IST,

IST,

Minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting December 2 to 4, 2020

[Under Section 45ZL of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934] The twenty sixth meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), constituted under section 45ZB of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, was held from December 2 to 4, 2020. 2. The meeting was attended by all the members – Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Senior Advisor, National Council of Applied Economic Research, Delhi; Dr. Ashima Goyal, Professor, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai; Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad; Dr. Mridul K. Saggar, Executive Director (the officer of the Reserve Bank nominated by the Central Board under Section 45ZB(2)(c) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934); Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra, Deputy Governor in charge of monetary policy – and was chaired by Shri Shaktikanta Das, Governor. Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Dr. Ashima Goyal and Prof. Jayanth R. Varma joined the meeting through video conference. 3. According to Section 45ZL of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, the Reserve Bank shall publish, on the fourteenth day after every meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee, the minutes of the proceedings of the meeting which shall include the following, namely:

4. The MPC reviewed the surveys conducted by the Reserve Bank to gauge consumer confidence, households’ inflation expectations, corporate sector performance, credit conditions, the outlook for the industrial, services and infrastructure sectors, and the projections of professional forecasters. The MPC also reviewed in detail staff’s macroeconomic projections, and alternative scenarios around various risks to the outlook. Drawing on the above and after extensive discussions on the stance of monetary policy, the MPC adopted the resolution that is set out below. Resolution 5. On the basis of an assessment of the current and evolving macroeconomic situation, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at its meeting today (December 4, 2020) decided to:

Consequently, the reverse repo rate under the LAF remains unchanged at 3.35 per cent and the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate and the Bank Rate at 4.25 per cent.

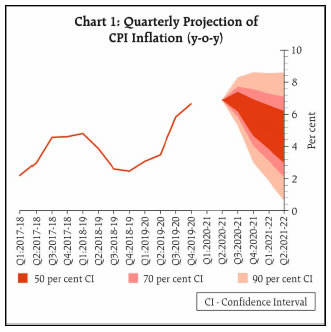

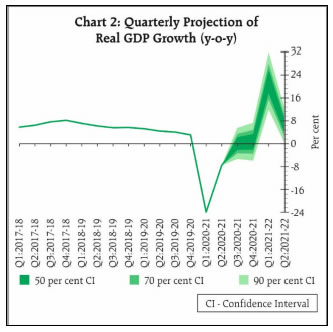

These decisions are in consonance with the objective of achieving the medium-term target for consumer price index (CPI) inflation of 4 per cent within a band of +/- 2 per cent, while supporting growth. The main considerations underlying the decision are set out in the statement below. Assessment Global Economy 6. The outlook for Q4 (October-December) of 2020 is overcast with a surge in COVID-19 infections in a second wave across Europe, the US and major emerging market economies (EMEs), with accompanying lockdowns. Progress on vaccine candidates has, however, generated some offsetting optimism. World trade recorded a rebound in Q3 as lockdowns were eased, but it is likely to slow in Q4 as pent-up demand is exhausted, inventory restocking is completed, and trade-related uncertainty is rising with the second wave. CPI inflation has remained muted across major advanced economies (AEs) while it picked up in some EMEs on firming food prices and supply disruptions. Global financial markets remain buoyant, supported by highly accommodative monetary policies and positive news on the vaccine. Domestic Economy 7. In India, the data release of the National Statistical Office (NSO) on November 27 showed a contraction of 7.5 per cent in real GDP in Q2:2020-21 (July-September). In Q3:2020-21, high frequency indicators point to a recovery gaining traction, with double digit growth in passenger vehicles and motorcycle sales, railway freight traffic, and electricity consumption in October, although there was moderation in some of these indicators in November. Riding on the favourable monsoon, the outlook for agriculture remains bright, with rabi sowing up 4.0 per cent from the acreage covered at this time last year under supportive soil moisture and reservoir conditions. 8. CPI inflation rose sharply to 7.3 per cent in September and further to 7.6 per cent in October 2020, with some evidence that price pressures are spreading. Food inflation surged to double digits in October across protein-rich items including pulses, edible oils, vegetables and spices on multiple supply shocks. Core inflation, i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel, also picked up from 5.4 per cent in September to 5.8 per cent in October. Both three months and one year ahead inflation expectations of households have eased modestly in anticipation of the seasonal moderation of food prices in the winter and easing of supply chain disruptions. 9. Domestic financial conditions remained easy in October-November and systemic liquidity continued to be in large surplus. Reserve money increased by 15.3 per cent (y-o-y) (as on November 27, 2020), driven by a surge in currency demand. Money supply (M3), on the other hand, grew by only 12.5 per cent as on November 20, 2020. A noteworthy development is that non-food credit growth accelerated and moved into positive territory for the first time in November 2020 on a financial year basis – hitherto, the large inflow of deposits into the banking system was being predominantly deployed in SLR investment. Corporate bond issuances stood at ₹4.4 lakh crore during April-October 2020 as against ₹3.5 lakh crore during the same period last year. India’s foreign exchange reserves were US$ 574.8 billion (as on November 27), up from US$ 545.6 billion on October 2 at the time of the MPC’s last resolution. Outlook 10. The outlook for inflation has turned adverse relative to expectations in the last two months. The substantial wedge between wholesale and retail inflation points to the supply-side bottlenecks and large margins being charged to the consumer. While cereal prices may continue to soften with the bumper kharif harvest arrivals and vegetable prices may ease with the winter crop, other food prices are likely to persist at elevated levels. Crude oil prices have picked up on optimism of demand recovery, continuation of OPEC plus production cuts and are expected to remain volatile in the near-term. Cost-push pressures continue to impinge on core inflation, which has remained sticky and could firm up as economic activity normalises and demand picks up. Taking into consideration all these factors, CPI inflation is projected at 6.8 per cent for Q3:2020-21, 5.8 per cent for Q4:2020-21; and 5.2 per cent to 4.6 per cent in H1:2021-22, with risks broadly balanced (Chart 1). 11. Turning to the growth outlook, the recovery in rural demand is expected to strengthen further, while urban demand is also gaining momentum as unlocking spurs activity and employment, especially of labour displaced by COVID-19. These positive impulses are, however, clouded by a possible rise in infections in some parts of the country, prompting some local containment measures. At the same time, the recovery rate has crossed 94 per cent and there is considerable optimism on successes in vaccine trials. Consumers remain optimistic about the outlook, and business sentiment of manufacturing firms is gradually improving. Fiscal stimulus is increasingly moving beyond being supportive of consumption and liquidity to supporting growth-generating investment. On the other hand, private investment is still slack and capacity utilisation has not fully recovered. While exports are on an uneven recovery, the prospects have brightened with the progress on the vaccines. Demand for contact-intensive services is likely to remain subdued for some time due to social distancing norms and risk aversion. Taking these factors into consideration, real GDP growth is projected at (-)7.5 per cent in 2020-21: (+)0.1 per cent in Q3:2020-21 and (+)0.7 per cent in Q4:2020-21; and (+)21.9 per cent to (+)6.5 per cent in H1:2021-22, with risks broadly balanced (Chart 2).   12. The MPC is of the view that inflation is likely to remain elevated, barring transient relief in the winter months from prices of perishables. This constrains monetary policy at the current juncture from using the space available to act in support of growth. At the same time, the signs of recovery are far from being broad-based and are dependent on sustained policy support. A small window is available for proactive supply management strategies to break the inflation spiral being fuelled by supply chain disruptions, excessive margins and indirect taxes. Further efforts are necessary to mitigate supply-side driven inflation pressures. Monetary policy will monitor closely all threats to price stability to anchor broader macroeconomic and financial stability. Accordingly, the MPC in its meeting today decided to maintain status quo on the policy rate and continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. 13. All members of the MPC – Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Dr. Ashima Goyal, Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, Dr. Mridul K. Saggar, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Shri Shaktikanta Das – unanimously voted for keeping the policy repo rate unchanged. Further, all members of the MPC voted unanimously to continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. 14. The minutes of the MPC’s meeting will be published by December 18, 2020. Voting on the Resolution to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 4.0 per cent

Statement by Dr. Shashanka Bhide 15. The prevailing economic scenario has presented both positive developments and concerns. The positive developments have included better than expected GDP growth recovery in Q2: 2020-21 and promise of vaccines for the Covid-19 becoming available in early 2021. The major concerns are the recent second wave of Covid-19 infections and deaths in Europe and the US leading to shutdowns and the continuation of inflation pressures. 16. The official data on GDP for Q2: 2020-21 released at the end of November 2020 indicates a year-on-year contraction by 7.5 per cent as against our October 2020 assessment of GDP contraction of 9.8 per cent. The positive growth in manufacturing output in terms of gross value added is a major positive indicator of revival of the economic activities. The imminent approvals for vaccines for the Covid-19 pandemic have raised the prospects of return to normal economic activities at the global level, subject of course to all the safety considerations until the vaccination programs cover all the population. The potential for the spread of the virus in the absence of critically vital safety precautions such as masks and social distancing cannot be ignored until the effective vaccination is achieved. 17. The headline CPI inflation rate for October is at 7.6 per cent, after the average inflation in Q2: 2020-21 at 6.9 per cent. The actual inflation rate for Q2 is slightly higher than our expected rate of 6.8 per cent in October. 18. The sustained recovery of the economy to bring back the lost employment and income to the workers remains crucial policy goal and maintaining moderate levels of inflation is equally important to sustain the recovery process. Experience of the previous quarter is an important guide for framing the monetary policy at this juncture. 19. The policy rates were left unchanged in October with Repo rate at 4 per cent and continuation of the accommodative monetary policy stance into the next year. This position appears to have supported a fairly broad based recovery process. This forms the context for my assessment of the economy and the view on the monetary policy resolution. 20. The output performance of the various sectors in Q2: 2020-21, measured in terms of gross value added (GVA) in constant prices, indicates broad based recovery. Year on year basis, Agriculture & allied activities sector registered a growth of 3.4%, Manufacturing 0.6%, Electricity and Utilities 4.4% and in the remaining 5 sectors, growth rate was negative but barring two sectors, the decline over the previous year was less steep than in Q1. In the case of Finance, Real Estate and Professional Services, and Public Administration and Defence & Other Services, the decline was steeper than in Q1. In the case of construction and Trade, Hotels, Transport, Communication and Broadcasting related services, which experienced a decline of close to 50% in Q1, the rate of decline in GDP in Q2 was less than 16%. The recovery of economic activity in Q2 over the level in Q1 is seen in all the sectors, except Agriculture & Allied and Mining & Quarrying. In both these cases, this may be a seasonal feature. For all sectors together, GVA in Q2 increased by 19.4% over Q1. 21. In terms of demand components of GDP, barring Inventory Change and Statistical Discrepancy, all the others show negative year-on-year growth. However, the YOY decline in Government Final Consumption Expenditure (GFCE) in Q2 has followed an increase in Q1. In all other cases, the rate of contraction in Q2 is less steep than in Q1. Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) and Private Final Consumption Expenditure (PFCE) have registered less steep YOY decline in Q2 than in Q1: 2020-21. Importantly, in all the cases, barring GFCE, the level of demand in Q2 is higher than in Q1. The improvement in the level of demand over Q1 along with lower contraction YOY basis signal sustained recovery. 22. Despite the overall improvement in the level of economic activities, there are concerns on the status of some of the sub-sectors and aspects of the economy. There are no clear indications of the extent to which the micro and informal sector enterprises have fared in this phase of recovery. In the case of registered or organised sector, the analysis of unaudited quarterly statements of 2570 listed non-financial private companies conducted by RBI shows that manufacturing firms have managed to achieve profits by reducing input costs and staff costs while facing cuts in value of production. In a scenario where output of the economy contracted by about 24%, recovery is not expected to be uniform across sectors both due to the differences in the nature of supply chains and demand conditions, often leading to ‘multi-speed recovery’ indicating the difficulties in achieving seamless recovery. Some of the sectors, termed ‘contact intensive sectors’ such as hospitality and tourism will take longer to recover. The corporate performance in Q2 cited above shows that non-IT services companies fared poorly compared to IT companies. Firms also face increased costs of operation unless the activities resume the pre-Covid pattern of operations. Firms also need to recoup the losses incurred. This will require both improved productivity and higher realisation from sales. 23. A reflection of the disruptions in the production processes is also seen in the rising price pressures. While the rising rate of food inflation is mainly a result of production setbacks, there is also some evidence of price pressures in other sectors. The firming up of commodity prices in the international markets affects domestic prices through either input costs or prices of competing domestic output. The large levels of indirect taxes on petroleum fuels has kept the transport costs high for all sectors. 24. The prospects of sustaining growth recovery through both expansion of growth across sectors and rising growth rates of output in the short term beyond Q2: 2020-21 are seen in some of the ‘expectations surveys’ and the indicators of economic activity for which data are available with much less time lag. Among the indicators from outlook surveys, RBI’s own survey of manufacturing companies indicates optimism on improved production, order books and employment and on turnover in the case of services and infrastructure sectors for Q3. The optimism is broad based and stronger on the output and employment conditions in 2021-22. RBI’s analysis of the findings of its sample survey of manufacturing companies, based on preliminary partial results, shows that capacity utilisation (seasonally adjusted) increased from 47.9% in Q1 to 62.6% in Q2, but well below the long term average of 74%, highlighting improvement in output but also a significant unutilised capacity either because of supply constraints or lack of demand. 25. Improvement in demand is clearly needed to accelerate production. Growth of agricultural and allied sector GVA by 3.4 per cent in both Q1 and Q2 YOY basis has supported rural demand. The festival season provided one stimulus to demand for consumer goods in Q2, but sustaining that will require both confidence in income stream and safety in work. The sequential pickup in GFCF in Q2 is a sign of pick up in consumption demand expected by the producers. The consumer confidence surveys by RBI reveal an improvement in the expected levels of spending one year ahead compared to the present in November 2020 relative to the findings in September 2020. However, this positive sentiment is yet to catch up with the level seen in pre-Covid period. The uncertainty about the prevailing income and employment conditions appears to be significant. The recovery in economic activities requires support from consumer spending. 26. The external demand conditions remain uncertain. While exports of goods and services show signs of recovery in terms of moderating YOY rates of decline in Q2 over Q1, they are still negative. The net investment inflows, however, have shown positive growth. The forex reserves have increased by $97 billion between November 27, 2020 and end of March 2020. 27. The economic growth momentum presently depends on domestic factors. Financial conditions that support investment are a critical factor in strengthening this link. Fiscal measures that support demand are also a critical factor in strengthening aggregate demand. 28. The prevailing monetary and fiscal conditions represent favourable financial conditions for investment. However, support for the consumer demand will require return of employment and income growth. While government borrowing to finance the fiscal deficit is at a high level, government spending to support investment and consumption are needed at this juncture. 29. Imbalances in the supply and demand conditions are impacting the price scenario as in the case of food inflation. The food inflation has been led by a few commodities, whether it is vegetables or pulses due to production shortfalls. Large price spikes due to sudden supply constraints have affected headline inflation. Arrival of winter crops in the market is expected to bring down the pressures on these commodities. In the present situation, the price pressures are also seen in other sectors, as firms manage lower capacity utilisation and higher costs emerging from the need for greater care to address risks of Covid infections. Firming up of international commodity prices, despite the projected low trade volumes is another indication of supply constraints. These pressures appear to be largely supply related but may be supported by improving demand conditions and are a concern. 30. The forecasts of growth and inflation suggest that economic recovery will continue in the remaining two quarters of 2020-21 and more strongly in the first half of 2021-22. The headline inflation is expected to remain well above 6 per cent in Q3 and below 6 per cent in Q4. The sustained economic recovery leading to a projected positive year- on- year GDP growth in Q3 and Q4 reflects the rising momentum of economic activities built up by the relaxation of restrictions on movement of goods and commerce as the Covid cases have reduced. But this reduction in Covid cases can be sustained only if the norms of social safety – the masks and social distance- are observed, until mass vaccinations are achieved. The adverse risks to sustained recovery remain on account of the potential for the rise of Covid infections and its impact on both supply and demand. The adverse risks on the price front are also emerging from the supply side considerations. The prevailing conditions require access to liquidity and financial conditions favourable to production and investment on the supply side. High inflation remains a risk but easing these pressures requires easing supply conditions. 31. On balance, the need to support relaxing the supply side constraints is a priority as this is also needed to address inflation concerns. Improvement in demand conditions requires both fiscal support and decline in Covid-19 threat. 32. I vote in support of the resolution to keep the policy repo rate unchanged and further to continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. Statement by Dr. Ashima Goyal 33. Indian Q2 growth rate came in above expectations. One view attributes it to a temporary pent-up demand and festival driven surge. My own view is that just as the reversal of the liquidity drought had led to a revival of growth that was visible in the high frequency data for February 2020, the various measures to make liquidity available through the economy not only helped firms survive but have also revived demand. The bank credit growth figures show a turnaround but underestimate it. For example, reduction in precautionary liquidity hoarding leads to faster payments and unclogs the frozen economy. There are now other sources of market-based finance. Real estate inventory is beginning to move. Both households and firms have deleveraged, are cash rich, and ready to spend. There are early signs of firms beginning to invest. Even so, the kind of infrastructure boom we had in the 2000s will not occur. Moreover, it is not desirable. 34. India seems to have avoided a second Covid-19 peak and vaccines are around the corner. But we must remember growth is still negative. It will take at least a year to reach the earlier peak GDP level and more to recover lost growth. Jobs have been lost, some voluntary and some involuntary, especially in the lower middle class. The turnaround needs policy support until it is well established. 35. Headline CPI inflation has also exceeded expectations. But analysis suggests it is due to multiple supply shocks. Covid-19 and the lockdown was itself a massive supply shock, so much so that there was a break in the inflation series. The headline series being targeted now starts from Q2 (July-September), after the break in the lockdown months when it was not possible to even measure inflation. 36. Research shows household inflation expectations rise if inflation is high and persistent. Then headline inflation begins to affect core. Otherwise it is the reverse. To the extent inflation is due to a variety of supply-shocks coming on one after the other, intrinsic persistence may not have set in as yet. 37. The inflation expectations survey of households shows a sharp 100 basis points fall in current household inflation perceptions between September and November. There is also a mild softening of three month and one year ahead inflation expectations. Household inflation expectations are naive and normally exceed realized inflation. But the direction of change is informative. Professional forecasters all expect inflation to soften in H2 of this fiscal year. 38. Although the margin between consumer and wholesale prices remains high for specific goods suggesting retail supply chains are still disrupted, the fall in household inflation perceptions may be due to easier availability of goods. Fear of shortages makes the consumer willing to pay high prices, but the Indian consumer is price sensitive and will begin to search for lower price alternatives as mobility improves. Such searches may have started. There is a window for supply chains to stabilize. In August rural wages jumped up by 9.5% but since crops are plentiful possible second round rise in food prices may be limited. 39. Although October headline CPI inflation was 7.6%, WPI inflation was only 1.5%. Real rates remain positive for firms with respect to WPI inflation but are negative for households with respect to CPI inflation. There is still a chance CPI inflation may fall steeply in the next few months on supply-side action supported by favourable base effects. If inflation softens, such negative real rates will not persist. Also, the equilibrium policy rate is itself negative when growth rates are negative and output is much below potential, after a once in a century growth shock. 40. As long as the MPC stance is accommodative durable liquidity will be in surplus and short-term rates will not rise above the reverse repo rate. Rates have fallen below the reverse repo because of the combination of excess foreign inflows, intervention and reverse repo access limited only to banks. Even so, excess liquidity is still absorbed. Regulatory exposure norms can help prevent excess low rates driven short-term borrowing that creates risks. 41. The intervention that is raising foreign exchange reserves is required because over-valuation of the rupee can hurt exports, raise country risk and lead to a sharp depreciation later. Prolonged inflows can lead to over-valuation without intervention. Surges and sudden stops of capital flows to emerging markets due to advanced economy quantitative easing have hurt emerging market growth in the decade after the global financial crisis. There are many benefits from openness and from the availability of foreign savings but good management has to smooth shocks, reduce risks and protect the domestic growth cycle. 42. It is possible to sterilize excess durable liquidity from expansion in foreign exchange reserves, even while durable liquidity remains sufficiently in surplus to be able to absorb exogenous shocks such as outflows or changes in government cash balances. Giving greater access to reverse repo aids market development as well as short-term sterilization. Liquidity management tools can be used at any time. It is necessary to be watchful, however. 43. To the extent it is transient the contribution of excess liquidity to cost push inflation is limited. In an open economy import competition also caps price rise, especially with a rupee that is tending to appreciate, provided tariffs and taxes are moderated. 44. To continue the delicate balance between lowering inflation, anchoring inflation expectations yet strengthening the growth recovery, I vote to maintain the status quo in policy stance and rates. Statement by Prof. Jayanth R. Varma 45. At the outset, let me reiterate my disagreement with the use of the word “decided” in the forward guidance part of the resolution. My reasons for this disagreement have been articulated at length in my individual statement for the October 2020 meeting, and rather than repeat them ad nauseam, I would prefer to incorporate them by reference. I also indicated in the October statement that disagreements that are more philosophical than operative need not always be elevated to a dissent, and accordingly I choose not to dissent this time. 46. I wrote in my individual statement for the October 2020 meeting that “with short term rates already at 3.35%, the incremental benefits of a furthering lowering of this rate in the current macroeconomic environment are relatively low and not commensurate with the risks”. Since then, short term rates have fallen by a further 40 basis points. (The cutoff yield in the last 91-day T-bill auction before the October meeting was 3.36% while the corresponding yield for the last auction before the December meeting was 2.93% − a drop of 43 basis points). I believed then and believe now that this reduction of rates carries significant risks and very little rewards. The rewards are low because long rates are what are relevant for stimulating investments and supporting an economic recovery; a steepening of the yield curve by a reduction in short rates does not accomplish this. Also, a reduction in long rates that stimulates investment not only increases demand in the short run, but it also stimulates supply in the medium term as the new capacity becomes operational, and this new supply dampens inflationary pressures. 47. By contrast, the demand that is stimulated by a reduction in short rates is not accompanied by an offsetting supply boost, and therefore carries greater inflationary risks. A sub 3% short rate (corresponding to a negative real interest rate of −4.5%) risks encouraging speculative inventory accumulation and stoking inflationary buildup in sectors that are showing incipient anecdotal signs of cartelization and resurgence of pricing power. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in several sectors which are characterized by an oligopolistic core and a competitive periphery, the oligopolistic core has weathered the pandemic well and it is the competitive periphery that has been debilitated. Rising profits and profit margins, improving capacity utilization and lack of new capacity additions create ripe conditions for the oligopolistic core to start exercising pricing power. These are also the enterprises that are benefiting from borrowing at rates below the policy corridor through commercial paper issuance. I fear therefore that a sustained failure to defend the policy corridor could prove expensive in terms of creating inflationary pressures and inflationary expectations though, so far, low rates have been feeding into asset markets rather than goods price inflation. It is pertinent to note in this context that the IIM Ahmedabad’s business inflation expectations survey released just before the MPC meeting reported an increase in inflation expectations. 48. Turning to the resolution, I indicated in my individual statement for the October 2020 meeting that monetary policy must remain accommodative “as long as realized outcomes do not diverge drastically from what is currently expected.” It must be admitted that realized growth and inflation have both drifted towards the edge of the fan charts while remaining within them. Nevertheless, it is my considered view that the balance of risk and reward at the current juncture is still in favour of monetary accommodation. Therefore, I support maintaining the policy rate at its current level. I also support the accommodative stance and liquidity support that drive short term rates towards the reverse repo rate rather than the repo rate, while being wary of a drop below the corridor. The MPC must continue to be data driven and must continue to monitor future developments carefully. Statement by Dr. Mridul K. Saggar 49. Central banking has not been usual once the pandemic set in. Supporting growth was a natural priority given the cliff effects of pandemic on aggregate demand and supply. Monetary policy is now entering into a more complex zone. While growth is recovering faster than earlier anticipated, it has not yet taken sustainable roots. It remains to be seen how it might respond ahead as pent-up demand wanes while animal spirits remain anaemic. Furthermore, fiscal impulse has weakened since Q2:2020-21 and, therefore, despite inflation persistence, pulling back the monetary support to aggregate demand will not be an apt choice at this juncture. High inflation has persisted longer than predicted at the time of the preceding MPC meeting in early October. This was mainly due to unseasonal rains that caused vegetables price spike. As a base case, inflation should still start correcting in near months and fall below the upper-tolerance levels by December 2020. The upside risks, however, remain with some evidence that price pressures are starting to get distended. 50. Notwithstanding the remarkable improvement in activity levels, as also captured by normalisation of several high frequency indicators, there are several reasons to believe that growth will stay below trend for the rest of the year, even though positive terrain may be reached before close of the current fiscal year. The sharp recovery seen in indicators relating to auto sales cannot be interpreted as being reflective of the underlying trend in aggregate demand or supply conditions as pent-up purchases were being delayed, first on account of transition to stricter emission standards that kicked in since April and then on account of pandemic related lockdowns. Services sector accounted for 63 per cent of the gross value added and contributed 78 per cent to the overall growth over preceding two years. Several services continue to be deeply affected by the pandemic. These include hospitality, construction, real estate, trade, and several types of transport, even though railway freight movement has normalised. Investment demand which had significantly contributed to overall growth in 2017-18 and 2018-19 had dropped off in 2019-20 and was the main driver of the growth contraction during Q1:2020-21 and despite remarkable sequential improvement in Q2 is likely to stay weak, with capacity utilisation rate likely staying below 70 per cent against long-term average of 74.0 per cent. Non-food credit, a leading indicator for growth stays muted, though in the fortnight ended November 6, 2020, it jumped to 5.7 per cent year-on-year from 5.1 per cent in the preceding fortnight. It could be the turning point in credit offtake but is not clear at this stage and, in any case, it has not yet acquired strength to alter the growth-inflation trade. 51. Furthermore, in Q2:2020-21, government final consumption expenditure contracted by 22.2 per cent and public administration, defence and other services by 12.2 per cent, dragging the growth down in terms of weighted contribution to growth by 2.9 percentage points from the demand-side and 1.7 percentage points from the supply-side, respectively; lower supply-side contraction essentially reflected improvement in ‘other services’. The fiscal support to growth has nevertheless come from automatic stabilisers that have been stronger than in many emerging markets but remain weaker than in advanced economies, especially as they act through fall in tax revenue but have no automaticity to increase spending. The discretionary fiscal policies, therefore, become important but policy space has been limited by largely procyclical fiscal policies followed for years. In this backdrop, fiscal policy has attempted restrained counter-cyclical support since 2019-20. Going forward, growth is likely to get some support from fiscal spending in the remaining months of this fiscal year when bulk of the on-budget stimulus is likely to be spent. Given that fiscal multipliers are higher during large downturns and also that investment multipliers distinctly exceed revenue spending multipliers, the growth-targeting investment measures announced as part of additional stimulus in October and November are likely to complement monetary policy support to growth in a measured way. 52. Though monetary policy so far has provided a bungee cord to the growth, its tensile strength depends on how inflation evolves ahead. The nature of inflation still remains predominantly supply driven but with addition of some elements of cost-push inflation that can get a further fillip if three is a feedback from recent increased rural wage inflation. Cost-push inflation, even when arising from factors such as increasing food and energy prices, especially crude oil, and higher direct taxes, can start below the natural rate of unemployment if monetary accommodation is large and sustained. The Great Inflation episode after the oil price shock of 1973 bears testimony of these risks to which one needs to be mindful, even though recent flattening of Phillips curve has diminished correlation between core inflation and output. A decade back, post-global financial crisis, pushing demand continually, did result in resurgence of inflation in India. These risks are not imminent at this point. Since February 2020 policy, RBI has announced liquidity measures adding to about Rs 12.7 trillion. A significant portion of this liquidity has been parked back at central bank window. Therefore, it has not had a perverse effect on inflation so far. Through the interest rate, credit and confidence channels it prevented credit from dropping as steeply as nominal GDP. It also helped in maintaining total flow of resources to commercial sector at about last year’s level with the help of 58 per cent higher corporate bond issuances by non-financial entities during April-October 2020 compared with same period in the preceding year. So, this large liquidity infusion served a very important role in preventing meltdown of markets in Q1 of 2020, reversing the spike in financial spreads observed in March, averting acute credit crunch, thwarting tightening of financial conditions that could have plummeted economy into a deep recession with its domino effects on financial stability that could have further complicated policy choices. 53. The money supply growth so far this year has been reasonable. It has accommodated the shock to growth and substantially compensated for the steep drop in velocity of money that saw demand for currency to spike in Q1. However, going forward, at a point when expansion of activity takes firmer roots, recalibration of policies will become essential. In my assessment, given that output gap will close only in H2 of 2021-22, there is time to normalise monetary policy. As the pandemic shock created a huge negative output gap, even with high weight to core inflation along with lower weights to headline inflation and output gap, the projected path of these variables leaves time before policy rate hikes will become necessary. This is simply because the pandemic shock has left a huge negative output gap. If output gap closes faster than anticipated, core CPI inflation surges on back of observed momentum in some WPI inflation components or more supply-side shocks lead to generalisation of inflation, policy will need to respond appositely. I am labouring to explain this point because accommodative monetary policy has been misread by some as demise of inflation targeting. Quite to the contrary, current policies are consistent with the flexible inflation targeting mandate and hard empirical calculations of how monetary policy needs to react to projected path for key variables. The framework itself has delivered unambiguous gains in disinflating the economy and lowering inflation expectations. 54. Monetary policy under the inflation targeting strategy requires policy to be informed by economic analysis. Liquidity, credit and monetary aggregates will need to be closely monitored in this context with an eye on macro-financial stability that can be enervated when short-term borrowing costs fall below the operational policy rate. If this results in persistence of negative real rates for too long, it can adversely affect savings, lend support to mispricing of financial asset prices and encourage excessive leveraging. As such, other policies outside the flexible inflation targeting framework, such as macroprudential and strengthening the instruments of sterilisation in view of surge in capital inflows in recent months may be needed to mitigate these risks. 55. Considering the growth and inflation projections and other considerations enumerated above, I vote to keep the policy repo rate under the liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) unchanged at 4.0 per cent. I also vote for retaining the accommodative stance and accompanying forward guidance. Statement by Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra 56. I vote for status quo on the policy rate at this juncture and to maintain the accommodative stance of policy as articulated in the October 2020 resolution: as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. 57. The preponderant weight assigned by the monetary policy committee (MPC) to growth relative to inflation since the outbreak of COVID-19 appears to be yielding dividends – a much shallower than anticipated contraction in the economy in Q2:2020-21; strengthening incoming data in Q3 so far. A Beveridge-Nelson type trend cycle decomposition of real GDP (seasonally adjusted) indicates that the economy is perched on the shoulder of the recovery phase of the underlying cycle. Investment, followed by exports and private consumption, are the drivers of the recovering demand momentum, offsetting the drag from the decline in government spending. In terms of trends, government spending and exports remain stable, but private consumption and investment are on a downward trajectory. 58. As for the proximate indicators of aggregate demand embodied in the monetary aggregates – seasonally adjusted and smoothed by 5-year annualised averages – currency in circulation is still on the upswing and driving up reserve money, but the broader measures of deposits, bank credit and money supply are stabilising from a prolonged decline that started in 2010. In fact on a financial year basis, credit growth turned positive for the first time in 2020-21 in November.  59. On the supply side, manufacturing, followed by construction and trade services, are leading the cyclical upturn. Business optimism is also reflected in the buoyancy in order books and the pick-up in capacity utilization of manufacturing and services firms. 60. With growth gaining cyclical momentum, the window available to the MPC to look through inflation pressures is narrower than before. The wedge of 6.1 percentage points between WPI and CPI inflation in the October 2020 readings is elevated relative to the historical record – an average of 3.0 percentage points between 2015 and 2019, and 4.3 percentage points in February 2020 before COVID struck. More than half of this divergence is due to a combination of retailer margins in food prices (amplified by its higher weight in CPI than in the WPI), the sharp increase in taxes on petroleum products and alcoholic beverages in the post-COVID period (which are not captured in the WPI), and high prices of non-traded services such as healthcare, transport and personal services. Depressed input costs are widening the gap on the downside. Costs of sanitisation, social distancing, and of doing business have contributed to the higher retail mark-ups in goods and services, and thereby to the difference between WPI and CPI inflation. 61. Elevated inflation has checked in and may be here to stay. With retailers striving to recover lost incomes, it is unlikely that margins will ease in the near-term. Meanwhile, households recouping lost incomes may work towards keeping the supply price of services elevated. Returning cyclical demand, backed by improving business and consumer expectations, may allow a higher pass-through of input prices into selling prices as businesses endeavour to preserve profit margins. This is also reflected in expectations of surveyed manufacturing firms and persisting pessimism among consumers on the price situation. 62. Economic activity is recovering but hesitantly and unevenly. This warrant continuing policy support till it is set on a firm trajectory of self-sustaining expansion. At the same time, the confluence of forces determining inflation outcomes and their likely persistence imparts downside risks to growth, unless contained early. Amidst this high uncertainty, the MPC’s dilemma around its window of accommodation has become more acute than at the time of its last meeting. Statement by Shri Shaktikanta Das 63. Over the last two months it has become increasingly clear that the recovery underway is faster than what was anticipated at the time of the October policy, although it must also be noted that overall activity is still below its level a year ago. Meanwhile, inflationary pressures have continued unabated, posing challenges for monetary policy. 64. The Q2:2020-21 contraction in GDP turned out to be lower than projected at the time of October 2020 policy. In Q3:2020-21 so far, various high frequency indicators also suggest further strengthening of the momentum in economic recovery. Rural demand continues to be the main driver of growth with rabi sowing progressing well due to congenial soil and reservoir conditions. Urban demand is also showing signs of turning a corner. The Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey of urban areas has registered a marginal uptick in November 2020 from its trough in September. Optimism on early vaccine availability has also boosted economic sentiments. 65. As per my assessment, the recovery is multi-speed as more sectors are showing an upturn, though the improvement is not steady and continuous yet. In October, there was a double-digit growth in passenger vehicles and motorcycle sales, railway freight traffic, and electricity consumption. Demand conditions in the manufacturing sector, according to the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey, improved notably during Q3:2020-21 over Q2:2020-21, driven by easing of lockdowns and re-opening of businesses. Early results of order books, inventories and capacity utilisation survey suggest that the capacity utilisation (CU) in the manufacturing sector is recovering, increasing to 61.7 per cent in Q2:2020-21 from 47.3 per cent in Q1:2020-21, although still lower than its long-term average. The expansion of the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme to 10 more sectors is expected to boost manufacturing and exports. 66. Investment demand in the economy is still to gain traction even as the transmission of policy rate actions has been sharper and quicker. Corporate bond yields have seen a significant reduction. Investment-related indicators such as imports and production of capital goods and consumption of steel and cement posted some sequential improvement in October. Corporate finances in Q2:2020-21 indicated some signs of recovery in demand conditions with profit margins rising due to savings in expenditure. Debt servicing capacity for manufacturing companies, measured by interest coverage ratio, improved in Q2:2020-21 with rise in profits. While investment in fixed assets is muted, increased cash holdings, reduced leverage and improved profitability suggest that investment activity could rebound quickly as conditions normalise with the flattening of the COVID curve and the availability of vaccines. 67. Non-food credit growth in November 2020 accelerated and moved into positive territory on a financial year basis for the first time in 2020-21. Total flow of resources to the commercial sector from banks and non-banks is also running close to last year, thus creating enabling domestic financial conditions to sustain and strengthen the recovery process. Since February 6, 2020 the Reserve Bank has announced liquidity augmenting measures of ₹12.7 lakh crore (6.3 per cent of nominal GDP of 2019-20). Reflecting the various liquidity management measures and the supportive market operations undertaken by the Reserve Bank in fostering market confidence and strengthening financial stability, there has been a narrowing of term and risk premia in various market segments. Yields on government securities, commercial paper (CP), 91-day treasury bills, certificates of deposit (CDs) and corporate bonds have softened appreciably. Corporate bond spreads have broadly receded to pre-COVID levels. 68. The fiscal measures announced so far are a balanced mix of consumption, liquidity and investment measures, which have been sequenced as per the evolving situation. A calibrated shift in focus from consumption expenditure under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Package (PMGKP) to liquidity support under AatmaNirbhar 1.0 to investment expenditure under AatmaNirbhar 2.0 and 3.0 is clearly visible. On the whole, it is expected that the calibrated stimulus provided by the government is likely to flow through the economy through multiple channels - private consumption, fixed capital formation and push from the supply side. Increase in government expenditure during the remaining part of the year will provide further impulses to growth. Given the large multipliers for capital spending, the recent trend of cuts in States’ capital outlays needs to be reversed. As strong capex multipliers for both central and state capital expenditure kick in, crowding in of private investment could take place, all of which is critical during a revival phase. Overall, the recovery is likely to gain further traction in Q3:2020-21 and Q4: 2020-21. 69. On inflation front, a combination of cost-push factors including supply side disruptions, sharp increase in international commodity prices, high retail margins and elevated taxes on petroleum products by both Centre and States have kept inflation above the upper tolerance band of the inflation target. The October 2020 CPI surprised on the upside, both in terms of the extent and depth of price pressures. 70. Going forward, stronger measures to address the supply side issues and the winter moderation in vegetable prices should result in some softening in inflation from its current levels. Continuing demand supply mismatches in protein-based food and edible oils would require active supply side measures. The Reserve Bank is constantly engaged with the concerned authorities for undertaking supply-side measures to contain inflation. The improved prospects of a bumper kharif harvest and favourable rabi season should also keep cereal prices in check. The inflation expectations survey of households indicates a modest softening in both three-month and one-year ahead inflation expectations, though median inflation expectations continue to remain at elevated levels. 71. Overall, the persistence of inflation at elevated levels constrains monetary policy at the current juncture. At the same time, though recovery is underway, there is still continuous need to nurture and support growth to make it broad based and durable. A premature roll back of the monetary and liquidity policies of RBI would be detrimental to the nascent recovery and growth. The overall situation needs to be monitored carefully, both in the sides of growth and inflation. On balance, therefore, I vote to keep the policy rate unchanged and continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. We need to monitor closely all threats to price stability and possible spill overs to broader macroeconomic and financial stability. The Reserve Bank will continue to respond to global spill overs to secure domestic stability with our liquidity management operations. The various instruments at our command will be used at the appropriate time, calibrating them to ensure that ample liquidity is available in the system. (Yogesh Dayal) Press Release: 2020-2021/804 |

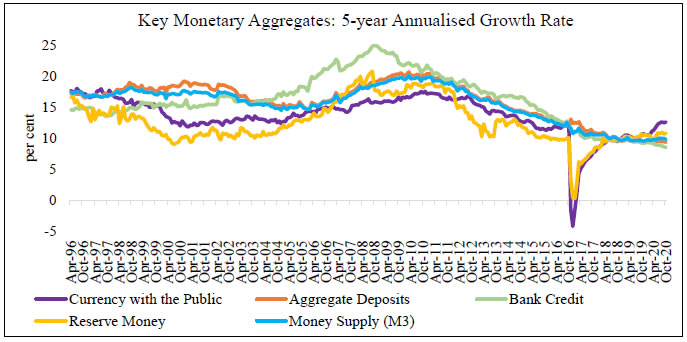

পৃষ্ঠাটো শেহতীয়া আপডেট কৰা তাৰিখ: