IST,

IST,

A Study of Corporate Bond Market in India: Theoretical and Policy Implications

By Issued for Discussion DRG Studies Series Development Research Group (DRG) has been constituted in Reserve Bank of India in its Department of Economic and Policy Research. Its objective is to undertake quick and effective policy-oriented research backed by strong analytical and empirical basis, on subjects of current interest. The DRG studies are the outcome of collaborative efforts between experts from outside Reserve Bank of India and the pool of research talent within the Bank. These studies are released for wider circulation with a view to generating constructive discussion among the professional economists and policy makers. Responsibility for the views expressed and for the accuracy of statements contained in the contributions rests with the author(s). There is no objection to the material published herein being reproduced, provided an acknowledgement for the source is made. DRG Studies are published in RBI web site only and no printed copies will be made available. Director We wish to thank Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for sponsoring this Study on the Corporate Bond Market in India: Theoretical and Policy Implications as part of the Development Research Group (DRG) Studies. We want to extend our thanks to Shri B. M. Misra, Officer-in-charge, Department of Economic and Policy Research (DEPR) and other officials at RBI who provided valuable support and guidance throughout the process of this Study. We are grateful especially to an anonymous referee and others who commented and provided feedback on the draft proposal, work-in progress and final seminar of this Study. I personally wanted to acknowledge Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University for supporting me with a grant of sabbatical leave to work on the Study. Finally, I wanted to thank all my graduate student assistants who helped me in the project. In particular, I would like to thank Daniel, Kruthika, Lionel, Harish, Luis and Giby who were involved in the project at one time or the other. We are, however, responsible for the all the errors that still remain. Dr. Sunder Raghavan 1. A well-developed capital market consists of equity and bond market. A deep and liquid bond market with a significant role of the corporate bond market segment is considered to be important for an efficient capital market. A vibrant corporate bond market ensures that funds flow towards productive investments and market forces exert competitive pressures on lending to the private sector. While India boasts of a world-class equity market, its bond market is still relatively underdeveloped and is dominated by the Government bond market. The share of outstanding Government bonds in India was 39.5 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as of 2010 and compares favorably with other Asian countries such as China (27.6 per cent) and South Korea (47.2 per cent). The share of corporate bond outstanding in India, however, was only 1.6 per cent of GDP in 2010 compared to Malaysia (27 per cent) and South Korea (37.8 per cent) in the comparable period. 2. In this Study, we trace the reforms which have been put in place in the last decade and consequent developments of the corporate bond market in India. It is observed that though there is scope for further improvements in certain areas, such as reforming the stamp duty, substantial developments have taken place in the corporate bond market in India owing to measures taken by Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Government of India (GoI) in order to implement the recommendations of various committees on corporate bond market. A study of the impact of the reform process on the corporate bond market shows that resources mobilised from the primary and secondary corporate bond markets have continued to increase over the years. The corporate bonds outstanding amount has increased from $ 3.8 billion in 2005 to $ 25 billion in 2010 (0.5 per cent of GDP in 2005 to 1.6 per cent of GDP in 2010). Secondary market trades grew from ` 959 billion in 2007-2008 to ` 7,386 billion in 2012-13. The increase in the corporate bonds' outstanding amount, and as percentage share of GDP, indicated the gradual impact of the reform process in India. 3. One of the objectives of this Study is to analyse the experience of other emerging and developing economies (EDEs) at similar stage of development to capture lessons in relation to the development of Indian corporate bond market. In this milieu, we looked at the development of bond markets in Japan, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Brazil. The Japanese experience suggested that bond market development should be planned and implemented on a long-term basis with a reasonable sequence and should go hand in hand with economic development and banking reforms. The Korean experience showed that Government policy reforms and development of a vibrant Government bond market was crucial for the development of the corporate bond market. Korean experiment and consequent failure with the Bond Guarantee scheme on the other hand had important implications for the development of the Indian corporate bond market. The development of the mutual fund industry in mobilising and channeling funds to the corporate bond market in Brazil and the growth of pension funds in supporting the bond market in Chile also had interesting implications for the development of the corporate bond market in India. The issue of Sukuk bonds in Malaysia indicated that India could find innovative ways to improve the retail investor market. Finally, there were important lessons to be learnt from the reforms put in place in Singapore to improve the foreign investment in local currency bonds. 4. Bond guarantees have not been successful in other countries such as Korea in developing the corporate bond market. The Reserve Bank in its circular (RBI/2008-09/79 DBOD.No.Dir.BC.18/13.03.00/2008-09 dated July 1, 2008) specifically discouraged banks from guaranteeing bonds or debt instruments of any kind as it could have significant systemic implications and impede the development of an efficient corporate bond market. Bond guarantees in the long run could distort the risk return trade-off and would hinder the bond market from developing and acting as an effective alternate channel for raising resources. Further, the South Korean experience suggested that a financial crisis could trigger a collapse of the guarantee system. 5. The retail investors’ presence in the corporate bond market in India, however, is still shallow despite the reforms put in place by SEBI to reduce the size of trading lots and the recent increase in foreign investor limits for the corporate bond market. India might explore innovative ways, such as the issue of Sukuk bonds in the case of Malaysia, to attract retail investors. Recently, European Governments and banks are increasingly turning to their citizens and customers by issuing patriotic bonds such as the “National Solidarity Bonds”. It is worth exploring such innovative ways to expand investors' base in the corporate bond market in India. Another method to broaden the investor base is through advancement of the fund management industry by strengthening mutual fund offerings. In India, though the mutual fund industry accounts for a major share of lending in the CBLO and market repo segments, there is scope for further improvement in the retail investors’ segment. Improvements in the retail investment sector of the mutual fund industry can help in enhancing the liquidity in the corporate bond markets. Investor base can be further strengthened by encouraging foreign investment in local currency bonds. The GoI has closely monitored the developments in corporate bond market, revised the cap on foreign investment and the lock-in period from time to time to develop this market segment. Recently, the GoI reviewed and revised these limits and the lock-in period for investments. Previously, the lock in period of 3-year was perceived as a major hindrance in corporate bond market development in India. . 6. India, like many other developing countries, suffers from “original sin” phenomenon as foreign investors are reluctant to invest in local currency bonds of developing countries due to the uncertainty and risk. Though foreign currency bonds can be issued under Infrastructure Debt Fund (IDF), the problem of original sin remains. In order to increase foreign investor participation, India can follow the success of Singapore by easing regulations relating to disclosure requirements and give tax incentives to encourage foreign investments in local currency bonds. The recent liberalisation in FII investment in long term corporate debt in the infrastructure sector by the GoI is a positive development and will help alleviate the original sin problem. 7. The introduction of Credit Default Swaps (CDS) by the Reserve Bank and credit enhancements by the National Housing Bank (NHB) for Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) by primary lending institutions viz. Housing Finance Companies (HFC) and banks are steps in the right direction. Another way Indian Corporate Bond Market can be improved is through the development of credit enhancements such as securitisations and through collateralised bond obligations (CBO) or collateralised loan obligations (CLO). However, recent Sub-prime crisis has brought to fore some of the problems with CBO/CLO. After implementing due safeguards against such problems, introduction of CBO/CLO could lead to further developments of corporate bond market. Moreover, this requires independent credit analysis and credit ratings and better disclosure standards. Though there are rating agencies in India with sound credit assessment capability and good track records, further efforts to create more credit rating agencies with due expertise will improve the credibility of ratings. 8. The Indian Government initiated reform measures to develop the corporate bond market and introduced prudent regulation and supervision. The Government of India in January 2007 clarified the regulatory jurisdiction of different agencies, which facilitated for the smooth development of the corporate bond market by avoiding conflicts arising from involvement of multiple organisations in the regulation. Such a clear demarcation would ensure market participants’ understand the role of the Government as a supervisor and not as a market guarantor. 9. According to the pecking order theory, profitable firms tend to finance through internal sources first and then external sources. Amongst external sources, companies tend to finance with debt or issue of corporate bonds first and then equity. Analysis of trends in the sources of funds based on company finances studies of RBI on non-Government non-financial public limited companies for the period 1990-1991 to 2010 -2011 show that companies in India tend not to follow the pecking order theory and have instead depended more on external sources rather than on internal sources. Amongst the external sources, bank loans seem to dominate the borrowings for these companies. For example, for the 5-year period 2006-2010, 67.4 per cent of the total borrowings were financed through bank loans and only 7.0 per cent were financed through debentures. The share further increased to 71.1 per cent (bank loans) and 10.7 per cent (debentures) in 2010-11. This shows that bank loans continue to be the major borrowing source for companies. One of the reasons for the bank finance being preferred by corporations is due to the prevalence of the cash credit system in the banks in which the cash management of the corporations is actually done by the banks. This indicates that the corporate bond market still has a long way to go before becoming a viable source for companies to finance their investments. 10. Literature suggests that corporate bond market yields would be more efficient than bank lending rates in reflecting the risk return trade off. For example, in a recent Reserve Bank working paper Mohanty et.al. (2012) study on why the Benchmark Prime Lending Rate (BPLR) in India fell short of the Reserve Bank's objective of providing transparency to the lending rates. Competition forced the banks to price loans out of alignment with the original intent of the BPLR to provide transparency. Further, Mohanty et.al. (2012), noted that there was a public perception that the BPLR system had led to cross-subsidisation in terms of underpricing of credit for corporates and over pricing of loans to agriculture and small and medium enterprises. 11. There is very little analytical work on the corporate bond market in India due to lack of reliable data on a longitudinal basis. Researchers, however, have worked with the data limitation to reach interesting conclusions. We briefly surveyed available literature on the corporate bond market in India. Our analysis indicates that while the growth of the Government bond market has had positive influence on the development of the corporate bond market in India as in the case of other countries such as South Korea, the financing of Government deficit spending as reflected in the domestic credit extended by the banking sector has exerted a negative effect on its development. Other factors such as the size of the economy, openness, size of the stock market and institutional factors like corruption have had little or no impact on the development of the corporate bond market. 12. We conclude by noting that the reform process in the corporate bond market has been encouraging but the implementation of reforms has proceeded slowly. Companies continue to finance their investments via private placement and bank loans rather than through public issues and corporate bonds despite policies implemented to encourage retail and institutional participation, streamline the issuance process and create new and missing markets. The objective of this study is twofold. First, it traces the development of the corporate bond market in India and second, it attempts to seek policy inputs based on the experience of other emerging markets in developing their corporate bond market. A simple regression analysis is carried out based on data available from Reserve Bank of India, National Stock Exchange (NSE), Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). While the principal focus of the study is the corporate bond market developments in India, we also take into account the developments of the Government bond market and equity market in India in relation to the corporate bond market. A well-developed capital market consists of equity and bond market. A sound bond market with a significant role played by the corporate bond market segment is considered to be important for an efficient capital market. The corporate bond market ensures that funds flow towards productive investments and market forces exert competitive pressures on lending to the private sector. While India boasts of a world-class equity market, its bond market is still underdeveloped as compared to other Asian countries (e.g. South Korea). The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 brought to the forefront the limitations of even a well-managed, regulated and supervised banking system in countries like Hong Kong and South Korea. The crisis clearly showed that banking systems cannot be the sole source of long-term investment in an economy. In this context, Jiang, Tang and Law (2002) point out that one of the principal benefits of a well-developed corporate bond market is to provide an effective alternative source of financing to bank financing. Further, they list the following important advantages of bond financing over bank financing.

Luengnaruemitchai and Ong (2005) in their IMF working paper opine that core aspects such as benchmarking, corporate governance and disclosure, credit risk pricing, the availability of reliable trading systems, and development of hedging instruments are fundamental for improving the breadth and depth of corporate debt market. Further, the authors note that the demand and supply of corporate bonds are dependent on factors such as the investor base - both domestic and foreign, and Government policies toward the issuance process and associated costs as well as the tax regime. Torre, Gozzi and Schmulker (2006) argue that there are two major approaches to develop capital markets, in general, in emerging markets. The first one explains that the gap between expectations and observed outcomes is due to the combination of impatience with imperfect and incomplete reform efforts. This view argues that past reforms are mostly right, reforms needed in the future are essentially known, and that reforms have long gestation periods before producing visible results. The second approach emphasizes on the right sequencing. This view claims that the gap is due to faulty reform sequencing where some reforms are implemented ahead of others, and argues establishing preconditions before fully liberalising domestic financial market and allowing free international capital mobility. Torre, et al. (2006), however, argue a case for a third approach, which notes that in the case of some developing countries, one needs to “revisit basic issues and reshape expectations.” The authors contend that it is difficult to pinpoint which factors may explain the relative underdevelopment of domestic capital market in emerging markets such as Latin America. The study notes that intrinsic characteristics (such as small size, lack of risk diversification opportunities, presence of weak currencies, and prevalence of systemic risk) of developing countries limit the scope for developing deep domestic capital market in a context of international financial integration and that these limitations are difficult to overcome by the reform process. In other words, even if emerging economies carry out all the necessary reforms, they might not be able to develop their capital market to the extent of industrialised countries. It seems, therefore, that the path emerging countries like India should follow is not unanimous. As a general rule, a gradual and complementary approach is beneficial, although in some cases, a given sequencing may be preferable. While countries like Australia have followed the sequencing approach by developing their debt markets before developing their bond market, others such as Latin American countries have developed their markets in conjunction with other markets. In India, various committees viz. the High Level Expert Committee on corporate bonds (Patil Committee) and the Committee for Financial Sector Reforms (CFSR), have recommended the sequencing approach, which entails developing a number of missing markets as well as complementary development of other sectors in the economy for a healthy development of the corporate bond market. In the next two chapters, we evaluate the success of such an approach, based on the available information. This study is organised as follows. This introductory chapter is followed by Chapter 2 with a description of the development of bond market in other countries in the region as well as countries in similar stages of development as compared with India. Chapter 3 outlines the major developments and reforms that have been put in place in the Indian corporate bond market and Chapter 4 traces the effect of the implementation of the reforms by analysing data available from the corporate bond market. Chapter 5 provides a macro economic analysis to discern the crucial factors in the development of the corporate bond market in India. Finally, Chapter 6 summarises the findings and policy implications. Chapter 2: Lessons from Corporate Bond Market in Other Countries It is widely acknowledged that a well-functioning corporate bond market is important for an efficient capital market. The recent financial crisis, however, has made many countries wary of opening up their market too quickly and be exposed to the contagion spread of the crisis from other developed bond market. It is, therefore, crucial for a country to learn from the experiences of other countries in developing its corporate bond market. Studying similar emerging economies is a beneficial way for India to benchmark the development of its corporate bond market and the lessons learnt from these economies help avoid known pitfalls. In this context, we look at the experiences of Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Brazil in developing their corporate bond market. These countries have similarities as well as differences in the factors that have influenced or inhibited the development of their corporate bond market. We study Japan, Korea, Singapore and Malaysia in the sense that they are part of the Asian continent and are, therefore, affected by similar developments. Brazil, like India, is part of the BRIC countries and is expected to witness rapid growth in output in the future. There are, however, significant differences in these economies in terms of their relative size and stages of development. Policies that may work well for a small country, such as Singapore and Malaysia, may not work well for a larger economy like India. Despite these differences, their policy experience could help India in implementing appropriate measures for corporate debt market. This chapter looks at a brief history of corporate developments in Japan, South Korea, Brazil, Singapore and Malaysia and the issues these countries had to deal with in the process of development of their corporate bond market. We then draw some lessons from their experiences for India. 2.1 Corporate Bond Market Development in Japan We trace a brief history of the corporate bond market development in Japan and then go on to draw some lessons for India from their experiences. 2.1.1 History of development in the Japanese Corporate Bond Market Heavily regulated until 1985, Japan’s corporate bond market was under developed and dominated by banks. However, in the second half of the 1980s, there were important measures which helped the development of the primary market for corporate bonds. These measures included simplification of issuance procedures, deregulation of private placement, incorporation of 3 credit rating agencies, issuance of dual currency bonds and reduction of underwriting fees and trust fees. Further, these measures were followed by the removal of corporate bond financing ceiling during 1990-93. The rationalisation of the primary market for corporate bonds led to a drastic decline in the influence of banks in corporate bond issuance - from 40 per cent in 1985 to zero by the end of 1989. Further, the development of the JASDAQ over the counter programme helped to increase investor interest in corporate bond trading. The development of the corporate bond market was also boosted by the introduction of Futures and Options market during the second half of the 1980s. The introduction of Futures and Options market helped to put in place a full-fledged price discovery mechanism, issue price commitment for corporate bond issues and auction mechanism, which facilitated the development of an efficient primary market. According to Endo (2002), the development of the debt market in Japan was helped by the high savings and balance of payment surplus, existence and growth of institutional investors and integration with international market. The value and the share of outstanding bonds in Japan were $900.88 billion and 16.5 per cent of GDP, respectively, at the end of 2010. 2.1.2 Lessons from the Japanese experience According to Endo (2002), developing countries like India should draw the following lessons from the Japanese experience.

Endo (2002), therefore, suggested that bond market development should:

2.2 Corporate Bond Market Development in South Korea The Korean bond market is one of the most robust bond markets in Asia in terms of size and growth. We trace the history of the bond market development in Korea with particular emphasis on their experience with the development of the bond guarantee scheme and its subsequent failure. The Korean experience and experiment with the bond guarantee scheme and how it has evolved after the crisis has important implications for India. We would like to draw lessons from the failure of the bond guarantee system in Korea while underline other positive factors such as the development of credit rating system, credit enhancements and asset backed securities in its endeavor to develop its corporate bond market. 2.2.1 History of Corporate Bond Market Development in Korea The South Korean corporate bond market has been a vital component of South Korea’s rapid economic advancement. From Table 1 we can see that as of December 2010, the size of the Korean corporate bond market stood at US$ 380.62 billion (37.8 per cent of GDP). Until the late 1960s, both the public and private sectors in South Korea depended heavily on overseas as well as local banks rather than financing through bonds. To encourage the growth of the corporate sector, the Government aggressively intervened in bank credit allocation practices through interest rate controls and direct bank ownership. As a result, banks became the dominant players in the debt market. The Korean Government realised the benefits of developing a robust corporate bond market early and put in place policies to increase the demand for corporate bonds by building an investor base and encouraging investors to buy bonds through credit enhancements. In order to build an investor base, the Capital Market Promotion Act was enacted in 1968 to promote equity and bond market. The Securities and Investment Trust Business Act (SITBA) 1969 introduced the contractual investment trust as a vehicle to mobilise domestic capital. The SITBA also authorised the Korean Investment Corporation (KIC) to engage in the investment trust. In 1974, the KIC’s investment trust function was transferred to the newly established Korea Investment Trust Company (KITC). Thereafter, many other Investment Trust Management companies were established and the size of the contractual-type fund assets under Investment Trust Companies’ (ITC) management grew rapidly from 240 billion won in 1978 to 3.6 trillion won in 1983. Fund assets continued to grow as the number of investors interested in trust products continued to increase. Pension funds and insurance companies played a significant role as institutional investors in the corporate bond market. In 1983, commercial banks introduced an investment called the bank trust accounts. Trust accounts became popular as they offered higher returns than deposit accounts while enjoyed similar guarantees as deposit accounts. The rise of bank trust accounts contributed to the growth of the corporate bond market because trust account portfolios included sizable investments in corporate bonds, commercial paper and central bank notes. 2.2.2 Experiment with Bond Guarantee Scheme In order to build investor confidence and an investor base, the Korean Government developed a bond guarantee scheme. Under this scheme the Korean Investment Corporation (KIC) was selected as the sole guarantor of bonds in 1972. Korea Guarantee Insurance Company was allowed to start guaranteeing bonds to cope with increasing demands for bond guarantees in 1978. In 1989, the Government established the Hankook Fidelity and Surety Company to increase financial support for individuals and small businesses. The Government bond guarantee scheme included the explicit guarantees of financial institutions such as banks and securities firms. By the 1980s, banks were the major guarantors accounting for more than 50 per cent of all guaranteed bonds. Banks and other Non-Bank Financial Intermediaries entered the corporate bond guarantee business because the business was considered to be low-risk and high return given the robust economic growth in the 1980s. The financial crisis during 1997 and the resultant economic crisis resulted in the increase in bankruptcies which, in turn, resulted in increased risks to bond guarantors. Most guarantors left the market after 1997. As private sector bond guarantors came to better understand the risk involved in guaranteeing bonds, they realised that guarantee fees were inadequate reward for the risks they were undertaking. Some tried to offer bond guarantees at much higher fees which were not acceptable to bond issuers. This resulted in the collapse of the guaranteed market in South Korea after 1997. 2.2.3 Corporate Bond Market Development after 1997 Financial Crisis Though the 1997 crisis led to the collapse of the bond guarantee schemes, it also created opportunities for the development of the corporate bond market. Financial institutions in the midst of restructuring after 1997 were reluctant to extend loans to the corporate sector or to provide credit guarantees. Therefore, business sector, in need for more funds, turned to the corporate bond market. The Korean Government stepped in to support corporate borrowing by raising the commercial code ceiling on firms’ corporate issuances from twice their net assets to four times net assets. Further, the Government eliminated any foreign investment restrictions in domestic bonds. Market factors were also favourable as the interest rates declined sharply after 1998. These developments enabled the corporate sector to raise funds by issuing non-guaranteed bonds. As a result, the value of outstanding bonds grew from $68.15 billion in 1997 to $162.06 billion in 1998. The fall in interest rates led to a surge of funds to Investment Trust Companies (ITCs) which guaranteed higher returns to the investors on its beneficiary certificates. The ITCs in turn purchased corporate bonds with their increased inflow of cash. The temporary bond market boom and growth of the ITCs after the financial crisis of the 1997 reinforced the public’s perception of ITC as crisis-proof entities. In 1999, however, the bankruptcy of the Daewoo business group eroded investor confidence in the corporate bond market. Investors began withdrawing funds from the ITCs. The Government took several steps to alleviate the liquidity problems in the bond market. First, the Government introduced the Bond Market Stabilisation fund to stabilise bond yields. Banks and Insurance companies contributed to the fund. Second, the Government created incentives to invest in ITC products and launched new products with tax breaks. Third, the Government promoted investor confidence in ITCs through the execution of structural reforms including re-capitalising ITCs with public funds and permitting the write-off of ITC’s non-performing assets. The timely measures by the Government of Korea averted the crisis but it left one wondering about the moral hazard problems created by the high risk lending practices of the ITCs and the resulting bailout by the Government. Korean Guarantee Insurance Company and Hankook Fidelity and Surety Company were left to control the market after the departure of many guarantors after the 1997 crisis. These two companies competed to guarantee bonds issued by the big business groups (Chaebols) in order to survive. By 1998, however, both these companies were forced into insolvency resulting in Government prohibition of new issuances guarantees by these two companies. Korea Guarantee Insurance Company and Hankook Fidelity and Surety companies merged in November 1998. Problems, however, continued to plague the merged company and the Government had to step in to help the company when its bonds matured in 2001. 2.2.4 Improvement in Credit Ratings The post-1997 shift towards non-guaranteed corporate bonds placed a growing importance on credit rating agencies. Newly created financial products such as ABS, hybrid securities and equity-linked notes also increased the demand for credit rating agencies. Furthermore, with the introduction of mark-to-market system, credit rating assumed increasing importance as an element of pricing. Domestic credit agencies established joint ventures with prominent international agencies such as Moody’s and Fitch IBCA. 2.2.5 Emergence of Asset Backed Securities In 1998, the Government of South Korea enacted the Asset Securitisation Act, which was designed to facilitate corporate finance restructuring after the financial crisis. In 1999, the Mortgage Securitisation Act was enacted based on the reasoning that Mortgage-Backed securities were more long-term and homogenous than other asset securitisation. With the introduction of these two Acts, the Government provided tax incentives, such as exemption of acquisition tax, registration tax and withholding tax in order to promote the ABS and MBS markets. Investor confidence in the added layer of security of extra credit enhancement for ABS and MBS helped the market to develop. 2.2.6 Lessons from Bond Market Developments in Korea Some of the important lessons for India from corporate bond market developments in Korea can be summarised as follows: 2.2.6.1 Synchronised Development of Infrastructure and Investor Base The Korean Bond market development tells us that it is important to develop the bond market infrastructure and investor base concurrently in order to achieve a balanced and a viable bond market. As the Korean experience shows, preferential development of an investor base without the necessary market infrastructure can result in a dysfunctional market. For example, in the case of Korea, the Government bond guarantees created an artificial safety net which prevented the growth of a reliable credit rating system. To keep pace with its need for infrastructure development, India should also expand its investor base, but as the Korean experience shows, bond guarantees may not be the optimal method of enhancing the investor base. Steps towards improving the transparency, reliability, accessibility, timeliness and market diversification would help develop the bond market. India should broaden the investor base by increasing the number and size of financial institutions that can invest in corporate bonds. However, in the course of expanding institutional investors, the Government must not become the implicit guarantor of these institutions as was the case with Korea. Korean experiment and consequent failure with its Bond Guarantee scheme has important implications for the development of the Indian corporate bond market. RBI in its circular (RBI/2008-09/79 DBOD.No.Dir.BC.18/13.03.00/2008-09 dated July 1, 2008) specifically discouraged banks from guaranteeing bonds or debt instruments of any kind as it rightly felt that it would have significant systemic implications and impede the development of an efficient corporate bond market. A view that the Indian Government should allow banks to guarantee corporate bonds has been aired by many at times. However, such a move has to be implemented carefully. Though bank guarantees may initially help to build investor confidence and draw investors to the market, in the long run, it is likely to distort the risk return trade-off and to hinder the bond market from developing and to act as an effective “spare tyre”. Furthermore, a financial crisis can trigger a collapse of the guarantee system as happened in the case of the South Korea during the East Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. If bond guarantees are not the solution, how can India broaden its investor base? One way to broaden the investor base is through advancement of the fund management industry. This can help domestic financial industries through globalizing their market activities. The other important method to broaden the investor base is to encourage foreign investors to invest in domestic currency bonds. The real problem, however, has been that foreign investors have been reluctant to invest in developing countries. According to Eichengreen et al. (2004), emerging markets suffer from “Original Sin”. According to their theory, foreign investors are reluctant to purchase local currency bonds and developing countries are forced to issue global bonds denominated in foreign currency with relatively short maturity and subject to the legal framework of an overseas financial center. The problems of “original sin”, therefore, have prevented an increase in foreign investment in India. Eventually, as the size of the local bond market develops and transparency improves this problem is likely to disappear. 2.2.6.2 Development of Credit Enhancements Considering the negative consequences of guaranteed bonds, one alternative is to focus on the issue of non-guaranteed bonds. The question then is how can one encourage investors’ participation if bond guarantees do not work? One solution could be to try credit enhancements such as securitisations and partial guarantees through collateralised bond obligations (CBO) or collateralised loan obligations (CLO). This, however, requires independent credit analysis, credit ratings and better disclosure standards. Indian credit rating agencies have been developing. The process could be helped along by creation of more agencies with due expertise to help improve the credibility of ratings. The introduction of Credit Default Swaps (CDS) by Reserve Bank of India and credit enhancement to Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) by the National Housing Bank (NHB), are welcome steps. The launch of CDS should help in the development of corporate bond market, as it provides a hedging opportunity for both residents as well as FIIs. The introduction of RMBS would promote the development of secondary market for RMBS in India. The RMBS policy of NHB envisages the introduction of specialised institutional measures for providing credit enhancements to promote the development of secondary market for residential mortgages. It may be mentioned that the presence of specialised forms of credit enhancements issued by institutions in developed nations, such as guarantees by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae for the RMBS in USA, have considerably contributed to the success of RMBS. Care should be taken, however, not to repeat the mistakes that contributed to the financial crisis in these countries. Credit enhancement for RMBS is, therefore, expected to reduce credit enhancement costs, improving viability of RMBS transactions and encouraging the HFCs and Banks to take up securitisation of their home loan portfolios. 2.2.6.3 Government Deregulation and Supervision The Government should focus on deregulation and should substitute direct Government intervention with prudent regulation and supervision. The Government of India in January 2007 clarified the regulatory jurisdiction of different agencies which facilitated for the smooth development of the corporate bond market by avoiding conflicts arising from involvement of multiple organisations in the regulation of the market. Accordingly, it was decided that SEBI would be responsible for primary market (public issues as well as private placement by listed companies) as well as secondary market (OTC and Exchange traded) for corporate debt while RBI would be responsible for the market for corporate repos and reverse repos. However, if repos or reverse repos are traded on exchanges, trading and settlement procedures would be overseen by SEBI. It is, however, worth emphasising that while the different agencies and the Government of India have an essential role in the corporate bond market development, the role should be preferably as a supervisor and not as a market guarantor. Park (2008) outlines the following lessons one can draw from the Korean experience for other Asian economies like India.

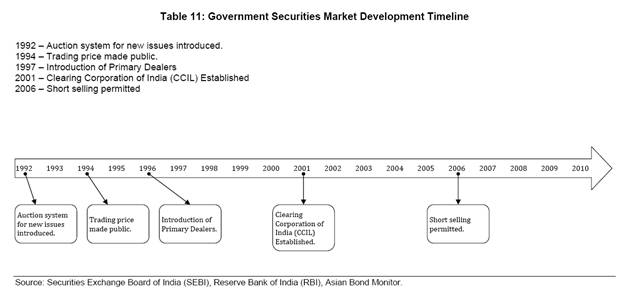

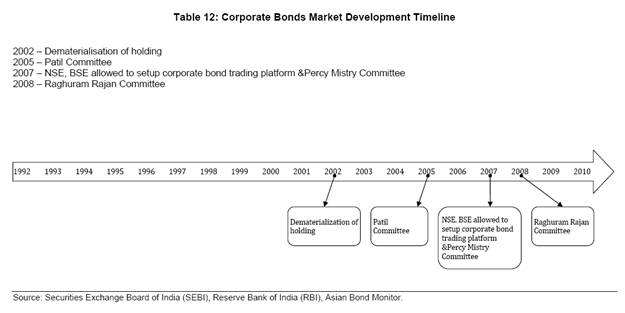

2.3 Corporate Bond Market Development in Brazil Despite the intense reform efforts in the last decade, capital market in the Latin American region seemed to have lagged behind, not only relative to developed countries, but also compared to emerging economies in other regions, such as East Asia (World Bank, 2004a). From Table 1, we can see that value of outstanding corporate bonds in Brazil and Chile were only $10.743 billion (0.5 per cent of GDP) and $29.709 billion (14.6 per cent of GDP), respectively as compared with $64.334 billion (27 per cent of GDP) in Malaysia and $380.619 billion (37.8 per cent of GDP) in South Korea at the end of 2010. Analysing the experience of Latin American countries may provide significant lessons for the capital market reform agenda going forward for emerging economies such as India. We look at the capital market development in one of the largest Latin American countries, namely Brazil. 2.3.1 History of Corporate Bond Market Development in Brazil The shape of the current financial system in Brazil can be traced to 1976 with the establishment of Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) which transferred the responsibilities to oversee the stock and corporate bond market from the central bank to the CVM. In the 1980s, steps were taken to further strengthen the financial system. These steps involved the separation of the Central Bank from Banco do Brasil and the creation of the National Treasury Secretariat. Futures and options trading were introduced in 1979 and derivative trading commenced in the 1980s. In the 1990s, high inflation rates led to the introduction of Real Plan for economic stabilisation. In 1995, there were several bank insolvencies. The Central Bank intervened to merge failing banks with stronger ones to avoid further failures. A law allowing ABS to be more easily traded was introduced in 2000. Despite these developments, the Brazilian corporate bond market (Table 1) appeared to be small relative to markets in Asia such as Korea and Malaysia but there were still important lessons for India. A thriving mutual fund industry in Brazil has been an important tool in mobilising household savings and channeling it to the capital market. In 2003, the domestic mutual fund industry gathered more than $150 billion in assets under management (30 per cent of GDP) which suggested that the mutual funds played an important role in developing and bringing stability to local corporate bond market in Brazil. Torre, et.al (2006) argued that there were important lessons to be drawn from the experience of Latin American countries for other developing countries such as India. It showed that policy initiatives needed to take into account the intrinsic characteristics of developing countries (such as small size, lack of risk diversification opportunities, presence of weak currencies, and prevalence of systemic risk) and also how these features limit the scope for developing deep domestic capital market in a context of international financial integration. Further, they felt that these limitations were difficult to overcome by the reform process. In other words, even if emerging economies carried out all the necessary reforms, they might not have obtained a domestic capital market development comparable to that of other countries. Despite this, the implementation of pension reforms in Chile and other Latin American countries showed that pension funds played a key role in developing the depth and stability of the local bond market. 2.4 Corporate Bond Market Developments in Singapore and Malaysia Felman et al. (2011), addressed how certain ASEAN countries addressed the problem of inadequate growth in their corporate bond market. Their experience might have important policy implications for India. Felman et al. (2011) pointed out that Malaysia’s market has been supported with efforts to promote the issuance of Islamic bonds, while Singapore had tried to overcome its narrow domestic issuer base by encouraging foreign firms to issue in the local currency market. 2.4.1 Malaysia’s Islamic Bond Market Malaysia found a novel way to address the problems with the growth of corporate bond market. Over the past decade, Malaysia developed a burgeoning market in Sukuk or Shari’ah- complaint bonds. Unlike conventional bonds with fixed coupon payments, Sukuk are structured as participation certificates that provide investors with a share of asset returns, making them compatible with the Islamic prohibition of interest payments. As a result, they have been increasingly popular both domestically as well as investors from Islamic nations. The issue of Sukuk bonds was backed by other policy initiatives by the Malaysian Government such as the creation of a ten-year capital Market Master Plan for developing the bond market, both Sukuk and conventional. Tax exemptions have been granted for banks until 2016 on income earned from international banking and Takaful (Islamic insurance) operations in foreign currencies. Sukuk accounted for more than half the private securities outstanding in 2004. From Table 1, we can note that between 2005 and 2010, the value of outstanding bonds in absolute terms in Malaysia has steadily increased from $27 billion in 2005 to $64 billion in 2010 (19.6 per cent of GDP in 2005 to 27 per cent of GDP in 2010). What lesson can India learn from the experience of Malaysia? The Malaysian experience shows that it is important to find innovative ways of drawing investors into the corporate bond market. Corporate bond issue should address the concern of Indians for safety of their investments while assuring an adequate return. One way to address this concern is to structure the bond so that investors feel that they are contributing to the infrastructure development of the country. Companies, for example, can issue Swadeshi bonds which will appeal to the patriotic feeling of contributing to India’s infrastructure development by investing in the corporate sector. This will help channel savings, which are currently invested in post office savings accounts or similar safe investments, into corporate bonds. Further, as in the case of the recent experience in Europe, these Swadeshi or patriotic bonds can be issued at a lower interest cost to citizens than to risk-averse institutional investors. 2.4.2 Singapore’s Offshore-Based Issuers Singapore has developed an active corporate bond market by encouraging foreign based firms to issue locally, thereby, compensating for the narrow domestic issuer base. Domestic issuance of Singapore dollar based bonds exceeded $16 billion in 2009 of which one-quarter was attributable to offshore-based companies. This is a significant achievement as the real problem has been that foreign investors have been reluctant to invest abroad. A number of factors in Singapore have encouraged issuance by offshore companies. Legal and regulatory impediments are virtually non-existent. Disclosure documents are quite simple as most are marketed to wholesale buyers. Further, issues undertaken locally have no local tax filing requirements other than to file a tax return to the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore after the issue date. Singapore corporate bond market, therefore, has been much more cost competitive compared to alternatives such as U.S. Regulation S or 144A issues. Regulatory measures adopted in 2009 have helped as well. For example AAA rated Singapore dollar debt securities issued by sovereigns, supranational and sovereign-backed corporate would be accepted as collateral under the MAS standing facility. Further, banks would be allowed to treat these securities as regulatory liquid assets, applying the same haircut as Singapore Government securities. Following the implementation of the framework, Singapore dollar debt market saw a surge in supranational issuances in 2009 totaling S$1.4 billion. Finally, foreign issuers are also attracted to Singapore because it is an international financial centre. The important implication for India is to recognise the importance of foreign investor participation to address its narrow investor base. India has been taking steps in this direction. The Government of India increased the current limit of foreign institutional investment in corporate bonds from $15 billion to US $40 billion. However, increasing the limit of foreign investment alone will not be sufficient to ensure flow of foreign investment into the country. In fact, GoI has been monitoring FIIs subscription under the scheme and as on 31st August 2011, against a ceiling limit of $25 billion, or `1,12,095 crore, investments by FIIs under this scheme were only $109 million or `500 crore. It was concluded that the three-year lock-in period and doubts regarding the interpretation of the requirement of residual maturity of five years were discouraging FIIs from investing in this scheme. The GoI has since reduced the lock-in period to 1 year for investments up to $5 billion. India, however, needs to do more to solve the “original sin” problem by creating conducive policies like simple disclosure and tax filing requirements. Chapter 3: Development of Corporate Bond Market in India Having looked at how countries in the similar stage of their development have dealt with the problem of developing their corporate bond market, we now turn to chapter 3 where we survey the theoretical literature and developments of the corporate bond market in India and challenges ahead. In India, the Government bond market has experienced a steady growth over the years due to the need to finance the fiscal deficit. The Government bond market, which is around 39.5 per cent of GDP in end-2010 (Table 2) in India compares favourably to most other Asian countries. The corporate bond market on the other hand is just 1.6 per cent of GDP in end-2010 (Table 1) and small in relation to the economy’s size. Table 1 shows, however, that from 2008 to 2010 corporate bond market in India in value terms grew from $7.85 billion to $24.99 billion. In comparison to other countries such as South Korea ($380.62 billion) and China ($ 522.09 billion), the Indian corporate bond market appears to be under-developed. The under development of the corporate bond market in India is not incidental and is mainly attributable to the structure of the Indian financial system and regulatory structure. We briefly survey the theoretical literature on corporate bond market in India and trace some of the recent developments in the capital market, Government bond market and corporate bond market in India. 3.1 Brief Survey of Theoretical Literature on Corporate Bond Market in India Ever since the celebrated Modigliani-Miller (1958) theorem, corporate finance literature has trained its inquiry on the link between firms’ financing and investment decisions. In a world without taxes, the value of the firm is independent of its debt-equity mix and depends only on the cash flows it generates. This is the now famous Modigliani-Miller Theorem. However, in the presence of taxes, the firms can benefit from the tax-debt shield and stands to gain from leverage. Therefore, capital structure is not irrelevant in the real world and corporate financing pattern becomes not only an outcome of the financial decision of the firms, but also a policy issue, with the fiscal, monetary, regulatory and institutional policies affecting the financing pattern. It has been recognised that the Modigliani-Miller theorem holds when capital market is perfect. However, financial markets are characterised by frictions and imperfections. Information flows are not symmetric. Principal-agent problems affect corporate governance and corporate decision-making. Myers and Majluf (1984) point out that high quality firms can reduce the cost of information asymmetries by resorting to external financing only if they did not have sufficient internal funds. If external financing is necessary, the same argument implies that firms should issue debt before considering external equity. Firms in developed countries therefore tend to follow what is known, following Myers and Majluf (1984), as the “pecking order” pattern of finance. This refers to firms in advanced economies usually relying on internal finance as far as possible. If their investment need cannot be internally financed, they finance through bank loans or issue long-term debt and only as a last resort tap the equity markets. This is because issue of debt, as opposed to equity, signals to the market that managers would be more disciplined and would invest in positive net present value projects. However, results on the empirical tests of the pecking order theory in developing countries seem to be mixed. Singh (1995) finds that firms in developing countries like India generally rely less on internal finance. As far as external finance, firms in these countries tend to rely more on equity finance and relatively very little on debt. Though Singh (1995) acknowledges that recently Indian firms seem to rely more on debt than equity he dismisses his finding as an outlier. Booth and et al., (2001) point out that controls on security prices along with Government sponsored credit programmes to preferred sectors would influence the pattern of corporate financing in these countries. Thus, for example, in India, Booth et al., (2001) argue that Government imposed ceilings on interest rates would lead to greater reliance on debt financing. Debt financing, however, has often meant financing through bank loans in developing countries like India. In general, bond financing is considered more suitable for large-scale, long-term financing of fixed assets and investments, whereas bank loans are thought to be more appropriate for financing short-term investments in working capital, inventories and other current assets. The lack of a well-developed corporate bond market, therefore, implies that corporations have to rely on bank loans for their long-term financing needs as well. There is very little work on debt financing via the corporate bond market, which remains underdeveloped in countries like India for reasons mentioned above. One of the major problems with theoretical research in the area of corporate bond market in India is the lack of availability of reliable data on a longitudinal basis. Despite the data limitations, researchers have tried to study the bond market and draw some interesting conclusions. Varma and Raghunathan (2000) analyse quarterly data available from Credit Rating and Information Services of India Limited (CRISIL) for the period January 1993 to October 1998 to examine credit rating migrations in Indian corporate bond market in order to understand credit risk of corporate bonds. They analyse the probability of what the rating of a bond would be next quarter given its current rating. They believe that their results provide usable estimates of the rating migration probabilities for modeling credit risk in the Indian bond market. They caution, however, that one might need to adjust the estimates for bias in the sample period which was characterised by declining corporate credit and rising rating standards. Bose and Coondoo (2003) examined the nature of the Indian corporate bond market using monthly data from the secondary market trades from NSE and BSE during the period April 1997 to March 2001. They examine several aspects of the market such as depth and composition of the market, relationship between yield to maturity (YTM) and volatility of return as implied by price movements, nature of spread between YTM of different categories of bond, relationship between market depth and price/YTM and market pricing of risk. They observe that the Indian corporate bond is characterised by lack of depth and width. Further, the market is characterised by infrequent trading, high liquidity risk, a high degree of dispersion of price/YTM over time and a lack of relationship between bond’s credit rating (risk) and its market price/YTM. The study indicates that the then policy measures such as de-materialisation of instruments should encourage exchange based trading of debt securities. They opined that though there has been significant improvement in infrastructure in the corporate bond market, more needs to be done to improve disclosure and documentation standards for private issues. They recommend measures such as mandatory credit ratings and better disclosures to overcome problems of information asymmetry, low liquidity and consequent distortions in the corporate bond market. Gajjala (2006) attempts to identify the determinants of risk premium in the Indian corporate bond market for the period 1998 to 2002. Using regression analysis, the study finds that the factors influencing risk premium differs for institutional and non-institutional trades. While default risk, liquidity risk and bond specific variables seem to explain the variation in the risk premium on retail bond trades, these factors did not explain institutional trades. Capital market reforms in India have involved the creation of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in 1992 and the formation of the National Stock Exchange (NSE) in the mid-1990. Several measures were implemented to minimise risks in equities trading and to create a national market in stocks. These included the introduction of a clearing and settlement system, creation of a centralised counterparty for transactions, establishment of a modern depository system for stocks, and a shift from carry-forward system to the introduction of futures contracts. Trading in derivatives on the NSE started in 2000 - the Indian market is now the tenth largest globally for futures contracts on single stocks and indexes and the largest for futures on single stocks. In contrast to the development of equity market, the corporate bond market is yet to respond to policy initiates undertaken. Before the 1990s, the Government securities market in India was regulated and banks and insurance companies were required to hold Government securities with administered coupon rates. After the 1990s, several reforms were put in place (Table 8). In June 1992, the auction method for issue of Central Government securities was introduced and in August 1994, there was a voluntary agreement between the GoI and RBI to phase out automatic monetisation by limiting the issue of ad hoc treasury bills. This agreement proved crucial in the reform process. The GoI’s willingness to borrow from the market at market rates along with the decision to introduce an auction system for the sale of Government loans paved the way for developing a sovereign benchmark yield curve which is important for the development of the corporate bond market. Primary dealers were introduced in 1996 to support the auction system. Primary dealers are a class of non-banking financial institutions with a threshold limit of net worth and proven track record in the Government securities market. The primary dealers were inducted into the market to perform the dual role of underwriting primary issuance of Government securities as well as to serve as market makers in the secondary market for Government securities. In order to reduce settlement risk, the Delivery versus Payment system in Government securities was introduced. In April 2001, the clearing corporation of India was established to act as clearing agency for transactions in Government securities. In order to improve transparency, the data on negotiated dealing system was made available on the Reserve Bank website. Since 2003, retail trading of Government securities has been permitted in the stock exchanges to facilitate easier access and wider participation. In June 2003, interest rate futures were introduced to facilitate hedging of interest rate risk. In April 2004, Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) was introduced to provide real time, online large value inter-bank payments and settlements. The Negotiated Dealing System-Order Matching (NDS-OM), an anonymous order matching system, was introduced in 2005 to provide NDS members with a more efficient trading platform. In 2006, the Government Securities Act was passed by Parliament to facilitate wider participation in the Government securities market and to create provisions for the issue of Separately Traded Registered Interest and Principal Securities (STRIPS). What have been the implications of the growth of the Government securities market for the corporate bond market in India? The positive impact of the growth of the Government bond market has been the development of the sovereign benchmark yield curve for the corporate bond market. However, it is also true that the strong growth of the Government securities market, favourable tax treatment and reduced cost of capital of the equities market has made the corporate bond market unattractive to most firms and investors. Though the corporate bond market has grown over the years, the growth is mostly in the area of private placement. The strong presence of development financial institutions, state owned banks and commercial banks has led to low interest rates and easy access to capital for most firms, making public placement of bond more expensive and less attractive. Another reason for corporations to prefer bank loans is due to the prevalence of the cash credit system in the banks in which the cash management of the corporations is actually done by the banks. Companies also find it less expensive and less cumbersome to privately place debt issue than public placement. This has led to a lack of transparency and information about the corporate bond market, making the corporate bond market more risky and less attractive to most investors. Various Committees have been constituted in the recent years to study and develop the corporate bond market. In 2005, a High Level Expert Committee on Corporate Bonds and Securitisation (Patil Committee) was setup under the Chairmanship of Dr. R.H. Patil to examine the legal, regulatory, tax and market design issues in the development of corporate bond market. The committee then recommended two broad set of reforms. The first set of reforms was aimed at removing the hurdles that the debt market faces in terms of regulation of the securities market as well as tax treatment of debt securities. The second set of reforms was aimed at proactive steps to enlarge the issuer base and to develop the secondary market institutions in the corporate bond market. We can group the recommendations of the Committee as those relating to the primary market, secondary market, development of the debt market and specialised debt funds for infrastructure financing. 3.2.1 Development of Primary Market The following policies have been recommended to help develop the primary market in corporate bonds.

3.2.2 Development of Secondary Market Listed below are policy recommendations by Patil Committee to improve the secondary market in corporate bonds.

Recent committees such as the Report of the High Powered Expert Committee on Making Mumbai an International Financial Centre in 2007 (Percy Mistry Committee) and A Hundred Small Steps [Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms (CFSR)] in 2009 (Raghuram Rajan Committee) point to other barriers to the development of bond market and have made further recommendations. Both the committees pointed to the lack of activity in the corporate bond market and recommended number of “missing markets” such as the market for exchange traded interest rate and foreign exchange derivatives contracts to be created. They also recommend consolidation of the number of regulators and trading under SEBI. Recent developments in response to these recommendations include the inclusion of interest rate futures, currency futures and options trading in the exchanges. Listed below are some of the major recommendations of the Raghuram Rajan Committee related to the corporate bond market.

A recent working paper published by Wells and Schou-Zibell (2008) echoed the need for similar set of reforms in the corporate bond market in India. They list the following factors which limits the development of the corporate bond market in India.