IST,

IST,

|

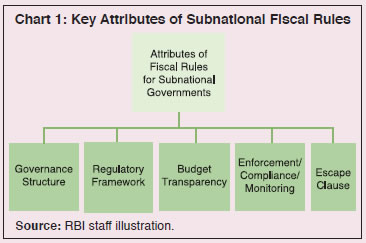

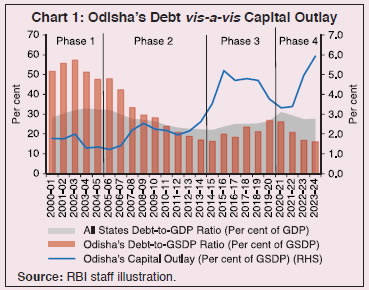

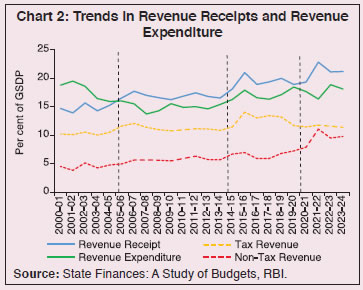

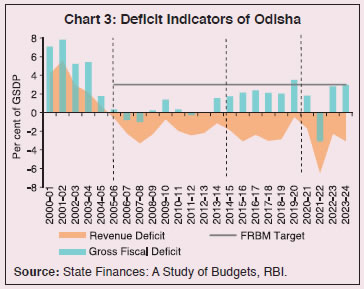

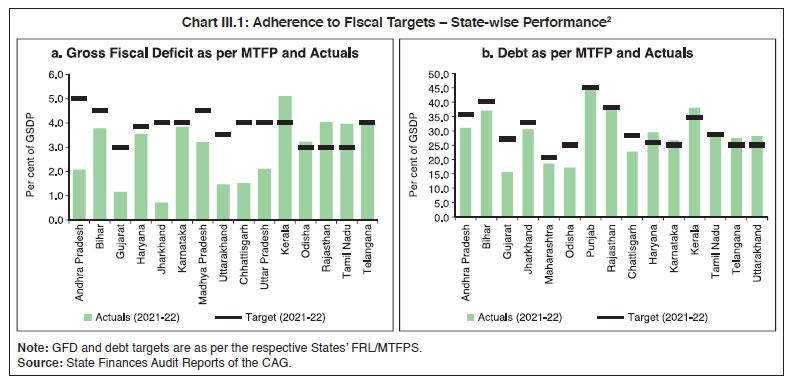

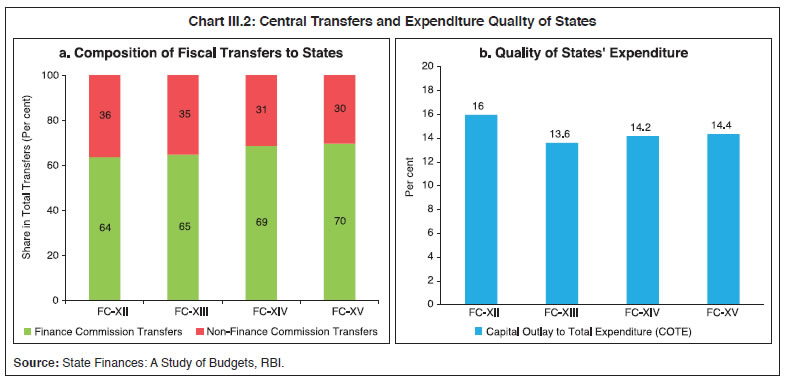

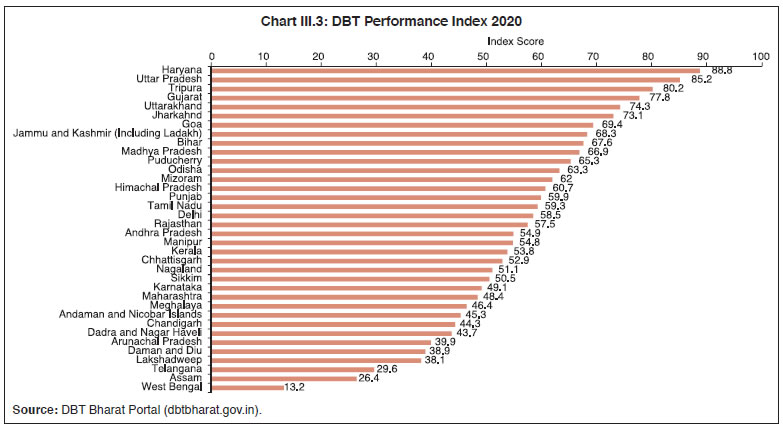

State-specific Fiscal Responsibility Legislations (FRLs) have established a foundation for prudent fiscal management across States over the past two decades. The introduction of direct benefit transfers, adoption of the national pension system and implementation of GST have also contributed to improving their finances. The health of State-owned electricity distribution companies remains a stress point. Future reforms in subnational finances can include adoption of a risk-based fiscal framework; provisions for counter-cyclical fiscal policy actions; a medium-term expenditure framework incorporating the ‘golden rule’ for government spending; and enhanced data dissemination and communication policies. 1. Introduction 3.1 The enactment of Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Acts/ Fiscal Responsibility Legislations (FRLs) by States paved the way for sub-national fiscal consolidation, starting 2004-05. It complemented the provision of debt and interest relief to States by the Central government. Since then the States have followed a series of reforms aimed at improving the sustainability, efficiency, and transparency of their finances. An assessment of these fiscal reforms is the theme of this chapter. Section 2 examines the performance of States in terms of adherence to fiscal rules. Section 3 highlights the major institutional reforms, followed by expenditure and tax reforms in Sections 4 and 5, respectively. Section 6 focuses on the reforms in financing patterns. Challenges encountered in the power sector are discussed in Section 7, while the agenda for future reforms is set out in Section 8. Section 9 puts forth concluding observations. 2. Review of Sub-national Fiscal Rules 3.2 Fiscal rules facilitate prudent fiscal management by bringing discipline in the conduct of public finances (Akin et al., 2017). Following the FRBM Act of 2003 by the Government of India, the States adopted their respective FRLs with the objective of designing and implementing a rule-based fiscal management system. The implementation of FRLs has incentivised formulation of fiscal policy strategies, creation of Medium-Term Fiscal Plans (MTFPs) and improvement in transparency. States have amended their FRLs periodically to adapt to changing needs. 3.3 Fiscal rules can be classified into four broad categories, based on the fiscal variables these rules impinge upon (Schaechter et al., 2012; Bova et al., 2015). The Budget Balance Rules (BBRs) aim at targeting either the overall fiscal balance or the cyclically adjusted fiscal balance. Debt rules set ceilings for public debt-to-GDP ratios. Expenditure rules restrict total or specific government spending. Revenue rules aim to control revenue through taxation limits or by ensuring minimum receipts. The FRBM Act of the Centre and FRLs of the States follow a deficit rule and set a debt-to-GDP ratio target. 2.1 Fiscal Management Principles 3.4 Internationally accepted fiscal management principles incorporate the features of transparency, stability, responsibility, fairness, and efficiency at their core. Transparency ensures clear policy objectives and access to information by public. Stability involves predictable policymaking and some certainty around its economic impact. Responsibility emphasises integrity in budget formulation and public finance management. Fairness considers financial implications for future generations, and efficiency pertains to the effective design and implementation of fiscal policy and asset/liability management (RBI, 2005). 3.5 Containing the fiscal deficit and revenue deficit within prescribed limits, maintaining the debt stock at a sustainable level, using borrowed funds for productive use and capping guarantees within an indicative ceiling are some of the fiscal management principles adopted by the States’ FRLs. The associated rules also require three documents to be laid before the legislatures at the time of presentation of the State budget: (i) Macro-economic Framework Statement containing an overview of the State economy, an analysis of growth and sectoral composition of GSDP, and an assessment related to State government finances and future prospects; (ii) Medium Term Fiscal Policy (MTFP) Statement, outlining the State government’s fiscal goals and three-year rolling targets, covering revenue-expenditure balance, use of capital receipts for productive assets, and estimated pension liabilities for the next ten years; and (iii) Fiscal Policy Strategy Statement covering the State’s fiscal policies for the upcoming year relating to taxation, expenditure, borrowings and other liabilities. The States’ FRLs also entail that the document should highlight strategic fiscal priorities; key fiscal measures; reasons for any significant deviations in policies related to taxation, subsidies, and expenditures; and provide an evaluation of current policies against the fiscal management principles. Currently, these Statements are disseminated by most of the major States either on their finance department websites or on other public platforms (Table III.1). 3.6 A review of the outcomes vis-à-vis the rolling targets specified in the MTFP Statements/ FRL Acts indicates that ten and nine major States could successfully achieve their fiscal deficit and debt ceiling goals, respectively, in 2021-22 (Chart III.1). Following the recommendation of the FRBM Review Committee (2017), the Finance Act, 2018, amended the Centre’s FRBM Act (2003) to set up well-defined escape clauses, which could be invoked only in the cases of (a) national security concerns, acts of war, major disasters, and significant agricultural collapse; (b) substantial structural reforms leading to unforeseen fiscal impacts; and (c) a decline in real output growth of at least 3 percentage points below the average of the previous four quarters (Datta et al., 2023). Subsequently, most major States invoked such escape clauses in their FRLs in the aftermath of the pandemic (Table III.1).

2.2 Fiscal Transparency Principles 3.7 Fiscal transparency promotes government accountability and trust among stakeholders (Kopits and Craig, 1998). It boosts budget credibility and reliability by making budget information accessible (Sarr, 2015; Jena and Sikdar, 2019). Public scrutiny of available information enhances market confidence, prevents mismanagement and diversion of public funds, improves policy effectiveness, and encourages public engagement in budget processes, ultimately resulting in fiscal discipline, stability, and sustainable economic growth. 3.8 The Advisory Group on Fiscal Transparency (2001) recognised that State-level fiscal transparency in India lagged that of the Central government. Following its recommendation of minimum transparency standards, most of the States publish a document titled ‘Budget at a Glance’. The transparency measures enunciated in the Model FRL Act (RBI, 2005) require State governments to promote the disclosure of fiscal data such as any significant changes in accounting standards, policies and practices which are affecting or have the potential to affect the computation of fiscal indicators. A review of States’ FRL documents reveals that Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha and Rajasthan explicitly report these disclosures in their budget documents.3 3.9 As a part of transparency measures, a few States have legislated the disclosure of estimated pension liabilities for the next ten years worked out on an actuarial basis to assess their likely pension burden, mode of financing and impact on deficit indicators. Currently, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Rajasthan are disclosing such information.4 The disclosure of other sensitive information like contingent liabilities, off-budget borrowings, and employee details lack uniformity across States. 3.10 State governments resort to supplementary grants when expenditures under specific heads are anticipated to surpass the initially appropriated amounts. Most of the State FRLs stipulate disclosure of supplementary estimates on grants, and a review reveals that most States are compliant with this stipulation. The actual utilisation of these supplementary grants have been often short of the estimate, according to the CAG.5 2.3 Fiscal Marksmanship 3.11 Fiscal marksmanship examines the degree of correspondence between budgeted projections and the actual outcome of key fiscal indicators (Chakraborty, et al. 2020). The discrepancies between budgeted and actual numbers can reflect errors in assumptions or the occurrence of unexpected events. For State governments in India, poor fiscal marksmanship has been observed for the broader components of receipts and expenditures (Jena and Singh, 2021; Chakraborty et al., 2020). 3.12 The Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) framework can be used to evaluate the budgets of State governments. Established in 2001 by seven international development partners – the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the governments of France, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom – the PEFA programme provides a standardised methodology and reference tool for Public Financial Management (PFM) diagnostic assessments. Among the 31 performance indicators encompassing a wide range of PFM activities grouped under seven pillars in the PEFA framework, those pertaining to Budget Reliability and Transparency of Public Finances are particularly relevant for this analysis (Table III.2 and Annex Table III.1). 3.13 Data spanning 20 major States focusing on key components of receipts and expenditure across two distinct periods – 2016-17 to 2018-19 (Period I) and 2019-20 to 2021-2022 (Period II) are evaluated for budget credibility using the PEFA framework. For overall revenue receipts, while three and five States could achieve “A” and “B” scores, respectively, in Period I, none of them could achieve “A” or “B” scores in Period II. The deterioration in budget forecasts could reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity and thereby on the finances of the States. Correspondingly, the number of States with “D” score increased from 11 in Period I to 16 in Period II (Table III.3). Component-wise, for States Goods and Services Tax (SGST) – the largest source of States’ own tax revenue – only three States received a “B” score while the remaining States received a “D” score in Period II. Among the other components, the number of States with a “D” score declined in Period II for stamp duty and registration fees; sales tax; and grants from the Centre. In contrast, the number of States with “D” scores increased for excise duties and non-tax revenue during this period. Apart from the economic uncertainty associated with the pandemic, deviations from budget estimates often result from volatility in Central transfers, impaired State budgeting mechanisms, insufficient staff and resources, and infrastructural bottlenecks at the departmental level (Srinivasan and Misra, 2021; Acharya and Bose, 2020).

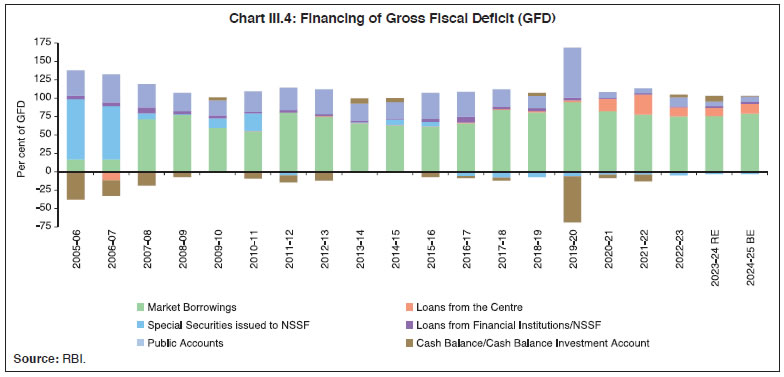

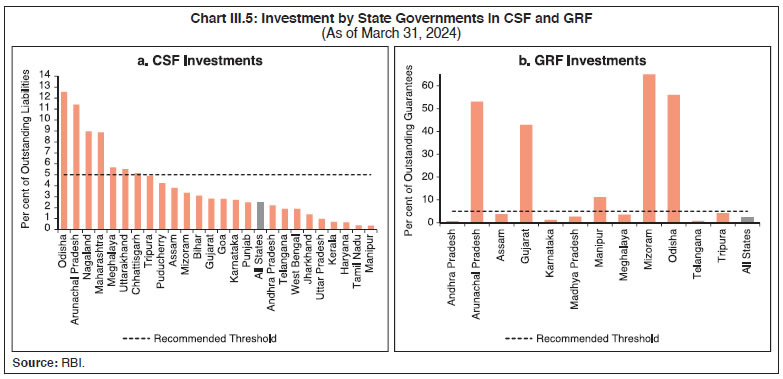

3.14 The forecast deviations in States’ revenues can, in turn, impinge upon their actual expenditures relative to budget estimates (Jena, 2006). This effect is observed in revenue expenditure across several major sectors such as urban development, agriculture and allied activities, rural development and energy, with numerous States generally in category “D” in both the periods (Table III.4). The notable exceptions are medical and public health, social security and welfare, with an increasing number of States having improved their expenditure predictability in Period II compared to Period I. 3.15 For capital outlay, the number of States with “A” and “B” scores declined from Period I to Period II (Table III.5). In Period II, the number of States with a “D” score is much higher at 13 for capital outlay as against only four for revenue expenditure, suggesting that capital expenditure is often compromised in the face of shortfalls to comply with the fiscal rules. In addition, programme management and structural bottlenecks often hinder budget implementation and spending during the year (Saha and James, 2022). Within capital expenditure, there is a deterioration in fiscal marksmanship, as reflected by “D” scores in Period II, in almost all the areas except energy. 2.4 Enforcement of Compliance 3.16 To comply with fiscal policy rules, the FRLs of most of the States have a provision for disclosing an annual report detailing outcomes compared to targets, in line with the recommendations of the Group on Model Fiscal Responsibility Legislation at the State Level (RBI, 2005). Additionally, most State FRLs specify the release of monthly/ quarterly/half-yearly outcome reports which review the trends in receipts and expenditure in relation to the budget estimates. In case of non-achievement of targets, States are mandated to elicit the remedial measures required. These compliance reports are required to be placed before the State Legislature by the Minister in charge of Finance at specified intervals. At present, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu are releasing such review reports.6 In addition, some States have stipulated the constitution of an independent agency to monitor the compliance of the provisions of FRL. States like Karnataka, Kerala, Rajasthan and West Bengal have legislated the constitution of a Public Expenditure Review Committee to submit independent review reports.7, 8 3.17 Institutional reforms have been pivotal in transforming India’s fiscal landscape. By reshaping Centre-State fiscal relations and governance structures, these reforms have empowered States to manage public finances more effectively and tailor development strategies to their unique needs. Key among these changes are the establishment of the NITI Aayog and the creation of State Institutions for Transformation (SITs). 3.1 Constitution of NITI Aayog 3.18 The Planning Commission, established in 1950, was replaced by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) in 2015. The NITI Aayog, unlike its predecessor, does not have resource allocation as part of its mandate. The role of intermediation of Annual Plans and transfer of Plan funds to State governments has now been conferred on the Ministry of Finance. NITI Aayog has a twin mandate: (i) to oversee the adoption and monitoring of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the country; and (ii) to promote competitive and cooperative federalism among States and UTs to align the policies and schemes of Central and State governments in these sectors. 3.2 Setting up of State Institutions of Transformation 3.19 State governments play a major role in creating an enabling environment for sustainable and inclusive growth. Levers of development like health, education, skill building, infrastructure, land administration and urbanisation are primarily driven by State governments. State Support Mission, an umbrella initiative by NITI Aayog, aims at fostering structured and institutionalised engagement with States and UTs to assist them in achieving socioeconomic goals by 2047. The mission has been strategically designed to support States/UTs in developing a roadmap aligned with national priorities and their core strengths (NITI Aayog, 2023). One of the critical components of the State Support Mission is to set up State Institutions for Transformation (SITs), where States/UTs can either establish new SITs or reconfigure existing institutions with support from NITI Aayog, including setting up bodies to replace their planning boards. So far, the NITI Aayog has collaborated with seven State governments – Assam, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand – to establish SITs tailored to meet the specific needs of each State (Annex Table III.2). They will play a pivotal role in fostering partnerships, mobilising resources, generating ideas, and creating synergies for the States to realise their goals. 3.3 Changing Dynamics of Transfers to States 3.20 After the abolition of the Planning Commission, the channel of central funding to the States was confined to Finance Commission transfers and Central grants through various Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) administered by Central ministries. In order to compensate the States after the cessation of plan grants, the 14th Finance Commission (FC-XIV) raised the vertical share of taxes to 42 per cent from 32 per cent recommended by the 13th Finance Commission (FC-XIII), thus making tax devolution the primary vehicle for federal transfers. It was expected that the increase in unconditional transfers would provide adequate flexibility to the States to spend as per their needs, thus furthering fiscal federalism and conferring more fiscal autonomy on States. Accordingly, the average share of Finance Commission transfers9 in total Central transfers increased from 65 per cent in the period of FC-XIII to 70 per cent in the period of FC-XV (2020-21 to 2024-25) (Chart III.2a). During the same period, there has been an improvement in the quality of States’ expenditure (Chart III.2b). 3.21 One of the main pillars of fiscal reforms by States is expenditure rationalisation aimed at reducing unproductive expenditure and channelising resources to the priority areas.  4.1 Introduction of Direct Benefit Transfer 3.22 Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) – the system of delivering welfare benefits directly to the targeted beneficiaries – was originally envisaged in 2013 under which welfare benefits were directly credited to the bank or postal accounts of the accurately identified targeted beneficiaries in 43 districts for 24 Central schemes (GoI, 2013). The full potential of DBT was unleashed with the JAM Trinity – Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and Mobile – leveraging digital public infrastructure to directly transfer the benefits and social security payments of various government schemes to the bank account of the intended beneficiary (GoI, 2016). 3.23 State governments have also started disbursing benefits under their exclusive schemes through DBT (Annex Table III.3). Over the years, DBT has been applied to more than 2,000 schemes at the State level. States have leveraged DBT and other governance reforms to remove duplicate/fake beneficiaries and plug leakages. In Uttar Pradesh, DBT has been used to pay sugarcane prices to eligible farmers. States like Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are implementing Rythu Bandhu and Rythu Bharosa schemes, respectively, for farmers through DBT. Odisha’s Krushak Assistance for Livelihood and Income Augmentation (KALIA) scheme uses DBT to provide financial assistance to needy farmers to carry forward cultivation activities. Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh are using the DBT route to implement various State government pension schemes. States like Gujarat, Maharashtra and Uttarakhand have adopted DBT for the disbursement of scholarships to students through online mode. In addition, almost all States are using the DBT route to deliver welfare benefits to women and girls under various schemes. The DBT Mission of the Government of India monitors and evaluates the performance of various States and UTs. States were assigned DBT scores, based on their performance on parameters like Aadhaar saturation, data reporting, savings-expenditure ratio and DBT per capita (Chart III.3).  3.24 DBT has generated significant monetary savings for State governments by reducing corruption, duplication, and leakages. For the beneficiaries, the expansion of DBT and integration with UPI has reduced delays in payments, empowered individuals and ensured higher consumption standards. DBT played an important role in extending financial support to vulnerable sections of society like small farmers, unorganised sector workers, migrant labour, women, and senior citizens during the pandemic. The DBT scheme is regarded as a ‘logistical marvel’ that has helped vulnerable sections (Caselli et al., 2022). DBT has the potential to provide social security or universal basic income, financially empower women and reduce subsidy leakages in public programs (Saini et al., 2017; Sabharwal et al., 2019; and Barnwal, 2016). 4.2 Pension Reforms 3.25 India’s pension reforms initiated in the 2000s led to the adoption of the National Pension System (NPS) – a defined contribution (DC) scheme – replacing the Old Pension Scheme (OPS) – a defined benefit (DB) plan by the Central and State governments. The OPS required pensions to be paid from current government revenue, thus creating a substantial fiscal burden. In contrast, the NPS accumulates funds through contributions from both employees and the government, reducing the fiscal stress on State finances. In India, most of the States – except West Bengal and Tamil Nadu – have implemented the NPS. 3.26 In order to encourage States to continue with the NPS, the Centre allowed extra borrowing limits to them equivalent to employer and employee shares of contributions to the scheme for the financial year 2023-24. Overall, an extra borrowing ceiling of ₹60,877 crore was allowed to 22 States in 2023-24 for NPS contribution (GoI, 2023). 3.27 The Andhra Pradesh government introduced a Guaranteed Pension Scheme (GPS) for its employees in 2023, which is a hybrid model with features of both DB and DC plans. In this context, the recently announced Unified Pension Scheme (UPS) of the Central government for its employees retains the “funded” nature of the NPS while incorporating a guaranteed pension component. The UPS balances the demand for a guaranteed pension by employees while maintaining the sustainability of public pension plans (Table III.6). 3.28 Reforming direct and indirect taxes at the national and sub-national levels is essential for boosting tax revenues and raising the tax ratio. 5.1 Introduction of GST 3.29 The introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) was a game changer for indirect taxation in India. After prolonged deliberation between the Centre and the States for nearly two decades, the GST regime was finally implemented on July 1, 2017. The primary motive of this ‘One Nation One Tax’ proposal was to reduce the cascading effects of indirect taxation, simplify compliance procedures and promote economic integration. The current GST structure in India has four tax slabs, viz., 5, 12, 18 and 28 per cent, with a few essential commodities being exempted. A compensation mechanism was worked out under which the Central government compensated the States for any shortfall in revenue due to transition to the GST regime for an initial period of five years. 3.30 The GST has led to greater harmonisation and uniformity across States in terms of tax structure. Decisions pertaining to various aspects such as fixation of rates, exemption of certain goods and services as well as revenue sharing between States and Centre are decided by the GST Council, which comprises representatives of the Centre and States. The regime’s success in India can be attributed to the cooperative and consensus-based approach between Central and State governments. 5.2 Modernisation of Tax Administration 3.31 State governments have implemented several administrative reforms to boost the efficiency of tax collection (Annex Table III.4). These efforts include the development of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for providing online access to property guidance values, compulsory e-stamping for non-registerable documents with updates of fair values of land parcels. States have adopted digital payment systems at liquor outlets to augment revenue. Centralised GST registration cells have been established along with mandatory e-invoicing for large taxpayers. E-governance measures such as e-registration, e-filing, and e-payment have streamlined compliance and reduced costs while addressing revenue leakages. Going forward, Indian States can further refine their taxation system by adopting the international best practices as well as utilising data analytics, machine learning and artificial intelligence (Govindharaj, 2023). 3.32 The steady shift towards market borrowings constitutes the most important reforms of financing of States in the last two decades. The share of market borrowings in the financing of GFD increased from a modest 17 per cent in 2005-06 to 79.0 per cent in 2024-25 (BE) (Chart III.4). The share of market borrowings peaked at 95 per cent of States’ deficit funding in 2019-20 but has since moderated due to an increase in the share of loans from the Centre in lieu of GST compensation and special assistance for capital expenditure. 3.33 For short-term cash management, the States continue to depend on financial accommodation provided by the Reserve Bank through ways and means advances (WMA), overdrafts (OD) and the special drawing facility (SDF) (Table III.7). 3.34 States are allowed to avail SDF against their net incremental annual investments in the Consolidated Sinking Fund (CSF) and the Guarantee Redemption Fund (GRF). Many of the States still need to catch up to the 5 per cent CSF threshold of their total outstanding liabilities suggested by the Working Group on State Government Guarantees (2024)10 (Chart III.5a).   Similarly, some major States have GRFs below the recommended threshold level of 5 per cent of outstanding guarantees (Chart III.5b). 3.35 The weak financial health of State-owned electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs) constitutes a persisting challenge for State government finances. Despite multiple financial restructuring efforts, DISCOMs’ total outstanding debt has grown at an average annual rate of 8.7 per cent since 2016-17, rising from ₹4.2 lakh crore to ₹6.8 lakh crore in 2022-23 (2.5 per cent of GDP) (Power Finance Corporation, 2024) (Chart III.6).  3.36 State governments provide considerable support to DISCOMs through revenue subsidies, grants, and equity infusions, as well as by taking over annual losses. The recurrent need for bailouts of loss-making DISCOMs diverts valuable resources that could otherwise be invested in developmental initiatives. For instance, the Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana (UDAY) required State governments to absorb 75 per cent of the DISCOM debt - 50 per cent in 2015-16 and 25 per cent in 2016-17. The implementation of the UDAY scheme by 16 States led to a sharp rise in their fiscal deficits, outstanding debt, and interest payments in 2015-16 and 2016-17 (Mishra et al., 2020). 3.37 The fifteenth finance commission allowed an additional borrowing space of 0.5 per cent of GSDP for States which would take up power sector reforms to enhance operational and economic efficiency to promote a sustained increase in paid electricity consumption. These reforms included reduction in: (i) operational losses; (ii) revenue gap; (iii) payment of cash subsidy by adopting direct benefit transfer; and (iv) tariff subsidy as a percentage of revenue. In 2021-22, twelve States were permitted to borrow ₹39,175 crore based on the stipulated reform criteria. In 2022-23, six states were allowed to borrow ₹27,238 crore. In 2023-24, States were eligible to borrow approximately ₹1,43,332 crore, as recommended by the Ministry of Power (GoI, 2023). States need to prioritise operational efficiency by minimising distribution losses, improving metering systems, ensuring timely tariff revisions, and incentivising the power sector to gradually reduce reliance on government subsidies. 3.38 While the implementation of FRLs has led to significant consolidation of debt and deficit indicators of States in the last two decades, there is scope for further improvement and refinement. First, some space for counter-cyclical fiscal policy could be considered in order to provide flexibility in the face of large exogenous shocks (IMF, 2022; Akin et al., 2017). A risk-based fiscal framework that considers state-level fundamentals may be more productive in achieving fiscal consolidation than a uniform approach. For instance, States with higher debt levels and slower growth rates may require stricter fiscal rules than States with lower debt levels (Chinoy, 2024). 3.39 Second, for better expenditure planning, the States could adopt a Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) which links policymaking to budgeting by ensuring forward planning for fund availability and improving accountability (World Bank, 1998; Jena and Sikdar, 2019). Successful implementation of the ‘golden rule’, which requires that all current/revenue expenditures be financed from current revenue while capital expenditure is financed through borrowings, saw States achieving a revenue surplus in 2007-08 (Rao, 2018). Revisiting the ‘golden rule’ of public finance could ensure that capital expenditure is not compromised while States adhere to FRL targets. 3.40 Third, the enforcement mechanism can be made stronger through provisions of sanctions and penalties (Box III.1). 3.41 Fourth, recent economic, climatic and geopolitical uncertainties have exacerbated the fiscal risks, leading to large divergences of actual revenues and expenditures from the budgeted estimates. State governments need to regularly carry out an assessment of potential fiscal risks arising out of macroeconomic uncertainties, pension liabilities, unfinished or delayed Public Private Partnership projects, and contingent liabilities. The potential economic damage to critical infrastructure arising out of environmental phenomena like growing heatwaves, flooding and episodes of recurring cyclones should be regularly assessed and disclosed through a Fiscal Risk Statement as practiced by the government of Odisha (Box III.2).11

3.42 Fifth, data transparency deserves more attention in the years ahead. State governments could consider reporting of the assumptions underlying the budget estimates and medium-term fiscal targets, including assumptions regarding GSDP growth and elasticities of taxes, along with an analysis of the deviation of past estimates with the actuals. In addition, the States may disclose critical information on emerging areas like their expenditures on climate adaptation and mitigation, and research and development. Transparency on the projections for pension liabilities along with the number of employees has assumed importance in the recent period. Disclosure of information on transfers to urban and rural local bodies would aid an improved understanding of local government finances. 3.43 Sixth, there is scope for expansion of institutional coverage of State government data. Currently, data on finances of various State government-owned entities and parastatal bodies are scarce, with only a handful of States occasionally releasing partial information. States could release an annual survey on the financial position of State-owned entities, State public sector enterprises, and entities funded by the States. 3.44 Finally, comprehensive and up to date information on State governments’ policies and actions should be easily accessible to all users through an appropriate data dissemination and communication policy. States may leverage social media for better reach to citizens and for garnering feedback and public sentiments. 3.45 A review of fiscal reforms during the last two decades at the subnational level reveals a mixed picture of progress and challenges. The implementation of State-specific FRLs has established a foundation for prudent fiscal management and fiscal stability across States. Major expenditure reforms like the introduction of DBT have generated significant savings for State governments over time while also improving the delivery of benefits by reducing corruption, duplication, and leakages. Pension reform like the adoption of NPS has mitigated the risk of unfunded liabilities. The successful implementation of GST has strengthened the spirit of cooperative federalism in India. On the other hand, the weak financial health of the State-owned electricity distribution companies remains a stress point for State government finances. States need to prioritise operational efficiency and incentivise the power sector to gradually reduce the reliance on government subsidies. 3.46 Subnational finances can be strengthened through a risk-based fiscal framework with a provision for counter-cyclical fiscal policy actions subject to well-defined escape clauses and adoption of a medium-term expenditure framework incorporating the ‘golden rule’ for government spending. Independent monitoring of fiscal management of States; enhanced assessment and disclosure of fiscal risks; expansion of institutional coverage of State government data; and formulation of an appropriate data dissemination and communication policy are other deliverables which can strengthen their fiscal frameworks. 1 These States are releasing their FRL documents along with year-wise Budget documents. The North-eastern States and the UTs of Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi and Puducherry are excluded from this analysis. 2 As recommended by the 15th Finance Commission, the net borrowing ceiling for the States was set at 4.5 per cent of GSDP for the year 2021-22 to compensate for the pandemic induced loss of tax revenues. 3 Maharashtra, Odisha and Rajasthan report even if there are no changes in accounting standards, policies, and practices. Karnataka reports when there is a change in policy stance. 4 Gujarat reports number of pensioners and expenditure on pensions. 5 Information availed from several States’ State Finance Audited Reports from CAG. 6 Odisha publishes monthly fiscal report. 7 Karnataka has legislated the constitution of a Fiscal Management Review Committee. 8 Even without specific mandate, the Principal Accountant General and the Accountant General have consistently reported on the State Governments’ adherence to the Act’s provisions in the State Finances Audit Report (Volume-III Governmental Perspective – Centre & States, FRBM Review committee 2017). Accessible at: https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Volume-3%20Centre%20%26%20States.pdf. 9 Finance Commission transfers include tax devolution and statutory grants under Article 275 of the Indian Constitution. 10 Report of the Working Group on State Government Guarantees, Accessible at: https://rbi.org.in/web/rbi/-/publications/reportsreport-of-the-working-group-on-state-government-guarantees. 11 Accessible at: https://finance.odisha.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-02/Fiscal%20Risk_0.pdf. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

கடைசியாக புதுப்பிக்கப்பட்ட பக்கம்: