|

Introduction

6.1 Financial stability has received greater attention the world over in recent years as is evident from the periodic financial stability reports brought out by several central banks and international financial institutions, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and the World Bank. The greater emphasis on financial stability is due to several major trends and developments in the financial systems. Greater deregulation and liberalisation in tandem with technological developments have incentivised development of complex instruments and diversity of activities on the one hand, and enhanced mobility of risks, on the other1. Financial systems have expanded at a significantly higher pace than the real economy with rapid growth particularly in equity, debt and derivative markets. The process of financial deepening has been accompanied by changes in the composition of the financial system, with a declining share of monetary assets, thereby resulting in greater leverage of the monetary base. Financial institutions now undertake a broader range of activities than the traditional banking activities of taking deposits and extending loans. As a result of technological developments and increasing degree of cross-industry and cross-border integration, financial systems are also more integrated nationally as well as internationally. A large number of financial conglomerates have also emerged.

6.2 The changing contours of financial system have, however, expanded the sources of financial instability. The developments relating to technological innovation, diversity of financial instruments and the emergence of financial conglomerates have all increased potential severity of financial instability. Furthermore, the sources of financial disturbances have become more unpredictable mainly due to integration of financial markets across national boundaries, thereby exacerbating the possibility of contagion. Thus, the sources of financial instability could range from external factors (such as macroeconomic performance) to national/regional/international security related reasons to internal factors (such as macroeconomic performance, market volatility, counterparty risk and operational risk).

6.3 A stable financial system promotes efficient allocation of economic resources, geographically and over time. In a broader perspective, financial stability analysis focuses on a wide range of issues covering macroeconomic performance of the economy, monetary stability, regulation and supervision of banking and financial institutions and any other risk that may influence the financial system. Very often these aspects happen to be inter-related in a complex manner. Macroeconomic performance of the economy influences the ability of the firms/ individuals to abide by the contracts in financial transactions. The soundness of the financial system on the other hand is crucial for providing support to the strong macroeconomic dynamics.

6.4 For practical purposes, financial stability covers a number of interrelated components, which include infrastructure (payment and settlement system, legal framework and accounting practices), institutions (banks, securities firms and institutional investors) and markets (stock, bond, currency, money and derivatives). Financial stability does not require that all parts of the financial system operate in most efficient manner all the time. A stable financial system rather has the ability to resolve imbalances through self-corrective mechanism before they precipitate a crisis.

6.5 The need for concerted efforts for ensuring financial stability has been reinforced in recent times because of increased degree of globalisation and integration of financial markets coupled with emerging signs of volatility in these markets. Although globalisation has expanded the potential output of several economies, the ability of a developing country to derive benefits from financial globalisation in the presence of volatility in international capital flows can be significantly improved by the quality of its macroeconomic framework and institutions.

6.6 Technological developments have also raised concerns for financial stability. In the recent period, there is an increasing trend towards convergence of various financial business segments with significant parts of the convergence chain resting with the banking sector. With the rapid developments in technology and changing customer preferences, delivery channels in the banking sector have concomitantly undergone a metamorphosis in order to remain competitive. Internet-based delivery services and mobile telephony have emerged as potential channels for prompt customer services. Besides several benefits, technological developments have allowed the formation of financial conglomerates and also benefits of economies of scale. Aligning the operations of large financial conglomerates and foreign institutions with local public policy priorities remains a challenge for domestic financial regulators in many Asian emerging economies. Technological developments have also enabled banks and financial institutions to depend on outsourcing to a greater degree. Managing the outsourced entities by banks assumes greater importance. It is important in the context of financial stability to ensure adequate safeguards in the processes of outsourcing and appropriately address confidentiality of the information.

6.7 The episodes of financial instability often have adverse impact on wider sections of the community, including firms and households. The overall cost of such episodes could be enormous for an economic system, which often spills over cross borders. The East Asian crisis during the mid-1990s revealed implications of weaknesses in the financial sector on the economy in terms of severe economic and social consequences. Excessive volatility in financial markets can significantly raise the cost of capital for business investment and adversely affect expansion in output. The weak financial sector may also impede the monetary transmission mechanism when the central bank attempts to stimulate the economy.

6.8 In view of its criticality, policy makers the world over have been seriously concerned about the risks to financial stability. The prime responsibility of soundness of the financial sector in most of the countries lies with the monetary authorities because monetary stability is strongly related to financial stability. At the international level, one of key objectives of the BIS is to promote monetary and financial stability. Within the BIS, the Financial Stability Forum (FSF) was set up in April 1999 to promote international financial stability through information exchange and international co-operation in financial supervision and surveillance (Box VI.1). The Forum brings together on a regular basis the national authorities responsible for financial stability for deliberations.

6.9 In response to the crises of the 1990s, the IMF and the World Bank introduced the Financial Sector Assessment Programme (FSAP) to identify strengths, risks and vulnerabilities of financial systems in member countries and also to highlight the financial sector development needs. A key component of FSAP is to assess compliance with the international standards and codes in the financial sector, including the Basel Core Principles of Banking Supervision (BCP); the Insurance Core Principles framed by International Association of Insurance Supervisors; the International Organisation of Security Commissions (IOSCO) Objectives and Principles for Securities Regulation; the IMF’s Code of Good Practices in Monetary and Financial Policies; and Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommendations on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism.

6.10 In the Indian context, the RBI Act, 1934 does not explicitly mandate the Reserve Bank to ensure financial stability. However, the twin objectives of monetary policy in India have evolved over the years as those of maintaining price stability and ensuring adequate flow of credit to facilitate the growth process (Reddy, 2007). The relative emphasis between the twin objectives is modulated depending upon the prevailing circumstances and is articulated in the policy statements by the Reserve Bank from time to time. Consideration of macroeconomic and financial stability is also subsumed in the mandate. In recent years, financial stability has assumed priority in the conduct of monetary policy. The institutional environment has been changing rapidly including, in particular, due to the implementation of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, 2003 and the increased integration of domestic financial markets with the global markets. In this context, it has become important to recognise and exploit the strong complementarity between macroeconomic performance and financial stability.

Box VI.1: FSF Report on Highly Leveraged Institutions: Latest Updates

The Financial Stability Forum (FSF) brings together senior representatives of national financial authorities (central banks, supervisory authorities and treasury departments), international financial institutions, international regulatory and supervisory groupings, committees of central bank experts and the European Central Bank. The FSF is serviced by a small secretariat housed at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland. The FSF seeks to coordinate the efforts of these various bodies so as to promote international financial stability, improve the functioning of markets, and reduce systemic risk.

The FSF constituted a Working Group in 1999 to assess the challenges posed by highly leveraged institutions (HLIs). The Group was also required to achieve consensus on supervisory/regulatory measures to minimise their destabilising potential. The creation of the Group followed two main episodes. First, the near-collapse of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), which raised concerns about the potential systemic risks posed by a HLI. Second, the spillover effects from the 1997-98 crises in Asia and Russia, when the authorities in some small and medium-sized open economies were concerned that HLIs had exerted a destabilising impact on their markets. The Group made 10 recommendations in the first report submitted in 2000 which, inter alia, included stronger counterparty risk, enhanced regulatory oversight of HLI credit providers, greater risk sensitivity in bank capital adequacy regulation and enhanced national surveillance of financial markets. The FSF had subsequently published a report assessing progress against its recommendations in 2001 and 2002.

In its latest update of the Report on Highly Leveraged Institutions (2000) released on May 19, 2007, produced in response to a request by G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, the FSF reassessed the financial stability issues and systemic risks posed by hedge funds. The report recognises the contribution hedge funds have made to financial innovation and market liquidity. At the same time, it noted heightened risk measurement, valuation and operational challenges for market participants and made the following recommendations:

• Supervisors should act in such a manner that core intermediaries continue to strengthen their counterparty risk management practices.

• Supervisors should work with core intermediaries to further improve their robustness to the potential erosion of market liquidity.

• Supervisors should explore and evaluate the extent to which developing more systematic and consistent data on core intermediaries’ consolidated counterparty exposures to hedge funds would be an effective complement to existing supervisory efforts.

• Counterparties and investors should act to strengthen the effectiveness of market discipline, including by obtaining accurate and timely portfolio valuations and risk information.

• The global hedge fund industry should review and enhance existing sound practice benchmarks for hedge fund managers in the light of expectations for improved practices set out by the official and private sectors.

Reference:

Financial Stability Forum (2007), Update of the FSF Report on Highly Leveraged Institutions, May; www.fsf.org.

6.11 In order to develop a safe, sound and efficient financial system in India, best standards prevailing internationally are suitably adapted to the domestic conditions. Besides voluntarily participating as one of the earliest member countries in the FSAP of the World Bank and the IMF in 2001, India also undertook a self-assessment of all the areas of international financial standards and codes by a committee (Chairman: Dr. Y.V. Reddy). Drawing upon the experience gained during the 2001 FSAP and recognising the relevance and usefulness of the analytical details contained in the Handbook on Financial Sector Assessment jointly brought out by the World Bank and the IMF, in September 2005, the Government of India, in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India, decided to undertake a comprehensive self-assessment of the financial sector. Accordingly, in September 2006, a Committee on Financial Sector Assessment (CFSA) was constituted (Chairman: Dr. Rakesh Mohan; Co-Chairman: Dr. D. Subbarao).

6.12 Though the importance of financial stability is well recognised by the national authorities as well as by international organisations, difficulties in striking a right balance in financial regulation are also acknowledged. While effective regulatory oversight is required to avoid any systemic risk, there is also a need to provide an environment which is conducive to competition and innovation. Rapid changes in the international financial landscapes and processes of innovation have made it difficult for regulators to strike a balance between regulatory safeguards and providing competitive environment. Keeping in view this dilemma, the Reserve Bank has undertaken several policy initiatives to strengthen the financial institutions in India as also to infuse competition in the financial sector. Section 2 of this Chapter discusses these measures in respect of commercial and co-operative banks, financial institutions, and non-banking financial companies. Section 3 draws a comparative picture of Indian scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) vis-a-vis select countries in terms of operational efficiency and financial soundness indicators. Developments in financial markets from the perspective of financial stability are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 discusses the progress made in the payment and settlement systems and Section 6 identifies some risks to financial stability. Section 7 presents an overall assessment of the financial stability conditions in India.

2. Strengthening of Financial Institutions

6.13 The resilience of financial institutions is one of the pre-requisites for financial stability. In practical terms, it implies that banks and other financial institutions should be able to absorb shocks in a way that the financial intermediation process is not interrupted. This does not rule out the possibility of individual bankruptcies. Rather for the economy as a whole, financial institutions in aggregate should be able to perform the function of intermediation in an efficient manner even in the wake of shocks to the system. The financial regulators and supervisors, therefore, set out norms, standards and guidelines to be followed by the financial institutions so that competitive forces do not undermine the fundamentals determining the resilience and financial strength of these institutions.

6.14 The financial system in India comprises a large number of financial institutions and financial markets for catering to the financing requirements of the various segments of society. Financial institutions under the regulatory purview of the Reserve Bank encompass commercial banks, urban co-operative banks (UCBs), regional rural banks (RRBs), financial institutions and non-banking financial companies. These financial institutions differ not only in their corporate structure, size, sources of funds, but also in terms of purposes for which loans are extended and the targeted clientele. These institutions also differ in terms of financial and soundness indicators. Besides, the Reserve Bank’s regulatory and supervisory powers over various sets of institutions also vary. The responsibility of regulating and supervising banks including urban co-operative banks (UCBs) is vested with the Reserve Bank under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. However, urban co-operative banks are also regulated by the State Governments (by Registrar of Co-operative Societies in the case of UCBs operating in single State and the Central Registrar of Co-operative Societies in the case of UCBs having presence in more than one State). The Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 also empowers the Reserve Bank to regulate some of the financial institutions. With the amendments to the RBI Act in 1997, a comprehensive regulatory framework in respect of non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) was put in place. In respect of State and district central co-operative banks, and regional rural banks, while the Reserve Bank is the regulator, the supervision is vested with the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD).

6.15 As a regulator of the major part of financial system, it is imperative for the Reserve Bank to look at all aspects of financial institutions, including their balance sheets, profitability, non-performing loans and capital adequacy requirements. Therefore, as part of its continuous endeavour to promote financial stability, the Reserve Bank has been taking several initiatives to promote resilience of the financial sector and strengthen financial institutions under its purview. However, the focus of the Reserve Bank’s regulatory and supervisory initiatives has been calibrated in a careful manner.

6.16 Furthermore, the Reserve Bank has also to account for the objective conditions that exist in India while introducing new risk management systems, upgrading existing ones and developing new markets for risk management products. It needs to continually keep in view the differential risk-bearing capacities among different economic agents in the country. Even among different financial intermediaries, let alone households and farmers, there is the coexistence of small and widely dispersed entities, such as primary agricultural credit societies (PACSs), rural and urban co-operative banks, public sector banks, new private sector banks, and foreign banks, with each having different degrees of sophistication related to risk management. Hence, the Reserve Bank’s approach to the introduction of modern risk management instruments and systems in the country has, per force, to be cognisant of country’s requirements and capacity2.

Scheduled Commercial Banks

6.17 As alluded to earlier, a wide variety of financial institutions exist in India. Since scheduled commercial banks constitute systemically the most important segment of the Indian financial system, the focus of reforms in the initial years was on strengthening commercial banks with a view to promoting financial stability. Measures initiated since the early 1990s to strengthen commercial banks included the introduction of prudential norms relating to income recognition, asset classification, provisioning, capital adequacy, exposure norms; putting in place institutional arrangements to manage NPAs; permission to public sector banks to raise capital from the capital market up to 49 per cent; allowing entry of new private sector banks and liberal entry of foreign banks to improve efficiency of financial institutions; and strengthening of corporate governance norms, including ‘fit and proper’ criteria for the owners, directors and management of the private sector banks. The supervisory mechanism has also been strengthened by introducing risk-based supervision (on a pilot basis), instituting prompt corrective action (PCA) mechanism, compilation of financial soundness indicators, and encouraging merger of weak financial entities with strong financial entities. Appropriate risk management practices have also been put in place. All these measures have had a profound effect on commercial banks and the commercial banking sector has emerged stronger over the years. However, at the same time, some new challenges have emerged. These are smooth transition to Basel II; raising of capital by banks to meet Basel II requirements; and maintain asset quality in the wake of rapid credit expansion. In order to meet these challenges, the Reserve Bank initiated several measures during 2006-07.

Macro Level Measures

6.18 The stipulation of reserve requirement has traditionally been the key instrument of monetary policy. A greater flexibility in use of these instruments provides greater manoeuvrability to the central bank in ensuring monetary stability. Amendments to the Section 24 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, effective January 23, 2007, have removed the floor rate of 25 per cent for statutory liquidity ratio (SLR), providing greater flexibility to the Reserve Bank in prescribing the SLR requirement. With the amendment to the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, effective April 1, 2007, the floor and ceiling on the cash reserve ratio (CRR) have been removed and the Reserve Bank has been empowered to prescribe the CRR depending upon the prevailing monetary conditions.

Prudential Measures

6.19 Following the revised capital adequacy framework of the Basel Committee on Banking and Supervision (BCBS), the final guidelines for implementing the revised framework in India were issued to banks in April 2007.In view of increased capital requirements and for smooth transition to Basel II framework, banks were allowed in January 2006 to augment their capital funds through issuance of innovative perpetual debt instruments (IPDI) eligible for inclusion as Tier I capital and debt capital instruments eligible for inclusion as Upper Tier II capital. The guidelines were reviewed in July 2006 and the banks were advised that the total amount raised by a bank through IPDIs would not be reckoned as liability for calculation of net demand and time liabilities for the purpose of reserve requirements and, as such, would not attract CRR/SLR requirements. Investment by FIIs in IPDI raised in Indian Rupees shall be outside the ECB limit for rupee denominated corporate debt fixed for investment by FIIs in corporate debt instruments.

6.20 With a view to providing a wider choice of instruments to Indian banks for raising Tier I and Upper Tier II capital, guidelines for issuing preference shares as part of regulatory capital were issued on October 29, 2007. It has been decided to allow the banks to issue the following types of preference shares in Indian rupees: i) perpetual non-cumulative preference shares (PNCPS) under Tier I capital; and ii) perpetual cumulative preference shares (PCPS), redeemable non-cumulative preference shares (RNCPS) and redeemable cumulative preference shares (RCPS) under Upper Tier II capital. The addition of above instruments is expected to significantly enhance the range of eligible instruments available to the banks for capital adequacy purposes.

6.21 Recognising the implications of investment pattern of banks on financial stability and with a view to discouraging banks to undertake risky exposures, it was advised to banks in September, 2006 that the exposure of banks to entities for setting up special economic zones (SEZs) or for acquisition of units in SEZs, which included real estate, would be treated as exposure to the commercial real estate sector and banks would have to make provisions as also assign appropriate risk weights for such exposures as per the guidelines laid down for this purpose.

6.22 Considering the high risks inherent in Banks exposure to venture capital funds (VCFs), the prudential framework governing banks’ exposure to VCFs was revised on August 23, 2006. Accordingly, all exposures to VCFs (both registered and unregistered) are deemed on par with equity and hence are reckoned for compliance with the capital market exposure ceilings (ceiling for direct investment in equity and equity linked instruments as well as ceiling for overall capital market exposure) and the limits prescribed for such exposure also apply to investments in VCFs. The quoted equity shares/ bonds/units of VCFs in the bank’s portfolio should be held under ‘available for sale’ (AFS) category and marked-to-market preferably on a daily basis, but at least on a weekly basis in line with valuation norms for other equity shares as per the laid down instructions. Banks’ investments in unquoted shares/bonds/units of VCFs made after issuance of these guidelines are required to be classified under held-to-maturity (HTM) category for initial period of three years and valued at cost during this period. These attract a risk weight of 150 per cent.

6.23 From the point of view of financial stability, controlling the concentration risk on the liability side of banks is as important as the concentration risk on the asset side. More particularly, uncontrolled inter-bank liabilities may have systemic implications, even if the individual counterparty banks are within the allocated exposure. Uncontrolled liability of a larger bank may also have a domino effect. If the level of total inter-bank liabilities is very high, the process of drying up of liquidity can be much faster than one would otherwise expect. In view of this, a comprehensive framework of liability management was put in place in March 2007 so that banks are aware of the risks inherent in following a business model based on large amount of inter-bank liabilities and the systemic risks implied in such model. Banks were advised to fix an appropriate limit, with the approval of their boards of directors, for their inter-bank liabilities, keeping in view their business model, within the prudential limit of 200 per cent of their net worth based of their audited balance sheet as on March 31, of the previous year. Banks with more than 11.25 per cent CRAR based on their audited balance sheet as on March 31 of the previous year, are allowed to have an additional limit of 100 percentage points. i.e., up to the limit of 300 per cent of the net worth.

6.24 Banks’ loans and advances portfolio typically follows a pro-cyclical path, i.e., increases at a faster pace during an expansionary phase and at a lower pace during a recessionary phase. During an expansionary phase and accelerated credit growth, banks usually underestimate the level of inherent risk and the converse holds true during the recessionary phase. This phenomenon is not effectively addressed by the prudential specific provisioning requirements as they capture risk ex post but not ex ante. It is, therefore, imperative to build up provisioning to cushion banks’ balance sheets in the event of a downturn in the economy or credit weaknesses surfacing later.

6.25 Rapid expansion of credit during three years in succession (2004-07), particularly high credit growth in the real estate sector, outstanding credit card receivables, loans and advances qualifying as capital market exposure and personal loans were viewed as a matter of concern from the point of view of asset quality of banks. Therefore, the general provisioning requirement for banks (excluding RRBs) on standard advances in respect of specific sectors, i.e., personal loans, loans and advances qualifying as capital market exposures, non-deposit taking systemically important (NBFCs-ND-SI) and commercial real estate loans was increased from 0.40 per cent to 1.0 per cent in May 2006 and further to 2.0 per cent in January 2007.

6.26 Thus, banks are required to make a minimum general provisioning for standard assets at four different rates on a global loan portfolio basis (Table VI.1). As hitherto, these provisions would be eligible for inclusion in Tier II capital for capital adequacy purposes up to the permitted extent. In terms of extant guidelines, provisioning for sub-standard assets is required to be made at 10 per cent for secured exposures and 20 per cent for unsecured exposures. The provisioning requirements for doubtful assets are

Table VI.1: Provisioning Requirement for |

Standards Assets |

(Per cent) |

Category |

Requirement |

1 |

2 |

A. |

Direct advances to the agricultural and |

|

|

SME sectors |

0.25 |

B. |

Residential housing loans beyond |

|

|

Rs. 20 lakh |

1.00 |

C. |

Personal loans (including credit card |

|

|

receivables), loans and advances |

|

|

qualifying as capital market exposures, |

|

|

commercial real estate loans, and |

|

|

loans and advances to non-deposit |

|

|

taking systemically important NBFCs |

2.00 |

D. |

All other advances not included in |

|

|

(A), (B) and (C) above |

0.40 |

graded, depending on the period for which an asset has remained doubtful. The provisioning requirement for doubtful assets, at present, varies in the range of 20 per cent to 100 per cent on the secured portion, while it is 100 per cent on the unsecured portion.

6.27 Higher provisioning for unexpected loan losses improves the overall financial strength of banks and the stability of the financial sector. In order to further strengthen the financial system, banks were urged to voluntarily set apart provisions above the minimum prudential levels as a desirable practice. This may be achieved by banks by either making higher level of specific provisions for NPAs or by making a floating provision for NPAs. In terms of the Reserve Bank’s guidelines issued on February 4, 1994, banks were permitted to set-off the floating provisions, wherever available, against provisions required to be made as per the then prevailing prudential guidelines on provisioning. However, the use of floating provisions to set-off against provisions required to be made as per prudential guidelines prescribed appeared to have been used for smoothening of profits in some cases. Hence, the guidelines were reviewed and revised guidelines were issued on June 22, 2006.

6.28 In terms of the guidelines, the floating provisions should not be used for making specific provisions as per the extant prudential guidelines in respect of non-performing assets or for making regulatory provisions for standard assets. The floating provisions can be used only for contingencies under extraordinary circumstances for making specific provisions in impaired accounts after obtaining board’s approval and with prior permission of the Reserve Bank. The boards of the banks are required to lay down an approved policy as to what circumstances would be considered extraordinary. To facilitate banks’ boards to evolve suitable policies in this regard, it was clarified by the Reserve Bank on March 13, 2007 that the extraordinary circumstances refer to losses which do not arise in the normal course of business and are exceptional and non-recurring in nature. These extraordinary circumstances could broadly fall under three categories, viz., general (unexpected loss to banks due to civil unrest, collapse of currency in a country and natural calamities and pandemics), market (general meltdown in the markets) and credit (exceptional credit losses). Floating provisions cannot be reversed by credit to the profit and loss account. These provisions, however, can be netted off from gross NPAs to arrive at disclosure of net NPAs. Alternatively, they can be treated as part of Tier II capital within the overall ceiling of 1.25 per cent of total risk-weighted assets.

6.29 Monetary stability also contributes to financial stability. Notwithstanding some spikes in inflation rate on some occasions in recent years, overall monetary stability and monetary actions of the Reserve Bank have reinforced financial stability. In recent years, the Reserve Bank raised the risk weights in respect of banks’ exposures to certain sectors (such as commercial real estate loans). This measure, apart from moderating the flow of credit, also helped in protecting the banks’ balance sheets.

NPA Resolution

6.30 The high level of non-performing loans (NPLs) has been a major reason for banking crisis in many countries. This often accentuated the pressure to restructure the banking system which involved substantial fiscal cost to the Government (Box VI.2). In the Indian context, several mechanisms were followed by the authorities to recover the past dues which have enhanced recoveries of NPAs by SCBs over the years (Table VI.2).

6.31 The draft guidelines on restructuring/ rescheduling were issued in June 2007 so as to align the existing guidelines on restructuring of advances with the provisions under the revised corporate debt restructuring (CDR) mechanism. With a view to providing an additional option and developing a healthy secondary market for NPAs, guidelines on sale/purchase of NPAs were issued in July 2005 covering the procedure for purchase/ sale of non-performing financial assets (NPFA) by banks, including valuation and pricing aspects; and prudential norms relating to asset classification, provisioning, accounting of recoveries, capital adequacy and exposure norms, and disclosure requirements. The matter was reviewed in response to difficulties expressed by banks and the guidelines were partially modified in May 2007. It was stipulated that at least 10 per cent of the estimated cash flows should be realised in the first year and at least 5 per cent in each half year thereafter, subject to full recovery within three years.

Box VI.2: NPL Management – Cross Country Experience

Globally, the level of non-performing loans was estimated at about US $1.3 trillion during 2003, of which the Asian region accounted for about US $ 1 trillion, or about 77 per cent of global NPLs (Ernst & Young, 2004). Peak NPLs as per cent of total advances increased to over 20 per cent in several Asian economies during the 1997 crises. In Latin America and developed economies, these figures peaked to uncomfortable levels during the mid 1990s, coinciding primarily with some sort of crises (Table 1). These numbers have since declined sharply to more manageable levels as a result of bank restructuring of which NPLs management was an integral part. By 2004, except for China, Thailand and Malaysia, most countries had low to moderate levels of NPLs. The gross NPL levels in India, which were 7.2 of per cent of total advances at end-March 2004, declined to 2.4 per cent by end-March 2007.

The underlying reasons for problem of non-performing loans vary across countries. The high NPLs level in most of the Asian countries coincided with South East Asian crisis in the latter half of the 1990s. Some of the major factors responsible for NPLs include deterioration in business performance of the state enterprises (China), failure of real estate sector to perform as per the expected trajectory of investors (Thailand and Japan), interest rate controls and selective credit allocations (Korea), slowdown triggered by overvalued exchange rate and lack of financial discipline in bank directors extending loans to companies owned by themselves (Mexico). In Turkey, the problem of NPLs in state banks was mainly the result of politically motivated lending (Steinherr, Tukel, and Ucer, 2004; Reddy K.P. 2002; and Desmet, 2000).

The resolution of the NPLs has two aspects, viz., the ‘stock’ and the ‘flow’ problem. The ‘stock’ problem deals with banks’ current balance sheets - raising capital and removing NPLs. The ‘flow’ problem concerns with improving the quality of banks’ earnings to arrest future deterioration in banks’ balance sheet. This usually involves operational restructuring to improve efficiency, which encompasses improved credit assessment, specialisation, better information systems and cost cutting. The most common method adopted by different countries to resolve the NPLs problems was the use of asset management companies (AMCs) in the crisis resolution process. Some other options available to deal with NPLs, inter alia, include recapitalisation, loan swap and debt for debt exchange. Under loan swap, banks write-down loans to market value, then swap loans among themselves. Debt for debt exchange requires revision of loan contracts after negotiations between parties, often leading to reduction in interest rate and extension of maturity on debt contracts.

High level of NPLs often requires restructuring of the banking system, the overall cost of which includes losses in terms of output and employment apart from the fiscal cost. Thus, measuring overall cost of a banking crisis is difficult. The fiscal cost, on the other hand, is easier to specify and measure. The fiscal costs may broadly be defined in terms of gross cost to the public sector (outlays of government and central bank on liquidity support; purchase of impaired assets; deposits payments; and recapitalisation through purchase of equity or subordinated debt) and net cost to the public sector (gross outlays are netted against resources generated from the sale of acquired assets and equity stakes, and repayment of debt by recapitalised entities). These costs have been estimated to be substantially large. According to an estimate from 40 episodes of banking crises across countries, governments spent on an average 12.8 per cent of national GDP to clean up their financial systems (Honohan and Klingebiel, 2000 and 2001). The percentage was even higher (14.3 per cent) in developing countries. Some crises entailed much larger outlays. For instance, the governments spent as much as 40–55 per cent of GDP in the early 1980s crises in Argentina and Chile. Hoelscher and Quintyn (2003) provide an estimate of comparable fiscal costs across countries of various banking crises during 1981-2003. The costs have varied sharply, which ranged from small amounts (close to zero) in Russia and the United States to more than 50 per cent in Indonesia.

References:

Honohan, P. and Klingebiel, D. (2000), Controlling Fiscal Costs of Banking Crises; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2441.

Honohan, P. and Klingebiel, D. (2001), The Fiscal Cost Implication of an Accommodating Approach to Banking Crises; Journal of Banking and Finance.

Hoelscher, D.S. and Quintyn, M. (2003), Managing Systemic Banking Crises; Occasional Paper; IMF.

Reddy, K.P. (2002), A Comparative Study of Non-Performing Assets in India in the Global Context – Similarities and Dissimilarities, Remedial Measures; www.upan.org

Desmet. K. (2000), Accounting for the Mexican Banking Crisis; Emerging Markets Review; vol.1.

Alfred Steinherr, A., Tukel, A., and Ucer, M. (2004), The Turkish Banking Sector Challenges and Outlook in Transition to EU Membership; Centre for European Policy Studies; EU-Turkey Working Papers No. 4/August.

Ernst & Young (2006), Global Nonperforming Loan Report, 2006; www.ey.com

Ernst & Young (2004), Global Nonperforming Loan Report, 2004; www.ey.com

Table 1: Gross Non-performing Loans (NPLs) of |

Banking Systems |

(Per cent of total advances) |

Country |

Peak |

Year of peak |

NPLs, |

|

NPLs |

NPLs |

2004 |

China |

42 |

.. |

12.8 |

Korea |

25 |

1997-99 |

1.9 |

Malaysia |

25 |

1997-99 |

11.7 |

Thailand |

47 |

1997-99 |

11.9 |

Brazil |

15 |

1995-97 |

3.8 |

Mexico |

13 |

1995-97 |

2.8 |

Turkey |

16 |

2001 |

6.0 |

Japan |

9 |

2002 |

2.9 |

Sweden |

11 |

1991-93 |

0.9 |

India |

23* |

1993 |

7.2 |

|

|

|

|

* : For public sector banks.

Source :BIS documents; IMF website

(country documents and

Global Financial Stability Reports). |

Table VI.2: Recoveries Effected by SCBs |

(Rs. crore) |

Year |

Recoveries |

2000-01 |

16,409 |

2001-02 |

17,638 |

2002-03 |

23,183 |

2003-04 |

28,004 |

2004-05 |

26,940 |

2005-06 |

29,087 |

2006-07 |

27,176 |

|

|

Note : Data on recoveries effected during the year, which

include recoveries due to upgradation, actual recoveries and recoveries due to

compromise/write- offs, by scheduled commercial banks (SCBs).

Source : Off-site Returns (domestic). |

Strengthening of Risk Management Practices

6.32 Banks are now facing increased risk on account of greater fluctuation in prices, exchange rates and interest rates, which underscore the need for developing regular systems for stress testing. Internationally, stress testing has become an integral part of banks’ risk management systems and is used to evaluate the potential vulnerability to some unforeseen events or movements in financial variables.

6.33 There are broadly two categories of stress tests used in banks, viz., sensitivity tests and scenario tests. Sensitivity tests are normally used to assess the impact of change in one variable (for example, a high magnitude parallel shift in the yield curve, a significant movement in the foreign exchange rates and a large movement in the equity index) on the bank’s financial position (Box VI.3).

Scenario tests include simultaneous moves in a number of variables, for instance, equity prices, oil prices, foreign exchange rates, interest rates, and liquidity based on a single event experienced in the past. The need for banks in India to adopt ‘stress tests’ as a risk management tool was emphasised in the Annual Policy Statement for 2006-07. Accordingly, guidelines on stress testing were issued by the Reserve Bank on June 26, 2007. Banks are required to put in place appropriate stress test policies and the relevant stress test framework for various risk factors by September 30, 2007 and make formal stress testing operational from March 31, 2008.

Consolidation and Amalgamation

6.34 The increased competition has provided impetus to bank mergers and acquisitions globally. Apart from meeting the challenges of increased competition, the mergers and amalgamations may also be triggered by the deterioration in the financial health of the institutions, in particular those which are no more financially viable. The institutions which are on the verge of collapse adversely affect the interests of depositors and may sometimes trigger contagion. Thus, from the financial stability perspective, mergers and amalgamation could be used as a tool for strengthening the financial system. In India, a conscious approach is followed towards consolidation and merger of smaller banks to reap the benefits of synergy and provide strength to the banking system. During 2006-07 and the first half of 2007-08, four banks were merged/amalgamated with other banks as detailed in Chapter 3 (Section 2).

Supervisory Measures

6.35 From the financial stability point of view, crisis prevention is the major objective of financial regulators and supervisors. This involves continuous monitoring of potential risks and vulnerabilities that may threaten the health of the financial system. The success in preventing the occurrence of crisis depends on the process of information gathering, technical analysis, monitoring and assessment. The analytical process involves gathering information about macroeconomic performance and various aspects of the financial system through supervisory, regulatory and surveillance mechanism. The supervisory process based on information on individual institutions could be gainfully aided by the information on economy’s position in the business and credit cycles because macroeconomic and market performance provide the background against which the operational performance of individual institutions should be assessed. Thus, the supervisory framework plays a critical role in maintaining suitable conditions for financial stability and putting in place adequate safeguards so that the impact of shocks on the financial system is minimised3. The Reserve Bank has also put in place a robust supervisory framework comprising on-site and off-site supervision. The focus of supervisory measures during 2006-07 was on strengthening the monitoring mechanism of financial conglomerates (FCs).

6.36 The emergence of FCs in India has posed new challenges. The major issue in the regulation of FCs is their exposure to two or more sector-based regulatory regimes. This leads to gaps or overlaps in the overall supervisory process. This, in turn, often makes it difficult to obtain all the relevant information required to effectively supervise and regulate these institutions. The effective supervision of FCs requires a coordinated approach among the supervisors across sectors. Several initiatives, therefore, have been taken in consultation with the peer regulators to strengthen the FC monitoring framework for effective supervision of the FCs. In terms of the definition suggested by the Working Group on Financial Conglomerates (Chairperson: Ms Shyamala Gopinath), 23 financial conglomerates were identified. Many of identified FCs, however, not only had few entities within their fold but also had limited operations beyond one market segment. Intra-group transactions in some of these conglomerates were also few. It was, therefore, felt that it was not effective to subject such groups to focussed FC monitoring. Accordingly, the criteria for identification of FCs were revisited in order to focus on major financial groups which are systemically important and, therefore, require effective supervisory mechanism. In terms of the revised criteria, a FC is defined as a cluster of companies belonging to a group which has significant presence in at least two financial market segments. Banking, insurance, mutual fund and NBFC (deposit taking and non-deposit taking) are considered as financial market segments.

Box VI.3: Measurement of Interest Rate Risk

Interest rate risk is the risk of adverse impact of changes in market interest rates on the financials of a financial institution, particularly on earnings or net interest income (NII) and equity. Identification, quantification and measurement of interest rate risk have assumed critical importance, especially in the deregulated environment and reinforced by the requirements of Pillar II of Basel II Capital Accord.

There are different techniques for measurement of interest rate risk such as traditional maturity gap analysis, duration, and simulation. There are two separate, but complimenting, perspectives for measuring a bank’s interest rate risk exposure, viz., earnings perspective and economic value perspective. The earnings perspective involves ascertaining the impact of changes in interest rates on NII. This approach, also known as Earnings at Risk (EaR), analyses the impact from a short term perspective. The economic value perspective involves an assessment of the present value of expected net cash flows discounted to reflect market rates. It focuses on the sensitivity of a bank’s net worth to fluctuations in interest rates and identifies risk from the long-term perspective.

The maturity gap analysis involves distribution of interest rate sensitive assets (RSAs), liabilities (RSLs) and off-balance sheet positions into a certain number of pre-defined time bands according to their maturity (fixed rate) or time remaining for their next repricing (floating rate) whichever is earlier. Assets and liabilities lacking definite repricing intervals (e.g. savings bank, cash credit and overdraft) or with actual maturities varying from contractual maturities (embedded option in bonds with put/call options, loans, cash credit/overdraft and time deposits) are assigned time bands according to the judgment, empirical studies and past experiences of banks. In order to evaluate the impact on the earnings, the RSAs in each time band are netted against the RSLs to produce a repricing gap for that time band. A positive gap indicates that bank has more RSAs than RSLs. A positive or asset sensitive gap implies that the bank’s NII will increase if interest rate goes up and vice versa. The gap is used as a measure of interest rate sensitivity. The positive or negative gap is multiplied by assumed interest rate changes to derive the EaR.

Duration or Macaulay’s duration is computed as a weighted average of the time until cash flows are received. The weights equal the present value of each cash flow as a fraction of the security’s current price, and time refers to the length of time in the future until payment or receipt. It is measured in units of time. A slight variation to Macaulay’s duration is Modified Duration which is defined as the approximate percentage change in price for a 100 basis point change in yield. Modified duration equals Macaulay’s duration divided by (1+YTM). It has the useful feature of indicating how much the price of a security will change in percentage terms for a given change in interest rates.

In the context of immunisation, duration analysis enables a bank to mitigate the impact of interest rate risk by matching duration of assets and liabilities with the preferred holding period. Duration gap models focus on managing net interest income or the market value of shareholders’ equity by recognising the timing of all cash flows for every security on a bank’s balance sheet. Unlike static gap analysis, which focuses on rate sensitivity or the frequency of repricing, duration gap analysis focuses on price sensitivity. A bank’s interest rate risk is indicated by comparing the weighted average duration of assets with the weighted average duration of liabilities. As with the Gap Analysis, the sign and magnitude of duration gap provide information about when a bank potentially wins and loses, and the magnitude of the interest rate bet. Simulation is a more sophisticated interest rate risk measurement system than that based on simple maturity/repricing schedules. Simulation techniques typically involve detailed assessment of the potential effects of changes in interest rates on earnings and economic value by simulating the future path of interest rates, shape of yield curve, changes in business activity, pricing and hedging strategies and their impact on cash flows.

In the Indian context, beginning 1993, administrative restrictions upon interest rates have been steadily eased and at present all interest rates, barring a few, have been deregulated. This has exposed banks to the interest rate changes and consequently interest rate risk has become an important source of vulnerability for banks. Besides, deregulation of interest rates, the norms for classification and valuation of investment portfolio have been aligned to international standards. Banks are required to classify their investment portfolio into three categories, viz., ‘held for trading’ (HFT), `available for sale’’(AFS) and ‘held to maturity’ (HTM). Investments classified under HFT and AFS form the trading book and are required to be marked to market at regular intervals and their depreciation is provided for. Prior to 2005, particularly between 1997 and 2005, Indian banks held Government securities way above the statutory requirement due to various reasons such as lack of credit offtake, existing high non-performing assets and capital adequacy requirement for loans. Though this approach of holding excess Government securities insulated Indian banks from credit risk and need for holding higher regulatory capital, it exposed them to high interest rate risk. Incidentally, this brought windfall gain to the banking industry during the financial years 2002-03 and 2003-04 as interest rates declined. However, as a result of steady rise in yields subsequently, banks were required to book substantial depreciation on their investment portfolio. Regulatory succour had to be provided which allowed banks, as a one time measure, to transfer securities from trading book to banking book to protect their bottomline. In the process, banks’ holding of securities in banking book (HTM) increased substantially, and these were effectively insulated from interest rate risk.

The Reserve Bank has been carrying out periodic analysis to assess the interest rate sensitivity of the banking system. Apart from EaR analysis, duration analysis of investment portfolio of banks is carried out at periodic intervals based on methodologies suggested by BCBS in ‘Principles for the Management and Supervision of Interest Rate Risk’ (September 2003). A periodic sensitivity analysis gauges the likely impact on the investment portfolio of banks for 100, 125 and 150 basis points increase in interest rate and the extent of cushion available to banks to absorb the erosion in their economic value. Yields and coupons are changed to reflect the current scenario. To get an idea of the banking system’s capacity to absorb such shocks, the cushion available by way of unrealised gains on investment portfolio and cumulative provision made in depreciation account as calculated. The net erosion in economic value is reduced from banks’ regulatory capital to assess the impact on their capital adequacy. Supervisory action is initiated with identified outliers as part of the regular supervisory process.

6.37 In order to appropriately focus on the supervisory issues, the format of the quarterly FC return was amended to include information on gross/net NPAs and provisions held for the impaired assets, bad debt, fraud in any group entity, ‘holding out’ operations undertaken by the group, other assets, and change in accounting policies. While the FC monitoring framework looks at the specified financial intermediaries (SFIs), i.e., entities which are regulated by the Reserve Bank, SEBI, IRDA or NHB, the format of the returns has been suitably modified to capture intra-group transactions and exposures involving regulated and un-regulated entities of the group in order to have a better appreciation of the systemic risk emanating from the group as a whole.

6.38 With a view to minimising the adverse impact of fraud activities on the financial system, a Fraud Monitoring Cell (FrMC) was created in June 2004 for centralised monitoring of frauds detected in entities regulated by the Reserve Bank, viz., commercial banks, urban co-operative banks, financial institutions and non-banking financial companies. The Reserve Bank, in May 2006, had circulated to banks some of the best practices which could be adopted in order to reduce the incidence of frauds in the areas of housing loans. In November 2006, the Reserve Bank alerted banks to be cautious while remitting funds from the accounts of non-residents based on requests received through e-mail/fax messages. They were asked to put in place appropriate systems to verify the authenticity of the messages thoroughly before effecting remittance. Initiatives were also taken to prevent the cross-border movement of money for disruptive activities (Box VI.4).

6.39 To make an assessment of financial stability conditions in India, a Committee on Financial Sector Assessment (CFSA) was constituted by the Government of India in September 2006 (Chairman: Dr. Rakesh Mohan; Co-Chairman: Dr. D. Subbarao). The central plank of the assessment is based on three mutually reinforcing pillars, viz., (i) financial stability assessment and stress testing; (ii) legal, infrastructural and market development issues; and (iii) assessment of the status and progress in implementation of international financial standards and codes. To assist in the process of assessment, the CFSA has constituted four Advisory Panels for the assessment of (i) Financial Stability and Stress Testing; (ii) Financial Regulation and Supervision; (ii) Institutions and Market Structure; and (iv) Transparency Standards. The Advisory Panels will prepare separate reports covering each of the above aspects. To provide the Panels with technical notes and background material, the CFSA had set up Technical Groups consisting of officials representing mainly regulatory agencies and the Government in all the above subject areas which have progressed with technical work in respective areas. The CFSA would publish Advisory Panel reports and also its own report. The CFSA is expected to complete the assessment by March 2008.

Box VI.4: Combating Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Other Market Abuses

In financial transactions, the probity of customer and purity of funds have always been the regulatory concerns for the Reserve Bank. Various guidelines in this regard were issued to banks in respect of production of permanent account number (PAN), photograph of the customer, not allowing cash transaction in excess of a threshold limit in cases of remittance funds, monitoring transactions vis-à-vis the negative list issued by the UN Security Council from time to time with a view to nurturing a proper ‘know your customer’ (KYC) culture in the industry. The KYC guidelines were revisited in November, 2004 in the context of the recommendations made by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on anti-money laundering (AML) standards and combating financing of terrorism (CFT) and the paper issued on Customer Due Diligence (CDD) for banks by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Banks have reported full compliance to the revised KYC/AML/CFT guidelines in regard to formulation of policy in this respect duly approved by their boards of directors and dissemination of procedural guidelines to rank and file down the line for smooth implementation. The major thrust after November 2004 is to prevent banks from being used, intentionally or unintentionally, by criminal elements for money laundering or terrorist financing activities and to enable banks to know/understand their customers and their financial dealings better which, in turn, would help them manage their risks prudently. While the major objective of the policy is to ensure that no account is opened in anonymous or fictitious/benami name(s) for misuse by criminals and terrorists, adequate care has been taken in the formulation of policy to avoid disproportionate cost to banks and a burdensome regime for the customers.

The Government of India has also put in place a legislative framework through enactment of Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), 2002. Consequent to notification of Rules under PMLA 2002, a reporting regime has been prescribed to banks for making available cash and suspicious transaction reports to Financial Intelligence Unit-India (FIU-IND). While banks enjoy impunity from civil proceeding for their reporting to FIU-IND under the PMLA, they have been cautioned by the Reserve Bank against tipping off to customers in cases relating to suspicious transaction reports to FIU-IND.

In the wake of 9/11 developments, FATF prescribed 9 special recommendations (SRs) to enable prevention of misuse of the financial systems for the purpose of financing terrorist activities. SR VII deals with wire transfers and the precautionary measures related thereto to be ensured by banks/FIs while effecting such transactions. In pursuit of combating financing of terrorism through the conduit of banking channels, the Reserve Bank has advised banks to ensure that all wire transfer transactions are accompanied by full originator information such as name, account number and address of the customer originating the transaction so that appropriate investigating agencies have instant access to such information, if need be. These instructions are applicable to both domestic and cross border wire transfer transactions. Banks have been advised to consider restricting or even terminating their business relationship with the correspondent banks, if they fail to furnish information on the remitter despite instructions to that effect.

Other Financial Institutions

6.40 Apart from scheduled commercial banks, other financial institutions such as regional rural banks, co-operative banks, financial institutions (FIs) and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) play a crucial role in the development process of the economy. The smooth functioning of these institutions is also important from the point of view of overall financial stability. Besides, in view of the wider outreach of these institutions, particularly RRBs and co-operative institutions, and an important role these institutions can play in furthering the cause of financial inclusion, the Reserve Bank has taken several initiatives to improve the operational efficiency and financial soundness of these institutions.

Regional Rural Banks and Rural Co-operative Banks

6.41 Regional rural banks have played an important role in purveying rural credit. Financially sound network of RRBs could strengthen financial stability conditions while providing a crucial mechanism of mobilising resources required for sustained economic growth. RRB, however, faced several problems which prevented the realisation of full potential benefits of these institutions. The area of operations of RRBs was very limited and they carried high risk due to exposure only to the target group. RRBs suffered from inadequate skills in treasury management for profit orientation and inadequate exposure and skills to innovate products limiting the lending portfolios. The performance of RRBs was affected due to lack of operational autonomy as the RRBs had to look up to sponsor banks, Government, NABARD and the Reserve Bank for most decisions. Financial viability of several RRBs was, thus, undermined by these problems affecting the process of financial intermediation and having implications for financial stability.

6.42 With a view to strengthening RRBs, the Government initiated the State level amalgamation of RRBs sponsor bank-wise in September 2005. This process was carried further during 2006-07 as 37 more banks were amalgamated. In all, 147 RRBs have been amalgamated so far September 2005 to September 2007 to form 46 new RRBs, sponsored by 19 banks in 17 States. As a result, the total number of RRBs declined from 196 to 95 as on September 30, 2007. The structural consolidation of RRBs has resulted in the formation of new RRBs, which are financially stronger and bigger in size in terms of business volume and outreach. This will enable them to take advantages of the economies of scale and reduce their operational costs.

6.43 Following the announcement made in the Union Budget 2007-08 that the RRBs having a negative net worth would be recapitalised in a phased manner, modalities for recapitalisation are being worked out in consultation with select sponsor banks and the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD).

6.44 With a view to improving the performance of RRBs and giving more powers and flexibility to their boards in decision making, the Reserve Bank had constituted the Task Force on Empowering the RRB Boards for Operational Efficiency (Chairman: Dr. K.G. Karmakar) in September 2006. The Task Force was mandated to suggest areas where more autonomy could be given to the boards, particularly in matters of investments, business development and staffing, viz., determination of staff strength, fresh recruitment, and promotions. In its report submitted on January 31, 2007, the Task Force, inter alia, recommended that (i) the number of directors on the boards of RRBs be raised up to 15 on a selective basis in the case of large sized RRBs created after amalgamation; (ii) selection of chairmen of RRBs be made on merit from a panel of qualifying officers; and (iii) Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act (SARFAESI), 2002 may be extended to RRBs. While some of the recommendations of the Task Force have been implemented, others are under examination. The Government of India has already issued a notification on May 17, 2007 specifying ‘regional rural bank’ as ‘bank’ for the purpose of the SARFAESI Act, 2002.

Urban Co-operative Banks

6.45 Urban co-operative banks form a heterogeneous group in terms of geographical spread, area of operation, size or even in terms of individual performance. Certain infirmities in the sector, however, surfaced that manifested in the form of weakness of some of the entities resulting in erosion of public confidence and causing concern to the regulators as also to the sector at large. One of major problems faced in the case of UCBs was the dual regulatory mechanism under which UCBs are regulated and supervised by both the State Governments, through the Registrars of Co-operative Societies, and by the Reserve Bank. Furthermore, in the case of banks having presence in more than one State, the Central Registrar of Co-operative Societies, on behalf of the Central Government, exercises such powers. The other issues affecting the UCBs were lack of corporate governance, transparency and accountability. Many UCBs were also of suboptimal size, which affected their efficiency and profitability. As discussed in Chapter IV of this Report, NPA ratio of UCBs was significantly higher than that of scheduled commercial banks.

6.46 Recognising the need to mitigate the risk to which the system was exposed, the Reserve Bank endeavoured to provide a regulatory and supervisory framework that would appropriately address the problems of the sector as also the shortcomings of dual control. The need was also felt to set up a supervisory system that was based on an in-depth analysis of the heterogeneous character of urban co-operative banks and one that was in tandem with the policy of strengthening the sector. Keeping these considerations in view, a draft vision document for UCBs was prepared by the Reserve Bank and placed it in the public domain in March 2005 which was finalised thereafter. In pursuance of the proposals in the vision document, the State Governments having a large number of UCBs were approached for signing the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The memorandum, provides the basis for the constitution of the Task Force for Urban Cooperative Banks (TAFCUB) in each State to serve as a forum for the consultative decision making process. Apart from the representatives of the Reserve Bank and the State Government, the TAFCUB has the representatives of the UCBs sector. The TAFCUB identifies the weak but viable (non-scheduled) UCBs in the respective State and frames a time bound programme for revival of such entities. It identifies the nature and extent of funds required to be infused, the changes in management where necessary and suggest periodical milestones to be achieved. Further, UCBs which are not found viable by the TAFCUB, could be required to exit from banking business either through merger with strong banks, if such merger makes economic sense to the acquiring bank, or through voluntary conversion into a cooperative society by paying off the non-member deposits and withdrawing from the payment system. And if there is not other viable option, they could even be taken into liquidation by the Registrar at the behest of the Reserve Bank. As of September 2007, MoUs were signed with 13 States, which cover a total of 83 per cent of UCBs accounting for over 92 per cent of total deposits. The consolidation of the UCBs through the process of merger of weak entities with stronger ones has been set in motion by providing transparent and objective guidelines for granting no-objection to merger proposals. The Reserve Bank, while considering proposals for merger/ amalgamation, confines its approval to the financial aspects of the merger taking into consideration the interests of depositors and financial stability. As on October 30, 2007, a total of 33 mergers had been effected upon the issue of statutory orders by the Central Registrar of Cooperative Societies/Registrar of Co-operative Societies (CRCS/RCS) concerned.

6.47 The Reserve Bank continued its efforts to ensure that the urban co-operative banks emerge as a sound and healthy network of banking institutions, so that they can provide need-based quality banking services, essentially to the middle and lower middle classes and marginalised sections of society4. In order to enable the smaller UCBs to gain strength as visualised in the ‘Vision Document’, banks were classified as Tier I UCBs (unit banks, i.e., banks having branch/s within a single district, with deposits up to Rs.100 crore) and Tier II banks (i.e., all other UCBs). As per the revised prudential norms for Tier I and Tier II banks, while Tier II banks are under the 90-day delinquency norm which is applicable for commercial banks, the 180-day delinquency norm for Tier I banks has been extended by one more year, i.e., up to March 31, 2008. This is intended to provide a measure of relief to the small UCBs in terms of lower provisioning required, which, in turn, would translate into higher profits that could be used to shore up the capital base of these banks.

6.48 In order to ensure that asset quality is maintained in an environment of high credit growth, it was decided in respect of Tier II banks and all other UCBs operating in more than one district (irrespective of deposit size) to increase the general provisioning requirement on standard advances in specific sectors, i.e., personal loans, loans and advances qualifying as capital market exposures and commercial real estate loans from 1.0 per cent to 2.0 per cent. Risk weight on exposure to commercial real estate was also increased from 100 per cent to 150 per cent.

Financial Institutions and Non-banking Financial Companies

6.49 Financial institutions, which historically played an important role in meeting the medium to long-term requirements of the economy, have been repositioning themselves in the changed operating environment. Two large FIs have already converted into banks. It has been the endeavour of the Reserve Bank that FIs operating in the system maintain sound financial health. The Reserve Bank, therefore, has been strengthening financial institutions by extending prudential norms applied to banks to financial institutions with suitable modifications.

6.50 In continuation with the policy initiatives undertaken by the Reserve Bank in recent years for progressive upgradation of the regulatory norms for FIs in convergence with the norms across the financial sector, a number of measures were undertaken during 2006-07. Norms for income recognition, asset classification, provisioning and other related matters concerning Government guaranteed exposures were modified during 2006-07. With effect from March 31, 2007, State Government guaranteed advances and investments in State Government guaranteed securities would attract the asset classification and provisioning norms if the interest and/or principal or any other amount due to the FI remained overdue for more than 90 days.

6.51 Keeping in view the contribution that NBFIs make to the financial sector as financial intermediaries, the Reserve Bank has been continuously emphasising on developing NBFCs into financially strong entities. Streamlining the functioning of non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and implementing prudential measures in this sector assume priority for ensuring financial stability.

6.52 The focus of supervision by the Reserve Bank in recent years has been to ensure that NBFCs function along sound and healthy lines and avoid excessive risk-taking. The regulatory framework for NBFCs underwent significant changes after the amendments in the RBI Act in 1997, which provided comprehensive powers to the Reserve Bank to regulate NBFCs. The amended Act made it mandatory for NBFCs to obtain certificate of registration (CoR) from the Reserve Bank. The total number of NBFCs registered with the Reserve Bank declined from 13,014 at end-June 2006 to 12,968 at end-June 2007. Besides, the number of public deposit accepting companies also declined due to conversion of some NBFCs into non-public deposit accepting activities. This helped in weeding out the weak and unviable NBFCs from the system.

6.53 The focus of supervision in respect of NBFCs is differentiated depending on the asset size of the NBFC and whether it accepts/holds public deposits. To protect depositors’ interests, the regulatory norms are relatively more stringent for those NBFCs that accept public deposits. However, large NBFCs even if they do not accept public deposits are systemically important. In view of this, a reporting system for NBFCs not accepting/holding public deposit and having asset size of Rs.500 crore and above was introduced beginning from the quarter ended September 2004. During 2006-07, a major initiative related to the strengthening of the regulatory framework with regard to systemically important non-banking financial companies was the issuance of prudential guidelines so as to reduce the regulatory gaps. Systemically important non-deposit taking NBFCs were also defined and prudential norms were specified for these entities.

6.54 All non-deposit taking NBFCs (NBFCs–ND) with an asset size of Rs.100 crore and more as per the last audited balance sheet are now considered systemically important NBFCs–ND–SI. These are required to maintain a minimum capital to risk-weighted assets ratio (CRAR) of 10 per cent. Deposit taking NBFCs were further advised that all NBFCs and RNBCs with total assets of Rs.100 crore and above should submit the return on capital market exposure in the prescribed format on a monthly basis within seven days of the close of the month to which it relates. The first such return based on revised criteria was submitted for the month ended April 30, 2007.

Deposit Insurance

6.55 The principal objectives of a deposit insurance system (DIS) are to contribute to the stability of a country’s financial system and to protect less financially sophisticated depositors from the loss of their deposits when banks fail. As per the International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI)’s guidelines on best practices of deposit insurance system, a deposit insurance system needs to be a part of a well-designed financial safety net, supported by strong prudential regulation and supervision, effective laws that are enforced, and sound accounting and disclosure regimes (Box VI.5).

6.56 In India, Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC), which came into existence in its present form in 1978, provides insurance protection up to the specified amount of deposits of all commercial banks, including the RRBs and LABs and most of co-operative banks.

6.57 During 2006-07, a Guide on DICGC was published along with a Brochure on DICGC for easy understanding of the deposit insurance system in India. This has facilitated spread of awareness and instilled confidence in the banks’ customers. To provide further relief to bank customers, the DICGC, on April 27, 2007, reviewed its policy for settlement of claims of joint account holders in the event of liquidation of a bank. In terms of the revised policy, the deposits held in two separate joint accounts in combination of two or more individuals are treated as two or more separate accounts, and each category of the

Box VI.5: Features of a Successful Deposit Insurance System (DIS) and the Position of DICGC

Explicit and limited deposit insurance is preferable to implicit protection as it clarifies the authorities’ obligations to depositors and limits the scope for discretionary decisions that may result in arbitrary actions. Deposit insurers have mandates ranging from narrow, so-called paybox system to those with broader powers and responsibilities such as risk-minimisation, with a variety of combinations in between. Paybox systems largely are confined to paying the claims of depositors after a bank has been closed and normally do not have prudential regulatory or supervisory responsibilities or intervention powers. A risk-minimiser deposit insurer has a relatively broad mandate and accordingly more powers. In recent years, the attention has, however, shifted from the establishment of an explicit deposit insurance scheme to institutional details such as coverage, membership, funding and administration.

In general, membership should be compulsory to avoid adverse selection as in a voluntary system strong banks may opt out if the cost of failures is high and this may affect the financial solvency and the effectiveness of the deposit insurance system. Sound funding arrangements are critical to the effectiveness of a deposit insurance system and the maintenance of public confidence; and this should have available all funding mechanisms necessary to ensure the prompt reimbursement of depositors’ claims after a bank’s failure. Policymakers have a choice between adopting a flat-rate premium system or a premium system that is differentiated on the basis of individual-bank risk profiles. DISs fall into two categories, viz., (i) those funded by banks and (ii) those with no permanently maintained funds lent, where members are required to contribute to the fund after a bank failure occurs.

In this context, a few studies demonstrate that the coverage and funding of deposit insurance schemes have significant impact on the probability with which a country suffers a banking crisis, while others show that the coverage and funding are important determinants of the degree of market discipline exercised by depositors vis-a-vis banks.

Garcia (1999) argued that the structure of the DIS is more likely to be incentive-compatible if membership is compulsory, if coverage is low to deter moral hazard, and if insurance premiums are risk-adjusted to avoid adverse selection. The idea behind risk-adjustment is to moderate the subsidy provided by strong to weaker institutions by allowing sound institutions to pay lower premiums than their competitors who pose greater risk of loss on DIS resources. In addition, depositors need to have confidence in the system, which requires that the DIS be administratively efficient in paying out insured deposits promptly, and that it be adequately funded so that it can resolve failed institutions firmly without delay.

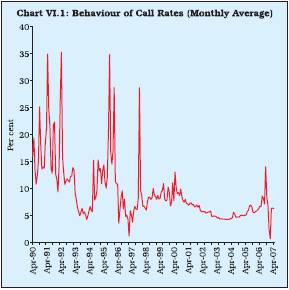

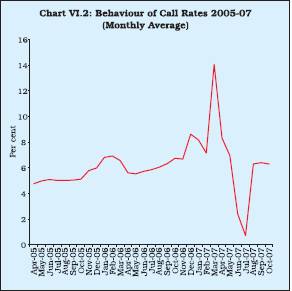

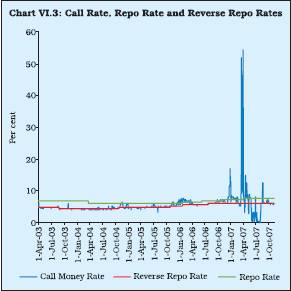

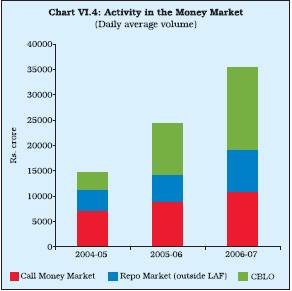

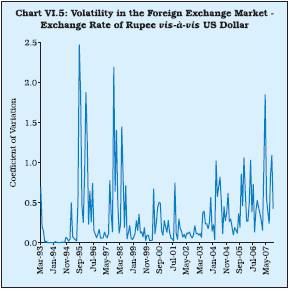

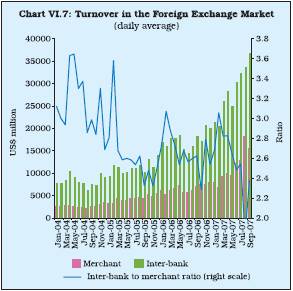

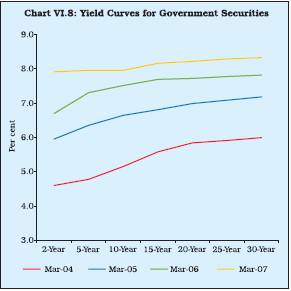

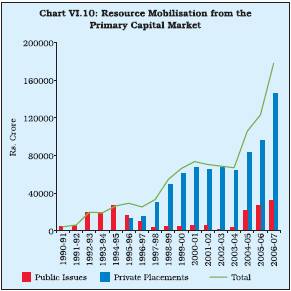

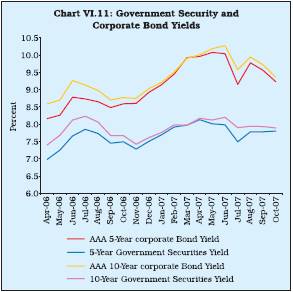

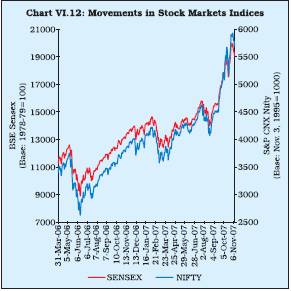

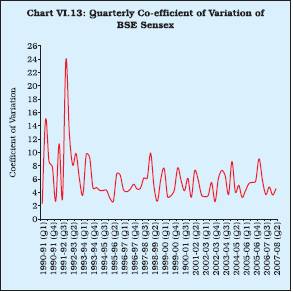

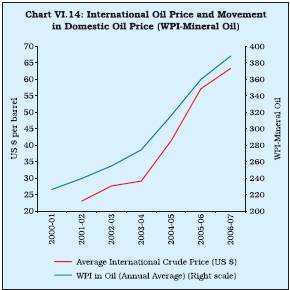

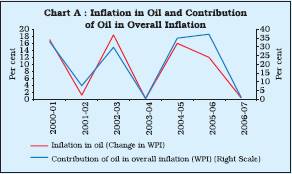

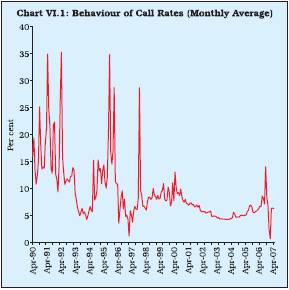

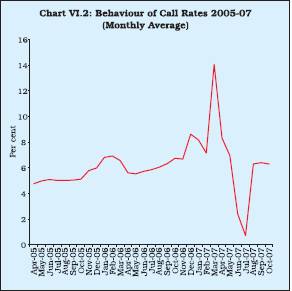

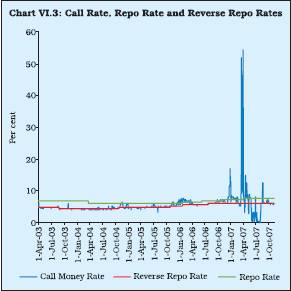

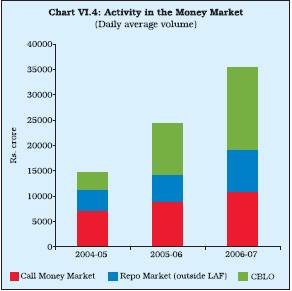

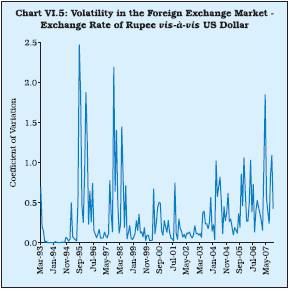

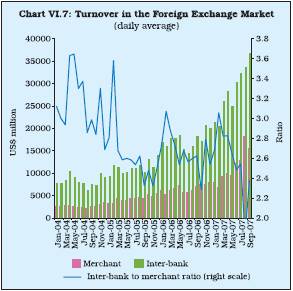

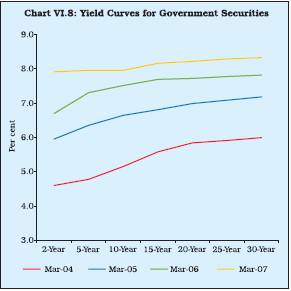

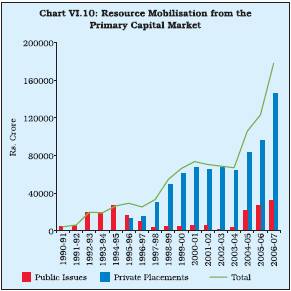

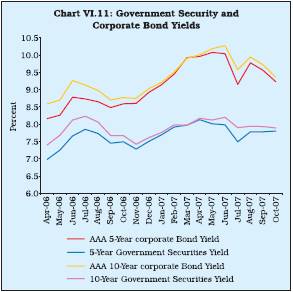

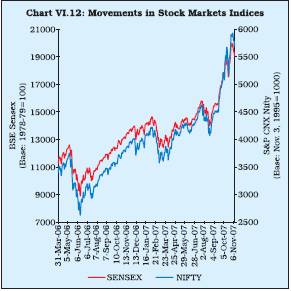

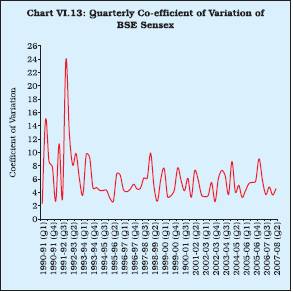

For a deposit insurance system to be effective, it is essential that the public is informed about its benefits and limitations. The objectives of an effective failure-resolution process are to meet the deposit insurers obligations; ensure depositors are reimbursed promptly and accurately; minimise resolution costs and disruption of markets; maximise recoveries of assets; settle bonafide claims on a timely and equitable basis; and reinforce discipline through legal actions in cases of negligence or other wrongdoings. Policymakers should be aware of the potential effects of existing depositor priority laws or statutes on failure-resolution costs and if depositors and the deposit insurer are accorded some superior rights to share in recoveries, their claims must be paid in full before other unsecured claimants are compensated.