Rajiv Ranjan, Rajeev Jain, Atri Mukherjee*

The paper attempts to review the growing economic dynamism of the Asian region reflected in its expanding role in the world economic affairs and growing cooperation at regional/sub-regional level. Before the ensuing discussion on assessment of existing arrangements for economic cooperation in the region and India’s participation in the process, the paper briefly provides a macroeconomic review of the Asian region. Lastly, the paper identifies the major issues and challenges which need to be addressed for furthering a successful move towards greater regional economic and monetary cooperation. The upshot is that the process of economic integration in the Asian region is not without ifs and buts.

JEL Classification : R1, R11

Keywords : Regional Economics, Regional Economic Activity

Introduction

Regional cooperation arrangements have emerged as an important aspect of the present day world economic set up. Attempts at various forms of regional cooperation have been noted at almost all the parts of the world. European Community (EC), European Union (EU), North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Mercado Comúndel Cono Sur (MERCOSUR) are examples of some of the major regional economic arrangements in Western Europe, North America and South America, respectively. The growing trend towards forming of regional economic arrangements is reflected in terms of a sharp increase in the number of bilateral and multilateral trade and investment treaties signed by countries all over the world during the last decade.

The Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) formed in 1967 was the first major regional block arrangement signed in Asia. The regional integration in Asia, however, has reached new dimensions during the last two decades due to changing dynamics of the Asian economy. East Asia for the past couple of decades has seen significant increases in intra-regional cross-border trade, investment and financial flows, thereby emerging as an independent economic zone. Multinational corporations (MNCs) have created a production network in the region by placing various sub-processes of production in different countries according to comparative advantage, relative factor proportions and technological capabilities. As a result, intra-regional, intra-industry trade in manufactured product, parts, components, semi-finished and finished products has soared. The deepening interdependency, coupled with concern about a recurrence of the Asian financial crisis that hit in the late 1990s, prompted the Asian economies to undertake various initiatives for regional monetary and financial cooperation.

Strong macroeconomic performance, along with growing number of regional cooperation arrangements have helped Asia to emerge as an independent economic zone. The region as a whole has gained sufficient power to influence the global economic order. It would, therefore, be interesting as also necessary to take a stock of the current status of various regional economic arrangements in Asia and identify the major challenges. Based on the above objectives, the paper has been arranged as follows: The role of regional integration in the process of globalization has been analysed in Section I. A recent macroeconomic review of the Asian economies is provided in Section II. The position of emerging Asia in the world economy is assessed in Section III. Section IV describes in detail, various existing regional cooperation arrangements in Asia. India’s role in the regional integration process in Asia has been reviewed in Section V. Some of the emerging issues, including some major challenges in this regard are identified in Section VI. Conclusions are drawn in Section VII.

Section I

Globalisation and Role of Regional Integration

Regional integration arrangements have become a part and parcel of the present global economic order and are likely to have sharp implications for the prospects of global economy. Regional integration has been defined as “an association of states based upon location in a given geographical area, for the safeguarding or promotion of the participants,” an association whose terms are “fixed by a treaty or other arrangements.” Philippe De Lombaerde and Luk Van Langenhove (2005) defined regional integration as “a worldwide phenomenon of territorial systems that increase the interactions between their components and create new forms of organisation, co-existing with traditional forms of state-led organisation at the national level.’’

In this context, the issue - whether the process of globalization and the growing regionalism complement each other or the growing regionalism is detrimental to globalization, has become a subject of intense discussion for policy makers and economists. Some perceive that globalization is nothing but a greater integration of economies nationally, regionally and worldwide. For others, since the regional integration process remains concentrated exclusively to certain countries, doubts arise whether such exclusivity throws up building blocks or stumbling blocks on the road to global economic integration.

Since mid-1980s, regionalization process has accelerated worldwide with varying features and scale in different regions. According to World Trade Organisation, as of September 2006, there were 211 regional trade arrangements as compared with only two dozen agreements in 1986 and 66 agreements in 1996. According to World Investment Report 2006 by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), international investment agreements (IIAs) have increased substantially. At global level, the total number of IIAs was close to 5,500 at the end of 2005, comprising 2,495 bilateral investment treaties (BITs), 2,758 double taxation treaties (DTTs) and 232 other international agreements that contain investment provisions. The total number of BITs among developing countries has increased sharply from 42 in 1990 to 644 by the end of 2005 while the number of DTTs rose from 105 to 399, and the number of other IIAs from 17 to 86 during the same period. Asian countries are particularly engaged as parties to approximately 40 per cent of all BITs, 35 per cent of DTTs and 39 per cent of other IIAs.

The economic aspect of regionalization may be described as efforts to form free-trade zones through the creation of common markets, the coordination of economic policies and the implementation of joint economic policies. Apart from economic benefits, the growing regionalism perhaps also has significant implications to strengthen the bargaining power of the regional grouping vis-à-vis the global system and enlarge the space for policy autonomy within the region. Several such instances can be observed, albeit with varying degrees of integration across different regions of the world. For instance in Western Europe, regional block is represented by the EC and the EU, in North America by the NAFTA, and in South America by the MERCOSUR. Within Asia, different sub-regions are at different stages of regional integration. East Asia has been pursuing different regional block arrangement for the longest period of time and has thus made the most progress, especially the ASEAN+3 countries. Together, these countries are now working on initiatives to deepen integration not only in trade and investment, but they have also started the process for monetary and financial cooperation.

Section II

Macroeconomic Review of Asian Economies

Emerging and developing economies of Asia grew at its fastest pace in 11 years in 2006 since the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98. Growth in emerging Asia has persistently increased from 5.0 per cent in 2001 to 9.3 per cent in 2006. This growth has been led most visibly by China and, increasingly, India, but several other Asian countries play a vibrant role as well. Growth in emerging Asia is likely to remain significant in the near future as per the IMF projections (Table 1).

Being the fastest growing economies of the world, over the past two years, China and India contributed 73 per cent to the Asian growth and 38 per cent to the world GDP growth. Asian region, as a whole, with

Table 1 : GDP Growth in the Asian and the Pacific Region |

(Per cent) |

|

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007P |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

East Asia |

8.0 |

4.7 |

7.5 |

7.3 |

8.4 |

8.3 |

9.0 |

8.9 |

South East Asia |

6.7 |

1.8 |

4.8 |

5.3 |

6.5 |

5.6 |

6.0 |

6.1 |

South Asia |

4.5 |

5.2 |

3.7 |

7.8 |

7.4 |

8.7 |

8.8 |

8.1 |

Central Asia |

8.4 |

10.8 |

8.7 |

9.4 |

9.7 |

11.2 |

12.4 |

10.3 |

The Pacific |

-0.2 |

2.4 |

0.4 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

3.5 |

Asia |

7.1 |

4.4 |

6.4 |

7.1 |

7.9 |

7.9 |

8.5 |

8.3 |

Memo items: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China |

8.4 |

8.3 |

9.1 |

10.0 |

10.1 |

10.4 |

11.1 |

11.5 |

India |

5.4 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

6.9 |

7.9 |

9.0 |

9.7 |

8.9 |

Newly Industrialized |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Asian Economies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(NIAEs) |

7.9 |

1.2 |

5.4 |

3.2 |

5.8 |

4.7 |

5.3 |

4.9 |

ASEAN (4 countries) |

5.8 |

2.5 |

4.7 |

5.5 |

5.9 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

5.6 |

Emerging Asia |

6.9 |

5.0 |

6.4 |

7.5 |

8.5 |

8.7 |

9.3 |

9.2 |

P : Projection.

Note : ASEAN (4) includes only Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines and Malaysia.

Emerging Asia comprises China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, ASEAN (4), and NIAEs (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore).

Source : Asian Development Outlook, 2007 and World Economic Outlook, IMF October 2007. |

growing economic dynamism, is contributing close to 50 per cent of world growth (IMF, 2006). With the setting in of recovery in Japan, it is expected to be another engine of growth for the Asian as well as the global economy. Thus, four poles of growth - Japan, East Asia, China and India – forming a sort of quadrangle – have been emerging in Asia, which could sustain the global growth engine (Reddy, 2007). It is interesting to note that out of the top four economies in terms of GDP based on purchasing power parity, three Asian economies, viz., Japan, China and India are ranked at second, third and fourth place, respectively. In the context of growing Asia and its contribution, Rodrigo De Rato, the IMF Managing Director in a recent speech commented, “Asia has already reaped many benefits from globalization, and it now plays a major role in the global economy. ….Asia’s increased weight in the global economy must now be matched with increased rights and responsibilities in the conduct of international economic policy. The international community can learn from Asia’s successes. So it is important that Asia’s voice be heard.”

In 2006, steady global expansion of output and trade, moderate inflation with low real interest rates, as well as the impact of earlier reforms on productivity, were all conducive to growth in the Asian region. In many countries, circumstances proved unusually benign, and risks failed to materialize. Despite exceptionally fast growth and rising oil prices, consumer price inflation did not, in general, accelerate in 2006. In some countries, inflationary pressures rose as the year progressed.

External environment, in general has remained favourable in recent years for the Asian region. In fact, developing Asia’s trade surplus widened in 2006. In some countries, export growth was extraordinary. Broadly, current account payments positions moved in step with trade balances. For developing Asia, the current account surplus was 5.8 per cent of GDP in 2006, the largest on record (Table 2). In this context, it is argued that the surplus Asian economies are playing an essential role in expansion of global imbalances by financing the US current account deficit.

Large current account surpluses made a significant contribution to reserve accumulation (Table 3). Although the region attracted gross capital inflows in 2006, it also invested significantly overseas, which helped to stem the buildup of reserves. Of the increase in total reserves, just less than 80 per cent was attributable to current account transactions (ADB, 2007). The international reserves, including Japan, for the region as a whole are now estimated to have reached about US$ 3.9 trillion.

Table 2: Inflation and Current Account Balance (CAB) |

Sub-regions |

Consumer Prices

(Per cent change) |

CAB as % of GDP |

|

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

East Asia |

1.3 |

3.4 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

6.0 |

7.4 |

South East Asia |

3.4 |

4.2 |

6.3 |

7.1 |

6.7 |

5.1 |

4.9 |

7.8 |

South Asia |

5.0 |

6.3 |

5.3 |

5.9 |

2.4 |

-0.1 |

-1.2 |

-1.4 |

Central Asia |

6.6 |

5.8 |

7.7 |

7.9 |

-2.4 |

-1.7 |

1.2 |

4.7 |

The Pacific |

8 |

3.2 |

2.4 |

3.3 |

-1.2 |

-1.7 |

6.2 |

4.9 |

Developing Asia |

2.3 |

4.0 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

4.0 |

3.5 |

4.5 |

5.8 |

Source : ADB Database, 2007. |

Table 3: Gross International Reserves |

(US $ billion) |

Region |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Central Asia |

9.0 |

11.9 |

16.5 |

15.8 |

32.7 |

East Asia |

686.3 |

888.7 |

1,179.0 |

1,409.7 |

1,707.4 |

South Asia |

85.6 |

129.8 |

160.3 |

170.5 |

215.7 |

Southeast Asia |

208.4 |

243.2 |

289.5 |

302.7 |

364.4 |

The Pacific |

1.4 |

1.6 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

Source : Asian Development Outlook, 2007. |

The Asian region witnessed an IT induced slowdown during 2001. However, a sharp recovery in subsequent years led to rapid surge in the net capital inflows in the region since 2003. While improving fundamentals have been a major driving factor behind increased inflows into Asia, large-scale global liquidity, relatively benign interest rates in industrial countries and a seemingly low-risk aversion have also caused a shift of capital from industrial countries to emerging economies in general. According to IMF, emerging Asia is likely to receive about 32 per cent of total net private capital flows to all emerging market and developing economies during 2007 (Table 4). China dominates as a FDI destination and received US$ 69 billion in 2006. Emerging Asian economies, particularly, China and India are also becoming increasingly

Table 4: Trend in Private Capital Flows (Net) in EMEs |

(US $ billions) |

|

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

Emerging market and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

developing countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Private Capital Flows |

72.1 |

80.6 |

90.1 |

168.3 |

239.4 |

271.1 |

220.9 |

495.4 |

Direct Investment |

170 |

185.9 |

154.7 |

164.4 |

191.5 |

262.7 |

258.3 |

302.2 |

Private Portfolio Flows |

12.5 |

-79.8 |

-91.3 |

-11.7 |

21.1 |

23.3 |

-111.9 |

20.6 |

Other Private Capital Flows |

-110.6 |

-25.8 |

26 |

14.5 |

25.1 |

-17 |

73.6 |

171 |

Emerging Asia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Private Capital Flows |

5.9 |

23.3 |

24.4 |

65.3 |

146.8 |

83.3 |

40.5 |

157.2 |

Direct Investment |

60.8 |

53.1 |

53.4 |

70.2 |

66.9 |

107 |

102 |

97.7 |

Private Portfolio Flows |

19.7 |

-50.1 |

-60 |

7.9 |

11.8 |

-13.5 |

-120.8 |

-26.7 |

Other Private Capital Flows |

-74.6 |

20.3 |

31.1 |

-12.9 |

68.1 |

-10.2 |

59.3 |

86.2 |

Source : World Economic Outlook, October 2007. |

important as a provider of direct investment to industrial countries as well as other emerging markets. China and India have become the world’s most favored destination for foreign direct investment, surpassing the United States.

The growing strength of the Asian economies is also significant because at one point in time during the Asian crisis of the second half of 1990s, these economies had suffered a major setback. These economies have successfully and rapidly recovered from the financial crises and almost ten years later, with persistent policy efforts, they have today the foreign exchange and financial markets which are much more stable. However, it seems that growth in crisis hit economies of Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia and Thailand has settled on a lower trajectory (Chart 1).

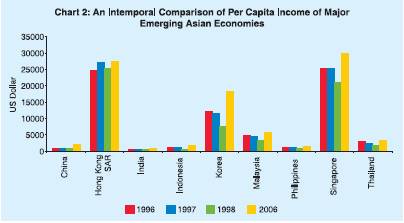

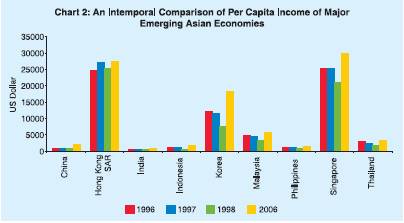

In addition, per capita incomes in the crisis economies now surpass their pre-crisis peaks despite a brief dip during the crisis years (Chart 2). Social indicators are improving, and the region is again enjoying growth that is one of the fastest among the emerging economies from other regions.

As a whole, under the present circumstances, many conditions are favorable for most of the Asian economies. First, they currently enjoy strong global demand for their exports, favourable terms of trade

and easy access to external financing. Second, large foreign currency reserves along with reduced external debt as percentage of GDP are cushion factors against any sudden withdrawal by investors in the financial markets. Third, though public debt in several Asian economies still remains at elevated levels, many of them are of longer maturity and considerably higher proportions are in local currency denomination. Fourth, the banking system has been strengthened through restructuring. Fifth, the resilience to external shocks is reinforced by combination of less balance sheet exposure to exchange rate changes, less refinancing risks in debt structures, strong fiscal and financial cushions and above all an observed tendency for more flexibility in policies.

Although the Asian region as a whole has exhibited robust growth performance and resilience to external shocks, many of the smaller economies, particularly those of Central Asia continue to remain vulnerable to various economic crises. In this context, the Asian emerging economies need to take a constant review of the implications of the on-going global developments. For instance, the rapid accumulation of reserves may prove to be increasingly costly, especially as some regional central banks are facing challenges to effectively sterilise their monetary effects leading to adverse inflationary consequences in some countries. One important policy step in this context would be that surplus economies of the region particularly in Southeast Asian region must develop more effective and efficient financial intermediation domestically or on regional basis so as to use domestic savings for domestic and regional development.

Section III

Emerging Asia in the World Economy

The rapid growth of emerging market economies in Asia has been a notable feature of the global economy in recent years. In fact, Asia’s rise on the world stage started with the so-called “Asian miracle” - the economic success of Japan and then the small “dragons” and “tigers”, viz., South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Thailand. The burst of the economic bubble in Japan and the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis cast a shadow over Asia’s success story for a short period, but most East Asian economies quickly assumed their growth path again. Further more, China’s rapid emergence as an economic power on the world stage adds much to Asia’s attractiveness. Now India, after decades of slow growth, is also catching up. The emerging markets of Asia, with their dynamic and increasingly skilled work force, are well-placed to take advantage of new technologies and seize opportunities in the international market place to become a major engine of growth in the global economy. At present, Asia accounts for more than 30 per cent of world GDP and contributes half of global growth. This impressive performance has been associated with the region’s firm integration into the global economy, as well as its emergence as a leading producer of the goods that the world demands.

Since the beginning of the new millennium, the performance of the world economy has been shaped by the increasingly important role of China and India along with several other Asian countries as well. The strong performance of these economies, combined with the continued dynamism of the US has helped sustain the current worldwide expansion in recent years, offsetting sluggishness in Europe and also in Japan (Burton, 2005). Being the fastest growing economies of the world, China and India contribute around 73 per cent to the Asian growth and 38 per cent to the world GDP growth (IMF, 2005). Asia’s merchandise trade growth was sustained by strong US import demand, and intra-Asian trade, stoked by a recovery in electronics trade. In 2004, China became the largest merchandise trader in Asia, and the third largest exporter and importer in world merchandise trade. Sustained rapid growth in recent years and rising living standards have been accompanied by a dramatic increase in Asia’s shares in world exports and raw material consumption (Table 5). The deepening of Asia’s economic relations with the rest of world is also evident from the fact that total Asian trade increased from 38 per cent of GDP in 1996 to 61 per cent of GDP in 2006. Such a high degree of openness also means that growth in emerging Asia, in general, is less domestically driven and thus is exposed to unfavorable external developments. The region, however, has demonstrated time and again its capacity to rebound from adverse shocks within a short period. Indeed, after the 1997 crisis, most affected economies were able to restore stability and resume growth after just one year (Aziz, 2007).

Propelled by high savings levels, many Asian countries are dedicated to improving education, modernizing infrastructure and raising production capacities. With their rapid per capita income growth and expanding consumer base, these markets offer some of the best investment and business opportunities and therefore emerging and

Table 5: Growth in Exports and Imports in Asian Sub-Regions |

(Per cent) |

|

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 P |

2008 P |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Merchandise Exports |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central Asia |

8.9 |

26.0 |

41.1 |

41.1 |

32.8 |

16.9 |

14.4 |

East Asia |

12.2 |

22.6 |

28.0 |

19.0 |

19.0 |

13.6 |

14.0 |

South Asia |

13.6 |

20.9 |

24.0 |

20.8 |

18.8 |

14.9 |

14.8 |

Southeast Asia |

5.1 |

12.9 |

20.4 |

15.1 |

17.9 |

10.0 |

10.7 |

The Pacific |

-5.4 |

33.9 |

11.1 |

21.6 |

27.4 |

-4.0 |

-12.0 |

Average |

9.9 |

19.5 |

25.7 |

18.4 |

19.0 |

12.7 |

13.1 |

Merchandise Imports |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central Asia |

0.9 |

20.4 |

34.5 |

26.4 |

22.2 |

14.5 |

11.3 |

East Asia |

10.5 |

23.9 |

28.7 |

14.4 |

17.5 |

13.5 |

14.1 |

South Asia |

8.8 |

22.2 |

39.3 |

30.0 |

24.9 |

17.8 |

17.7 |

Southeast Asia |

5.3 |

9.9 |

24.6 |

18.1 |

15.6 |

10.8 |

12.5 |

The Pacific |

3.9 |

13.6 |

19.1 |

7.7 |

19.0 |

11.0 |

-1.8 |

Average |

8.6 |

19.6 |

28.5 |

16.9 |

17.8 |

13.2 |

14.0 |

P : Projected.

Source: Asian Development Outlook, 2007. |

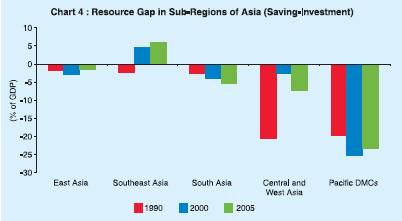

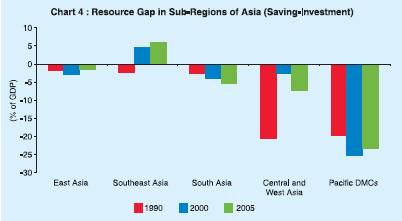

developing Asia has remained a favoured destination for foreign direct investment. However, it has been noted that investment rates in emerging Southeast Asian countries is not as high as savings rates (Chart 3 and 4).

Given this economic dynamism, the economic and political relations between Asia and the rest of the world especially the US have become deeper and assumed new dimensions. This, in turn, enabled many Asian countries particularly emerging Asian economies to connect to new opportunities, and contribute to the ongoing process of globalisation. As a result, the Asian region has increasingly become a major centre of world trade, global capital flows and other macroeconomic parameters. According to IMF, the developing Asian economies on average accounted for 35.5 per cent of total net capital flows in all emerging market and developing countries during 2001-2006.

The upbeat performance of emerging Asian economies in recent period has spurred new confidence about the future prospects of the Asian region. Asia’s growing role in the global economy has also naturally increased the region’s desire to assume a higher profile in the international financial community. In fact, one can expect that in the years ahead, economic policy decisions in Asia will have profound effects on the global economy. Therefore, issues pertaining to the region assume greater importance at the present juncture.

Section IV

Regional Cooperation within Asia

Regionalism is gradually deepening its roots in certain parts of Asia. There has been a growing awareness of regional identity in Asia since the end of the Cold War. Sub-regional and functional institutions are playing an important role in economic, political and security cooperation. Big economies of Asia are taking a great deal of interest in enhancing economic cooperation at regional level leading to growing regionalism in the Asian region. For instance, China is stressing the prime importance of neighboring areas in its foreign relations while Japan is reviewing the implications of neglecting Asia. India is pursuing a “Look East” policy. The small and medium sized countries are also contributing to forming up a regionalism so as to benefit from this development. Regional economies, especially from the East/South-East Asia have achieved strong economic interdependence, particularly through external liberalization, domestic structural reforms and market-driven integration with the global and regional economies. Expansion of foreign trade, direct investment and financial flows has created a “naturally” integrated economic zone in East Asia (Kawai, 2005).

There is an ongoing transformation in the composition of production and trade as the comparative advantage of many Asian economies continues to change. In particular, economies with relatively high wage costs are shifting towards higher value-added products, including services. The is evident from the shift of labor-intensive manufacturing out of Hong Kong into mainland China and the associated boost to Hong Kong’s economy from the growth of trade and financial services. Financial flows within the region have become more significant. Although the developing countries of Asia still rely on London and New York to intermediate foreign savings to the region, but Japan continues to remain the world’s largest exporter of capital. Moreover, Hong Kong and Singapore, with their well-capitalized banks, efficient clearing and settlement systems, and expanding range of financial products, have also emerged as major financial centres. Increasingly, these centres are intermediating savings within Asia, as well as channeling saving to Asia from other parts of the world. In particular, Hong Kong seems to have become the main channel for investment in China which also arranges a significant proportion of Asia’s syndicated borrowing. Singapore has also evolved into the main banking centres for Southeast Asia. Therefore, increasing trade and financial sector integration in the global economy and in the region offers enormous potential benefits (Camdessus, 1997).

With countries becoming more closely integrated, each country has an increasing stake in the sound policies of the others. Accordingly, this facilitates a greater and constructive role for countries of the region in encouraging each other to maintain sound policies. The swap arrangements among a number of Asian central banks are a good example of constructive cooperation to maintain regional stability. It would be worthwhile exploring how such initiatives can be further developed. The growing share of intra-regional trade, particularly in east Asian countries, substantiates the growing interdependence in the region, albeit, limited largely to the East/Southeast Asian nations. Furthermore, the intra-regional trade intensity index for ASEAN countries is higher than the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and European Union nations confirming the higher degree of regional integration.

An important dimension to the growing economic cooperation in the Asian region, particularly the East/Southeast Asian region has been its defence against the proliferation of regional trade agreements elsewhere perhaps NAFTA and in Europe. Furthermore, the economies of the region realized the importance of scale economies for productivity and international competitiveness and thus reflecting their efforts towards trade and investment integration. More recently, the East-Asian crises also made them realize that deeper integration and institution building at the regional level is essential to become resilient to the external shocks. The regional nature of spillovers (contagion) during the crises period might have reinforced the need for regional arrangements, i.e., market driven regionalism. The increasing trend towards regionalism in Asia also reflects the hidden intent of the region to have an effective ‘Asian’ voice in global affairs when the progress in multilateralism is felt to be slow. Another argument often forwarded in the context of regional integration has been that it could serve as a powerful tool in helping all countries sustain the high levels of economic and employment growth needed to reduce poverty, and in spreading the benefits of growth more equitably within and across countries (Kuroda, 2005). In this context, it would be pertinent to discuss the existing formal and informal arrangements that facilitate better cooperation among the member nations in one or the other way.

Existing Cooperative Arrangements in Asia

Even though the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) has been existing in Asia since 1967, the efforts towards regional economic cooperation got intensified since the financial crises of 1997-98. Since then the East Asian economies have embarked on various initiatives for regional monetary and financial cooperation. Subsequently, the major initiatives for regional cooperation in Asia include ASEAN+3, Chang Mai Initiative, Executives’ Meetings of East Asia- Pacific Central Banks (EMEAP), Asian Bond Market Initiative and Asian Bond Fund. These initiatives have largely remained limited to the East/Southeast Asian economies.

Recognising the importance of regional integration, the southern Asian region also constituted the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1985 which included Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The following discussion gives a brief account of activities done under the various regional cooperative arrangements.

(i) ASEAN /ASEAN+3

The genesis of the present ASEAN+3 dates back to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations or ASEAN which was established in August 1967 at Bangkok by the five original member countries, viz., Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand while Brunei Darussalam (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos and Myanmar (1997), and Cambodia (1999) joined later. The decision to realise an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) gained momentum in the aftermath of the East Asian crisis. East Asian countries felt that they would have to establish their own self-help mechanisms for financial cooperation and to deal with financial crises. In November 1997, ASEAN officials met in Manila and formulated the Manila Framework, which was later adopted by APEC. The core principle of the framework was to establish a regional surveillance mechanism. In February 1998, ASEAN finance ministers agreed to set up a peer surveillance system, which is a collective monitoring and early warning system, based on a G7 model, to supervise macroeconomic policies, financial regulation, and transparency of member countries.

In the meantime, the ASEAN also embarked on a process to expand economic cooperation with its neighbours in the north, namely China, Japan and South Korea (now termed as ASEAN+3). In a way, this process can be seen as a kind of widening of economic integration. In 1997, a joint statement between ASEAN and each of ‘plus three’ countries was signed providing for a framework for cooperation towards the 21st century. The ASEAN + 3 aims at further strengthening and deepening East Asia cooperation at various levels and in various areas, particularly in economic, social, political and other fields. In fact, to assist Asian countries in overcoming their economic difficulties and to contribute to the stability of international financial markets, an initiative known as “the Miyazawa Initiative” was undertaken by Japan, under which a commitment to provide a package of support measures totaling US$30 billion was made for the crises hit Southeast Asian economies. The ASEAN+3 process now involves summits amongst heads of states, meetings of foreign ministers, economic ministers and finance ministers, and meetings of senior officials. In terms of promoting an East Asia region-wide cooperation agenda and a regional arrangement, the ASEAN+3 processes witnessed significant progress since 1998. In 2001 the ASEAN+3 leaders endorsed the idea of an East Asian Economic Community.

It is, however, often argued that ASEAN’s agenda would be diluted by a wider East Asian regional arrangement, because China and Japan are much bigger economies than ASEAN as a whole. It is argued that combined size of the economies of ASEAN, China, Japan, Korea, and India (though not part of ASEAN+3) is larger than that of the European Union in terms of income, and bigger than the NAFTA in terms of trade (Executive Intelligence Review, February 18, 2005)1.

Economic Relations within ASEAN

Since the inception of ASEAN in 1997, the Association has successfully forged close political cooperation among its members and created an environment of peace and stability in the region which facilitated its member countries to concentrate on nation building and economic development. As a result, countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and Indonesia could achieve impressive economic growth, increased prosperity, and improved living standards in the 1980s and 1990s. The international community lauded these dynamic ASEAN countries as the “East Asian Miracle” because their economies seemed to have the winning formula for sustainable economic growth (Hew and Anthony, 2000). ASEAN’s efforts at maintaining regional peace through closer political and security cooperation and its accompanying economic success earned the recognition of ASEAN as one of the world’s most successful regional organizations. However, economic gains achieved by ASEAN countries over the past decade were essentially wiped out as the Asian financial crisis posed the greatest challenge to regional cooperation because many observers argued that ASEAN’s cohesiveness during this period was undermined by the financial turmoil. Hence, there were doubts on ASEAN as a viable regional institution.

When ASEAN was established, trade among the member countries was insignificant. The share of intra-ASEAN trade in the total trade of the ASEAN members was estimated to range between 12 and 15 per cent in early 1970s. Some of the earliest economic cooperation schemes of ASEAN were aimed at addressing this area. One of these was the Preferential Trading Arrangement (PTA) of 1977, which accorded tariff preferences for trade among ASEAN economies. Ten years later, an Enhanced PTA Programme was adopted at the Third ASEAN Summit in Manila further increasing intra-ASEAN trade. Subsequently, the Framework Agreement on Enhancing Economic Cooperation was adopted at the Fourth ASEAN Summit in Singapore in 1992, which included the launching of a scheme toward an ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). The strategic objective of AFTA was to increase the ASEAN region’s competitive advantage as a single production unit. The purpose of elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers among the member countries was to promote greater economic efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness. In 1997, the ASEAN leaders adopted the ASEAN Vision 2020, focusing on ASEAN Partnership aiming at forging closer economic integration within the region. The vision statement also resolved to create a stable, prosperous and highly competitive ASEAN Economic Region, in which there is a free flow of goods, services, investments, capital, and equitable economic development and reduced poverty and socioeconomic disparities. The Agreement was further clarified in the Hanoi Plan of Action, adopted in 1998, which emphasized on the strengthening of the ASEAN Surveillance process, development of the ASEAN Bond Market and studying the feasibility of establishing an ASEAN currency and exchange rate system. At present financial cooperation in ASEAN focuses on the implementation of the Roadmap for monetary and financial integration, covering mainly the areas of capital market development, financial services liberalization and capital account liberalization.

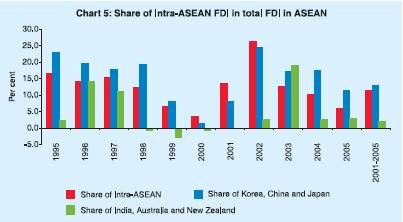

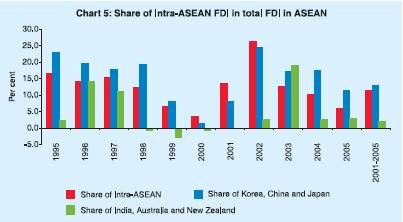

ASEAN cooperation has resulted in greater regional integration. Since the launch of AFTA (1992), exports among ASEAN countries grew from US$ 43.26 billion in 1993 to almost US$ 164 billion in 2005, an average yearly growth rate of 5.3 per cent and the share of intra-regional trade in ASEAN’s total trade rose modestly from 20 percent to almost 25 percent. In contrast, intra-ASEAN net FDI inflows are still insignificant with a share of 11.5 per cent in total net FDI inflows in ASEAN region (Chart 5). However, intra-ASEAN tourist flow has increased substantially. During 2001-2006, about 44 per cent of total tourist flow emanated from within ASEAN itself.

From strategic perspective, ASEAN has been engaged in a number of wider regional or inter-regional cooperation arrangements on the basis of a concentric circles approach. The logic of this approach is straightforward. By strengthening cooperation within ASEAN, the group can engage more effectively in the wider regional grouping; in turn, the wider regional grouping can further promote ASEAN’s interests and strengthen its participation at the global, multilateral level. This approach provided the justification for ASEAN to take an active part in the development of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group. One of the rationales for an East Asian regional arrangement was that there should be an effective ‘Asian’ voice in global affairs and East Asia should be placed on a more equal footing with the US so as to effectively manage trans-Pacific relations in a way similar to that of Europe and the United States in the trans-Atlantic relationship (Soesastro, 2003).

(ii) Chiang Mai Initiative of ASEAN+3

The Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) aims to create a network of bilateral swap arrangements (BSAs) among ASEAN+3 countries to

address short-term liquidity difficulties in the region and to supplement the existing international financial arrangements. The CMI was announced by the Finance Ministers of ASEAN+3 in May 2000 with the intention to cooperate in four major areas, viz., monitoring capital flows, regional surveillance, swap networks and training personnel. The Initiative represents a significant step in reserve sharing among the ASEAN+3 countries in the post-crisis years. The total resources available under CMI’s network of 16 BSAs are currently estimated to be around US$ 83 billion (up from less than US $ 40 billion in May 2005), reflecting the renegotiation of most BSAs. BSAs have been concluded among eight countries: China, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. More recently, at the 10th ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers’ Meeting on May 5, 2007 (Kyoto, Japan), finance ministers unanimously agreed in principle that a self-managed reserve pooling arrangement governed by a single contractual agreement is an appropriate form of CMI multilateralisation, proceeding with a step-by-step approach. Finance ministers instructed the Deputies to carry out further in-depth studies on the key elements of the multilateralisation of the CMI including surveillance, reserve eligibility, size of commitment, borrowing quota and activation mechanism, while reiterating their commitment to maintain the two core objectives of the CMI.

(iii) Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

Since its inception in 1989, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) has become a premier forum for facilitating economic growth, cooperation, trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific region. APEC is the only inter governmental grouping (with 21 members from Asia, Latin America and North America) in the world operating on the basis of non-binding commitments, open dialogue and equal respect for the views of all participants2. Unlike the WTO or other multilateral trade bodies, APEC has no treaty obligations required of its participants. Decisions made within APEC are reached by consensus and commitments are undertaken on a voluntary basis. APEC member economies take individual and collective actions to open their markets and promote economic growth. The APEC has been focusing on three key areas, viz., (i) trade and investment liberalization, (ii) business facilitation and (iii) economic and technical cooperation During first decade of its inception, APEC Member Economies generated nearly 70 per cent of global economic growth and the APEC region consistently outperformed the rest of the world, even during the Asian financial crisis. APEC member economies take individual and collective actions to open their markets and promote economic growth by showing commitment to open trade, investment and economic reform. By progressively reducing tariffs and other barriers to trade, APEC member economies, in general, have become more efficient and exports have expanded dramatically.

(iv) SEANZA and SEACEN

South East Asia, New Zealand and Australia (SEANZA) is one of the oldest regional central bank groups which was formed in 1957 outside of East Asia with original members of Australia, India, New Zealand, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Later on, many East-Asian nations were included in SEANZA and currently, the total number of members of SEANZA is 203. Under SEANZA, central bank governors meet annually. SEANZA also promotes cooperation among central banks by conducting intensive training courses for higher central banking executive positions with the objective to build up knowledge of central banking and foster technical cooperation among central banks in SEANZA region.

Similarly, South East Asian Central Banks (SEACEN) was organised in 1966 in order to provide a forum for SEACEN central bank governors to be familiar with each other and to gain deeper understanding of the economic conditions of the individual SEACEN countries. Since its establishment, the members of the SEACEN Centre have grown. There are currently fourteen member central banks and monetary authorities. In addition to the original eight members, it is joined by the Bank of Korea (January 1990), The Central Bank of China, Taipei (1992), The Bank of Mongolia (May 1999), the Ministry of Finance, Brunei Darussalam on (April 2003), the Reserve Bank of Fiji (April 2004), and the Bank of Papua New Guinea (June 2005). Reserve Bank of India is one of the twelve invitees for SEACEN trainings at the SEACEN Centre.

(v) Executives’ Meeting of East Asia Pacific Central Banks

Set up in 1991, the Executives’ Meeting of East Asia Pacific Central Banks (EMEAP) is a cooperative organization of central banks and monetary authorities in the East Asia and Pacific region. The prime objective of EMEAP is to strengthen the cooperative relationship among its members. It comprises the central banks of eleven economies4.

The financial crisis in Asia affirmed the importance of EMEAP activities, which have nurtured the regional network of information exchange and mutual trust. Despite the recent proliferation of international meetings and institutions, EMEAP has succeeded in maintaining its uniqueness as a meeting for central banks in the region. The ongoing work of EMEAP seeks to further strengthen policy analysis and advice within the region and encourage co-operation with respect to operational and institutional central banking issues. In one of the recent Board Meetings, the following four areas have been identified for further strengthening of EMEAP:

Communication and collaboration with other international entities

Greater publicity of outputs from EMEAP activities,

Extending the scope and depth of discussions at the technical level, and

Enhanced technical cooperation among member central banks.

The Asian Bond Fund (ABF) initiative of the EMEAP Group aimed at broadening and deepening the domestic and regional bond markets in Asia. In June 2003, EMEAP launched the first stage of ABF (ABF1), which invests in a basket of US dollar denominated bonds issued by Asian sovereign and quasi-sovereign issuers in EMEAP economies (excluding Australia, Japan and New Zealand). The Fund is passively managed by the BIS. After the success of ABF1, the EMEAP Group has extended the ABF concept to bonds denominated in local currencies and launched the second stage of ABF (ABF2) of US$ 2 billion in December 2004. The key objective of ABF2 is to provide investors a convenient and low cost instrument to invest in Asian local currency bonds and, at the same time, to identify and remove impediments to the process of bond market developments. The ABF2 comprises a Pan-Asian Bond Index Fund (which is now named as ABF Pan-Asian Bond Index Fund (PAIF)) and eight Single-market Funds which invests in sovereign and quasi-sovereign local currency-denominated bonds issued in the eight EMEAP markets and represent a new asset class in Asia5. In the near term, the ABF2 Initiative is expected to help raise investor awareness and interest in Asian bonds by providing innovative, low-cost and efficient products in the form of passively managed bond funds. Further ahead, it is believed that it serves to further broaden and deepen the domestic and regional bond markets and hence contribute to more efficient financial intermediation in Asia, by promoting new products, improving market infrastructure and accelerating developments in relevant EMEAP markets. EMEAP claims that the ABF2 Initiative has helped accelerate tax and regulatory reform at both regional and domestic levels to facilitate cross-border investments. For instance, the PAIF is the first foreign institutional investor that has been granted access to China’s inter-bank bond market. Malaysia has, with effect from 1 April 2005, liberalised its foreign exchange administration rules. EMEAP’s investments in ABF2 are held through the Bank for International Settlements investment vehicle, the US Dollar denominated BIS Investment Pool (BISIP). Up to April 2006, six ABF2 funds were successfully offered to the public, raising a total of about US$ 400 million from non-EMEAP investors. ABF2 seems to have paved way for broader investor participation in the Asian bond markets. The asset size of the listed Single-market Funds have recorded a growth in the range of 24-50 per cent (up to end-April 2006) despite rising interest rates in the US during that period. The performance of PAIF has also been reasonably good with a growth of 19 per cent and is being increasingly accepted as an asset class by the Japanese institutional investors.

(vi) Asian Clearing Union

Another important arrangement of central banking cooperation in the South Asian region has been the Asian Clearing Union (ACU)6 headquartered at Tehran, Iran. The agreement on the ACU originated after a considerable period of efforts and discussions sponsored by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). The agreement was signed by the central banks and monetary authorities in December 1974. The Union is an arrangement for multilateral settlement of payments for promoting trade expansion and monetary co-operation among the member countries. Economizing on the use of foreign exchange reserves by utilization of national currencies, shifting of banking services from non-domestic to domestic one, providing short term credits facilities for two months for member countries are the core objectives of the union. Since 1989, the ACU has also included a currency swap arrangement among its operational objectives in order to facilitate easy access by participants to international reserves of other participants at a time when foreign exchange support is needed. The success of ACU is evident from the fact that over the past quarter of a century, it has not experienced a default, while many of the other developed country payment unions have been faced with the arrears problem.

(vii) SAARC /SAARCFINANCE

Under the aegis of SAARC7, South Asian Preferential Trade Agreement (SAPTA) was the first step towards the transition to a South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) leading subsequently towards a Customs Union, Common Market and Economic Union. The Agreement on South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) came into force in 2006. Under the Trade Liberalisation Programme scheduled for completion in ten years by 2016, the customs duties on products from the region will be progressively reduced. However, under an early harvest programme for the least developed member States, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka are to bring down their customs duties to 0 - 5 per cent by January 2009 for the products from such member countries. The least developed member countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives and Nepal) are expected to benefit from additional measures under the special and differential treatment accorded to them under the Agreement.

Under the SAARC forum, the SAARCFINANCE was established in September 1998 as a regional network of the SAARC Central Bank Governors and Finance Secretaries after recognizing the need to strengthen the SAARC with specific emphasis on international finance and monetary issues. The Chairperson of SAARCFINANCE is invited to the sessions of the SAARC Council of Ministers to make a presentation on SAARCFINANCE activities. The members of the network meet at least twice a year at the time of the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank. The SAARCFINANCE cells exchange publications and information on subjects relevant to financial sector in the member countries. Cooperation among central banks and finance ministries in SAARC member countries is promoted through staff visits and regular exchange of information.

(viii) BIMSTEC

In 1997, a sub-regional grouping, i.e., the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) was formed in Bangkok. BIMSTEC provides a unique link between South Asia and Southeast Asia exploring a considerable amount of complementarities between the two regions. A study shows the potential of US$ 43 to 59 billion trade creation under BIMSTEC FTA. The BIMSTEC aims to achieve its own free trade area by 2017. The priority sectors of BIMSTEC include trade & investment, technology, energy, transport & communication, tourism, fisheries, agriculture, cultural co-operation, environment and disaster management, public health, people-to-people contact, poverty alleviation and counter-terrorism and transnational crimes.

(xi) Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation

The Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program is an ADB-supported initiative to encourage economic cooperation in Central Asia. CAREC’s objective is to promote economic growth and raise living standards in participating countries by encouraging regional economic cooperation. The Program has concentrated on financing infrastructure projects and improving the region’s policy environment in the priority areas like transport, energy, trade policy and facilitation.

CAREC is also an alliance of multilateral institutions comprising the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Monetary Fund, the Islamic Development Bank, the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank. CAREC operates in partnership with other key regional cooperation programs and institutions, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Eurasian Economic Community. Up to end April 2007, ADB has approved and financed 16 loans totaling US$ 499.8 million for different CAREC-related projects.

Section V

India and Regional Cooperation in Asia

India has a long history of foreign trade and cultural relations with the emerging Asian economies as is recorded in ancient and medieval history. India’s growing trade and financial integration with the Asian region has worked as a driving force towards its renewed interest in regional co-operation within Asia, under the “Look East Policy”. There has been a significant shift in destination and sources of India’s merchandise trade across developing and advanced economies. Developing countries or the South has emerged as the major destination for India’s exports, accounting for about 60 per cent of India’s total merchandise exports as compared with 40 per cent about a decade ago. Emerging Asia including China and other East Asian countries accounted for about a fifth of India’s total exports during 2006-07 (doubled from early 1990s), similar to the share of European Union in India’s total exports. China has emerged as the major trading partner for India, next only to the US. Similarly, over the years, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore have emerged as major investors in India.

In this context, India recognizes the fact that in a globalised world, collective regional endeavour may be viewed as an expression of enlightened self-interest, especially amongst the developing countries (Sinha, 2004). Accordingly, India has entered into various regional economic cooperation, free/preferential trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties with its Asian neighbours. India’s position and stance in relation to various regional cooperation (viz., SAARC, BIMSTEC, ASEAN) and free/preferential trade agreements are discussed in brief in the following discussion.

(i) India and the SAARC

The SAARC was formed on the ideas of sovereign equality, territorial integrity, political independence, non-interference and mutual benefit. South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) has been ratified by all SAARC members to enhance trade flows within the region8. India has taken a leadership role in the development of SAARC. Being the largest and economically strongest country in the region, India opened up its markets for neighbouring countries to create a truly vibrant and globally competitive South Asian economic community.

There are causes of concern as at times India is criticized for having a big brotherly attitude by other members. However, economic cooperation is directly linked with security in the region. The SAARC will find it challenging to accelerate pace of cooperation until India’s relations with Pakistan and Bangladesh are normal. However, the SAARC members countries are becoming conscious of the fact that there is a huge potential for permitting trade within the region and enhancing economic interaction to their mutual advantage.

(ii) India and BIMSTEC

India and six other BIMSTEC countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand) have decided to enhance their cooperation and strategic capabilities in dealing with terrorism and transnational crime and preventing counterfeiting of currencies and forgery. The Government of India has formulated a five-point agenda for strengthening economic cooperation amongst member nations of BIMSTEC (Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand). Through its participation in BIMSTEC, India seeks to strengthen its bilateral trade, investment and technology links with member countries.

(iii) India and ASEAN

Through its “Look East” policy, India has been actively forging cooperation agreements with its eastern neighbors. In the context of Asian Bond Fund, an informal meeting was organized by Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) on May 1, 2004 in Bangkok, which was attended by participants from 18 countries including India, to discuss promotion of supply of Asian Bonds with a view to facilitating setting up of ABF. In the recent period, RBI has been open to the idea of participation in Asian Bond Fund (ABF).

India has set its economic and strategic stakes in Southeast Asia as it was among the 16 nations participating in the landmark East Asia Summit held at Kuala Lumpur on December 2005. Besides the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the “Plus-Three” group comprising China, Japan and South Korea, three other nations, viz., India, Australia and New Zealand were invited to the summit. The summit was very significant as it was expected to develop the future regional architecture in East Asia –an economically vibrant and strategically significant region. India mooted free trade pact between ASEAN and six countries including Japan, China, Korea, Australia, New Zealand and India., i.e., ASEAN+3+3. However, a cost-benefit analysis is must before moving towards such arrangements.

(iv) India’s Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

India has been actively engaged in the regional cooperation arrangements at different forums. Recognizing the importance of regionalism, India has entered into various regional trading arrangements (RTAs) with the objective of expanding export market. Apart from these, a few important framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation (CECAs) have also been entered into with regions/countries like ASEAN and Singapore. India has signed a number of free trade agreements with various countries including its neighbouring Asian nations. Some of the existing trade agreements of India with other regions/countries include the Bangkok Agreement, Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP), SAARC Preferential Trading Agreement (SAPTA), India Sri-Lanka FTA, India-Thailand FTA, India-Singapore Comprehensive Economic Cooperation (CECA), Indo-Nepal Trade Treaty, India-Mauritius PTA and India Chile PTA. Some of the ongoing framework agreements of India include Indo-ASEAN CECA, South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA), Framework Agreement on BIMSTEC, FTA, India-MERCOSUR PTA. India has also set up a number of joint task forces to study the feasibility and benefits that may derive from the possible China-India RTA, India-Korea free trade agreement and India-Gulf Cooperation Council FTA.

In order to facilitate the free flow of goods and services, India also focuses on integration of rail and road linkages in its extended neighbourhood. The India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral highway and Delhi-Hanoi railway is being planned. India has started building a transport corridor through Iran to Afghanistan. India has liberalized air services with SAARC countries and the ASEAN.

Apart from these, in order to boost foreign capital flows, particularly foreign investment (both direct and portfolio) India has entered into bilateral investment treaties and double taxation avoidance agreements with various countries including its neighbours.

(v) India-China-Japan Regional Cooperation

Many economists believe that the US economy could face long term decline due to growing structural imbalances. One obvious alternative strategy being discussed in international forum these days is to create more intra-regional trade and capital flows within the larger Asian regions so as to evolve an alternative hub besides the US that will drive the global growth. It is believed that a strong alternative to the US market can only emerge if a larger open trade block emerges in the Asian region centred around China, India, Japan and ASEAN. There is a huge potential to create a regional market supported largely by China and India. It has been suggested that the larger regionalized Asian market must create sufficient conditions-regulatory and corporate governance institutions to attract investments from Japan, China and India, which have accumulated large stock of foreign exchange reserves, currently invested mainly in US treasuries. Confidence on this score could be enhanced through ASEAN-China and ASEAN-India free trade agreements, which create a regional framework for freer flow of trade, investment and skilled labour. There could be an extensive intra-regional production network, based on exchange of parts, components, intermediate products, with China and India at its core, as these would be the biggest consuming baskets in the near future.

Some signs of these are visible with the first ever joint acquisition of a Syrian oil asset by India and China as also the historical resumption of India-China border trade through the strategic Nathu La pass. Indo-Japanese relations can also be judged from the fact that India has been the first country to which Japan extended the first Yen Loan and India has been one of the largest recipients of Japan’s overseas development assistance. Agreement on Commerce between Japan and India in 1958 was one of the remarkable treaties signed by the two nations to strengthen their trade relations. The Indo-Japanese trade talks on overall bilateral trade and investment began in 1978 and since then have expanded to new economic dimensions. Besides, private sector forum such as ‘Joint Meetings of the Japan-India Business Cooperation Committee’, which holds annual joint meetings, promotes private-sector bilateral cooperation in various economic fields as well as mutual understanding. At present, almost 500 Japanese companies are operating in India. The Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) has also set up an incubation facility for Japanese investments into India and has established a dedicated India desk at its Tokyo Office. Thus, business to business engagement will be the determining factor for the success of Indo-Japanese economic relationship.

SectionVI

Issues in the Area of Regional Cooperation in Asia

Although the experience and lessons of other regional blocks might provide useful insights for enhancing regional cooperation in Asia, but one has to take cognizance of certain issues for successful functioning of cooperative arrangements particularly monetary union type of arrangement being envisaged in Asia. In this context, Langhammer (2007) argues, “Trying to influence East Asian integration by pointing to EU experiences would probably not be very fruitful given the fact that East Asia, if it continues to follow the ASEAN+3 concept, will become as inward-oriented as the EU with its widening and deepening process. Yet, even under such disperse styles of integration in Europe and East Asia, globalization and the ever-rising importance of cross-border externalities like environment, management of common resources, terrorism, and military threats will induce East Asia to consider using most European ways of making integration and cooperation effective, such as by defining the rationales, setting targets, monitoring implementation, multilateralizing bilateral arrangements, and, finally, involving the private sector. And it is this last way that is most likely to convince East Asia to take the lessons provided by EU integration seriously”.

It has been argued that Asia is currently at a stage in which the discussion focuses on regimes to stabilise intra-regional currency fluctuations (Münchau, 2007). The Europeans were at the same stage in the 1970s, when they set up the European Monetary System after a series of failed attempts to stabilise exchange rate movements. Therefore, the European Monetary System (EMS), not the euro, is most relevant for the Asian region today. If one compares the Asian efforts towards monetary integration with those of Europe, it is found that in case of Europe, the participation at the political level in the process towards greater monetary integration started soon after the fall of Bretton Woods system. In Asia, however, the discussion has remained limited to central bankers, academicians and other experts. Even the efforts have accelerated in real sector integration through better trade relations but these are not much organised and concerted. For instance, there are overlapping trade agreements in the Asian region which are not desirable for an arrangement akin to the Europe’s single market. Another contrast in European monetary integration and the Asian Monetary Integration is lack of indicative targets. From the very beginning of its history, the EU had set priorities and milestones in implementing program in order to remain credible and recognizing the so-called “costs of non-Europe,”. However, in the case of Asia such concrete indicative framework has not been put in place so far.

However, the Asian Development Bank has now formally adopted a Regional Cooperation and Integration Strategy. This is designed to support economic integration in four key areas: (i) cross-border infrastructure and related services; (ii) cooperation in trade and investment; (iii) monetary and financial cooperation and integration; and (iv) cooperation in the provision of regional public goods. The ADB is also developing a framework for mobilizing the resources required to implement the Strategy - the Regional Cooperation and Integration Financing Partnership Facility. Furthermore, the Report of the Eminent Persons Group to the President of the Asian Development Bank (2007) identified that the objectives of ADB’s work in regional cooperation and integration should be building and expanding regional collective actions and helping the region engage effectively at the global level. Regional cooperation comprises five major areas, viz., physical connectivity, global commons, trade in goods and services, financial integration, and monetary and exchange rate coordination. It also emphasized that free trade in goods, services, labor, and capital is a primary benefit of regional cooperation and integration. Short of a global open market, a single regional market for goods, services, labor, and capital should be the goal of regional economic cooperation on trade in Asia. Asia should aim at ultimately creating a single market encompassing the major Asian economies, including the four largest countries that account for 83 per cent of Asian GDP, viz., Japan, China, India, and Republic of Korea, while following “open regionalism.” The Report also suggested that the ADB should help the region pursue a bottom-up, market-driven approach to financial integration rather than a top-down “region-wide broad vision”.

Despite these efforts, the progress relating to these issues suggests that monetary integration in Asia has a long way to go and full-fledged monetary integration on Euro lines would be a challenging task to achieve in short-term horizon. However, there has been a considerable progress in efforts towards trade and investment integration within the region which eventually are likely to facilitate the process of monetary integration in the long run. Despite the fact, the region has been far more active in negotiating real sector accords but these are viewed as economically and politically sub-optimal. Although the region has taken due cognizance of significant complementarities that exist in trade structure but there is still a vast scope for further bilateral trade which testifies to the gains that can accrue from free trade zones and the eventual use of a common currency. A number of studies have shown a strong and positive impact of trade of China, India, Japan and Korea on growth in ASEAN region which suggests a strong case for further monetary integration. Plummer and Wignaraja (May 2007) attempted a number of simulations on the correlation of business cycles and economic effects of potential trade groupings and finally suggests that the economic potential for monetary integration in Asia is strong, even Mr. Haruhiko Kuroda, the current President of the Asian Development Bank, proposed for setting up of arrangements to create an Asian Currency Unit, on the lines of the European Currency Unit that preceded the creation of European Monetary Union and the euro. The idea was not a totally new concept, having been previously suggested by former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad at the 1997 ASEAN summit, by Nobel economics laureate Robert Mundell at a lecture in Bangkok in 2001, and by Philippines’ President Gloria Arroyo at the 9th annual Future of Asia Conference hosted by Nihon Keizai Shimbun in 2003. This idea has been mooted on the basis of the concept that it will avoid the volatility of intra-Asian currency markets and create a currency, which can well be one of the principal currencies of the world. The idea got a further boost at the meeting of the Asian Development Bank held recently at Istanbul. However, adoption of single currency in the region could be a long-term agenda point for regional cooperation in Asia as one can see from the experience of the European union. The rationale for an Asian Currency Unit at the micro-level is to afford regional economic agents the opportunity to invoice regional financial and trade transactions in the Asian Currency Unit, hence reducing the region’s dependence on the US dollar and other external currencies. If Asian Currency Unit is successful, intra-regional intermediation of savings may be promoted, in the process possibly reducing the region’s exposure to external shocks (Rajan, 2006). Although the Asian currency unit can help Asian economies to keep the relative price of regional currencies stable, the cost of joining a formal regional monetary cooperation is the relinquishment of the autonomy of their domestic policies. Asian monetary cooperation needs to provide more potential benefits if it is to attract Asian economies (Bin and Fan, 2007).

Despite such anticipated benefits, technical and political obstacles remain in respect of Asian currency unit. Thus, the ADB project has not moved much forward. No consensus has been reached on which standard the common currency unit would be calculated whether it should be the participating countries’ gross domestic product or their external trade. Likewise, the issue has certain political dimensions as well. It is still to be decided whether the Hong Kong dollar and the Taiwan dollar would be included in the scheme. In short, the launch of Asian Currency Unit seems to be a distant possibility and needs much more discussion on a number of issues.

Apart from the issues of lack of political participation and convergence of exchange rate policies at the present stage of ongoing process, there are other important issues as well which could pose challenges for the process of Asian monetary integration. So far, most of the efforts towards greater monetary integration have remained limited either to East Asian countries, i.e., ASEAN or ASEAN+3. These countries are mostly heterogeneous both economically and politically. Although peace prevails within the ten-country ASEAN group, yet they have different political systems. A number of ASEAN/ ASEAN+3 members including China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam fall far short of being democracies. Apart from these, there are certain issues pertaining to social and institutional development which could emerge as formidable challenge as process of monetary integration gathers pace.

(i) Exchange Rate Coordination

There is no a priori scenario for currency cooperation within the ASEAN+3. There exists a wide spectrum of exchange rate arrangements between hard pegging and pure floating. This situation points to a need for further research concerning what constitutes the optimal exchange rate regime, and for closer international cooperation on exchange rate policy. Therefore, the important issue is whether the intra-regional stabilisation should occur by means of a fixed or semi-fixed exchange rate against a basket of international currencies, or whether it should be based on a free-floating regional monetary unit, an Asian Currency Unit, to which each member currency would be tied. In short, there is a coordination failure in exchange rate policies in Asia. Therefore, any sharp movement in the US dollar exchange rate could have severe implications for intra-regional Asian exchange rate stability.

It is important to note that a number of EMEs in East Asiaface a trade-off between the virtue of exchange rate stability to promote trade, investment, and growth and the need for flexibility, particularly during a time of crisis, to maintain international price-competitiveness and facilitate adjustment. Economies in the region are still prone to exchange rate volatility in the absence of sound financial systems and flexible real sector. For small but open economies of the region, exchange rate volatility can be disruptive to the growth and development. It is to be noted that Asian economies grew rapidly during periods of exchange rate stability. For intra-regional exchange rate stability, greater coordination on the currency basket policy would be desirable, and this needs to be supported by regional policy dialogue and financing mechanisms. At the present point of time, the economic and political conditions today even in East Asia are not conducive to a regional monetary union or a move toward exchange rate coordination in the near future. However, views in this regard are mixed as Watanabe and Ogura (2006) argued that the optimal currency area conditions seem to be met by subsets of Asian countries although the ultimate success of an Asian currency union hinges crucially on factors including historical and political backgrounds, robustness of institutional set-ups, degree of regional convergence in developmental stages, and track record of sound macroeconomic policy in constituent countries.

Issues regarding the anchor currency are yet to be settled in respect of greater monetary integration in Asia. In this context, Wolfgang (2007) raises the following issues. First, whether the yen could form an anchor for the system, in the way the Deutche-Mark was the anchor currency of the EMS? Second, would that be acceptable to others, such as China and Korea? Third, would there have to be entry criteria similar to the EU’s Maastricht criteria? Fourth, does one need any arrangements for fiscal policy as well?

(ii) Heterogeneity within the Region

There is an extreme heterogeneity in almost each and every aspect (size, income level, economic structure, tariff levels) among the various countries of Asia. The unsettled political disputes on past and present issues could be a major stumbling block for regional integration in Asia on EU style which was a constructivist stages approach based on the rule of law. Therefore, in the Asian context, the transition to monetary union, including the crucial decisions about eligibility for membership, seems to be a more complicated process.

(iii) Lack of Maastricht Treaty Type Indicative Framework

If consensus or near-consensus on all of the major issues is reached, the region would have to draft a treaty analogous to the Maastricht Treaty, defining the path to full-fledged monetary union, the institutional design of the union itself, and the task of the various bodies that would be needed to take on related tasks, including the setting of common standards for prudential supervision, the setting and implementation of exchange-rate policy for the new currency, and, most importantly, the setting and subsequent application of the criteria for admission to the monetary union.

(iv) Development of Asian Debt Market

The development of Asian debt market is needed for enhance mobilization of regional savings for long term investments within the region. The Asian financial crisis was the culmination of twin crises, a currency crisis due to volatile capital flows, and at the same time a banking sector crisis. The crisis of 1997-98 underscored the limitations of even reasonably regulated, supervised, capitalised and managed banking systems and the importance of debt market. Against this backdrop and based on experience, it has been argued that bond financing reduces macroeconomic vulnerability to shocks and systemic risk through diversification of credit and investment risk. From the perspective of developing countries, a liquid corporate bond market can play a critical role in supporting economic development.