IST,

IST,

Minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting, September 28-30, 2022

[Under Section 45ZL of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934] The thirty eighth meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), constituted under section 45ZB of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, was held during September 28-30, 2022. 2. The meeting was attended by all the members – Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Honorary Senior Advisor, National Council of Applied Economic Research, Delhi; Dr. Ashima Goyal, Emeritus Professor, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai; Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad; Dr. Rajiv Ranjan, Executive Director (the officer of the Reserve Bank nominated by the Central Board under Section 45ZB(2)(c) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934); Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra, Deputy Governor in charge of monetary policy – and was chaired by Shri Shaktikanta Das, Governor. 3. According to Section 45ZL of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, the Reserve Bank shall publish, on the fourteenth day after every meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee, the minutes of the proceedings of the meeting which shall include the following, namely:

4. The MPC reviewed the surveys conducted by the Reserve Bank to gauge consumer confidence, households’ inflation expectations, corporate sector performance, credit conditions, the outlook for the industrial, services and infrastructure sectors, and the projections of professional forecasters. The MPC also reviewed in detail the staff’s macroeconomic projections, and alternative scenarios around various risks to the outlook. Drawing on the above and after extensive discussions on the stance of monetary policy, the MPC adopted the resolution that is set out below. Resolution 5. On the basis of an assessment of the current and evolving macroeconomic situation, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at its meeting today (September 30, 2022) decided to:

Consequently, the standing deposit facility (SDF) rate stands adjusted to 5.65 per cent and the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate and the Bank Rate to 6.15 per cent.

These decisions are in consonance with the objective of achieving the medium-term target for consumer price index (CPI) inflation of 4 per cent within a band of +/- 2 per cent, while supporting growth. The main considerations underlying the decision are set out in the statement below. Assessment Global Economy 6. Global economic activity is weakening under the impact of the protracted conflict in Ukraine and aggressive monetary policy actions and stances across the world. As financial conditions tighten, global financial markets are experiencing surges of volatility, with sporadic sell-offs in equity and bond markets, and the US dollar strengthening to a 20-year high. Emerging market economies (EMEs) are facing intensified pressures from retrenchment of portfolio flows, currency depreciations, reserve losses and financial stability risks, besides the global inflation shock. As external demand deteriorates, their macroeconomic outlook is becoming increasingly adverse. Domestic Economy 7. Real gross domestic product (GDP) grew year-on-year (y-o-y) by 13.5 per cent in Q1:2022-23. While all constituents of domestic aggregate demand expanded y-o-y and exceeded their pre-pandemic levels, the drag from net exports provided an offset. On the supply side, gross value added (GVA) rose by 12.7 per cent in Q1:2022-23, with all constituents recording y-o-y growth and most notably, services. 8. Aggregate supply conditions are improving. With the south-west monsoon rainfall 7 per cent above the long period average (LPA) as on September 29 and its spatial distribution spreading to some deficit areas, kharif sowing has been catching up. Acreage was 1.7 per cent above the normal sown area as on September 23 and only 1.2 per cent below last year’s coverage. The production of kharif foodgrains as per first advance estimates (FAE) was 3.9 per cent below last year’s fourth advance estimates (only 0.4 per cent below last year’s FAE). Activity in industry and services sectors remains in expansion, especially the latter, as reflected in purchasing managers indices (PMIs) and other high frequency indicators. The index of industrial production growth, however, slowed to 2.4 per cent (y-o-y) in July. 9. On the demand side, urban consumption is being lifted by discretionary spending ahead of the festival season and rural demand is gradually improving. Investment demand is also gaining traction, as reflected in rising imports and domestic production of capital goods, steel consumption and cement production. Merchandise exports posted a modest expansion in August. Non-oil non-gold imports remained buoyant. 10. CPI inflation rose to 7.0 per cent (y-o-y) in August 2022 from 6.7 per cent in July as food inflation moved higher, driven by prices of cereals, vegetables, pulses, spices and milk. Fuel inflation moderated with reduction in kerosene (PDS) prices, though it remained in double digits. Core CPI (i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel) inflation remained sticky at heightened levels, with upside pressures across various constituent goods and services. 