IST,

IST,

VIII. Financial Market Integration

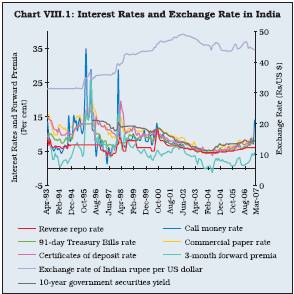

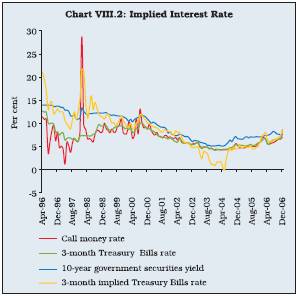

8.1 Integration of financial markets is a process of unifying markets and enabling convergence of risk-adjusted returns on the assets of similar maturity across the markets. The process of integration is facilitated by an unimpeded access of participants to various market segments. Financial markets all over the world have witnessed growing integration within as well as across boundaries, spurred by deregulation, globalisation and advances in information technology. Central banks in various parts of the world have made concerted efforts to develop financial markets, especially after the experience of several financial crises in the 1990s. As may be expected, financial markets tend to be better integrated in developed countries. At the same time, deregulation in emerging market economies (EMEs) has led to removal of restrictions on pricing of various financial assets, which is one of the pre-requisites for market integration. Capital has become more mobile across national boundaries as nations are increasingly relying on savings of other nations to supplement the domestic savings. Technological developments in electronic payment and communication systems have substantially reduced the arbitrage opportunities across financial centres, thereby aiding the cross border mobility of funds. Changes in the operating framework of monetary policy, with a shift in emphasis from quantitative controls to price-based instruments such as the short-term policy interest rate, brought about changes in the term structure of interest rates. This has contributed to the integration of various financial market segments. Harmonisation of prudential regulations in line with international best practices, by enabling competitive pricing of products, has also strengthened the market integration process. 8.7 Financial market integration at the theoretical level has been postulated in several ways. The most popular economic principles of financial integration include the law of one price, term structure of interest rates, parity conditions such as purchasing power parity, covered and uncovered interest parity conditions, capital asset price model, arbitrage price theory and Black-Scholes’ principle of pricing derivatives (Box VIII.1). Dimensions of Financial Market Integration 8.8 Broadly, financial market integration occurs in three dimensions, nationally, regionally and globally (Reddy, 2002 and BIS, 2006). From an alternative perspective, financial market integration could take place horizontally and vertically. In the horizontal integration, inter-linkages occur among domestic financial market segments, while vertical integration occurs between domestic markets and international/ regional financial markets (USAID, 1998). Box VIII.1 The law of one price (LOOP), pioneered by Augustin Cournot (1927) and Alfred Marshall (1930), constitutes the fundamental principle underlying financial market integration. According to the LOOP, in the absence of administrative and informational barriers, risk-adjusted returns on identical assets should be comparable across markets. While the LOOP provides a generalised framework for financial market integration, finance literature provides alternative principles, which establish operational linkages among different financial market segments. First, the term structure of interest rates, deriving from paradigms of unbiased expectations, liquidity preference, and market segmentation, establishes integration across the maturity spectrum, i.e., short, medium and long ends of the financial market (Blinder, 2004). Usually, the term structure is applied to a particular instrument such as the risk free government securities. In the monetary economics literature, it is recognised that the term structure of interest rate contains useful information about future paths of inflation and growth, which characterise the objective function of policy in most countries. Second, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) of Nobel laureate, William Sharpe (1964) is used widely for valuing systematic risk to financial assets. The CAPM establishes linkage between market instruments and risk free instruments such as government securities. The CAPM envisages a simplified world with no taxes and transaction costs, and identical investors. In such a world, super-efficient portfolio must be the market portfolio (Tobin, 1958). All investors will hold the market portfolio; leveraging or de-leveraging would be driven by the risk-free asset in order to achieve a desired level of risk and return. Third, the Black-Scholes’ principle of option pricing postulates linkage between derivative products on the one hand, and cash/spot market of underlying assets on the other. The often quoted put-call parity principle in finance theory states that in the absence of arbitrage opportunities, a derivative instrument can be replicated in terms of spot price of an underlying asset, coupled with some borrowing or lending activity. The forward-spot parity relation is used widely for analysing linkages between foreign exchange forwards and the money market instruments. Beyond economic and financial principles, financial markets integration could also occur due to information efficiency as economic agents form expectations about the future course of policy and real sector developments. For instance, even if transactions between residents and non-residents and between markets and intermediaries remain incomplete or limited due to regulatory barriers, participants could form expectation that such restrictions would not continue for long with a shift in policy regime towards greater opening and liberalisation of markets over time. Measures of Financial Integration 8.12 The progress of domestic, global and regional financial integration could be measured using a number of approaches. Generally, these measures are pided into three categories: institutional/regulatory measures, quantity and price based measures. From a policy perspective, specific indicators of financial integration could be classified into de jure and de facto measures. The existence of legal restrictions on trade and capital flows across border as well as market segments is the most frequently used de jure indicators. However, these indicators have several shortcomings as restrictions may not be binding, or they are not respected because capital flows would not exist somehow. They may not cover a specific aspect of all possible impediments to financial integration (Prasad et al., 2006). Moreover, in practice, de jure indicators adopting a dichotomous scheme of the existence or absence of restrictions may not reveal actual degree of openness of countries to capital flows. 8.14 Liquidity and turnover data are used as quantitative indicators for measuring inter-linkages among domestic financial market segments. For global integration, capital flows indicate whether a country is becoming more or less financially integrated over time. In this context, gross capital flows are a among various interest rates, tests of common trend in the term structure of interest rates and volatility transmission. From a policy perspective, interest rate spreads between the official short-term rate and a benchmark short-term market instrument on the one hand, and various other market interest rates on the other, are used for measuring price convergence and effectiveness of policy. Price-related measures also include covered and uncovered interest rate parity as well as asset price correlations between countries. There are, however, serious practical problems in using prices to measure global or regional financial integration, particularly in emerging markets. This is because prices may move together because of a common external factor or because of similar macroeconomic fundamentals and not because of market integration. Moreover, prices may be affected by differences in currency, credit and liquidity risks, implying different price movements even if there is a substantial degree of financial integration (Prasad et al., 2006). Box VIII.2 The benefits of global integration depend on size, composition, and quality of capital flows. Global financial integration involves direct and indirect or collateral benefits (Prasad et al,. 2006). Analytical arguments supporting financial openness revolve around main considerations such as the benefits of international risk sharing for consumption smoothing, the positive impact of capital flows on domestic investment and growth, enhanced macroeconomic discipline and increased efficiency as well as greater stability of the domestic financial system associated with financial openness (Agenor, 2001). International financial integration could positively affect total factor productivity (Levine, 2001). Financial openness may increase the depth and breadth of domestic financial markets and lead to an increase in the degree of efficiency of the financial intermediation process by lowering costs and excessive profits associated with monopolistic and cartelised markets, thereby lowering the cost of investment and improving the resource allocation (Levine, 1996; Caprio and Honhan, 1999). Empirical studies on international integration offer mixed perspectives on the benefits of financial integration. The cumulative growth performance of emerging markets, excluding China and India, appears less spectacular than usually perceived under globalisation (Prasad et al., 2006). Financial market integration also poses some risks and entails costs. A major risk is that of contagion, which was evident in the case of East Asian crisis. There are two channels through which the contagion normally works. One, the real channel, which relates to potential for ‘domino effects’ through real exposures on participants operating in other segments. Two, the information channel which relates to contagious withdrawals due to lack of accurate and timely information. Increased domestic and international integration accentuates the risk of contagion as problems in one market segment are likely to be transmitted to other markets with the potential to cause systemic instability. 8.17 There is growing realisation that unlike trade integration, where benefits to all countries are demonstrable, in the case of financial integration, a ‘threshold’ in terms of preparedness and resilience of the economy is important for a country to get full benefits (Kose et al., 2006). A judgemental view needs to be taken whether and when a country has reached the ‘threshold’. The nature of optimal integration is highly country-specific and contextual. Financial integration needs to be approached cautiously, preferably within the framework of a plausible roadmap that is drawn up embodying the country-specific context and institutional features. On balance, there appears to be a greater advantage in well-managed and appropriate integration into the global process, which implies not large-scale but more effective interventions by the authorities. In fact, markets do not and cannot exist in a vacuum, i.e., without some externally imposed rules and such order is a result of public policy (Reddy, 2006b). Thus, with a view to enhancing financial sector efficiency, it is necessary not only to foster competition among institutions but also to develop a system that facilitates transparent and symmetric dissemination of maximum information to the markets. 