Anil Kumar Sharma and Anujit Mitra*

This paper

explores the behaviour of the forward premia for US$ vis-à-vis

INR during the five-year period of September 2000 to September 2005. Indian forex

market experienced a peculiar phenomenon in the years 2003 and 2004 where the

forward premia on US$ spot (cash) vis-à-vis Indian rupee became

negative. This phenomenon was somewhat uncommon to Indian forex market wherein

Indian rupee was always at discount to US$ in the past. The paper tests hypothesis

of uncovered interest rate parity in the context of Indian market. The paper also

tries to find out the factors that drive the forward premia in the Indian forex

market during this period. It is observed that forex premia of US$ vis-à-vis

Indian rupee is driven to a large extent by the interest rate differential in

the inter bank market of the two economies combined with FII flows, current account

balance as well as the changes in the exchange rate of US$ vis-à-vis

Indian rupees.

JEL Classification : G13, G15.

Keywords : Forward

Premia, Uncovered Interest Rate Parity

Introduction

Indian forex market experienced a peculiar phenomenon in the

years 2003 and 2004 where the forward premia on US dollar spot (cash) vis-à-vis

Indian rupee became negative. This phenomenon was somewhat uncommon to the Indian

forex market wherein Indian rupee has always been at discount to the

US dollar in the past, in conformity with the theory.which says

that currency of the country where inflation rate/interest rate is more than that

of the other country, its currency should be at discount vis-à-vis

other country’s currency. However, years 2003 and 2004 experienced the Indian

rupee gaining strength against US dollar despite of India having higher inflation

rate / interest rate vis-à-vis US economy. This generates a question

as to what drives forward premia in Indian forex market. This also raises question

on how deep is the Indian forex market, especially the forward market.

The Indian rupee is still not fully convertible on capital

account except for certain transactions carried out by foreign institutional investors,

within certain limits, and liberalisation on Investment abroad by Indian Individuals/

companies wherein they can freely convert their foreign currency/rupee assets

into Indian/foreign currency assets by way of investment in Indian/ foreign capital

market. Recently, Indian companies have also been permitted to invest, up to 25

per cent of its net worth, in shares of foreign companies, having a minimum of

10 per cent of the share capital of a company listed in a recognized stock exchange

in India. Mutual Funds are permitted to invest in ADRs/GDRs of the Indian companies,

rated debt instruments and also invest in equity of overseas companies with an

overall cap of USD 1 billion. Furthermore, under the Liberalised Remittance Scheme

of USD 25,000, resident individuals are free to acquire and hold immovable property,

shares or any other asset outside India without prior approval of RBI, enabling

them to convert their rupee denominated assets into foreign currency denominated

assets. These are steps closer to full convertibility of rupee. As all these measures

do have an impact on exchange rate of rupee as well as forward premia of US dollar

vis-à-vis Indian rupee, developments on these fronts are worth

noticing for players active in the Indian forex market. Further, banks can hold

both rupee as well as foreign currency deposits and can transmit their influence

on interest rates as well as on forward premia.

However,

with convertibility of Indian rupee on current account, India’s increasing

share in world exports (i.e. 0.84 per cent in 2004 as against only 0.52 per cent

in 1990), liberalisation on investment abroad by Indian individuals and Indian

companies, as well as almost full convertibility of Indian rupee as regard transactions

carried out by nonresident Indians, exchange rate of Indian rupee is largely market

determined. Still the share of Indian rupee in the forex market was only 0.15

per cent of global turnover in the year 2004. This was even less in the earlier

years, as indicated by the Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and

Derivatives Market Activity by Bank for International Settlements (refer Table

1). With the US dollar still dominating the invoicing pattern of India’s

exports, this paper concentrates on forward premia on US dollar vis-à-vis

Indian rupee only. As the market decides forward premia in advance after taking

into account all the information available in the market at that time it also

raises question on whether Indian forex market satisfies the hypothesis of uncovered

interest rate parity or not.

During the last twenty-five years, the majority

of studies have rejected the hypothesis of uncovered interest rate parity, which

states that the (nominal) expected return to speculation in the forward foreign

exchange market conditioned on available information is zero. These empirical

studies have regressed ex post rates of depreciation on a constant and

the forward premium, and have rejected the null hypothesis that the slope coefficient

is one. In particular, a robust result in these studies is that this slope is

negative, and significantly different from one. This phenomenon is known as the

“forward premium puzzle” and implies that, contrary to the theory,

high domestic interest rates relative to those in the foreign country, predict

a future appreciation of the home currency. Different explanations have been given

to this issue. First, rejection of the null hypothesis can be related to the existence

of a rational risk premium in the foreign exchange market. Second, other authors

have claimed the existence of a “peso problem”, or even the existence

of irrational market participants.

To understand the

behaviour of forward premia in respect of the Indian forex market, an exploratory

analysis is carried out using data available in Database on Indian Economy

(culled out from Central Database Management System (CDBMS) of Reserve Bank

of India’s Data Warehouse) and other data series available in Telerate.

The paper tests the hypothesis of uncovered interest rate parity in the context

of Indian market in Section I. Section II discusses the various theoretical explanations

that are supposed to determine the forex premia in any market. The paper also

tries to find out the factors that drive the forward premia in the Indian forex

market in Section III. Section IV concludes the paper. Section

I

This paper has tried to test the UIP hypothesis,

in the Indian context. Empirical work on the relation between the forward premia

in the foreign exchange market to the expected change in the spot exchange rate

has been an area of active research for the last twenty years. In particular,

an important building block of this relationship has been the UIP, which states

that the (nominal) expected return to speculation in the forward foreign exchange

market conditioned on available information is zero:

Et[St+δ

- St] = ft - St | (1) |

where

is the logarithm of the spot exchange rate St, ft is the

logarithm of the forward rate Ft contracted at t and matures at

t +δt. As a consequence, the (log) forward exchange rate is an

unbiased predictor of the dt -periods ahead (log) spot exchange rate. For this

reason, UIP is also known as “Unbiasedness Hypothesis”.

Although

one main criticism made against UIP is that it pays no attention to issues of

risk aversion and inter-temporal allocation of wealth, Hansen and Hodrick (1983)

have given the following formulation, which is consistent with a model of rational

maximising behaviour. The conditions needed are that the spot and forward exchange

rates and the stochastic discount factor have a lognormal distribution with constant

conditional second moments. This proposition is known as “Modified Unbiasedness

Hypothesis” (Hodrick (1987), Engel (1996) and Wang and Jones (2002).

Assuming rational expectations (RE) in foreign exchange markets:

St+δ-

St = Et - [St+δ- St] + μt+δ,δt | (2) |

where

μt+δ,δt is a rational expectation error with zero mean

and uncorrelated with any variable in the time t.

Combining equations

(1) and (2) St+δ- St = ft -St

+μt + δ,δt which has motivated the following

OLS regression, as in Geweke and Feige (1979), as the usual starting point to

test UIP: St+δt-

St = β0 + β1 (ft - St)

+ μt+δ,δt | (3) |

as

a test of β0 = 0 and β1. However,

the RE assumption implies that errors are not autocorrelated as long as the sampling

interval is equal or larger than

δt. For this reason, different

authors, as Frenkel (1977) among others, have sampled data to produce a data set

with non-overlapping residuals with the corresponding waste of degrees of freedom.

On the other hand, Hansen and Hodrick (1980) showed how

to use overlapping data in order to increase the sample size, which will be reflected

in corresponding gains in the asymptotic power of tests. Using Hansen’s

Generalised Method of Moments, they obtain asymptotic standard errors that take

into account the serial correlation induced into the regression error when the

prediction horizon is higher than the sampling interval of the data. In the same

way, standard errors robust to conditional heteroscedasticity can also be computed.

Nonetheless, some points with respect to the single equation

approach have to be emphasised. First, the asymptotic covariance matrix is very

sensitive to the selection of the bandwidth and the kernel chosen in its estimation.

Secondly, the construction of the covariance matrix is infeasible if we want to

use high-frequency data in order to test UIP, given that the degree of overlapping

tends to infinity.

In order to test the UIP in the

case of India, this paper has used monthly interval data on forward premia and

exchange rate to avoid above- mentioned problems. Accordingly, let St+

=log (spot exchange rate of US$ vis-à-vis the Indian rupee at

time t+δ),δt= 1 month ft = log (one month forward

exchange rate of US$ vis-à-vis Indian rupee).

To test

UIP for Indian forex market:

St+δt-

St = β0 + β1 (ft - St)

+ μt+δ,δt | using

(3) |

If UIP holds good, i.e. β0 and β1

= 1, we estimate error terms and work out its variance-covariance matrix.

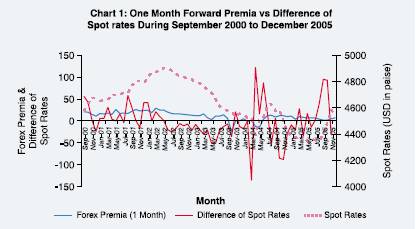

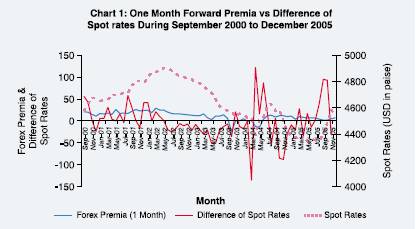

From Chart 1, it is clear that spot rate of Indian rupee vis-à-vis

US dollar started appreciating in as early as June 2002, however, one month forward

premia became negative for the first time only in October 2003. To smoothen the

volatile movements of Indian rupee, RBI absorbed almost US $ 10 billion from the

market in November, December 2003 and January 2004 (refer Table 2). While carrying

out regression as suggested in equation (3) above, it can be observed from the

results presented below that UIP hypothesis do not hold good for Indian market

as the slope coefficient is significantly different from one and is negative.

The negative slope coefficient

means market is expecting a steady appreciation of Indian rupee vis-à-vis

US dollar irrespective of the positive forward premia and in spite of higher

domestic interest rate in Indian market as compared with US market. Further, the

relationship with spot exchange rate and forward premia in Indian market is found

to be very weak. This means future spot rate of US dollar vis-à-vis

Indian rupee is driven by some other factors in addition to forward premia.

Based on equations (1), (2) and (3) above with µ=0 (i.e. assuming rational

expectation) for the period September 2000 to December 2005, the regression equation

in Indian context takes the following form | St+δt-

St = 0.00005 - 0.0583* (ft - St) | =

(0.028) (- 0.102) |

R2 = 0.0002;

t-statistic are give in parenthesis.

Question then arises is what does

forward premia in Indian forex market represent and what factors are accounted

for by the market players while determining the forward premia itself. The paper

endeavoured to analyse these factors in Section II in general and in section III

in respect of Indian forex market in particular. Section

II Forward Market for foreign exchange is extremely

important particularly for importers and exporters. This is so because international

trade results in exposure in foreign currencies. Forward Market helps the traders

in hedging the risks of this inevitable exposure in foreign currency. On the other

side there are players in foreign exchange market who offer the forward rates

for the foreign currency. A well-developed market helps in getting the better

rates for the traders promoting international trade and consequently the general

economic development.

Offering forward rates for any commodity always

involve trying to forecast the future price of the commodity keeping in view the

opportunity cost. It may require knowledge about how the price of the underlying

product is determined in the market. One also needs to be aware about the factors

influencing the price of the product. Countries are free to decide the type of

exchange rate arrangements, which could be described to vary in different degrees

from fixed to flexible exchange rate. It is practically impossible to strictly

follow either a completely fixed or flexible exchange rate. International Monetary

Fund publishes an annual report listing the different regimes followed by its

member countries. There are many countries that are following ‘pegged exchange

rate’ mechanism whereby their domestic currencies are fully pegged with

some other major foreign currency like USD. Forecasting the exchange rate and

thereby working out the forward rates for currencies following different regimes

would be different.

From the perspective of the economists there are three

classes of explanatory variables, viz., price level, interest rates and

the balance of payments to explain the behaviour of the exchange rate. The Purchasing

Price Parity or PPP hypothesis tries to explain how the price levels affect the

exchange rates. It says the relative exchange rate S = kP/P*, where P is

the price level in the domestic economy, P* is that in the other country and k

is a constant parameter. Taking differences after taking logarithms gives us Δs=

Δp - Δp* giving us the idea

how the forward rates could be influenced by the change in the level of prices

in the two economies. However, it is noted that over a short or medium term, PPP

hypothesis is conclusively rejected.

Though, it cannot

be said that the price levels have no impact on exchange rate movement or the

forward rates.

In the earlier section the paper has already talked about the

influence of interest rates on the exchange rates. Both the major Interest Rate

Parity hypotheses, i.e., Covered Interest Rate Parity (CIP) and Uncovered

Interest Rate Parity (UIP) have drawn lot of attention of the researchers, but

UIP is more interesting in the context of this paper because it involves the variable,

expected future spot rate, unlike CIP.

That the trade imbalances would

have a bearing on the behaviour of exchange rates has been recognised very early.

However, the earliest models to relate the current account to the exchange rate

followed the Marshallian tradition of treating the exchange rate as a relative

price to clear the market with the “elasticities approach”. The limitations

of this approach led to the emergence of “absorption approach” in

the 1950s. Among the series of subsequent models, the Mundell– Fleming model

is most referred. The Mundell-Fleming Model adds a balance of payments equilibrium

condition to the IS-LM Model. This extends the closed economy IS-LM framework

to examine the interplay between monetary policy and exchange rate policy. In

particular, the model emphasises the differences between fixed and floating exchange

rates. It is very apparent that the forward rate is supposed

to be arrived at from the expectations on the future exchange rates, which is

expected to get influenced by the sets of variables mentioned above as well as

all of the “news”. This news could indicate change in the economic

conditions or even political stability. The price of the crude oil in the international

market is found to impact the forex market. The forward premia is particularly

sensitive to any news having financial bearing and reacts or over-reacts instantly.

Coming back to the Indian context where the exchange rate regime currently followed

is largely market determined, the intervention by the regulator may also

play important role at least over short to medium term. Over the years, internationally,

the central banks are found to intervene through the Forward Market in Conjunction

with the spot market for making larger impact. In the next section the paper looks

at the behaviour of forward premia on US dollar vis-à-vis Indian

rupee. Section III

As

observed in Section I, UIP hypothesis does not hold good for the Indian market,

as the slope coefficient is significantly different from one. Furthermore, there

are other factors, which also influence the forward market in India. This section

has tried to identify the factors that affect forward premia in Indian forex market,

i.e., “What drives forward premia in Indian forex market?” - Is

it inflation-differential?

- Is it interest-rate differential?

- Is

it FII flows?

- Is it the current account balance in BoP?

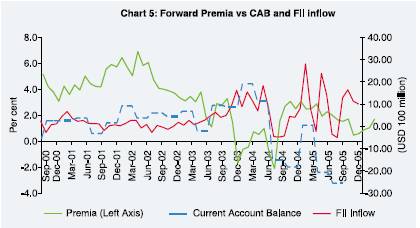

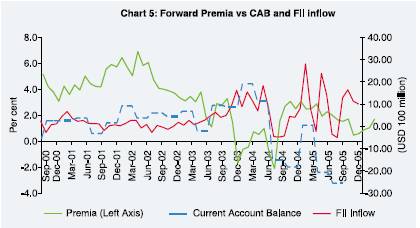

To answer this question, an attempt is made to carry -out some exploratory exercise

based on Forward Premia - annualized (INR vis-à-vis US$), Inflation

differential between Indian and US economy (i.e. WPI for India* –

CPI for US economy) (Chart 2), Interest Rate differential between 91 Day Treasury

Bills in India and US (Chart 3); Interest Rate differential between MIBOR - one

month and LIBOR-one month (Chart 4), FIIs inflows and Current Account Balance

(Chart 5). Chart 2 indicates that forward premia has a weak relationship

with Inflation-differential in US and Indian Economy.

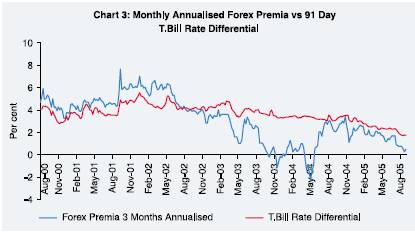

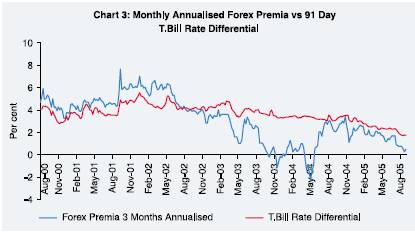

Chart 3 indicates

the relationship between 3 months forward premia (annualised) and interest rate

differential in Government of India and the US T Bills is also not strong,

though there is good co-movement some of the time. Hence the variable is considered

for further analysis.

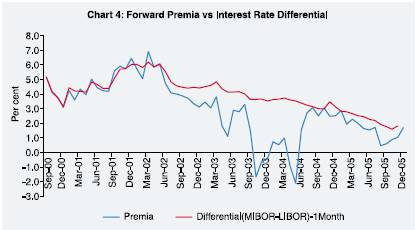

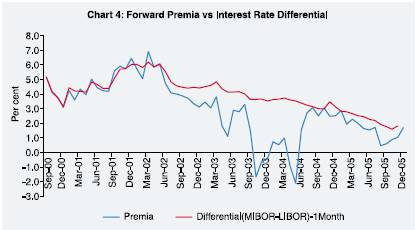

Chart

4 indicates that relationship between forward premia - 1 month (annualised) and

interest rate differential between one month MIBOR and 1 month LIBOR, is stronger

than the above two. However, there are other factors (supply

side as well as demand side), viz., fresh flows by Foreign Institutional

Investors (FIIs) and current account balances play important roles in determining

the forward premia as can be seen from the respective regression equation and

its analysis given below. In Chart 5 below the premia is shown with the

current

account balance (USD 100 million) and FII net investment (in USD 100 million).

Performing the regression of one month Forward Premia for USD vis-à-vis

INR (Annualised) vs Inflation Differential, Interest Rate Differential

(one month MIBOR – one month LIBOR), FII Portfolio Investment (net flows)

and India’s current account balance (CAB) over the entire period Septemer

2000 to September 2005, it is observed that the coefficient for Inflation differential

is not statistically significant, thereby prompting us to drop from final analysis.

Since, the information

on current account balances is available to the market with a lag, introduction

of lagged value of current account balance (1 quarter lag) showed improvement.

Furthermore, balance of payments (BoP) current account quarterly balance is distributed

equally for intervening months for regression analysis, due to non-availability

of monthly CAB data. In this connection, instead of CAB, trade balance data, which

is available on monthly frequency was also tried, but did not show good result.

Equation:

Forward Premia (Y) = f (Interest rate differential (IRD),

Current Account Balance –lagged (CAB), FIIs Net flows (FIINF))

(Period : September

2000 to September 2005) | | Coefficients | Standard

Error | t Stat | P-value |

Intercept | -2.3166 | 0.5822 | -3.9788 | 0.0002* |

IRD | 1.4393 | 0.1316 | 10.9339 | 0.0000* |

CAB | -0.1039 | 0.0145 | -7.1897 | 0.0000* |

FIINF | -0.0917 | 0.0212 | -4.3220 | 0.0001* |

* : Siginificant at 5 per cent. |

Regression

Statistics | R

Square | 0.7695 |

Adjusted R Square | 0.7574 |

Standard Error | 0.9870 |

Durbin-Watson D | 1.084 |

Furthermore to check the influence of RBI intervention

on forward premia, RBI’s Intervention (Net Purchase of USD) has also been

tried as regressor and it was found that the variable is not statistically significant

indicating that RBI intervention in forex market does not make significant impact

in determination of forward premia and it only helps in smoothing the volatility

in forex premia. Similarly

inclusion of Trade Balance as regressor in place of Current Account Balance

has not resulted in improvements. Though the regression

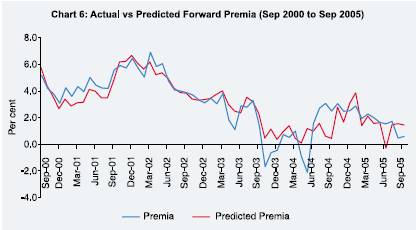

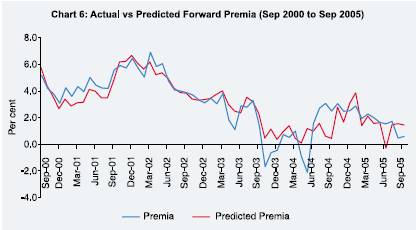

above shows a reasonable fit with expected signs, in the actual and estimated

premia plot in Chart 6 some change in pattern is observed over the period. This

motivated breaking the period of observation into two parts, i.e., September

2000 to March 2003 and April 2003 to September 2005 and explores the behaviour

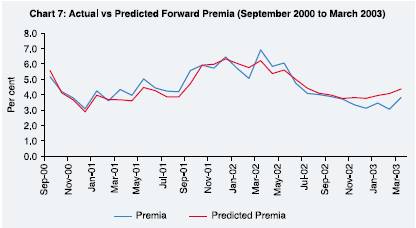

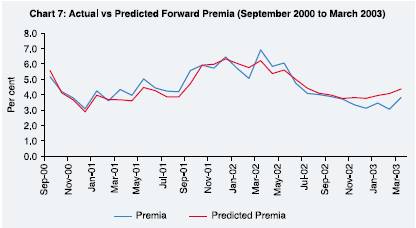

separately. For the September 2000 to March 2003 period, the regression

gives the following result:

| Coefficients | Standard

Error | t

Stat | P-value |

Intercept | -1.3441 | 0.5754 | -2.3357 | 0.0272 |

IRD | 1.2402 | 0.1164 | 10.6567 | 0.0000* |

CAB | -0.0610 | 0.0198 | -3.0746 | 0.0048* |

FIINF | -0.0076 | 0.0452 | -0.1678 | 0.8680* |

* : Siginificant

at 5 per cent |

Regression

Statistics | R

Square | 0.8135 |

Adjusted R Square | 0.7928 |

Standard Error | 0.4800 |

Durbin - Watson D | 0.980 |

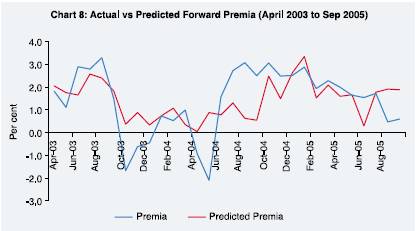

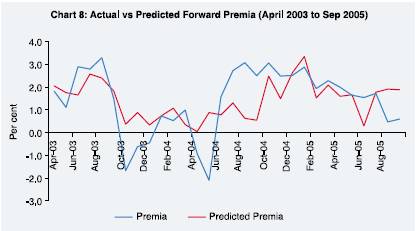

For the period April 2003 to September 2005 period, the regression gives

the following result:

| Coefficients | StandardError | t

Stat | P-value |

Intercept | -0.5304 | 1.3627 | -0.3892 | 0.7003 |

IRD | 0.7686 | 0.4251 | 1.8081 | 0.0822* |

CAB | -0.0842 | 0.0240 | -3.5074 | 0.0017* |

FIINF | -0.0682 | 0.0309 | -2.2041 | 0.0366* |

* : Siginificant at 5 per cent |

Regression

Statistics | R

Square | 0.3324 |

Adjusted R Square | 0.2554 |

Standard Error | 1.2429 |

Durbin - Watson D | 1.121 |

As observed there is a marked difference in the regression results in the two

periods. Also, the Durbin Watson D statistics, for the regression run for the

full study period, indicates the possible presence of first order autocorrelation.

One way to deal with the autocorrelation is to include the lagged value of the

dependent variable as a regressor. However, it is felt that the past forward premia

might have less influence on the current forward premia compared to the observed

change in the exchange rate in the immediately preceding period. It was indeed

found out that introducing the lagged forward premia was not improving the regression.

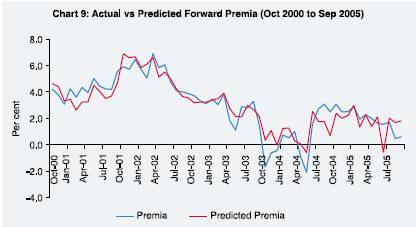

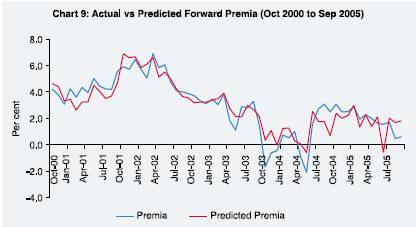

Therefore, another variable AOCER : Annualised observed change in exchange rate

of USD vis-à-vis INR was introduced. This variable captures the immediate

trend in the exchange rate. Further, this also goes well with self-fulfilling

nature as observed during the times of volatility in any financial market. The

regression results based on the four variables for the period of October 2000

to September 2005 are as follows:

| Coefficients | Standard

Error | t

Stat | P-value |

Intercept | -2.0894 | 0.5210 | -4.0107 | 0.0002* |

IRD | 1.3955 | 0.1186 | 11.7658 | 0.0000* |

CAB | -0.1109 | 0.0130 | -8.5095 | 0.0000* |

FIINF | -0.0889 | 0.0187 | -4.7451 | 0.0000* |

AOCER | 0.0477 | 0.0113 | 4.2146 | 0.0001* |

* : Siginificant at 5 per cent. |

Regression

Statistics | R

Square | 0.8236 |

Adjusted R Square | 0.8108 |

Standard Error | 0.8702 |

Durbin-Watson D | 1.144 |

It

is observed that the incorporation of the exchange rate variable, i.e, AOCER has

improved the fitness in terms of the Adjusted R Square (0.75 to 0.81) and other

parameters. More importantly, it is observed that the fit is good uniformly and

in particular much better in the second half of the study period, which experienced

volatile movements in forward premia. It is also observed that the first order

autocorrelation has come down though its presence cannot still be ruled out. This

leaves further scope for exploratory analysis in this area especially in respect

of Indian forex market, which is still emerging. Section

IV

Conclusion

In

Section I, we have seen that the UIP hypothesis does not hold good for Indian

market. It has been explored that individually no single factor is able to explain

the behaviour of the forex premia in Indian forex market. From the analysis carried

out above, we could see that in specific time window one of the factors may have

dominated in determining the movement of the forex premia. The paper has also

explored the movement of the forex premia by dividing the study period in two

parts and observed that in the first part (September 2000 to March 2003) of the

study period the coefficient of the interest rate differential was much higher

than the second part (April 2003 to September 2005). The role of foreign institutional

investment in driving the forward premia is observed to be more dominant in second

part than the first. This vindicates the perception that the premia is more and

more being influenced by demand and supply factors rather than the interest rate

differential in recent times. Though these two variables along with the interest

rate differentials were able to explain the behavior of the premia in the first

part of the study period, the relationships have weakened considerably in recent

times.

In a longer time horizon, differential between

interest rates (i.e. LIBOR-MIBOR differential) together with foreign institutional

investment in Indian market, current account balance and the change in the observed

Exchange rate are largely able to explain the behaviour of the forex premia in

Indian forex market. The findings suggest that forex premia of US$ vis-à-vis

Indian rupee is driven to a large extent by the interest rate differential in

the inter bank market of the two economies coupled with capital receipts and excess

of current accounts payments on accounts of imports in relation to exports as

well as the change in the exchange rate of USD vis-à-vis Indian

rupees.

Table

1 : Currency distribution of reported foreign exchange market turnover1 |

Percentage

shares of average daily turnover in April | Currency | 1989 | 1992 | 1995 | 1998 | 2001 | 2004 |

US dollar | 90 | 82.0 | 83.3 | 87.3 | 90.3 | 88.7 |

Euro | . | . | . | . | 37.6 | 37.2 |

Deutsche mark2 | 27 | 39.6 | 36.1 | 30.1 | . | . |

French franc | 2 | 3.8 | 7.9 | 5.1 | . | . |

ECU and other EMS currencies | 4 | 11.8 | 15.7 | 17.3 | . | . |

Japanese yen | 27 | 23.4 | 24.1 | 20.2 | 22.7 | 20.3 |

Pound sterling | 15 | 13.6 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 13.2 | 16.9 |

Swiss franc | 10 | 8.4 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

Australian dollar | 2 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 5.5 |

Canadian dollar | 1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

Swedish krona3 | … | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

Hong Kong dollar3 | … | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.9 |

Norwegian krone3 | … | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

Korean won3 | … | … | … | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

Mexican peso3 | … | … | … | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

New Zealand dollar3 | … | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

Singapore dollar3 | … | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

Danish krone3 | … | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

South African rand3 | … | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

Polish zloty3 | … | … | … | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

Taiwan dollar3 | … | … | … | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

Indian rupee3 | … | … | … | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

Brazilian real3 | … | … | … | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

Czech koruna3 | … | … | … | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Thai baht3 | … | … | … | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Hungarian forint3 | … | … | … | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

Russian rouble3 | … | … | … | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

Chilean peso3 | … | … | … | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

Malaysian ringgit3 | … | … | … | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Other currencies | 22 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 6.1 |

All currencies | 200 | 200.0 | 200.0 | 200.0 | 200.0 | 200.0 |

1 Because two currencies

are involved in each transaction, the sum of the percentage shares of individual

currencies

totals 200% instead of 100%. The figures relate to reported “net-net”

turnover, i.e., they are adjusted for both

local and cross-border

double-counting, except for 1989 data, which are available only on a “gross-gross”

basis.

2 Data for April 1989 exclude domestic trading involving the Deutsche

mark in Germany.

3 For 1992-98, the data cover local home currency trading

only.

Source : Triennial Central Bank Survey 2004,

BIS |

Table

2 : Reserve Bank’s Sale and Purchase of USD (in Million) |

Month | Sales

in US Dollar | Purchase

in US Dollar | Net

in US Dollar | 2000:09

(SEP) | 1,015.1 | 728.0 | -287.1 |

2000:10 (OCT) | 1,004.5 | 510.5 | -494.0 |

2000:11 (NOV) | 4,392.5 | 8,078.6 | 3,686.1 |

2000:12 (DEC) | 2,204.5 | 2,049.4 | -155.1 |

2001:01 (JAN) | 1,334.7 | 2,166.3 | 831.6 |

2001:02 (FEB) | 456.5 | 1,080.4 | 623.9 |

2001:03 (MAR) | 1,138.7 | 1,745.0 | 606.3 |

2001:04 (APR) | 1,626.8 | 1,608.5 | -18.3 |

2001:05 (MAY) | 613.5 | 1,082.3 | 468.8 |

2001:06 (JUN) | 1,169.2 | 1,205.5 | 36.3 |

2001:07 (JUL) | 1,130.7 | 859.0 | -271.7 |

2001:08 (AUG) | 1,052.0 | 1,733.8 | 681.8 |

2001:09 (SEP) | 2,326.1 | 1,432.0 | -894.1 |

2001:10 (OCT) | 1,043.4 | 1,280.8 | 237.3 |

2001:11 (NOV) | 1,435.0 | 2,977.1 | 1,542.1 |

2001:12 (DEC) | 1,341.2 | 2,381.6 | 1,040.4 |

2002:01 (JAN) | 1,390.5 | 2,781.7 | 1,391.2 |

2002:02 (FEB) | 1,202.5 | 1,769.3 | 566.8 |

2002:03 (MAR) | 1,428.0 | 3,710.6 | 2,282.5 |

2002:04 (APR) | 1,605.5 | 2,082.0 | 476.5 |

2002:05 (MAY) | 1,146.5 | 1,232.5 | 86.0 |

2002:06 (JUN) | 571.3 | 812.0 | 240.8 |

2002:07 (JUL) | 685.0 | 2,514.1 | 1,829.1 |

2002:08 (AUG) | 1,459.0 | 2,637.8 | 1,178.8 |

2002:09 (SEP) | 1,956.4 | 2,921.5 | 965.1 |

2002:10 (OCT) | 1,422.5 | 2,593.5 | 1,171.0 |

2002:11 (NOV) | 972.0 | 3,086.5 | 2,114.5 |

2002:12 (DEC) | 1,551.5 | 3,230.5 | 1,679.0 |

2003:01 (JAN) | 1,046.0 | 2,830.5 | 1,784.5 |

2003:02 (FEB) | 1,171.0 | 3,505.5 | 2,334.5 |

2003:03 (MAR) | 1,339.1 | 3,188.5 | 1,849.4 |

2003:04 (APR) | 1,511.0 | 2,942.5 | 1,431.5 |

2003:05 (MAY) | 1,636.0 | 3,978.0 | 2,342.0 |

2003:06 (JUN) | 982.1 | 1,878.5 | 896.4 |

2003:07 (JUL) | 2,950.0 | 6,095.5 | 3,145.5 |

2003:08 (AUG) | 1,360.0 | 3,711.5 | 2,351.5 |

2003:09 (SEP) | 4,229.4 | 6,574.0 | 2,344.6 |

2003:10 (OCT) | 5,227.7 | 6,821.0 | 1,593.3 |

2003:11 (NOV) | 580.0 | 4,029.0 | 3,449.0 |

2003:12 (DEC) | 484.4 | 3,372.5 | 2,888.1 |

2004:01 (JAN) | 1,028.0 | 4,321.5 | 3,293.5 |

2004:02 (FEB) | 2,163.0 | 5,519.5 | 3,356.5 |

2004:03 (MAR) | 2,789.0 | 6,170.5 | 3,381.5 |

2004:04 (APR) | 3,332.9 | 10,758.5 | 7,426.5 |

2004:05 (MAY) | 3,439.5 | 3,219.5 | -220.0 |

2004:06 (JUN) | 1,383.0 | 969.5 | -413.5 |

2004:07 (JUL) | 1,179.5 | | -1,179.5 |

2004:08 (AUG) | 880.5 | 5.0 | -875.5 |

2004:09 (SEP) | 124.0 | 143.0 | 19.0 |

2004:10 (OCT) | 104.0 | 5.0 | -99.0 |

2004:11 (NOV) | | 3,791.5 | 3,791.5 |

2004:12 (DEC) | 108.2 | 1,501.5 | 1,393.3 |

2005:01 (JAN) | | | 0 |

2005:02 (FEB) | | 4,974.0 | 4,974.0 |

2005:03 (MAR) | | 6,030.0 | 6,030.0 |

2005:04 (APR) | | | 0 |

2005:05 (MAY) | | | 0 |

2005:06 (JUN) | 103.6 | | -103.6 |

2005:07 (JUL) | | 2,473.0 | 2,473.0 |

2005:08 (AUG) | 451.0 | 2,003.0 | 1,552.0 |

2005:09 (SEP) | | | 0 |

2005:10 (OCT) | | | 0 |

Source

: Reserve Bank of India Bulletin. | References

Baillie, R.T., R. E. Lippens, and P. C. McMahon (1983): “Testing Rational

Expectations and Efficiency in the Foreign Exchange Market”,

Econometrica,

51, 553-564

Bekaert, G. and R. Hodrick (2001): “Expectations Hypotheses

Tests”, Journal of Finance, 56, 4, 1357-1393.

Cochrane, J.

(2001): Asset Pricing, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

Database on Indian Economy (https://cdbmsi.reservebank.org.in/)

Fama E. (1984):

“Forward and Spot Exchange Rates”, Journal of Monetary Economics,

14, 319-338.

Flood, R.P and A. K. Rose (2002): “Uncovered Interest Parity

in Crisis”, IMF Staff Papers, 49, 2, 252-266.

Frenkel, J. A.

(1977): “The Forward Exchange Rate, Expectations, and the Demand for Money:

The German Hyperinflation”, American Economic Review, 67, 653-670.

Geweke, J. and E. Feige (1979): “Some Joint Tests of the Efficiency of Markets

for Forward Foreign Exchange”, Review of Economic Statistics, 61,

334-341.

Hakkio, C. S. (1981): “Expectations and the Forward Exchange

Rate”,

International Economic Review, 22, 663-678.

Hansen

L.P. and R. Hodrick (1980): “Forward Exchange Rates as Optimal Predictors

of Future Spot “Rates: An Econometric Analysis”, Journal of Political

Economy, 88, 5, 829-853.

Hansen L.P. and R. Hodrick (1983): “Risk

Averse Speculation in the Forward Foreign Exchange Market: An Econometric Analysis

of Linear Models” in Exchange Rates and International Macroeconomics,

ed. by J.A. Frenkel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press for National Bureau

of Economic Research, 1983.

Hodrick, R. (1987): The empirical evidence on

the efficiency of forward and futures foreign exchange markets, Harwood Academic

Publishers, Chur, Switzerland Horvath M.T.K and M. W. Watson (1995): “Testing

for Cointegration When Some of the Cointegrating Vectors are Prespecified”,

Econometric Theory, 11, 5, pp. 952-984.

Lewis K. (1989): “Changing

Beliefs and Systematic Rational Forecast Errors with Evidence from Foreign Exchange”,

American Economic Review, 79, 621-36.

Mark N.C. and Y. Wu (1998):

“Rethinking Deviations from Uncovered Interest Rate Parity: The Role of

Covariance Risk and Noise”, Economic Journal, 108, 1686-706.

Phillips P.C. B. (1991): “Error Correction and Long Run Equilibrium in Continuous

Time”, Econometrica, 59, 967-980.

RBI (2005): Annual Report,

2004-05.

Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives

Market Activity by Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2004.

Wang P.

and T. Jones (2002): “Testing for Efficiency and Rationality in Foreign

Exchange Markets - A Review of the Literature and Research on Foreign Exchange

Market Efficiency and Rationality with Comments”,

Journal of International

Money and Finance, 21, 223-239.

* Shri Anil Kumar Sharma

is Director and Shri Anujit Mitra is Assistant Adviser in Operational Analysis

Division of Department of Statistical Analysis & Computer Services (DESACS). The

authors wish to thank Dr. Balwant Singh, Adviser, DESACS for his comments on the

earlier version of the paper. An earlier version of the paper was also presented

at the Eighth Money and Finance Conference at Indira Gandhi Development Research

Institute (IGIDR) in March 2006. The views expressed in the paper are of the authors

own and do not reflect the views of the organization to which they belong. *In

the case of India, a representative CPI is not available at present. |

IST,

IST,