therefore, addresses this void in the existing literature and analyses CPI-C at a disaggregated level on the basis of the different price-setting methods. The study first classifies the items based on four different price-setting methods – MRP; non-MRP; a combination of MRP and non-MRP (termed as ‘Mixed’); and Fixed/Regulated – and then using this classification and certain parameters such as ‘price momentum and its volatility’ and ‘inflation and its volatility’ constructs two separate indices, viz., Sticky Price Index and Flexible Price Index. The results show that the sticky price index constitutes around 43 per cent of the overall CPI-C basket and by construction records lower average momentum and inflation as well as much lesser volatility compared to the flexible price index. Furthermore, it is observed that headline inflation is primarily driven by the movements in the flexible price inflation, while core inflation broadly aligns with the sticky price inflation. PC estimates based on the NKPC framework indicate that the sticky price PC is much flatter as compared to the PC based on headline CPI-C and the flexible price PC. Therefore, the results imply that the sticky price PC is less sensitive to changing conditions of economic slack. Additionally, the impact of output gap occurs with a significant lag of around 3 years, suggesting that the sticky price index is slow to adjust to changes in economic slack. Given the average duration of business cycles to be around five years in India, prices that are sticky may undergo revisions once or twice during such cycles, which could possibly be the underlying reason behind the slow and lagged adjustment to output gap. With regard to inflation expectations, results indicate that changes in inflation expectations positively impact sticky price changes, although with some lag. Furthermore, the results reveal a higher degree of intrinsic persistence in the sticky price index, which explains a major part of its stickiness. All of these together imply that in a situation when the sticky price inflation turn upwards, it may remain elevated for a considerable period of time because of its high intrinsic persistence, thus, posing risks for inflation turning generalised. Therefore, monetary policy should remain wary of the underlying inflationary pressures which may be observed by a careful monitoring of the sticky price index. Therefore, from the perspective of India’s monetary policy, analysing movements in the sticky price index could be an important aid in gauging the underlying price pressures in the economy (whether transitory or permanent) and the pricing power of firms, thus providing a deeper understanding of the overall inflation dynamics. References Adam, K., and Padula, M. (2011). Inflation dynamics and subjective expectations in the United States. Economic Inquiry, 49(1), 13-25. Álvarez, L. J., Burriel, P., and Hernando, I. (2010). Price-setting behaviour in Spain: Evidence from micro PPI data. Managerial and Decision Economics, 31(2-3), 105-121. Alvarez, L. J., Dhyne, E., Hoeberichts, M. M., Kwapil, C., Bihan, L. H., Lunnemann, P., Martins, F., Sabbatini, R., Stahi, H., Vermeulen, P. and Vilumnen, J. (2006). Sticky prices in the euro area: a summary of new micro-evidence. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(2/3), 575-584 Aucremanne, L., and Dhyne, E. (2004). How frequently do prices change? Evidence based on the micro data underlying the Belgian CPI. European Central Bank Working Paper No. 331, April. Ball, L. and Romer, D. H. (1987). Sticky prices as coordination failure. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w2327. Banerjee, S. and R. Bhattacharya (2017). Micro-level price setting behaviour in India: evidence from group and sub-group level CPI-IW data. NIPFP Working paper No. 217. Banerjee, S., Basu, P., and Ghate, C. (2020). A monetary business cycle model for India. Economic Inquiry, 58(3), 1362-1386. Baudry, L., Bihan H. L., Sevestre, P. and S. Tarrieu (2004). Price rigidity- Evidence from French CPI micro-data. European Central Bank, Working Papers Series No 384, August. Baumgartner, J., Glatzer, E., Rumler, F. and Stiglbauer, A. (2005). How frequently do consumer prices change in Austria? Evidence from micro CPI data. European Central Bank, Working Paper Series No. 523, September. Behera, H. K., and Patra, M. D. (2020). Measuring trend inflation in India”, RBI Working Paper Series: 15/2020. Behera, H. K., Wahi, G., and Kapur, M. (2017). Phillips curve relationship in India: Evidence from state level analysis. RBI Working Paper Series : 08/2017. Behera, H. and Sharma, S. (2019). Does financial cycle exist in India?. RBI Working Paper Series: 03/2019 Bils, M, P. Klenow and O. Kryvtsov (2003). Sticky prices and monetary policy shocks. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Quarterly Review,27(1), Winter 2003, pp. 2–9 Bils, M., and Klenow, P. J. (2004). Some evidence on the importance of sticky prices. Journal of political economy, 112(5), 947-985. Blanchard, O.J. (1983). Price asynchronization and price level inertia, in inflation, debt and indexation. R. Dornbusch and M. Simonsen eds., Inflation, Debt and Indexation, MIT Press, pp. 3—24. Blinder, A. S. (1993). Why are prices sticky? Preliminary results from an interview study. In Optimal Pricing, Inflation and the Cost of Price Adjustment, Eytan S. and Yoram, W. eds. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (pp. 409-421). Blinder, A.S. (1982). Inventories and sticky prices: More on the microfoundations of macroeconomics. American Economic Review, 72(3), June, pp. 334-348. Boivin J., Giannoni, M.P., and Mihov, I. (2009). Sticky prices and monetary policy: Evidence from disaggregated US data. American Economic Review, 99(1), March, pp. 350–384. Bryan, M. F. and Meyer, B. (2010). Are some prices in the CPI more forward looking than others? We think so. Federal Reserve of Cleveland, Economic Commentary Number 2010-2, May 19, 2010. Caballero, R. J. and Engel, E. M.R.A. (2006). Price stickiness in Ss models: Basic properties”, MIT. Calvo, G. A. (1983). Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(3), 383-398. Cecchetti, S. G. (1986). The frequency of price adjustment: A study of the newsstand prices of magazines. Journal of Econometrics, 31(3), 255-274. Chong, T.T.L., Rafiq, M.S., and Zhu, T. (2013). Are prices sticky in large developing economies? An empirical comparison of China and India. MPRA Paper No. 60985, December 2013. Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M., and Evans, C. L. (2005). Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 1-45. Cooper, R., and John, A. (1988). Coordinating coordination failures in Keynesian models. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103(3), 441-463. Dholakia, R. H., and Kandiyala, V. S. (2018). Changing dynamics of inflation in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 53(9), 65-73. Dhyne, E., Alvarez, L. J., Bihan, L.H., Veronese, G., Dias, D., Hoffmann, J, Jonker, N., Lunnemann, P., Rumler, F. and Vilmunen, J. (2005). Price setting in the euro area: Some stylized facts from individual consumer price data. European Central Bank, Working Paper Series No. 524, September. Dias, M., Dias, D., and Neves, P. D. (2004). Stylised features of price setting behaviour in Portugal: 1992-2001. European Central Bank, Working Paper Series No. 332. Dotsey, M., King, R. G., and Wolman, A. L. (1999). State-dependent pricing and the general equilibrium dynamics of money and output. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 655-690. Erceg, C. J., Henderson, D. W., and Levin, A. T. (2000). Optimal monetary policy with staggered wage and price contracts. Journal of Monetary Economics, 46(2), 281-313. Erlandsen, S.K. (2014). Sticky prices and inflation expectations in Norway. Staff Memo No. 14, 2014, Norges Bank. Fischer, S. (1977). Long-term contracts, rational expectations, and the optimal money supply rule. Journal of Political Economy, 85(1), 191-205. Fisher, P. G., Mahadeva, L., & Whitley., J. D. (1997). The output gap and inflation–experience at the Bank of England. BIS Conference Papers, Vol. 4. Fougère, D., Bihan, H. L., and Sevestre, P. (2005). Heterogeneity in price stickiness: a microeconometric investigation.European Central Bank, Working Paper Series No. 536, October. Fuhrer, J., and Moore, G. (1995). Inflation persistence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1), 127-159. Gagnon, E., and Khan, H. (2001). New Phillips curve with alternative marginal cost measures for Canada, the United States, and the Euro Area. Bank of Canada (No. 2001-25). Gali, J., and Gertler, M. (1999). Inflation dynamics: A structural econometric analysis. Journal of Monetary Economics, 44(2), 195-222. Gali, J., Gertler, M., and Lopez-Salido, J. D. (2001). European inflation dynamics. European Economic Review, 45(7), 1237-1270. Galí, J. (2010). The New-Keynesian approach to monetary policy analysis: Lessons and new directions. In The science and practice of monetary policy today, pp. 9-19. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. Ghani, E. (1991). Rational expectations and price behavior: A study of India. Journal of Development Economics, 36 (2), October, pp. 295-311. Gordon, R. J. (1981). Output fluctuations and gradual price adjustment. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper Series, w0621. Hall, R. E., Blanchard, O. J., and Hubbard, R. G. (1986). Market structure and macroeconomic fluctuations. Brookings papers on economic activity, 1986(2), 285-338. Hansen, L. P., and Singleton, K. J. (1982). Generalized instrumental variables estimation of nonlinear rational expectations models. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(5), September, pp. 1269-1286. Henkel, L. (2020). Sectoral output effects of monetary policy: Do sticky prices matter? European Central Bank, Working Paper Series No. 2473, October. John, J., Singh, S. and Kapur, M. (2020). Inflation forecast combinations – The Indian experience”, RBI Working Paper Series : 11/2020. Jose, J., Shekhar, H., Kundu S., Kishore, V. and Bhoi B. B. (2022). Alternative inflation forecasting models for India –What performs better in practice?”, RBI Occasional Papers, Vol. 42(1). Kashyap, A.K. (1995). Sticky prices: New evidence from retail catalogs. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110 (1), February, pp. 245-274. Kiley, M.T., (2000). Endogenous price stickiness and business cycle persistence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, February, 2000, 32(1), pp. 28-53. Knotek II, E. S. (2010). A tale of two rigidities: Sticky prices in a sticky-information environment. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42(8), 1543-1564. Mankiw, N. G. (1985). Small menu costs and large business cycles: A macroeconomic model of monopoly. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100(2), 529-537. Mankiw, N. G., and Reis, R. (2002). Sticky information versus sticky prices: a proposal to replace the New Keynesian Phillips curve. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1295-1328. Mavroeidis, S., Plagborg-Møller, M., and Stock, J. H. (2014). Empirical evidence on inflation expectations in the New Keynesian Phillips Curve. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 124-88. Mazumder, S. (2011). The empirical validity of the New Keynesian Phillips curve using survey forecasts of inflation. Economic Modelling, 28(6), 2439-2450. McCallum, B. T. (1976). Rational expectations and the natural rate hypothesis: some consistent estimates. Econometrica. Journal of the Econometric Society, 44(1), January, pp. 43-52. Millard, S. and O’Grady, T. (2012). What do sticky and flexible prices tell us?”, Bank of England Working Paper No. 457, July 20. 2012. Nadhanael, G.V. (2020). Are food prices really flexible? Evidence from India. RBI Working Paper Series: 10/2020. Nakamura, E., and Steinsson, J. (2010). Monetary non-neutrality in a multisector menu cost model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 961-1013. National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). (2014). Household consumption of various goods and services in India 2011-12. Government of India, June 2014. Parkin, M. (1986). The output-inflation trade-off when prices are costly to change. Journal of Political Economy, 94 (1), February, pp. 200-224. Patra, M.D., Behera, H. and John, J. (2021). Is the Phillips Curve in India Dead, Inert and Stirring to Life or Alive and Well? RBI Bulletin Article, November 2021. Pratap, B., and Sengupta, S. (2019). Macroeconomic forecasting in India: Does machine learning hold the key to better forecasts? RBI Working Paper Series: 04/2019. Rangarajan, C., Dev, S. M., Sundaram, K., Vyas, M. and Datta, K.L., (2014). Report of the expert group to review the methodology for measurement of poverty. Planning Commission, June 2014 Rather, S.R., Durai, S.R.S. and Ramachandran, M. (2015). Asymmetric price adjustment – evidence for India. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 12 (2), November, pp. 73-79. Reiff, A. and Varhegyi, J. (2013). Sticky price inflation index: An alternative core inflation measure. MNB Working Papers, No. 2013/2, Magyar Nemzeti Bank, Budapest. Roberts, J. M. (1995). New Keynesian economics and the Phillips curve. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 27(4), 975-984. Rotemberg, J. J. (1982). Sticky prices in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 90(6), pp. 1187-1211. Rudebusch, G. D. (2002). Assessing nominal income rules for monetary policy with model and data uncertainty. The Economic Journal, 112(479), pp. 402-432. Sbordone, A. M. (2002). Prices and unit labor costs: a new test of price stickiness. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49(2), pp. 265-292. Sbordone, A. M. (2005). Do expected future marginal costs drive inflation dynamics? Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(6), pp. 1183-1197. Taylor, J. B. (1979). Staggered wage setting in a macro model. The American Economic Review, 69(2), pp. 108-113. Taylor, J. B. (1980). Aggregate dynamics and staggered contracts. Journal of political economy, 88(1), pp. 1-23. Tripathi, S. and Goyal, A. (2012). Relative prices, the price level and inflation: Effects of asymmetric and sticky adjustment. IGIDR, WP-2011-026. Vilmunen, J. and H. Laakkonen (2005). How often do prices change in Finland? Evidence from micro CPI data. Bank of Finland, unpublished mimeo. Zbaracki, M. J., Ritson, M., Levy, D., Dutta, S., and Bergen, M. (2004). Managerial and customer costs of price adjustment: direct evidence from industrial markets. Review of Economics and statistics, 86(2), pp. 514-533.   * Sujata Kundu is Assistant Adviser at the Department of Economic and Policy Research, Reserve Bank of India. Himani Shekhar and Vimal Kishore are Managers at the same Department. The authors are sincerely thankful to Binod B. Bhoi, Rajesh Kavediya, Joice John and an anonymous referee for their valuable comments and suggestions on the paper. However, the views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the institution they are affiliated with. 1 The all India combined consumer price index (CPI-C) series with base year 2010 was released from January 2011 by the National Statistical Office (NSO). The base year of CPI-C was revised to 2012 from January 2015 in order to align the weighting diagram and item basket with the latest available all India consumer expenditure survey (CES) 2011-12. 2 The literature has focussed on two aspects of sticky price models – ‘time dependent’ (Taylor and Calvo models) where prices are set for a number of periods or each period a fixed fraction of firms have an opportunity to adjust prices to new information and ‘state dependent’ (state of the economy) where firms choose when to change prices depending on ‘menu costs’ (Dotsey et al., 1999). Stickiness of prices also has an impact on the output-inflation trade-off. Costly price-setting may make it inefficient to change prices at each instance of demand fluctuation (Parkin, 1986). 3 The analysis based on CPI-C assumes significance as headline inflation based on CPI-C is the nominal anchor under the flexible inflation targeting (FIT) monetary policy framework in India. Further, CPI-C provides price indices for 299 items comprising both food and non-food products. While there are other data sources that provide high frequency price data on primarily food items, similar data sources for prices of non-food items remain scarce. 4 CPI-C with base year 2010 had 318 items, while CPI-C with base year 2012 has 299 items. Item level data in the new base year series are available from January 2014. Therefore, in order to generate a longer time series, the common items in the two series were used to backcast the CPI-C series till January 2011. 5 In MMRP, the consumer expenditure data are gathered from the households using the recall period of: (a) 365-days for clothing, footwear, education, institutional medical care, and durable goods; (b) 7-days for edible oil, egg, fish and meat, vegetables, fruits, spices, beverages, refreshments, processed food, pan, tobacco and intoxicants; and (c) 30-days for the remaining food items, fuel and light, miscellaneous goods and services including non-institutional medical care; rents and taxes (NSSO, 2014; Rangarajan et al., 2014). The weighting diagrams of these items in CPI-C are derived on the basis of average monthly consumer expenditure of an urban/rural household obtained from the same survey. 6 The National Statistical Office (NSO), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) is the primary data source for CPI-C. 7 Items such as rice and milk can be sold in packed form with an MRP tag as well as in loose form without the MRP tag. As NSO collects price data for most popular item in a market, it can be a mix of both MRP and non-MRP based price-setting from different markets. 8 While there could be concerns related to subjectivity behind the classification of the items under the different pricing methods (viz., MRP, non-MRP, a combination of MRP and non-MRP (Mixed), and Fixed/Regulated), in the absence of any proper documentation available with respect to such a classification, the method employed in the paper seemed to be the appropriate as well as a feasible one for research purpose. 9 Note that these are not the average of annualised momentum. Data period starts from January 2014, implying the availability of momentum from February 2014. Momentum refers to the month-on-month growth rate of the CPI. 10 CPI-services (January 2011-February 2020) – mean inflation: 6.39 per cent, inflation volatility: 2.13 per cent, mean momentum: 0.53, momentum volatility: 0.42, change in inflation volatility: 0.51 percentage point. 11 The study considers price indices rather than actual prices for the construction of the sticky and the flexible price indices, which limits the scope for looking at the actual frequency of price change as indices change almost every month, while actual prices may remain fixed for a considerable duration. This is reflected in the similar mean momentum across the indices, although the volatility in momentum is much different in the sticky price indices as compared to the flexible price indices. Therefore, parameters such as inflation and its volatility as well as momentum and its volatility are used which help us to bring out the differences in terms of price stickiness across the various items in CPI-C. 12 It is an unsupervised machine learning (ML) technique. 13 Another K-means clustering was performed on 275 CPI items relying on the same features from January 2011 to December 2013 (among the 318 items in the old base year 2010, 275 items could be mapped as common items in the new base year 2012). Using suitable linking factors, the two series are then combined to generate one complete series starting from January 2011. Although the classification of 37 items changes when using the old base data, any observed change at the level of aggregate index is negligible. 14 Correlation coefficients between the two ML based indices and headline/core inflation are also compared with the correlation coefficients obtained earlier. The comparison indicates that the ML-based sticky and flexible price indices have a lower correlation with core and headline inflation, respectively (Annex Table A3). 15 The K-means algorithm classifies an overwhelming number of items in the sticky price cluster (236 items in the current base). Majority of the items which have been identified as MRP (except 5 out of 89) fall under the sticky price cluster as per this classification. Moreover, 11 out of 17 items in the Fixed classification fall under sticky price cluster, which are primarily services. Since the classification by this method is heavily skewed towards the sticky price cluster, this study considers and relies on indices constructed purely based on the observed underlying data characteristics [as provided in Section III - (iii)] for the empirical analysis. 16 The NKPC has its origins in the works of Fischer (1977) and Taylor (1979). It hinges on inflation being primarily a forward-looking process, according to which current inflation is driven by expectations of future real economic activity rather than past shocks. It, thus, implies that monetary policy can affect inflation through the management of inflation expectations (Mavroeidis et al., 2014) and expectations change as the world is not frictionless, rather imperfections and factor market rigidities could be the norm. In the marginal cost formulation of the NKPC, the fundamental relations are the conditions linking unit labour cost to inflation. The circumstances under which the output gap becomes the appropriate forcing process in the PC are in cases of price stickiness accompanied by a competitive and flexible labour market, as discussed in Erceg et al., (2000) and Galí, et al., (2001). The marginal cost formulation of the PC is the more general relationship, and this is stressed by Galí, et al., (2001) and Gagnon and Khan (2001). 17 Marginal cost variable is replaced with the output gap in NKPC estimation as according to Gali and Gertler (1999), in the standard sticky price framework without variable capital there is an approximate log-linear relationship between the output gap and marginal cost. Even with variable capital, simulations suggest that the relation remains very close to proportionate. 18 Calvo (1983) assumes that nominal individual prices are not subjected to continuous revisions; and price revisions are not synchronous. Rotemberg (1982) assumes that changing prices could be costly for firms possibly due to the difficulties that it could pose on consumers. 19 xt is stated as the main forcing variable in Mavroeidis et al., (2014). 20 Hybrid NKPC specifications in Gali and Gertler (1999), Sbordone (2005), and Christiano et al., (2005) include only one lagged term of inflation. 21 Since the purpose of the paper is to estimate the sensitivity of the sticky price index to the demand conditions in the economy, we do not consider additional control variables denoted by ωt in our base model. However, as a robustness check for our results we have re-estimated the base model using additional controls as indicated in the paper, the results of which are presented in the Annex. 22 Another paper that establishes the PC relationship in the context of India using CPI-C data, although on headline inflation, shows that the impact of output gap on headline inflation occurs with a lag of around 2 years [Jose, et al., 2022]. Other studies that show the delayed impact of output gap on inflation include Fisher et al. (1997). 23 See Behera and Sharma (2019). 24 Inflation expectations are on y-o-y basis. In the model change in inflation expectations has been incorporated, which makes the explanatory variable in percentage points. Therefore, the coefficient corresponding to the q-o-q change in inflation expectations is multiplied by 100 for impact comparison purpose across variables. 25 The results also indicate the significance of input cost pressures and changes in nominal exchange rate (INR-USD) in determining changes in the sticky price index. Simple line plots (Annex Chart A2) also show a lagged co-movement between these variables and sticky price inflation. Further, annex Table A4 provides the contemporaneous correlation on q-o-q change between the sticky price index and the other control variables. Results indicate that the q-o-q change in the sticky price index shares statistically significant and positive correlation with exchange rate changes. In the case of the flexible price index, the average retail prices of tomato, onion and potato (DCA TOP) and rainfall deviation from its long period average (LPA), turn out to be the two major factors influencing its dynamics because the food group constitutes a major share of the flexible price index. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

പേജ് അവസാനം അപ്ഡേറ്റ് ചെയ്തത്: