IST,

IST,

Identifying Asset Price Bubbles in the Housing Market in India - Preliminary Evidence

Himanshu

Joshi* Section I In a recently released review of the housing market, OECD Economic Outlook No.78 (2005) offers a detailed analysis of recent house price developments in the OECD countries in the backdrop of the experience of the past 35 years and in the context of the role of fundamentals. The OECD Outlook mentions that of the 37 large upturn phases between 1970 and the mid-1990s, 24 ended in downturns in which anywhere from one-third to well over 100 per cent of the previous real term gains were wiped out. This, in turn, had negative implications for activity, particularly consumption. It also observed that the current upswing in OECD countries is more generalised than in the past with a combination of factors, such as, low interest rates coupled with development of new and innovative financial products playing an important role. In regard to fundamental determinants of housing prices, while price-to-income ratio is considered a ready measure of affordability, it is by itself not a reliable measure since the cost of carrying mortgages varies over time. An assessment of a more useful measure namely, the debt servicing ratio for the OECD countries indicates that the general increase in indebtedness has been mostly offset by the decline in borrowing rates, and with the exception of Australia, the Netherlands and New Zealand, households do not seem to devote greater share of their income to debt service than in the recent past. According to the OECD Economic Outlook another approach to evaluating housing prices is based on asset pricing which uses measures, such as, price-to-rent ratio and user cost of housing. Taking these two measures, the review reports that housing prices in the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, Australia and Norway were considered overvalued while those in France, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Italy and New Zealand were not significantly overvalued. Housing prices are also impacted by other factors such as supply conditions, demographic changes and speculative pressures. Furthermore, housing cycles can influence economic activity through wealth effects on consumption and private residential investment due to changes in the profitability and the impact on employment and demand in property related sectors. Shocks to housing prices also have implications for financial stability as financial institutions with large exposures in the housing sector could find themselves with inadequate cushions to absorb the losses leading to deterioration in overall credit delivery. In regard to policy implications, views differ on how the monetary authorities should respond to housing price developments. The choice between using regulatory/tax actions or monetary policy actions is contextual but useful so long as the measures are appropriately designed with reference to the size of the actual shock. In the United States economy, which is at present experiencing a strong cycle in the housing market, prices in certain regions have risen sharply if measured against the yardstick of affordability calculated as the ratio of housing prices to annual income reflecting a build up of the asset bubble. In fact, at present, the median price of new house in the US is almost five times the median household income. More importantly, even as housing prices have risen, the rental values have remained subdued suggesting presence of speculative forces. Thus, with the rise in house prices relative to rental rates, the house price/rental ratio in the US moved above its long run average, suggesting that house prices were indeed high relative to rents (Krainer, 2003). The strong upsurge in the housing market in the US is a source of concern, especially, for the global financial stability should the market suffer a sharp downturn. In the context of the present conditions in the global housing markets where the mortgage financing rates have fallen significantly since the last few decades, the IMF has cautioned that, just as the upswing in house prices has been an international phenomenon, so any downturn is likely to be synchronised, causing widespread effects. Section II

In a country with a vast population, the problem of providing shelter to all has

been an issue of great concern to the civil society and the governments

of various times. It has, therefore, generally been subsumed that state intervention

is necessary to meet the housing requirements of the vulnerable sections and to

create an enabling environment to achieve the providing of shelter for all on

a self-sustainable basis. Concrete governmental initiatives began in the early

1950s as a part of the First Five Year Plan (1951-56) with a focus on institution-building

and housing for weaker sections of society. In the subsequent five year plans,

government action ranged from strengthening the provision of housing for the poor

and the introduction of several schemes for housing in the rural and urban regions

of the country. During the early years of housing development in India, initiatives

were taken mostly by the government, and it is only in the recent years

that private construction activity has made significant contributions mainly in

urban or semi- urban regions in the area of housing/real estate development. It

may be mentioned that the current surge in housing demand is generally limited

to large urban metropolitan regions, although smaller towns near these centers

have also seen some good growth alongside. In the history of housing development,

the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61) saw the enactment of legislations for

orderly town and country planning including the setting up of relevant organisations

and for the preparation of master plans for important towns. In 1959 the central

government announced a scheme to offer assistance in the form of loans to state

governments for a period of 10 years for acquisition and development of land in

order to make available building sites in sufficient numbers. During this period

master plans for major cities were also prepared. The Third Plan (1961-66)

led to the coordination of various programmes to help housing for low-income groups.

The Fourth Plan (1969-74) took a pragmatic view on the need to prevent the growth

of population in large cities and decongestion and dispersal of population through

the creation of smaller townships. The Housing & Urban Development Corporation

(HUDCO) was established to fund housing and urban development programmes. A scheme

for improvement of infrastructure was also undertaken to provide basic amenities

in cities across the country. In order to reduce the pressure of urbanisation

the Fifth Plan (1974-79) yet again reiterated the policy of promoting smaller

towns in new urban centres, while emphasising on the improvement of civic amenities

in urban and metropolitan regions. The Urban Land (Ceiling & Regulation) Act

was enacted to prevent concentration of land holdings in urban areas and to make

urban land available for construction of houses for the middle- and low-income

groups. The Sixth Plan (1980-85) refocused attention on the provision of services

along with shelter, particularly for the poor. The programme of Integrated Development

of Small and Medium Towns was launched in small towns for development of roads,

pavements, minor civic works, bus-stands, markets, shopping complexes, etc.

Positive incentives were offered for setting up new industries and commercial

and professional hubs in small, medium and intermediate towns. In any case,

introduction of measures mentioned above, the easing of monetary policy stance

and the priority given to the housing sector in RBI’s credit policies and

the recent Union Budgets have all provided incentives to both financial institutions

and buyers of residential property. Concerns regarding the sustainability of increasing growth in housing and

other retail financing by financial institutions now appear to be arising given

the increasing load of household debt as reflelected by the wide gap between borrowings

and repayments as reported by the latest round of decade-wise NSSO survey. The

situation calls for caution on the dangers of building up of systemic credit risk

and the instability of the financial system as a whole. While all round development of the housing sector is a welcome objective, it is also important to take note of the pace of the cyclical growth in recognition of the risks of build up of asset price bubbles. Of the several factors that contribute to the occurrence of bubbles, high credit growth backed by low interest rates is considered equally more important. It may, therefore, be useful to have some empirical analysis devoted to the assessment of the current conditions in the housing market from the point of view of developing policy choices in regard to the housing market. The empirical research on housing market in India is scarce due to the paucity of information. With the objective of filling the void, this paper attempts a technical analysis of housing price bubbles in India - particularly aiming at separating the real from speculative price elements by focusing on the relevant monetary aggregates that have a bearing on the growth of the housing market. There are a number of factors which appear to be important for the growth of housing market consisting of income growth, mix of monetary policy, tax and regulatory incentives and procedural ease of loan disbursals, etc. The speculative factors, on the other hand, may depend on the hype built around advertising, asymmetric information and speculative or herd behavior causing prices to rise to unsustainable levels and beyond that determined by relevant factors mentioned above. Although it is difficult to identify a house price bubble which occurs due to a deviation of market price from the fundamental value of the house, a number of eclectic approaches for identification have been used. Section

III Although the housing sector of the economy has received considerable attention in the recent years given its core importance in the developmental goals of the Indian economy, its significance in sustaining financial stability has been recognised rather recently following the significant credit growth at low rates of interest in the recent past. The data in respect of aggregate credit disbursed to the housing sector and national price index for housing output is not easily available on monthly frequency at which data is used in this study for the period from April 2001 to June 2005. As a result, this study is based on data which may be considered good proxies although this might be considered as an extent of limitation. However, given the fact that housing credit has formed a dominant share of overall non-food growth in the recent years, the actual annual growth in housing credit can be expected to be highly correlated with that of growth in non food credit which can be considered a good measure of the former. In fact the choice of proxy for housing credit is also supported by the fact that for the time sample under consideration, the correlation coefficient between available annual outstanding housing credit and non food credit is quite high. The price of housing is represented by the index of housing prices for major metropolitan centres compiled and provided by a bank. Although the price index for metropolitan centres does not capture the country wide pricing conditions, the index nevertheless provides a good guide to price developments since most of the price increase in housing output in the recent years has been observed in metropolitan regions. As for interest rate on housing finance, the weighted average call money rate is taken as the proxy for interest rate on housing loans as the lack of information on higher frequency weighted lending rate on housing loans limits the use of such data. It may, however, be pointed out that among all other sector specific interest rates, the movement in the interest rates on housing loans whether fixed or floating have been by and large synchronous with the short term money market rate in the recent years, as evidenced by the reduction of interest rate on housing loans for a 20-year tenure from a high of 13-14 per cent per annum in 2000 to about 7-8 per cent in 2006 following the progressive reduction in RBI’s policy interest rate. Finally, it is also necessary to include the income variable in the system for assessing the impact on housing prices. The income variable is taken as the annual growth rate in real GDP. The experimental

design is based on deflating all nominal variables by the rate of inflation based

on wholesale price index (1993-94=100) in order to have the system defined fully

in real terms.

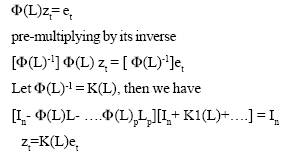

(1) where

K(L) is the vector of reduced where K(L) is of a finite order and where et

form independent white noise errors corresponding to the individual equations

in the structural VAR with a covariance matrix (2) where K(L)Ro

= R(L) and for positive definite matrix The

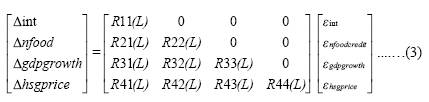

following restrictions needed for the identification of R(L) matrix are

placed on the long run multipliers to identify the structural shocks, viz.,

interest rate, nonfood credit, GDP and housing price shocks.

From the above, it is straightforward to recover Ro as both K(1) and

Section IV Table (I) presents

the forecast error variance decompositions for housing prices. According to Table

I, the majority of the explanation for the forecast error variance of housing

prices is explained by interest rate, implying that the interest rate conditions

have a significant role to play in determining housing prices. The impact

of non food credit is lesser than interest rate but taken together credit growth

and interest rate explain almost 72.3 percent of the forecast error variance of

annual change in housing prices.

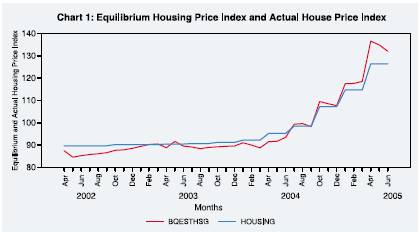

However as mentioned earlier, from the point of view of the analysis, the objective of this paper is to distinguish between the real and speculative price increases in the housing market. From expression (3), it is straight forward to estimate the fundamental or long term equilibrium housing prices given the monetary fundamentals especially, interest rate and credit growth which are taken as the explanatory variables in the model and GDP growth which captures changes in income. Chart 1 depicts the relative positioning of actual (flagged ‘HOUSING’ in the graph) and long run equilibrium housing price (flagged ‘BQESTHSG’) indices. From Chart 1 it is noted that because of the close proximity of the actual and equilibrium housing price indices, there is only a very a small extent of misalignment.

Section V The empirical findings recorded in the study support the inference that amongst the various factors that have a bearing on housing prices, monetary conditions, viz., interest rate and credit growth play a critical role. Together they explain a very large part of the forecast error variance of housing prices and can be considered as primary drivers of growth. It is, however, somewhat alarming to find that real income growth played only a minor role in determining housing prices, reflecting an extent of adverse selection in overall bank financing. Another notable factor is the low order of persistence of housing prices in India as borne out by the little explanation offered in the model by own innovations in housing prices. This finding is in contrast to the stylised feature of housing markets in other parts of the world where housing prices display strong persistence because of the time taken in clearing the market in the aftermath of a shock. Lower persistence implies that the risk of relatively quicker reversal in housing prices in the event of a shock cannot be completely ruled out. The results of forecast error variance decompositions also indicate that housing prices are significantly much more sensitive to interest rate changes than credit supply. Therefore, as advised by Bernanke (2002), there is a need to carefully evaluate the consequences of monetary policy actions especially when the housing market is seized by price bubbles, since a pre-emptive hike in interest rates (over and above what is judged necessary for overall price stability purposes), may well be counterproductive. Moreover a tighter policy to prick a housing bubble (if one could be safely identified) could also be potentially damaging for other sectors. In the recent period, as the graphical analysis

shows, the long run equilibrium housing prices are observed to closely trail the

actual level of prices implying that the extent of misalignment between the actual

and long run equilibrium housing prices has remained low during the period under

consideration. This means that the extent of speculation in the market is subdued,

and the market is primarily supported by the existing configuration of monetary

variables, viz., lower interest rates and easy availability of credit. On the future prospects of housing market, it may be considered that while the market has been working close to its potential as elicited from the convergence of the actual housing prices and long term equilibrium prices during the time sample under consideration, its performance nevertheless would continue to be tightly governed by monetary conditions defined predominantly in terms of configuration of interest rates and ease/ tightness of credit supply. References * Director, Monetary Policy Department, Reserve Bank of India. The views expressed in the paper are based on empirical findings and are strictly personal and not those of the Reserve Bank of India. The usual disclaimer applies. |

صفحے پر آخری اپ ڈیٹ: