IST,

IST,

RBI WPS (DEPR): 06/2015 : Capital Structure, Ownership and Crisis: How Different Are Banks?

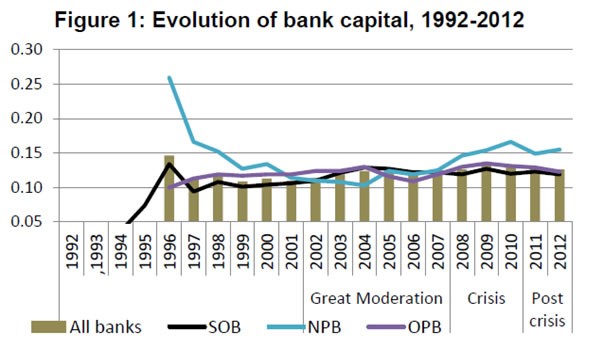

| RBI Working Paper Series No. 06 Abstract 1Employing data for 1992-2012, the article examines the factors affecting the capital structure of publicly listed Indian banks from a corporate finance perspective and compares the findings by exploiting a comparable sample of largest (based on their average market capitalization of last three years) non-financial firms. The analysis indicates that profitability, growth opportunities and risk are the factors that are most relevant in influencing bank capital. Second, the crisis appears to have exerted a perceptible impact on bank capital. On balance, the results do not support the conventional wisdom that banks’ capital structure is purely a response to the regulatory requirements. JEL classification: G 21; D74 Key words: capital structure; Indian banks; non-financial firms; book leverage; market leverage; Ownership Introduction Banks are special primarily because of the highly leveraged nature of their business. Deposits, which is the mainstay of their leverage, is generally insured at least partially but often without commensurate premia. To ameliorate possible moral hazard concerns, regulators prescribe certain minimum capital-to-asset ratio to be maintained by banks at all times. With the introduction of capital standards by the Basel Committee in the late 1980s, such norms have, by and large been adopted universally with suitable country-specific refinements to reflect more accurately banks’ portfolio risk. Thus, according to one view, regulatory standards determine the capital ratios of banks with some cushion above the prescribed minimum to minimize the likelihood of regulatory intervention or the need to raise capital at a short notice. However, empirical evidence since the 1990s bears out that banks hold capital buffer much in excess of regulatory minimum (Van Roy, 2008). This raises a question as to what other factors may affect their capital structure. Such higher capital requirements often come at a cost, though. It has been argued that higher capital requirements for banks might affect their performance. This could occur if banks’ cost of financing were to increase significantly due to more capital holding as opposed to debt. The higher funding costs could result in lower return for banks or an increase in their lending rates (Hellmann et al., 2000; Diamond and Rajan, 2000; Berger and Bouwman, 2013). Theoretically, several reasons have been put forth to justify why banks hold capital in excess of regulatory minimum (Berlin, 2011). One strand of literature contends that the Basel capital requirement is a key factor that drives banks’ capital behaviour. In the models advanced by Allen et al. (2006) and Mehran and Thakor (2011), higher capital promotes better monitoring of loans which, in turn is manifest in higher profits and/or higher market valuation. An alternate line of thinking observes that lower levels of capital might engender excessive risk taking. Anticipating this possibility, debt holders require a premium to finance banks. Consequently, market discipline from debtors compels banks to hold sufficient amount of capital (Calomiris and Kahn, 1991). It is also possible that higher capital level serves as a buffer in the event of a decline in revenues that may prompt a run on banks (Diamond and Rajan, 2000). Yet others state that, notwithstanding the manifold differences, banks may have similar incentives as those of non-financial firms and as a consequence, their capital structure may be guided by the same set of factors. Empirically therefore, it should be possible to test within an appropriate set up which of these factors are more relevant. By way of example, using data on US large bank holding companies during 1986-2001, Flannery and Rangan (2008) document a large increase in bank capital, driven primarily by counterparty (market) risk. Gropp and Heider (2010) report a negative relationship between leverage and asset risk for large publicly traded commercial banks in the US and European Union. Employing data on large banking organizations for 12 advanced economies, Brewer et al. (2008) finds that larger banks have lower capital ratios than smaller ones. Evidence on Turkish commercial banks appears to suggest that size exerts a positive effect whereas profitability exerts a negative effect on book leverage (Caglayan and Sak, 2010). We contribute to this literature by analyzing the determinants of capital structure for Indian banks covering the period 1992-2012 that encompasses the recent financial crisis. To explore whether similar results carry over to non-financial firms, we also report results with a comparable set of variables for these entities. Though we focus primarily on leverage, we address several related issues as well. First, we examine the relevance of bank ownership for leverage. Extant evidence appears to suggest that the capital position of private banks is higher as compared to SOBs. During the period 1992-2012 for instance, the equity-to-asset ratio of private banks was 8.4 as compared to 5.5 for state-owned banks (SOBs)2. Post-crisis, private banks equity-to-asset ratio has improved to 16.9 as compared to 5.6 for SOBs. The equity-to-asset ratio for foreign banks has traditionally been lower, averaging 12.4 during the 1992-2012 period. The literature has focused on several facets of ownership, including its interlinkage with bank performance (Micco et al., 2007), stability (Iannotta et al., 2007, 2013; Beck et al., 2009), efficiency (Altunbas et al., 2001; Das and Ghosh, 2006; Casu et al., 2012), productivity (Kumbhakar and Sarkar, 2003) and risk-taking (Barry et al., 2011). To what extent does ownership matter for leverage has not been adequately explored and this is one of the issues addressed in the paper. Second, we investigate the importance of the recent financial crisis in impacting bank capital. Several studies have examined the behavior of U.S. commercial banks during the crisis (Huang, 2010; Ivashina and Scharfstein, 2010; Cornett et al., 2011; Santos, 2011). In the case of India, Acharya and Kulkarni (2012) find evidence to suggest that SOBs fared better during the crisis as compared to their private counterparts. Eichengreen and Gupta (2013) provide evidence in support of a deposit reallocation away from private banks. However, the interplay between bank capital structure and crisis across ownership for Indian banks has not been addressed in prior empirical research. We also consider the impact of regulatory pressure on bank leverage. Partly as a response to the crisis and the subsequent regulatory-and policy-related issues, banks have been hard-pressed for capital. It therefore seems likely that, reeling from the crisis and its after-effects, with limited opportunities to access capital markets, banks would deleverage to meet the regulatory minimum capital levels. This problem could be manifest more markedly for public sector banks owing to the significant procedural and logistical constraints involved in raising capital at short notice. Evidence from the US (Jacques and Nigro, 1997) and elsewhere (Aggarwal et al., 1999; Rime, 2001; Ghosh et al., 2003) find evidence in support of regulatory pressure influencing bank capital decisions. Finally, we contribute to the thin literature on the interlinkage between corporate governance and capital structure for banks. More specifically, we identify several measures of corporate governance and ascertain their influence on capital structure. Contextually, Berger et al (1997) observes that firms with larger boards have low leverage. They contend that larger boards exert pressure on managers to pursue low leverage and enhance firm performance. To anticipate the results, the findings suggest that bank capital structure is not purely a response to regulatory requirements. As well, the results appear to suggest that public sector banks operate with higher leverage as compared to private banks and that, it was essentially the riskier banks that delevered during the crisis. The remainder of the analysis continues as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the relevant literature. This is followed by a brief synopsis of the institutional environment for Indian banking. The database and variables employed in the study are discussed in Section 4, followed by the empirical strategy and results (Section 5) and concluding remarks (Section 6). Although there is a large theoretical literature on what makes banks special, the issue of banks’ capital structure decisions has been a relatively under-researched topic. The fluctuating capital levels of banks over the last two decades have led researchers to explore the rationale behind the optimal capital decisions of banking firms. Three broad strands of thinking have come to dominate the literature. In what follows, we first briefly outline the theoretical framework and thereafter, highlight the relevant empirical literature. 2.1 Theoretical framework The first is commonly labeled as the regulatory view. According to this approach, although the proportion of debt and equity might differ between banks and non-financial firms, the regulatory capital requirements as stipulated in the Basel Accord and safety net in the form of deposit insurance are the two major elements that drive bank capital behavior (Berger et al., 1995). On one hand, the regulatory requirements are premised on the need to mitigate bank fragility and safeguard systemic stability and thereby limit the negative externalities caused by bank failures. On the other hand, these regulatory requirements also serve to mitigate the moral hazard incentives emanating from deposit insurance, so as to dissuade banks from becoming excessively leveraged. The second view as to why banks hold excess capital can be traced to the buffer or discretionary capital view. In this framework, it is posited that since issuing fresh equity at short notice is costly (Stein, 1988), banks hold excess capital to avoid the associated costs. These costs are both implicit and explicit. The former might stem from regulatory interference, while the latter relates to penalties and/or restrictions imposed by the supervisory authorities due to a breach of the regulatory requirements. Therefore, a capital buffer protects the bank against costly and unexpected shocks, if the costs of financial distress stemming from holding low amounts of capital are substantial and the transactions costs of raising new capital quickly are overwhelming (Berger et al., 1995). The specific amount of discretionary capital (that is, in excess of the regulatory requirements) is determined by various bank-specific characteristics (Jokipii, 2008). The third is the corporate finance view, which primarily builds on the characteristics of non-financial firms. Three main theories – trade-off theory, pecking order theory and agency theories – constitute the core of this view. While essentially focused on industrial firms, some of them have a bearing for financial firms as well. The main contention of the trade-off theories is that the decision maker (typically a manager) balances the various costs and benefits of leverage (Frank and Goyal, 2007). Most often, the theory predicts that the optimal debt ratio is determined when marginal costs of debt equals its marginal benefit. Subsequently, researchers have propounded the dynamic trade-off theory which innovates upon the static approach by observing that firms might deviate from the optimal capital structure for longer periods, since they face exponentially increasing transaction costs stemming from a continuous rebalancing of the capital structure. Empirical evidence in support of such theories is however, weak (Myers, 1984). The pecking order theory builds primarily on information asymmetries and argues that a firm follows a 'pecking order' in its choice of capital in the sense that it prefers internal to external and debt over equity, if external financing is employed (Frank and Goyal, 2007). Unlike the trade-off theory, the pecking order theory does not indicate what the optimal capital structure might be but instead, puts forth a hierarchy of financing options. Studies of the pecking order conclude that information asymmetries indeed add a cost to external equity capital in banking, when they analyze bank lending (Bolton and Freixas, 2006). A third area, i.e., agency costs, explores the impact of conflicts between stakeholders of a firm on its capital structure. The three major forms of such costs include: asset substitution, debt overhang and the free cash flow theory. The asset substitution problem occurs when the equity holders insist that the company invests in assets that are much more risky than what the bondholders might want. The riskier investment increases the return for equity holders, but also increases the risk that bondholders are compelled to take (since equity holders get the upside and the downside is absorbed by bondholders), and thereby, raises overall bankruptcy risk. Asset substitution has relevance for banks, since the opacity of banks’ balance sheets makes it easier to substitute riskless assets with risky ones, as was evidenced during the subprime crisis (Acharya et al., 2012). The debt overhang or underinvestment refers to the situation where a company is highly levered and it cannot borrow more money easily to even finance a new investment with positive Net Present Value (NPV). Equity holders will be reluctant to undertake such projects, since most of the benefits will accrue to debt holders. Hanson et al. (2013) point out that debt overhang problems prevented banks from raising the optimal amount of capital that they needed to during the crisis and as a result, had to be bailed out by national governments. The free cash-flow theory models the agency cost between managers and investors, where the former are assumed to have incentives to maximize own welfare at the expense of owners. Hence, managers will act in their own interests, seeking higher-than-market salaries, perquisites, job security and general empire building (Myers, 2001), which does not seem to be much different in the banking sector (Cihak and Hesse, 2007). Thus, increasing leverage increases the probability of financial distress, but it can also add value by imposing financial discipline on managers. 2.2 Empirical framework Several studies (Ayuso et al., 2004; Lindquist, 2004; Jokipii and Milne, 2008; Stolz and Wedow, 2011) have examined which of the aforesaid theories are pertinent for banks. The evidence indicates that profitable banks with better growth opportunities face lower costs of issuing equity and therefore, are likely to be more levered. The effect of bank size on leverage is not evident, a priori. On the one hand, larger banks face lower informational asymmetries (i.e., are better known to markets) and therefore, hold lower buffers. On the other hand, if the costs of financial distress are larger for big banks, then it is more likely that these banks will hold larger buffers (and hence, less levered). Finally, riskier banks are likely to hold higher buffers in order to limit the probability of financial distress.3 A related strand of the empirical literature explores the influence of bank capital on stock returns. Using a large sample of banks across countries, Demirguc Kunt et al. (2013) report that better capitalized banks witnessed a smaller decline in their equity value during the crisis. This literature also correlates with research that links bank capital and performance during crisis and tranquil times (Berger and Bouwman, 2013) and the impact of better governance on bank stocks during the crisis (Beltratti and Stulz, 2009). This literature however, does not analyze the factors affecting bank capital per se, which is central to the empirical inquiry of our paper. More recent research adopts a proactive approach, focusing on identifying in detail the reasons for the large capital ratios of banks. Flannery and Rangan (2008), for example, analyze the influence of market discipline on capital buffers using data from the 100 largest US banking firms during 1986-2000. The authors show that large bank holding companies raised their capital ratios after 1994, but none of them were constrained by de jure regulatory capital standards since 1995. According to their analysis, the capital increases in the latter half of the 1990s were driven by enhanced market incentives to monitor and price large banks’ default risks. Nier and Baumann (2006) also provide evidence that market discipline has a positive influence on banks’ capital buffer in their cross-national study. Of late, Gropp and Heider (2010) have analyzed the factors determining the financial structure of the US and European banks from a corporate finance perspective during 1991- 2004. The empirical evidence indicates that risk and profitability exert a negative impact on bank leverage. Furthermore, they suggest that regulatory capital requirements were of second order importance. Although our study is similar in spirit to Gropp and Heider (2010), there are also notable differences. For one, we focus on Indian banks, unlike advanced economy banks that constituted the sample in Gropp and Heider’s (2010) study. Additionally, owing to the diversity in their historical experiences, cultural norms and institutional contexts, comparability of the results in a cross-country context is often a challenging task (Rodrik, 2012). By focusing on a single country therefore, we are able to circumvent these concerns. Second, we run parallel regressions using a similar set of independent variables for non-financial firms to compare and contrast these results with banks. The idea inherent in this strategy is to provide a perspective of whether the determinants of capital structure for banks are comparable to those for (large) non-financial firms and not so much towards identifying the determinants of corporate capital structure, per se. Subsequently, we investigate the impact of the global financial crisis on bank leverage. Given the importance of regulation for banks, we employ bank-specific, time-varying measure of regulatory pressure and examine how it correlates with capital structure, an aspect not addressed in prior research. And finally, we explore the import of corporate governance characteristics for banks’ capital structure. 3. The institutional environment for Indian banking The largest country in South Asia, India has an extensive financial system, comprising both banks and non-banks. The banking system is the mainstay of the financial system with bank assets comprising a significant proportion of GDP during the post-reform period. The commercial banking segment presently has 26 SOBs in which the government has majority equity stake, 20 private sector, consisting of 7 new private banks (NPBs), which became operational after initiation economic reforms in 1991 and the remaining old private banks (OPBs), and over 40 foreign banks (FBs), which operate as branches. The share of SOBs in overall banking asset presently stands at around 75 per cent, whereas private and foreign banks constitute the remaining. On the eve of financial reforms in 1990, SOBs' comprised over 90 per cent of banking assets (Table 1). Over the period of reforms beginning 1992, (real) bank asset has expanded at a compound annual rate of 10 per cent till 2012; the growth rate of deposits and credit during the same period has been 10 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively. This growth has been uneven across bank groups: while credit and deposit growth of private banks has been of the order of 20 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively, the same for SOBs has been 10 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively. Foreign banks have registered credit and deposit growth that, in percentage terms, is broadly similar to those for SOBs, although their share in overall (on-balance sheet) banking assets has declined over time. Credit growth was impressive for private banks during the early reform years, reflecting to a large extent, the establishment of new private banks. Although their credit and deposit numbers have remained robust thereafter, it has not matched up to the pace registered earlier. The consolidation of several banks in this segment also had their effect. The trends in the evolution of capital during this period are no less compelling. During the initial years of reforms, the capital position of SOBs, measured in terms of their capital-to-risk weighted asset ratio (CRAR) was quite low, reflecting their gradual convergence with international standards and the lead time provided to these banks (primarily those with international presence) to achieve the regulatory minimum (Figure 1). By the time the second Narasimham Committee Report was published (Government of India, 1998), overall bank capital averaged nearly 12 per cent, with the number being particularly high for new private banks, coinciding to an extent, with the high capital position during the early years of their operations. For PSBs, the improved capital position during the mid- to late-1990s compared to the initial years was the result of twin factors of government capital support to these banks and their access to the capital market, beginning 1994. The CRAR of PSBs witnessed a sharp jump during the years of Great Moderation, given the high profitability which substantially augmented their capital base. This occurred despite no government capital infusion during this period, although several of these banks made follow-on public offerings. The capital position of SOBs ebbed somewhat during the crisis, but was more pronounced thereafter, reflecting to an extent their low profitability and the increased provisioning on delinquent loans. The crisis exerted a non-negligible impact on banks. Illustratively, both credit and deposit growth declined sharply and in fact, credit growth was negative for foreign banks. Although growth has since picked up, they have been lower than the pre-crisis levels. Prior to the inception of financial sector reforms in 1991, the Indian banking system was heavily regulated. The prevalence of onerous reserve requirements, interest rate controls on both the asset and liability sides and allocation of financial resources to pre-designated sectors adversely impacted both resource mobilization and its allocation. After independence in 1947, the government observed that loans extended by banks were biased towards working capital for trade and large firms (Joshi and Little, 1996). In addition, it is perceived that banks should play a key role in mobilizing financial resources for strategically important sectors. Reflecting these concerns, all private banks were nationalized in two stages, first in 1969 and subsequently in 1980. Quantitative loan targets were imposed on these banks to expand their network in rural areas and extend credit to pre-designated sectors. Although non-nationalized banks were allowed to co-exist with SOBs, their activities were tightly regulated through regulations on entry and strict branch licensing policies. During the period 1961-91, the number of banks increased slightly, but savings were successfully mobilized in part because of a rapid expansion in rural branches (Burgess and Pande, 2005). Nevertheless, banks remained unprofitable and inefficient owing to their weak lending strategy and lack of proper risk management strategies. Joshi and Little (1996) note that, the return on assets in the second half of the 1980s was around 0.15 per cent, while capital and reserves averaged less than 2 per cent of assets. The period beginning 1992 witnessed the foundations for banking sector reforms. The reforms comprised five major planks: cautious and proper sequencing, mutually reinforcing measures, complementarities between banking reforms and other associated policies (e.g., monetary, external, etc.), developing financial infrastructure and nurturing and developing financial markets (Reddy, 2000). The growing competition as a consequence of the reforms was manifest in a decline in the share of SOBs in total banking assets by roughly one percent per annum over the reform period (Table 2).

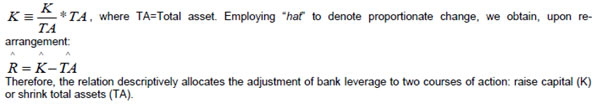

The disaggregated data on bank balance sheet and profit and loss accounts for the period 1992-2012 are culled out from the various issues of Statistical Tables Relating to Banks in India, a yearly publication by the India’s central bank. This publication provides annual audited data on the balance sheet and profit and loss accounts of individual banks. The data is perfectly comparable across banks, with the central bank acting as regulator of the financial system requires the financial entities to present their balance sheets with the same accounts and criteria. The financial year for banks runs from the first day of April of a particular year to the last day of March of the subsequent year. Accordingly, the year 1992, the first year of the sample, corresponds to the period 1992–93 (April–March) and so on, for the other years. The bank-wise prudential and financial ratios are culled out from the Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India, a yearly statutory publication by the country’s central bank. Since we are interested in not only book leverage but also market leverage (that requires the computation of market value of equity, MVE), we restrict our analysis to publicly listed banks. As a result, we extract information on closing NSE share price and outstanding number of shares for these banks from the Prowess database. In addition, we also exploit the Prowess database to acquire data on certain other relevant variables, such as the size of bank board in a given year, number of female members on the board and a measure of duality, which equals one when the CEO and the board chair are the same person (Brickley et al., 1997). Three factors need to be taken on board in this context. First, the de novo private banks became operational since 1996 and as a result, the number of reporting banks witnessed an increase thereafter. Second, banks were listed on the equity market at different time points during the sample period. As a result, the data on MVE (and consequently, market leverage) is available for a much shorter time span as compared to the book value. Third, the banking industry witnessed consolidation activity during this period. We take this into account by inserting a dummy which equals one for the acquirer bank in the year of merger. As a result, the number of reporting banks varies with a maximum of 47: with an average of 18.8 years of observations per bank, we have information on a maximum of 883 bank-years4. These banks, on average, account for over 80 per cent of banking sector assets during the sample period. Finally, the macroeconomic data are obtained from the Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, an annual central bank publication which provides time-series information on several macroeconomic variables. In parallel, we also utilize the Prowess database to identify the top 50 (based on their average market capitalization of the last three years of the sample) domestic firms across three ownership categories (group, private or state-owned) and cull out information on a similar set of variables as for banks for the period beginning 1992 through 2012. We deliberately consider the average market capitalization so as to even out sharp declines in the market value of equity (MVE) of some of the firms during this period, coinciding, to an extent, with the crisis. As well, we purposely choose not to include foreign firms in order to keep the ownership considerations similar to those for banks. Following from the literature, our main proxies for capital structure (dependent variable) are book leverage and market leverage (Gropp and Heider, 2010).5 The corporate finance literature contends that leverage is closely related to firm-level characteristics. As Harris and Raviv (1991) observe “leverage increases with fixed assets, non-debt tax shields, investment opportunities and firm size and decreases with volatility, advertising expenditure, the probability of bankruptcy, profitability and uniqueness of the product”. Following from this observation, we include a similar set of explanatory variables that are identified as standard in the literature (See also Rajan and Zingales, RZ 1995; Frank and Goyal, 2004). We include size as a proxy for behavioral differences between large and small firms; market-to-book value as a proxy for investment opportunities (high growth firms would be inclined to take less debt); fixed asset as a proxy for collateralization (more collateralized firms can take on larger debt); RoA as a proxy for profitability (profitable firms rely more on retained earnings, lowering their reliance on debt), dividend payment as a signal for firm's future earnings and finally, a modified Z-score as a proxy for firm risk, since such firms will be less inclined to take additional debt (MacKie-Mason, 1990). A similar set of variables were also employed for firms, although in several instances, the definitions are different from those employed for banks (See Table 3). We also consider additional variables. First, we include a dummy for the global financial crisis. Following Eichengreen and Gupta (2013), this equals 1 for the period 2008-10, else zero. For firms, we include industry-year effects to control for all factors that are year-specific (such as, real GDP growth, stance of monetary policy) and industry-year specific (such as changes in tax rates, changes in regulation, etc.). To moderate the influence of outliers, we winsorize all variables at 1 per cent at both ends of the sample. The summary statistics are set out in Table 3. Not surprisingly, banks are much more levered, irrespective of whether book or market values are considered, as compared to non-financial firms. For instance, banks are 65 per cent more levered in book value terms; in market value terms, their average leverage is nearly two-and-a-half times as firms. Among the dependent variables, although banks are nearly twice as large as non-financial firms, their profitability and growth opportunities are significantly lower, testifying to the high degree of competition in the industry. Although not strictly comparable, bank deposits constitute a much larger proportion of their liabilities. Likewise, banks appear to face high regulatory pressure, on average. In all cases, the differences between banks and firms are strongly significant at the 0.01 level.

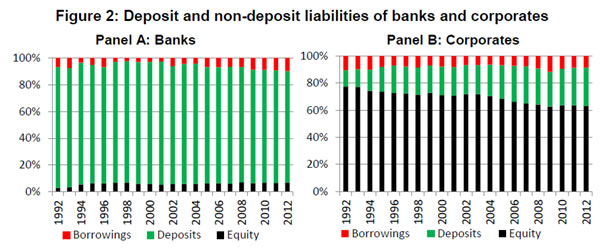

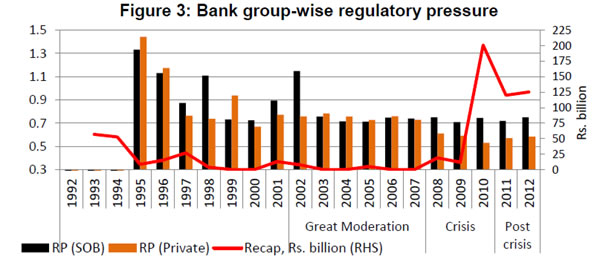

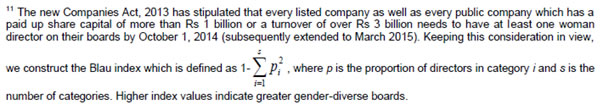

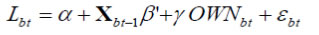

Table 4 presents the correlation matrix of the relevant variables, separately for banks (Panel A) and firms (Panel B). Both measures of leverage appear to be strongly correlated with the independent variables. For example, the correlation between size and market leverage is 21 per cent for banks and slightly lower at 19 per cent for firms; when considered in terms of book leverage, these correlations are insignificant. The lack of correlation with book leverage would appear to suggest that size does not matter for bank capital structure. These raw correlations do not control for bank characteristics or the business cycle. 5. Leverage and bank characteristics We employ a panel framework to control for these factors not accounted for in the simple correlation matrix. Accordingly, we begin our discussions by specifying the regression framework for banks. A similar framework is employed for non-financial firms as well. Consider the following specification for bank b at time t:  (1) where Lbt is the outcome variable of interest; α is the intercept, X is a vector of (lagged) bank-specific controls to take on board the potential endogeneity between the outcome and the independent variables, OWN are dummies which control for the ownership type of the bank and ε is the error term. We use fixed effects to estimate Eq. (1) and control for bank ownership.7 The rationale behind this strategy is that we are able to control for unobserved bank characteristics that might affect bank capital structure. Another point of note is that our estimates will remain robust only if the potential source of endogeneity arises from the correlation between the time-invariant component of the error term and the regressor of interest. Besides, we control for macroeconomic shocks through year fixed effects and cluster the standard errors at the bank/firm level (See, for example, Bertrand et al., 2004; Laeven and Levine, 2009). 5.1 Baseline results The results of the estimation are set out in Table 5 for banks and non-financial firms separately. For purposes of comparison, we report the estimates of Gropp and Heider (2010) for banks. Likewise, in respect of firms, we report comparable estimates of Frank and Goyal (2004). The estimates in Col.(1) suggest that leverage is lower for profitable banks. From the coefficient on RoA, it can be deduced that a one standard deviation increase in profits would lower (book) leverage by 0.7 percentage points. We include two measures of bank risk: the non-performing loan ratio (NPL to total loans) is an accounting (and relatively backward-looking) measure, whereas asset price risk is a market-related (and relatively forward-looking) measure. The coefficient of the risk variable, measured either way, is negative, but statistically significant only in the latter case. The sign of the variable is consistent with the corporate finance argument that riskier banks are less levered (i.e., have higher equity), as lenders will be interested in investing their funds only when the owners have sufficient stake in the firm. Also, because the cost of issuing equity is higher for riskier banks, they may need to hold more discretionary capital. Contextually, Calomiris and Wilson (2004) also uncovered an inverse relationship between risk and leverage for publicly traded US banks during the 1930s. The third important variable in the regression results is MTB, which represents available growth opportunities. We find banks with higher growth opportunities are less levered. One explanation could be that such banks command higher premium from the market, thus reducing the overall cost of issuing equity. Relatedly, such banks can also be on the lookout for acquisitions and therefore, need adequate equity to support such ventures. Looking at ownership, it is observed that SOBs operate with higher leverage as compared to private banks. It is possible advance two possible reasons for this fact. First, the majority ownership by the government limits their flexibility in raising capital from the market. Also, the ‘safe heaven’ perception of depositors in these banks coupled with state guarantees could mean that these banks operate with lower capital. In a related context, Acharya and Kulkarni (2012) show that SOBs were able to weather the headwinds of the crisis more effectively as compared to their private counterparts. This effect is however quantitatively small, indicating that the average state owned bank has leverage that is 0.011 per cent points higher as compared to an average old private bank. Considering that the average book leverage is 0.94, this is not a sizeable difference. Col.(2) delineates the explanatory power of the model when the independent variables are included one at a time. Without loss of generality, the evidence supports the fact that MTB and risk have the highest explanatory power. How does our results compare with Gropp and Heider (2010)? The effects of profitability and risk on leverage are very similar except that the elasticities with respect to the latter are much higher in our case. Additionally, unlike our findings, size, collateral and dividend-paying capacity were the other important determinants of banks’ book leverage in their study. We obtain quite similar results with market leverage as the dependent variable. The coefficient on Asset risk is statistically and economically much more prominent. Among others, profitability and MTB exert a negative impact on market leverage, and additionally, the elasticities in each case are higher than those obtained under book leverage. The results for non-financial firms concur with the findings of Frank and Goyal (2004), notwithstanding the definitional differences [See fn. 4]. More specifically, profitable firms are less levered as they rely on their retained earnings to build reserves (which is part of overall equity), consistent with what the pecking order hypothesis would suggest. Also, dividend paying firms with greater riskiness (i.e., financially more distressed) exhibit lower leverage. In case of the former, as argued by Frank and Goyal (2004), dividend paying capacity indicates less financial constraints and lower requirements of borrowed funds. In case of the latter, costs of borrowing are much higher and the owners may have to bring in the required funds. As well, the coefficient on MTB is positive, suggesting that high-growth firms tend to take on large amount of debt. However, unlike Frank and Goyal (2004), size and collateral do not have any impact on market leverage in our framework. The magnitudes are not only statistically significant, but economically relevant as well. To see this, note that the coefficient on MTB equals 0.011, so that a 10 per cent increase in growth opportunities lowers liabilities by roughly 0.1 per cent points. The results with respect to market leverage for non-financial firms are directionally similar. Only exception is that the coefficient on MTB is negative and significant, consistent with cross country studies. In essence, high MTB firms could be associated with more acquisitions and as a result, less likely to use debt to finance high risk projects which entail significant informational asymmetries (Baker and Wurgler, 2002; Frank and Goyal, 2009). Likewise, dividend bears a negative sign, just the opposite of what is observed under book values. To encapsulate, the findings are more akin to the corporate finance theory which suggests that banks decide on their capital structure in much the same way as non-financial firms. We next turn to an evaluation as to how bank leverage measures evolved during the crisis and whether it varied across ownership. 5.2 Crisis and ownership Having examined the baseline results, we next turn to a discussion as to whether these findings were, in any way, altered during the crisis. Table 6 highlights the results of running regressions with book and market leverage as dependent variables. We first consider only the crisis variable and thereafter, include bank characteristics interacted with crisis and ownership, respectively. Several features of Table 6 are of note, besides the fact that most of the control variables, when significant, are of similar sign as in the baseline regression. In Col.(1), the coefficient on Crisis is negative and significant, suggesting overall deleveraging during the crisis. Inclusive of the interaction terms, the results present an interesting picture (Col. 2). First, neither Asset risk nor Crisis is individually significant as earlier, although Asset risk*Crisis is negative and strongly significant. This suggests that the crisis exerted an uneven impact, and it was essentially the riskier banks that deleveraged during the crisis. For a bank with Asset risk equal to 0.036 - the average value for the sample – the extent of deleveraging during the crisis was of the order of 0.010 per cent points. Similarly, there is evidence of deleveraging by bigger banks during the crisis. In terms of market leverage, there is evidence of an increase in leverage by high MTB banks during the crisis (Cols. 3 and 4). During tranquil times, banks with higher MTB reported lower market leverage (negative sign in the regression) as they benefitted from higher market price. However, as their stock prices fell quite sharply during the crisis, it was reflected in higher market leverage (the positive coefficient on MTB*Crisis in Col.4). The reverse was the case with dividend paying banks: in normal times, these banks were more levered as they probably enjoyed relative cost advantage in raising debt through deposits and/ or borrowings. During the crisis period however, this advantage got nullified. There is no evidence of any perceptible impact on market leverage across bank ownership. In sum, the evidence indicates that the response of MTB and dividend-paying banks differed, depending on the measure of leverage considered. 5.3 Decomposition of leverage The discussion thus far highlights the relationship between bank capital structure and its proximate determinants tend to conform to the corporate finance view. As is well-known, banks funding sources comprise deposit and non-deposit liabilities, the former being the sole preserve of banks and the latter more akin to long-term debt of corporates. Although there is no exact correspondence, without loss of generality, the unsecured borrowings of corporates can be considered as akin to deposits ,whereas their secured borrowings, which have a collateral backing, as non-deposit liabilities. At book values, the correlation between deposit and non-deposit liabilities for banks is -0.94 and for corporates, it equals -0.96. Figure 2 (Panels A and B) depicts the year-wise share of deposit (unsecured borrowings) and non-deposit liabilities (secured borrowings), computed at book values, for banks and corporates, respectively. For banks, the share of equity has more than doubled over the period, from less than 3 per cent to over 7 per cent. What is important to note is that the share of non-deposit liabilities, which was around 7 per cent of total liabilities in the early half of the sample period has since increased, especially after the crisis to around 10 per cent in 2012. As compared to this, the proportion of equity in corporate capital structure has declined over the period, at the cost of a sharp rise in unsecured borrowings. Advancing this argument, we examine the results from regressing deposit and non-deposit liabilities respectively on the set of variables, as earlier. The coefficients of the explanatory variables are broadly equal and opposite in sign for deposit and non-deposit liabilities respectively, as is to be expected. To be more specific, bigger and riskier banks as well as those with high growth opportunities have higher recourse to non-deposit liabilities (Table 7). In fact, a 10 per cent increase in risk lowers banks’ ability to secure deposits by 0.4 per cent points. Similarly, private banks rely more on non-deposit liabilities. Interestingly, banks with higher tangible assets have higher share of deposit liabilities. Greater tangibility is associated with lower informational asymmetries, so that greater transparency improves the deposit base of banks. Based on the point estimates in Col.(1), a one standard deviation increase in size would lower share of deposits (in total liabilities) by roughly 3 per cent. A pertinent question to ask is: how did the response evolve during the crisis? The estimates in Cols.(3) and (4) indicate an increase in share of deposits during the crisis. This is consistent with the universal trend towards greater reliance on 'traditional' banking by increasing recourse to deposit funding. Looking across ownership, the evidence suggests that both state-owned and new private banks increased reliance on deposits during the crisis, although given the greater dependence on non-deposit funding for the latter in the first place, the net effect still was a lower dependence on deposit funding.8 It is also borne out that profitable banks and dividend paying banks could garner more deposits during the crisis, implying that the health of the bank is an important consideration for depositors to repose their faith in them. 5.4 Leverage and regulatory pressure Next, we attempt to identify the effects of regulatory pressure (RP) on bank leverage. The RP variable is defined as the ratio of regulatory prescribed CRAR to bank-specific CRAR. The higher the ratio (implying a lower denominator for a given numerator), the greater the banks are constrained in terms of capital.9 Figure 3 depicts the evolution of regulatory pressure (RP) across bank groups during the period. As observed, regulatory pressure was higher for domestic private banks during the early half of the sample. Especially during the crisis and after, the regulatory pressure for SOBs has significantly exceeded that of domestic private banks. The RP variable for SOBs could have been much higher otherwise: recapitalization was ₹ 232 billion during the crisis, averaging 0.10 per cent of GDP. Economically, banks constrained by regulatory pressure would be inclined to raise capital in order to meet the stipulated capital levels. This needs to be weighted alongside the fact higher that, partly as a response to the crisis and the subsequent downturn, corporate balance sheets have been severely stretched, impacting their cash flows. This, in turn, has had its manifestation in weakening of banks’ balance sheets as well. To capture the possible dynamics, we employ a similar framework as earlier. Our variable of interest is regulatory pressure (RP). We also allow for possible non-linearities by including the squared of RP. The results are set out in Table 8. The coefficient on RP equals 0.054, while its squared term equals -0.008. Both these coefficients are statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. The inflection point in the relationship is 3.4.10 This convex quadratic relationship suggests that increases in regulatory pressure is initially associated with an increase in leverage (i.e., lower equity) as banks aggressively compete for market share, but once regulatory pressure exceeds a threshold, banks are compelled to increase equity (or, rebalance their asset book) to meet the regulatory standards. In contrast, there is no evidence of any perceptible impact of regulatory pressure on market leverage (Col.3). How does regulatory pressure interact with ownership? To see this, note that, in both Cols.(2) and (4), the coefficient on Private*RP is negative and statistically significant. This implies that private banks lower leverage in response to regulatory pressure. As compared to this, SOBs do not exhibit any perceptible response to regulatory pressure. Intuitively, PSBs are not unduly impacted by the constraint on their capital position, given the implicit government guarantee. 5.5 Capital structure and board structure In this section, we briefly explore the interlinkage between capital structure and board structure. As regards board structure, we employ three variables: board size (expressed as natural logarithm of number of Directors on the Board), Blau index (which indicates the gender diversity of the board) and a dummy for duality. According to Lipton and Lorsch (1992), there is a significant relationship between capital structure and board size. The empirical association among these variables can run either way. On one hand, large boards follow a policy of higher leverage to enhance firm value. It has also been argued that larger boards might find it difficult to arrive at a consensus in decision-making which can translate into lower levels of governance and consequently, higher leverage (Wen et al., 2002; Abor, 2007). As compared to this, evidence for US show that firms with larger board membership exhibit low leverage (Berger et al., 1997). According to the authors, larger board size translates into strong pressure from the corporate board to make managers pursue lower leverage. Extant research focuses primarily on non-financial firms; there is admittedly limited evidence on this score for financial firms, primarily for emerging markets. Given the increasing emphasis on board diversity, we employ the Blau index (Campbell and Minguez-Vera, 2008; Miller and Triana, 2009).The index ranges from 0 (no women in the board) to a maximum of 0.5 (equal number of women and men in the boardroom).11 Faccio et al. (2012) show that firms with greater gender diversity avoid risky investments by avoiding riskier bets which would entail lower leverage. On the contrary, Berger et al. (2012) report that having women on board need not necessarily ensure greater risk-averseness. As a consequence, the relation between Blau index and capital structure is ambiguous, a priori. Finally, we employ a measure of duality (where CEO is also the chairman of the board), as discussed earlier. Dual leadership lowers problems related to separation of ownership and control. Therefore, firms with CEO duality might have greater accessibility to external financing (Abor, 2007). The results are set out in Table 9. All regressions take on board the full set of control variables, including dummies for mergers and year fixed effects, but these are not reported for brevity. The findings highlight two important considerations. First, in case of SOBs, more diversified boards (as captured by Blau index) entail lower book leverage, although the results are reverse for private banks. In Column 3, a one standard deviation increase in the Blau index – equal to 7 percentage points - entails a decline in book leverage by 0.3 percentage points. One possible way of interpreting these findings could be as follows. With greater flexibility in decision making, the risk-taking capacity of private banks tends to be attuned to market dynamics, so that irrespective of higher women representation, the net impact is manifest in higher book leverage. This runs contrary to findings which tend to suggest that women are more risk averse than men (Coleman, 2003). As compared to this, for SOBs, greater female representation is manifest in lower risk-taking. Intuitively, SOBs could be sub-serving manifold objectives because they are often employed as vehicles to drive the government’s economic and social agenda (Shleifer and Vishny, 1994; Boycko et al., 1996). In addition, to ensure success in future elections, they could be inclined to pursue conservative investment strategies (Boubakri et al., 2012). Therefore, even with greater female board representation, SOBs might not jeopardize their position by taking excessive risks (Allen and Gale, 2000). Second, larger board size leads to lower book leverage, especially for private banks. This result is consistent with Mehran (1992) and Berger et al. (1997) who have argued that larger boards may emphasize owner-manager to employ more equity capital in order to improve firm performance, resulting in lower debt levels. 5.6 Robustness In this section, we briefly highlight some of the robustness tests. First, it can be argued that the leverage ratios could in part be driven by the higher share premium which some of the banks obtained while making an equity/follow-on offer. To explore this further, we re-run the baseline regression with a revised leverage ratio, which is computed after netting out the share premium reserves. The results (not reported for brevity) reinforce previous findings.12 Second, it is possible that these results, especially those relating to market leverage, could be driven by the share price of a few banks, which are more actively traded and therefore, might not be representative of the set of listed banks. To explore this empirically, we once again re-estimate our baseline results using a sub-sample of most actively traded banks. We choose the 12 banks which constitute the BSE Bankex.13 The results in Table 10 support previous findings that most of the variables which are statistically significant are of the same sign. This provides evidence that the results are not driven by a few banks, but are representative of the entire sample. Employing data on an extended sample of Indian banks during 1992-2012, we examine the evolution of bank capital structure and its proximate determinants. Several findings stand out in our analysis. First, some of the variables identified as standard in the corporate finance literature also appear to hold empirical validity in case of banks. Thus, profitability and high growth exert a negative impact on book leverage. These results refute the wisdom that banks capital structure is purely a response to the regulatory requirements and instead, are more akin to the corporate finance view of capital. Second, the crisis appears to have exerted a perceptible impact on bank capital. The positive effects of capital support by national governments weighed against the sharp decline in banks market value of equity arising from the slump in their share prices. The net effect was higher market leverage than otherwise for banks with high MTB. As regards the composition of bank liabilities, the evidence indicates that bigger banks with high growth opportunities have been lowering the role of deposits in their funding structure. Interestingly enough, risk is a significant factor for explaining deposits, considered in either book or market value terms, suggesting that depositors take cognizance of bank risk when placing their deposits. Contextually, it may be mentioned that Eichengreen and Gupta (2013) uncovered a 'flight to safety' for bank deposits during the crisis, away from private and towards SOBs. On balance, our analysis does not provide unequivocal support to the regulatory view of bank capital structure. Because if that were the case, the factors driving the book and market leverage of banks would have been different. Instead, the results would indicate that banks capital decisions are influenced by several non-regulatory considerations as well, including government policies towards banks. Whether and to what extent these results carry over to other emerging market and developing economies remains an area for future research. @ Deputy Adviser (Research), Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning, Reserve Bank of India, Main Building, Fort, Mumbai 400 001. Mail and Officer in Charge, Department of Statistics and Information Management, Reserve Bank of India, Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051. Mail. Useful observations by an anonymous referee and comments on an earlier draft by A K Srimany and especially by Abhiman Das and discussions with Angshuman Hait are gratefully acknowledged. 1 The views expressed and the approach pursued in the paper reflects the personal opinion of the authors. 2 We employ the terms public sector banks (PSBs) and state-owned banks (SOBs) interchangeably. 3 Note that capital (K) satisfies the following identity:  4 This includes: 17.8 years of observations for 28 SOBs (498 observations), 18.8 years of observations for 13 old private banks (245 observations) and 14 years of observations for 10 new private banks (140 observations), 5 Given the focus on banks, the definition of leverage is consistent with Gropp and Heider (2010) but the opposite of that employed by Rajan and Zingales (1995) and Frank and Goyal (2004) in their analysis of non-financial firms. 6 0.717 (Current assets -current liabilities)/Asset+ 0.847*Retained earnings/Asset+3.107*PBIT/ Asset+ 0.420*BVE/ Asset + 0.998* Sales/Asset. We prefix the number by (-1) so that higher values imply greater likelihood of distress, in order to maintain consistency with bank distress (e.g., higher NPLs imply greater distress). 7 We control for ownership as opposed to incorporating bank fixed effects, based on the consideration that the business models are roughly similar across ownership. Additionally, controlling for ownership instead of directly accounting for bank-specific effects provides greater degrees of freedom. 8 The coefficient on Private in Col. (3) equals -0.12, while Private*Crisis equals 0.08, implying a net effect of -0.04 9 Provided a bank’s actual capital adequacy ratio is, at all times, at least equal to the regulatory minimum, this would suggest that the RP variable would range from 1 (maximum regulatory pressure) to zero (no regulatory pressure). 10 The inflection point is calculated as the derivative of leverage with respect to regulatory pressure. See also, Lind and Mehlum (2010). 12 The correlation matrix between book leverage and market leverage with and without the share premium reserves is as follows:

13 These 12 banks subsume the 10 banks considered under Bank Nifty. References Abor, J. (2007). Corporate governance and financing decisions of listed Ghanaian firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review 7, 83-92. Acharya, V., H.Mehran and A.Thakor (2012). Caught between Scylla and Charybdis? Regulating bank leverage when there is rent seeking and risk shifting. CEPR Discussion Paper 8822, CEPR: UK. Aggarwal, R., and K.Jacques (1997). A simultaneous equations estimation of the impact of prompt corrective action on bank capital and risk. In Financial Services at the Crossroads: Capital Regulation in the 21st Century. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Conference Volume, pp.21-35. Allen, F., and D. Gale (2000). Financial contagion. Journal of Political Economy 108, 1-33. Allen, F., E. Carletti and R. Marquez (2011). Credit market competition and capital regulation. Review of Financial Studies 24, 983–1018. Ayuso, J., D. Pérez and J. Saurina (2004). Are capital buffers pro-cyclical? Evidence from Spanish panel data. Journal of Financial Intermediation 13, 249-264. Barth, J., G.Caprio and R.Levine (2004). Bank regulation and supervision: What works best? Journal of Financial Intermediation 13, 205-48. Beck, T., A. DemirgucKunt and O. Merrouche (2013). Islamic vs. conventional banking: Business model, efficiency and stability. Journal of Banking and Finance 37, 433-47. Berger, A N., R J Herring and G P Szego (1995). The role of capital in financial institutions. Journal of Banking and Finance 19, 393-430. Berger, A., T. Kick and K. Schaeck (2012). Executive board composition and bank risk taking. Bangor Business School Research Paper 4, Bangor University: UK. Berger, A.N. and C.H.S.Bouwman (2013). How does capital affect bank performance during financial crisis? Journal of Financial Economics 109, 146-67. Berger, P., E.Ofek and D.Yermack (1997). Managerial entrenchment and capital structure decisions. Journal of Finance 52, 1411-38. Bertrand, M., E. Duflo and S. Mullainathan (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Quarterly Journal of Economics 119, 49–275. Betratti, A., and R.Stulz (2009). Why did some banks perform better during the credit crisis? A cross-country study of the impact of governance and regulation. Fischer College of Business Working Paper 12, Ohio State University: OH. Bolton, P. and X.Freixas (2006). Corporate finance and the monetary transmission mechanism. Review of Financial Studies 19, 829-70. Boubakri, N., J-C, Cosset and W. Saffar (2013). The role of state and foreign owners in corporate risk-taking: Evidence from privatization. Journal of Financial Economics 108, 641-658. Boycko, M., A.Shleifer and R.W.Vishny (1996). A theory of privatization. The Economic Journal 106, 309-19. Brewer, E., G. Kaufman and L.Wall (2008). Bank capital ratios across countries: Why do they vary? Journal of Financial Services Research 34, 177-201. Caglayan, E., and N. Sak (2010). The determinants of capital structure: Evidence from the Turkish banks Journal of Money, Investment and Banking 15, 57-64. Calomiris, C. and Charles M. Kahn (1991). The role of demandable debt in structuring optimal banking arrangements. American Economic Review 81, 497–513. Calomiris, C. and Wilson, B. (2004) Bank capital and portfolio management: the 1930’s “capital crunch” and the scramble to shed risk.Journal of Business 77, 421-455. Chernykh, L. and R.Cole (2011). Does deposit insurance improve financial intermediation? Evidence from the Russian experiment. Journal of Banking and Finance 35, 388-402. Cihak, M., and H. Hesse (2008). Islamic banks and financial stability: An empirical analysis. IMF Working Paper 16. IMF: Washington DC. Coleman S. (2003). Women and risk: an analysis of attitudes and investment behavior. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 7, 99-114. Das, A and S. Ghosh (2006). Financial deregulation and efficiency: An empirical analysis of Indian banks during the post-reform period. Review of Financial Economics 15, 193-221. DemirgucKunt, A., E.Detragiache and O. Merrouche (2013). Bank capital: Lessons from the financial crisis. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45, 1147-64. Demirguc-Kunt, A. and H.Huizinga (2004). Market discipline and deposit insurance. Journal of Monetary Economics 51, 375-99. Diamond, D. and R.G.Rajan (2000) A theory of bank capital. Journal of Finance 55, 2431- 2465. Eichengreen, B and P. Gupta (2013). The financial crisis and Indian banks: Survival of the fittest? Journal of International Money and Finance 39, 138-52. Faccio, M., M. Maria-Teresa and M. Roberto (2012). CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2021136. Flannery, M. (1994). Debt maturity and the deadweight cost of leverage: Optimally financing banking firms. American Economic Review 84, 320-31. Flannery, M. and K.Rangan (2008). What caused the bank capital build-up of the 1990s? Review of Finance 12, 391-429. Frank, M., and V. Goyal (2004). Capital structure decisions: Which factors are reliably important? Financial Management 38, 1-37. Ghosh, S., D M Nachane, A Narain and S.Sahoo (2003). Capital requirements and bank behaviour: An empirical analysis of Indian public sector banks. Journal of International Development 15, 145-56. Government of India (1998). Report of the Committee on Banking Sector Reforms (Chairman: Shri M Narasimham). Government of India: New Delhi. Gropp, R., and F.Heider (2010). The determinants of bank capital structure. Review of Finance 14, 587-622. Hanson, S G., A.K.Kashyap and J C Stein (2011). A macroprudential approach to financial regulation. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25, 3-28. Harris, M. and A.Raviv (1991). The theory of capital structure.Journal of Finance 46, 297- 356. Hellmann, T., K.Murdock and J.E.Stiglitz (2000). Liberalization, moral hazard in banking and prudential regulation: Are capital requirements enough? American Economic Review 90, 147-65. Holmstrom, M., and J.Tirole (1997). Financial intermediation, loanable funds and the real sector. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, 663-91. Huang, R. (2010). How committed are bank lines of credit? Experiences in the subprime mortgage crisis. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Paper No. 25, Philadelphia: PA. Jacques, K. and P.Nigro (1997). Risk based capital, portfolio risk and bank capital: A simultaneous equations approach. Journal of Economics and Business 49, 533-47. Jokipii, T. and A. Milne (2008). The cyclical behaviour of European bank capital buffers. Journal of Banking and Finance 32, 1440-1451. Laeven, L. and R.Levine (2009). Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics 93, 259-75. Levi, M., K. Li and F. Zhang (2014). Director Gender and Mergers and Acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance 28, 185-200. Levine, R. (2002). Bank-based or market-based financial systems: Which is better? Journal of Financial Intermediation 11, 398-428. Lind, J.T. and H.Mehlum (2010). With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 72, 109-118. Lindquist, K.G. (2004). Banks buffer capital: How important is risk? Journal of International Money and Finance 23, 493-513. Lipton, M. and J.W.Lorsch (1992). A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. The Business Lawyer 48, 59-67. MacKie-Mason, J. K. (1990). Do taxes affect corporate financing decisions? Journal of Finance 45, 1471-1493. Mehran, H. (1992). Executive incentive plans, corporate control and capital structure. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 27, 539-60. Mehran, H. and A.V. Thakor (2011). Bank capital and value in the cross- section. Review of Financial Studies 24, 1019–67. Nier, E. and U. Baumann (2006). Market discipline, disclosure and moral hazard in banking. Journal of Financial Intermediation 15, 332-61. Rajan, R. and Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data, Journal of Finance 50, 1421-1460. Rime, B. (2001). Capital requirements and bank behavior: Empirical evidence for Switzerland. Journal of Banking and Finance 25, 789-805. Rodrik, D. (2012). Why we learn nothing from regressing economic growth on policies. Seoul Journal of Economics 18, 141-64. Santos, J.A.C. (2011). Bank corporate loan pricing following the subprime crisis. Review of Financial Studies 24, 116-43. Shleifer, A. and R. Vishny (1994). Politicians and firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics 109, 995-1025. Stein. J.C. (1998). An adverse selection model of bank asset liability management with implications for transmission of monetary policy. RAND Journal of Economics 29, 466-86. Stolz, S and M. Wedow (2011). Banks' regulatory capital buffer and the business cycle: Evidence for Germany. Journal of Financial Stability 7, 98-110. Van Roy, P. (2008). Capital requirements and bank behavior in the early 1990s: Cross country evidence. International Journal of Central Banking 4, 29-60. Wen, Y., K.Rwegasira and J.Bilderbeek (2002). Corporate governance and capital structure decisions of Chinese listed firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review 10, 75-83. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

صفحے پر آخری اپ ڈیٹ: