IST,

IST,

Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code and Bank Recapitalisation

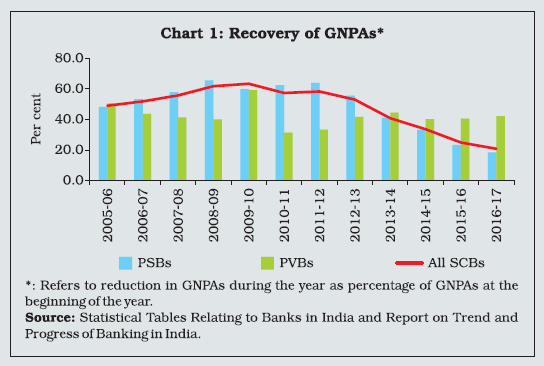

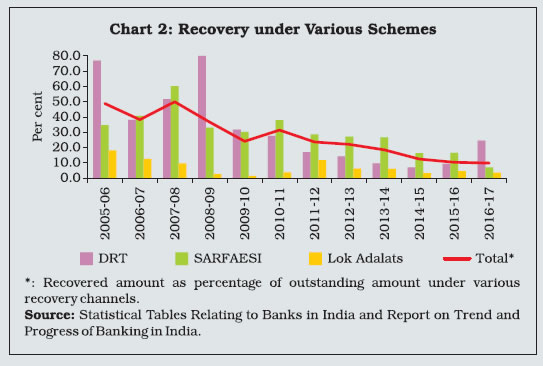

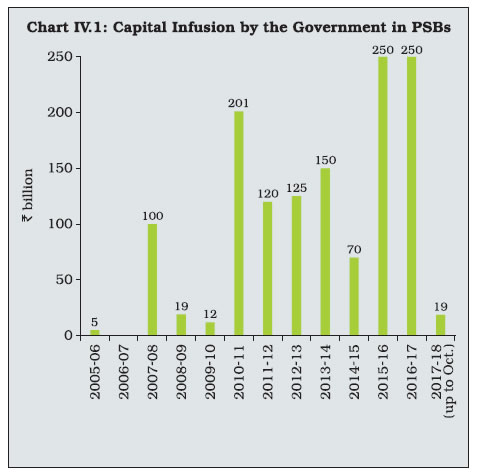

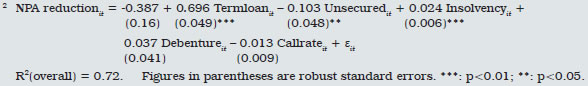

The enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 and the announcement of the recapitalisation plan for the public sector banks are likely to have far-reaching implications for the banking sector. Both will likely contribute to a stronger and more resilient banking sector in India. I. Introduction IV.1 The fulcrum of a robust and resilient banking sector is a comprehensive bankruptcy regime. It enables a sound debtor-creditor relationship by protecting the rights of both, by promoting predictability and by ensuring efficient resolution of indebtedness. A watershed development in India in this context is the enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in May 2016. IV.2 An allied development and logical concomitant is bank recapitalisation. In view of the impending move towards the full implementation of Basel III requirements and the need to meet the credit demands of a growing economy, buffering up the capital position of public sector banks has assumed priority. IV.3 Against this backdrop, Section II analyses the salient features of the IBC 2016 with some insights derived from the cross-country experience. Recapitalisation of public sector banks is addressed in Section III in the milieu of crosscountry comparisons and India’s own historical experience with recapitalisation in the 1990s. Concluding observations are set out in Section IV. II. Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 IV.4 In India, the extant legal and institutional machinery for dealing with debt default, either through the Indian Contract Act, 1872 or through special laws such as the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 and the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002 has not been utilised well by banks. Similarly, action through the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 and the winding up provisions of the Companies Act, 1956 have neither aided prompt recovery by lenders nor swift restructuring of indebted firms. IV.5 In this setting, a landmark development is the IBC, 2016 enacted and notified in the Gazette of India in May 2016. It becomes the single law that deals with insolvency and bankruptcy by consolidating and amending various laws relating to reorganisation and insolvency resolution. The IBC covers individuals, companies, limited liability partnerships, partnership firms and other legal entities as may be notified (except financial service providers) and is aimed at creating an overarching framework to facilitate the winding up of business or engineering a turnaround or exit. The IBC aims at insolvency resolution in a time-bound manner (180 days, extendable by another 90 days under certain circumstances) undertaken by insolvency professionals. Salient Features of IBC, 2016 IV.6 The institutional infrastructure under the IBC, 2016 rests on four pillars, viz., insolvency professionals; information utilities; adjudicating authorities (National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT)); and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI). Under the provisions of the Code, insolvency resolution can be triggered at the first instance of default and the process of insolvency resolution has to be completed within the stipulated time limit. IV.7 The first pillar of institutional infrastructure is a class of regulated persons – the ‘Insolvency Professionals’. They assist in the completion of insolvency resolution, liquidation and bankruptcy proceedings and are governed by ‘Insolvency Professional Agencies’, who will develop professional standards and code of ethics as first level regulators. IV.8 The second pillar of institutional infrastructure are ‘Information Utilities’, which would collect, collate, authenticate and disseminate financial information. They would maintain electronic databases on lenders and terms of lending, thereby eliminating delays and disputes when a default actually takes place. IV.9 The third pillar of the institutional infrastructure is adjudication. The NCLT is the forum where cases relating to insolvency of corporate persons will be heard, while DRTs are the forum for insolvency proceedings related to individuals and partnership firms. These institutions, along with their Appellate bodies, viz., the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) and the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal (DRAT), respectively, will seek to achieve smooth functioning of the bankruptcy process. IV.10 The fourth pillar is the regulator, viz., ‘The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India’. This body has regulatory oversight over insolvency professionals, insolvency professional agencies and information utilities. IV.11 For individuals, the Code provides for two distinct processes, namely, “Fresh Start” and “Insolvency Resolution”, and lays down the eligibility criteria for these processes. The Code also establishes a fund (the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Fund of India) for the purposes of insolvency resolution, liquidation and bankruptcy of persons. A default-based test for entry into the insolvency resolution process permits quick intervention when the corporate debtor shows early signs of financial distress. IV.12 On the distribution of proceeds from the sale of assets, the first priority is accorded to the costs of insolvency resolution and liquidation, followed by the secured debt together with workmen’s dues for the preceding 24 months. Central and State Governments’ dues are ranked lower in priority. The code proposes a paradigm shift from the existing ‘debtor in possession’ to a ‘creditor in control’ regime. Priority accorded to secured creditors is advantageous for entities such as banks. IV.13 When a firm defaults on its debt, control shifts from the shareholders / promoters to a Committee of Creditors to evaluate proposals from various players about resuscitating the company or taking it into liquidation. This is a complete departure from the experience under the Sick Industrial Companies Act under which delays led to erosion in the value of the firm. IV.14 Empirical evidence shows that a conducive institutional environment and an appropriate insolvency regime are key factors in recovery of stressed assets, apart from loan characteristics (Box IV.1). IV.15 In order to further strengthen the insolvency resolution process, the Government has notified The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Ordinance, 2017 on November 23, 2017. The Ordinance provides for prohibition of certain persons from submitting a resolution plan and specifies certain additional requirements for submission and consideration of the resolution plan before its approval by the committee of creditors.

Bankruptcy Practices: A Cross-Country Comparison3 IV.16 Bankruptcy regimes vary across countries, ranging from debtor-friendly ones in France and Italy to creditor-friendly ones in the UK, Sweden and Germany. While reorganisation is generally considered to favour debtors, liquidation primarily protects creditors. The insolvency and the debt resolution regime in the US can be classified as a hybrid one, with well-defined laws and procedures for both liquidation (Chapter 7) and restructuring (Chapter 11). Reorganisation and insolvency resolutions across a few advanced and emerging economies provide an interesting backdrop for evaluating the Indian initiative. IV.17 Pre-packaged rescue: The US and the UK allow pre-packaged rescue in which the debtor company and its creditors conclude an agreement for the sale of the company’s business prior to the initiation of formal insolvency proceedings. The actual sale is executed on the commencement of the bankruptcy proceedings. In India such a pre-packaged rescue is not allowed without the involvement of the court or the NCLT. IV.18 Initiation of bankruptcy: The US does not require proof of insolvency for a company to undergo rescue procedures under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code. In the UK, if a creditor wants to initiate a bankruptcy proceeding, it needs to produce clear evidence that an undisputed amount is due and a statutory demand has to be filed on the debtor. In India, a financial creditor, an operational creditor or the corporate debtor itself may initiate the corporate insolvency resolution process on default of ₹ 0.1 million and above. In some countries like Australia, Canada, Greece, Brazil and Russia, creditors may file only for liquidation. In the US, the UK, France, Germany, South Africa and China, creditors may file for both restructuring and liquidation. IV.19 Management of the company: The US follows a debtor-in-possession regime in which the debtor retains management control of the company and has the exclusive right to propose a plan of reorganisation during the first 120 days. In the UK, the administrator takes over the management of the company. The administrator plays a central role in the rescue process and has the power to do anything necessary or expedient for the management of the affairs, business and property of the company. In India, the powers of the board of directors of the corporate debtor are suspended and the Adjudicating Authority (i.e., NCLT) appoints an interim resolution professional. From that date, the management of the affairs of the corporate debtor vests in the interim resolution professional. A committee of creditors will approve the appointment of the interim resolution professional within 30 days of his/her appointment by the Adjudicating Authority, and subsequently approved by the Committee of Creditors with a majority vote of not less than 75 per cent of the creditors by value. IV.20 Scheme of rehabilitation: In the US, each class of impaired creditors needs to consent to the resolution plan through a vote of two-thirds of that class in volume and half the allowed claims. The US Bankruptcy Code also provides for ‘cram down’ of dissenting creditors. In the UK, acceptance of the proposal requires a simple majority (by value) of the creditors present and voting. In Germany, the plan needs to be approved by each class of creditors. In France, two committees of creditors plus a bond holders’ committee are established. One creditor committee consists of all financial institutions that have a claim against the debtor and the second creditors committee consists of all the major suppliers of the debtor. Consent must be given by each committee and requires approval of two-thirds in value of those creditors who exercise their voting rights. In India, the resolution professional constitutes a committee of creditors comprising of financial creditors (excluding those that would classify as related parties to the corporate debtor) after evaluating all claims received against the corporate debtor. All material decisions taken by the resolution professionals such as sale of assets, raising interim funding and creation of security interest have to be approved by the creditors’ committee. All decisions of the creditors’ committee have to be approved with a majority vote of not less than 75 per cent by value of financial creditors. IV.21 Moratorium: In the US, the bankruptcy law provides for an automatic moratorium on the enforcement of claims against the company and its property upon filing of a Chapter 11 petition. Similarly, the UK provides for an interim moratorium during the period between the filing of an application to appoint an administrator and the actual appointment. These moratoriums are intended to prevent a race by creditors to collect their claims, which may precipitate liquidation of the company. In India, the IBC provides for an automatic moratorium of 180 days against any debt recovery actions by the creditors, extendable by 90 days in exceptional cases. In Singapore and Brazil, the moratorium holds till the entire resolution plan is approved. IV.22 Rescue financing and grant of super-priority: In most jurisdictions, the grant of super-priority for rescue financing is allowed either through specific legislative provisions or judicial interpretation. The breakup of economically valuable businesses is primarily due to the debt overhang. To address this issue, the Bankruptcy Code of the US provides for the possibility of ‘super-priority’ being granted to creditors who provide finance to companies in distress. The UK does not provide for super-priority funding. India’s IBC also does not provide for super-priority funding. IV.23 Priority rules: Similar to the US, Finland and Chile, costs associated with insolvency proceedings have the first claim in case of liquidation of assets under India’s IBC. In countries such as the UK, Germany, France and Portugal, however, secured creditors have the first claim. In India, this is possible only after the costs associated with insolvency proceedings have been repaid. In Australia, Norway, Greece, Mexico and Colombia, employees’ salaries have the first claim in the order of priority. In India’s IBC, workmens’ compensations appear after costs associated with insolvency proceedings, pari passu with secured creditors in the waterfall of payments in liquidation, followed by unsecured creditors. The Progress under IBC so far IV.24 An analysis of the transactions under the corporate insolvency resolution process indicates that the pace of admitted cases to the IBC has picked up with time (Table IV.1). IV.25 Another interesting insight is that operational creditors have been the most aggressive in the initiation of corporate insolvency proceedings, though the number of financial creditors approaching the Board for resolution has also been increasing (Table IV.2). IV.26 The IBBI notified the IBBI (Voluntary Liquidation Process) Regulations, 2017 on March 31, 2017 which enable a corporate to liquidate itself voluntarily if it has no debt or if it is able to pay its debt in full from the proceeds of the assets to be sold under the liquidation. In pursuance of these Regulations, corporates are also tapping this route for voluntary liquidation. IV.27 The success of the IBC hinges on the development of a supportive environment consisting of trained insolvency professionals. The registration of trained insolvency professionals has gathered pace in the recent period, with the highest registrations being accounted for by the northern region (Table IV.3). IV.28 In addition to the progress made under various parameters, facilitating measures undertaken by the Reserve Bank and the SEBI are also expected to provide a boost to the resolution process. The Reserve Bank amended the Credit Information Companies (CIC) Regulation, 2006 on August 11, 2017 to allow resolution professionals to get access to credit information with CICs on the corporate debtor. The amended regulations also allow information utilities to access information as specified users. IV.29 The SEBI amended the SEBI (Substantial Acquisition of Shares and Takeovers) Regulations, 2011 on August 14, 2017 to provide exemption from open offer obligations for acquisition, pursuant to resolution plans approved under the Code. It also amended the SEBI (Issue of Capital and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2009 on the same day to exempt preferential issue of equity shares made in terms of the resolution plan approved under the Code from norms relating to preferential issue norms such as pricing and disclosures. IV.30 Subsequent to the enactment of the IBC, the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 was amended4 to empower the Reserve Bank to issue directions to any banking company or banking companies to initiate insolvency resolution in respect of a default under the provisions of the IBC. It also enables the Reserve Bank to issue directions with respect to stressed assets and specify one or more authorities or committees with such members as the Reserve Bank may appoint or approve for appointment to advise banking companies on resolution of stressed assets. IV.31 Subsequent to promulgation of the Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2017, the Reserve Bank has taken several steps to hasten the process of resolution of large value stressed accounts. The Overseeing Committee (OC) was reconstituted under the aegis of the Reserve Bank with an expanded strength of five members. The Framework for Revitalising Distressed Assets in the Economy was strengthened to address some of the inherent agency and incentive failures: i. Consent required for approval of a proposal was changed to 60 per cent by value instead of 75 per cent earlier with a view to facilitating decision making in the joint lenders’ forum (JLF); ii. Banks which were in the minority on proposals approved by the JLF are required to either exit by complying with the substitution rules within the stipulated time or adhere to the decision of the JLF; iii. Participating banks have been mandated to implement the decision of the JLF without any additional conditionality; and iv. Boards of banks were advised to empower their executives to implement JLF decisions without further reference to them, with non-adherence inviting enforcement actions. IV.32 An Internal Advisory Committee (IAC) constituted by the Reserve Bank decided on an objective, non-discretionary framework for referring some of the large stressed accounts for resolution under the IBC. Based on the IAC’s recommendations, the Reserve Bank issued directions on June 13, 2017 to certain banks for referring some accounts with fund and non-fund based outstanding amounts greater than ₹ 50 billion – with 60 per cent or more qualifying as non-performing as on March 31, 2016 – to initiate insolvency processes under the IBC, 2016. As regards other non-performing accounts which did not qualify under the above criteria for immediate reference under the IBC, banks should finalise a resolution plan within six months. In cases where a viable resolution plan is not agreed upon within six months, banks should file for insolvency proceedings under the IBC. III. Recapitalisation of Banks IV.33 Recapitalisation of banks has been a deliberate policy response the world over to repair banks’ balance sheets and potentially increase their ability to expand their credit, including in periods of stress. Equity purchases, subordinated debt or unrequited injections of cash or bonds (negotiable or non-negotiable) by governments have been undertaken. If asset values and corporate earnings are temporarily low but will recover as credit growth picks up and the economy strengthens, then support through (temporary) government capital injections provides a lifeline for potentially viable banks to survive the pangs of balance sheet distress. A Snapshot of Country Practices IV.34 Countries have devised various strategies for dealing with the stock problem related to stressed assets and for recapitalising their banking sectors. IV.35 In 1995-96, non-tradable bonds with 10-year maturity were issued in Mexico by FOBAPROA, (Fondo Bancario de Protección al Ahorro; “Banking Fund for the Protection of Savings”), a bank restructuring agency, to purchase bad assets of banks. Income from NPAs was used to redeem FOBAPROA paper. At maturity, banks wrote off 20-30 per cent of FOBAPROA paper outstanding. The Government covered the balance. In Korea, the Korean Asset Management Company (KAMCO) issued tradable bonds in 1998-99 to purchase banks’ bad assets and equities5. IV.36 During 1998-99, zero coupon bonds with market-based yield were issued by Danaharta, a government owned asset management company (AMC) in Malaysia, to finance the purchase of banks’ bad assets. Further, Danamodal, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) of the Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), was established in 1998 to assess recapitalisation requirements of banks, undertake the recapitalisation exercise, restructure the affected institutions and monitor performance. Bank Negara Malaysia provided the initial seed capital of RM 1.5 billion. Danamodal injected capital into banking institutions after the institutions had sold their NPAs to Danaharta, but only to viable banking institutions, based on an assessment and diligent review by financial advisers. The capital injection was in the form of equity or hybrid instruments. IV.37 In Thailand, the Government issued recapitalisation bonds in 1999-2000 to purchase bank equity. The bonds were tradable. Non-tradable recapitalisation bonds were also issued to purchase bank debentures. Both were of maturity of 10 years with market-related fixed interest rates. IV.38 In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, several developed countries announced comprehensive rescue packages involving some combination of recapitalisation, debt guarantees and asset purchases. Capital injections in the Netherlands amounted to 5.1 per cent of GDP in 2008, in the UK (3.4 per cent), US (2.1 per cent), France (1.4 per cent) and Japan (0.1 per cent). Country practices differed widely in terms of the features of the recapitalisation plan (Table IV.4). Recapitalisation of Public Sector Banks in India: Early Phase IV.39 During 1993-94, the application of the first stage of prudential accounting standards and capital adequacy norms necessitated strengthening of capital positions of India’s nationalised banks. The Government of India contributed ₹ 57 billion as equity to recapitalise nationalised banks and issued 10 per cent Government of India Nationalised Banks’ Recapitalisation Bonds, 2006 on January 1, 1994. Recipient banks were required to invest the Government’s capital subscription in these bonds. IV.40 The important features of the bonds were: (i) they carried an interest rate of 10 per cent per annum to be paid at half-yearly intervals; (ii) they were repayable in six equal annual installments on the first day of January from the year commencing January 1, 2001 and onwards; (iii) they were transferable; (iv) they were not an approved security for purposes of the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR); and (v) the bonds were considered as eligible securities for purposes of obtaining a loan from any bank or financial institution. During 2006-07, these bonds were converted into tradable SLR-eligible Government of India dated securities. IV.41 The recapitalisation of nationalised banks was undertaken to ensure that all the banks were able to meet the minimum capital to risk-weighted assets ratio of 4 per cent by the end of March 1993 and also to maintain their capital unimpaired. To strike a balance between fiscal adjustment and bank capital strengthening, banks were allowed to invest in bonds of a finite tenor, so that, in addition to receipt of interest income, banks would receive a gradual inflow of principal over time. IV.42 The release of capital by the Government was subject to the participating public sector banks undertaking certain performance obligations and commitments in respect of parameters such as changes in operational policies and in organisational structure, and use of upgraded technology to ensure an improvement in viability and profitability. Moreover, banks were required to chalk out plans to ensure excellence in customer service and maintenance of a high level of efficiency in providing various services; to improve their position through repayment and additional securities and documentation in respect of all non-performing assets above ₹ 10 million; formulate liability/investment management and loan policies; and outline capital expenditure and human resources development policies. The total amount of capital injected into the public sector banks during 1992-93 to 1998-99 amounted to ₹ 204 billion. IV.43 The Indian banking sector escaped largely unscathed from the turmoil of the global financial crisis in view of limited exposures to toxic assets and proactive regulatory measures undertaken in response to fast growth in credit during the precrisis period. However, to ensure that banks maintain Tier I capital adequacy ratio in excess of 8 per cent, the Government started undertaking capital infusion programme since 2007-08 onwards. A cumulative amount of ₹ 131 billion was injected in PSBs during 2007-08 to 2009-10. Capital infusion by the government continued in subsequent years as well, wherein an attempt was made to link it with bank performance. A total amount of ₹ 666 billion was injected in PSBs during 2010-11 to 2014-15 (Chart IV.1). Recapitalisation of Public Sector Banks: Recent Initiatives IV.44 As part of the Indradhanush plan in August 2015, the Government estimated PSBs’ capital requirements at ₹ 1.8 trillion during 2015-16 to 2018-19, out of which ₹ 700 billion consisted of budgetary allocations and the remaining ₹ 1.1 trillion was to be raised by these banks from the market and by divesting their non-core assets. So far, under the Indradhanush plan, Government has infused capital of ₹ 519 billion in PSBs. The parameters considered for capital infusion in banks are capital requirements of respective banks; size of the banks; performance of the banks with reference to efficiency; growth of credit and deposits; reduction in the cost of operations; and potential for growth. In addition, PSBs have so far (up to October 24, 2017) been able to raise ₹ 213 billion from the market. IV.45 In October 2017, the Government announced a large-scale bank recapitalisation plan of ₹ 2.11 trillion to reinvigorate PSBs struggling with high levels of stressed advances. Out of the ₹ 2.11 trillion, ₹ 1.35 trillion will be through recapitalisation bonds and the remaining ₹ 760 billion will be provided through budgetary support (around ₹ 180 billion) and by banks raising resources from the market (₹ 580 billion). Recapitalisation will take place over the rest of 2017-18 and 2018-19, but the Government intends to frontload the programme. IV.46 The proposed recapitalisation package combines several desirable features. By deploying recapitalisation bonds, it will front-load capital injections while staggering the attendant fiscal implications over a period of time. As such, the recapitalisation bonds will be liquidity neutral for the Government except for the interest expenses that will contribute to the annual fiscal deficit. It will involve participation of private shareholders of PSBs by requiring that parts of their capital needs be met by market funding. Furthermore, it will set up a calibrated approach whereby banks that have addressed their balance-sheet issues and are in a position to use fresh capital injection for immediate credit creation can be given priority while others shape up to be in a similar position. This is expected to bring market discipline into a public recapitalisation programme6. IV. Summing Up IV.47 Banks are the key financial intermediaries in India. Asset stress has hampered credit growth at a time when the financing needs for accelerating the pace of economic activity have emerged as the highest priority. The two-pronged approach in the form of the IBC, 2016 and the recapitalisation of banks is expected to aid a fast er clean-up of banks’ balance sheets. The combination of linking the performance of the banks with the quantum of funds injected through recapitalisation is expected to bring in discipline and disincentivise the recurrence of forbearance and stress. 1 Reduction in GNPAs during the year to outstanding GNPAs at the beginning of the year. 3 Material for preparing this sub-section has been drawn from i. Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2016), “Insolvency Regimes and Productivity Growth: A Framework for Analysis”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1309. 4 Vide Banking Regulation (Amendment) Ordinance, 2017 (the Ordinance), subsequently enacted as Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2017. 5 Andrews, Michael (2003), “Issuing Government Bonds to Finance Bank Recapitalisation and Restructuring: Design Factors That Affect Banks’ Financial Performance”, IMF Policy Discussion Paper, PDP/03/4, International Monetary Fund. 6 Patel, Urjit R. (2017), “RBI welcomes bank recapitalisation plan”, Governor’s Statement, October 25, 2017, Reserve Bank of India, Retrieved on November 11, 2017 from /en/web/rbi/-/press-releases/governor-s-statement-42055. |

పేజీ చివరిగా అప్డేట్ చేయబడిన తేదీ: