IST,

IST,

Report of the Working Group on Pricing of Credit

The report of the Working Group on Pricing of Credit has been possible with the support and contributions of many individuals and organisations. The Working Group would like to gratefully acknowledge this support. The Working Group thanks Dr Subir V Gokarn, ex-Deputy Governor and Shri Deepak Mohanty, Executive Director for insights on Monetary Policy transmission. The Working Group thanks Shri Deepak Singhal, present Regional Director of New Delhi office of Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the former member secretary of the Working Group along with Shri P Ravi Mohan, presently Regional Director of Bhopal office of RBI who had initiated the discussions in the first meeting of the Working Group, in their earlier role as senior officials of DBOD. The Working Group was supported by inputs received from some of the officers of Reserve Bank. Mention needs to be made of Shri A K Mitra, Director in Monetary Policy Department for monetary policy related research and inputs. The Department of Banking Operations & Development (DBOD) of the RBI provided continuous support to the Working Group, with valuable contributions from Ms Reena Banerjee, General Manager, on international best practices on consumer protection and Shri Puneet Pancholy, Deputy General Manager who researched the international papers on pricing models/ approaches as also for his support during finalization of this Report. Ms J Sujatha and Ms J Sailaja Rani, Assistant General Managers, did diligent research on several issues. Many of the members had dedicated teams working for them in their respective organizations and the Working Group would like to thank them as well for the quality of their inputs. The Working Group gratefully acknowledges the support and contributions made by the Working Group’s Secretariat comprising Shri Vivek Deep and Shri Vivek Srivastava, General Managers, as also, Shri Sanjeev Dayal, Ms Latha Vishwanath and Ms Surekha Mund, Deputy General Managers, DBOD not only for coordinating the efforts of the Working Group but also for providing critical data and inputs during its deliberations. The Working Group also thanks Shri R R Nerurkar, Assistant General Manager, DBOD for providing logistics support and in facilitating the smooth conduct of meetings. Executive Summary and Recommendations 0.1 In the dynamic world of finance the demand for credit is one of the constants. In India, banks are the most important channel to meet this demand. Banks connect the surplus and deficit economic agents through their primary activity of financial intermediation, and generate profits largely from the difference between the interest paid to the depositor and charged to the borrowers. 0.2 At the time of lending funds, banks are expected to carry out necessary credit appraisal and due diligence and thereafter, charge interest accordingly. The interest rates charged to borrowers can be determined by banks based on fixed rules or discretion. Under rules based lending, banks may use models to arrive at the interest rate that may be charged to the customers. A number of research papers have endeavoured to model the factors that determine the lending rates by banks. While rule based lending leads to interest rates that are based on pre-defined factors, lending based on discretion allows flexibility to banks in terms of considering customer specific attributes as well. Notwithstanding the method followed, it is in the interest of all stakeholders that pricing is kept efficient and fair. 0.3 Efficient and fair pricing of credit by banks, within the ambit of policy of the Central Bank, is assumed to be serving the following three objectives:

0.4 In India, interest rate regulation has traversed a long path from the days of administered regime in vogue till the early 1990s to the deregulated regime prevailing now. As part of the deregulation, banks have been permitted to set their own lending and deposit rates except for a very few segments such as DRI scheme where administered rates still prevail. To ensure that such flexibility is judiciously deployed and the borrower interests are taken care of, the BPLR system was replaced by the Base Rate system in 2010 which has largely addressed the gaps noticed in the erstwhile BPLR regime. 0.5 Despite the policy efforts to usher in transparency and fairness to the credit pricing framework, there have been certain concerns from the customer service perspective. These mainly relate to the downward stickiness of the interest rates, discriminatory treatment of old borrowers vis-à-vis new borrowers, and arbitrary changes in spreads, etc. In response, the Reserve Bank of India had announced in the Second Quarter Review of October 2011 that a Working Group will be constituted to examine the issues related to discrimination in pricing of credit and recommend measures for transparent and appropriate pricing of credit under a floating rate regime. Accordingly, a Group was constituted under the Chairmanship of Shri Anand Sinha, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India comprising members from banks, IBA, Academia and the Reserve Bank of India, with the following terms of reference:

0.6 A study of available literature provided useful insight on the models/approaches that are used for pricing of loans. It emerged that banks use both rules and discretion based pricing strategies, or even a hybrid strategy containing elements of discretion in a rule based approach. Pricing depends on various factors like the type of model used, availability of information, competition, size of the loan, and switching cost, etc. The papers also provided information on factors that may have a bearing on pricing of the spread of a floating rate loan such as concentration of banks, ownership, collateral, etc. It also became evident that there is no one uniform or best way for pricing of credit and that the pricing by banks is often dependent on the strategy pursued. 0.7 Typically, the pricing of credit is done on a cost plus approach, i.e., a benchmark rate plus a spread. The benchmark used for the purpose can be inter-bank market rate or the overnight money market rates or a cost of funds index. The spread comprises various factors that include product specific operating cost, credit risk premium, tenor premium, competition, strategy and customer relationship, etc. While the lending rate remains fixed in the case of a fixed rate loan, in the case of floating rate loans, the lending rate is dynamically reset at specified intervals based on the movements in the benchmark rates. 0.8 Ideally for floating rate loans, the interest rate charged to a customer should not change at the time of reset unless (a) there is a change in Base Rate or (b) there is a change in credit profile of the customer thereby leading to change in credit spread charged. Further, in case there is a change in policy rate by the central bank, it should impact the benchmark, albeit with a lag, and not the spread component of the interest rate. 0.9 Banks with lower cost of funds aided by higher CASA may not necessarily increase the lending rates when the policy rate is increased as long as their margin expectations are fulfilled. These banks can leverage this advantage to maximise their respective market shares. On the other hand, such banks can reduce the Base Rate as soon as the policy rate is moderated (as they already enjoy lower cost of funds) to maximize their market share before waiting for the full impact of reduction in policy rate to be fully felt on their cost of funds. 0.10 In the Indian markets, movement of Base Rates of banks vis-à-vis the policy rate has been asymmetric. While the increase in policy rate led to a corresponding increase in the Base Rate of banks, the Base Rate has exhibited “stickiness” by not coming down quickly enough whenever there has been a reduction in the policy rate. 0.11 The stickiness in Base Rate can be attributed to the deposit profile of banks. Banks with considerable reliance on interest bearing deposits, which are fixed in nature, do not have the flexibility to pass on the impact of accommodative policy action immediately as their cost of funds represented by the cost of fixed deposits does not decrease immediately. By and large, banks in India are computing their Base Rate based on the weighted average cost of deposits, and hence, their Base Rate does not lend itself to immediate downward adjustment. The full impact can be seen only after the bulk of the existing fixed rate deposits gets rolled over at lower rates on maturity. 0.12 The liquidity conditions in the market may also impact the behaviour of the Base Rate. At times of tight liquidity in the market, the inter-bank call rates are generally above the policy rate. Any easing of the policy rate may not impact the Base Rate in such a scenario. However, under the same scenario, significant injection of liquidity say through a cut in the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) will infuse substantial liquidity in the system that may lead to the lowering of the interest rates. Further, the interest rates can also be influenced due to the predominance of the public sector banks. 0.13 In India, the deposit profile is predominantly fixed rate, while the loans, especially the home loans, are predominantly under floating rate regime. Hence, the effects of stickiness in the Base Rate of banks can be mitigated if the loans and advances are funded by similar liability, i.e., longer term floating rate deposits, thereby making assets and liabilities symmetrical to sensitivity in policy rate. The WG noted that though the regulations do not impede floating rate deposits, these are virtually non-existent as the depositors have the implicit option of replacing a low yielding deposit with a higher yielding one. 0.14 As the Base Rate is computed primarily using the average cost of funds, it does not move in tandem with the policy rate. One of the ways to make the Base Rate more responsive to the policy rate is by banks computing their Base Rates on the basis of the marginal cost of funds. Under this approach, the pricing of other facilities based on Base Rate will more quickly align with the changes in the policy rate. The WG deliberated at length the appropriateness and feasibility of the use of marginal cost of funds by banks in computing their Base Rate. However, taking into account the difficulties involved in migrating to marginal cost of funds for computing Base Rate for majority of banks due to the maturity profile of deposits, it may not be appropriate to mandate it at this juncture. 0.15 Where banks choose to use the historical cost of funds for computing the base rate, it would be unrealistic to expect that they would not pass on the benefit of lower marginal cost of funds to the new customers by operating on the spreads.This can lead to differentiation amongst customers who enter into borrowal relationship with a bank at different points of time. However, the WG wishes to emphasise that no bank can discriminate among borrowers who get into borrowing relationship with a bank at the same time, i.e., in identical or similar funding conditions. Any difference in pricing in such cases must be based on objective and transparent criteria for determining the mark up or spread over the base rate. It is important to be clear about what these criteria might be. In other words, on what grounds does a bank distinguish between customers who enter into a relationship with it at the same time and also have the same credit risk profile? The WG has sought to address this question. 0.16 At the time of pricing of floating rate loans, banks add a spread to the benchmark rate to arrive at the interest rate charged to the borrower. In terms of the guidelines on Base Rate, the spread should be a function of product specific operating cost, credit risk premium and the tenor premium. This apart, there are other behavioural factors such as competition, customer relationship and business strategy that also get factored in while determining the lending rates. In any formulation on this issue, these factors need to be considered. Banks have contended that parameters such as future business potential of a customer, value of the relationship and business strategy are some ‘soft’ parameters which are difficult to quantitatively establish but surely form a part of their pricing. However, arbitrary inclusion of these factors into pricing can lead to discrimination among customers. 0.17 The WG agreed that while price differentiation among old and new customers would remain where the Base Rate is calculated on the basis of weighted average cost of deposits, price discrimination cannot be accepted. Price differentiation will imply different pricing for customers with identical credit profile due to varying conditions. One reason for difference in pricing that has been highlighted earlier is that customers may establish borrowing relationships at different point of time when the marginal cost of funding has declined due to lowering of policy rate (while the base rate remains unaffected because it is computed using historical cost of funds). To this, other factors need to be added that could result in differences in pricing between customers with identical risk profiles. Illustratively, a bank may pursue a business strategy whereby it wishes to acquire a greater share of a product market or wants to enter into a new segment where there are established players by making loans to new customers at a lower rate. Value of relationship would be another factor resulting in concession in the interest rates when bank expects to gain fee-based business or deposit accounts or more business in future. On the other hand, price discrimination would occur if a bank offers different prices on loans to two customers with identical credit profile and without any of the other factors mentioned above entering the picture. Such price discrimination cannot be accepted. 0.18 The Board of banks must ensure through a laid down policy that customers are not discriminated against and the differentiation in pricing of credit is occurring only due to specified factors such as competitive conditions, customer relationship and business strategy. In order to ensure that these factors are not used arbitrarily, the Boards of banks must ensure that the interest rates charged to customers are consistent with bank’s target for Risk Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC). Recommendation 1 The WG recommends that it would be desirable that banks, particularly those whose weighted average maturity of deposits is on the lower side, move towards computing the Base Rate on the basis of marginal cost of funds as this may result in more transparency in pricing, reduced customer complaints, better transmission of changes in the policy rate and improved asset liability management at banks. If banks are using weighted average cost of funds because of their deposits profile or any other methodology that may result in differentiation between old and new customers, the Boards of banks should ensure that this differentiation does not lead to any discrimination amongst borrowers. Discrimination would occur if a bank offers different prices on loans to customers with identical credit profile, every other factor being the same. Recommendation 2 The WG acknowledges that apart from factors like specific operating cost, credit risk premium and tenor premium, broad factors like competition, business strategy and customer relationship are also used to determine the spread. Banks should have a Board approved policy delineating these components. The Board of a bank should ensure that any price differentiation is consistent with bank’s credit pricing policy factoring RAROC. Banks should be able to demonstrate to the Reserve Bank of India the rationale of the pricing policy. 0.19 The WG observed that competition, customer relationship and business strategy are very broad factors that encompass a number of components and that it would not be practical to prepare an exhaustive list of factors that may be clubbed under business strategy and customer relationship. Further, it is possible in this framework for a bank to arbitrarily bring in some factor as strategy or competition to price the spread, and this could put some customers at a disadvantage. Moreover, each bank may use a different combination of such factors to price the spread for relationship, strategy or competition. The WG, therefore, felt that the Board of a bank would be in the best position to assess the optimal bouquet of such factors that it determines should be clubbed under these parameters to price the spread. Recommendation 3 The WG recommends that banks’ internal policy must spell out the rationale for, and range of, the spread in the case of a given borrower, as also, the delegation of powers in respect of loan pricing. 0.20 Arbitrary change in contracted spread has also resulted in complaints by the customers. It is understood that likely reasons for change in contracted spread is to adjust the impact of changes in policy rate, or any other factor like liquidity in the system, etc. The WG felt that for a given customer, once a spread has been determined after looking at all factors including customer’s credit profile, customer relationship with bank, strategy, etc., such spread should not be increased except on account of deterioration in the credit risk profile of the customer. There should be a loan covenant to this effect. Apart from this, the WG felt that other externalities should not impact the contracted spread for a given customer. Recommendation 4 The WG recommends that the spread charged to an existing customer cannot be increased except on account of deterioration in the credit risk profile of the customer. The customer should be informed of this at the time of contract. Further, this information should be adequately displayed by banks through notices/website. 0.21 The WG observed that any change in Base Rate need not result in an immediate change in the floating interest rate on the existing loans. The covenant of the floating rate loan may have mandatory reset dates (monthly, quarterly, half-yearly, etc.) and the existing loans may be reset on the date agreed upon in the covenant. This will improve transparency with respect to the customer, who would know upfront when the rates are due for change. It will also aid in better risk management by banks. Recommendation 5 The WG recommends that the floating rate loan covenant may have interest rate reset periodicity and the resets may be done on those dates only, irrespective of changes made to the Base Rate within the reset period. One member, State Bank of India, however is of the view that whenever there is a change in the Base Rate, such changes should be passed on to the customers. 0.22 Though the Base Rate system has replaced the BPLR system with effect from July 1, 2010, and is applicable for all new loans and for those old loans that come up for renewal, some of the existing loans based on the BPLR system continue to be in the system and may run till their maturity. Continuation of contracts under the BPLR regime leaves an element of operational inconvenience for banks. Moreover, the intended benefit of the Base Rate regime, viz., shifting of the old BPLR linked borrowers to the base rate system could not manifest itself in the true sense. Apparently, customers who shifted from BPLR to the Base Rate regime were charged a spread different / higher than the borrowers who entered newly / directly under the Base Rate system leading to issues of discrimination between old and new customers. Recommendation 6 The WG recommends that there may be a sunset clause for BPLR contracts so that all the contracts thereafter are linked to the Base Rate. Banks may ensure that these customers who shift from BPLR linked loans to Base Rate loans are not charged any additional interest rate or any processing fee for such switch-over. 0.23 Apart from the Base Rate, Indian banks have been allowed to use external benchmarks to facilitate pricing of floating rate interest rates. A number of external benchmarks are available in the Indian markets, viz., MIBOR, G-Sec yields, Repo Rate, CP and CD rates, etc. However, these benchmarks have drawbacks - they are mainly driven by liquidity conditions in the market, as also, they do not reflect the cost of funds of banks. Further, these benchmarks are volatile and may lead to frequent changes in the floating rate. 0.24 A number of countries have benchmark indices over which the floating interest rates are priced. The WG considered benchmarks available in various countries that are being used for pricing of floating rate loans. The major advantage of using such benchmarks is that it makes comparison between similar loan products offered by competing banks easier and more efficient. 0.25 To improve transparency in the pricing of floating rate loans, the WG proposes a new benchmark, viz., Indian Banks Base Rate (IBBR) Index which is a Benchmark derived from the Base Rates of some large banks. The use of IBBR would facilitate all floating rate loan pricing to move in tandem and an individual bank’s specific funding advantages /disadvantages and changes in funding profile may not affect the customers. Further, as the IBBR will be based on major banks across the system, changes in base rate of few banks will have limited impact on the index. Being an industry-wide index, it is likely to find better acceptance than market benchmarks like MIBOR, T-bill, etc. By design, the IBBR should meet the standards for benchmarks set by the Committee on Financial Benchmarks (Chairman: Shri P Vijaya Bhaskar, Executive Director, RBI)1. These standards include, inter-alia, well-defined hierarchy of data inputs, code of conduct for submitters, minimum number of submitters, and a well-defined methodology for calculation of the benchmark. Moreover, there should be a governance structure in place for benchmark administrators, benchmark calculation agents and benchmark submitters. Recommendation 7 The WG recommends that IBA may develop a new benchmark for floating interest rate products, viz., the Indian Banks Base Rate (IBBR), which may be collated and published by IBA on a periodic basis. Banks may consider offering floating rate products linked to the Base Rate, IBBR or any other floating rate benchmark ensuring that at the time of sanction, the lending rates should be equal to or above the Base Rate of bank. To begin with, IBBR may be used for home loans. By design, the IBBR should meet the standards for benchmarks set by the Committee on Financial Benchmarks (Chairman: Shri P Vijaya Bhaskar, Executive Director, RBI). 0.26 Apart from the issues underlying pricing of credit, the WG studied international standards and regulations on consumer protection. Many international bodies and regulators have focused attention on consumer protection and conducted studies and surveys as well as published reports and issued guidance. It is observed that consumer protection measures in various jurisdictions broadly focus on disclosure and transparency, regulations for equality and against unfair trade practices. Protection in this regard is enforced either through Laws/Statutes/Acts or stipulations by regulators. In addition, industry associations have also developed self-regulatory codes of practices. In India, banks are guided on consumer credit protection and customer service by instructions/ regulations/directions from the RBI and guidance from BSCBI, apart from protection under the Customer Protection Act 1986. 0.27 The Consumer Protection Act, 1986 which provides the statutory framework for consumer protection, also covers the banking services and provides a dispute resolution framework. However, there is anecdotal evidence that in this framework, the entire process may be time consuming. 0.28 The directives, guidelines and advisories issued by the Reserve Bank of India enumerate the regulatory measures regarding consumer protection / customer service. They cover individual products / services as also the grievances redressal mechanism that each bank is mandated to put in place. 0.29 Banks have also adopted fair practices code / lenders liability code and codes of the Banking Codes and Standards Board of India (BCSBI) which are in the nature of self-regulatory measures which each bank is expected to adopt with the approval of the Board of Directors and place in the public domain. 0.30 With respect to grievance redressal, the Banking Ombudsman Scheme (2006) of the RBI serves as an alternate dispute resolution mechanism for deficiencies in banking services that have been clearly delineated. This is a cost free service aimed at helping the common person / small enterprises who may have limited means to approach a court of law or a consumer court for resolution of their grievances. 0.31 Thus it may be seen that for handling disputes, institutional and structural arrangements are in place. However, the WG felt that the grievances redressal systems in banks should be made robust and responsive to customers’ needs. 0.32 In the area of consumer protection, the WG has following recommendations to make: Recommendation 8 The WG reiterates that banks should publish their interest rates, fees and charges on their websites for transparency, comparability across banks and informed decision making by customers. In addition, it is recommended that the banks should disclose the interest rate range of contracted loans for the past quarter for different categories of loans along with the mean and median interest rates charged.

Recommendation 9 The WG recommends that banks may provide a range of Annual Percentage Rate (APR) or such similar other arrangement of representing the total cost of credit on a loan on annualized basis that will allow customers to compare the costs associated with borrowing across products and / or lenders. However, the applicable APR should get crystallized in the loan covenant with the customer. Recommendation 10 The WG recommends that the terminology used by all banks must be standardized so as to enhance/ facilitate comparability. A glossary/ list of terms standardised for all banks and for all bank accounts offered to customers may be drawn up and mandatorily be included at the end of the loan offer documents and sanction letters. These may be displayed on the websites of banks. The initiative for creating a standardised terminology may be taken by IBA. Recommendation 11 (i) The WG recommends that the Reserve Bank may clearly specify the information to be included in credit agreements, including a standard format for a summary box to be displayed on the credit agreement. Besides banks may be mandated to provide a clear, concise, one-page key facts statement/fact sheet to all retail/mortgage borrowers at every stage of the loan processing as well as in case of change in any terms and conditions. This would give customers a simple summary of the important terms and conditions (tenor / fees/ interest rate / reset dates) of the financial contract. (ii) The WG also recommends that a standardized loan format may be prepared by IBA for retail customers covering terms and conditions including inter-alia the periodicity of reset and provisions for re-fixation of spread in an unambiguous and simplified language Recommendation 12 The WG recommends that the benefit of interest reduction on the principal on account of pre-payments should be given on the day the money is received by bank without waiting for the next EMI cycle date to effect the credit. Recommendation 13 The WG recommends that both banks and the RBI may impart Financial Education through consumer education drives. Recommendation 14 (i) The WG recommends that for the retail loans, the customers should have a choice of “with exit” and “sans exit” options at the time of entering the contract. The exit option can be priced differentially but reasonably. The exit option should be easily exercisable by the customer with minimum notice period and without impediments. This would address issues of borrowers being locked into contracts, serve as a consumer protection measure and also help enhance competition. (ii) The WG also recommends that IBA should evolve a set of guidelines for easier and quicker transfer of loans, particularly mortgage/housing loans. There could also be penalties for banks which do not cooperate with borrowers in this regard. Recommendation 15 The WG recommends that the industry association, IBA, should do the following:

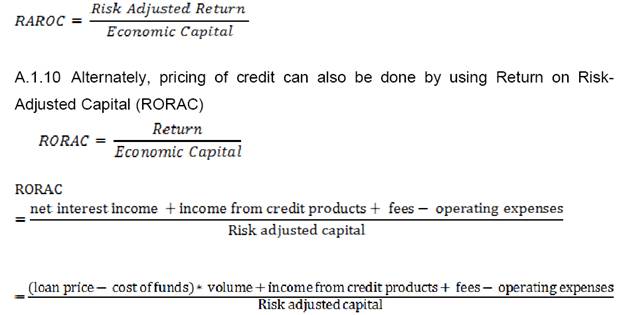

Recommendation 16 The WG reiterates that the grievances redressal systems in banks should be made robust and responsive to customers’ needs. The senior management of banks should pay particular attention in this regard. Banks which do not put in place adequate measures, as evidenced by repeated complaints, may be penalized by the RBI. 1.1 The price of credit, as reflected in lending rates, plays a significant role in encouraging economic activity. As per economic theory, lower interest rates spur economic activity and propel growth while higher interest rates help to contain exuberance and moderate credit and, eventually, economic growth. Policy makers, therefore, attach a lot of importance to the interest rate channel of transmission of monetary policy and endeavour to improve the effectiveness of such transmission. 1.2 Fair pricing of credit is very critical for both lenders as well as borrowers. In fact it has a direct bearing on earnings and profits of a lending bank. Pricing of credit should be done in such a way so as to generate adequate return (return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA)) for banks, as also, ensuring optimal Risk Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC). The effectiveness of loan pricing ultimately impinges the prudential aspects of bank in terms of capital adequacy, asset quality, management, and earnings, etc. 1.3 According to Stiglitz and Weiss (1981)2, in a world with perfect and costless information, a bank would stipulate precisely all actions which a borrower could undertake (which might affect the return to the loan). However, bank is not able to directly control all actions of the borrower; therefore it will formulate the terms of the loan contract in a manner designed to induce the borrower to take actions which are in the interest of bank as well as to attract low risk borrowers. 1.4 Efficient and fair pricing of credit could be assumed to be serving the following three objectives:

1.5 Interest rate regulation in India has traversed a long path (as explained in Chapter 3) from the days of the administered regime till the early 1990s to the deregulated regime prevailing now. Banks have been permitted to set their own lending and deposit rates excepting a few segments such as DRI scheme where administered rates still prevail. To ensure, however, that such flexibility is judiciously deployed and borrower interests are taken care of, certain guidelines have been prescribed from time to time. The Prime Lending Rate (PLR) system gave way to the Benchmark Prime Lending Rate (BPLR) system which is recently replaced by the Base Rate system. 1.6 The Base Rate system was expected to bring in more transparency and consistency to the interest rate framework and also enhance the effectiveness of the monetary policy. While it is too early to assess its success in enhancing the effectiveness of the monetary policy, the Base Rate regime seems to have addressed the gaps noticed in the erstwhile regime of BPLR. 1.7 There have however been some concerns from the customer service perspective which needed a review of the pricing of credit by banks. Customer complaints essentially arose on the following:

1.8 There have also been other complaints regarding administrative issues such as delay in sanctions, non-communication of the decision of non-sanction, inadequate dissemination of information to the borrowers, and lack of standardized procedures, etc. 1.9 Reserve Bank announced in the Second Quarter Review of Monetary Policy in October 2011 that a Working Group will be constituted to examine the issues related to discrimination in pricing of credit and recommend measures for transparent and appropriate pricing of credit under a floating rate regime. Accordingly, a Group was constituted under the Chairmanship of Shri Anand Sinha, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India comprising members from banks, IBA, Academia and the Reserve Bank of India. The constitution of the Group is as follows:

1.10 The terms of reference to the Group are as under:

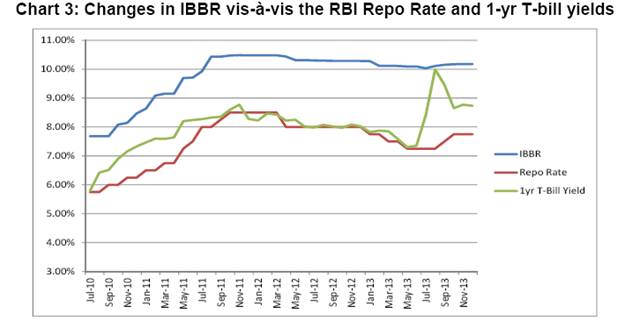

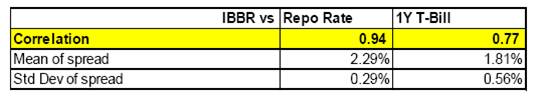

CHAPTER 2 2.1 Banks are the most important entities in the financial system and contribute significantly to the economic development of a country. Through their primary activity of financial intermediation, they connect the surplus and deficit economic agents. Banking business primarily pivots around accepting deposits and lending funds, thereby profiting from the difference between the interest paid to the depositors and charged to the borrowers. For a bank to make profit, this difference should be positive. 2.2 The principle of demand and supply applies to the pricing of credit by banks. The interest rate that is charged by a bank depends on the extent of demand from borrowers as also, on the lendable funds available with a bank. 2.3 Though it may appear to be simple, the dynamics of managing asset and liability by a bank are quite tedious. The liabilities or the source of funds for a bank can be manifold. Apart from deposits which form the largest source of funds for banks, they also rely on the money, capital and foreign exchange markets to source funds for lending. However, it is the CASA or Current Account-Savings Account deposits that form the bulk of as well as the cheapest source of funds for banks. 2.4 On the other hand, banks lend funds to borrowers after carrying out necessary credit appraisal and due diligence and thereafter, charge them interest accordingly. The interest rate charged to the borrowers can be determined by banks based on fixed rules or discretion. Under rules based lending, banks may use models to arrive at the interest rate that may be charged to the customers. A number of research papers have endeavoured to model the factors that may determine the lending rates. Some of these studies have been annexed at Annex I. 2.5 While rule based lending leads to interest rates that are based on pre-defined factors, lending based on discretion allows flexibility to banks in terms of considering customer specific attributes also. These factors may include the size of loan, size of company, predictive power of model, riskiness of firm, and switching cost for a firm, etc. 2.6 Discretion based lending can result in subjective decision making and may lead to discrimination amongst customers in pricing of loans. Banks may also adopt a hybrid strategy by adding an overlay of discretion to the outputs generated by the credit pricing models. At any point in time, there is always a trade-off between rule based lending as against discretion based lending. There have been some studies that have identified situations where discretion based lending may be practiced. 2.7 Depending upon the size of loan, relationship, competition, etc., a bank may decide whether a loan needs to be priced on the basis of rules using statistical models (Cerqueiro, Degryse and Ongena, 2007)3. Transactions lending (or rule based lending) is based on quantitative data whereas relationship lending (or discretion based lending) is based on qualitative information. 2.7.1 Banks may use rule based lending where their loan-pricing models have higher predictive powers. Else, they may be constrained to use discretion. 2.7.2 Discretionary lending practices may also stem from market imperfections, such as information asymmetry, imperfectly competitive credit market structures, regulatory constraints, etc. These market imperfections allow unfair advantage to banks over borrowers. 2.7.3 Larger firms with better information have a comparative advantage in rule based lending, while smaller institutions have a comparative advantage in discretion based lending. Size of a loan is dependent on the size of business and has an immediate bearing on the pricing of the loan. It is generally accepted that smaller loans attract higher interest rates (Benston, 1964)4. The inverse relationship between interest rates and the size of loans may be construed as a discrimination against small loans and hence, against smaller businesses. This may be due to the fact that in most cases, demand curves of loans for small businesses are likely to be inelastic as compared to large businesses that have multiple options to raise funds. 2.7.4 Further, it has been observed that switching costs are proportional to the size of the firm. Larger firms are likely to be well audited, have copious public information and multiple creditors, and hence are likely to have lower switching costs. Borrowers with low switching costs face rule based prices, while those with high switching costs face discretion in pricing (Bester, 1993)5. 2.7.5 Higher the risk in the firm, and greater the opaqueness, there would be more “discretion” in loan pricing. 2.7.6 Stronger ties of a bank with a firm imply less uncertainty for a lender, and hence less “discretion”. This correlation stems from the informational advantage a lending bank may have over its competitors. 2.8 Interest rate on a floating rate loan has two components – a benchmark rate and a spread. Benchmark 2.9 For pricing of a loan, a benchmark or a perfectly competitive rate is required, against which deposit and loan rates can be compared. Globally, the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) has been the rate banks quoted to each other for overnight deposits and loans. Being an international rate to which all banks have access, LIBOR used to be treated as a proxy for the perfectly competitive loan rate, though the recent turn of events have undermined its popularity. 2.10 A floating interest rate is expected to move synchronously with the benchmark rate on which it has been priced. However, Heffernan (2006)6 has shown that there is likely to be a lag in price adjustment to changes in LIBOR. Even the deposit and loans rates are unlikely to respond to changes in LIBOR immediately. 2.11 Globally, the pricing of loans is done on a cost plus approach, i.e., a benchmark rate plus a spread. The benchmark used for the purpose can be the interbank market rate (Brazil, Poland and South Africa) or the overnight money markets rates. In US, it can be based on US prime rate, which is broadly determined as a 300 bps spread over the Fed Funds rate or any other benchmark such as the Cost of Funds Index or the Wall Street journal (WSJ) prime rate. The PLRs in these countries tended to have moderate to high correlation with central bank policy rate. A list of various benchmarks used globally is annexed at Annex II. Spread 2.12 Under the cost plus approach, interest rates are determined by adding a spread over the benchmark rate. The spread comprises product specific operating cost, credit risk premium, tenor premium, etc. Several research papers are available in the public domain that have endeavoured to identify the components that have a bearing on the spread as also, to develop a model for pricing the spread. 2.13 According to standard economic theory, presence of a dominant bank or financial institution may lead to higher costs for the customers which may get accentuated in the absence of perfect competition. This in turn may also lead to reduced access of borrowers to loans. If the dynamics of informational asymmetries and agency costs are considered, there is a possibility of adverse selection, thereby benefitting a borrower in terms of easy (and cheaper) access to loans. 2.14 Petersen and Rajan (1995)7 show that “…banks with market power have more incentives to establish long-term relationships with young borrowers, since they can share in future surpluses”. Further, “…small firms are more likely to receive financing at a lower cost in more concentrated local banking markets in the U.S”. 2.15 Cetorelli and Peretto (2000)8 show that though the aggregate amount of loanable funds may get reduced due to concentration of banks, lending may get efficient due to better screening of the borrowers as banks have advantage of better availability of information. Therefore an oligopolistic market may be an optimal banking market structure if compared with monopolistic market or a perfect competition market, offering better prices to the customers. However, Hannan (1991) has shown that that there is a great association between concentration and higher interest rates in the US banking markets. 2.16 Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic (2003)9 have shown that restricting banks’ activities might increase competition in an area. They also worked on the ownership structure of banks and have indicated that ownership structure influences access to and costs of external financing. Government owned banks may be mandated to lend to certain sector or a set of borrowers as such banks do not intend to maximize their profits. As compared to foreign banks, domestically owned banks may be more willing to do business with ‘opaque borrowers’ as they have superior information gathering system and better enforcement mechanisms. Hence, the ownership structure also has a say in access to loans and can influence the cost of loan. 2.17 In a research paper by Sumon C. Mazumdar and Partha Sengupta10, the spread is shown as a function of a number of factors including the size of a loan, its maturity, and collateral, etc. 2.18 In another research paper by Maria Soledad, Martinez Peria and Ashoka Mody11 on Latin American countries, spreads were studied vis-à-vis foreign participation and market concentration. According to the study, foreign banks charge lower spreads, possibly due to lower cost of operations. New establishments or de novo banks operate with particularly low spreads. The authors feel that the possible reason for cost reduction may be a manifestation of demonstration effect and potential competition where banks may be targeting the competing banks’ customers, thereby benefiting bank clients. In the case of domestic banks, greater concentration raises spreads, as higher concentration may increase administrative costs. 2.19 Study of various research papers provided useful insight into the models that are used for pricing of loans. Further, it emerged that banks use both rules and discretion based pricing strategies, or even a hybrid strategy containing elements of discretion in a rule based approach. Pricing depends on various factors like the type of model used, availability of information, competition, size of the loan, and switching cost, etc. Further, the papers also provided information on factors that may have a bearing on pricing of the spread of a floating rate loan such as concentration of banks, ownership, collateral, etc. However it is evident that there is no one uniform or best way for pricing of credit and that the pricing by banks is dependent on the strategy pursued. CHAPTER 3 3.1 Pricing of credit is regulated by the RBI in terms of the powers vested with it under Section 21 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 which deals with the power to control advances made by banking companies. Prior to financial sector reforms of the 1990s, the regulation of pricing of credit was by way of prescription of sector-specific quantum and tenor based interest rates. The exact modalities for arriving at the amount of loan that can be granted were also indicated during the administered interest rate regime, regulated by the Reserve Bank of India till the late 1980s. 3.2 In October 1994, as a major step towards deregulation of lending rates, banks were permitted to determine their own lending rates for credit limits over `2 lakhs. The rates were to be determined with reference to a Board approved benchmark. The benchmark was the Prime Lending Rate (PLR) of a bank. The PLR was the minimum rate charged by banks for credit limit of over `2 lakhs. 3.3 In February 1997, banks were allowed to charge interest rate on loan and cash credit components separately, based on PLRs and spreads (over PLRs), as approved by their Boards. 3.4 Further, to distinguish between the tenor of loans, a separate Prime Term Lending Rate (PTLR) was introduced in October 1997 for term loans of three years and above and PLR was used for granting short-term loans. In April 1998, to ensure that the small borrowers are not charged at the same rate, PLR was prescribed as a ceiling rate on loans below `2 lakh. 3.5 In April 1999, the concept of Tenor Linked Prime Lending Rate (TPLR) was prescribed to operate as different PLRs for different maturities. Banks were also given the additional freedom to charge certain categories of loans without reference to the PLR in October 1999 and in 2000-01, banks were permitted to charge fixed/ floating rates on all loans with credit limit of more than `2 lakh with PLR as the reference rate. 3.6 The Mid-Term Review of the Monetary and Credit Policy for the year 2002-03 observed that both PLR and spread varied widely across banks/bank-groups. Since in a competitive market, PLRs among various banks/bank-groups should converge to reflect credit market conditions and the spreads around the PLR should be reasonable, banks were asked to review both their PLRs and spreads and to align spreads within reasonable limits around PLRs. However, the divergence in PLR and the widening of spreads between bank borrowers continued to persist. Moreover, the prime lending rates continued to remain rigid and inflexible in relation to the overall direction of interest rates in the economy. 3.7 In order to enhance the transparency in banks' pricing of their loan products as also to ensure that the PLR truly reflects the actual costs, banks were advised to price their advances with reference to a new benchmark- Benchmark PLR (BPLR). The BPLR was determined by taking into account the (i) actual cost of funds, (ii) operating expenses and (iii) a minimum margin to cover regulatory requirement of provisioning / capital charge and profit margin. 3.8 Since all lending rates could be determined with reference to the BPLR by taking into account term premia and / or risk premia, the system of tenor-linked PLR was discontinued. These premia could be factored in the spread over or below the BPLR. 3.9 The above prescriptions led to a situation whereby banks could lend below BPLR. By December 2009, sub-BPLR lending was about 65.8 per cent of aggregate lending. There were several complaints from borrowers regarding levying of excessive interest on certain loans and advances like credit card dues. The benchmark prime lending rate (BPLR) system had, thus, fallen short of expectations in its original intent of enhancing transparency in lending rates charged by banks. 3.10 More importantly, the BPLR tended to be out of sync with market conditions and did not adequately respond to changes in monetary policy. On account of competitive pressures, banks were lending a part of their portfolio at rates which did not make much commercial sense. This tendency to extend loans at sub-BPLR rates on a large scale in the market continued to raise concerns on transparency and cross-subsidisation in lending (large borrowers cross subsidized by retail and small borrowers). 3.11 To address the drawbacks in the BPLR system, the Base Rate system was introduced on July 1, 2010 to make the lending rates transparent, forward looking and sensitive to the Reserve Bank’s policy rate. Since the system of pricing under the Base Rate will invariably be at a rate which is ‘cost plus’, it would make more commercial sense. The Base Rate system is considered more transparent since the borrower knows that there cannot be any sub-Base Rate lending except for the exempted categories and any change in the Base Rate will equally affect all the borrowers with floating rate. 3.12 Base Rate shall include all those elements of the lending rates that are common across all categories of borrowers. Banks may choose any benchmark to arrive at the Base Rate for a specific tenor that may be disclosed transparently. One of the ways this can be done is that the base rate may comprise a bank’s cost of deposits / funds, negative carry on CRR and SLR, unallocatable overhead cost and average return on net worth. However, banks are free to use any other methodology, as considered appropriate, provided it is consistent, and is made available for supervisory review/scrutiny, as and when required. 3.13 Banks may determine their actual lending rates on loans and advances with reference to the Base Rate and by including such other customer specific charges as considered appropriate. The actual lending rates charged should be transparent and consistent and be made available for supervisory review/scrutiny, as and when required. 3.14 Changes in the Base Rate shall be applicable in respect of all existing loans linked to the Base Rate, in a transparent and non-discriminatory manner. 3.15 The methodology of computing the floating rates should be objective, transparent and mutually acceptable to counter parties. The Base Rate could also serve as the reference benchmark rate for floating rate loan products, apart from external market benchmark rates. The floating interest rate based on external benchmarks should, however, be equal to or above the Base Rate at the time of sanction or renewal. This methodology should be adopted for all new loans. In the case of existing loans of longer / fixed tenure, banks should reset the floating rates according to the above method at the time of review or renewal of loan accounts, after obtaining the consent of the concerned borrower/s. CHAPTER 4 4.1 The existing regulatory framework allows banks to offer all categories of loans on fixed or floating rates, subject to conformity to their Asset-Liability Management (ALM) guidelines. The methodology of computing the floating rates should be objective, transparent and mutually acceptable to counter parties. The Base Rate could also serve as the reference benchmark rate for floating rate loan products, apart from external market benchmark rates. The floating interest rate based on external benchmarks should, however, be equal to or above the Base Rate at the time of sanction or renewal12. 4.2 For floating rate loans, banks add a spread reflecting the product specific operating cost together with term premium and credit risk premium to a benchmark. While using Base Rate as the benchmark, ideally the interest rate charged to a customer should not change at the time of reset unless (a) there is a change in the Base Rate or (b) there is a change in the credit profile of a customer thereby leading to change in credit spread charged. Further, in case there is a change in the policy rate by the Reserve Bank, it should impact the Base Rate, albeit with a lag, and not the spread component of the interest rate. Any deviations from these may lead to customer dissatisfaction, which may accentuate if there is a lack of transparency in pricing of loans by banks. 4.3 A general rise in customer awareness and improvements in the Banking Ombudsman Scheme has encouraged customers to raise issues affecting them. One of the oft repeated queries is the interest rate charged on advances. There have been instances where the spread charged to a customer had been revised upward frequently during the tenure of a floating rate loan, despite no adverse change in the credit profile of the customer. Customers did not have adequate information about the working of a floating rate loan and felt that they had to pay a higher rate due to upward revision of the benchmark in a rising interest rate scenario but banks were very slow in adjusting the base rate and extended loan at a lower rate to new customers. Hence, the existing customers did not get the same benefit in a falling interest rate cycle. This has resulted in the existing customers finding themselves at a disadvantage as compared to the new customers with the same credit profile, resulting in existing customers complaining about discrimination. 4.4 Discrimination between new and existing home loan customers with floating rate of interest is a long standing issue of discontent with the customers of banks. The dissatisfaction is more pronounced in longer tenure loans with floating interest rates. Since interest rates on long term retail loans, like home loans, are based primarily on the quantum of loan and involve less of individual credit rating, the rationale for charging different spread in similar loans is not apparent. 4.5 Apart from the issue of arbitrary change in the spread for existing customers, there have been instances of customers with similar credit profile being charged different spreads at a given point in time. Moreover, customers with similar credit profile coming to a bank at different points in time have been charged different floating interest rates, with no change in either the RBI policy rate or the credit profile of the customers. 4.6 Ideally, any change in the policy rate should impact the benchmark rate but not the spread charged to the customer. However, any change in the credit profile of the customer may alter the spread charged. A change made in the spread due to change in policy rate is likely to be perceived as discriminatory. Pricing of loan - Benchmark Rate 4.7 In the context of floating rate loans, it is important to assess the effectiveness of the transmission of the RBI policy rate to the benchmark. A good lending rate benchmark should be responsive to changes in the policy rate of the central bank. It is only then that the central bank can achieve the desired objectives through monetary policy actions. The success of conduct of monetary policy eventually depends on the strength and speed of the transmission of monetary policy impulses. 4.8 The WG studied the experience on transmission of monetary policy of some countries. Cross-country study on the transmission of monetary policy impulses to bank deposit and lending rates across USA and major European countries reveals that the pass-through to both short- and long-term interest rates is far from complete and presents evidence of heterogeneity across various retail products and banks. Importantly, the study has also thrown factors that are conducive for faster and stronger pass-through as also, those factors that are likely to impede the pass-through.

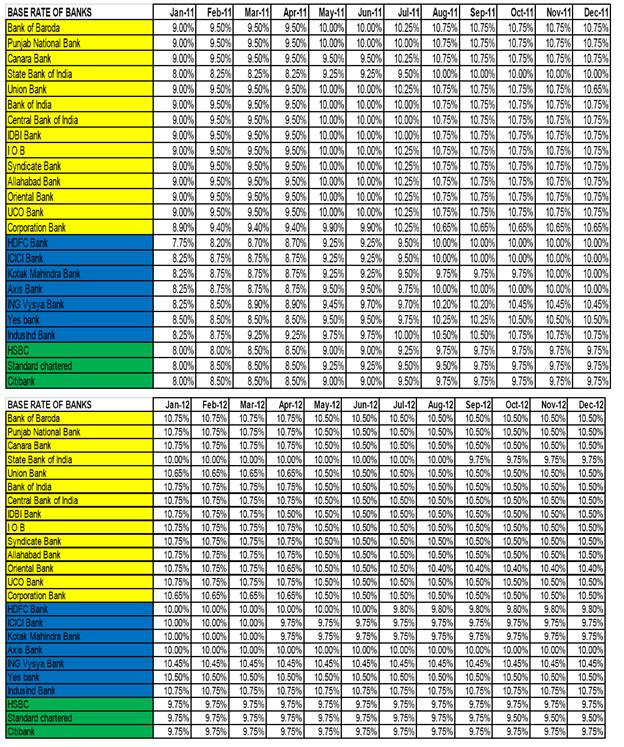

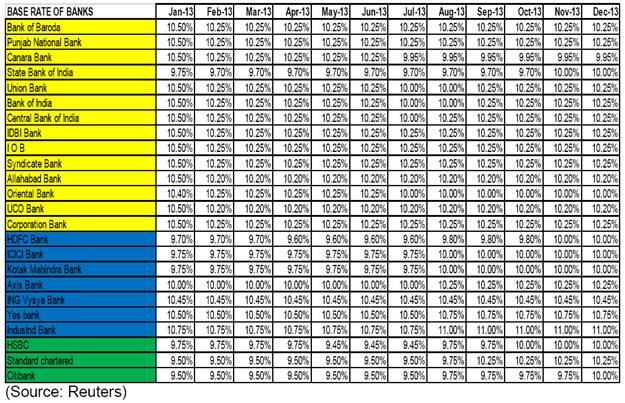

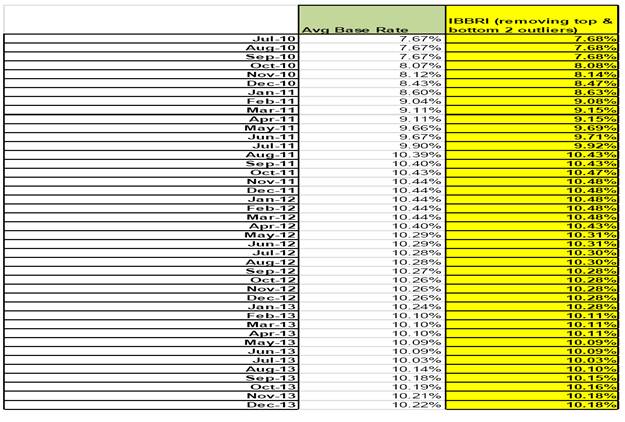

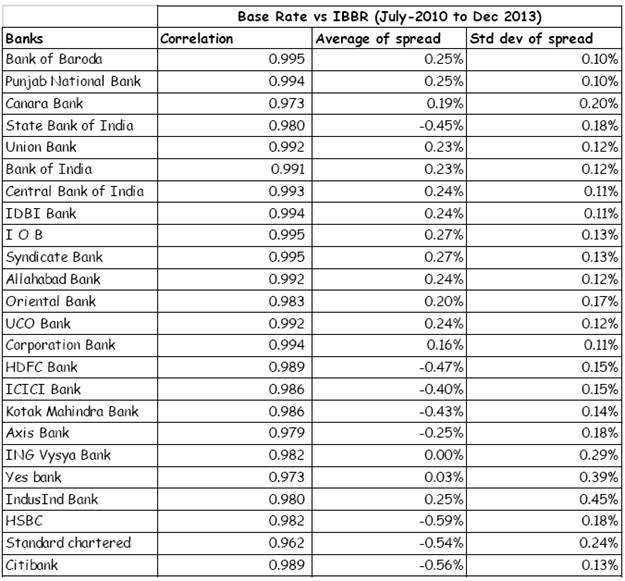

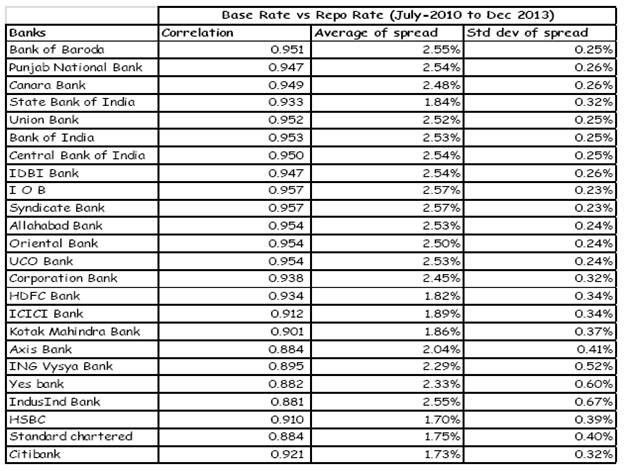

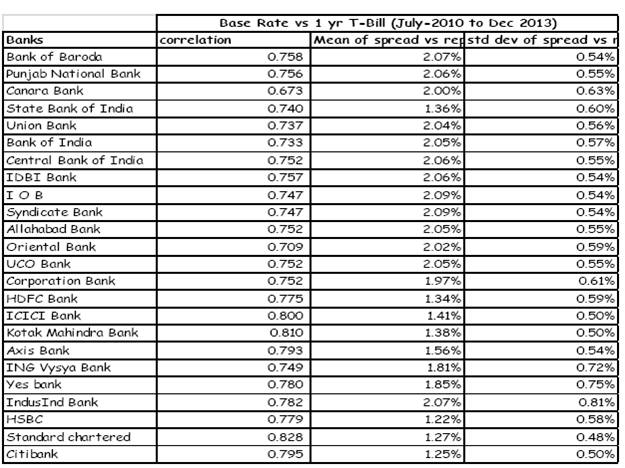

4.9 Ideally, banks with lower cost of funds aided by higher CASA may not necessarily increase the lending rates when the policy rate is increased as long as their margin expectations are fulfilled. These banks can leverage this advantage to maximise their respective market shares. On the other hand, such banks may try to reduce the Base Rate as soon as the policy rate is moderated (as they already enjoy lower cost of funds) and hence, to maximize their market share, they may not want to wait till the impact of reduction in policy rate is fully felt on their respective cost of funds. 4.10 It can also be argued that the RBI policy rate is at best, a signal/ symbolic rate that indicates where the interest rates are headed in the economy and hence, individual banks may take the necessary judgement call on changes in their interest rates in response to the change in the policy rate depending upon their cost of funds and strategy, etc. 4.11 However, the movement in the Base Rate of a few banks vis-à-vis the RBI repo rate indicates that while the increase in policy rate led to a corresponding increase in the Base Rate of banks, the Base Rate showed “stickiness” and did not come down quickly enough when there was reduction in the policy rate (Chart 1). 4.12 Further, looking at the responsiveness of the Indian banks in terms of change of their Base Rate in response to changes in the policy rate by the Reserve Bank of India, it could be seen (Table 1) that the pace of increase in the Base Rate relative to that of the repo rate slowed down as larger banks kept their Base Rates unchanged, possibly due to gradual moderation in the growth of economic activity and the resultant slowdown in the growth of non-food credit, in particular from end-May 2011 to end-March 2012. Subsequently, as the RBI reduced its repo rate in phases by 125 bps during April 17, 2012-September 19, 2013, 33 banks accounting for around 75 per cent of aggregate credit reduced their Base Rates by, on average, 40 bps during the period. On an average, these banks revised their Base Rates with a longer gap of 591 days, indicating downward rigidity during the reverse cycle of interest rates. Banks reduced their modal base rate by 50 bps and the weighted average lending rates (WALR) by 37 bps during the same period (Table 1). During September 20-October 29, 2013, when the Reserve Bank raised the repo rate in two steps of 25 bps each to 7.75 per cent, 7 banks accounting for around 14 per cent of aggregate credit increased their Base Rates by, on average, 2 bps during the period. On an average, these banks revised their Base Rates with a relatively lower gap of 206 days than that during reverse cycle of interest rates. The modal base rate though remained unchanged at 10.25 per cent during the period, WALR reduced marginally by 6 bps

4.13 It may be said that stickiness in the Base Rate may be attributable, primarily, to the deposit profile of banks. Banks with considerable reliance on interest bearing deposits which are fixed in nature do not have the flexibility to pass on the impact of accommodative policy action as the cost of funding represented by the cost of fixed deposits does not decrease immediately with the policy rate cut. It is understood that generally, banks are computing their Base Rate based on the weighted average cost of deposits, and hence, their Base Rate does not lend itself to immediate downward adjustment. The full impact can be seen only when existing fixed rate deposits get rolled over to new lower rates on maturity. 4.14 From a behavioural point of view, depositors enjoy the upside of higher rates (when the policy rate increases) as they have an option of premature withdrawal and reinvestment. On the other hand, under a falling interest rate scenario, depositors benefit by continuing till maturity, with the earlier contracted higher rate deposits. Regulations13 allow withdrawal of rupee term deposits of less than ` one crore before completion of the period of the deposit agreed upon at the time of making the deposit. Banks have the freedom to determine own penal interest rates for premature withdrawal of term deposits. Banks have to inform the depositors of the applicable penal rate upfront. 4.15 However, banks do not have the same freedom as depositors have. This is because deposits form the largest source of funding and the maturity pattern is largely concentrated in fixed tenor deposits. Moreover the distribution of term deposits is tilted in favour of deposits with tenor of 1 year and above. When the policy rate goes up, the cost of deposits is likely to go up due to competition from other banks, thereby forcing banks to increase their lending rates to maintain margins. However, when the policy rate goes down, the average cost of deposits does not go down correspondingly till the existing high interest rate deposits complete their term, leading to a downward stickiness in the interest rates. It is understood that banks are unable to lower their Base Rates since the cost of funds (represented by deposit rates) does not come down. 4.16 Apart from the policy rate changes, there could be other factors that may influence Base Rate. International studies14 have shown that banks’ responses to changes in the policy rate (or market rates) in the short run depend on their size, their capital base, their recourse to funding options, etc. Well capitalized banks are observed to be reacting slowly to the policy changes as compared to banks with lesser capital. 4.17 The Working Group is of the view that the liquidity conditions in the market may also impact the behaviour of the Base Rate. At times of tight liquidity in the market, the interest rates are under pressure and the inter-bank call rates are generally above the policy rate. Under such a scenario, any easing of the policy rate may not impact the Base Rate. However, under the same scenario significant injection of liquidity say through a cut in CRR will infuse substantial liquidity into the system that will lead to lowering of the interest rates, ceteris paribus resulting in faster transmission of policy rate. This way Banks can pass on the benefits to the customers in a more discernible manner. 4.18 The WG also looked at an important feature of the Indian banking structure, viz., pre-dominance of public sector banks whose ownership lies with the Government. These banks have been pivotal to the growth of the Indian economy and have been critical conduits to promote financial inclusion and facilitate credit to agriculture, weaker sections, SMEs, etc. Due to their sheer size and presence, the government as owner can also influence the interest rates in the markets through these banks, which may lead to stickiness in the rates. 4.19 The liability profile of the Indian banks where most of the funding is through fixed interest bearing deposits inhibits quick pass through of policy rate. Table-2 enumerates the maturity pattern of term deposits of Scheduled Commercial Banks in India. Chart-2 represents the weighted average maturity of deposits. 4.20 Given the higher weighted average maturity of deposits and their being on fixed rate basis, banks compute Base Rate primarily using the average cost of funds which does not move in tandem with the policy rate. The changes in the weighted average rate would obviously be lesser than the changes to the policy rate. Illustratively, if a bank having Rs.100 liabilities at a cost of 8%, mobilizes additional wholesale liabilities of `10 at 7% (lower rate due to softening of policy rate), it has two alternatives of pricing its credit. If it adopts marginal cost, it would lend the new loans based on the cost of funds of 7%. Alternatively, it can spread the benefit of lower cost of new liabilities over the entire loan portfolio and revise its Base Rate lower (if that is computed on average cost basis) so that it can lend based on the cost of funds of 7.9%. If the older liabilities (assuming they are contracted at fixed rates like in the case of term deposits) constitute a significant portion, bank will have to wait for all such old liabilities to mature and get rolled over for overall cost to come down significantly below 8%. It appears that some banks find it competitively more attractive to change the spreads and offer the benefit of lower cost of new liabilities to new borrowers rather than effecting Base Rate revision which would impact all borrowers but the impact would be negligible because as illustrated above the Base Rate would be left virtually unchanged. Banks may perceive greater strategic value in extending new loans at lower rates due to lower marginal cost of funds. 4.21 Currently, the deposit profile is predominantly fixed rate, while the loans, especially the home loans are predominantly floating rate. The effect of stickiness in the floating rate loans can be mitigated if such loans are funded by similar liability, i.e. longer term floating rate deposits, thereby making it symmetrical to sensitivity in policy rate. The WG noted that though the regulations do not impede floating rate deposits, these are not popular, and in fact these are virtually non-existent as there is already an implicit option available to the depositors in the form of premature withdrawal of low yielding deposit and replacing it with a higher yielding one (except in cases mentioned in paragraph 4.14). 4.22 Another way to achieve the convergence of profile of deposits and advances is for banks to compute their Base Rates on the basis of the marginal cost of funds. This approach would enhance the response of Base Rate to the policy rate and lead to quicker and more symmetric transmission of monetary policy signals. The pricing of other facilities based on such a Base Rate will get more quickly aligned with changes in the policy rate. Changes in pricing would be more transparent and banks will be less exposed to criticism or complaints than they are now. The WG felt that banks, particularly those whose weighted average maturity of deposits is on the lower side, may consider moving from using the weighted average cost of funds on a historical basis to using the marginal cost of funds while computing the Base Rate. 4.23 Banks whose weighted average maturity of deposits is relatively low (say, around 1 year) may find it relatively easy to migrate to marginal cost of funds to compute their Base rate and pass the benefit of lower policy rate by lowering Base Rate more quickly and thus benefit all customers – both existing as well as the new ones. 4.24 For banks whose weighted average maturity of deposits is on the high side, there would be difficulties in migrating to marginal cost of funds to compute their Base Rate. 4.25 The WG deliberated at length the appropriateness and feasibility of the use of marginal cost of funds by banks in computing their Base Rate. The WG is cognizant of the difficulties involved in migrating to marginal cost of funds for computing Base Rate for majority of banks due to the maturity profile of deposits. 4.26 Where banks choose to continue using the historical cost of funds for computing the base rate, it would be unrealistic to expect that they would not pass on the benefit of lower marginal cost of funds to the new customers by operating on the spreads.This would imply that there could be differentiation amongst customers who enter into borrowal relationship with a bank at different points of time. However, the WG wishes to emphasise that no bank can discriminate among borrowers who get into borrowing relationship with a bank at the same time, i.e., in identical or similar funding conditions. Any difference in pricing in such cases must be based on objective criteria for determining the mark up or spread over the base rate while determining lending rate for the borrowers. It is important to be clear about what these criteria might be. In other words, on what grounds does a bank distinguish between customers who enter into a relationship with it at the same time and also have the same credit risk profile? In what follows, the WG seeks to address this question. 4.27 At the time of pricing of floating rate loans, banks add spreads to the benchmark rate to arrive at the interest rate charged to the borrower. In terms of the guidelines on Base Rate, the spread should be a function of product specific operating cost, credit risk premium and the tenor premium. 4.28 Apart from the aforesaid components of the spread, there are other behavioural factors such as competition, customer relationship and business strategy that also get factored in while determining the lending rates. In any formulation on this issue, these factors need to be considered. Banks contend that parameters such as future business potential of a customer, value of the relationship and business strategy are some ‘soft’ parameters which are difficult to quantitatively establish but surely form a part of their pricing. However, arbitrary inclusion of these factors into pricing may lead to discrimination among customers. 4.29 The WG agreed that while price differentiation among old and new customers would remain where the Base Rate is calculated on the basis of weighted average cost of deposits, price discrimination cannot be accepted. Price differentiation will imply different pricing for customers with identical credit profile due to varying conditions. One reason for difference in pricing that has been highlighted earlier is that customers may establish borrowing relationships at different point of time when the marginal cost of funding has declined due to lowering of policy rate (while the base rate remains unaffected because it is computed using historical cost of funds). To this, other factors need to be added that could result in differences in pricing between customers with identical risk profiles. At a given point in time, a bank may pursue a business strategy whereby it wishes to acquire a greater share of a product market or wants to enter into a new segment where there are established players. It may adopt an aggressive strategy and make loans to new customers at a lower rate. Value of relationship would be another factor resulting in concession in the interest rates on loans given where bank expects to gain fee-based business or deposit accounts or more business in future. Price discrimination would occur if a bank offers different prices on loans to two customers with identical credit profile and without any of the other factors mentioned above entering the picture. 4.30 WG is of the view that it will be the responsibility of the Board of bank to ensure that the customers are not being discriminated against and the differentiation in pricing of credit is occurring only due to specified factors, such as competitive conditions, customer relationship and business strategy. In order to ensure that these factors are not used arbitrarily, the Board of a bank must ensure that pricing is consistent with bank’s target for Risk Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC). 4.31 The WG recommends that it would be desirable that banks, particularly those whose weighted average maturity of deposits is on the lower side, move towards computing the Base Rate on the basis of marginal cost of funds as this may result in more transparency in pricing, reduced customer complaints, better transmission of changes in the policy rate and improved asset liability management at banks. If banks are using weighted average cost of funds because of their deposits profile or any other methodology that may result in differentiation between old and new customers, the Boards of banks should ensure that this differentiation does not lead to any discrimination amongst borrowers. Discrimination would occur if a bank offers different prices on loans to customers with identical credit profile, every other factor being the same. 4.32 The WG acknowledges that apart from factors like specific operating cost, credit risk premium and tenor premium, broad factors like competition, business strategy and customer relationship are also used to determine the spread. Banks should have a Board approved policy delineating these components. The Board of a bank should ensure that any price differentiation is consistent with bank’s credit pricing policy factoring RAROC. Banks should be able to demonstrate to the Reserve Bank of India the rationale of the pricing policy. 4.33 It was felt that these factors, viz., competition, business strategy and customer relationship, are very broad factors that may encompass a number of components. Strategy may incorporate a number of factors such as position/strategy of other banks, stage of economic cycle, bank concentration in an area, etc. Customer relationship may include factors like customers’ business with bank, size of loan, size of the business of the customer and duration of ties of the customer with a bank, etc. The WG realised that it would not be practical to prepare an exhaustive list of factors that may be clubbed under business strategy and customer relationship. 4.34 Further, it is possible in this framework for a bank to arbitrarily bring in any factor as strategy or competition to price the spread, and this could put some customers at a disadvantage. Moreover, each bank may use a different combination of such factors to price the spread for relationship, strategy or competition. The WG therefore felt that the Board of a bank would be in the best position to assess the optimal bouquet of such factors that it determines should be clubbed under these parameters to price the spread. The WG recommends that banks’ internal policy must spell out the rationale for, and range of, the spread in the case of a given borrower, as also, the delegation of powers in respect of loan pricing. 4.35 Arbitrary change in contracted spread has also resulted in complaints by the customers. It is understood that likely reasons for change in contracted spread is to adjust the impact of changes in policy rate, or any other factor like liquidity in the system, etc. The WG felt that for a given customer, once a spread has been determined after looking at all factors including customer’s credit profile, customer relationship with bank, strategy, etc., such spread should not be increased except on account of deterioration in the credit risk profile of the customer. There should be a loan covenant to this effect. Apart from this, the WG felt that other externalities should not impact the contracted spread for a given customer. The WG recommends that the spread charged to an existing customer cannot be increased except on account of deterioration in the credit risk profile of the customer. The customer should be informed of this at the time of contract. Further, this information should be adequately displayed by banks through notices/website. 4.36 Under the current system, when the Base Rate changes, the interest rates on credit are adjusted simultaneously. This has implications for Asset-Liability management. The WG considered this aspect and is of the opinion that any change in the Base Rate need not result in an immediate change in the floating interest rates on the existing loans. The covenant of the floating rate may have mandatory reset dates (monthly, quarterly, half-yearly, etc.) and the existing loans may be reset on the dates agreed upon in the covenant. Hence, the benefit of reduction in the Base Rate shall be passed on to the customer on the reset date, whereas the new borrowers would get the reduced rate at the time of entering into the agreement. However, if the rates are increased, then the existing loan holders get the advantage of the period till the next reset date, whereas the new borrower would have to pay higher rate prevailing at that point in time. In any case, banks get benefited in terms of better risk management as they would know upfront when the rates are likely to be changed while the customers know when to expect changes in interest rates on the existing loans. The WG recommends that the floating rate loan covenant may have interest rate reset periodicity and the resets may be done on those dates only, irrespective of changes made to the Base Rate within the reset period. One member, State Bank of India, however is of the view that whenever there is a change in the Base Rate, such changes should be passed on to the customers. 4.37 Though the Base Rate system has replaced the BPLR system with effect from July 1, 2010, and is applicable for all new loans and for those old loans that come up for renewal, some of the existing loans based on the BPLR system continue to be in the system and may run till their maturity. In case existing borrowers wanted to switch to the Base Rate system before expiry of the existing contracts, an option was given to them, on mutually agreed terms. 4.38 Continuation of contracts under the BPLR regime leaves an element of operational inconvenience for banks. Moreover, the intended benefit of the Base Rate regime, viz., shifting of the old BPLR linked borrowers to the Base Rate system could not manifest itself in the true sense as it is understood that those customers who shifted from BPLR to the Base Rate regime were charged a spread different / higher than the borrowers who entered newly / directly under the Base Rate system thereby again leading to discrimination between old and new customers. The WG recommends that there may be a sunset clause for BPLR contracts so that all the contracts thereafter are linked to the Base Rate. Banks may ensure that these customers who shift from BPLR linked loans to Base Rate loans are not charged any additional interest rate or any processing fee for such switch-over. 4.39 Apart from the Base Rate, Indian banks have been allowed to use external benchmarks to facilitate pricing of floating rate interest rates. A number of external benchmarks are available in the Indian markets, viz., Mumbai Inter-bank Offered Rate (MIBOR), G-Sec yields, Repo Rate, CP and CD rates, etc. However, these benchmarks have drawbacks - they are mainly driven by liquidity conditions in the market, as also, these do not reflect the cost of funds of banks. Further, these benchmarks are volatile and may lead to frequent changes in the floating rate. 4.40 It has been discussed in the previous paragraphs that the legacy deposits structure at some banks may prevent them from changing the Base Rate in response to the changes in the RBI policy rate. To obviate the constraints in using a bank’s Base Rate as benchmark, the WG studied the benchmark indices used in different countries over which the floating interest rates loans are priced.