IST,

IST,

The Performance of Regional Rural Banks (RRBs) in India: Has Past Anything to Suggest for Future?

Given the multi agency share holding, this study makes an attempt to enquire into such factors that influence the performance of the RRBs and the role played by sponsor bank in a broader scenario. The problem has been approached in a deductive pattern. First, an attempt is made to identify the extent of the problem of loss making RRBs and see if they are confined to some particular sponsor banks or States. If the problem banks and States could be identified that would help in focussing the attention for an enduring solution. Subsequently, a model-based approach has been pursued to identify the factors that are responsible for the problems faced by the RRBs. This study contributes to the literature on RRBs primarily in two ways. First, the issues concerning RRBs are an area that is less visited empirically (econometrically) compared to the vast literature on commercial banks. Whatever studies have emerged on the topic, they have primarily relied on exploratory analysis done for a particular year or on a group of RRBs to draw inferences. This kind of an approach has a serious limitation in that the findings are guided by the choice of the year of analysis or the particular RRB(s) in question. To overcome this problem, one needs to consider, as attempted in this paper, a reasonably long period for analysis where extreme observations would be evened out so that one gets results that are more dependable. This study is an attempt in that direction. The present study considers the entire population rather than a few RRBs and a ten-year period for empirical analysis so that results are broad based and robust. Second, given the attention at the policy level to restructure the RRBs, it is necessary that the behaviour of RRBs be analysed separately for the profit and loss making ones, than all RRBs bunched together so that it helps in policy formulation. Such an approach has been followed in this study. The rest of the paper is organised in six segments. Section I provides a brief review of the course for restructuring and financial viability of RRBs suggested by different committees over the years. Section II reviews briefly the different factors identified in the literature that affects the financial performance of commercial banks and also the extant literature on factors affecting performance of RRBs. A bird’s eye view of the spatial distribution of the performance of RRBs across the States and sponsor banks is given in section III. The methodology of the empirical analysis is discussed in Section IV. Section V discusses the empirical results. Concluding observations are set out in Section VI. Section I Restructuring Strategies The financial viability of RRBs has engaged the attention of the policy makers from time to time. In fact, as early as 1981, the Committee to Review Arrangements for Institutional Credit for Agriculture and Rural Development (CRAFICARD) addressed the issue of financial viability of the RRBs. The CRAFICARD recommended that ‘the loss incurred by a RRB should be made good annually by the shareholders in the same proportion of their shareholdings’. Though this recommendation was not accepted, under a scheme of recapitalisation, financial support was provided by the shareholders in the proportion of their shareholdings. Subsequently, a number of committees have come out with different suggestions to address the financial non-viability of RRBs. For instance, the Working Group on RRBs (Kelkar Committee) in 1984 recommended that small and uneconomic RRBs should be merged in the interest of economic viability. Five years down the line, in a similar vein, the Agricultural Credit Review Committee (Khusro Committee), 1989 pointed out that ‘the weaknesses of RRBs are endemic to the system and non-viability is built into it, and the only option was to merge the RRBs with the sponsor banks. The objective of serving the weaker sections effectively could be achieved only by self-sustaining credit institutions’. The Committee on Restructuring of RRBs, 1994 (Bhandari Committee) identified 49 RRBs for comprehensive restructuring. It recommended greater devolution of decision-making powers to the Boards of RRBs in the matters of business development and staff matters. The option of liquidation again was mooted by the Committee on Revamping of RRBs, 1996 (Basu Committee). The Expert Group on RRBs in 1997 (Thingalaya Committee) held that very weak RRBs should be viewed separately and possibility of their liquidation be recognised. They might be merged with neighbouring RRBs. The Expert Committee on Rural Credit, 2001 (Vyas Committee I) was of the view that the sponsor bank should ensure necessary autonomy for RRBs in their credit and other portfolio management system. Subsequently, another committee under the Chairmanship of Chalapathy Rao in 2003 (Chalapathy Rao Committee) recommended that the entire system of RRBs may be consolidated while retaining the advantages of regional character of these institutions. As part of the process, some sponsor banks may be eased out. The sponsoring institutions may include other approved financial institutions as well, in addition to commercial banks. The Group of CMDs of Select Public Sector Banks, 2004 (Purwar Committee) recommended the amalgamation of RRBs on regional basis into six commercial banks - one each for the Northern, Southern, Eastern, Western, Central and North-Eastern Regions. Thus one finds that a host of options have been suggested starting with vertical merger (with sponsor banks), horizontal merger (amongst RRBs operating in a particular region) to liquidation by different committees that have gone into the issue of financial viability and restructuring strategies for the RRBs. More recently, a committee under the Chairmanship of A.V Sardesai revisited the issue of restructuring the RRBs (Sardesai Committee, 2005). The Sardesai committee held that ‘to improve the operational viability of RRBs and take advantage of the economies of scale, the route of merger/amalgamation of RRBs may be considered taking into account the views of the various stakeholders’. Merger of RRBs with the sponsor bank is not provided in the RRB Act 1976. Mergers, even if allowed, would not be a desirable way of restructuring. The Committee was of the view that merging a RRB with its sponsor bank would go against the very spirit of setting up of RRBs as local entities and for providing credit primarily to weaker sections. Having discussed various options for restructuring, the Committee was of the view that ‘a change in sponsor banks may, in some cases help in improving the performance of RRBs. A change in sponsorship may, inter alia; improve the competitiveness, work culture, management and efficiency of the concerned RRBs’. Against this backdrop, a number of issues need empirical probing. Such as, which are the RRBs that need focus and whether for them the sponsor bank has really to be made accountable. All these issues fall under the broader questions of what factors drive the performance of RRBs? and do the sponsor banks have a role to play? Section II reviews the literature on factors affecting performance of a commercial bank in general and also in the context of RRBs.Section

II RRBs though operate with a rural focus are primarily scheduled commercial banks with a commercial orientation. Beginning with the seminal contribution of Haslem (1968), the literature probing into factors influencing performance of banks recognises two broad sets of factors, i.e., internal factors and factors external to the bank. The internal determinants originate from the balance sheets and/or profit and loss accounts of the bank concerned and are often termed as micro or bank-specific determinants of profitability. The external determinants are systemic forces that reflect the economic environment which conditions the operation and performance of financial institutions. A number of explanatory variables have been suggested in the literature for both the internal and external determinants. The typical internal determinants employed are variables, such as, size and capital [Akhavein et al. (1997), Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic (1998) Short (1979) Haslem (1968), Short (1979), Bourke (1989), Molyneux and Thornton (1992) Bikker and Hu (2002) and Goddard et al. (2004)]. Given the nature of banking business, the need for risk management is of crucial importance for a bank’s financial health. Risk management is a reflection of the quality of the assets with a bank and availability of liquidity with it. During periods of uncertainty and economic slow down, banks may prefer a more diversified portfolio to avoid adverse selection and may also raise their liquid holdings in order to reduce risk. In this context, both credit and liquidity risk assume importance. The literature provides mixed evidence on the impact of liquidity on profitability. While Molyneux and Thornton (1992) found a negative and significant relationship between the level of liquidity and profitability, Bourke (1989) in contrast, reports an opposite result. One possible reason for the conflicting findings may be the different elasticity of demand for loans in the samples used in the studies (Guru, Staunton and Balashanmugam, 2004). Credit risk is found to have a negative impact on profitability (Miller and Noulas, 1997standard microeconomic profit function. In this context, Bourke (1989) and Molyneux and Thornton (1992) find that better-quality management and profitability go hand in hand. As far as the external determinants of bank profitability are concerned the literature distinguishes between control variables that describe the macroeconomic environment, such as inflation, interest rates and cyclical output, and variables that represent market characteristics. The latter refer to market concentration, industry size and ownership status. Among the external determinants which are empirically modeled are regulation [Jordan (1972); Edwards (1977); Tucillo (1973)], bank size and economies of scale [Benston, Hanweck and Humphrey (1982); Short (1979)], competition [Phillips (1964); Tschoegl (!982)], concentration [Rhoades (1977); Schuster (1984)], growth in market [Short (1979)], interest rates as a proxy for capital scarcity and government ownership (Short, 1979). The most frequently used macroeconomic control variables are the inflation rate, the long-term interest rate and/or the growth rate of money supply. Revell (1979) introduced the issue of the relationship between bank profitability and inflation. He notes that the effect of inflation on bank profitability depends on whether banks’ wages and other operating expenses increase at a faster pace than inflation. Perry (1992) in a similar vein contends that the extent to which inflation affects bank profitability depends on whether inflation expectations are fully anticipated. The influence arising from ownership status of a bank on its profitability is another much debated and frequently visited issue in the literature. The proposition that privately owned institutions are more profitable, however, has mixed empirical evidence in favour of it. For instance, while Short (1979) provides cross-country evidence of a strong negative relationship between government ownership and bank profitability, Barth et al. (2004) claim that government ownership of banks is indeed negatively correlated with bank efficiency. Furthermore, Bourke (1989) and Molyneux and Thornton (1992) find ownership status is irrelevant in explaining profitability. While many of the above factors would be relevant, it would be instructive to scan the literature that has exclusively focussed on the RRBs.). This result may be explained by taking into account the fact that more the financial institutions are exposed to high-risk loans, the higher is the accumulation of unpaid loans implying that these loan losses have produced lower returns to many commercial banks (Athanasoglou, Brissimis and Delis, 2005). Some of the other internal determinants found in the literature are funds source management and funds use management (Haslam, 1968), capital and liquidity ratios, the credit-deposit ratio and loan loss expenses [Short (1979); Bell and Murphy (1969); Kwast and Rose (1982)]. Expense management, a correlate of efficient management is another very important determinant of bank’s profitability. There has been an extensive literature based on the idea that an expenses-related variable should be included in the cost part of a The literature on RRBs recognises a host of reasons responsible for their poor financial health. According to the Narasimham Committee, RRBs have low earning capacity. They have not been able to earn much profit in view of their policy of restricting their operations to target groups. The recovery position of RRBs is not satisfactory. There are a large number of defaulters. Their cost of operation has been high on account of the increase in the salary scales of the employees in line with the salary structure of the employees of commercial banks. In most cases, these banks followed the same methods of operation and procedures as followed by commercial banks. Therefore, these procedures have not found favour with the rural masses. In many cases, banks have not been located at the right place. For instance, the sponsoring banks are also running their branches in the same areas where RRBs are operating. The issue whether location matters for the performance has been addressed in some detail by Malhotra (2002). Considering 22 different parameters that impact on the functioning of RRBs for the year 2000, Malhotra asserts that geographical location of RRBs is not the limiting factor for their performance. He further finds that ‘it is the specific nourishment which each RRB receives from its sponsor bank, is cardinal to its performance’. In other words, the umbilical cord had its effect on the performance of RRBs. The limitation of the study is that the financial health of the sponsor bank was not considered directly to infer about the umbilical cord hypothesis. Nitin and Thorat (2004) on a different note provide a penetrating analysis as to how constraints in the institutional dimension5 have seriously impaired the governance of the RRBs. They have argued that perverse institutional arrangements that gave rise to incompatible incentive structures for key stakeholders such as political leaders, policy makers, bank staff and clients have acted as constraints on their performance. The lacklustre performance of the RRBs during the last two decades, according to the authors can be largely attributed to their lack of commercial orientation. An appropriate restructuring strategy would require to identify the problems leading to the non-satisfactory performance of the RRBs. The performance of the RRBs under the aegis of their sponsor banks in the spatial dimension has been dealt in some detail in Section III. Section III The RRBs, over the years have made impressive strides on various business indicators. For instance, deposits of RRBs have grown by 18 times and advances by 13 times between 1980 and 1990. Between 1990 and 2004, deposits and advances grew by 14 times and 7 times, respectively (Table 1). Between the year 2000 and 2004, loans disbursed by RRBs more than doubled reflecting the efforts taken by the banks6 to improve credit flow to the rural sector. The average per branch advances also increased from Rs.25 lakh in March 1990 to Rs.154 lakh in March 2003. When one considers the deployment of credit relative to the mobilisation of resources, the credit-deposit (C-D) ratio of RRBs were more than 100 per cent during the first decade of their operations up to 1987. Though the C-D ratio subsequently became lower, of late, it has shown an improvement and went up from around 39 per cent in March 2000 to 44.5 per cent in March 20047 .

The presence of RRBs shows wide variation both across States and sponsor banks.

Although RRBs are spread over twenty-six States, they have most of their presence

in seven States, i.e., Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh,

Maharastra, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh has the highest number

of RRBs, i.e., thirty-six and Kerala has got only two amongst the major

States of the country (Table 2). The north-eastern States

like Manipur, Meghalya, Mizoram and Nagaland have got only one RRB. Like-wise,

seven sponsor banks amongst twenty-eight, viz., Bank of Baroda, Bank

of India, Central Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, State Bank of India, United

Bank of India and UCO bankaccount for more than three fifths of the RRBs. More

than 160 RRBs earned profit in March 2004 while 150 RRBs were found to be earning

profits for three consecutive years beginning with the year 2000-01. More than

half of these loss-making RRBs are found to be operating in four States, i.e.,

Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharastra and Orissa. Seen at the level of sponsor banks,

three banks, i.e., Bank of India, Central Bank of India and State Bank

of India accounted for more than half of the loss making RRBs. As a

number of sponsor banks have promoted RRBs in more than one State, it becomes

natural to ask whether the presence of RRBs sponsored by a few banks whose area

of operation is confined to some specific States is camouflaging the performance

of better run RRBs. There can be three possibilities in such a situation. One,

irrespective of the State, the RRBs sponsored by some banks are incurring losses;

second, irrespective of sponsor banks, certain States are simply not conducive

to better performance for RRBs; and third, there is nothing inherent either with

a sponsor bank or a particular State in which the RRBs operate to contribute towards

the performance of RRBs and it is a combination of some other factors. To answer

these possibilities, one needs to assess the presence of RRBs sponsored by different

banks across the States and their performance. Such an attempt is made in Table

3 where performance of sponsor banks across regions is depicted.

sponsored by the Central Bank of India and one each by the Punjab National Bank, SBI and the UCO bank. Of the five-loss making RRBs found in Madhya Pradesh, two are sponsored by Bank of Baroda and one each by the Bank of India, the Central Bank of India and the UCO Bank. Like wise, of the five-loss making RRBs found in Maharastra, three are sponsored by Bank of India and two by Bank of Maharastra. From the sponsor bank’s perspective one finds that the RRBs in which they have a stake and which are not earning profits, are not confined to a single State. It is spread across the States in which they have a presence. For instance, the eight loss making RRBs for which the Central Bank of India is the sponsor bank, are spread over Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Similarly, the twelve loss making RRBs sponsored by the SBI are spread across Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Nagaland and Orissa. The same is the case with the RRBs sponsored by Bank of India and UCO bank. Hence, one finds no strong systematic pattern so as to infer whether or not the peculiarities of any particular sponsor bank or a specific State in which they operate drives the performance of RRBs. In such a situation, financial performance of the RRBs has been modeled based on balance sheet information of the RRBs for a ten-year period to decipher, what all factors that contribute to their financial health. The modalities of the econometric estimation have been taken up in the next section. Section IV Data and Methodology Net income as a percentage to total assets (NITA)8 is taken

to be the indicator of financial performance of the RRBs. NITA measures how profitably

and efficiently the RRB is making use of its total assets. Deflating the net income

by total assets also takes account of the variation in the absolute magnitude

of the profits, which may be size related. The performance of RRBs is postulated

to depend upon two broad sets of factors, internal to the RRBs as well as external

to them. The internal factors are represented through the balance sheet information

of the individual RRBs. RRBs are scheduled commercial banks whose source of income

arises primarily from lending and investment. Balance sheet management on

part of RRBs requires a judicious mix between lending and investment. As such,

loans and advances of each RRB as a percentage of total assets (LOTA) and investments

in securities of each RRB as a percentage of total assets (INTA) are included

as explanatory variables. In terms of liquidity management, since banks are involved

in the business of transforming short-term deposits into long-term credit, they

would be constantly faced with the risks associated with the maturity mismatch.

In order to hedge against liquidity deficits, which can lead to insolvency problems,

banks often hold liquid assets, which can be easily converted to cash. However,

liquid assets are often associated with lower rates of return. Hence, high liquidity

is expected to be associated with lower profitability (Molyneux and Thornton,

1992). The impact of liquidity on profitability is captured through the variable

LIQ, which is represented through Cash in Hand of the RRBs as a proportion of

their Assets. Another internal factor that can be expected to have a significant

effect on the financial health of the RRBs is their efficiency in expense management.

The ‘total expenses’ shown in profit & loss account of the RRBs

is the sum of ‘interest expenses’ and ‘operating expenses’.

While rising operating costs to support increasing business activities is natural,

increasing operating costs relative to non operating expenses is a matter of concern

and reflects poor expense management. To judge the impact of expense management

on balance sheet health, the variable operating expenses as a percentage of total

expenditure (OE) has been taken as another independent variable. Where

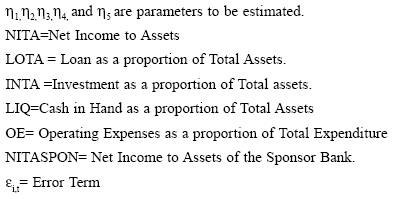

The subscripts i and t refer to the year and cross section (RRB); respectively. In addition to the above factors, an environmental factor that may affect both the costs and revenue of the RRBs is the inflationary conditions in the economy. The impact of inflation rates on bank profitability depends on its effect on a bank’s costs and revenues. The effect of inflation on bank performance depends on whether the inflation is anticipated or unanticipated (Perry, 1992). If inflation is fully anticipated and interest rates are adjusted accordingly resulting in revenues rising faster than costs, then it would have a positive impact on profitability. However, if the inflation is not anticipated and the banks are sluggish in adjusting their interest rates then there is a possibility that bank costs may increase faster than bank revenues and hence, adversely affect bank profitability. Interest rates in India were administered for a long time till the onset of financial liberalization. In the post liberalisation phase though banks have greater freedom to price their products, maneuverability on part of banks in adjusting the interest rates are rather limited on account of the preference for fixed rate deposits, administered savings, etc. Furthermore, as all the variables in (1) are expressed as ratios, inflation is already accounted for in the model. Hence, inflation as an additional variable has been excluded from the regression model. It is quite possible that past year’s performance has a bearing on today’s performance and non-incorporation of the same in the econometric estimation would blur the impact of other variables on NITA. To account for the past year’s performance, lagged value of NITA has also been considered in an extended model. The extended model assumes specification as laid down in equation (2)

Where, ηs are the parameters to be estimated. The extended model (2) is a dynamic panel data model. A dynamic panel model poses a number of econometric issues. The major problem that arises when lagged dependent variable is introduced as an explanatory variable is that the error term and the lagged dependent variable are correlated, with the lagged dependent variable being correlated with the individual specific effects that are subsumed into the error term. This implies that standard estimators are biased, and as such an alternative method of estimating such models is required. The standard procedure to provide consistent estimates is to adopt an instrumental variable procedure, with different lags of the dependent variable used as instruments. Although a number of candidates are possible, the Arellano and Bover (1995) approach is adopted as this generates the most efficient estimates. While using lagged dependent variables as instruments, overall instrument validity is examined using a Sargan test of over identifying restrictions. The study covers the period 1994-2003. The choice of end points for the period of analysis is essentially governed by two considerations. Based on the recommendations of the Narasimham Committee Report (1992), reforms were initiated in 1993 to turn around the failing RRBs. To enhance financial viability, a new set of prudential accounting norms of income recognition, asset classification, provisioning, and capital adequacy were implemented. Banks were also required to make full provisioning for bulk of their non-performing assets. Furthermore, they were permitted to lend to non-target group borrowers up to 60 per cent of new loans beginning in 1993-94. Permission was also granted to introduce new services, such as loans for consumer durables. As such, year 1993-94 has been taken as the initial year for estimation when the RRBs were given the opportunity to operate in a more liberal framework. The choice of the terminal year for the empirical study is guided by the availability of balance sheet information on both RRBs as well as the sponsor bank from the various issues of Statistical Tables Relating to Banks in India brought out by the Reserve Bank of India. Balance sheet information was available till 2002-03 for RRBs when the study was carried out. The study deals with all the 196 RRBs except one10 . To get a deeper insight into the factors contributing to the financial performance of RRBs, the empirical analysis has been carried out separately for the profit and the loss making RRBs apart from for all the RRBs taken together. Those RRBs that earned profits consecutively for three years during 2000-01 till 2002-03 have been categorized as the profit making RRBs and the rest as loss making RRBs. Section V Empirical Results To choose the appropriate model for estimating specification (1), Hausman test is employed. The very low p-value obtained for Hausman Statistics indicates a preference for fixed effects over random effect model. The fixed effect estimation results indicate that investments contributed positively to net income of both profit and loss making RRBs. On the other hand, advances had a positive impact on the financial health of the profit making RRBs only; the impact is found to be negative, although insignificant, for the loss making

RRBs. Liquidity also turned out to be insignificant in the statistical sense to affect the net income of any category of RRBs. Operating expenses have an across-the-board negative and significant impact on the RRBs’ financial performance. Furthermore, sponsor bank’s health turns out to be insignificant in having an impact on the concerned RRBs irrespective of whether it is making profits or incurring losses. Thus, going by the fixed effect estimation results, the umbilical cord hypothesis appears to be on a weak footing. However, estimation of the extended model (2), which employs more rigorous estimation procedures, provides strikingly different results (Table 5). The dynamic panel data estimation reveals that performance in the past years had a significant11 impact for the current year for both categories of RRBs. Advances contributed negatively

to the health of the profit making RRBs. This is in contrast to the fixed effects estimation result where advances had a positive impact for the profit making RRBs. For the loss making RRBs, the negative and insignificant coefficient for advances in the fixed effects estimations turns out to be positive and significant in the dynamic model. For all RRBs taken together, advances are found to adversely affect the bottom line. As far as investments are concerned, they contributed positively and significantly to the performance of the profit making RRBs. Again in sharp contrast to the fixed effects results, investments seem to be inconsequential in influencing the bottom line of loss making RRBs. For all RRBs taken together, impact of investments turns out to be positive and significant. The relative importance attached to investment vis-a-vis advances in their portfolio management by the profit and loss making RRBs, can be seen from Chart 1, which depicts yearly average figures. As can be seen from Chart 1, investments over the years have assumed increasing importance in the asset portfolio of profit making RRBs. Income from investments relative to advances has also contributed a higher proportion to income for profit making RRBs in the recent years compared to the loss making ones (Chart 1). For instance, investment income in total income while increased from 6 per cent to 9 per cent for the loss making RRBs, it increased from 2 per cent to 14 per cent for the profit making RRBs between the period 1994-99 and 2000- 03.

Compared to the period 1994-99, there has been a relative shift towards investments

in the portfolio management of both profit and loss making RRBs during the period

2000-03. The shifting away from advances, however, has been sharper for the profit

making RRBs. While the proportion of loans to assets declined from 41.5 percent

to 35 per cent for the loss making RRBs, the decline was more pronounced from

59 per cent to 48 per cent for the profit making RRBs over the sub periods 1994-99

and 2000-03. Section VI Conclusion The

study made an attempt to examine whether the problems associated with the RRBs

are specific to certain sponsor banks or States in which they operate. To get

a deeper insight, all the RRBs were categorised either as profit making or loss

making ones. RRB earning profits consecutively for the past three years from the

terminal year of the study have been classified as profit making and the rest

as loss making. Such a classification led to 150 RRBs falling in the profit making

category and rest 46 as loss making. The exploratory analysis revealed that the

problem of the loss making RRBs is neither confined to some specific States nor

to a group of sponsor banks. In the absence of any strong systematic pattern so

as to suggest that the performance of RRBs is driven by the peculiarities of any

particular sponsor Bank or a specific State in which they operate, econometric

estimation was employed so as to decipher the factors that contribute to their

financial health. Based on the balance sheet information on individual RRBs for

the past ten years, this study has approached the issue primarily form the asset

side of the RRBs balance sheet. Given the linkage between the RRBs and their sponsor

bank, an attempt was also made to infer whether or not the umbilical cord hypothesis

is operational. Both fixed effect and panel GMM estimations were carried out.

The more appropriate GMM estimation results indicated that the loan portfolio

management for the profit making RRBs is an area of concern. Investments

contribute positively to the financial performance of the profit making RRBs.

Advances while had a positive impact, investments, however, turned out to be inconsequential

for the performance of loss making RRBs. The results further indicated that the

umbilical cord hypothesis is operational. The sponsor bank contributes positively

to the financial health of the profit making RRBs. For the loss making RRBs, the

sponsor bank acts as a drag on their performance. The income from investments

coupled with synergy from the sponsor bank’s association could mitigate

the negative impact flowing from the loan portfolio for the profit making RRBs.

The loss making RRBs on the other hand, could have done better had the sponsor

banks played a proactive role, especially in their investment portfolio management.

The loss making RRBs need focused attention of the all the stake holders, in general,

and of the sponsor bank, in particular, so as to transform them into profitable

ventures. In view of the intricacies involved, some critical thinking is called

for at the policy level in restructuring the loss making RRBs are concerned. The

sponsor bank for the loss making RRBs could be given a time frame and if within

this period, significant improvement is not made, the possibility of changing

the sponsor bank as suggested by the Sardesai Committee may be a worthwhile option. 1. RRBs were

established “with a view to developing the rural economy by providing, for

the purpose of development of agriculture, trade, commerce, industry and other

productive activities in the rural areas, credit and other facilities, particularly

to small and marginal farmers, agricultural labourers, artisans and small entrepreneurs,

and for matters connected therewith and incidental thereto”(RRBs Act, 1976). References Akhavein,

J.D., Berger, A.N., Humphrey, D.B. (1997): “The Effects of Megamergers on

Efficiency and Prices: Evidence from a Bank Profit Function”, Finance

and Economic Discussion Series 9, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System. Arellano, M., and Bover, O. (1995): “Another

Look at the Instrumental Variables Estimation of Error Components Models,”

Journal of Econometrics, 68, pp.29–51. Athanasoglou

Panayiotis P., Brissimis Sophocles N. and Delis Matthaios D. (2005): “Bank-

Specific, Industry-Specific and Macroeconomic Determinants of Bank Profitability”,

Bank of Greece Working Paper No. 25. Balachandher

K G, John Staunton and Balashanmugam (2004): “Determinants of Commercial

Bank Profitability in Malaysia” Papers presented at the 12th Annual

Australian Conference on Finance and Banking. Benston,

George J., Gerald A. Hanweck and David B. Humphrey (1982): “Scale Economies

in Banking”, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol.XIV, No.

4, part 1, November. Bikker, J.A., Hu, H. (2002): “Cyclical

Patterns in Profits, Provisioning and Lending of Banks and Procyclicality of the

New Basel Capital Requirements”, BNL Quarterly Review, 221, pp.143-175. Bell Frederick W. and Nell Mushy (1969): “Impact of

Market Structure on the Price of a Commercial Banking Service”, The

Review of Economics and Statistics, May. Bose, Sukanya

(2005): “Regional Rural Banks: The Past and the Present Debate”, Macro

Scan, URL: http://www.macroscan.com/fet/jul05/ fet200705RRB_Debate.htm. Bourke, P. (1989): “Concentration and other Determinants

of Bank Profitability in Europe, North America and Australia”, Journal

of Banking and Finance, Vol.13, pp. 65-79. Consideration

of the Regional Rural Banks (Amendment) Bill, 2004, Das

Prasant (2000): “Sustainability Through Outreach - The Malbar Lighthouse

Shows the Way.” National Seminar on Best Practices in RRBs,BIRD,

Lucknow. Demirguc-Kunt, A., Huizinga, H. (2000): “Financial

Structure and Bank Profitability”, World Bank, Mimeo. Edwards. Franklin

R. (1977): “Managerial Objectives in Regulated Industries: Expense Preference

Behavior inBanking”, Journal of Political Economy, February. Goddard, J., Molyneux, P., Wilson, J.O.S. (2004): “The

Profitability of European Banks: A Cross-Sectional and Dynamic Panel Analysis”,

Manchester School 72 (3), pp.363- 381. Haslem,

John (1968): “A Statistical Analysis of the Relative Profitability of Commercial

Banks”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 23, pp.167-176. Hausman,

Jerry A. (1978): “Specification Tests in Econometrics,” Econometrica,

46, pp.1251–1272. Joshi V.C. and Joshi V.V. (2002):

“Managing Indian Banks”, Response Books, New Delhi. Kannan,

R (2004), ”Regional Rural Banks”, URL: http:// www.geocities.com/learning/banking2/rrb.html Kwast, Myron L. and John T. Rose (1982), “ Pricing,

Operating Efficiency and Profitability Among Large Commercial Banks”,

Journal of Banking and Finance,Vol.6. Malhotra, Rakesh

(2002): “Performance of India’s Regional Rural Banks (RRBs): Effect

of the Umbilical Cord”. URL: http://www.alternative-finance.org.uk/rtf/rrbsmalhotra.rtf. Miller, S.M., Noulas, A.G. (1997): “Portfolio Mix and

Large-bank Profitability in the USA”, Applied Economics, 29 (4),

pp.505-512. Mohan Jagan (2004): “Regional Rural

Banks Need a Shot in the Arm”, Financial Daily from The Hindu Group

of Publications. March 19th Edition. Molyneux, P.,

Thornton, J. (1992): “Determinants of European Bank profitability: A Note”,

Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol.16, pp.1173-1178. Nitin

Bhatt and Thorat Y. S. P. (2004): “India’s Regional Rural Banks: The

Institutional Dimension of Reforms”, National Bank News Review, NABARD,

April-September. Neely, M.C., Wheelock, D.C. (1997),

“Why Does Bank Performance Vary Across States? Review”, Federal

Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Vol 79, No. 2, pp. 27-40. Perry,

P., (1992): “Do Banks Gain or Lose from Inflation”, Journal of

Retail Banking, 14(2), pp.25-30. Reddy,

Y.V. (2000): “Rural Credit: Status and Agenda”, Reserve Bank of

India Bulletin, November. Reserve Bank of India (2004): “Report of the Advisory

Committee on Flow of Credit to Agriculture and Related Activities From the Banking

System”. URL: (www.rbi.org.in). Reserve

Bank of India (2005): “Report of the Internal Working Group on

RRBs”, Chairman: A.V. Sardesai, Mumbai. URL: (www.rbi.org.in). Reserve Bank of India (2002): “Annual Accounts of

Scheduled Commercial Banks in India (1989-2001)”,Mumbai. URL: (www.rbi.org.in). Revell, J., (1979): “Inflation and Financial Institutions”,

Financial Times, London. Rhoades, Stephen A.1977):

“Structure and Performance Studies in Banking: A Summary and Evaluation”,

Staff Economics Studies 92, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC. Schuster, Leo (1984): “Profitability and Market Share

of Banks”, Journal of Bank Research, Spring. Shaffer,

S. (1994): “Bank Competition in Concentrated Markets”, Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Business Review, March/April, pp.3-16. Shaffer, S. (2004): “Comment on “What Drives Bank

Competition? Some International Evidence” by Stijn Claessens and Luc Laeven,

Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol.36, pp.585-592. Sharma

K.C; Josh P.; Mishra J.C.; Kumar Sanjay; Amalorpavanathan R.and Bhaskran R. (2001):

“Recovery Management in Rural Credit”, Occasional Paper,

No. 21, NABARD, Mumbai. Short, Brock (1977): “Bank

Concentration, Market Size and Performance: Some Evidence From Outside the United

States”, Mimeo, IMF, Washington, DC. Short, B.K.

(1979): “The Relation Between Commercial Bank Profit Rates and Banking Concentration

in Canada, Western Europe and Japan”, Journal of Banking and Finance,

Vol.3, pp.209-219. Smirlock, M. (1985): “Evidence

on the (non) Relationship Between Concentration and Profitability in Banking”,

Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol. 17, pp. 69-83. Staikouras,

C., Steliaros, M. (1999): “Factors That Determine the Profitability of the

Greek Financial Institutions”. Hellenic Bank Association, 19, pp.61-66. Statistical Tables Relating to Banks in India (Various

Issues), Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai. URL: (www.rbi.org.in) Velayudham, T. K., and Sankaranarayanan, V.

(1990): “Regional Rural Banks and Rural Credit: Some Issues”, Economic

and Political Weekly, September 22, pp.2157-2164. Tschoegi, Adrian E. (1983): “Size, Growth and Transnationality Among the World’s Largest Banks”, Journal of Business, 56, No. 2. Annex-1

* Research Officer in the Department of Economic Analysis and Policy, Reserve Bank of India and presently working from the Patna office of the Bank. The views expressed here are of the author and not necessarily of the institution to which he belongs. Discussions with Shri S.S.Mishra have been enlightening for the author. The author would like to thank an anonymous referee for valuable suggestions. The author gratefully acknowledges the encouragement and inspirations of Dr. Narendra Jadhav, Dr. R.K.Pattnaik and Shri S. Ganesh. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

पेज अंतिम अपडेट तारीख: