IST,

IST,

Financial Stability

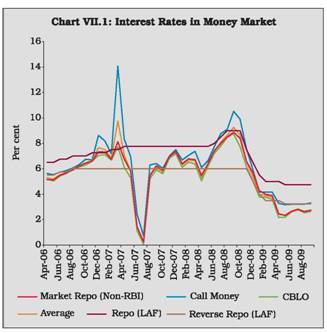

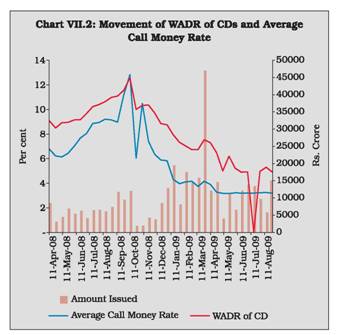

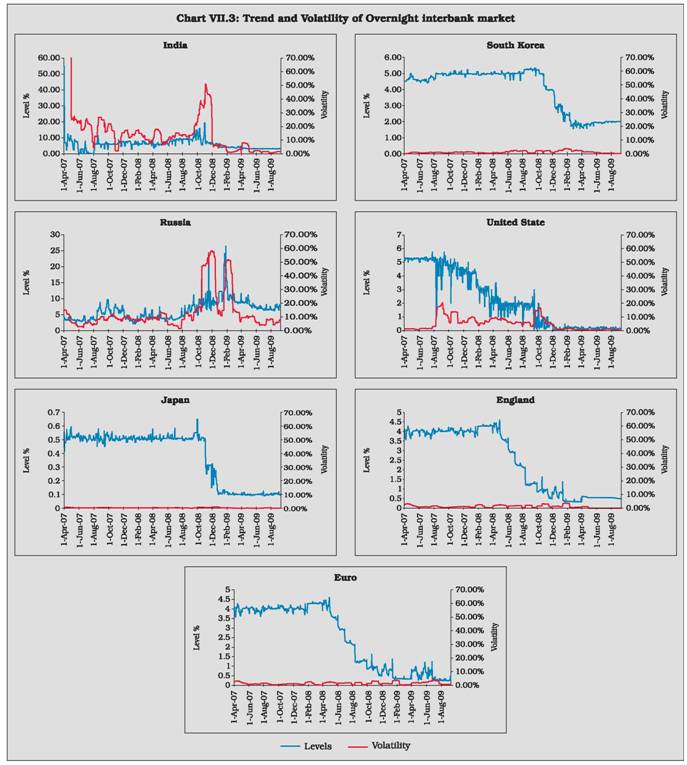

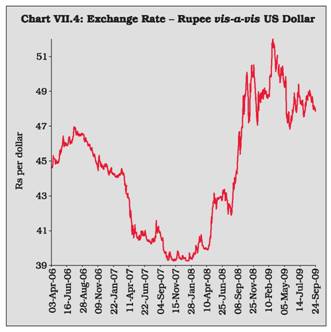

Following the global financial crisis, financial stability has emerged as an important objective of central banks across countries in the world - both developed and emerging market economies (EMEs). Unlike monetary policy frameworks, it is difficult to define financial stability framework. There are conceptual and measurement issues. A number of countries, however, have initiated financial stability analysis in terms of undertaking financial stability reports to assess the risks and outlook for financial stability. Along with a discussion of these issues, this chapter recounts the Indian experience with financial stability alongside price stability. While the traverse so far has been successful, way ahead, as is the case globally, there are significant challenges in attaining the objectives of financial stability as India gets further globalised. 1. Introduction 7.1 Following the global financial crisis, financial stability has emerged as an important objective of central banks across countries in the world – both developed and EMEs, notwithstanding the long period of macro-economic stability in terms of growth and inflation. The crisis occurred on a massive scale leading to the collapse of the financial markets and institutions bringing the financial stability issues to the forefront of policy discussions. 7.2 On the hindsight, the present crisis appears to be a result of a macroeconomic environment with a prolonged period of low interest rates, high liquidity and low volatility, which led financial institutions to underestimate risks, a breakdown of credit and risk management practices in many financial institutions, and shortcomings in financial regulation and supervision. A slowdown in the US real estate market triggered a series of defaults and this snowballed into accumulated losses, especially in the case of complex structured securities. The US subprime crisis has led to both the strained conditions of financial markets and the slowdown of the broader economy. The US economy continues to confront substantial challenges, including stresses in financial markets, a weakening labour market and deteriorating economic activity. The problems intensified significantly around mid-September 2008, when major losses led to failure of major financial institutions, namely Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. 7.3 It was the abrupt breakdown of trust following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in mid-September 2008 that caused financial markets in advanced economies to go into seizure. Suddenly, there was a great deal of uncertainty not only about the extent of losses and the ability of banks to withstand those losses, but also about the extent of risk in the system, where it lay and how it might explode. This uncertainty triggered unprecedented panic and almost totally paralysed the entire chain of financial intermediation. Banks hoarded liquidity. Credit, bond and equity markets nearly froze. Signaling a massive flight to safety, yields on Government securities plunged while spreads over risk free Government securities shot up across market segments. Several financial institutions came to the brink of collapse. Massive deleveraging drove down asset prices setting off a vicious cycle. Trust totally dried up. 7.4 Although the epicentre of the crisis lay in the advanced economies, it soon spread in two directions. In the advanced economies, it spread from the financial sector to the real sector severely hurting consumption,investment, export and import. It spread geographically from the advanced economies to the EMEs and soon engulfed almost the entire world through trade, finance and confidence channels. 7.5 Among the several lessons of the crisis, prominent ones with respect to financial stability are: first, financial stability that had grown to be taken for granted cannot be taken for granted; second, financial stability can be jeopardised even if there is price stability and macroeconomic stability; third, financial stability anywhere in the world is potentially a threat to financial stability everywhere; and finally, financial stability has to shift from being an implicit variable to an explicit variable of economic policy1. 7.6 Central bankers around the world are clearly in the forefront battling the crisis. While they are clearly a part of the solution, questions are being asked about whether they were, in fact, part of the problem. Over the past two decades, revisions to the monetary policy framework appear to have been successful in the combat of inflation in a number of countries. Over the same period, financial stability frameworks have not kept pace. 7.7 Financial stability failed to receive central bank attention it warranted. The risks to financial stability were brewing silently as manifested in growing threats from macro economic imbalances, asset price build up, credit expansion and depressed risk premia. But central banks largely refrained from strong corrective action for a variety of reasons such as the perceived inefficiency of monetary policy to redress asset price bubbles, separation of monetary and regulatory policies, and misplaced faith in the self-correcting forces of financial markets. 7.8 In contrast to the global scenario, India has by-and-large been spared of the global financial contagion. Even in the midst of the crisis, India’s financial sector remained safe and sound and financial markets continued to function normally. There can be a variety of reasons. The credit derivatives market is in an embryonic stage; the ‘originate-to-distribute’ model in India is not comparable to the ones prevailing in advanced markets; there are restrictions on investments by residents in such products issued abroad; and regulatory guidelines on securitisation do not permit immediate profit recognition. Financial stability in India has been achieved through perseverance of prudential policies which prevent institutions from excessive risk taking, and financial markets from becoming extremely volatile and turbulent. As a result, while there are orderly conditions in financial markets, the financial institutions, especially banks, reflect strength and resilience. While supervision is exercised by a quasi-independent Board carved out of the Reserve Bank’s Board, the interface between regulation and supervision is close in respect of banks and financial institutions and on market regulation, a close coordination with other regulators exists. 7.9 In this perspective, spread over eight sections, this chapter addresses the primary question of conceptual aspects of financial stability and its measurement in Section 2; an account of financial stability analysis by the central banks through the ‘Financial Stability Reports’ in Section 3; Global Initiatives towards Financial Stability in Section 4; an assessment of the India’s financial system in Section 5; domestic financial markets are discussed in Section 6; Section 7 discusses India’s approach to financial stability explaining how India achieved this in the last two years. Key sources of vulnerability of Indian financial system are also addressed in this Section. Section 8 concludes the chapter with an overall assessment and challenges to financial stability on the way forward. 2. Financial Stability: Concept and Measurement 7.10 The challenge of monetary policy is to strike an optimal balance between preserving financial stability, maintaining price stability, anchoring inflation expectations, and sustaining the growth momentum2. The relative emphasis between these objectives has varied from time to time, depending on the underlying macroeconomic conditions. The global financial crisis has underlined the importance of preserving financial stability and this has made the task for the conduct of monetary policy even more complex and challenging than before. What is Financial Stability? 7.11 Financial stability, as a concept, is widely known. However, there is no unanimous agreement on a working definition of this concept. Some define financial stability in terms of what it is not, i.e., the absence of financial instability. Others take a macro-prudential view and specify financial stability in terms of limitation of risks of significant real output losses in the presence of episodes of system- wide financial distress. Financial stability is a situation in which the financial system is capable of satisfactorily performing its three key functions simultaneously. First, the financial system is efficiently and smoothly facilitating the inter-temporal allocation of resources from savers to investors and the allocation of economic resources in general. Second, forward-looking financial risks are assessed and priced reasonably accurately and are relatively well- managed. Third, the financial system is in such a condition that it can comfortably, if not smoothly, absorb financial and real economic surprises and shocks. If any one or more of these key functions are not being satisfactorily performed. It is likely that the financial system is moving in the direction of becoming less stable, and at some point might exhibit instability. For example, inefficiencies in the allocation of capital or shortcomings in the pricing of risk can, by laying the foundations for imbalances and vulnerabilities, compromise future financial system stability. Why Study Financial Stability? 7.12 Since the early 1990s, safeguarding financial stability has become an increasingly dominant objective in economic policy making. Financial stability has been stated as a public good3. The greater emphasis on financial stability is related to several major trends in the financial system, reflecting the expansion of liberalisation and subsequent globalisation of financial system, all of which have increased the possibility of larger adverse consequences of financial instability on economic performance. First, financial systems have expanded at a significantly higher pace than the real economy. Second, this process of financial deepening has been accompanied by changes in the composition of the financial system, with a declining share of monetary assets and increasing share of non-monetary assets, and by implication, greater leverage of the monetary base. Third, as a result of increasing cross-industry and cross-border integration, financial systems have become more integrated, both nationally and internationally. Fourth, the financial system has become more complex in terms of the intricacy of financial instruments, the diversity of activities and the concomitant mobility of risks. In general, the greater complexity, especially the increase in risk transfers, has made it more difficult for market participants, supervisors, and policy makers alike to track the development of risks within the system and over time. Notwithstanding thecontribution of the above trends to economic efficiency, they have had implications for the nature of risks and vulnerabilities in the financial system and its potential impact on real economy, as well as for the importance of financial stability in policy making. 7.13 Unlike monetary stability, which is measured by inflation and monetary indicators, financial stability is not easy to define or measure given the inter-dependence and the complex interactions of different elements of the financial system among themselves and with the real economy. This is further complicated by the time and cross-border dimensions of such interactions. Financial stability, thus, is not well defined and cannot be easily measured. 3. Central Banks and the Financial Stability Reports 7.14 Conceptual and measurement issues with regard to financial stability notwithstanding, over the past two decades, researchers from central banks and elsewhere have attempted to capture conditions of financial stability through various indicators of financial system vulnerabilities. Indeed, many central banks through their Financial Stability Reports (FSRs) attempt to assess the risks to financial stability by focusing on a small number of key indicators. Both types of central banks, those focussed on single objective such as price stability and those focused on multiple objectives, such as economic progress, price stability and sound and strong external sector, publish FSRs (Box VII.1 and Annex VII.1). 7.15 Moreover, there are ongoing efforts to develop a single aggregate measure that could indicate the degree of financial fragility or stress. Composite quantitative measures of financial system stability that could signal these conditions are intuitively attractive as they could enable policy makers and financial system participants to: (a) better monitor the degree of financial stability of the system, (b) anticipate the sources and causes of financial stress to the system and (c) communicate more effectively the impact of such conditions. 7.16 Composite indicators of financial stability are better suited for the definition of threshold or benchmark values to indicate the state of financial system stability than individual variables. Moreover, they are useful measures of stress (e.g., they can be used to gauge the buildup of imbalances) in the system even in the absence of extreme events. However, the construction of a single aggregate measure of financial stability is a difficult task given the complex nature of the financial system and the existence of its complex links between various sectors. In the absence of an overarching aggregate, partial composite measures, such as a banking stability index or a market liquidity index are used in several FSRs. Regardless of whether a single aggregate measure of financial stability is constructed or not, FSRs would need to analyse key variables in the real, banking and financial sectors as well as variables in the external sector. 7.17 There is some diversity in construction and use of the key indicators. For broader crosscountry comparisons, it would be useful to have an appropriate template and methodology for such indicators, although individual circumstances of countries make such an exercise difficult (due, notably, to the varying relative importance of individual financial system components and to differing degrees of openness of the economies concerned). If one tries to compute a single aggregate measure of financial stability, the weightings of the different variables that constitute such an aggregate measure have to reflect these differences accordingly. 7.18 Although some central banks have experimented with computing single aggregate measures of financial stability, no such measures can be used without knowledge and use of other quantitative or qualitative instruments. Moreover, single aggregate measures reflect the financial system conditions well post facto, it is not yet clear how well they would perform in signaling the onset of financial stress. Box VII.1: Financial Stability Reports of Central Banks: Comparative Assessment A review of the FSRs brought out by various central banks shows that as many as 67 central banks across the developed and the emerging market economies are periodically publishing a separate report on the subject of financial stability (Annex to the Chapter). The first standalone FSR was published in 1996 in the UK, which was followed by several Nordic countries. Since then, the number of central banks publishing FSRs grew to 25 in 2004 and further to 67 in 2008. Out of these, a majority of the central banks publishing FSRs belong to Europe. Some of the Asian countries that publish FSRs include Japan, Korea, Hong Kong SAR, Singapore, China, Philippines, Indonesia and lately, Malaysia. Recently, a few African (Ghana, Kenya and South Africa) and Middle East (Israel and Qatar) countries have also begun publishing FSRs. In the south Asian region, India’s neighbouring countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh are also publishing such reports. While many multilateral institutions/central banks such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the Group of Twenty, the International Association of Insurance Supervisors and the European Central Bank (ECB) deal with financial stability related issues, standalone FSRs are brought out regularly by only two such institutions, namely, the IMF and the ECB. Central banks publish financial stability reports for various reasons. Based on a survey, Oosterloo and Haan (2004), state that there are three main reasons for publishing the assessment of financial stability in the form of a FSR: (i) to contribute to the overall stability of the financial system; (ii) to strengthen cooperation on financial stability issues between the various relevant authorities; and (iii) to increase the transparency and accountability of the financial stability function. It seems that for most central banks the ultimate objective of FSRs is their contribution to financial stability. According to the Bank of England, the Financial Stability Review aims: (i) to promote the latest thinking on risk, regulation and financial markets; (ii) to facilitate discussion of issues that might affect risks to the UK financial system; and (iii) provide a forum for debate among practitioners, policy makers and academics. Articles published in the Financial Stability Review, whether written by the Bank or Securities and Investment Board (SIB) staff or by outside contributors, are intended to contribute to the debate, and are not necessarily statements of the Bank or SIB policy. According to Banque de France, in a globalised and increasingly complex financial environment, assessing and fostering financial stability requires strengthened co-operation between the various relevant authorities viz., Governments, central banks, market regulators and supervisors. They also presuppose that a close dialogue to be maintained with all financial sector professionals. It is in this spirit that the Banque de France, like several other central banks, has decided to publish a periodic Financial Stability Review. According to the ECB, in publishing this Financial Stability Review, the ECB is joining a growing number of central banks around the world that are addressing their financial stability mandates in part through the periodic issuing of a public report. The purpose of publishing this review is to promote awareness in the financial industry and among the public at large of issues that are relevant for safeguarding the stability of the euro area financial system. By providing an overview of sources of risk and vulnerability to financial stability, the review also seeks to help prevent financial tensions. A similar view is echoed by central banks in some emerging economies. According to the central bank of Brazil, the practice of central banks publishing analyses of financial system performance is highly recommended from the point of view of monetary authority’s transparency and the expectations of economic agents. According to the Singapore Monetary Authority, the Financial Stability Review analyses the risks and vulnerabilities arising from domestic and global developments and assesses their implications for the soundness and stability of the domestic financial system. The FSR aims to contribute to a greater understanding and exchange of views among market participants, analysts and the public on issues affecting the country’s financial system. Some FSRs explicitly recognise reduction of financial instability as their ultimate objective. According to the Bank of Canada, FSRs one avenue through which it seeks to contribute to the longer-term robustness of the domestic financial system. It can do so by: (i) improving the understanding of (and contributing to dialogue on) risks to financial intermediaries in the economic environment; (ii) alerting financial institutions and market participants to the possible collective impact of their individual actions; and (iii) building a consensus for financial stability and the improvement of the financial infrastructure. An FSR can add value to work undertaken by private agents in the financial sector itself, because a central bank can draw on its macroeconomic expertise and its role in payments and settlements. Also, private agents do not have as strong an incentive to assess the systemic risks in the economic environment, as they are less interested in spillovers of their actions on to other agents. Finally, there is a need to educate the public about the costs of infrequent but catastrophic episodes of instability (analogous to the need of the monetary policy side to build a constituency for low inflation). Reference:

7.19 Generally, central banks derive financial stability responsibility from four principal areas: (i) regulation and supervision of banking sector; (ii) oversight of the payment system; (iii) the lender of last resort function; and (iv) an integral and major element of the coordinated framework encompassing multiple regulators for the achievement of overall stability of the financial system. First, directly as regulator and supervisor of deposit taking commercial banks and also deposit taking non-banking institutions, several central banks are entrusted with the responsibility for a sound, safe and stable financial system. Moreover, the deposit taking banks and non-bank entities constitute the major pillar of financial system due to their dominant role in intermediation of savings and deployment of resources for investment, and the stability of key institutions and markets assume critical importance for the stability of whole financial system. Second, central banks have a key role in promoting a safe and efficient payment and settlement system. According to the Riksbank of Sweden, the payment system is important for all economic activities and is a central component of the financial system. For that reason, the Riksbank regularly analyses the risks and threats to the stability of the Swedish payment system. Third, central banks, due to their lender of last resort function, assume critical importance in providing liquidity support for mitigating the financial crisis. According to the Peoples’ Bank of China (PBC), the central bank of a country has a ‘natural role’ in maintaining financial stability, as it is the lender of last resort and plays an important role in maintaining liquidity in the financial system. Fourth, in some countries where the banking regulation and supervision is vested in a separate authority and the stability of the financial system entrusted to a super regulator or umbrella organisation which coordinates with various types of financial regulators, central banks are accorded a dominant position in this framework. From operational angle, some central banks serve as chairman of the coordinated system for financial system stability. Illustratively, in Australia, the Council of Financial Regulators which brings together the Treasury – the fiscal authority, the central bank – the monetary authority, Australian Prudential Regulation Authority – the banking regulator and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) – the capital market regulator, is chaired by the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Thus, the RBA is entrusted with the ultimate responsibility to contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of regulation and the stability of the financial system. 7.20 Globally, financial stability has assumed significance because of the tendency of financial turbulence to spill across borders. This is amply illustrated by the ongoing crisis which has brought the issue of financial stability to the forefront. What started as a sub-prime crisis in the US housing mortgage sector has turned successively into a global banking crisis, global financial crisis and now a global economic crisis. Apart from the current one, in recent years, crises in Mexico (1994), Asia (1997), Turkey (1999) and Argentina (2001) entailed significant costs to the countries concerned and also exerted serious corollary damage on neighbouring countries, which induced Governments and multilateral institutions to be more proactive in preventing and resolving financial crises. Even as countries across the globe are trying to come to terms with what is purportedly the biggest downturn in economic activity since the Great Depression, the world over there is renewed emphasis on maintaining financial stability. Some of the factors that can lead to financial instability include unsustainable macroeconomic policies, fragile financial systems, regulatory gaps, institutional weaknesses and flaws in the structure of the international financial architecture. It is recognised that there is no fail-safe method for ensuring financial stability as volatility is an intrinsic feature of financial markets. It is, however, desirable to take preventive measures so as to reduce the incidence of disruptive and costly financial crises. Thus, countries need to be vigilant about and take initiatives to address each of the five causes of financial instability enumerated above. This would include limiting macroeconomic sources of financial vulnerability, strengthening the financial infrastructure and undertaking swift remedial measures for early and quick resolution of financial crises, if and when they occur. 7.21 There are various issues relating to central banks’ financial stability goal, mandatein publishing FSR, the title of the report, commencement, periodicity and size of thepublication, dissemination policy,chapterisation scheme, coverage and the methodology used in the various reports. There are also issues about whether the central bank that brings out FSR is a bank regulator or not and whether financial stability is a mandated function of the central bank through any legislative framework (Annex VII.1). 7.22 Policymakers and academic researchers have focused on a number of quantitative measures in order to assess financial stability. The set of Financial Soundness Indicators developed by the IMF (2006) are examples of such indicators apart from monitoring variables which focus on market pressures, external vulnerability and banking system vulnerability. Annex VII.2 summarises the measures commonly used in the literature, their frequency, what they measure, as well as their signaling properties. As can be seen, the focus is on six main sectors (Box VII.2 and Annex VII.2). 7.23 Typically financial stability analysis would use several sectoral variables either individually or in combinations. The use of such measures including the financial soundness indicators as key indicators of financial stability depends on the benchmarks and thresholds which would characterise their behaviour in normal times and during periods of stress. In the absence of benchmarks, the analysis of these measures would depend on identifying changes in trend, major disturbances and other outliers. Box VII.2: Key Financial Stability Segments and Variables Firstly, the real sector is described by GDP growth, the fiscal position of the Government and inflation. GDP growth reflects the ability of the economy to create wealth and its risk of overheating. The fiscal position of the Government mirrors its ability to find financing for its expenses above its revenue (and the associated vulnerability of the country to the unavailability of financing). Inflation may indicate structural problems in the economy, and public dissatisfaction which may in turn lead to political instability. Secondly, the corporate sector’s riskiness can be assessed by its leverage and expense ratios, its net foreign exchange exposure to equity and the number of applications for protection against creditors. Thirdly, the household sector’s health can be gauged through its net assets (assets minus liabilities) and net disposable income (earnings minus consumption minus debt service and principal payments). Net assets and net disposable earnings can measure households’ ability to weather (unexpected) downturns. Fourthly, the conditions in the external sector are reflected by real exchange rates, foreign exchange reserves, the current account, capital flows and maturity/ currency mismatches. These variables can be reflective of sudden changes in the direction of capital inflows, of loss of export competitiveness, and of the sustainability of the foreign financing of domestic debt. Fifthly, the financial sector is characterised by monetary aggregates, real interest rates, risk measures for the banking sector, banks’ capital and liquidity ratios, the quality of their loan book, standalone credit ratings and the concentration/systemic focus of their lending activities. All these proxies can be reflective of problems in the banking or financial sector and, if a crisis occurs, they can gauge the cost of such a crisis to the real economy. Lastly, variables relevant to describe conditions of financial markets are equity indices, corporate spreads, liquidity premia and volatility. High levels of risk spreads can indicate a loss of investors’ risk appetite and possibly financing problems for the rest of the economy. Liquidity disruptions may be a materialisation of the market’s ability to efficiently allocate surplus funds to investment opportunities within the economy. Reference: Blaise Gadanecz and Kaushik Jayaram (2009), ‘Measures of Financial Stability’ – A Review, BIS. 7.24 Since risk assessment is a continuous process and stress tests need to be conducted taking into account the macroeconomic linkages as also the second round effects and contagion risks, consequent to the announcement in the Annual Policy Statement for 2009-10, an interdisciplinary Financial Stability Unit (FSU) have been set up in Reserve Bank of India to monitor and address systemic vulnerabilities. FSU is entrusted with the responsibility of bringing out Financial Stability Report in the future. 4. Global Initiatives towards Financial Stability 7.25 The crisis has triggered a vigorous debate on how financial stability should be safeguarded. Several lessons are clear. First, the received wisdom is that prevention is better than cure and that central banks should take countercyclical policy actions to prevent build up of imbalances. Second, a consensus is emerging around the view that central bank purview should explicitly include financial stability. Third, there is a growing acknowledgement that financial stability needs to be understood and addressed both from the micro and macro perspectives. At the micro level, there is a need to ensure that individual institutions are healthy, safe and sound; in addition, there is a need to safeguard financial stability at the macro level. International Cooperation - Recent Initiatives 7.26 Several international initiatives have been taken in the recent period for formulating proposals for strengthening the financial system. The major initiatives in this regard include the following:

Regulatory and Supervisory Initiatives 7.27 Group of Twenty (G-20) has pioneered the regulatory and supervisory reforms. The Group has made several recommendations / plan of actions in this regard and has placed the responsibility for monitoring the implementation plan to the recommendations, with the Finance Ministries, national financial regulators and oversight authorities, central banks, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Financial Stability Board (FSB), and Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) and other similar organisations. Group of Twenty (G-20) 7.28 Report of G-20 (Working Group 1) on ‘Enhancing Sound Regulation and Strengthening Transparency’ (March 2009) has made recommendations, inter alia, to strengthen the international regulatory standards. Some of the major recommendations are (i) system-wide approach to financial regulation, i.e., macro-prudential supervision to supplement the micro-prudential supervision, (ii) expansion of the scope of regulation and oversight to include all systemically important institutions, markets and instruments including private pools of capital (iii) enhancements of international standards for capital and liquidity buffers, (iv) addressing pro-cyclicality aspects of accounting frameworks and capital regulation (v) management of liquidity especially for large and complex cross-border banks (vi) Infrastructure for OTC derivatives especially for the credit default swaps to contain systemic risks. 7.29 G-20 (Working Group 2) on ‘Reinforcing International Cooperation and Promoting Integrity in Financial Markets’ (March 2009), inter alia, made recommendations on steps needed for strengthening the international regulatory and supervisory cooperation, cross-border crisis management and conduct of regular joint Early Warning Exercises (EWEs) by IMF and FSB. The Group has recommended establishment of supervisory colleges for all major cross-border financial institutions and called on FSB and various home supervisors of major cross-border financial institutions to review and monitor the establishment of supervisory colleges for the purpose of enhanced cross-border supervisory cooperation, improvement in the information sharing arrangements between supervisors and the need for strengthening cross-border crisis management arrangements, especially during periods of financial distress. The Group has observed that bilateral Memoranda of Understanding are an important means for information sharing between banking supervisors. Therefore, taking into account the best practices in the area of bi-lateral information exchange, the Group has advised the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) to consider updating its template ‘Essential Elements of a Statement of Cooperation between Banking Supervisors’. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and Financial Stability Board (FSB) 7.30 The BCBS has taken initiatives which are proposed to address the key lessons of the crisis to strengthen the regulation, supervision and risk management of the banking sector in order to alleviate the stresses caused by the banking sector globally. The initiatives will ensure that banks move to a higher capital standard that promotes long term stability and sustainable growth without aggravating near term stress. Strengthening Minimum Regulatory Capital Framework 7.32 The Committee has issued guidelines on ‘Revisions to the Basel II market risk framework’ and ‘Guidelines for computing capital for incremental risk in the trading book’, which is expected to take effect at the end of 2010 and introduced higher capital requirements to capture the credit risk of complex trading activities. The Committee has initiated steps to strengthen the regulatory treatment for certain securitisations in Pillar 1. It has proposed to introduce higher risk weights for resecuritisation exposures (so-called CDOs of ABS) to better reflect the risk inherent in these products. Principles for Sound Stress Testing 7.33 Stress testing is a tool that supplements other risk management approaches and measures. The financial crisis has highlighted weaknesses in stress testing practices employed prior to the start of the crisis in four broad areas: (i) use of stress testing and integration in risk governance; (ii) stress testing methodologies; (iii) scenario selection; and (iv) stress testing of specific risks and products. Basel Committee in May 2009 has suggested principles for sound stress testing practices and supervision (Box VII.3). Enhancement in Supervisory Review Process 7.34 The Committee has issued supplemental guidance under Pillar 2 (the supervisory review process) of Basel II to address the flaws in risk management practices revealed by the crisis. It raises the standards for firm-wide governance and risk management, capturing the risk of off- balance sheet exposures and securitisation activities, managing risk concentrations and providing incentives for banks to better manage risk and returns over the long term. The guidance incorporates ‘Principles for Sound Compensation Practices’ issued by the Financial Stability Board in April 2009. Market Discipline 7.35 Inadequate transparency of structured products was observed to be a hindrance to effective market discipline during the crisis. There was a lack of transparency related to risk profiles and capital adequacy of the banks holding those assets. In response, the Committee has proposed enhancements to the Pillar 3 (market discipline) to strengthen disclosure requirements for securitisations, off- balance sheet exposures and trading activities. These additional disclosure requirements will help reduce market uncertainties about the strength of banks’ balance sheets related to capital market activities. Box VII.3: Principles for Sound Stress Testing Practices and Supervision Principles for Banks Use of stress testing and integration in risk governance

Stress Testing Methodology and Scenario Selection

Specific areas of focus The following recommendations to banks focus on the specific areas of risk mitigation and risk transfer that have been highlighted by the financial crisis.

Principles for Supervisors

Reference: Bank for International Settlement (2009), ‘Principles for Sound Stress Testing Practices and Supervision’, May. Strengthening Funding Liquidity Frameworks at the Bank and System-Wide Level 7.36 In response to liquidity risk management shortcomings and other lessons learnt from the financial crisis, the Basel Committee issued ‘Principles of Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision’ in September 2008. The issuance of the principles was a significant step towards setting a new global standard for what constitutes robust liquidity risk measurement, management and supervision. Under this standard, banks must maintain a sufficient buffer of highly liquid assets to withstand a range of stress events, including the loss of both secured and unsecured funding. The sound principles translate this global standard into a consistent set of supervisory expectations about the key elements of a robust framework for liquidity risk management at banking organisations. The Committee expects to finalise its proposed framework by year-end and to conduct a quantitative impact study and public consultation in 2010. Strengthening Macroprudential Regulation and Supervision/Addressing Procyclicality 7.37 BCBS has proposed to introduce macroprudential overlay that will reduce the procyclical dynamics in the banking system and address the systemic risk arising from the size and inter-connectedness of global banking institutions. Efforts are made to build buffers in good times that can be drawn in bad economic and financial conditions, thereby reducing the amplification of fluctuations in the economic cycle. The buffer capital will act countercyclical. Besides, banks should be required to raise provisions in good times. The BCBS has issued principles to assist accounting standard setters in their efforts to revise IAS 39 with an aim to promote stronger provisions based on expected losses. 7.38 FSB has come out with a Report (April 2009) on ‘Addressing procyclicality in the financial system’. FSB has observed that addressing procyclicality is an essential component of strengthening the macroprudential orientation of regulatory and supervisory frameworks. It has identified three areas as priorities for policy action, viz., the capital regime, bank provisioning practices and the interaction between valuation and leverage and it is monitoring the implementation of the recommendations. Reducing Risks from OTC Derivatives 7.39 A large number of initiatives are underway at the international level to strengthen the infrastructure for OTC derivatives, an amplifier of stress in the crisis. National supervisors and international committees have undertaken steps to mitigate the risks, focusing on efforts to move OTC derivative exposures to central counterparties and exchanges. Top priorities have been given to the implementation of Central Counterparty (CCP) clearing for Credit Default Swaps (CDS). Such CCPs have already been launched in the European Union and in the United States. The Basel Committee is reviewing the treatment of counterparty credit risk under the Basel II framework. 7.40 The Committee expects that banks and supervisors begin implementing the Pillar 2 guidance immediately. The new Pillar 1 capital requirements and Pillar 3 disclosures may be implemented not later than December 31, 2010. Taken together, these measures and enhancements to the Basel II framework will help ensure that all the following material exposures are covered in the capital adequacy framework, that they are backed by appropriate capital, that risk management and control is significantly strengthened and appropriately linked to compensation and bonuses, and that there is better disclosure of the relationship of risk and capital. Cross-border Crisis Management and Bank Resolution 7.41 The crisis has emphasised the need for supervisory attention towards cross-border contingency planning and crisis management. Accordingly, FSB has set principles for cross- border cooperation on crisis management (April 2009). Besides, the Cross-Border Bank Resolution Group (CBRG) of Basel Committee is analysing the existing bank resolution policies and legal frameworks of relevant countries in order to assess the potential impediments and possible improvements to cooperation in crisis management and the resolution of cross-border banks. The recent crisis has shown that the existing legal and regulatory frameworks / arrangements are not customised to tackle the stresses/problems in a financial group operating through multiple, separate legal entities and this may be true in case of both the cross-border and domestic financial groups. Best practices have appeared to be local in nature (ring- fencing). The Group is in the process of developing its recommendations for cross- border bank resolution regimes in order to achieve continuity in the cross-border crisis management and resolution. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also issued proposals to deal with bank insolvencies. Supervisory Structure 7.42 Following the crisis talks are on to discard supervisory framework which is build around the legal character of institutions (e.g. banks, insurance companies) - a silo approach to regulation and supervision, and to adopt regulatory and supervisory framework which is primarily based on the roles performed by various players in the stability of the system (liquidity provision, deposit-taking, and market making). 7.43 In Europe, a European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) has been created based on the recommendation of de Larosière report (February 2009). In the United States, it has been proposed that the Federal Reserve will become the future systemic supervisor. In France, the Government has decided a reform where insurance and banking supervision will be merged under the umbrella of a “systemic” college under the auspices of the Banque de France. Financial Regulation and Supervision: Initiatives under Progress 7.44 Beyond initiatives already taken, work is under progress on several initiatives to strengthen stability on several fronts as highlighted below:

5. An Assessment of the Indian Financial System 7.45 The Indian financial sector is still dominated by bank intermediation. Though the size of the capital market has expanded significantly with financial liberalisation in the early 1990s, bank intermediation remains the dominant feature. Important components of the financial sector in India are seven categories namely; commercial banks, Urban Cooperative Banks (UCBs), rural financial institutions, Non-banking Financial Companies (NBFCs), Housing Finance Companies (HFCs), Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) and the insurance sector. Commercial banks are the dominant institutions in the Indian financial landscape accounting for around 60 per cent of its total assets. Together with cooperative banks, the banking sector accounts for nearly 70 per cent of the total assets of Indian financial institutions. 7.46 Over the past decade, financial institutions in India have benefited from a stable macroeconomic environment, with sustained growth especially from 2003 onwards when India recorded one of the highest GDP growth rates, accompanied generally by an acceptable level of inflation except for the temporary spike in inflation in 2008. Financial sector reform, which has been gradual and calibrated, has helped financial institutions to weather various global financial turmoils during the past ten years. This resilience is also currently evident, as the Indian financial sector has so far not been severely affected by the financial turbulence in advanced economies. 7.47 The public sector banks continue to be a dominant part of the banking system. As on March 31, 2009, the PSBs accounted for 71.9 per cent of the aggregate assets and 75.3 per cent of the aggregate advances of the scheduled commercial banking system. A unique feature of the reform of the public sector banks was the process of their financial restructuring. The banks were recapitalised by the Government to meet prudential norms through recapitalisation bonds. All the public sector banks, which issued shares to private shareholders, have been listed on the exchanges and are subject to the same disclosure and market discipline standards as other listed entities. To address the problem of distressed assets, a mechanism has been developed to allow sale of these assets to Asset Reconstruction Companies which operate as independent commercial entities. 7.48 Financial institutions have transited since the mid-1990s from an environment of an administered regime to a system dominated by market determined interest and exchange rates, and migration of the central bank from direct and quantitative to price-based instruments of monetary policy and operations. However, increased globalisation has resulted in further expansion and sophistication of the financial sector, which has posed new challenges to regulation and supervision, particularly of the banking system. In this context, the capabilities of the existing regulatory and supervisory structures also need to be assessed by benchmarking them against the best international practices. 7.49 The financial sector reforms in the country were initiated in the beginning of the 1990s. The financial sector reforms were undertaken early in the reform cycle, which have brought about a sea change in the profile of the banking sector. Notably, the reforms process was not driven by any banking crisis, nor was it the outcome of any external support package. Besides, the design of the reforms was crafted through domestic expertise, taking on board the international experiences in this respect. The reforms were carefully sequenced with respect to the instruments to be used and the objectives to be achieved. Thus, prudential norms and supervisory strengthening were introduced early in the reform cycle, followed by interest-rate deregulation and a gradual lowering of statutory pre-emptions. The more complex aspects of legal and accounting measures were ushered in subsequently when the basic tenets of the reforms were already in place. 7.50 As regards the prudential regulatory framework for the banking system, a long way has been traversed from the administered interest rate regime to deregulated interest rates, from the system of Health Codes for an eight-fold judgmental loan classification to the prudential asset classification based on objective criteria, from the concept of simple statutory minimum capital and capital-deposit ratio to the risk-sensitive capital adequacy norms – initially under Basel I framework and now under the Basel II regime. There is much greater focus now on improving the corporate governance set up through ‘fit and proper’ criteria, on encouraging integrated risk management systems in the banks and on promoting market discipline through more transparent disclosure standards. The policy endeavour has all along been to benchmark India’s regulatory norms with the international best practices, of course, keeping in view the domestic imperatives and the country context. The consultative approach of the RBI in formulating the prudential regulations has been the hallmark of the current regulatory regime which enables taking account of a wide diversity of views on the issues at hand. The implementation of reforms has had an all round salutary impact on the financial health of the banking system, as evidenced by the significant improvements in a number of prudential parameters, like capital adequacy ratio, asset quality profitability, Return on Assets (RoA) and productivity of banks. Commercial Banks 7.51 Several balance sheet and profitability indicators suggest that the Indian banking sector now compares well with the global benchmarks. The Indian banking system has been assessed in international perspective by comparing various financial and soundness indicators such as return on total assets, non-performing loans ratio and capital levels (Table VII.1 and Table II.7 for data for more years; and analysis in para. 2.38). 7.52 One of the most widely used indicators of profitability is RoA, which indicates the commercial soundness of the banking system. RoA of Indian scheduled commercial banks was at 1.0 per cent at end-March 2008 (1.02 per cent at end-March 2009), which is line with the international standards. The RoA in several advanced countries and some emerging market economies were less than one per cent.

7.53 Quality of assets of banks as reflected in the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to total advances is an important banking soundness indicator from the financial stability perspective. A low level of NPL ratio not only reflects the prudent business strategy followed by the banking system, but is also indicative of the conducive recovery climate and the legal framework for recovery of loans. Banks with adequate credit risk management practices are expected to have lower non-performing loans. In India, several measures taken by the Government and the Reserve Bank have enabled SCBs to substantially reduce their level of NPLs from 15.7 per cent at end-March 1997 to about 11 per cent at end- March 2001. The NPL ratio has remained unchanged at 2.3 per cent between 2008 and 2009. The ratio of provisioning to NPLs reflects the ability of a bank to withstand losses in asset value. A low ratio of provisioning to NPLs makes the banking system vulnerable to shocks. The provisioning to NPL ratio of Indian banks was 52.6 per cent at the end-March 2008. It was fairly comparable with the ratio of provisioning across most advanced countries. 7.54 Bank capital acts as the ultimate buffer against losses that a bank may suffer. The minimum capital to risk-weighted asset ratio (CRAR) has been specified at 8 per cent by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) under both the Basel I and Basel II frameworks. In the Indian context, the overall capital adequacy of the SCBs at 13.2 per cent as at end-March 2009, was well above the Basel norm of 8 per cent and the stipulated norm of 9 per cent for banks in India. As at end-March 2009, the CRAR of 78 banks was over 10 per cent, while that of only one bank was between 9 and 10 per cent. The CRAR of Indian banks was comparable with most emerging markets and developed economies. The global range of CRAR in 2008 varied between 10.0 per cent and 28.7 per cent. A capital to asset ratio is another simple measure of soundness of a bank. The lower the ratio, the higher is the leverage and greater vulnerability of a bank. Globally, the ratio varied between 3.5 per cent to 22.7 per cent in 2008, while Indian banks’ (Tier I) capital to assets ratio at 6.3 per cent suggested a lower degree of leverage and higher stability. Non-Bank Financial Institutions 7.55 Although banks dominate the Indian financial spectrum, NBFCs play an important role in financial markets. With their unique strengths, the stronger NBFCs could complement banks as innovators and partners. The core strength of NBFCs lies in their strong customer relationships, good understanding of regional dynamics, service orientation and ability to reach out to customers who would otherwise be ignored by the banks, which makes such entities effective conduits of financial inclusion. 7.56 The recent global financial turmoil has highlighted the impact on systemic stability through OFIs which, in India, operate as NBFCs. In India, there are two broad categories of NBFCs, viz., NBFCs-D and NBFCs-ND. The recent growth in the NBFC sector is due primarily to NBFCs–ND. The financial indicators of the NBFCs-D segment, do not throw up any major concern and is characterised by high CRAR, low NPAs and comfortable RoA. Systemically important NBFCs-ND (NBFCs-ND-SI) are growing at a rapid pace. The sector has been witnessing a significant improvement in financial health and is characterised by low and reducing NPAs and high RoA. 7.57 The Reserve Bank, on a review of the experience with the regulatory framework for non-banking financial companies in place since April 2007, enhanced the capital adequacy requirement for NBFCs-ND-SI and put in place guidelines for liquidity management and reporting, with specified norms for disclosures in October 2008. The implementation of capital to risk weighted asset ratio (CRAR) of 12 per cent by March 31, 2009 and 15 per cent by March 31, 2010 for these NBFCs was, however, deferred by one year, respectively, in view of the difficulty in raising equity capital in a market, which was depressed in the second half of the year in line with the sharp downward correction in asset prices globally. Taking into consideration the need for adequate access to funds for meeting business and regulatory requirements, NBFCs-ND-SI were permitted to issue perpetual debt instruments. To address problems of liquidity and ALM mismatch in the current economic scenario, the Reserve Bank permitted NBFCs-ND-SI to raise short term foreign currency borrowings under the approval route as a temporary measure, subject to certain conditions and also provided liquidity support to eligible NBFCs-ND-SI through a special purpose vehicle (SPV). 7.58 The sector’s recourse to short term funds for funding their asset base is, however, a cause for concern. Borrowings accounts for about two-thirds of their funding requirements. The CFSA, 2009 has stated that given the funding requirements of NBFCs and their lack of access to low-cost deposits, there is a need to develop an active corporate bond market which could act as an alternate funding source. Board for Financial Supervision (BFS): Initiatives 7.59 The Board for Financial Supervision (BFS), constituted in November 1994, has been mandated to ensure integrated oversight over the financial institutions that are under the purview of the Reserve Bank and remains the principal guiding force behind the Reserve Bank’s supervisory and regulatory initiatives. 7.60 The BFS reviews the inspection findings in respect of commercial banks/UCBs as also periodic reports on critical areas of functioning of banks such as reconciliation of accounts, fraud monitoring, overseas operations and banks under monthly monitoring. In addition, the BFS also reviews the micro and macro prudential indicators, banking outlook and interest rate sensitivity analysis. It also issues a number of directions with a view to strengthening the overall functioning of individual banks and the banking system. The BFS held eight meetings during the period July 2008 to June 2009. In these meetings, it considered, inter alia, the performance and the financial position of banks and financial institutions during 2008-09. It reviewed 70 inspection reports (27 of public sector banks, 16 of private sector banks, 20 of foreign banks, 4 of local area banks and 3 of financial institutions). Some of the important issues deliberated upon by the BFS during 2008-09 are highlighted below :

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment, 2009 7.62 On the whole, the CFSA found that the Indian financial system was essentially sound and resilient and that systemic stability was by and large robust. India was broadly compliant with most of the standards and codes, though gaps were noted in the timely implementation of bankruptcy proceedings. The CFSA also carried out single-factor stress tests for credit and market risks, liquidity ratio and scenario analyses. These tests showed that there were no significant vulnerabilities in the banking system. Though NPAs could rise during the current economic slowdown, given the strength of the banks’ balance sheets, the rise was not likely to pose any systemic risk. 7.63 The assessment made by the CFSA, 2009 in respect of banking sector in India is as follows: (i) Commercial banks have shown a healthy growth rate and an improvement in performance as is evident from capital adequacy, asset quality, earnings and efficiency indicators. In spite of some reversals during the financial year 2008-09 (up to September 2008), the key financial indicators of the banking system do not throw up any major concern or vulnerability and the system remains resilient. (ii) The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index for India (which was at 536 in 2008) indicates that the Indian banking sector is ‘loosely concentrated’. A cross country comparison of the concentration index shows that India’s position is comparable with those of the advanced economies, but shows a lower concentration than other emerging market economies. (iii) The implementation of reforms has had an all round salutary impact on the financial health of the banking system, as evidenced by the significant improvements in a number of prudential parameters, like capital adequacy ratio, asset quality profitability, return on assets (RoA) and productivity of banks. Further, the Z-score (a higher Z-score implies a lower probability of insolvency risk and in this model, risk is summarised as the number of standard deviations an institution’s earnings must drop below its expected value before equity capital is depleted) of commercial banks increased from 10.2 for period 1997-2006 to 13.2 for period 1999-2008 – an indication of increasing solvency. The level of capital ratio in the Indian banking system compares quite well with the banking system in many other countries – though the capital adequacy of some of the banks in the developed countries has remained under considerable strain in the recent past in the aftermath of the sub-prime crisis. (iv) One area of concern has been that off-balance sheet (OBS) exposure has increased significantly in recent years, particularly in the case of foreign banks and new private sector banks. The notional principal amount of OBS exposure increased from Rs.8,42,000 crore at end-March 2002 to Rs.1,49,69,000 crore at end-March 20084. The ratio of OBS exposure to total assets increased from 57 per cent at end-March 2002 to 204 per cent at end-March 2009. The spurt in OBS exposure is mainly on account of derivatives whose share averaged around 80 per cent. The derivatives portfolio has also undergone change with single currency IRS comprising 57 per cent of total portfolio at end- March 2008 from less than 15 per cent at end-March 2002. The exposure in the case of PSBs has shown an increase subsequent to the amendment in the SC(R) Act in 2003 allowing Over-The-Counter (OTC) transactions in interest rate derivatives. The stress testing carried out by CFSA is provided in Box VII.4. 7.64 Way forward, there is a need to undertake multi-factor stress testing as a tool for supplementing other risk management approaches. In addition, the sound principles of stress testing as recommended by BIS would need to be implemented (Box VII.3). 7.65 Among two areas of concern first is that there has been an increase in the dependence on bulk deposits to fund credit growth. This could have liquidity and profitability implications. An increase in growth in housing loans, real estate exposure as also infrastructure has resulted in elongation of the maturity profile of bank assets. Secondly, mark to market (MTM) losses for the banking system arising out of falling asset prices in the international markets exerted severe stress on the balance sheets of many international banks, on account of their significant exposure to such assets. Large off-balance sheet exposures magnified their stress levels further. In this context, it was felt necessary by the Reserve Bank to keep track of the quality of exposures of overseas operations of Indian banks for timely action and supervisory intervention, if required. Consequently, the Reserve Bank held discussions with select major banks with overseas operations to assess the quality of their overseas exposures. The assessment revealed that the banks did not have any direct exposure to the US sub-prime market. Some banks, however, had indirect exposure through their overseas branches and subsidiaries to the US sub-prime markets in the form of structured products, such as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) and other investments. Some of the banks, with exposures to credit derivatives, had to book MTM losses on account of widening of credit default swap (CDS) spreads. The assessment, however, showed that such exposures were not very significant, and banks had made adequate provisions to meet the MTM losses on such exposures. Besides, the banks also maintained high levels of capital adequacy ratio. The Reserve Bank’s assessment suggested that, the risks to the banking sector associated with MTM losses, appeared to be limited and manageable. Accordingly, a monthly reporting system was introduced in September 2007 capturing Indian banks’ overseas exposure to credit derivatives and investments such as Asset Backed Commercial Papers (ABCP) and Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS). An analysis of the information so collected reveals that the exposures of Indian banks through their overseas branches in credit derivatives and other investments are gradually coming down from the June 2008 level. Their MTM losses, however, gradually increased up to March 2009, reflecting the impact of the sustained fall in the value of the assets in their portfolios. Box VII.4: Stress Testing by CFSA, 2009 As is well-known, the resilience of the financial system can be tested by subjecting the system to stress scenarios. Such tests are generally carried out with reference to a sudden shock and its instantaneous impact; in practice, when such shocks take place, banks get time to adapt and mitigate the impact. The CFSA, 2009 carried out single-factor stress tests for the commercial banking sector covering credit risk, market/interest rate risk and liquidity risk. They have revealed that the banking system can withstand significant shocks arising from large potential changes in credit quality, interest rate and liquidity conditions. These stress tests for credit, market and liquidity risk show that Indian banks are generally resilient.