INDIA’S FINANCIAL SECTOR

AN ASSESSMENT |

| |

Volume II

Overview Report |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

INDIA’S FINANCIAL SECTOR

AN ASSESSMENT |

| |

Volume II

Overview Report |

| |

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment

March 2009 |

| |

|

| |

The findings, views and recommendations expressed in this Report are entirely those of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment and should not be interpreted as the official views of the Reserve Bank of India or Government of India. |

| |

© Committee on Financial Sector Assessment, 2009 |

| |

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. |

| |

Sale Price: Rs. 2,000

Volumes I-VI (including one CD) |

| |

Exclusively distributed by: |

|

Foundation Books

An Imprint of Cambridge University Press India Pvt. Ltd,

Cambridge House, 4381/4, Ansari Road

Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002

Tel: + 91 11 43543500, Fax: + 91 11 23288534

www.cambridgeindia.org |

| |

Published by Dr. Mohua Roy, Director, Monetary Policy Department, Reserve Bank of India, Central Office, Mumbai - 400 001 and printed at Jayant Printery, 352/54, Girgaum Road, Murlidhar Temple Compound, Near Thakurdwar Post Office, Mumbai - 400 002. |

| |

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL |

|

|

Government of India

Ministry of Finance

Department of Economic Affairs

New Delhi |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Shaheed Bhagat Singh Marg

Mumbai |

|

| |

March 20, 2009 |

Dear Hon’ble Finance Minister |

| |

Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

We have great pleasure in submitting the Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment (CFSA). |

| |

The Government of India, in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India, constituted the CFSA to undertake a comprehensive self-assessment of Indias financial sector. The assessment has drawn upon the experience gained from the earlier self-assessment of international financial standards and codes and the standards assessments carried out by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The CFSA has followed a constructive and transparent approach to self-assessment keeping in view that such a self-assessment must be a rigorous and impartial exercise, with appropriate checks and balances.

The Report of the CFSA is being released in six volumes. Apart from the overview report and its executive summary, the other volumes comprise the Advisory Panel Reports on Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing, Financial Regulation and Supervision, Institutions and Market Structure, and Transparency Standards. Each of the Advisory Panel Reports has been reviewed by expert international peer reviewers.

Even while the impact of the recent global financial turmoil is still unfolding, the CFSA hopes that this assessment would enhance the understanding of the Indian financial sector, both in India and abroad. We would earnestly urge the Government of India, the Reserve Bank, SEBI, IRDA and other concerned market participants to promote wide dissemination and debate and initiate policy actions for improving the structural aspects of the Indian financial architecture.

We would also like to acknowledge the generous help and time given by the Chairmen and members of the Advisory Panels, the external peer reviewers and all officials and colleagues from the Government, regulatory and other institutions associated with this exercise. |

| |

Yours sincerely, |

With warm regards |

| |

|

|

(Ashok Chawla)

Co-Chairman and

Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India |

(Rakesh Mohan)

Chairman and

Deputy Governor

Reserve Bank of India |

|

| |

| |

Shri Pranab Mukherjee

Minister of Finance

Government of India

New Delhi - 110 001. |

| |

Composition of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

Chairman

Dr. Rakesh Mohan

Deputy Governor

Reserve Bank of India |

Co-Chairman

Shri Ashok Chawla

Secretary

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(from September 6, 2008) |

Dr. D. Subbarao

Former Finance Secretary

Government of India

(July 16, 2007 - September 5, 2008) |

Shri Ashok Jha

Former Finance Secretary

Government of India

(September 13, 2006 - July 15, 2007)

|

|

| |

Members |

| |

Shri Arun Ramanathan

Finance Secretary

Government of India

(from February 4, 2008) |

| |

Shri Vinod Rai

Former Secretary

Department of Financial Services

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(January 11, 2007 - February 3, 2008) |

| |

Dr. Arvind Virmani

Chief Economic Adviser

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance Government

of India |

| |

Dr. Alok Sheel

Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank)

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(from October 23, 2008) |

| |

Shri Madhusudan Prasad

Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank)

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(September 13, 2006 - October 22, 2008) |

| |

PREFACE |

| |

It is well-recognised, particularly after the East Asian crisis of 1997, that in an environment of large cross-border capital flows, which increased dramatically in the past two decades, the financial sector must be resilient and well-regulated. The fact that advanced financial markets, with well-tested monetary policy and regulatory frameworks, are also not free from such unexpected and extraordinary developments, has become very evident in the ongoing global financial crisis. In this context, the Financial Sector Assessment Programme (FSAP), a joint IMF/World Bank initiative introduced from May 1999 has aimed at identifying the strengths and vulnerabilities of a country’s financial system; to determine how key sources of risk are being managed; to ascertain the financial sectors’ developmental needs; and to help prioritise policy responses. These objectives are sought to be achieved through financial system stability assessment (FSSA) by undertaking macroeconomic surveillance and assessment of stability and soundness of the financial system in all its facets or the entire gamut of the financial system, viz., institutions, markets and infrastructure. A detailed assessment of observance of relevant financial standards and codes which gives rise to Reports on Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSCs) as a by-product is an integral part of FSAP – either undertaken as part of FSSA or independently. Overall, an FSAP enhances the scope for strengthening resilience and fostering financial stability within and helps promote smoother integration of economies with the global markets.

Member countries’ participation in both FSAPs/ROSCs and the publication of related reports is voluntary. Hence, the effectiveness of these assessments hinges upon the ownership of and commitment to the process from member country authorities. In the approximately ten years since the FSAP began, about three-quarters of IMF and World Bank member countries have completed or requested an initial assessment. The IMF/ World Bank has begun in recent times to focus upon updates of the FSAP. It is significant that among the countries that have not been comprehensively covered yet are some advanced countries among the G-7 and emerging markets among the G-20 Group – though some ROSCs have been completed by many of these countries in a sporadic manner.

India was one of the earliest member countries that participated voluntarily in the Financial Sector Assessment Programme (FSAP) exercise in 2000-01. Based on mutual consultations between the Government and the Reserve Bank, an elaborate self-assessment exercise on standards and codes was also conducted during 2000-02. In this exercise, India undertook a comprehensive self-assessment in all of 11 international financial standards and codes under the aegis of the Standing Committee on International Financial Standards and Codes, with Anti-Money Laundering (AML)-Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Recommendations assessed by a separate Working Group. These reports served as benchmarks for understanding the status as also for initiating several legal and institutional reforms in the financial sector. Thereafter, a review of the follow-up action taken on the recommendations of the 11 Groups mentioned above was completed in January 2005. India also completed assessments by the Bank-Fund of most of the financial standards by December 2004, except for those relating to insurance.

Building upon the experience thus far, the Government of India, in consultation with the Reserve Bank, decided to undertake a comprehensive self-assessment of the financial sector and for that purpose constituted the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment (CFSA) in September 2006. It needs to be mentioned that standards themselves are evolving and getting modified. Since the last FSAP in 2000-01, India has also undertaken a series of continuing reforms over this period. The financial sector reforms undertaken since the early 1990s have no doubt borne fruit: the country has reached a higher growth trajectory; savings have increased and investment into productive activities has expanded significantly; the financial markets have gained depth, vibrancy and more efficiency; and capacity-building overall is embedded in the system.

The CFSA, therefore, decided to undertake a full-scale and fresh assessment instead of updating earlier assessments. Also, instead of a selective approach, the CFSA decided to cover assessments of all financial standards and codes, so that a compact roadmap in a medium-term perspective for the entire financial sector could evolve in persevering with convergence towards international best practices. The current assessment, however, builds upon the earlier FSAP and ROSCs as needed and relevant. These reports were indeed educative. The current effort of the CFSA is, thus one more step in carrying forward the self-assessment approach, further enabling financial sector stability assessment and stress testing for the first time. The timely publication in September 2005 of the comprehensive Handbook on Financial Sector Assessment by the IMF and the World Bank enabled the initiation of this exercise. In addition, the assessors have also taken into account the Guidance notes, manuals and questionnaires that have been provided to the CFSA by the international standard-setting bodies. We take this opportunity to acknowledge and thank all of the institutions and standard-setters who have encouraged this effort.

The CFSA has followed a constructive and transparent approach to self-assessment, keeping particularly in view that such a self-assessment must be seen as a rigorous and impartial exercise. This unique experiment undertaken by India would, however, amply demonstrate that it is possible to achieve objectivity and credibility through self-assessments, if accompanied by appropriate checks and balances. In this regard, we would like to highlight the salient features of the broad approach and the work process designed by the CFSA.

Three Pillars of Assessment

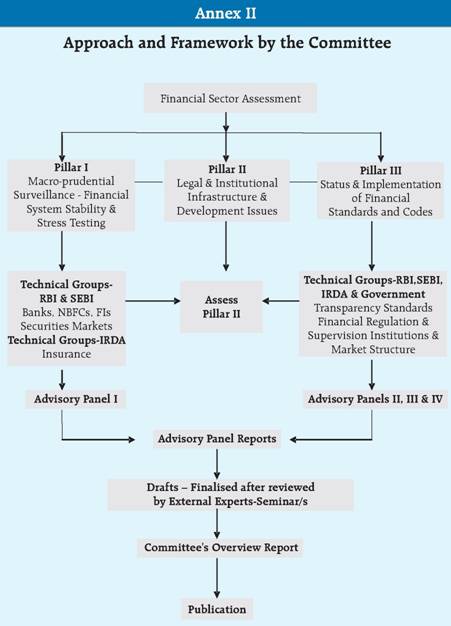

The CFSA followed a forward-looking and holistic approach to self-assessment based on three mutually-reinforcing pillars:

Pillar I : Financial stability assessment and stress testing;

Pillar II : Legal, infrastructural and market development issues; and,

Pillar III : Assessment of the status and implementation of international financial standards and codes.

The first pillar (Pillar I) is essentially in the nature of stability assessment which utilises analytical tools for quantifying the risks and vulnerabilities in the financial sector. The attempt entails an assessment of the systemic risks at the macro and sectoral levels. This involves a comprehensive analysis and interpretation of financial data pertaining to various constituents of the financial sector. viz., banking, securities, insurance, non-banking financial institutions, and corporates as also the fiscal and external sectors. It also includes stress testing for the key risks identified.

The second pillar (Pillar II) focuses on the developmental issues of the financial sector, concentrating upon the legal and institutional infrastructure for prudential regulation and supervision, payment and settlement systems, liquidity management and the crisis-mitigating financial safety nets. It also addresses the extent of coverage of the financial sector and the strength and adequacy of financial intermediation, both in the urban and rural segments.

The third analytical component of financial sector assessment encompasses a comprehensive assessment of the status and implementation of international financial standards and codes (Pillar III).

The CFSA envisaged that in view of the updates to standards that have taken place since the earlier FSAP in 2001, there is a need to take a fresh view on the developments in this area and their current status, duly taking into account the specific features of the Indian financial system. Towards this end, apart from considering the earlier review of self-assessment on standards and codes, the assessments of respective standards made by the IMF and the World Bank have also been taken on board.

Framework

We now provide an overview of the framework evolved by the CFSA in its work process.

First, as the assessment involved comprehensive technical knowledge in respective areas, the CFSA constituted Technical Groups comprising mainly officials with first-hand experience in handling the respective subject areas from the concerned regulatory agencies and the Government. The Technical Groups, based on their functional domain knowledge, thus undertook the preliminary assessment, and prepared technical notes and background material in the concerned subject areas. The greatest advantage of this approach has been that the concerned operating officials who have great familiarity with their own systems, who know where weaknesses exist and can also identify best alternative choices for finding solutions, were involved in this work. Moreover, this experience also operated as a very useful capacity-building exercise for the agencies and officials participating in it.

Second, whereas the preliminary work was done by the Technical Groups, these assessments served as inputs that needed a thorough review and finalisation by impartial experts with domain knowledge in the concerned areas. On this basis, Advisory Panels were constituted by the CFSA comprising non-official experts drawn from within the country. These Advisory Panels, however, had for support some senior officials with requisite domain knowledge, but only as special invitees and not as members. The Advisory Panels made their assessments after a thorough debate and rigorous scrutiny of inputs provided by Technical Groups. This ensured an impartial assessment.

Third, for further strengthening the credibility of assessment, it was considered necessary that the Advisory Panels’ assessments be peer reviewed by eminent external experts before finalisation of the panel reports. The Advisory Panels considered the peer reviewers’ comments and modified their assessments as appropriate. If they differed from peer reviewers, the reasons have been recorded. For a better exchange of views between the peer reviewers and the Advisory Panels, extensive conferences and seminars were held involving the respective peer reviewer, Advisory Panels and officials of the regulatory agencies at the highest levels.

The Advisory Panel reports, along with peer reviewers’ comments, are being publicly disclosed on the Reserve Bank and Government websites. The CFSA drew up its own overview report at the final stage, drawing upon the assessments, findings, and the recommendations of the Advisory Panels.

Thirty-one experts from diverse fields were identified as members of the four Advisory Panels. In addition, senior officials from the Government, the Reserve Bank, Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) were also inducted as ex officio special invitees to the panels.

The four Advisory Panels were supported by four Technical Groups with the involvement of more than 100 officials drawn from various agencies. The areas covered by the four Advisory Panels were:

- Advisory Panel on Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing, covered macro-prudential analysis and stress testing of the financial sector (Chairman: Shri M.B.N. Rao, former Chairman and Managing Director, Canara Bank).

- Advisory Panel on Financial Regulation and Supervision, covered banking regulation and supervision, securities market regulation and insurance regulation standards (Chairman: Shri M.S.Verma, former Chairman, State Bank of India).

- Advisory Panel on Institutions and Market Structure, covered standards regarding bankruptcy laws, corporate governance, accounting and auditing and, payment and settlement systems (Chairman, Shri C.M. Vasudev, former Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India).

- Advisory Panel on Transparency Standards, covered standards pertaining to monetary and financial policies, fiscal transparency and data dissemination issues (Chairman: Shri Nitin Desai, former Under-Secretary-General, United Nations).

|

Institutions/Agencies Involved

Yet another area of strength in the current process of self-assessment has been the spirit of inter-regulatory co-operation and association of several other agencies in the process of assessment. Taking into account the legal, regulatory and supervisory architecture in India, the CFSA felt the need for involving and associating closely all the major regulatory institutions, viz., the Reserve Bank, Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA). Depending upon the sectoral/functional distribution, several other regulatory and supervisory agencies in the financial system were also associated, besides involving concerned departments of the Central Government.

Involvement of Peer Reviewers

The CFSA identified 13 international experts and three Indian experts to peer review the relevant portions of the Panel reports in accordance with the reviewers’ areas of expertise. The draft Advisory Panel Reports were forwarded to the respective peer reviewers for their comments. To discuss the comments and suggestions of the peer reviewers, two brainstorming sessions interfacing the peer reviewers with the Panel and CFSA members were also held in Mumbai in the form of a two-day seminar on June 13-14, 2008 and a day’s conference on July 7, 2008. The views of the peer reviewers and the Advisory Panel’s stance have been incorporated in the Panel Reports. Depending upon the stance of the Panel, the texts of the Panel Reports were appropriately modified by the Panels.

We would like to acknowledge the significant contributions made by the experts of the four Advisory Panels chaired by Shri M.B.N. Rao, former Chairman and Managing Director, Canara Bank, Shri M.S. Verma, former Chairman, State Bank of India, Shri C.M. Vasudev, former Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India and Shri Nitin Desai, former Under-Secretary-General, United Nations. The CFSA expresses its sincere gratitude to Dr. Y.V. Reddy, then Governor, the Reserve Bank, Shri M. Damodaran, former Chairman, SEBI, Shri C.B. Bhave, Chairman, SEBI, Shri C.S. Rao, former Chairman, IRDA and Shri J. Harinarayan, Chairman, IRDA for extending wholehearted support to the Panels and the CFSA in undertaking their tasks. We are grateful to note that, despite the pressing demands on their time, the external peer reviewers have sent in their very insightful comments, in an honorary capacity. The Secretariat to the CFSA and the Technical Groups comprising officials drawn from the Reserve Bank, the SEBI, the IRDA, Government and other agencies have done outstanding background work for the Advisory Panels and the Committee. We also acknowledge the valuable contribution made by Shri T.C.A. Srinivasa Raghavan who edited and helped in producing these volumes for publication and Dr. Renu Gupta and Dr. Janak Raj for copy editing. A complete list of officials, non-officials, agencies associated and peer reviewers who contributed to this enormous task can be found as part of the Introductory Chapter to this Overview Report. The CFSA acknowledges their wholehearted and committed support. This whole exercise demonstrates the continuing commitment of Indian authorities to benefit from theory and practice, and the experiences of other countries, in our quest for global benchmarking of our financial sector standards.

The CFSA, while finalising its Overview Report, attempted to address issues arising out of the four Advisory Panel reports thematically into a set of key areas. As the Advisory Panels comprised independent non-official experts and their reports were peer reviewed by eminent external academics and policy-makers and are being transparently made public, their reports on a stand-alone basis deserve consideration for follow-up on their own merit. While the CFSA mostly endorsed the assessment, findings and recommendations of the Panels, it recognised at the same time that on certain aspects there were differing perspectives and stance taken by Panels on certain overlapping issues. Second, the CFSA also took into account the complexities of the current stage of economic and market development, including the Indian democratic polity, and has attempted to present a synthesised approach, whenever it viewed that issues were contestable. Third, while the membership of the CFSA along with the involvement of other regulators provides enormous comfort of ownership and commitment from authorities, the views of the Committee should for all practical purposes be treated nevertheless as independent and it is for the concerned authorities to chalk out an implementation plan for action.

The framework and work process, besides ensuring impartiality and credibility as brought out above, also carried with it certain other important benefits: |

- First, the direct official involvement at different levels brought with it enormous responsibility, ownership and commitment.

- Second, it ensured constructive pragmatism while addressing, in particular, contestable issues. In the current context of several established conventions and practices being re-examined in the light of the ongoing global financial crisis, there is a need to approach reforms in the financial sector, particularly from the point of view of emerging markets that are more vulnerable than any other, with a sense of humility. The CFSA carried this burden throughout.

- Third, the close involvement of officials and non-official experts in conjunction with external peer reviewers – an entirely new dimension added for the first time – meant that the process itself proved to be an investment in human resources producing an outcome that sensitised the financial sector agents and the internalised learning is expected to act as a stimulus for spearheading financial sector development and carrying the reform measures forward. No doubt, this has helped enhance the skill-sets within the financial sector, leading to significant capacity-building.

|

We would like to place on record our sincere and heartfelt appreciation of the valuable and painstaking contributions made by the Secretariat to the CFSA based in the Reserve Bank of India, headed by Shri K. Kanagasabapathy and supported by Dr. (Smt.) Mohua Roy, Shri Susobhan Sinha, Shri Sunil T. S. Nair, Dr. Saibal Ghosh, Shri D.Sathish Kumar, Shri Nishanth Gopinath, Shri Prabhat Gupta, Smt. P.K. Shahani, Shri A.B. Kulkarni, Shri R.J. Bhanse, Shri S.S. Jogale and Shri B.G. Koli. The Secretariat, besides organising the work of the CFSA, also co-ordinated the work relating to Technical Groups and Advisory Panels. The members of the Secretariat also actively associated themselves in preparing technical notes and background material at various stages and in organising conferences/ seminars and drafting the CFSA Report. Shri V.K. Sharma, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India helped greatly in overseeing the Secretariat and making sure that all inputs were available from the different departments of the Reserve Bank. In addition, Shri Sharma made significant conceptual and technical contribution in areas like the assessment of Business Continuity Management, development of liquidity ratios to assess liquidity risks and related capital charge as also duration of equity as a measure of interest rate risk. Shri Anand Sinha, Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India also contributed in conceptualising the scenario analysis to assess the liquidity position of banks. The CFSA also places on record the coordination and help received from Shri Anuj Arora, Shri Vanlalramsanga and Smt. Aparna Sinha, Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

It is with pleasure and with a sense of utmost humility that the CFSA presents the results of assessment of the India’s financial sector and a set of recommendations meant for the medium-term of about five years. The accent in this assessment is on transparency. Thus, where conflicting views have emerged among the Panels, the peer reviewers, and even among the members of the CFSA, they have been reported transparently. Regulation and development of the financial sector is a complex affair and there is room for constant debate and discussion, as shown particularly by the debate that is now being conducted in the wake of the ongoing global financial crisis. The approach taken in this assessment is to provide general directions and excessive specificity has been eschewed.

The assesssment and recommendations comprise six volumes consisting of the Executive Summary, the Overview Report of the CFSA and the Reports of the four Advisory Panels on Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing, Financial Regulation and Supervision, Institutions and Market Structure and Transparency Standards. These volumes should be viewed as a package complementing one another.

The CFSA hopes that these volumes greatly enhance the understanding of the Indian financial sector among a wide readership, both in India and abroad. The CFSA would earnestly urge the Government of India, the Reserve Bank, SEBI, IRDA and other concerned market agents to promote wide dissemination and debate and initiate policy actions for improving the structural aspects of the Indian financial architecture. |

| |

Ashok Chawla

Co-Chairman and

Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India |

Rakesh Mohan

Chairman and

Deputy Governor

Reserve Bank of India |

|

| |

March 20, 2009 |

| |

|

AACS |

As Applicable to Co-operative Societies |

AASs |

Auditing and Assurance Standards |

ADR |

American Depository Receipt |

ADs |

Authorised Dealers |

AFS |

Available for Sale |

AGL |

Aggregate Gap Limit |

AGM |

Annual General Meeting |

AIG |

American International Group |

ALM |

Asset-liability Management |

AMA |

Advanced Measurement Approach |

AMBI |

Association of Merchant Bankers of India |

AMFI |

Association of Mutual Funds in India |

AML |

Anti-money Laundering |

ANMI |

Association of NSE Members of India |

APC |

Auditing Practices Committee |

APG |

Asia/Pacific Group |

AS |

Accounting Standards |

ASB |

Accounting Standards Board |

ASSOCHAM |

Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India |

ATM |

Automated Teller Machine |

BC |

Business Correspondent |

BCBS |

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision |

BCM |

Business Continuity Management |

BCP |

Business Continuity Planning |

BCPs |

Basel Core Principles |

BCSBI |

Banking Codes and Standards Board of India |

BIFR |

Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction |

BIS |

Bank for International Settlements |

BOISL |

Bank of India Shareholding Limited |

BPLR |

Benchmark Prime Lending Rate |

BPO |

Business Process Outsourcing |

BPSS |

Board for Regulation and Supervision of Payment and Settlement Systems |

BR Act |

Banking Regulation Act |

BSE |

Bombay Stock Exchange |

CAD |

Current Account Deficit |

CAG |

Comptroller and Auditor General |

CAGR |

Compounded Annual Growth Rate |

CAL |

Capital Account Liberalisation |

CASA |

Current and Savings Account |

CBLO |

Collateralised Borrowing and Lending Obligation |

CCIL |

Clearing Corporation of India Ltd. |

CCPs |

Central Counterparties |

CD |

Certificate of Deposit |

CDD |

Customer Due Diligence |

CDS |

Credit Default Swap |

CDSL |

Central Depository Services (India) Ltd. |

CEO |

Chief Executive Officer |

CFP |

Contingency Funding Plan |

CFSA |

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

CFT |

Combating the Financing of Terrorism |

CIBIL |

Credit Information Bureau of India Ltd. |

CII |

Confederation of Indian Industry |

CIP |

Central Integrated Platform |

CIS |

Collective Investment Scheme |

CLS |

Continuous Linked Settlement |

CME |

Capital Market Exposure |

CP |

Commercial Paper |

CPI |

Consumer Price Index |

CPI-AL |

Consumer Price Index - Agricultural Labourers |

CPI-IW |

Consumer Price Index - Industrial Workers |

CPI-RL |

Consumer Price Index - Rural Labourers |

CPI-UNME |

Consumer Price Index - Urban Non-manual Employees |

CPSS |

Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems |

CRA |

Credit Rating Agencies |

CRAR |

Capital to Risk-weighted Assets Ratio |

CRISIL |

Credit Rating Information Services of India Ltd. |

CRR |

Cash Reserve Ratio |

CRT |

Credit Risk Transfer |

CSC |

Clients of Special Category |

CSGL |

Constitutents Subsidiary General Ledger |

CSO |

Central Statistical Organisation |

CTR |

Cash Transactions Report |

CVC |

Central Vigilance Commission |

DBOD |

Department of Banking Operations and Development |

DCCBs |

District Central Co-operative Banks |

DEA |

Data Envelopment Analysis |

DFIs |

Development Financial Institutions |

DICGC |

Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation |

DIF |

Deposit Insurance Fund |

DIP |

Disclosure and Investor Protection |

DIPP |

Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion |

DMO |

Debt Management Office |

DoE |

Duration of Equity |

DP |

Depository Participant |

DQAF |

Data Quality Assessment Framework |

DR |

Disaster Recovery |

DRAT |

Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal |

DRR |

Designated Reserve Ratio |

DRT |

Debt Recovery Tribunal |

DvP |

Delivery versus Payment |

EaR |

Earnings at Risk |

ECS |

Electronic Clearing System |

EFT |

Electronic Funds Transfer |

EGM |

Extraordinary General Meeting |

ELSS |

Equity-linked Savings Scheme |

EMEs |

Emerging Market Economies |

ESOP |

Employee Stock Option Plan |

EWS |

Economically Weaker Sections |

FATF |

Financial Action Task Force |

FBs |

Foreign Banks |

FCAC |

Fuller Capital Account Convertibility |

FCs |

Financial Conglomerates |

FDI |

Foreign Direct Investment |

FEDAI |

Foreign Exchange Dealers’ Association of India |

FEMA |

Foreign Exchange Management Act |

FERA |

Foreign Exchange Regulation Act |

FFMCs |

Full-fledged Money Changers |

FICCI |

Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

FII |

Foreign Institutional Investor |

FIMMDA |

Fixed Income Money Market and Derivatives Association of India |

FIU |

Financial Intelligence Unit |

FOMC |

Federal Open Market Committee |

FPI |

Foreign Portfolio Investment |

FPSBI |

Financial Planning Standards Board of India |

FRB |

Federal Reserve Bank |

FRBM |

Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management |

FRRB |

Financial Reporting Review Board |

FSA |

Financial Services Authority |

FSAP |

Financial Sector Assessment Program |

FSF |

Financial Stability Forum |

FSIs |

Financial Soundness Indicators |

FSRB |

FATF-style Regional Body |

GAAP |

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles |

GASAB |

Government Accounting Standards Advisory Board |

GB |

Gramin Bank |

GCC |

General Credit Card |

GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

GDR |

Global Depository Receipt |

GFD |

Gross Fiscal Deficit |

GFS |

Government Finance Statistics |

GFSM |

Government Finance Statistics Manual |

GLB |

Gramm-Leach-Bliley |

GS |

Government Securities |

HFCs |

Housing Finance Companies |

HFT |

Held for Trading |

HHI |

Herfindahl Index |

HLCCFM |

High Level Co-ordination Committee on Financial Markets |

HR |

Human Resources |

HTM |

Held to Maturity |

IAASB |

International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board |

IADI |

Insurance Association of Deposit Insurers |

IAIS |

International Association of Insurance Supervisors |

IAPC |

International Auditing Practices Committee |

IAS |

International Accounting Standards |

IASB |

International Accounting Standards Board |

IBA |

Indian Banks’ Association |

ICAAP |

International Capital Adequacy Assessment Process |

ICAI |

Institute of Chartered Accountants of India |

ICICI |

Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India Ltd. |

ICOR |

Incremental Capital-Output Ratio |

ICPs |

Insurance Core Principles |

ICSI |

Institute of Companies Secretaries of India |

ICWAI |

Institute of Cost and Works Accountants of India |

IDL |

Intra-day Liquidity |

IFCI |

Industrial Finance Corporation of India Ltd. |

IFRIC |

International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee |

IFRS |

International Financial Reporting Standards |

IGFRS |

Indian Government Financial Reporting Standards |

IMF |

International Monetary Fund |

IMSS |

Integrated Market Surveillance System |

IOSCO |

International Organisation of Securities Commission |

IPOs |

Initial Public Offers |

IR |

Industrial Relations |

IRB |

Internal Ratings-based Approach |

IRDA |

Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority |

IRS |

Interest Rate Swaps |

ISA |

International Standards on Auditing |

JLG |

Joint Liability Group |

KCC |

Kisan Credit Card |

KYC |

Know Your Customer |

LABs |

Local Area Banks |

LAF |

Liquidity Adjustment Facility |

LDC |

Less Developed Countries |

LIB OR |

London Inter-bank Offer Rate |

LIC |

Life Insurance Corporation |

LIG |

Low-income Group |

LoC |

Line of Credit |

LoLR |

Lender of Last Resort |

LtV |

Loan to Value |

MCA |

Ministry of Corporate Affairs |

MFI |

Micro-finance Institutions |

MoU |

Memorandum of Understanding |

MPC |

Monetary Policy Committee |

MRTP |

Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices |

MSS |

Market Stabilisation Scheme |

MTM |

Mark-to-market |

NABARD |

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development |

NACAS |

National Advisory Committee on Accounting Standards |

NASD |

National Association of Securities Dealers |

NASDAQ |

National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations |

NBFC-D |

Deposits taking Non-banking Financial Companies |

NBFC-ND |

Non-deposit taking Non-banking Financial Companies |

NBFC-ND-SI |

Non-deposit taking Systemically Important Non-banking Financial Companies |

NBFCs |

Non-banking Financial Companies |

NBO |

National Building Organisation |

NCLT |

National Company Law Tribunal |

NDFs |

Non-deliverable Forwards |

NDS |

Negotiated Dealing System |

NDS-OM |

Negotiated Dealing System - Order Matching |

NEFT |

National Electronic Fund Transfer |

NGO |

Non-governmental Organisation |

NHB |

National Housing Bank |

NII |

Net Interest Income |

NPAs |

Non-performing Assets |

NPBs |

New Private Sector Banks |

NSC |

National Statistical Commission |

NSCCL |

National Securities Clearing Corporation Ltd. |

NSDL |

National Securities Depository Ltd. |

NSE |

National Stock Exchange |

NSSO |

National Sample Survey Organisation |

OBS |

Off-balance Sheet |

OECD |

Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development |

OFIs |

Other Financial Institutions |

OIS |

Overnight Index Swap |

OMO |

Open Market Operations |

OPBs |

Old Private Sector Banks |

OTC |

Over-the-Counter |

OTD |

Originate to Distribute |

P/E |

Price to Earnings |

PACS |

Primary Agricultural Credit Societies |

PCA |

Prompt Corrective Action |

PCAOB |

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board |

PDAI |

Primary Dealers Association of India |

PDO |

Public Debt Office |

PDs |

Primary Dealers |

PEP |

Politically-exposed Persons |

PFRDA |

Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority |

PMLA |

Prevention of Money-laundering Act |

PMRY |

Prime Minister’s Rozgar Yojana |

PNs |

Participatory Notes |

PPP |

Public-private Partnership |

PSBR |

Public Sector Borrowing Requirement |

PSBs |

Public Sector Banks |

QIB |

Qualified Institutional Buyers |

QRB |

Quality Review Board |

RARoC |

Risk-adjusted Return on Capital |

RBC |

Risk-based Capital |

RBS |

Risk-based Supervision |

RCS |

Registrar of Co-operative Societies |

RDDBFI |

Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions |

RNBCs |

Residuary Non-banking Companies |

RoA |

Return on Assets |

RoE |

Return on Equity |

ROSC |

Report on Observance of Standards and Codes |

RRBs |

Regional Rural Banks |

RSE |

Recognised Stock Exchange |

RTGS |

Real Time Gross Settlement |

SARFAESI |

Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interests Act |

SBI |

State Bank of India |

SCODA |

SEBI Committee on Disclosures and Accounting Standards |

SCRA |

Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act |

SDDS |

Special Data Dissemination Standard |

SEBI |

Securities and Exchange Board of India |

SEC |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

SFCs |

State Financial Corporations |

SGL |

Subsidiary General Ledger |

SHG |

Self-help Group |

SICA |

Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act |

SIDBI |

Small Industries Development Bank of India |

SIPS |

Systemically Important Payment Systems |

SIVs |

Structured Investment Vehicles |

SJSRY |

Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rojgar Yojana |

SLBC |

State-level Bankers’ Committee |

SLR |

Statutory Liquidity Ratio |

SMEs |

Small and Medium Enterprises |

SPV |

Special Purpose Vehicle |

SRA |

Statutory-regulatory Authority |

SRI |

Socially Responsible Investing |

SROs |

Self-regulatory Organisations |

SSI |

Small Scale Industry |

SSS |

Securities Settlement Systems |

StCBs |

State Co-operative Banks |

STP |

Straight-through Processing |

STR |

Suspicious Transactions Report |

STRIPS |

Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities |

STT |

Securities Transaction Tax |

SUCBs |

Scheduled Urban Co-operative Banks |

TACMP |

Technical Advisory Committee on Monetary Policy |

TAFCUB |

Task Force for Urban Co-operative Banks |

TAG |

Technical Advisory Group |

TDS |

Tax Deducted at Source |

UAPA |

Unlawful Activities Prevention Act |

UCBs |

Urban Co-operative Banks |

ULIPs |

Unit-linked Insurance Plans |

UNCITRAL |

United Nations Commission on International Trade Law |

URRBCH |

Uniform Regulations and Rules for Bankers’ Clearing Houses |

VaR |

Value-at-Risk |

WI |

When issued |

WOS |

Wholly-owned Subsidiaries |

WPI |

Wholesale Price Index |

WTO |

World Trade Organisation |

|

| |

| |

Chapter I |

|

| |

The Government of India in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India constituted the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment (CFSA) in September 2006 with a mandate to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the India’s financial sector focusing upon stability and development, including therein detailed assessments of its status and compliance with various international financial standards and codes. The CFSA was chaired by Dr. Rakesh Mohan, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India; the Co-Chairmen were Shri Ashok Jha, Dr. D. Subbarao and Shri Ashok Chawla. The Committee also had officials from the Government of India as its members (Annex I).

The CFSA had the following terms of reference:

• To identify appropriate areas, techniques and methodologies in the Handbook on Financial Sector Assessment brought out by the International Monetary Fund/World Bank, and in other pertinent documents for financial sector assessment relevant in the current and evolving context of the Indian financial sector;

• To apply relevant methodologies and techniques adapted to the Indian system and attempt a comprehensive and objective assessment of Indian financial sector, including its development, efficiency, competitiveness and prudential aspects;

• To analyse specific development and stability issues relevant to India; and

• To make available its report(s) through the Reserve Bank of India/ Government of India websites.

The approach, broad framework and work procedures were approved in the first meeting of the Committee. Following this, contact points were established with other major regulators as also external agencies like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank for co-ordination of the work. The IMF/World Bank also provided relevant templates for assessment of various standards and codes, which have been appropriately utilised in the Committee’s work. The CFSA held a series of meetings to review the progress, take stock and guide the work. The CFSA submitted an interim report to the then Hon’ble Finance Minister, Shri P Chidambaram and to the then Governor, Reserve Bank of India, Dr. Y V Reddy on August 2, 2007. The CFSA finalised its Overview report in its meeting held on December 20, 2008. The CFSA held 11 meetings between October 2006 and December 2008 before finalising its report.

1.1 Approach and Framework for the Assessment

The CFSA followed an approach to self-assessment based on three mutually-reinforcing pillars, viz., Pillar I: financial stability assessment and stress testing, essentially in the nature of stability assessment which utilises analytical tools for quantifying the risks and vulnerabilities in the financial sector; Pillar II: legal, infrastructural and market development issues; and Pillar III: comprehensive assessment of the status and implementation of international financial standards and codes, taking into account updates since the last FSAP/ ROSC and earlier self-assessments and the specific features of the Indian financial system. The second pillar draws inputs from the assessment in the first and third pillars focusing on developmental issues for further strengthening the financial sector.

In order to assist the CFSA in its process of assessment, four Technical Groups mainly comprising officials from relevant organisations who, based on their functional domain knowledge, provided technical notes and background material for assessments of their respective subject areas. The preliminary assessments of standards were also carried out by them. These Groups focused on (a) Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing, (b) Financial Regulation and Supervision, (c) Institutions and Market Structure and (d) Transparency Standards, respectively. The CFSA also constituted four Advisory Panels comprising non-official experts in the respective areas and, wherever necessary, was supported by senior officials in the form of Special Invitees, with requisite domain expertise. These Panels provided an impartial review of assessments made by the Technical Groups and prepared their draft reports.

With a view to further enhancing the credibility of the self-assessment, the CFSA arranged for the draft reports of the Advisory Panels to be peer reviewed by external experts. The Advisory Panel reports were finalised after taking into account the peer reviewers’ comments and their interactions with peer reviewers in conferences/seminars.

The CFSA finally drew up its Overview report based on the Advisory Panel reports.

A schematic diagram of the framework is provided in Annex II.

1.2 Work Process

1.2.1. Constitution of Advisory Panels and Technical Groups

Twenty six experts from diverse fields were identified as members of the four Advisory Panels. In addition, senior officials from the Government, the Reserve Bank, SEBI and IRDA were also inducted as ex officio special invitees to the panels. The complete list of all members and special invitees to the Advisory Panels is given in Annex III.

The four Advisory Panels were supported by four Technical Groups with the involvement of more than 100 officials drawn from various agencies. The details of membership and participation in various Technical Groups are provided in Annex IV.

1.2.2 Co-ordination with Multilateral Agencies

The IMF and the World Bank have been evincing keen interest in CFSA’s work and extending their support. At a very early stage, the Chairman held meetings with World Bank/IMF officials, who offered to help the Committee identify a list of experts, identify contact persons in the World Bank/IMF to liaise with the CFSA, share FSAP templates and identify FSAP documents for reference by the Committee. Also, the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) assisted IRDA in suggesting the names of peer reviewers and the International Organisation of Securities Commission (IOSCO) provided SEBI with the necessary IOSCO templates for the assessments. The CFSA gratefully acknowledges the assistance of these institutions.

1.2.3 Institutions/Agencies Involved

Taking into account the legal, regulatory and supervisory architecture in India, the CFSA involved and associated closely with all three major regulatory institutions, viz., the Reserve Bank, SEBI and IRDA. Depending on the sectoral/ functional distribution, several other agencies in the financial system were associated, besides involving concerned departments of the Central Government. A complete list of the agencies involved in the assessment exercise is given in Annex V.

1.2.4 Involvement of Peer Reviewers

The CFSA identified 14 international experts and three Indian experts to peer review the relevant portions of the Panel reports in accordance with the reviewers’ areas of expertise. The list of peer reviewers is given in Annex VI.

1.2.5 The Secretariat

To further the technical work and for administrative co-ordination between all the involved institutions and the study of relevant documents to prepare background material for the Technical Groups and Advisory Panels, a Secretariat was constituted in the Reserve Bank, Monetary Policy Department (Please see Annex VII for the composition of the Secretariat).

1.2.6 Detailed Work Procedures under each of the Three Pillars

Pillar I: Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing

The Advisory Panel on Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing covered areas related to the macro-economy, financial markets, financial infrastructure and financial institutions. The Panel constituted three sub-groups: relating to financial stability, stress testing and business continuity management (BCM). The sub-group on financial stability deliberated and identified the soundness and vulnerabilities in the Indian financial system. In addition to the Reserve Bank, SEBI and IRDA, it has also taken on board the perspectives of agencies like the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), National Housing Bank (NHB), Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), Investment Information and Credit Rating Agency of India Limited (ICRA), Credit Rating Information Services India Ltd. (CRISIL), KPMG and Clearing Corporation of India Ltd. (CCIL), and incorporated the same as part of their report.

The sub-group on stress testing adopted a plausible ‘bottom-up’ approach to stress testing, using various scenarios. Single factor stress tests for the commercial banking sector covering credit risk, market/interest rate risk and liquidity risk were carried out. The Group also undertook quantitative stress tests and qualitative analysis in respect of certain financial variables and liquidity infrastructure.

The sub-group on business continuity management (BCM) assessed the status of business continuity planning (BCP) and disaster recovery management. A questionnaire suitably expanding on the High Level Principles for Business Continuity Management developed by the BIS Joint Forum in August 2006 was circulated among identified banks as also CCIL. In addition, the Reserve Bank also undertook an assessment of its own BCM systems.

IRDA prepared a separate stability analysis for institutions within their regulatory purview including financial stability and stress testing issues relating to the insurance sector.

Pillar III: Assessment of Implementation of International Financial Standards and Codes

The implementation of/compliance with 14 international financial standards was evaluated under the comprehensive assessment exercise. The CFSA decided that in respect of AML-CFT standards a review of assessment undertaken by the Asia Pacific Group (APG) in 2005 would be incorporated in the Overview Report. For operational convenience, these standards were divided into three compact groups, viz., Regulation and Supervision, Institutions and Market Structure, and Transparency Standards.

In addition to the assessment of adherence to Basel Core Principles regarding supervision of commercial banks, the Advisory Panel on Financial Regulation and Supervision also conducted assessment of the adherence to Core Principles as relevant in other closely-related segments such as the urban cooperative banking sector, rural credit institutions and non-banking and housing finance companies. Likewise, an assessment of the observance of International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) Core Principles in the securities market was undertaken by SEBI. In addition, an assessment of the implementation of IOSCO Principles as relevant to government securities market and in respect of foreign exchange and money markets was also undertaken for the first time, involving the concerned departments in the Reserve Bank. The adherence to Core Principles of the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) was assessed by IRDA.

The Advisory Panel on Institutions and Market Structure undertook a detailed assessment of market infrastructure focusing on liquidity management, accounting and auditing, corporate governance, payment and settlement systems and legal infrastructure.

In respect of payment and settlement systems, the coverage was extended to an assessment of their adherence to the Core Principles for Systemically Important Payment Systems in respect of Real Time Gross Settlement System (RTGS) and High Value Clearing System; Recommendations for Securities Settlement Systems in respect of settlement of government securities and equities markets; Recommendations for Central Counterparties applicable to government securities, foreign exchange market and Collateralised Borrowing and Lending Obligation (CBLO) and corporate bonds and equities. The assessment of adherence to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Principles of Corporate Governance in respect of listed and unlisted companies was carried out jointly by SEBI and the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India. The assessment of convergence of Indian accounting and auditing standards put out by ICAI to the international accounting and auditing standards was assessed by ICAI, AASB and the Reserve Bank. The adherence to the World Banks Principles for Effective Insolvency and Creditor Rights Systems was assessed by the Reserve Bank and the Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

The Advisory Panel on Transparency Standards assessed the adherence to relevant IMF standards, viz., Code of Good Practices on Transparency in Monetary and Financial Policies, Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency, Special Data Dissemination Standards and Data Quality Assessment Framework. While the assessment of transparency in monetary policy pertained to the Reserve Bank, transparency in financial policies included the three agencies, viz., the Reserve Bank, SEBI and IRDA. Fiscal transparency assessment involved a response to a detailed questionnaire to relevant government departments, State Governments and the Reserve Bank to identify the gaps in fiscal transparency. For the first time, the Advisory Panel attempted a separate assessment of fiscal transparency pertaining to State Governments. Data dissemination was assessed with emphasis on dimensions of quality of the data.

Pillar II: Development Issues

The assessments and findings under Pillar I and III led to identification of several areas for convergence with international best practices as also certain issues and concerns in regard to further strengthening and developing the financial sector. The Advisory Panels have made appropriate recommendations as part of their assessments of financial institutions, financial markets and financial infrastructure.

1.3 Scheme of the Report

Drawing on inputs from the four Advisory Panel Reports, the CFSA first addresses the issues relating to the macro-economic environment and identifies certain potential areas of vulnerability at the current juncture. The financial sector assessment part is covered in three major parts, viz., financial institutions, financial markets and financial infrastructure. All standards assessments, excepting transparency issues, have also been integrated appropriately into these assessments. The CFSA addresses these areas broadly encompassing their performance and resilience to certain shocks, and identifying areas for further strengthening and development. Transparency issues are covered in a separate chapter by the CFSA. The CFSA considered the views of the Panels as also those of peer reviewers and recorded their own stance in the respective chapters.

Based on the above approach, the Committee’s Overview Report is divided into eight chapters. Following this chapter, Chapter 2 covers aspects relating to the macro-economic environment including an assessment of potential areas of vulnerability; Chapter 3, after providing an overview of the financial structure, covers in detail the stability aspects of financial institutions including structure and performance, resilience, relevant observance of standards and issues and recommendations for further development; Chapter 4 covers assessment of financial markets which includes structure and performance, observance of relevant standards and issues and recommendations for further market development; Chapter 5 covers financial infrastructure which encompasses a host of dimensions, viz., regulatory structure, liquidity management, accounting and auditing, payment and settlement systems, legal infrastructure including bankruptcy laws, business continuity management, corporate governance issues and safety net issues focusing on deposit insurance. The concerned sections also address issues and recommendations for strengthening the financial infrastructure. Chapter 6 covers transparency issues relating to monetary policy, financial policies, fiscal policy and data dissemination, and Chapter 7 covers broader development issues in the socio-economic context, mainly relating to customer service and financial inclusion.

The concluding Chapter provides a summary of observations and recommendations with appropriate cross-references to earlier chapters. |

| |

Annex I |

| |

Composition of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

Chairman

Dr. Rakesh Mohan Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India |

Co-Chairman

Shri Ashok Chawla

Secretary

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(from September 6, 2008) |

|

Dr. D. Subbarao

Former Finance Secretary

Government of India

(July 16, 2007 - September 5, 2008) |

|

Shri Ashok Jha

Former Finance Secretary

Government of India

(September 13, 2006 - July 15, 2007) |

Members |

|

Shri Arun Ramanathan Finance Secretary Government of India (from February 4, 2008) |

|

Shri Vinod Rai

Former Secretary

Department of Financial Services

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(January 11, 2007 - February 3, 2008) |

|

Dr. Arvind Virmani Chief Economic Adviser Department of Economic Affairs Ministry of Finance Government of India |

|

Dr. Alok Sheel

Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank)

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(from October 23, 2008) |

|

Shri Madhusudan Prasad

Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank)

Department of Economic Affairs

Ministry of Finance

Government of India

(September 13, 2006 - October 22, 2008) |

|

|

| |

Governor |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Mumbai - 400 001 |

| |

MEMORANDUM |

| |

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

Building up resilient, well-regulated financial systems is essential for macroeconomic and financial stability. This is being increasingly recognised as an integral part of financial sector reforms in India. Following the initiation of the Financial Sector Assessment Programme (FSAP) in 1999 by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis, and their experience in the conduct of assessment in member countries, the two institutions have jointly brought out in September 2005, a comprehensive Handbook on Financial Sector Assessment. The Handbook is designed for use in financial sector assessment, whether conducted by country authorities themselves or by World Bank and IMF teams. The Handbook, available to the public, is intended to serve as an authoritative source on the objectives, analytical framework, and methodologies of financial sector assessment as well as a comprehensive reference book on the techniques of such assessments.

2.

It may be recalled that India, besides being one of the earliest member countries participating voluntarily in the FSAP assessment, has been a forerunner in comprehensive self-assessment of various international financial standards and codes. The Reserve Bank has also released a Synthesis Report in May 2002 and a Progress Report in January 2005. The experience has thus far been very encouraging and the financial sector reforms have progressed well in recent years, enhancing the soundness of the financial system and promoting financial stability.

3.

Consistent with this approach, it would be appropriate and expedient for India to undertake a self-assessment of financial sector stability and development, using the new Handbook as the base as also any other pertinent documents for financial sector assessment. Accordingly, the Government of India has decided, in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India to constitute a Committee on Financial Sector Assessment, with the following terms of reference:

(i) To identify the appropriate areas, techniques and methodologies in the Handbook and also in any other pertinent documents for financial sector assessment relevant in the current and evolving context of the Indian financial sector;

(ii) To apply relevant methodologies and techniques adapted to Indian system and attempt a comprehensive and objective assessment of Indian financial sector, including its development, efficiency, competitiveness and prudential aspects;

(iii) To analyse specific development and stability issues as relevant to India; and

(iv) To make available its report(s) through RBI/GoI websites.

|

| |

4. The Committee may co-opt members depending upon the subject area of assessment under consideration and may also constitute Technical/ Advisory groups to study and report on specific areas of assessment.

5. The Committee will be chaired by Dr.Rakesh Mohan, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, with Shri Ashok Jha, Secretary (Economic Affairs) as Co-Chairman. Dr.Ashok Lahiri, Chief Economic Adviser and Shri Madhusudan Prasad, Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank), Government of India will be its members. The Secretariat will be provided by the Reserve Bank of India.

6. The Committee will review its own status and report the progress to the Government of India/Reserve Bank of India in six months from commencement of its work. |

| |

(Y.V. Reddy) |

| |

Mumbai - 400 001.

September 13, 2006 |

| |

| Governor |

| |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Mumbai - 400 001 |

| |

MEMORANDUM |

|

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

| In partial modification of the memorandum dated September 13, 2006 regarding constitution of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment, it has been decided to include Shri Vinod Rai, Secretary (Financial Sector), Government of India and Dr. Arvind Virmani, Principal Adviser, Planning Commission, into the Committee. Accordingly, the composition of the reconstituted Committee on Financial Sector Assessment is as follows: |

| |

Dr. Rakesh Mohan Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India |

Chairman |

Shri Ashok Jha Finance Secretary Government of India |

Co-Chairman |

Shri Vinod Rai

Secretary (Financial Sector)

Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Dr. Arvind Virmani Principal Adviser Planning Commission |

Member |

|

|

Shri Madhusudan Prasad Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank) Government of India |

Member |

|

|

|

| |

(Y.V. Reddy) |

| |

Mumbai - 400 001.

January 11, 2007 |

| |

| Governor |

| |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Mumbai - 400 001 |

| |

MEMORANDUM |

|

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

In partial modification of the memorandum dated January 11, 2007 it has been decided to appoint Dr. D Subbarao, Finance Secretary, Government of India as the Co-chairman of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment on retirement of Shri Ashok Jha, the earlier Finance Secretary and Co-chairman of the Committee. Accordingly, the composition of the reconstituted Committee on Financial Sector Assessment is as follows: |

| |

Dr. Rakesh Mohan Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India |

Chairman |

Dr. D Subbarao Finance Secretary Government of India |

Co-Chairman |

Shri Vinod Rai

Secretary (Financial Sector)

Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Dr. Arvind Virmani Principal Adviser Planning Commission |

Member |

|

|

Shri Madhusudan Prasad Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank) Government of India |

Member |

|

|

|

| |

(Y.V. Reddy) |

| |

Mumbai - 400 001.

July 16, 2007 |

| |

| Governor |

| |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Mumbai - 400 001 |

| |

MEMORANDUM |

|

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

In partial modification of the memorandum dated July 16, 2007 it has been decided to co-opt Shri Arun Ramanathan, Secretary (Financial Sector), Government of India as a member of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment in place of Shri Vinod Rai, former Secretary (Financial Sector), Government of India, consequent to Shri Rais appointment as the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Accordingly, the composition of the reconstituted Committee on Financial Sector Assessment is as follows: |

| |

Dr. Rakesh Mohan Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India |

Chairman |

Dr. D Subbarao Finance Secretary Government of India |

Co-Chairman |

Shri Arun Ramanathan Secretary (Financial Sector) Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Dr. Arvind Virmani Chief Economic Adviser Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Shri Madhusudan Prasad Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank) Government of India |

Member |

|

|

|

| |

(Y.V. Reddy) |

| |

Mumbai - 400 001.

February 4, 2008 |

| |

| Governor |

| |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Mumbai - 400 001 |

| |

MEMORANDUM |

| |

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

In partial modification of the memorandum dated February 4, 2008 it has been decided to co-opt Shri Ashok Chawla, Secretary (Economic Affairs), Department of Economic Affairs, Government of India as Co-chair of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment in place of Dr. D. Subbarao, former Finance Secretary, Government of India, consequent to Dr.D.Subbaraos appointment as the Governor, Reserve Bank of India. Accordingly, the composition of the reconstituted Committee on Financial Sector Assessment is as follows: |

| |

Dr. Rakesh Mohan Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India |

Chairman |

Shri Ashok Chawla Secretary

(Economic Affairs) Government of India |

Co-Chairman |

Shri Arun Ramanathan Secretary (Financial Sector) Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Dr. Arvind Virmani Chief Economic Adviser Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Shri Madhusudan Prasad Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank) Government of India |

Member |

|

|

|

| |

(D.Subbarao) |

| |

Mumbai - 400 001.

October 1, 2008 |

| |

| Governor |

| |

Reserve Bank of India

Central Office

Mumbai - 400 001 |

| |

MEMORANDUM |

|

Committee on Financial Sector Assessment |

| |

| In partial modification of the memorandum dated October 1, 2008 it has been decided to appoint Shri Alok Sheel, Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank), Government of India as a member of the Committee on Financial Sector Assessment in place of Shri Madhusudan Prasad who has been transferred from the post of Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank). Accordingly, the composition of the reconstituted Committee on Financial Sector Assessment is as follows: |

| |

Dr. Rakesh Mohan Deputy Governor Reserve Bank of India |

Chairman |

Shri Ashok Chawla Secretary

(Economic Affairs) Government of India |

Co-Chairman |

Shri Arun Ramanathan Finance Secretary Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Dr. Arvind Virmani Chief Economic Adviser Government of India |

Member |

|

|

Shri Alok Sheel

Joint Secretary (Fund-Bank)

Government of India |

Member |

|

|

|

| |

(D.Subbarao) |

| |

Mumbai - 400 001.

November 26, 2008 |

| |

|

| |

Annex III |

| |

Advisory Panel Members and Special Invitees |

| |

Name |

Designation/Institution |

1. Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing |

Shri M.B.N.Rao |

Chairman and Managing Director, Canara Bank |

Chairman |

Dr. Rajiv B. Lall |

Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer, Infrastructure Development Finance Company Ltd. |

Member |

Dr. T.T.Ram Mohan |

Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad |

Member |

Shri Ravi Mohan |

Managing Director and Region Head, Standard & Poor’s, South Asia |

Member |

Shri Ashok Soota |

Chairman and Managing Director, MindTree Consulting Ltd. |

Member |

Shri Pavan Sukhdev |

Head of Global Markets, Deutsche Bank |

Member |

Special Invitees |

Shri V.K.Sharma |

Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India |

|

Dr. R. Kannan |

Member (Actuary), Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority |

|

Shri G. C. Chaturvedi |

Joint Secretary (Banking and Insurance), |

|

Dr. K. P. Krishnan |

Joint Secretary (Capital Markets), Government of India |

|

Shri Amitabh Verma |

Joint Secretary (Banking Operations), Government of India |

|

Dr. Sanjeevan Kapshe |

Officer on Special Duty, Securities and Exchange Board of India |

|

|

| |

2. Financial Regulation and Supervision |

| |

Shri M. S. Verma |

Former Chairman, State Bank of India |

Chairman |

Shri Nimesh Kampani |

Chairman, JM Financial Consultants Pvt. Ltd. |

Member |

Shri Uday Kotak |

Executive Vice-Chairman and Managing Director, Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. |

Member |

Shri Aman Mehta |

Former Chief Executive Officer, Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation |

Member |

Dr. M. T. Raju |

Professor and In-charge, Indian Institute of Capital Markets |

Member |

Smt. Shikha Sharma |

Managing Director, ICICI Prudential Life Insurance Company |

Member |

Shri U. K. Sinha |

Chairman and Managing Director, UTI Asset Management Co. Pvt. Ltd. |

Member |

Special Invitees |

Shri Anand Sinha |

Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India |

|

Shri C.R. Muralidharan |

Member, Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority |

|

Shri G. C. Chaturvedi |

Joint Secretary (Banking and Insurance), |

|

Dr. K. P. Krishnan |

Joint Secretary (Capital Markets), Government of India |

|

Shri Amitabh Verma |

Joint Secretary (Banking Operations), Government of India |

|

Smt. Usha Narayanan |

Executive Director, Securities and Exchange Board of India |

|

Shri Arun Goyal |

Director, Financial Intelligence Unit, Government of India |

|

|

| |

3. Institutions & Market Structure |

| |

Shri C M. Vasudev |

Former Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs Ministry of Finance Government of India |

Chairman |

Shri C. B. Bhave |

Chairman and Managing Director, National Securities Depository Ltd.

(upto Febuary 15, 2008) |

Member |

Dr. K. C. Chakraborty |

Chairman and Managing Director, Punjab National Bank |

Member |

Dr. R. Chandrasekhar |

Dean, Academic Affairs, Institute for Financial Management and Research |

Member |

Dr. Ashok Ganguly |

Chairman, Firstsource Solutions Ltd. |

Member |

Dr. Omkar Goswami |

Chairman, CERG Advisory Pvt. Ltd. |

Member |

Shri Y. H. Malegam |

Managing Partner, S. B. Billimoria & Co. Chartered Accountants |

Member |

Dr. Nachiket Mor |

President, ICICI Foundation for Inclusive Growth |

Member |

Shri T.V.Mohandas Pai |

Member of the Board, Infosys Ltd. |

Member |

Shri Gagan Rai |

Chairman and Managing Director, National Securities Depository Ltd. (from Febuary 25, 2008) |

Member |

Dr. Janmejaya Sinha |

Managing Director, Boston Consulting Group |

Member |

Special Invitees |

Dr. R. B. Barman |

Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India |

|

Shri Anand Sinha |

Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India |

|

Shri C.R. Muralidharan |

Member, Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority |

|

Shri Jitesh Khosla |

Joint Secretary (Corporate Affairs), Government of India |

|

Dr. K. P. Krishnan |

Joint Secretary (Capital Markets), Government of India |

|

Shri Sandeep Parekh |

Adviser (Legal), Securities and Exchange Board of India |

|

|

| |

4. Transparency Standards |

| |

Shri Nitin Desai |

Under-Secretary-General, United Nations |

Chairman |

Dr. Jaimini Bhagwati |

Additional Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India |

Member |

Dr. Shubhashis Gangopadhyay |

Director, India Development Foundation |

Member |

Dr. Rajiv Kumar |

Director and Chief Executive, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations |

Member |

Dr. Rajas Parchure |

Faculty, Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune |

Member |

Dr. Indira Rajaraman |

Reserve Bank Chair Professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy |

Member |

Shri Mahesh Vyas |

Managing Director & CEO, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy |

Member |

Special Invitees |

Dr. R. B. Barman |

Executive Director, Reserve Bank of India |

|

Shri Jitesh Khosla |

Joint Secretary (Corporate Affairs), Ministry of Corporate Affairs Government of India |

|

Dr. M. C. Singhi |

Economic Advisor, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance Government of India |

|

Shri P. K. Nagpal |

Executive Director, Securities and Exchange Board of India |

|

|

| |

Annex IV |

| |

Technical Group on Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing |

No. |

Name |

Designation/Organisation |

|

1. |

Shri C.S. Murthy |

Chief General

Manager-in-charge, RBI |

Member |

2. |

Shri P.Krishnamurthy |

Chief General

Manager-in-charge, RBI |

Member |

3. |

Shri Prashant Saran |

Chief General

Manager-in-charge, RBI |

Member |

4. |

Shri N.S. Vishwanathan |

Chief General Manager, RBI |

Member |

5. |

Shri Chandan Sinha |

Chief General Manager, RBI |

Member |

6. |

Dr. A.S Ramasastri |

Adviser, RBI |

Member |

7. |

Shri Sudarshan Sen |

Chief General Manager, RBI |

Member |

8. |

Dr. Charan Singh |

Director, RBI |

Member |

9. |

Shri S. Ramann |

Chief General Manager, SEBI |

Member |

10. |

Shri K. Kanagasabapathy |

Secretary to CFSA |

Convener |

|

| |

Technical Group for Aspects of Stability and Performance of Insurance Sector |

| |

No. |

Name |

Designation |

1. |

Shri S.V. Mony |

Secretary General, Life Insurance Council |

2. |

Shri S. P. Subhedar |

Senior Advisor, Prudential Corporation, Asia |

3. |

Shri N. S. Kannan |

Executive Director, ICICI Prudential Life Insurance Company Ltd |

4. |

Prof R. Vaidyanathan |

Professor (Finance), IIM Bangalore |

5. |

Dr. K. Sriram |

Consulting Actuary, Genpact |

|

| |

List of Officials also Associated with the Technical Group’s/Panel’s Deliberations on Financial Stability Assessment and Stress Testing |

| |

No. |

Name |

Designation/Organisation |

1. |

Shri T.V.Mohandas Pai |

Member of the Board and Director-Human Resources, Infosys |

2. |

Shri Anand Sinha |

Executive Director, RBI |

3. |

Shri S.K. Mitra |

Executive Director, NABARD |

4. |

Dr. Nachiket Mor |