11. Overall system liquidity remained in surplus, with the average daily absorption under the liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) easing to ₹2.3 lakh crore during August-September (up to September 28, 2022) from ₹3.8 lakh crore in June-July. Money supply (M3) expanded y-o-y by 8.9 per cent, with aggregate deposits of commercial banks growing by 9.5 per cent and bank credit by 16.2 per cent as on September 9, 2022. India’s foreign exchange reserves were placed at US$ 537.5 billion as on September 23, 2022. Outlook 12. High and protracted uncertainty surrounding the course of geopolitical conditions weighs heavily on the inflation outlook. Commodity prices, however, have softened and recession risks in advanced economies (AEs) are rising. On the domestic front, the late recovery in sowing augurs well for kharif output. The prospects for the rabi crop are buffered by comfortable reservoir levels. The risk of crop damage from excessive/unseasonal rains, however, remains. These factors have implications for the food price outlook. Elevated imported inflation pressures remain an upside risk for the future trajectory of inflation, amplified by the continuing appreciation of the US dollar. The outlook for crude oil prices is highly uncertain and tethered to geopolitical developments, with attendant concerns relating to both supply and demand. The Reserve Bank’s enterprise surveys point to some easing of input cost and output price pressures across manufacturing, services and infrastructure firms; however, the pass-through of input costs to prices remains incomplete. Taking into account these factors and an average crude oil price (Indian basket) of US$ 100 per barrel, inflation is projected at 6.7 per cent in 2022-23, with Q2 at 7.1 per cent; Q3 at 6.5 per cent; and Q4 at 5.8 per cent, and risks are evenly balanced. CPI inflation for Q1:2023-24 is projected at 5.0 per cent (Chart 1). 13. On growth, the improving outlook for agriculture and allied activities and rebound in services are boosting the prospects for aggregate supply. The Government’s continued thrust on capex, improvement in capacity utilisation in manufacturing and pick-up in non-food credit should sustain the expansion in industrial activity that stalled in July. The outlook for aggregate demand is positive, with rural demand catching up and urban demand expected to strengthen further with the typical upturn in the second half of the year. According to the RBI’s surveys, consumer outlook remains stable and firms in manufacturing, services and infrastructure sectors are optimistic about demand conditions and sales prospects. On the other hand, headwinds from geopolitical tensions, tightening global financial conditions and the slowing external demand pose downside risks to net exports and hence to India’s GDP outlook. Taking all these factors into consideration, real GDP growth for 2022-23 is projected at 7.0 per cent with Q2 at 6.3 per cent; Q3 at 4.6 per cent; and Q4 at 4.6 per cent, and risks broadly balanced. For Q1:2023-24, it is projected at 7.2 per cent (Chart 2).  14. In the MPC’s view, inflation is likely to be above the upper tolerance level of 6 per cent through the first three quarters of 2022-23, with core inflation remaining high. The outlook is fraught with considerable uncertainty, given the volatile geopolitical situation, global financial market volatility and supply disruptions. Meanwhile, domestic economic activity is holding up well and is expected to be buoyant in H2:2022-23, supported by festive season demand amidst consumer and business optimism. The MPC is of the view that further calibrated monetary policy action is warranted to keep inflation expectations anchored, restrain the broadening of price pressures and pre-empt second round effects. The MPC feels that this action will support medium-term growth prospects. Accordingly, the MPC decided to increase the policy repo rate by 50 basis points to 5.90 per cent. The MPC also decided to remain focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. 15. Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, Dr. Rajiv Ranjan, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Shri Shaktikanta Das voted to increase the policy repo rate by 50 basis points. Dr. Ashima Goyal voted to increase the repo rate by 35 basis points. 16. Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Dr. Ashima Goyal, Dr. Rajiv Ranjan, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Shri Shaktikanta Das voted to remain focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. Prof. Jayanth R. Varma voted against this part of the resolution. 17. The minutes of the MPC’s meeting will be published on October 14, 2022. 18. The next meeting of the MPC is scheduled during December 5-7, 2022. Voting on the Resolution to increase the policy repo rate to 5.90 per cent

Statement by Dr. Shashanka Bhide 19. The global macroeconomic conditions have become adverse for growth and stability, particularly for the EMEs. While there are clear signs of slowing growth momentum in the economies across the world, inflation continues at much higher rates than the target for many countries. The uncertainty due to the Russia-Ukraine war has continued impacting the energy supplies and prices. While the COVID-19 pandemic has weakened, sporadic surges in some major countries are raising concern. Global monetary policy tightening to contain inflation pressures has increased the potential for significant global growth deceleration and volatility in financial markets. Declining export opportunities while imports remaining relatively high have added to the adverse external environment for the energy importing EMEs. 20. The CPI inflation in India, year-on-year basis, after a run of 7 per cent or more between March and June 2022, dropped to 6.7 per cent in July only to rise to 7 per cent again in August. With the exception of a few product groups, the high rate of price rise was widespread. Food & Beverages and fuel & light sub-groups of the CPI registered YOY rates above 7 per cent throughout this period from March to August, with the exception of a rate of 6.7 per cent in the case of food & beverages in July. Only in the case of housing and pan, tobacco and intoxicants, among the major categories of CPI, with a combined weight of 12.45 per cent in the CPI, the inflation rate was below 4 per cent during the period, with the exception of housing price index which rose by 4.1 per cent in August. Among the other remaining sub-categories, clothing and footwear registered inflation rate of about 9 per cent and the other remaining consumption items constituting ‘miscellaneous’ sub-category registered inflation rate of above 7 per cent in March and April followed by lower rates of 5-7 per cent in the subsequent May-August period. However, there was a decline in the month over month momentum of the overall CPI in May 2022 and it remained steady during June-August. 21. The policy response across the world has been to tighten monetary policy. This policy stance is expected to continue to achieve inflation targets. 22. Persistence of the higher rate of price increase at commodity and sectoral levels in the domestic market is on account of both the direct or spill-over effects of higher international market prices and also the domestic factors. Any decline in prices at the consumer level appears to be restrained by elevated levels of input prices although RBI’s enterprise surveys indicate that the input price pressure is expected to ease in the second half of the current financial year. 23. The RBI survey of households conducted in September 2022 on price expectations indicates expectations of continued high rate of inflation, with the average expected inflation rate being higher than in the survey conducted in July 2022. Inflation rate is also expected to be higher 3-months ahead and one-year ahead compared to the prevailing situation. The expectations of future price readings appear to be affected more by the present conditions than the likely impact of the decline in the commodity prices in the international markets. 24. The survey of enterprises (Industrial Outlook Survey) conducted by RBI in September 2022 reflects some relief on selling prices in H2:FY2022-23 as the proportion of respondents who expect selling prices to rise drops compared to Q2: FY 2022-23. Although financing costs are expected to increase, other input cost pressures are expected to decline. The Wholesale Price Index, reflecting the price conditions at the producer level, has registered double digit rate of increase YOY basis in July and August. While there is a variation in the price changes across the broad range of commodities, in a few major categories of commodities, the price rise is significant. In the case of vegetables, fruits, crude petroleum, petrol, diesel, LPG and electricity, the WPI increased at double digit rates in July and August. In the case of cereals, the increase was 9.8 per cent in July and 11.8 per cent in August. The impact of decline in international market prices on domestic prices is yet to pass through to the domestic consumer prices. 25. The rainfall in the monsoon period of June-September has exceeded the Long Period Average by the last week of September although the rainfall has been deficient in parts of the eastern and north-eastern regions for much of the monsoon period. The monsoon rains in the aggregate have improved the rabi crop prospects. Food commodity prices in the consumption basket will be subject to the size of the kharif harvest in the short run. 26. In the context of continued high inflation rate, the monetary policy rate has increased between May and August 2022. While the impact of this increase is beginning to affect the lending and deposit rates of the banking sector, its main impact on inflation would be through expectations of a decline in future inflation rate and on the aggregate demand. There are of course other factors such as the slowing down of the global economy and its impact on exports and aggregate demand. At this juncture, the adverse impact on aggregate demand may be insulated by the seasonal factors such as the festival season demand and the kharif crop harvest. 27. The Q1: FY2022-23 estimates of national income by the NSO place constant prices GDP growth at 13.5 per cent over the same period in the previous year. This is lower than the RBI’s projection of 16.2 per cent provided in the August meeting of the MPC. Despite the lower than the projected growth, it reflects sustained improvement in growth over the pre-pandemic output level of 2019-20 that began in Q2:FY2021-22. Both Private Final Consumption Expenditure and Gross Fixed Capital Formation, two major components of aggregate demand, registered sharp increase in Q1:FY2022-23 YOY basis. In this sense, the overall growth momentum appears to have been sustained in Q1. 28. Given the lower estimates of GDP growth for Q1, there is uncertainty over sustaining the growth momentum needed to achieve growth of 7.2 per cent for the full year, projected in the August MPC meeting. There are also signs of weakness in demand conditions in the qualitative results of the RBI surveys of Enterprises (Industrial Outlook). The overall Consumer Confidence Index as per the Consumer Confidence Survey (urban households) shows optimism for one-year ahead expectations, albeit, prevailing conditions are seen to be pessimistic. The increase in consumption expenditure over the previous year and one-year ahead expectation is more widely shared with respect to ‘essential expenditure’ as compared to ‘non-essential expenditure’. The expectations of overall business outlook over the remaining quarters of FY 2022-23, based on the Enterprise Surveys for September 2022 reflects optimism but also divergence in sentiments in manufacturing, services and infrastructure sectors. In this context, the revised GDP growth projection for FY 2022-23 is now at 7.0 per cent compared to 7.2 per cent in August. The quarterly growth rates for the year are provided in the Resolution. 29. In sum, there are significant uncertainties over the trajectories of growth and inflation. On the growth front, the COVID-19 pandemic related supply side constraints do not appear to be significant. Improvement in private investment and consumption spending would require price stability. The CPI inflation rate has continued to be high – above/in excess of 6 per cent, from January 2022 onwards. While there are indications of decline in the momentum of price rise, sustaining this decline in momentum is crucial for achieving inflation and growth objectives. To align the inflation expectations with the policy target rate of inflation, further increase in policy rates is necessary at this juncture. 30. I vote to increase the policy repo rate by 50 basis points to 5.9 per cent. I also vote to remain focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. Statement by Dr. Ashima Goyal 31. To start with global factors, major advanced economy central banks over-stimulated after Covid-19 and are over-reacting to inflation now, creating excess volatility in cross border flows to emerging markets (EMs). Forward guidance, whether hawkish or dovish, is harmful in such uncertain times. Being data-based allows real sector changes to counter the effect of interest rates on markets. 32. There are two mitigating factors for India, however. First, after an initial extreme reaction, cross border flows discriminate on a country basis. As commodity prices soften with a global slowdown, some of the investors who had left India because of its vulnerability to commodity inflation will return. Second, India still retains policy space for smoothing global shocks. Domestic demand can counter falling export demand. It is important for policymakers to stay calm to moderate fear and over-reaction. 33. Turning to the domestic situation, global commodity price softening affects WPI more initially. CPI is rising because of a cereal and end monsoon food price spike. As a result household inflation expectations rose, while those of firms fluctuated around 5% according to the IIM Ahmedabad survey. Rising uncertainty shows in the increasing dispersion of household inflation expectations. But firms still see inflation at 5.5% by mid-2023. 34. While India has one of the highest year-on-year growth rates in the world there are some signs of slowing down. Quarter on quarter GDP contracted in Q1. The OECD points out that seasonally adjusted Indian quarter on quarter growth was the lowest after China and Poland. It is uncertain if domestic demand will sustain after the festival spike. RBI consumer surveys show 45% of households reported no increase in income levels compared to a year ago. 35. Although the large pandemic-time repo rate cut is reversed, we are not yet at the terminal rate. Demand reduction has to contribute, along with other measures, to lowering the current account deficit. A firm monetary policy reaction to inflation exceeding tolerance bands helps anchor expectations. The repo rate has to rise more. But should the rise be taken upfront or staggered over time? We examine the arguments for and against frontloading. 36. When behaviour is forward-looking front loading can pre-empt inflationary pressures. But if lagged effects of monetary policy are large, as in India, over-reaction can be very costly. Harmful effects become clear too late and are difficult to reverse. Gradual data-based action reduces the probability of over-reaction. Taking Indian repo rates too high imposed heavy costs in 2011, 2014 and 2018. A credit and investment slowdown was aggravated and sustained. It is necessary to go very carefully now that forward-looking real interest rates are positive. 37. The sacrifice of output from tightening is low if unemployment is low and there is excess demand. Setting rates to reduce excess demand to zero has little output cost and the need for future rate hikes are reduced. In India, however, unemployment is high. That there is no second round inflation from wage rise points to slack labour markets. Employment is just recovering from a series of global shocks and demand may be slowing. 38. High uncertainty also calls for slow steps. If demand slows anyway, less policy tightening will be required. That both inflation and growth were slightly lower than last quarter RBI projections may indicate the effect of tightening was underestimated. It is necessary to monitor the softening of commodity prices. If they slump real rates can shoot up too high as in 2014-15. 39. If inflation expectations are unanchored a large sacrifice may be called for to reverse them. But in EMs communication has more impact. Continuing supply-side action, global softening and transparent communication about these factors all help anchor inflation expectations. If the target is headline inflation with a large commodity component for which fiscal action has greater impact there is more responsibility on the government to act. The Indian government has demonstrated commitment to lowering costs of living and to improving infrastructure. 40. A BIS study1 of past country experience including 6 EMs found frontloaded actions tend to be followed by soft landings but average 45% of the policy rate rise was frontloaded in soft landings and the mean nominal rate hike was 2%. Large hikes were required in India to reverse steep pandemic-time cuts. Since that is completed, going slow now will allow policy to be agile and data-based. Extremes are always dangerous; 100% front loading can easily overshoot. Moderation is better. 41. Households tend to have a stagflationary view, so they expect inflation to rise when growth falls2. In addition, Indian households expect inflation to increase if the repo rate increases3. Excessive rate rises will not make inflation targeting credible if they are unable to lower supply-side inflation and instead raise costs as demand and investment falls. 42. Most analysts are arguing for a 50 bps rise just to preserve a spread with US policy rates. This is a fear driven over-reaction. In the mid-2000s the spread was less than 150 bps and there were large capital inflows. In the past 2 years spreads of above 300 bps have not brought in debt flows. If the terminal Fed rate is 5%, will it require we raise ours to 8%? The carry trade is not a stable source of financing. India has earned enough independence to protect itself from policy errors of other nations. 43. In view of all these considerations, and to signal tapering of action, I vote for a 35 bps rise in the repo rate. Both RBI and SPF headline forecasts for Q1 FY2023-24 are around 5%, implying the real rate will be approximately 0.75% with the repo rate at 5.75%. This is almost one, and can exceed unity if the fall in inflation is larger. This could be dangerous if growth slows. The MPC has to focus on the 6 month to one year ahead real rate, as this is the horizon where monetary policy will have its greatest impact. 44. Moreover, as banking liquidity is tightening, there will be more pass through. Over time LAF tools and forecasting of liquidity shocks should develop to the point where a neutral MPC stance implies weighted average money market rates are maintained in the middle of the LAF corridor. At present I vote to continue with the ‘withdrawal of accommodation stance’ since durable liquidity is still in surplus. This, together with adequate adjustment of short-term liquidity, is required to counter global quantitative tightening (QT) and possible outflows, as required. The very slow pace of QT compared to the large surplus created, along with selective CB interventions, may be sufficient, if we are lucky, to prevent financial instability despite the rapid coordinated global rise in policy rates. Statement by Prof. Jayanth R. Varma 45. I wrote in my August statement that further withdrawal of accommodation is warranted beyond the rate increase in that meeting. However, I also indicated that we may be beginning to approach the terminal repo rate. My view remains largely the same today, and based on this, I think the MPC should now raise the policy rate to 6 percent and then take a pause. 46. A pause is needed after this hike because monetary policy acts with lags. It may take 3-4 quarters for the policy rate to be transmitted to the real economy, and the peak effect may take as long as 5-6 quarters. If we raise the repo rate to around 6 percent at this meeting, that would be a cumulative increase of around two percentage points in the space of just four months. Even this understates the extent of monetary tightening, because, a few months ago, money market rates were close to the reverse repo rate (65 basis points below the repo rate). Taking this into account, the full magnitude of monetary tightening would be well over 250 basis points. 47. Much of the impact of this large monetary policy action is yet to be felt in the real economy. In fact, much of the policy rate action is yet to be transmitted to even the broader spectrum of interest rates. For example, less than a third of the increase in the repo rate during April-August has been transmitted to retail bank deposit rates. Bank deposit interest rates play a critical role in stimulating savings, dampening consumption demand, and thereby mitigating inflationary pressures. We should hopefully see more of this transmission in ensuing quarters. While there has been much higher transmission from policy rates to lending rates, the transmission from lending rates to the real economy would also take time. 48. All this means that it is too early to know whether the policy action so far is sufficient or not. It may well turn out that even more monetary tightening is required, but it does make sense to wait and watch to see whether a repo rate of around 6 percent is sufficient to glide inflation back to target. If we were to continue to tighten without a reality check, we would run the risk of overshooting the repo rate needed to achieve price stability. It is true that inflation is currently well above 6 percent. However, since monetary policy acts with lags, what is relevant is the inflation forecasts 3-4 quarters ahead. Both the RBI’s forecasts and the survey of professional forecasters show inflation falling to around 5 percent in the first quarter of the next financial year. Relative to this forecast, a policy rate of around 6 percent would not only be a positive real rate, but also likely above the neutral rate. 49. In my view, it is dangerous to push the policy rate well above the neutral rate in an environment where the growth outlook is very fragile. While the level of economic output has recovered to pre pandemic levels, it remains well below the pre pandemic trend line. Tightening global financial conditions and recessionary fears in advanced economies are acting as drags on the domestic economy as well. Weakening export growth means that economic growth has to be driven by domestic demand which is still not sufficiently robust. Much of the hope for economic growth rests on the possibility of a revival of private investment in response to rising capacity utilization. We should be careful to ensure that an unreasonably high real interest rate does not thwart this much needed upswing of the investment cycle. Compared to the previous meeting, the upside risks to inflation have abated with a moderation in crude oil prices and continued weakness in other commodity prices. 50. I have given careful consideration to the extensive analyst commentary suggesting that a terminal repo rate of 6.25 or 6.50 percent is appropriate. Much of this analysis is from the perspective of the balance of payments. It is true that in the past (notably in 1998 and in 2013), India has very successfully used interest rates to defend the currency. However, all these episodes were before the inception of an inflation targeting MPC in 2016. The statutory mandate restricts the MPC to consider only two factors while setting interest rates - inflation and growth. It was a conscious legislative choice to let monetary policy be dictated by domestic economic considerations, and leave the external sector to be managed using other instruments. This means that the MPC cannot be guided by the effect of global monetary tightening on the interest rate differential. 51. My votes on the MPC resolutions are informed by these considerations. For the first resolution on the quantum of the rate hike, I considered three alternative choices: 35, 50, and 60 basis points corresponding to repo rates of 5.75, 5.90 and 6.00 percent. I think that 5.75 per cent would be well below the terminal repo rate, would leave the task of monetary tightening unfinished, and make it necessary to hike rates again in the next meeting. My preference is clearly for a front loaded hike to the 6 percent level that I have argued for in the above paragraphs. The majority of the MPC has chosen 5.90 percent which is only slightly below my preferred rate of 6 percent. As I have explained in past statements, 10 basis points is not material and I am happy to go along with the majority of the MPC on this issue. Therefore, I vote in favour of increasing the policy repo rate by 50 basis points to 5.90 percent. However, I vote against the second resolution because in my view the MPC should now pause rather than focus on further tightening. Statement by Dr. Rajiv Ranjan 52. Central banks across the globe continue their fight against inflation this year with more than a dozen central banks hiking rates by 75 bps or even more in one go. While global financial markets are witnessing the immediate brunt with associated spillovers for emerging markets including India on account of risk-off sentiment and US dollar strength, ‘historic’ global growth slowdown is the medium-term risk that the world economy has to face. 53. India is in a much better position relative to many other parts of the world. Growth is resilient, and that is also encapsulated in upgrade in growth forecasts for Q2, Q3 and Q4 of 2022-23. Although exports are vulnerable to global growth slow down, it could be offset by some favourable spillovers from lower global commodity prices coupled with other factors alluded to in the following paragraphs. 54. For Q1:2022-23, National Statistical Office (NSO) estimate of real GDP growth at 13.5 per cent was lower than our projection of 16.2 per cent. Despite a strong pick up in private consumption and investment which supported aggregate demand in Q1, lower growth in government consumption and higher drag from net exports contained growth in real GDP. High growth in real imports - with lower-than-expected deflator inflation at 13.7 per cent despite sharp rise in import prices - outpaced real export growth significantly. 55. Again, growth in contact-intensive services as reflected by GVA growth in trade, hotels, transport, communication and services related to broadcasting also fell short of expectations. While this sector had exceeded its pre-pandemic level by 1.7 per cent in Q4:2021-22 in a quarter marred by Omicron, it slipped below its pre-pandemic level by 15.5 per cent in Q1:2022-23 which was a relatively normal quarter. Assuming this sector could have just reached its pre-pandemic level in Q1:2022-23 (i.e., at the Q1:2019-20 levels), real GVA growth would have been 16.1 per cent during the quarter. Notably, this sub-group accounted for about one-fifth of the GVA in the pre-pandemic period. 56. Accordingly, the projection for H2:2022-23 has been revised upwards. It is also expected that the economic activity is likely to sustain momentum with full-fledged celebration of festivals after two years on the back of buffers of excess household savings, which will aid private consumption. Even though household’s financial savings have normalised from a peak level of 12.0 per cent of GDP during 2020-21 to 8.3 per cent in 2021-22, it is estimated that households still had an excess saving of around 7 per cent of GDP at end-March 2022 - based on their net worth which is higher than the level at end-March 2020.4 As consumption gathers traction and capacity utilisation surges beyond a threshold, this could fuel investment – the second engine of growth. The real GDP growth for 2023-24, based on our macroeconomic model, is projected at 6.5 per cent.5 India assuming G-20 presidency in 2023 is likely to support economic activity with large infrastructure and tourism related investment. 57. Since the last bi-monthly, headline CPI inflation after moderating to 6.7 per cent in July edged up to 7.0 per cent in August. Even so, month-over-month change in headline CPI (or price momentum) was steady at around 0.5 per cent during June-August 2022 and two-way movement in inflation was brought about by base effects. Food and CPI core (CPI excluding food and fuel) drove price momentum in recent months, with core inflation remaining sticky around the upper tolerance threshold of 6 per cent. Food inflation registered a significant pick-up in August on accentuation of price pressures in cereals along with pulses, milk, vegetables and spices. Various exclusion-based measures of core were in range of 5.9 per cent to 6.2 per cent in August. In fact, all trimmed mean measures of core inflation edged up in August and were in the range of 6.2 per cent to 6.8 per cent, with weighted median registering a sharp 80 bps pick-up in August to 6.5 per cent. In some ways a pick-up of price pressures in core in August is also visible from core diffusion indices which firmed up in August. Inflation expectations also remain elevated. 58. There is, however, reason for confidence on inflation slowing down within the tolerance band next fiscal, given lagged impact of RBI rate hikes and easing of supply constraints. RBI’s quarterly model-based projection shows that inflation rate during 2023-24, on an average, will be 5.2 per cent. 59. In the current macroeconomic mix, while a rate hike in this meeting is imminent, the choice between a 35 to 50 bps is a close call. Given the growth-inflation dynamics, my vote is for an increase in repo rate by 50 bps and continue with the policy stance of withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. First, with current inflation level and the uncertainty around it, mooring of inflation expectations is important to restrain the broadening of price pressures and enhance credibility of the central bank, the benefits of which I had explained in my last minutes. Second, by showing continued commitment to inflation target, monetary policy seeks focused attention on its ‘inflation mandate’. As we are living in an information-rich world, we may get carried away by certain information-fraction and tend to form expectations, impacting prices, consumption and investment. The committed monetary policy actions fix the attention of various agents in the economy on the ‘inflation mandate’ even when the current inflation is elevated. This, in turn, will again help to anchor inflation expectations.6 Third, the resilient growth about which I mentioned before provides us the space to act. Fourth, despite the recent empirical evidence supporting the perceived wisdom that real neutral rates declined both globally as well as in India7, we need to keep in mind the level of inflation and surplus liquidity conditions prevailing at this juncture. 60. Reflecting the increases in the policy repo rate, the weighted average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans of SCBs has increased by 82 basis points during the period May to August 2022. The increase in share of external benchmark lending rate (EBLR) linked loans (46.9 per cent as at end-June 2022) coupled with shorter reset period for such loans have significantly improved the pace of transmission to WALR on outstanding loans. On the liability side, pass-through to term deposit rates is higher, if one considers both retail as well as bulk deposits. The extent of transmission is expected to improve further with the upward revision in interest rates on some small savings instruments. 61. In a scenario where growth momentum gains further traction and inflation pressures are projected to remain elevated over the remaining part of the year, before registering a moderation by Q1:2023-24, monetary policy has to persevere with its exit from accommodation to ensure that calibrated policy rate hikes dampen inflation expectations and firmly establish our commitment to price stability. This would help achieve the optimal mix of growth and inflation which will set the foundations for a high growth trajectory over the medium term. Statement by Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra 62. Central banks race in lockstep to raise policy rates by much more than their own historical experience. After all, current levels of inflation haven’t been seen in decades. Are they overshooting, or overdoing it? 63. They are balancing the prospects of a recession against the risks of inflation remaining elevated and persistent. Given their mandates and the credibility they work hard to earn (in the pandemic, they prioritised revival over price stability which cannot be faulted, but it is), they prefer now to err on the side of hawkishness in their determination to bring inflation to targets, fearing a 1970s redux. 64. This inflation shock defeats conventional forecasting models. The parameters that characterise recent developments are far outside the ranges predicted by the conventional models. No one really knows what is too far or what is far enough in this environment. Central banks, therefore, adopt a risk minimisation strategy, ensuring they eradicate inflation, while allowing them to correct course and lower interest rates later if necessary. 65. Even so, currently available projections of inflation suggest that the real policy rates will remain negative up to close of 2022. Hence, more forceful tightening of monetary policy in 2023 may be required if terminal rates have to be achieved. This is being reflected in aggressive forward guidance, which has effectively restrained the relief rally that followed in the wake of pricing in of large rate actions in the recent past. Currency slides have become cliff events. Equities and bonds alike are selling off. Extreme risk aversion grips markets and investors. 66. Inflation management is suddenly complicated by the crystallisation of the impossible trinity. The conduct of domestically oriented monetary policy is becoming hostage to unidirectional exchange market volatility and mobile capital flows seeking safe haven. Recession risks may be darkening the horizon, but more immediately, global macroeconomic and financial stability is under threat. No country is immune. Systemic central banks should pay heed to the possibility that today’s spillovers can become tomorrow’s spillbacks. 67. For net commodity importers like India, with over a third of the CPI being imported, a negative terms of trade shock convolutes macroeconomic management. As current account deficits widen and capital flows turn fickle, reserve depletions become not just sources of forex liquidity to a risk wrung market but also instruments of stabilising expectations – the RBI stands for stability. Minimising volatility in the exchange rate becomes important from two points of view: (a) limiting risks to financial stability from foreign exchange exposures and pressures on margins of corporations; and (b) ensuring orderly functioning of financial markets so that volatility does not translate into financial stability risks. Accumulations during happier times have proved to be prudent. 68. Spillovers are global and overwhelming; however, the responsibility for securing stability is national. Each country is on its own. 69. In India, the moderation in inflation that had commenced in May 2022 has been interrupted by supply shocks which may extend into September. Although these shocks appear transitory at this juncture – barring energy prices which will be shaped by the evolving geopolitical situation – it is critical to remain watchful about second order effects if the shocks persist or recur. What is disquieting, however, is that inflation stripped of these transitory effects has become unyielding and tightly range bound around the upper tolerance band of the inflation target. The RBI’s forward-looking surveys suggest that selling prices in manufacturing and services may rise further as pass-through from input cost pressures remains incomplete. Exchange rate volatility is amplifying these core price pressures, especially in view of key import prices being invoiced in the US dollar. Inflation expectations are rising, with signs that they are becoming unanchored over a one year ahead horizon. Taken together with a closing output gap, rising capacity utilisation in manufacturing, surging demand for services and the pick-up in spending as the festival season nears, monetary policy must move to red alert. 70. At this critical juncture, monetary policy has to perform the role of nominal anchor for the economy as it charts a new growth trajectory. The focus should be on being time consistent in aligning inflation with the target. In this context, front-loading of monetary policy actions can keep inflation expectations firmly anchored and balance demand against supply so that core inflation pressures ease. It will also reduce the medium-term growth sacrifice associated with steering inflation back to target because it is being timed into the strengthening of the recovery of the domestic economy that is underway and likely to gather further momentum as the year progresses. 71. Accordingly, I vote for increasing the policy repo rate by 50 basis points and for maintaining the stance of withdrawal of accommodation. Statement by Shri Shaktikanta Das 72. The world is in the eye of a new storm originating from aggressive monetary policy tightening and even more aggressive forward guidance from advanced economy (AE) central banks. This has resulted in a tightening of global financial conditions, extreme volatility in financial markets, risk aversion among investors and sharp appreciation of the US dollar. Such market turmoil on top of globalisation of inflation and deglobalisation of trade has hugely negative consequences for emerging market economies (EMEs). Even in AEs, the narrative is increasingly shifting from stagflation to possible recession. These developments are taking place even as the world is still grappling with the shocks from COVID-19 and the conflict in Ukraine. 73. Amidst all these, the Indian economy presents a picture of resilience with macroeconomic and financial stability. The balance sheet of key stakeholders like corporates and banks remain strong. In an interconnected world, however, the Indian economy is obviously impacted by the unsettled global environment. There are pronounced consequences not only for our domestic inflation and growth dynamics, but also financial markets. 74. On the growth front, economic activity is steadily improving. There are, however, mixed signals. While high frequency indicators are showing continued momentum in activity, global factors are putting pressure on external demand. The growth projection of 7.0 per cent for 2022-23, therefore, carries risks which are broadly balanced. Whatever be the unfolding scenario, India is expected to be among the fastest growing major economies in the world. 75. Headline inflation, on the other hand, remains elevated and above the upper tolerance band of the target. As per current projections, headline CPI is expected to moderate to 5.8 per cent in Q4 of 2022-23 and further to 5.0 per cent in Q1 of 2023-24. The future trajectory remains clouded with uncertainties arising from continuing geopolitical conflicts, possibility of further supply disruptions, volatile financial market conditions and domestic weather related factors. 76. Overall, I remain optimistic about the future prospects of the Indian economy, its resilience and capacity to deal with the current and emerging challenges. We need to do whatever is necessary and under our control to restrain broadening of price pressures, anchor inflation expectations and contain second round effects. The need of the hour is calibrated monetary policy action, with a clear understanding that it is required for sustaining our medium-term growth prospects. Accordingly, I vote for raising the policy repo rate by 50 bps. As regards the stance, I vote for remaining focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. It is important to note that even though the policy rate has moved to pre-pandemic levels, the overall monetary conditions taking into account the liquidity position and the inflation remain accommodative. The net liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) continues to be in surplus for more than three years. Liquidity in the system may also be seen in totality taking into account all moving variables including excess CRR and SLR holdings of banks, and revenue and expenditure pattern of the government. 77. Going forward, monetary policy needs to remain watchful and nimble, based on incoming data and evolving conditions. We should remain vigilant on the inflation front while strengthening our macroeconomic fundamentals. The financial and external sectors also continue to be under the Reserve Bank’s close watch. In the final analysis, there is optimism and confidence around the India growth story and our current action is expected to add credence to that narrative. (Yogesh Dayal) Press Release: 2022-2023/1043 1 Boissay, F., F. De Fiore and E. Kharroubi. 2022. “Hard or soft landing?” BIS Bulletin No. 59. July. 2 Coibion, O., Y. Gorodnichenko, and M. Weber. 2022. “Monetary policy communications and their effects on household inflation expectations.” Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1086/718982 3 Goyal, A. and P. Parab. 2021. “What Influences Aggregate Inflation Expectations of Households in India?” Journal of Asian Economics 72 (February) 101260. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1049007820301408 4 As per estimates based on Table 50 (a) and (b) of RBI Bulletin, September 2022. 5 Monetary Policy Report, September 30, 2022. 6 Simon, H. A. (1971). Designing organizations for an information-rich world. In M. Greenberger (Ed.), Computers, Communications, and the Public Interest. Johns Hopkins Press. 7 S. Pattanaik, H.K. Behera and S. Sharma ‘Revisiting India’s Natural Rate of Interest’, RBI Bulletin, June 2022. |

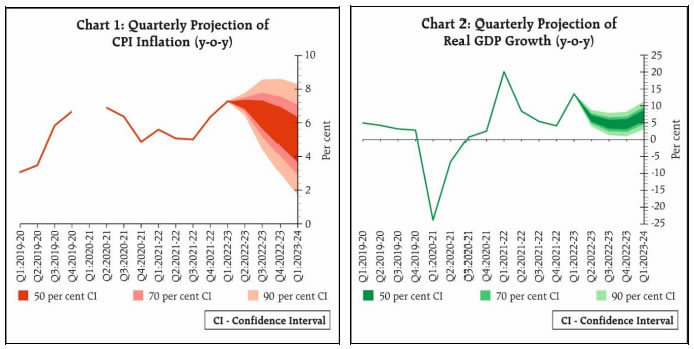

ପେଜ୍ ଅନ୍ତିମ ଅପଡେଟ୍ ହୋଇଛି: