IST,

IST,

State Government Market Borrowings - Issues and Prospects

Shri B. P. Kanungo, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India

delivered-on ਅਗ 31, 2018

|

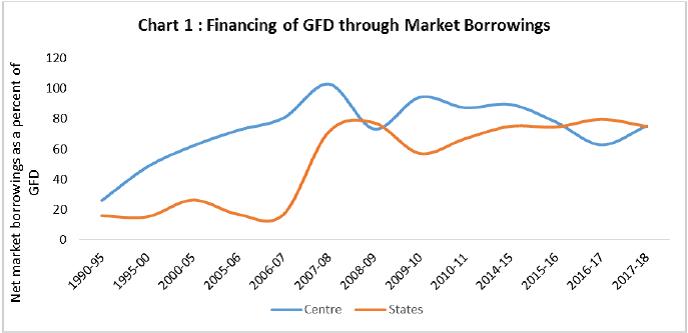

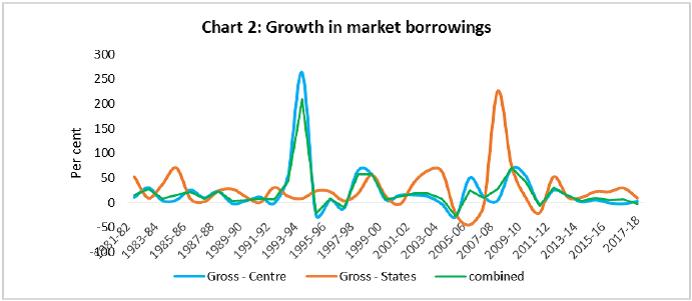

Shri Chandra Shekhar Ghosh, President, Bengal Chamber of Commerce, Shri T. Bandopadhyay, ladies and gentlemen. I am thankful to the Bengal Chamber of Commerce and Industry for providing me the opportunity to be present here and speak on the subject of ‘State Government Borrowing’. In the federal system of governance that we have in our country, both the Central and the State Governments are responsible for the development of the nation. To discharge the responsibility, the overall magnitude of the State Budgets is significant, and the nature of spending incurred by the states is crucial for development. As states have their own developmental priorities, financing the budgets assumes vital importance. Given this scenario, it is important to examine the current conditions of budget and debt management at state level, identify the issues and dwell on the prospects. State Budgets have increased in size: Over the past decade the size of State Government budgets have increased sharply, and they now collectively spend substantially more than the Union Government. Aggregate Expenditure of the state governments increased to ₹ 30,285.1 billion in 2017-18 (RE) from ₹ 12,847.1 billion in 2011-12 and is further expected to increase to ₹ 33,592.2 billion in 2018-19 (BE). Growth in their aggregate expenditure has also outpaced that of the Central Government for each of the years since 2011-12. Fiscal imbalances are also rising: It is a matter of concern that the finances of State Governments are showing signs of increasing fiscal imbalance. Reserve Bank in its ‘State Finances: A Study of Budgets of 2017-18’ observed that the consolidated fiscal position of states deteriorated during 2015-16 and 2016-17. The GFD-GDP ratio in 2017-18 (RE) is at 3.1 per cent and is above the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) threshold for the third consecutive year. Outstanding liabilities of State Governments have been registering double digit growth since 2012-13 (2014-15 being an exception). State-wise data reveal that the debt-GSDP ratio increased for 16 states. The downside risks to fiscal position of the states include stress on revenue expenditure in the run-up to the general elections, implementation of 7th pay commission recommendations by states, and farm loan waivers in certain states etc. Fiscal slippages have also been noticed in central finances. In response to the Global Financial crisis, the FRBM Act was put on hold during 2008-13 and fiscal stimuli expanded the centre’s gross fiscal deficit (GFD) to an average of 5.6 per cent of GDP during this period. During the period 2013-18, the GFD of the Centre, as a percentage of GDP averaged 3.9 per cent. The GFD target of 3 per cent of GDP, stipulated in FRBM Act, now stands deferred to 2020-21. In retrospect, the Central Government has achieved the target in one year only, i.e., in 2007-08 when the GFD/GDP ratio fell to 2.5 per cent. Growing fiscal imbalance, whether by the Centre or State can derail fiscal consolidation at the general Government level. General Government deficit of India rules at a very elevated level amongst the G-20 countries. States market borrowings have increased: A consequence of large expenditures and deficits is an increase in market borrowings reflecting rising trend in fiscal imbalance at States level and increase in outstanding liabilities. The Indian State Governments’ market borrowings, which is the chief source of funding of their gross fiscal deficits, have risen sharply in recent years, in contrast to the stagnation displayed by the Central Government’s dated market borrowings. The financing of gross fiscal deficit (GFD) through market borrowings, which constituted small fraction of sources of financing before 1990, increased significantly to 74.9 per cent in 2017-18 (BE) (Chart 1). Therefore, it is not surprising to note that gross as well as net market borrowings of State Governments are budgeted to be similar to that of the Central Government in the current fiscal year. States have also borrowed significantly to take over the liabilities of state power utilities under UDAY Scheme. On an aggregate basis, states’ gross borrowings are budgeted to rise to ₹ 5500 billion or 2.9 per cent of GDP, while net borrowings are expected to rise to ₹ 4200 billion or 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2018-19. States have budgeted to finance nearly 91 per cent of their fiscal deficit through market borrowings as against around 66 per cent by the central government. Gross borrowings by State Governments are projected to increase 28.5 per cent year-on-year (y-o-y) during 2018-19. Financing Mix has changed: The changes in financing mix of states also contributed to increased reliance on market borrowings. Pursuant to the recommendation of Finance Commission-XIV, almost all states have opted out of National Small Savings Fund (NSSF). As a result, reliance of State Governments on market borrowings has increased substantially in recent years. Increased redemptions, emanating from higher market borrowing of 0.5 per cent of GFD consequent to fiscal stimulus provided to the states in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) 2007-08, also contributed to the rise in borrowings2 (Chart 2). This has led to the pace of increase in market borrowings of State Governments higher than that of the Centre, which is more or less at stagnant levels over the past couple of years. Impact of higher borrowings: Considering the large redemption pressure of around ₹ 1.3 trillion, gross market borrowings are expected to cross ₹6 trillion in FY19, slightly more than Central Government gross borrowing numbers for the fiscal year. Market share of State Development Loans (SDL) in outstanding has increased from 16.59 per cent in 2008-09 to 29.06 per cent in 2018-19 as against decrease in share of GoI from 83.41 per cent (G-Sec & T-Bills) to 70.94 per cent during the same period. Although market borrowings of the Centre and the State governments have been managed successfully by Reserve Bank, the increasing reliance on market borrowings by States have raised concerns both from the supply and demand side and need to be managed so as to minimise any adverse effects on yields. I would highlight some of these concerns. i. Hardening of yields: Increased reliance of Centre and States on market borrowings led to an oversupply of Government paper in the G-Sec market and contributed to hardening of sovereign yields. This results in a spiral, whereby increased market borrowings result in increasing redemption pressures which induces further borrowing to service outstanding debt and accumulated interest burden. Weighted average yield increased from 7.48 per cent in 2016-17 to 7.60 per cent in 2017-18. Average spreads of SDL yields over Central Government securities of corresponding maturity have increased from 38 bps in 2014-15 to 59 bps in 2017-18 signifying increase in the cost of borrowing for the States. As the investor base for G-Sec and SDLs are almost same, the continuous and large supply of SDLs had resulted in hardening of yields of Central Government securities also.

ii. Impact on the corporate bond market: An internal study of RBI and CAFRAL had examined the impact of SDL spreads on corporate bond yields and it was observed that rise in yields on state government paper end up pushing spreads on corporate bonds. Unlike Central Government debt which crowds out bank credit, SDL crowds out corporate borrowings in the bond market by increasing costs. A one percentage point increase in the ratio of state debt issuance to GDP, results in an 11 per cent decline in the volume (in Rupees) of corporate bonds issued in FY2016. High rated corporate bonds and those with longer maturity have a greater propensity for being crowded out by SDLs which work as substitutes. iii. Impact on other segments of the financial market: The increased supply and consequent hardening of yields, especially so in case of the benchmark 10 year security, has a cascading effect on interest rates in other segments of the financial market, as pricing of other products are based on the risk-free yield curve. This feeds into inflation through input costs, further increasing yield levels, thereby creating a vicious cycle. Since economy is poised for higher growth trajectory, the private sector demand for domestic funding is expected to significantly accelerate in coming years. Hence, stake holders would have to be sensitive not only to their own interest expenses but also to that of the financial sector. iv. Diminishing demand from banks: Given the large borrowing requirement of Centre and States, assessment of the institutional demand for government securities is paramount. Captive funding is diminishing as banks are following the glide path for reducing the SLR requirements. In a market confronted by reduced pre-emption in the form of SLR, reduction in HTM and likely adoption of IFRS that will seek to mandate mark to market (MtM) accounting, the demand for government bonds could be impacted. Additionally, international capital standards post GFC (Basel III), to which India is an active participant, proposes to assign credit risk weights to sub-sovereign borrowings. If and when accepted, this development is likely to impact the cost of borrowing for State Governments and the attraction to hold SDLs in banks’ books, for reason other than the YTM they offer. Further Basel III capital requirements also seek to define High Quality Liquid Assets under it’s the Liquidity Coverage Ratio(LCR) framework. As per our extant regulations, SDLs being similar to Government of India (GOI) securities qualify for inclusion as part of level 1 High Quality Liquid Assets(HQLA), by virtue of an implicit sovereign guarantee and default free status for its market borrowings. This may change in the future, in which case banks may have to begin assigning risk weights to SDLs. State Governments will need to strategize for this eventuality. v. Limited participation of FPIs: As part of the measures to increase the investor base, attracting Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) towards SDLs would be essential for meeting the increased borrowing requirements. As per Medium Term Framework (MTF), the FPI limits were to increase in phases to reach 2 per cent of the outstanding stock by March 2018. However, the FPI limit utilization of SDLs stood at only 12 per cent of the limit for the quarter ending March 2018, and lower at 10 per cent of the limit for the quarter ending June 2018. FPIs have cited lack of information on financial position of states between two budgets, and opacity of State Government (SG) operations as one of the main reasons for lackluster interest in SDLs, despite the yields they have to offer. There is, hence, a need to reach out to investors by introducing transparency and making accessible high frequency data on State finances in public domain. vi. Large cash balances and negative carry: An analysis of surplus cash maintained by the States in the past years throws light on the fact that there are States resorting to market borrowings despite having a surplus invested in ITBs and ATBs with a negative carry on such investments. If a SG is investing in T-Bills locked in for 182 days and 364 days, there is a need to re-examine states’ market borrowing programme. Further, accumulation of large surplus cash balance by State Governments reduces liquidity in the market thereby contributing to the pressure on interest rate prevailing in the market. It is, therefore, necessary for States with large surplus to rationalize their borrowings in tandem with their surplus cash balance. During 2017-18, seven states had raised less than 85 per cent of the amount sanctioned for the year reflecting the fact that these States require lesser than the sanctioned amount. To address these issues, the States have to devise a mechanism for monitoring their surplus on a continuous basis and mapping it to their market borrowing programme, with the assistance of external consultants, if need be. This will reduce the inflow of bonds into the market, reduce the pressure on yields and have a positive impact on the borrowing cost of both Centre and other States. vii. Market microstructure and illiquidity in SDLs: The SDL market is relatively illiquid, especially when compared with Central Government bonds. This illiquidity premium is reflected in spreads. The liquidity of SDLs in the secondary market as reflected from its share in total G-Sec secondary market, remains significantly low (less than 5 per cent). The lack of liquidity can be attributed to reasons such as low outstanding stock of multiple SDLs, market microstructure issues and lack of market makers. SDLs are almost always new issuances, and hence are fragmented lacking critical mass to improve trading volumes. In 2017-18, the Central Government had 156 reissuances out of a total of 159 issuances, while state governments had 43 reissuances out of 411 issuances. Thus, there is a need for reissuance by State Governments. The SDL market microstructure could also partly explain low liquidity. As on March 2018, more than half of SDLs ownership consisted of insurance companies (33.5 per cent) and PFs (18.1 per cent) who are largely investors who hold the bonds till maturity. Even banks investing in SDLs are averse to trading because of the valuation norms which facilitate nudging up of the price of SDL in banks’ books and insulation from market risks offered by HTM dispensation. With an objective to ensure banks’ bond portfolios reflect their current market valuation, it has been decided that the SDLs should be valued based on observed prices. This measure could potentially discourage passive investment by banks and improve trading volumes in SDL. The market is also devoid of market-makers providing two-way quotes, thereby impacting liquidity. Risk asymmetry in SDLs Following the recommendations of the 12th Finance Commission, government disintermediated from the borrowings of State Governments from FY06 onwards. It was expected that a rise in the volume of market borrowings would enhance the scrutiny of the states’ fiscal health, and superior fiscal management would be incentivized through lower borrowing costs. However, the cut-off yields of SDLs issued by states in any given auction remain narrowly clustered, despite large variations in the state governments’ fiscal performance. A closer look at the data indicates that there has been no significant difference in inter-state spreads, which on an average have been between 5-7 bps. States with better fiscal parameters have expressed view that the market is not providing any incentive for better performance on fiscal front. The issue pertaining to risk asymmetries across states have been receiving policy attention as can be seen from observations in two reports viz., The Economic Survey 2016-17 and the FRBM Review Committee Report, 2017 headed by Shri N. K. Singh. i) The Economic Survey 2016-17 stated that greater market-based discipline on state government finances is missing, as reflected in the complete lack of correlation between the spread on state government bonds and their debt or deficit positions. It was observed that there is a flat relationship between the spread and the indebtedness of states therefore states are neither rewarded nor penalized for their debt performance.” ii) The FRBM Review Committee Report titled “Responsible Growth: A Debt and Fiscal Framework for 21st Century India” published in January 2017 stated that Despite SDL borrowing rates being market determined, it is felt that risk asymmetries across states are not adequately reflected in the cost of borrowings. The report observed that few well managed states with good fiscal performance have expressed that they are not adequately compensated for better management of their fiscal and there is some element of cross subsidization by the financially stronger states of the other states which is akin to financial repression.” To address this anomaly, RBI has taken several measures. The measures include a) conducting of weekly auction of SDLs since October 24, 2017 to prevent bunching of issuances, b) publishing of high frequency data in the RBI Monthly Bulletin relating to the buffers SGs maintain with RBI, the financial accommodation availed under various facilities by each SG from the RBI, the market borrowings and the outstanding of SDLs, so as to add transparency essential for deepening the SDL market. c) The interest rate on borrowing against the collateral of Consolidated Sinking Fund (CSF) and Guarantee Redemption Fund (GRF) funds has been lowered to incentivize State Governments to increase these buffers, which is again an element of comfort to the investors. d) With a view to incentivising the State Governments to get SDLs rated publically, the cost of RBI repo facility against the collateral of ‘rated’ SDLs have been re-calibrated to provide for lower margins on SDLs3. e) For a fair valuation of SDLs in the books of banks, it has been decided that the securities issued by each SG will henceforth be valued at the observed prices in the secondary or primary auctions. Although improvement in debt sustainability indicators have been witnessed over the years, appropriate pricing of State Development Loans (SDLs) signaling underlying financial conditions of the states will have the potential to reinforce fiscal discipline of states. All these measures are part of the top down approach. The time has come for a bottom up approach, where State Governments themselves take proactive measures which may include increasing investor engagement by holding investor meets and promote investment by local as well as foreign investors. Way Forward As the debt manager of the Government, Reserve Bank has to ensure that the financing needs of the Government is met at low cost over medium/ long-term while avoiding excessive risk. However, given the quantum increase in market borrowings, it is critical to develop a strategy by coordinating the market borrowings of Central and State Governments. i. Revamping cash management State Governments will have to relook at their cash management practices and develop expertise for monitoring and reporting cash flows and using the data to forecast cash balances with the objective of timing their respective borrowing programmes. ii. Inter-state lending borrowing State Governments have in the past been demanding, and rightly so, greater avenues to invest their surplus cash balances. Perhaps, the cash surplus SGs could lend to those in deficit at a rate linked to the market. Of course, this would need to be budgeted for. iii. Mandating investment in Consolidated Sinking Find (CSF)/ Guarantee Redemption Fund (GRF): Investment in CSF and GRF with RBI, is voluntary at present. These reserves are intended to provide a cushion to the SGs in meeting the future repayment obligations. States which maintain these funds are holding different levels of investments in terms of their outstanding liabilities. There is merit in making investments in CSF and GRF mandatory for SGs and specify a minimum threshold in terms of their outstanding liabilities to provide greater comfort to investors. To further incentivize adequate maintenance of these funds by the State Governments and to encourage them to increase the corpus of these funds, Reserve Bank has lowered the rate of interest on Special Drawing Facility (SDF) from 100 bps below the Repo Rate to 200 bps below the Repo Rate. iv. Rating of SDLs by rating agency on a standalone basis SDLs carry no credit risk, as they are sovereign and have power to impose taxes under constitution. This absence of credit risk can be seen from the fact that the risk weight assigned to holdings of SDLs by commercial banks is zero in the calculation of their CRARs under the Basel III capital regulations, similar to GOI bonds. There is no default history to assess probability of default. The states also maintain a consolidated sinking fund (CSF) with RBI to provide a cushion for amortization of market borrowing/liabilities. Having CSF and GRF gives states and investors comfort that SDL payments will be made in all circumstances. On the other hand, risk needs to be looked into in its totality. An index measuring debt sustainability and fiscal prudence performance indicators could be attempted to measure state government performance. Fiscally strong SGs can take the initiative to get themselves rated on such parameters from approved standalone rating agencies and make them public. This may help them to get better rates in auctions of their bonds. Such exercise would act as an incentive for states to perform better. To incentivize adoption of public ratings by the State Governments for SDLs, recently the Reserve Bank has decided that the initial margin requirement under LAF for rated SDLs shall be set at 1.0 per cent lower than that of other SDLs for the same maturity buckets. The public disclosure of SG ratings may also help in price differentiation of SDLs. v. Robust calendar While the Central Government is known to adhere to the borrowing calendar published every half year (HY), the SGs do not adhere to their quarterly calendars. Such deviations leave the market to second guess their market borrowing. Communication to the market as well as predictability is critical for credibility of the borrowing programme. vi. Consolidation of debt The maturity pattern of SDLs indicates that the redemption pressure would start increasing from 2022-23 and would continue to do so till 2026-27. The upsurge in redemption necessitates consolidation of debt. Each State Government will have to plan reissuances, buyback and switches based on their respective maturity profiles and cash flows. This will help create volumes, facilitate trading in the secondary market and benefit SGs by lowering yields. Additionally, it will also even out redemption pressures and elongate the residual maturity of securities. Due to efforts of Reserve Bank, several states have started reissuing SDL. We are also working with states on debt buy-backs and will take this process forward. vii. Improved and timely disclosure of information: FRBM legislations have significantly improved budget reporting, debt and fiscal data of states is not readily available. With a view to improve transparency and facilitate investors in taking informed investment decisions, there is a need to provide high frequency data on State finances in public domain. Transparency includes having an independent audit of sub-national financial accounts, making periodic public disclosures of key fiscal data, exposing hidden liabilities, and moving off-budget liabilities on budget. Conclusion: Development and reforms are a continuous process. During the new millennium, State Governments have taken several steps to improve fiscal and debt management. All the State Governments have enacted their Fiscal Responsibility Legislations incorporating the fiscal consolidation path. Therefore, an institutional commitment to fiscal prudence exists. The traditional debt sustainability indicators are on a reasonably strong footing. There may not be any significant systemic risk on account of states’ public debt. However, during the recent past there are indications of fiscal slippage. Rising deficits and borrowings of states with low liquidity and shallow investor base have macro-economic implications. Hence, it is important for all the stake holders to take measures as discussed above. I would urge market participants to utilize the SDL data being published by RBI to take informed investment decision and also encourage participation of other investors including FPIs in SDLs. Economic and social welfare of citizens is dependent on effective fiscal and debt management by the states. Building robust SDL markets and augmenting debt management systems in states to take care of emergent risks, is both imperative and urgent. Reserve Bank has been working actively with State Governments to achieve this objective. I would urge market participants also to play an active role in this endeavour. Thank You. 1 Inputs received from Internal Debt Management Department and Shri Rajendra Kumar, General Manager are acknowledged. 2 The gross amount borrowed by States during 2007-08 was more than twice the amount raised in the previous year as States were sanctioned additional allocations by the Centre to meet the shortfall in National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) collections during 2007-08. 3 The initial margin requirement for rated SDLs shall be set at 1.0 per cent lower than that of other SDLs for the same maturity buckets, i.e., in the range of 1.5 per cent to 5.0 per cent. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ਪੇਜ ਅੰਤਿਮ ਅੱਪਡੇਟ ਦੀ ਤਾਰੀਖ: