IST,

IST,

Monetary Policy Report – October 2023

|

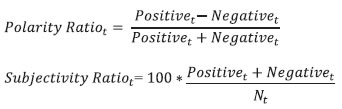

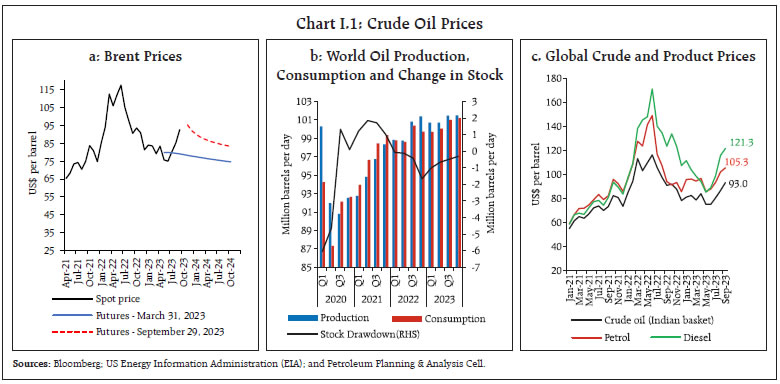

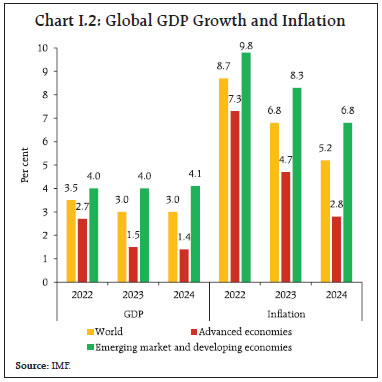

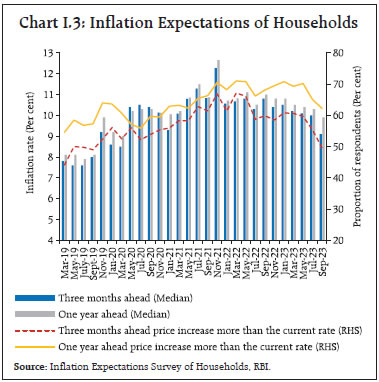

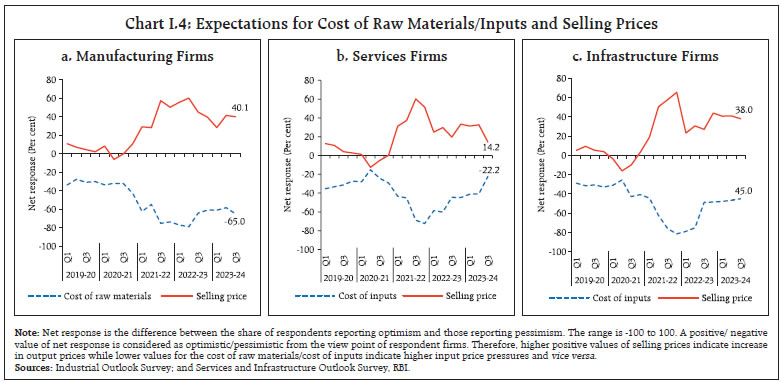

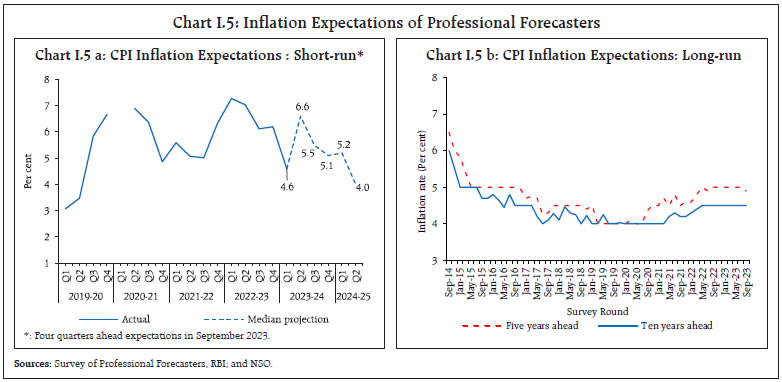

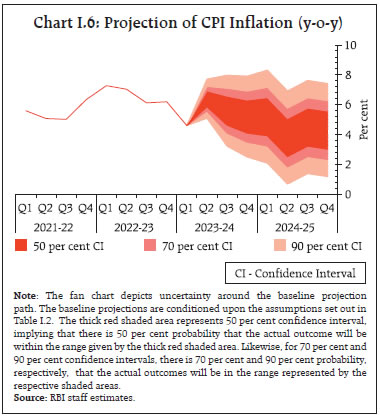

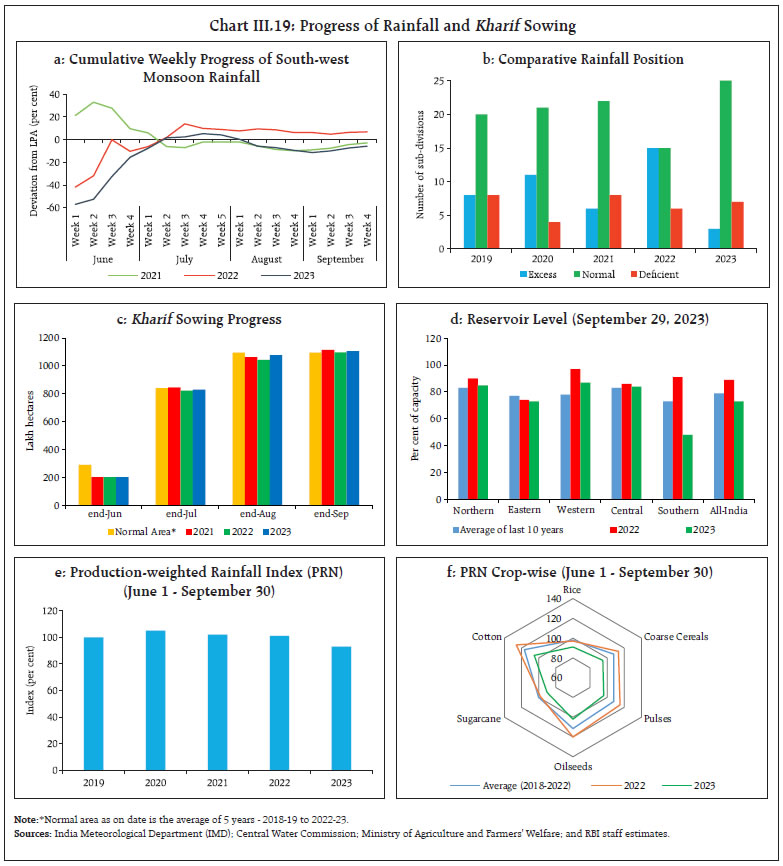

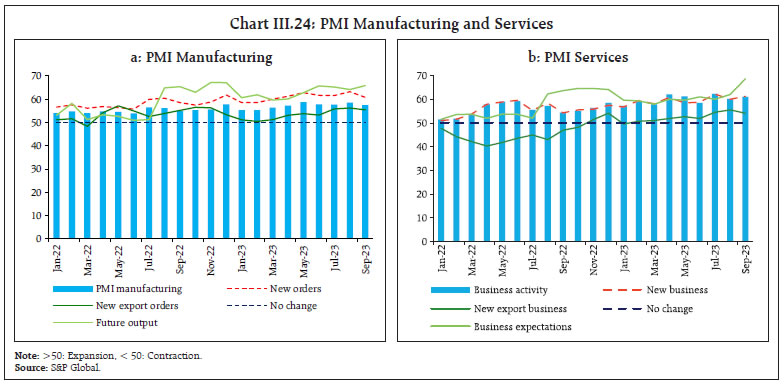

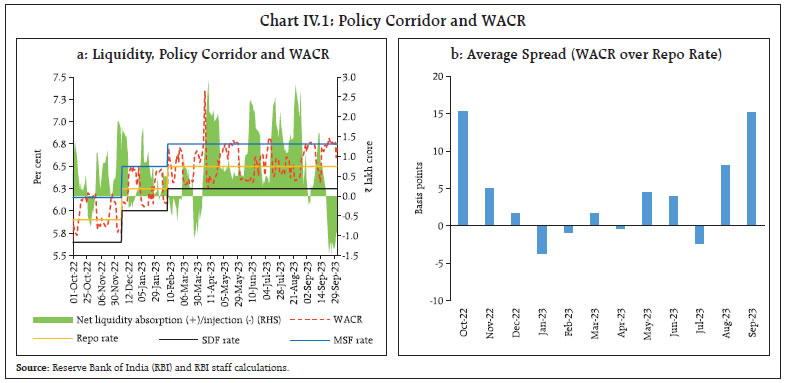

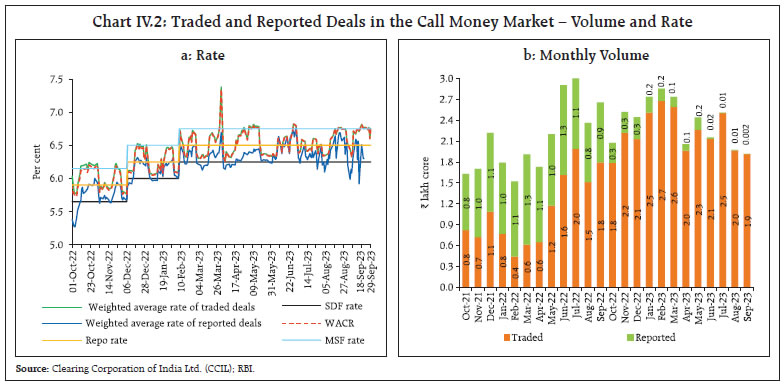

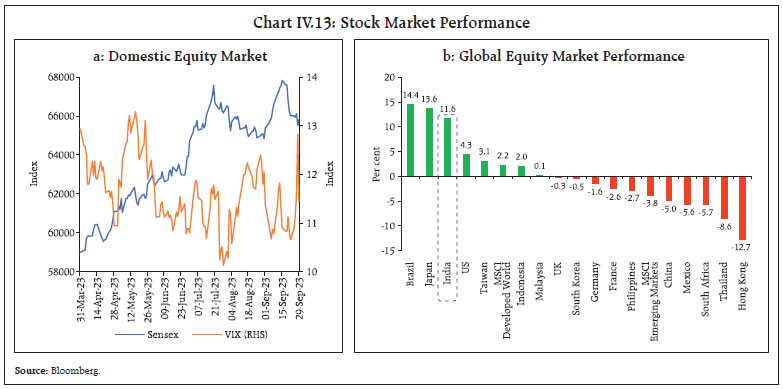

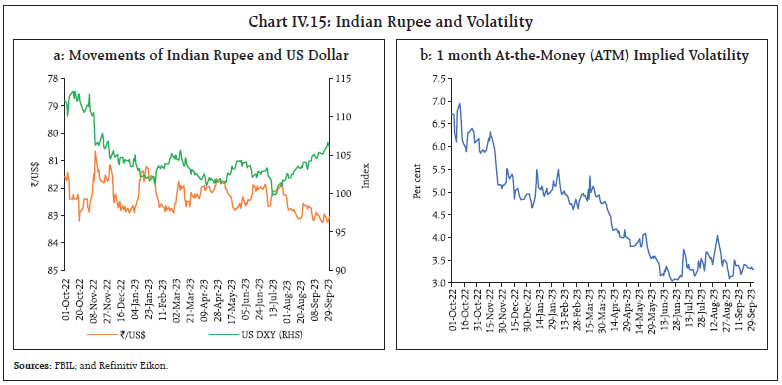

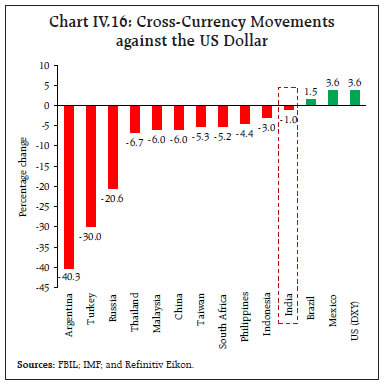

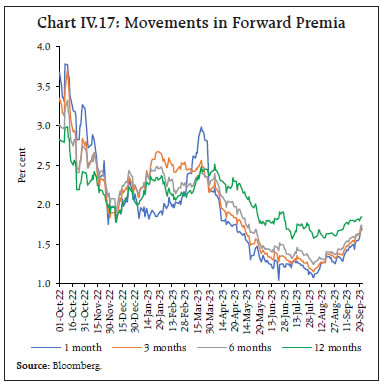

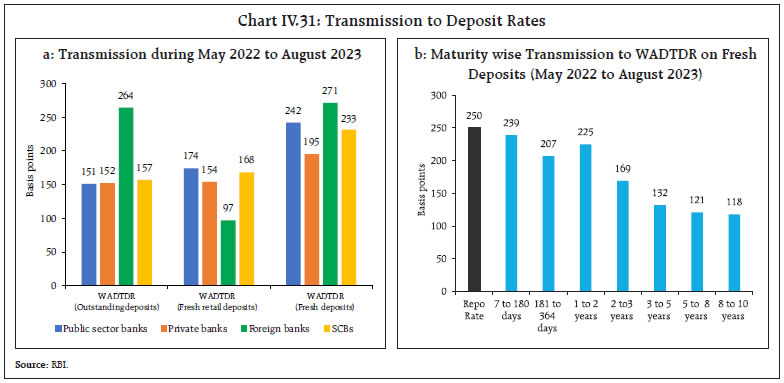

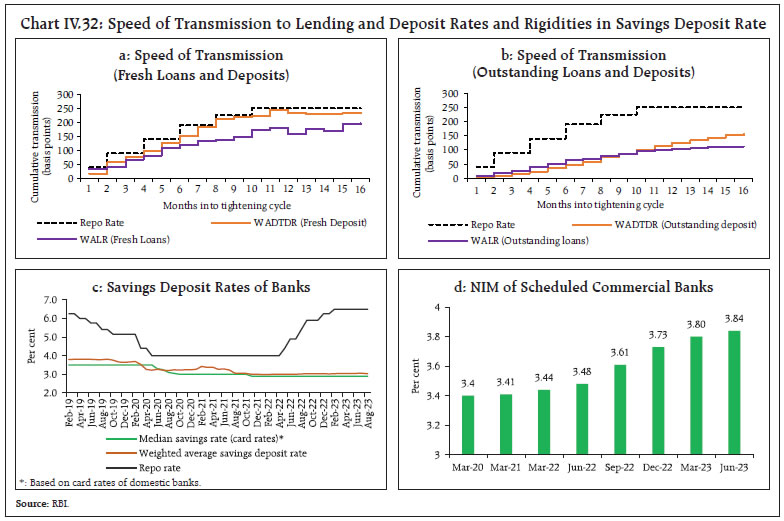

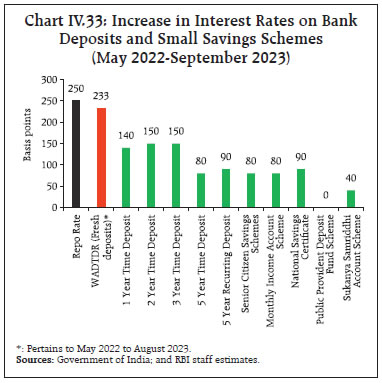

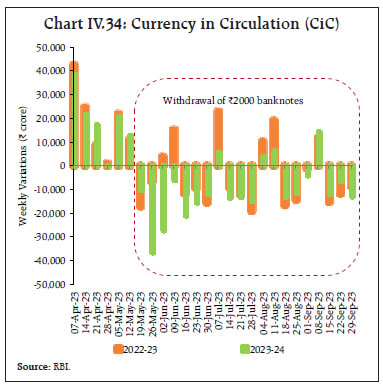

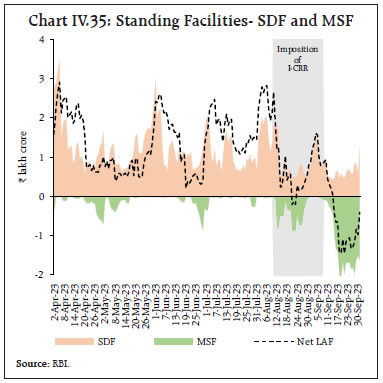

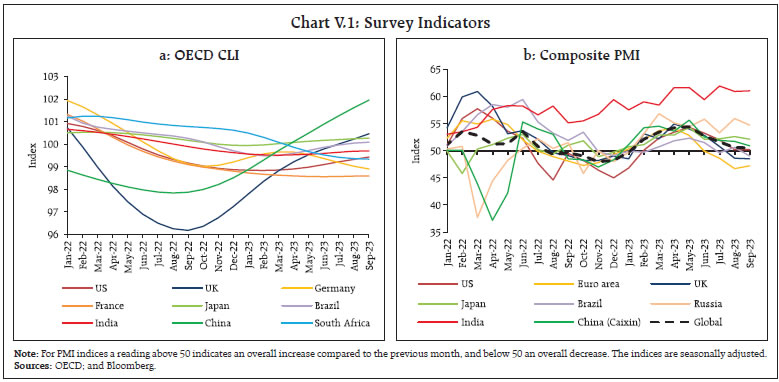

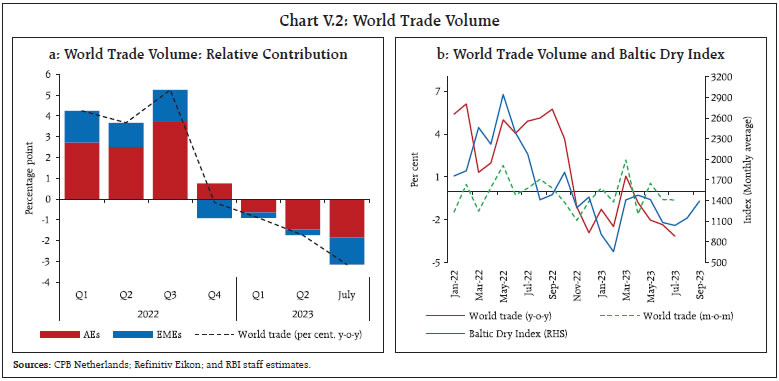

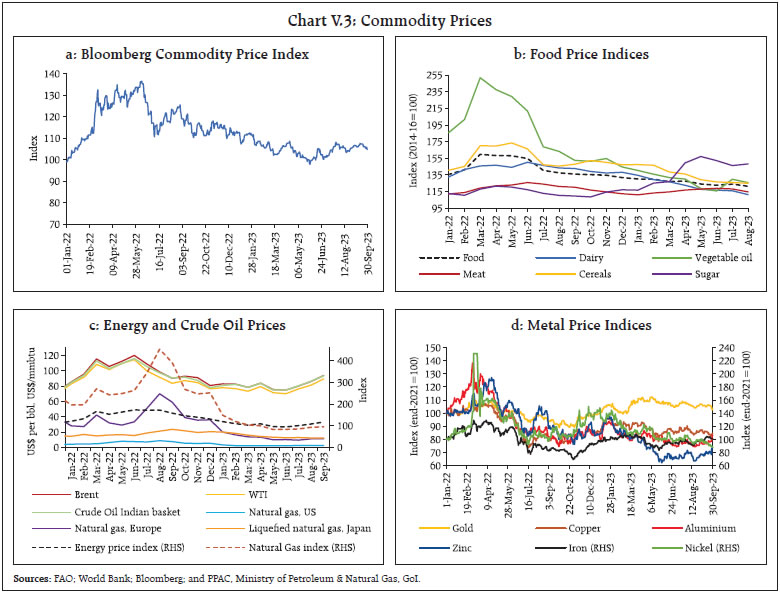

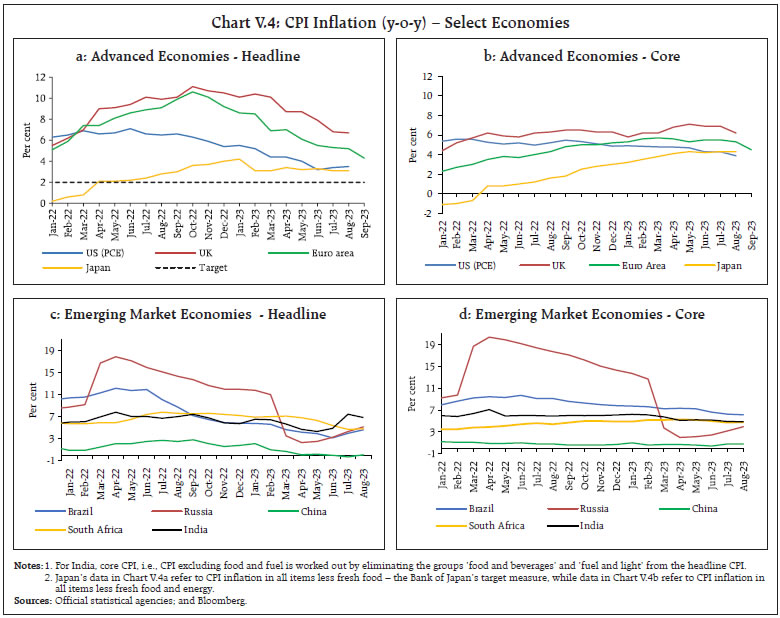

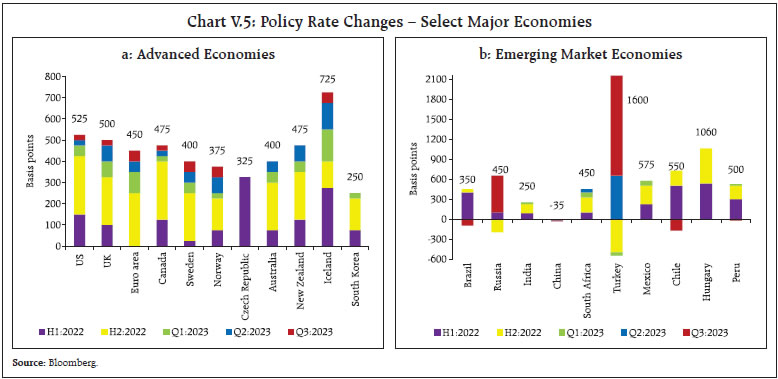

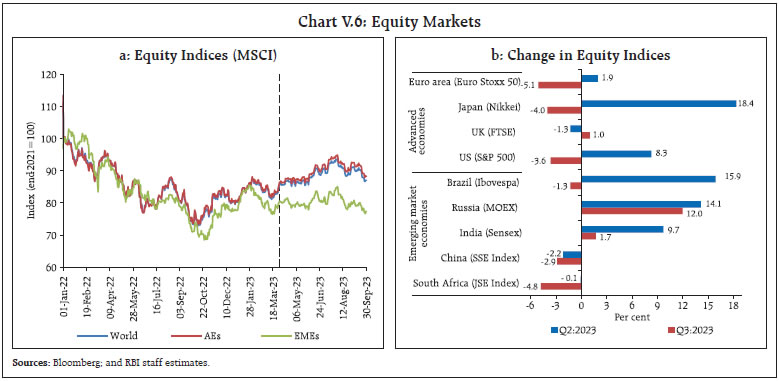

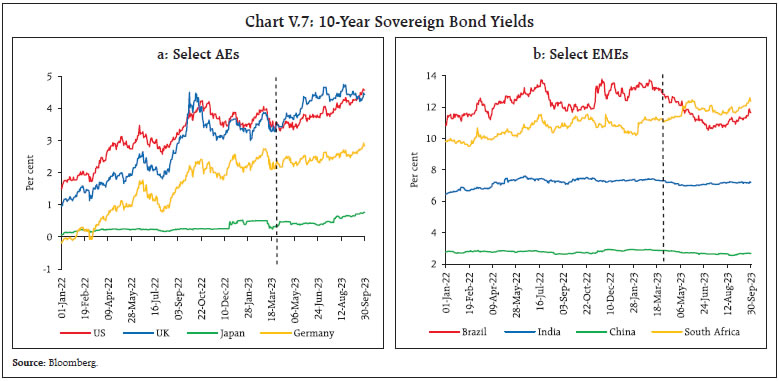

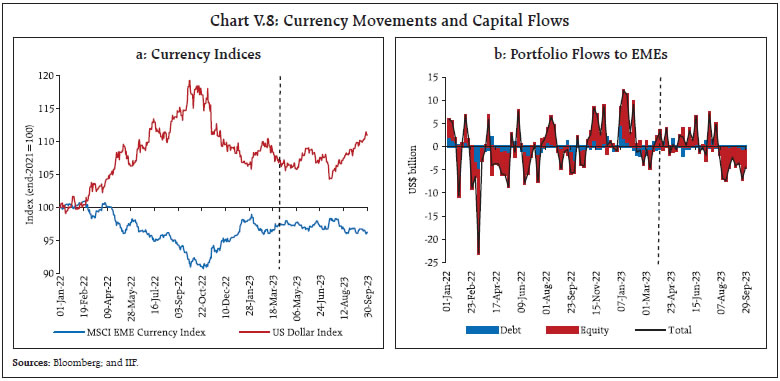

The outlook for domestic economic activity remains resilient in spite of large supply shocks that have pushed up the trajectory of headline inflation. Energy and food price volatility, geopolitical hostilities, tightening external financial conditions and climate shocks are the key risks to the outlook. Monetary policy remains focused on aligning inflation with the target to pave the path for sustained growth in the medium-term. I.1 Key Developments since the April 2023 MPR Global economic activity and trade are slowing, although unevenly across geographies and sectors. Tightening financial conditions in response to monetary actions to address still elevated inflation, persisting geopolitical tensions and growing geoeconomic fragmentation render the outlook fragile. Manufacturing activity is contracting across many countries, while services are relatively resilient. Headline inflation has been gradually easing across the world, however, in most countries, it remains elevated in relation to targets. Core inflation is moderating but at a tardy pace and services inflation is sticky. These concerns are reflected in 'higher for longer' monetary policy settings. In some countries, however, the monetary policy tightening cycle is complete or nearing it or even in accommodation in response to weakening economic activity. Market expectations relating to the global economic outlook are fluctuating widely and sensitive to every incoming information, imparting high volatility. In September, US sovereign bond yields touched their highest levels since the global financial crisis, and the yield curve has seen its longest period of inversion since 1980. Credit growth in major economies is decelerating in response to monetary tightening. After strong gains in the first half of 2023, global equity markets retreated in Q3 (July-September). The US dollar depreciated to a 15-month low in mid-July but has recovered subsequently on better-than-expected US economic data. Crude oil prices firmed up sharply to around US$ 95 per barrel in September in response to extended output cuts by key producing countries. Food prices are volatile on supply concerns arising from the breakdown of the Black Sea deal on Ukrainian grain movements and the El Niño weather phenomenon. Turning to the domestic economy, activity was supported in H1:2023-24 by private consumption and fixed investment, although adverse external conditions are being reflected in a prolonged contraction in net exports. Real gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 7.8 per cent (year-on-year, y-o-y) in Q1:2023-24 (April-June) and high frequency indicators for Q2 suggest that the momentum in activity is being maintained. On the supply side, real gross value added (GVA) is being buoyed by services sector growth. Headline CPI inflation had moderated from an average of 6.7 per cent in 2022-23 to 4.3 per cent in May 2023 in response to monetary policy actions and supply side measures. Reversing these gains under the impact of sporadic food supply shocks, inflation jumped to 7.4 per cent in July and 6.8 per cent in August. On the other hand, core inflation (i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel) has been gradually ebbing down to sub-5 per cent levels. With the cumulative rate hike of 250 basis points (bps) undertaken during May 2022-February 2023 working its way into the economy, the monetary policy committee (MPC) kept the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.50 per cent through H1, and it remains firmly committed to aligning inflation with the target going forward. Monetary Policy Committee: April 2023 - September 2023 When the MPC met in April 2023, the global economy was going through a period of heightened volatility in the wake of banking sector turmoil in some advanced economies (AEs). Domestic CPI headline inflation was ruling above the upper threshold of the tolerance band in January and February, but was expected to soften with a record rabi foodgrains production, easing input cost conditions and normalisation of supply chain pressures. CPI inflation was projected at 5.2 per cent for 2023-24, 10 bps lower than the February projection. Domestic economic activity was seen to be holding up well, and the real GDP growth projection for 2023-24 was raised to 6.5 per cent from 6.4 per cent in the February meeting. Considering these factors and that previous rate hikes were still working through the system, the MPC unanimously decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.50 per cent, but with a readiness to act, should the situation so warrant. The MPC decided by a majority of 5-1 to remain focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation progressively aligns with the target, while supporting growth. At the time of the June 2023 meeting, CPI headline inflation had fallen to 4.7 per cent (April 2023 print) from an average of 6.2 per cent during the previous quarter. The MPC noted that the moderation in CPI headline inflation reflected the combined and continuing impact of monetary policy tightening, supply augmenting measures and the fuller impact of the previous rate hikes which should keep inflationary pressures contained in the coming months. Against this backdrop, the MPC unanimously voted again to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.50 per cent and with a 5-1 vote to continue with its stance of withdrawal of accommodation. In the run up to the August 2023 meeting, headline CPI inflation picked up to 4.8 per cent in June, with sizeable upside pressures on the near-term headline inflation trajectory from a spike in vegetable prices. Factoring in the skewed south-west monsoon outturn, the growing likelihood of an El Niño event and the worsening global food prices outlook, the inflation projection for 2023-24 was revised upwards by 30 bps to 5.4 per cent while the April 2023 projection for real GDP was kept unchanged. Taking into account the cumulative policy repo rate increase undertaken thus far, the MPC unanimously decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.50 per cent with preparedness to undertake policy responses. With a 5 to 1 vote, the MPC reiterated its stance of withdrawal of accommodation. The MPC’s voting pattern reflects the diversity in individual members’ assessments, expectations and policy preferences, a characteristic also reflected in voting patterns of other central banks ( Table I.1). Macroeconomic Outlook Chapters II and III analyse macroeconomic developments relating to inflation and economic activity during H1:2023-24 (April–September 2023). Turning to the baseline assumptions, first, international crude prices have exhibited sizeable two-way movements in H1, easing in April amidst a banking crisis in the US and underwhelming Chinese recovery, but they moved higher beginning July, with Brent crude crossing US dollar (US$) 90 per barrel in September due to production cuts referred to earlier, with some correction in early October. Geopolitical tensions impart significant uncertainty to the outlook (Chart I.1.a and Chart I.1.b). The ‘crack’ spread – the wedge between global petroleum product prices and crude prices – is elevated in view of demand-supply refinery mismatches (Chart I.1.c). Taking into account these developments, the baseline assumption for crude price (Indian basket) is retained at US$ 85 per barrel ( Table I.2).  Second, the nominal exchange rate of the Indian rupee or INR has moved in both directions around the April baseline, varying in a range of INR 81.7-83.3 per US$ in H1. Taking into consideration the uncertainty around US dollar movements, the ebbs and flows of global capital, and international crude oil prices, the baseline assumption for the exchange rate is revised to INR 82.5 per US dollar.  Third, multiple headwinds – tighter monetary and fiscal policies, reduced pent-up demand, financial stability risks, continued geopolitical challenges and geoeconomic fragmentation – weigh heavily on global growth prospects. The global purchasing managers’ index (PMI) for manufacturing has remained in contraction mode since September 2022, while the services PMI is moderating since May 2023, albeit still in expansion mode. In its July 2023 update of the World Economic Outlook (WEO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its global growth forecast for 2023 marginally upwards to 3.0 per cent from its April projection of 2.8 per cent ( Chart I.2). Yet, global GDP growth for 2023 and 2024 (3.0 per cent each) will trail its 2022 level (3.5 per cent) as well as its historical (2000-19) average of 3.8 per cent. Global trade growth (goods and services combined) is projected by the IMF to decelerate from 5.2 per cent in 2022 to 2.0 per cent in 2023.  Looking ahead, the sharp spike in food prices, especially of vegetables, has started correcting (Chapter II). The three months and one year ahead median inflation expectations of urban households fell by 90 and 40 bps, respectively, to 9.1 per cent and 9.9 per cent in the September 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey 1 vis-à-vis the previous round. Notably, inflation expectations fell to a single digit for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic. The proportion of respondents expecting the general price level to increase by more than the current rate declined considerably for both the horizons vis-à-vis the previous round (Chart I.3). Manufacturing firms polled in the July-September 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey expect increased pressures from the cost of raw materials but marginal decline in selling price growth in Q3:2023-24 (Chart I.4a). 2 Services and infrastructure firms expect lower growth in input cost and selling prices in Q3:2023-24 (Charts I.4b and I.4c). 3 In the PMI surveys for September 2023, manufacturing firms reported a decline in input cost inflation but an increase in output price inflation; services firms reported moderation in both input and output price pressures.  Professional forecasters surveyed by the Reserve Bank in September 2023 expect headline CPI inflation to moderate from 6.6 per cent in Q2:2023-24 to 5.5 per cent in Q3, 5.1 per cent in Q4 and 5.2-4.0 per cent in H1:2024-25 (Chart I.5a and Table I.3). 4 Core inflation (i.e., CPI excluding food and beverages, pan, tobacco and intoxicants, and fuel and light) expectation was seen at 4.9 per cent in Q2:2023-24, 4.7 per cent in Q3, 4.6 per cent in Q4 and 4.6-4.7 per cent in H1:2024-25. Long-run inflation expectations of professional forecasters measured by their 5-year ahead expectations softened to 4.9 per cent while 10-year ahead expectations remained unchanged at 4.5 per cent ( Chart I.5b). Looking ahead, the outlook for inflation will be conditioned heavily by food inflation dynamics. The south-west monsoon rainfall has been uneven, with August recording a 36 per cent deficiency in rainfall. Water reservoir levels have dipped and El Niño conditions are taking hold although the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) has turned positive which could limit El Niño effects. Kharif sowing has exceeded last year’s levels but with shortfalls in area under pulses and oilseeds. Global supply chains are improving from their pandemic disruptions. Geopolitical hostilities pose upside risks to global commodity prices across the board – food, crude oil and metals. Taking into account the initial conditions, signals from forward-looking surveys and estimates from time-series and structural models 5 , CPI inflation is projected to average 5.4 per cent in 2023-24 – 6.4 per cent in Q2, 5.6 per cent in Q3 and 5.2 per cent in Q4, with risks evenly balanced (Chart I.6). The 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals for headline inflation in Q4:2023-24 are 4.1–6.3 per cent and 3.5–6.9 per cent, respectively. For 2024-25, assuming a normal monsoon, and no further exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate that inflation will average 4.5 per cent, in a range of 3.8-5.2 per cent. In Q4:2024-25, CPI inflation is projected at 4.3 per cent, with the 50 per cent and the 70 per cent confidence intervals at 3.0–5.6 per cent and 2.3–6.3 per cent, respectively.   The baseline forecasts are subject to several upside and downside risks. The upside risks emanate from more persistent food price increases due to weather-related disturbances, which could then feed into inflation expectations; further hardening of global commodity prices amidst an escalation of geopolitical tensions; and a larger pass-through of input cost pressures to output prices. The downside risks could emanate from an early resolution of geopolitical tensions, a steep correction in global crude and commodity prices in the event of a sharp slowdown in the global growth, and further improvement in supply conditions. Monetary policy communication has emerged as an important tool for managing and anchoring expectations and strengthening monetary transmission in an environment of heightened uncertainty. A textual analysis of the Reserve Bank’s MPRs shows that their tone has been in consonance with the evolving price and output developments, which strengthens the monetary policy communication channel (Box I.1).

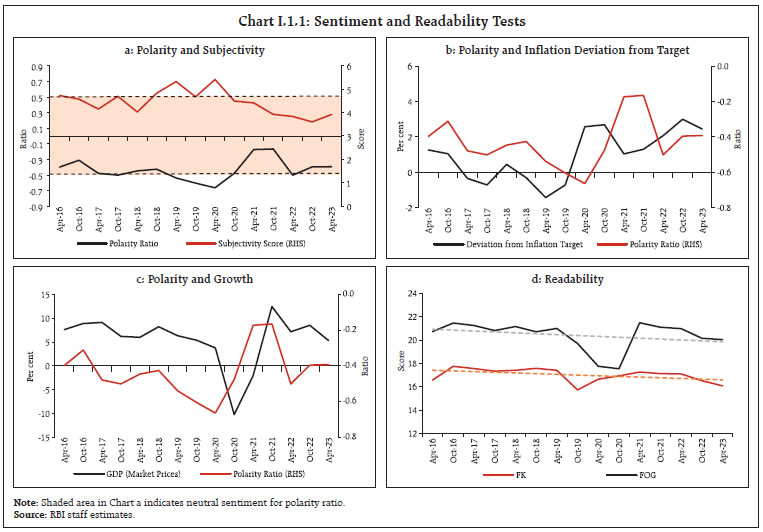

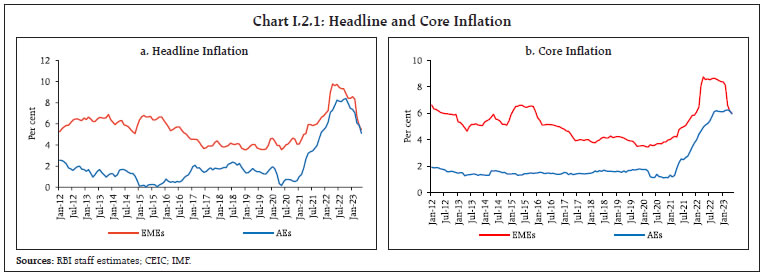

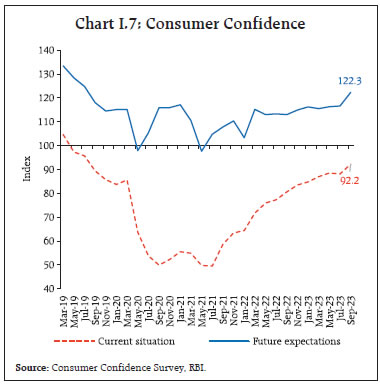

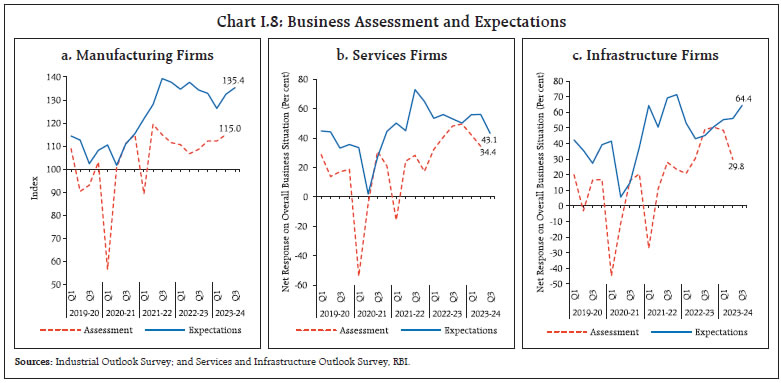

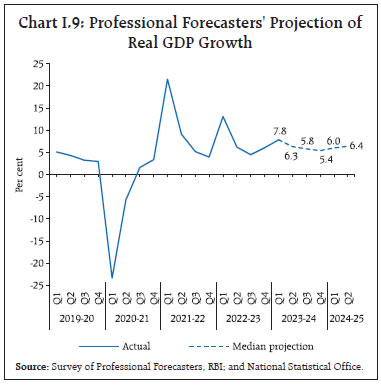

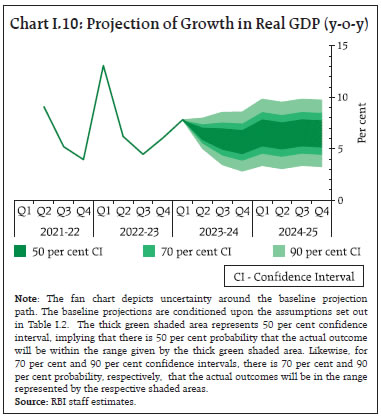

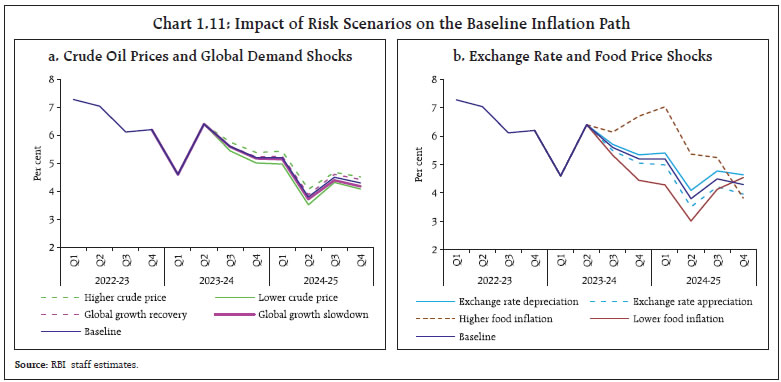

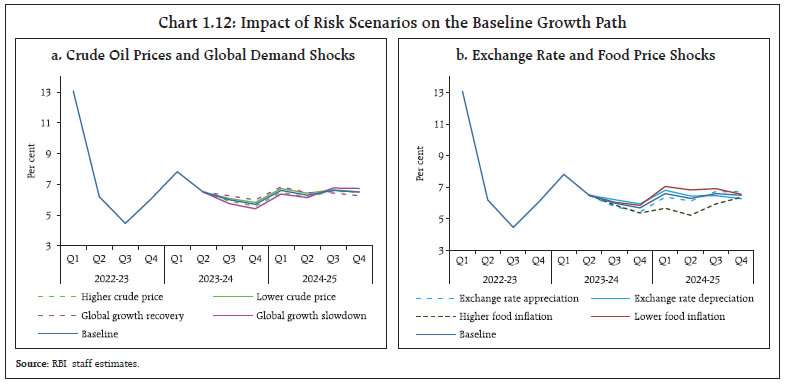

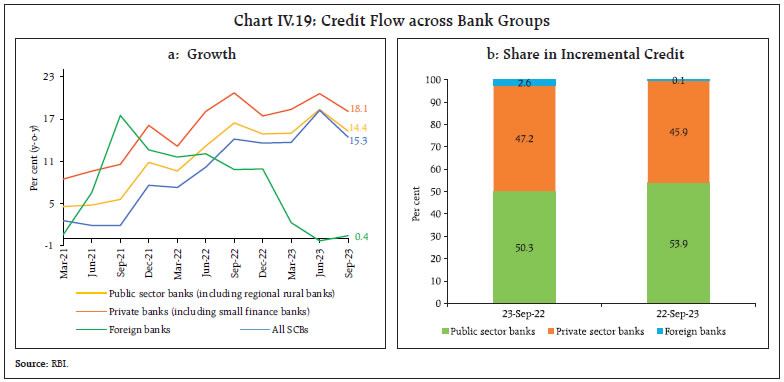

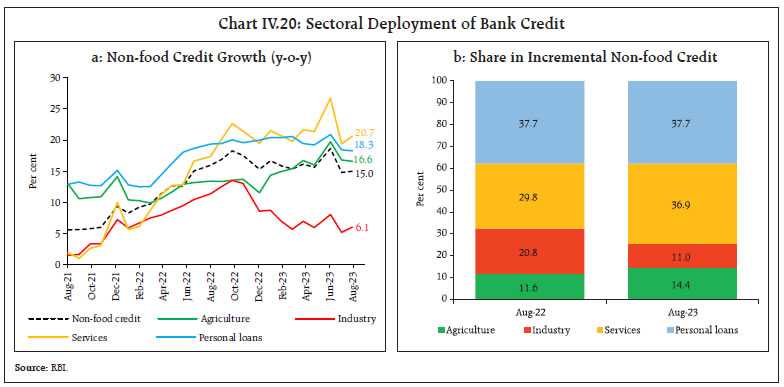

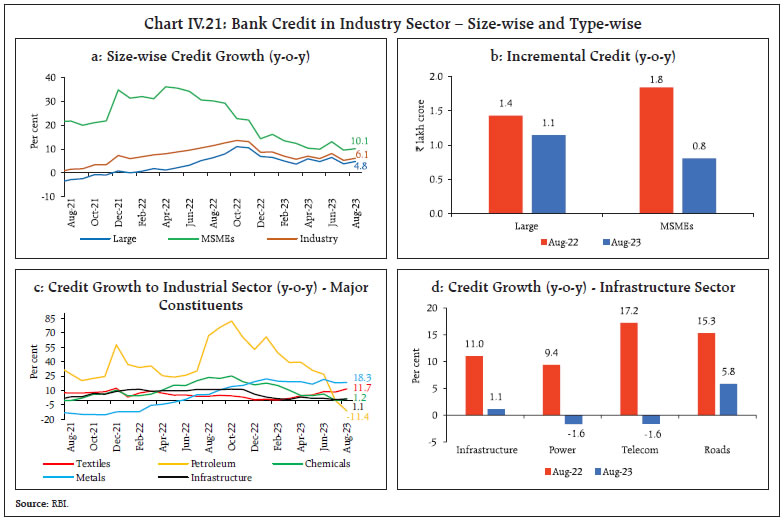

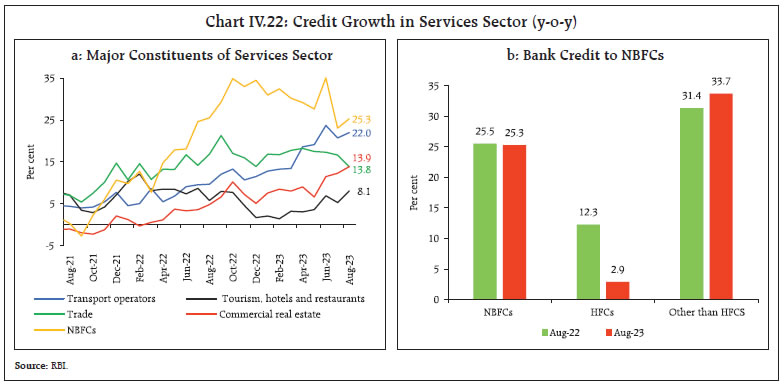

Domestic economic activity is being supported by robust agricultural performance, sustained buoyancy in contact-intensive services, the boost to investment from the government’s thrust on capital expenditure, above trend capacity utilisation in manufacturing, double digit credit growth, and healthier corporate and bank balance sheets. Slowing global growth, the drag from exports, geopolitical risks and volatile global financial conditions, however, weigh heavily on the outlook. Turning to the key messages from forward-looking surveys, consumer confidence (the current situation index) has improved in the September 2023 survey round vis-à-vis the previous round on account of better perceptions on the general economic and employment situation. Consumers’ optimism for the year ahead, measured by the future expectations index, remains upbeat on improved expectations about the general economic situation, employment, and income conditions (Chart I.7). 10  In the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey of July-September 2023, manufacturing firms are optimistic about demand conditions in Q3:2023-24 (Chart I.8a). While the optimism of services sector companies waned in Q3 vis-à-vis the previous round, infrastructure sector companies remain upbeat in terms of the overall business situation (Charts I.8b and I.8c). Recent surveys by other agencies signal a mixed picture on business expectations relative to the previous round (Table I.4). Manufacturing and services firms in the PMI surveys for September 2023 exhibited optimism for the year ahead. The professional forecasters polled in the September 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey expect real GDP growth at 6.3 per cent in Q2:2023-24, 5.8 per cent in Q3, 5.4 per cent in Q4 and 6.0-6.4 per cent in H1:2024-25 (Chart I.9). Taking into account the baseline assumptions, survey indicators and model forecasts, real GDP growth is expected at 6.5 per cent in 2023-24 – 6.5 per cent in Q2; 6.0 per cent in Q3; and 5.7 per cent in Q4 – with risks evenly balanced around this baseline path (Chart I.10 and Table I.3). For 2024-25, assuming a normal monsoon and no major exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate real GDP growth at 6.5 per cent, with quarterly growth rates in the range of 6.3-6.6 per cent.    There are upside and downside risks to this baseline growth path. The upside risks emanate from a stronger-than-expected rebound in contact-intensive services, some of which have still to catch up to their pre-pandemic levels; a more vigorous boost to private investment from government’s capex push and healthier corporate balance sheets; more resilient global growth; and an early resolution of the geopolitical conflict. On the contrary, an escalation in geopolitical tensions, a further hardening of international crude oil, food and commodity prices, a sharper loss of momentum in global trade and demand, and frequent weather-related disturbances due to climate change pose downside risks to the baseline growth path. The projections of growth and inflation presented in this chapter are contingent upon the baseline assumptions set out in Table I.2. These assumptions remain subject to a range of uncertainties as elucidated earlier. Against this backdrop, this section explores plausible alternative scenarios to assess the balance of risks to the baseline projections. (i) Global Growth Uncertainties Global growth is slowing after a relatively strong outturn in H1:2023. There are downside risks to the baseline assumption from the elevated inflation trajectory in major economies, an extended phase of tight financial conditions from expectations of interest rates remaining elevated over a prolonged horizon, protracted geopolitical hostilities, supply chain fragmentations and substantive slowdown in China. Global inflation, though moderating, remains hostage to the risk of a wage-price spiral owing to tight labour markets in several AEs. There is a strong common global component in headline and core inflation across countries ( Box I.2), which could exert sustained upward inflation pressures and necessitate further monetary tightening which, in turn, could weigh down on output. In such a scenario, if global growth is 100 bps lower than the baseline, domestic growth and inflation could be around 30 bps and 15 bps, respectively, below their baseline trajectories. Conversely, if inflation in major economies retreats faster than anticipated, geopolitical tensions ebb and the stimuli measures are able to reverse the slowdown in the Chinese economy quickly, global growth may remain resilient. In this scenario, if global growth is higher by 50 bps, domestic growth and inflation could edge higher by around 15 bps and 7 bps, respectively (Charts I.11a and I.12a).

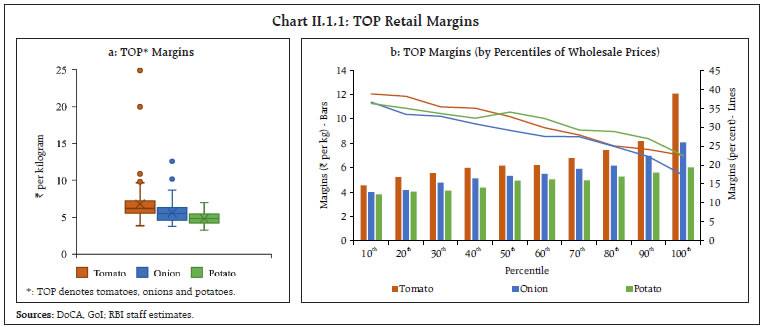

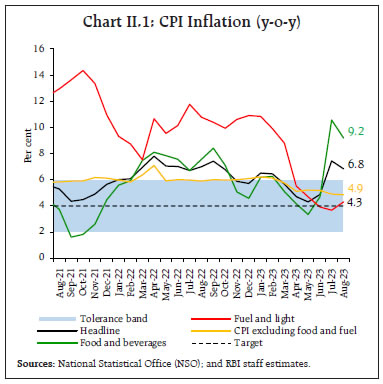

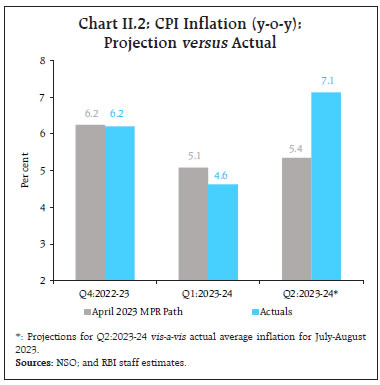

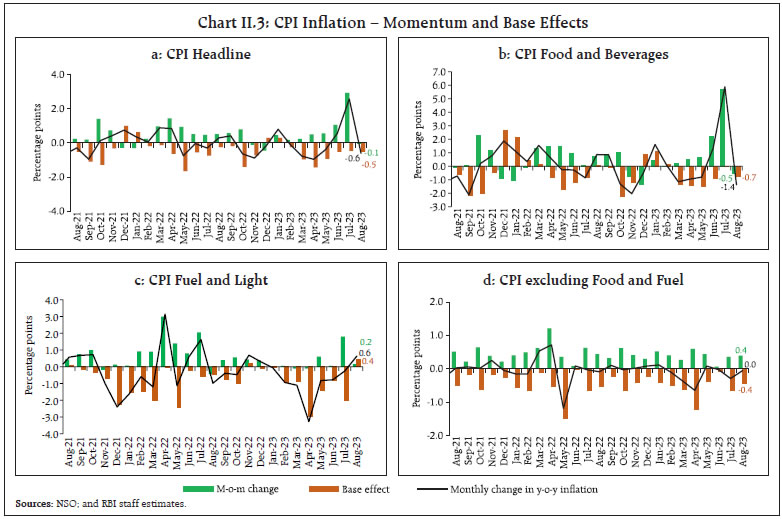

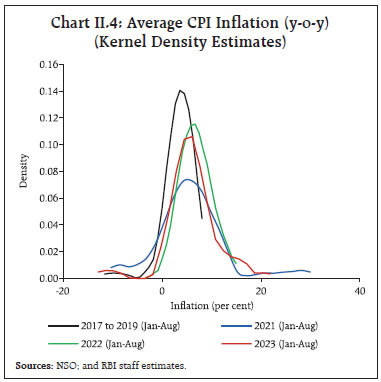

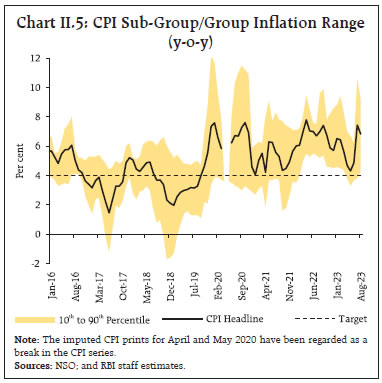

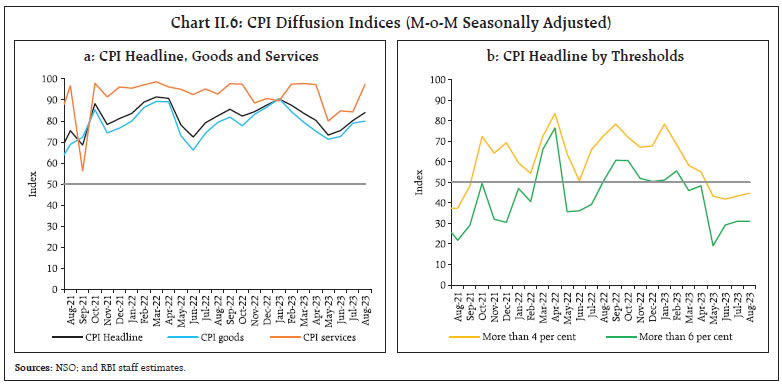

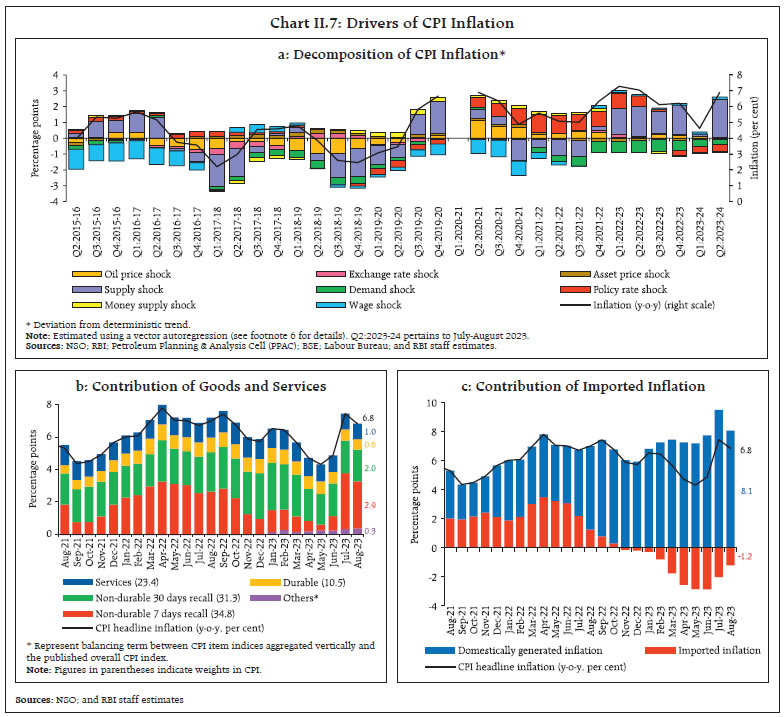

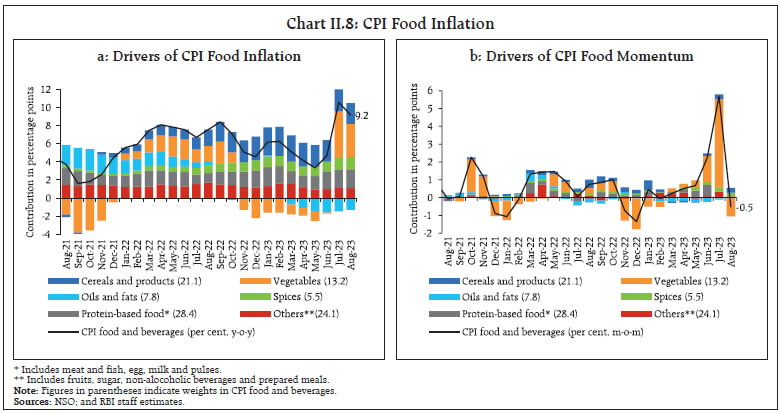

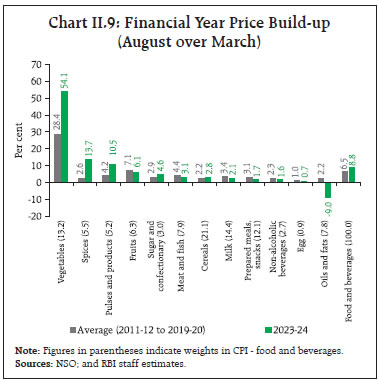

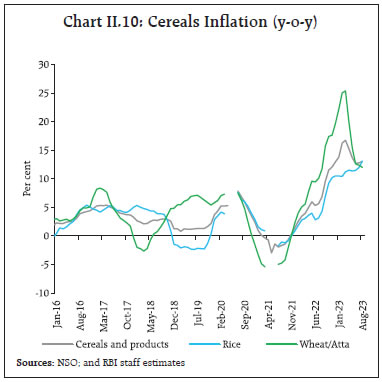

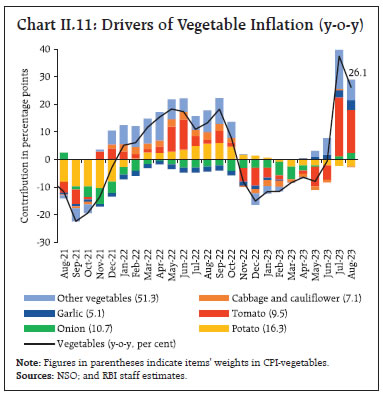

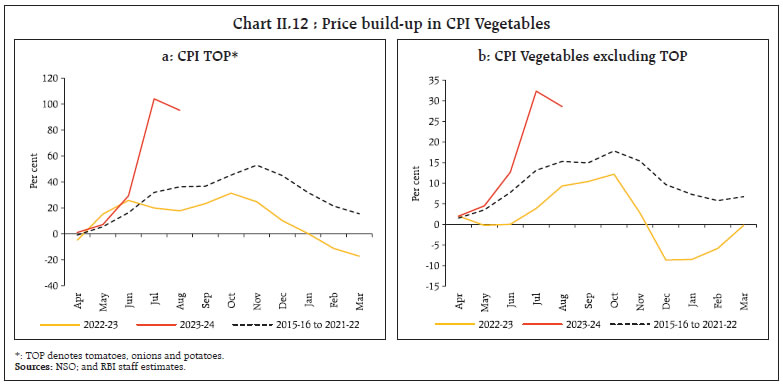

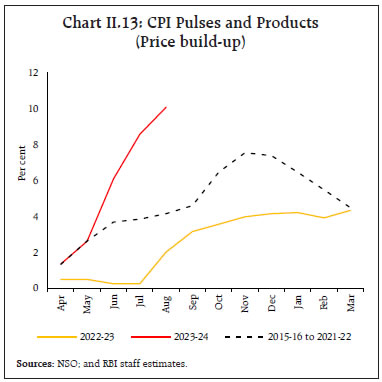

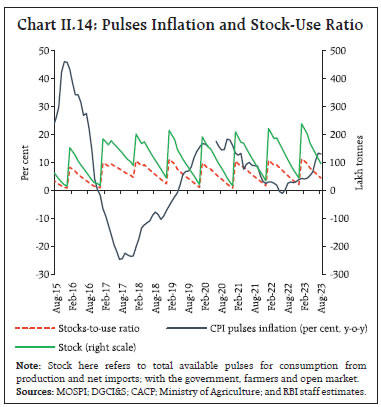

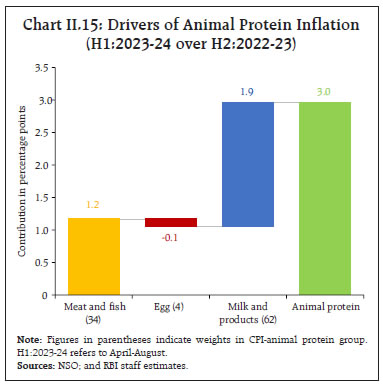

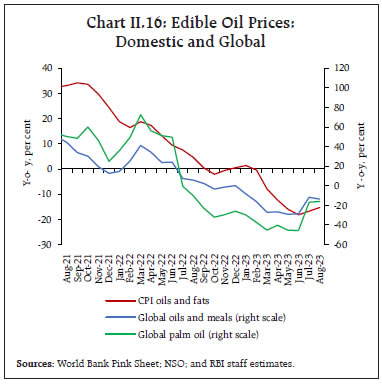

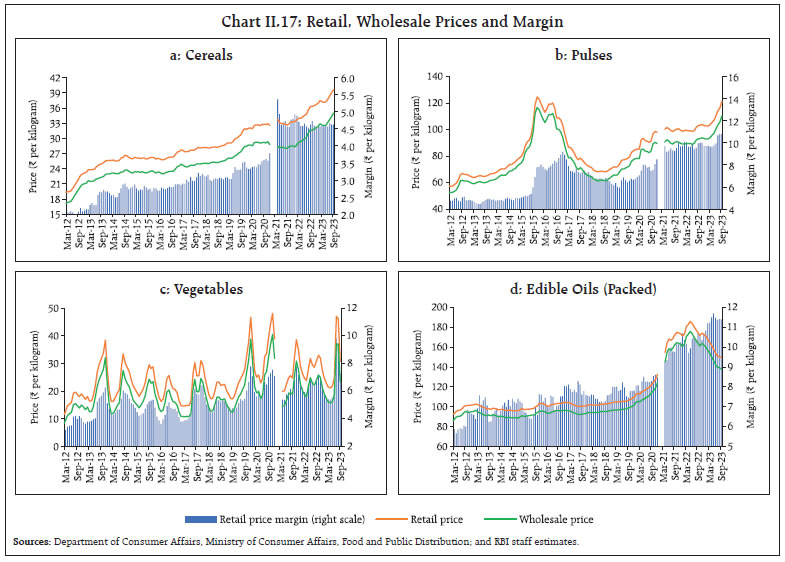

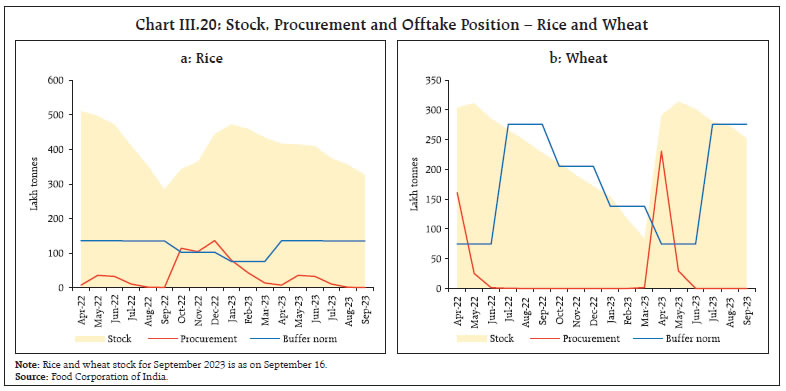

(ii) International Crude Oil Prices Global crude oil prices have remained highly volatile over the past six months. An escalation of geopolitical hostilities and further production cuts by OPEC plus amidst strong demand pose upside risks to global crude prices. Assuming crude oil price to be 10 per cent above the baseline, domestic inflation and growth could be higher by 30 bps and weaker by around 15 bps, respectively. Conversely, a de-escalation of geopolitical tensions, improved supply from non-OPEC producers and alternative energy sources, and a further weakening of global demand owing to aggressive monetary policy actions by central banks may pull down crude oil prices. If crude oil prices fall by 10 per cent relative to the baseline and assuming their full pass-through to domestic product prices, inflation could ease by around 30 bps with a boost of 15 bps to growth ( Charts I.11a and I.12a).  (iii) Exchange Rate The INR has fluctuated in both directions against the US dollar over the past six months. Looking ahead, the ‘higher for longer’ interest rate scenario in the US and other AEs could keep risk aversion towards EME assets elevated and impinge upon capital flows. Global foreign direct investment flows are also slowing. Crude oil and other commodity prices could harden over the baseline. Should the INR depreciate by 5 per cent over the baseline, inflation could edge up by around 35 bps while GDP growth could be higher by around 25 bps through stimulating exports. On the other hand, the Indian economy remains the bright spot in the global economy and is pivotal to the global outlook. These developments, along with a strengthening of domestic macroeconomic fundamentals, could enhance India’s attraction as a destination for foreign investors. In this scenario, if the INR appreciates by 5 per cent relative to the baseline, inflation and GDP growth could moderate by around 35 bps and 25 bps, respectively (Charts I.11b and I.12b). (iv) Food Inflation Food inflation exhibited sizeable volatility in H1:2023-24, driven by large shocks to vegetable prices due to extreme weather events which are occurring more frequently and with more force. The risk of El Niño has materialised, resulting in the driest August on record, and water reservoir levels have dipped below the decadal average levels. These developments impart a heightened uncertainty to the kharif and the ensuing rabi crops. The global food price outlook is also subject to significant upside risks from the historically unprecedented heatwave sweeping across the globe. All these developments could impart sizeable upside to the domestic food inflation trajectory and could raise headline inflation by around 100 bps over the baseline. On the other hand, given the robust kharif sowing, improved irrigation facilities, the IOD turning positive, ample foodgrains buffer stocks and effective supply management could help ease food inflationary pressures and pull headline inflation 50 bps below the baseline (Charts I.11b and I.12b). Economic activity in India is expected to remain backed up by strong macroeconomic fundamentals. Large supply shocks are, however, leading to recurrent bouts of inflation and pose challenge to the overall outlook. The uneven south-west monsoon, El Niño formation and the volatile global food prices outlook impart significant uncertainty to the outlook of food and headline inflation, even as core inflation is showing some signs of easing. Thus, price developments warrant heightened vigil and monetary policy remains focused on aligning inflation with the target. A firm anchoring of inflationary expectations can pave the path for sustained growth in the medium-term. Geopolitical hostilities, stubborn global inflation, volatile global financial markets and energy prices, and climate shocks are the key risks to the growth and the inflation outlook. __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Reserve Bank’s inflation expectations survey of households is being conducted in 19 cities since March 2021 (18 cities in the previous rounds) and the results of the September 2023 round are based on responses from 6066 households. 2 The results of the July-September 2023 round of the industrial outlook survey are based on responses from 1223 companies. 3 Based on 581 services companies and 104 infrastructure firms polled in the July-September 2023 round of the services and infrastructure outlook survey. 4 41 panellists participated in the September 2023 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey of professional forecasters. 5 Joice John, Deepak Kumar, Asish Thomas George, Pratik Mitra, Muneesh Kapur and Michael Debabrata Patra (2023), “A Recalibrated Quarterly Projection Model (QPM 2.0) for India”, Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, February, Volume LXXVII(2), pp.59-77. 6 The polarity score is a ratio between -1 and 1. A score in the range of -1 to -0.5 typically indicates negative sentiment, between -0.5 and 0.5 neutral sentiment, and 0.5 to 1 positive sentiment. 7 The subjectivity score captures the number of words that carry sentiment as a proportion of total number of words. 8 Complex words are words with three or more syllables, and that are not proper nouns. 9 This is in line with literature whereby central bank monetary policy press documents are generally observed to have FK and FOG scores in the range of 12-18 years and 17-23 years, respectively. 10 The Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey is being conducted in 19 cities since March 2021 (13 cities in the previous rounds) and the results of the September 2023 round are based on responses from 6,077 respondents. 11 The sample AE countries are: Canada, Czech Republic, European Union, Israel, Japan, Norway, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, United Kingdom and United States. The sample EMEs are: Brazil, Colombia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Romania, South Africa and Thailand. 12 Based on 36-month moving average. Headline inflation has been undergoing considerable volatility, breaching the upper tolerance band of 6 per cent in July-August, due to repeated supply side shocks even as core inflation has been moderating. Industrial and farm input price pressures have eased while nominal rural wage growth has been firming up. Going forward, the inflation trajectory will be shaped by weather conditions and the evolution of global food and crude oil prices. Since the April 2023 MPR, consumer price index (CPI) headline inflation 1 has seen considerable volatility, moving in a wide range of 4.3 per cent to 7.4 per cent during February-August 2023. It initially moderated from 6.4 per cent in February 2023 to 4.3 per cent in May 2023. These gains were reversed from June on accentuation of food price pressures, and headline inflation surged to 7.4 per cent in July. In August, the onset of vegetable price correction softened it to 6.8 per cent. Core inflation (CPI excluding food and fuel) 2 has eased between February and August 2023 by 1.3 percentage points (Chart II.1).  The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and the underlying reasons thereof. The April 2023 MPR had projected inflation at 5.1 per cent for Q1:2023-24 and 5.4 per cent for Q2 (Chart II.2). In Q1, actual inflation at 4.6 per cent trailed projection by 50 basis points (bps), as food inflation turned out to be lower than anticipated due to a muted seasonal pick-up in vegetables prices during April-May and a sustained decline in prices of edible oil. In Q2 (July-August), on the other hand, the actual outcome at 7.1 per cent exceeded the projection by 170 bps due to a steep rise in vegetables prices, particularly those of tomatoes. In fact, vegetable prices and even overall food prices registered the highest month over month increase in the current CPI series (2012=100) in July, resulting in the projection error. During H1:2023-24, headline inflation movements benefited from strong favourable base effects 3 averaging one percentage point during March-May 2023, which pulled down headline inflation from 6.4 per cent in February to 4.3 per cent in May. Thereafter, a pick-up in the price momentum, alongside waning base effects led to an uptick in headline inflation to 4.9 per cent in June. In July, an all-time high momentum in food prices (5.7 per cent) and strong momentum in fuel (1.8 per cent) led to a record monthly momentum of 290 bps in headline inflation, pushing the y-o-y inflation to 7.4 per cent. In August, a decline in momentum, along with favourable base effects helped soften inflation to 6.8 per cent (Chart II.3).  The CPI inflation distribution during 2023 vis-à-vis the earlier years was marked by a significant increase in standard deviation, mirroring the large variation in inflation rates, even as the mean of the distribution fell to 5.8 per cent in 2023 (January-August) from 6.8 per cent in the corresponding period of 2022 (Chart II.4). Inflation variability increased substantially across the CPI sub-groups during July-August 2023 following the vegetable price shock (Chart II.5).   Diffusion indices (DIs) 4 softened during March-May 2023 as the fall in inflation was accompanied by a narrowing of the spread of price increases across the CPI basket, driven largely by prices of goods ( Chart II.6a). Moreover, unlike a year ago when price increases in excess of 4 per cent on a seasonally adjusted annualised rate (saar) basis were the norm across the CPI basket, there was a marked slowdown in the magnitude of price increases since March 2023 as measured by threshold DI 5 (Chart II.6b). During June-August, the diffusion of price increases broadened across goods and services, though a majority of items registered price increases of less than 4 per cent on a saar basis.   A historical decomposition of inflation using a vector autoregression (VAR) 6 model indicates that the moderation in inflation in Q1:2023-24 came from a waning of supply side shocks as also from the disinflation engendered by the transmission of past monetary policy actions. Of the 270 bps moderation in headline inflation (from 7.3 per cent in April-June 2022 to 4.6 per cent in April-June 2023), 130 bps was due to monetary policy tightening (a cumulative increase of 250 bps in the policy rate) and the remaining 140 bps was due to the waning of supply shocks. The jump in inflation in Q2:2023-24 (up to August) was entirely due to adverse supply shocks even though the restraining effects of cumulative monetary tightening were still playing out (Chart II.7a). Goods inflation (with a weight of 76.6 per cent in overall CPI) contributed around three-fourths of headline inflation during March-May 2023 and services (with a weight of 23.4 per cent) the remaining one-fourth. By August, the contribution of goods to overall inflation rose to 81 per cent (Chart II.7b). Within goods, perishable items (non-durable with a 7-day recall 7 ), particularly fruits, vegetables, and other food items such as eggs, meat, fish and milk were the main drivers. The contribution of semi-perishable items (non-durable goods with a 30-day recall) such as petroleum products, household items (particularly, washing soaps and powders), personal care items (like toiletries) and medicines declined from 46 per cent in March 2023 to 29 per cent in August. Similarly, the contribution of durables (goods with a 365-day recall) like clothing and footwear items, motor cycle/scooter, and household goods (furniture and electronic items) to overall inflation declined to 9 per cent in August 2023 from 14 per cent in March 2023. With the gradual moderation in the international commodity prices since September 2022, the contribution of imported components 8 to headline inflation turned negative towards the end of 2022, driven down by the y-o-y fall in the prices of edible oils, energy, electronic goods parts, and polymer (Chart II.7c). With the pick-up in the global commodity prices in July 2023, primarily driven by energy prices, the negative contribution of imported inflation lessened to (-)1.2 per cent in August.  Food Group Food and beverages (weight of 45.9 per cent in the CPI basket) inflation, which was muted in Q1:2023-24 at 4.1 per cent, increased sharply to 10.6 per cent in July, led by the steep increase in vegetables prices. With corrections in the vegetable prices on fresh crop arrivals, food inflation moderated to 9.2 per cent in August. CPI food inflation excluding vegetables, however, increased to 6.4 per cent during July-August from 5.4 per cent in Q1 as inflation in respect of cereals, pulses, and spices remained elevated. Inflation in oils and fats remained in deflation, partially offsetting the upside pressures across other major sub-groups in the food basket (Chart II.8). The sharp increase in vegetables prices in July was due to supply disruptions caused by heavy rainfall and floods in the northern parts of the country and lower production due to pest attacks on crops in Karnataka and Maharashtra. Uneven rainfall distribution, delayed sowing of rice, and lower stock of wheat along with lower production of spices contributed to the hardening of prices in cereals and spices.  The overall food price build-up in 2023-24 was higher than historical patterns, driven by vegetables, spices, pulses, sugar and cereals. The price build-ups in six of the twelve sub-groups – fruits; meat and fish; milk; prepared meals; non-alcoholic beverages; and eggs – were lower than their long-term averages (Chart II.9).  Inflation in cereals (weight of 9.7 per cent in the CPI and 21.1 per cent in the food and beverages group) remained elevated during April-August 2023 (Chart II.10). After a decline between March and May 2023, wheat prices surged as rabi wheat crop was impacted by unseasonal rains. Rice prices increased sharply as uneven rainfall distribution led to delay in kharif sowing. However, sowing eventually picked up (1.9 per cent over last year as on September 29, 2023) on account of revival in monsoon. As part of the supply side interventions to improve domestic supply and ease price pressures, the Government (i) announced to release a cumulative 5 million tonnes of wheat and 2.5 million tonnes of rice in the open market in a phased manner; (ii) imposed an export duty on parboiled rice, restricted exports of non-basmati rice and levied stock limits on wheat; and (iii) stopped the diversion of subsidised rice to distilleries for ethanol production.  After being in deflation during November 2022-June 2023, prices of vegetables (weight of 6.0 per cent in the CPI and 13.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) increased sharply to record a y-o-y inflation of 37.4 per cent in July 2023, due to weather related crop damage and disrupted supply chains in North India. A pick-up in market arrivals and improved supply conditions caused inflation in this category to moderate to 26.1 per cent in August (Chart II.11). Among key vegetables, tomato prices, on a y-o-y basis, surged by 202.1 per cent in July. A revival in market arrivals moderated tomato price inflation to 180.3 per cent in August 2023. Potato prices have remained in deflation since February 2023 on account of higher production last year (an increase of 6.3 per cent in 2022-23 as per 1st advance estimates (AE) over 2021-22). Onion prices, which were in deflation during September 2021-May 2023, recorded an inflation of 23.2 per cent in August 2023 on lower production [(-) 2.1 per cent in 2022-23 1st AE over 2021-22] as well as low quality of the rabi crop reducing shelf life. Overall, the record price increase in July propelled the tomato, onion, and potato (TOP) group price build-up (July-August over March) to one of the largest ever seen in the current CPI series ( Chart II.12a). Vegetables excluding TOP – ginger, garlic, cauliflower, cabbage, brinjal and green chillies – also witnessed high price pressures in July due to rain induced supply disturbances. The price build-up in non-TOP vegetables during 2023-24 (up to August) was unprecedented by historical patterns and contributed substantially to the spike in vegetables inflation ( Chart II.12b). With the improving supply situation, the prices of vegetables excluding TOP corrected in August. To rein in prices, the government announced sale of tomatoes at concessional rates at several markets in the country during July-August 2023 and release of onions (under the Price Stabilisation Fund) at subsidised rates from the buffer stocks.  Inflation in fruits (weight of 2.9 per cent in the CPI and 6.3 per cent within the food and beverages group) has moderated since April 2023 on the back of higher production (0.2 per cent as per 2022-23 1st AE over 2021-22). However, there was an uptick in inflation in July-August 2023, primarily driven by a rise in apple prices to 21.3 per cent (y-o-y) in August from an average of 5.1 per cent in Q1:2023-24 as floods in Himachal Pradesh damaged apple plantations and led to supply disruptions. Mango prices remained in deflation since April 2023, while banana price inflation moderated from 21.8 per cent in March 2023 to 2.2 per cent in August on the back of comfortable production.  Inflation in pulses (weight of 2.4 per cent in the CPI and 5.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) increased gradually, with a substantial price build-up from April leading to a print of 13.0 per cent in August 2023. The uptick came from lower production and deficient kharif sowing. As per the 3rd AE of 2022-23, the kharif production of pulses was lower than the final estimates for 2021-22, particularly for tur and urad ((-) 18.7 per cent and (-) 3.2 per cent, respectively). Owing to the downward revision, the pulses stock-to-use (STU) ratio has also fallen. Furthermore, deficient kharif sowing of (-) 4.9 per cent in tur, (-) 1.3 per cent in urad and (-) 6.0 per cent in moong (as on September 29, 2023) also added to price pressures (Chart II.13 and Chart II.14). To contain price pressures and improve domestic availability, the government (i) imposed stock limits on tur and urad on June 2, 2023, which will be effective till December 31, 2023; (ii) removed procurement ceilings of 40 per cent for tur, urad and masoor under the Price Support Scheme (PSS) for 2023-24 to encourage higher sowing acreage; and (iii) decided to release tur from the national buffer in a calibrated manner. Prices of animal-based protein items increased sharply in H1:2023-24 (April-August), driven by milk and products (weight of 6.6 per cent in the CPI and 14.4 per cent within the food and beverages group) ( Chart II.15) which averaged 8.5 per cent during April-August 2023 as major milk co-operatives like Amul raised retail prices by ₹2-3 per litre twice from February 2023, citing high input costs. Prices of eggs, meat and fish eased in July-August 2023 due to low seasonal demand.    Prices of oils and fats (weight of 3.6 per cent in the CPI and 7.8 per cent within the food and beverages group) were in deflation during April-August 2023, reflecting falling international prices and higher domestic production of oilseeds (8.0 per cent as per 3rd AE of 2022-23 over 2021-22) (Chart II.16). As part of price stabilisation measures, the government reduced the basic import duty on refined soyabean oil and refined sunflower oil from 17.5 per cent to 12.5 per cent (on June 15, 2023, effective till March 31, 2024) and exempted imports of crude soybean oil and crude sunflower oil from basic customs duty and agriculture infrastructure and development cess (AIDC) till June 30, 2023 for tariff rate quota (TRQ) holders to ensure domestic availability and affordable prices. Ghee and butter price inflation remained at elevated levels, reflecting the pass-through of higher milk prices.  Inflation in prices of sugar and confectionery (weight of 1.4 per cent in the CPI and 3.0 per cent in the food and beverages group) increased gradually during April-August 2023, reflecting reduced production in 2022-23 season from the earlier estimate and the pickup in demand during summer months. Among other food items, inflation in prices of spices witnessed a sustained rise, averaging 19.9 per cent during April-August 2023 and driven mainly by jeera (cumin) and dry chillies due to subdued production for the second consecutive year in 2022-23 on account of poor weather conditions and crop substitution in major producing states. On a y-o-y basis, jeera recorded the highest increase in prices at 118.2 per cent in August; inflation in prices of dry chillies was also elevated averaging 24.2 per cent during April-August 2023. Inflation in prepared meals moderated gradually, reflecting the waning of the pass-through of past increases in input costs such as edible oils, LPG, and transport costs. Retail Margins Retail price margins – the difference of retail and wholesale prices 9 – remained broadly unchanged for cereals. Pulses price margins underwent an increase during July-September 2023, driven by retail prices of tur, urad, moong and gram. Price margins in edible oils (groundnut, soyabean, sunflower and mustard oil) remained elevated and steady even as wholesale prices registered a downward movement. Margins in vegetables prices picked up significantly during June-August 2023, owing to the sharp increase in retail margins in tomatoes (Chart II.17). With an easing of tomato prices starting the third week of August 2023, retail margins for vegetables softened in September 2023. The sensitivity of margins to wholesale prices in the TOP group is the highest for tomatoes and the lowest for potatoes (Box II.1).

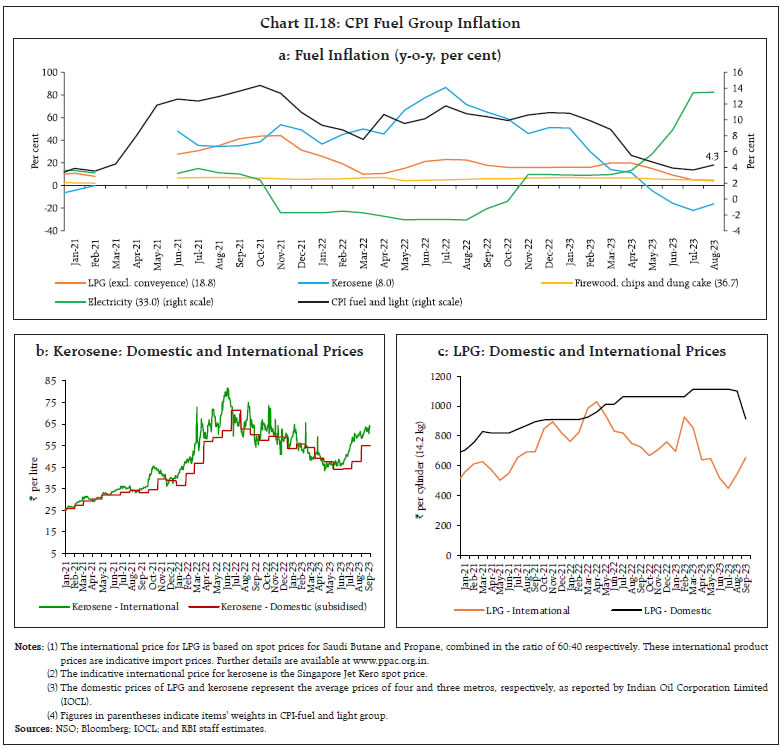

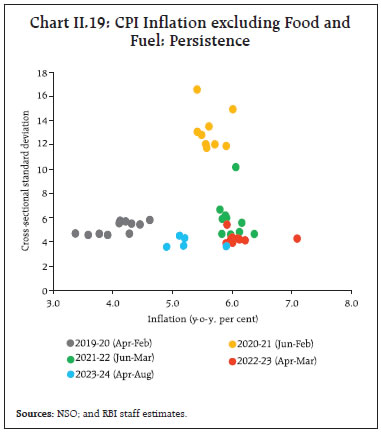

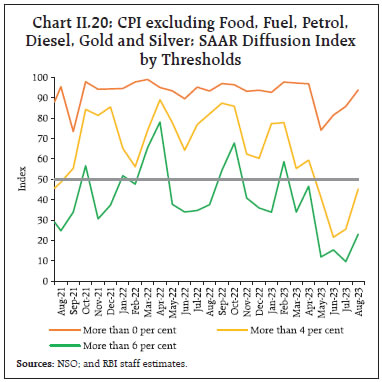

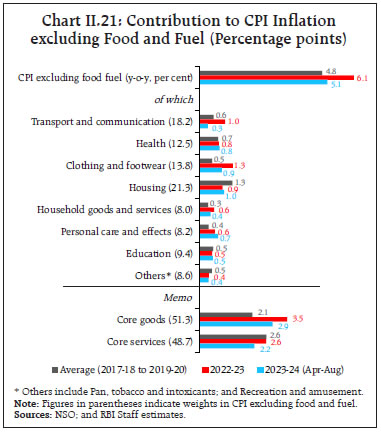

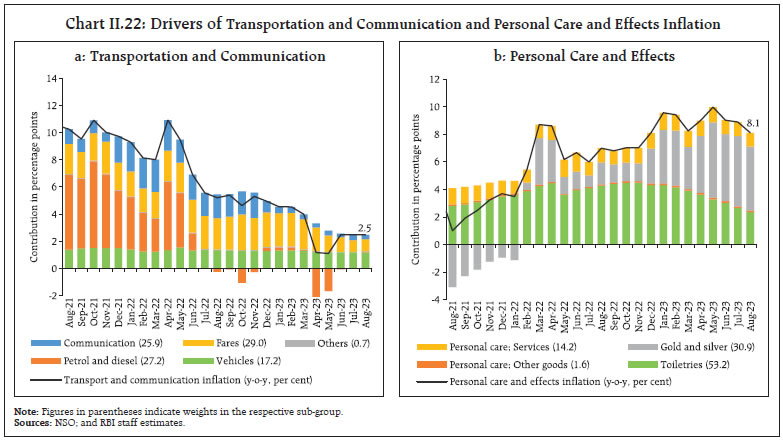

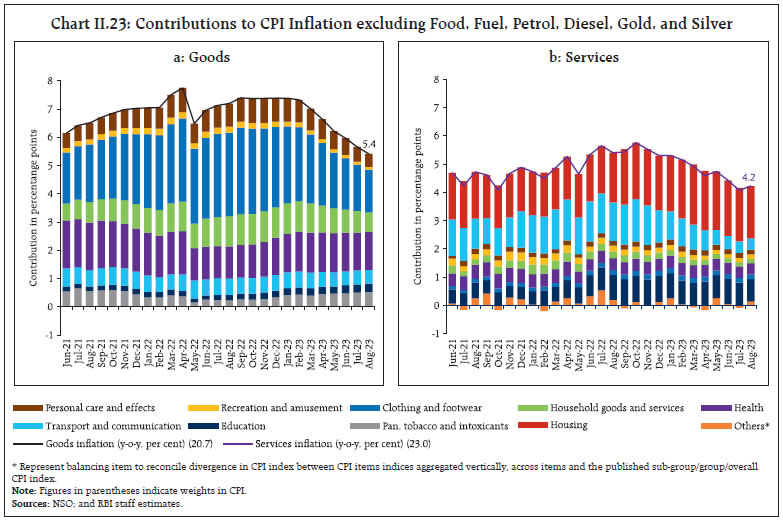

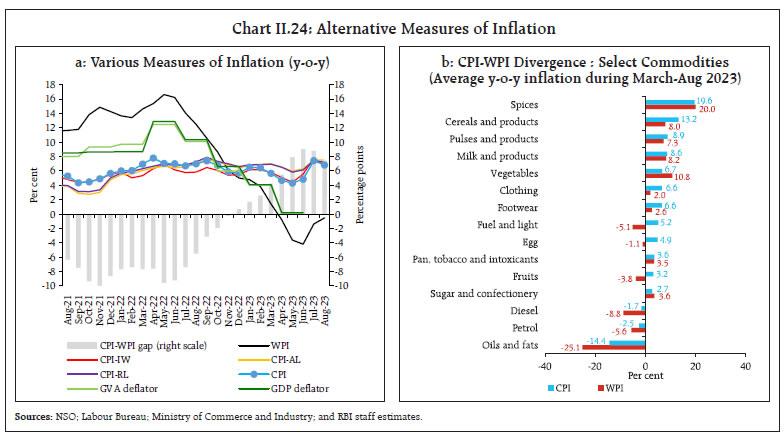

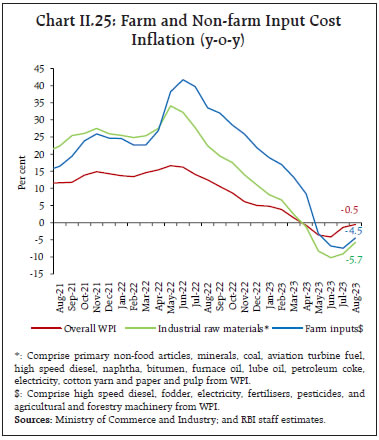

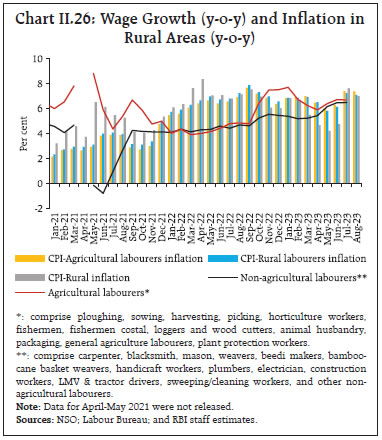

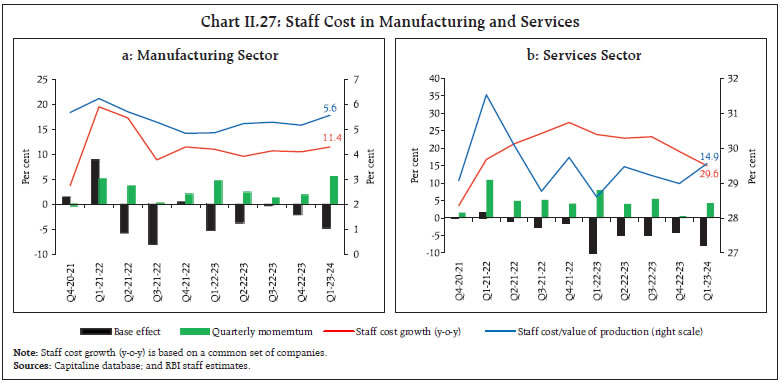

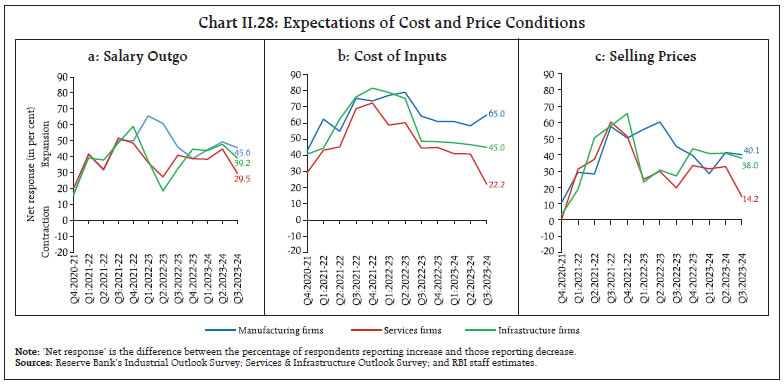

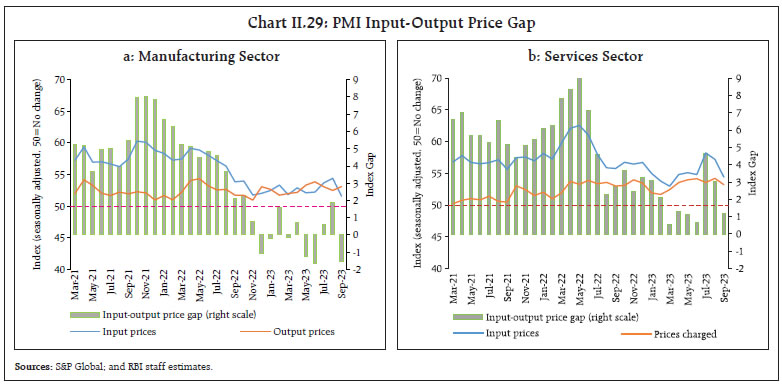

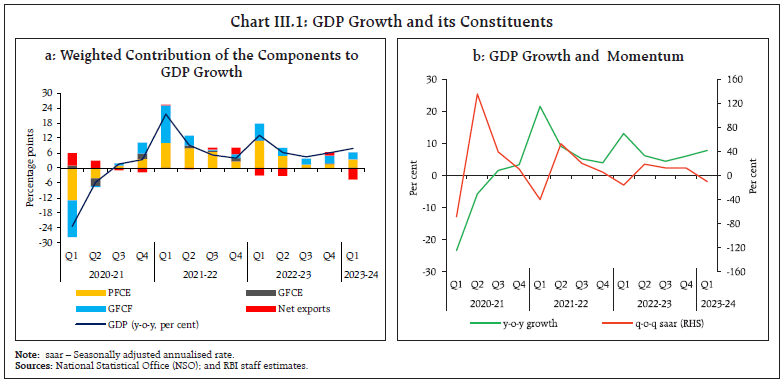

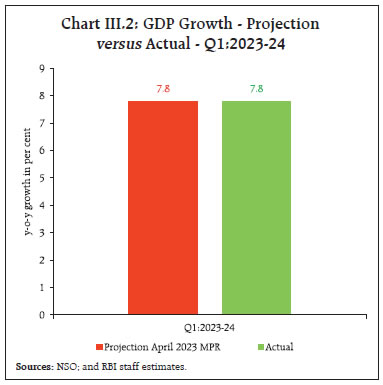

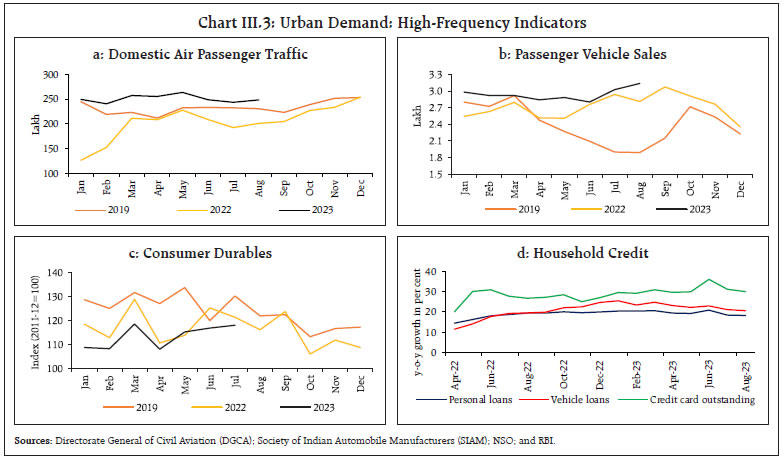

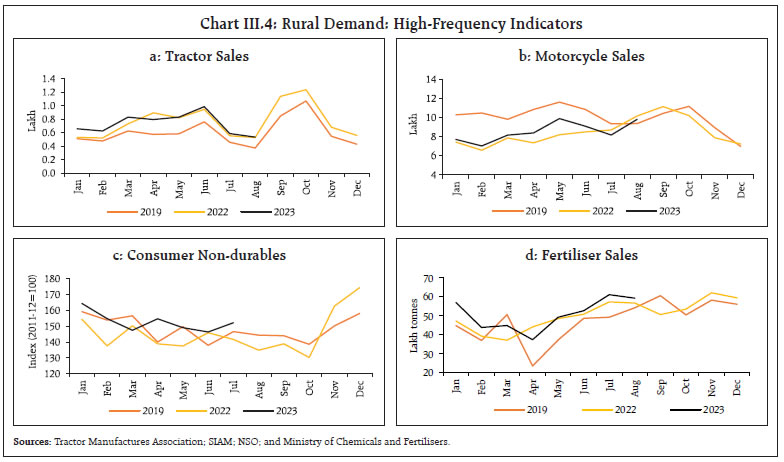

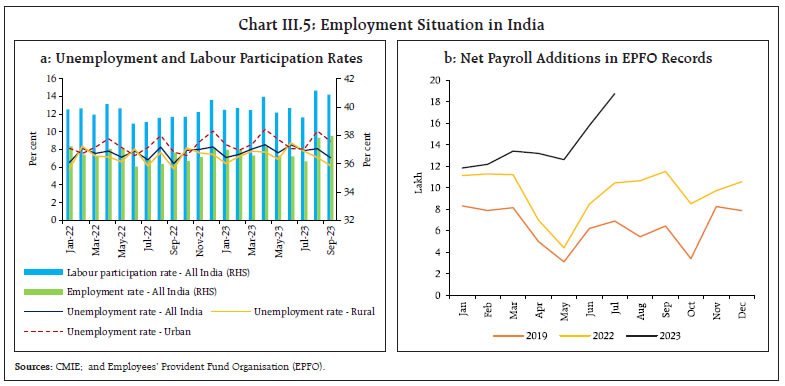

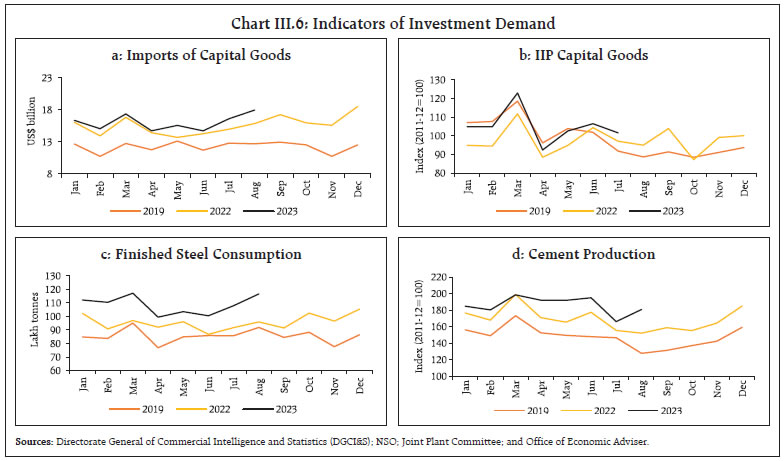

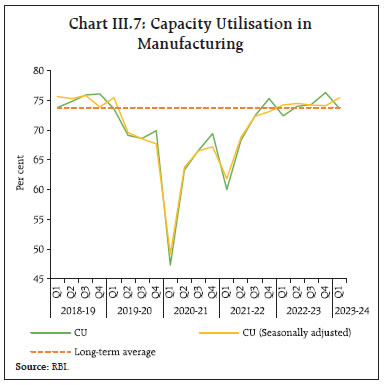

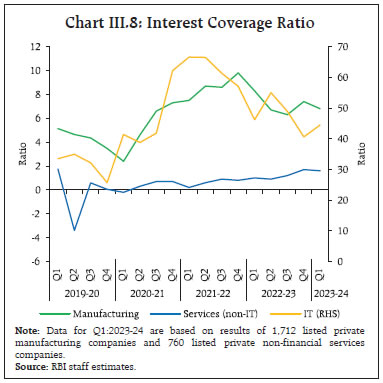

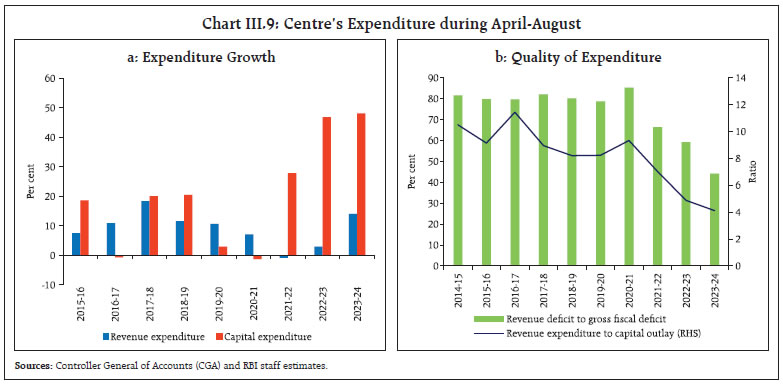

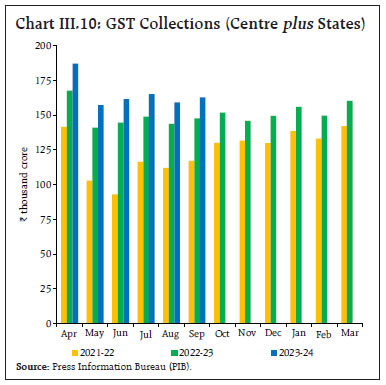

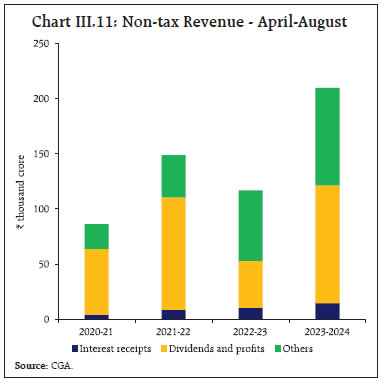

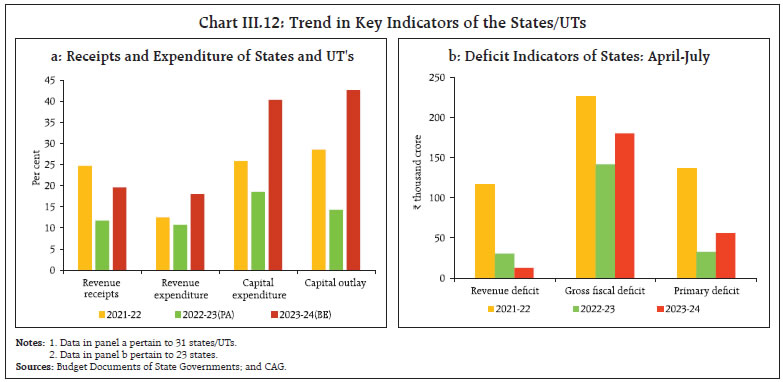

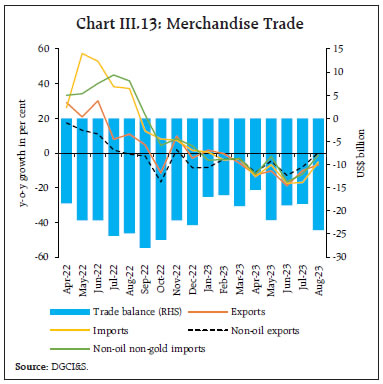

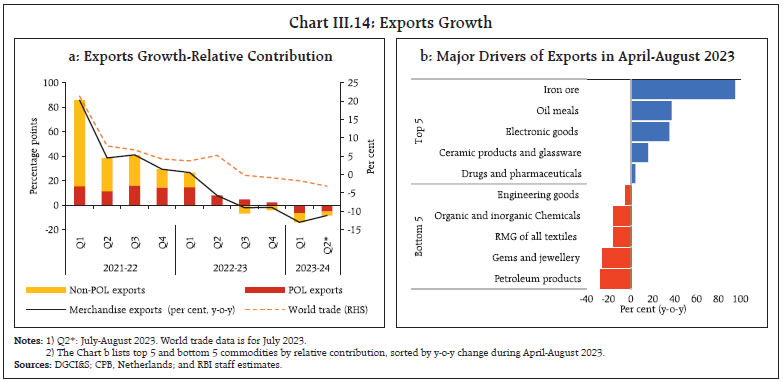

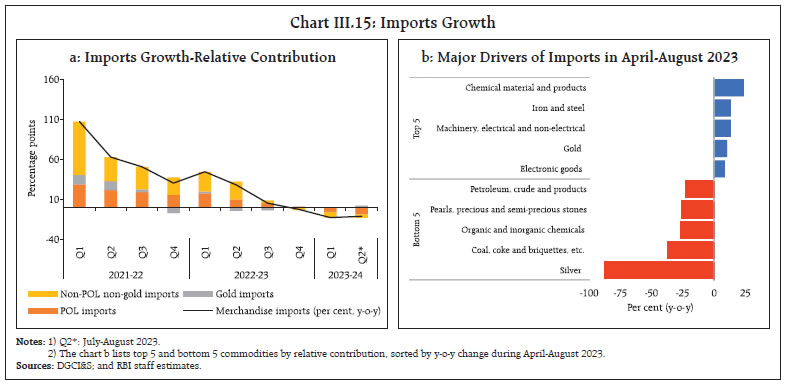

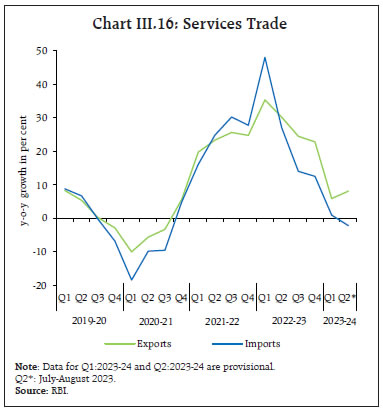

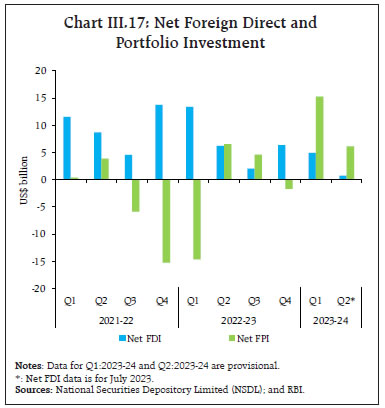

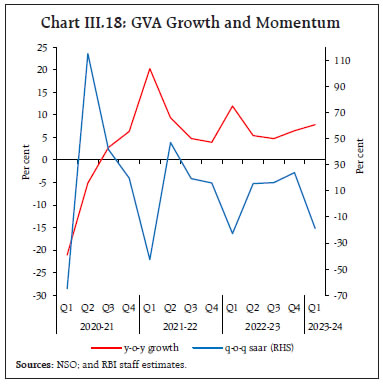

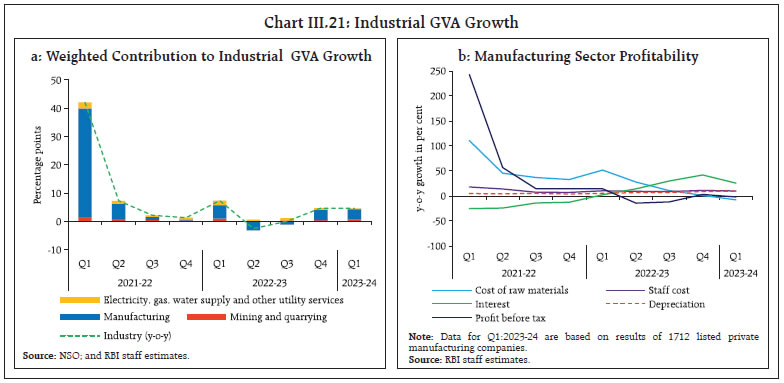

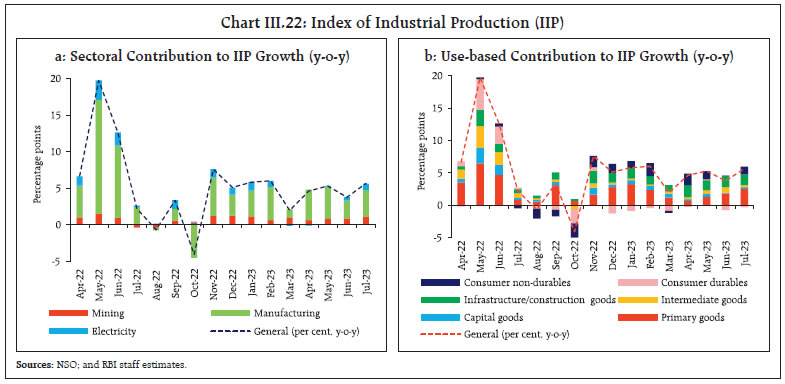

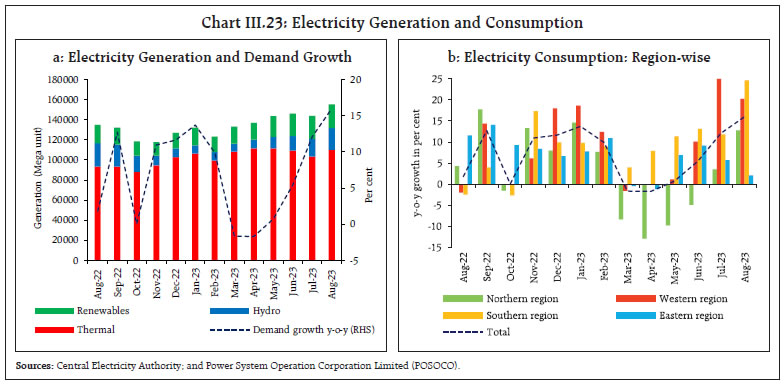

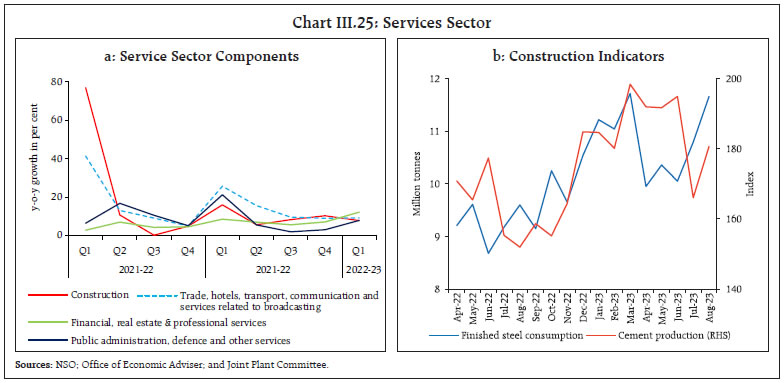

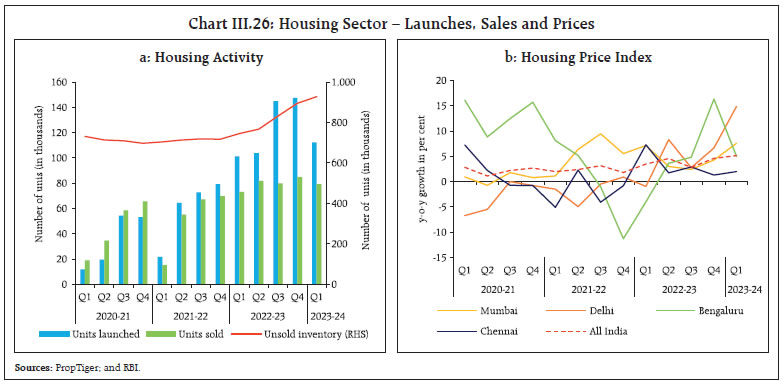

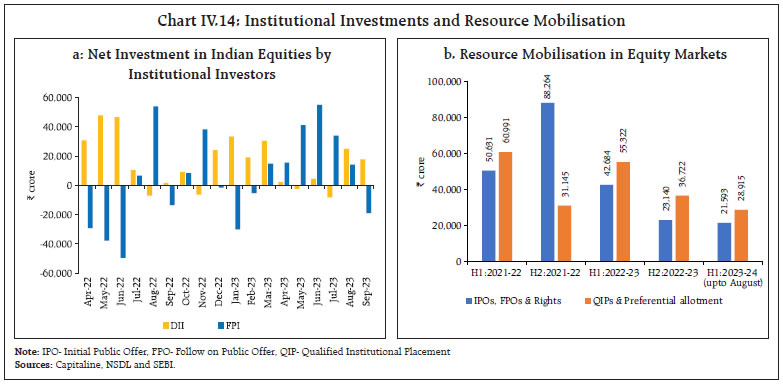

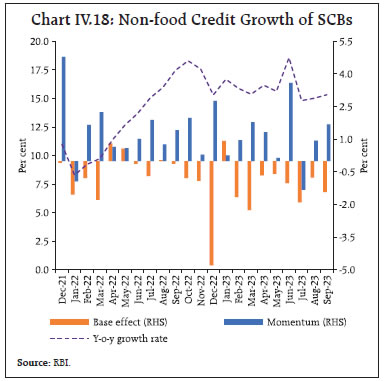

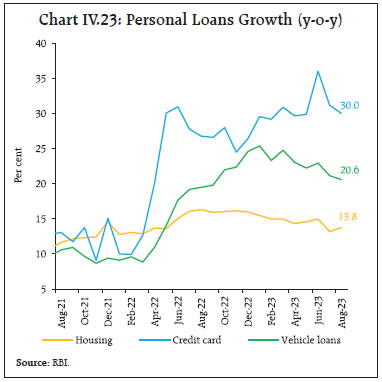

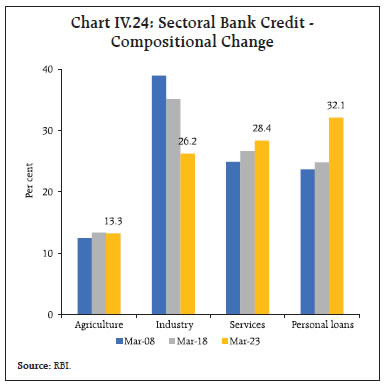

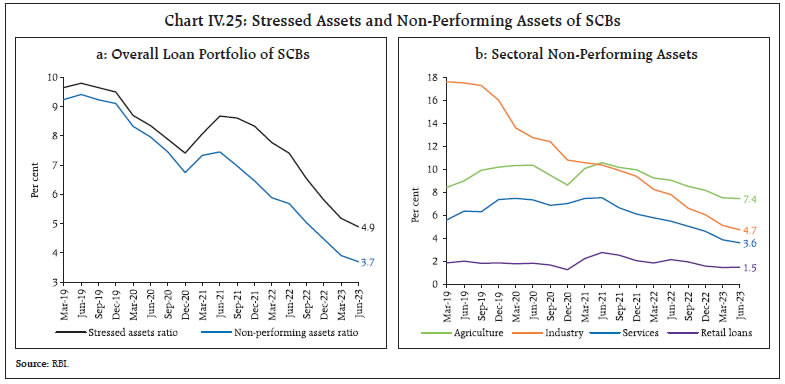

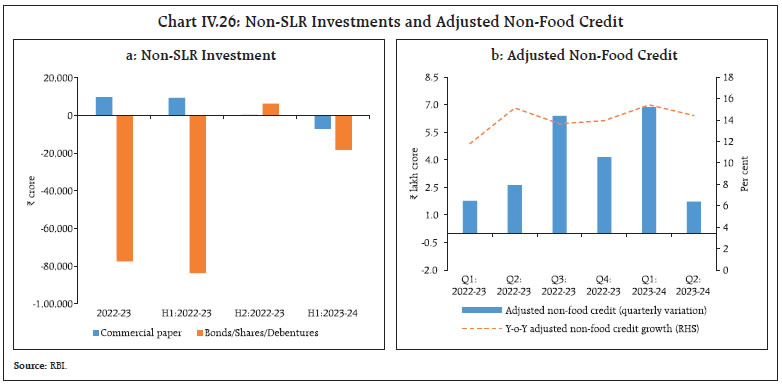

Fuel Group CPI fuel inflation moderated from 8.8 per cent in March 2023 to 3.7 per cent in July on account of softening of kerosene and domestic liquified petroleum gas (LPG) prices, before it rose to 4.3 per cent in August. With domestic prices of LPG kept unchanged between March and late August, the moderation came from favourable base effects. Kerosene prices remained in deflation during May-August 2023 on a y-o-y basis as domestic prices fell in line with international prices, aided by favourable base effects. Firewood and chips prices also moderated during March-August. Electricity prices, on the other hand, registered a substantial increase from May, leading to a record inflation (y-o-y) of around 13.5 per cent in August (Chart II.18).  Core (CPI excluding Food and Fuel) Core inflation (CPI excluding food and fuel) eased from 6.1 per cent in February 2023 to 4.9 per cent during July-August. Exclusion-based measures of underlying inflation, which remove volatile items such as petrol, diesel, gold, and silver also witnessed moderation in the range of 130-140 bps during this period (Table II.1). Reversing the generalisation and persistence observed during 2022-23, core inflation softened during 2023-24 (April-August), along with a lower standard deviation (Chart II.19). During April-May 2023, threshold diffusion indices of core CPI items registering price increases of greater than 6 per cent (saar) as well that of 4 per cent (saar) moved into the contraction zone, indicating some abatement in the intensity of price pressures. During June-August, the diffusion index rebounded, but threshold core DIs for saar of greater than 4 per cent and 6 per cent remained in contraction ( Chart II.20).   During 2023-24 (April-August), the contribution of transportation and communication and clothing and footwear sub-groups registered a significant softening (Chart II.21).   The movement of petrol and diesel prices into deflation during Q1:2023-24, along with a softening in transportation fares and communication services, led to the sharp moderation in transportation and communication inflation. A firming up of gold and silver prices kept personal care and effects inflation and its contribution to core inflation elevated (Chart II.22). A decomposition of CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold, and silver inflation into its goods (with a weight of 20.7 per cent in the headline CPI) and services (weight of 23.0 per cent) components shows a softening in both the categories, but mainly led by goods. While core goods inflation moderated by 190 bps from 7.3 per cent in February 2023 to 5.4 per cent in August, services core inflation fell by around 90 bps to 4.2 per cent. The key drivers of the softening in goods inflation were clothing and footwear, household goods and personal care and effects (excluding gold and silver) (Chart II.23a). In the case of services, transportation fares (bus/tram/taxi fare, air fare) and communication services along with housing drove the moderation in inflation (Chart II.23b). Trimmed mean measures 11 also indicate a tempering of underlying inflation pressures, with weighted median inflation registering a decline of 140 bps between February and August 2023 (Table II.2).  Other Measures of Inflation Sectoral measures of CPI inflation for rural areas, i.e., CPI agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and rural labourers (CPI-RL) as also for industrial workers (CPI-IW) exceeded CPI headline inflation during March-June 2023 across most major groups. During July-August 2023, CPI-AL, CPI-RL, and CPI-IW edged up on higher food prices, in line with headline CPI. Wholesale price index (WPI) inflation, which was on a downward trajectory since October 2022, spiralled down into deflation in April-August, partly offset by higher vegetable prices in July, and fuel prices in August. The deflation in WPI pulled down the deflators for gross value added (GVA) and gross domestic product (GDP) in Q1:2023-24 (Chart II.24a). Overall, WPI inflation remained far below headline CPI inflation during March-August 2023, driven down by the fuel group – CPI contains transport fuel (petrol and diesel) prices of which have remained flat since August 2022, whereas WPI contains in addition to petrol and diesel, other fuels such as aviation turbine fuel, naphtha and furnace oil, all of which were by and large in deep deflation tracking international prices. In terms of other major groups, WPI inflation in food (particularly, cereals, milk and pulses), clothing and footwear, and pan, tobacco and intoxicants also ruled below the corresponding CPI groups/subgroups ( Chart II.24b).  Costs, as measured by WPI inflation in industrial raw materials and farm inputs, entered negative territory in April-May 2023 and remained muted since then, reflecting easing international commodity prices ( Chart II.25). Prices of industrial inputs such as high-speed diesel (HSD), naphtha, aviation turbine fuel (ATF), bitumen, furnace oil, and petroleum coke were in deflation during April-August, mirroring international crude oil price movements. The other contributory factors were non-food primary articles, particularly cotton and oilseeds, whose prices declined due to lower international prices and higher domestic production. Minerals price inflation, however, recorded an uptick during July-August 2023 driven by metals, particularly copper, on rising demand coupled with limited supply owing to constraints on new mining projects worldwide, increased taxes and environmental regulations. Farm input price inflation receded and turned negative from May 2023, driven by moderation in the prices of HSD and pesticides. Inflation in the price of WPI electricity – a key input in both industrial and farm inputs – declined sharply post April 2023 on account of a substantial decrease in coal prices coupled with favourable base effects.  Nominal rural wage growth accelerated to 6.6 per cent in July 2023 from 5.7 per cent in March 2023, with both agricultural and non-agricultural wages rising by more than 6 per cent ( Chart II.26). While the increase in agricultural wage growth was recorded primarily in ploughing, picking works, horticulture, watering and irrigation works, packaging, and plant protection works, that in non-agricultural wages were broad based across the rural sector. In the organised sector, staff cost growth (y-o-y) quickened in Q1:2023-24 in the manufacturing sector. In the services sector, staff cost growth (y-o-y) decelerated, notwithstanding positive momentum, due to a strong favourable base effect. The share of staff cost in the value of production rose in Q1 for both manufacturing and services sectors (Chart II.27).    As per the firms polled in the Reserve Bank’s enterprise surveys12, the pace of salary outgoes for the manufacturing, infrastructure and services sectors is expected to moderate in Q3:2023-24. Both input cost pressures and selling prices are expected to moderate in Q3 for services and infrastructure sectors. Manufacturing firms expect an uptick in input prices in Q3, with selling price growth to be marginally lower over the previous quarter (Chart II.28).  One year ahead business inflation expectations 13 of firms polled by the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, remained stable at 4.3 per cent during July-August 2023 with a moderate rise in cost pressures and improvement in sales expectations. As per manufacturing firms polled for the purchasing managers’ index (PMI), the pace of increase in input prices which quickened for the third successive month in August 2023, significantly retreated in September due to reduction in aluminium and oil prices. Higher raw materials, labour costs and increased demand led to an increase in output prices in July-September albeit at a slower pace than in May-June 2023. For services sector, the pace of increase in input prices started to fall in August-September 2023 converging towards its long-run average which also led to easing in prices charged to a six-month low. The input-output price gap reversed for manufacturing sector in September 2023 while it narrowed for services sector. (Chart II.29). Climate events imparted substantial volatility to the inflation trajectory in H1:2023-24. Going forward, the overall inflation and the food inflation trajectory will likely be shaped by the intensity of El Niño conditions, the impact of the skewed south-west monsoon and global energy and food prices. Pro-active supply side measures assume importance in mitigating the adverse impact of supply shocks in the short-run. Medium-term policies to encourage crop diversification, promote climate-resilient crops, improve storage conditions, facilitate value addition in agriculture and augment agricultural supply chains would make food prices more resilient to climate vagaries. Monetary policy would persevere in its efforts to maintain price stability, to progressively align inflation with the target rate, thereby securing the prerequisite conditions for a high and sustainable growth over the medium term. __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Headline inflation is measured by year-on-year (y-o-y) changes in the all-India consumer price index (CPI) produced by the National Statistical Office (NSO). 2 Core CPI, i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel is worked out by eliminating the groups ‘food and beverages’ and ‘fuel and light’ from the headline CPI. 3 A change in CPI year-on-year (y-o-y) inflation between any two months is the difference between the current month-on-month (m-o-m) change in the price index (momentum) and the m-o-m change in the price index 12 months earlier (base effect). For more details, see Box I.1 of the MPR, September 2014. 4 The CPI diffusion index, a measure of dispersion of price changes, categorises items in the CPI basket according to whether their prices have risen, remained stagnant or fallen over the previous month. The higher the reading above 50, the broader is the expansion or generalisation of price increases; the further is the reading below 50, the broader is the price decline across items. 5 Threshold diffusion indices capture the dispersion of price increases in CPI basket beyond the specified saar thresholds of 4 per cent and 6 per cent. 6 Historical decomposition estimates the contribution of each shock to the movements in inflation over the sample period (Q4:2010-11 to Q2:2023-24) based on a vector autoregression (VAR) with the following variables (represented as the vector Yt) – crude oil prices (US$ per barrel); exchange rate (INR per US$), asset price (BSE Sensex), CPI; the output gap; rural wages; the policy repo rate; and money supply (M3). All variables other than policy repo rate are y-o-y growth rates. The VAR can be written in reduced form as: Yt =c + A Yt-1 + et; where e t represents a vector of shocks. Using Wold decomposition, Yt can be represented as a function of its deterministic trend and sum of all the shocks et. This formulation facilitates decomposition of the deviation of inflation from its deterministic trend into the sum of contributions from various shocks. 7 The CPI weighting diagrams use the modified mixed reference period (MMRP) data based on the 2011-12 Consumer Expenditure Survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). Under MMRP, data are collected on expenditures incurred for frequently purchased items – edible oil, eggs, fish, meat, vegetables, fruits, spices, beverages, processed foods, pan, tobacco and intoxicants – during the last seven days; for clothing, bedding, footwear, education, medical (institutional), durable goods, during the last 365 days; and for all other food, fuel and light, miscellaneous goods and services including non-institutional medical services, rents and taxes, data relate to the last 30 days. 8 Global commodities that drive domestic prices include petroleum products, coal, electronic goods, gold, silver, chemical products, metal products, textiles, cereals, milk products, and vegetables oils – these together have a weight of 36.4 per cent in the CPI basket. 9 Item level retail and wholesale prices are aggregated at respective subgroups using item level CPI weights. Data for January-March 2021 have been excluded due to changes in price collection mechanism and item varieties by DCA. 10 Margins have been computed as the difference between retail and wholesale prices. Monthly retail and wholesale prices of TOP provided by Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA), GoI have been used for the analysis. 11 While exclusion-based measures drop a fixed set of volatile items (for example, food and fuel) in each period, trimmed measures exclude items located in the tails of the inflation distribution - items displaying changes more than the specified threshold in prices each month are excluded, and the items dropped differ from month to month. 12 Industrial Outlook Survey; and Services and Infrastructure Outlook Survey. 13 Based on the monthly Business Inflation Expectations Survey (BIES) of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. The survey polls a panel of business leaders primarily from the manufacturing sector about their inflation expectations in the short and medium term. Domestic economic activity held up well in H1:2023-24, underpinned by private consumption and investment activity. The sustained buoyancy in services, consumer and business optimism, government’s continued thrust on capex, and healthy balance sheets of banks and corporates brighten the outlook. Geopolitical tensions, geoeconomic fragmentation, signs of a global economic slowdown and El Niño conditions pose risks. Underpinning the resilience of domestic economic activity in H1:2023-24, private consumption was driven by stable urban demand and a gradual revival in rural demand. Investment activity gained traction from sustained government capex. On the other hand, weak external demand restrained domestic activity. On the supply side, the broad-based buoyancy of services activity was sustained by the strong momentum driving contact-intensive services. Agriculture activity has withstood the vicissitudes of the south-west monsoon. Manufacturing sector extended a modest recovery on the back of moderating input cost pressures and improving profit margins. Aggregate demand conditions exhibited buoyancy with real gross domestic product (GDP) posting a growth of 7.8 per cent (year-on-year, y-o-y) in Q1:2023-24, surpassing its pre-pandemic level by 13.6 per cent ( Chart III.1 and Table III.1). The momentum of GDP – quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q) seasonally adjusted annualised growth rate (saar) – exhibited the usual seasonal decline in Q1:2023-24 in line with the post-pandemic trends, albeit the pace of contraction was less than a year ago. GDP Projections versus Actual Outcomes The April 2023 Monetary Policy Report (MPR) had projected real GDP growth at 7.8 per cent for Q1:2023-24. Actual growth turned out to be the same as the projection (Chart III.2).   III.1.1 Private Final Consumption Expenditure Private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) – the mainstay of aggregate demand – rose by 6.0 per cent in Q1:2023-24 and contributed 3.5 percentage points to overall GDP growth. Amongst the high frequency indicators (HFIs) of urban consumption, domestic air passenger traffic and passenger vehicle sales recorded sustained growth in H1 (Chart III.3a and b); however, consumer durables were subdued during April-July, dragged down by textiles, readymade garments, and cut and polished diamonds (Chart III.3c). Bank credit to households remained supportive of urban consumption ( Chart III.3d). Rural demand showed incipient signs of recovery in H1 (Chart III.4). Tractor sales recovered during May-August, exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Motorcycle sales also expanded in Q1 but dipped in July-August and trailed last year levels. Consumer non-durables and sales volume of major fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) improved in H1. Fertiliser sales recovered in July-August after a dip in Q1 with the progress of kharif sowing.    The labour force participation rate1 inched up to 40.9 per cent in September 2023 from 39.8 per cent in March (Chart III.5a). The unemployment rate increased to 8.9 per cent in September from 8.6 per cent in March in urban areas while in rural areas it moderated to 6.2 per cent from 7.8 per cent during this period. The Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) payrolls data point to an improvement in employment conditions in the organised sector during June-July (Chart III.5b). III.1.2 Gross Fixed Capital Formation Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) expanded by 8.0 per cent in Q1:2023-24, driven up by the government’s capex push and a modest uptick in private sector investment. The share of GFCF in GDP was 34.7 per cent in Q1, the same as a year ago. Amongst the key underlying indicators, imports of capital goods expanded during April-August, led by machinery, electrical and non-electrical goods and iron and steel ( Chart III.6a). Railway locomotives, separators, bodies of trucks and buses supported the domestic production of capital goods (Chart III.6b). Coincident indicators of construction activity – steel consumption and cement production – posted strong growth in H1, bolstered by both residential spending and government’s infrastructure push ( Chart III.6c and d). Capacity utilisation (CU) in the manufacturing sector2 recorded a seasonal dip to 73.6 per cent in Q1:2023-24 from 76.3 per cent in Q4:2022-23, close to the long-term average of 73.7 per cent 3. Seasonally adjusted capacity utilisation improved to 75.4 per cent from 74.1 per cent (Chart III.7). Stretched capacity utilisation in manufacturing presages the need for new capacity additions to keep pace with the strength of underlying domestic demand in the economy. The interest coverage ratio (ICR)4 of listed non-financial private companies in the manufacturing and information technology (IT) sectors persisted at high levels in Q1, indicating comfortable debt servicing capacity. The ICR of non-IT services companies also ruled above the threshold level of one (Chart III.8).     III.1.3 Government Consumption Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) contracted by 0.7 per cent in Q1:2023-24, pulling down GDP growth. The central government’s revenue expenditure excluding interest payments and subsidies grew by 13.1 per cent (y-o-y) during April-August 2023 5. The outgo on major subsidies surged by 32.5 per cent during April-August due to higher food and fertiliser subsidies. Capital expenditure expanded by 48.1 per cent (y-o-y) during April-August, driven by 35.3 per cent increase in capital outlay, led by railways sector (Chart III.9a). The revenue expenditure to capital outlay (RECO) ratio decreased to 4.1 in April-August from 4.9 a year ago, indicative of the ongoing qualitative improvement in central government expenditure (Chart III.9b). On the receipts side, the central government’s gross tax revenues increased by 16.5 per cent y-o-y during April-August 2023, driven by a growth of 26.1 per cent in direct taxes. Indirect tax revenues expanded by 7.9 per cent y-o-y, aided by goods and services tax (GST) collections and custom duties (Table III.2 and Chart III.10). GST collections (centre plus states) drew buoyancy from improving economic activity and compliance. Custom duty receipts surged - despite a contraction in merchandise exports and imports - on account of, inter alia, higher export and import duties for a few items. Union excise duties inched down, partly on account of the cut in excise duty on petrol and diesel in May 2022. Overall, net tax revenue of the central government increased by 14.8 per cent during April-August.  The central government’s non-tax revenues jumped by 79.4 per cent during April-August 2023 due to higher dividends and profits (Chart III.11). The Reserve Bank of India’s dividend rose to ₹87,416 crore from ₹30,307 crore last year. During April-August, the central government’s gross fiscal deficit (GFD) stood at 36.0 per cent of the full year’s budget estimates (BE), higher than 32.6 per cent a year ago.  Turning to state governments, their consolidated GFD is budgeted at 3.1 per cent of the GDP in 2023-24, i.e., within the 3.5 per cent limit stipulated by the central government. Growth in revenue receipts is budgeted to accelerate, led by tax revenue (Table III.3 and Chart III.12a). Capital spending is expected to rise by 40.3 per cent in 2023-24 on top of 18.5 per cent a year ago, boosted by the support of ₹1.3 lakh crore from the central government under the ‘Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment’. The revenue expenditure to capital outlay ratio is budgeted to fall to 5.0 in 2023-24 from 6.1 in 2022-23.  Amongst the key deficit indicators of the states/UTs, consolidated revenue deficit improved during April-July 2023, while gross fiscal deficit deteriorated due to front loading of capex during this period ( Chart III.12b). Capital expenditure of the states increased by 49.8 per cent y-o-y during April-July, aided by an additional instalment of tax devolution from the central government and an approval of ₹84,884 crores (as on July 25, 2023) from the centre under the ‘Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment’. The Union Budget 2023-24 provided for gross and net market borrowings through dated securities at ₹15.43 lakh crore and ₹11.81 lakh crore, respectively. The centre’s gross issuances of market borrowings through dated securities amounted to ₹8.88 lakh crore during H1 (57.6 per cent of the full year’s budgeted amount) (Table III.4). The weighted average cost of issuances during H1 at 7.2 per cent was marginally lower than 7.3 per cent a year ago, while the weighted average maturity elongated to 17.6 years from 15.7 years. During H2, the Centre's gross market borrowings through dated securities have been planned for ₹6.55 lakh crore. States raised gross market borrowings of ₹3.58 lakh crore during H1 as against ₹4.37 lakh crore in the indicative calendar. During Q3:2023-24, indicative calendar has placed states gross market borrowings at ₹2.37 lakh crore. To meet the transitory mismatches between receipts and expenditure, the Ways and Means Advances (WMA) limit for the central government for H1 was ₹1.5 lakh crore, and it has been fixed at ₹50,000 crore for H2. For states/ union territories, the WMA limits remained at ₹47,010 crore as recommended by the Advisory Committee on Ways and Means Advances to State Governments (Chairman: Shri Sudhir Shrivastava). III.1.4 External Demand India’s external demand was weighed down by the slowing global economy, persisting geopolitical tensions, and geoeconomic fragmentation. Merchandise exports and imports (US$ terms) have been in contraction territory since February 2023. Services trade exhibited slowdown during April-August amidst global headwinds. According to the NSO, exports of goods and services contracted by 7.7 per cent in real terms, while imports of goods and services grew by 10.1 per cent, resulting in a sharp jump in the drag from net exports to (-) 6.4 per cent of GDP in Q1:2023-24 from (-) 0.1 per cent in Q4:2022-23 and (-) 2.3 per cent a year ago. Merchandise exports (US$ terms) fell by 11.9 per cent y-o-y during April-August 2023, and merchandise imports by 12.1 per cent. The merchandise trade deficit moderated to US$ 98.9 billion in April-August 2023 from US$ 112.9 billion a year ago as the decline in imports outpaced that in exports (Chart III.13). Merchandise exports experienced a broad-based downturn across commodities. During April-August 2023, 18 out of 30 major commodities (with a share of 73.9 per cent in the export basket) registered a decline on y-o-y basis, led by petroleum products, gems and jewellery and engineering goods. On the other hand, electronic goods, iron ore and drugs and pharmaceuticals, accounting for 13.5 per cent of total merchandise exports 6, contributed positively to export growth (Chart III.14). Overall, non-oil exports fell by 7.5 per cent during this period.    In the case of imports, 17 major commodities, accounting for 55.4 per cent of the imports basket, registered contraction during April-August 2023, driven by petroleum and crude products, coal and chemicals. Electronic goods, machinery, electrical and non-electrical products and gold imports, on the other hand, expanded (Chart III.15). Non-oil non-gold imports fell by 9.0 per cent. Services exports were buoyed by software services, business and financial services and travel services in Q1:2023-24. Services exports growth moderated substantially to 6.8 per cent during April-August 2023 from 32.1 per cent a year ago, partly reflecting slowdown in key partner countries (Chart III.16). Services imports posted a muted growth of 0.9 per cent in Q1:2023-24, with decline in outgoes under transportation servces. Services imports declined by 1.5 per cent y-o-y in July-August 2023. On a balance of payments basis, the current account deficit narrowed to 1.1 per cent of GDP in Q1:2023-24 from 2.1 per cent of GDP in the corresponding period of the previous year on the back of lower merchandise trade deficit, higher net surplus in services exports and robust inward remittances. In the financial account, net FDI inflows moderated to US$ 5.8 billion during April-July 2023 amidst a broader fall in global FDI flows ( Chart III.17). Manufacturing, financial services, business services, and computer services were the major recipient sectors while Singapore, Japan, the Netherlands, the USA and Mauritius were the major source countries of inward FDI to India.   Foreign portfolio investment (FPI) rebounded mainly through the equity route in response to investors’ positive outlook on domestic growth and corporate earnings. FPI inflows of US$ 20.5 billion were recorded in H1:2023-24 as against an outflow of US$ 8.1 billion during the same period last year. External commercial borrowing (ECB) flows also exhibited a turnaround, with net inflows at US$ 4.5 billion in 2023-24 (up to August) in comparison with net outflows of US$ 3.2 billion in the same period of last year, driven by higher disbursements. Net accretions to non-resident deposits inched up to US$ 3.0 billion during April-July 2023 from US$ 1.4 billion a year ago, mainly due to higher flows in Foreign Currency Non-Resident (FCNR-B) deposits. As on September 29, 2023, India’s foreign exchange reserves amounted to US$ 586.9 billion, equivalent to 10.1 months of projected merchandise imports in 2023-24 and 93.9 per cent of outstanding external debt at end-June 2023. Aggregate supply – measured by real gross value added (GVA) at basic prices – expanded by 7.8 per cent in Q1:2023-24 (11.9 per cent a year ago), led by services sector activity ( Table III.5). Moderating global energy and non-energy pricessupported value addition in both manufacturing andservices sectors. Petroleum product prices have an asymmetric impact on activity: the positive impactof easing prices is lower than the negative impactof an equivalent increase in prices (Box III.1).