8.18 Until the early 1990s, India’s financial sector was tightly controlled. Interest rates in all market segments were administered. The flow of funds between various market segments was restricted by extensive micro-regulations. There were also restrictions on participants operating in different market segments. Banks remained captive subscribers to government securities under statutory arrangements. The secondary market of government securities was dormant. In the equity market, new equity issues were governed by several complex regulations and restrictions. The secondary market trading of such equities lacked transparency and depth. The foreign exchange market remained extremely shallow as most transactions were governed by inflexible and low limits under exchange regulation and prior approval requirements. The exchange rate was linked to a basket of currencies. Although the financial sector grew considerably in the regulated environment, it could not achieve the desired level of efficiency. Compartmentalisation of activities of different types of financial intermediaries eliminated the scope for competition among existing financial intermediaries (Mohan, 2004b). 8.20 Broadly, India’s domestic financial market comprises the money market, the credit market, the government securities market, the equity market, the corporate debt market and the foreign exchange market, each of which has been addressed at length in the previous chapters. The channels of integration among various market segments differ. For instance, the Indian money and the foreign exchange markets are intrinsically linked in view of the presence of commercial banks’ and the short-term nature of both markets. The linkage is established through various channels such as banks borrowing in overseas Box VIII.3 Broadly, integration of financial markets in India has been facilitated by various measures in the form of free pricing, widening of participation base in markets, introduction of new instruments and improvements in payment and settlement infrastructure. Free Pricing • Free pricing in financial markets was facilitated by various measures. These include, inter alia, freedom to banks to decide interest rate on deposits and credit; withdrawal of a ceiling of 10 per cent on call money rate imposed by the Indian Banks’ Association in 1989; replacement of administered interest rates on government securities by an auction system; abolition of the system of ad hoc Treasury Bills in April 1997 and replacement by the system of Ways and Means Advances (WMAs) with effect from April 1, 1997; shift in the exchange rate regime from a single-currency fixed-exchange rate system to a market-determined floating exchange rate regime; gradual liberalisation of the capital account in line with the recommendations of the Committee on Capital Account Convertibility (Chairman: Shri S. S. Tarapore) (see Chapter VI on Foreign Exchange Market); and freedom to banks to determine interest rates (subject to a ceiling) and maturity period of Foreign Currency Non-Resident (FCNR) deposits (not exceeding three years); and to use derivative products for hedging risk. Widening Participation • Enhanced presence of foreign banks, in line with India’s commitment to the World Trade Organisation under GATS, strengthened domestic and international markets inter-linkages, apart from increasing competition. New Instruments • Repurchase agreement (repo) was introduced as a tool of short-term liquidity adjustment. The liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) is open to banks and primary dealers. The LAF has emerged as a tool for both liquidity management and also signalling device for interest rates in the overnight market. Several new financial instruments such as inter-bank participation certificates (1988), certificates of deposit (June 1989), commercial paper (January 1990) and repos (December 1992) were introduced. Collateralised borrowing and lending obligation (CBLO) and market repos have also emerged as money market instruments. Institutional Measures • Institutions such as Discount and Finance House of India (DFHI), Securities Trading Corporation of India (STCI) and PDs were allowed to participate in more than one market, thus strengthening the market inter-linkages. Technology, Payment and Settlement Infrastructure • The Delivery-versus-Payment system (DvP), the Negotiated Dealing System (NDS) and subsequently, the advanced Negotiated Dealing System – Order Matching (NDS-OM) trading module and the real time gross settlement system (RTGS) have brought about immense benefits in facilitating transactions and improving the settlement process, which have helped in the integration of markets. Phases of Market Integration in India 8.21 Various segments of financial markets have become better integrated in the reform period, especially from the mid-1990s (Chart VIII.1). As reforms in the financial markets progressed, linkages amongst various segments of market and between domestic and international markets improved. For the purpose of analysis, financial market linkages could be pided into two distinct phases. The first phase refers to the early transition period of the 1990s and the second phase is the period of relative stability in the financial markets from 2000 onwards. 8.22 In the first phase, domestic financial markets witnessed modest integration. Financial markets, in general, lacked depth as measured by the turnover in various market segments (Table 8.1). Domestic financial markets during this phase witnessed easing of various restrictions, which created enabling conditions for increased inter-linkages amongst market segments. The institution of a market-based exchange rate mechanism in March 1993 and transition to current account convertibility in August 1994 facilitated inter-linkages between the money and the foreign exchange markets. Since the beginning of second half of the 1990s, some episodes of volatility were witnessed in the money and the foreign exchange markets, which underscored the gradual integration of the domestic money market and the foreign exchange market. 8.23 Financial markets in India felt the initial impulses of the contagion from financial crises in the East Asian countries, which erupted in the second half of 1997-98. Pressures from contagion re-emerged in the mid-November 1997, following the weakening of the sentiment in response to financial crisis spreading to hit South Korea and far off Latin American markets. The East Asian crisis necessitated policy action by the Reserve Bank to mitigate excess demand conditions in the foreign exchange market. It also moved to siphon off excess liquidity from the system in order to reduce the scope for arbitrage between the easy money market and the volatile foreign exchange market. Foreign currency operations were undertaken in the third quarter of 1997-98 to curb volatility in the exchange rate. This helped in maintaining stability in the exchange rate of the rupee, but resulted in reduced money market support to the government borrowing, leading to an increase in the Centre’s monetised deficit. The Reserve Bank tightened its monetary policy stance by raising the CRR and the Bank Rate, thus, substituting cheap discretionary liquidity with expensive discretionary liquidity. A host of monetary policy actions were taken to tighten liquidity in November and December 1997 and January 1998.1 Monetary policy tightening measures in the wake of East Asian crisis led to hardening of domestic interest rates across various segments in the money market and the government securities market, especially at the short-end. Restoration of stability in the domestic financial markets in the second half of 1998, especially in the foreign exchange market, led the Reserve Bank to ease some of the monetary policy tightening measures undertaken earlier. Several banks reduced their lending and deposit rates in response to the Bank Rate cut as also in line with seasonal trends. 8.24 The second phase, beginning 2000 onwards, reflects the period of broad stability in financial markets with intermittent episodes of volatility. The process of financial market integration was more pronounced during this phase. A growing integration between the money, the gilt and the foreign exchange market segments was visible in the convergence of financial prices, within and among various segments and co-movement in interest rates. The capital market exhibited generally isolated behaviour from the other segments of domestic financial markets. However, there was a clear indication of growing cross-border integration as the domestic stock markets declined sharply in line with the sharp decline in international technology stock driven exchanges in 2001. On several other occasions also, the Indian equity markets tended to move in tandem with major international stock markets. 8.25 Growing integration of financial markets beginning 2000 could be gauged from cross correlation among various market interest rates. The correlation structure of interest rates reveals several notable features of integration of specific market segments (Table 8.2). First, in the money market segment, there is evidence of stronger correlation among interest rates in the more recent period 2000-06 than the earlier period 1993-2000, suggesting the impact of policy initiatives undertaken for financial deepening. The enhanced correlation among interest rates also indicates improvement in efficiency in the operations of financial intermediaries trading in different instruments. Second, the high correlation between risk free and liquid instruments such as Treasury Bills, which serve as benchmark instruments, and other market instruments such as certificates of deposit (CDs) and commercial papers (CPs) and forward exchange premia, underlines the efficiency of the price discovery process. Third, the sharp improvement in correlation between the reverse repo rate and money market rates in the recent period implies enhanced effectiveness of monetary policy transmission. Fourth, the high degree of correlation between long-term government bond yield and short-term Treasury Bills rate indicates the significance of term-structure of interest rates in financial markets. Fifth, the correlation between interest rates in money markets and three-month forward premia was significantly high, indicating relatively high horizontal integration. Integration of the foreign exchange market with the money market and the government securities market has facilitated closer co-ordination of monetary and exchange rate policies. The consequences of foreign exchange market intervention are kept in mind in monetary management which includes constant monitoring of the supply of banking system liquidity and an active use of open market operations to adjust liquidity conditions. Sixth, the equity market appears to be segmented with relatively low and negative correlation with money market segments. 1 See Chapter VI for details.

Segment-wise Integration 8.28 For effective market integration, it is essential that there exists a deep secondary market for government securities, which provides a benchmark for valuation of other market instruments, and the turnover of the instruments in both primary and secondary markets is fairly large. The turnover in the secondary segment of government securities market, indicating the depth of this market segment, inter alia, is influenced by some key factors such as monetary policy stance, banks’ SLR holding and credit demand by the private sector. This was evident in the rise in turnover in the secondary market for government securities, fuelled by banks’ excess SLR holding during the period of softening interest rates. In the recent period, following the tightening of policy stance and rise in credit demand, banks have reduced SLR holdings close to the prescribed limit. Reduction in volumes in the secondary segment of government securities in the second half of 2006 was mostly due to rise in interest rates apart from demand side factors. The secondary market turnover has, thus, declined in the recent period (Chart VIII.4). This trend, if persists for long, could affect the depth and yield in this segment and consequently pose some challenges for effective market integration. International evidence suggests that banks tend to rebalance their portfolio and reduce their holding of government securities when interest rates rise. For instance, in the US, the proportion of government securities held by commercial banks in total US government securities declined to 1.6 per cent in 2005 from 5.3 per cent in 2003 when the interest rates rose following increase in the Federal Funds Rate from 1.25 per cent in 2003 to 5.0 per cent in 20052 .

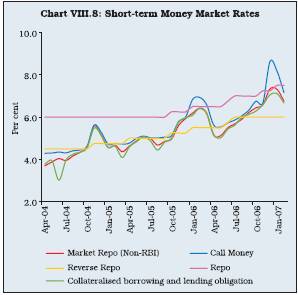

8.29 The integration of the credit market with other money market segments has become more pronounced in recent years. Sustained credit demand has led to higher demand for funds, exerting some pressure on liquidity. This was reflected in the decline in banks’ investment in government securities and higher activity in all the money market segments such as inter-bank call money, collateralised borrowing and lending obligation (CBLO) and market repo rates. Total volume in these three markets increased from Rs.16,132 crore in March 2005 to Rs.35,024 crore in March 2006 and further to Rs.38,484 crore in February 2007. Banks also resorted to increased issuances in the CDs market to meet their liquidity requirements. Outstanding CDs increased from Rs.12,078 crore in March 2005 to Rs.43,568 crore in March 2006 and further to Rs.77,971 crore by March 2, 2007.

Integration of the Foreign Exchange Market 2 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the US. Also, www.bondmarkets.com

8.33 The Uncovered Interest Rate Parity (UIP) implies that ex-ante, expected home currency returns on foreign bonds or deposits in excess of domestic deposits of equal maturity and default risk should be zero. The currency composition of the asset holdings is, therefore, irrelevant in determining relative returns. The prevalence of UIP also implies that the cost of financing for domestic firms in domestic and foreign markets would be the same. Operating through rational expectations, the UIP suggests that expected changes in the nominal exchange rates should approximate the interest rate differentials. In the Indian context, though empirical studies confirm the existence of CIP, they dispute the existence of UIP. Usually, if CIP holds, UIP will also hold if investors are risk-neutral and form their expectations rationally, so that expected depreciation of home currency equals the forward discount (Box VIII.4). 8.34 As alluded to earlier, the equity market has relatively low and negative correlation with other market segments (Table 8.2). The low correlation of the equity market with risk free instruments is indicative of greater volatility of stock returns and the existence of large equity risk premium. The large risk premium occurs when equity price movements cannot be rationalised with standard inter-temporal optimisation models of macroeconomic fundamentals such as consumption and savings (Mehra and Prescott, 1985). This could be on account of different participants in the equity and other financial markets. For instance, the common participation by banks in the money, the government, the foreign exchange and the credit markets ensures fairly high correlation among these segments. The exposure of banks to the capital market remains limited on account of restrictions due to prudential regulation. A major reason for the surge in equity prices could be due to demand-supply mismatches for equity securities. In fact, a large proportion of equities is held by promoters and institutional investors as detailed in Chapter VII. The supply of securities for retail investors could possibly be lagging behind their demand. Equity prices, however, have relatively higher correlation with the forward exchange rate than other market interest rates. This is because portfolio investors, mainly, the FIIs, are allowed to hedge their exposure in the foreign exchange market through the forward market. 8.37 Developed and integrated financial markets are pre-requisites for effective and credible transmission of monetary policy impulses. The success of a monetary policy transmission framework that relies on indirect instruments of monetary management such as interest rates is contingent upon the extent and speed with which changes in the central bank’s policy rate are transmitted to the spectrum of market interest rates and exchange rate in the economy and onward to the real sector (Mohan, 2007). Deviations between money market rates and the policy interest rate, in particular, have at least two adverse effects. First, they weaken the monetary policy transmission mechanism and introduce an element of uncertainty. Greater the influence the central bank has over interest rate levels, the easier it is for it to manage demand in the economy and attain its objective of low inflation and sustained growth (Petursson, 2001). Second, a large spread entailing a mismatch between inter-bank rates and the central bank’s policy rate could lead to inefficiencies in the financial intermediation process. In the Indian context, there has been convergence among market segments, with a significant decline in the spread of market interest rates over the reverse repo rate (Table 8.4). The spread was the lowest for the inter-bank call money rate followed by rates on Treasury Bills, certificates of deposit, commercial paper and 10-year government bond yield. The benefit of financial markets development percolating to the private sector was also evident from the moderation in spread of commercial paper over the policy rate. The narrowing of the spread between the policy rate and other market rates suggests the increasing efficiency of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. 8.38 Besides correlation measure, more formal and robust approach to market integration analysis entails an investigation of causal relationship among various interest rates. The causal relationship between reverse repo rate and market interest rates, in particular, highlights the importance of monetary transmission in influencing the term structure of interest rates. Empirical analysis of Granger causality reveals certain important features of transmission mechanism in the Indian context5. First, lags associated with the transmission of policy impulses to market rates are aligned with the term structure of instruments; short-term rates exhibit relatively lower lags than medium and longer maturity instruments to the changes in policy rates. Second, the reverse repo rate has uni-directional causal effect on short-end of the financial market, including call money rate and 91-day Treasury Bills rate. In the medium-to-longer term horizon, 10-year Government bond yield has a bi-directional causal association with the reverse repo rate. This could be attributed to the feedback between policies and markets, since at the longer end, financial markets contain useful information about investment activity and economic agents’ expectations about inflation and growth prospects. Box VIII.4 In the context of a country’s international financial integration, an important issue is the degree of foreign exchange market efficiency, which can be examined through empirical evaluation of ‘covered interest parity (CIP)’ and ‘uncovered parity (UIP)’ hypotheses. The interest parity hypothesis is important from a policy perspective (Blinder, 2004). First, the CIP reflects information efficiency of the foreign exchange market. Deviations from CIP can arise because of imperfect integration with overseas markets. Second, the UIP could be attributed to effectiveness of sterilised foreign exchange market intervention by central banks as well as that of interest rate defence of the exchange rate. To the extent that UIP is valid, official intervention cannot successfully change the prevailing spot exchange rate relative to the expected future spot rate, unless the authorities allow interest rates to change (Isard, 1995). It may, however, be added that there are other channels (for instance, the signalling channel) through which sterilised intervention may still be effective. Similarly, the interest rate defence of the exchange rate rests on possible deviations from UIP; otherwise, any attempts by the monetary authority to increase interest rates to defend the exchange rate would be offset exactly by expected currency depreciation. Policy-exploitable deviations from UIP are, therefore, a necessary condition for an interest rate defence (Flood and Rose, 2002). In the Indian context, empirical evidence covering the period April 1993 to early 1998 finds some support for CIP but not for UIP (Bhoi and Dhal, 1998; and Joshi and Saggar, 1998). Deriving from theoretical and empirical insights from cross-country studies, Pattnaik, Kapur and Dhal (2003) adopted a rigorous empirical analysis of parity conditions in the Indian context during April 1993 to March 2002. The study reiterated that the overall evidence in favour of market efficiency appears to be inconclusive. While CIP appears to hold on an average, the evidence for UIP comes from the absence of any predictable significant excess foreign exchange market returns. In view of significant ongoing liberalisation of the capital account in the subsequent period, it was attempted to examine afresh the interest parity conditions for India. Accordingly, interest parity conditions for the rupee vis-à-vis the US dollar using monthly data over the period April 1993 to September 2006 with regard to 3-month forward premia were examined. For interest rate differential, two alternative measures of domestic interest rate (call money rate and 91-day Treasury Bills rate) have been used; for the foreign interest rate, 1-month and 3-month LIBOR were used. The results were more or less in line with previous studies4 . Deviations from UIP could not only be due to presence of time varying risk premium but also due to surges in private capital flows (RBI, 2001). Although non-residents have been increasingly permitted to invest in the Indian markets, restrictions on borrowing and investing by residents in the overseas markets remained for most of the sample period of this study. Moreover, even with regard to non-residents, the major players, viz., the foreign institutional investors (FIIs) are more focused on the equity markets. Furthermore, central bank intervention in the market and administrative measures can also affect market behaviour. All these factors can cause deviations from UIP in the short-horizon, but over time there remains a tendency for the exchange rate movements to be consistent with UIP and stable real exchange rate. The average level of interest rate differentials points the right way in forecasting long-run currency changes, even though the short-run correlation usually points the wrong way in forecasting near-term exchange rate changes (Froot and Thaler, 1990). 4 The estimated CIP equations are as follows: FR3 = 1.70 + 0.45 ID1 + 0.25 ID1(-1) + 0.17 ID1(-2)

8.39 As alluded to earlier, market integration could be attributable to liquidity, term structure, credit market conditions, exchange rate and macroeconomic fundamentals. Empirical results reveal that the market integration process is influenced by liquidity, safety and risk, external market developments, private sector growth, credit requirements and macroeconomic developments such as growth and inflation outlook implied by the long-term bond yield6. First, short-term liquidity impact on the inter-bank call money rate is mainly influenced by foreign exchange market developments reflected in the movement of forward exchange rate and fiscal policy induced effect at the short-end of the market through changes in the benchmark 91-day Treasury Bills rate. Second, the rate on 91-day Treasury Bills is influenced by the 10-year government securities yield and private sector credit condition through changes in the commercial paper rate, while foreign exchange market development and liquidity exert some influence in the short-run. Third, forward exchange premia is driven by arbitrage condition, with the inter-bank call money market being the key driver, though some modest impact was due to developments in the private sector (commercial paper) and long-term fundamentals (10-year government bond yield). Fourth, for the private sector, commercial paper is driven by long-term government securities yield in the medium to longer term horizon, while liquidity, risk premium and foreign exchange market condition have modest impact in the shor t-run. Fifth, the commercial paper representing developments in productive activities and credit requirements by the private sector has a substantially larger impact than liquidity, foreign exchange market and risk premium. Moreover, an extension of the above multivariate vector auto-regression(VAR) model to a structural representation reveals that financial market integration in the medium to longer term horizon is induced by the long-term yield on government securities and the commercial paper rate, attributable to macroeconomic developments such as medium-term inflation outlook and real sector developments in the private sector.

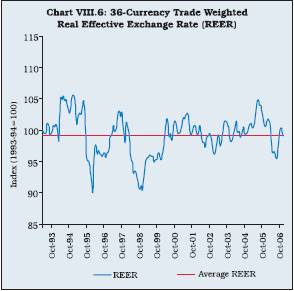

8.39 As alluded to earlier, market integration could be attributable to liquidity, term structure, credit market conditions, exchange rate and macroeconomic fundamentals. Empirical results reveal that the market integration process is influenced by liquidity, safety and risk, external market developments, private sector growth, credit requirements and macroeconomic developments such as growth and inflation outlook implied by the long-term bond yield6. First, short-term liquidity impact on the inter-bank call money rate is mainly influenced by foreign exchange market developments reflected in the movement of forward exchange rate and fiscal policy induced effect at the short-end of the market through changes in the benchmark 91-day Treasury Bills rate. Second, the rate on 91-day Treasury Bills is influenced by the 10-year government securities yield and private sector credit condition through changes in the commercial paper rate, while foreign exchange market development and liquidity exert some influence in the short-run. Third, forward exchange premia is driven by arbitrage condition, with the inter-bank call money market being the ke driver, though some modest impact was due to developments in the private sector (commercial paper) and long-term fundamentals (10-year government bond yield). Fourth, for the private sector, commercial paper is driven by long-term government securities yield in the medium to longer term horizon, while liquidity, risk premium and foreign exchange market condition have modest impact in the shor t-run. Fifth, the commercial paper representing developments in productive activities and credit requirements by the private sector has a substantially larger impact than liquidity, foreign exchange market and risk premium. Moreover, an extension of the above multivariate vector auto-regression(VAR) model to a structural representation reveals that financial market integration in the medium to longer term horizon is induced by the long-term yield on government securities and the commercial paper rate, attributable to macroeconomic developments such as medium-term inflation outlook and real sector developments in the private sector. 8.40 To sum up, integration among various market segments has grown, especially in the recent period. This was reflected in an increase in the depth of the markets and higher correlation among interest rates in various market segments. Growing integration among various financial market segments was accompanied by lower volatility of interest rates. The narrowing of the interest rate spread over the reverse repo rate reflects an improvement in the monetary policy transmission channel and greater financial market integration. Financial market integration reflects a dynamic interaction among various parameters such as liquidity, safety and risk, foreign exchange market development, private sector activity, and macroeconomic fundamentals. Alternatively, financial integration exhibits interaction among financial intermediaries, the Government, the private sector and the external sector. In respect of specific market segments, it was found that the reverse repo rate has one-way causal effect with the short-end of the financial markets, i.e., money market, while with the 10-year government bond yield, a two-way causal relation exists, implying a feedback between policy and markets at the longer end. In the foreign exchange market, the PPP doctrine has been held in the absence of any sustained appreciation/depreciation of the REER. The equity market has a relatively low interaction with other market segments, which is reflected in the existence of a large equity risk premium. 5 Granger causality tests were conducted for the period April 1993 to September 2006 by estimating a vector error correction model (VEC) by taking the following variables: reverse repo rate, 91-day Treasury Bills rate, 364-day Treasury Bills rate and 10-year Government securities yield. The order of the VAR model was chosen to be two months lag based on the Schwarz Criterion. 6 An unrestricted vector auto-regression model was estimated to analyse financial market inter-linkages in terms of interaction among five variables such as the inter-bank call money rate, the 91-day Treasury Bills rate, the three-month forward premia, the commercial paper rate and the 10-year government bond yield. From an alternative perspective, such multivariate dynamics demonstrate the underlying financial and real linkages arising from interaction among intermediaries, the Government, the external sector, the private sector and macroeconomic developments. The model was estimated using monthly data for the period April 1993 to September 2006. The order of the VAR was found to be 9-month lag, based on the Likelihood Ratio test. The forecast error variance decomposition analysis of the VAR model was used for explaining the variation of one variable in terms of variation in other variables in the system.

8.41 Development of financial markets is required for the purpose of not only realising the hidden saving potential and effective monetary policy, but also for expanding the economy’s role and participation in the process of globalisation and regional integration. With growing openness, global factors come to play a greater role in domestic policy formulation, leading to greater financial market integration (Reddy, 2006b). With growing financial globalisation, it is important for emerging market economies such as India to develop financial markets to manage the risks associated with large capital flows. In a globalised world, the importance of a strong and well-regulated financial sector can hardly be overemphasised to deal with capital flows that can be very large and could reverse very quickly. The Report of the Committee on Fuller Capital Account Convertibility, 2006 (Chairman: Shri S.S. Tarapore) observed that in order to make a move towards the fuller capital account convertibility, it needs to be ensured that different market segments are not only well-developed but also that they are well-integrated. 8.42 Globalisation has manifested itself in a new form of trade and financial inter-dependence among industrial, developing and emerging market economies. Developing and emerging economies, which earlier relied mainly on primary commodity exports, have emerged as the leading countries in manufacturing and services trade. Though in absolute terms, industrial countries continue to account for the bulk of global trade, their share has declined in recent years, leading to a rise in the share of developing and emerging market economies led by China and countries in the East and South East Asia. The spreading out of the production process across countries, with companies increasingly finding it profitable to allocate different links of the value chain across a range of countries, has been accompanied by increased market integration. Thus, in terms of trade openness, developing and emerging market economies surpassed advanced economies (Table 8.5). Across income groups, trade openness of low and middle-income countries has increased at a faster rate than high-income countries. 8.43 The major trend in the global economy today alongside globalisation is growing regionalisation. In this context, the issue whether the process of globalisation and the growing regionalism complement each other or the growing regionalism is detrimental to globalisation has become a subject of intense discussion for policy makers and academics. Some believe that globalisation is nothing but a greater integration of economies nationally, regionally and worldwide. For others, since the regional integration process remains concentrated exclusively in certain countries, doubts arise whether such exclusivity throws up building blocks or stumbling blocks on the road to global economic integration. Despite these alternative perspectives, the regionalisation process has accelerated since the mid-1980s with varying features and scale in different regions. According to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), by March 2007, there were 194 regional trade arrangements as compared with only 24 agreements in 1986 and 66 agreements in 1996. According to the World Investment Report, 2006 of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, international investment agreements (IIAs) have increased substantially. At the global level, total number of IIAs was close to 5,500 at the end of 2005, comprising 2,495 bilateral investment treaties (BITs), 2,758 double taxation treaties (DTTs) and 232 other international agreements that contain investment provisions. The total number of BITs among developing countries increased sharply from 42 in 1990 to 644 by the end of 2005, while the number of DTTs rose from 105 to 399, and other IIAs from 17 to 86 during the same period. Asian countries are particularly engaged as parties to approximately 40 per cent of all BITs, 35 per cent of DTTs and 39 per cent of other IIAs.

8.44 The East and South East Asian economies, in particular, have achieved significant integration due to liberalisation of foreign trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) regimes within the frameworks of GATT/WTO and several bilateral regional cooperation agreements. The changing production structure along with the various policy measures in the form of tariff reductions and liberalisation of investment norms have played an important role in improving the trade among the regions (Table 8.6). The resulting expansion of trade and FDI has become the engine of economic growth and development in the region. 8.45 In the sphere of finance, the traditional postulate that the capital flows from the capital surplus developed countries to the capital scarce developing countries, seems to have been disproved in recent years (Reddy, 2006b). Today, the world is confronted with the puzzle of capital flowing uphill that is, from the developing to the developed countries (Prasad et al., 2006). The world’s largest economy, the United States, currently runs a current account deficit, financed to a substantial extent by surplus savings or capital exports from the developing and emerging market economies (Table 8.7). With rising incomes and increasingly open policies, developing and emerging market economies have become a significant source of foreign direct investment, bank lending and official development assistance (ODA) to other developing countries.

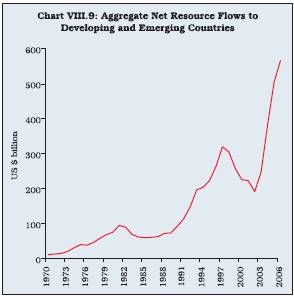

8.48 A key feature of global financial integration during the past three decades is the shift in the composition of capital flows to developing and emerging market economies. First, private sector flows have outpaced official flows due to increasing liberalisation. Second, a shift has occurred in terms of components, from the dominance of debt flows in the 1970s and the 1980s to foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio flows since the 1990s (Table 8.9). FDI flows have been determined by several push and pull factors, including strong global growth, soft interest rates in home countries, a general improvement in emerging market economies’ risks, greater business and consumer confidence, rising corporate profitability, large scale corporate restructuring, sharp recovery of asset prices and rising commodity prices. Trade and FDI openness has encouraged domestic institutional and governance reforms promoting trade and investment further. The hope of better risk sharing, more efficient allocation of capital, more productive investment and ultimately higher standards of living for all have also propelled the drive for stronger regional connections of financial systems across the world. In terms of overall financial flows, Asia has benefited from the surge in net capital flows to emerging markets in recent years.

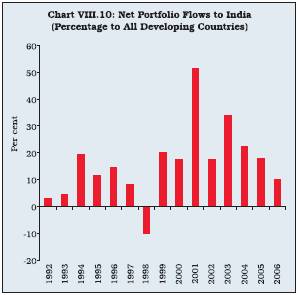

8.49 In any approach to the policies relating to the financial integration, it may be useful to consider both quantitative and qualitative factors in such flows (Reddy, 2003). An important parameter of quality of capital flows relates to volatility of such flows. In this regard, cross-country evidence on volatility of capital flows over the period 1985-2004 shows that FDI inflows to developing and emerging economies have been relatively stable as compared with other types of capital flows (Table 8.10). For instance, portfolio flows exhibited sharp variations, declining from the peak of US $ 30 billion on an average during the 1993-97 to US $ 7 billion during 1998-2002, following a series of crises in the South East Asia, the Latin America, Russia, Argentina and Turkey. 8.50 As a result of policy measures undertaken since the early 1990s, India’s trade and financial integration has grown with the global economy. This is evident from the significant increase in various indicators of openness since the onset of reforms (Table 8.11). In terms of overall trade openness during the 1990s, the Indian economy was relatively less dependent on external demand as compared with select emerging market economies. However, India’s trade openness was higher than some of the advanced economies, including the US.

characterises its expanding economic relationships with the rest of Asia. In recent years, the Asian economies are emerging as major trading partners of India. Emerging Asian economies including China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand accounted for a significant 24.1 per cent share in India’s total non-oil exports in 2005-06 (9.7 per cent in 1990-91) and 27.8 per cent of India’s non-oil imports (11.5 per cent in

1990-91). Since 2004-05, China has emerged as the third major export destination for India after the US and the UAE. China has now become the largest source of imports for India, relegating the US to the second position. India’s exports to China surged to 7.4 per cent of India’s total non-oil exports (0.3 per cent in 1991-92). Similarly, India’s imports from China accounted for 10.3 per cent of India’s total non-oil imports, a sharp increase from 0.2 per cent in 1991-92. This reflects growing trade relations between the two countries. A similar trend was noticeable vis-à-vis the ASEAN-5 (Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines). In recognition of the growing importance of Asian countries in India’s foreign trade, a series of nominal and real effective exchange rate indices released by the Reserve Bank were revised a couple of years ago to include Chinese renminbi and Hong Kong dollar in the weighting scheme. With Japan already a part of the indices, the representation of Asian economies has increased to three in the six-country real effective exchange rate index. There has been an ongoing transformation in the composition of production and trade as the comparative advantage of many Asian economies continues to change in an environment of growing regional co-operation (Box VIII.5). In particular, economies with relatively high wage costs are shifting towards higher value-added products, including services. 8.52 In tandem with trade openness, India’s capital account has witnessed a structural transformation since the early 1990s, with a shift in the composition from official flows to market-oriented private sector flows (Table 8.12). After independence, during the first three decades, trade balance was financed by capital account balance comprising mainly the official flows. During the 1980s, the dependence on official flows moderated sharply with private debt flows in the form of external commercial borrowing and non-resident Indian (NRI) deposits emerging as the key components of the capital account. 8.53 Following the shift in emphasis from debt to non-debt flows in the reform period, foreign investment comprising direct investment and portfolio flows emerged as predominant component of capital account. India’s FDI openness, as measured by FDI stock to GDP ratio, increased ten-fold from 0.5 per cent in 1990 to 5.8 per cent in 2005. However, this is still much lower than other emerging countries in Asia, including China (Table 8.13). Box VIII.5 After the South East Asian crisis of 1997, the geographic scope of cooperation initiatives is expanding across sub-regions of Asia. East Asian economies have embarked on various initiatives for regional monetary and financial cooperation. The major initiatives for regional cooperation in Asia include ASEAN+3, Chiang Mai Initiative, Executives’ Meeting of East Asia- Pacific Central Banks (EMEAP), Asian Bond Market Initiative and Asian Bond Fund. The countries of ASEAN –Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam –and India have entered into a Framework Agreement on comprehensive economic cooperation. The ASEAN has embarked on a process to expand economic cooperation with its neighbours in the north, namely China, Japan and South Korea (ASEAN+3). As far as India’s association with ASEAN community is concerned, currently India is not a full-fledged part of the ASEAN network but holds a regular summit with the ASEAN. However, in the years ahead, it is envisaged that ASEAN+3+3 network1 would help India to share and cooperate on various financial issues as the present network of ASEAN+3 has been consistently engaging in economic policy dialogue of unprecedented scope and depth. Another instance of central banking cooperation in Asia exists in the form of reciprocal currency or swap arrangements under the Chiang Mai Initiative2 . The ASEAN Swap Arrangement (ASA) was created primarily to provide liquidity support to countries experiencing balance of payments difficulties. The Finance Ministers of ASEAN+3 announced this initiative in May 2000 with the intention to cooperate in four major areas, viz., monitoring capital flows, regional surveillance, swap networks and training personnel. A more explicit central banking cooperation has been existing in the form of EMEAP since 19913. The ongoing work of EMEAP seeks to further strengthen policy analysis and advice within the region and encourage co-operation with respect to operational and institutional central banking issues. EMEAP central banks have actively coordinated on issues relating to financial markets, banking supervision and payment and settlement systems. The Asian Bond Fund (ABF) initiative of the EMEAP Group has been one of the major initiatives aimed at broadening and deepening the domestic and regional bond markets in Asia. The initiative has been in the form of ABF1 and ABF2. In the near term, the ABF2 Initiative is expected to help raise investor awareness and interest in Asian bonds by providing innovative, low-cost and efficient products in the form of passively managed bond funds. More and more similar kinds of index-driven private bond funds are rapidly emerging in Asia. At present, India does not contribute in the ABF. The informal meeting organised by Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) is, however, attended by participant central banks including India, to discuss promotion of supply of Asian Bonds. The Government of India has given a commitment on participation in the ABF2 to the tune of US$ 1 billion. SEANZA and SEACEN4 are the oldest initiatives in central bank cooperation in Asia. The SEANZA, formed in 1956, promotes cooperation among central banks by conducting intensive training courses for higher central banking executive positions with the objective to build up knowledge of central banking and foster technical cooperation among central banks in the SEANZA region. The SEACEN provides a forum for member central bank governors to be familiar with each other and to gain deeper understanding of the economic conditions of the individual SEACEN countries. It initiates and facilitates co-operation in research and training relating to the policy and operational aspects of central banking, i.e., monetary policy, banking supervision and payments and settlement systems. Asian Clearing Union (ACU), an arrangement of central banking cooperation, is successfully functioning since 1974 for multilateral settlement of payments for promoting trade and monetary cooperation among the member countries5. Since 1989, the ACU has also included a currency swap arrangement among its operational objectives. The SAARCFINANCE, established in September 1998 is a regional network of the SAARC Central Bank Governors and Finance Secretaries which aims at strengthening the SAARC with specific emphasis on international finance and monetary issues6. India has been very actively participating in SAARCFINANCE activities. The clearest evidence of Asian countries’ desire to forge closer economic relationships is the proliferation of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). By 2006, there were more than 30 FTAs under negotiation in East Asia alone. Increasingly, these agreements are also deeper, extending to areas beyond just tariff reduction. An example is the recently signed India-Singapore comprehensive economic cooperation agreement, which covers not only trade in goods, but also services, investments and cooperation in technology, education, air services and human resources. 1 India, Australia and New Zealand are included in ASEAN+3+3.

8.56 Stock markets in Emerging Asia show a high degree of correlation with several countries in the region, barring China (Table 8.14). In the region, Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore are the main drivers. The Indian stock market showed high correlation with Asian stock markets, barring China and Korea. Moreover, correlation of India’s stock market with Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore washigher than with some of the other Asian countries including, China, Korea, Malaysia and Thailand.

8.59 To sum up, past two decades have witnessed rapid increase in the pace of globalisation, led by growing participation of developing and emerging economies. Financial integration has outpaced trade integration. Cross-border flows of real and financial capital have increased sharply, reflecting the decline in the degree of home bias in capital markets. Regional integration in Asia has improved significantly due to liberalisation measures, formation of several regional cooperation agreements and stronger economic activity in the region. The sharp increase in intra-regional trade indicates that regional economies are better integrated. Regional financial integration is manifested in the price co-movements in the stock, the money and the bond markets. Stock markets in the Asian region are better correlated than the bond and the money markets. 8.60 India’s integration with the world economy has increased significantly in terms of trade openness and financial integration. Tariff liberalisation and removal of non-tariff barriers have contributed to India’s trade integration at global and regional levels. India’s capital account has witnessed a structural transformation during the reform period with cross-border non-debt creating private capital flows, emerging as a major component. India is now a major destination for global portfolio equity flows suggesting growing confidence of foreign investors in the Indian economy and financial markets. 8.61 At the regional level, India’s trade links with Asia are growing at a rapid pace, spurred by trade links with China and South-East Asian countries. Also, India’s financial integration with the Asian region has occurred through the linkage of regional stock markets and through modest correlation of bond and money markets. 8.65 The domestic credit market is also getting increasingly integrated with the international capital market as large and creditworthy borrowers have been raising large resources by way of external commercial borrowings. Such corporates are, therefore, less constrained by domestic credit conditions. Raising of resources by banks, the major players in the credit market, by way of external commercial borrowings, albeit within limits, has also integrated the domestic and international credit markets. The money market and the government securities market are also integrated as changes in money market rates are quickly transmitted to government securities yields. The linkage between the money market and the credit market also exists even as some stickiness has been observed in the lending interest rate structure. The inter-linkages between the credit market and the bond market are also growing through asset securitisation by banks. However, the inter-linkages between the equity market on the one hand, and the money, the foreign exchange and the government securities markets on the other, are still weak. The term money market and the private corporate debt market are missing links in the Indian financial markets. There is not much activity in the public issue segment of the corporate debt market, despite availability of good infrastructure, a vibrant equity market and a reasonably developed government securities market. In the corporate debt market, the issuers prefer the private placement segment, which lacks transparency and deprives the retail investor from participating in the debt market. While the need is to further deepen and widen the various segments, which would facilitate better inter-linkages among them, some specific measures that could strengthen the integration process among various market segments are detailed below. Domestic Institutional Investors 8.69 Though corporate bond yields exhibit co-movement with yields on benchmark government securities, empirical evidence supports market imperfection affecting price development in the corporate bond segment, which is the least transparent and illiquid segment of the financial market. As mentioned earlier, the corporate bond market also lacks a secondary segment. The issues relating to the development of the corporate bond market have been addressed comprehensively by the High Level Committee on Corporate Bond Market and Securitisation (Chairman: Dr. R. H. Patil). In order to develop and integrate the corporate bond market with other markets, corporate bonds have to become really tradable instruments. For this purpose, an elevated and significant level of reforms will be needed on the basis of recommendations of the High Level Committee and other measures as detailed in Chapter VII. 8.70 The government securities market holds the key to better integrated financial markets. Interest rates in government securities serve as a risk free benchmark for the purpose of asset valuation in other markets. Thus, well-functioning and deep government securities market is a necessary condition for integration of financial markets. In the government securities market, turnover in the secondary segment has declined in the recent period. While this could be termed as a cyclical development reflecting banks’ portfolio rebalancing through reduction of SLR holdings to stipulated levels in an environment of high credit demand and rising interest rates, it is critical to recognise that the persistence of such a trend could pose risks to the price discovery process and integration of financial markets. Efforts to sustain the turnover in this segment warrant the formulation of a clear strategy. Turnover in this segment is dominated by Central Government securities. Initiatives to promote trading in other securities, particularly, State Government securities, could be helpful for market development. To impart liquidity to the government securities market, the investor base also needs to be widened. There is also a need to consider various other measures as detailed in Chapter VI. Securitisation 8.71 Securitisation is gaining acceptance as one of the fastest growing and most innovative forms of asset financing in the global capital market. Asset securitisation could play an important role in promoting integration of the credit market and the debt market in India. Securitisation increases the number of debt instruments in the market. In the case of securitisation, the price of a securitised instrument would tend to converge with the price of a bond. Securitisation, by creating marketability, generates liquidity in the otherwise illiquid portfolio of loan assets of lenders. It also furthers the growth of the bond market by providing investment avenues to investors suiting their risk-return profiles. It, therefore, complements the bond market. In the Indian context, the securitisation market has witnessed a significant growth in recent years. This, therefore, should help in furthering the development of the bond market. The international experience shows that the credit appraisal and documentation process in the hands of the loan originator could be lax, which, in turn, could lead to loss of investor confidence in such instruments. Since securitisation essentially involves repackaging of a pool of a large number of relatively small-sized loan receivables, any reassessment by the market of credit risk of the pool has the potential to cause volatility in prices. Therefore, care would need to be taken to ensure that appropriate credit appraisal and documentation process is followed at the time of origination of loans. 8.72 Financial derivatives have played a major role in the development of financial markets and their integration across several economies, especially in developed countries, in the last two decades. Derivatives serve to achieve a more complete financial system because previously fixed combinations of the risk properties of loans and financial assets can be bundled and unbundled into new synthetic assets. For instance, structured products or synthetic derivatives could be created by adding elementary assets or underlying assets such as bonds, stocks (or equities) and borrowing and lending instruments with a combination of derivative products such as put and call options. Repackaging risk properties in this way can provide a more perfect match between an investor’s risk preferences and the effective risk of the portfolio or cash-flow. Derivatives allow inpidual risk elements of an asset to be priced and traded inpidually, thus, ensuring an efficient price system in the asset markets. In the Indian context, derivative instruments are available in the foreign exchange market, the money market and the equity market. In the foreign exchange market, the instruments are available in the form of currency forwards, swaps and forward rate agreements (FRAs) and rupee options. Though some of the derivative instruments have recorded growth in recent years, the derivative markets continue to face various rigidities on account of (i) lack of credible term money benchmark; (ii) lack of significant participation by large players such as public sector banks, mutual funds and insurance companies; (iii) absence of cash market for floating rate bonds; and (iv) lack of transparency in price and volume information. It would be desirable to address these issues in future for the development of the derivatives market in India. Thus, the widening of participation and enhancing the depth of the derivatives market by allowing several products could contribute to greater inter-linkages amongst the various financial market segments. 8.73 Since its emergence in the early 2000, the interest rate swap market in India has grown significantly both in terms of volumes and participants. In the absence of a term money market, choice of a transparent benchmark for the floating rate in swap deals has all along been an issue. Much like what happened under similar conditions in some other emerging countries, the market devised the so-called MIFOR swaps that use a synthetic benchmark money market rate, derived from LIBOR and the US $/Rupee forward margin. Impressive growth of the interest rate swap market notwithstanding, the risk free government securities yield curve and the swap curves are not integrated at present. The swap curves have often traded below the government securities curve. Volatility of swap rates in response to changes in short-term rates, has, at times, been higher than yields on government securities. Some policy actions that would result in integration of the government securities yield and swap rates include progressive reduction in SLR, more flexibility with regard to short sale, securities financing arrangements and more open regime in respect of arbitrage between the curves. Technology Platform 8.76 Domestic financial market integration in India has been largely facilitated by wide-ranging financial sector reforms introduced since the early 1990s. Financial markets in India have acquired greater depth and liquidity. In the process, various market segments have also become better integrated over the years. A high degree of correlation between the long-term government bond yield and the short-term Treasury Bills rate indicates the significance of the term-structure of interest rates in financial markets. Integration of the foreign exchange market with the money and the government securities markets has facilitated liquidity management by the Reserve Bank. However, the equity market has relatively low correlation with other market segments. A sharp improvement in correlation between the reverse repo rate and money market rates in recent years implies enhanced effectiveness of the monetary policy transmission mechanism. 8.77 A key feature of global financial integration during the past three decades has reflected in the shift in the composition of capital flows to developing and emerging market economies, especially from official to private flows. Regional integration has served as a major catalyst to the global integration process during the past two decades. East and South East Asian economies, in particular, have achieved substantial integration. Apart from Asia’s growing integration with the rest of the world, increasing integration within Asia also reflects the growing intra-regional trade and financial flows. Evidence from price-based measures suggests that financial market integration in Asia has been increasing. The stock markets in Asia are more integrated than the money and the bond markets. In the region, Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore serve as the nodal centres for other stock markets. 8.78 There is evidence of India’s growing international integration through trade and cross border capital flows. India’s trade and financial links with Asia are also growing amidst recent initiatives taken to promote regional cooperation. Emerging Asia has become the ‘growth centre’ of the world due to shifting of production base to the region. This is likely to stimulate greater financial integration in the region. India’s financial integration within the region and with the international financial markets is likely to increase in future in view of its robust growth prospects. However, if benefits are to be maximised from a more integrated economy, the need is to pursue efforts towards a greater sophistication of financial markets and financial market instruments that allow risks to be shared more broadly and capital to flow into the most productive sectors. There would also be a need to constantly review the risk management practices so that financial institutions and financial markets continue to remain resilient to adverse external developments. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

पेज अंतिम अपडेट तारीख: