IST,

IST,

Report of the Internal Study Group to Review the Working of the Marginal Cost of Funds Based Lending Rate System

September 25, 2017 Dr. Viral V. Acharya, Dear Sir, We herewith submit the Report of the Internal Study Group to Review the Working of the Marginal Cost of Funds Based Lending Rate (MCLR) System.  An internal Study Group was constituted by the Reserve Bank on July 24, 2017 to study the various aspects of the MCLR system from the perspective of improving the monetary transmission and exploring linking of the bank lending rates directly to market determined benchmarks. The constitution of the Study Group was announced in the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies of the Reserve Bank of India on August 2, 2017. The Study Group submitted its report on September 25, 2017. The key findings emerging from the analysis undertaken by the Study Group and the recommendations made are set out below. Key Findings Monetary Transmission – the Base Rate and the MCLR Systems 2. A review of banks’ deposit and lending rates undertaken by the Study Group indicates that the transmission from the changes in the policy repo rate has been slow and incomplete under both the base rate and the marginal cost of funds based lending rate (MCLR) systems. The monetary transmission has improved since November 2016 under the pressure of large surplus liquidity in the system post demonetisation. While the transmission to interest rates on fresh loans was significant, it was muted to outstanding loans (base rate and MCLR). The transmission was also uneven across borrowing categories. Furthermore, the transmission to lending rates was asymmetric over monetary policy cycles – higher during the tightening phase and lower during the easing phase – irrespective of the interest rate system. For instance, the pass-through to outstanding loans from the repo rate was around 60 per cent during the tightening phase (July 2010 to March 2012), while it was less than 40 per cent during the subsequent easing phase (April 2012 to June 2013). 3. Analysis conducted by the Study Group suggests that banks deviated in an ad hoc manner from the specified methodologies for calculating the base rate and the MCLR to either inflate the base rate or prevent the base rate from falling in line with the cost of funds. These ad hoc adjustments included, inter alia, (i) inappropriate calculation of the cost of funds; (ii) no change in the base rate even as the cost of deposits declined significantly; (iii) sharp increase in the return on net worth out of tune with past track record or future prospects to offset the impact of reduction in the cost of deposits on the lending rate; and (iv) inclusion of new components in the base rate formula to adjust the rate to a desired level. The slow transmission to the base rate loan portfolio was further accentuated by the long (annual) reset periods. 4. Overall, monetary transmission has been impeded by four main factors: (i) maturity mismatch and interest rate risk in the fixed rate deposits but floating rate loan profile of banks; (ii) rigidity in saving deposit interest rates; (iii) competition from other financial saving instruments; and (iv) deterioration in the health of the banking sector. A major factor that impeded transmission was the maturity profile of bank deposits. Deposits with maturity of one year and above constituted 53 per cent of banks’ total deposits at end- March 2016, most of which were at fixed rates of interest. Another source of weak transmission was rigidity in interest rates on banks’ saving deposits, which remained notoriously stubborn even as the policy repo rate and interest rates on term deposits moved in either direction. The third factor, which hindered monetary transmission was the competition that banks faced from other saving instruments. It appears that banks were reluctant to reduce interest rates sharply for fear of losing deposits to other financial saving instruments such as mutual funds and small saving schemes. Although bank deposits have some distinct advantages in the form of stable returns (vis-à-vis mutual fund schemes) and liquidity (vis-à-vis small saving schemes), bank deposits are in a disadvantageous position in terms of tax-adjusted returns in comparison with these schemes. Banks, therefore, often appeared to be reluctant to reduce interest rates on deposits in line with the reduction in the policy rate by the Reserve Bank. These factors imparted rigidity to the liability side of banks’ balance sheet. Finally, empirical analysis suggests that the extent of responsiveness of interest earnings and interest expenses to the changes in the policy repo rate is broadly the same, making the net interest margins (NIMs) impervious to monetary policy changes. The deterioration in the health of the banking sector and the expected loan losses in credit portfolios induced large variability in spreads in pricing of assets, severely impacting monetary transmission as banks’ NIMs have remained broadly unchanged in the face of large stressed assets. Thus, rigidities on the liability side such as longer-term maturity pattern of deposits with fixed interest rates, along with the expected loan losses on the asset side, have been reflected in higher pricing on the asset side, i.e., lending rates. Spreads charged over the Base Rate and the MCLR 5. Median spreads charged over the MCLR by all bank groups remained broadly stable in the case of fresh rupee loans from April 2016 to December 2016. However, median spreads charged rose sharply in January 2017. Median spreads of public and private sector banks declined by June 2017. However, while the median spread of private sector banks declined to the pre-January 2017 level, the median spread of public sector banks remained significantly above the pre-January 2017 level. 6. Spreads charged by private sector banks on fresh rupee loans were consistently the largest, followed by public sector banks and foreign banks. Spreads charged varied significantly across banks and also temporally. Spreads of foreign banks were relatively more volatile than those of public and private sector banks. 7. The transmission from the reduction in the MCLR to lending rates occurred with a lag. In the case of private sector banks, it took almost six months for the transmission from the lower MCLR to actual lending rates. However, in the case of public sector banks, the transmission was not complete even after six months. 8. The transmission to interest rates on outstanding rupee loans was significantly lower than on fresh rupee loans. The median spread in the case of outstanding rupee loans remained significantly higher than that of fresh rupee loans, reflecting the dominance of base rate loan portfolio in outstanding loans and lagged interest rate reset (normally one year) for the existing borrowers under the MCLR system. Spreads on outstanding loans were also more volatile than those on fresh loans. 9. Being an internal benchmark, the MCLR is expected to vary across banks. The spread over the MCLR could also vary from bank to bank due to idiosyncratic factors. However, variations in the spreads across banks appear too large to be explained based on bank- level business strategy and borrower-level credit risk. In particular, spreads charged by some banks seem excessively and consistently large. The analysis suggests that the spreads were mostly changed arbitrarily by banks for similar quality borrowers. While the spread over the MCLR was expected to play only a small role in determining the lending rates by banks, it turned out to be the key element in deciding the overall lending rates. This has made the entire process of setting lending interest rates by banks opaque and impeded the monetary transmission. 10. That many banks tended to charge the spreads over the MCLR arbitrarily is evident from a special study of select banks conducted by the Study Group. The key findings of the study are: (i) large reduction in MCLR was partly offset by some banks by a simultaneous increase in the spread in the form of business strategy premium ostensibly to reduce the pass-through to lending rates; (ii) there was no documentation of the rationale for fixing business strategy premium for various sectors; (iii) many banks did not have a board approved policy for working out the components of spread charged to a customer; (iv) some banks did not have any methodology for computing the spread, which was merely treated as a residual arrived at by deducting the MCLR from the actual prevailing lending rate; and (v) the credit risk element was not applied based on the credit rating of the borrower concerned, but on the historically observed probability of default (PD) and loss given default (LGD) of the credit portfolio/sector concerned. Recommendations 11. The recommendations made by the Study Group are detailed below. 12. The lower transmission from the policy rate to the base rate loan portfolio was mainly due to the reason that banks followed different methods to calculate the base rate. Banks, therefore, could be advised to re-calculate the base rate immediately by removing/readjusting arbitrary and entirely discretionary components added to the formula. It needs to be ensured that the calculation of the base rate is not compromised in any way. The methodology adopted by banks should be subject to a regular supervisory review. 13. In the absence of any sunset clause on the base rate, banks have been quite slow in migrating their existing customers to the MCLR regime. Most of the base rate customers are retail/SME borrowers. Hence, the banking sector’s weak pass-through to the base rate is turning out to be deleterious to the retail/SME borrowers in an easy monetary cycle. To address this concern, besides immediate recalculation of base rates (as recommended in para II.15), banks may be advised to allow existing borrowers to migrate to the MCLR if they so choose to do without any conversion fee or any other charges for switchover on mutually agreed terms. However, after the adoption of an external benchmark from April 1, 2018 as recommended by the Study Group (refer paras IV.43 - IV.45), banks may be advised to migrate all existing benchmark prime lending rate (BPLR)/base rate/MCLR borrowers to the new benchmark without any conversion fee or any other charges for switchover on mutually agreed terms within one year from the introduction of the external benchmark, i.e., by end-March 2019. 14. The Study Group recommends that it should be made mandatory for banks to display prominently in each branch the base rate/MCLR (tenor-wise) and the weighted average lending rates on loans across sectors separately for loans linked to the base rate and the MCLR. The same information should also be hosted prominently on each bank’s website. The Reserve Bank could prescribe the format and the manner in which a minimum set of standardised data needs to be displayed in branches/hosted on banks’ websites. The Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), or any other agency considered appropriate by banks, could also disseminate bank-wise information on its website in the same manner in which each bank is required to disseminate information on its own website so as to facilitate easy comparison of lending rates across sectors and banks. The same system of dissemination of information on the benchmark and the weighted average lending rate could be followed under the external benchmark system recommended by the Study Group (see paras IV.43 - IV.45). 15. An evaluation of 13 possible candidates [weighted average call rate (WACR), collateralised borrowing and lending obligation (CBLO) rate, market repo rate, 14-day term repo rate, G-sec yields, T-Bill rate, certificates of deposit (CD) rate, Mumbai inter- bank outright rate (MIBOR), Mumbai inter-bank forward offer rate (MIFOR), overnight index swap (OIS) rate, Financial Benchmark India Ltd. (FBIL) CD rates, FBIL T-Bill rates and the Reserve Bank’s policy repo rate)] suggests that no instrument in India meets all the requirements of an ideal benchmark. Each instrument has certain advantages as also limitations. After carefully analysing the pros and cons of 13 possible candidates as a benchmark, the Study Group narrowed down its choice to three rates, viz., a risk-free curve involving T-Bill rates, the CD rates and the Reserve Bank’s policy repo rate. The T-Bill rate and the CD rate1 were further assessed on three parameters, viz., (i) correlation with the policy rate; (ii) stability; and (iii) liquidity. The Study Group is of the view that the T-Bill rate, the CD rate and the Reserve Bank’s policy repo rate are better suited than other interest rates to serve the role of an external benchmark. 16. The T-bill rates are risk free and also transparent. They also have a reliable term money market curve. CD rates relate to the credit market directly in the sense that banks could meet their marginal requirement of funds from this market. CDs also have a reliable term money market curve. Unlike the T-Bill market where the money market term curve is available up to 12 months, in the CD market, the term curve is generally up to six months (and up to 9 months occasionally). The main challenge in using either T-bill rates or CD rates as the benchmark is that the current level of market depth in the T-Bill and CD markets can make such benchmarks potentially susceptible to manipulation. Also, T-Bill rates may at times reflect fiscal risks which will automatically get transmitted to the credit market when used as a benchmark. CD rates also have their own limitations - high sensitivity to liquidity conditions, credit cycles, and seasonality. Liquidity in the CD market is inadequate because there are no large and frequent issuances by a sufficient number of highly rated banks. The Reserve Bank’s policy repo rate has the primary advantage that it is robust, reliable, transparent and easy to understand. It reflects the appropriate rate for the economy at any point in time based on the MPC’s assessment of macroeconomic conditions and the outlook. With the repo rate as the benchmark, the transmission of the repo rate changes to lending rates of banks will be quick, direct and strong. The repo rate as a benchmark, however, can constrain future changes in the monetary policy framework. Banks also have limited access to funds at the repo rate. Being an overnight rate, the repo rate also lacks a term structure. 17. The Study Group recognised that internal benchmarks such as the base rate/MCLR have not delivered effective transmission of monetary policy. Arbitrariness in calculating the base rate/MCLR and spreads charged over them has undermined the integrity of the interest rate setting process. The base rate and MCLR regimes are also not in sync with global practices on pricing of bank loans. Given that there has not been much forward movement on the external benchmark even after seventeen years from the time when it was first allowed in the country, the development of an external benchmark would need guidance from the Reserve Bank. Accordingly, there is a need for switching over to one of the external benchmarks recommended by the Study Group, after wider public debate and taking into account the feedback from all stakeholders. Given the scope of arbitrariness under the MCLR system, however, the switchover to an external benchmark needs to be pursued in an expedient and time-bound manner. 18. The Study Group recommends that all floating rate loans extended beginning April 1, 2018 could be referenced to one of the three external benchmarks selected by the Reserve Bank after receiving and evaluating the feedback from stakeholders. 19. The Study Group is of the view that the decision on the spread over the external benchmark should be left to the commercial judgment of banks. However, the spread fixed at the time of sanction of loans to all borrowers, including corporates, should remain fixed all through the term of the loan, unless there is a clear credit event necessitating a change in the spread. 20. Banks may be encouraged to accept deposits, especially bulk deposits at floating rates linked directly to one of the three external benchmarks selected by the Reserve Bank after receiving the feedback from stakeholders as recommended by the Study Group. 21. The Study Group recommends that the corporates and banks be encouraged to actively manage interest rate risks once the external benchmark is introduced. It should also help deepen the IRS market, going forward. 22. Finally, but equally importantly, the reset clause, which is typically one year, impedes monetary transmission as the pass-through of monetary policy changes to existing floating rate loans is delayed. The Study Group, therefore, recommends that the periodicity of resetting the interest rates by banks on all floating rate loans, retail as well as corporate, be reduced from once in a year to once in a quarter. _________________________ I.1 The efficacy of monetary policy depends on the magnitude and the speed with which policy rate changes are transmitted to the ultimate objectives of monetary policy, viz., inflation and growth. With the deepening of financial systems and growing sophistication of financial markets, most monetary authorities use interest rate as the key instrument to achieve the ultimate objectives of monetary policy. Adjustments in the policy interest rate, for instance, directly impact short-term money market rates which then transmit the monetary policy impulses across financial markets and maturity spectrum, including banks’ deposit and lending rates. These, in turn, influence consumption, saving and investment decisions of firms and households, which ultimately influence aggregate demand, and hence, output and inflation. The interest rate channel of transmission – supported by liquidity management operations – is the leading channel of transmission in several countries, including many emerging market economies. I.2 In a bank dominated system like India, the transmission to banks’ lending rates is the key to the successful implementation of monetary policy. However, the issue of transmission from the policy rate to banks’ lending rates has all along been a matter of concern for the Reserve Bank. The transmission to banks’ lending rates has been impeded by a variety of factors, the major one being the opacity in the process by which the banks set their lending interest rates. To address this concern, the Reserve Bank has refined the interest rate setting methodology of banks from time to time. I.3 In 1994, when the lending interest rates were deregulated, the Reserve Bank prescribed that banks should disclose their prime lending rates (PLRs), which will be the interest rate charged for the most creditworthy borrowers. Keeping in view the request from banks that the PLR should be converted into a reference or benchmark rate for banks, the Reserve Bank advised banks in April 2003 to announce a Benchmark PLR (BPLR) with the approval of their boards. The dominance of sub-BPLR lending, however, defeated the very purpose for which the BPLR system was introduced. I.4 The Reserve Bank replaced the BPLR system with the base rate system in July 2010 under which the actual lending rate charged to borrowers was the base rate plus borrower- specific charges. However, the flexibility accorded to banks in the determination of cost of funds – average, marginal or blended cost – caused opacity in the determination of lending rates by different banks and rendered the assessment of monetary transmission difficult. I.5 The Reserve Bank instituted a new lending rate system for banks – the marginal cost of funds based lending rate (MCLR) system – effective April 1, 2016 with a view to improving transmission. The BPLR, the base rate and the MCLR were internal benchmarks set by each bank for pricing of credit. However, unlike the BPLR and the base rate, the formula for computing the MCLR was prescribed by the Reserve Bank. Since 2000, banks are also free to price credit linked to external benchmarks. However, the share of rupee loans linked to external benchmarks has been miniscule. I.6 The experience with the MCLR system has not been satisfactory, even though it has been an improvement over the base rate system. The transmission has remained uneven in terms of its pace and magnitude: (i) across the sectors of the economy; (ii) between deposit and lending rates; and (iii) between fresh rupee loans and outstanding rupee loans. The base rates of different banks, in particular, have remained rigid since introduction of the MCLR. While the extent of change in base rate may not necessarily mirror the changes in the MCLR, the rigidity of the base rate is a matter of concern for efficient transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. Also, a large portfolio of banks’ loans – about one-fourth – continues at the base rate and does not show the expected sensitivity to changes in the policy rate of the Reserve Bank. I.7 The spread, as measured by the difference between the lending rate and the 1-year MCLR, which was expected to be by and large stable, has shown large variations from month to month, from bank to bank and from sector to sector. While some variability in the spread over the MCLR was expected, large variations in the spreads are difficult to explain. Accordingly, an internal Study Group was constituted to study the various aspects of the MCLR system and explore linking of bank lending rates directly to market- determined benchmarks. The announcement of the Constitution of the Study Group was made in the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policy of the Reserve Bank on August 2, 2017. The Study Group comprised the following officials:

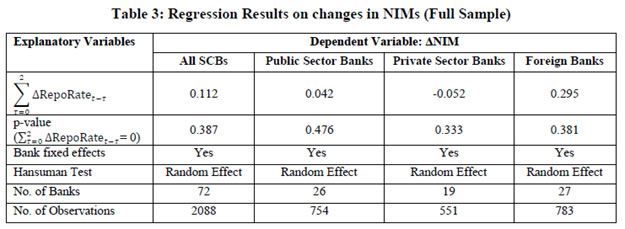

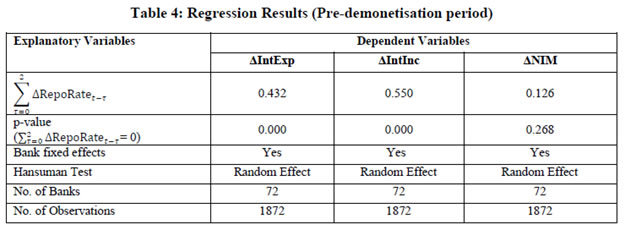

Terms of Reference of the Study Group I.8 The terms of reference for the Study Group were as under:

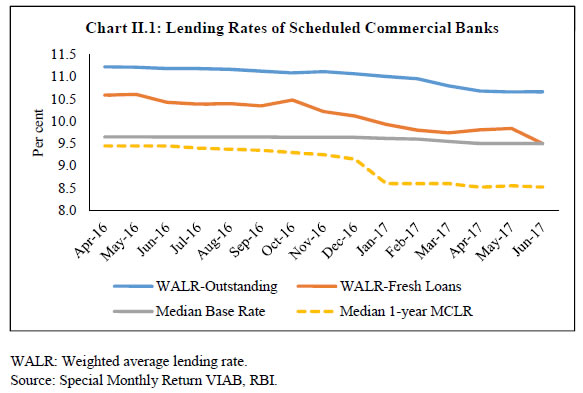

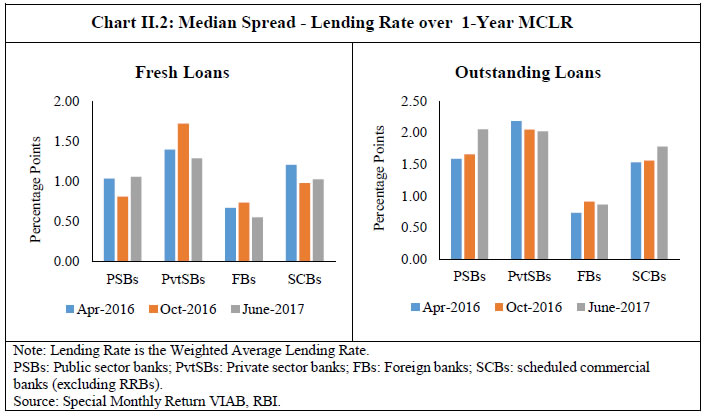

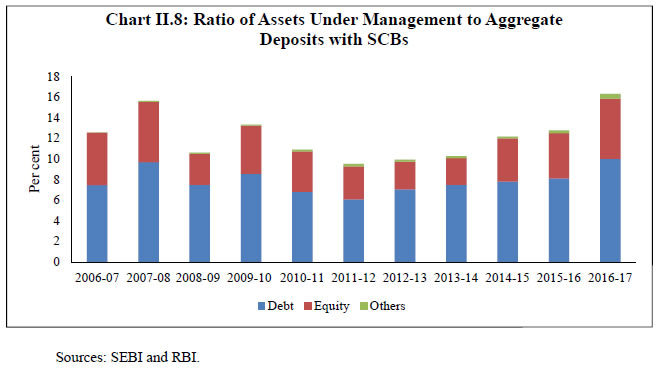

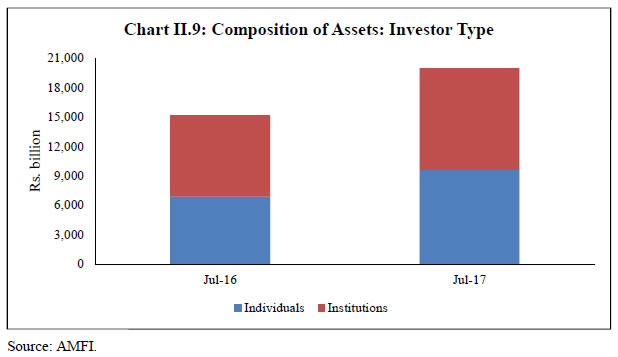

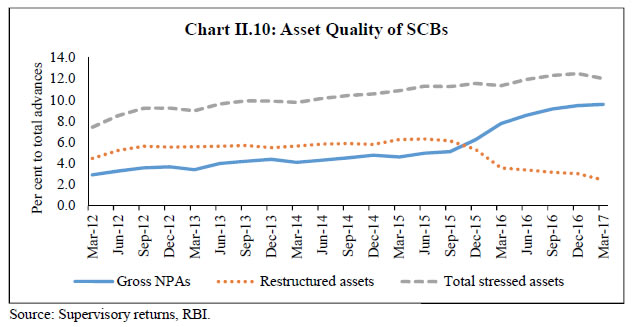

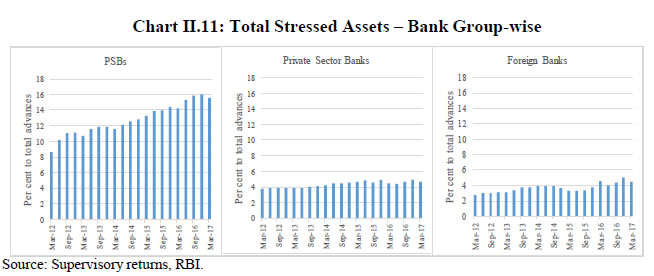

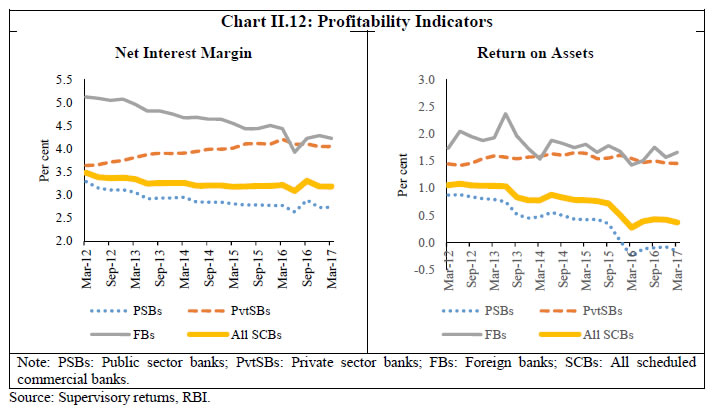

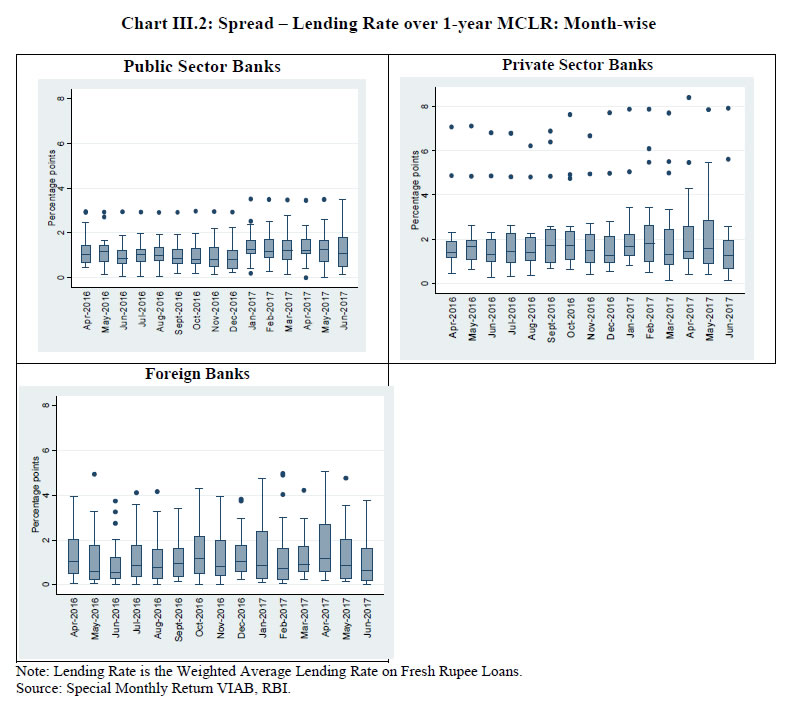

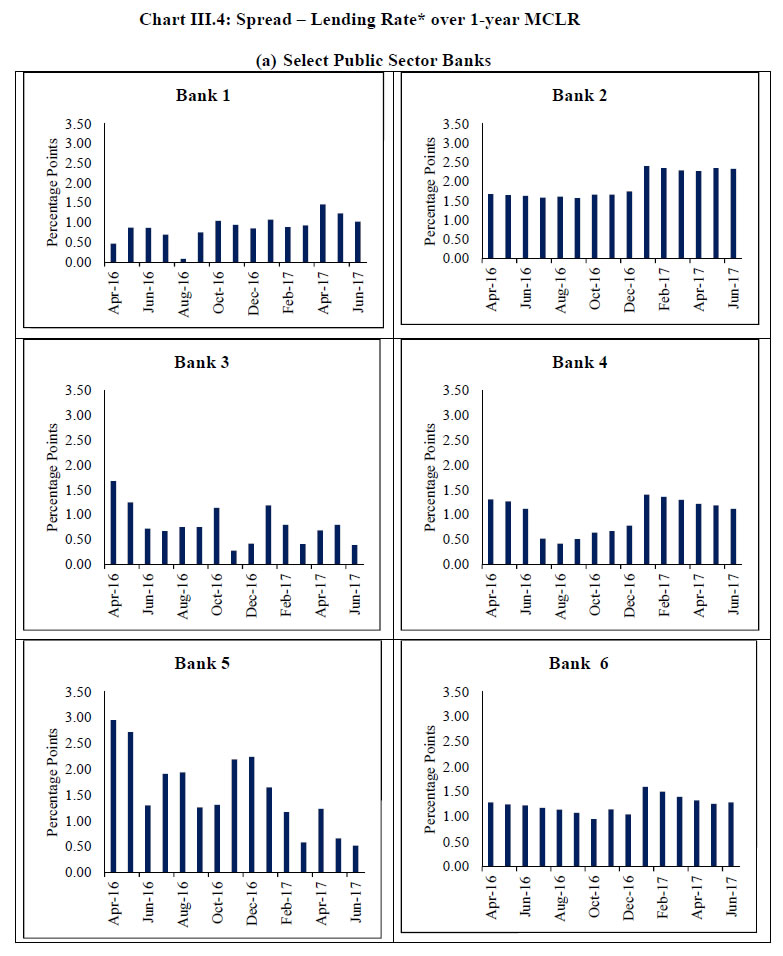

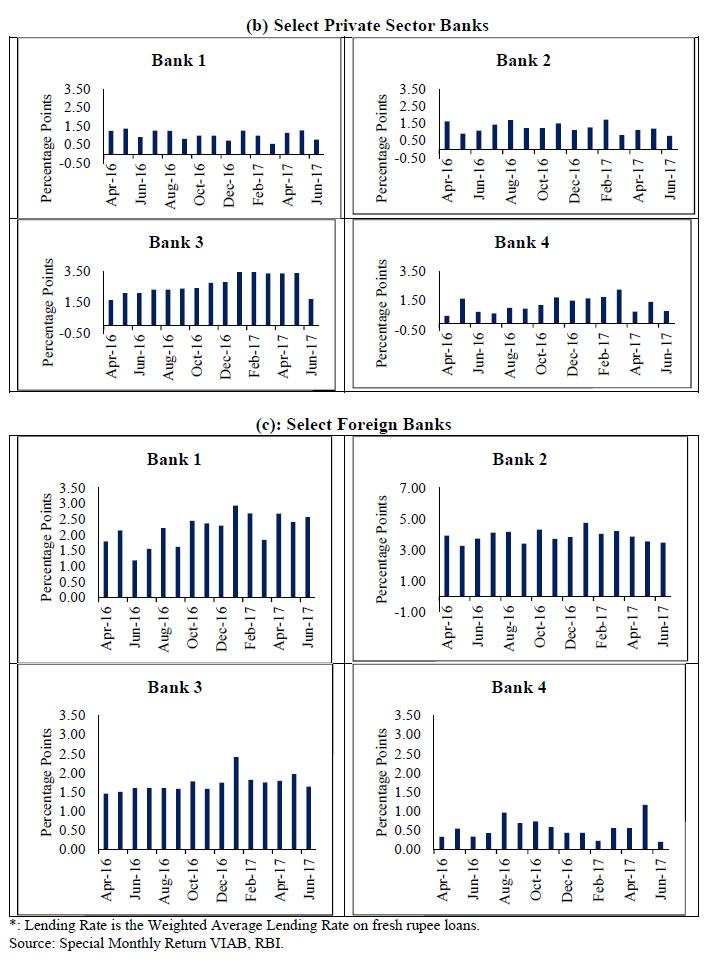

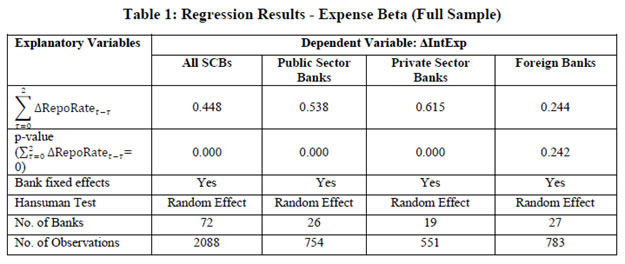

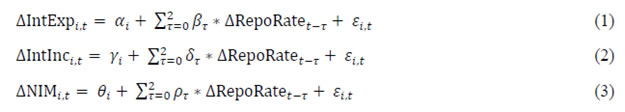

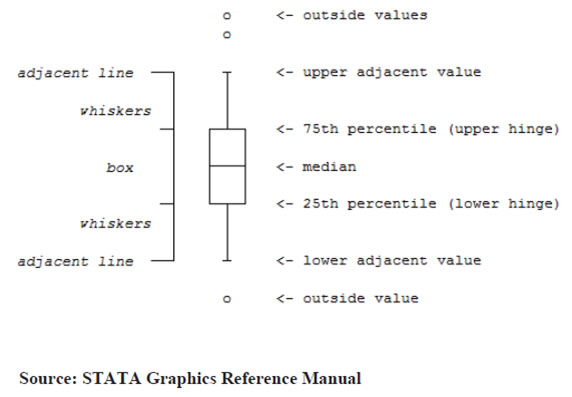

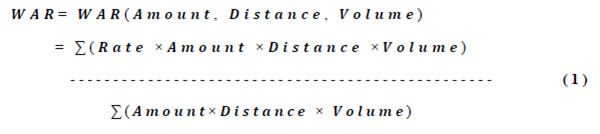

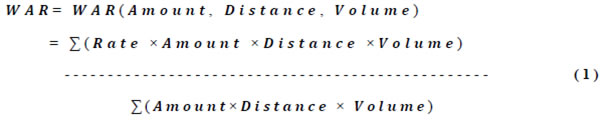

I.9 The Study Group was required to submit the report within two months (Annex I.1). Acknowledgements I.10 The Study Group expresses its sincere gratitude to Dr. Viral V. Acharya, Deputy Governor, for giving it an opportunity to work on the critical issue of MCLR as also for sharing his perspectives on the challenges to transmission under the MCLR regime and the evolving benchmark related reforms internationally. The Study Group also thanks Dr. M.D Patra, Executive Director, for his continuous guidance, which helped the Study Group to understand the transmission related challenges in the conduct of monetary policy in India. I.11 The Secretariat of the Study Group comprised three officials of the Monetary Policy Department (MPD), viz., Shri Sitikantha Pattanaik, Director, Shri Muneesh Kapur, Director and Shri A.K. Mitra, Director. I.12 The Study Group is appreciative of the feedback it received from the representatives of select banks with whom the Study Group held discussions on August 22, 2017 (Annex I.2). I.13 The Study Group benefitted in the form of comments/suggestions received from Dr. D.P. Rath, Adviser, MPD; Shri K. Rajkumar, Adviser, MPD; Dr. Praggya Das, Director, MPD; Dr. Nishita Raje, Director, Department of Banking Regulation (DBR); Shri P.K.Seth, General Manager, DBR; Shri Indranil Chakraborty, General Manager, Financial Stability Unit; Shri S.R. Pattanaik, General Manager, Department of Banking Supervision; and Shri Manoj Kumar, Deputy General Manager, Financial Markets Regulation Department. I.14 The Study Group wishes to place on record its deep appreciation for the resource persons from MPD – Shri S.M. Lokare, Assistant Adviser; Shri Rajesh Kavediya, Assistant Adviser; Dr. Harendra Behera, Assistant Adviser; Shri Joice John, Assistant Adviser; and Smt. Abhilasha, Assistant Adviser – who worked on specific aspects covered in the report. The Study Group also thankfully acknowledges the administrative and data-related support provided by Smt. Rita Maheshwari, Manager; Shri M.H. Ahuja, Assistant Manager; Smt. S.R. Apte, Senior Special Assistant; Smt. G.S. Parab, Senior Special Assistant; Shri P.V. Khadye, Senior Special Assistant; and Shri Nilesh Dalal, Assistant. I.15 The Report is organised in five chapters. Chapter II examines whether the MCLR has achieved the objective for which it was introduced. The performance of the base rate system is also assessed in this Chapter. Chapter III looks into the practices followed by banks for fixing the spread over the base rate/MCLR. Chapter IV explores market rates as the possible candidates for an external benchmark for pricing of floating rate loans. Chapter V sets out the recommendations of the Group for strengthening the monetary transmission. Chapter II I. Introduction II.1 In India, banks are the main conduits through which monetary impulses are transmitted to the real economy. Hence, it has been the endeavour of the Reserve Bank to strengthen the monetary transmission by focussing on the design of the lending interest rates of the banking system. It was in keeping with this that the Reserve Bank introduced the base rate system in July 2010, which was replaced by the marginal cost of funds based lending rate (MCLR) system in April 2016. This chapter undertakes a detailed review of the working of the base rate and the MCLR systems with a view to (i) assessing how monetary transmission has worked under these two regimes; and (ii) understanding the various factors that impede the monetary transmission. II. Banks’ Lending Rate Systems since the Early 1990s: An Overview Prime Lending Rate (PLR) System II.2 After the introduction of the financial sector reforms in the early 1990s, the Reserve Bank initiated various measures to progressively deregulate the interest rates – both deposit and lending rates. In a major initiative in October 1994, the Reserve Bank deregulated lending rates for credit limits over Rs.2 lakh. Banks were also required to declare their prime lending rates (PLR), i.e., the interest rate charged for the most creditworthy borrowers. The PLR was to be computed taking into account factors such as cost of funds and transaction costs, and was expected to act as a floor for lending above Rs.2 lakh. The experience with the working of the PLR system, however, was not satisfactory mainly for two reasons: (i) both the PLR and the spread charged over the PLR varied widely across banks; and (ii) the PLRs of banks were rigid and inflexible in relation to the overall direction of interest rates in the economy. Benchmark Prime Lending Rate (BPLR) System II.3 In order to improve transparency and ensure appropriate pricing of loans, the Reserve Bank advised banks in April 2003 to announce Benchmark PLRs (BPLRs). Banks were required to compute BPLRs taking into account the cost of funds, operational costs, minimum margin to cover regulatory requirements (provisioning and capital charge), and profit margin. The BPLR system also fell short of its original intent of enhancing transparency and serving as the reference rate for pricing of loan products. The transparency aspect, in particular, was hit by the fact that a large part of the lending actually took place at interest rates below the announced BPLRs. The share of sub-BPLR lending was as high as 77 per cent in September 2008, concentrated at long-term tenors (above three years), rendering it difficult to assess the transmission of policy rate changes of the Reserve Bank to lending rates of banks. The residential housing loans and the consumer durable loans were outside the purview of the BPLR. As such, sub-BPLR lending became a major distortion in terms of cross-subsidisation across borrower categories. The Base Rate System II.4 The drawbacks of the BPLR system called for a further refinement of the lending rate system and the base rate system was introduced in July 2010. Under this framework, each bank was required to announce its base rate, taking into account, inter alia, the costs of borrowed funds (Table II.1). The base rate was to be the minimum rate for all loans, except for some specified categories1. The actual lending rate charged to the borrowers was to be the base rate plus borrower-specific charges. The base rate system, with a link to the banks’ cost of funds, was expected to facilitate better pricing of loans, enhance transparency in lending rates and improve the assessment of the transmission of monetary policy. In practice, flexibility accorded to banks in the determination of cost of funds – average, marginal or blended cost – caused opacity in the determination of lending rates by banks and clouded an accurate assessment of the speed and strength of the transmission. Moreover, the discrimination in the pricing of credit between the new and old customers continued, as banks often adjusted the spread over the base rate to benefit the new borrowers. Marginal Cost of Funds based Lending Rate (MCLR) System II.5 The weaknesses and rigidities observed with the transmission under the base rate system were intended to be addressed through marginal cost of funds based lending rate (MCLR) system for new loans, effective April 1, 2016. The base rate system, however, was expected to be in operation concomitantly for the loans already contracted, pending their maturity or a shift to the MCLR system at mutually agreeable terms between the bank and the borrower. The parallel operation of the MCLR and the base rate systems has considerably impacted the transmission in respect of the outstanding loans linked to the base rate as detailed later in this report. II.6 The MCLR consists of four components: (a) marginal cost of funds [marginal cost of borrowings (comprising deposits and other borrowings) and return on net worth]; (b) negative carry on account of cash reserve ratio (CRR); (c) operating costs; and (d) term premium (Table II.1). Under the MCLR system, banks are required to determine their benchmark lending rates linked to their marginal cost of funds [unlike the base rate system where banks had the discretion to choose between the average cost or the marginal cost (or blended cost) of funds]. As such, lending rates were expected to be more sensitive to the changes in the policy rate under the MCLR system vis-à-vis its predecessor (the base rate). The MCLR plus spread is the actual lending rate charged to a borrower. The spread comprises only two components, viz., business strategy and credit risk premium. III. Transmission under the Base Rate and the MCLR Systems: An Analysis II.7 The MCLR regime has been in operation for almost 18 months and the transmission under the system has, like the earlier systems, remained below expectations. The extent and pace of reduction in MCLRs have been uneven since April 2016, and a large part of the observed transmission was due to the demonetisation-induced surge in the balances under current and savings accounts (CASA). While the transmission to interest rates on fresh rupee loans has been significant, it has been partial to existing loans (both at the base rate and outstanding MCLR) (Table II.2 and Chart II.1). Fresh Rupee Loans

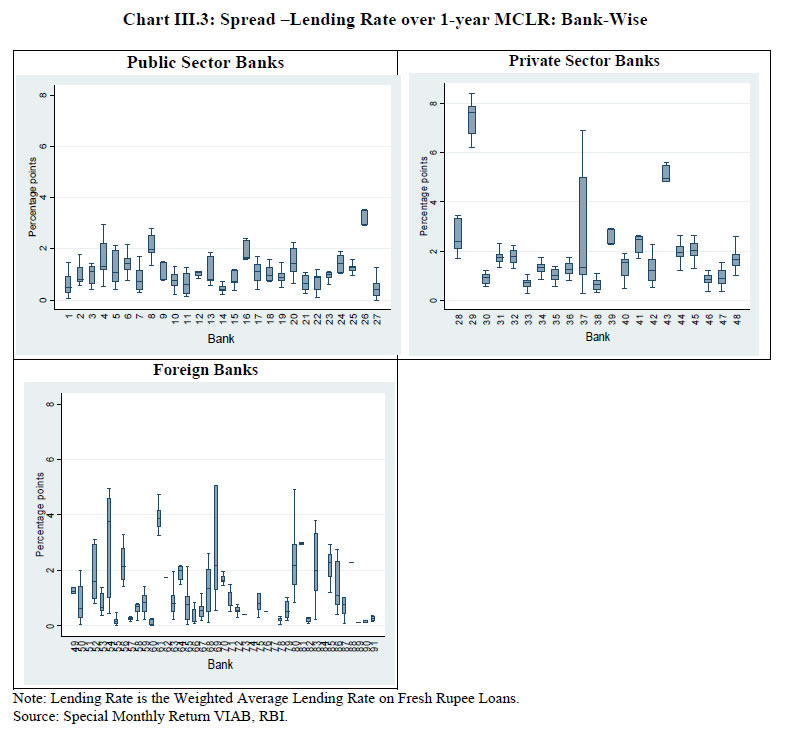

Outstanding Rupee Loans II.8 The transmission to outstanding rupee loans was significantly lower than the policy rate. As against the cumulative policy rate cut of 200 bps during December 2014 and August 2017, the weighted average lending rate (WALR) declined by 125 bps, of which 50 bps reduction was post-demonetisation. The transmission to outstanding rupee loans was also weak in relation to the reduction of 195 bps in the weighted average term deposit interest rate and notwithstanding a significant increase in low cost CASA deposits (Box II.1).

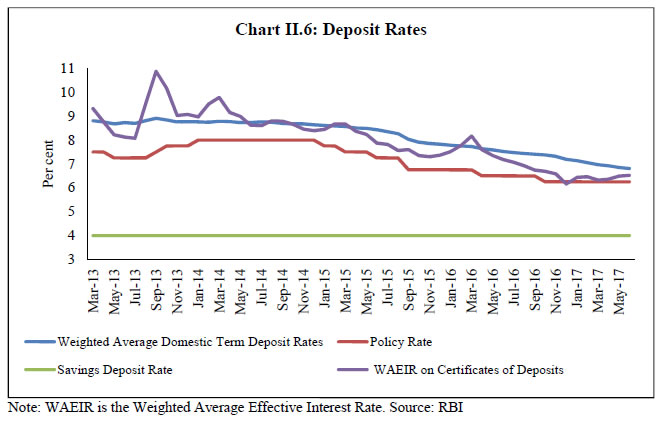

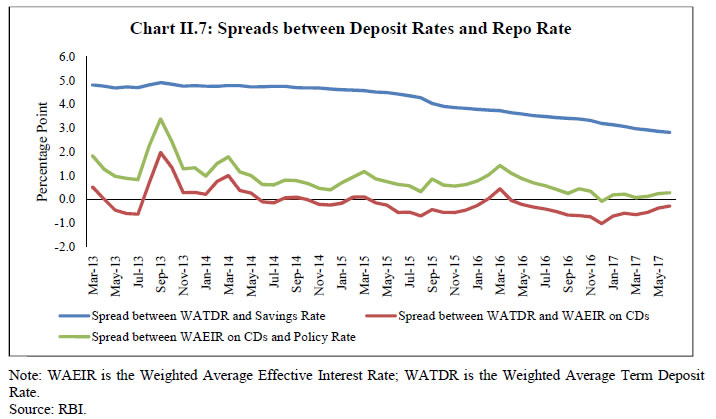

Transmission: Bank Group-wise II.9 The transmission was uneven across bank groups. The transmission to the WALR on outstanding rupee loans was relatively better in the case of private sector banks vis-à-vis public sector banks and foreign banks (Table II.3). Transmission: Borrowing Categories-wise II.10 The extent of transmission was also asymmetric across sectors (Table II.4). The decline in the WALR on outstanding loans during December 2014-June 2017 was greater for large industrial entities (despite higher NPAs) vis-à-vis retail housing and retail vehicle loans. Even in an environment of easy monetary policy, interest rates on credit cards increased by almost 100 bps, touching almost 40 per cent per annum. Transmission: Monetary Policy Cycles II.11 The transmission to lending rates over different monetary policy cycles was asymmetric. It was somewhat higher during the tightening phase of monetary policy and lower during the easing phase, irrespective of the interest rate regime (Table II.5). II.12 The above analysis suggests that the transmission to fresh rupee loans was significant, especially post demonetisation. However, the transmission to outstanding rupee loans, especially base rate portfolio, was significantly lower. The transmission was uneven across bank groups and sectors. It was also asymmetric across monetary policy cycles. Working of the Base Rate System: Some Concerns II.13 The Study Group conducted a study of the methodology of the base rate calculation of a few major banks. The study revealed that the banks took recourse to many ad hoc adjustments in the methodology, which either inflated the base rate or prevented the base rate from falling in line with the cost of funds (Box II.2). II.14 Even 15 months after the introduction of the MCLR regime, a sizable part of loans (around 30 per cent) is still at the base rate. The progress of migration of borrowers from the base rate system to the MCLR regime has been tardy (Box II.3). Recommendations II.15 The lower transmission from the policy rate to the base rate loan portfolio was mainly due to the reason that banks followed different methods to calculate the base rate. Banks, therefore, could be advised to re-calculate the base rate immediately by removing/readjusting arbitrary and entirely discretionary components added to the formula. It needs to be ensured that the calculation of the base rate is not compromised in any way. The methodology adopted by banks should be subject to a regular supervisory review. II.16 In the absence of any sunset clause on the base rate, banks have been quite slow in migrating their existing customers to the MCLR regime. Most of the base rate customers are retail/SME borrowers. Hence, the banking sector’s weak pass-through to the base rate is turning out to be deleterious to the retail/SME borrowers in an easy monetary cycle. To address this concern, besides immediate recalculation of base rates as recommended in paragraph II.15, banks may be advised to allow existing borrowers to migrate to the MCLR if they so choose to do without any conversion fee or any other charges for switchover on mutually agreed terms. However, after the adoption of an external benchmark starting from April 1, 2018 as recommended by the Study Group (refer paras IV.43 - IV.45), banks may be advised to migrate all existing benchmark prime lending rate (BPLR)/base rate/MCLR borrowers to the new benchmark without any conversion fee or any other charges for switchover on mutually agreed terms within one year from the introduction of the external benchmark, i.e., by end-March 2019. Working of the MCLR System: Some Concerns II.17 The implementation of the MCLR regime at the bank level raises some concerns (Box II.4). MCLR and Lending Rates II.18 Different components of MCLR vary across banks reflecting: (i) differences in the composition and maturity profile of their liabilities – current, savings and time deposits - and the extent of reliance on retail vis-à-vis wholesale customers, which has a bearing on the cost of funds; (ii) divergences in the operating cost arising out of differences in the use of technology, quality of human capital and the geographical spread of bank branches; and (iii) the return on net worth expected by banks. II.19 What matters for monetary policy is the transmission from the policy rate to actual lending rates, which consist of MCLR and the spread charged over the MCLR, as alluded to earlier. Thus, the transmission to MCLRs may not necessarily lead to transmission to lending rates, if banks make offsetting adjustments in spreads charged along with the changes in their MCLRs. It is noteworthy that in the case of fresh loans, spreads charged by SCBs narrowed between April 2016 and June 2017. However, in the case of outstanding loans, spreads widened, suggesting that banks adjusted the spreads charged over MCLRs upwards such that the reduction in lending rates was lower than that in MCLRs. This was mainly on account of widening of spreads by public sector banks and foreign banks, while spreads charged by private banks declined (Chart II.2). Thus, for assessing the effectiveness of monetary transmission, it is important to study the MCLR and the spreads charged separately. II.20 While the practices followed by banks with regard to setting of spreads over the base rate/MCLR are detailed in the next chapter, the main factors that appeared to have impeded monetary transmission are detailed in the following section. IV. Factors Impeding Monetary Transmission II.21 A number of factors impede a fuller and speedier pass-through from the Reserve Bank’s policy repo rate to banks’ deposit and lending rates. Maturity Profile of Deposits and Loans II.22 As at end-March 2016, more than half of the deposits of commercial banks were in a maturity bucket of ‘one year and above’ and almost 20 per cent of the deposits were in a maturity bucket of ‘five years and above’ (Chart II.3)2. During the easy cycle of monetary policy, banks reduced their deposits rates on new deposits, which lowered the marginal cost of funds. However, more than 50 per cent of deposits with a maturity of one year and above continued to attract high interest rates. The high cost and long maturity deposits kept the average cost of deposits elevated, which, in turn, appeared to have constrained banks from lowering their lending interest rates. The constraint was felt more acutely by public sector and private sector banks as they held more than 20 per cent of their deposits with maturity five years and above; foreign banks held only a negligible share of their deposits with maturity of five years and above. II.23 The rigidity in interest rate on savings accounts (detailed in the followingsection) observed during 2011-17 was another major factor that kept the average (asalso marginal) cost of funds high during the easy phase and low during the tight phase. II.24 While almost all bank deposits were at fixed rates, most of banks’ loans (almost 80 per cent) were at floating rates. The maturity profile of loans and advances extended by public sector and private sector banks was skewed towards longer-term loans (one year and more), while that of foreign banks was towards shorter loans (one year and less) (Chart II.4). The asymmetry in the interest rate setting (fixed for deposits and largely floating for loans) combined with a substantial part of deposits in longer maturities appeared to have constrained banks from quickly transmitting the policy rate cuts to their lending rates, especially on past loans. II.25 Base rate-linked loans currently account for around 30 per cent of the outstanding bank credit, with wide variation across bank groups (negligible in the case of foreign banks and 41 per cent in the case of public sector banks). The base rate loan portfolio also varied widely within the same bank group (Table II.6). A sizable proportion of loans at the base rate combined with the slow pace of reduction in the base rate impaired the pace of monetary transmission to interest rates on outstanding loans. II.26 The transmission to outstanding rupee loans was also adversely impacted as one fifth of outstanding bank credit was at fixed rates at end-June 2017, with wide dispersion across bank groups and also within bank groups (Table II.7). The proportion of fixed rate loans was around 35 per cent in the case of foreign banks and relatively moderate (15 per cent) in the case of public sector banks. Fixed rate loans weakened the overall transmission of monetary policy. II.27 Even in the case of floating rate loans, the benefit of the realised reduction in the MCLR was available mostly to fresh rupee loans after a lag, of about one year, since interest rates on floating rate loans were reset at fixed periodicity, which is typically one year. This was one of the reasons that the reduction in WALR on outstanding rupee loans between April 2016 and August 2017 was only 61 bps vis-à-vis a reduction of almost 100 bps in the one-year median MCLR rate. Recommendation II.28 The reset clause, which is typically one year, impedes monetary transmission as the pass-through of monetary policy changes to existing floating rate loans is delayed. The Study Group, therefore, recommends that the periodicity of resetting the interest rates by banks on all floating rate loans, retail as well as corporate, be reduced from once in a year to once in a quarter. Rigidity in Saving Deposit Rates II.29 Saving deposits constitute more than three-fourth of CASA balances of commercial banks (Chart II.5). II.30 In the run up to the deregulation of savings deposit interest rates in India in 2011, banks had expressed apprehension that the deregulation would lead to a rate war among banks. In contrast, however, interest rates on saving deposits of major banks remained sticky at 4 per cent (until very recently), barring some minor adjustments by some smaller and private and foreign banks and some new banks. This is despite the fact that monetary policy switched from a tightening mode to an accommodative mode twice over the period and term deposit interest rates moved in either direction (Chart II.6). Between October 2011 and June 2017, 11 SCBs, with a market share of 4.1 per cent in aggregate deposits, increased their saving deposit rates in a range of 10 bps to 300 bps. II.31 It was only on July 31, 2017 that the State Bank of India (SBI), the largest bank in the country, slashed interest rate on saving deposits by 50 bps to 3.5 per cent on balances of Rs.1 crore and below. The decline in the share of CASA balances in the post-March 2017 period (reversing a part of the sharp rise witnessed in November- December 2016, due to demonetisation) (see Box II.1) pushed up banks’ cost of funds and 'would have necessitated an increase in MCLRs. However, this option was not easy given the low credit offtake. Hence, some banks, led by the SBI, decided to reduce the interest rate on saving deposits. In all, 28 banks, accounting for a market share of 82.8 per cent in aggregate deposits, reduced their savings deposit rates in a range of 25 bps to 150 bps during August–September 2017. Despite the recent reduction in the saving deposit interest rate by some banks, the spreads between savings deposit interest rate on the one hand, and term deposit interest rates on the other, have remained wide (Chart II.7). II.32 The observed rigidity in the interest rate on saving deposits can be due to the following factors. First, saving deposit balances are almost 30 per cent of banks’ total deposits. Therefore, any change in the interest rate on these balances is applicable to all outstanding balances, which has an immediate and sizable impact on banks’ cost of funds. In contrast, changes in interest rates on time deposits impact only incremental deposits contracted at the new rate, the impact of which on the overall cost of funds is limited. Hence, banks chose not to raise interest rate on saving deposits during the tightening phase of monetary policy. II.33 Second, some banks with whom the Study Group held discussions indicated that saving deposits entail high operating costs. Given the higher overall costs, most banks chose not to increase their interest rates on saving deposits during the tightening phase of monetary policy (2011-12). Since banks did not increase the interest rate on saving deposits during the tightening phase, it appeared that there was reluctance by banks to reduce saving deposit rates during the easing phase of monetary policy. II.34 It is intriguing that saving deposit interest rates remained sticky even when the policy repo rate and banks’ own term deposit interest rates moved in either direction significantly after deregulation of the saving deposit interest rate in October 2011. On the one hand, banks appear reluctant to reduce interest rate on saving deposits as they face competition from mutual funds and small savings. On the other hand, banks chose not to raise saving deposit interest rates when all other interest rates in the system moved up significantly during 2011-12. Had banks raised saving deposit interest rates during the tight monetary policy phase, it would not have been so difficult to reduce the interest rates on such deposits during the easy monetary policy cycle. That the saving deposits carry high operational cost cannot be a good enough reason for banks not to change interest rate on such deposits in line with other interest rates. This is not to suggest that the saving deposit interest rates need to be changed to the same extent as term deposit interest rates. However, there is certainly a strong case for adjusting such rates regularly in line with other interest rates in the system. Competitive Pressures from other Financial Saving Instruments II.35 While modulating their deposit rates in response to monetary policy signals, commercial banks also take into account returns available to depositors on alternative instruments of financial savings. In particular, banks in India take into account interest rates on small saving schemes and returns available on mutual fund schemes. II.36 Small savings by the government compete directly with bank deposits. Although the government has been periodically adjusting downwards the interest rates on these instruments since April 2016, these still remain well above those being offered by the banking system. Interest rates on small saving schemes also remain higher than the rates based on the formula indicated by the Government in its press release of February 16, 2016 (Table II.8). The tax adjusted rate of return on select small savings schemes (viz., 5-year time deposits, public provident fund, national savings certificates and senior citizen’s savings scheme) are even higher. A large interest rate differential in favour of small savings can lead to a significant migration of deposits away from banks, with an adverse impact on banks’ lending capacity. Hence, this appeared to have constrained banks from reducing their deposit interest rates in consonance with the changes in the monetary policy rate, especially during the easing phase of monetary policy. II.37 Mutual funds have recently emerged as a major source of competition to the banks for financial savings. Assets under management (AUM) of mutual funds grew at a (compound) rate of 18.3 per cent per annum during the 10-year period 2007-17, outpacing the growth of 15.3 per cent in bank deposits during the same period. As a result, assets under management of mutual funds as percentage of bank deposits (outstanding) increased in the recent period (Chart II.8). II.38 Funds mobilised under debt oriented schemes also increased sharply. During 2016-17, inflows under such schemes were about 20 per cent of incremental deposits mobilised by banks. The surge of inflows into mutual funds has continued in 2017-18 so far. Returns on mutual fund debt oriented schemes are generally higher than interest rates on bank deposits. II.39 The investor base of mutual funds is also becoming more broad-based3. There were 59 million accounts at end-July 2017. Of these, 48 million accounts related to the equity, equity-linked savings scheme (ELSS) and balanced schemes, with mostly retail investors. Individual investors (including high net worth individuals) accounted for almost one-half of total assets of the industry (48.1 per cent) as of July 2017 (Chart II.9). II.40 Banks face competition from mutual funds mainly from debt oriented and liquid schemes, especially because such schemes carry tax benefits. In the case of bank deposits (savings or fixed), interest income gets taxed at the applicable marginal slab tax rate of the depositor (the peak rate is 30 per cent at present). On the other hand, returns from the long-term debt funds (held for more than three years) are taxable at 20 per cent with indexation benefit and 10 per cent without indexation (again well below the peak marginal income tax rate of 30 per cent). II.41 Investments in banks’ fixed deposits with a lock-in period of 5 years as well as in the equity linked saving schemes (ELSS) of mutual funds enjoy tax benefits under Section 80C of the Income Tax Act. However, the overall tax benefits are loaded in favour of mutual funds. First, the lock-in period associated with the ELSS is lower (3 years) than that of bank deposits (5 years). Second, ELSS returns are tax free, while interest income on deposits is taxable at the applicable tax slab in the hands of the depositor. II.42 In the case of fixed deposits, there is a penalty associated with premature withdrawal. Mutual funds, on the other hand, offer higher liquidity and exit load is typically charged only for withdrawal under a year (most liquid funds do not charge an exit load). Thus, mutual fund schemes are also liquid like bank deposits. II.43 Falling interest rates on bank deposits and tax benefits in favour of mutual funds have made mutual fund investments highly attractive relative to bank deposits. This appeared to have constrained banks from reducing their interest rates on fresh deposits, blunting even the first leg of the transmission (from the policy repo rate to bank deposit rates). The weaker first stage transmission, in conjunction with other rigidities noted in this chapter, then dampens the second leg of the transmission (from the bank funding costs to lending rates). II.44 A level-playing field for all the competing financial saving instruments is necessary for enhanced monetary transmission. Any tax benefit in favour of a particular saving instrument distorts the risk-return perception of a saver, which is not conducive for developing a balanced and diversified financial system. Deterioration in Asset Quality of Banks II.45 There has been a significant deterioration in the asset quality of banks in recent years. Gross non-performing assets (NPAs) of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) increased more than three times from 2.9 per cent (of gross advances) in March 2012 to 9.6 per cent in March 2017. Total stressed assets (i.e., NPAs plus restructured assets) increased sharply from 7.5 per cent to 12.0 per cent over the same period (Chart II.10). II.46 The increase in stressed assets, however, was largely concentrated in public sector banks (Chart II.11). II.47 Since a sharp deterioration in the asset quality has implications for their net interest income and profitability, banks could be expected to be reluctant to fully pass on the reduction in their MCLRs to their lending rates. Significantly, NIMs of public sector banks have declined marginally since 2012, reflecting rising NPAs. NIMs of private sector banks, on the other hand, have risen, suggesting more pricing power. Although NIMs of foreign banks have declined – albeit from a fairly high level – they are still the highest among all bank groups. Return on assets (RoA) of PSBs has declined, reflecting higher provisioning/write-offs against bad assets. On the other hand, RoA of private sector banks and foreign banks has remained broadly stable over past six years (Chart II.12). Net Interest Margins and Monetary Policy Stance II.48 In principle, fluctuations in interest rates are expected to have some impact on banks’ net interest income, given the maturity and interest rate mismatches. Cross-country evidence, however, indicates that banks’ net interest margins are impervious to interest rate cycles. This appears to be true for both conventional and unconventional monetary policies. Aggregate net interest margins in the US have been near-constant for the past six decades (1955-2013), despite substantial maturity mismatch and wide variation in interest rates4. This could be due to banks' market power in deposit markets, which allows banks to pay deposit rates that are low and relatively insensitive to interest rate changes. Banks hedge these liabilities by investing in long-term assets, whose interest payments are also relatively insensitive to interest rate changes. II.49 Turning to the experience with the unconventional monetary policies, policy interest rates have been close to zero and even negative in some euro area countries and Japan over the last few years. In these countries, the available evidence, albeit limited, indicates that despite negative interest rates, banks have been able to largely protect their NIMs5. In the euro area and Japan, NIMs have declined somewhat, though not significantly. In Denmark and Sweden, margins have remained stable, and in Switzerland they even increased somewhat. Although deposit rates have been largely sticky in these countries, banks have been able to maintain their NIMs due to a variety of factors: ‘tiering system’ by the respective central banks for the remuneration of reserve balances (Japan and Switzerland); incomplete pass-through of negative rates to lending rates (Denmark); a counterintuitive increase (although temporary) in mortgage rates (Switzerland); and, more generally, cheaper wholesale funding. II.50 Regression analysis indicates that banks in India, like those in other countries, are able to insulate their net interest margins from the monetary policy actions (Annex II.1). The following key findings emerged from the empirical analysis.