IST,

IST,

Perspectives on the Indian Banking Sector

Several challenges will likely impinge upon the banking sector in India as it grapples with impairment in asset quality and convergence with Basel III and international accounting standards concurrently. Going forward, addressing asset quality concerns and strengthening banks’ balance sheets to reinvigorate credit growth remain key priorities, within the overall objective of promoting a competitive and efficient banking sector. I. Introduction I.1 After several false starts, global growth and trade have been gaining traction in 2017 so far, supported by accommodative monetary policy and conducive financial conditions. Despite commodity prices firming up, inflation has remained quiescent in both advanced and emerging economies. Global financial markets have been generally buoyant and the effects of geopolitical events, including announcements, have been muted or short-lived. With accommodative policies in advanced economies (AEs) supporting asset prices and spurring a search for returns, investor appetite for emerging market economies (EMEs) as an asset class has been stoked, propelling capital flows to them, albeit with some discrimination against economies with relatively weaker macro-fundamentals. Nonetheless, risks to the outlook are still tilted to the downside, with political and policy uncertainties posing threats to global financial stability. In this environment, banking regulators are preparing for the full implementation of Basel III prudential regulations and the adoption of the revised global accounting standards. In parallel, developments like FinTech and the growth of crypto currencies are presenting both opportunities and challenges. I.2 Although among the fastest growing large economies of the world, the Indian economy has been undergoing some slowdown by its own historical record during 2017-18, partly reflecting the transitory effects of the implementation of the goods and services tax (GST) from July 2017. Macroeconomic stability remains entrenched though, with inflation remaining moderate, the current account deficit contained well within sustainable limits and the fiscal deficit on the path of consolidation. I.3 Turning to the financial sector, impairment in the asset quality of the banking sector remains unconscionably high, necessitating sizeable provisioning and deleveraging, thereby constraining banks’ capacity to lend. Consequently, profitability and capital positions of banks have faced some erosion, especially in the case of public sector banks (PSBs). In the process, businesses have increasingly switched to alternate and more cost-effective sources of funds to meet their financing needs, resulting in some disintermediation for banks. I.4 During the first-half of 2017-18, however, a modest pick-up in bank credit has occurred alongside the improvement in transmission that was observed post-demonetisation. Growth in gross advances of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) improved to 6.2 per cent at end-September 2017 from 5.0 per cent at end-June 2017 due to improved credit delivery by both PSBs as well as private sector banks (PVBs). Stressed assets of SCBs have begun to stabilise albeit at an elevated level. The total stressed assets (gross non-performing assets plus restructured standard advances) as per cent of gross advances were placed at 12.6 per cent and 12.2 per cent during Q1 and Q2 of 2017-18, respectively. Among bank groups, stressed assets of PSBs hovered around 16 per cent, while stressed assets of PVBs remained below 5 per cent. The slippage ratio of SCBs recorded a decline over the first half of 2017-18. Notwithstanding the elevated level of delinquency, profitability indicators as reflected in the return on assets have been stable at around 0.4 per cent. Capital positions (i.e., capital to risk-weighted assets ratio) improved to 13.9 per cent in Q2 of 2017-18, being much above the regulatory minimum (see chapter V for details). I.5 On the other hand, balance sheets of non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) grew on the back of credit expansion mainly by loan companies, asset finance companies and investment companies. NBFCs’ consolidated balance sheet expanded by 6.5 per cent on a y-o-y basis, in the first half of 2017-18 with strong credit growth financed through higher borrowings. As against bank credit growth of 6.2 per cent during the first half of 2017-18, NBFCs’ credit growth was 14.9 per cent, about seven percentage points higher than in the previous year. This was driven by strong growth in credit to retail and services sectors. Asset quality of NBFCs (non-deposit taking systemically important), which had recorded deterioration in Q1:2017-18, witnessed some improvement in Q2, partly reflecting higher write-offs (see chapter VII for details). I.6 Against this backdrop, the rest of this chapter lays out a perspective on some issues that are likely to shape the banking ecosystem in the period ahead and inform the policy agenda. II. Emerging Issues and Policy Responses I.7 Addressing asset quality concerns and strengthening banks’ balance sheets to reinvigorate credit growth are clearly the highest priority. Improving accounting standards and nurturing competitive efficiency alongside niche competencies in the banking space are other elements of this drive. Strengthening and harmonising regulations across financial intermediaries and in adherence to global standards have been other focus areas. Concomitantly, promoting digitisation, managing technology-enabled financial innovations and dealing with cyber-security risks will entail strategic policy responses. Resolution of Stressed Assets and Strengthening of Banks’ Balance Sheets I.8 The enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016 and promulgation of the Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2017 has significantly altered the financial landscape and imbued with optimism and resolve the concerted efforts that are underway for resolution of stress in balance sheets of banks and corporations in a time-bound and effective manner. The Reserve Bank’s pre-emptive approach to recognition and resolution of incipient financial distress and the revised system of prompt corrective action (PCA) triggered in April 2017 are intended to instill confidence in the system that accumulation of excessive financial imbalances in the future will be prevented. The Government’s in-principle approval in August 2017 for the consolidation of PSBs through an ‘Alternative Mechanism’ and the massive recapitalisation plan for PSBs announced in October 2017 as part of a comprehensive strategy to address banking sector challenges should make them strong and competitive as they gear up to meet the credit needs of a growing economy (see chapter IV for details). I.9 The Reserve Bank has constituted a High-level Task Force on Public Credit Registry (PCR) (Chairman : Shri Yeshwant M. Deosthalee) for India to address information asymmetries that create opacity in credit markets, hindering efficient credit decisions, impeding effective risk-based supervision and excluding the financially disadvantaged. It will review the current availability of information on credit, the adequacy of existing information utilities and international best practices with the goal of developing a transparent, comprehensive and near real-time PCR for India. Besides improving the functioning of the credit market, the PCR is expected to foster financial inclusion, improve the ease of doing business and help control delinquencies in the banking system1. Developing Robust Accounting Standards (IFRS-converged Ind AS) I.10 International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) draw upon the lessons gleaned from the global financial crisis and attempt to close gaps in accounting practices. In India, the need for uniformity in identification of non-performing assets (NPAs) at the system level has imparted urgency to the institution of the IFRS-converged Indian accounting standards (Ind AS). Banks are required to make provisions for expected credit loss (ECL) from the time a loan is originated, rather than waiting for ‘trigger events’ to signal imminent losses. Recognising and providing for actual and potential loan losses at an early stage in the credit cycle could potentially reduce procyclicality and foster financial stability2. As overall provisions are expected to increase significantly on initial application of Ind AS effective April 1, 2018, the Reserve Bank has introduced a transitional arrangement, consistent with the Basel Committee provisions, to give banks time to build their capital. Promoting Differentiated Banking I.11 With differentiated banks such as small finance banks (SFBs) and payments banks (PBs) commencing operations in 2016-17, the Reserve Bank has started exploring the scope of setting up wholesale and long-term finance (WLTF) banks focused primarily on lending to infrastructure sector and small, medium and corporate businesses. The Discussion Paper of April 2017 envisions the role for WLTF banks to include mobilising liquidity for banks and financial institutions through securitisation, acting as market makers, providing refinance to lending institutions, and operating in capital markets as aggregators. The envisioned heterogeneous banking structure will complement and compete with universal banking institutions and enhance financial inclusion while meeting the diverse credit needs of a growing economy. Strengthening and Harmonising Banking Sector Regulation I.12 The Reserve Bank has adopted Basel III norms for implementation in a phased manner. Apart from an improved capital framework and liquidity ratios like the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and the upcoming net stable funding ratio (NSFR), the Reserve Bank has also been aligning the regulatory and supervisory frameworks for NBFCs, all India financial institutions (AIFIs) and co-operative banks with that of commercial banks with the objective of eschewing regulatory arbitrage.3 Moreover, the Ind AS standards prescribed for commercial banks, have been made mandatory for both AIFIs and NBFCs from April 2018. A formal PCA framework has been introduced for NBFCs from March 30, 2017 and a comprehensive Information Technology (IT) framework from June 8, 2017. Multiple categories of NBFCs are being rationalised into fewer categories. Along with strengthening co-operative banks through consolidation, the tiers in the co-operative structure are also being reduced. I.13 The medium-term goal is to move towards activity-based regulation rather than entity-based regulation. In this context, the evolution of regulatory practices in other jurisdictions vis-à-vis the Basel III guidelines in the post-global financial crisis period offers interesting insights that could inform the approaches being envisaged in India (Box I.1).

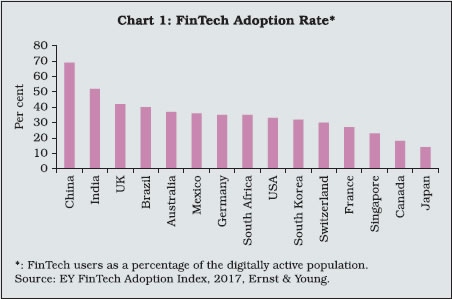

Promoting Digitisation and Managing Technology Enabled Financial Services I.14 Recent initiatives4 have opened up vast opportunities for both the incumbent financial institutions as well as for FinTech5 to introduce large scale innovations in financial services that permeate to ‘last mile’ touchpoints and boost financial inclusion. The Government’s Start-Up India programme, which aims to nurture innovations, and the India Stack platform, which offers a state-of-the-art technological framework to businesses, startups and developers aimed at presence-less, paperless and cashless service delivery, provide a conducive environment for accelerated growth of FinTech6, which would pave way for leveraging new technology in the provision of financial services. I.15 From a global perspective, FinTech innovations are bringing in alternatives to fiat currency, challenging various forms of traditional financial intermediation and even the conventional monetary system. International standard setting bodies are increasingly focusing attention on understanding the opportunities and risks associated with the FinTech revolution (Box I.2).

Bringing FinTech under the regulatory ambit should provide a level-playing field and encourage financial innovations. In this context, the Reserve Bank is working on framing an appropriate response to the regulatory challenges posed by developments in FinTech in India. Managing Cyber Security Risks I.16 The policy push towards digitisation of the financial system to realise the goal of a less-cash economy hinges crucially on the safety and security of financial transactions enabled by a robust cyber-security framework. In recognition, the Reserve Bank has been advising banks to improve their security preparedness on a continuous basis. As proposed in the Sixth Bi-monthly Monetary Policy Statement, 2016-17 on February 8, 2017, an inter-disciplinary Standing Committee has been constituted to, inter alia, review the threats inherent in the existing/emerging technology on an ongoing basis and suggest appropriate policy interventions to strengthen cyber security and resilience. III. The Way Forward I.17 In the fast changing financial landscape, banks will need to rework their business strategies, innovate on products tailored to customers’ needs, and improve efficiency in the delivery of customer-centric financial services to regain their role as principal financial intermediaries. Given India’s relatively low credit penetration7, this may even be a desirable outcome so as to enhance credit flow and revive the investment cycle. I.18 As regards stress in the banking system, banks can take advantage of the IBC to clean up their balance sheets and improve performance on a sustained basis to remain competitive. Instead of waiting for regulatory directions, banks can file for insolvency proceedings on their own8 to realise promptly the best value for their assets. In conjunction, banks need to strengthen their due diligence, credit appraisal and post-sanction loan monitoring to minimise the risks of such occurrence in future. In this regard, the setting up of a transparent and comprehensive PCR will help address information asymmetry and enhance efficiency of the credit market9. Embedded in the jump in India’s ranking in the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business Report 2018’ (to 100 from 130 in the previous year) was an improvement in the ‘ease of getting credit’ (increase in score from 65 to 75). I.19 With a comprehensive time-bound resolution mechanism in place under the IBC efforts are underway to broaden reforms. The Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill, 2017 introduced in the Lok Sabha on August 10, 2017 seeks to provide speedy and efficient resolution of distress for certain categories of financial service providers and recommends establishment of a Resolution Corporation (RC) for protection of consumers of specified service providers and of public funds. This is also expected to address the moral hazard problem associated with various forms of government guarantees. I.20 In an increasingly interconnected financial system, banks and financial institutions can benefit each other by improving corporate governance. This is more in the nature of self-regulation with safeguards to ensure that principles and rules laid down by the regulators are followed conscientiously10. I.21 Banks have been preparing to fully comply with the new IFRS-converged Indian accounting standards beginning April 1, 2018 by building adequate capital to meet the increase in provisioning requirements on account of shift to the ECL reporting system. I.22 Bank customers/borrowers are likely to demand more transparency in fees levied and interest rates charged on various financial services/products. In this context, the recommendations of the Reserve Bank’s “Internal Study Group to Review the Working of the Marginal Cost of Funds Based Lending Rate (MCLR) System” to shift from internal benchmarks like the base rate or MCLR-based loan rate setting to an external benchmark warrant consideration. The Group also recommends that the spread over the external benchmark should remain fixed all through the term of the loan, the reset period on all floating rate loans should be reduced from once in a year to once in a quarter, and banks should be encouraged to accept bulk deposits at floating rates directly linked to the external benchmark. I.23 Banks face sustained competitive pressure to increase efficiency and productivity by leveraging on technological developments and product innovations. In this regard, banking with the unbanked may probably give banks an edge over other financial intermediaries by leveraging on their branch networks. Customers at the bottom of the pyramid may hold the key to big business opportunities. FinTech developments globally are targeting hitherto excluded sections of the population and/or small businesses11. I.24 Given the potential of the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) sector in India (around 51 million units contribute 8 per cent of GDP, 45 per cent of manufacturing output, 40 per cent of exports, and employment for 120 million persons), FinTech lending companies and market-based lending could provide an alternative source of finance and fill the large funding gap faced by small businesses12, a phenomenon observed across EMEs13. The availability of large digital databases on potential borrowers, mobile density, e-commerce and usage of smart-phone based services is likely to reduce the cost of assessing creditworthiness of SMEs. Banks may also adopt financial technologies for making credit decisions and/or even enter into strategic collaborations with agile FinTech firms. 1.25 A Trade Receivables Discounting System (TReDS) has been introduced as an institutional mechanism for facilitating the financing of trade receivables of MSMEs. All the three entities that had received in-principle approval were issued final Certificates of Authorisation and have commenced operations during the year. I.26 In a digital environment, it becomes incumbent on banks to have an effective cyber-security policy as part of their overall risk management framework. Cyber-attacks entail a reputational risk for banks, as they undermine customer confidence. The Reserve Bank has been issuing guidelines from time to time to enhance cyber-security awareness and to collaborate with the industry in upgrading cyber-security resilience on an ongoing basis. I.27 To sum up, the Indian economy is undergoing structural transformation. At this juncture, reaping the full benefits of demographic, technological and financial developments appear critical for sustaining high and inclusive growth. This requires strategic coordination between conventional banks and new players like small finance banks, payments banks and also FinTech entities for providing financial services/ products in an efficient and cost-effective manner. Supportive prudential regulations aimed at promoting financial innovations without compromising safety of financial transactions, integrity of financial markets and stability of the financial system are imperative to facilitate this silent revolution. 1Acharya, Viral V. (2017), “A Case for Public Credit Registry in India”, Theme Talk delivered at the 11th Statistics Day Conference held at the Reserve Bank of India, Central Office, Mumbai on July 4. 2Patel, Urjit R. (2017), “Financial Regulation and Economic Policies for Avoiding the Next Crisis”, 32nd Annual G30 International Banking Seminar, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D.C., October 15. 3In view of the inherent risk, there is higher minimum capital requirements of 15 per cent for the newly licensed SFBs, along with subjecting them to all prudential norms and regulations as applicable to universal commercial banks. PBs are also subjected to 15 per cent minimum capital requirements along with a minimum leverage ratio of 3 per cent as against 4.5 per cent for commercial banks at present. The prescribed minimum capital requirements for NBFCs also stands at 15.0 per cent. Further, all co-operative banks are also required to achieve and maintain a minimum CRAR of 9 per cent from March 31, 2017 as part of harmonisation of capital regulations. As part of the revised regulatory framework for the AIFIs, the Reserve Bank proposes to extend various elements of Basel III standards, after due consultations with stakeholders. 4Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) for promoting financial inclusion, Aadhaar-enabled eKYC verification and linking with bank accounts to facilitate seamless financial transactions and development of robust payment infrastructure such as unified payments interface (UPI) for instant real-time digital payments. 5FinTech is defined as technology-enabled innovation in financial services that could result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on the provision of financial services (FSB, 2017). 6The PwC’s FinTech Trends Report, 2017 notes that over 95 per cent of financial services incumbents in India seek to explore FinTech partnership. 7Bank credit to non-financial corporations in India stood at around 48 per cent of GDP in Q1 2017 as against over 93 per cent for the G-20 (Bank for International Settlements (BIS)). 8Acharya, Viral V. (2017), “The Unfinished Agenda: Restoring Public Sector Bank Health in India”, Speech delivered at the 8th R. K. Talwar Memorial Lecture, September. 9Acharya, Viral V. (2017), op. cit. 10Patel, Urjit R. (2017), op. cit. 11According to PwC’s FinTech Trends Report, 2017, there are roughly 1500 FinTech startups, big and small, operating in India, and almost half were set up in the past two years. 12A Report by Deloitte “FinTech in India: Ready for Breakout” released in July 2017 estimates the credit gap in India’s MSE segment (with annual revenue up to ₹30 million) at ₹8.33 trillion. 13According to the World Bank (SME Finance Brief, September 1, 2015), the total credit gap for both formal and informal SMEs in EMEs is as high as US$ 2.6 trillion. |

صفحے پر آخری اپ ڈیٹ: