IST,

IST,

VI Management of Capital Flows (Part 3 of 3)

Foreign Aid and Millennium Goals

6.96 Through a broad-based consensus, the United Nations Millennium Summit in September 2000 framed time-bound and measurable goals and targets [Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)] to address poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation and gender bias. It was envisaged during the Summit that many countries would not be able to reach these targets unless they receive substantial external support including and in the form of advocacy, expertise and resources.

6.97 The pace of progress on MDGs has been both slow and uneven across countries (United Nations, 2003). In the recent discussions of the United Nations meeting in Monterrey, Mexico, the United States and the European Union agreed to expand their aid programmes which could lead to some increase in aid but not sufficient to meet the MDGs. The donors have also signalled the need for effective utilisation of aid. Many industrialised countries have cited their own domestic considerations including fiscal problems.

6.98 The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative launched in 1996 to reduce the debt burden of the world’s poorest and most heavily indebted countries has made substantial progress in the recent period with six countries having received irrevocable debt relief by September 2002 under the enhanced HIPC Initiative. An additional 20 countries have begun

to receive interim debt relief. Availability of long-term external financing on sufficiently concessional terms to support poverty reduction and growth strategies is important for the sustainability of HIPCs. The agreement under IDA-13 to provide a proportion of IDA resources in the form of grants to particularly vulnerable low-income countries will be an important step forward in this regard (World Bank, 2003).

6.99 External assistance with high element of concessionality played a significant role in the development process in India till the early 1980s. For most of this period, external assistance formed almost 100 per cent of the capital account flows. During the 1980s, however, the share of external assistance in the capital account declined as the widening current account deficit necessitated recourse to additional sources of foreign savings such as commercial borrowings and nonresident deposits. On an average, external assistance formed almost one-half of capital account during 1980s, which declined to around 11 per cent in the second-half of 1990s. The lower recourse to official aid was also attributed to other factors such as structural changes in global capital flows, lack of matching resources, delays involved in project appraisals and tender finalisation due to administrative bottlenecks, lack of cost related tariff structure for power and delays in land acquisition. Net inflows to India, as a result, fell sharply during the 1990s (Table 6.18). Net officials inflows to developing countries as a group have also been sluggish (Table 6.19).

|

Table 6.18: Trends in External Aid: India |

|||||||||

|

(US $ million) |

|||||||||

|

Authorisation |

Utilisation |

Debt |

Net |

Aid Utilisa- |

|||||

|

Servicing |

inflows |

tion Ratio(%) |

|||||||

|

Year |

Loans |

Grants |

Total@ |

Loan |

Grants |

Total # |

|||

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) = |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) = |

(8) |

(9) = |

(10) = |

|

(2)+(3) |

(5)+(6) |

(7) – (8) |

(7)/(4) |

||||||

|

1970s |

1,533.9 |

302.8 |

1,858.0 |

1,219.3 |

186.9 |

1,436.5 |

799.5 |

636.9 |

83.6 |

|

1980s |

4,596.5 |

352.7 |

4,949.2 |

2,385.9 |

372.5 |

2,758.4 |

1,390.9 |

1367.5 |

61.1 |

|

1990s |

3,828.1 |

454.8 |

4,282.9 |

3,271.8 |

286.7 |

3,558.4 |

3,120.0 |

438.4 |

83.1 |

|

1990-91 |

4,236.4 |

291.0 |

4,527.4 |

3,438.7 |

297.8 |

3,736.5 |

2,398.0 |

1338.5 |

82.5 |

|

1991-92 |

4,766.0 |

364.1 |

5,130.1 |

4,317.9 |

371.0 |

4,688.9 |

2,688.0 |

2000.9 |

91.4 |

|

1992-93 |

4,275.7 |

330.7 |

4,606.4 |

3,301.8 |

287.5 |

3,589.3 |

2,814.0 |

775.3 |

77.9 |

|

1993-94 |

3,717.5 |

772.7 |

4,490.2 |

3,486.0 |

283.4 |

3,769.4 |

3,055.0 |

714.4 |

83.9 |

|

1994-95 |

3,958.2 |

343.8 |

4,302.0 |

3,184.8 |

292.7 |

3,477.5 |

3,315.0 |

162.5 |

80.8 |

|

1995-96 |

3,249.8 |

399.0 |

3,648.8 |

2,987.4 |

319.1 |

3,306.4 |

3,699.0 |

-392.5 |

90.6 |

|

1996-97 |

4,000.4 |

825.6 |

4,826.0 |

3,066.8 |

305.6 |

3,372.4 |

3,320.0 |

52.4 |

69.9 |

|

1997-98 |

4,006.8 |

566.3 |

4,573.1 |

2,917.4 |

248.3 |

3,165.7 |

3,120.0 |

45.7 |

69.2 |

|

1998-99 |

1,979.2 |

49.9 |

2,029.1 |

2,936.0 |

213.0 |

3,149.0 |

3,314.0 |

-165.0 |

155.2 |

|

1999-00 |

4,091.4 |

604.4 |

4,695.8 |

3,080.8 |

248.2 |

3,329.0 |

3,477.0 |

-148.0 |

70.9 |

|

2000-01 |

3,769.3 |

206.3 |

3,975.6 |

2,967.2 |

159.5 |

3,126.7 |

3,664.0 |

-537.3 |

78.6 |

|

2001-02 |

4,438.7 |

711.1 |

5,149.8 |

3,306.3 |

297.1 |

3,603.4 |

3,271.0 |

332.4 |

70.0 |

|

2002-03 |

4,183.0 |

260.0 |

4,443.0 |

2,946.5 |

386.0 |

3,332.5 |

6,091.1 |

-2,758.6 |

75.0 |

|

@ The total also includes PL 480 etc. payable in foreign currency of US $ 30.1 million in 1971-72 ; payable in rupees of US $ 128.7 million in |

|||||||||

|

1971-72 , US $ 23 million in 1975-76, US $104.3 million in 1976-77 and US $ 26.6 million in 1977-78. |

|||||||||

|

# The total also includes PL 480 etc. payable in foreign currency of US $ 49.9 million in 1970-71 and US $11.8 million in 1971-72; payable in rupees of US $ 67.9 million in 1970-71 ,US $ 138.0 million in 1971-72, and US $ 5.6 million in 1972-73 |

|||||||||

|

Source: Economic Survey, Government of India (various issues). |

|||||||||

MANAGEMENT OF CAPITAL FLOWS

|

Table 6.19: Net Official Financing of Developing Countries |

||||||||||

|

(US $ billion) |

||||||||||

|

Item |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

||

|

1. |

Total (2+3) |

71.6 |

31.6 |

39.7 |

62.3 |

42.9 |

23.4 |

57.5 |

49.1 |

|

|

2. |

Grants |

32.8 |

27.8 |

26.7 |

28.2 |

29.4 |

29.6 |

29.5 |

32.9 |

|

|

3 |

Net Lending |

(4+11) |

38.8 |

3.8 |

13.0 |

34.1 |

13.5 |

-6.2 |

28.0 |

16.2 |

|

4. |

Multilateral |

(5+6+7+8=9+10) |

28.2 |

14.0 |

19.9 |

37.4 |

15.7 |

0.9 |

35.7 |

21.3 |

|

5. |

World Bank Group |

6.3 |

7.3 |

9.2 |

8.7 |

8.8 |

7.8 |

7.5 |

1.5 |

|

|

IBRD |

1.4 |

1.5 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

2.5 |

-4.1 |

||

|

IDA |

4.9 |

5.7 |

5.3 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

5.0 |

5.6 |

||

|

6. |

Major Regional Development Banks@ |

5.1 |

4.6 |

6.3 |

8.6 |

9.0 |

6.2 |

6.5 |

1.9 |

|

|

7. |

IMF |

16.8 |

1.0 |

3.4 |

14.1 |

-2.2 |

-10.6 |

19.5 |

14.5 |

|

|

8. |

Other |

0.0 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

5.9 |

0.1 |

-2.5 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

|

|

9. |

Concessional |

8.8 |

8.5 |

7.6 |

7.4 |

7.0 |

5.6 |

7.2 |

9.3 |

|

|

10. |

Non-concessional |

19.4 |

5.5 |

12.3 |

30.0 |

8.8 |

-4.7 |

28.5 |

12.0 |

|

|

11. |

Bilateral (12+13) |

10.5 |

-10.2 |

-6.9 |

-3.3 |

-2.3 |

-7.1 |

-7.7 |

-5.1 |

|

|

12. |

Concessional |

5.5 |

2.7 |

0.0 |

2.5 |

5.1 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

|

|

13. |

Non-concessional |

5.0 |

-12.9 |

-6.9 |

-5.9 |

-7.3 |

-8.4 |

-9.3 |

-6.9 |

|

|

@ Inter-American Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, |

European |

Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

and African |

|||||||

|

Development Bank. |

||||||||||

|

Source: Global Development Finance, World Bank, 2003. |

||||||||||

6.100 In recent years, the Government of India has decided to pre-pay costly external aid. The Government pre-paid US $ 3.0 billion of high cost multilateral debt in February 2003 and US $ 1.6 billion in November 2003. The Government of India has also decided to discontinue receiving aid from bilateral partners other than Japan, UK, Germany, USA, EC and Russian Federation and has already prepaid bilateral debt amounting to US $ 0.6 billion in 2003.

6.101 Given the nature of external assistance and its relation to the level of development of the economy, an exercise was under taken to assess the determinants of the inflows and outflows of external assistance in India over the period 1970-71 to 2002-03. The inflows under external assistance were expected to depend on the level of development proxied by the gross domestic product at factor cost (GDPFC) and the debt service ratio in the previous period. The results validate the assumption that the

external assistance into India depended on the level of economic activity as proxied by GDPFC.11 On the other hand, the outflows on account of external assistance, which are, scheduled repayment obligations, were, as expected, found to depend on the outflows during the last period and the activity variable. Both the variables turned out to be significant.

6.102 Despite differing viewpoints, the role of external assistance in the development process of developing countries cannot be over emphasised. In the absence of alternative sources of funds, external assistance emerged as a major financing item in the capital account of the balance payments as was the case with India till the early 1980s. In recent years, however, the policy towards management of external liabilities has changed and the initiative is towards attracting private capital flows, especially non-debt creating direct investment inflows.

|

11 |

Ln EXTASSR |

= |

-7.38 |

+ |

0.59 Ln EXTASSR{-1} + |

0.79 Ln GDPFC + |

0.02 DSR{-1} |

|||||||

|

(-2.23)** |

(3.73)*** |

(2.33)** |

(2.75)*** |

|||||||||||

|

– |

||||||||||||||

|

R2 |

= |

0.97 |

h = 0.36 |

SEE = 0.18 |

||||||||||

|

Where EXTASSR |

= |

Inflows under external assistance; |

GDPFC = Gross domestic product at factor cost; DSR = Debt service ratio |

|||||||||||

|

Ln EXTASSP |

= |

-18.08 |

+ |

0.27 Ln EXTASSP{-1} + |

1.76 Ln GDPFC + |

0.37 DUMEXTASSP |

||||||||

|

(-3.40)*** |

(1.27) |

(3.50)*** |

(2.19)** |

|||||||||||

|

– |

||||||||||||||

|

R2 |

= |

0.98 |

h = 0.82 |

SEE = 0.19 |

||||||||||

|

Where EXTASSP |

= |

Outflows under external assistance; GDPFC= Gross domestic product at factor cost; |

||||||||||||

|

DUMEXTASSP |

= |

Dummy variable to account for large increase in repayments since 1991-92. |

||||||||||||

|

Figures in brackets are t-values; ***, ** and * denote the 1, 5 and 10 per cent level of significance, respectively. |

||||||||||||||

VIII. TRANSACTIONS WITH THE

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND (IMF)

6.103 The Financial Transaction Plan (FTP) of the IMF essentially reflects the cooperative spirit underlying the financial transactions with its members. Under the FTP, members with strong balance of payments (BoP) and foreign exchange reserves enable the IMF to finance the BoP needs of countries with BoP imbalances. Thus, the position of an IMF member could, over time, change from one of debtor to creditor vis-à-vis the IMF, depending on the member’s BoP and foreign exchange reserve position. Participation in FTP as a creditor has a positive signalling effect at the international level. In a way, it amounts to international recognition of the strength and resilience of a country’s external sector. Moreover, participation in FTP does not alter either the total quota contribution or the total foreign exchange reserves of a country, but only the composition of quota and foreign exchange reserves.

6.104 India became a member of the IMF’s FTP from the quarter September-November, 2002 in view of its strong BoP and comfortable foreign exchange reserve position. Depending on the extent of its participation in the FTP, India’s Reserve Tranche Position (RTP) in the IMF would increase on which the IMF would pay remuneration at market related rates. Based on the expected purchase (borrowing) needs of the members, IMF prepares a quar terly FTP indicating the expected total amount that all creditor countries may have to provide during any quarter. The actual transfers are generally less than what is planned. In the quarters September-November 2002 and December 2002-February 2003, India was allocated SDR 156 million and SDR 128 million, respectively. As the actual demand from the borrowing members was much less than what was planned under the FTP for both the quarters, India was not required to effect any actual transfer during those two quarters. This situation changed in the subsequent quarters. India was allocated SDR 140 million for the quarter March-May, 2003 but the actual utilisation was only SDR 5 million effected on May 07, 2003 for the first time. During June-August 2003, India was allocated SDR 303 million of which the actual transfer for India was SDR 200 million. During September-November 2003, India was allocated SDR 304 million and the actual transfer for India was SDR 150 million. India has, thus, become a creditor to the IMF – a long way from the situation in 1981 when it was the largest borrower.

IX. SURGES IN CAPITAL FLOWS AND

CONDUCT OF MONETARY POLICY

6.105 Reflecting the progressive globalisation of the Indian economy since the 1990s, capital flows increased from an average of US $ 5.8 billion per annum (Rs. 8,225 crore) during the second half of the 1980s to US $ 9.1 billion (Rs. 35,354 crore) billion during the second half of the 1990s and further to US

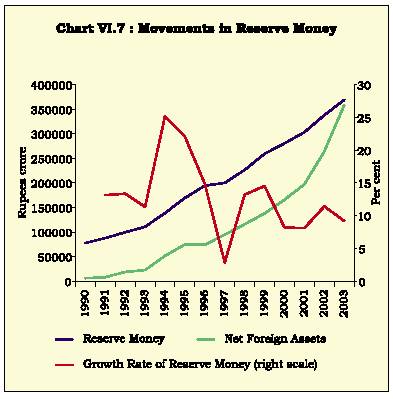

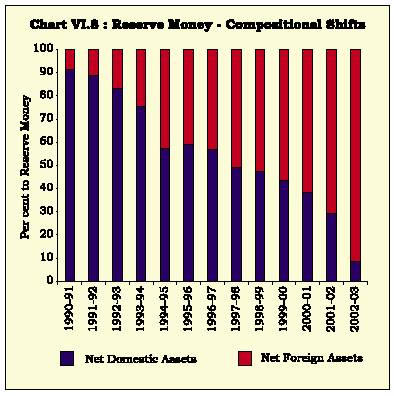

$ 12.1 billion (Rs.58,506 crore) during 2002-03. At the same time, the current account deficit declined significantly, before turning into a surplus in 2001-02 and 2002-03, in turn, resulting in a large and growing surplus in the overall balance of payments. The concomitant excess supply in the foreign exchange market has been absorbed by the Reserve Bank in line with its stance on exchange rate management and with a view to building-up foreign exchange reserves. In the process, the net foreign assets of the Reserve Bank increased multifold from Rs. 6,068 crore at end-March 1990 to Rs. 4,68,745 crore by January 16, 2004. As a result, the share of net foreign assets (NFA) in reserve money increased from 7.8 per cent to more than 100 per cent (119 per cent) over the same period (Charts VI.7 and VI.8).

6.106 The absor ption of these flows has expansionar y impact on money supply with implications for price as well as financial stability. This necessitates the neutralisation of the expansionary impact of external flows (see Chapter III). In general, apart from exchange rate flexibility and foreign exchange market intervention there are several other

policy responses that can be used to manage large capital inflows. These include: (i) trade liberalisation leading to a higher trade and current account deficit which would enable the economy to absorb the capital inflows; (ii) investment promotion through measures designed to facilitate greater investment in the economy; (iii) liberalisation of the capital account; (iv) management of external debt through pre-payment and moderation in the access of corporates and intermediaries to additional external debt; (v) management of non-debt flows like foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investments; (vi) taxation of inflows such as the imposition of a 'Tobin' type tax; and, (vii) use of foreign exchange reserves for productive domestic activities through on-lending in foreign currencies to residents (RBI, 2003c).

6.107 In India, a number of steps have been taken to manage the excess supply in the foreign exchange market. These include a phased liberalisation of the policy framework in relation to current as well as capital accounts. Efforts to moderate capital flows have been focused on a number of measures, as discussed earlier in this chapter, such as minimum maturity prescriptions and interest rate ceilings on non-resident rupee deposits. In regard to capital outflows, the automatic route of FDI abroad has been substantially expanded. Similarly, corporates have been provided greater flexibility with regard to the prepayment of their external commercial borrowings. Surrender requirements for exporters have been liberalised to enable them to hold up to 100 per cent of their proceeds in foreign currency accounts; foreign

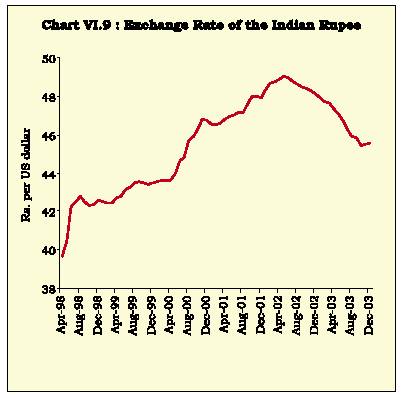

currency account facilities have been extended to other residents; and banks have been allowed to liberally invest abroad in high quality instruments. A significant step in this process was the pre-payment of a part of the debt owed to multilateral and bilateral agencies by the Government of India. Furthermore, in 2002-03, the exchange rate of the rupee vis-à-vis the US dollar appreciated, an event unprecedented in the recent monetary history of India (RBI 2003). The appreciation of rupee vis-à-vis the US dollar has continued during 2003-04 so far (Chart VI.9).

6.108 Notwithstanding the measures undertaken by the Reserve Bank, the overall balance of payments surplus has continued to increase in the last few years. The net foreign assets of the Reserve Bank have also increased sharply. As a result, the major instrument of managing capital flows in India has been sterilisation - open market operations involving sale of Government of India securities from the Reserve Bank’s portfolio and repo transactions - in order to offset the liquidity created by the purchases of foreign currency from the market (Table 6.20). Accordingly, the share of net domestic assets in reserve money declined throughout the 1990s. In particular, the stock of the Government of India securities - the main instrument of sterilisation - declined from Rs.1,46,534 crore at end-March 2001 to Rs.36,919 crore by January 16, 2004 (Chart VI.10).

6.109 The cross-country experience with regard to the management of capital flows suggests a menu of possible approaches ranging from liberalization

|

Table 6.20: Accretion to Foreign Exchange Reserves and Open Market Operations |

||||||

|

(Rupees Crore) |

||||||

|

Year |

Accretion to Foreign |

Open Market Purchases |

Open Market Sales |

Net OMO Sales |

Net OMO Sales |

(net of |

|

Exchange Reserves |

Private Placements and |

|||||

|

Devolvements) |

||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 = 4-3 |

6 |

|

|

1996-97 |

20,548 |

623 |

11,206 |

10,583 |

6,885 |

|

|

1997-98 |

20,973 |

467 |

8,081 |

7,614 |

-5,414 |

|

|

1998-99 |

22,100 |

0 |

26,348 |

26,348 |

-11,857 |

|

|

1999-00 |

27,908 |

1,244 |

36,614 |

35,370 |

8,370 |

|

|

2000-01 |

31,291 |

4,471 |

23,795 |

19,324 |

-11,827 |

|

|

2001-02 |

66,832 |

5,084 |

35,419 |

30,335 |

1,443 |

|

|

2002-03 |

94,244 |

0 |

53,402 |

53,402 |

17,605 |

|

|

2003-04 (Apr-Dec) |

1,06,190 |

0 |

36,517 |

36,517 |

31,517 |

|

|

Source: |

Reserve Bank of India. |

|||||

of outflows to punitively high non-remunerated reserve requirements. These measures can broadly be classified into (i) use of market-based instruments (i.e., instruments of sterilisation) and (ii) non-market based measures involving, inter alia, control on inflows and liberalisation of outflows (RBI, 2003c). Besides making use of well known instruments of sterilisation such as open market operations (including repos) with the help of government securities and foreign exchange swaps, there exists a wide variety of other instruments, ranging from provision for remunerated/uncollateralised deposit facilities for financial intermediaries with central banks (viz., China, Taiwan and Malaysia), issuance by the central bank of money stabilisation bonds/ central bank bills (viz., Korea, China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Poland and Peru), and Government/Public Sector deposits with the

central bank (viz., Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Peru). Countries have also used Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) on domestic/foreign deposits (on remunerated/non-remunerated basis) to absorb liquidity (China and Taiwan). There are several countries that have liberalised capital outflows (China and Taiwan). Among the countries that have imposed capital control on short term capital inflows, mention may be made of Thailand, China, Taiwan and Malaysia. Latin American countries, such as, Chile and Colombia adopted the policy of unremunerated reserve requirements. Countries have also used variants of 'Tobin' taxes on capital inflows (viz., Brazil and Chile) (Box VI.7).

6.110 With the continued surges in capital flows in the recent period, countries like Thailand, China and Taiwan have undertaken several measures to manage them (Box VI.8).

6.111 As noted above, sterilisation operations have been the principal instrument of managing capital flows in India. Unsterilised intervention in foreign exchange markets could lead to an alignment of domestic interest rates with international interest rates which could have beneficial effects on investment and growth (RBI, 2003c). In the short run, however, unsterilised intervention could lead to asset price volatility, imprudent lending and adverse selection which could have inimical effects on the real economy with possibilities of capital flow reversals. There is a broader agreement on the policy response of sterilisation as a temporary measure since it addresses temporary inflows effectively, and can be implemented quickly. Moreover, if the inflows are more enduring in nature, it provides some breathing space to formulate a longer term response. Even in the case of mixed flows – enduring and short term – some degree of sterilisation is often considered necessary. The arguments in favour of sterilisation are that it

Box VI.7

Management of Capital Inflows: Restrictions and Prudential Requirements – Country Experiences

Indonesia (1990)

• Measures imposed to discourage offshore borrowing, including limits on banks’ net open-market foreign exchange positions and on off-balance-sheet positions. The three-month swap premium raised by 5 percentage points.

• All state-related offshore commercial borrowing made subject to prior approval and annual ceilings were set for new commitments over the next five years.

Malaysia (1989)

• Limits on non-trade-related swap transactions imposed on commercial banks.

• Banks subjected to a ceiling on their non-trade- or non-investment-related external liabilities.

• Residents prohibited from selling short-term monetary instruments to non-residents.

• Commercial banks were required to place with Bank Negara the ringgit funds of foreign banking institutions (Vostro accounts) held in non-interest-bearing accounts. During January-May 1994, these accounts were considered part of the eligible liabilities base for the calculation of required reserves, resulting in a negative effective interest rate on Vostro balances.

Philippines (1992)

• Bangko Central begins to discourage forward cover arrangements with non-resident financial institutions.

Thailand (1988)

• Banks and finance companies (a) net foreign exchange positions not to exceed 20 per cent of capital (subsequently increased to 25 per cent) and (b) net foreign liabilities not to exceed 20 per cent of capital.

• Residents disallowed from holding foreign currency deposits except only for trade-related purposes.

• Reserve requirements, to be held in the form of non-interest-bearing deposits at the Bank of Thailand, on short-term non-resident baht accounts raised from two to seven per cent. The seven per cent reserve requirement extended to finance companies short-term (less than one year) promissory notes held by nonresidents. Offshore borrowing with maturities of less than one year (excepting loans for trade purposes) by commercial banks, finance companies, and finance and security companies also subjected to 7 per cent minimum reserve requirement.

investment in the stock market, (b) tax on Brazilian companies issuing bonds overseas raised from 3 to 7 per cent of the total and (c) tax paid by foreigners on fixed-interest investments in Brazil raised from 5 to 9 per cent.Chile (1990)

• Non-remunerated 20 per cent (subsequently increased to 30 per cent) reserve requirement (to be deposited at the central bank for a period of one year) on liabilities in foreign currency for direct borrowing by firms.

• The stamp tax of 1.2 per cent a year (previously paid on domestic currency credits only) applied to foreign loans as well (excepting trade loans).

Colombia (1991)

• A 3 per cent withholding tax imposed on foreign exchange receipts from personal services rendered abroad and other transfers (but allowed to be claimed as credit against income tax liability).

• Banco de la Republica increased its commission on its cash purchases of foreign exchange from 1.5 to 5 per cent.

• Non-remunerated reser ve requirement to be deposited at the central bank on liabilities in foreign currency for direct borrowing by firms. The reserve requirement to be maintained for the duration of the loan and applied to all loans with a maturity of five years or less, except for trade credit with a maturity of four months or less. The percentage of the requirement declined as the maturity lengthened, from 140 per cent for funds that are 30 days or less to 42.8 per cent for five-year funds.

Czech Republic (1992)

• The central bank introduced a fee of 0.25 per cent on its foreign exchange transactions with banks, with the aim of discouraging short-term speculative flows.

• Limit on net short-term (less than one year) foreign borrowing by banks introduced.

• Each bank to ensure that its net short-term liabilities to non-residents, in all currencies, do not exceed the lower of 30 per cent of claims on non-residents or Kc 500 million.

• Administrative approval procedures imposed to slow down short-term borrowing by non-banks.

Mexico (1990)

• Foreign currency liabilities of commercial banks limited to 10 per cent of their total loan portfolio. Banks had to place 5 per cent of these liabilities in highly liquid instruments.

Eastern Europe and Latin America

Brazil (1992)

• Between October 1994 and March 10, 1995, following measures imposed: (a) one per cent tax on foreign

Note : Dates in brackets refer to the first year of the surge in inflows Source : Reinhart and Smith (1998).

Box VI.8

Management of Capital Inflows: Recent Experience of Thailand, China and Taiwan

In the latest episode of surges in capital flows, Thailand has imposed a variety of measures including restrictions to limit speculative short-term capital flows, liberalisation of capital outflows, resort to massive pre-payment of external debt, tightening of fiscal policy and a flexible exchange rate. Restrictions on interest payments have been imposed, effective October 14, 2003, on short-term borrowing in Baht from non-residents to prevent Thai Baht speculation. These include: (i) non-residents can maintain only current or saving accounts for settlement of international trade and investment transactions; deposits for other purposes must have maturity of at least six months; (ii) a deposit ceiling of 300 million Baht (equivalent of around US $ 7.5 million) per non-resident account; and (iii) financial institutions not to pay interest to overseas holders of Thai cheque and savings accounts. The liberalisation measures include: (i) permission to institutional investors to invest in overseas securities; (ii) encouragement to mutual funds to invest on behalf of local residents in Asian bonds issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities; and (iii) increase in the holding period of foreign currency deposits from 3 to 6 months. The external debt more than halved from a peak of US $ 112 billion in June 1997 to US $ 52 billion by July 2003. Furthermore, substantial fiscal correction – public debt/ GDP ratio has declined from 57 per cent to 50 per cent of GDP during 2003 – has also been witnessed (Devakula, 2003).

China has managed capital flows through increase in base money as well as sterilisation by issuing its own bills. From April 22, 2003 the People’s Bank of China (PBC) started outright issue of central bank bills with maturities up to one year. By the end of September 2003, 42 issues cumulating to RMB 545 billion yuan had been made. The

outstanding issues reached RMB 425 billion yuan (about 4 per cent of GDP). In the context of sustained capital flows, the PBC decided to coordinate the issue of central bank bills with a one percentage point increases in the cash reserve ratio to 7 per cent effective September 21, 2003. Moreover, the PBC liberalised capital outflows through measures such as reforming the current account administration, allowing enterprises to retain more foreign exchange, lifting the limits for individuals to buy and carry foreign currencies when traveling abroad. Furthermore, it carried out a pilot programme on foreign exchange administration of overseas investment to widen channels for outward capital flows. International financial institutions have also been permitted to issue local currency RMB bonds in the domestic market.

Taiwan has sterilised capital flows through open market operations (OMOs) by employing government securities and, in the recent period, through issue of its own negotiable cer tificates of deposits (NCD). These instruments are issued or sold on outright basis as well as under repurchase agreements. In addition, Taiwan has absorbed liquidity through redeposits from financial institutions and depositing a part of the foreign exchange reserves in the overseas branches of domestic banks to promote their international financial activities and to support Taiwanese firms operating overseas. Capital outflows have been encouraged by permitting (i) international financial institutions such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank to issue local currency bonds and (ii) domestic securities investment and trust companies to raise funds from the domestic market to invest in foreign securities under an aggregate ceiling.

keeps base money and money supply unchanged, thereby avoiding the undesirable expansionary effects of capital inflows. Furthermore, foreign exchange market intervention accompanied by sterilisation allows the monetary authority to build up international reserves that could help to withstand future shocks, and provide comfort and confidence to market participants. On the other hand, prolonged sterilisation may exert an upward pressure on interest rates, which could, in turn, attract further foreign exchange inflows neutralising the impact of sterilisation. Sterilisation also has its financial costs: if it is conducted through OMO, the net cost of sterilisation to the central bank is the difference between the interest rate on domestic securities and the rate of return on foreign exchange reserves adjusted for any exchange rate change. The magnitude of the cost varies with the extent of sterilisation and the yield differentials. These are

termed 'quasi-fiscal' costs since the costs to the central bank are passed on to the sovereign through a lower transfer of profits. Similarly, when sterilisation is effected through an increase in reserve requirements, this could adversely affect the profitability of the financial system as it is a tax on banks and could give rise to dis-intermediation. Sterilisation as a process, therefore, involves a range of costs and benefits. On balance, there must be adequate preparedness to undertake sterilisation operations, which includes availability of instruments. The need for and size of such operations is, however, governed by several larger policy considerations. At the same time, it must be stressed that sterilisation is essentially a means of buying time since, in the ultimate analysis, only durable and consistent policies enhance a country’s capacity to absorb capital flows (RBI, 2003c).

6.112 In recent years, the declining stock of the Government of India securities with the Reserve Bank has brought into a sharp focus the limitations on the Reserve Bank’s ability to sterilise capital flows in the future. An internal Working Group on Instruments of Sterilisation constituted by the Reserve Bank reviewed the various instruments used in India and in other countries and deliberated on the suitability of various instruments to the current conditions in India and possibility for deployment in the future. The Group felt that the appropriate mix of the instruments would depend on the prevailing circumstances, the associated costs and benefits, and the opportunity cost of not using sterilisation as a policy option (Box VI.9).

6.113 In the context of sterilisation operations, it is also important to examine whether capital inflows

reflect higher money demand by residents. In other words, it is debatable whether it is the reduction in net domestic assets that caused subsequent capital inflows or whether the reduction in NDA offset the previous capital inflows. For instance, contraction of NDA through open market sales to sterilise initial capital flows could place upward pressure on interest rates attracting, in turn, further capital inflows. The size of inflows depends on the degree of substitutability between domestic and foreign assets. If the assets are perfect substitutes, even a small rise in domestic interest rates would attract large capital inflows rendering monetary policy sterilisation operations ineffective (Kouri and Porter, 1974; Schadler et al., 1993). A key issue, therefore, is the ability of the monetary authority to sterilise the capital inflows and yet retain control over money supply so

Box VI.9

Recommendations of the Report of the Working Group on Instruments of Sterilisation

Against the background of international experience with various instruments of sterilisation and application of available instruments with the Reserve Bank within the existing financial and legal structure, the Group felt that there was a need for a two-pronged approach: (i) strengthening and refining the existing instruments; and (ii) exploring new instruments appropriate in the Indian context. The Group examined the option of sterilisation of inflows by using/refining the existing instrument without changing the legal framework. These instruments included: (i) Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF); (ii) Open Market Operations (OMO); (iii) Balances of the Government of India with the Reserve Bank; (iv) Forex Swaps; and, (v) Cash Reserve Requirements. The Group also considered the introduction of cer tain new instruments which would involve amendments to the RBI Act: (i) Interest Bearing Deposits by Commercial Banks; and (ii) Issuance of Central Bank Securities. Moreover, the Group explored the possibility whether the Government could issue Market Stabilisation Bills / Bonds for sterilisation purposes if the existing instruments are found to be inadequate to meet the size of operations in future. The major recommendations of the Group for use of various instruments were as follows:

Existing instruments not requiring amendment to the Reserve Bank of India Act

• It is not desirable to use the LAF as an instrument of sterilisation on an enduring basis; however, for limited periods, it can be used in a flexible manner along with other instruments.

• Open market operations of outright sales of government securities should continue to be an instrument of sterilisation to the extent that securities with the Reserve Bank can be utilised for the purpose.

However, as the OMO sales entail the permanent absorption of the liquidity and transfer market risk to participants, the alternative of using the existing stock of securities for longer-term repos (up to 3 to 6 months) as an option can also be considered.

• Surplus balances of the government may be maintained with the Reserve Bank without any payment of interest so as to release securities for OMO. This would entail a review of the 1997 agreement between the Government of India and the Reserve Bank.

• Use of CRR as an instrument of sterilisation, under extreme conditions of excess liquidity and when other options are exhausted, should not be ruled out altogether by a prudent monetary authority ready to meet all eventualities.

New instruments requiring amendment to the Reserve Bank of India Act

• The RBI Act may be amended to provide for flexibility in determination/remuneration of CRR balances so that interest can be paid on deposit balances actually maintained by scheduled banks with the Reserve Bank.

• In the context of current fiscal situation and considerations of market fragmentation, it is not desirable to pursue the option of issuance of central bank paper.

New instrument not requiring amendment to the Reserve Bank of India Act

• The Government may issue Market Stabilisation Bills/ Bonds (MSBs) for mopping up liquidity from the system. The amounts so raised should be credited to a fund created in the Public Account and the Fund should be maintained and operated by the Reserve Bank in consultation with the Government.

as to pursue its stated objectives. Following Kouri and Porter (op cit), this can be examined empirically by analysing the behaviour of the central bank’s NDA and its net foreign assets (NFA). In specific terms, the direction of causality between NDA and NFA needs to be established. For most countries, both lines of causality could be operational depending upon the degree of capital account liberalisation and sensitivity of foreign flows to interest rate differentials. The 'offset' coefficient – the response of net foreign assets to net domestic assets –measures the degree to which capital inflows offset the effect of a change in NDA on money supply. An offset coefficient close to unity would imply that the efforts of the monetary authority to tighten monetary policy would induce equal and offsetting foreign inflows leaving no scope for independent monetary policy. In contrast, an offset coefficient of zero would provide the monetary authority with complete control over money supply and, therefore, discretion in the conduct of monetary policy.

6.114 Using quarterly data for the period 1976-1991 for a sample of six countries, Schadler et al (1993) found that the offset coefficient ranged ranging between (-) 0.1 and (-) 0.5 for Colombia, Egypt, Mexico and Spain indicating sufficient scope for an independent monetary policy. The offset coefficient was found to be less than (-) 0.5 for Indonesia, Korea and Spain (Lee, 1996). For Thailand, the offset coefficient was close to unity suggesting little scope of pursuing an independent monetar y policy (Schadler, et al, 1993; Lee 1996). On the other hand, the offset coefficient for Thailand was only (-) 0.33 during 1984-95, once the simultaneity bias between NDA and capital flows is taken into account, indicating some scope for sterilisation and an independent monetary policy. Moreover, consistent with the hypothesis of increasing capital mobility in the 1990s and the consequent declining monetary

policy independence, the magnitude of the offset coefficient increased from (-) 0.21 (1984-89) to (-) 0.33 (1990-95) for Indonesia and from (-) 0.21 (1984-87) to (-) 0.41 (1988-95) for Thailand.

6.115 For India, the offset coefficient was estimated to be (-) 0.3 over the period April 1993 to March 1997, suggesting that sterilisation operations conducted during this period enabled sufficient independence for monetary policy to pursue domestic goals (Pattanaik, 1997). In the subsequent period, net foreign assets have increased rapidly. Over the sample period April 1994 to September 2003, Granger causality tests indicate a uni-directional causality from changes in NFA to net domestic assets (NDA).12 Thus, over the sample period, capital inflows were not induced by domestic monetary conditions. The extent of sterilisation can be examined by estimating the central bank reaction function which studies the behaviour of central bank’s net domestic assets in response to variations in its net foreign assets. For India, the sterilisation coefficient - the response of change in NDA to that in NFA - is found to be (-) 0.92, i.e., an increase of Rs.100 in NFA induced a policy response of sterilisation that drained away NDA worth Rs.92 from the system.13 As a result, the Reserve Bank was able to offset the expansionary effect of foreign capital flows on domestic money supply, consistent with its macroeconomic objectives.

6.116 All accretions to NFA do not have a monetary impact; for instance, aid receipts, revaluation and the Reserve Bank’s income on its foreign assets contribute to NFA but have no monetary impact, obviating the need for sterilisation to that extent. As such, an appropriate measure to study the degree of sterilisation in India would be to examine the impact of the Reserve Bank’s net market purchases/ sales of foreign currency from/to authorised dealers

12 In a bivariate VAR of net foreign exchange assets (NFA) and net domestic assets (NDA) of the Reserve Bank (with both variables in first-difference) over the period April 1994 to September 2003, the null hypothesis of Granger non-causality of NDA can not be rejected (chi-square of 0.002 at p-value of 0.97). On the other hand, the null hypothesis of Granger non-causality of NFA can be rejected at 10 per cent level of significance (chi-square of 3.05 at p-value of 0.08). The VAR was estimated with one lag based on Schwarz Bayesian Information Criterion (SBIC).

13 The estimated equation, using monthly data from April 1994 to September 2003, is: DNDA = - 607 – 0.92 DNFA +158.7 DIIP{-1} + 5755 DCRRAVG.

(1.4) (13.3)*** (2.0)** (11.4)*** –R2 = 0.81 DW = 2.0

The figures in brackets are t-values; ***, ** and * denote significance at 1, 5 and 10 per cent level, respectively. DNDA, DNFA, DIIP and DCRRAVG denote monthly variations in net domestic assets, net foreign assets, index of industrial production and average CRR, respectively. In addition, monthly dummies for March, April, May, October and November turned out to be significant and were included in the estimated equation. The variable DCRRAVG was included in the regression to capture the reduction in NDA over the sample period that was due to the lowering of CRR.

(ADSALES) on the Reserve Bank credit to the Centre (RBICC), and not the entire NDA. For India, data on market sales/purchases are available effective October 1995. For instance, during 2002-03, net market purchases of foreign currency contributed Rs.75,661 crore out of a total increase of Rs.94,275 crore in NFA. As in the previous case, Granger causality tests indicate a uni-directional causality from changes in foreign exchange purchases to reduction in net Reserve Bank credit to the Centre.14 The sterilisation coefficient is 0.65, i.e., Rs.100 increase in foreign currency purchases from ADs induces sterilisation operations involving sales of Government securities wor th Rs.65 from the Reserve Bank.15

6.117 It is wor th stressing that sterilisation operations notwithstanding, there has been no hardening of domestic interest rates as is normally feared. On the contrary, interest rates have continued to soften in recent months. Sterilisation operations have so far been successful in keeping the monetary aggregates close to the desired trajectory thus enabling a softer interest rate regime.

X. CAPITAL FLOWS AND DEMOGRAPHY

6.118 As noted in the previous paragraphs, large capital flows and overall surpluses in the balance of payments in respect of several emerging market economies have posed serious problems of monetary management. The evolving patterns of demography across nations could exacerbate the challenges to monetary policy formulation over the longer term (Mohan, 2003). In general, economies pass through three stages of demographic transition - (i) high youth dependency (large proportion of population in the 0-14 years group), (ii) rise in working age population (15-59 years) relative to youth dependency and (iii) rise in elderly dependency (60+ years) relative to working age population. The second stage is regarded as the most productive from the point of view of

secular growth since it is associated with the high rates of saving and work force growth relative to the other stages. Over the next half-century, the population of the world will age faster than during the past half-century as fertility rates decline and life expectancy rises. Developed regions like Europe, North America and Japan have been leading the process of population ageing and are likely to be deep into the third stage of demographic transition. These regions will switch to importing capital. On the other hand, high performers of East Asia and China are in the second stage of the demographic cycle. East Asia could increasingly become an important supplier of global savings up to 2025; however, rapid population ageing thereafter would reinforce rather than mitigate the inexorable decline of global saving. Increasingly it would be the moderate and the low performers among the developing countries which would emerge as exporters of international capital. India is entering the second stage of demographic transition and over the next half-century, a significant increase in both saving rates and share of working age population is expected. The regional pattern of global population ageing is expected to bring about changes in the behaviour of global saving and investment balances which would be reflected in the magnitude and direction of international capital flows with implications for the conduct of monetary policy.

XI. CAPITAL FLOWS AND GROWTH: THE INDIAN EXPERIENCE

6.119 Access to international capital enables a country to supplement domestic savings and smoothen inter-temporal consumption. This could strengthen the growth process and foster employment generation in the recipient country. The actual impact of capital flows on economic growth is undoubtedly an empirical issue and varies widely across countries. An increase in capital flows is expected to augment domestic savings/investment, boost aggregate demand and lead to an increase in aggregate output/

14 In a bivariate VAR of net monthly sales/purchases of foreign exchange from ADs (ADPURC) and monthly variations in net Reserve Bank credit to Centre (DRBICCG) over the period October 1995 to September 2003, the null hypothesis of Granger non-causality of DRBICCG can not be rejected (chi-square of 0.03 at p-value of 0.87). On the other hand, the null hypothesis of Granger non-causality of ADPURC can be easily rejected (chi-square of 5.90 at p-value of 0.02). The VAR was estimated with one lag based on Schwarz Bayesian Information Criterion (SBIC).

15 The estimated equation, using monthly data over October 1995 to September 2003, is: DRBICCG = 1066 – 0.65 ADPURC - 200.1 DIIP{-1} + 5555 DCRRAVG.

(1.5) (5.2)*** (1.7)* (6.4)*** –R2 = 0.55 DW = 2.46

The figures in brackets are t-values; *, ** and *** denote significance at 10, 5 and 1 per cent level, respectively. DRBICCG, ADPURC, DIIP and DCRRAVG are defined as before. In addition, monthly dummies for March, April, May, October and November turned out to be significant and were included in the estimated equation.

income. At the same time, capital flows induced appreciation of the exchange rate could adversely affect expor ts and increase imports thereby dampening the impact on aggregate demand and lead to a deterioration in the current account. The policy response to the loss of external competitiveness may entail a softer interest rate environment to prevent appreciation of the exchange rate and to strengthen growth prospects.

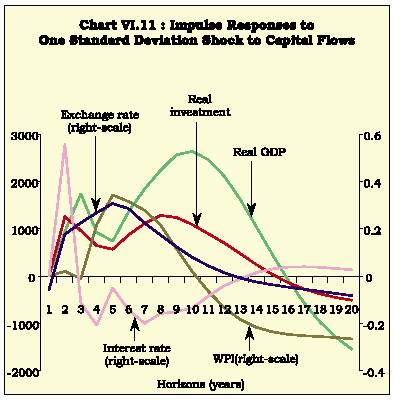

6.120 In order to gauge the impact of capital flows on macro aggregates, an unrestricted vector autoregression (VAR) model was formulated based on annual data for the period 1951-2002 in respect of gross domestic product (GDP), gross domestic capital formation (GDCF), wholesale price index (WPI), interest rate, capital flows and exchange rate. The appropriate lag length of the model was found to be 2 years.16 The results were in line with a priori expectations (Chart VI.11). A positive shock to capital flows resulted in higher investment and higher output in the medium to long-run. Prices did not increase immediately in the short-run, although a positive effect could be discernible over the medium-run. The exchange rate appreciated while the interest rate declined.

XII. CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

6.121 Net capital flows to developing countries increased sharply during 1990-96 but declined in the

later part of the 1990s in the aftermath of the East Asian crisis. The composition of flows in respect of emerging market economies also altered significantly, with private flows exceeding official flows by the end of the 1980s. Furthermore, while bank lending was the major component of capital flows to emerging markets in the 1970s, equity and bond investors became dominant from early 1990s. Although portfolio flows became important, it was FDI which accounted for the bulk of private capital flows to emerging market economies - witnessing a six-fold jump between 1990 and 1997. Most FDI flows, however, are concentrated in handful of emerging market economies. Cross-country studies have identified a large regional bias in portfolio investment flows, particularly in Latin America and Asia.

6.122 Notwithstanding their potentially favourable impact on growth prospects, highly volatile nature of capital flows, especially portfolio flows and short-term debt, underscores the need for efficient management of these flows. While managing capital flows, clear distinction should be made between debt and non-debt creating flows, private and official flows and short-term and long-term capital flows. An overbearing objective of external sector policies of developing countries has been to devise strategies so as to maximise the benefits of capital inflows while limiting their adverse impact. At an individual country level, an appropriate response would be to build a resilient and robust financial sector which could appropriately intermediate large capital flows. It is imperative that such capital flows are absorbed smoothly in real sector embodying growth impulses. Adoption of proper macroeconomic policies, particularly in respect of exchange rate management and monetary stance also assumes significance in dealing with large capital flows. The volatility and the possibility of reversals associated with capital flows were brought out quite strikingly by the East Asian and the subsequent financial crises.

6.123 Until the 1980s, India’s development strategy was focused on self-reliance and import-substitution. There was a general disinclination towards foreign investment. As a result, the magnitude of capital flows was not large to India as compared to other East Asian countries. Since the initiation of the reform process in the early 1990s, India’s policy stance has changed substantially. India has encouraged stable capital flows from the viewpoint of macroeconomic stability. The importance of official flows is declining. A cautious

approach has been pursued for management of capital account liberalisation. India’s approach to managing capital flows during the 1990s, as reflected in a revealed preference for non-debt creating flows and long-term debt flows while de-emphasising short-term flows, has been successful in its objective of attracting stable flows. All the key indicators of external debt sustainability have, in fact, significantly improved during the 1990s. In the recent period, significant relaxations have been allowed for capital outflows.

6.124 The experience with capital flows suggests that these flows are highly beneficial if they are absorbed. However, if the current account deficits are too large and unsustainable then the reversal of capital flows could cause major problems. The speed of reversals of capital flows could be quite high. The large and volatile capital flows combined with sharp rise in current account deficits played a significant role in exacerbating the vulnerabilities leading to the Asian crisis. Moreover, capital movements have rendered exchange rates significantly more volatile than before, which could lead to macro management problems. The large movements in capital flows cause sharp movements in exchange rate which are not in alignment with macroeconomic fundamentals. In this context, the next chapter on 'Foreign Exchange Reserves, Exchange Rate and External Debt Management' dwells on these issues in detail.

6.125 In the context of managing large capital inflows, the key issue that emerges is the efficacy

and extent of sterilised foreign exchange market intervention. It is evident that sterilisation operations are undertaken as part of a package encompassing exchange rate policy, level of reserves, interest rate policy, along with considerations relating to domestic liquidity, financial market conditions, and the degree of openness of the economy. India’s approach to sterilisation has ensured monetary stability without any adverse impact on interest rates.

6.126 Empirical exercises in the Indian context indicate that (i) growth in world income has a favorable impact on the capital flows, underscoring the significance of 'push' factors; (ii) outflows of foreign direct investments increase with the increase in the level of openness of the economy; (iii) a strong unidirectional causal relationship running from FDI to export growth exists; (iv) FII investments in India are positively related to risk on Nasdaq; (v) interest rate differential between India and abroad is an important factor determining inflows under non-resident deposits; and, (vi) capital flows have a favorable impact on the growth prospects of the Indian economy. It is also expected, that given the favorable demographic structure, saving rates in India would increase over the next half of this century. The key challenge for macroeconomic policies would be to ensure that the anticipated expansion in saving is productively utilised within the economy and not exported abroad. Accordingly, it is vital to ensure that the investment rate rises in close co-movement with the saving rate.

పేజీ చివరిగా అప్డేట్ చేయబడిన తేదీ: