IST,

IST,

Governance, Efficiency and Soundness of Indian Banks

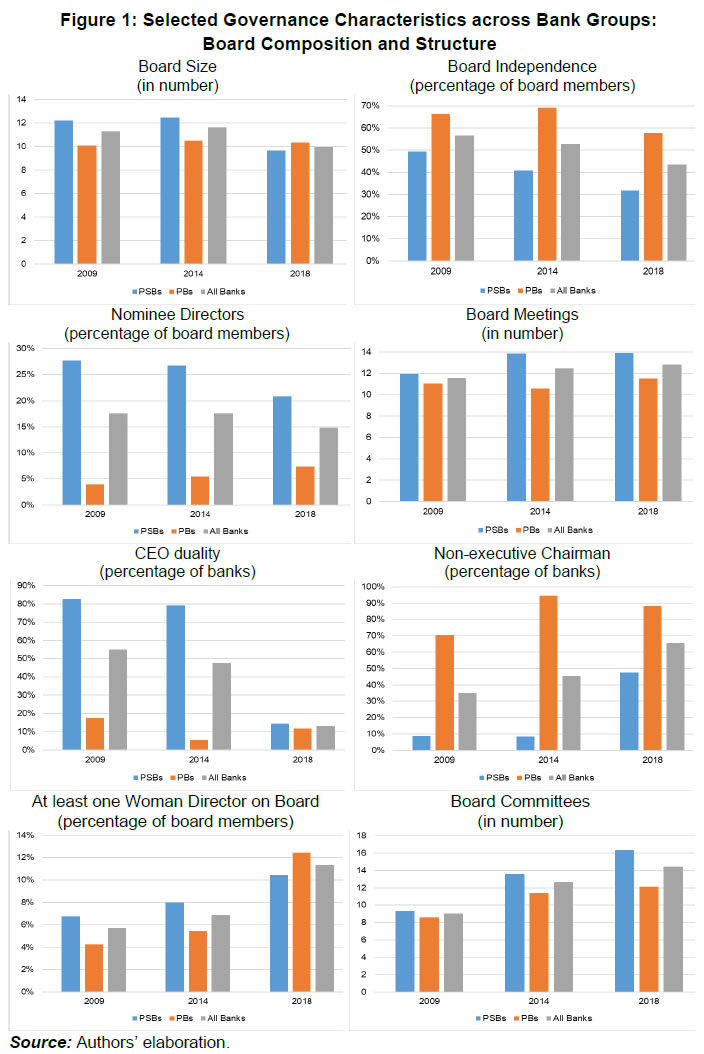

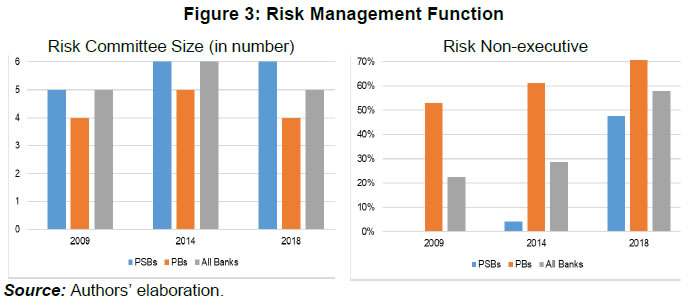

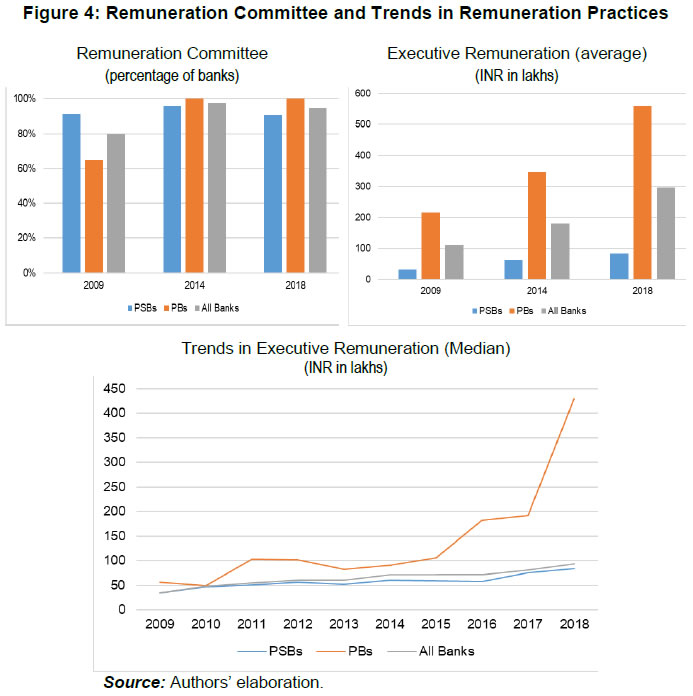

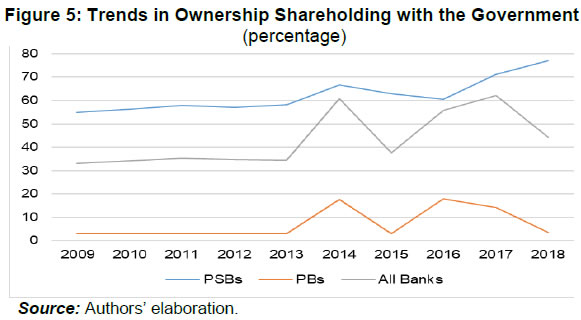

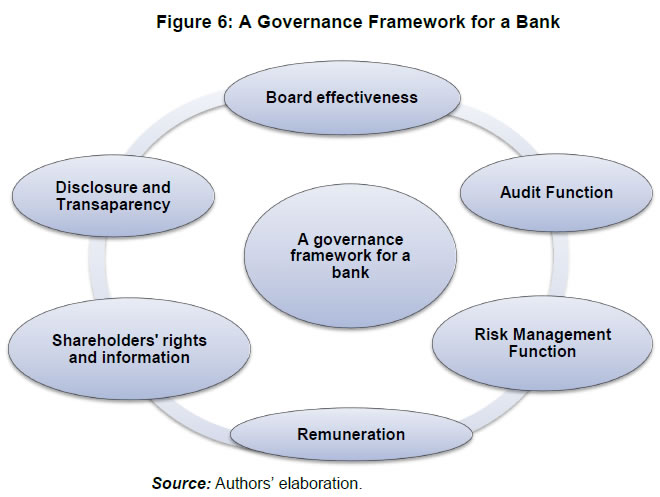

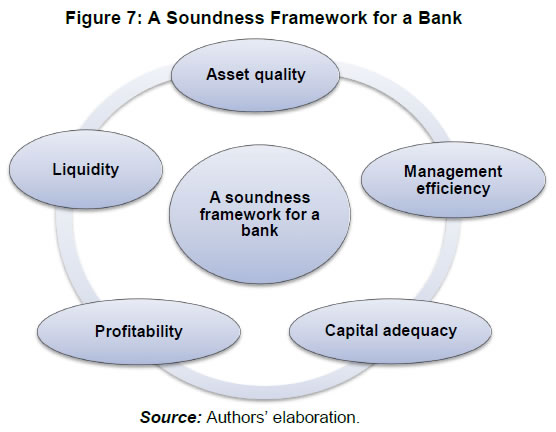

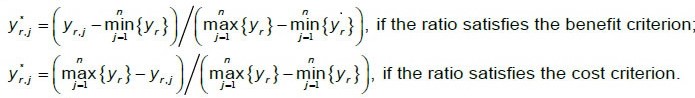

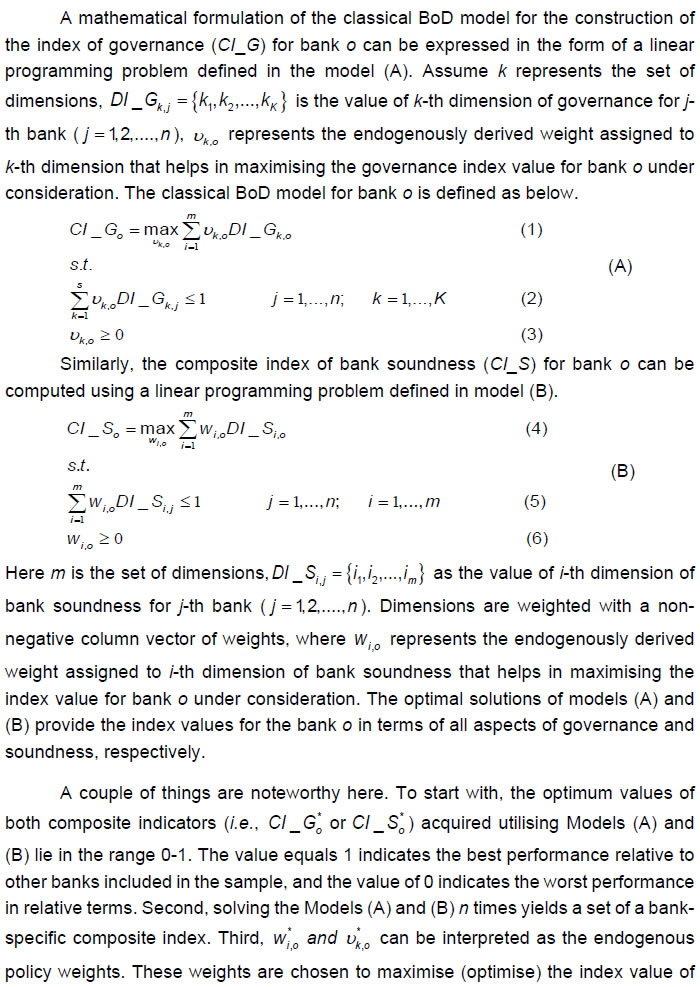

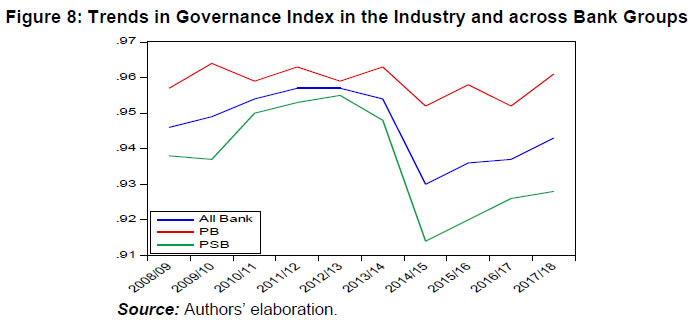

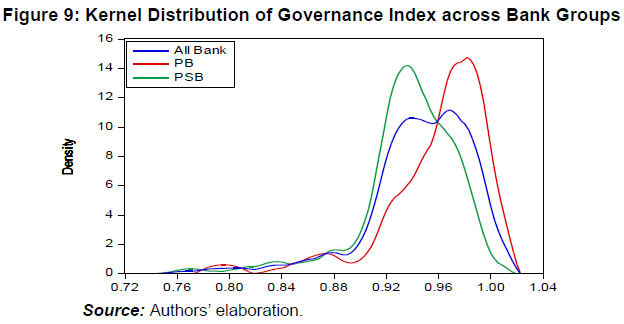

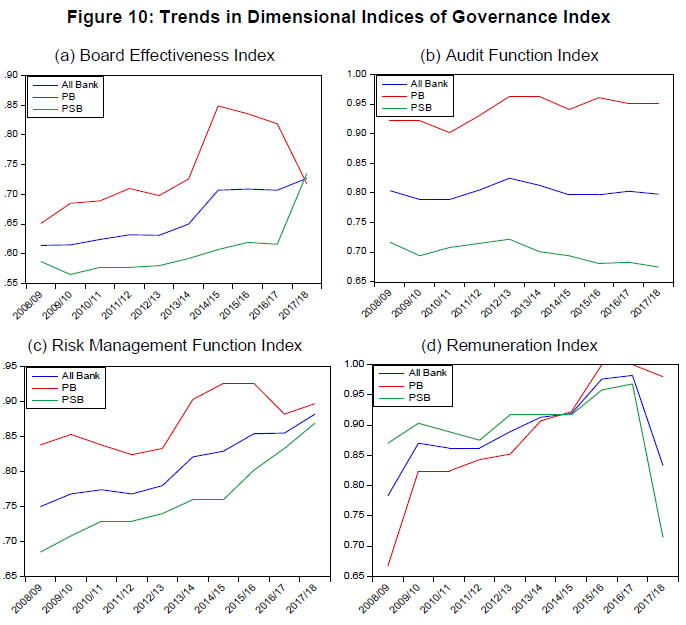

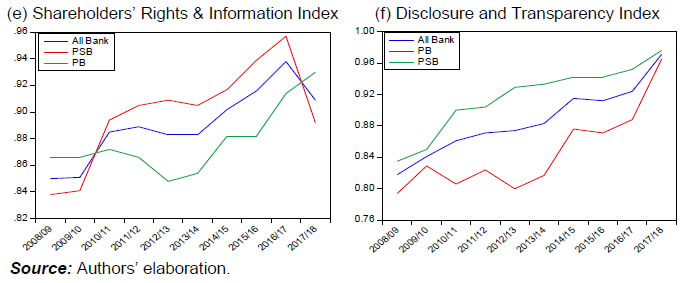

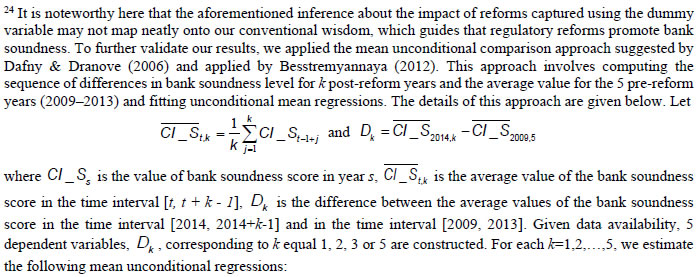

Governance, Efficiency and Soundness of Indian Banks by Rachita Gulati1a Abstract The report delivers the response to the key research question: do governance and efficiency explain bank soundness in India? The subject of this report is of utmost significance for an emerging economy like India, but until now, it falls in little-investigated research territory. An empirical investigation is done using the unique panel dataset for the period spanning from 2009 to 2018. The study built the bank-wise non-parametric indices of corporate governance and bank soundness utilising the “Benefit-of-the-Doubt” approach and estimated the risk-adjusted profit efficiency scores for banks using the data envelopment analysis approach. Based on the publicly available information on banks, the empirical connection between governance, efficiency and soundness of banks is explored using the dynamic panel data econometric models. The empirical results uncover that although Indian banks have made impressive progress in adhering to the mostly mandatory corporate governance norms/standards in the last few years, the existing compliance level is not adequate to label the current governance structure as a “socially efficient” structure. The analysis of sampled banks reveals noticeable asymmetries in the policy priorities across ownership groups on underlined dimensions of governance and soundness. The results of the econometric estimation are robust, and reveal that the governance structure crucially determines bank soundness, and profit efficient banks are sound enough to hold the capability of absorbing shocks. The key policy implication stemming from the empirical outcomes is that inadequate regulatory adherence by banks with governance norms would be costlier and may have destabilising impact on the banking sector. JEL Codes: G21, G28, G38 Keywords: governance; bank soundness; profit efficiency; composite index; benefit-of-the-doubt approach; data envelopment analysis; dynamic panel econometric methods; panel quantile regression; Indian banks. Acknowledgments It is our privilege to express a deep sense of gratitude to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for sponsoring this study on “Governance, Efficiency and Soundness of Indian Banks” as part of the Development Research Group (DRG) Studies under the aegis of the Department of Economic Policy and Research (DEPR). We deeply acknowledge our thanks to Dr. Rajeev Ranjan (then Officer-in-Charge, DEPR) for their encouragement to pursue this research. Thanks are also extended to Dr. Jai Chander, former Director, DRG, DEPR, and his team members for their valuable support at the various stages of the completion of this study. The report has also been benefitted from valuable comments of anonymous reviewers and suggestions of Shri Sitikantha Pattanaik (then Adviser-in-Charge), Dr. Arvind Kumar Jha (then Director, DRG), and Dr. Snehal Herwadkar (Director), RBI, and their team members on various drafts. We also acknowledge the comments and suggestions from the Department of Supervision and Dr. Pallavi Chavan (Director, DRG, DEPR), which have helped improve the quality of the report. Thanks are also to all the student assistants who helped us with this project. We are, however, responsible for all the errors that remain with the usual disclaimers. Rachita Gulati Executive Summary This report answers the key research question: do governance and efficiency explain bank soundness in India? This subject is of significant interest to all the stakeholders. However, so far, there exists no sufficient evidence in this regard for the Indian banking industry. In particular, this study aims to examine the nexus between governance, efficiency, and soundness using a unique and new bank-level panel dataset obtained from publicly available information in the individual bank’s annual report for the period from 2008-09 to 2017-18. The research objectives are accomplished by constructing the non-parametric “Benefit-of-the-Doubt (BoD)” based composite indices for bank governance and soundness. An index of governance is built using 48 governance norms/standards, covering six key dimensions of bank governance: “board effectiveness”, “audit function”, “risk management”, “remuneration”, “shareholders’ rights and information”, and “disclosure and transparency”. For building a composite index of bank soundness, the study employs 14 ratio indicators encompassing five distinct dimensions: “capital adequacy”, “asset quality”, “profitability”, “liquidity”, and “management efficiency”. The risk-adjusted profit efficiency scores are calculated using a data envelopment analysis (DEA) model, which accommodates internal risk control variables in line with the ‘optimal’ approach suggested by Simper et al. (2017). The relationship between bank soundness, efficiency and governance is ascertained by using the state-of-the-art dynamic econometric methods for panel data. From the empirical analysis regarding levels and developments of governance and soundness across ownership groups, we reach to the following conclusions. First, albeit banks in India have made significant progress in complying with governance norms in the last few years, the current compliance level is insufficient to label the existing governance structure as “socially efficient”. Second, private banks showed relatively better performance in adhering to governance norms during the study period. Notably, public sector banks (PSBs) stumbled in achieving greater compliance with the dimensions of board effectiveness, risk management, and audit functions. Third, the analysis of trends in soundness levels of banks in India shows that from 2008-09 to 2012-13, the banking industry remained relatively sound before early signs of a decline began to appear in 2013-14. However, this up-turn in the bank soundness was reversed due to endogenous shocks coupled with an economic downturn, and banking groups experienced widened soundness gaps. Fourth, a significant drop in profitability and asset quality caused an increase in the fragility and vulnerability of the Indian banking system in the turbulent period. An assessment of policy priorities divulges that, on average, PSBs accord higher priority to disclosure and transparency, which is followed by the remuneration, and shareholders’ rights and information. In contrast, private banks ascribe a greater focus on audit function, followed by risk management and board quality. On dimensions of bank soundness, PSBs amply focused on management efficiency, while private banks zeroed in on management efficiency, followed by asset quality and profitability. These differences highlight asymmetries in the policy priorities of banks on governance and soundness across ownership groups. The report draws the following inferences while investigating the nexus between governance, efficiency and soundness using the cutting-edge dynamic econometric tools for panel data. First, governance significantly explains bank soundness, and any regulatory non-adherence to selected governance principles would be costly and may undermine soundness of the Indian banking system. Second, profit-efficient banks are sound enough to hold the capability of absorbing shocks, which may reduce destabilising effects. Therefore, to avoid the risk of bank failure in the long-run, business practices that assure sustainable profits with proportionate risk be encouraged. Third, there is a lack of instantaneous recovery in bank soundness may be due to the detrimental effects of many potential exogenous and endogenous shocks to the system. Fourth, government engagement can serve as an implicit assurance and safeguard, only to a point; beyond that, it may not necessarily foster bank soundness. Fifth, positive spillover effects of re-regulation and new regulatory reforms resulting from adverse events (like under-reporting of financial data by banks, inadequate compliance with governance standards/norms, management malpractices, etc.) are not felt immediately. The retrieval process is still in operation in pushing the banking industry back to an erstwhile soundness level. Based on this study's assessment of governance dimensions and norms on bank soundness, we draw attention to the following. First, a prominent emphasis only on stringent compliance with board attributes and a meagre focus on other important dimensions of governance may be costly and impede bank soundness. Second, pro-active regulatory developments in the aftermath of the year 2014 have resulted in increased audit compliance, contributing to greater bank soundness. Third, mere regulatory compliance with risk management principles is not adequate to make a bank sound. Instead, other policy interventions, especially in the form of greater supervisory power to resolution authorities and better compliance on risk governance, may improve soundness. Fourth, better remuneration practices help the board to decide performance-linked compensation packages for executives, lower agency conflicts and enhance bank soundness. Fifth, higher compliance with shareholders’ rights enhances the soundness of banks, and superfluous disclosure might precipitate the risk of being unsound and thus need rationalisation on this front. Finally, quality board meetings, a large proportion of outside directors on the audit committee, and a remuneration committee assist in exercising better controls and averting shocks in the industry. As to the effect of board independence on bank soundness, the impact is observed to be uneven across ownership groups. Finally, the empirical results mentioned in this paper are robust to different estimation models for panel data. Governance, Efficiency and Soundness of Indian Banks In the past few years, particularly since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-09, the regulators, supervisors, and policymakers around the globe have begun to pay greater attention to issues such as bank soundness, bank efficiency, and good corporate governance issues of banks. The raison d'être for this renewed interest involved the colossal effects of the crisis that were brought about in large part by the inadequate bank corporate governance, which created a climate of inertia, caused a massive collapse, and resulted in increased vulnerability and fragility in the banking system (Jokippi & Monnin, 2013). The fall of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) is one of the noteworthy examples illustrating how failure in bank corporate governance can have a lasting impact on a nation’s economic growth. This bank failed mainly because of the lack of sound decision-making abilities of its management executives and other fellow directors on the board. As a result, the government has to bail out RBS with taxpayer money to prevent its collapse. Financial Services Authority Board (2011) describes the economic cost of this bank failure as: “RBS’s failure has imposed large costs on UK citizens… The larger costs arise from the recession, which resulted from that crisis, within which RBS’s failure played a significant role. That recession has caused unemployment for many, losses of income and wealth for many more (p. 6)”. An example such as this illustrates clearly how inadequate bank corporate governance can not only wreak havoc on the bank’s finances, but also have detrimental effects on the economy of a country. Following such instances of bank failures, regulatory and supervisory authorities have been re-evaluating and redesigning banking sector policies with a clear focus on adopting appropriate governance norms to achieve a high level of soundness in the banking system. Such evidence of bank failures and the resulting insolvency in the banking systems of the Western world compelled the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to establish a Financial Stability Unit in 2009 and pressed to include bank stability/soundness as its most coveted goal in the policy formulation. In conjunction with this, a series of recent developments in the Indian banking industry, such as large scale bank frauds, cases of money laundering, as well as the unusual exposure of Indian banks to credit risk, have raised concern over the inadequacies of the governance structure for banks and its ramifications for the soundness and efficiency of the banking industry. RBI has made various steps for furthering sound corporate governance and supervision in the Indian banking system in recent years (RBI, 2014, 2020). Specifically, the transparency and disclosure standards are aligned with international best practices, and the systems of off-line surveillance and prompt corrective action are adopted for promoting bank soundness. Overall, RBI recognised the importance of good governance of banks for achieving higher efficiency and soundness levels and has taken an array of proactive steps in this direction. This is clear from the remark of Mr. Shaktikanta Das, the Governor of RBI, in the foreword of the Financial Stability Report - 2019. In the report, he echoed the significance of good governance of banks by stating that “the importance of good corporate governance across the board is the most significant factor that can promote stability and lift the efficiency of our economy to its full potential”. According to the official statistics by the RBI, the ratios of gross and net non-performing assets as a percentage of total advances have raised significantly from 2.3 per cent and 1.1 per cent, respectively, in 2007-08 to 9.1 per cent and 3.7 per cent in 2018-19 (RBI, 2019a). Additionally, the banking industry registered a total of 6,801 frauds in 2018-19, worth INR 715.43 billion (RBI, 2019a). Regarding banking operations, 53 per cent of these frauds (i.e., 3,606 frauds) are predominantly related to credit lending. In publicly available sources, insider involvement and management “dishonesty” or failure to conduct effective internal and statutory audits or the breach of regulatory guidelines (particularly concerning issuing of letters of credit), or the senior management’s failure to implement an effective strategy for governance or all are hinted at as possibilities for why these frauds occurred. Therefore, it has served as an alarming bell to policy analysts and academic researchers to re-examine the level of existing governance standards and identify the impact of governance and efficiency on Indian banking soundness. Recognising the significance of effective governance for banks and its ramifications, numerous efforts have been made by the regulators and legislators to institutionalise governance mechanisms for banking companies in India (see, for details, RBI 2001, 2002, 2014; Ministry of Corporate Affairs, 2013; SEBI, 2015). It is noteworthy here that the Indian Government has set up an institutional system for bank governance, under their own legal and regulatory statutes; Companies Act (CA), 1956 (as amended in 2009 & 2013), which is based on guidelines established by the M/o. Corporate Affairs; the SEBI under Clause 49 (LODR) Regulations, 2000 (amended in 2005, 2009, 2015 & 2017); and Report of the Corporate Governance Committee, 2017. In the past two decades, the governance structure for banking companies in India has evolved from the “single-aspect,” comprising the board of directors and executive/board committees only, to the “multiple-aspects” including the role of audit, remuneration, nomination, risk management committees, and ownership structure. Nonetheless, Indian banks, especially PSBs, face trouble in the smooth implementation of all layers due to “dual regulation” by the Government of India (GoI) and RBI that has limited their capacity to compete with their private counterparts in terms of profitability and efficiency (RBI, 2001). Against this background, it has become crucial to develop a profound understanding of the degree of effectiveness of governance mechanisms, bank efficiency level, and how they impact the overall soundness of the banking industry in India. As an attempt in this direction, this report responds to the following pertinent research questions: What are the extent of governance compliance, bank efficiency and bank soundness in India? What are the optimal policy priorities of sampled banks regarding underlined dimensions of governance and soundness? In which dimension should a less sound (or less governed) bank focus? Do governance and efficiency explain bank soundness in India? In particular, the report helps to achieve the following research objectives: i) to explore the dynamics of bank governance, efficiency and soundness; ii) to estimate “benefit-of-the-doubt” (hereafter, BoD) based data-driven and endogenously defined optimal policy weights corresponding to the underlined dimensions of soundness and governance for Indian banks; and iii) to examine the relationship between bank governance, efficiency and soundness. It is fundamentally essential to answer these research questions at this critical moment when financial distress and fragility have reached a tangible limit and become a major policy concern for bank regulators. An innovative non-parametric constrained “benefit-of-the-doubt” (BoD) model, as proposed by Cherchye et al. (2004, 2007), is used to quantify and create composite governance and soundness indexes. Our composite index of bank soundness is based on 14 ratio indicators, as suggested in RBI (2010). The selected ratio indicators encompass five distinct aspects: “capital adequacy”, “asset quality”, “profitability”, “liquidity”, and “management efficiency”. It is imperative to indicate that the non-parametric index of bank soundness computed here is a more meaningful and holistic measure since it overcomes the significant inadequacies of the Z-score, the most popularly used bank soundness measure in the extant literature. Note that the Z-score is an accounting measure and captures bank insolvency risk2. It compares only bank buffers (returns & capitalisation) with risk (estimated by returns volatility). The main limitation of this measure is that it does not consider other aspects of bank soundness, such as asset quality, management performance, liquidity, or volatility to market risk (Huljak, 2015; Shaddady & Moore, 2019). The index of bank governance is based on the computational framework suggested by Gulati et al. (2020), which aggregates six dimensional indices of bank governance. These dimensions pertain to “board effectiveness”, “audit function”, “risk management”, “remuneration”, “shareholders’ rights and information”, and “disclosure and transparency”. This study considers 48 governance standards/norms defined by legislative and regulatory authorities for computing dimensional indices and the composite index of bank governance (see Sections 4.1 & 4.2 for more details). The BoD-based computational process used here for constructing the composite indices yields endogenous data-driven optimum policy weights for different dimensions of bank governance and soundness for each sampled bank. These weights explain the policy priorities and preferences of a bank and shed light on the area(s) of bank governance and soundness that needs policy interventions. In particular, the BoD approach is chosen due to its key advantages such as i) due to its non-parametric nature, it is not reliant on pre-assumptions and is appropriate for combining the unit invariant data; ii) it is also suitable for small samples; iii) the variants of the BoD approach allows the actual data (both positive & negative financial ratios) to choose endogenous weights (OECD, 2008); iv) it enables the extraction of “implicit” policy weights needed to linearly aggregate a set of dimensions from the observed data. Thus, the underlined extraction process eliminates the arbitrariness in choosing the weights required for aggregation; v) it takes a range of dimensions/indicators and assigns a single numerical score (so-called composite index) (Puyenbroeck, 2018); vi) it allows a differential weighting scheme that provides endogenous (i.e., decided by the model rather than predetermined) weights for dimensions that vary across sample units (Greco et al., 2019); and vii) the computational process is fairly intuitive and straightforward. At a final step, the study examines a connection between governance, profit efficiency and bank soundness using a two-step system generalised method of moments (GMM) approach3. An analysis of governance-soundness nexus is carried out by testing whether better compliance with any or all governance aspects predicts a bank’s soundness. The controlling effect of efficiency in impacting the connection between governance and soundness is also investigated. For this, the risk-adjusted profit efficiency scores of banks are estimated by choosing the “optimal” approach, suggested by Simper et al. (2017), for selecting an appropriate set of risk measures in a bank efficiency study. The DEA approach is used to obtain the profit efficiency scores for sampled banks. An empirical analysis is conducted using the data set for the period 2009-2018, which covers the adoption of the governance guidelines by Indian banks, as well as their revision and amendment. This study is expected to provide regulators and policymakers with a deeper understanding of interconnection between bank governance, profit efficiency and bank soundness. Further, the study results will help banks to focus on key governance and soundness issues that must be addressed urgently to avoid financial crises in the future. The study departs from existing work on corporate governance, efficiency, and soundness in several ways. First of all, the BoD model is used for the first time in this study to build non-parametric indices of corporate governance and bank soundness. Prior studies have either used unweighted averages or principal component analysis (PCA) when computing these indices (Gulati et al., 2020). However, PCA is inappropriate when sample sizes are small and variability is low (OECD, 2008). In addition, the linear average method eases the assumption that indicators are non-compensated. Thus, it is beneficial and appropriate to use the BoD approach to construct bank-level indices since it enables utilisation of unit-invariant data, applying idiosyncratic weights and aggregating multiple dimensions simultaneously to construct a composite index (Rogge & Puyenbroeck, 2007; Puyenbroeck, 2018). In light of the highlighted advantages of the BoD approach and shortfalls of its counterparts, this study constructs the bank governance and soundness indices based on a computationally less cumbersome algorithm that generates bank-specific data-driven endogenously determined weights for distinct dimensions rather than weights based on an abstract, subjective judgment. Furthermore, these weights indicate the policy priorities and preferences of sampled banks concerning underlined dimensions. Another contribution of this study lies in using data information on 14 ratio indicators and 48 equity and debt governance norms to construct bank soundness and governance indices, respectively. The corporate finance literature argues stakeholders for banking firms include not only shareholders (majority and minority), but also, comprises depositors and other creditors whose trust needs to remain intact in the bank by the managers. Therefore, the scope of corporate governance, particularly for banks, extends beyond the equity governance (shareholders) to encompass debt governance (debtholders)4. As far as we could possibly know, no previous empirical study used such a wide array of indicators to build these indices of bank soundness and governance. At long last, this is perhaps the first study that investigates a link between “governance-efficiency-soundness” in the banking industry in India. To the authors’ knowledge, there exists no study to date that attempted in this direction. In India, bank governance and soundness can be studied for two main reasons. First, dispersed ownership structures have led to several bank collapses and governance failures in developed nations, such as in the U.S. and the UK (Ard & Berg, 2010). In contrast, emerging and developing economies such as India, which have banking systems characterised by deeply concentrated financial holdings (particularly their state-owned banking segment), have experienced relatively fewer collapses and largely remained untouched by the GFC of 2007-09 (see, for example, Eichengreen and Gupta, 2013; Kumar et al., 2016; Gulati and Kumar, 2016). With this in mind, it would be worth investigating whether adhering to governance codes within a banking industry characterised by concentrated ownership guarantees soundness. The study's observations can also be applicable to countries such as Pakistan and China where the banking sector has a highly concentrated ownership structure5. Second, the tepid performance of banks, especially PSBs, in the domestic market and the significant decline in bank activities abroad due to frauds and money laundering, necessitate increased transparency and improved corporate governance. Since this study pinpoints specific areas where governance needs to be strengthened, its conclusions can be used for formulating a strategy for achieving sustainable growth in India’s banking sector. The remaining of the study proceeds as follows. In the following section, we discuss governance structures and reforms, as well as governance models across nations. A description of key governance indicators for the banking industry and across bank groups is also presented. The following section reviews the literature on bank soundness, corporate governance, and performance. We then look at indicators, ratios and dimensions of bank governance and soundness. Additionally, a discussion of governance dimensions and bank soundness is provided. We present the database, methodology, and analytical tools in the subsequent section. The penultimate section provides empirical results, and the final section discusses policy implications, limitations, and directions for future research. 2. Governance for Banks in India: Structure, Reforms and Policy Amendments 2.1 Governance Structure for Banks in India As of 1st April 2020, there are 12 public sector banks (PSBs) in which the GoI holds more than 50 per cent of the stake, 22 private banks (PBs), and 44 foreign banks (FBs). All public and private banks are listed except for three old private banks (the Catholic Syrian Bank, the Tamilnad Mercantile Bank, and the Bank of Nainital). Reserve Bank of India regulates banks under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 (amended in 2017), which gives the industry a unified regulatory environment. Interestingly, governance regulations, especially concerning board composition, are separate for banks under distinct ownership types. Note here that even though efforts were made to harmonise the regulatory structure across ownership types, yet some differences still exist. The governance and regulatory structure of Indian banks are outlined in Table 1. From the table, it is observed that the “Banking Companies (Acquisition & Transfer of Undertakings) Acts of 1970 and 1980” govern the board composition and structure of the nationalised banks, while the State Bank of India (SBI) Act of 1955 defines the set of regulations for SBI. Private banks are governed under the Companies Act of 1956 (amended in 2009 & 2013), which is broadly based on entity laws. On contrasting governance structure across public and private bank groups, it is observed that in private banks, the board of directors play a supervisory role and appoints managers to run the bank. While in PSBs, the GoI, in consultation with RBI through the Appointments Committee of the Cabinet, decides the appointment of the board of directors except for shareholders appointees. The key agency concern that emerges because of this arrangement is that there exists a dual regulation system for PSBs, in which the Ministry of Finance of the GoI and RBI define the legal and regulatory frameworks for these banks. The presence of the dual regulation system debilitates the regulatory discipline leading to feeble corporate governance in PSBs. Further, ownership concentration and control with the government, especially of PSBs, raise the agency conflict of type II, which may have troubled the banks in the smooth implementation of all layers, and limited their ability to compete with their private counterparts (RBI, 2001). In addition, the ownership concentration varies significantly across PSBs. Interestingly, the proportion of government-owned equity shares in Indian state-owned banks is quite high that varies from a minimum of 63 per cent in the Bank of Baroda to a maximum of 93 per cent in the UCO Bank as of 1st April 2020.