IST,

IST,

Monetary Policy Report - April 2020

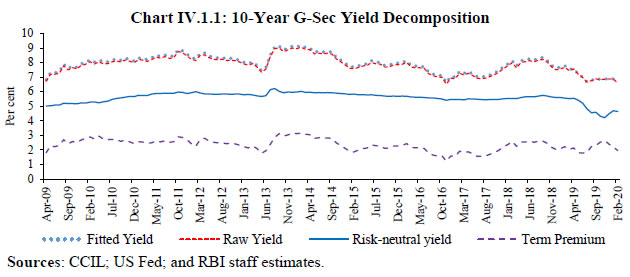

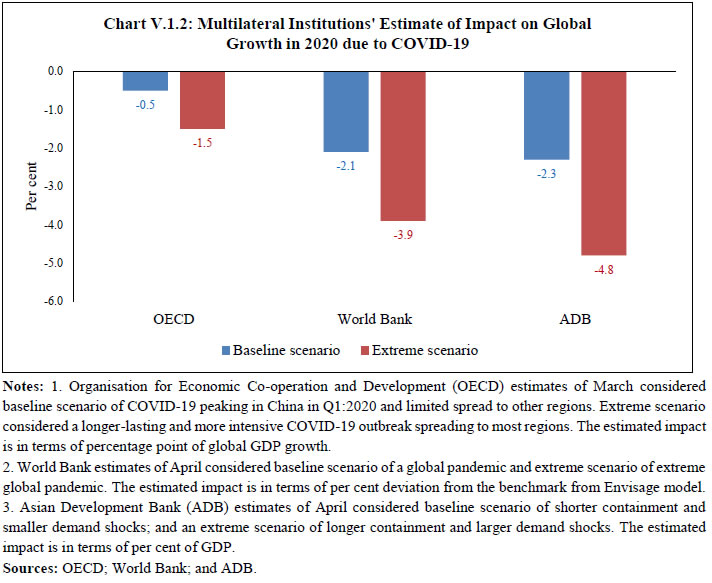

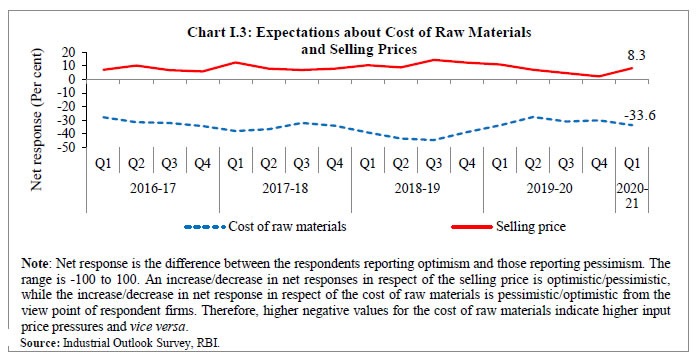

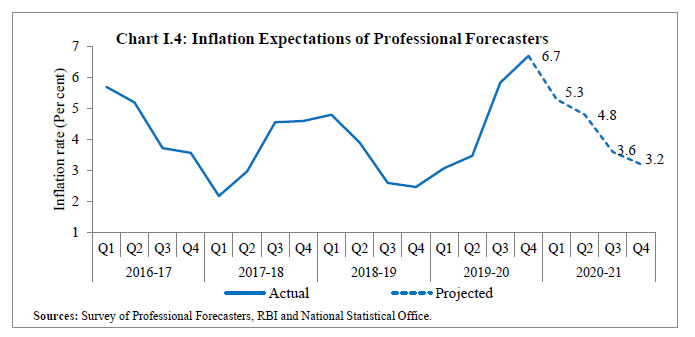

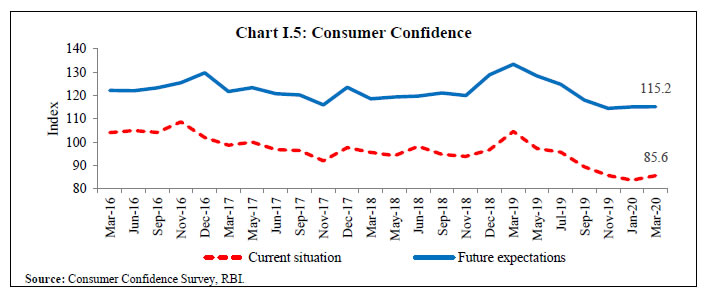

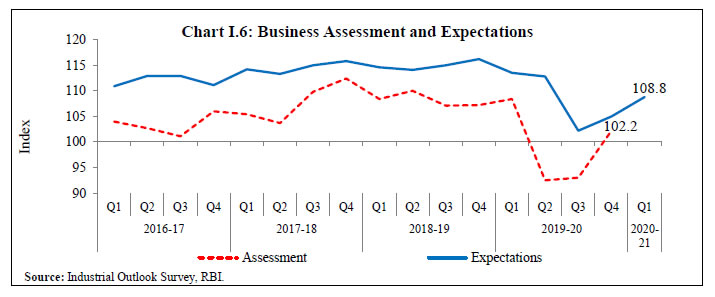

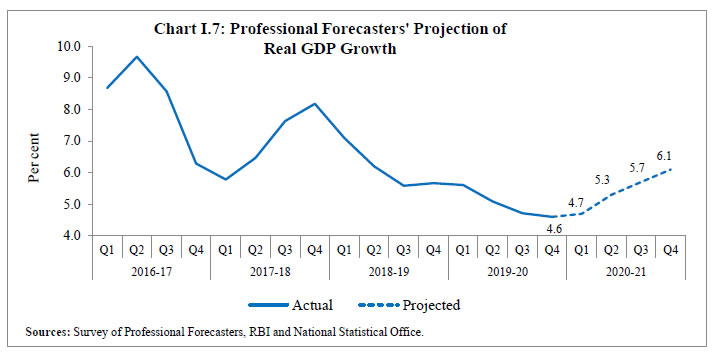

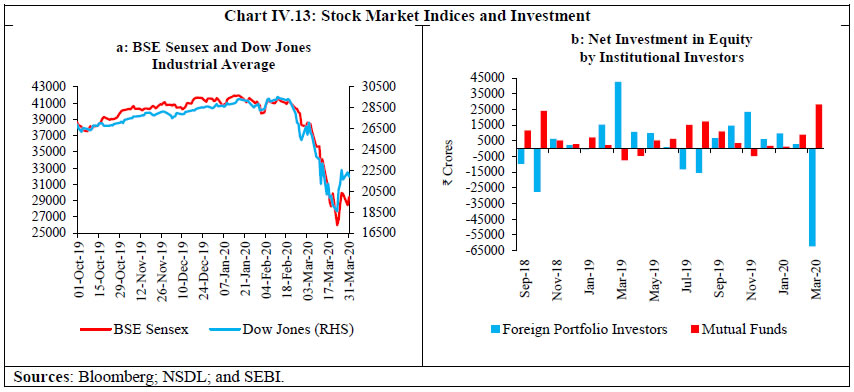

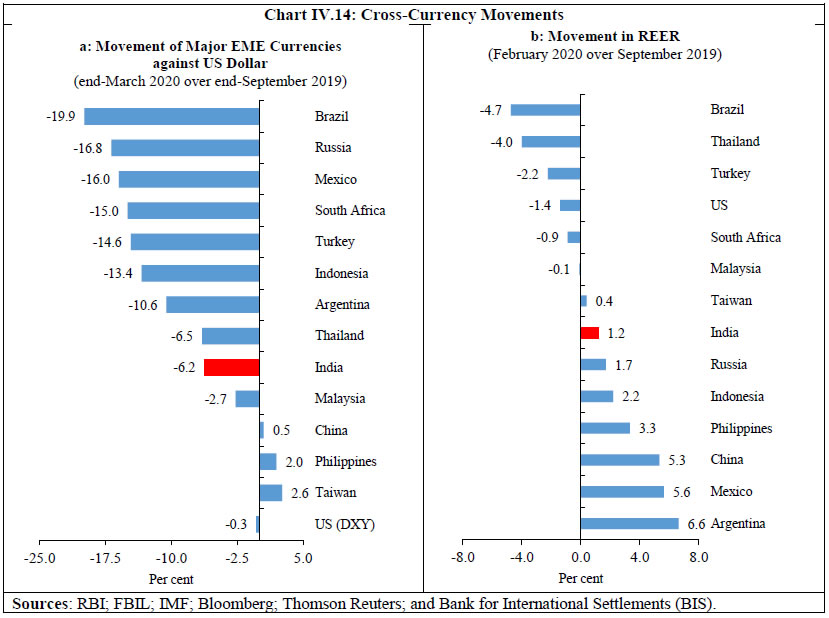

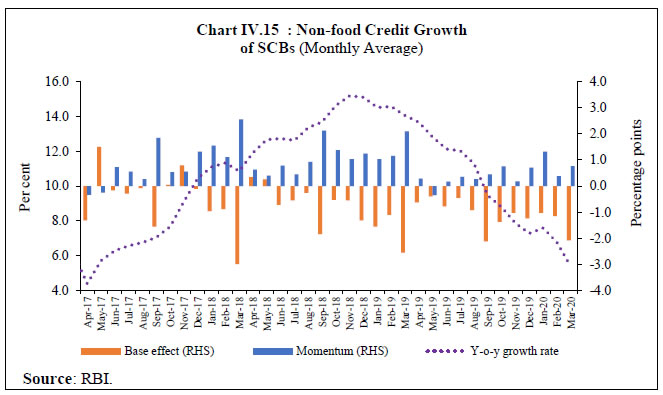

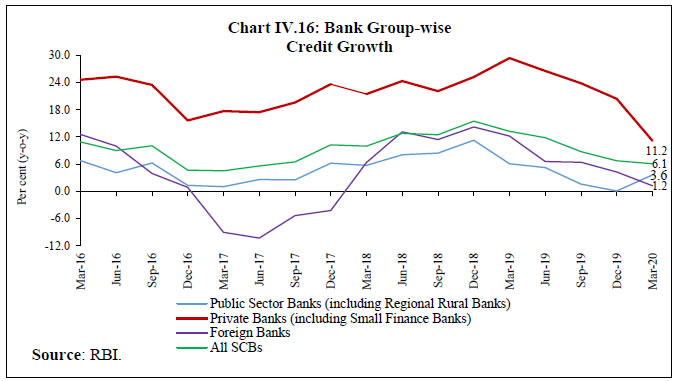

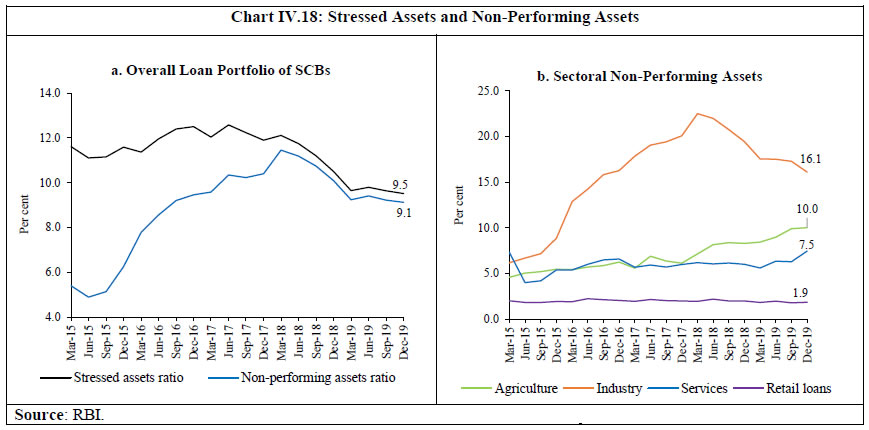

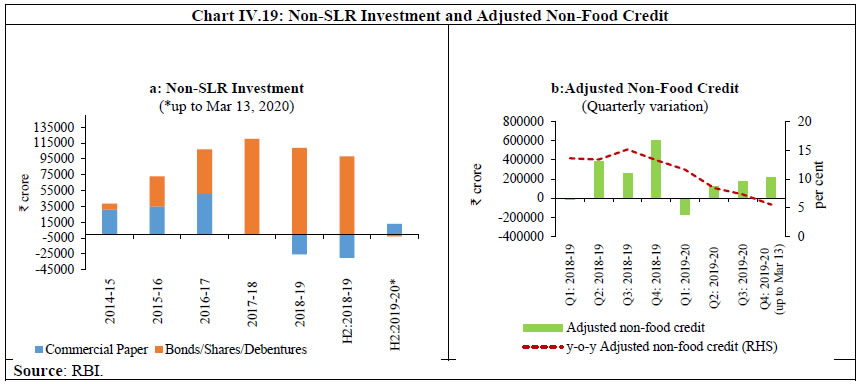

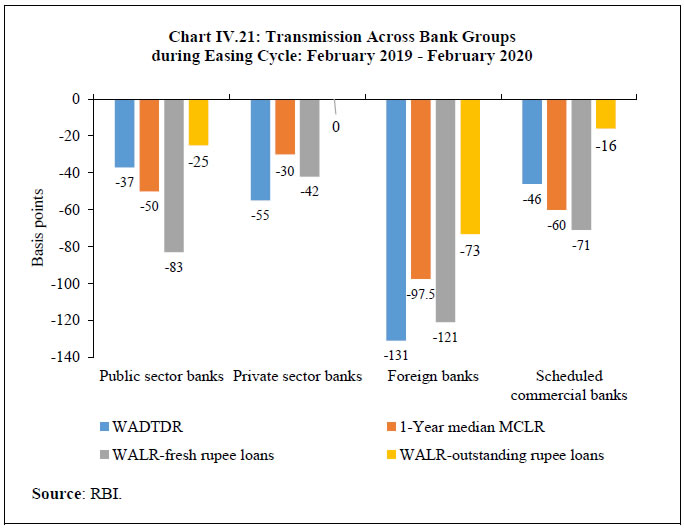

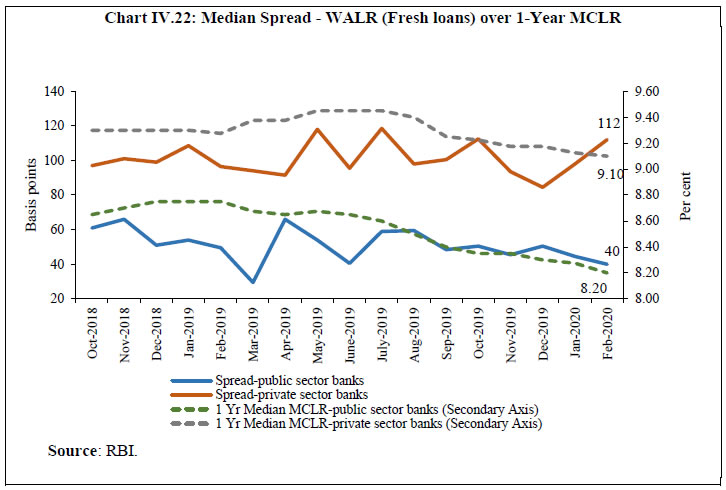

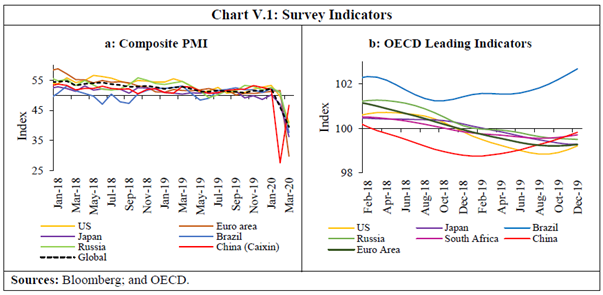

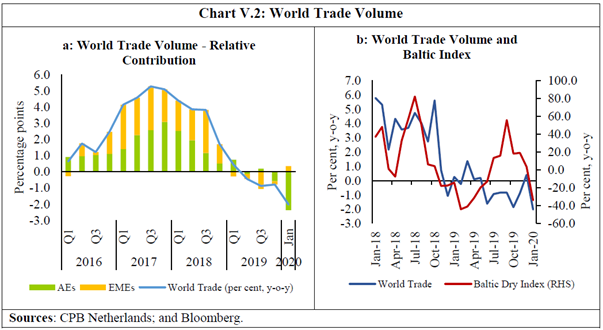

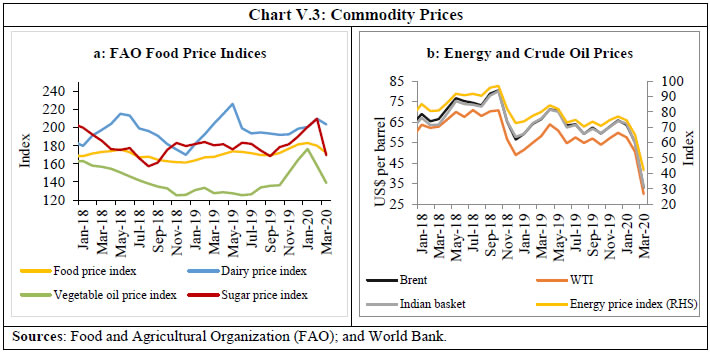

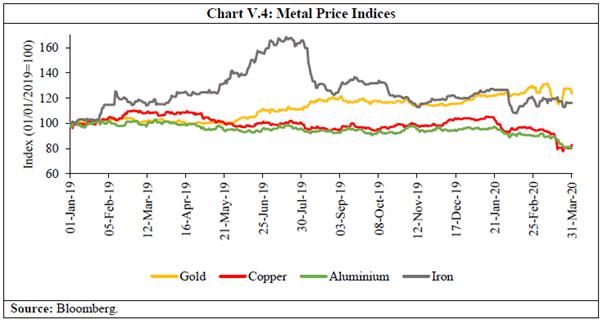

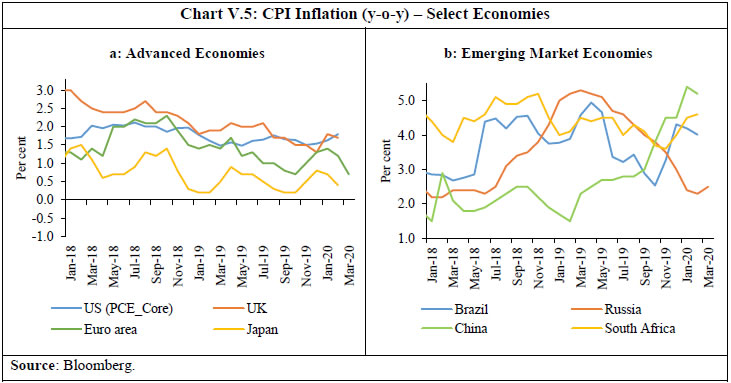

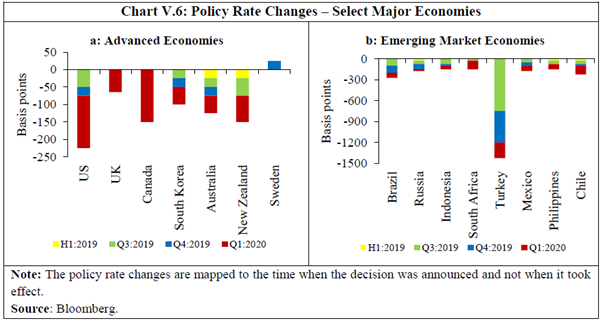

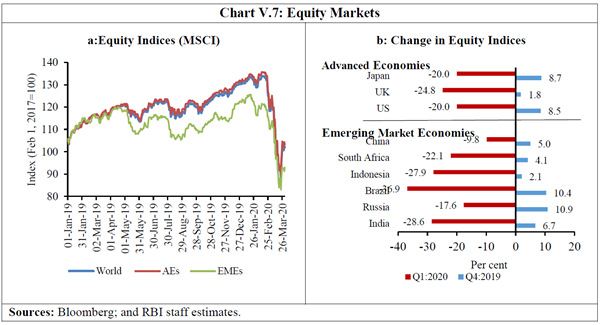

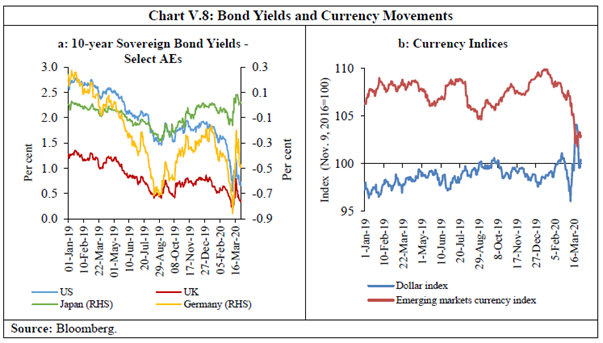

The global macroeconomic outlook is overcast with the COVID-19 pandemic, with massive dislocations in global production, supply chains, trade and tourism. Financial markets across the world are experiencing extreme volatility; global commodity prices, especially of crude oil, have declined sharply. COVID-19 would impact economic activity in India directly due to lockdowns, and through second round effects operating through global trade and growth. The impact of COVID-19 on inflation is ambiguous, with a possible decline in food prices likely to be offset by potential cost-push increases in prices of non-food items due to supply disruptions. As this Monetary Policy Report (MPR) goes for release, the global macroeconomic outlook is overcast with the COVID-19 pandemic. With over 12 lakh confirmed infections and over 67,000 deaths across 211 countries as of April 7, 2020 and counting, the sheer scale and speed of the unfolding human tragedy is overwhelming. The disruption of economic activity in a wide swathe of affected countries is set to intensify in the face of headwinds in the form of massive dislocations in global production, supply chains, trade and tourism. Global output is now seen as contracting in 2020. Financial markets across the world are experiencing extreme volatility: equity markets recorded sharp sell-offs, with volatility touching levels seen during the global financial crisis; flights to safety have taken down sovereign bond yields to record lows; risk spreads have widened; and financial conditions have tightened. Global commodity prices, especially of crude oil, have also declined sharply in anticipation of weakening global demand on the one hand, and the failed negotiations of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Russia, on the other. Many central banks have eased monetary, liquidity and regulatory policies to support domestic demand, including through emergency off-cycle meetings. Bilateral swap lines between some central banks that were deployed during the global financial crisis have been activated. G7 finance ministers and central bank governors have stated that they stand ready to cooperate further on timely and effective measures. G20 finance ministers and central bank governors have committed to use all available policy tools to deal with COVID-19. G20 Leaders have resolved to do whatever it takes to overcome the pandemic. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group are making available US$ 50 billion and US$ 14 billion, respectively, through various financing facilities to their membership to help them respond to the crisis. Turning to the domestic economy, India has not been spared from the exponential spread of COVID-19 and by April 7, more than 4,700 cases had been reported. While efforts are being mounted on a war footing to arrest its spread, COVID-19 would impact economic activity in India directly through domestic lockdown. Second round effects would operate through a severe slowdown in global trade and growth. More immediately, spillovers are being transmitted through finance and confidence channels to domestic financial markets. These effects and their interactions would inevitably accentuate the growth slowdown, which started in Q1:2018-19 and continued through H2:2019-20. Meanwhile, headline inflation stayed above the upper tolerance band of the inflation target band during December 2019-February 2020, led by a spike in vegetable prices. While it has peaked and vegetable prices are on the ebb, the impact of COVID-19 on inflation is ambiguous relative to that on growth, with a possible decline in prices of food items being offset by potential cost-push increases in prices of non-food items due to supply disruptions. Monetary Policy Committee: October 2019-March 2020 During October 2019-March 2020, the monetary policy committee (MPC) met four times. The meeting scheduled for March 31, April 1 and 3, 2020 was advanced to March 24, 26 and 27, 2020. In its October 2019 meeting, the MPC had noted that the continuing slowdown warranted intensified efforts to restore the growth momentum. With inflation expected to remain below target in the remaining period of 2019-20 and Q1:2020-21, the MPC took the view that policy space could be used to address growth concerns within the flexible inflation targeting mandate. Accordingly, it voted to reduce the policy repo rate by 25 basis points (bps) to 5.15 per cent (5 members voted for a reduction of 25 bps and one member voted for a reduction of 40 bps), and committed to continue with an accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive growth, while ensuring that inflation remained within the target. The MPC decided to hold the policy rate unchanged in its December 2019 and February 2020 meetings. While domestic demand conditions weakened further in the run-up to these meetings, inflation rose sharply and breached the upper tolerance level of the mandated inflation band in November and December 2019. Given the evolving growth-inflation dynamics, the MPC felt it appropriate to maintain status quo, although it voted to persevere with the accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive growth, given the space available for future policy action. In its off-cycle meeting in March, the MPC noted that macroeconomic risks brought on by the pandemic could be severe, both on the demand and supply sides, and stressed upon the need to do whatever is necessary to shield the domestic economy from the pandemic. The MPC reduced the policy repo rate by 75 bps to 4.4 per cent (4 members voted for a reduction of 75 bps and 2 members voted for a reduction of 50 bps). During February-March 2020, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) also undertook several measures to further improve liquidity, monetary transmission and credit flows to the economy, and provide relief on debt servicing (Chapter IV). The MPC’s voting pattern reflects the differences in individual members’ assessments, expectations and policy preferences, as also reflected in MPCs in other central banks (Table I.1). Macroeconomic Outlook Chapters II and III analyse macroeconomic developments during October 2019-March 2020 and explain the deviations of inflation and growth outcomes from projections. Turning to the outlook, the evolution of key macroeconomic and financial variables over the past six months warrants revisions in the baseline assumptions (Table I.2). First, international crude oil prices (Indian basket) have fluctuated in a wide range since the October 2019 MPR. These prices initially increased during late December 2019 and early January 2020 to around US$ 70 per barrel, triggered by US-Iran tensions. They subsequently softened, however, to reach US$ 51 by early March in anticipation of lower global demand following the outbreak of COVID-19 and its rapid geographical spread. Brent prices crashed to US$ 32 on March 9, 2020 following Saudi Arabia’s decision to cut prices and increase production over the failure to reach an agreement with Russia on production cuts. Brent fell further to US$ 23 on March 30, 2020 while US crude prices dipped briefly below US$ 20. Brent rebounded to US$ 34 per barrel on April 3. Given the current demand-supply assessment, the baseline scenario assumes crude oil prices (Indian basket) to average around US$ 35 per barrel during 2020-21 (Chart I.1).  Second, the nominal exchange rate (the Indian rupee or INR vis-à-vis the US dollar) exhibited sizable two-way movements during October-December 2019. The INR came under intensified and sustained depreciation pressures beginning mid-January, reflecting a generalised weakening of emerging market currencies amidst flights to safety. Accordingly, the baseline assumes an average of INR 75 per US dollar to reflect these recent developments. Third, even though uncertainties relating to US-China trade relations and Brexit have receded, the COVID-19 pandemic has taken over. This has cast a shadow on the macroeconomic outlook, with global supply chains, trade, tourism, and the hotel industry being severely affected. The World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) goods and services trade barometers indicate that world trade volume growth weakened in early 2020; it is expected to be debilitated further by the adverse impact of COVID-19. The IMF expects that the contraction in global output in 2020 could be as bad as or worse than in 2009. The depth of the recession and the pace of recovery in 2021 would depend on the speed of containment of the pandemic and the efficacy of monetary and fiscal policy actions by various countries. The slowdown could be more protracted in dire scenarios in which the duration of COVID-19 extends longer. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates suggest that annual global gross domestic product (GDP) growth could be lower by up to 2 percentage points for each month in which strict containment measures continue. If the shutdown continues for three months with no offsetting factors, annual GDP growth could be between 4-6 percentage points lower than it otherwise might have been. Headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation breached the upper tolerance band of the target in December 2019 and peaked in January 2020, before ebbing prices of vegetables, fruits and petroleum products produced a downward shift of 100 bps in February. The trajectory of inflation in the near-term is likely to be conditioned by the pace of reversal of the spike in vegetables prices, the dispersion of inflationary pressures across other food prices, the incidence of one-off cost-push effects on various elements of core inflation and especially, the evolution of the COVID-19 outbreak. Looking ahead, three months and one year ahead median inflation expectations of urban households softened by 10 bps and 20 bps, respectively, in the March 2020 round of the survey conducted by the RBI1. The proportion of respondents expecting the general price level to increase by more than the current rate also decreased for both three months and one year ahead horizons vis-à-vis the January 2020 round (Chart I.2). Although largely adaptive, inflation expectations of households and firms can shape future inflation through price and wage setting behaviour. According to the Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey for March 2020, inflation expectations moderated over the previous round2.  Manufacturing firms polled in the January-March 2020 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey expected an increase in selling prices as well as in the cost of raw materials in Q1:2020-21; nonetheless, pricing power of firms is expected to remain weak (Chart I.3)3. Purchasing managers’ surveys for manufacturing and services reported moderation in the rate of increase in input and output prices for March 2020.  Professional forecasters surveyed by the Reserve Bank in March 2020 expected CPI inflation to ease from 6.6 per cent in February 2020 to 5.3 per cent in Q1:2020-21 and 3.2 per cent by Q4:2020-21 (Chart I.4)4.  Thus, an array of forward-looking indicators is pointing to a much softer inflation trajectory. Looking ahead, the balance of inflation risks is slanted even further to the downside. First, food prices may soften under the beneficial effects of the record foodgrains and horticulture production, at least till the onset of the usual summer uptick. Second, the collapse in crude prices should work towards easing inflationary pressures, depending on the level of the pass-through to retail prices. All these signals are, however, heavily conditioned by the depth, spread and duration of COVID-19 and shifts in any of these characteristics of the pandemic can produce drastic changes in the outlook. In these conditions, forecasts are hazardous as they are subject to large revisions with every incoming data on the pandemic. The RBI Act, however, enjoins the Reserve Bank to publish and explain in the MPR, inter alia, the forecasts of inflation for 6-18 months from the date of its publication. Therefore, taking into account initial conditions, signals from forward-looking surveys and estimates from time series and structural models, CPI inflation is tentatively projected to ease from 4.8 per cent in Q1:2020-21 to 4.4 per cent in Q2, 2.7 per cent in Q3 and 2.4 per cent in Q4, with the caveat that in the prevailing high uncertainty, aggregate demand may weaken further than currently anticipated and ease core inflation further, while supply bottlenecks could exacerbate pressures more than expected. Per contra, a quick containment of COVID-19 could lead to faster recovery and, therefore, firmer inflation pressures. Given the lockdown, the compilation of the CPI for March and the following few months by the National Statistical Office could also become challenging. For 2021-22, assuming a normal monsoon and no major exogenous or policy shocks, structural model estimates indicate that inflation could move in a range of 3.6-3.8 per cent. Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, the outlook for growth for 2020-21 was looking up. First, the bumper rabi harvest and higher food prices during 2019-20 provided conducive conditions for the strengthening of rural demand. Second, the transmission of past reductions in the policy rate to bank lending rates has been improving, with favourable implications for both consumption and investment demand. Third, reductions in the goods and services tax (GST) rates, corporate tax rate cuts in September 2019 and measures to boost rural and infrastructure spending were directed at boosting domestic demand more generally. The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically altered this outlook. The global economy is expected to slump into recession in 2020, as post-COVID projections indicate. The sharp reduction in international crude oil prices, if sustained, could improve the country’s terms of trade, but the gain from this channel is not expected to offset the drag from the shutdown and loss of external demand. Turning to key messages from forward-looking surveys, the March 2020 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey showed that consumer confidence for the year ahead was expected to remain around its level recorded in the previous survey round in January 2020 (Chart I.5). However, an important caveat to the forward-looking surveys presented in this section is that they were completed before the nation-wide lockdown effective March 25.  Optimism in the manufacturing sector for the quarter ahead had improved in the January-March 2020 round of the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey, reflecting expectations of higher production, order books, capacity utilisation, employment conditions, exports and overall business situation (Chart I.6). In view of the intensification of COVID-19, a quick survey with select parameters was specially conducted during March 18-20 to capture business sentiments. From the limited responses received, a considerable worsening of the key demand indicators is seen in the outlook for Q1:2020-21.  Surveys by other agencies (conducted prior to the intensification of COVID-19) indicated optimism on future business expectations (Table I.3). According to the purchasing managers’ surveys for March 2020, one year ahead business expectations of firms in manufacturing slumped to its weakest level, driven by fears of prolonged disruption from COVID-19. Business expectations of firms in the services sector also fell. Professional forecasters polled in the March 2020 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey (conducted during March 6-19 before the announcement of the nation-wide lockdown) expected real GDP growth to recover from 4.6 per cent in Q4:2019-20 to 6.1 per cent in Q4:2020-21 (Chart I.7 and Table I.4).  Overall, apart from the continuing resilience of agriculture and allied activities, other sectors of the economy will be adversely impacted by the pandemic, depending upon its intensity, spread and duration. Relatively modest upsides are expected to emanate from monetary, fiscal and other policy measures and the early containment of COVID-19, if that occurs. Such uncertainties make the forecasting of inflation and growth highly challenging (Box I.1).

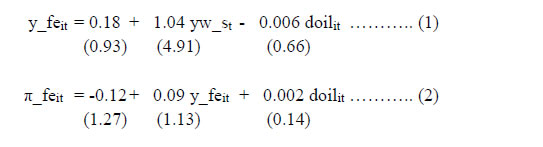

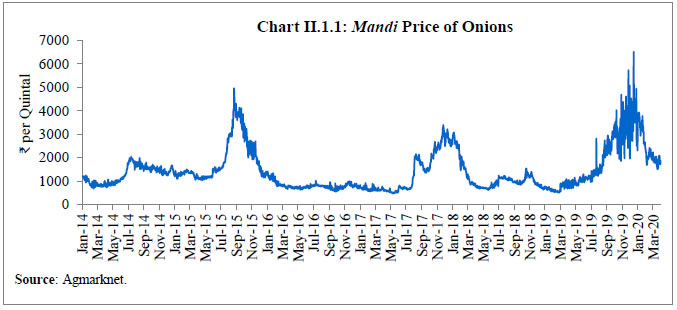

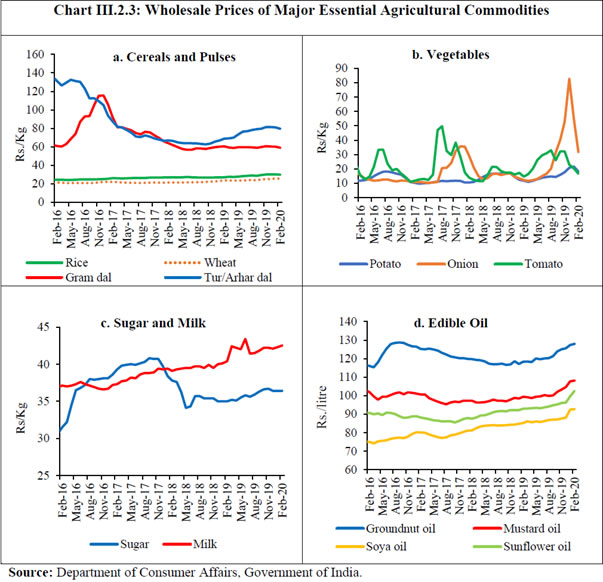

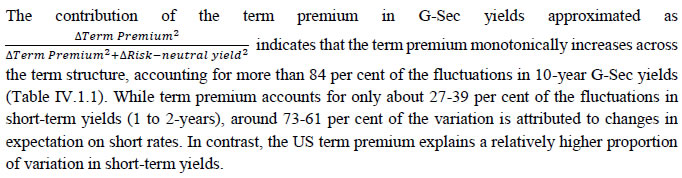

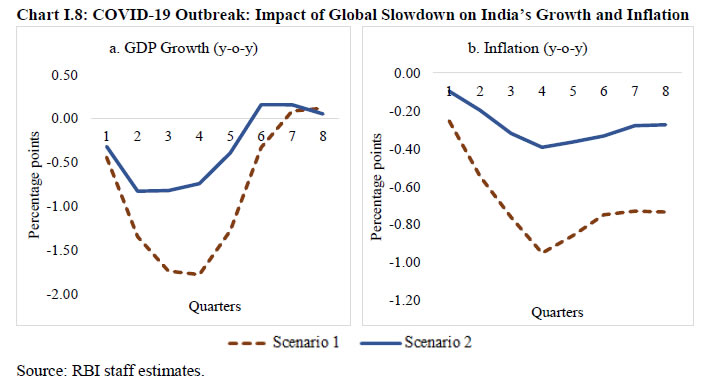

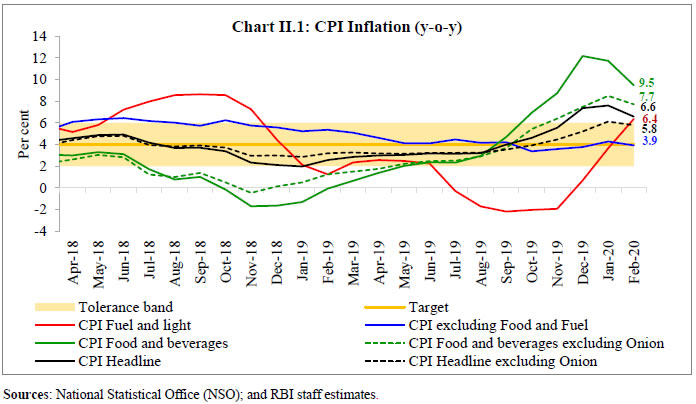

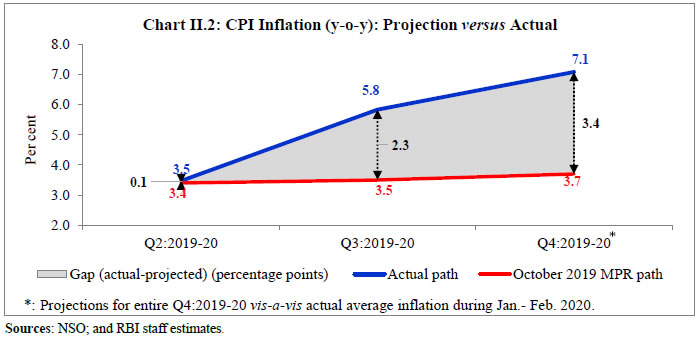

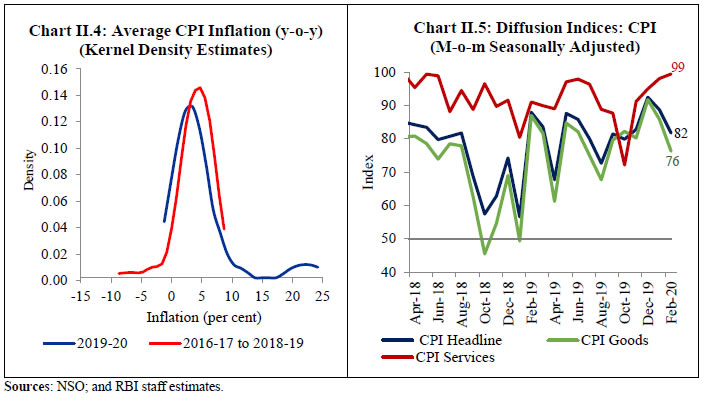

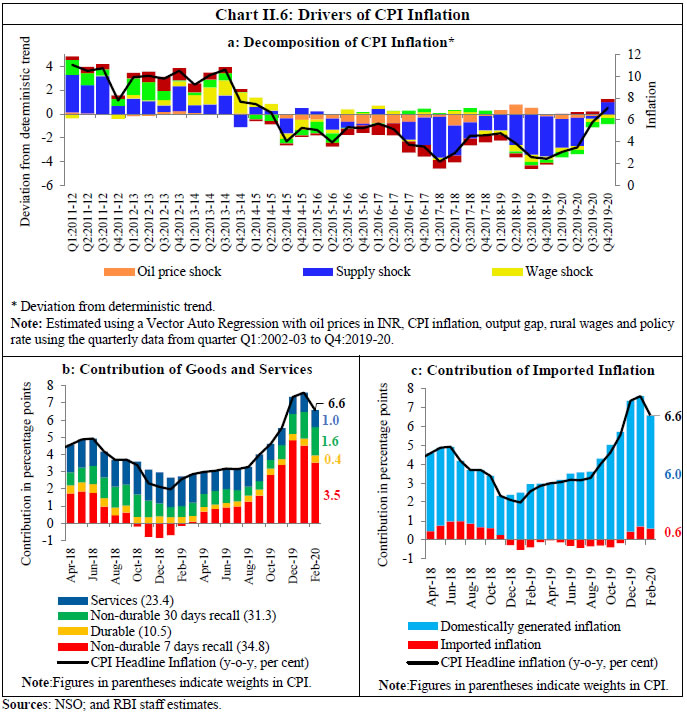

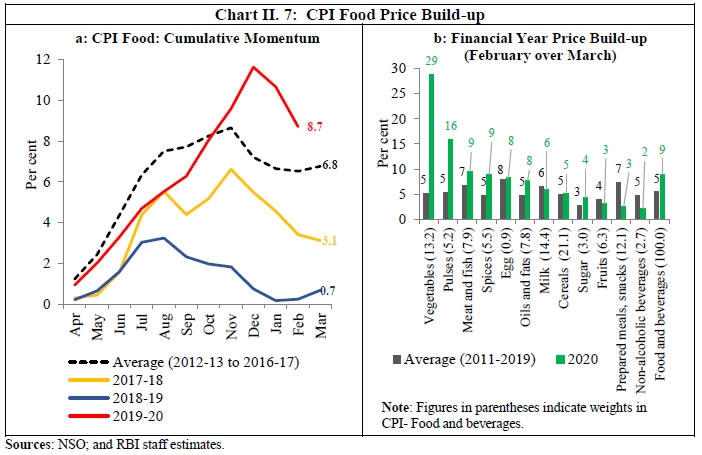

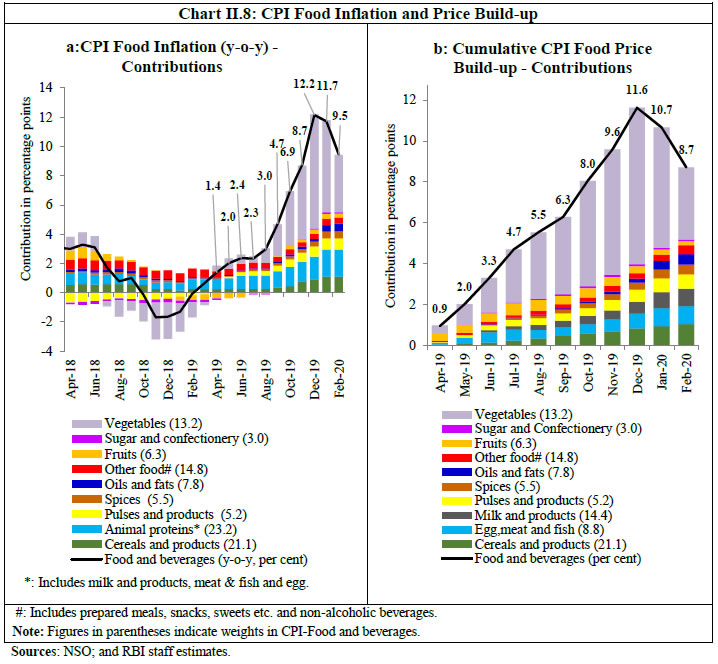

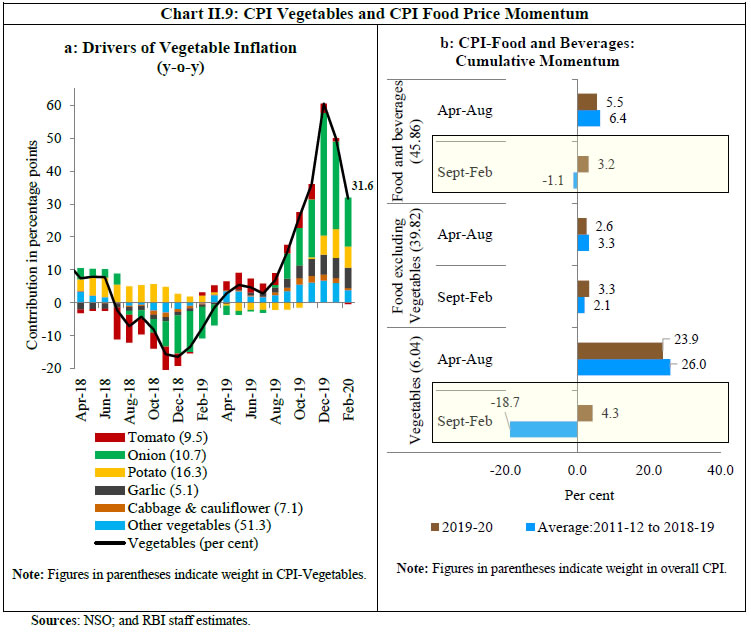

Against this backdrop and especially, the highly fluid circumstances in which incoming data produce shifts in the outlook for growth on a daily basis, forecasts for real GDP growth in India are not provided here, awaiting a clear fix on the intensity, spread and duration of COVID-19. To illustrate, in early March, the OECD projected the decline in global growth for 2020 in the range of 0.5-1.5 percentage points. More recently, with COVID-19 having spread to more than 200 countries, the IMF’s latest assessment is that global growth during 2020 could be negative vis-à-vis growth of 2.9 per cent in 2019 (which itself was a decadal low). Thus, global growth could be lower by three percentage points or more in 2020 relative to 2019. The possible impact of the global slowdown on India’s growth and inflation can be assessed by using the Quarterly Projection Model (QPM)7 under alternative scenarios. Scenario 1 assumes global growth in 2020 to be 3 percentage points lower than in 2019. Scenario 2 assumes that the outbreak is contained faster and the loss of global output growth is only 1.5 percentage points relative to 2019. Lower global output and demand can impact the Indian economy through a variety of channels. First, it can affect exports adversely, leading to lower domestic demand, growth and inflation. Second, international crude oil and other commodity prices have already softened sharply amidst high volatility and India, being a net importer, can benefit from the lower commodity prices. Finally, heightened global financial market volatility can feed into domestic financial markets and impact both growth and inflation. The QPM captures all these channels. The model’s simulations suggest that, on account of global factors, domestic growth could be lower, at its peak, by 180 bps in Scenario 1 and by 80 bps in Scenario 2. Inflation could be lower by 40-100 bps at its peak under the two scenarios (Chart I.8).  The COVID-19 pandemic poses upside and downside risks to the baseline assumptions and outlook. (i) Exchange Rate The exchange rate of the Indian rupee vis-à-vis the US dollar has moved in both directions in recent months. Renewed bouts of global financial market volatility caused by the uncertainty of macroeconomic impact of the COVID-19, as in February-March 2020, could exert pressure on the Indian rupee. Should the INR depreciate by 5 per cent from the baseline, inflation could edge up by around 20 bps while GDP growth could be higher by around 15 bps through increased net exports. In contrast, should COVID-19 normalise quickly, strong capital flows could revive. An appreciation of the INR by 5 per cent could moderate inflation by around 20 bps and GDP growth by around 15 bps vis-à-vis the baseline. (ii) International Crude Oil Prices Global crude oil prices have declined sharply from their October 2019 levels mainly due to weakening of global demand following the outbreak of COVID-19, and Saudi Arabia’s decision to cut prices. However, the short and medium-term outlook of oil remains highly uncertain. A V-shaped global recovery due to an early containment of the COVID-19 or renewed geopolitical tensions or an agreement on production cuts could lead to a sharp reversal in international crude oil prices. Should the Indian basket of crude oil prices increase by 10 per cent above the baseline assumption, inflation could be higher by 20 bps and growth could be weaker by around 15 bps. If COVID-19 were to persist longer, global economic activity and demand for crude oil could fall further in an environment of sustained oversupply due to Saudi Arabia’s decision to enhance production. Should the Indian basket crude price fall by 10 per cent vis-à-vis the baseline, inflation could ease by up to 20 bps and growth higher by up to 15 bps, depending upon the extent of pass-through to domestic product prices. (iii) Food Prices After remaining subdued for a considerable period, food inflation in India increased sharply during October 2019-January 2020, driven by a spike in vegetable prices. The baseline path assumes vegetable prices to fall rapidly in response to arrivals of rabi harvests and a normal south-west monsoon during 2020, which is supported by early signals of likely ENSO (El Nino – Southern Oscillation) neutral conditions. Adequate buffer stocks in cereals and a good rabi harvest (2019 season) could soften food inflation more than anticipated and pull down headline inflation by 50 bps below the baseline. On the other hand, a deficient or spatially skewed south-west monsoon, and an unexpected hardening of prices of non-vegetable food items could push headline inflation above the baseline by around 50 bps in 2020-21. COVID-19, the accompanying lockdowns and the expected contraction in global output in 2020 weigh heavily on the growth outlook. The actual outturn would depend upon the speed with which the outbreak is contained and economic activity returns to normalcy. Significant monetary and liquidity measures taken by the Reserve Bank and fiscal measures by the government would mitigate the adverse impact on domestic demand and help spur economic activity once normalcy is restored. Risks around the inflation projections appear balanced at this juncture and the tentative outlook is benign relative to recent history. But COVID-19 hangs over the future, like a spectre. _________________________________________________________ 1 The Reserve Bank’s inflation expectations survey of households is conducted in 18 cities and the results of the March 2020 survey undertaken during February 27– March 7, 2020 are based on responses from 5,912 households. 2 The Reserve Bank’s consumer confidence survey is conducted in 13 major cities and the results of the March 2020 round undertaken during February 27-March 7, 2020 are based on responses from 5,365 respondents. 3 The results of the January-March 2020 round of the industrial outlook survey (launched on January 30, 2020) are based on 860 responses received till March 18, 2020. 4 25 panellists participated in the March 2020 round of the Reserve Bank’s survey of professional forecasters, conducted during March 6-19, 2020. 5 Apart from the RBI, the analysis covers the central banks of Australia, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Hungary, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Romania, South Africa, Sweden, Turkey, UK, US and Euro area. For Romania and Turkey, the analysis is restricted to inflation forecasts in the absence of information on GDP growth forecasts. The focus of the analysis is on one-year ahead forecast errors (actual outturn less the forecast); therefore, the forecasts for the years 2018 and 2019 made in the last quarter of 2017 and 2018, respectively, are considered. For the RBI, the forecasts for the financial years 2018-19 and 2019-20 available in the February 2018 and February 2019 policy statements, respectively, are taken. 6 Global growth surprise is captured by actual global growth less the forecast made in the preceding year’s October edition of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook. Crude oil price surprise is measured as the percentage change in its local-currency price during the year from its level in the last quarter of the preceding year. 7 The QPM is a semi-structural, forward-looking, open economy, calibrated, gap model in the New Keynesian tradition and provides an internally consistent analysis of various feedback mechanisms. Consumer price inflation surged between October 2019 and January 2020 propelled by a vegetable price spike, particularly of onions and breached the upper tolerance threshold in December before moderating in February. Fuel prices emerged out of deflation in December. After touching a historic low in October, inflation in CPI excluding food and fuel edged up due to cost-push factors. Costs of farm inputs, industrial raw materials, agricultural and non-agricultural labourers’ nominal wages and organised sector staff costs remained muted. Headline inflation, measured by the consumer price index (CPI),1 had been trailing below target for thirteen consecutive months till Q2:2019-20 when a ratcheting up of vegetables prices – mainly those of onions – dispelled this environment of price stability. In the event, headline inflation breached the upper tolerance ceiling of 6 per cent by December 2019 and peaked at 7.6 per cent in January 2020 before moderating to 6.6 per cent in February. An unusually prolonged south-west monsoon and unseasonal rains ravaged the later part of the kharif harvest and produced an unprecedented rise in prices of onions. In fact, excluding onions, headline inflation would have been 4.5 per cent in Q3 and 5.9 per cent in Q4 (till February), underscoring the severity of the onion price shock. Fuel prices too moved out of five months of deflation into positive territory in December 2019 and increased sharply thereafter. Inflation excluding food and fuel – or core inflation – hardened in a sustained manner from a historic low of 3.4 per cent in October 2019 to 4.3 per cent in January 2020, propelled by a series of cost pushes before registering some moderation in February (Chart II.1).  The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 (amended in 2016) enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and explain the underlying reasons thereof. The Monetary Policy Report (MPR) of October 2019 had projected CPI inflation to remain range-bound in H2: 2019-20, at 3.5 per cent in Q3:2019-20 and at 3.7 per cent for Q4:2019-20. Actual inflation outcomes have overshot projections by a considerable margin – 2.3 percentage points in Q3 and 3.4 percentage points in Q4 (Chart II.2).  As stated earlier, the unanticipated and unparalleled spike in onion prices was the major source of deviation of headline inflation from projections. Unseasonal rains also delayed the seasonal winter moderation in prices of other vegetables, particularly those of potatoes. In addition, a larger than anticipated pick-up in cereals and milk prices due to kharif crop damage coming from the unseasonal rains, lower wheat imports and higher minimum support prices for wheat in the case of the former and an escalation in input costs in the case of the latter aggravated inflation pressures. CPI excluding food and fuel inflation also turned out to be a source of projection errors in Q4 due to a series of cost-push shocks – higher mobile phone tariffs; higher motor-vehicles prices due to the ongoing switchover to BS-VI2 compliant vehicles, higher gold prices reflecting international price movements; and higher services prices for sweepers, laundry, beauticians, bus fares – reflecting, inter alia, the spill over from higher food and fuel prices. In Q4:2019-20 (January-February), crude oil prices (Indian basket) softened from around US$ 63 per barrel at the time of the October MPR to US$ 55 per barrel by February, which helped temper these cost-push upsides. A decomposition of year-on-year (y-o-y) inflation suggests that a sharp increase in price momentum as well as unfavourable base effects were at work in H2:2019-203. As against the normal seasonal decline in food prices during Q3, the measured food price momentum in Q3 was positive registering the highest increase during any third quarter in the history of the index. As a result, food inflation surged to double digits by the end of Q3. Adverse base effects also pushed up fuel inflation. In January, food prices started to decline, but the persisting firmness in the momentum of core inflation pushed headline inflation to a peak in January. In February, headline inflation moderated coming from a sharp decline in food prices and waning of core inflation momentum (Chart II.3).  The distribution of inflation across CPI groups in 2019-20 has diverged considerably from the recent historical experience. Median inflation rate turned out to be lower compared with the last three-year average. However, 2019-20 exhibited high positive skew – as food sub-groups like vegetables exhibited very high inflation rates – compared to a negative skew for the historical average. As a result, the mean inflation rate for 2019-20 turned out to be considerably higher than the average of last 3 years (Chart II.4). Even as select food items swayed overall inflation rates in Q3:2019-20, a pick-up in the diffusion indices4 of price changes in CPI items, on a seasonally adjusted basis, also point to a broad-basing of price increases in the CPI basket – across goods and services – during this period. In Q4 so far, while almost all services have continued to register price increases, incidence of price increases in goods has seen some compression, largely on account of food items (Chart II.5).  A historical decomposition of inflation outcomes in H2:2019-20 reveals how adverse supply shocks overwhelmed the disinflationary impact of subdued domestic demand, both urban and rural (Chart II.6a).5 Perishable goods (non-durable goods with a 7-day recall6) – food items such as vegetables, milk and meat products – were the key drivers, contributing 1.3 percentage points to overall inflation in Q2, 3.7 percentage points in Q3 and 4.0 percentage points in Q4 so far (Chart II.6b). The contribution of less perishable goods (non-durable goods with a 30-day recall) also picked up from Q3:2019-20 due to cereals, pulses, sugar and petroleum products. Durable goods contribution to headline inflation, which remained largely steady during September-December – on an average at 36 bps – picked up to around 40 bps in January-February due to a rise in gold prices. Imported goods7 contributed negatively to overall inflation during September-November 2019, but their contribution turned positive during December 2019-February 2020 – on an average contributing around 60 bps to headline inflation, after a surge in energy and precious metals prices (Chart II.6c). The contribution of services to overall inflation remained sticky at around one percentage point as the sharp increase in mobile telecom charges during December 2019-January 2020 more than offset the moderation in inflation in house rentals, hospital services and tuition fees (Chart II.6b).  CPI Food Group Food and beverages (weight: 45.9 per cent in CPI) weighed heavily on changes in the overall CPI inflation during April 2019-February 2020, with the cumulative peak food price build-up in December turning out to be at a historical high (Chart II.7a & II.7b).  As a result, food inflation, which had ranged between 0.7 per cent and 4.7 per cent during March-September 2019, accelerated thereafter to peak at 12.2 per cent in December (Chart II.8a). Most of this upsurge was propelled by a vegetables price spike as a consequence of unseasonal rains; however, broad-basing of price pressures across the food category was observed in H2:2019-20 encompassing pulses, meat and fish, spices, eggs, cereals and milk (Chart II.8b). Subsequently, food inflation moderated sequentially in January and February 2020, with the delayed seasonal easing in vegetables prices. Price increases in respect of cereals (weight of 9.7 per cent in the CPI and 21.1 per cent in the food and beverages group) were sharper in H2: 2019-20. Wheat prices were driven up by higher procurement at upwardly revised minimum support prices (MSPs) and significantly lower imports [(-)39 per cent lower during April 2019-January 2020]. Non-public distribution system (PDS) rice prices emerged out of 11 months of deflation in October 2019 and gained momentum thereafter in the wake of damage to kharif crops due to unseasonal rain in October and early November 2019. They started to moderate from February 2020 due to large carry forward stocks, better rabi harvest prospects and lower exports.  Inflation in prices of vegetables (weight of 6.0 per cent in the CPI and 13.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) rose to double digits from September 2019 and peaked at 60.5 per cent in December 2019, reflecting the impact of crop losses and supply disruptions due to excessive and unseasonal rains (Chart II.9a). With the arrival of the late kharif harvest, a delayed seasonal easing in vegetables prices started in January 2020. The year 2019-20 will likely be unique in vegetable price pressures, as the severe supply shock completely overshadowed the seasonal pattern of usual winter easing in prices of vegetables, particularly onions, tomatoes and potatoes which brings relief from the price build-up during the preceding months of the year (Chart II.9b).  In India, a societal intolerance to inflation in double digits stands out starkly including in political discourse. This is best exemplified in social responses to inflation in onion prices. In 2019-20, onion prices surged from September 2019, with inflation in this category spiking to 327 per cent in December 2019 and contributing a staggering 4.7 percentage points to food inflation and 2.1 percentage points to headline inflation. This unpleasant inflation surprise exposed the time lags and lack of adequate band-width of supply-side measures such as imposing minimum export price (MEP) of US$ 850 per tonnes, banning export of onions, and imposing stock holding limits on wholesale traders and retailers in September 2019, as well as announcing import of 1.2 lakh tonnes of onions from Turkey, Afghanistan and Egypt during November-December 2019. It was only with the arrival of late kharif crop from January 2020 that onion prices began moderating. The ferocious pace of onion price escalation and the extent of spillovers highlight the urgent need for supply side reforms (Box II.1).

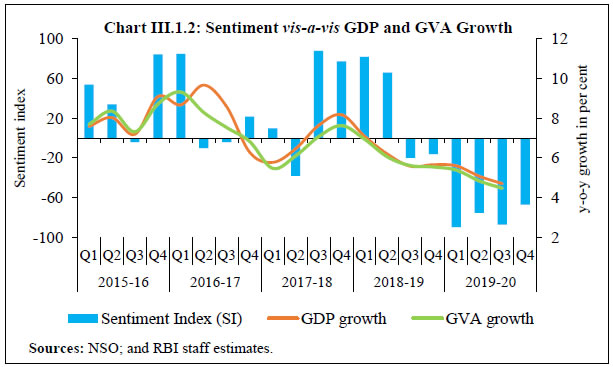

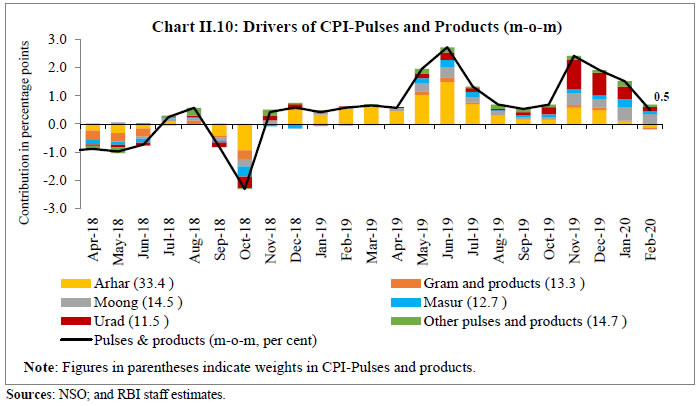

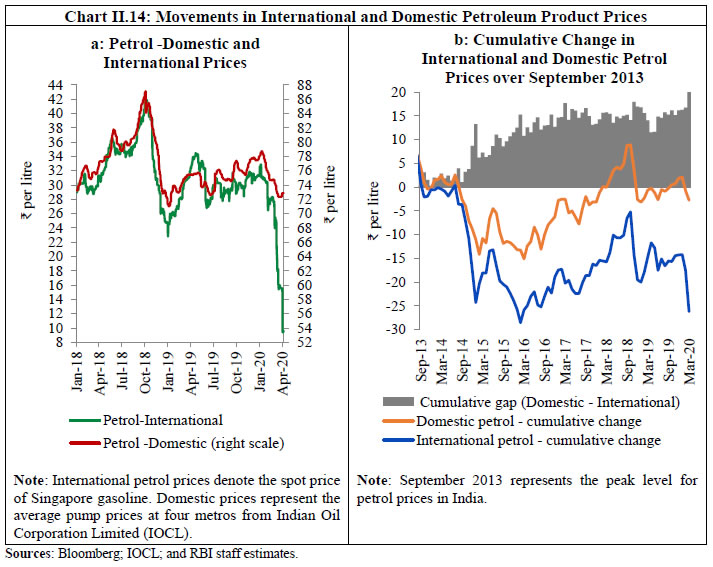

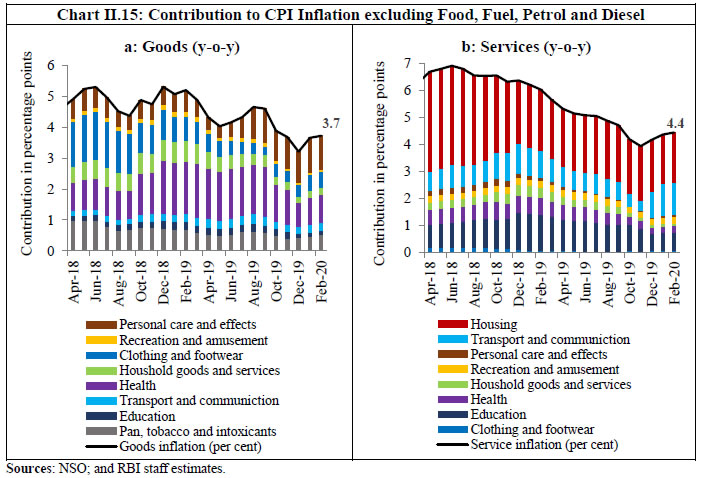

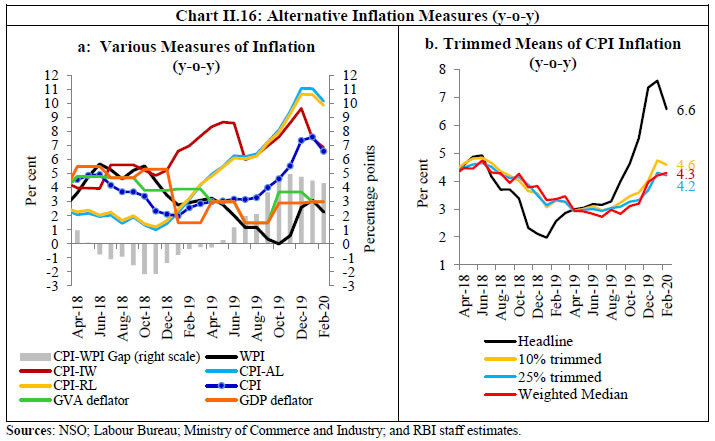

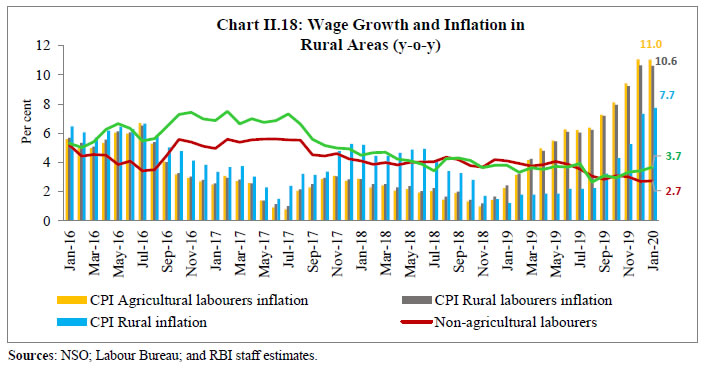

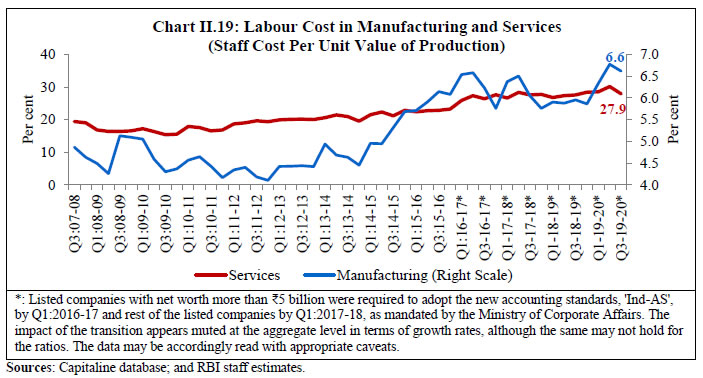

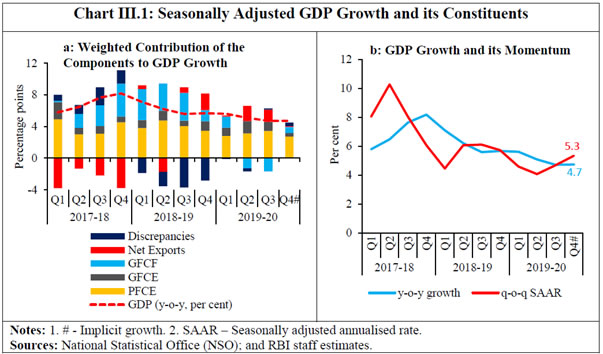

As regards other inflation-sensitive vegetables, potato prices remained in deflation from April 2019 to October 2019 despite a pick-up in prices during this period largely due to favourable base effects. The momentum of potato prices remained broadly positive during April 2019-January 2020, firmed up by crop loss and supply disruptions from excess/unseasonal rains during October-November 2019 in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, which was reflected in lower mandi arrivals. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that cyclone bulbul resulted in delayed sowing in West Bengal by around 20 days. As a result, potato price inflation rose to 62.9 per cent in January 2020, before moderating to 47.0 per cent in February 2020 due to fresh arrivals on the back of production turning out to be higher by 3.5 per cent in 2019-20. On the other hand, inflation in tomato prices moderated from its peak of 70 per cent in May 2019 and remained in high double digits during October-December 2019, reflecting untimely rains and associated supply disruptions. Beginning January 2020, tomato price inflation started moderating in the usual seasonal downturn and turned into deflation in February 2020 at (-)4.3 per cent. Prices of fruits (weight of 2.9 per cent in the CPI and 6.3 per cent within the food and beverages group) emerged out of 9 months of deflation in September 2019 to reach a level of 5.8 per cent in January 2020, primarily due to unfavourable base effects. By February 2020, fruit price inflation eased to 4.0 per cent. Banana prices have seen a sustained decline since November 2019. On the other hand, apple prices started a decline from August 2019 itself on the back of higher market arrivals consequent on production being higher by 18.0 per cent during 2019-20, although prices recovered somewhat since January 2020. Prices of pulses (weight of 2.4 per cent in the CPI and 5.2 per cent in the food and beverages group) were another source of inflation pressures with inflation in this category picking up considerably to reach 16.6 per cent in February 2020 from (-) 0.8 per cent in April 2019. This reflected a decline in kharif pulses production – by 2.1 per cent as per second advance estimates (AE) for 2019-20 over final estimates for 2018-19 – and especially urad production (by 27.1 per cent) on account of lower kharif sowing and unseasonal rains-led crop damages (Chart II.10). Even though imports were higher by 25 per cent during April 2019-January 2020 y-o-y, they failed to mitigate the rising price pressures in pulses.  Besides vegetables and pulses, prices of animal-based protein-rich items were another pressure point, contributing 20.4 per cent to overall food inflation in 2019-20. Inflation in the case of meat and fish remained elevated during April 2019-January 2020 and reached 10.6 per cent in January 2020 (highest in last 72 months). The prices of meat and fish increased significantly during the year (except during the lean season of August-October 2019) reflecting higher feed prices (especially, maize and soybean) on account of unseasonal rains, which accentuated seasonal price pressures. Concomitantly, egg price inflation also inched up to 10.5 per cent in January 2020 from 1.9 per cent in April 2019, but softened to 7.3 per cent in February 2020. Prices of both chicken and egg contracted sharply in February 2020 on account of a fall in consumption due to COVID-19 scare. Prices of milk and milk products (weight of 6.6 per cent in the CPI and 14.4 per cent in the food and beverages group) also contributed to higher food inflation. Co-operatives like Amul and Mother Dairy raised retail milk prices for the second time (first round in May 2019) in December 2019 in the range of ₹ 2-3 per litre due to increased procurement prices. Many state milk co-operatives also announced increases in prices, which kept the momentum of milk and its products at an elevated level during the year. Procurement prices were raised in response to the increase in the cost of production. Additionally, higher global prices for skimmed milk products also impacted domestic milk prices positively. Milk inflation hardened to a 56-month high of 6.0 per cent in February 2020. Sugar and confectionery prices (weight of 1.4 per cent in the CPI and 3.0 per cent in the food and beverages group) emerged out of four months of continuous deflation in October 2019, partly due to adverse base effects. Despite domestic and global production shortfalls, higher than expected domestic availability due to last year’s carry forward stock has helped keep domestic price pressures under check. Inflation in prices of edible oils and fats also edged up during the year from 0.7 per cent in April 2019 to 7.6 per cent in February 2020. Higher edible oils inflation emerged from a combination of rising international prices, lower domestic production of rabi oilseeds and adverse base effects. Higher milk prices also impacted the prices of ghee and butter. Price pressures picked up considerably in spices leading to a gradual hardening of inflation in this group to 8.8 per cent in February 2020 from 0.8 per cent in April 2019 due to overall lower production. CPI Fuel Group Prices of the CPI fuel group, which sank into deflation in July at (-)0.3 per cent, continued in negative territory till November 2019 as prices of key fuel items such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), firewood and chips and dung cake moved into deep deflation. The fuel group moved out of deflation in December registering a sharp rise thereafter, taking inflation in this category to 6.4 per cent by February. A pick-up in prices of electricity, LPG and firewood and chips and strong adverse base effects contributed to this upsurge (Chart II.11a). International propane and butane prices, which were declining through H1:2019-20, registered sustained price increases during October 2019-January 2020, accentuated by supply disruptions due to geopolitical tensions. These pressures were also transmitted to domestic LPG prices with a lag in February 2020 (Chart II.11b). Administered kerosene price inflation remained sticky and elevated reflecting calibrated price increases by oil marketing companies (OMCs) to phase out the fuel subsidy. By early February, however, administered prices were above market rates, particularly due to the sudden plunge in international prices. This led to some reduction in kerosene prices in the PDS in March (Chart II.11c).  CPI excluding Food and Fuel CPI inflation excluding food and fuel or core inflation picked up sequentially from 3.4 per cent in October 2019 to 4.3 per cent in January 2020, before registering some moderation in February 2020 (Chart II.12). In terms of components, the price build-up during 2019-20 was much lower than historical averages, barring for the transport and communication, and personal care and effects sub-groups (Chart II.13).  Volatile movements in international crude oil prices and the consequent increase in domestic pump prices mainly contributed to the upturn in CPI excluding food and fuel till January 2020 and the subsequent moderation in February. CPI petrol and diesel, which was in deflation for 11 months till November 2019, saw a sharp uptick in inflation during December 2019-January 2020 before moderating in February. Volatility in crude oil prices in H2:2019-20 emanated from a series of events starting with rising geo-political tensions in early September, followed by production cuts by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in early December and renewed geo-political tensions in early January. Crude oil prices moderated sharply from mid-January on easing of geo-political tensions, price war between OPEC and Russia, and fears of a global recession due to COVID-19. While the pass-through of collapse in international crude oil prices to domestic pump prices is still unfolding, its extent has been tempered by increases in taxes on petrol and diesel (Chart II.14a). Excise duties for petrol and diesel were increased by ₹ 3 per litre each on March 14, 2020 as international crude oil prices tumbled below US$ 40 per barrel. With this increase, the total excise duty on petrol and diesel works out to ₹ 22.98 per litre and ₹ 18.83 per litre, respectively. The divergence between international and domestic pump prices has now widened to highest levels seen in the recent period (Chart II.14b). CPI inflation excluding food, fuel, petrol and diesel troughed in December, before registering a sharp increase in Q4 so far (January-February). CPI inflation excluding food, fuel, petrol, diesel, gold, silver – which further excludes the volatile gold and silver price effects – also saw similar movements (Chart II.12).  A break-up of CPI excluding food, fuel, petrol and diesel into its good and services components, shows the impact of cost-push factors which reversed a sharp moderation in inflation in this category and hardened it during December 2019- January 2020 (Chart II.15).  Core goods prices inflation moderated sequentially till December 2019, caused by a broad-based fall in inflation across goods items, particularly health inflation due to large and favourable base effects. Goods inflation has been ticking up since January due to firming up of prices of clothing, pan, tobacco, medicines in the health sub-group following an increase in administered prices of essential medicines and automobiles in the transport and communication sub-group due to a rise in input costs and a switch-over in emission norms to BS-VI (Chart II.15a). Core services inflation moderated sharply during October-November 2019 due to a fall in inflation in domestic maid/cook and other household services; tuition fees in education services; house rentals; transport fares and mobile telephone charges under transportation and communication services. Mobile telephone charges have, however, increased (by close to 12 per cent between November 2019 and February 2020), following the increase in tariffs by major private mobile operators in early December. Bus fares and administered railway fares also increased during this period. As a result, transport and communication services inflation registered significant increases, pushing up overall services inflation. Reflecting subdued demand conditions, housing inflation softened throughout H2:2019-20. Education services inflation also remained soft during December 2019-February 2020 (Chart II.15b). Other Measures of Inflation Inflation in sectoral CPIs, i.e., for industrial workers (CPI-IW), agricultural labourers (CPI-AL) and rural labourers (CPI-RL), increased sharply during August-December 2019, driven up primarily by the unseasonal rise in food prices. The pace of increase, however, softened in January-February 2020, on the back of cooling of prices in the food group. Inflation in food and fuel components of CPI-AL and CPI-RL was higher than that in headline CPI. A larger share of food nudged overall inflation measured by these indices to double digit levels during December 2019-February 2020. In the case of CPI-IW, with the complete waning of the house rent allowance impact of the seventh central pay commission (CPC) after December 2019, inflation registered a sharp fall, closing the gap with headline CPI. Notwithstanding this ebbing, the latest increase in momentum in housing index in CPI-IW – which is revised once in six months, in January and July every year – contributed the largest upward push to CPI-IW in January 2020 (with a m-o-m increase of 3.7 percentage points). CPI-IW inflation decreased further in February 2020 due to sharp correction in food prices by 1.7 percentage points. Inflation in terms of the wholesale price index (WPI) fell during August-October 2019 in sharp contrast to the sectoral CPIs, due to a decline in prices of non-food manufactured products on account of the softening of global commodity prices. Subsequently, WPI inflation edged up in line with sectoral CPIs as wholesale food prices rose in December 2019-January 2020 before moderating again in February with easing of food prices. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross Value Added (GVA) deflators picked up in Q3:2019-20 after reaching a record low in Q2:2019-20, indicating a clear divergence with CPI and a broad alignment with WPI (Chart II.16a). Trimmed mean measures of inflation, obtained by statistically removing outliers and eliminating positive and negative skew, provide a measure of underlying inflation movements. Exclusion based measures of CPI also capture persistent trends in inflation by removing components that are considered idiosyncratic. Over the last six months, both trimmed means and exclusion-based measures, have firmed up (Charts II.12 and II.16b).  Underlying cost conditions have largely been in sync with inflation in terms of the WPI (Chart II.17). Inflation in terms of farm inputs and industrial raw material prices (extracted from WPI) moderated significantly after April 2019 and remained in negative territory during September-November 2019, before registering a pick up during December 2019-February 2020. The pick-up during December 2019-January 2020 partly reflected recovery in prices of global crude oil and petrochemicals as well as adverse base effects. In addition, cost of minerals and non-food articles also influenced the recent price dynamics of non-farm input costs. Among other industrial raw materials, domestic coal inflation picked up to 2.4 per cent during October 2019-February 2020 from 0.4 per cent in April 2019 in line with the increase in international coal prices. Prices of paper and paper products remained in deflation during July 2019-February 2020 due to lower raw material cost, including that of pulp. In the case of fibres, deflation persisted during August 2019-February 2020, following easing in prices of raw cotton and coir fibre, which also reflected in the contraction in cotton yarn prices during the same period. As regards farm sector inputs, inflation hardened in the case of fodder due to unseasonal rains, while some easing was observed in the case of fertilisers and pesticides reflecting generally subdued momentum in international fertiliser prices. Prices of electricity, which carry a high weight in both industrial and farm inputs, recorded a modest increase during the year, reflecting weak demand conditions. Inflation in terms of agricultural machinery and implements costs has also softened gradually during the current financial year.  Growth in nominal rural wages, both for agricultural and non-agricultural labourers, remained subdued averaging around 3.4 per cent and 3.3 per cent, respectively, during 2019-20 so far (up to January 2020) mainly reflecting continued slowdown in the construction sector (Chart II.18). With a sharp rise in rural retail inflation, however, real rural wage growth has been negative as derived from CPI-AL and CPI-RL measures since March 2019 and CPI-rural inflation since September 2019.  Growth in organised sector staff costs showed divergent movements for services and manufacturing firms. While staff cost growth of services firms increased in Q3:2019-20 over the previous quarter, it declined for manufacturing firms. Unit labour costs (ratio of staff cost to value of production in percentage terms) for companies in the manufacturing sector increased sequentially from 5.9 per cent in Q4:2018-19 to 6.3 per cent in Q1:2019-20 and further to 6.8 per cent in Q2 due to sequential decline in the value of production, alongside an increase in staff cost. In Q3:2019-20, unit labour cost for manufacturing moderated marginally. On the other hand, higher quarterly growth in value of production for firms in the services sector led to a fall of 220 basis points in unit labour cost from 30.1 per cent in Q2:2019-20 to 27.9 per cent in Q3 even as staff cost increased somewhat (Chart II.19).  Manufacturing firms participating in the Reserve Bank’s industrial outlook survey reported muted cost pressures in Q3:2019-20 and Q4. This reflected softening of inflation in farm and industrial raw materials in Q3 and weak metal and other commodity price pressures in Q4. A decline in cost of finance was also reported by the companies polled in Q3 and Q4. Cost pressures on account of salary outgoes also fell in Q3 and are expected to have remained weak in Q4. Weak demand conditions and muted input price pressures kept selling prices soft, with expectations showing only a muted uptick in Q4. While producers’ price expectations were subdued, inflation expectations of households, as measured in the Reserve Bank survey, softened. Manufacturing firms polled for the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) reported modest increases in input prices and stable output prices in Q4. Input prices, however, firmed up markedly in case of the PMI services firms in Q4 (up to February) driven by higher food, labour and material costs before slowing sharply in March 2020 amid lower food and fuel prices, and reduced demand. Prices charged by services firms remained broadly range bound in Q3 and Q4 but softened in March 2020 with some firms reducing their fees due to weak demand conditions. The inflation landscape changed dramatically during H2:2019-20 primarily on account of wide swings in onion prices. In Q4:2019-20, before the intensification of COVID-19, forward looking surveys were already indicating weak consumer confidence and low pricing power of firms. Since March 2020 the inflation outlook has become highly uncertain due to the COVID-19 outbreak turning into a pandemic. Crude oil prices have collapsed to lows not seen since early 2000s. With several major economies in lockdown mode, demand conditions may weaken sharply. Accordingly, countries across the world are bracing up for deflationary forces to take hold. India may not be immune to these extreme downside pressures imparted by the pandemic. With the entire country in lockdown, the NSO would face considerable challenges in compilation and measurement of consumer prices. ________________________________________________________________ 1 Headline inflation is measured by year-on-year changes in all India CPI Combined (Rural and Urban). 2 BS VI or Bharat Stage VI denotes the new emission standards that needs to be complied by all light and heavy vehicles, two and three wheeled vehicles manufactured on or after April 1, 2020. 3 A change in CPI year-on-year (y-o-y) inflation between any two months is the difference between the current month-on-month (m-o-m) change in the price index (momentum) and the m-o-m change in the price index 12 months earlier (base effect). For more details see Box I.1 of the MPR, September 2014. 4 The CPI diffusion index, a measure of dispersion of price changes, categorises items in the CPI basket according to whether their prices have risen, remained stagnant or fallen over the previous month. A reading above 50 for the diffusion index signals a broad expansion or generalisation of price increases and a reading below 50 signals a broad-based price decline. 5 Historical decompositions are used to estimate the contribution of each shock to the movements in inflation over the sample period, based on a vector auto regression (VAR) with the following variables (represented as the vector Yt) – the annual growth rate in crude oil prices; inflation; the output gap; the annual growth rate in rural wages and the policy repo rate. The VAR can be written in reduced form as: Yt =c + A Yt-1 + et ; where et represents a vector of shocks [oil price shock; supply shock (inflation shock); output gap shock; wage shock; and policy shock]. Using Wold decomposition, Yt can be represented as a function of its deterministic trend and sum of all the shocks et. This formulation facilitates decomposition of the deviation of inflation from its deterministic trend into the sum of contributions from various shocks. 6 The CPI weighting diagrams use the modified mixed reference period (MMRP) data based on the 2011-12 Consumer Expenditure Survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). Under MMRP, data on expenditure incurred are collected for frequently purchased items – for edible oil, eggs, fish, meat, vegetables, fruits, spices, beverages, processed foods, pan, tobacco and intoxicants, during the last seven days; for clothing, bedding, footwear, education, medical (institutional), durable goods, during the last 365 days; and for all other food, fuel and light, miscellaneous goods and services including non-institutional medical services, rents and taxes, during the last 30 days. 7 India’s imports are dominated by crude petroleum & petroleum products (around 25.0 per cent of the total imports. The other major components of imports are electronic goods (11.0 per cent), gold and silver (8.0 per cent), chemical and chemical products (6.0 per cent), metal and metal products (6.0 per cent), pears and precious stones (6.0 per cent) and vegetables oils (2.0 per cent). Also, the domestic prices of items such as raw cotton move in tandem with international cotton prices. The deterioration in aggregate demand conditions in 2019-20, was exacerbated by contraction in investment, and moderation in government expenditure in H2. On the supply side, agriculture and allied activities accelerated, buoyed by the late surge in south-west monsoon rainfall and bountiful north-east monsoon precipitation. However, industrial growth decelerated, led by a slowdown in manufacturing activity. Services sector activity moderated, pulled down by a slowdown in construction; trade, hotels, transport and communication; and public administration, defence and other services. The February 2020 data release by the National Statistical Office (NSO) reveals that a sequential slowdown set in upon the Indian economy from Q1:2018-19. Over H2:2018-19 and H1:2019-20, real GDP growth lost momentum further, averaging 5.5 per cent. The sub-5 per cent reading for Q3:2019-20 (4.7 per cent) has caused heightened uncertainty about the outlook. The oppressive force of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) on weak or moderating high frequency indicators of activity, barring agriculture, indicates that the implicit real GDP growth for Q4:2019-20 in the NSO’s data release could be undershot by a fair margin. In fact, the widening incidence of COVID-19 in March 2020 may produce downward pulls to Q4 GDP. Underlying this marked downturn relative to recent experience is the contraction in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) from Q2:2019-20. Consumption demand accelerated and sustained overall demand, driven mainly by a sharp pick up in government final consumption expenditure (GFCE). Net exports also contributed positively to aggregate demand, but essentially because the contraction in imports outpaced the decline in exports. On the supply side, agriculture and allied activities imparted momentum to gross value added (GVA) in Q2 and Q3, buoyed by increases in kharif and horticulture production. The industrial sector remained moribund, bound down by weak demand conditions, and hence weak pricing power. In the services sector, activity has been weakening through H2:2019-20 with high frequency indicators for January and February 2020 either moderating or declining, barring PMI, cement production and railway freight traffic. Public administration, defence and other services (PADO) remained robust in Q2 and Q3. However, during January-February 2020, centre’s revenue expenditure excluding interest payments and subsidies grew marginally. Beginning March, the lockdown in the wake of the outbreak of COVID-19 has choked manufacturing activities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in the manufacturing sector, dislocations of labour adversely impacted automobiles, electronic goods and appliances, and apparel. Services such as trade, tourism, airlines, the hospitality sector and construction have been hit hard. The deterioration in aggregate demand conditions in 2019-20, was exacerbated by contraction (1.3 per cent) in gross fixed capital formation, and moderation in government expenditure in H2. Although private consumption held up in sequential terms, it was slower in H2:2019-20 on a y-o-y basis (Chart III.1a and Table III.1). Overall, the drag on GDP growth in H2:2019-20 can be decoded to unfavourable base effects, since momentum – measured by the q-o-q seasonally adjusted annualised growth rate (SAAR) - accelerated in H2 (Chart III.1b). With COVID-19 having taken a grievous toll in February and particularly in March, it is unlikely that this momentum was sustained as the year closed. Accordingly, the NSO’s estimate of real GDP growth for the year as a whole at 5.0 per cent in 2019-20, which itself was down from 6.1 per cent in 2018-19, may be at risk.  In the absence of hard data on underlying activity from traditional sources, availability of high frequency information in large volumes, either structured or unstructured, varying in form and content, has opened up avenues for extracting meaningful signals on the state of the economy. A sentiment index (SI), prepared on the basis of daily news feed in print media is able to track economic activity relatively well in the Indian context. The SI indicates weak activity in Q4:2019-20 (Box III.1).

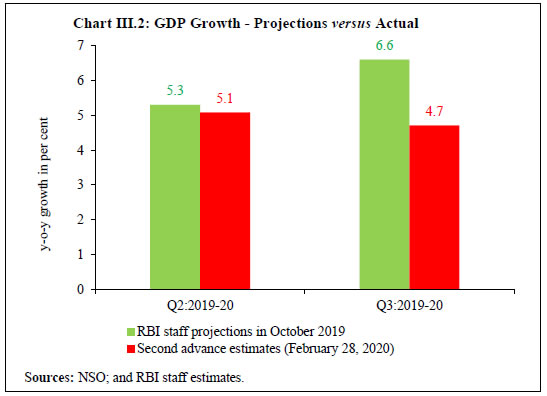

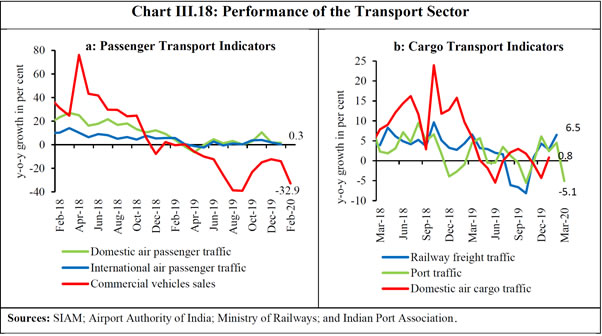

GDP Projections versus Actual Outcomes The October 2019 Monetary Policy Report (MPR) projected GDP growth at 5.3 per cent for Q2:2019-20, 6.6 per cent for Q3 and 7.2 per cent for Q4, with risks evenly balanced around this baseline path (Chart III.2). Actual outcomes in terms of the NSO’s second advance estimates (SAE) undershot these projections by 20 and 190 basis points in Q2 and Q3, respectively. The downward surprise in Q2 stemmed from a stronger than anticipated drag from gross fixed capital formation and marginal weakness in private final consumption expenditure. In Q3, projection errors emanated mainly from a steep unanticipated contraction in gross fixed capital formation, which was the deepest in the new series of GDP.  III.1.1 Private Final Consumption Expenditure Private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) remains the mainstay of aggregate demand, with its share at 57.6 per cent in H2:2019-20. The slowdown in PFCE in H2:2019-20 was caused by a combination of factors — weak rural demand due to depressed food prices/inflation in the previous two years; deceleration in rural wages; and downturn in labour-intensive exports which impacted rural consumption; and slowdown in urban consumption due to decelerating incomes (Chart III.3).  High frequency indicators of urban consumption demand present a subdued picture for Q4:2019-20 (Chart III.4a). Sales of passenger vehicles continued to contract in February 2020. Domestic air passenger traffic growth slowed in January 2020. Consumer durables growth contracted in January 2020. Even though there has been some uptick in vehicle loan growth for households and growth in credit card outstanding in February 2020, overall, urban consumption appears to have lost steam in Q4 with the outbreak of COVID-19 having accentuated the moderation (Chart III.4b).  Among the indicators of rural consumption, motorcycle sales remained in contraction in February 2020 (Chart III.5). This sector faces some uncertainty following the change in emission norms, which was to be effective from April. Tractor sales, however, improved in January and steadied further in February 2020, reflecting improved rabi sowing. The consumer non-durable segment remained in contraction, reflecting weak rural demand (Box III.2).

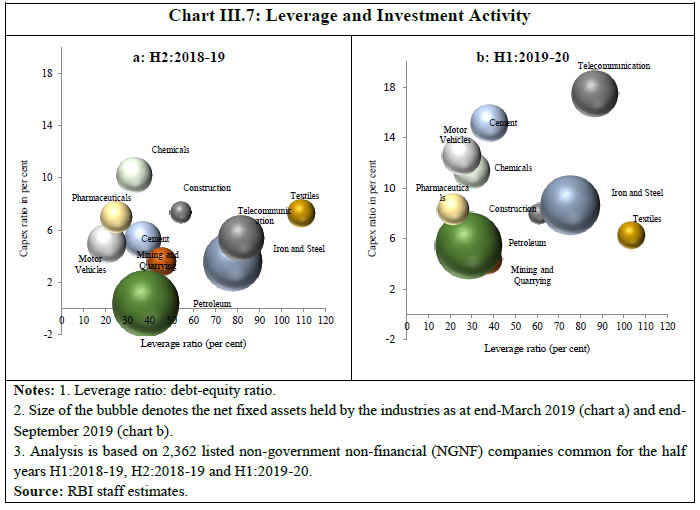

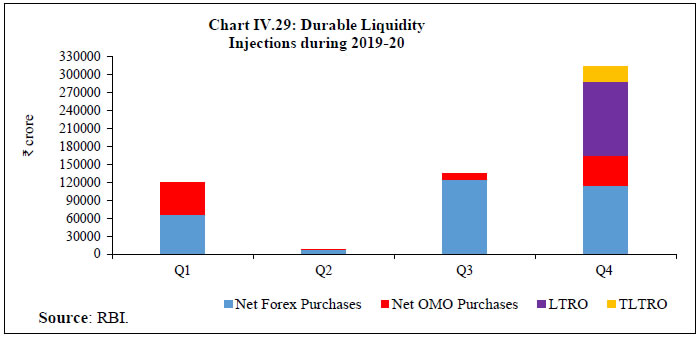

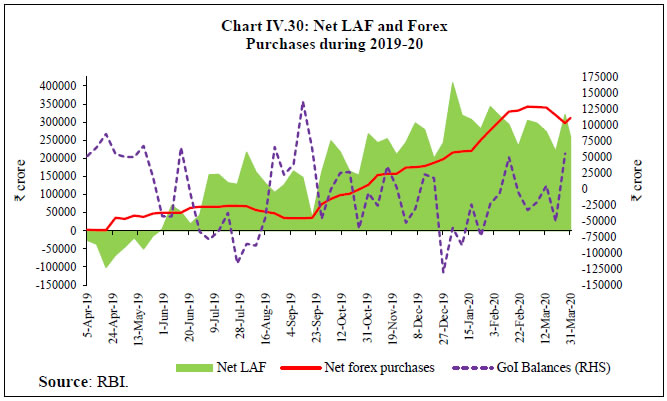

III.1.2 Gross Fixed Capital Formation Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) growth turned negative in Q2 and Q3:2019-20. Consequently, the share of GFCF in GDP dropped to 30.2 per cent in 2019-20 from 31.9 per cent a year ago. Two key indicators of investment demand, viz., production and imports of capital goods have remained in contraction in January/February 2020 as well (Chart III.6a). As regards construction activity, finished steel consumption contracted in February, while cement production grew significantly. The performance of software firms – a proxy for investment in intellectual property products – has remained resilient, as evident from the latest financial results. Seasonally adjusted capacity utilisation (CU-SA) in the manufacturing sector declined below the long-term average in Q3:2019-20, corroborating that the need for fresh investment is depressed as also reflected in a slowdown in adjusted non-food bank credit (ANFC) (Chart III.6b).  Half-yearly unaudited financial statements of listed non-government non-financial (NGNF) companies suggest a rise in the capex ratio3 in H1:2019-20 from H2:2018-19 across major industries such as motor vehicles, cement, petroleum, telecommunications and construction (Chart III.7). Funds mobilised by these corporates during H1:2019-20 were mainly used for fixed assets formation and deleveraging (reduced borrowing). The total cost of projects sanctioned/contracted by major financing channels also increased in H1:2019-20 over H1:2018-19.  As per the first revised estimates, gross domestic saving (GDS) rate decreased to 30.1 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 from 32.4 per cent in 2017-18. The saving rate of the household sector, which is a net supplier of funds to the economy, declined from 23.6 per cent of GDP in 2011-12 to 18.2 per cent in 2018-19. While the private corporate sector finances its investment predominantly through its own savings, the public sector continues to rely heavily on households for financing its deficit (Chart III.8). During April-December 2019, household financial savings appeared to have improved as households’ liabilities declined more than the increase in household deposits with scheduled commercial banks whereas their investment in insurance and mutual funds remained at the same level as in the previous year.  III.1.3 Government Expenditure Growth in government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) moderated in H2:2019-20 due to a sharp slowdown in Q4 as implicit in the SAE released by the NSO. During January-February 2020, revenue expenditure of the Centre grew by 3.9 per cent. In 2020-21, revenue expenditure is budgeted higher than in 2019-20 revised estimates (RE) (Table III.2). During 2019-20 (April-February), the fiscal position of the central government deteriorated mainly due to a decline in gross revenue under corporation tax, reflecting mid-year cut in tax rates. GST collections at ₹5.5 lakh crore were 89.5 per cent of RE and 4.5 per cent higher than a year ago. On the whole, direct taxes contracted by 3.3 per cent, while indirect taxes grew barely by 1.6 per cent in the first 11 months of the year, lower than the budget estimates (BE) (Chart III.9 a & b).  Revenue expenditure growth also stood lower than the RE mainly due to lower interest payments. Outgoes on account of major subsidies moderated from the BE of 1.4 per cent of GDP to 1.1 per cent in RE due to curtailment of on-budget food subsidy. Nonetheless, food subsidy continues to dominate the overall subsidy bill. Capital expenditure growth was also lower than in the RE. Under the provisions of section 4(3) of the revised FRBM Act, which can be invoked under specific conditions4, the Centre’s GFD was revised up to 3.8 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 (RE) from the budgeted 3.3 per cent, due to a shortfall in tax revenue and disinvestment proceeds. The implications of these evolving dynamics can be examined in a general equilibrium framework (Box III.3). The GFD is budgeted to moderate to 3.5 per cent of GDP in 2020-21 and in a glide path it will return to 3.1 per cent by 2022-23. Based on the latest available data, the gross fiscal deficit of 22 states increased to 2.9 per cent of their gross state domestic product (GSDP) in 2019-20 (RE) from the budgeted 2.5 per cent (Table III.3). The deviation was mainly caused by lower revenue – both own and central transfer – due to the slowdown in economic activity, which, in turn, induced states to cut both revenue and capital expenditure in an adverse feedback loop that further weakened aggregate demand. For 2020-21, states have budgeted a consolidated GFD of 2.4 per cent of GSDP, anticipating higher revenue and lower expenditure than a year ago. Under the centre’s market borrowing programme during 2019-20, that is managed by the Reserve Bank, gross borrowings were ₹2,68,000 crore during H2:2019-20, as compared to ₹2,83,000 crore during H2:2018-19, i.e., lower by 5.3 per cent than their level a year ago. Net market borrowings during H2:2019-20 at ₹1,33,000 crore were also 43.2 per cent lower. As part of active debt consolidation, seven tranches of switch operations worth ₹1,24,694 crore were carried out during H2:2019-20 with the objective of managing redemption and enhancing liquidity of government securities. Furthermore, cash management bills worth ₹2,50,000 crore were issued on seven occasions during H2:2019-20 to tide over frequent recourse to ways and means advances/overdrafts in the face of negative cash balances with the Reserve Bank. States completed their gross borrowings of ₹6,34,521 crore for the year (Table III.4).