IST,

IST,

SME Financing through IPOs – An Overview

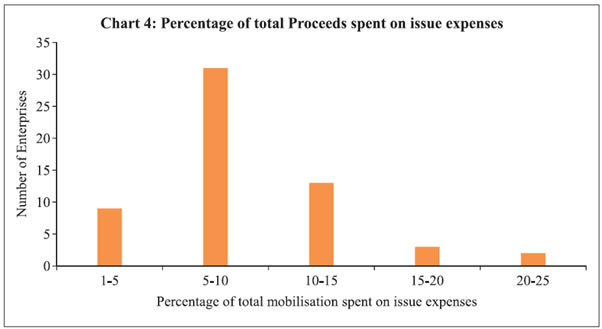

R. K. Jain, Avdhesh Kumar Shukla and Kaushiki Singh* The new initiative of capital financing of SMEs through IPOs has been quite encouraging and the secondary market performance of SME IPOs has also been very good. However, it seems that this is risky for investors, as there is not enough liquidity and the turnover is also low. Considering these problems, market regulator SEBI has issued guidelines to keep away small investors from investing in SME IPOs. In order to make the market liquid, SEBI guidelines stipulate that merchant bankers should act as market makers in such stocks for three years. However, after the stipulated period of three years, the stocks may face the problem of liquidity again. In order to avoid such a scenario, the present paper suggests the need for more transparency and increased institutional participation in companies listed on SME platforms. Also, stock exchanges where these companies are listed should provide sustained handholding to the managements of these companies. JEL Classification : G1, G18, Y10 Introduction Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play an important role in the socio-economic development of India due to their vital contribution to GDP, industrial growth, employment and exports. However, this sector is beset with challenges including lack of availability of adequate and timely credit and limited access to equity capital (SIDBI 2013). SMEs have primarily relied on bank finance to meet their working capital requirements, but equity capital has to be brought in by the promoters of the enterprises. Till recently, institutional arrangements for equity and risk capital were provided only by the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) under the Growth Capital and Equity Assistance Scheme for MSMEs (GEMS) (SIDBI 2013). In order to provide a market based solution for equity resource mobilization by SMEs, the need for having a separate exchange/platform for SMEs has been felt for a long time (RBI 2008). Though efforts were made in the past to cater to the needs of small companies through initiatives such as OTC Exchange of India (OTCEI) set up in 1990 and the INDO NEXT Platform of the BSE launched in 2005, these experiments could not achieve desired results (SEBI 2008). Finally, efforts to provide an alternative source of equity funding to SMEs fructified with the launch of the BSE SME platform by BSE on March 12, 2012 and the SME platform ‘Emerge’ by NSE in September 2012. This paper makes an attempt to review the performance of SME platforms in India. In addition to the introduction, the rest of the paper is divided in six sections. Section II highlights the international experience of SME exchanges. Section III covers the policy framework related to equity resource mobilization by SMEs through IPOs. Section IV throws light on the performance of primary market in terms of resource mobilization by SMEs on recently launched SME platforms. Secondary market performance of companies listed on the SME platforms is outlined in Section V, while Section VI provides financial and non-financial information related to these companies. Section VII sums up the paper. International Scenario Globally, adequate flow of equity finance to SMEs has been recognized as policy priority. In order to achieve this, both developed and developing countries have set up alternative stock exchanges for SMEs. In fact, the need for an alternative stock exchange for SMEs has been so acutely felt in the countries that the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) has identified promotion of such exchanges as one of the areas for mutual cooperation (IOSCO 2012). Presently, separate exchanges/platforms dedicated to equity financing of SMEs are functioning in more than 24 countries (Yoo 2007). Their main features, listing norms and performances, are now briefly discussed. The London Stock Exchange’s Alternative Investment Market (AIM), which was set up in 1995, has succeeded in attracting a large number of small-sized companies globally, including a few Indian ones. AIM facilitates easy entry and less onerous disclosure requirements, but it has in place an appropriate level of regulation for smaller companies. It also provides a faster admission process and no pre-vetting by the regulator (SEBI 2008). So far, firms have raised almost 30 billion pounds via IPOs on AIM with companies coming from 37 sectors, 90 sub-sectors and 26 countries (AIM 2014). The National Stock Exchange (NSX) in Australia, a fully operational and regulated main board stock exchange, is focused on listing SMEs. NSX operates Australia’s two premier alternative stock exchanges. The NSX Corporate Exchange specializes in the listing of SMEs and the NSX Alternative Exchange has attracted the listing of community based organizations such as community banks. Both of these exchanges are able to support the listing of regional enterprises (Symon 2007). An alternative exchange for SMEs in South Africa (Altx) was set up in October 2003. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange in South China’s Guandong Province officially inaugurated a board for SMEs in May 2004. Similarly, Egypt launched its SME Exchange (NILEX) in October 2007 where companies with capital ranging from EGP 500,000 to EGP 25 million could be listed (Ministry of Finance, Egypt 2008). Other SME exchanges are GEM (Growth Enterprise Market) in Hong Kong and the Market of the High-Growth and Emerging Stocks (MOTHERS) in Japan (both started in 1999). Unlike AIM and MOTHERS, which are trading platforms of their respective main stock exchanges, GEM is a separate dedicated stock exchange. GEM functions on the philosophy of ‘buyers beware’ and ‘let the market decide’ based on a strong disclosure regime. The rules and requirements are designed to foster a culture of self compliance by the listed issuers in the discharge of their responsibilities (Stock Exchange of Hong Kong 2014). In the case of MOTHERS, the emerging companies applying there must have the potential for high growth though there are no specific numerical criteria for determining the growth potential. Further, the applicant company is mandated to make a public offering of at least 500 trading units. At the time of listing, it should have at least 2,000 trading units and the market capitalization of its listed shares should be more than 1 billion yen. The applicant must also have a continuous business record of not less than one year dating back from the day on which it made the listing application (SEBI 2008, TSE 2014). Other initiatives include TSX Ventures Exchange (TSX-V) in Canada, Catalist in Singapore, KOSDAQ in the Republic of Korea and MESDAQ in Malaysia. As a matter of fact, NASDAQ also started as an SME Exchange and provides special facilities for listing of small and medium enterprises. In 2013, the Nigerian Stock Exchange inaugurated the Alternative Securities Market (ASEM), which is a platform for small businesses and SMEs in Nigeria to trade their equities on the Nigerian Stock Exchange. Similarly, the Rwanda Stock Exchange (RSE) has also started an initiative for small and medium enterprises’ (SMEs) listing on the alternative market segment of the bourse. The Istanbul Stock Exchange (ISE) in Turkey has a particular segment catering to the funding requirements of SMEs. An analysis of listing norms of SME exchanges indicates that nearly all new markets adopt looser listing and maintenance requirements than the main market, typically allowing more relaxed criteria on operating history, minimum number of shareholders, past financial performance and the number of free-float shares. However, Brazil’s Novo Mercado is an exception: it sets higher standards for listed firms than the main market, emphasizing gaining investor trust over relaxing constraints (Yoo 2007). In terms of secondary market liquidity, globally SME exchanges have varied experiences. In order to ensure sufficient liquidity, most of the exchanges have put in place alternative arrangements such as market makers for liquidity. In India, while framing policies related to the SME Exchange, some of the global practices have been followed. Policy Framework on Listing of SMEs in India In India, policies relating to SME platforms were formulated after taking into account learnings from the global experience, domestic capital market realties, difficulties faced by SMEs and OTCEI’s experience1 (BSE 2011). As per SEBI guidelines, SME exchanges should be set up as corporatized entities (bodies with a structure found in publicly traded firms) with minimum net worth of ₹1,000 million. These guidelines stipulate that an issuer with post issue face value of up to ₹100 million will be invariably covered under the SME exchange whereas issuers with post issue face value capital between ₹100 million and ₹250 million may get listed either on the SME exchange or on the main board (Table 1). SEBI has relaxed norms for listing on the SME Exchange as issuers do not need to have a track record of distributable profits for three years as in the case of listing on the main board. The present guidelines have a three-pronged approach: a) to safeguard the interest of investors by keeping larger lot sizes, so that only informed investors are able to participate, b) maintaining sufficient liquidity by provision of market making and c) reducing the time involved in the processing of the issue by allowing a merchant banker to file RHP with due diligence certificate with the exchange and treating approval of the exchange sufficient (BSE 2011). Performance of SME Platforms in terms of Since the launch of SME platforms (from April 2012 to May 2014), 64 companies have got listed on SME platforms. Of these 64 companies, 61 are listed on the BSE SME platform and three on the NSE Emerge. These companies have mobilized total resources of ₹5.9 billion from the capital market, which is around two per cent of ₹281.0 billion overall equity mobilization by stock exchanges during the same period (from April 2012 to May 2014) (Table 2). When compared with bank credit to the small scale sector, the funds mobilized through SME platforms appear even more insignificant. During 2012-13, bank credit deployed to small scale industries was ₹480 billion as compared to ₹2.4 billion mobilized through SME platforms. In percentage terms, equity resources mobilized through SME platforms was only 0.5 per cent of the bank credit to this sector during 2012-13. However, it is still encouraging, as the amount of ₹2.4 billion mobilized during financial year 2012-13 through equity issues is higher than equity related assistance aggregating ₹1.5 billion extended by SIDBI during the financial year 2012-132. Therefore, though this route is still in a nascent stage, it is an encouraging initiative and the initial responses may be termed as satisfactory. Sectoral distribution of the 64 companies which mobilized resources from the market (up to end May 2014) indicates that 14 of these companies were engaged in the financial services sector (including NBFCs and securities firms), seven in ‘Textile and Apparel’ and six each in ‘construction and real estate’ and ‘agro and food processing’ sectors (Chart 1). Further, a majority of the companies were from the services sector, mostly from the financial services sector. Nevertheless, they were significantly diversified. Sectoral diversification of listed firms is crucial from the risk management perspective of SME platforms as well as for investors. Performance of SME IPOs in the Secondary Market Besides the SME platform, BSE has also launched a Barometer Index -- the BSE SME IPO to track the performance of SME IPOs in the secondary market. The BSE SME IPO Index is calculated with free float methodology in line with other BSE indices. The number of scrips included in the index are variable. However, at any point of time a minimum of 10 companies should be maintained in the index. All new listed companies are compulsorily included in the index and a company which has completed three years after listing is automatically excluded from it. However, if there are less than 10 companies on account of possible exclusion after three years, the exclusion of such companies should be delayed till such time new inclusion is made in the index.3 Since its launch on December 14, 2012, the index up to June 24, 2014 witnessed a huge rally of about 601.3 per cent which is significantly higher than gains in other stock indices in India (Chart 2). A scrip-wise analysis of the movement of share prices (as on June 24, 2014) of companies listed on the BSE SME platform indicates that sixteen companies recorded more than 100 per cent increase over the offer price and seven companies between 50 to 100 per cent increase, while seventeen companies recorded negative returns over the offer price (Chart 3). Though a majority of the companies listed on the SME platform recorded positive returns, most of these scrips had very low liquidity. However, SEBI guidelines stipulate that merchant bankers should act as market makers in the stock for three years. This means that the appointed market makers will provide two-way quotes for the stock for 75 per cent time of the day. They will hold a certain number of shares of the company and facilitate trading in that security by becoming the counter party to a buyer or a seller in the stock. It is expected that in due course liquidity will increase in this segment. Some Financial Attributes of the Companies The major financial attributes of companies listed on SME platforms have been analysed as: a) Profitability: Profit and loss data of 56 out of the 64 companies are available for the three-year period preceding the issue. Out of these 56 companies, 40 companies recorded profits in all the three years of their operations prior to the issue. Out of these 40 companies, 24 witnessed a sustained rise in their profits. Six companies recorded losses in the year preceding the issue and one company did not earn any profit during the three-year period prior to issue. Hence, as far as profitability is concerned, these companies had a mixed track record. b) Price-earnings ratio: A comparison of the price-earnings (P-E) ratio of SME companies at the time of listing in the exchange with their peer group companies indicates that out of 39 companies for which comparable data are readily available, 19 had P/E ratios higher than the industry average, whereas 20 companies had P-E ratios lower than industry peer group average. On the basis of P-E ratios, it can be inferred that these stocks are not cheaply priced. c) Institutional Holdings: Institutional holdings of the enterprises show that in most of these companies, the promoters held on an average 52 per cent of the stakes. Institutional holdings were very small in some and absent in most companies. A higher holding by financial institutions ensures better governance and higher accountability, which seems to be absent in most of the enterprises. Participation by institutional investors who take investment decisions after a critical analysis of the business prospects of the issuers will encourage a larger number of individual investors to gain confidence about investing in SME issues (NSE 2013). d) Utilization of Resources Raised by Firms: Most of the companies that had mobilized resources through equity issues aimed to deploy them for meeting working capital requirements, augmenting capital base, general corporate purposes, enhancement of margin requirements and expansion of businesses. Five enterprises raised capital in order to repay their debts. e) Expenses on Public Issues: An analysis of expenses on public issue floatations as percentage of issue proceeds indicates that the cost of floatation by the SME companies was significantly higher than those companies which were listing on the main exchanges. Chart 4 shows that out of 58 enterprises, 31 spent 5-10 per cent, 13 spent 10-15 per cent, three spent 15-20 per cent and two spent 20-25 per cent of the total gross mobilization on issue expenses. Issue related expenses for the companies on main exchanges were on an average about 5 per cent during 2012-13 and 2013-14. A higher share of issue floatation expenses was on account of high underwriting fees charged by the underwriters. High underwriting fees was mainly on account of the expanded role that merchant bankers played in case of SME IPOs vis-à-vis main exchange IPOs. In the case of SME IPOs, merchant bankers are also entrusted with the responsibility of market making of the security for three years in addition to underwriting the issue 100 per cent. While in a normal IPO, the role of a merchant banker ends once the issue process is over in the case of a SME IPO because of his market making responsibilities a merchant banker has to stay involved with the company for three years after completion of the issue process. In order to discharge the function of market making, a merchant banker has to keep some securities with him, which raises his capital requirement. As a result, the fee charged by a merchant banker increases and thereby the cost of equity resource raising by the SME companies from the SME Exchange goes up. On the basis of this analysis of the publicly available financial attributes, it is difficult to conclude that the financial attributes of companies listed on SME platforms are the major drivers of the strong increase in the stock prices of these companies in the secondary market. One possible explanation for the strong rise in stock prices of SME companies in the secondary market could be the high weightage attached to the management of these companies by investors. However, in such a scenario, companies’ managements should be encouraged to increase transparency and provide more accurate information about their functioning for informed price discovery. Exchanges may also provide handholding to the companies listed with them. They may also provide research updates on the financial performance of these companies on a regular basis which will reduce information asymmetry about them.4 Summing up Given the importance of SMEs in the Indian economy, an adequate flow of financial resources is a priority for the government and regulatory authorities. The stock exchanges have launched a new platform for meeting the equity funding requirements of SMEs. An analysis of SME issues listed on SME platforms indicates that in terms of amount of equity resource mobilization, their initial performance is encouraging. However, issue floatation costs of these companies are significantly higher. A sharp rally in the BSE SME IPO Index, despite a not so encouraging scenario in the overall secondary market, low liquidity and low volume of trading add to the caution list about the performance of these issues. Though at present only informed investors who have risk taking appetites are expected to participate in SME platforms, managements of the listed companies should be encouraged to increase financial transparency for fair pricing. In order to tackle problem of illiquidity, SEBI has made it compulsory for the underwriter to act as the market maker for a period of three years in order to facilitate trading. However, after the completion of the stipulated three years, given the illiquidity in these scrips, the performance of the index might pose a problem. Over reliance on underwriters for market making puts a huge responsibility on merchant bankers. It increases their capital commitments. A high capital commitment discourages reputed merchant bankers to participate in the market which in turn raises the cost for the issuer. Low participation of institutional investors in SME platforms is another weak link of this segment. In order to make SME platforms sustainable exchanges and regulators should look into these weaknesses and try to remove these weak links by enhancing financial transparency and handholding. References: Arthapedia (2013), ‘SME Exchange / Platform’, available at: http://www.arthapedia.in/index.php?title=SME_Exchange_/_Platform. AIM. (2014), Available at: http://www.aimlisting.co.uk/index.php/page/The-Aim-Market. Bombay Stock Exchange (2011), available at: http://www.bsesme.com/downloads/BSE_SME_EBOOK.pdf. International Council of Securities Association (2013), Financing of SMEs through Capital Markets in Emerging Market Countries’, ICSA Emerging Markets Committee, February 2013. International Organization of Securities Commissions (2012), Media Release, November 20, 2012, available at: https://www.iosco.org/media_room/?subsection=media_releases. Ministry of Finance (Egypt) (2008), ‘Past, Present and Future: SME Policy in Egypt’, Conference Report, Ministry of Finance, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and International Development Research Centre (IDRC), January 15-16, 2008. Modak, Samie (2012), ‘IPOs a costly affair for small companies’, Business Standard. Mumbai, September27, 2012, available at: http://www.business-standard.com/article/markets/ipos-a-costly-affair-for-small-companies-112092700074_1.html. Nandi, Suresh (2012), ‘SME exchanges: New opp for small cos’, Deccan Herald, April 1, 2012. National Stock Exchange (2013), ‘Emerge: NSE’s Platform for SME Listing, Indian Securities Market, A review (ISMR)’, National Stock Exchange, India, available at: http://www.nseindia.com/emerge/sme_brochure.pdf. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2009), ‘The Impact of the Global Crisis on SME and Entrepreneurship Financing and Policy Responses’, Contribution to the OECD Strategic Response to the Financial and Economic Crisis, Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development, OECD. Reserve Bank of India (2008), ‘Report on Currency and Finance 2006-08’ Vol. II, September. Respective Prospectus of all the listed SMEs downloaded from SEBI website at: www.sebi.gov.in. Securities and Exchange Board of India (2008), ‘Discussion paper on developing a market for Small and Medium Enterprises in India, India’, available at: http://www.sebi.gov.in/commreport/sme.pdf. Small Industries Development Bank of India (2013), Annual Report, Small Industries Development Bank of India, India. SME World (2014), Available at: http://smeworld.org/story/sme-exchange/sme-exchange-launched.php. Stock Exchange of Hong Kong (2014), Available at: http://www.hkgem.com/aboutgem/e_default.htm?ref=7%3A. Symon, Richard (2007), ‘Developing Regional Stock Exchanges’, EDA Paper No. 07, Summer, Economic Development Australia. Tokyo Stock Exchange (2014), Available at: http://www.tse.or.jp/english/rules/mothers/. Yoo, JaeHoon (2007), ‘Financing Innovation: How To Build an Efficient Exchange for Small Firms’, The World Bank Group, Note Number 315, March. * R.K. Jain, Avdhesh Kumar Shukla and Kaushiki Singh are Director, Assistant Adviser and Research Officer, respectively in the Department of Economic and Policy Research. The views expressed in the paper are personal and not of the institution that they are working with. Usual disclaimers apply. 1 There are two important distinguishing attributes between OTCEI and present SME exchanges: 1) Unlike OTCEI, which was standalone, present day SME exchanges are completely integrated with the respective main exchange and there is a provision for migration from the SME platform to the main exchange and vice versa. 2) There is a provision of 100 per cent underwriting of the issue and market maker for three years after the listing to provide liquidity (SME World 2014). 2 Corresponding data for 2013-14 from SIDBI are not available for comparison. 3 http://www.bseindia.com/indices/sme_ipo.aspx?page=531BB8D5-6CB9-4ABC-8791-378F12A70B60. 4 Though BSE provides research notes on the financial performance of the companies listed on its platform, at present it is not provided on a regular basis. |

पेज अंतिम अपडेट तारीख: