IST,

IST,

Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit

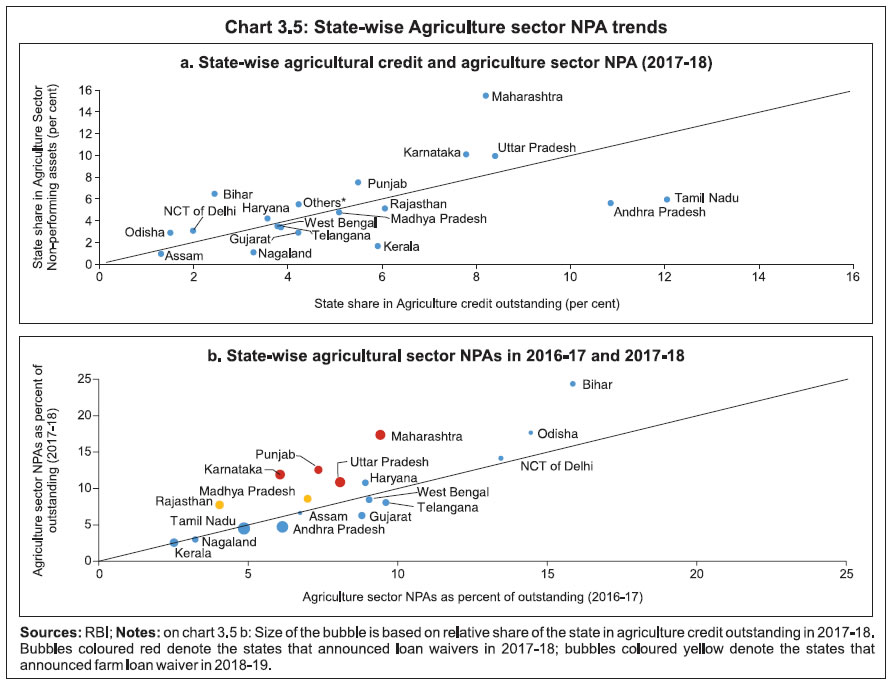

The Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit was made possible with the support of individuals and organizations. The Internal Working Group (IWG) would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. K.L. Prasad, Economics Statistics Advisor, Ministry of Agriculture, GoI; Shri. Adikesavan. S, CGM, State Bank of India; Shri Amresh Ranjan, General Manager, RBI; Dr. Nirupam Mehrotra, General Manager, NABARD; Dr. Purvi Mehta, South Asia Head, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; Shri Jatin Singh, MD, SKYMET and Shri Sudhakar Manda, Head of Remote Sensing, SKYMET for their valuable inputs and suggestions. In order to have an international perspective on agricultural issues, the team consisting of officials from RBI and NABARD visited China and held meetings with Mr. Hu Beihai, CEO, Bank of China and senior executives and officials of Agriculture Development Bank of China (ADBC), State Agriculture Credit Guarantee Co. Ltd. and Bank of China Fullerton Community. The working group would like to acknowledge the support provided by Bank of China (India Operations) officials Shri A.G. Ray, Chief Compliance Officer; Mr. Qian Wei, Chief Risk Officer; Mr. Xu Min, Chief Technology Officer; Mr. Ling Sheng, VP, for coordinating and organizing the meetings scheduled at China. The Working Group would like to thank all Regional offices of the Reserve Bank of India for the studies conducted and inputs provided within due timelines. The IWG also acknowledges the valuable support provided by Ms. Ritika Juneja, Consultant, ICRIER. The Working Group would like to commend Shri Ashish Jaiswal, Deputy General Manager and Shri Yogendra Kumar, Manager, both from Financial Inclusion and Development Department (FIDD) for their efforts towards data analysis and inputs. The Working Group also acknowledges the research work and analytical inputs of Shri Rahul Agarwal and Smt. D. Suganthi, Managers from research team of Department of Economic and Policy Research (DEPR). Further, inputs received from Shri. Prasanna Rao, MD and his team from Arya Collateral Warehousing Services Pvt. Ltd and Shri Amit Salunkhe from Cropin Technologies were also useful for the report. The IWG was ably supported by the Secretariat team from FIDD led by Smt. Nengneikim Guite, General Manager and assisted by Smt. Vandana Maheshwari, Deputy General Manager, Smt. M.P. Kotwal, Assistant General Manager, Shri Madhav Joshi, Dr. V. Pradeep Chandra and Shri Ashish Ambade, Managers. Agriculture is a key sector of Indian economy in view of its contribution to employment and GDP. Agricultural credit plays a vital role in farm sector development and facilitates adoption of new technologies. However, any amount of credit even at the most reasonable rates cannot guarantee higher productivity or adequate income among the farmers, as the success depends upon many other supporting factors including the availability of agricultural inputs, services and remunerative markets for the products. The agricultural credit policies designed and implemented in India are mainly supply driven through targeted ground level credit, interest subvention scheme and directed lending by way of regulatory prescription under Priority Sector Lending guidelines. These policies along with other policy interventions at the level of Government and RBI have yielded commendable results in the field of agricultural credit. However, agricultural sector still faces challenges such as lack of capital formation, regional disparity, dependence of farmers especially small and marginal farmers, tenant farmers, landless labourers and share croppers on non-institutional sources of credit at significantly higher rates, non-realization of the fair price for agricultural produce causing farmers’ distress and farm loan waivers impacting credit culture and weakening state finances. The Internal Working Group in this report has highlighted the findings supported by data and research and recommended suitable measures to address the issues being faced by farmers in accessing agricultural credit. I hope that this report will help in addressing the gaps in credit delivery to agriculture sector. M.K.Jain The agriculture sector is an important component of the Indian economy as it provides livelihood to a large section of the population. According to Census 2011, out of the total workers of 481.7 million, there are 118.7 million cultivators and 144.3 million agricultural labourers, which means approximately 55 per cent of the total workers were employed in agriculture and allied sector. However, the percentage share of workers engaged in agriculture sector has been declining. As per Labour Bureau Report 2015-16, 46.1 per cent of the working population was employed in agriculture and allied sector. Further, as per an ILO estimate1 employment in agriculture sector as percentage of the total employment was approximately 44 per cent in the year 2018. 2. As per Agriculture Census 2015-16, the total number of operational holdings in the country was 146 million and total operated area was 157.14 million hectares in 2015-16. The small and marginal holdings taken together (0.00-2.00 ha) constituted 86.21 per cent, while their share in the operated area stood at 47.34 per cent in 2015-16. The average size of land holding in 2015-16 was 1.08 hectare. 3. Agriculture plays a significant role in the development of the Indian economy. However, the contribution of agriculture to GDP has gone down from 52 per cent in the 1950s to 30 per cent in the1990s and further below 20 per cent from 2010 onwards2. In 2018-19, the share of Agriculture & Allied GVA in overall GVA at 2011-12 prices was 14.4 per cent3 and at current prices was 16.14 per cent4. 4. Indian agriculture and allied sector broadly covers four activities, viz., crop, livestock, forestry and fisheries. To stimulate the productivity of these activities, Government of India (GoI) has, from time to time, given policy thrusts which led to the various agricultural revolutions, viz., green revolution in cereal production (late 1960s-early 1980s) which was succeeded by the white revolution in milk production (starting in the 1970s), the gene revolution in cotton production, (in early 2000) and the blue revolution which focused on increasing fisheries production and productivity (1973-2002). As a result, the agriculture sector has not only become self-sufficient but has emerged as the net exporter of several agricultural commodities like rice, marine products, cotton etc. 5. Such a phenomenal achievement would not have been possible without the agricultural credit related policy interventions by GoI and RBI. Realising the importance of institutional credit in fostering the growth and development of the agriculture sector, the All India Rural Credit Survey Committee (AIRCSC, 1951-54) had laid the foundation of the institutional framework to establish a sound credit delivery system for financing agriculture and allied activities. Till the end of the 1960s cooperative structure had assumed the responsibility of providing production credit to the farmers. With the objective of imposing social control, commercial banks were nationalised in 1969 and 1980. Further, in 1976, RRBs were set up as alternative agencies to provide rural credit. These developments brought in a sea change in the flow of institutional credit to the farm sector. As a consequence, the farmers’ credit requirements were increasingly met by the formal institutional sources. Gradually the country moved towards a multi-agency approach to meet the credit needs of the farmers. 6. The National Credit Council, in its meeting held in July 1968, emphasised that commercial banks should increase their involvement in the financing of priority sectors, viz., agriculture and small-scale industries. The description of the priority sectors was later formalised in 1972 based on the report submitted by the Informal Study Group on Statistics relating to advances to the Priority Sectors constituted by the Reserve Bank in May 1971. Over the years the scope of priority sector lending has evolved to give greater focus to those segments of the population that have traditionally been neglected from accessing credit, thus making it a tool to address the problem of financial exclusion. The evolution of Priority Sector Lending Guidelines in agriculture is given in Annex 1. 7. The impact of the institutional framework put in place has largely leveraged the formal credit to the agriculture sector. From ₹37.71 billion in 19815 (approximately 16 per cent of the agricultural GDP in 1980-81), the SCBs’ outstanding advances to agriculture and allied activities have grown significantly to ₹13694.56 billion in 2017-18 which formed approximately 16 per cent of total bank credit, i.e. ₹86254.25 billion and approximately 51 per cent of Agriculture & Allied GVA at current prices. 8. Despite the impressive growth in the formal agricultural credit, there are several issues and challenges which are enumerated below: i. Credit Reach – As per the NAFIS Report 2016-17, the average loan taken by agricultural households indicated that 72 per cent of the credit requirement was met through institutional sources and 28 per cent from non-institutional sources. Further, in the absence of a proper legal framework and lack of records relating to their agricultural activity, tenant farmers/ share croppers/ oral lessees/ landless labourers face difficulty in accessing institutional credit. As per PSA Annual return (2015-16), only 41 per cent of small and marginal farmers could be covered by public and private sector banks. Besides these problems and challenges of accessibility in credit, the share of credit to allied activities i.e., livestock, forestry and fisheries was sub-optimal compared to its contribution to agricultural output. ii. Regional Disparity in Agricultural Credit – Some of the states are getting much higher share, as high as 10 per cent of total agricultural credit compared to other states getting as low as 0.5 per cent. Also, in some states, viz., Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, etc., bank credit was not proportionate to their share in agricultural output. iii. Loan Waiver - Loan waivers announced by state governments have affected the credit culture in the country with many borrowers withholding repayment, in anticipation of a loan waiver. This adversely affected the credit history of borrowers and their future prospects of availing fresh loan for agricultural purposes. This led to further deterioration of credit culture as evident from the high level of Gross NPA of 8.44 per cent as on March 31, 2019 in the agriculture sector. 9. To look into these issues, the Reserve Bank of India vide its Sixth Bi-Monthly Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting held during February 05-07, 2019 announced the setting up of an ‘Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit’ to understand the reasons for regional disparity and other agricultural credit related aspects and suggest workable solutions to address the constraints in accessing institutional agricultural credit. 10. In the first meeting of the Internal Working Group it was decided that the scope of the review should cover the following: i. Credit reach: institutional credit, measures and factors/drivers that influence reach ii. Cost effective and inclusive system: ease of credit and inclusiveness iii. Credit discipline: impact of loan waivers on state finances and agricultural credit 11. The report consists of five chapters: Chapter 1 discusses the reach of formal agricultural credit, Chapter 2 explains the policy measures for improving inclusiveness in the agriculture sector, Chapter 3 analyses the impact of farm loan waivers on state finances and agricultural credit, Chapter 4 provides a brief on the learnings during the interaction with four financial institutions in China and Chapter 5 summarises the recommendations of the IWG. Enabling policy environment and evolution of Indian banks led to the outreach of formal agricultural credit to the last mile to a great extent. An analytical presentation of the distribution of agricultural credit across states, however, highlights regional disparity, skewedness towards crop loan and inadequate credit allocation to allied activities. 1.1 Evolution of Agricultural Finance in India and Policy Milestones The institutional framework of agricultural finance was shaped by the overarching demands of the nation. The evolution of agricultural credit policies and milestones can be broadly categorised into three distinctive phases. 1.1.1 Phase 1 (1951 – 1969)

1.1.2 Phase 2 (1970-1990)

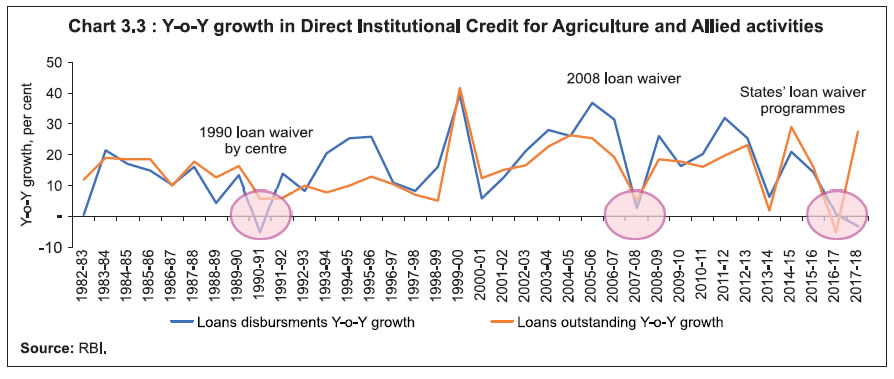

1.1.3 Phase 3 (1991 onwards) i. The economic reforms of the 1990s, started with the implementation of the first Narasimham Committee Report of 1991, emphasising financial soundness and operational efficiency of the financial sector – including that of rural financial institutions. The Reserve Bank of India gradually deregulated the interest rate regime to aid improvement in the operational efficiency of banks. ii. The first major nationwide farm loan waiver was announced in 1990 and the cost to the national exchequer was around ₹100 billion. iii. Pursuant to the 1995 Union Budget announcement, GoI established the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) with NABARD. RIDF was mainly meant for funding of rural infrastructure projects which in turn were supposed to deepen the credit absorption capacity in a state by giving loans to state governments and state-owned corporations. Scheduled commercial banks contribute to the corpus of the fund to the extent of their shortfall in achieving the priority sector lending target. iv. During 1992-93, NABARD started the pilot project on SHG-Bank Linkage programme - a partnership model involving SHGs, banks and NGOs. In the initial years, the scheme progressed slowly but picked up gradually. v. The Kisan Credit Card (KCC) was introduced as a financial product in 1998 to provide hassle free credit to farmers. vi. The Union Government introduced the Ground Level Credit (GLC) policy in year 2003-04. Under this policy, GoI announces GLC targets for agriculture and allied sector in the Union budget every year which banks are required to achieve during the financial year. These targets are set region-wise, agency-wise (SCBs, RRBs & Cooperative banks) and loan category wise (crop and term loan). vii. Another policy initiative, introduced in 2004–2005, was to double the volume of credit to agriculture over a period of three years and expand the reach of formal finance. viii. The year 2006 saw a host of developments. Pursuant to the budget announcement for 2006-07, the Union Government introduced the interest subvention scheme (ISS) for short term crop loans to enable farmers to avail farm credit at reduced interest rates. The Business Correspondents (BCs) and Business Facilitators (BFs) were rolled out for the first time by the Reserve Bank of India to further the cause of financial inclusion. NABARD introduced the Joint Liability Group (JLG) model, an extension of the earlier SHG model for reaching out to tenant farmers and share-croppers with access to credit. ix. Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme (ADWDRS), 2008 announced by the Union Government involved waiving institutional debt for small farmers and a one-time settlement opportunity with 25 per cent rebate to other farmers. This massive write-off of agricultural loans involving ₹525.166 billion was envisaged to provide relief to the persistent problem of farmers’ indebtedness and alleviate the financial pressure faced by the farmers. x. In 2009-10, the Government introduced the prompt repayment incentive (PRI) of 3 per cent under the ISS to bring down the effective rate of interest to 4 per cent to those farmers who repaid their loans on or before the due date to inculcate repayment habits. xi. In July 2012, the Priority Sector Lending (PSL) guidelines were revised by the Reserve Bank to widen the eligible activities. Again in April 20157, the guidelines were revamped based on the recommendations of the Internal Working Group (IWG). The salient features of the revamped PSL guidelines relating to agricultural sector are:

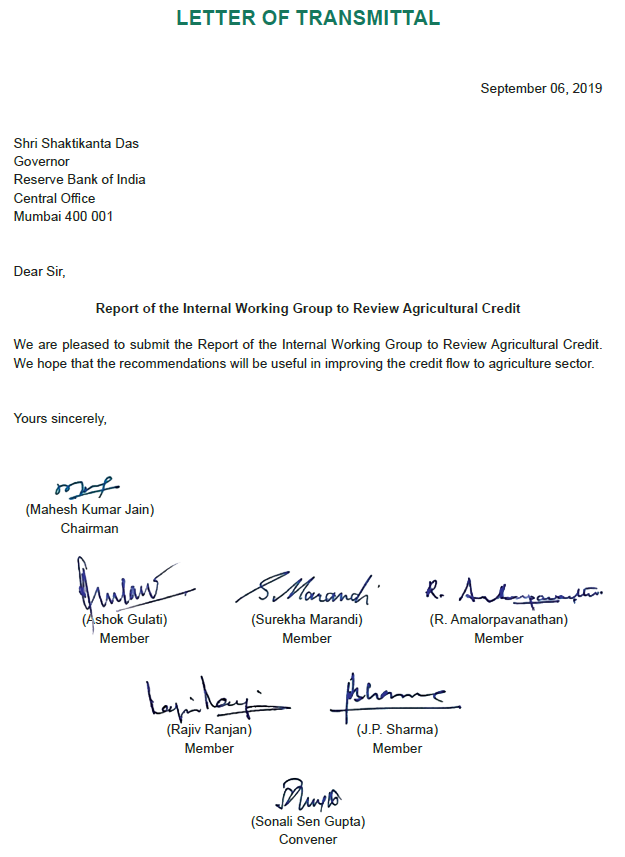

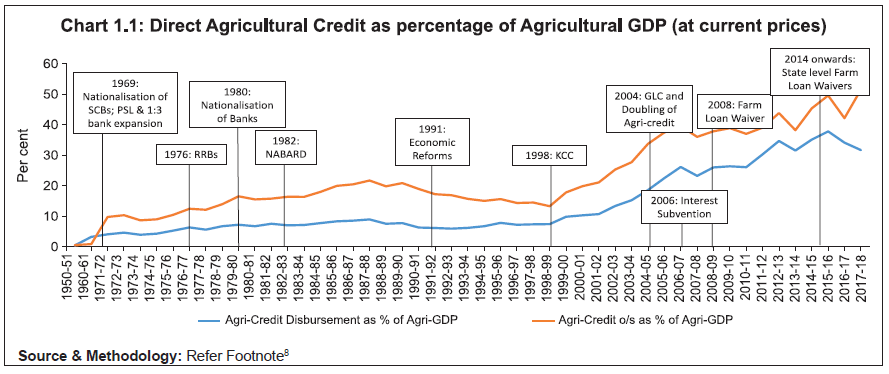

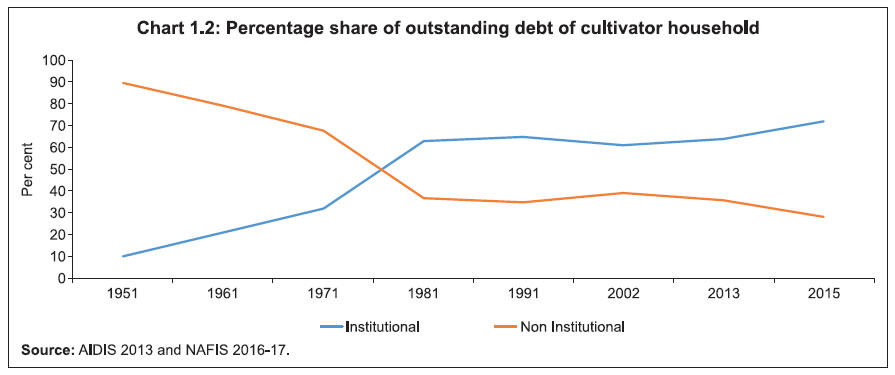

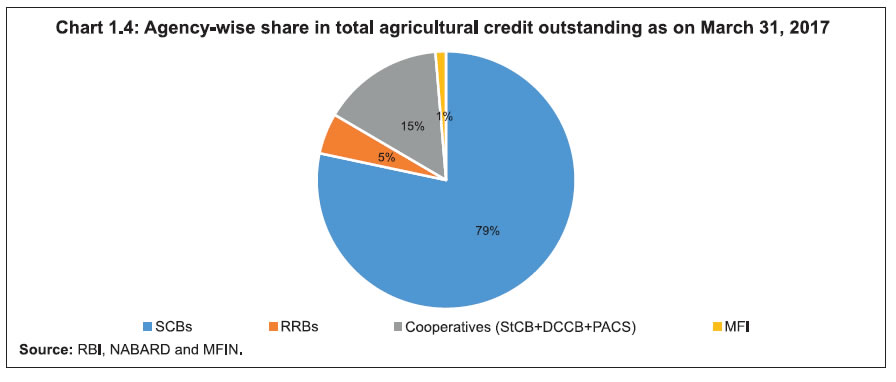

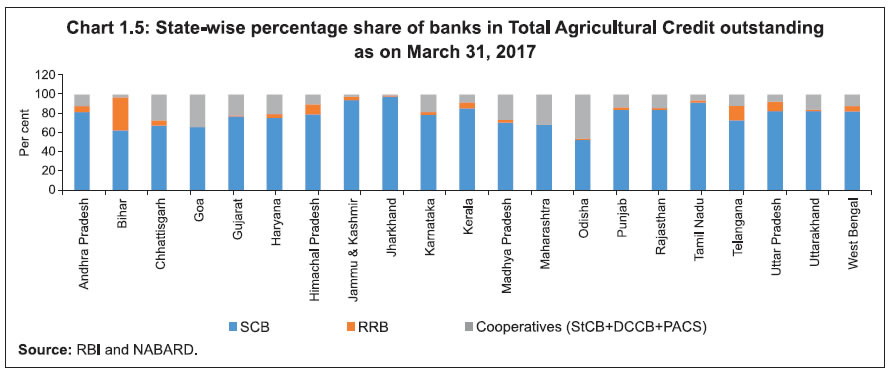

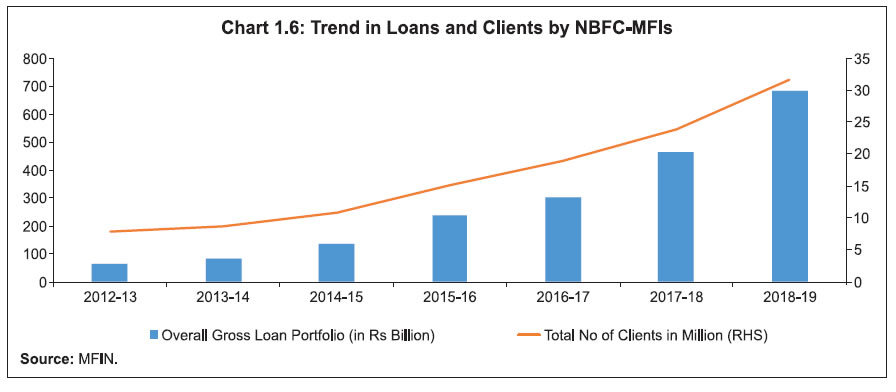

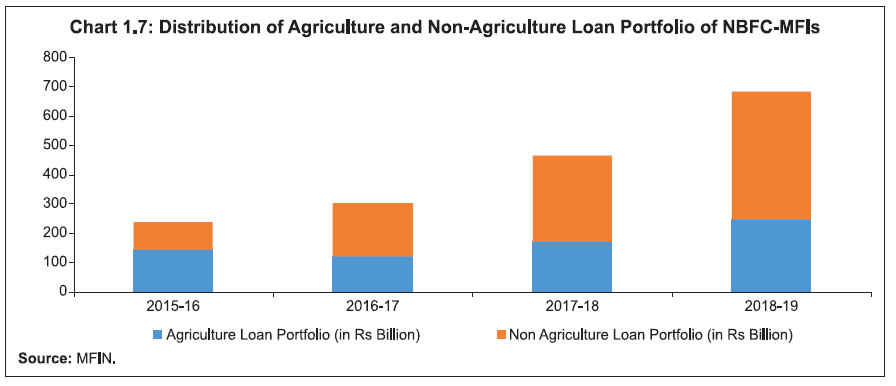

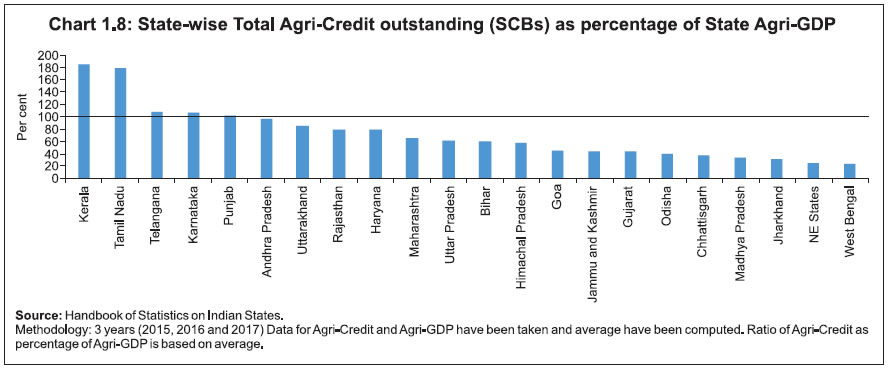

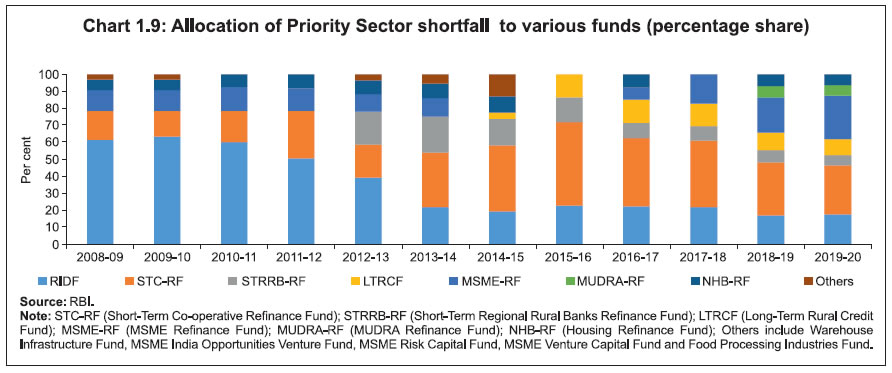

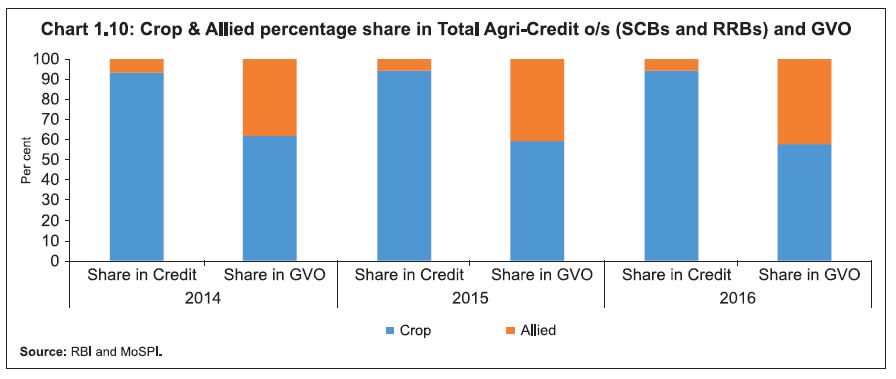

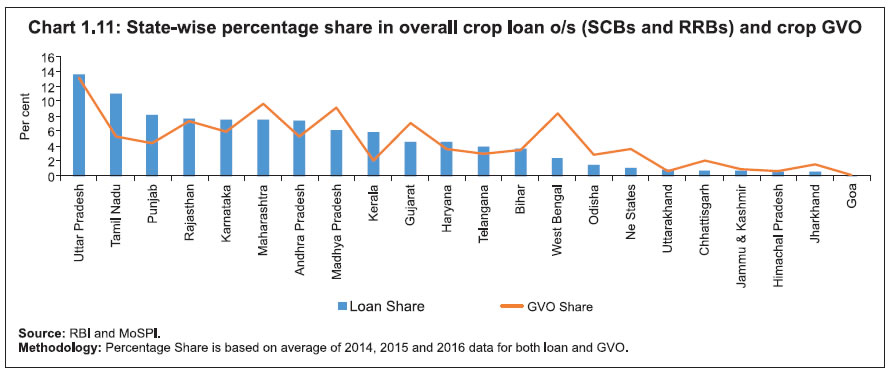

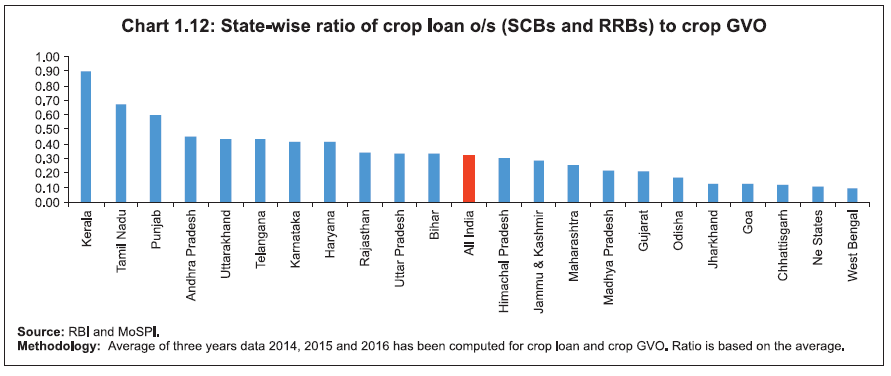

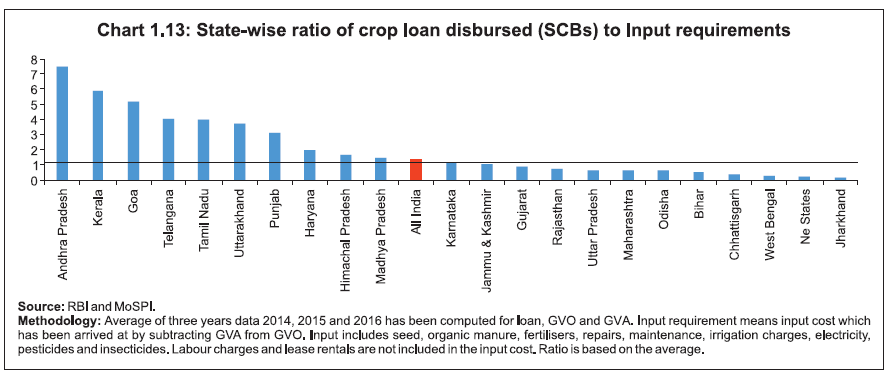

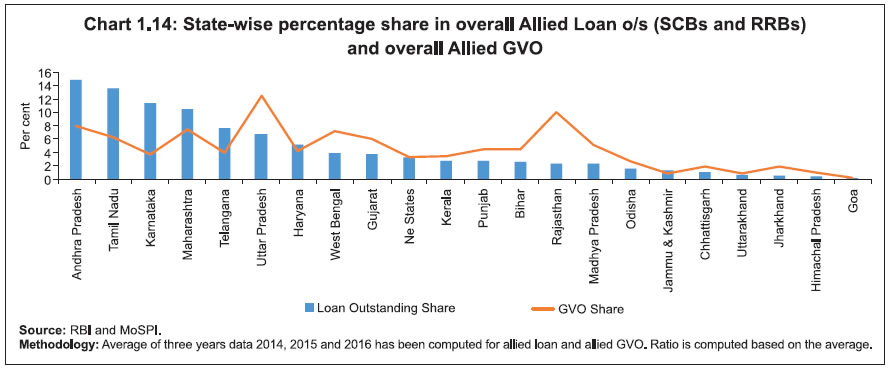

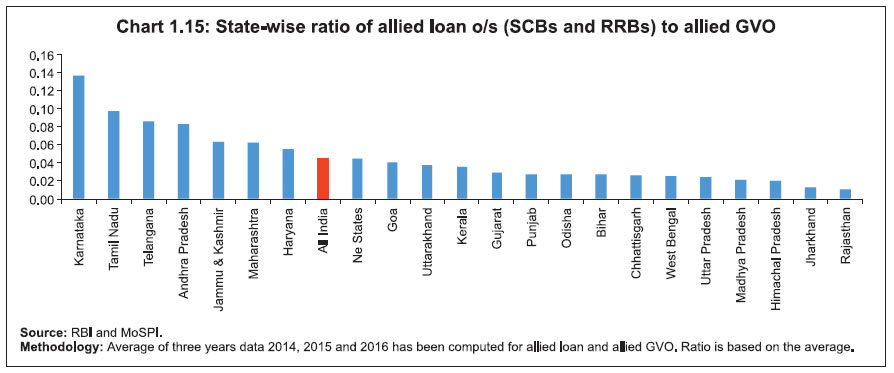

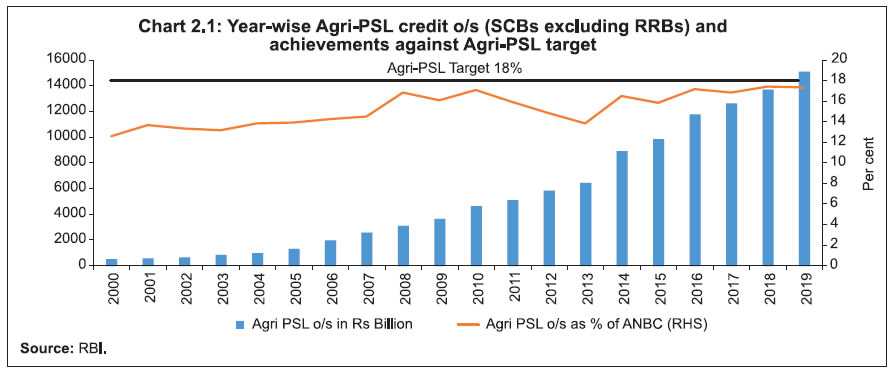

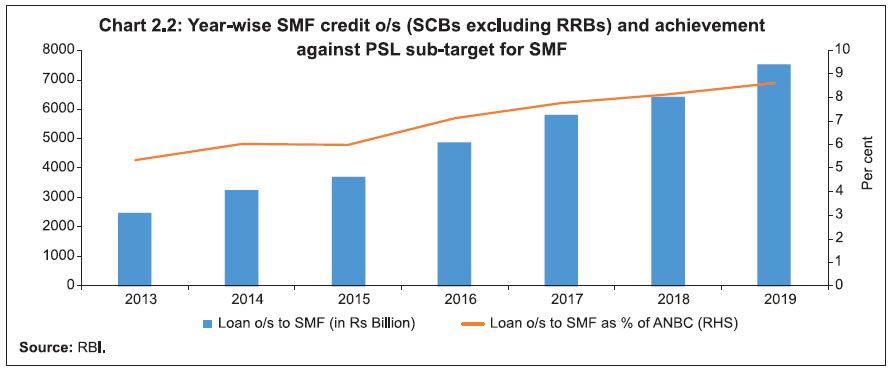

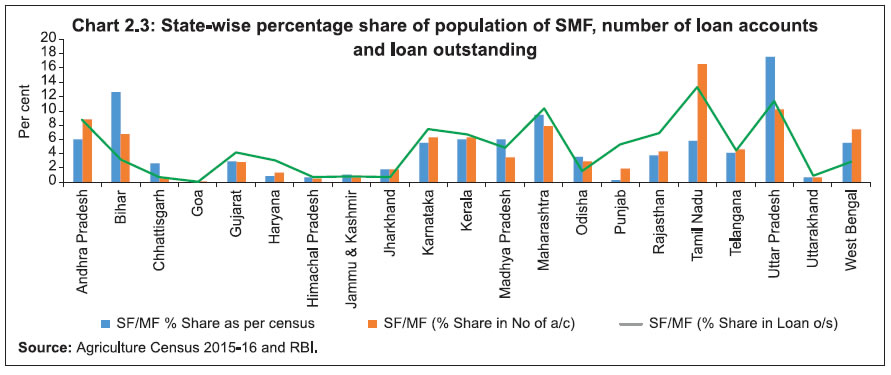

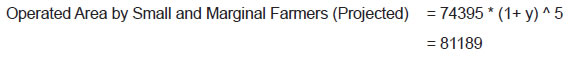

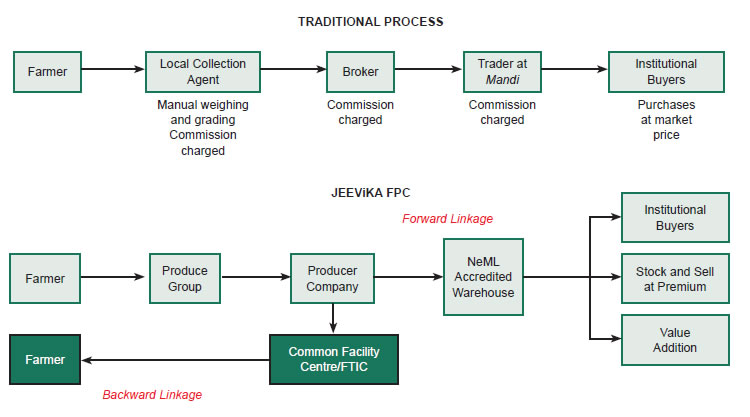

1.2 Trend in Agricultural Credit 1.2.1 In order to understand the impact of policy milestones discussed above on agricultural credit and its performance with respect to agricultural GDP, the ratio of agricultural credit to agricultural GDP was computed taking into account the agricultural credit outstanding as well as disbursement. Accordingly, two line graphs are plotted in the following chart. 1.2.2 The ratio of Agri-Credit outstanding to Agri-GDP jumped from 0.6 per cent in 1950-51 to 9.81 per cent in 1971-72. Post 1972, the ratio shows an upward trend upto 1987- 88 increasing to 21.76 per cent. The impressive achievement of agricultural credit against agricultural GDP during 1950s-1980s is on account of nationalisation of banks and introduction of RRBs which expanded the reach of formal credit in the country. However, the reverse trend in the ratio started from 1990-91 onwards and it fell to 13.34 per cent in 1998-99. Post 1999 the ratio increased steeply and reached upto 39.55 per cent in 2006-07, which indicates that introduction of KCC was a big booster for agricultural credit and brought about a sea change in improving the reach of credit to the farming community. Many of the other policy initiatives started in 2004-05 also played an important role. In later years, despite a fluctuating trend, it rose to 49.63 per cent in 2015-16 and 51.56 per cent in 2017-18. The chart reveals that the trend of both the agri-credit outstanding as well as disbursement as percentage of agri-GDP are largely similar except in certain periods where there is divergence between the two. The reasons could be announcement of loan waivers which negatively impacted the repayment behavior of the borrowers and also made the banks averse to fresh lending. 1.2.3 Despite this spectacular achievement, the dependence of agricultural households on non-institutional sources, though reduced to certain extent, has persisted over the years. 1.3 Institutional vis-à-vis Non-Institutional Agricultural Credit 1.3.1 In the 1950s, the rural agrarian credit needs were traditionally met from the non-institutional sources largely through the local money-lenders. While the rural farmers had easy access to finance for their immediate needs, the steep interest rates, coupled with high illiteracy levels and the subsequent lack of awareness put them into a spiralling debt trap leaving them at the mercy of the money-lender. The evolution of the institutional structure through various Government policy interventions changed the scenario, whereby institutional sources, primarily through commercial banks became the major source for rural credit. The share of institutional credit vis-à-vis non-institutional credit as per AIDIS 2013 is shown in the chart below. Position for 2015 has been plotted based on NAFIS 2016-17. 1.3.2 According to AIDIS report, non-institutional sources were dominant in 1951, accounting for 90 per cent of the outstanding debt of cultivator households, but their share declined sharply to 37 per cent in 1981. After 1981, the rate of decline slowed down, and the share of non-institutional sources was 35 per cent in 1991. Thereafter a reversal of this pattern resulted in higher share of 39 per cent in 2002 which again dropped to 36 per cent in 2013. As per NAFIS Report 2016-17, the share of non-institutional credit in 2015 was 28 per cent. As against this, the share of institutional credit in agriculture increased from 10.2 per cent in 1951 to 63 per cent in 1981 and thereafter the share of institutional credit was hovering in the range of 63-65 per cent during 1981 to 2013. As per NAFIS, in 2015 the share of institutional credit was approximately 72 per cent. 1.3.3 Further, NAFIS Report 2016-17 has revealed that agricultural households avail credit from sources other than banks such as NBFC/MFI, financial companies, financial corporations, provident fund, insurance, relatives, friends, moneylenders, landlords, etc. The chart below shows the distribution of agricultural households according to type of sources of loans.9 1.3.4 According to NAFIS, institutional sources were preferred by agricultural households to avail credit as approximately 61 per cent of them avail credit from them. However, a significant portion, i.e. approximately 30 per cent of agricultural households still avail credit from non-institutional sources only which is a cause of concern. There is a need to ascertain the reasons why 30 per cent are still left out from getting institutional credit. The probable reasons could be that their credit demand could be for consumption purposes or they could be tenant farmers, sharecroppers and landless labourers who are not able to offer collateral security to avail institutional credit, or they are involved in unviable subsistence agriculture or banks don’t find them credit worthy. As a result, these farmers find it convenient to borrow money from non-institutional sources due to easy accessibility. 1.4 Measures to Improve the Reach of Institutional Credit 1.4.1 In order to bring the excluded agricultural households into the fold of institutional credit in a structured and sustainable manner, there is a need to build an enabling ecosystem with respect to policy interventions, institutional innovations and digital technologies. The enabling ecosystem would include digitisation of land records, reforming of land leasing framework, creating a national level agency to build consensus among states and the Centre with regard to agriculture-related policy reforms and innovative digital solutions to bridge the information gap between the banks and farmers. i. Digitisation of Land Records a. GoI started the Computerisation of Land Records Scheme to digitise all land records in 1988-89. Thereafter, in August 2008, the Digital India Land Record Modernisation Programme (DILRMP) was launched by Government of India, with the aim to minimise scope of land or property disputes and enhance transparency in the land records. b. The status of CLR, in terms of percentage completion, across states is shown in Table 1.1: c. Digitisation of land records has the potential to address various issues relating to agricultural credit, provided banks are given access to view land records online and/or they are given the facility to create charge online over land. This will help in reducing the instances of double or multiple financing on the same piece of land. ii. Land Leasing Framework a. Most states ban or restrict leasing of agricultural land leading to informal or concealed tenancy. As per T. Haque Committee (NSSO 2012-13), the tenancy in the country is around 10 per cent. As these tenant farmers lack documentary evidence as well as suffer from fear of eviction, they do not have the incentive to invest in agricultural land, leading to low productivity. Hence, there is a need to reform the land leasing framework by state governments by adopting policies like the Model Land Leasing Act proposed by NITI Aayog and Andhra Pradesh Land Licensed Cultivators Act, 2011. b. The Model Land Leasing Act recommends that all lease agreements be made formal and farmers cultivating on leased lands be given access to benefits including farm credit. The unified state of Andhra Pradesh was the pioneer to undertake reforms for tenant farmers in the form of Land Licensed Cultivators’ Act, 2011 under which Loan Eligibility Cards (LECs) are being issued to tenant farmers, making it possible for them to approach banks for credit. The Certificates of Cultivations (CoC) are issued under executive direction. iii. Federal Institution in Agriculture The Union Government in the past has suggested several reforms in the field of agriculture through the Model Agricultural Land Leasing Act, Model Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing Act, removing agricultural commodities from Essential Commodities Act, Digitisation of Land Records and e-NAM etc. However, the implementation of such reforms has not been very encouraging as many a times state governments might not be taken on board during the consultation or implementation process to take their concerns into consideration. In order to consult states and build consensus among them over reforms related to agriculture there is need for a federal institution, established on the principle of cooperative federalism, having representation from both Central Government as well as state governments. Such an institution exists in the form of the GST council which has been a success story. iv. Digital Innovations in Agriculture Sector The emergence of farm technologies integrated with robust ICT framework and other farm-related innovations hold tremendous potential to positively impact the growth in the agriculture sector. The technological innovations leverage tools like Internet of Things, Cloud, Big Data, etc. Some of the major developments are discussed below: a. e-NAM - a technology-driven unified national level market platform that integrates the physically dispersed markets enabling better price discovery for the farm produce b. Digital technologies such as Remote Sensing and Geo-tagging which helps in crop identification, crop production forecasting, crop acreage and yield estimation, assessment of crop progress and crop damage, soil health, soil mapping, water resource mapping and climate change monitoring c. Weather forecasting companies giving real time weather updates d. Under the Digital India Initiative the GoI provides mandi prices on real time basis through its ‘Gramseva: Kisan’ app. e. Corporates through mobile-based apps are providing farm machinery to farmers on rental basis which saves farmers from long-term investments. f. Movable warehouses and cold storages that help farmers to store their produce in a cost-effective manner g. State-of-the-art solar powered products for irrigation which will make farmers less dependent on electricity h. A few banks have launched mobile-based applications to cater to the specific needs of farmers and create an ecosystem for them through which they can purchase products, get weather updates and soil information and apply for loans. 1.4.2 Recommendation In view of the above, the IWG recommends the following: i. GoI should push state governments to complete the digitisation process and updation of land records in a time bound manner. ii. State governments should give access to banks to digitised land records in order to verify land title and create charge online. In such states banks should not insist on submission of land title documents. iii. State governments having a highly restrictive legal framework should be encouraged to reform their legal framework on the basis of Model Land Leasing Act proposed by NITI Aayog/ Land Licensed Cultivators’ Act, 2011 of the state of Andhra Pradesh so that formal lending to tenant farmers can improve. iv. GoI should set up a federal institution, on the lines of GST Council, having participation from both the Centre as well as the states to suggest and implement reforms in the field of agriculture. v. Aggressive efforts are needed to improve institutional credit delivery through technology driven solutions to reduce the extent of financial exclusion of agricultural households. Banks should explore collaborations with agri-tech companies/start-ups so as to provide access to credit in an integrated, timely and efficient manner to the farmers. vi. IBA should come out with a technology driven portal for the banks to facilitate ease of credit to the farmers for agriculture and allied activities on the lines of PSBLoansIn59 minutes to MSMEs. vii. Innovations like movable warehouses/cold storages and mobile based apps providing farm machineries on rental basis have been successfully operating but on a small scale. Hence, the GoI should identify the successful models in these areas which can be scaled up across the country. Further, banks should be encouraged to provide credit to such innovative solutions which support the agriculture sector. 1.5 Institutional Agricultural Credit - Agency-wise Share 1.5.1 In order to understand the performance of different agencies in lending to agriculture sector, a comparative analysis has been done showing their share in total agricultural and allied credit outstanding as on March 31, 2017. 1.5.2 Scheduled commercial banks contributed the major share (78 – 80 per cent) in agricultural and allied credit. Co-operative institutions also play a significant role in extending agricultural credit and the share of all co-operative banks/institutions (i.e. StCBs, DCCBs and PACS put together) constituted 15-16 per cent. The RRBs contributed the remaining 5 per cent of the agricultural credit. 1.5.3 The co-operative banking sector thrives either as three-tier or two-tier structure. The three-tier structure includes StCB, DCCB and PACS, whereas in two-tier structure only StCB and PACS are present. In the three-tier structure, the lower level tiers, i.e. DCCB and PACS extend credit to individual borrowers using their own funds/deposits and claim refinance from the upper tier, i.e. PACS from DCCB/StCB and DCCB from StCB. In the two-tier structure, PACS provide credit to individual borrowers and claim refinance from StCB. In some cases, the StCBs also extend credit to the individuals through its branches across the state. 1.5.4 The state-wise10 share of SCBs, RRBs and cooperatives in agricultural credit outstanding as on March 31, 2017 is shown in Chart 1.5: 1.5.5 The SCBs are the leading institutions in providing agricultural credit in all the states. The RRBs have significant presence in some states, viz., Bihar (35 per cent), Telangana (15 per cent), Himachal Pradesh (10 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (10 per cent). Cooperatives have played a significant role in Odisha (46 per cent), Goa (34 per cent), Maharashtra (31 per cent), Chhattisgarh (27 per cent), Madhya Pradesh (27 per cent), Gujarat (22 per cent) and Haryana (20 per cent) in providing agricultural credit. The high share of cooperative banks and RRBs in agricultural credit in these states is on account of their significant presence as compared to commercial bank branches in rural areas. 1.5.6 One distinct development in the expansion of rural credit institutions was the advent of NBFC-MFIs (Non-Banking Finance Company - Micro Finance Institutions) and Small Finance Banks. i. Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) a. MFIs have evolved as a significant segment for the rural credit market exhibiting a variety of business models in recent years. Post unified Andhra Pradesh crisis in 2010, the Reserve Bank of India issued guidelines for the lending operations of MFIs based on the Malegam Committee recommendations. A new category of NBFC–MFIs was introduced subject to satisfying conditions, viz., the capital to be employed, lending to members, cap on interest rate to be charged and margin to be retained, etc. As the loan extended to the MFIs by banks qualify for priority sector lending, subject to fulfillment of conditions, other MFIs also strove to follow these guidelines. The regulatory guidelines on NBFC-MFIs and inclusion of loans to MFIs by banks under priority sector lending guidelines resulted in phenomenal growth of MFIs during the period 2013 -2019. An analysis in terms of number of clients’ outreach and gross loan portfolio is shown here: b. In 2015, the RBI regulations stipulated that a minimum of 50 per cent of the MFI loans are to be deployed for income generating activities. As per Bharat Microfinance Report (2017), agriculture, animal husbandry and trading are major sub-sectors where income generating loans are deployed. Non-income generating loans are used for consumption, housing, education, water and sanitation and health etc. The trend showing the flow of credit for agriculture and non-agriculture purposes by NBFC-MFIs is as given here: c. Keeping in view the objective of financial inclusion, PSL guidelines on bank lending to MFIs for their on-lending activities, inter alia, prescribed cap on interest rate and margin. These guidelines have been revised from time to time. The extant guidelines stipulate that interest rate on individual loans will be the average base rate of five largest commercial banks by assets, multiplied by 2.75 per annum or cost of funds plus margin cap11, whichever is less. As per information provided by MFIN, the interest rate12 charged by MFIs was in the range of 19 per cent -24 percent during 2018-19. It appears to be on the higher side as compared to interest rates being charged by banks. This may be on account of higher funding and operational cost of MFIs. Due to the limited scope of study by IWG, deeper analysis into the funding/operational cost vis-à-vis interest rate charged was not attempted. ii. Small Finance Banks In September 2015, the Reserve Bank of India granted in-principle approval for setting up small finance banks (SFBs) with the objective of deepening financial inclusion by catering to clientele such as small and marginal farmers, migrant labourers, low income households, small businesses and other unorganised entities. As on date ten SFBs are functional. SFBs have been mandated to achieve overall 75 per cent of the lending towards PSL with the sub-target lending at par with SCBs. At the end of March 2019, amount outstanding under overall PSL by SFBs was ₹327 billion indicating achievement of 82 per cent. Lending towards agriculture and allied activities and small and marginal farmers was ₹101 billion and ₹78 billion respectively, which translate into achievement of 25 per cent and 20 per cent respectively, against the target of 18 per cent and 8 per cent. 1.6 Regional Disparity in Agricultural Credit 1.6.1 The IWG opined that disparity can be better brought out by analysing states individually instead of analysing region-wise. This is because in many cases, states within the same region are not very similar in various aspects relating to agricultural credit. Moreover, IWG suggested to combine all eight states (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura) under NE States as they have a miniscule share in the country’s overall output as well as loans to agricultural and allied sector. Further, as most of the UTs are predominantly urban areas and do not have significant potential for agriculture and allied activities, it was decided to exclude UTs from the analysis related to regional disparity. 1.6.2 To analyse the disparity amongst the states, the ratio of state-wise total agricultural credit outstanding in relation to its agricultural GDP have been plotted in the following chart. 1.6.3 This chart shows that some of the states are getting agri-credit higher than their agri-GDP indicating the possibility of diversion of credit for non-agricultural purposes. It also highlights the problem of regional disparity as states falling under central, eastern and north eastern regions are getting very low agri-credit as percentage of their agri-GDP. One way to stimulate the demand for rural credit including agricultural credit is to deepen the credit absorption capacity in these states. RIDF is one such tool available which has the potential to create the necessary credit absorption capacity in the rural areas of these states. RIDF is maintained by NABARD and is mainly deployed for rural projects like irrigation, roads and social sector by way of loans to state governments and state-owned corporations. In this context the performance of RIDF is discussed in the following paragraph. 1.6.4 Commercial banks contribute to the corpus of RIDF and other funds administered by DFIs based on their respective PSL shortfall. The chart below shows that the allocation to RIDF has been declining over a period of time from 61 per cent in 2008-09 to 18 per cent in 2019-20. Considering its significance, there is a need to increase the share of RIDF allocation. 1.6.5 The region-wise analysis of RIDF shows that the combined share of central, eastern and north-eastern region was approximately 41 per cent in terms of sanction/disbursement under RIDF13. NABARD has been striving to increase the allocation to these regions and the same is reflected with 51 per cent of RIDF allocation in the ongoing tranches. Still there is scope to increase the RIDF allocation to states falling in these regions in view of their poor performance in terms of agri-credit to agri-GDP as discussed in Chart 1.8. 1.6.6 Recommendation The IWG recommends the following: i. PSL guidelines should be revisited in order to explore the feasibility of introducing suitable measures for improving the credit off-take in central, eastern and north eastern states. ii. NABARD should gradually increase the allocation of RIDF in central, eastern and north eastern states over a period of time. iii. Corpus of RIDF should be increased and state governments should be sensitised to allocate a larger portion of their borrowing from RIDF for the purpose of absorbing funds for rural infrastructure development in their state. 1.7 Deployment of Agricultural Credit – Activity-wise 1.7.1 Agricultural activities have been divided into two broad heads, viz., crop and allied. Allied activity covers livestock, forestry and fisheries. It is important to understand the flow of institutional credit under these two heads in relation to their corresponding output. Chart 1.10 shows the comparative position in terms of percentage share in credit and output for crop and allied activities from 2014-2016. The credit extended for both production and investment have been taken into account. 1.7.2 The chart above shows that the allied sector has contributed significantly to the agricultural output with a share of 38 - 42 per cent during 2014 - 2016, though has been neglected by banks with the corresponding share of 6 – 7 per cent in total agricultural and allied credit during the same period. The problem of inadequate flow of credit to the allied sector is more pronounced in the case of state-wise analysis discussed in Chart 1.14. 1.7.3 The above chart shows the skewed distribution of state-wise percentage share in overall crop loan as compared to the percentage share in overall crop output. States such as Tamil Nadu, Punjab and Kerala have a loan share much higher than their contribution to output. 1.7.4 Crop loan in relation to its value of output and input cost i. To get deeper insights into credit intensity amongst states, two ratios, viz., Crop Loan/Output and Crop Loan/Input have been derived. A state-wise comparison with regard to ratio of Crop Loan/Output is plotted in the following chart. ii. While the all-India average was 0.32, there were eleven states with higher loan/output ratio - Kerala being the highest at 0.90 and West Bengal being the lowest at 0.09. This ratio also shows that there is huge disparity amongst states though not depicting clear picture of the extent of disparity, because Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are the three states with values of loan/output ratio above the all-India average but are not getting adequate credit to meet their input requirements for their crops as indicated in Chart 1.13. This may be possible on account of higher share of low value crops in their overall crop output. However, the states with higher credit intensity would have a higher risk of greater indebtedness among the borrowers. iii. The chart here shows the state-wise ratio of crop loan disbursed to their input requirements. iv. Some of the states are getting significantly high credit against their input cost requirement such as Andhra Pradesh (7.5 times), Kerala (6 times), Goa (5 times), Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand (4 times) and Punjab (3 times). On the other hand, Jharkhand, NE states, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Odisha, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan are not getting credit even to meet their input requirements. This highlights the skewedness in distribution towards few states and raises the question whether the credit is being used for the intended purpose. 1.7.5 Allied activities loan in relation to output i. As discussed in Para 1.7.1 above, crop loan accounts for more than 90 per cent of the total agricultural credit though its contribution to total output is approx. 60 per cent which means that the allied sector gets only 10 per cent of total credit while contributing the remaining 40 per cent of the total output. In this context it is important to understand this dynamics in the states. To analyse state-wise credit to allied activities two approaches have been adopted, one on the basis of state-wise percentage share in overall allied loan outstanding and overall allied output (Chart 1.14), and second on the basis of state-wise ratio of allied loan outstanding to allied output (Chart 1.15). ii. The above chart shows that Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Telangana are getting higher share in overall allied loan outstanding compared to their contribution to overall allied output. Majority of the remaining states are not getting loan in proportion to their contribution in overall allied output. iii. The chart below shows the state-wise ratio of allied loan outstanding to allied output. iv. From the above chart, it is inferred that a majority of the states are not able to avail credit for their allied activities and this highlights the neglect of the allied activities by banks. One probable reason could be lack of a proper definition differentiating a farmer growing crops from a farmer engaged in allied activities, as the Census defines a farmer on the basis of landholding size. As a result of this banks insist on land records from a farmer seeking credit for agricultural activities. Hence, there is a need for appropriate measures to improve the credit off-take towards allied activities, especially in those states which have potential for allied activities. v. Besides, banks do not have any specific mandate to lend towards allied activities. GLC is one mechanism whereby targets are fixed activity-wise and hence, can be leveraged to push credit towards allied activities. At present annual targets are set for crop loans and term loans, which the banks have been achieving every year. 1.7.6 Recommendation The IWG recommends the following: i. GoI should set separate targets for working capital and term loan towards allied activities under GLC. ii. PSL guidelines define SMF based on land holding size. To make it easier for banks to give credit for allied activities PSL guidelines should prescribe a separate definition for SMFs seeking credit for allied activities of upto ₹0.2 million. Accordingly, banks should not insist on land records from borrowers seeking credit of upto ₹0.2 million for allied activities. 2 INCLUSIVENESS AND INNOVATION Policy interventions such as Priority Sector Lending (PSL) have resulted in improved credit flow by banks to the agriculture sector and particularly to small and marginal farmers (SMFs). The Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme was an innovative product designed to cater to the different credit needs of the farmers. It has boosted farm credit but needs further impetus to increase the coverage. Other credit delivery models have brought about inclusiveness to the bottom of the pyramid. 2.1 Agricultural Credit under Priority Sector Lending 2.1.1 Priority Sector Lending is a major policy intervention/initiative through which credit is directed to sectors of national priority. The objective of the PSL has been to ensure that vulnerable and weaker sections of the society get access to credit and that there is adequate flow of credit to employment intensive sectors like agriculture and MSME. 2.1.2 At present, all Scheduled Commercial Banks are required to meet a target of 40 per cent of their Adjusted Net Bank Credit (ANBC) or credit equivalent of Off Balance Sheet Exposure, whichever is higher for Priority Sector Lending. RRBs and SFBs are required to meet a target of 75 per cent towards PSL. Besides the overall PSL targets, banks are required to achieve agriculture target of 18 per cent and a sub-target of 8 per cent of ANBC for small and marginal farmers. Under the revised PSL guidelines of 2015, direct and indirect agricultural lending has been dispensed with. The eligible activities include farm credit, agri-infrastructure and ancillary activities. As per the new guidelines, the approach of agriculture under priority sector is to focus on ‘credit for agriculture’ instead of ‘credit in agriculture’ in order to give impetus to financing of supply value chain in the sector. The trend of agricultural credit, total PSL and achievement with respect to prescribed targets is shown in the following chart. 2.1.3 Though at the aggregate level banks have been able to achieve the overall PSL target of 40 per cent, so far they have failed to achieve the agriculture target of 18 per cent at system-wide level. However, public sector banks have achieved 18.12 per cent as against private sector banks’ achievement of 16.30 per cent in 2018 - 19. 2.1.4 Achievement of Small and Marginal Farmers Target under PSL i. At the aggregate level, banks have been able to achieve the sub-target of small and marginal farmers under PSL. Though this reflects a satisfactory performance in terms of achievement of target by banks, a large proportion of SMF have not been covered by SCBs. As per PSL Returns (2015-16), the number of accounts under the small and marginal category are 5,13,88,257 and the total number of small and marginal farmers in the country as per Agriculture Census, 2015-16 was 12,56,35,000. This means, despite so many initiatives aimed at financial inclusion, only 40.90 per cent of small and marginal farmers could be covered by SCBs. There is a need to increase the coverage of SMF by banks as they constituted 86.21 per cent of total operated holdings and have 47.34 per cent share in the operated area. ii. The chart below shows state-wise comparative position of percentage share in population, number of loan accounts and amount outstanding regarding small and marginal farmers. iii. The analysis shows that the presence of a large number of small and marginal farmers in a state has not translated into proportionate number of loan accounts, highlighting the extent of financial exclusion among small and marginal farmers. Also, the pattern of percentage share in the number of loan accounts in a state does not match with the percentage share in amount outstanding particularly in the states such as Bihar, Odisha and West Bengal. iv. Tamil Nadu has come out as an outlier, having only 6 per cent share in the total number of small and marginal farmers although it is the leading state in terms of share in total number of loan accounts (17 per cent) and the highest share in amount outstanding (13 per cent). Similarly, Andhra Pradesh has a higher share in the number of accounts as compared to its share in number of SMF across the country. v. Further, in states such as Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal, the percentage share in loan outstanding is not proportionate to their percentage share in the number of loan accounts. This in a way may be an indication that the amount of loan per account for small and marginal farmers in these states was lower than that of other states. 2.1.5 Revisiting the Sub-target for Small and Marginal Farmers i. The above mentioned 8 per cent sub-target for small and marginal farmers was prescribed based on the recommendation made by the Internal Working Group (IWG), which submitted its report in March 2015, to revisit the Existing Priority Sector Lending Guidelines. The said working group recommended the sub-target of 8 per cent for small and marginal farmers based on their share in the operated area, landholding and their contribution to the agriculture sector. ii. Based on the historical data on operated area, we may make projections for total operated area (i.e. by all size class of farmers) as well as the operated area by small and marginal farmers for the year 2020-21. The projected percentage share of operated area held by marginal and small farmers out of total operated area held by all size class of farmers comes out to be 51.85 per cent in the year 2020-21. The detailed calculation is shown in Annex 2. iii. Assuming that agricultural credit, inter alia, depends on the operated area and due to the constraints on data availability regarding other probable credit determinants [such as district-wise input cost for a crop, type of crops being grown, crop-wise sown area, number/share of small and marginal farmers cultivating a crop and similar data for allied activities being undertaken by small and marginal farmers etc.] we reckon that credit is dependent on operated area. Further, if the overall target for agriculture remains at 18 per cent in year 2020 - 21 and based on the operated area with small and marginal farmers [as projected above] we may compute the share of agricultural credit that should be available to small and marginal farmers as 51.85 per cent of 18 per cent which is 9.33 per cent. a. The share computed above is based on the land operated by small and marginal farmers which has been taken from Agriculture Census 2015-16. The Agriculture Census does not consider landless labourers, tenant farmers, oral lessees and share-croppers etc. under the definition of small and marginal farmers. However, Master Directions on PSL include these farmers under the small and marginal farmers category for computation of achievement of sub-target of 8 per cent. It is important to mention here that the estimate regarding oral lessees, share-croppers and tenant farmers is not readily available. However, it is well known that such farmers along with landless labourers have a significant presence across states. b. The above calculated share of 9.33 per cent is still a conservative estimate for sub-target of small and marginal farmers. If landless labourers, tenant farmers, oral lessees and share-croppers etc. are to be included under SMF category then 9.33 per cent will further increase. Also, SMFs account for more than half of the total agricultural output at the national level and hold a major share in the high value crop production.14 c. The number of small and marginal holdings are on a consistent rise increasing from 49632 thousand in the year 1970 - 71 to 125635 thousand in the year 2015 - 16. This means the land is being increasingly fragmented resulting in diseconomies of scale which ultimately means the higher credit requirement per unit of land area. 2.1.6 Recommendation Based on the above discussion the IWG recommends the following:

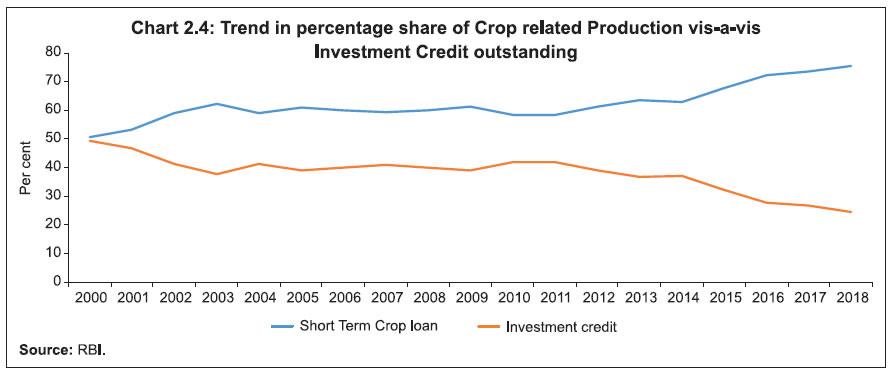

2.2 Interest Subvention Scheme for Short term Crop Loans 2.2.1 The Union Government had introduced the interest subvention scheme (ISS) for short term crop loans in 2006-07. It has been continuing since then with minor modifications. Interest on short term crop loans up to ₹0.3 million are fixed at 9 per cent per annum by banks and made available to farmers at a reduced rate of 7 per cent per annum to farmers. The 2 per cent interest subvention is reimbursed to banks (through RBI and NABARD) based on the funds released by the government against their claims. Besides 2 per cent interest subvention, 3 per cent prompt repayment incentive (PRI), introduced in 2009-10, is given reducing the cost of loan to 4 per cent. To prevent distress sale of produce, the interest subvention benefit is extended for a period of up to six months (post-harvest) to small and marginal farmers having Kisan Credit Card (KCC) on loan against negotiable warehouse receipts issued on the produce stored in warehouses accredited with Warehousing Development Regulatory Authority (WDRA). The scheme also provides for 2 per cent interest subvention to farmers for the first year on loans restructured due to natural calamities. 2.2.2 The ISS was meant for providing short term crop loans, i.e. production credit to farmers at a sub-vented rate of interest. However, it has resulted in skewed distribution of agricultural credit in favour of production credit against crop-related investment credit. As a result, the share of short term crop loan is on a consistent rise whereas the share of crop-related investment credit is on a decline. The trend analysis of the investment credit in relation to the short term crop loan availed by farmers is shown in the chart here. 2.2.3 As can be seen in the above chart, the proportion of short term crop loans to crop-related investment credit which was 51:49 in 2000 has drastically changed to 75:25 in 2018. It is interesting to note that the impact on investment credit was more pronounced 2011 onwards, after the introduction of prompt repayment incentive in 2009-10. The declining trend of investment credit is a cause of concern as the flow of investment credit is important for the long term sustainability of the agriculture sector. Apart from the ISS, the other probable reasons for consistent increase in short term crop loans and decline in investment credit are attributable to:

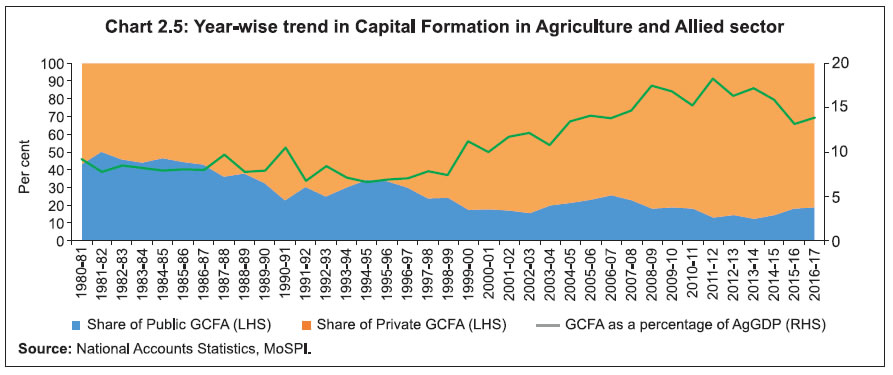

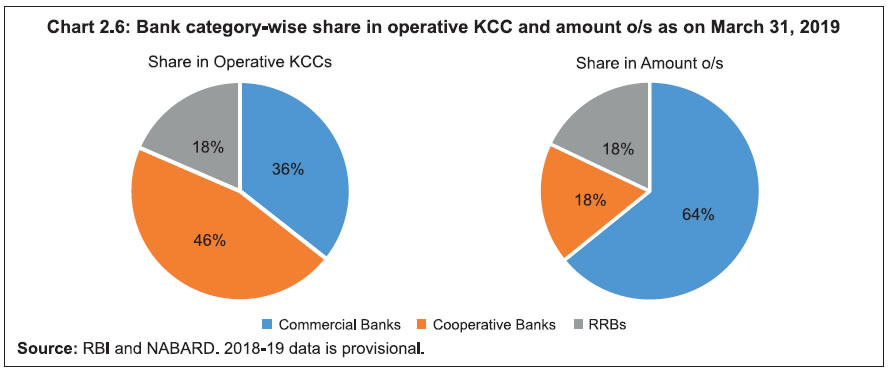

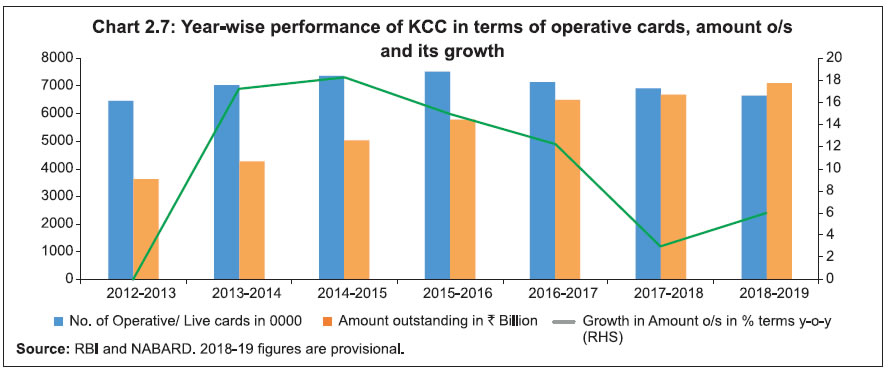

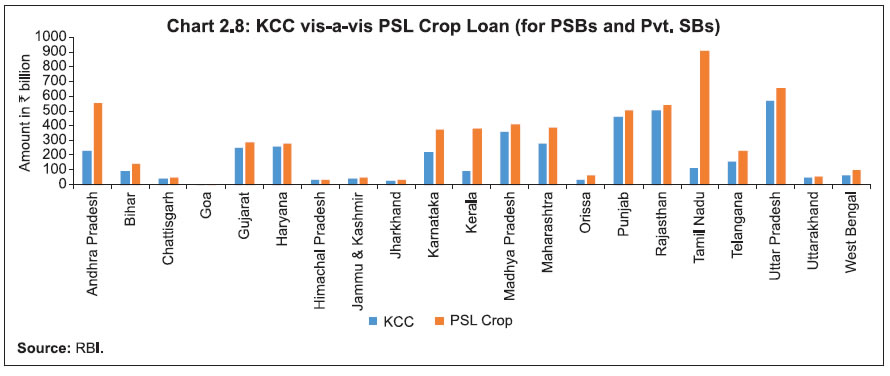

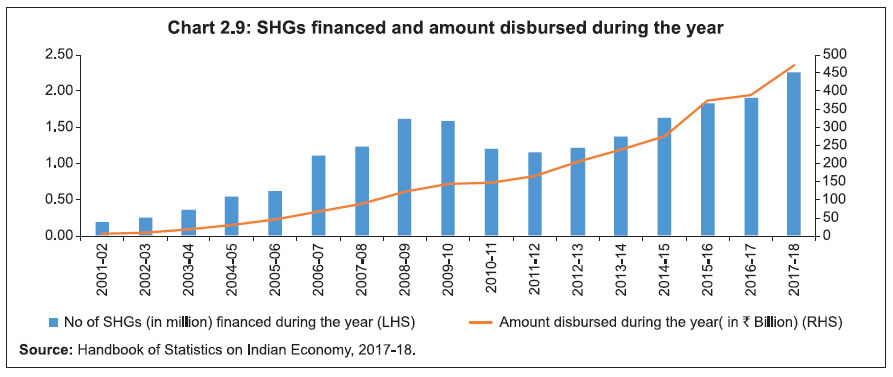

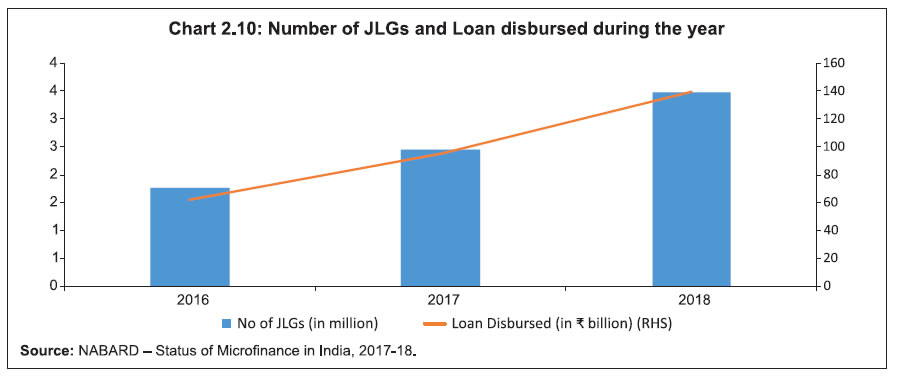

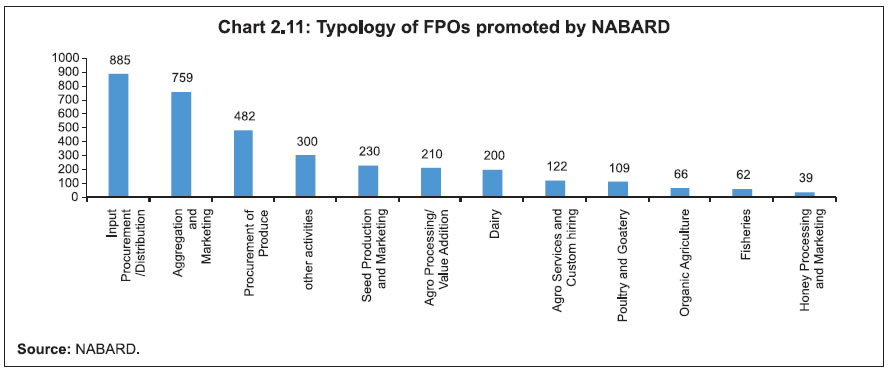

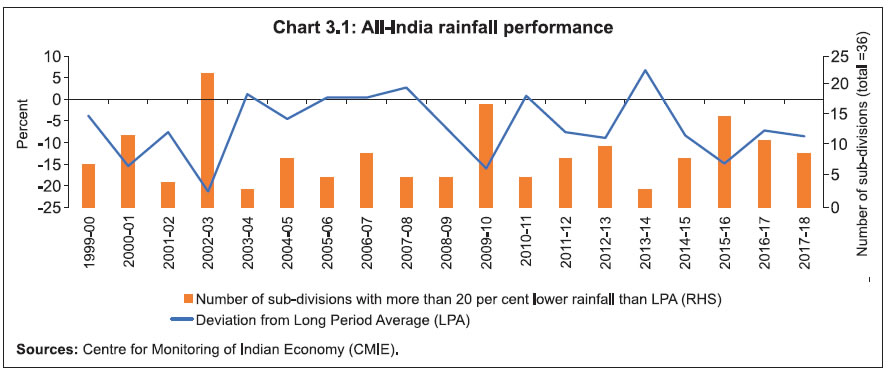

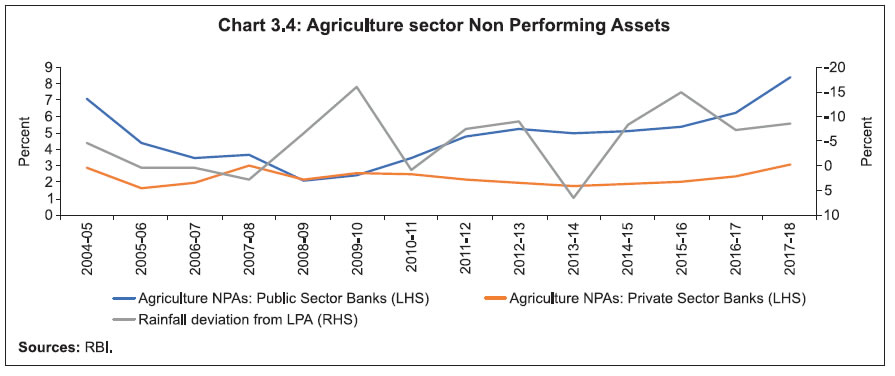

2.2.4 In general the Gross Capital Formation in agriculture as a percentage of agriculture and allied GDP has been declining over the years. The chart below depicts the GCF in agriculture as a percentage of agriculture and allied GDP. 2.2.5 GCF in agriculture as percentage of agri-GDP was 9.2 per cent in 1980-81, reached its peak at 18.2 per cent in 2011-12. Thereafter, it showed a declining trend till 2015-16 and then a slight upward trend with 13.8 per cent in 2016-17. Further, the public GCF which was at 43.2 per cent during 1980 - 81 has come down significantly to 18.8 per cent during 2016-17. Hence, there is a need for the Central Government along with state governments to improve their spending towards capital expenditure which ultimately will stimulate the demand for investment credit in the agriculture sector. 2.2.6 Recommendation The IWG recommends the following: i. State governments should promote and conduct awareness drives for land consolidation so that the farmers can achieve economies of scale and have the incentive to make long term investments. ii. The interest subvention scheme should be replaced with DBT to targeted beneficiaries, i.e. small and marginal farmers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, oral lessees and landless labourers as individual borrowers or through SHG/JLG model with an overall limit of ₹0.3 million per individual farmer. Innovations in Delivery of Agricultural Credit 2.3.1 The Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme, introduced in 1998, aimed at providing adequate and timely credit support from the banking system under a single window with flexible and simplified procedure for the farmers for their overall credit requirements such as cultivation of crops, post-harvest expenses, marketing of produce, maintenance of farm assets, activities allied to agriculture and also consumption requirements of farmer households. As per 2019 data, there were total 66.2 million operative KCC accounts, the bank category-wise share of which is shown in the following chart: 2.3.2 The performance of KCC has been analysed in the following chart. 2.3.3 As per 2019 data the number of operative KCC is approximately 66.2 million and as per Agriculture Census 2015 - 16 the number of land holdings were approximately 145 million, which implies that only 45 per cent of farmers possessed operative KCCs. However, there may be famers with multiple KCC cards and the actual coverage may be lower. As per NAFIS Survey 2016-17, 4.6 per cent of agricultural households hold more than one card. Also, the survey reports that taking all agricultural households together, only 10.5 per cent of agricultural households were found to have a valid KCC. Hence, there is a need to take measures to improve the penetration of KCC by banks across the country. 2.3.4 An analysis of the crop loans outstanding under PSL shows that only 62 per cent of them as on March 31, 2018 are through KCC mode. To identify the states where KCC is the preferred credit instrument for lending to farmers, a state-wise comparison of crop loan vis-à-vis KCC has been plotted in the following chart. 2.3.5 While KCC has emerged as a preferred credit instrument for disbursing crop loans, the incidence of crop loans outside KCC is very high. In Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Karnataka, 71 per cent of the crop loans are disbursed outside of KCC, the highest being in Tamil Nadu at 88 per cent. This may be because farmers are availing agricultural loans against gold as collateral. The crop loan analysis discussed in Para 1.7.4 revealed that the regional distribution of agricultural credit is distorted and disproportionate to the agricultural input requirements and output. The predominance of agricultural loan against gold as collateral is a matter of concern as the quantum of loan must have been delinked from the scale of finance15. If the crop loan is not based on the scale of finance there is high probability that the crop loan amount sanctioned may be higher than the actual credit requirement. Banks find it easier to sanction such loans as these are secured loans. This ultimately leads to diversion of funds and consequently, high incidence of indebtedness among the farmers. Further, the short term crop loans are eligible for Interest Subvention Scheme that incentivises farmers to avail such agricultural loans leading to misutilisation of government subsidy. This issue can be addressed by routing all the crop loans, eligible for interest subvention, through KCC mode only. 2.3.6 As discussed in Para 1.3.4, approximately 30 per cent of agricultural households still depend on non-institutional sources for their credit requirements. Some of these agricultural households need credit for their consumption requirements which banks are not willing to give and hence, they are compelled to go to money lenders. Though KCC limit has an inbuilt component of 10 per cent for consumption requirements of the farmers, this may not be adequate. Hence, there is a need to encourage banks to give credit to agricultural households for consumption purposes. 2.3.7 Recommendation The IWG recommends the following: i. There is a need to address the issue of sanctioning of agricultural loans against gold as collateral. Presently such loans are not separately flagged in core banking solution (CBS) platform of banks. Hence, banks should develop an MIS to flag agricultural loans sanctioned against gold as collateral in CBS in order to segregate such loans for effective monitoring of end use of funds. ii. In order to curb the mis-utilisation of interest subsidy, banks should provide crop loans, eligible for interest subvention, only through KCC mode. iii. Banks should be allowed to give consumption loans to farmers upto a sanctioned limit of ₹0.1 million under PSL provided banks are able to obtain collateral security and are satisfied with their repayment capacity based on the cash flows of the borrowers. However, such loans will not classify for PSL-Agri. iv. To improve ease of credit, the limit of ₹0.3 million for waiving collateral security by the banks in case of tie-up arrangements should be revised to ₹0.5 million under the existing KCC guidelines subject to the condition that the tie-up arrangements are between the producers and processing units without any intermediaries. 2.4 Improving KCC scheme - Scale of Finance 2.4.1 RBI guidelines on KCC scheme prescribe that the crop-wise Scale of Finance (SoF) as decided by District Level Technical Committee (DLTC) should be used to arrive at the short term limit for the crop loan. The guidelines on SoF are issued by NABARD. As per the guidelines, the district is the unit for determining the crop-wise scale of finance per unit of area because of different agro-climatic characteristics and separate SoF are to be fixed for irrigated and unirrigated areas. DCCBs are the convenors of DTLC and they play a major role in fixing the SoF. 2.4.2 A short study was conducted to understand the effectiveness of the scale of finance and to ascertain whether it is realistic keeping in view the cost of cultivation and expected price to be realised. The study was carried out in states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala, Bihar, West Bengal and Assam. In each state, five districts with the highest credit off-take were selected and rural branches with significant crop loans were visited on random sample basis. 2.4.3 The findings of the study indicated that different approaches were used to arrive at the scale of finance for sanctioning of crop loans. Complaints were received in the past from farmers regarding crop loans not being in tandem with the cost of cultivation. This may be on account of lower SoF fixed by the DLTC. Further, there are issues of huge variation in SoF for a single crop across districts within the same state. This may be on account of differences in geographies, climatic conditions, farming practices, usage of machines, irrigation facilities and labour charges etc. This leads to difficulty in implementation and monitoring by banks with regard to adherence by their branches. Hence, there is a need to have a uniformity and transparency in scale of finance. 2.4.4 DCCBs are the convenors of DTLC and they play a major role in fixing the SoF. However, they lack the resources and technical capabilities to carry out such exercises which need a more scientific approach. Moreover, as the financial health of most of the DCCBs is not sound, they fix the SoF at a lower level. The banks are required to follow the SoF fixed by DLTC, though they have the flexibility to have a higher SoF. Consequently, this leads to further variations in SoF for a crop within the same district. This issue can be addressed by assigning the responsibility of fixing the SoF for crops to SLBC at the state level which is justifiable as banks have emerged as the main purveyors of credit to the farming community. 2.4.4 The benefits of the KCC have been recently extended to working capital limits for animal husbandry farmers and fisheries. Lending for AH&F has not taken off on account of delay in fixing the district-wise SoF in states. In allied activities there would not be much variation in terms of unit cost of livestock, shed and expenditure towards feed, maintenance etc. Hence, a pan-India SoF would be feasible for allied activities and will also make it easier for banks to monitor the credit flow. 2.4.5 Recommendation The IWG recommends that for better monitoring of branches by banks and easier implementation of KCC there should be uniformity in scale of finance (SoF) for both crops and allied activities. Towards this objective state-wide SoF for crops should be prescribed separately for irrigated and unirrigated areas by the State Level Bankers’ Committee (SLBC). IBA in consultation with NABARD should fix a pan-India SoF for allied activities. 2.5.1 Self Help Group - Bank Linkage Programme (SHG-BLP) launched in 1992 was an innovation harnessing the synergy of flexibility of an informal system with the strength and affordability of a formal system. The SHG-BLP model has the following three main features: