8.1 The financial services industry, particularly the banking industry, has undergone significant transformation all over the world since the early 1980s under the impact of technological advances, deregulation and globalisation. An important aspect of this process has been consolidation as a large number of banks have been merged, amalgamated or restructured. Although the process of consolidation began in the 1980s, it accelerated in the 1990s when macroeconomic pressures and banking crises forced the banking industry to alter its business strategies and the regulators to deregulate the banking sector at the national level and open up financial markets to foreign competition. This led to the blurring of distinctions between banks and non-bank financial institutions, various products and the geographical locations of financial institutions. The resulting competitive pressures on banks in the emerging economies led to deep changes in the structure of the banking industry, including, among others, privatisation of state-owned banks, mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and increased presence of foreign banks. The financial value involved in the M&As multiplied over the years. As a result of these M&As, the number of banks has declined substantially both in advanced and emerging market economies (EMEs).

8.2 The motives of consolidation have depended on firm characteristics such as size or organisational structure across segments, or even across lines of business within a segment (BIS, 2001). In developed countries, market forces have been the prime driving force behind M&As. Globalisation and deregulation led to decline in bank spreads, and consequently, profitability. In order to offset the decline in profitability, there were mergers between banks and between banks and non-banks to reap the benefit of economies of scale and scope. On the other hand, in many EMEs, mergers and amalgamations have often been driven by governments in order to restructure the banking systems in the aftermath of crisis.

8.3 Financial consolidation has implications not only for competition but also for financial stability, monetary policy, efficiency of financial institutions, credit flows and payment and settlement systems. Given the diverse nature of financial institutions, different levels of financial development, legal framework and other enabling environment, the causes and impact of financial consolidation have also tended to vary across the countries. For instance, financial consolidation led to higher concentration in countries such as US and Japan, though they continue to have much more competitive banking systems as compared with other countries. However, in several other countries, the process of consolidation led to decline in banking concentration, reflecting increase in competition. This was mainly because banks involved in M&As were of relatively small in size.

8.4 The Indian banking sector has not remained insulated from the global forces driving M&As across the countries. M&A activity in the Indian banking sector is not something new as it took place even before the independence. However, economic reforms introduced in the early 1990s brought out a comprehensive change in the business strategy of banks, whereby they resorted to mergers and amalgamations to enhance size and efficiency to gain competitive strength.

8.5 Against the above backdrop, this chapter, drawing on the theoretical perspective and country experiences on consolidation and competition, assesses various aspects of consolidation and competition in the Indian banking sector. The focus of the chapter is to examine the extent and nature of the process of consolidation and its impact on competition in the banking sector and efficiency of the merged entities. Some important issues that have arisen in the process of ongoing consolidation process have also been discussed. The chapter is organised into eight sections. Section II briefly sets out the theoretical underpinnings of the banking consolidation process. It also spells out the motives and factors driving M&As and the various methods of consolidation. Trends in M&A activity in various countries and the progress in banking consolidation in India are detailed in Section III and Section IV, respectively. The impact of the consolidation process on competition in the Indian banking sector and efficiency of the merged entities is analysed in section V. Section VI addresses the issues arising out of the ongoing process of competition and consolidation such as (a) future course of the process of consolidation that is underway; (b) role of public sector banks in the changed economic environment; (c) further opening the banking sector to foreign competition; and (d) combining of banking and commerce. Section VII makes some suggestions as a way forward, while Section VIII sums up the main points of discussion.

II. CONSOLIDATION – THEORETICAL

UNDERPINNINGS

8.6 There are several alternative methods of consolidation with each method having its own strengths and weaknesses, depending on the given situation. However, the most commonly adopted method of consolidation by firms has been through M&As. Though both mergers and acquisitions lead to two formerly independent firms becoming a commonly controlled entity, there are subtle differences between the two. While acquisition refers to acquiring control of one corporation by another, merger is a particular type of acquisition that results in a combination of both the assets and liabilities of acquired and acquiring firms (Halperin and Bell, 1992; and Ross et al.,1995). In a merger, only one organisation survives and the other goes out of existence. There are also ways to acquire a firm other than a merger such as stock acquisition or asset acquisition.

8.7 Mergers generally take place in three major forms, viz., horizontal merger, vertical merger and conglomerate merger. Horizontal merger is a combination of two or more firms in the same area of business. Vertical merger is a combination of two or more firms involved in different stages of production or distribution of the same product, and can be either forward or backward merger. When a company combines with the supplier of material, it is called backward merger, and when it combines with the customer, it is known as forward merger. Conglomerate merger is a combination of firms engaged in unrelated lines of business activity.

8.8 M&As in the financial sector, in particular the banking sector, are undertaken mainly either to maximise the value of firms or for personal interest of managers. As is the case with any firm, the value of a financial institution is determined by the present discounted value of expected future profits. Mergers can increase expected future profits either by reducing expected costs or by increasing expected revenues or a combination of both. Cost reduction through M&As could arise for several reasons including economies of scale, economies of scope, infusing efficient management, reduction and diversification of risk due to geographic or product diversification, access to capital markets or a higher credit rating because of increased size, and entry into new geographical or product markets at a lower cost than that associated with de novo entry. M&As could also enable banks to make the provision of additional services making them capable of facing competition from larger banks. By this way, mergers can also lead to increase in revenue by allowing larger size firms to better serve large customers, offering “one-stop shopping” for a variety of different products, increased product or geographical diversification, leading to expanded pool of potential customers and enhancing the risk-taking abilities. M&As could also be used as a deterrent against unwanted possible acquisitions, particularly hostile takeovers, by other larger banks in the future.

8.9 Managers’ actions and decisions, however, are not always consistent with the maximisation of a firms’ value. In particular, when the identities of owners and managers differ and capital markets are less than perfect, managers may take actions that further their own personal goals and are not in the interests of the firm’s owners. In some cases, managers may get engaged in consolidation simply to enhance their firms’ size relative to competitors.

8.10 Deregulation, improvements in information technology, globalisation, shareholders’ pressures and accumulation of excess capacity or financial distress have been some of the important factors that have encouraged consolidation of financial institutions. While new technologies embody high fixed costs, they enable provision of a broad array of products and services to a large number of clients over wider geographical areas at faster pace and quality of communications and information processing. In other words, it confers economies of scale by spreading the high fixed costs across a larger customer base and motivates mergers of firms operating at uneconomical scales. Further, new tools of financial engineering such as derivative contracts, off-balance sheet guarantees and risk management may be more efficiently produced by large institutions. Some new delivery methods for depositors’ services such as phone centers, ATMs and on-line banking networks may also exhibit greater economies of scale than traditional branching networks (Radecki et al., 1997).

8.11 Deregulation influences the restructuring process in banking through effects on market competition and entry conditions, approval/ disapproval decisions for individual merger transactions, limits on the range of permissible activities for service providers, through public ownership of institutions and efforts to minimise the social costs of failures. Over the past two decades, as a response to technological advances and financial crises, governments, after reconsidering the legal and regulatory framework in which financial institutions operate, have relaxed many official barriers to consolidation. This has resulted in accelerated pace of M&As in the financial sector. At the same time, ceilings on interest and deposit rates have been removed leading to narrowing of interest rate spreads of banks. M&As wave has also been a response to increased competition that threatened profits. To offset the impact of decline in bank spreads on profitability, banks responded by expanding volume (economies of scale) and diversifying their activities (economies of scope). The removal of restriction on geographical areas for banking operations and on diversification of activities provided the opportunities for banks to consolidate among themselves and non-bank financial firms.

8.12 Globalisation, which is a by-product of technology and deregulation in many respects, has its bearing on economies of scale and consequently, influences consolidation strongly among the firms engaged in the provision of wholesale financial services. M&As have also been a frequent option for banks seeking to build a global retail system. It is felt that by acquiring an existing institution in the target market, the acquirer gains a more rapid foothold than would be possible with an organic growth strategy.

8.13 Increased access to the capital markets, both domestic and international, has increased the importance of shareholders relative to other stakeholders. On the other hand, increased competition has led to squeeze in the profit margins of financial firms, resulting in shareholders’ pressure to improve performance. Financial firms have been adopting a simpler strategy of M&As to improve performance instead of achieving the same through business gains, productivity enhancement or more effective balance sheet management.

8.14 When there exist excess capacity in an industry or local market, firms, for several reasons, are rendered inefficient as they operate below the optimum level or below the efficient frontier of production. Consolidation through M&As can solve these inefficiency problems more effectively than bankruptcy or other means of exit by preserving the pre-existing franchise value of the merging firms. Similarly, consolidation is employed as an efficient way of resolving problems of financial distress, with weak or inefficient firms being taken over by stronger ones. In short, mergers of banks may help reduce the gestation period for launching/promoting new businesses, strengthen the product portfolios, minimise duplication, and gain competitive advantage, among others. They are also recognised as a good strategy for enhancing efficiency. Ideally, mergers should be aimed at exploiting synergies, reducing overlap in operations, right-sizing and redeploying surplus staff either by retraining, labour restructuring or voluntary retirement.

8.15 Consolidation in the banking industry, on the other hand, can be impeded by regulations, differences in corporate culture and governance regime and inadequate information flows. The legal and regulatory environment represents a substantial potential impediment for consolidation in the banking industry, as it directly affects the range of permissible activities undertaken by financial firms. In some countries, antitrust laws constitute an important impediment, mainly for domestic consolidation within sectors. Prudential regulation may hinder cross-border consolidation through differences in capital requirements. Regulatory impediments to consolidation include protection of national champions, government ownership of financial institutions, competition policies and rules on confidentiality.

8.16 The differences in corporate governance, which encompasses the organisational structure and the system of checks and balances of an institution, could also be deterrents to M&As. There are significant differences in the legislative and regulatory frameworks across the countries with regard to functions of the boards of directors (“supervisory”) and senior management. These differences affect the inter-relation of the two decision-making bodies within an institution and relations with the firm’s owners and other stakeholders, including employees, customers, the community, rating agencies and governments. There are also cultural differences and the related information asymmetries. These differences act as strong impediments to cross-border and cross-product levels of consolidation and in the hostile takeovers of financial institutions.

8.17 Information asymmetry faced by stakeholders may hinder M&As as the inadequate information flows increase the uncertainty about the outcome of a merger. Such information asymmetry would arise due to incomplete disclosure or large differences in accounting standards across countries and sectors, lack of comparability of accounting report, difficulties in asset appraisal and lack of transparency.

8.18 Consolidation, among others, has implications for financial stability and monetary policy. With the increase in the size of banks and concentration of banking activities in a few megabanks, various types of risks such as operational risk, contagion risk and systemic risk could increase. Consolidation impacts market power which can have adverse effects on the yield curve by impeding interest rate arbitrage, lending to borrowers and the value of collateral, in turn, affecting the channels of monetary policy transmission (Box VIII.1).

Box VIII.1

Consolidation and Its implications for Financial Stability and Monetary Policy

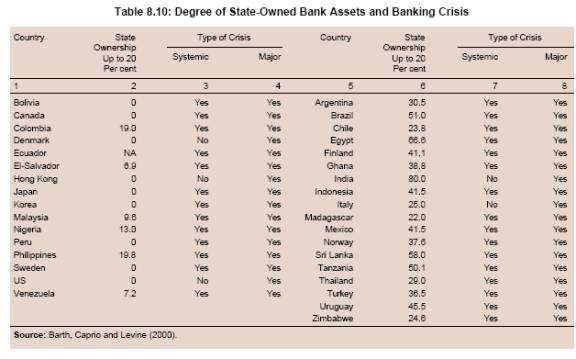

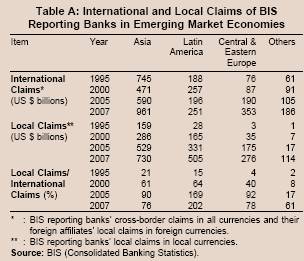

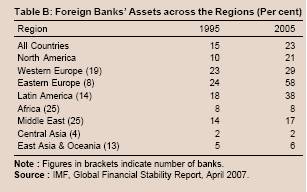

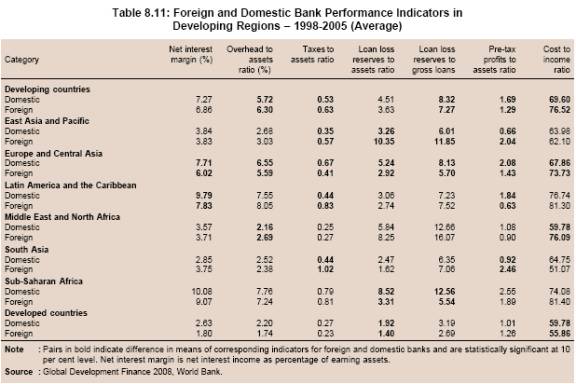

Banking consolidation, irrespective of the motives and types, gives rise to several challenges, of which the implications on financial stability and monetary policy are important ones. It is emphasised that even though there are several potentials for reducing the financial risk through geographical and product diversification at the individual firm level, consolidation leading to creation of megabanks could heighten various types of financial risks at the macroeconomic level. In fact, understanding the financial stability implications of evolving state ownership of banks after consolidation and also increasing presence of foreign banks is a high priority in policy makers’ agenda in various countries. Operational risk could increase with the size of operations, as the distance between management and operational personnel is greater in large companies and the administrative systems are more complex. The transparency of the operations could also deteriorate with increase in size, particularly with regard to cross-border mergers, rendering detection of potential crises in time by the authorities difficult. The contagion risk, i.e., problems arising in an individual bank spreading to others, also increases with size, as banks’ exposures against one another rise along with the size of operations. Evidence suggests that the inter-dependencies, which are positively correlated with consolidation, have increased among large and complex financial institutions. Further, the consolidating institutions are found to shift their portfolios towards higher risk-return investment. Consequently, the concerns about systemic risk are heightened, as concentration of banking activities in few megabanks would mean that given their wholesale activities, any shock could have repercussions to the financial system and the real economy. For a small host nation, cross-border financial integration would mean increase in possibility of even a medium-sized foreign bank becoming a source of instability, and also increased probability of losing domestic ownership of its major banks.

The increased potential for systemic risk further intensifies the concerns for these banks being considered ‘too-big-to-fail’, which gives rise to the problem of moral hazard. Because of the increased potential systemic instability from impairment of such large banks, whatever be the ex ante declaration, the perception of the general public would be that the Government would not allow these banks to fail, and therefore, ex post provide bailout. Because of this perceived implicit or explicit guarantee by the Government, the risk taking behavior of these banks could increase, thereby further enhancing the systemic risk. It is, however, not possible to formulate a specific criteria on when a bank becomes ‘too big to fail’, though it may be concluded that there is a certain critical level with regard to the bank’s importance in the economy and the financial system.

Consolidation leads to greater concentration of payment and settlement flows among few parties within the financial sector. Such concentration implies that if a major payment processor were to fail or were not able to process payment orders, systemic risks could arise. The emergence of multinational institutions and specialised service providers indulging in payment and settlement systems in different countries coupled with increasing inter-dependence of liquidity among them accentuate the potential role of payment and settlement systems in the transmission of contagion effects.

Monetary policy decisions are influenced by the behavior of financial firms and markets. The consolidation process by altering them has also a number of implications in the conduct of monetary policy. Consolidation can reduce competition in the markets, increase the cost of liquidity for some and impede the arbitrage of interest between markets. The performance of the markets could also be affected if the resulting large banks behave differently from their small predecessors. The impeding of arbitrage along the yield curve due to reduced competition would affect the monetary policy channel of transmission effected through interest rates across financial markets. The exercise of market power by the banks resulting from consolidation could also alter the monetary transmission operating through bank lending to borrowers without direct access to financial markets. Consolidation could also affect the way monetary policy affects the value of collateral, and, thus, on the availability of credit to those requiring collateral to obtain funds.

III. RECENT TRENDS IN MERGERS AND

ACQUISITIONS IN THE BANKING INDUSTRY

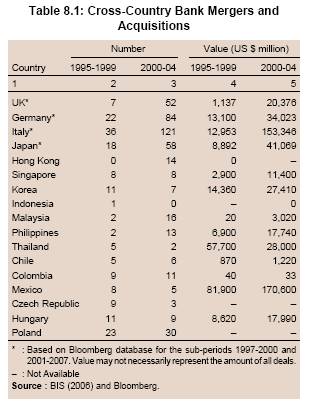

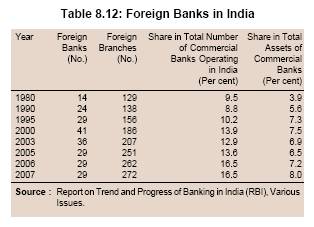

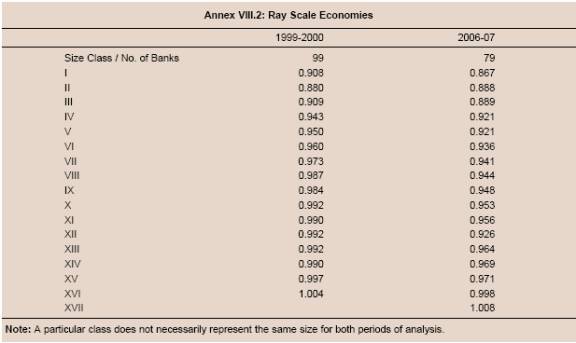

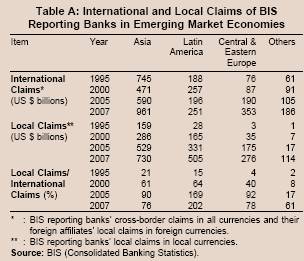

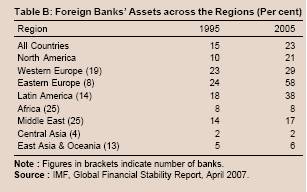

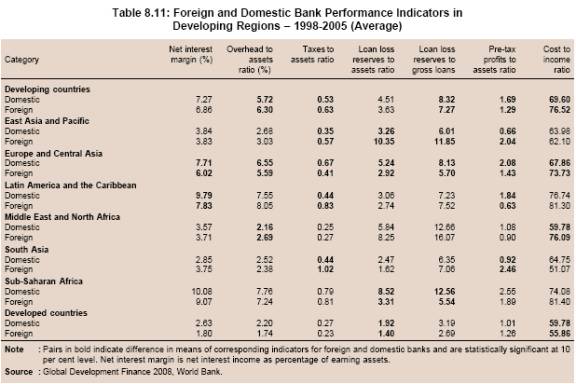

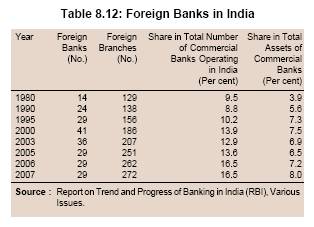

8.19 The number of M&As increased in the advanced countries in recent years. Insofar as EMEs are concerned, while in some countries M&As activity accelerated in recent years, in some other countries, it slowed down. However, the value of M&As increased manifold in several countries, including those where M&As activities slowed down (Table 8.1).

8.20 Much of the consolidation activity in France took place during the 1990s among small banks leading to a large reduction in the total number of banking institutions. Similarly, in Germany consolidation took place among smaller savings and co-operative banks and the number of banks declined by about a third during the 1990s. Following consolidation, the number of banks in Italy also declined by more than a third during the same period. A combination of dismantling of restrictions on interstate and intra-state banking, removal of interest rate ceilings on small time and savings deposits and permission on diversification of activities paved the way for mergers between banks and non-bank financial companies in the US during the 1990s. The consolidation that followed resulted in substantial growth, in both absolute and relative terms, by the largest institutions. In the UK, the regulatory reforms during the 1980s and the 1990s removed restrictions on financial institutions to compete across traditional business lines. This enabled the development of universal banking and led to growth of international banking and conversion of building societies into

banks. Consequently, the number of banks in UK increased substantially before declining by almost 20 per cent following subsequent consolidation.

8.21 In Canada, domestic banks traditionally controlled a large share of the banking sector. Owing to the dominance of the banking industry by a few banks, consolidation is regulated through a guideline established in 2000 to ensure that it does not lead to unacceptable level of concentration and drastic reduction in competition and reduced policy flexibility in addressing future prudential issues. Thus, not much consolidation took place during the 1990s and the number of banks did not decline much from the substantial increase observed during the 1980s due to entry of foreign banks. In Japan also, little consolidation took place during the 1990s and there was only a modest reduction in the number of banks at the end of the 1990s following some bank failures.

8.22 The banking industry in Sweden during the 1990s experienced the merger of co-operative banks into one commercial bank and transformation of the largest savings banks into one banking group. Further, there was consolidation among all the major banking groups. While all the above mergers reduced the number of banks, the total number of banks increased somewhat due to entry of foreign banks and the establishment of several ‘niche banks’ around the same time.

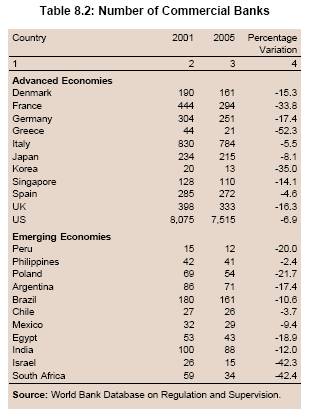

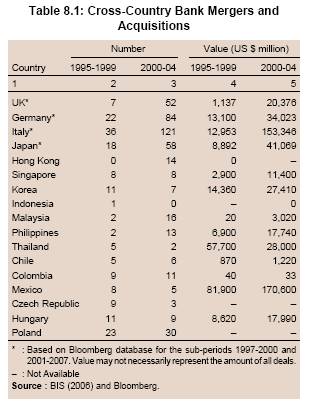

8.23 The banking consolidation since the 1990s resulted in a substantial decline in the number of banks in many emerging market and advanced economies. In US, about 25-30 per cent of banks have closed or merged due to consolidation in last two to three decades (Nitsure, 2008). In fact, the banking systems in EMEs have generally continued to evolve towards more private and foreign-owned structures, with fewer commercial banks and often smaller number of bank branches. In some countries, these trends have been the result of post-crisis weeding-out of weak financial institutions, and mergers encouraged by the authorities (for instance, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand). Elsewhere, these developments have been mostly market-driven (for instance, central Europe and Mexico) (Table 8.2).

IV. CONSOLIDATION AND COMPETITION IN INDIA

8.24 The banking sector reforms undertaken in India from 1992 onwards were aimed at ensuring the safety and soundness of financial institutions and at the same time making them efficient, functionally diverse and competitive. Financial sector reforms

provided banks with operational flexibility and functional autonomy. Reforms also brought about structural changes in the financial sector by recapitalising them, allowing profit making banks to access the capital market and enhancing the competitive element in the market through the entry of new banks. Apart from achieving greater efficiency by introducing competition through the new private sector banks and increased operational autonomy to public sector banks, reforms in the banking system were also aimed at enhancing financial inclusion, funding of economic growth and better customer service to the public.

8.25 The Government and the Reserve Bank provided the enabling environment through an appropriate fiscal, regulatory and supervisory framework for the consolidation of financial institutions and at the same time ensured that a few large institutions did not create an oligopolistic structure in the market (Talwar, 2001). Competitive conditions in the Indian banking sector were strengthened by relaxing entry and exit norms and the increased presence of foreign banks. In February 2005, with a view to further enhancing the efficiency and stability of the banking system, a two-track and gradualist approach was adopted by the Reserve Bank. One track was consolidation of the domestic banking system in both the public and private sectors. The second track was gradual enhancement of the presence of foreign banks in a synchronised manner (Annex VIII.1). The regulatory framework, however, varies for different segments of the banking sector in India.

Mergers and Amalgamations: Regulatory Framework

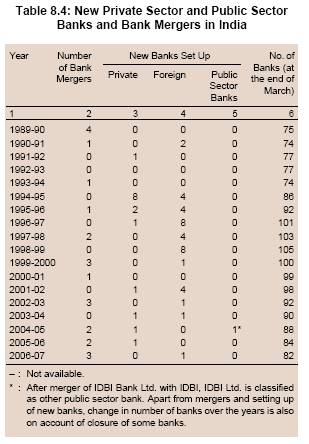

8.26 The regulatory framework for M&As in the banking sector is laid down in the Banking Regulation (BR) Act, 1949. In the post-Independence era, the legal framework for amalgamations of banks in India was provided in the Act. The Act provides for two types of amalgamations, viz., (i) voluntary and (ii) compulsory. For voluntary amalgamation, Section 44A of the BR Act provides that the scheme of amalgamation of a banking company with another banking company is required to be approved individually by the board of directors of both the banking companies and subsequently by the two-thirds shareholders (in value) of both the banking companies. Further, Section 44A of the BR Act requires that after the scheme of amalgamation is approved by the requisite majority in number representing two-third in value of shareholders of each banking company, the case can be submitted to the Reserve Bank for sanction. However, the Reserve Bank has the discretionary powers to approve the voluntary amalgamation of two banking companies under section 44A of the BR Act.

8.27 The experience of the Reserve Bank has been, by and large, satisfactory in approving the schemes of amalgamation of private sector banks in the recent past and there has been no occasion to reject any scheme of amalgamation submitted to it for approval. There have been six voluntary amalgamations between the private sector banks so far, while one amalgamation between two private sector banks (Ganesh Bank of Kurundwad and the Federal Bank) was induced by the Reserve Bank in the interest of the depositors of one of the banks. Most of these voluntary mergers was between healthy banks, somewhat on the lines suggested by the first Narasimham Committee. The Committee was of the view that the move towards the restructured organisation of the banking system should be market-driven and based on profitability considerations and brought about through a process of M&As (Leeladhar, 2008)

8.28 Insofar as compulsory amalgamations are concerned, these are induced or forced by the Reserve Bank under Section 45 of the BR Act, in public interest, or in the interest of the depositors of a distressed bank, or to secure proper management of a banking company, or in the interest of the banking system. In the case of a banking company in financial distress, the Reserve Bank under Section 45(2) of the BR Act may apply to the Central Government for an order of moratorium in respect of a banking company and during the period of such moratorium, may prepare a scheme of amalgamation of the banking company with any other banking institution (banking company, nationalised bank, SBI or its subsidiary). Such a scheme framed by the Reserve Bank is required to be sent to the banking companies concerned for their suggestions or objections, including those from the depositors, shareholders and others. After considering the same, the Reserve Bank sends the final scheme of amalgamation to the Central Government for sanction and notification in the official gazette. The notification issued for compulsory amalgamation under Section 45 of the BR Act is also required to be placed before the two Houses of Parliament. The amalgamation becomes effective on the date indicated in the notification issued by the Government in this regard.

8.29 In the case of voluntary merger or acquisition of any financial business by any banking institution, there was no provision under the BR Act for obtaining approval of the Reserve Bank. In order to revisit the regulatory, legal, accounting and human relations related issues, which may arise in the process of consolidation in Indian banking system, the Working Group (Chairman: Shri V. Leeladhar) was constituted by the Indian Banks’ Association. The Group in its Report titled “Consolidation in Indian Banking System” submitted in 2004 highlighted the need for making an omnibus provision in the BR Act requiring any banking institution to obtain prior approval of the Reserve Bank before acquiring any other business or any merger or amalgamation of any other business of banking institution or non-banking financial institution, with absolute right to the Reserve Bank to finalise the swap ratio which should be made binding on all concerned.

8.30 The Reserve Bank, on the recommendations of the Joint Parliamentary Committee (2002), had constituted a Working Group to evolve guidelines for voluntary mergers involving banking companies. Based on the recommendations of the Group, the Reserve Bank announced guidelines in May 2005 laying down the process of merger proposal, determination of swap ratios, disclosures, the stages at which boards will get involved in the merger process and norms of buying/selling of shares by the promoters before and during the process of merger. Voluntary amalgamation of a non-banking company with a banking company is governed by sections 391 to 394 of the Companies Act, 1956 and the scheme of amalgamation has to be approved by the High Court. However, to ensure the continued strenght of merged entity, it has been provided in the guidelines that in such cases, the banking company should obtain the approval of the Reserve Bank of India after the scheme of amalgamation approved by its Board but before it is submitted to the High Court for approval.

8.31 In both situations, whether a non-banking company amalgamates with a banking company or amalgamation is among banking companies, the Reserve Bank ensures that amalgamations are normally decided on business considerations. For this, the Reserve Bank also laid down guidelines, to which boards of directors should give consideration during the merger process. These guidelines mainly relate to (i) values of assets and liabilities and the reserves of amalgamated entity proposed to be incorporated into the book of amalgamating banking company; (ii) swap ratio to be determined by competent independent valuers; (iii) shareholding pattern; (iv) impact on profitability and, capital adequacy of the amalgamating company; and (v) conformity of the proposed changes in the composition of board of directors with the Reserve Bank guidelines in that context (Box VIII. 2).

8.32 The statutory framework for the amalgamation of public sector banks, viz., nationalised banks, State Bank of India and its subsidiary banks, is, however, quite different since the foregoing provisions of the BR Act do not apply to them. As regards the nationalised banks, the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act, 1970 and 1980, or the Bank Nationalisation Acts authorise the Central Government under Section 9(1)(c) to prepare or make, after consultation with the Reserve Bank, a scheme, inter alia, for the transfer of undertaking of a ‘corresponding new bank’ (i.e., a nationalised bank) to another ‘corresponding new bank’ or for the transfer of whole or part of any banking institution to a corresponding new bank. Unlike the sanction of the schemes by the Reserve Bank under Section 44A of the BR Act, the scheme framed by the Central Government is required, under Section 9(6) of the Bank Nationalisation Acts, to be placed before the both Houses of Parliament. Under this procedure, the only merger that has taken place so far relates to the amalgamation of the erstwhile New Bank of India with Punjab National Bank, on account of the weak financials of the former. As regards the State Bank of India (SBI), the SBI Act, 1955, empowers the State Bank to acquire, with the consent of the management of any banking institution (which would also include a banking company), the business, including the assets and liabilities of any bank. Under this provision,the consent of the bank sought to be acquired, the approval of the Reserve Bank, and the sanction of such acquisition by the Central Government are required. Several private sector banks were acquired by State Bank of India following this route. However, so far, no acquisition of a public sector bank has taken place under this procedure. Similar provisions also exist in respect of the subsidiary banks of the SBI. Thus, there are sufficient enabling statutory provisions in the extant statutes governing the public sector banks to encourage and promote consolidation even among public sector banks through the merger and amalgamation route, and the procedure to be followed for the purpose has also been statutorily prescribed.

Box VIII.2

Guidelines on Mergers and Amalgamations of Banks

The guidelines on merger and amalgamation announced by the Reserve Bank in May 2005, inter alia, stipulated the following:

• The draft scheme of amalgamation be approved individually by two-thirds of the total strength of the total members of board of directors of each of the two banking companies.

• The members of the boards of directors who approve the draft scheme of amalgamation are required to be signatories of the Deed of Covenants as recommended by the Ganguly Working Group on Corporate Governance.

• The draft scheme of amalgamation be approved by shareholders of each banking company by a resolution passed by a majority in number representing two-thirds in value of shareholders, present in person or by proxy at a meeting called for the purpose.

• The swap ratio be determined by independent valuers having required competence and experience; the board should indicate whether such swap ratio is fair and proper.

• The value to be paid by the respective banking company to the dissenting shareholders in respect of the shares held by them is to be determined by the Reserve Bank.

• The shareholding pattern and composition of the board of the amalgamating banking company after the amalgamation are to be in conformity with the Reserve Bank’s guidelines.

• Where an NBFC is proposed to be amalgamated into a banking company in terms of Sections 391 to 394 of the Companies Act, 1956, the banking company is required to obtain the approval of the Reserve Bank before the scheme of amalgamation is submitted to the High Court for approval.

8.33 In short, the primary objective of the Reserve Bank/Government in the process of consolidation is to ensure that mergers are not detrimental to the public interest, bank concerned, their depositors and shareholders, and also that they do not impinge on financial stability. Thus, the Reserve Bank ensures that after a merger, acquisition, reconstruction or takeover, the bank or banking group has adequate financial strength and the management has sufficient expertise and integrity.

Trends in Mergers and Amalgamations

8.34 Consolidation of banks through M&As is not a new phenomenon for the Indian banking system, which has been going on for several years. Since the beginning of modern banking in India through the setting up of English Agency House in the 18th century, the most significant merger in the pre-Independence era was that of the three Presidency banks founded in the 19th century in 1935 to form the Imperial Bank of India (renamed as State Bank of India in 1955).

8.35 In 1959, State Bank of India acquired the state-owned banks of eight former princely States. In order to strengthen the banking system, Travancore Cochin Banking Enquiry Commission (1956) recommended for closure/amalgamation of weak banks. Consequently, through closure/ amalgamations that followed, the number of reporting commercial banks declined from 561 in 1951 to 89 in June 1969. Merger of banks took place under the direction of the Reserve Bank during the 1960s. During 1961 to 1969, 36 weak banks, both in the public and private sectors, were merged with other stronger banks.

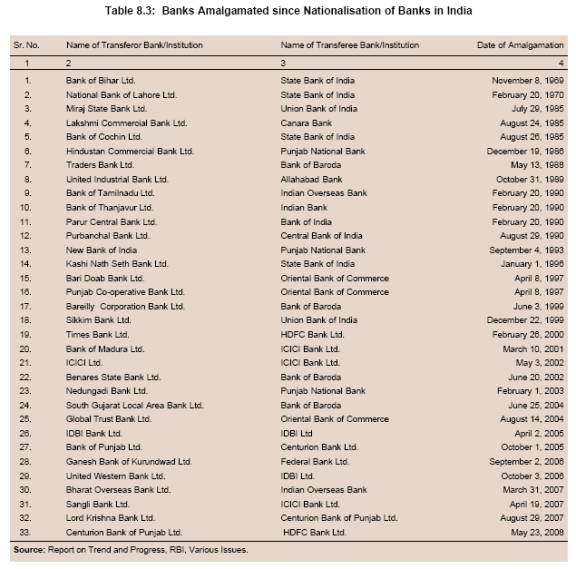

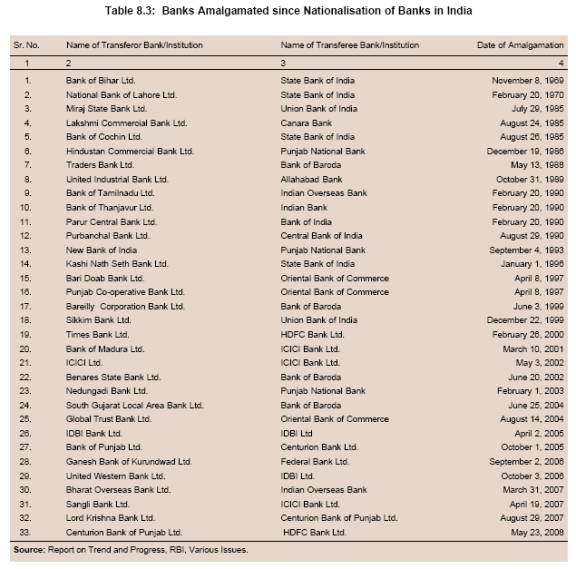

8.36 There have been several bank amalgamations in India in the post-reform period. In all, there have been 33 M&As since the nationalisation of 14 major banks in 1969. Of these mergers, 25 involved mergers of private sector banks with public sector banks, while in the remaining eight cases, mergers involved private sector banks. Out of 33, 21 M&As took place during the post-reform period with as many as 17 mergers/ amalgamations taking place during 1999 and after (Table 8.3)1 . Prior to 1999, the amalgamations of banks were primarily triggered by the weak financials of the bank being merged, whereas in the post-1999 period, there have also been mergers between healthy banks, driven by the business and commercial considerations (Leeladhar, 2008).

8.37 More recently the process of M&As in the Indian banking sector has been generally market driven. Given the policy objective of mergers, most of the mergers between banks in India have taken place voluntarily for strategic purposes. Given the difficulty of small banks to compete with large banks, which enjoy enormous economies of scale and scope, the Reserve Bank has been encouraging the consolidation process, wherever possible. Most of the amalgamations of private sector banks in the post-nationalisation period were induced by the Reserve Bank in the larger public interest, under Section 45 of the Act. In all these cases, the weak or financially distressed banks were amalgamated with the healthy banks. The over-riding principles governing the consideration of the amalgamation proposals were: (a) protection of the depositors’ interest; (b) expeditious resolution; and (c) avoidance of regulatory forbearance. The amalgamations of the erstwhile Global Trust Bank and United Western Bank with public sector banks are recent examples of such mergers. Even in such cases, commercial interests of the transferee bank and the impact of the amalgamation on its profitability were duly considered. The mergers of many weak private sector banks with the healthy ones have brought the Indian banking sector to a credible position, as the CRAR of all private sector banks in the country was more than the minimum regulatory requirement of nine per cent as at end-March 2007.

8.38 M&As in India have also been used as a tool for strengthening the financial system. Through a conscious approach, the weak and small banks have been allowed to merge with stronger banks to protect the interests of depositors, avoid possible financial contagion that could result from individual bank failures and also to reap the benefits of synergy. Thus, the Indian approach has been different from that of many other EMEs, wherein the Governments were actively involved in the consolidation process. For instance, in East-Asia, after the banking crisis in 1997, the Government led the process of bank mergers in order to strengthen capital adequacy and the financial viability of many smaller and often family-owned banks. In these crisis ridden countries, the involvement of the Government was inevitable, as viable but distressed institutions were hardly in a position to attract potential buyers without moving some non-performing loans to an asset management company and/or receiving temporary capital support. Such intervention also proved more cost-effective than taking the bank into public ownership. However, with the intensification in competition through deregulation, privatisation and entry of foreign banks in the emerging markets, consolidation is becoming more market-driven (Box VIII. 3).

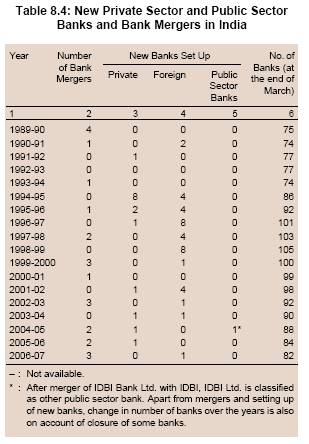

8.39 The consolidation process in the banking sector in India in recent years was confined to mergers in the private sector and some consolidation in the state-owned sector. After nationalisation of banks in 1969, India did not allow entry of private sector banks untill January 1993, when barriers to entry for private sector banks were removed. India also liberalised the entry of foreign banks in the post-reform period. These liberalised measures resulted in entry of many new banks (private and foreign). Accordingly, the number of banks increased during the initial phase of financial sector reforms. However, the pace of consolidation process gathered momentum from 1999-2000, leading to a marked decline in the number of private and foreign banks (Table 8.4). In February 2005, providing a comprehensive framework of policy relating to ownership and governance in private sector banks, the Reserve Bank prescribed that the capital requirement of existing private sector banks should be on par with the entry capital requirement for new private sector banks prescribed on January 3, 2001, according to which, banks are required to have capital initially of Rs. 200 crore, with a commitment to increase to Rs.300 crore within three years from commencement of business. In order to meet this requirement, all banks in the private sector should have a net worth of Rs. 300 crore at all times. Thus, post-2005 period, amalgamations/mergers have resulted partly from these guidelines. The number of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) declined to 82 at end-March 2007 from 100 at end-March 2000 due to merger of some old private sector banks. In recent years, in the case of some troubled banks, the only option available with the Reserve Bank was to compulsorily merge them with stronger banks under section 45 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. These included amalgamation of Global Trust Bank with Oriental Bank of Commerce in August 2004, Ganesh Bank of Kurundwad Ltd. with Federal Bank Ltd. in September 2006 and the United Western Bank with IDBI Ltd. in October 2006.

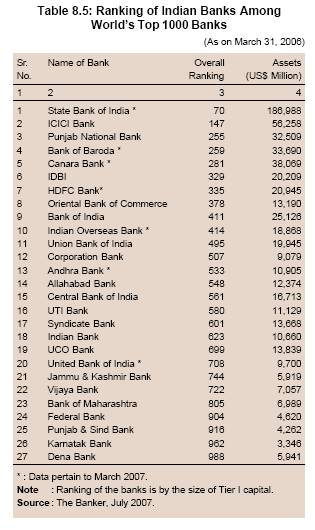

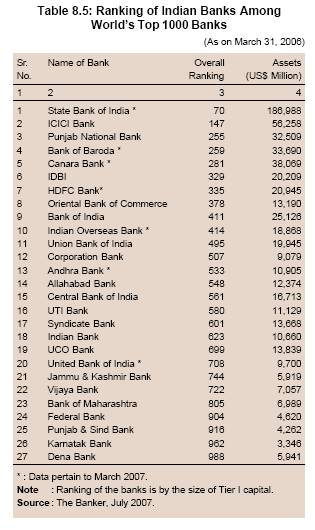

8.40 Mergers and amalgamations involved relatively smaller banks. The largest number of mergers took place with ICICI Bank, Bank of Baroda and Oriental Bank of Commerce (each one of them was involved in three mergers). ICICI Bank replaced many entities to occupy the second position in the Indian banking sector after State Bank of India. In the Banker’s list of the top 1000 banks of the world (July 2007), there were 27 Indian banks (as compared with 20 in July 2004). Of these, 11 banks were in the top 500 banks (as compared with 6 in July 2004) (Table 8.5). Even within Asia, India’s largest banks, viz., SBI and ICICI Bank held 11th and 25th place, respectively.

Box VIII.3

Market driven versus Government-led Bank Consolidation: Cross-Country Experience

While the rationale and the driving factors behind the consolidation process might have undergone change inter-temporally and varied across countries, two distinct dimensions broadly emerge from the history of bank consolidations, viz., market driven vis-à-vis government led consolidation.

A large number of banking consolidations since the early twentieth century followed from the Government policy to consolidate either on account of efforts to restructure inefficient banking systems or from intervention following the crisis. In Japan, the Bank Law of 1927 set the minimum capital criterion for banks, which came as a powerful measure for the Government to promote bank consolidation. Likewise, during the 1920s in the US, agriculture distress produced a wave of small bank failures, necessitating the repeal of many State laws prohibiting branch banking. In the emerging markets of South-East Asia and Latin America, much of the banking consolidation since the 1990s has been government-driven following the need to redress the distress within the financial system. During the financial crisis in 1997, the Korean Government accorded the top priority to financial sector restructuring through the earliest possible resolution of unsound financial institutions. The Government acted swiftly and decisively to close down financial institutions deemed non-viable after an exhaustive review of their financial situations. Somewhat similar phenomenon was observed in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. The Taiwanese Government also promoted consolidation in the financial sector in recent years. Similarly in Latin America, following numerous episodes of financial sector crises, the number of banks in the region declined significantly mainly through government efforts to restructure and consolidate the banking system. In Japan, realising the emergence of NPLs and lack of prudent risk management, Government steered some of the mergers in the overcrowded Japanese banking system during the 1990s.

On the other hand, the bank consolidation process since 1984 in the US, though facilitated by some legislative changes, was also an outcome of market-led forces. During the 1980s, many banks in the US experienced large loan losses and profits associated with depressed economy and excessive risk taking (Shull and Hanweck, 2001). Bank failures rose to high levels resulting in substantial number of mergers and acquisitions by better capitalized and profitable banks. These developments led to substantial improvements in profitability and capitalisation of banks in 1990s. With the onset of improved performance of banks, the number of mergers attributable to bank failures decreased but the number of mergers continued to increase on account of policy permissiveness in the US. The strict regulatory environment that existed before the 1980s largely precluded any dramatic consolidation within the US banking industry. Consolidation of the banking industry began in the earnest only after the regulatory constraints were relaxed in the early 1980s through a decade-long process of deregulating the banking and thrift industries so that they could be more responsive to marketplace realities (Jones and Critchfield, 2005). The removal of geographical restrictions on bank branching and holding company acquisitions by the individual states by the Reagle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branch Efficiency Act of 1994 greatly facilitated bank consolidation. Most of the bank acquisitions were carried out with the aim of securing consistent earnings growth in the future. The saturated markets offered limited organic growth potential, while the banks’ balance sheets were strong. Thus, there was the need to grow via mergers and acquisitions for ensuring long-term earnings. This trend sometimes also led to increased market pressure for banks and financial institutions in other mature economies to keep pace and consolidate in their home markets. In the case of EU commercial banks, the banks responded to the new operating environment by adapting their strategies, seeking new distribution channels and changing their organisational structures. Thus, increased competition has been considered the main driving force behind the acceleration in the consolidation process in the EU economies (Casu and Girardone, 2007).

In Central and Eastern Europe and Mexico, the bank consolidation process that started in the late 1990s, has also been more market-driven with the foreign banks playing an important role. Political action, however, has influenced the process of consolidation in some but not all European markets. For instance, the very good performance of big Italian banks was enabled by the privatisation of the savings banks. Similarly, domestic consolidation in France was encouraged through the formation of “national champions”. It is being observed that multiple forces have been at play to motivate consolidation deals, both within European countries and cross-border. These forces resulting in market driven consolidation process included the fragmented market, foreign competition, deregulation, technological innovation and the introduction of a single currency. For instance, ‘Bank Consolidation Program’ in Poland involved pooling of state-owned banks in order to increase their market share and efficiency.

References:

Casu, Barbara and Claudia Girardone (2007). “Does Competition Lead to Efficiency? The Case of EU Commercial Banks.” University of Essex Discussion Paper No. 07-0, University of Essex.

Jones, Kenneth D. and Tim Critchfield (2005). “Consolidation in the U.S. Banking Industry: Is the ‘Long, Strange Trip’ About to End?” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Banking Review, Vol.17, No. 4.

Shull, Bernard and Hanweck, Gerald A. 2001. “Bank Mergers in a Deregulated Environment: Promise and Peril”. Quorum Books. USA.

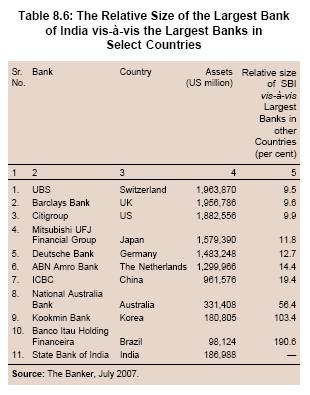

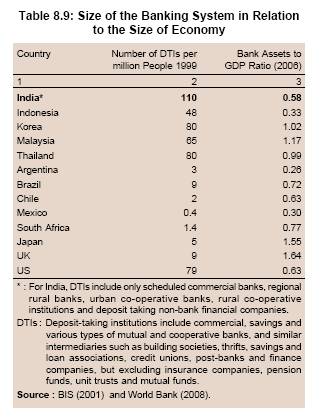

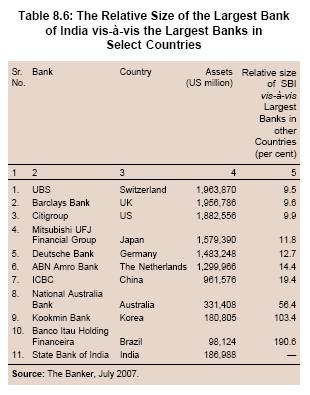

8.41 The combined assets of the five largest Indian banks, viz., State Bank of India, ICICI Bank, Punjab National Bank, Canara Bank and Bank of Baroda, on March 31, 2006 were about 51.0 per cent of the assets of the largest Chinese bank, Bank of China, which was roughly 3.6 times larger than State Bank of India. Even in the Asian context, only one Indian bank –State Bank of India – figures in the top 25 banks based on Tier I capital, even though Indian banks offer the highest average return on capital among Asian peers. The total assets of State Bank of India were less than 10.0 per cent of the top three banks in the world. However, the size of State Bank of India was larger than the largest bank operating in some emerging markets such as Korea and Brazil. In a way, this suggests that the size of bank and the banking sector depends on the size of the economy (Table 8.6).

8.42 The mergers of regional rural banks (RRBs) have taken place on a large scale in India since September 2005. Mergers of RRBs were largely policy driven in pursuance of the recommendations of the Committee on the “Flow of Credit to Agriculture and Related Activities” (Chairman: Prof. V.S. Vyas). The Committee in its Report submitted in June 2004 had recommended restructuring of RRBs in order to improve the operational viability of RRBs and take advantage of the economies of scale. In order to reposition RRBs as an effective instrument of credit delivery in the Indian financial system, the Government of India, after consultation with NABARD, the concerned State Governments and the sponsor banks, initiated State-level sponsor bank-wise amalgamation of RRBs to overcome the deficiencies prevailing in RRBs and making them viable and

profitable units. Consequent upon the amalgamation of 154 RRBs into 45 new RRBs, sponsored by 20 banks in 17 States, effected by the Government of India, the total number of RRBs declined from 196 to 88 as on May 1, 2008 (which includes a new RRB set up in the Union Territory of Puducherry). The structural consolidation of RRBs has resulted in the formation of new RRBs, which are financially stronger and bigger in size in terms of business volume and outreach and would enable them to take advantage of the economies of scale and reduce their operational costs.

8.43 Consolidation has also been seen as one of the exit routes for non-viable urban co-operative banks in India. The process of merger of weak entities with stronger ones was set in motion by providing transparent and objective guidelines for granting no-objection to merger proposals. The Reserve Bank, while considering proposals for merger/ amalgamation, confines its approval to the financial aspects of the merger taking into consideration the interests of depositors and financial stability. Almost invariably it is a voluntary decision of the banks that approach the Reserve Bank for obtaining no objection for their merger proposal. The guidelines on mergers are intended to facilitate the process by delineating the pre-requisites and steps to be taken for merger between banks. As on October 30, 2007, a total of 33 mergers had been effected upon the issue of statutory orders by the Central Registrar of Co-operative Societies/Registrar of Co-operative Societies (CRCS/ RCS) concerned (RBI, 2007).

V. MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS: IMPACT ON

COMPETITION AND EFFICIENCY IN INDIA

8.44 A good deal of debate on competition effects of bank consolidation has been phrased in terms of two competing hypotheses. The structure-conduct-performance paradigm argues that concentration will intensify market power and thereby stymie competition and efficiency. In contrast, the efficiency paradigm argues that economies of scale drive bank mergers and acquisitions, so that increased concentration goes hand-in-hand with efficiency improvements.

8.45 The impact of consolidation through M&As on competition operates through a number of channels, and among others, depends on the market structure, the nature of competition and the regulatory and supervisory framework. The competition effect would depend on the degree of concentration, the degree of entry barriers, the heterogeneity of products and price differentiation allowed. Depending on the level of competition of the banking industry, consolidation influences the provision of credit to different customer groups. Cross-country analysis does not provide support for the view that bank concentration is closely associated with banking sector efficiency, financial development, industrial competition, general institutional development, or the stability of the banking system. In fact, the impact of M&As on competition in the banking sector has not been uniform (Box VIII. 4).

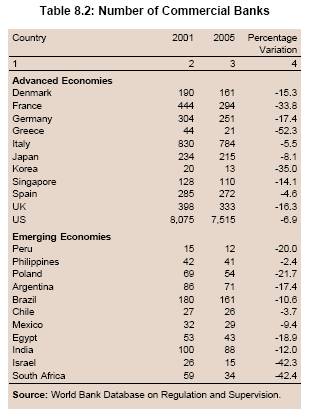

8.46 M&As, especially market driven, are aimed at stepping up size (market powers) and maximising value (revenue) by exploiting economies of scale and scope, risk diversification and strengthening capital. Most recent studies have found unexploited scale economies even for larger banks in the US (Berger and Mester, 1997; Berger and Humphrey, 1997) and in Europe (Allen and Rai, 1996 and Vander Vennet, 2001). In the presence of excess capacity, some banks are bound to operate below efficient scale and may also have an inefficient product mix and, therefore, may be inside the efficiency frontier. In such a situation, M&As may help solve these problems more efficiently rather than outright bankruptcies because they preserve the franchise values of the merging banks (Huizinga et al, 2001).

Box VIII.4

Impact of Consolidation on Competition: Cross-country Evidence

Consolidation process may be a response to tackle the increased competition but it also affects potential competition. The primary factor that affects potential competition is the relative position of both merging entities in the banking system. For instance, merger of banks operating at the lower end of the banking system may have little implications for potential competition. Consolidation may affect competition through increase in the market concentration. Generally, in the case of financial industry, full contestability does not hold due to entry barriers directly imposed by regulatory authorities, inherent features in firms’ cost structures and relatively inelastic customer demand.

The effect of concentration on competition also depends on whether firms compete on quantities or prices. In the first case, it is straightforward to show that the smaller the number of firms, the closer is the market outcome to monopoly. In the second case, the effect depends on the heterogeneity of products; the more heterogeneous the products are, the greater is the market power of firms. Firms tend to adopt niche strategies in order to differentiate products beyond their essential characteristics.

The effects of consolidation on competition is evaluated either directly by studying markets that have experienced consolidation or indirectly in cross-sectional studies comparing markets with different degrees of concentration at a point of time. Most of these studies find that M&As may have influenced market prices. In the US, a reduction in the interest rate on deposits is detected in markets that have been affected by consolidation (Prager and Hannan, 1998). Estimates of the impact of mergers on prices for the Swiss retail banking market indicate that concentration may have a negative effect on prices (Egli and Rime, 2000). In the M&As in Italy, loan rates increase when the market share of the acquired bank is large (Sapienza, 1998). The indirect approach using European data generally finds that higher concentration leads to less favourable conditions for bank customers (De Bonis and Ferrando, 1997). Market power in connection with prices for small business loans and retail deposits is found to exist in both US and Europe (Berger and Hannan, 1989 and Hannan 1991). However, it was indicated that the connection between concentration and retail deposit rates has dissipated somewhat in the 1990s relative to the previous decade (Hannan, 1997). Though the US banking industry has become stronger through the geographic diversification of risks, most researchers, especially those focusing on the 1980s and the early 1990s, did not find any broad-based improvements in cost efficiency emanating from economies of scale or scope. For the Latin American banking system, it was found that (i) concentration in banking markets did not necessarily lead to a lower level of competition and higher bank performance; and (ii) bank returns were negatively linked to the degree of competition and, to a lower extent, to foreign bank participation (Yildirim and Philippatos, 2007). Furthermore, in the context of the Latin American banking system, Yeyati and Micco (2007) suggested that it was not at all clear whether competition and concentration should go in opposite directions. In a cross-country study using structural model covering 50 major advanced and emerging market economies, Claessens and Laeven (2003) found that lower activity restrictions in the banking sector and greater foreign bank presence make banking systems more competitive. Emerging economies in the study included Argentina, Brazil, Chile, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Russian Federation and Turkey, among others. However, they found no evidence that banking system concentration was negatively associated with competition.

In the emerging market banking systems, consolidation, to a large extent, has not yet translated into decline in competitive pressures. To some degree, this has been attributed to the process still being in its infancy, particularly in Central Europe and Turkey. Taking into account the internationalisation of banking sector in Turkey, Abbasoglu, Aysan and Gunes (2007) found no evidence of the existence of relationship between consolidation and competition. However, even for countries where the consolidation process is more advanced, namely Argentina and Mexico, no obvious impact of consolidations on competition intensity has been found (Gelos and Roldos, 2002). Bank consolidation in most emerging economies has not yet been associated with any marked rise in concentration, as most mergers appeared to have involved smaller banks. One reason for this pattern could have been reluctance on the part of the authorities to sanction mergers between the largest banks, which could raise both competition and moral hazard concerns. An important point that the recent literature on concentration-competition suggests is that the number of banks and the degree of concentration are not, in themselves, sufficient indicators of contestability. Other factors play a strong role, including regulatory policies that promote competition, a well-developed financial system, the effects of branch networks, and the effect and uptake of technological advancements (Northcott, 2004).

References :

Prager, and Hannan. 1998. “The Relaxation of Entry Barriers in the Banking Industry: An Empirical Investigation.”

Journal of Financial Services Research, 14(3). Berger, Allen N. and Timothy H. Hannan. 1989. “The Price-Concentration Relationship in Banking’.” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 71.

Claessens, Stijn and Laeven, Luc, 2003. “What drives bank competition? some international evidence.” Policy Research Working Paper Series 3113, The World Bank.

8.47 The Indian banking system has witnessed certain visible structural changes in the post-reform period. Apart from mergers/amalgamations and entry of new private and foreign banks, the Government equity has also been diluted in public sector banks. Of the 28 public sector banks, 22 banks have raised capital from the market. In three banks, the Government equity holding has come down close to 51 per cent. The changes in the ownership structure along with consolidation and entry of private and foreign banks are expected to have an impact on the overall competition in the banking sector.

8.48 To evaluate the impact of various changes specifically on competition in the banking system, a number of concentration indicators have been analysed. The process of consolidation may affect competition by enhancing concentration. To assess the implications, it is important to measure concentration, which could reflect the size distribution of banks. These include K-concentration ratio, Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and Theil’s Entropy measure of major banking sector variables such as assets and deposits (Box VIII. 5).

8.49 A number of widely used indicators suggest that despite a number of bank mergers and acquisitions, the Indian banking system has become less concentrated during the post-reform period. On the basis of asset size, there was little change in the

Box VIII.5

Measures of Concentration Indices

Various methods have been devised to measure degree of concentration based on various theoretical foundations (Bikker, 2004). Concentration measures can be classified according to their weighting schemes and structures. The weighting scheme of an index determines its sensitivity towards changes in the tail end of the bank size distribution. The structure of concentration index can be discrete or cumulative. Discrete measures of concentration correspond to the height of concentration curve at an arbitrary point. The K-bank concentration ratio, for instance, is discrete measure which is simple and can be calculated even when the entire data set is not available. However, this measure ignores the structural changes taking place in those parts of banking sector which are not covered in the concentration ratio. Cumulative measure of concentration, on the other hand, explains the entire size distribution of banking sector and covering the structural changes in all parts of the distribution. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and Theil’s entropy index display such features.

Simplicity and limited data requirements make K-bank concentration ratio as the most commonly used measure of concentration which sums up the market shares of K largest banks. It gives equal weight to K leading banks, but neglects smaller banks. It varies between 0 and one (if market shares are measured in fractional form instead of percentage form).

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is second most popular summary measure of market concentration. It is defined as the sum of the squares of the market shares of each bank in the market. This is also often called full information index as it captures features of the entire distribution of bank sizes. It takes the form:

The index ranges from 10,000 in the case of monopoly (or 1.0 when market share is in fractional form) to close to zero when there are large numbers of firms with no one firm having substantial market share. It will vary not only with the proportion of deposits/assets held by an arbitrary number of large K banks in the market, but also with the relative distribution of deposits among all banks in the market. In the US, the HHI plays a significant role in the enforcement process of anti-trust laws in banking. HHI is used for scrutinising proposed merger of banks (Shull and Hanweck, 2001). Since 1982, the US Department of Justice has based its merger guidelines on the HHI.

In contrast to HHI, the entropy index assigns greater weight to smaller banks and vice-versa. Under this method, each market share is weighed by taking log of the inverse of market share of each bank. The major advantage of using the HHI and the entropy measures is that each bank is separately included in order to avoid arbitrary cut-offs and insensitivity to the share distribution.

The entropy index assigns weights to the shares of a bank’s activity by a log term of the inverse of the respective shares. This index gives less weight to larger activities than the HHI. These two measures are inverse of each other. Apart from these, there are several other alternative measures of concentration examining the evenness or unevenness of the size distribution of entities in a particular sector. These include Kwoka index, Horvarth Index and Rosenbluth Index, among others.

References:

Bikker, Jacob A. 2004. “Competition and Efficiency in a Unified European Banking Market.” Edward Elgar Publishing.

Shull, Bernard and Hanweck, Gerald A. 2001. “Bank Mergers in a Deregulated Environment: Promise and Peril.” Quorum Books, USA.

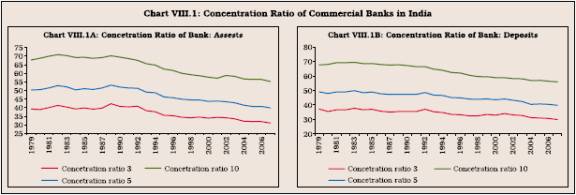

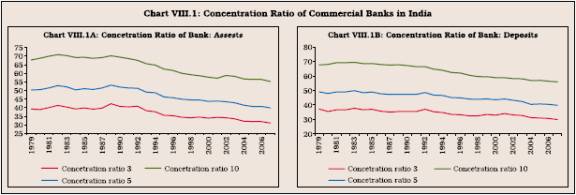

five-bank concentration ratio during 1978-79 and 1990-91, while it declined substantially from 51.4 per cent in 1991-92 to 44.5 per cent in 1998-99 and further to 39.9 per cent in 2006-07. A similar trend was discernible in the concentration of bank deposits (Chart VIII.1).

8.50 This was perhaps for the reason that bank mergers took place mostly among the small banks having little impact on market structure indicators. Besides, several new private and foreign banks were also set up. However, it is significant to note that the concentration declined even after 1999-2000 when the number of operating banks declined.

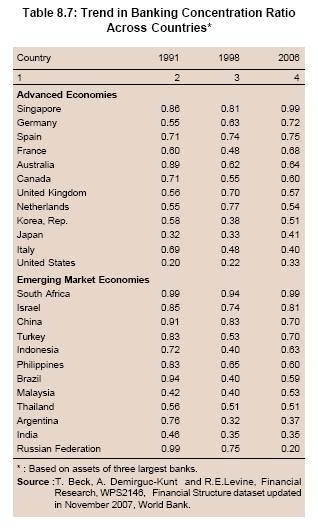

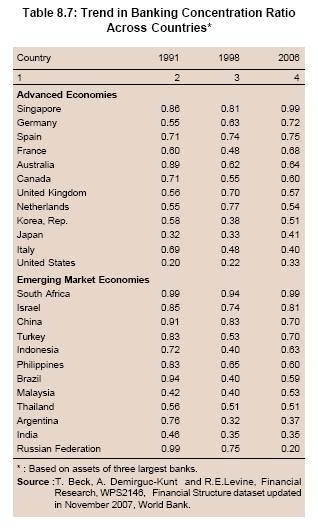

8.51 A cross-country analysis in terms of concentration ratios suggests that in several countries, concentration declined between 1991 and 2006, while in some advanced countries (US, Japan, Germany, Spain and France), it increased somewhat. The market structure of the Indian banking sector is less skewed when compared with most of the advanced and other emerging market economies (Table 8.7). The degree of concentration in the Indian banking sector was far lower than that in China, France, Spain, the UK, Singapore and South Africa. In fact, the degree of concentration in the Indian banking system, based on concentration ratio in 2006, was one among the lowest (after Russian Federation and the US).

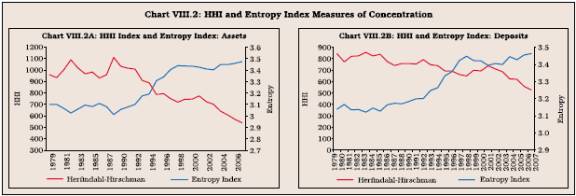

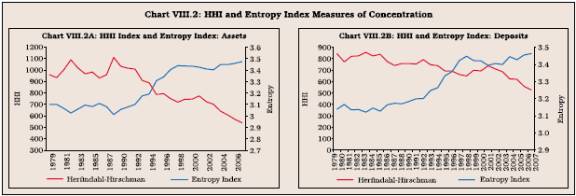

8.52 The evidence of growing competitive pressures was also well supported by the declining trend of HHI. The HHI for total assets declined from 1008.2 per cent in 1991-92 to 540.7 per cent during 2006-07. The entropy index of concentration also corroborated the finding based on HHI (Chart VIII.2). Similar trend was discernable from the market structure indicators based on the size of bank deposits, in which concentration was relatively lower than that of assets.

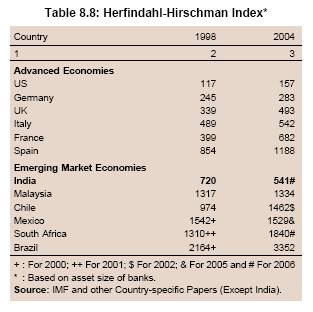

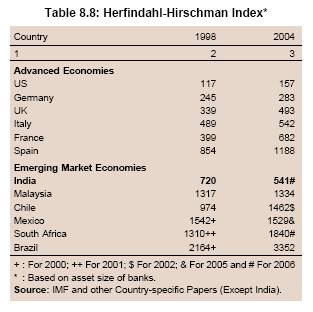

8.53 A comparison with other countries shows that the concentration ratio measured in terms of HHI declined in India between 1998 and 2004, while it increased in all the select advanced and emerging market economies studied. In 2004, concentration was lowest in the US, followed by Germany and the UK. The concentration ratio in India, based on HHI measure was also lower than the select sample of emerging market economies, reflecting a greater degree of banking competition in India. The findings based on HHI are largely consistent with the concentration ratio as set out in Table 8.7 Although the concentration ratio and the HHI are most commonly used measure of concentration, the findings based on them can be somewhat different as concentration merely covers top K number of banks while the HHI, being more informative, covers the whole size distribution of the banking sector. Concentration in the Indian banking sector based on HHI was higher than that in the US, Germany and the UK (the least concentrated countries) perhaps on account of a large number of banking institutions operating in these countries, but HHI was lower than all other countries in the sample (Table 8.8).

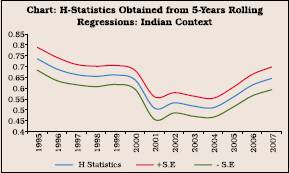

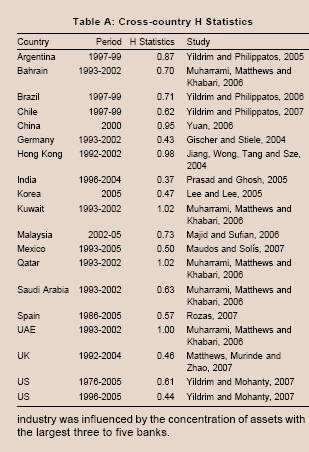

8.54 While the various measures of concentration ratios provide the market structure and influences the way the banks operate, they do not fully indicate the actual conduct, and, therefore, the performance of the market. In other words, a highly concentrated banking sector does not necessarily imply lack of competition though it creates the potential for collusion among large banks. Similarly, a less concentrated market does not necessarily imply a greater degree of competition though its potential for the same is higher. Efficiency is also not necessarily enhanced by competition, as it can so happen that collusive behavior of large banks in a highly concentrated market results in superior market performance (Bikker and Haaf, 2002). In the literature, one common measure for the conduct (competition) of the banking industry is the H-statistic formulated by Panzar and Rosse (1987) to distinguish between oligopolistic, competitive and monopolistic markets. Based on H-Statistic, the Indian banking industry could be characterised as a monopolistically competitive market as is the case with most other advanced and EMEs. The level of competition appeared to have declined somewhat in the initial years of reforms, but improved thereafter. It was also found that the level of competition in the Indian banking industry was influenced by the concentration of assets with the largest three to five banks. In other words, greater is the degree of concentration of banking assets in a few large banks, the lower is the degree of competition (Box VIII. 6).

Box VIII.6

Panzar-Rosse Statistics: The Indian Case

An empirical test was developed by John C. Panzar and James N. Rosse (1987) to discriminate between oligopolistic, monopolistically competitive and perfectly competitive markets. Their procedure, which is based on the comparative static properties of reduced-form revenue equations, accomplishes a concise indicator which is called H-statistic. Under certain restrictive assumptions, it can be interpreted as a continuous and increasing measure of the overall level of competition prevailing in a particular market. The methodology suggested by Panzar and Rosse stems from a general equilibrium market model. It is based on the premise that firms employ different pricing strategies in response to changes in factor input prices depending on the competitive behavior of market participants. In other words, competition is measured by the extent to which changes in input prices are reflected in firms’ equilibrium. The H-statistic provides a single number reflecting the overall level of competition prevailing in the market under consideration. The H-statistic can be used to identify the three major market structures, namely, monopoly/perfect collusion, monopolistic competition and perfect competition/ contestable market. Conclusions about the type of market structure are made based on the size and sign of the H-statistic.

Panzar and Rosse argued that market power can be measured by the extent to which changes in factor prices are reflected in revenues. With perfect competition, an increase in factor prices (say, deposit interest rates) induces no change in output but a proportional change in output prices (i.e., under a perfectly elastic demand assumption). Instead, with monopolistic competition, or with potential entry leading to contestable markets, revenues would increase less than proportionally, as the demand for banking products facing individual banks is less than perfectly elastic. A number of studies in recent years have extended the P-R methodology to banking sector. Based on a reduced-form equation of revenue at the individual bank level, market power is inferred from the H-statistic, which measures the extent to which changes in factor prices are reflected in banks’ revenue. If the market is perfectly competitive, an increase in factor prices would raise revenues equi-proportionally and the H-statistic should assume a value equal to 1. On the other hand, in the “intermediate” case of monopolistic competition, the H-statistic assumes a value between 0 and 1, with an increase in input prices leading to a less than proportional increase in revenues, as the demand for bank products facing individual banks is inelastic. A negative H arises when the market structure is a monopoly or a perfect colluding oligopoly (Rozas, 2007). Contestable markets would also generate an Ira H-statistic equal to unity.

Since P-R is a static approach, a critical feature of the empirical implementation is that the test must be undertaken on observations that are in long-run equilibrium. In previous studies, testing for long-run equilibrium involved the computation of the H-statistic in a reduced-form equation of profitability, using a measure such as return on equity/assets (ROE or ROA) in place of revenues as dependent variable. The resulting H was supposed to be significantly equal to zero in equilibrium, and significantly negative in case of disequilibrium. Overall, the P-R model is regarded as a valuable tool for assessing market conditions.

Most of the previous empirical estimations of P-R model were done for developed countries and recently, several studies employed this methodology to quantitatively assess the degree of competition and market structure of banking industry in developing and transition countries. In general, all of these studies find that banking market is best described as monopolistic competition. Using annual data on scheduled commercial banks for the period 1996-2004, Prasad and Ghosh (2005) found that the Indian banking system operates under competitive conditions and earns revenues as if under monopolistic competition.

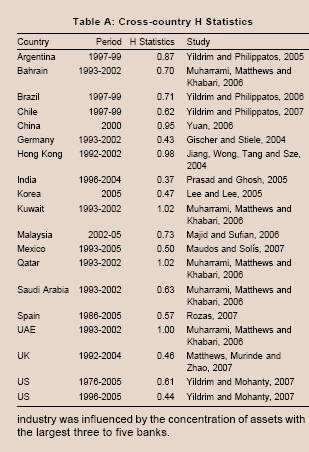

In an attempt to compute H-Statistic in the context of Indian banking system, the following reduced form of equation for bank revenue function was estimated:

Ln(TREV) = a0 + a1 Ln PL + a2 LnPK + a3 Ln PF + a4 Ln EQ + a5 Ln Size + a6 Ln LO

Where:

TREV is the ratio of total revenue to total assets, PL is ratio of personnel expenses to employees as percentage of total assets, PKs ratio of other expenses to total assets used as proxy for unit price of capital, PFs ratio of annual interest expenses to total assets. A number of bank-specific factors were also included as control variables to account for size, risk, and capacity differences. These were size measured in terms of total assets, capital to assets ratio (EQ) to control for difference in capital structure, and loan to total assets ratio (LO) as a proxy for degree of intermediation. Under the P-R framework, the H-statistic is equal to the sum of the elasticities of the revenue with respect to the three input prices, i.e., H = a1 + a2 + a3. The testable hypothesis for monopolistic competition is 0 < H < 1, while H £ 0 is monopoly. In a symmetric monopolistic competitive market, 0<1. It is worth emphasizing that not only is the sign of H important, but its magnitude is equally important (Panzar and Rosse, 1987).

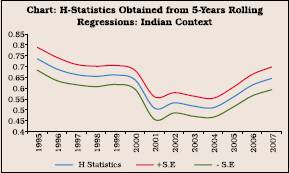

The H-statistics was estimated for the period 1990 to 2007 using 5-years rolling regressions. The unit cost of funds (PF) had a positive sign and was statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. Also, PL turned out to be significant at the conventional levels of significance. Confirming the findings of Prasad and Ghosh (2005), the results indicated that the price of funds provided the highest contribution to the explanation of interest revenues (and therefore to the H statistic), followed by the price of labor. The H-statistic ranged between 0.8 to 0.45 with the value showing an initial decline and a rise thereafter (Chart). Bank competition seems to have strengthened particularly during post-2000 period. Since H statistics are found to be significantly different from both 0 and 1, the monopoly and perfect competition hypotheses are rejected and thus support the view that Indian banks earn their revenues under monopolistic competition which is also the case in most of the developed countries and other emerging market economies. A survey of literature, however, shows that banking sectors in China, Hong Kong, Kuwait, UAE and Saudi Arabia operate under near perfect competition conditions (Table A). In the case of China, Yuan (2006) argues that the small banks in China are newer, and are in the stage of studying the managerial experience of international banks, and in addition they are not protected by the State. As a result, the competition among small banks is so high that it is near perfect competition. Similarly, the large Chinese banks operate businesses on an international scale and compete with others in the international market and also operate under much more competitive conditions.

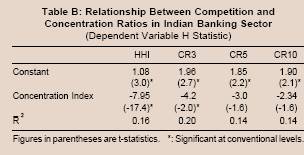

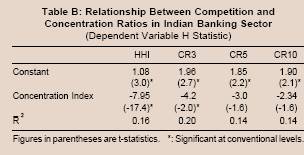

Further, as the conduct of the market is expected to be influenced by the market structure, the relationship between H-statistics and various measures of concentration was estimated for India. As expected from a priori theoretical arguments, it was found that all the measures of concentration ratios and index had a negative relationship with H-statistics, indicating that the greater the degree of concentration of banking assets, the lesser is the degree of competition. However, the relationship was statistically significant at the conventional level only with the concentration ratio of the three largest banks. On augmenting the relationships with the share of private sector in total assets, it was found that the negative relationships were statistically significant for all the measures of concentration ratios, except ‘CR10’ (Table B). In sum, the level of competition in the Indian banking

References:

Gutiérrez de Rozas, Luis. 2007. “Testing for Competition in the Spanish Banking Industry: The Panzar-Rosse Approach Revisited.” Banco de España Research Paper No. WP-0726, August.

Panzar, J. and Rosse. J. 1987. “Testing for monopoly equilibrium.” Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol.35, pp. 443–56.

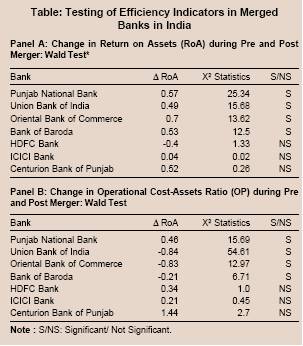

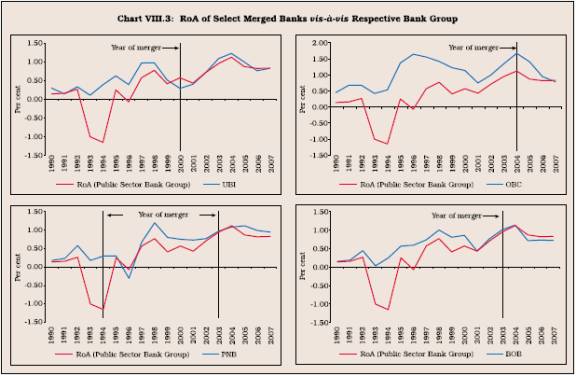

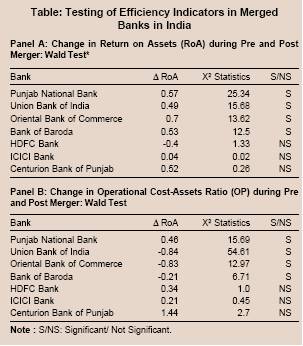

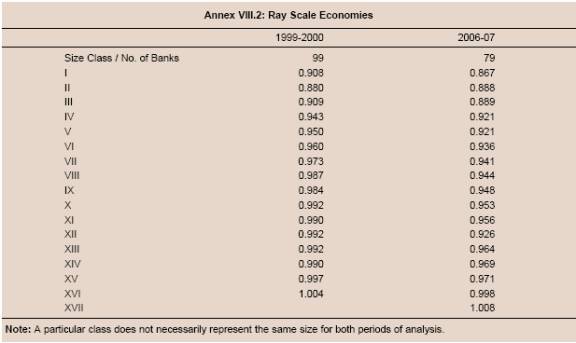

Prasad, A. and Ghosh. 2005. “Competition in Indian Banking, IMF Working Paper No. WP/05/141.