Rajmal*

This paper provides a phase-wise analytical review of the

fiscal situation of the Indian major States over the previous two and half decades

and examines the effectiveness of the policy measures to strengthen the State

finances. The analysis reveals that the States’ fiscal position showed imbalances,

albeit in a varied degree, since the mid-1980s which deepened in the

second half of the 1990s. The effectiveness of policy measures has remained largely

inadequate. Most of the Policy measures were exigency-driven rather than being

structured. As the States face large resource gap, they require effective and

time-bound policy measures to enhance revenues particularly non-taxes and shift

in expenditure pattern towards economic infrastructure and social sectors to facilitate

acceleration in growth.

JEL Classification : H71, H72,

H74

Key Words : State Taxation,

State Budget, State Borrowing

Introduction

In the Indian federal set up, the States play an important role in accelerating

and sustaining growth. The Indian Constitution assigns important responsibilities

to States in many sectors such as agricultural development, infrastructure, poverty

alleviation, water supply and irrigation, public order, public health and sanitation.

Furthermore, they have concurrent jurisdiction in several areas like education,

electricity, economic and social planning and family planning. In view of the

larger responsibilities assigned to the States, their expenditure accounts for

a substantial portion of the Government sector expenditure (Centre plus

States) in India. The comparative position across countries reveals that in India

the share of aggregate States’ expenditure in Government sector expenditure

is higher than that in several other countries such as Australia, Denmark, Argentina,

USA and Germany (World Bank, 2005). The composition of receipts and expenditure

of the Government sector in India reveals that while the State Governments collect

about one-third of the total Government sector receipts, they incur more than

three-fourth of the total expenditure on social services and more than half of

the total expenditure on economic services. The States’ ability to undertake

and perform the developmental functions adequately and effectively is critically

determined by their fiscal position.

A State specific assessment of fiscal

position assumes importance in view of the wide disparities that exist among the

Indian States and their increasing role in the development.The policy measures

and prescriptions which are suggested for aggregate State finances may not be

appropriate and effective for drawing out strategies for an individual State.

It is worth noting as stated in the Economic Survey, (2004-05), Government

of India, “Though the fiscal deterioration of States began much later

than that of the Centre, the fiscal stress of some of the State Governments is

more acute and an important constraint in their development.” The

analysis of State finances in historical perspective since the mid 1980s reveals:

(i) steady deterioration in revenue receipts-GSDP ratio, (ii) stagnating social

sector expenditure, (iii) inadequate investment for basic infrastructure sectors,

(iv) pre-emption of high cost borrowed funds for financing current expenditure,

(v) large and persistent resource gap, and (vi) accumulation of high debt stock

and debt service payments.

Many States undertook various policy measures

to strengthen their finances mainly in the late 1990s. Given the size of the problem,

the effectiveness of such policy measures, however, remained largely inadequate.

Most of the policy measures were ad hoc in natureand were guided by the

exigency rather than being structured. Against the above background, the

paper provides an analytical review of fiscal situation at State level during

the previous two and a half decades. The paper examines the policy measures undertaken

and their effectiveness to improve the State finances.The entire period under

review is divided into four phases based on the emerging fiscal developments.

The structure of the remaining paper is as follows. Section I provides an analytical

framework to study the public finance at State level. Section II presents an analytical

review and assessment of fiscal situation at State level. Section III sets out

the review of policy measures. The details of effectiveness of the policy measures

are provided in Section IV. The concluding observations are outlined in Section

V. Section I

Analytical

Framework In a federal system, the sub-national

governments are assigned certain sources of revenues and expenditure responsibilities.

In the Indian context, the State Governments have their own independent sources

of revenue as well as transfers from the Central Government. Accordingly, the

level of resource flow at State level in India is determined by both (i) endogenous

factors (i.e., States’ own efforts in generating resources) and

(ii) exogenous factors (i.e., the resource transfers from the Central

Government). The details of various sources of revenues and expenditure responsibilities

of State Governments are set out below.

Sources of Revenues

States’ own Revenues

(i) States’

own tax revenues: States’ own taxes can be grouped into three

parts, viz., (i) taxes on commodities and services such as sales tax,

State excise, taxes on vehicles and taxes on goods and passengers, (ii) taxes

on property and capital transactions such as stamps and registrations and land

revenue, and (iii) taxes on income such as profession, trade and agricultural

income. Among the above, the principal sources of States’ tax revenue are

sales tax, State excise and stamps and registration fees. Sales tax alone accounts

for nearly two-thirds of the total States’ own tax revenue. Realising the

need for tax reforms, many States have switched over to a Value Added Tax (VAT)

regime on the basis of the recommendations of the Empowered Committee of State

Finance Ministers with effect from April 1, 2005. VAT may be defined as a tax

on the value added at each stage of production and distribution of a commodity.

(ii) States’ own non-tax revenues: These include

(i) interest receipts, (ii) dividend and profits,(iii) user charges on account

of social and economic services, and (iv) general services which mainly include

State lotteries. The major part of revenues comes from interest receipts, State

lotteries and user charges on account of economic services.

Current

Transfers and Devolution from the Centre

The current transfers

and devolution from the Centre include States’ share in the Central taxes

and grants. The provision for these transfers to States aims at addressing the

vertical imbalance or fiscal gap that stems from asymmetric devolution of functions

and tax powers among different Government levels. Furthermore, such transfers

aim to secure fiscal equalisation among the States which is necessary and imperative

in the interest of equity and efficiency.

Expenditure Responsibilities

of States

State Governments incur considerable expenditure

towards provision of various social and economic services in addition to expenditure

requirements towards maintenance of various organs and general administration.

The total expenditure comprises of revenue and capital components. Broadly the

expenditure which does not result in creation of assets is treated as revenue

expenditure. Capital expenditure mainly includes expenditure on acquisition of

assets like land, building, machinery etc. and also loans and advances

by States mainly to Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs). Under revenue expenditure,

certain items of expenditure, viz., interest payments, pensions outgo,

wages and salaries and expenses towards administrative services have downward

rigidity.

Financing Pattern of Gross Fiscal Deficit (GFD)

The analysis of the State Government finances during previous two and half

decades reveals that invariably almost all the States incur more expenditure than

the revenues they mobilise. Consequently, the States undertake borrowings from

a number of sources to finance their resource gap/GFD. The financing pattern of

resource gap indicates that, historically, loans from the Centre have been the

most important source of borrowings for the States. However, with the changes

in accounting system in respect of small savings since April 1, 1999 and operationalisation

of Debt Swap Scheme (during 2002-03 to 2004-05), the share of this source in financing

GFD has declined significantly. The small saving receipts [(i.e., Special

Securities issued to National Small Saving Fund (NSSF)] are emerging a major source

to finance the resource gap – constituting over two third of GFD in the

recent period (RBI, 2005). The other major sources of financing available to the

States include: (i) market borrowings, (ii) loans from banks and financial institutions

(FIs) and (iii) public account borrowings.

Scheme of Presentation

of States’ Fiscal Analysis

Taking into account the fiscal

developments on both front, viz., (i) endogenous factors (within States’

control) and (ii) exogenous factors (States’ dependence on Central transfers),

the period under review has been divided into four phases.

(i)

Revenue Account in Surplus Position: This phase covers the period

1980-81 to 1985-86. The buoyant growth in States taxes particularly sales tax

led to the higher growth in revenues than the expenditure - resulting in surplus

in the Revenue Account.

(ii) Emergence of Fiscal Imbalances:

This phase deals with the period 1986-87 to 1997-98. The growth in revenues

remained sluggish on account of low/negligible user charges and dividends and

profits coupled with stagnation in States’ share in Central taxes. The liberalisation

of trade and investment policies providing various incentives and concessions

to attract private investment impacted the States’ finances.

(iii)

Deepening and Persistent Fiscal Imbalances1: This phase pertains

to the period 1998-99 to 2003-04. The major reasons behind the worsening of fiscal

imbalances were the significant increase in revenue expenditure due to Fifth Pay

Commission award and growing interest payments on the past high cost borrowed

funds. The growth in revenues remained sluggish due to stagnation in States’

tax-GSDP ratio and decline in States’ own non-taxes and Central transfers,

particularly, grants to States. (iv) Recent

Fiscal Developments and Challenges Ahead: This

phase takes into account the period since 2004-05 onwards.

Implementation

of VAT with effect from April 1, 2005, recommendations of Twelfth Finance Commission

(TFC) for the period 2005-10 and the States’ continued emphasis on the on-going

fiscal reforms with statutory backing such as fiscal responsibility legislations

(FRLs) which got further boost on account of TFC’s recommendations are the

major recent developments. The fiscal position of States would be largely influenced

in the medium term by these developments. This phase also highlights the major

challenges for the States in the medium term. The details of major fiscal

indicators to examine the fiscal situation of States include: (i) trends in revenue

receipts, States’ own revenues and share in the Central taxes and grants,

(ii) pattern and trends in major components of expenditure, (iii) available resources

for financing resource gap, and (iv) movement in major deficits and debt stocks2.

Section II

Finances of

Major States: Analytical Review and Assessment3

An Overview

A quick overview of the fiscal position of major States reveals that they were

generating surpluses in their revenue account in the first phase. The fiscal position

of States, however, had started to show signs of stress in the second phase and

fiscal imbalances deepened and persisted during the third phase. The factors responsible

for the widening fiscal inbalances include: (i) growing interest burden, (ii)

increasing wages and salaries (iii) pension liabilities, (iv) losses incurred

by State Public Sector Undertakings, (v) inadequate user charges/cost recoveries

and (vi) deceleration in the Central transfers (RBI, 2004). In the recent years,

interest payments alone constitutes over one-fourth of the revenue expenditure

and absorbs between 30-50 per cent of revenue receipts in many States (West Bengal,

Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh). Notably, during 2002-03 to

2003-04, interest payments and pensions outgo taken together absorbed as high

as around 70 per cent of revenue receipts in case of West Bengal and nearly 50

per cent of revenue receipts in Kerala.

The fiscal stress experienced

by the States has seriously constrained their ability to discharge major responsibility

of developing social and economic infrastructure. The expenditure for developmental

activities, which are directly related to growth, has suffered. On the other hand,

expenditure on non-developmental purposes, largely committed in nature, has witnessed

a steady rise. The problem was exacerbated by low productivity of capital expenditure.

The proliferation of projects spread the resources thinly and inadequate financial

allocations cause severe cost and time over runs (Rao, 2002).

The Planning

Commission, while stressing the need for fiscal and other reforms at the State

level, observed that “… a joint effort by the Centre and States

is needed to fulfill the Tenth Plan objectives. Along with the Centre, States

need to reform more and much faster, and raise substantially higher levels of

their own resources to mobilise the financial resources essential for the much

needed productive investments. ..” (Mid Term Appraisal, Tenth

Five Year Plan).

Phase-wise Analysis of State Finances:

Major Features

The analytical framework developed in section

I has been used to analyse the fiscal position of States. The major features of

each phase are set out below. Phase 1: Revenue Account in Surplus

Position

All the major States except West Bengal4 were

generating surplus in the Revenue Account. The major features of this phase include:

(i) growth in revenue receipts was mainly led by States own taxes particularly,

sales tax, (ii) the revenue expenditure of major States in terms of GSDP, on an

average remained at 12.8 per cent, (iii) the revenue receipts of States were placed

at 13.2 per cent of GSDP thus leaving surplus of 0.4 per cent of GSDP under revenue

account, and (iv) GFD-GSDP ratios in case of all the States except Punjab and

Orissa was below 4 per cent.

Phase 2: Emergence of Fiscal

Imbalances

The major highlights of this phase are: (i)

Revenue Account of the States turned into deficit from surplus, (ii) the deceleration

in the States’ own non-tax revenues coupled with stagnation in States’

share in Central taxes resulted in sluggish growth in the revenue receipts, (iii)

revenue expenditure in terms of GSDP, on an average, increased by more than two

percentage points, (iv) the revenue receipts-GSDP ratio increased less than one

percentage point in this phase over the previous phase, (v) many States started

utilising the high cost borrowed funds to finance the current expenditure, (vi)

total expenditure-GSDP ratio increased marginally over the first phase - reflecting

the impact of cutback of capital expenditure which declined to 3.8 per cent from

5.6 per cent of GSDP in the previous phase, (vii) the liberalisation of trade

and investment policies in the economy impacted State finances as they provided

various incentives and concessions to attract private investment, and (viii) the

increasing share of the services in States’ GSDP, which were not covered

under the tax net, also affected adversely their fiscal health.

Phase 3: Deepening and Persistent Fiscal Imbalances

The major features include: (i) the increasing fiscal imbalances in the

previous phase had started deepening and persisted, (ii) revenue receipts-GSDP

ratio decelerated by 0.8 per cent while revenue expenditure-GSDP ratio increased

by around 2 percentage points over the previous phase, (iii) deceleration in revenue

receipts was due to decline in States own non-tax revenues, which reflected low/negligible

user charges, dividends and profits, and central grants, (v) revenue expenditure

grew significantly mainly due to increase in salaries and wages bill on account

of the Fifth Pay Commission recommendations coupled with high interest payments

on past loans and pensions outgo, (vi) interest payments and pension outgo of

major States absorbed as high as 37 per cent of revenue receipts (varying from

26 per cent in Madhya Pradesh to 58 per cent in West Bengal) as against 21 per

cent in the previous phase (varying from 15 per cent in Maharashtra to 28 per

cent in Kerala), (vii) total expenditure-GSDP ratio increased to around 21 per

cent due to significant increase in revenue expenditure, (viii) a sharp increase

in revenue expenditure accompanied by inadequate growth in revenues constrained

the States ability for releasing adequate resources for capital expenditure which

remained almost stagnated at the level of the previous phase (3.8 per cent of

GSDP), (ix) the large and persistent resource gap resulted in a vicious cycle

of deficit, debt and debt service payments.

Phase 4: Recent

Fiscal Developments and Challenges Ahead

The recent major

fiscal development, viz., implementation of VAT, TFCs recommendations

and States’ FRLs, are expected to largely impact the State finances in the

medium term. There are some signs of improvement in the State finances as reflected

in their recent budgets. However, given the past track record of weak fiscal marksmanship

of State Governments, the high level of fiscal corrections appears to be difficult

to achieve in a short span of time. For a durable fiscal discipline and realistic

fiscal correction path, States would have to place continuous emphasis on timely

and effective measures towards on both revenue enhancement and expenditure reprioritisation.

In this regard, the fiscal correction path as spelt out by the TFC provides a

new direction and motivatation to the States to undertake the appropriate policy

measures.

TFC’s Impact on State Finances

The TFC’s recommendations for fiscal consolidation in the States will

have far-reaching implications for the federal-state fiscal relationship. The

States’ fiscal imbalances are likely to ease on account of higher tax devolution,

enhanced grants as well as the debt relief schemes by the TFC. The critical aspect

of the recommendations of the TFC is the linking of certain resource transfers

to enhance the fiscal prudence on the part of the States, in general, and the

enactment of FRLs by the States, in particular. The increase in transfers

recommended through tax devolution and grants are expected to facilitate the States

to undertake fiscal correction even while undertaking social and infrastructure

expenditure required to move on an accelerated growth path.

A New Borrowing Regime for States

Following the TFC’s

recommendations that the Centre should not act as an intermediary for future lending

and allow the State Governments to approach the market directly, a new borrowing

regime for the States was put in place5 . Accordingly, in the Union Budget 2005-06,

there was no provision made for Central loans for State Plan Schemes. The Union

Budget indicated an amount of Rs.29,003 crore which was to be raised by the States

and Union Territories with Legislature directly from the market. Furthermore,

as per the TFC’s recommendations (also accepted by the Government of India),

external assistance would be transferred to the States on the same terms and conditions

as attached to such conditions by external funding agencies (making Centre a financial

intermediary - without any gain or loss). The States would get the same maturity,

moratorium and amortisation schedule as the Centre gets from the external lender.

The past experience of some States reveals that the weaknesses in their

finances invited adverse reaction from the financial markets as manifested in

the widening spread on State Government securities and under-subscription to market

loans. The under-subscription to the State market loans also brings to the fore

various factors that impact State Governments liquidity. These factors include:

(i) the fiscal health of the State Governments, (ii) the credibility of their

prospective policy actions and, (iii) transparency of their budgets (RBI, 2004). In

view of the new borrowings regime, States would need to improve the market perception

about their fiscal position by exhibiting adequate will and action for fiscal

rectitude by actively considering the fiscal reforms measures. The better fiscal

performing States would get the benefit relatively more than the fiscally weak

States from the market. Challenges Ahead In

the process of fiscal correction in the medium term, the allocation of adequate

resources towards productive sectors, which is essential to accelerate the growth

and to increase the revenues particularly through non-taxes by increasing user

charges, cost recovery, dividends and profits, etc., would be major challenges

for the States.

The large repayment of market borrowings (from Rs.

6,274 crore in 2005-06 to increase two-fold by 2007-08, three-fold by 2010-11

and nearly six times by 2014-15) would have a bearing on the fiscal health of

the States (RBI, 2005).

Furthermore, the impact of the Sixth Pay

Commission on fiscal health, if followed by the State Governments, also needs

to be taken into account6. Although the Pay Commission, is meant to cover only

the Central Government employees, its recommendations, as the past experience

reveals, are generally adopted by the State Governments as well. The Commision

is expected to submit the report within eighteen months from the date of its constitution.

A State-wise Analysis

A State-wise analytical

review of the fiscal position based on select fiscal indicators is set out below.

Trends in Major Deficits and Financing pattern

Revenue Deficit

The degree of deterioration

in the revenue account varied significantly across the States (Chart 1 and Exhibit

1). States like Orissa and West Bengal showed substantial increase in their revenue

deficit-GSDP ratio in the third phase as compared to the

second

phase. The deterioration in the revenue account led to significant increase in

the overall resource gap.

Revenue Deficit Accounts for

Sizeable Portion of GFD

The revenue deficit of State Governments

such as West Bengal, Punjab, Kerala and Uttar Pradesh showed substantial increase

and accounted for over 70 per cent of GFD in the third phase. The significant

deterioration in Revenue Account of States led them to

Exhibit

1 : States’ Revenue Surplus/Deficit-GSDP Ratio:

A Comparative

Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : 1980-86

(Revenue Surplus) | Above

1 | Haryana, Madhya Pradesh |

0.5 to 1 | Uttar

Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu | Below

0.5 | Kerala, Orissa, Maharashtra, Andhra

Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, West Bengal * |

* : During the first phase, West Bengal

revenue account was in surplus only in 1985-86. |

Phase 2: 1986-98

(Revenue Deficit) | Above

1.5 | Punjab, Kerala, Uttar Pradesh, West

Bengal | 0.5 to

1.5 | Orissa, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Rajasthan,

Bihar, Andhra Pradesh | below

0.5 | Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh,

Karnataka | Phase

3 : 1998-2004 (Revenue Deficit) | Above

4 | West Bengal, Orissa, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh,

Kerala, Rajasthan | 2.5

to 4.0 | Gujarat, Bihar, Maharashtra, Madhya

Pradesh, Tamil Nadu | Below

2.5 | Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana |

Exhibit

2 : States’ Revenue Surplus/Deficit-GFD Ratio:

A Comparative

Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : Revenue

Surplus/ GFD Ratio | Above

40 | Madhya Pradesh, Haryana |

20 to 35 | Tamil

Nadu, Karnataka, Gujarat, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, West Bengal * |

Below 20 | Kerala,

Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Orissa |

* : During the first

phase, West Bengal revenue account was in surplus only in 1985-86. |

Phase

2 : Revenue Deficit/GFD Ratio | Above

40 | Kerala, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu |

20-40 | Andhra

Pradesh, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab | below

20 | Karnataka, Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya

Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Bihar | Phase

3 : Revenue Deficit/GFD Ratio | Above

70 | Kerala, Punjab, West Bengal, Uttar

Pradesh | 60 to

70 | Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Rajasthan,

Maharashtra | Below

60 | Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Karnataka, Haryana,

Andhra Pradesh | use a substantial portion of the

borrowed funds to finance their current expenditure in the third phase (Exhibit

2).

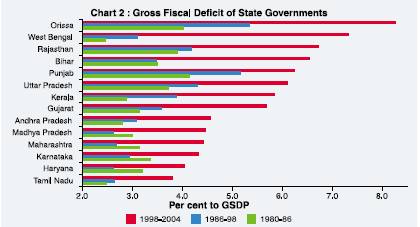

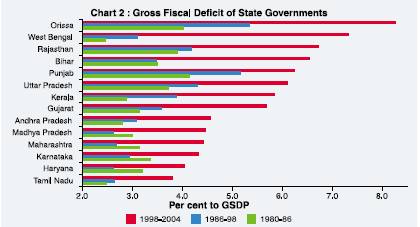

GFD of State Governments

The

substantial increase in GFD was evident in case of many States such as Orissa,

West Bengal, Rajasthan, Bihar, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh (Chart 2 and Exhibit 3). Financing

Pattern of GFD State Governments access funds

from a number of sources to finance their resource gap viz., (i) loans

from the Centre, (ii) market borrowings, (iii) loans from banks and financial

institutions (FIs) (such as SBI and other banks, NABARD, LIC, GIC) and (iv) Public

Account Borrowings (PAB) (such as State provident funds, reserve funds and deposits

and advances). To meet the temporary mismatches in receipts and expenditure, the

States also avail ways and means advances from the Reserve Bank of India. A quick

analysis of the

borrowed funds by the States reveals that during the 1990s loans

from the Centre was a dominant source of financing States’ deficit followed

by State Provident Funds and other PAB, market loans and banks and FIs.

The States dependence on the Centre to finance their deficit, however, showed

significant decline due to introduction of NSSF

Exhibit

3 : States’ GFD-GSDP Ratio: A Comparative Position |

Per cent | Phase

1 : 1980-86 | Above

3.5 | Punjab, Orissa, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar | 3.0-3.5 | Karnataka,

Haryana, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh |

Below 3.0 | Kerala,

Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal | Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

4 | Orissa, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan |

3.5- 4.0 | Kerala,

Gujarat, Bihar | Below

3.5 | West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka,

Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, | | Haryana,

Madhya Pradesh | Phase

3 : 1998-2004 | Above

6 | Orissa, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Bihar,

Punjab, Uttar Pradesh | 4.5

to 6.0 | Kerala, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh,

Madhya Pradesh | Below

4.5 | Maharashtra, Karnataka, Haryana, Tamil

Nadu |

Exhibit

4 : Financing Pattern of GFD of States: |

A Comparative

Position | (Per

cent to GFD) | State

| Phase

2 : 1986-1998 | Phase

3 : 1998-2004 | | CL | MB | OT

* | CL | MB | NSSF

# | OT * |

Andhra Pradesh | 51 | 23 | 26 | 24 | 31 | 26 | 19 |

Bihar | 65 | 34 | 1 | 24 | 19 | 41 | 16 |

Gujarat | 57 | 10 | 33 | 16 | 24 | 61 | -1 |

Haryana | 50 | 15 | 35 | 10 | 21 | 51 | 18 |

Karnataka | 46 | 16 | 38 | 21 | 27 | 34 | 18 |

Kerala | 33 | 23 | 44 | 8 | 21 | 18 | 53 |

Madhya Pradesh | 40 | 17 | 43 | 18 | 25 | 34 | 23 |

Maharashtra | 52 | 8 | 40 | 9 | 14 | 42 | 35 |

Orissa | 38 | 25 | 37 | 23 | 28 | 18 | 31 |

Punjab | 76 | 7 | 17 | 1 | 18 | 54 | 27 |

Rajasthan | 39 | 19 | 42 | 12 | 26 | 48 | 14 |

Tamil Nadu | 49 | 21 | 30 | 9 | 24 | 35 | 32 |

Uttar Pradesh | 50 | 17 | 33 | 10 | 24 | 40 | 26 |

West Bengal | 60 | 18 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 56 | 11 |

CL : Central Loans,

MB: Market Borrowings, OT : Others, \

NSSF : Loans from National Small Saving

Fund.

* : Includes negotiated loans from Banks and FIs and public account

borrowings. # : Came into existence on April 1, 1999. |

since April 1, 1999. During 2002-05, States have made substantial repayment of

Central Loans under Debt Swap Scheme. Consequently, the share of Central loans

in financing the States’ GFD has declined significantly while the share

of market loans, small savings and other loans has increased. In the recent years,

a number of States have financed over 50 per cent of their GFD through loans from

NSSF (Exhibit 4).

Revenue Performance of States

Revenue receipts showed sluggish growth in case of many States in the third

phases. Inadequate growth in revenue receipts was due to near stagnation in States’

tax-GSDP ratio with no perceptible change in the contribution of States’

non-tax revenue to GSDP and deceleration in resource transfers from the Centre

to the States. Revenue receipts-GSDP ratio was above 15 per cent in case of five

States during the second phase, however, in the third phase only two States could

manage their revenue-GSDP ratio at this level (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit

5 : States’ Revenue Receipts-GSDP Ratio:

A Comparative

Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : 1980-86 |

Above 14 | Andhra

Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Orissa | 13

to 14 | Kerala, Rajasthan, Bihar, Madhya

Pradesh, Maharashtra, Haryana | Below

13 | Gujarat, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, West

Bengal | Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

15 | Orissa, Bihar, Haryana, Karnataka,

Rajasthan | 14 to

15 | Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu |

Below 14 | Madhya

Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Punjab, Maharashtra, West Bengal |

Phase

3 : 1998-2004 | Above

15 | Bihar, Orissa |

13 to 15 | Madhya

Pradesh, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu |

Below 13 | Kerala,

Gujarat, Haryana, Maharashtra, West Bengal | Many

State Governments showed deterioration in their revenue receipts-GSDP ratio in

the third phase (Chart 3). The componentwise performance of revenue receipts of

State Governments is set out below.

Trends in States’

Own Revenue

States’ own taxes States’

own taxes remained almost stagnant at 7 per cent of GSDP during the second and

third phase. Under State taxes, the poor performance has been mainly marked

in the case of taxes on sales tax, state excise and

stamps

and registrations. The major reasons behind the inadequate growth in States taxes

over the years are (i) narrow tax base, (ii) greater dependence on indirect taxes

mainly the sales tax, (iii) lack of harmonised inter-state tax structure which

allowed distortions and rigidities to creep in, (iv) competitive tax reductions

by the States to attract trade and industry. The competitive reduction in taxes

led to a mere redistribution of existing capital among the States at the cost

of significant revenue foregone, (v) States inabilty to levy taxes on services

and agricultural income, and (vi) tax evasion and slackness in the recovery of

arrears.

States’ own non-tax revenue. The States’

own non-tax revenue in terms of GSDP showed deterioration in the second and third

phases. A major reason underlying the sluggish growth in non-tax revenue is the

levy of inadequate user charges/cost recoveries. The cost recovery in the case

of education and health services has hovered around 1 per cent and 5 per cent,

respectively, in the recent period (RBI, 2005). Apart from inappropriate user

charges, low or negative returns from investment have adversely affected the growth

of States’ own non-tax revenues over the years.

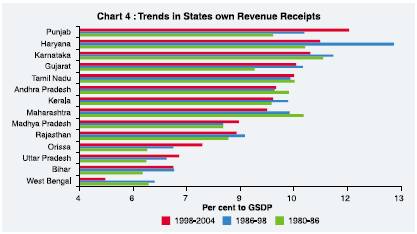

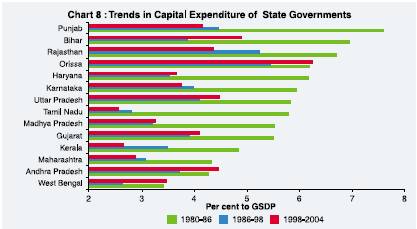

The trends in States’

own revenue receipts (comprising State’ own taxes and own non-taxes) indicate

that the many States such as West Bengal, Karnataka, Haryana, Gujarat and Maharashtra

showed deterioration in the third phase as against the second phase (Chart 4).

Exhibit 6 : States’

Own Revenue-GSDP Ratio: A Comparative Position |

Per cent | Phase

1 : 1980-86 | Above

10 | Karnataka, Haryana, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu |

8 to 10 | Andhra

Pradesh, Punjab, Kerala, Gujarat, Rajasthan,

Madhya Pradesh |

Below 8 | West

Bengal, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar | Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

10 | Haryana, Karnataka, Punjab, Gujarat |

8 to 10 | Tamil

Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala , Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan,

Madhya Pradesh |

Below 8 | Bihar

, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal | Phase

3 : 1998-2004 | Above

10 | Punjab, Haryana, Karnataka, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu |

8 to 10 | Andhra

Pradesh, Kerala, Maharsahtra, Madhya Pradesh,

Rajasthan |

Below 8 | Orissa, Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar, West Bengal | The near stagnation in States

taxes and deterioration in States’ own non taxes resulted in decline in

States’ own revenue from 8.9 per cent of GSDP in second phase to 8.6 per

cent of GSDP in the third phase. The degree of variation, however, varied across

the States (Exhibit 6).

It is worth noting that many States could

finance less than 50 per cent of their total expenditure from own revenue receipts

(Exhibit 7).

Exhibit

7 : Financing of Total Expenditure through States’ Own

Revenues:

A Comparative Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : 1980-86 |

Above 55 | Maharashtra,

Haryana | 50-55 | | Karnataka,

Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Punjab | Below | 50 | Kerala,

Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa |

Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

55

50-55 | Haryana, Maharashtra, Gujarat,

Karnataka

Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Kerala | Below

50 | Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West

Bengal,

Rajasthan,

Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar, Orissa |

Phase 3 : 1998-2004

| Above

55 | Haryana, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu |

50-55 | Karnataka,

Punjab | Below

50 | Gujarat, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya

Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh,

West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar |

Trends

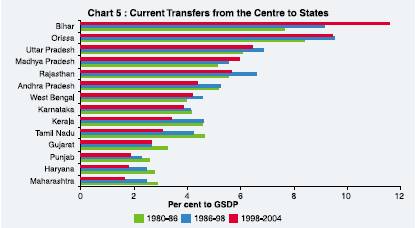

in current transfers and devolution from the Centre

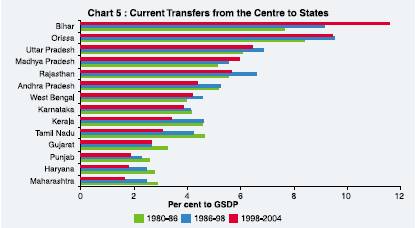

The

trends in central transfers indicate stagnation in terms of GSDP in the second

phase and decline in the third phase due to lower central grants. Bihar, Orissa,

Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan continued to receive the highest level of current

transfers while Punjab, Haryana and Maharashtra occupied the lowest positions

(Chart 5). Pattern and Trends in Total Expenditure

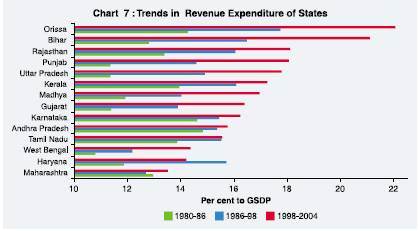

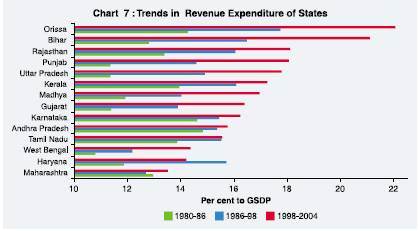

The pattern of expenditure reveals that revenue expenditure accounted for

a significant proportion (about three-fourth) of the total expenditure of the

States over the years. Total expenditure showed a significant increase in many

States such as Orissa, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Punjab (Exhibit 8).

Trends in Revenue Expenditure

Interest

payments, expenses towards administrative services, wages and salaries, pensions

and subsidies given by the States led the revenue expenditure to grow significantly.

Interest payments alone constitute more than one-fifth of the total revenue expenditure.

The major components of revenue expenditure, viz., interest payments

and pensions absorbed as high as over 45 per cent, on an average, of revenue receipts

in the third phase as against 25 percent in the second phase (Exhibit 9 and Chart

6). In fact, in some years (during 2002-03 and 2003-04) these two components of

expenditure absorbed around 70 per cent of revenue receipts in case of West Bengal

and nearly 50 per cent of revenue receipts in case of Kerala.

Exhibit

8 : Total Expenditure-GSDP Ratio of States:

A Comparative

Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : 1980-86 |

Above 20 | Karnataka,

Orissa, Rajasthan | 18

to 20 | Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh,

Punjab, Kerala, Haryana | Below

18 | Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar

Pradesh, Gujarat, West Bengal | Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

20 | Orissa, Rajasthan, Bihar |

18 to 20 | Kerala,

Karnataka, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu |

Below 18 | Gujarat,

Madhya Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, West Bengal |

Phase 3 : 1998-2004 |

Above 20 | Orissa,

Bihar, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh |

18 to 20 | Karnataka,

Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh | Below

18 | Haryana, West Bengal, Maharashtra |

Exhibit

9 : Interest Payments and Pensions as per cent to

Revenue

Receipts: A Comparative Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : 1980-86 |

Above 14 | Rajasthan,

Kerala | 12 to 14 | Punjab,

West Bengal, Orissa, Karnataka | Below

12 | Bihar, Haryana, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh,

Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, | | Maharashtra,

Madhya Pradesh | Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

25 | Kerala, Orissa, Punjab |

22 to 25 | West

Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan | Below

22 | Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka,

Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Maharashtra |

Phase 3 : 1998-2004 |

Above 45 | West

Bengal, Kerala, Punjab | 35

to 45 | Orissa, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar | Below 35 | Gujarat,

Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh |

The

significant increase in revenue expenditure was observed in States such as Orissa,

Bihar, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Kerala and Rajasthan in the third phase

over the second phase (Chart 7 and Exhibit 10).

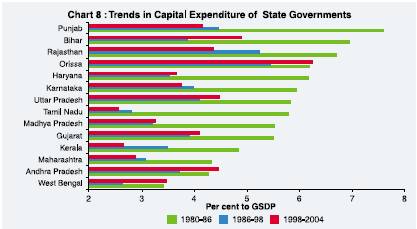

Trends in

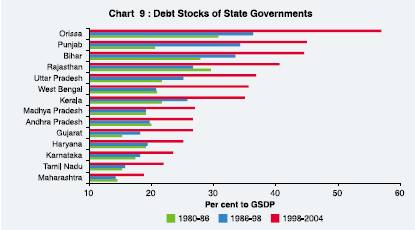

Capital Expenditure

The impact of resource crunch and

the need for fiscal correction has more often been in form of a compromise in

the capital expenditure. Amidst the fiscal consolidation process in the 1990s,

Exhibit

10 : States’ Revenue Expenditure-GSDP Ratio:

A Comparative

Position | Per

cent | Phase 1 : 1980-86 |

Above 14 | Andhra

Pradesh, Karnataka, Orissa, Kerala | 12

to 14 | Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Maharashtra,

Bihar | Below 12 | Madhya

Pradesh, Haryana, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, West Bengal |

Phase 2: 1986-98 |

Above 16 | Orissa,

Bihar, Kerala, Rajasthan | 14

to 16 | Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka,

Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh |

Below 14 | Gujarat

, Maharashtra, West Bengal | Phase

3 : 1998-2004 | Above

18 | Orissa, Bihar |

16 to 18 | Rajasthan,

Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat |

Below 16 | Andhra

Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Haryana, Maharashtra, Karnataka |

the capital expenditure of many States started to show declining

trend (Chart 8 and Exhibit 11).

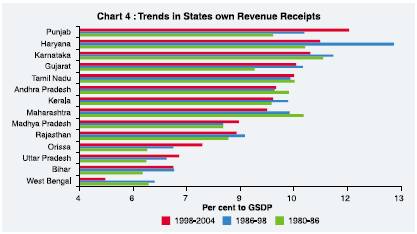

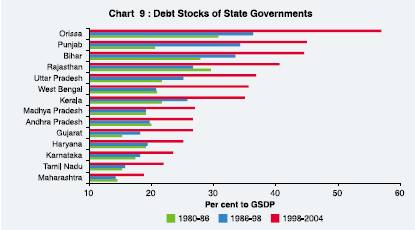

Debt Stocks of Major States

Persistenee of large deficits of State Governments has resulted in accumulation

of large debt stocks. The growth in debt stocks varied across States. Debt-GSDP

ratio was higher by 19 per cent in case of Orissa, 15 per cent for West Bengal,

14 per cent for Rajasthan and 12

Exhibit

11 : States’ Capital Expenditure-GSDP Ratio:

A Comparative

Position | Per

cent |

Phase 1 : 1980-86 | Above

6.0 | Haryana, Orissa, Rajasthan, Bihar,

Punjab | 5.5 to

6.0 | Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu,

Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka | Below

5.5 | West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra,

Kerala | Phase

2: 1986-98 | Above

4.0 | Orissa, Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh |

3.5 to 4.0 | Karnataka,

Gujarat, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Kerala |

Below 3.5 | Madhya

Pradesh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal |

Phase 3 : 1998-2004 |

Above 6.0 | Orissa |

4.0 to 6.0 | Bihar,

Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Gujarat |

Below 4.0 | Karnataka,

Haryana, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu |

per cent for Uttar Pradesh in the third phase over the second

phase (Chart 9).

In addition to budgetary debt, states have also increasingly

resorted to off-budget borrowings through guarantees. With States increasingly

accessing the market for resources, those with poor fiscal position may find financial

markets unwilling to absorb their securities. Recognising the magnitude of the

problem, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) and the Finance Commissions

in their various reports have sounded warnings about the unsustainability of finances

of State Governments. During 2003-04, the outstanding State Government’

Guarantees in terms of GSDP were above 15 per cent in a number of States such

as Maharashtra, Kerala, Punjab and Rajasthan.

Section III

A Review of Policy Measures

The growing fiscal imbalances of the States called for structured policy

initiatives to address the problem. These initiatives had to be operationalised

by the States when the Eleventh Finance Commission set binding preconditions for

undertaking reforms to get the fiscal assistance. The policy initiatives include

preparation of Medium-Term Fiscal Reform Programmes (MTFRPs). Adjustment programme

had also been undertaken in some of the States which were linked to borrowings

from multilateral agencies. Major landmark in coordinated tax reforms were simplification

and rationlisation of the sales tax system since the beginning of the current

decade and the introduction of VAT from April 1, 2005, in place of the existing

cascading type sales (Rao, et al., 2005). Incentive based fiscal reforms

recommended by the TFC are also an important policy step towards bringing fisal

discipline at State level.

Supplementing the States efforts, the Central

Government introduced measures to encourage and facilitate fiscal reforms at the

State level. These mainly include: (i) introduction of Fiscal Reforms Facility,

(ii) one time settlement of State Electricity Boards, (iii) introduction of Debt

Swap Scheme and debt relief measures. The Reserve Bank of India, as debt manager

and banker to the State Governments has also initiated measures towards strengthening

their fiscal position. The major initiatives include: (i) constitution of various

Group/Committees on State finances, (ii) managing Market Borrowings Programme

of States, (iii) organising conferences on State Finances, (iv) policy initiatives

towards cash management, (v) policy initiatives towards off-budget borrowings7.

The policy measures initiated by the States may be grouped under three

categories, viz., (i) Policy measures towards State taxes and non-taxes,

(ii) Expenditure Management, and (iii) Institutional Reforms. The detatils of

these policy measures are set out below.

Policy Measures towards

States’ taxes and non-taxes

States’

taxes

The general approach of the States has been to rationalise

and simplify the tax structure, broaden the tax base and impose moderate rates

of taxation. States have initiated policy measures towards fiscal empowerment

mainly through States own taxes and showed intention to increase the magnitude

and efficiency of tax revenue mobilisation over the years. The initiated measures

by States include enhancement/ restructuring of various taxes such as land revenue,

vehicle tax, entertainment tax, sales tax, electricity duty, tax on trades, professional

tax and luxury tax. The major policy initiatives are as under:

(i)

Expert Committees/Commissions: A number of States have appointed committee/commission

to review the structure of their tax and non-tax revenues (Exhibit 12). The efforts

were also initiated towards computerisation of tax/budget departments, treasuries

and check-posts in view of the VAT as implementated by the States.

Exhibit

12 : Policy Initiatives by Major States |

Policy Measures | Name

of the State | 1.

Expert Committee/Commissions | Andhra Pradesh

(Revenue Reforms Committee), Karnataka (Tax and Revenue Reforms Commission,

Fiscal Policy and

Analysis Cell), Tamil Nadu (Taxation Reforms

and Revenue Augmentation Commission, Staff and Expenditure Reforms Commission,

Disinvestment Commission), Haryana (Committee to Mobilise Additional

Resources),

Maharashtra (Consultative Committee of Trade and Industry),

Uttar Pradesh (Resource and Expenditure Commission) |

2. Introduction of VAT | All

the States have introduced VAT except Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. Haryana was

the first State to introduce the VAT in April 2003. |

3. One-time settlement/amnesty schemes for recovery

of tax arrears. | A number of States including

those of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Kerala | (ii)

Introduction of VAT: Realising the need for tax reforms,

most of the States have switched over to a VAT regime on the basis of recommendations

of the Empowered Committee of State Finance Ministers with effect from April 1,

2005. VAT may be defined as a tax on the value added at each stage of production

and distribution of a commodity. VAT is inherently efficient than the sales tax

or excise duty or any turnover tax. Operationally, application of VAT at a particular

stage implies payment of tax by the producer or distributor on the value of his

output but with a rebate (or credit) on the taxes paid by him on the inputs.

States’ non-tax revenues

The policy

measures towards non-taxes include reviewing/ rationalising the royalties, including

those on major and minor minerals, forestry and wildlife, revision of tuition

fees, medical fees, irrigation water rates and tariffs on urban water supply.

The States have prepared MTFRPs and have emphasised on the cost effectiveness

and raising user charges of services rendered by them.

Expenditure

Management

The major policy initiatives on expenditure front

include containing unproductive expenditures and reorienting spending towards

developmental purpose, restrictions on fresh recruitment/ creation of new posts,

review of manpower requirements, cut in establishment expenses and reduction in

non-merit subsidies through better targeting. In their recent budgets, some State

Governments, such as Punjab, have called for restructuring of the staff position

in each government department and have indicated that future employment in the

government would be project-specific and need-based.

Tamil Nadu

took initiatives to constitute an Expenditure Review Committee to review,

on an on-going basis, the expenditure in respect of each department. States, like

Punjab, have initiated measures towards disinvestment on a select basis in respect

of loss-making Public Sector Undertakings. Many States including those of Andhra

Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have

introduced the new pension scheme based on the defined contribution system. Institutional

Reforms

The institutional reforms facilitating the fiscal

consolidation process are set out below:

Rule based fiscal

policy measures: Recognising the need for providing statutory

backing to the fiscal reforms, many States have initiated measures to enact the

FRLs targeting to eliminate revenue deficit and reduce GFD (Exhibit 13).

Other Institutional Reforms: Theseinclude setting

up of the Guarantee Redemption Fund, Consolidated Sinking Fund and Ceiling on

Guarantees (Exhibit13).

State Public Sector Undertakings Reforms

Several States have shown interest in undertaking a comprehensive review

of the functioning of the State Public Sector Undertakings (SPSUs), including

the possibility of closing down of non-viable units after providing for suitable

safety-nets to the employees including voluntary retirement scheme (VRS). States

such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Haryana, Karnataka and Orissa have encouraged

private sector participation in the transport and power generation sectors. Karnataka’s

initiatives towards Policy Paper on restructuring of SPSUs and Maharashtra’s

initiatives towards setting up a Board for Restructuring of the SPSUs are noteworthy.

A notable development has been the initiation of power sector reforms which include

the constitution of State Electricity Regulatory Commissions (SERCs) for determining

the tariff structure,

Exhibit

13 : Initiatives towards Institutional Reforms by Major States |

Institutional Reforms | Name

of the State | 1.

Fiscal Responsibility Legislation | All

the major States (except Bihar and West Bengal) have enacted FRLs. |

2. Guarantee Redemption Fund | Andhra

Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Orissa, Rajasthan |

3. Ceiling on Guarantees | Gujarat,

Karnataka, Kerala, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal |

4. Consolidated Sinking Fund | Andhra

Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Maharashtra, Orissa, West Bengal | unbundling

of electricity boards into separate entities for power generation, transmission

and distribution, increasing power tariffs and measures for reducing transmission

and distribution losses. Section IV

Effectiveness of Policy Measures

The effectiveness of policy measures to strengthen the State finances remained

largely inadequate keeping in view of the size of the problem. Most of the policy

measures were ad hoc in nature and were guided by the exigency rather

than being structured and well planned to put the State finances on the right

path. The componentwise details of various policy measures and their effectiveness

to strengthen the State finances are set out below.

Effectiveness

of Revenue Mobilisation Measures

The policy initiatives towards

revenue mobilisation remained inadequate to keep pace with the growing expenditure

requirements. These are discussed below.

States’ Tax

Revenues

Taking into account the past trends of State

finances and the literature available on State finances, it seems that there was

not much progress on restructuring of State finances. Many State Governments continued

to carry their business as usual. There has been some progress in reforming the

tax system, although the leakages in tax base through exemptions continue to pose

problems (RBI, 2005). States took initiatives towards setting up Committees/ Groups

and prepared MTFRPs to suggest the ways to enhance revenues. However, the implementation

part of these measures remained weak as evident with the near stagnation in States

taxes-GSDP ratios in the 1990s.

Despite the States’ efforts towards

enhancing revenues, the factors, such as, narrow States’ tax base, greater

dependence on indirect taxes and lack of control on populist measures (such as

free electricity) taken by States continued to persist. Furthermore, the increased

competition among the States to attract the investment by providing tax concessions

and other fiscal incentives has only resulted in a race to the bottom (Rastogi,

2004). Competitive reduction in taxes led to a mere redistribution of existing

capital among the States at the cost of significant revenue foregone, while taxes

could not be levied on services and agricultural income (Rao, 2002).

States’ Non-Tax Revenues The effectiveness of various

non-tax reforms to improve cost recovery for major social and economic services

provided by States has remained below the expectations. This is reflected in very

low user charges/cost recovery from various services and low/negative returns

from investment in PSEs. User charges remained inadequate because of the perception

of availing government services as free. Furthermore, with the inferior quality

of services, the public is loath to pay higher charges for public services. Cost

recovery in the case of a number of social services, such as education and health,

have hovered around 1 per cent and 5 per cent, respectively, in the recent

period. The cost recovery in respect of economic services such as irrigation,

roads and power is found to be higher than that of social services but still remains

quite low (RBI, 2005). It seems that there is no link between capacity to borrow

and the return on services provided by the Government. Since there is not enough

incentive for the government to undertake appropriate levy of user charges, states

are encouraged to become fiscally irresponsible and to subject user charges to

populist considerations (Mohan, 2000; Acharya, 2002).

Over the years,

States have initiated a number of measures to improve the functioning of State

public sector enterprises (PSEs). There has, however, not been adequate generation

of revenues in the form of dividends and profits received from the PSEs. There

is a need to take a relook of the functioning of PSEs in order to ensure the viability

of running State level PSEs in long run. Around one-fourth of the total State

public sector enterprises are profit making while the rest are the largest drain

on the system. Most State PSEs are unlikely to yield significant resources from

privatisation proceeds, but privatisation could at least help avoid recurring

losses which are otherwise a burden on the budgets. The power sector remains the

worst affected by the populist measures announced by a number of States. The average

tariff rate for electricity provided to agriculture remained 25 paisa per kwh

for all States (even some States have actually made it free) while average cost

of supplying power remained Rs.2.81 per unit. Irrigation charges cover only around

one fifth of the maintenance costs of the system, to say nothing of capital charges

(Ahluwalia, 2001).

The reforms initiated in the power sector in

recent years at State level are encouraging. However, keeping in view of the past

record of populist measures such as free electricity, for certain sectors requires

a close monitoring on the effectiveness of these reforms. In view of the large

investment made by States in the public sector enterprises, state level fiscal

strategy should be designed in a manner which ensures that these returns in the

form of user charges and profits from commercial activities be adequate and augment

fiscal discipline.

Effectiveness of Expenditure Management Measures

The effectiveness of policy measures towards expenditure management could

be seen in the light of the fact the non-developmental expenditure (comprising,

inter alia, interest payments, pensions and administrative services)

has shown noticeable increase and stood at around 7 per cent of GSDP in the third

phase higher by over 3 per cent and 2 per cent than the first phase and second

phase, respectively. A sizeable reduction in non-developmental expenditure may

not be feasible in the short-term, given the committed nature of many of its constituent

items.

Notwithstanding the downward rigidity, the Debt Swap Scheme

has brought about definite savings on interest costs as far as interest payments

are concerned. Here again the question arises what about the higher interest cost

in case of those loans negotiated from banks and FIs. Furthermore, the high interest

cost on small saving receipts used by States to finance the resource gap also

assume importance.

The States initiatives towards containing the

subsidies were also not much effective and the subsidies given to various sectors

including those of power sector and State road transport corporations continued

to increase. Over the years, the inability to contain consumption expenditure

due to explicit and implicit subsidies, which are mostly cornered by the influential

segments of the society, and the reluctance to raise additional resources on the

part of the States have been the main causes for the deterioration of fiscal situation

in States (Kurian, 1999). Direct and indirect subsidies provided by State Governments,

most of which are not well targeted, have become unsustainable (Ahluwalia, 2001).

The power subsidies have increased manifold over the years and even after subventions

(financial support) from State Governments and cross-subsidisation, the magnitude

of the ‘uncovered’ subsidy leaves little scope for the State Electricity

Boards (SEBs), but to default on payments (RBI, 2004).

The States

efforts to enhance desired allocations towards developmental expenditure could

not materalise with the fact that in terms of GSDP this component of expenditure

in the third phase showed decline around one percentage point from the earlier

phases. The share of developmental expenditure in total expenditure also continued

to show deterioration in the second and third phase.

To sum up,

it is worth noting as stated in the Draft on “Towards Faster and More

Inclusive Growth: An Approach to the Eleventh Five Year Plan”, Planning

Commission, Government of India, “….Fiscal discipline also requires

control in non-Plan expenditure by both the Centre and the States. Some of what

is non-Plan expenditure is essential for effective delivery of public services.

Another part is pre committed such as interest payments and pensions. Effective

control must be exercised in the rest of non-Plan expenditure if ambitious plan

targets are to be met. In practice this means control of subsidies and also levy

of rational user charges to keep the demands on budgetary expenditure within limits”.

Section V

Concluding Observations

The fiscal imbalances at State level appeared in the second phase had deepened

and continued to persist in the third phase. The States took policy measures which

helped to some extent to avoid further worsening of their fiscal position; however,

these have not been significant. The recent fiscal developments at State level

put emphasis on the on-going fiscal and institutional reforms and seem to follow

the path of reforms as suggested by the TFC. As the States face large resource

gap, they would have to explore new avenues apart from utilising the traditional

resources effectively and efficiently. States need to set priorities in their

expenditures to reap the benefits and operate their economy in its full capacity.

Notwithstanding some moderation in fiscal imbalances in recent years, the

low and stagnant revenues particularly non taxes and large component of non developmental

expenditure requires the States to take corrective measures. Interest payments

account a major portion of the revenue expenditure and absorb a sizeable portion

of revenue receipts in case of many States. The increasing liabilities from the

NSSF need to be addressed as they involve high interest cost. Furthermore, the

loans contracted from banks and financial institutions in the past also carry

high interest rate. The upturn in interest rate cycle, currenly underway,

is likely to put further pressure on interest burden of the States

In

view of the large and persistent resource gap, the cornerstone of the fiscal strategy

pursued at State level needs to be examined as per the changing requirements.

As rightly stated in the Mid Term Appraisal of the Tenth Five Year Plan 2002-07,

Government of India, “Improving resources of States on a sustainable

basis, providing incentives for developmental performance, fiscal prudence and

accountability and putting in place successful and flexible mechanisms for intergovernmental

transfer are key issues, not only in the remaining period of the Tenth Plan but

even more for the Eleventh Plan”.To sum up, the fiscal policy pursued

at State level needs to be mainly focussed on (i) to broaden tax base including

those of agriculture income and to reduce exemptions/concessions, (ii) administrative

and legislative reforms in taxation, (iii) increase in cost recovery/user charges

and returns from public investment, (iv) public sector undertakings restructuring,

(v) rationalisation and containment of both explicit and implicit subsidies, (vi)

expenditure reprioritisation towards social and productive sectors and, more importantly,

(vii) institutional reforms. These initiatives would go a long way to bring fiscal

discipline and sustainability in the public finance at State level.

Notes

1 Major deficits of States revealed marginal improvement

during 2000-03; however, States’ fiscal health again deteriorated in 2003-04.

Notwithstanding some moderation in major deficits, the low and stagnant revenues

particularly non tax and large component of non developmental expenditure remained

cause of concern.

2 The data have been sourced from the State finances

articles, various issues published by the RBI and the Budget Documents of the

State Governments. The GSDP data have been sourced from the Central Statistical

Organisation website.

3 The analytical review is based on the fiscal

position of 14 major States of India. These States account for about 90

per cent of aggregate budget of all States. Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and

Bihar are taken as undivided States for purpose of comparison. North Eastern

and other special category States have been excluded from the analysis because

of special features and also gaps in the data for some of these States. The small

States of Goa and Delhi have also been excluded, the latter having the additional

feature of being the capital.

4 West Bengal’s Revenue Account

was in surplus (0.4 per cent of GSDP) only in 1985-86 and the rest of the period

State’s Revenue Account was in deficit (on an average at 1.2 per cent of

GSDP).

5 The TFC also recommended, if, however, some fiscally weak States

are unable to raise funds from the market, the Centre could resort to lending,

but the interest rate should remain aligned to the marginal cost of borrowings

for the Centre.

6 The constitution of the Sixth Pay Commission

has been approved by the Union Cabinet on July 20, 2006.

7 For

further details of these policy measures, please see RBI’s publication

: State Finances: A Study of Budgets”, various issues, published

by the RBI annually. References

Acharya, S.

(2002), “Macroeconomic Management in the 1990s”, Economic and

Political Weekly (April 20-27); p. 1515-38.

Ahluwalia, Montek

S. (2000), “Economic Performance of States in Post Reforms Period”,

Economic and Political Weekly, May 6, pp 1637-48.

—— (2001), “State Level Performance under Economic Reforms in

India” Center for Research on Economic Development and Policy Reforms, Working

Paper No 96, March.

Bagchi, Amaresh (2005), Symposium on Report of

Twelfth Finance Commission, Introduction and Overview, Economic and Political

Weekly, July 30.

Bagchi, Amaresh (2003), “Fifty Years of

Fiscal Federalism in India: An Appraisal” NIPFP Working Paper No.2.

Government of India, Report of the Finance Commission, (various issues),

Ministry of Finance.

——, Mid-Term Appraisal of the Tenth

Five Year Plan (2002-07).

——, (Draft) An Approach to

the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-12).

——, Economic

Survey, various issues.

Kannan, R., S.M. Pillai, R. Kausaliya and Jai

Chander, (2004), “Finance Commission Awards in India and Fiscal Stability

in State Finances” Economic and Political Weekly, January

31.

Kurian N.J. (2000), “Widening Regional Disparities in India,

Some Indicators”, Economic and Political Weekly, February 12; pp

538-550.

Lahiri, Ashok, 2000, “Sub National Public Finance in

India”, Economic and Political Weekly, April 29.

Lahiri,

A. and R. Kannan (2001), “India’s Fiscal Deficits and their Sustainability

in Perspective”. Paper presented at World Bank-NIPFP Seminar on Fiscal Policies

for Growth.

Mohan, Rakesh (2000), “Fiscal Correction for Economic

Growth: Data Analysis and Suggestions”, Economic and Political Weekly,

June 10-16, XXXV:24; 2027-36.

Pillai, S.M., S. Chatterjee, B. Singh,

S. Das and A. Gupta (1997), “Fiscal Policy: Issues and Perspectives, RBI

Occasional Papers, No. 18

Pinto, Brian and Farah Zahir (2004),

“India: Why Fiscal Adjustment Now”World Bank Policy Research Working

Paper 3230, March.

Rajaraman, Indira, Shashank Bhide and R.K.

Pattnaik (2005), “A Study of Debt Sustainability at State Level in

India”, RBI Bulletin, October.

Rangarajan, C. and D.K. Srivastava

(2005), “Fiscal Deficits and Government Debt in India: Implications for

Growth and Stabilisation”, NIPFP Working Paper No. 35.

Rakshit,

Mihir (2005), “Some Analytics and Empirics of Fiscal Restructuring in India”,

Economic and Political Weekly, July, 30; pp 3440-3449.

Rao,

M. Govinda (2002), “State Finances in India: Issues and Challenges”,

Economic and Political Weekly, August 3; pp 3261-3271.

Rao,

M. Govinda and R. Kavita Rao (2005), “Trends and Issues in Tax Policy

and Reform in India”, NIPFP, Working Paper no 1, 2005, November.

Rastogi, Anupam (2004), “ Restructuring Public Finances”, Economic

and Political Weekly, June 26

Reserve Bank of India, Report

on Currency and Finance, various issues.

——, Annual

Report, various issues.

——, Article on State Finances,

various issues.

Reddy, Y.V., (2001), “Fiscal Reforms at

the State Level: Review and Prospects”, RBI Bulletin, January.

State Governments, Economic Survey, various issues.

World Bank

(2005), “State Fiscal Reforms in India, Progress and Prospects”, A

World Bank Report.

* Shri Rajmal is Research Officer in the Department

of Economic Analysis and Policy of the Reserve Bank of India. The views expressed

are those of the author and not of the institution to which he belongs. |

IST,

IST,